Dipartimento di Architettura, design e urbanistica

PIANIFICAZIONE E POLITICHE PER LA CITTÀ, L’AMBIENTE E IL PAESAGGIO

Università degli Studi di Sassari

SUPERVISORS

50038015 URBAN VALORIZATION OF THE ARCHEOLOGICAL HERITAGE OF SINNAI IN SOUTH-EASTERN SARDINIA

: PROF.SILVIA SERRELI DR. DANILA ARTIZZU STUDENT: KHALDA BOUCHAALA MATRICOLA:

Nuraghe Sorolo-Birori

EUROPEAN MASTER PPCEL PLANNING AND POLICIES FOR CITIES, ENVIRONMENT AND LANDSCAPE

The protection of heritage, as a historic sanctuary, does not necessarily lead to its exclusion from the landscape and contemporary uses. On the contrary, valorization passes through a landscape integration of archaeological structures in harmony with the environment and whose past, present and future functions have been thought out.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS •5 METHODOLOGY •6

INTRODUCTION •7

PART I__________________________________________________________________•8

1.HERITAGE: CONSERVATION AND PROTECTION •9

1.1Presentation •9 1.2.The enhancement of cultural heritage •10 1.2.1.Protection •11 1.2.2.Conservation •11 1.2.3.Valorizzation •12 1.3.Continuity and Inclusion •13

2.HERITAGE AND THE TOURISM OF WALKING •15

2.1.Multi-motivational tourism •15

2.2.Walking, Nature and Sustainability •17 2.3.Walking and outdoor recreation and sports activities •18

3.HERITAGE AND MONUMENTS: THE NURAGHI •19

3.1.Typology •19

3.1.1.The Protonuraghi •19 3.1.2.The simple nuraghi •22 3.1.3.Complex nuraghi •25 3.1.4.The Tombs of Giants •28 3.1.5.The spread of the nuraghi •30

3.2.Statistics about the Nuraghi •33 3.2.1.Distribution of the nuraghi by altitude •33 3.2.2.Distribution of the nuraghi by province •33 3.2.3.Distribution of the nuraghi by type •33

4.CONCLUSION •34 Part II____________________________________________________________•35

5.LOCAL HERITAGE: THE CONTEXT OF SINNAI •36 5.1.General situation •36 5.2.The Cutural Aspect of Sinnai •37 5.3.Transportation and Accessibility •40 5.4.The geographical and morfological aspect •42 5.4.1.Location and geographical characteristics of the territory •42 5.4.2.Geomorphological traits •42 5.4.3.Taxonometric map of the land of Sardegna •43 5.4.5.Hydrographic basin •46 5.5.The Historical aspect •47 5.5.1.The territory of Sinnai: The Nuraghi and Giants tombs’ spread •47 5.5.2.Table of the different nuraghi and their types in Sinnai •49 6.CONCLUTION •51 Part III___________________________________________________________•52

7.REGIONAL LAWS FOR THE PROTECTION OF ARCHEOLOGICAL FINDS •53 7.1.Enhancement of the areas characterized by historical settlements •53 7.2.Perimeter of protection •54 7.2.1.Perimeter with integral protection •54 7.2.2.Conditional protection perimeter •55 7.2.3.Relational Perimeter •55 7.3.Programmatic lines of the municipality of Sinnai •56 7.4.Nuraghi along in the Cultural/historical Walk-Along •58 7.5.Sinnai and its old roads •59

