32 minute read

A Partnership for a Lifetime

Colton Woods was scheduled to be a presenter at Equitana USA this year, but the threeday celebration of the horse was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Equestrian professionals and enthusiasts can meet Woods at Equitana USA, Oct. 1-3, 2021, at the Kentucky Horse Park. To learn about Equitana presenters in various equine disciplines, visit equitanausa.com.

While he trains horses, Colton Woods also educates their owners to strengthen their relationship with their equine companions

BY DEBORAH KOHL KREMER

With a mission to “Educate Horses and People with a Lifetime in Mind,” Colton Woods Horsemanship of Paris works to train horses and teach horse owners what their trained horse needs to succeed. Owner Colton Woods uses a holistic approach in his training, which involves examining how the horse thinks and what motivates it. He also adds technical skills and some human psychology.

“We want to help the horses, but we need to help the people who own them as well,” he said.

Woods did not grow up aspiring to be a horse trainer. He loved to play sports, and his parents were professionals whose careers took the family to live in China for two years when Woods was 12. He had never been around horses, let alone ridden one. But when he turned 16, he got a job on a hunter-jumper horse farm, where his duties included mucking stalls and stacking hay. Then for several summers, he worked at a show-horse training program, where he earned his stripes and cemented his love of horse training. During high school, Woods took a job at Safe Haven Equine Rescue & Retirement Home in North Carolina to fulfill his service hours for graduation. That summer, the young and strong volunteer was assigned to build fences and shovel gravel, but along the way, he saw neglected and abandoned horses that would never find a home.

“I realized that neither the horse nor the human was educated in training, and neither had access to this training,” he said. “I found my purpose. I needed to train the horse and make them adoptable, so they could find a home.”

Woods headed to University of Kentucky, where he majored in equine science and management with a business focus and a minor in agricultural economics. He was fortunate to get valuable internships such as one at Taylor Made Sales Agency, where he learned to care for, exercise and show Thoroughbreds. Throughout college, Woods got up early and stayed up late working with horses and meeting people who worked with an assortment of breeds.

After college graduation, Woods accepted the position of assistant trainer at Double Dan Horsemanship in Midway, where he cared for a team of horses and continued learning. In 2016, Colton and his then-fiancé Maredith decided to put down roots in the Paris and Georgetown area and established Colton Woods Horsemanship, which combined their shared passion for horses. Now married, the couple own and operate the business together.

Colton Woods Horsemanship has had many successes along the way and is well-known in the horse world. Woods credits these successes to his training criteria, which includes several components. First, he works with the horse on ground skills, such as leading, trailer loading and saddling. The second step involves teaching the horse what to do once the saddle is on. This includes how to trot, canter and back up. Then, Woods moves on to performance-type skills such as dressage, hunter and jumper and versatility. Lastly—and possibly the most important—is the owner training, which is offered free to horses being trained by Woods.

“All of this creates a partnership between the horse and the athlete,” he said.

Woods trains horses and teaches classes at home, but he spends many weeks on the road, doing the same thing at farms and horse shows. His website offers online educational opportunities, and his podcast, “The Heart of Horsemanship,” provides a vehicle for him to broadcast tips and guidance and include guests who can share their insights.

Woods sums up his intentions on his website: “Our greatest mission is to leave a lasting legacy of positive impact on the lives of horses and people all across the globe. Whether through an in-person event, online video or course, on the phone, or on social media, our top priority is to provide you with valuable content that helps you and your horse take your next step on your horsemanship journey.”

For more information, visit coltonwoodshorsemanship.com.

Honoring a Racing Hero

In 1919, Sir Barton won horse racing’s first American Triple Crown before the iconic Triple Crown was formally proclaimed as such. That perhaps symbolizes the tepid reception the amazing Thoroughbred has garnered throughout the sport’s history.

Sir Barton was sired by an English horse, Star Shoot, out of the mare Lady Sterling and bred by John Madden, owner of Lexington’s famed Hamburg Place (now the location of a major retail center), but was later sold to Canadian businessman J.K.L. Ross.

