2 minute read

THE POLYCHROMATIC RE-CONSTRUCTION OF SPACE

-JANHAVI SAVALIYA

Advertisement

In spring of 2021 I was lucky enough to take an elective called “Polychromatic Reconstruction” taught by David Gissen. Polychromatic reconstruction typically describes the practice of visualizing the lost, colorfully painted surfaces of ancient classical sculptures and buildings. This seminar examined this practice through a much wider range of case studies and through a far broader concept of color recovery. The course explored polychromatic reconstruction globally and historically, in world-wide ancient and modern artifacts and environments; materially, by understanding the histories of colorants and their production; environmentally, by understanding the role of light and air pollution in color transformation; theoretically, by exploring pre- and post-Newtonian theories of color perception; politically, by understanding how the practice often becomes entangled with contemporary debates about subjectivity, race, and disciplinarity; and culturally by understanding what character and values it imparts on a surface. Throughout the course, we had discussions on monochromaticity, etiolation, colorization and commercialization, sexuality, disability, media and reproduction, ideas about dirt and cleanliness, formalism, while questioning lifestyle and traditions. It was also emphasized enough during the seminar, that color is not a rainbow, but a site through which culture imparts some of its most explicit cultural and political attitudes into concept of human perception.

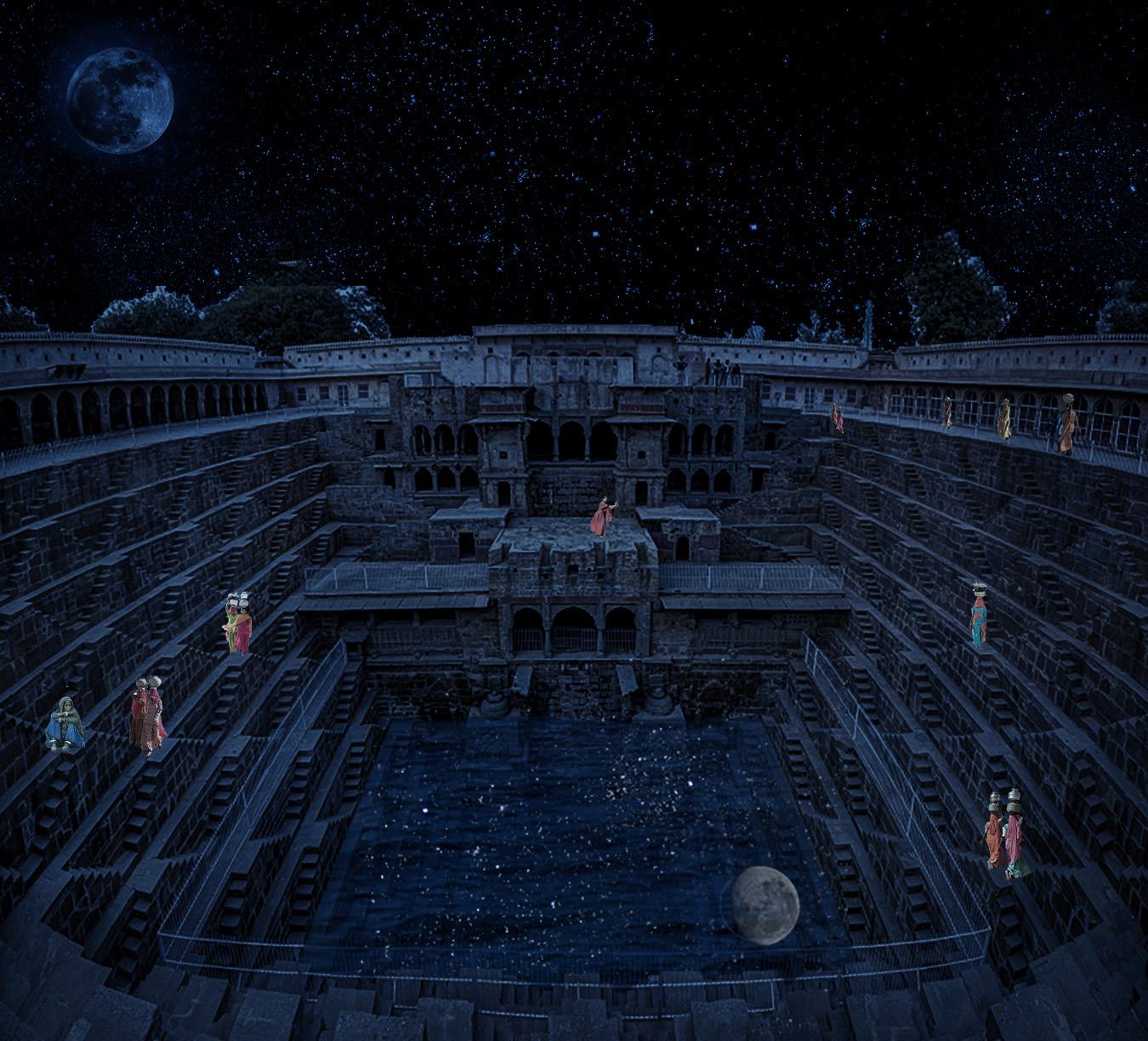

He asked us to investigate a case study or area of interest in relation to the reconstruction of color in built form, and throughout the first half of the course, I couldn’t stop thinking about the stepwells of India, being some of the most colorful (physically and culturally) lost treasures of India. I have always tried to relate my education here with Indian architecture, this seemed like the perfect subject for this project. Choosing the case of Chand Baori – a kund in Rajasthan, it was entrancing to see how the scarcity of water required them to innovate and build these structures using complex mathematical calculations, becoming a public social space while the still water serving additional purposes like being used as a tool for readings of the cosmos. What was most intriguing during my investigation was imagining how the structure would have looked when filled with individuals dressed in color Rajasthani fabrics and the visual character that adds to a space.

This is where I could more fully develop my ethical or critical attitude towards the reconstruction process. Yes, it was exciting to imagine what things looked like or could look like, but it was even more exciting to bring some critical perspective to this activity. The how, when and why (s) brought out the most interesting discussions to the table.

Illustrations by Jeet Gajera

janhavi.savaliya.10@gmail.com

Parsons School of Design/ The New School University Spring 2021