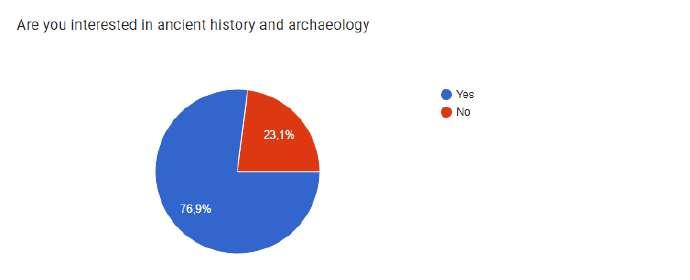

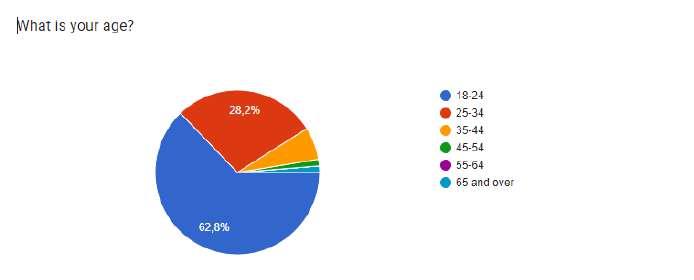

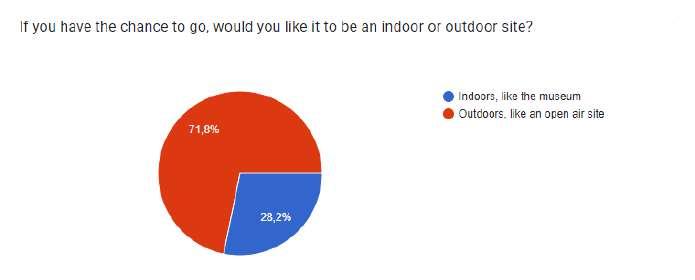

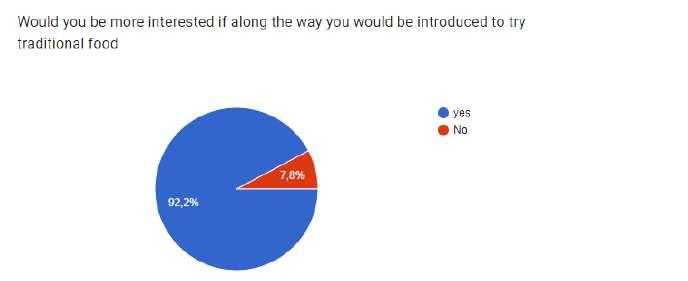

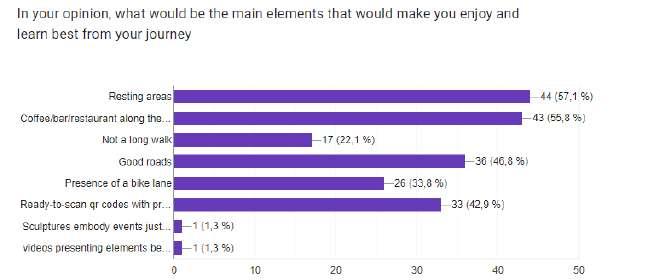

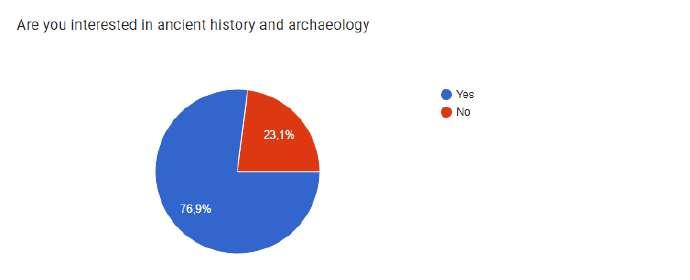

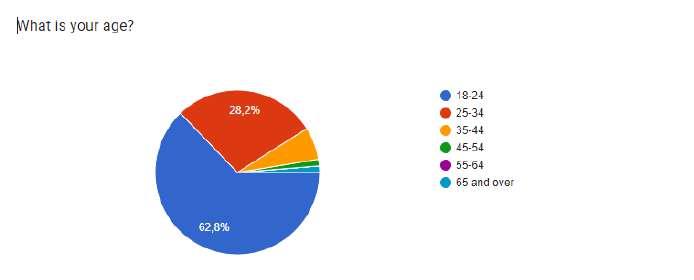

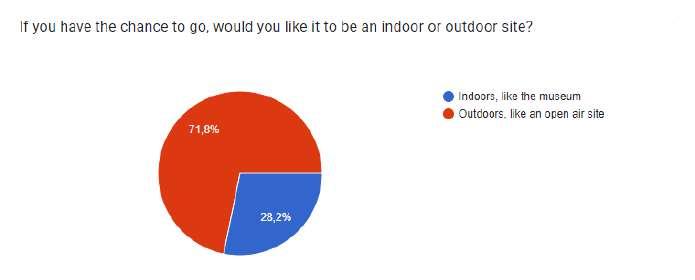

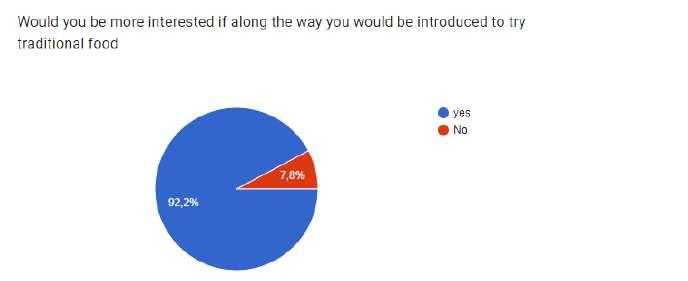

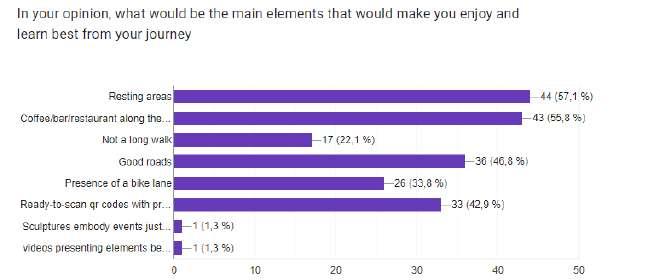

8.SURVEY CONDUCTED •63 8.1.The questions asked •63 8.2.Replies and statistics •64 9.CONCLUTION •66

BIBLIOGRAPHY •68 Books •68 Scientific articles, Thesis and magazines •69 Sitology •70

4

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my deep gratitude to my parents who were, are, and will always be there, my brother and sisters and all my family and cousins who stood with me and helped through all the dark and hard times these years.

I would also like to thank my professor and superviser, Silvia Serreli and dr. Danila Artizzu, who gave me the chance and helped me achieve the work on this subject, in which I have been, and will always be interested. Their expertise was extremely valuable in formulating the research questions and methodology. Both their patience, and insightful comments pushed me to refine my thinking and to learn about some very great and new aspects in the field of the valorization of the historical archeological monuments, and to learn about the great and yet to discover history of this beautiful island, our Tunisian neighbour, Sardegna. And for that I am are very grateful.

In the hope of further associations with them.

5

METHODOLOGY

This thesis is a form of Inductive research, It is an observational study that examins some theoretical aspects and later focuses on achieving a project while respecting the results. It is divided on three main chapters.

In the first one I will discuss how to protect the archeological and cultural heritage in Italy, a new type of tourism that induces the vaorizzation and conservation of this heritage, and then we present a definition of a specific type of archeological heritage, which is the Nuraghi.

In the second part I will conduct different types of analysis on Sinnai, the local heritage context perimeter of study. I will be investigating the geografical, morfological, hydrografical and historical aspect.

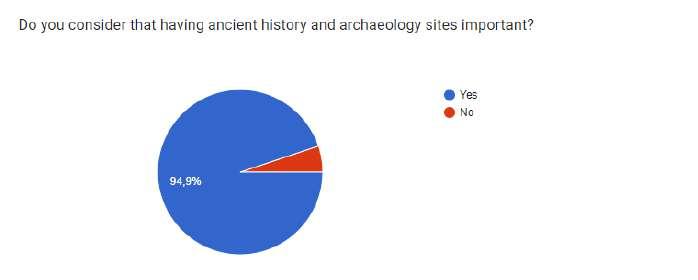

The third part would be the implementation of the project while considering all the inqueries conducted in the first and the second part. I will mention the ways of the protection and enhancement of archeological goods in the regional laws of Sardegna. I also conducted a survey on social media to define the interest of different slices of society in the historical monuments and their value, and I asked more specefic questions that would help me understand more their view and how the project should give a better experience.

6

INTRODUCTION

As it has the largest archeological and historical base in Europe, Italy made it a fundamental principle to enforce the duty to preserve cultural goods, we found that the art. 9 of the Italian Constitution speaks loudly about it : “The Republic promotes the development of culture and scientific and technical research. It protects the landscape and the historical and artistic heritage of the Nation.”

In Sardinia, archaeology is perceived quite extensively as one of the elements capable of proving a specific identity; The island has peculiar characteristics, with a nuragic culture specific to it, which makes it an interesting case of study to take stock of the forms and methods of an archeology in the goal of involving the participation of local communities.

There have been many excavations with groud-braking finds, and until this day this topic is still ambiguous and opens the door to discover a rich unprecedented heritage, unknown to the rest of the world, and for which exists a need for the development of simple urban methods that would help identify, protect and value these historical goods. When archeological artifacts are found, governments would take and put them in a museum or; in the case of big or architectural heritage; create a limited area for people to visit.

It is a complex process to promote the culture of safeguarding and enhancing cultural heritage with the new demands of everyday life. Cultural and historical identity cannot be decontextualized, and safeguarding and restoration actions must necessarily be followed by effective valorization procedures to enable that heritage to best express its potential.

It goes without saying that we cannot envision a generalized museification of the area because valorizzation does not mean halting territorial development or raising the value of a cultural asset; rather, it means expanding its potential for knowledge, enhancing its modes of enjoyment, and integrating it into the urban fabric. Therefore a study of a new way of presentaion of the archeological Sardenian treasures, most specifically in sinnai, one of the biggest municipalities in Sardinian, would enhace the attention and create more study opportunities and funds to better understand the history of this land.

So how can we brin this heritage closer to the city and include it to its modern fabric? What are the laws and the methods used for their protection and valorizzation?

7

Part I

1.HERITAGE: CONSERVATION AND PROTECTION

1.1.PRESENTATION

Art. 9 of the Italian Constitution: “The Republic promotes the development of culture and scientific and technical research. It protects the landscape and the historical and artistic heritage of the Nation.” This is a famous Article of the Constitution of the Italian Republic, inserted in the first 10 articles that constitute its fundamental principles, written in 1946 to enforce the duty to preserve cultural goods. The notion that cultural and environmental assets make up Italian cultural heritage, also known as historical and artistic heritage, is one of the legal concepts enshrined in Italy. Thus, cultural heritage is recognized as a national treasure.Although archaeological legacy is also a valuable economic asset, this definition falls short when compared to the intangible value of culture, without which everything is worthless because it has a significant impact on people’s quality of life. Each archeological site conceals the possibility of cross-cultural and cross-perspective exchange as well as the danger of building new walls in the name of an identity that is claimed with an eye to the past. When we observe the depth of time through the eyes of a historian, we discover that identity is no longer a static fact that must be exposed but rather a dynamic state that is the outcome of a process of shared experiences. In fact, archaeology is a powerful tool that fights forgetfulness by persistently reinvigorating the goal of critical understanding of the past, to rebuild the causes of cultural distinctions, and to comprehend the complexity of the present. Even if these locations are far away, the urban planner is nonetheless responsible for creating a connection between the built environment and the city. Instead, it must include them into the inhabitant’s essential experience.TThere are no short cuts when it comes to memory retention when it comes to human history, and its preservation is a crucial component of a larger effort to improve quality of life. In this regard, archeology can show how to balance this safeguard with the more general objectives of the community. Before assigning value, consider whether the item is actually worthwhile. The ability to interpret and reintegrate what is left of the past into the life of a current citizen should be the foundation of an urban planner’s design function in order to

9

give it meaning. For this, valorization is an essential social function that recognizes a nation’s capacities to preserve and make present its cultural heritage at all public, associative, and private levels where civil society is articulated.What is the cultural worth of archaeological artefacts, one could ask? Why do you want to study, preserve, and improve them? Why generate new generations to carry on doing this? These questions don’t have a single, much less a straightforward, response.If not fundamental to the human species biologically, then certainly culturally, the study of the past is. We could consider the health of the cultures that believe they can do without the past and a thought on how to relive it in order to understand this kind of study. Archaeology starts from the “things” of the past, because they talk about ancient civilisations and help us understand ourselves; and our present nature, in response, it helps us to make sense of the “things” that were, prehistory, antiquity, the Middle Ages, modernity, present, and themselves to us, even before being fields autonomous research, structured in their disciplines, as an uninterrupted flow, which preserves here and there the fragments of an infinite puzzle, which once recomposed, if it were recomposable, it would give us back the fantastic image of our being of yesterday, today and tomorrow.