Sir Barton’s racing record was impressive, with 13 wins, 6 seconds and 5 thirds in 31 starts. He was a competing contemporary of the great Man o’ War. For the racing world, some thought a match race was needed to find some sort of separation between the two. It happened on Oct. 12, 1920, at Kenilworth Park near Windsor, Ontario, Canada.

For Sir Barton, things didn’t turn out well.

In Sir Barton and the Making of the Triple Crown, author Jennifer S. Kelly “charts how Sir Barton broke track records, scored victories over other champions, and sparked the yearly pursuit of Triple Crown glory … [and] helps carve out a place in racing fans’ collective memory for a horse whose legacy has languished in the shadow of Man o’ War for nearly a century.”

By Steve Flairty

Sir Barton and the Making of the Triple Crown By Jennifer S. Kelly University Press of Kentucky, $29.95 (C)

Untold Racing Stories

Horse racing conjures up images of the twin spires of Churchill Downs and the changing leaves at Keeneland in the fall, but the sport is so much more. This book tells some of the stories that race fans may never have heard, as well as the history of how racing came to be the way it is today.

Hidden History of Horse Racing in Kentucky provides interesting facts about long-forgotten horse farms and racetracks. It also shines a wonderful spotlight on the group that the author refers to as the first professional athletes, the AfricanAmerican jockeys of the 1800s. Although they had huge successes on the track, these men had no choice but to travel to racetracks in Europe as the segregation laws of the Jim Crow era and a trend toward hiring Caucasian jockeys made finding mounts difficult.

Seventh-generation Kentuckian and Lexington native Foster Ockerman Jr. is an attorney and historian. He is president of the Lexington History Museum and serves as historian there. Ockerman is a contributor to the public television series Chronicles: Kentucky History Magazine.

By Deborah Kohl Kremer

Hidden History of Horse Racing in Kentucky By Foster Ockerman Jr. The History Press, $21.99 (P)

Equine Anecdotes

If you hear someone described as having horse racing in their blood, well, they may well be talking about Ercel Ellis Jr. His father was the manager of Dixiana Farm in Lexington, and young Ercel grew up surrounded by horses. He was born in 1931, and by the time he was just 6 years old, his dad had introduced him to an amazing horse named Man o’ War, which was not the only superstar horse he met along his 75-year career in the horse industry.

A past editor of The BloodHorse magazine and Daily Racing Form, Ellis also has been an owner, breeder, trainer and radio host, including his 20-year radio show, Horse Tales.

Kentucky Horse Tales makes the reader feel engaged in a conversation with Ellis as he tells some of his favorite stories of horses he has known and loved. Some you have heard of, most you have not, but all are tales that any horse lover will enjoy.

Ellis lives on a Bourbon County farm with his wife, Jackie, and several retired racehorses.

By Deborah Kohl Kremer

Kentucky Horse Tales By Ercel Ellis Jr. The History Press, $21.99 (P)

Ready for a break?

Explore Kentucky’s finest Bed & Breakfasts

Lincoln’s Rhetorical Style

More than 150 years have passed since Abraham Lincoln’s death, and his quotes and parts of speeches are still regularly referenced. Although speeches and letters have been studied for historical facts and to understand the way he felt, this book delves into Lincoln’s prose and how his rhetorical style changed over the years. By comparing early letters to those written later, Dr. Marshall Myers brings out examples of Lincoln’s maturity and how he adapted his writing to the audience he was addressing.

More than 5,000 letters have been identified as written by Lincoln, and naturally, not all were used in this project, but typical nuances and word choices became apparent as the research continued. Myers gives examples of Lincoln’s early letters, which have a different tone than those to his generals during the Civil War and to his cabinet. A more endearing side of Lincoln is studied in letters to friends and, of course, his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln.

Myers, of Richmond, has written more than 300 articles, stories and poems. He is professor emeritus of English and former coordinator of composition at Eastern Kentucky University.

By Deborah Kohl Kremer

The Rhetoric of Lincoln’s Letters By Marshall Myers, McFarland, $39.99 (P)

A Storybrook Inn

PADUCAH Belle Louise Historic Guest House 270.210.2553 bellelouisepaducah@gmail.com

LAGRANGE Bluegrass Country Estate 502.222.2009 bluegrasscountryestate.com

BURLINGTON Burlington Willis Graves B&B 859-689-5096

PARK CITY Grand Victorian Inn 270.590.1935 grandvictorianinnky.com In the heart of beautiful Horse Country, Storybook Inn is a nationally award-winning historic Inn, housed in a meticulously restored mansion that exudes gracious SOUTHERN hospitality!