1.2.THE ENHANCEMENT OF CULTURAL HERITAGE

The three main practices that govern the appropriate management of cultural heritage are protection, conservation, and enhancement. These three actions are clearly defined both at the regulatory level and in the current legislation, but they also exhibit levels of interconnectedness in practice, as if they had become a single guiding principle that must always be kept in mind when carrying out any operations on cultural heritage.

*Protection is any action taken to identify, guard against harm, and keep alive a piece of our cultural heritage so that everyone can benefit from it and enjoy it. It is therefore expressed in: recognition; protection; conservation.

*Conservation: Conservation is any activity carried out in a cogent, planned, and coordinated manner with the intention of protecting the identity, integrity, and functional effectiveness of a cultural asset. It is therefore expressed in: study; prevention; maintenance; restoration

10

*Valorization: Also called enhancement is any action taken to raise awareness of cultural heritage, aid in its preservation, and encourage public use in order to spread the ideals that this legacy represents. The State has sole authority over protection, and it sets the regulations and implements the administrative safeguards required to ensure it. The State and the region work concurrently on enhancement, and it also allows for private subjects to participate.

1.2.1.PROTECTION

We only have a partial understanding of the delicate, finite, and non-renewable resource known as archaeological heritage. The scope of what needs to be explored beneath the surface of the sea, inside structures, or in the ground is unimaginable to comprehend. A heritage of great scientific importance includes both moveable (items) and immovable (man-made structures or often visited natural places, such as prehistoric ornate caverns) archaeological remains. They might be intentionally stored in place or collected during excavations. Archeologists make up the soil’s archives, whose scientific study is essential to advancing our understanding of the past. The preservation of the remains is the biggest challenge. This history is, in fact, being severely eroded by both natural and human factors (agricultural work, land use planning, growing urbanization, but also looting). The State has set up a legal system to protect the archaeological resource and has oversight over the research.

1.2.2.CONSERVATION

Metal detecting surveys and excavations are prohibited, as is the exploration of any underwater wrecks or other underwater remnants without prior license for each of the aforementioned activities. Accidental finds must be reported right once to the mayor of the municipality where they were made, who then notifies the prefectural services (regional directorate of cultural affairs or regional service of archaeology). In response to a public service mandate, the State ensures a scientific and technical control on the remains throughout the entire operating chain of archaeology, whether through monitoring the state for study, preventive conservation, storage in specialized buildings (depots, Conservation and study centers, museums, etc.), or management of their documentation. Additionally, the

11

State guarantees that these remains’ movements are under control (for analysis, studies, valorizations ...). Finally, it helps to keep protected archaeological sites intact.

1.2.3.VALORIZZATION

The Superintendence’s institutional responsibilities include enhancing the architectural and natural heritage in accordance with Article 6 of the Code of Cultural Heritage, which states: “Enhancement consists in the exercise of functions and in the discipline of activities aimed at promoting knowledge of cultural heritage and ensuring the best conditions of use and public enjoyment of the heritage itself, in order to promote the development of culture. It also includes the promotion and support of cultural heritage conservation interventions. With reference to landscape assets, the enhancement also includes the redevelopment of buildings and areas subject to compromised or degraded protection, or the creation of new coherent and integrated landscape values. The enhancement is implemented in forms compatible with the protection and such as not to prejudice the needs. The Republic favors and supports the participation of private subjects, individual or associated, in the enhancement of cultural heritage”. The exercise of functions and the discipline of activities aimed at promoting knowledge of cultural heritage and ensuring the best conditions for use and public enjoyment of the heritage itself, as provided for in Chapter II “Principles of the enhancement of cultural heritage” art. 111 and 112 of the Code, constitute the enhancement, which also manifests itself through the close relationship with the interventions of cultural heritage. In order to foster a sense of identity, connection to the community, and respect for Italian heritage, the enhancement also includes educational goals aimed at developing and enhancing understanding of the historical, artistic, architectural, and cultural legacy of the area of competence. The improvement involves numerous levels and various sorts of cooperation. In order to strengthen and improve local identity, the enhancement’s special goal is to offer guidance and encourage the coordination of excellent collaboration practices for the administration’s outlying structures functioning in the area as well as for other administrations and local authorities.

12

1.3.CONTINUITY AND INCLUSION

In 1954, Ernesto Nathan Rogers, added in the issue no.199 of CASABELLA journal, the word continuity over the old masthead title, he wanted, above all, to recall the commitment in accepting Pagano and Persico’s legacy, in the hope of subsequently carrying it out. The Editorial continued: “Continuity signifies historical consciousness, i.e. the true essence of tradition, in the precise acceptance of a tendency lying in the eternal variety of a spirit adverse to any past or present formalism. A dynamic continuation and not a passive recopying; not mannerism, nor dogma, but free and open-minded research with constancy of method”. Continuity, therefore, over time and space, in a tradition in which architecture is foundering, is in the reality of existing, in its historical concreteness. We can explain the concept of continuity as a gradual transition from one state to another through all intermediate states; continuity is a processus in that advancement, it is moving with progress. We refer to the archeological sites as, stratified, monument, memorial places and traditions. The historical monument represents a memory, a testimony, a document of glorious events, illustrious people, what remains of vanished ancient civilizations, works of art and a genius that represent an exemplary era, and an author. The historical sites are the place of memory as a process linked to the genesis of a modification of a substrate, whether organic or not, through which a certain effect persists and becomes susceptible to reappearing in the course of further occasions. It is in particular, the psychic function, that in man reaches full development, to reproduce past states of consciousness in the mind (notions, sensations, images), to recognize them as such and to locate them in time and space. A historical site is the place of old tradition, knowledge and values looking for a way to be studied, understood and transitioned. The archaeological sites are places of memory, myth and history; they are areas where it is possible to find remains of the past, often stratified, of missing cities, of once living and working centres, once abandoned or destroyed, finally naturally submerged or still stripped down by man. These sites are places that are constrained by our laws, subject to protection and conservation, yet one wonders why these places, in addition to piqueing the curiosity of academics, have recently drawn increasing numbers of tourists from many cultures and origins. The question could be answered simply by citing a variety of

13

reasons or by stating that archaeological sites are locations where myth is more powerfully present than in a museum and has unbroken authority in Western culture. Salvatore Settis noted recently that “the space in which we live in is a formidable cognitive capital that builds the collective identity of communities. Territorial fragmentation, violent and fast modification of landscapes, the spread of periphery-sprawl, the multiplication of ruins, landfills, non-residual places, eradicating acquired identities and modifying behaviours, marking the body of society with indelible wounds” (Settis, 2017). In the last few years the peoples’ interest in visiting and enhancing the archeolocical sites have gone less and less. While the urban life has been degraded, a tired rationalism marks many cities, the citizens are taking a distance from every site that is at a little distance way from where they live, and we, as urban planners hold onto responsibility to recreate that link between the urban and the rural, the modern and the ancient. Giving to these distant historical sites their identity, including them, making them accessible. Such process gives positive hope for the foreseeable future.