VERSAILLES STORYBOOK-INN.COM 859.879.9993

GLASGOW Hall Place B&B 866.925.2912

HAZARD Harmony House and Goose House Inn 606.435.2079 harmonyhousebed andbreakfast.net

VERSAILLES Montgomery Inn 859.251.4103 montgomeryinnbnb.com

LIVERMORE River Trails inn 270.278.2954 airbnb.com

IRVINE Snug Hollow Farm 606.723.4786 snughollow.com

SONORA Thurman Landing 270.949.1897 thurmanlanding.com

MORGANTOWN Woodbury Lodge 270.999.1683 woodburylodgebb.com

Paul Sawyier:

In 2000, the University Press of Kentucky published my book The Kentucky River. In the mid-1990s, Todd Moberly and I completed more than 150 interviews with people who had an intimate relationship with the river. Eastern Kentucky University and the Kentucky Oral History Commission supported this venture.

The interviewees included people who lived on the river and lockkeepers who had worked the 14 locks and dams at one time or another. Others had worked on river craft or had fished the river. “We lived half of the year on the Kentucky and the other half in the Kentucky,” recalled Marine Col. George M. Chinn, a renowned firearms expert and historian in his own right.

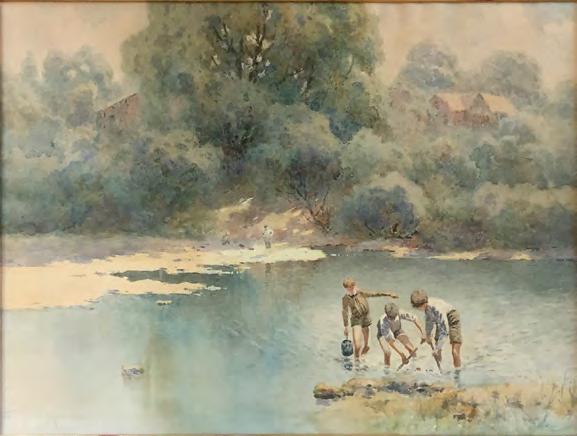

In chapter six, “My Mind on the River,” I concentrated on the thoughts and actions of people intimate with Kentucky River life. Of course, that included artist Paul Sawyier, who painted numerous scenes on or near the river.

g g g

My wife, Charlotte, and I have 10 Sawyier prints in our home, most given to us as gifts back in the 1970s and ’80s or inherited from my parents.

Though born in Ohio, Sawyier (1865-1917) came of age in Frankfort, where his father practiced medicine. Coming from an artistically inclined family, the youth studied briefly at the Cincinnati Art Academy under Frank Duveneck and with William Merritt Chase in New York City.

After his father became involved with the Kentucky River Mills at Lock and Dam 4 in Frankfort, Sawyier

occasionally served as traveling salesman for the mills. He worked reluctantly and not to any great success. The Sawyier family business did not prosper, with heavy debts weighing on both father and son. The

young artist fought a never-ending battle against poverty. Having to care for his aging parents, Sawyier scraped along selling through Frankfort and Lexington businesses, often making as little as $10 to $15 for several hours of work on a painting.

He was most at home in the Frankfort area. There, he developed a style akin to the French impressionistic en plein air painting, principally using watercolors. While he often painted outdoors, Sawyier also made use of photographs of specific sites and finished works in a makeshift studio. “Wapping Street Fountain,” “The Old Capitol,” “A Rainy Day in Frankfort,” “Kentucky River Scene” and “Old Covered Bridge” are early examples of his talent.

An avid outdoorsman and fisherman, Sawyier loved to roam the Kentucky River and its tributaries around Frankfort. There were periods of time when he was inactive. Then, he would work furiously for a spell.