14

2.HERITAGE AND THE TOURISM OF WALKING

Activities involving walking are among the most well appreciated recreational pursuits in many European nations, where there is a growing demand for vacations that allow for immersion in the local natural and cultural contexts.

2.1.MULTI-MOTIVATIONAL TOURISM

According to current trends in post-industrial tourism, which looks for proposals for extremely personal experiences capable of forming the identity of the person or tribe to which they belong, trekking and, more generally, the various forms of walking tourism are positioned as an antithesis to general tourism. Unlike the times and forms of traditional tourism, walking allows you to appreciate the natural environment, the landscape, and the imprints that history, art, traditions, and economic activities have left on them while straying from the routines and traditional visit routes. Walking can even be as physically demanding as participating in sports.

A slow journey through colors, tastes, scents, feelings, and suggestions is made possible by the possibility of developing a more genuine relationship with people and their traditions. It is an environmentally friendly form of tourism that combines a variety of motivations, which vary greatly from person to person. Not so much in the sense of “luxury tourism” with a high tendency to spend, but rather of authenticity and originality of emotions and lived experiences, is the kind of tourism that can improve small towns and outlying areas while simultaneously bringing fresh demand to the most popular places.

A tourist industry that needs support from the supply chain in the form of infrastructure, information, and tailored services, as well as a welcoming environment that is attentive to its requirements. In actuality, environmental, cultural, social, and managerial aspects of a destination’s governance that change through time and space have a significant impact on walking tourism.

The most popular travel destinations are cultural excursions. Different types of users’ experiences are directly impacted by

15

the planning and management of these aspects. According to two levels of motivating intensity, the relationship between tourism and the practice of walking is configured: as the primary factor determining the trip or stay or as an accessory element, thereby materializing in lines of offer diversified:

- holidays with a theme and unique interests.

- active vacations (a rapidly expanding, highly varied industry that includes both a sizable number of small operators and specialized brands from major companies).

- vacations centered on the pursuit of wellbeing, relaxation, and a lifestyle in contrast to daily life in urban and professional settings.

- short breaks.

- Customary celebrations and vacations that provide for the chance of engaging in outdoor activities, among which walking is given priority. Walking, as we’ve already mentioned, is essential to achieving a variety of goals, and as a result, it manifests itself in a wide range of ways during a tourist experience, moving along an ideal continuum that ranges from a short, easy stroll on a flat path to a real trek lasting several days that calls for more effort and preparation. The base’s components appear to be, when mixed in various ways:

- the necessity of “slowness,” interpreted as a strategy to discovering a region in its particularity of natural and social ecosystems (examination of natural and human surroundings); exploring and learning about its history.

- contact with nature. physical involvement, which is best satisfied by engaging in outdoor activities or seeking out adventure. We can refer to “tourism of walking” because the experiences that these travelers seek and have when they decide to travel on foot are not reducible to a single type but instead fall under a larger category that is only loosely defined by terms like “outdoor sports tourism,” “hiking tourism,” “active tourism,” “outdoor tourism,” “mountain tourism,” “nature tourism,” “ecotourism,” “slow or gentle tourism,” “religious tourism,” etc. Research shows it’s particularly useful to examine the linkages between the leisure activity of walking and certain categories of tourism, including adventure, nature, and outdoor sports tourism as well as cultural tourism.

16

2.2.WALKING, NATURE AND SUSTAINABILITY

Currently, huge portions of the people in Western-style countries and enterprises consider tourism, nature, outdoor sports, and leisure activities to be essential components of a high quality of life. A basket of supply lines characterized by a declared attention of destinations and companies to environmental and historical quality and its protection opens up when tourism is combined with attention to sustainable forms of development and fruition of natural environments, more or less anthropized. These supply lines include offers specifically created to meet the demand for direct, personal, authentic experiences with the nature and culture of a particular destination. On a global scale, nature tourism frequently merges with the idea of ecotourism, which, according to the International Ecotourism Society (TIES), encompasses all types of travel and vacation to natural regions that guarantee environmental preservation and enhance local populations’ well-being. Therefore, the ecotourist is an experienced traveler, an adult with a high level of education and income, and frequently qualified to serve as an opinion leader in their reference group.

The Observatory on Nature Tourism, run by Ecotour, chooses a more expansive definition of nature tourism at the national level in Italy. It is described as a “segment that tends to development of natural resources and protected areas, but at the same time it holds in a big consideration of cultural and architectural heritage, local traditions, folklore, typical products, artistic and traditional craftsmanship, living in contact with nature, practicing sports in uncontaminated enviroment” (Ecotour, 2008). In addition to highlighting the distinct difference between ecotourism, which is based on the three key factors of environmental sustainability, nature protection, and contribution to the development of socioeconomic conditions of the local populations, this definition seems better suited to address the growing trend from a portion of the tourist demand to integrate together cultural and immersion experiences in nature.

These most cutting-edge nature tourism strategies, which undoubtedly highlight the immense potential, must discount, similarly to what occurs for walking tourism, the extreme divergence of consumption motivations and

17

forms, which determine an inhomogeneity of the proposed activities and of the consumer groups to whom to propose them: from walking to trekking, from pilgrimage to spiritual tourism, from cultural tourism to gentle tourism, et cetera.

2.3.WALKING AND OUTDOOR RECREATION AND SPORTS ACTIVITIES

The term “walking” is frequently used in specialized literature to refer to “activity,” “outdoor enjoyment,” and engagement in sports tourism (Hinc and Higham, 2003). The placing of leisure activities, such as walking, in a natural setting is the basis of outdoor recreation. These activities are frequently categorized as sports (such as trekking, Nordic walking, and orienteering) or can be taken on as “adventures” (adventure tourism). However, it should be noted that outdoor recreation and sports tourism do not entirely overlap; in fact, many tourist activities that take place in a natural setting (such as hiking, walking, and other similar activities) are not sports activities or are carried out outside of the rules of organized competition (presence of rules, competition, specific equipment, etc.). Sports based on nature (green sports) are created in the area of sports tourism by fusing physical activity with particular environmental characteristics. As a result, they have their roots in the presence of a particular type of natural environment in a tourist destination, which must be avoided or at least have any negative effects on it minimized in order for the tourist industry to continue to develop sustainably.

Due to this, it is necessary to assess the degree of compatibility between various sports and the preservation and improvement of the natural and historical environment during the design phase of infrastructures and supply lines.

Concerns resulting from concurrent use for practices should also be taken into account. Different sports may be practiced in a given environment and/or infrastructure. For instance, a trail network may be used for hiking, mountain biking, and/or horseback riding. It’s possible that the repeated use of the same infrastructure will have an impact on the physical security of various users. The mental state in which they are done by individual practitioners, the peculiarities of the natural settings, and the ideas and feelings that the presence in a territory as a whole have all direct bearing on the experiential value of outdoor sports and activities.

18

3.HERITAGE AND MONUMENTS: THE NURAGHI

The nuraghe is the building that characterizes the civilization developed in Sardinia since the Middle Bronze Age and which takes its name from it (Lilliu G. 1962; 1982; 1988; Contu E. 1981; 1998a). In the classical typology, known as “nuraghe a tholos”, it differs significantly from the nuragic structures that preceded it: the “protonuraghi”, recently redefined as “archaic nuraghi” (Ugas G. 2005, p. 70). Precisely from the evolution of the latter, in a phase of the Middle Bronze Age on which scholars still discuss, between the seventeenth and sixteenth centuries BC, we will come to the definition of the module of the nuraghe

3.1.TYPOLOGY

3.1.1.THE PROTONURAGHI

In Sardinia, starting from the Middle Bronze Age, if not at the end of the preceding phase, are scattered on a vast territory those constructions known as nuraghi, which characterize the Sardinian landscape and a protohistoric “civilization” among the most original and complex of the Mediterranean due to their size and abundance. The protonuraghi, as they are referred to, are architectural constructions that have been variously labeled over time as “abnormal nuraghi, false nuraghi, pseudonuraghi, gallery nuraghi, nuraghi-nascondiglio, anomalous or aberrant nuraghi, corridor nuraghi, protonuraghi, archaic nuraghi” to denote from time to time a relationship of similarity or formal diversity, chronology, or function. Some view it as archaic architecture, the beginning of an evolutionary process that will eventually give rise to the classical nuraghe, while others hold that both forms are modern and differ in construction for reasons other than chronological ones. In terms of architectural grammar, these are structures for civil use that display a range of planimetric shapes (circular, elliptical, triangular, trapezoidal, and polygonal), work walls that are typically unfinished and as high as 10 meters, and occasionally with several entrances. The interior is made up of flat-banded halls, stairwells going to the lofty floor, nooks, as well as little habitats that have been transformed into orbs. From extensive constructions on the ground but not very spacious and poorly articulated inside, from the wall mass prevailing over the voids and

19

irregular plans, it tends, through a evolutionary process, with elliptical-circular shapes with environments more favorable to live in. More particularly, they have a central chamber covered with a projection, “a donkey’s back” or an inverted ship’s keel. The spread of these monuments mainly affects the central-western area of the island, the same touched by dolmenic megalithism (dolmens, allées couvertes, tombs of giants) and characterized by from a historical landscape to a prevalent pastoral economy.

20

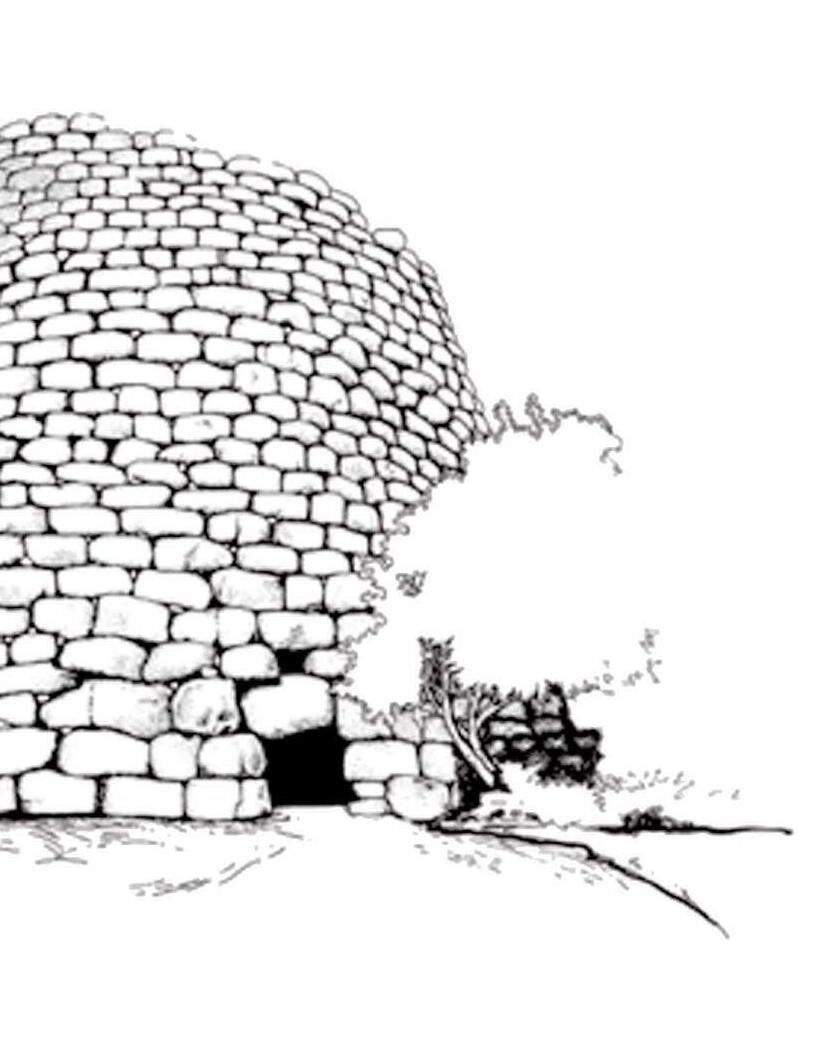

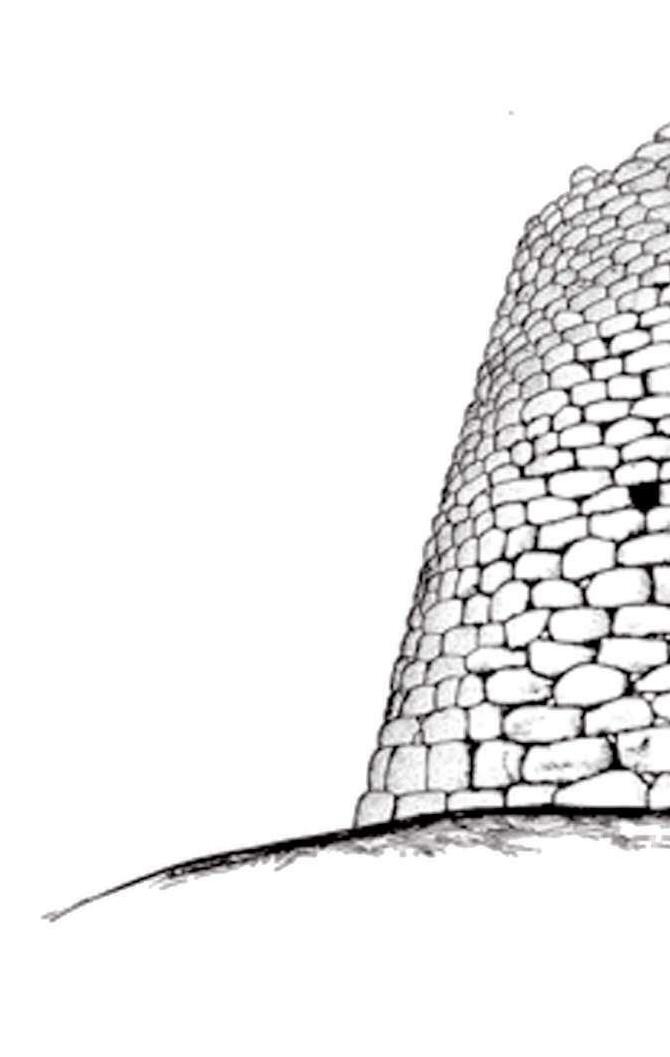

1-Protonuraghe Bardalazzu Dualchi, Nuoro Source: Catalogo dei siti, p313, La Sardegna nuragica

2-Plans of protonuraghi

Source: Alberto moravetti p14, Sardegna Nuragica

1. Cabras-Dualchi.

2. Pedra Oddetta-Birori. 3. Coattos-Bortigali. 4. Mulineddu-Sagama. 5. Funtanedda-Sagama. 6. Tusari-Bortigali. 7. Frenegarzu-Dualchi. 8. Mene-Macomer. 9. Seneghe-Suni. 10. S’Ulivera-Dualchi.

11. Ono-Dualchi. 12. Lighedu-Suni. 13. Gazza-Bolotana. 14. Giorzi-Pozzomaggiore. 15. Corcove-Orotelli. 16. Orgono-Ghilarza. 17. Sumboe-Ghilarza. 18. Crastu-Ghilarza. 19. Fraigata-Suni. 20. Izzana-Aggius.