Known as an affable companion, the Kentucky artist enjoyed his favorite brand of bourbon upon occasion, perhaps to excess at times. Sawyier kept up a longtime romance with Mary Thomas “Mayme” Bull of Frankfort. After the death of his parents, Sawyier broke free of family responsibilities and purchased an old houseboat, a motorboat, a skiff and a canoe in 1908. For most of the next five years, he slowly moved up to High Bridge and a little beyond.

g g g In an oral history interview, Margaret True recalled Sawyier when he tied up his shanty boat at Camp Nelson. “When I had to go to the grocery, my mother would make me go through the field to keep from disturbing him when he was painting,” she recalled. On other occasions, “I just spoke to Paul Sawyier; he was just Mr. Sawyier to me. I saw him at least twice a week.”

Along the way upriver, Sawyier painted “Sweet Lick Mountain” near Irvine for a businessman. He painted dozens of scenes, often entertained guests, and spent time visiting with friends along the river.

During his sojourn upriver, Mayme called off their 23-year courtship and shorter engagement after Paul allegedly became attracted to a younger woman.

Biographer Willian Donald Coffey surmised that Sawyier “experienced newfound freedom during his five years” on his houseboat from 1908 to 1913. At last, he appeared to be free to live his own life.

In the fall of 1913, the 48-year-old Sawyier moved to Brooklyn, New

York, and lived with his widowed sister Lillian. Thus began a new and last phase of his career. Though he appeared to have lived a virtual handto-mouth life as an artist, he already had had some success with exhibitions of his works in Cincinnati, at the Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1893, and at New York City galleries. He was not completely unknown.

In New York, he painted on commission for galleries and individuals. He began painting in other styles and with oils. During the brutal winter of 1915, he and a Belgian artist lived in a mostly unheated studio in the mountains. Sawyier found his last home with the Schaefer family in Fleischmanns, New York.

In the final months of his life, Sawyier apparently began drinking more heavily, and his work suffered. On Nov. 6, 1917, at age 52, he died of heart failure far from Kentucky. He was first buried in New York and then returned home to the Frankfort Cemetery on June 9, 1923.

g g g

One watercolor often seen in books and catalogs of Sawyier’s works is that of Mayme Bull in a canoe. Covered bridges, river banks, creek scenes, crops, Frankfort’s “Singing Bridge,” farmers harvesting hemp—just ordinary scenes captivated him.

Willard Rouse Jillson estimated that Sawyier painted 2,000-3,000 scenes, as well as portraits. William H. Coffey of Sawyier Galleries in Frankfort in a 1988 interview said he believed that the number was fewer. Coffey claimed to have “cataloged over 1,500 Sawyier originals, almost all watercolor landscapes and waterscapes.” There is an old story that the man who purchased Sawyier’s houseboat threw dozens of the artist’s paintings into the river.

I am not a connoisseur of art, but I like what I like. I like Sawyier. Impressionism, as I understand, must be viewed from an appropriate distance, depending on your eyesight. Faces are always indistinct or hidden. The scenes to me are more imaginable. A painting of a can of soup is not art to me. I have never seen anything by Vincent van Gogh that did not enthrall me. Sawyier could paint in other styles, and his portraits are outstanding. You cannot look at “The Rock Breaker,” a pastel on paper of a Black laborer, and not feel the melancholy of a portrait of a working man worn down by the elements and time. Like many prominent artists, Sawyier was influenced by his formal training, but he also was an individual who placed his own stamp on his work.

My favorites among the 10 prints that we own include “Boys Wading” and two of a sportsman, “Angler’s Rest” and “The Fisherman.”

Arthur F. Jones in The Art of Paul Sawyier declared the Kentuckian “must be assessed overall as a minor master in American art.” I think Sawyier would have been satisfied with that.

How many Sawyier prints do you have? Which is your favorite?

R

Using promo code:

DISCOUNT854 DISCOUNT854

Offer is online only. Valid for up to 8 admissions. No double discounts. Expires September 27, 2020.

Scan now for online savings

by Walt Reichert

Get the Dirt on Good Soil

If there is one thing gardening columnists and “educators” don’t do enough of, it’s emphasizing the importance of good soil. It is much more fun to write about the latest weeping, variegated, aqua-florescent, everblooming flower introduction than it is to write about something as mundane as dirt—well, soil. But nothing is more important.