21

3.1.2.THE SIMPLE NURAGHI

The nuraghe is a modular structure whose shape and size are determined by the number and placement of replicas of the fundamental module. This last one is a truncated cone structure constructed by carefully stacking stones, with a circular space with a roof in tholos always inside. The walls are made of different sizes of stones: the largest blocks are generally inserted at the foot of the building, sometimes forming a kind of base, while the smaller stones are destined for the upper part of the tower and in many cases, they are worked, sometimes with great care (the “isodome” technique), to obtain segments with a characteristic “tail” or “T” shape, which ensures a better insertion in the curved profile. The materials, on the other hand, were mostly made of raw stones found on the site or taken from the rocky banks and roughened. The nuraghi wall structures are realized with ordered rows of stones arranged in alternating assizes, with a rather advanced superimposition criterion. The tower walls have a more or less noticeable slope, usually of the order of 10°, which is not always constant but drops sharply in the top part of the structure. The piece’s module can be replicated vertically, at least on three superimposed levels, giving birth to skyscrapers of enormous height. Unfortunately, because no nuraghe has retained the upper part complete, it is impossible to determine what the greatest height of a Nuragic tower may have been and how many superimposed chambers it could have housed. The entrance, built with great care, is the most architecturally significant piece of the wall’s outer face: it is very definitely here that the “first stones” of the building were laid and the remainder of the wall’s texture adapted to it. The building of the architrave and the stones of the jambs on which it was to rest received special care. The architrave stone, usually powerful, was frequently arched to laterally ease the weight of the overlying walls; in other situations, it was cut into the underside to expand the light of the entry; and on occasion, it may be a rebated leaf for the door on the inside side. Other compartments can be gained inside the walls, often on the floor of the upper floors or along the course of the staircase: these are generally silo storage rooms with top access, sometimes with small apertures to the outside. Some uncommon nuraghes feature underground rooms that are partially or completely sunk into the rock and are sometimes accessible by descending stairs. A well for water is dug in the small underground environment.

22

3-Nuraghe Corbos-Silanus, seen from above Source: Paolo Melis, p 30, La Sardegna nuragica

23

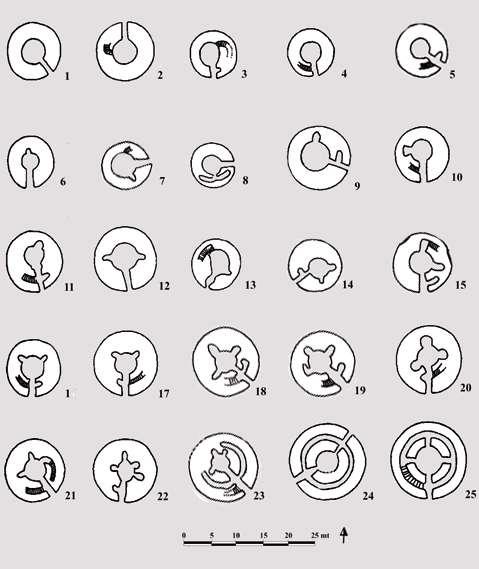

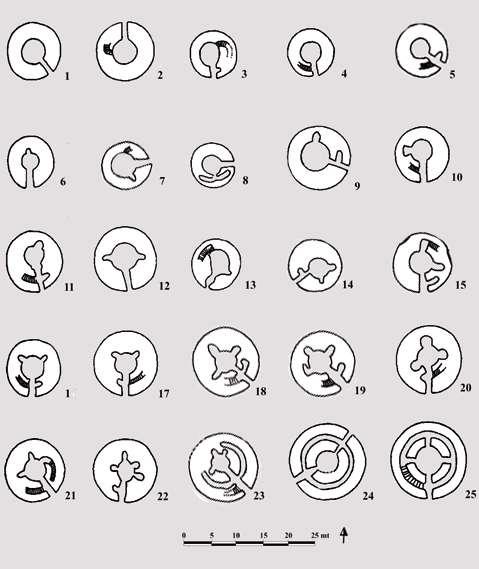

4-Plans of simple nuraghi

Source: Paolo Melis, p 30, La Sardegna nuragica

1. Orrùbiu-Arzana.

2. S’Iscala ’e Pedra-Seméstene.

3. Baiolu-Osilo. 4. Mindeddu-Barisardo. 5. Genna Masoni-Gairo. 6. Sa Domo ’e s’Orku-Ittireddu. 7. Nuraddéo-Suni. 8. Marosini-Tertenia.

9. Muru de sa Figu-Santulussurgiu. 10. S’Attentu-Orani. 11. Molafà-Sassari. 12. S’Omu ’e s’Orku-San Basilio. 13. Karcina-Orroli. 14. Gurti Aqua-Nurri. 15. Sa Pedra Longa-Nuoro, 16. Su Fraìle-Burgos.

17. Giannas-Flussìo.

18. Madrone o Orolìo-Silanus. 19. Tittirriola-Bolotana.

20. Abbaùddi-Scano Montiferru.

21. Sa Figu Rànchida-Scano Montiferru. 22. Sa Cuguttada-Mores. 23. Murartu-Silanus. 24. Leortinas-Sennariolo. 25. Santu Antine-Torralba.

24

The typical “monotower” tholos nuraghe characterized the archaeological landscape of the island in the first period of its diffusion. Some scholars think that the idea of replicating the model horizontally was reached later, giving life to multi-vaulted nuragic complexes of various shapes and sizes. The type of addition can foresee the addition of one to five towers, almost always smaller than the tower of origin, which had to stand out on the entire complex, generally in a clear and imposing manner. Secondary towers can lean against the keep individually or be joined by curtains, straight or sinuous, to form a genuine bastion with turrets that encompasses the tower in center position. The various degrees of articulation of the Nuraghic complexes appear to reveal signs of a hierarchical territorial organization. The dimensions of these complexes can be rather remarkable: the tribe of Santu Antine-Torralba measures around 39 m on the two axes, while the diagonals of the rhomboid that distinguishes the design of the plan of Su Nuraxi-Barumini measure 40x35 m. Aside from the numerous examples of Nuraghic complexes that follow, to some extent, the regular patterns mentioned thus far, there is an equal, and perhaps even preponderant, number of structures that could be defined as “irregular,” though this term, referring to Bronze Age architecture, has little meaning. There is generally always a well for the water in the courtyards, but in some nuraghi, there are others, located in different rooms of the bastion: Santu Antine-Torralba has three wells. The towers of the bastions are connected by corridors that lead to the court or, if that is not possible, to the bastion’s entrance; in some nuraghi, corridors also lead to the upper floors (Santu Antine-Torralba, Voes-Nule). The bastion towers can be distinguished from the curtain walls. In some bastions of complex nuraghi, but also in some monotours, traces of reconstruction of the walls have been found: in particular the powerful nuraghe Su Nuraxi-Barumini (width 3m; altitude 7m), which has obliterated the original entrance and has therefore obliged the inhabitants to use a staircase to reach the new opening, located at 7 meters height, and a second internal staircase, always in wood, to go down in the courtyard and to access the keep and the bastion. Now that the outdated hypothesis of a defensive redascio to withstand the equally implausible blows of rams of siege from external invaders has vanished, the redascio is attributed to structural problems of the foundation ground, particularly in the zone of entrance that was sacrificed at the time.