Soil not only provides the “foundation” for your garden plants, it also gives them the nourishment they need, the air they breathe, the water they drink, the home for their roots. Put a good plant in poor soil, and it will fail to flourish if not die outright; put a poor plant in good soil, and it will eventually, if not right away, take off and thrive. So the gardener who knows how to find—or make—good soil is way ahead of the gardener who knows how to pick out good plants.

A Soil Primer

What makes a good soil? Let’s start with a useful, if oversimplified, primer. Soil essentially is weathered rock mixed with organic matter. It comes in three basic types: sand, silt and clay. Each type has advantages and disadvantages.

Sandy soils give plants plenty of space for root growth and drain well. Too well, in fact—they tend to be droughty. Sandy soils also tend to hold few nutrients because minerals in sandy soils wash away easily. These soils are most common in eastern Kentucky.

Silt soils—the rarest of the three, at least in Kentucky—drain well and hold nutrients better than sandy soils, but they also dry out readily. Old riverbeds and bottoms often have silty soils.

Clay soils, which predominate in central and much of western Kentucky, often are poorly drained, but they are richer in nutrients than sands and silts. They also are slower to warm up in the spring and, once dried out, can be difficult to saturate again.

If you are lucky enough to have a mixture of sand, silt and clay, you have what is called a loam, which is close to the ideal gardening soil. Loam soils hold nutrients and moisture better than sand and silt, but they have much better drainage than clay soils. Loams are more common in western Kentucky but can be found throughout the state. I’ve just never been lucky enough to garden in a loam.

One problem for many gardeners is that, even if they live in an area with decent soil, their landscapes and gardens have poor soil, especially if they plant near the house. That’s because, when their homes were built and foundations dug, the contractors piled all the dirt they excavated right up around the house. That dug-up soil lacks oxygen and is a poor medium for root growth. Even if the contractor was conscientious and saved the topsoil to use as a top layer, the compression caused by heavy machinery often has damaged the soil structure.

That explains why older houses in cities, the foundations of which were dug with horse-drawn and lighter equipment, have much better soil than houses in new developments.

Making Soil Better

The good news is that soil can be improved. The bad news is it won’t happen overnight. But it is definitely worth the effort, and fall is a good time to start.

First, forget about buying fancy soil amendments and soil conditioners. They are gardening voodoo and a waste of money. Commercial fertilizers, such as 10-10- 10, are fine, but be aware they are a quick fix and do nothing to improve the basic structure of the soil. The key to making soil better is adding organic matter. Over time, the breakdown of organic matter improves soil structure, allowing it to drain better, and adds nutrients in a form that plants can readily access.

For small gardens and landscaping around the house, adding compost and/or organic mulches to the soil is a good start. You can buy compost by the bag or, even better, make it yourself. Spread a thin layer (no deeper than an inch) over the garden and top with mulch. The compost will supply nutrients fairly quickly, and the mulch will break down to keep improving the soil’s structure.

For larger gardens—vegetable plots, perennial borders or rose beds—you might add organic matter in the form of either animal manures (assuming these are not right next to the house—or your neighbor’s house) or cover crops. Ideally, animal manures should be composted first, but you can do what’s called “sheet composting” by spreading them in a thin layer over the bed and letting Mother Nature do the composting. This is best done in late fall or early winter. Another way to add organic matter on a larger scale is to plant what’s called a cover crop in the fall and work it into the soil in the spring. Rye, Austrian peas or winter wheat make good cover crops. Just be sure you have the capacity to turn the cover crop into the soil in late winter or early spring; otherwise, your cover crop becomes an obnoxious weed.

Adding organic matter to a large area, such as a big lawn, is trickier. You likely don’t want to spread dairy droppings all over the place, and tilling up a crop of rye may be a bit much. The best approach to improving lawn soil is to keep grass growing vigorously. (If you read last month’s column, you know how to do that.) And use a mulching blade for mowing. The mulching mower chops up the grass into fine particles, adding organic matter to the soil as you cut. Whatever you do, don’t habitually sweep up the grass clippings; you are robbing the soil of its chance to improve itself.

In summation, think of adding organic matter to your garden soil the same way you add a small amount of money to your bank account every week. It seems like it will take forever to get rich, but all of a sudden you’re in the green.

The outdoors are calling

The beautiful outdoors of Hopkins County are the perfect summer getaway for a week or even just a weekend. Explore. Relax. Refresh.

Return with memories that will last a lifetime.

877-243-5280

COVID at the Ramp

“We are not defenseless against COVID-19. Cloth face coverings are one of the most powerful weapons we have to slow and stop the spread of the virus … All Americans have a responsibility to protect themselves, their families and their communities.” —Dr. Robert R. Redfield, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, July 14, 2020

PHOTO COURTESY OF OLD TOWN

The voice startled me, and I wheeled around in a manner that might have suggested a defensive posture that was neither intended nor needed. I’ve been a little jumpy lately. We all have.

“Thanks,” I said with an unintended but clearly audible grunt. “But I got it.”

He helped anyway, grabbing the bow hand grip and marching up the slight incline toward the parking area. It’s really a one-person job, and I had trouble hiding my annoyance.

By the time we reached my gently used, recently purchased, new-to-me Subaru, my helpmate was laboring for breath. The Old Town Sportsman AutoPilot 120 kayak we were pulling weighs nearly 130 pounds fully rigged, which this one was. The battery adds about another 50 pounds.

It was a sweltering summer evening in rural Anderson County. We were both sweating profusely. Fishing had been spotty—mostly bluegill, but I had one bass that was a solid 2 pounds; they all went back into the lake to be caught another day. I unlocked the car, opened the rear hatch, and pulled two bottles of water from the ice chest. The ice had melted, but the water was still cool. I also reached toward the console for my face mask, then handed my helper a water bottle. I looped the mask over my right ear and let it hang freely while I gulped the water. My helper was about my age with salt-and-pepper hair and a couple of days’ worth of beard that hinted of the same color scheme. He was dressed in jeans and sneakers with a Disney T-shirt that didn’t quite meet the needs of his oversized belly.

He looked at the Subaru like it was a Mars rover, then at the Sportsman AutoPilot 120, the newest and most techno-savvy of the Old Town fishing kayak fleet. It is 12 feet long and 36 inches wide, has a removable seat, uses an iPilot GPS-aided directional system, is powered by a 45-pound thrust Minn Kota trolling motor, and comes with a $3,800 price tag. I had it on media loan.

“How do you haul it?”

“I put it on the roof.”

“Ain’t it too heavy for that?”

It is. But when the motor, battery and seat are removed, the weight drops to about 100 pounds, making it manageable. I normally would have hauled it in the bed of my truck, but I had just purchased the Subaru and wanted to drive it.

“Well, yeah, it’s a little heavy for the roof rack. But doable.”

I removed the seat, which slides into a track that makes it adjustable for paddlers of various heights, then released and removed the 24-pound motor from a spring-loaded latch. The battery is anchored in a molded box under the seat. The boat comes prewired, so everything is plug and play. My helper grabbed the bow handle and started to hoist it onto the rear of the car. I stopped him.

“I have a little method to it,” I said while unrolling a thin rubber mat and placing on the top of the rear hatch. The mat prevents scratches. But it also provides the bow of what often is a wet and muddy boat a secure resting place while I hoist the rear and slide it onto the rack.

I grabbed the bow handle and lifted. My helper put his shoulder under the boat, and it suddenly seemed to defy gravity. We soon had it secured. I removed my mask and drained what little was left in the water bottle.

There wasn’t an ounce of breeze. The evening’s heat seemed to intensify.

“I thought this would be over by now,” my helper said. He meant the pandemic. He gestured toward the sweat-stained mask I had in my hand. “I got one in the truck but don’t wear it most of the time. Do wear it some, though.”

I considered my response.

“It probably helps,” I said while looping the straps around my ears and fitting it to my face. “I think it does help.”

I put the motor, battery and seat in the car along with my fishing gear. No one was going to change anyone’s mind about wearing masks here.

“Thanks for the help.”

“You’re welcome.” He stepped forward and extended his hand. I shook it. Courtesy sometimes exceeds CDC guidelines.