25

3.1.3.COMPLEX NURAGHI

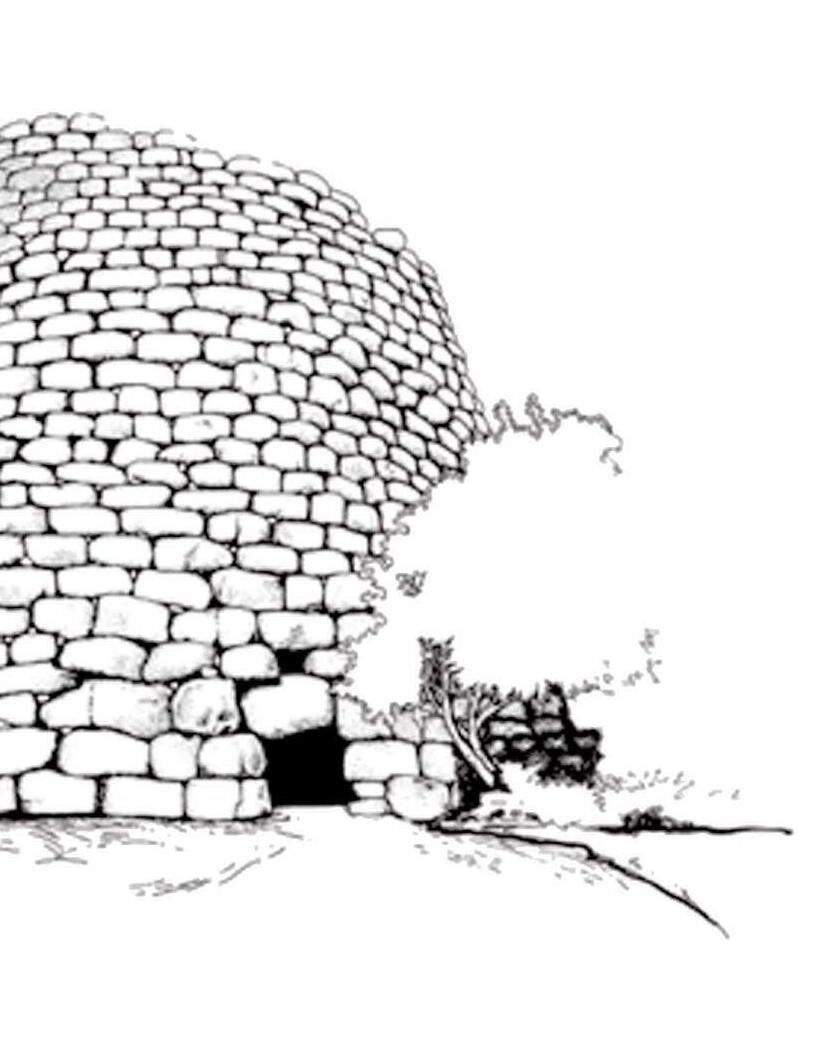

5-Nuraghe

26

Nuracale-Scano Montiferro, seen from above

Source: Paolo Melis, p 46, La Sardegna nuragica

6-Plans of complex nuraghi

Source: Paolo Melis, p 39, La Sardegna nuragica

1. Giba ’e Skorka-Barisardo.

2. Su Nuraxi di Sisini-Senorbì.

3. Su Còvunu-Gesico.

4. Su Sensu-Turri.

5. Monte s’Orku Tuèri-Perdasdefogu.

6. Su Sensu di Pompu-Simala.

7. Nàrgius-Bonarcado.

8. Palmavera-Alghero.

9. Frida-Illorai.

10. Sa Mura ’e Mazzala-Scano Montiferro.

11. Attentu-Ploaghe.

12. Nuracce Deu-Gèsturi.

13. Su Konkali-Tertenia.

14. Mudegu-Mògoro.

15. Santa Sofia-Gùspini.

16. Noddùle-Nuoro.

27

3.1.4.THE TOMBS OF GIANTS

The tomb of the giants is a group burial that is typical of the Nuragic people, but having a typology that is mostly different from that of the Nuraghi. The dolmen descends directly from the “allée couverte,” a community funeral passage with a trilithic design that was typical in Western Europe throughout the Neolithic and Eneolithic eras and is the result of a millennia-old prehistoric ritual. Several Gallura allées in Sardinia that had been in use since the old Bronze Age were renovated at the beginning of the middle Bronze Age by widening the burial corridor and including the high façade. The canonical design of the tomb of the giants, which is consistently replicated with very few variations, consists of a rectangular burial chamber whose entrance, a small hatch, opens onto an approximately semicircular space delimited by a massive façade known as the exedra, which houses a counter-seat at its base. “Above the chamber there could be a mound (i.e. an accumulation) of earth and stones, as well as in the dolmens, still partially preserved at some of the oldest monuments of Gallura” (Pascaredda-Calangianus and Moru-Palau) and “reconstructable in others such as Vittore-Ittiri” (Demartis G.M. 1992; Antona A. et alii 2011, pp. 246-248). “Similar features can be seen in a number of hypogean tombs with architectural plans, including relief mounds that are almost totally or entirely cut into the rock (Sa Figu IV-Ittiri) but nevertheless largely resemble dolmens” (Melis P. 2014a; 2014b). “The largest tomb of giants, which measures 28 meters and is located in Su Monte de s’Ape-Olbia, has an average total length of about 15 meters. The façade’s height can reach more than 4.50 meters. Over the next fifteen years the results of new censuses of the territory, discoveries and excavations are added that lead to the calculation of about 800 tombs” (Bagell a S. 2007). A cluster of two or more enormous tombs, which are usually located near settlements with nuraghe and villages, is not rare to observe. The tombs have deteriorated significantly over time, with 50% of the monuments having structures that cannot be identified due to inadequate conservation efforts or gaps in the availabale data.

28

29

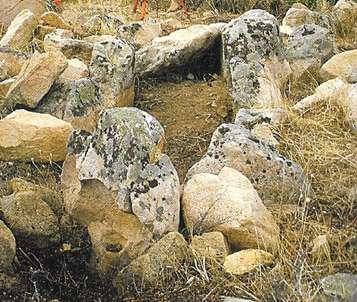

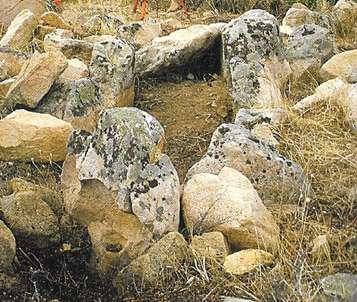

8-Giant Tomb of Iloi-Sedilo seen from above Source: Stefania Bagella, p 284, La sardegna Nuragica