Readers may contact Gary Garth at editor@kentuckymonthly.com

SEPTEMBER 2020

David Toczko photo

SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY

Ongoing Car-toon Creatures, Kustom Kars and Corvettes, National Corvette Museum, Bowling Green, through Dec. 31 6

7

1

2Native Reflections Exhibit, Kentucky Native American Heritage Museum, Corbin, through Sept. 10, (606) 526-5635 <<<

3

10 Walk on the Wild Side, John James Audubon State Park, Henderson, (270) 826-2247 4 Kentucky Oaks, Churchill Downs, Louisville, (502) 636-4400 5 Kentucky Derby, Churchill Downs, Louisville, (502) 636-4400

11 Indelible Exhibit, Headley Whitney Museum, Lexington, through Nov. 15, (859) 255-6653 12 Limestone Cycling Tour, in and around Maysville and Mason County, (606) 584-3290

13 NKY Music Fest, Devou Park, Covington

14

20 Rick Springfield, Paramount Arts Center, Ashland, (606) 324-0007 15 Native <<< Reflections Exhibit, Kentucky Wesleyan College, Owensboro, through Sept. 29, (270) 852-3608

16 17

24

18 Vertigo Bungee Jump, High Bridge, Lawrenceburg, (502) 598-3127

25

19 Barnyard Fun!, Oldham County History Center, La Grange, (502) 222-0286

26 Fall Gospel Concert, Mountain Arts Center, Prestonsburg, (606) 886-2623

27

<<< Ongoing What Is a Vote Worth? Suffrage Then and Now, Frazier History Museum, Louisville, through February, (502) 753-5663

a guide to Kentucky’s most interesting events

ON VIEW SEPT 11 - NOV 15 AT THE HEADLEY WHITNEY MUSEUM

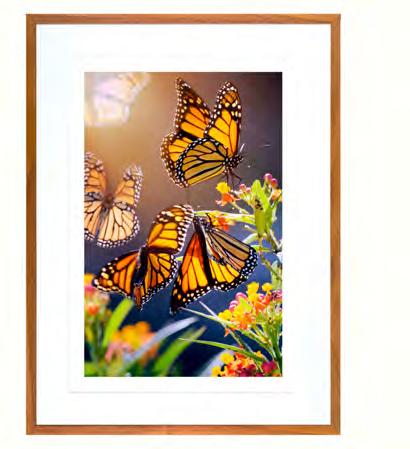

JOHN STEPHEN HOCKENSMITH

Kentucky native, John Stephen Hockensmith, known for his premier skills as an equine photographer, print maker and artist, features "The Chrysalis Project", an artistic journey that chronicles the astounding life and migration of the eastern Northern American monarch butterfly.

INDELIBLE: The Photography of

James Archambeault John Stephen Hockensmith Linda Bruckheimer Deirdre Lyons

Headley-Whitney.org

4435 OLD FRANKFORT PIKE LEXINGTON, KY 40510

Your complete outdoor space...

CERTIFIED, LICENSED & FULLY INSURED

DESIGN PLANS h N A T I V E L A N D S C A P E S + G A R D E N S

PATIOS h WALLS + FEATURES h LIGHTING

h DRAINAGE

INSIDEOUT-DESIGN.ORG

Grant County is just a short drive from anywhere in kentucky. visit and spend some time at Lake Williamstown on a boat ride or fishing at Boltz Lake in Dry Ridge. Grant County is also home to Grant County Park, Webb & Piddle Parks, family-f family-friendly hiking trails and good-natured folks.

Woke—a political term of African-American origin, refers to a perceived awareness of issues concerning social and racial justice. It derives from the expression “stay woke,” whose grammatical aspect relates to a continuing awareness of these issues.

Source: Merriam-Webster.com

The W-word

We were raised learning the Golden Rule: Do unto others as you would have them done unto you.

We were taught that Jesus loves “all the little children of the world.” Everyone knows the first rule of Fight Club is “never talk about Fight Club.” Living with a 19-year-old college sophomore teaches you other dos and don’ts. No. 1 is: No one should ever, under any circumstances, call themselves “woke.” “Stop,” the college student ordered before I even said it. We were discussing the state of the world, from COVID-19 to political upheaval to racial STEPHEN M. VEST injustice. “No. Stop.” Publisher + Editor-in-Chief She could sense what I about to utter, and she wasn’t having it. “Even if you are, you can’t say you are. It’s not for you to say. People can say it about you, but you can’t say it.” “So,” I said, “it’s like giving yourself a nickname?” “What?” “On the Appalachian Trail, everyone has a nickname, but it’s given to you by your hike mates, and you can’t suggest it,” I explained. “Like Howard Wolowitz on The

Big Bang Theory … He wanted his fellow astronauts to call him ‘Rocket Man,’ but instead, they called him ‘Fruit Loops’ because they overheard his mother calling him for breakfast. ‘How-ward, your Fruit

Loops are ready.’ ”

“Not really, but maybe. No,” she said.

“So, what was your nickname?”

“Same as it was in high school—Snail,”

I said.

“Wonder why?” she quipped, implying that I’m not only slow of foot but in evolution.

I told her about living in Baltimore when I was young and taking swimming lessons at an all-Black high school, and about being in the middle of Louisville court-ordered desegregation in the 1970s, and about being a sports reporter covering a historically Black university and being the only White guy on the sidelines and sometimes the lone white guy in the building, and about that time I took the MARTA back to the Atlanta airport with 300 men who had just come from a Louis Farrakhan rally.

“So you can name, what, four days in your life where you felt out of place?” she asked.

I could hear how ignorant I sounded without actually saying any of the things rattling around in my head. I read Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison in high school. I watched Cicely Tyson in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman in 1974. I watched all eight nights of Alex Haley’s Roots in 1977. I cried when Toomer died in The Great Santini. I choked up when Miss Daisy called Hoke her best friend.

Author James Baldwin wrote that segregation is not just being blind to how others live, but having no desire to see. Black activists such as Baldwin knew it was convenient to exhibit a pretense of “wokeness” without its substance. And so “staying woke” was as critical and challenging as “getting woke.”

To be truly woke, according to Baldwin, is to be conscious of the harsh realities of the racial struggle and remain committed. “Listen, Dad, here’s the problem with people your age. You’re like, what, 70-something [I’m 58]? You may think you’re whatever it is that you think you are, but still, you can’t see it.”

“See what?”

“It,” she said. “And as much as you think you understand, you don’t.”

EXTRA VESTED...

Traditionally, the last Saturday in September is a big one for Breckinridge County’s Joseph Holt Home. This year, however, due to COVID-19, there will be no historic baseball game or food trucks.

If the tours of the renovated house are able to continue, which won’t be known until after press time, it will be limited to a few people at a time. So if big crowds put you off, this might be the perfect time to travel State Highway 144 to one mile west of Addison, Kentucky. “It’s been a trying time for all of the Friends of the Holt Home,” said President Susan Dyer. “We’ve worked all year and have waited so long to present noticeable progress,” some of which will need to wait.

Judge Advocate Joseph Holt (1807-1894) presided over the trial of the conspirators in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

KWIZ ANSWERS: 1. B. The distance was shortened; 2. A. 1945 because of World War II; 3. C. Also known as “Bad George,” he killed Special Agent Nelson B. Klein in a 1935 shootout in West College Corner, Indiana, after a cross-country scam in which Barrett would buy a car and steal an identical car, which he then would sell using the paperwork of the first car; 4. A. Clinton, which was formed in 1835 from portions of Cumberland and Wayne counties and named in honor of DeWitt Clinton, governor of New York and the driving force behind the Erie Canal. Why? Why not? 5. C. Union soldiers; 6. B. “Remember the Raisin” was a popular battle cry for Kentuckians. Nine Kentucky counties are named for officers who fought at the Battle of Frenchtown and the subsequent River Raisin Massacre. Eight of them, including Col. John Allen and Capt. John Simpson, were killed. The other counties are Ballard, Edmonson, Graves, Hart, Hickman, McCracken and Meade. Major Bland Ballard, the namesake of Ballard County, was wounded and captured but survived; 7. C. “She’s goin’ to own you”; 8. B. Victor represents the Norse of NKU; 9. C. Nixon said Young’s work was instrumental in breaking down segregation and inequality; 10. B. The United States bought Alaska for two cents an acre.