7-Giant Tomb Taulaxia I in Sinnai Source: SardegnaArcheologica.it, Manun

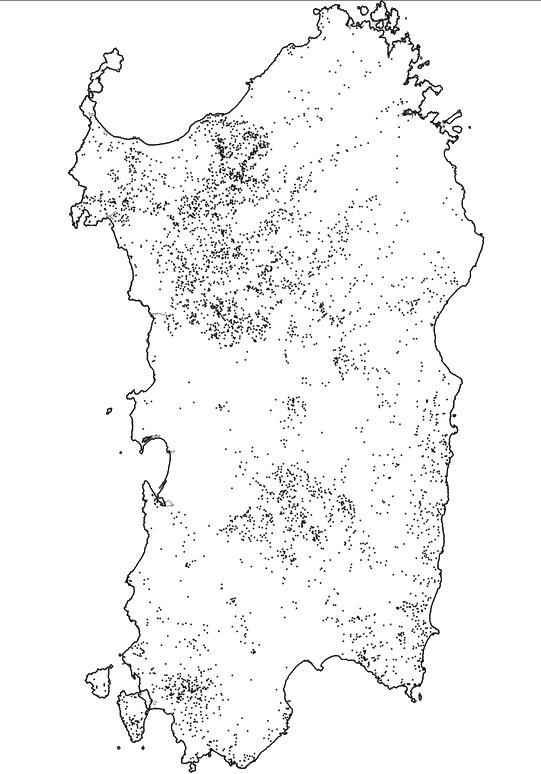

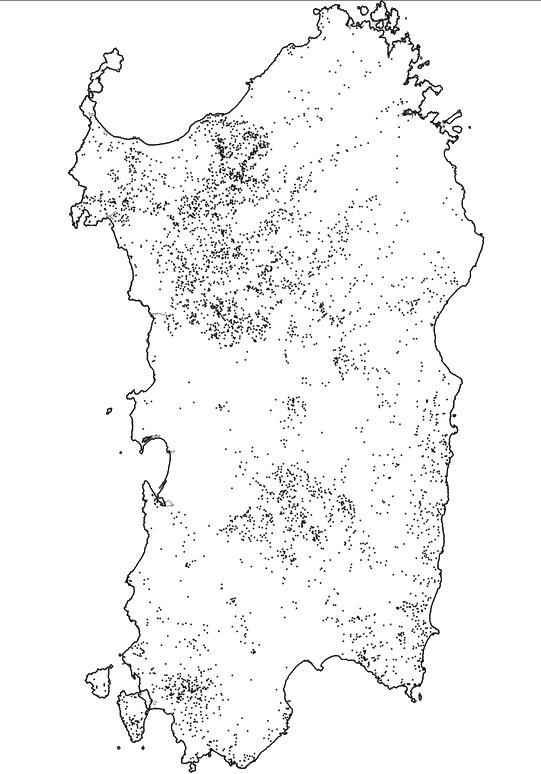

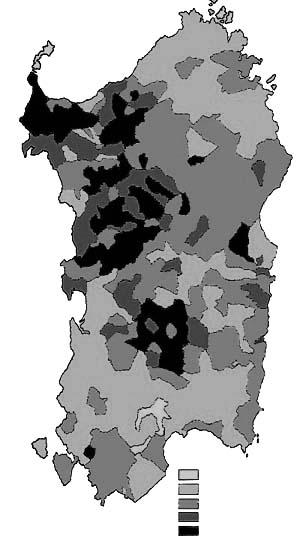

3.1.5.THE SPREAD OF THE NURAGHI

The nuraghi are found across Sardinia, with concentrations in some areas, particularly on the islands of Sant’Antioco and San Pietro. They are only found in the highest reliefs of the Gennargentu massif, in the Cagliari hinterland, and in a few other zones, as well as in all other small islands, with the exception, somewhat alarmingly, of the small and also very distant from the coast of the islet of Mal di Ventre, where a nuraghe has been reported. When it comes to the diffusion and number of nuraghi, it is important to note that it is not always simple to identify the nuraghi from the protonuraghi based on the sources and the state of the ruins. Studies on the number of existing nuraghi have never been conclusive, owing to the fact that many of them have had to vanish. Gathering the data available today - which includes information obtained in the first place from Antonio Taramelli’s archaeological maps, the catalog of degree theses initiated by the Universities of Cagliari and Sassari, and census work promoted by the two Archaeological Superintendencies of Sardinia and by various local authorities, in the second place, on the available webGIS (portals Tharros. info edited by Timber Krie and Wikimapia) - a provisional database has been created with 6523 records that correspond to the number of nuraghi for which we have real data on the location, with minor deviations due to the non-declaration of some monuments. Only ten communes in Sardinia have no nuraghe (Belv, Bugerru, Cagliari, Elmas, La Maddalena, Monserrato, Musei, Selargius, Simaxis, and Arborea, on which the judgment on the unverified news of a disappeared nuraghe is based), 25 have only one nuraghe, and 96 have no more than five nuraghes in their archaeological patrimony. The municipalities with the highest concentration of nuraghi, with over 100 monuments, are those of Sassari (158 nuraghi), followed by Ozieri (126), Chiaramonti (124), Macomer (109), Paulilatino, and Alghero (103 each). Seventeen other communes have between 50 and 100 nuraghi, with Nulvi (88) and Cabras (80) being the most numerous (80). The density per square kilometer, which takes into account the size of the territory in question, is more important. They can be found in plains, mountains, and along the coast. The data analysis also confirms the strong relationship between the nuraghi and the availability of water resources, which has been observed in various earlier studies based on river proximity. Nuraghi are concentrated in the smallest distance

30

bands: there are 1180 sites (18.08 percent) less than 100 meters from a watercourse, while the greatest concentration is between 100 and 200 meters (1692: 25.94 percent). There is always a strong presence of nuraghi between 200 and 300 meters (1221: 18,72 percent), while between 300 and 400 meters the decline is clear (809: 12. 40 percent) and marks the start of a fast and progressive collapse of the values inversely proportional to the growth of the distance: beyond the kilometer, there are negligible percentages, and it is also necessary to mention that there are many nuraghi of the High Sinis - of Cabras in particular - that are born near inland bodies of water (above all ponds), that could well satisfy the needs of water instead of real water courses. The distribution of nuraghi sites according to lithology reveals a significant preference for basaltic formations of the pliopleistocene volcanic complex, with 1326 monuments equating to a density of 0.87 per square kilometer. We used the pedological map of Aru (Aru A. et alii 1991) for the distribution of the nuraghi with the agricultural susceptibility of the land because it meets more of the needs of the subsistence analysis than the very recent map of the use of the land of Sardinia in the framework of the European project CORINE-Land Cover. The highest concentrations of nuraghi are found in pedological units with relatively poor or very poor main soils, which are not suitable for modern agricultural use according to FAO and USDA criteria, but which, if we refer to a subsistence economy like the prehistoric and protohistoric one, could possibly be cultivated in a very limited way, especially in the few flaps characterized by the presence of secondary soils that, in any case, didn’t g (soils with very strict limitations). However, the primary usage was for grazing, followed by livestock, particularly sheep. Other minor variances have been found at a more local level, but always in the context of a common constructive tradition, implying that the Nuraghic society had to show components of fragmentation, even if it is difficult to express it in cultural and especially political terms.

31

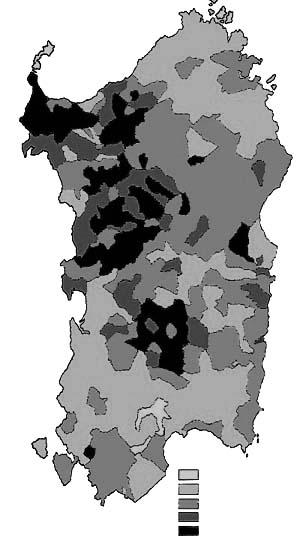

9-Distribution of nuraghi in Sardinia (adapted from Valera and Valera 2006)

_ 0 _ < 0.1 _ 0.1 - 0.35 _ 0.35 - 0.6 _ > 0.6

10-Nurografic map of Sardegna Medium density of the nuraghi in km2 (source: Lilliu 2003; p. 563 elaborata da T Kriek)

32

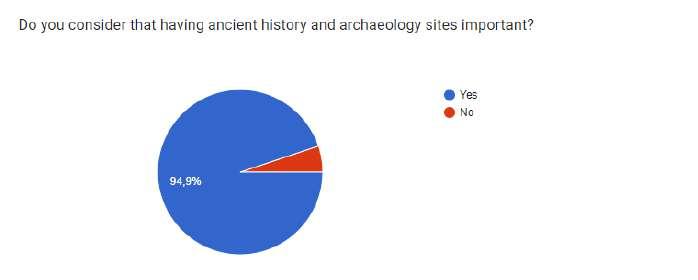

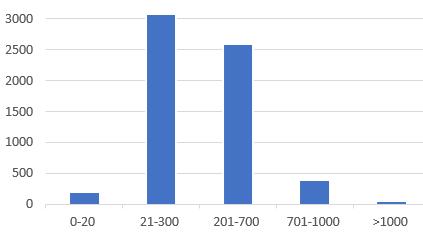

3.2.STATISTICS ABOUT THE NURAGHI

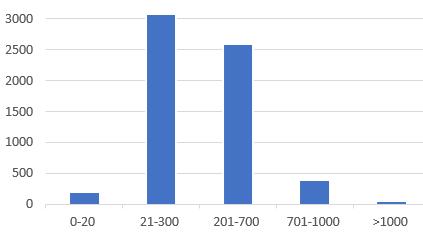

3.2.1.DISTRIBUTION

OF THE NURAGHI BY ALTITUDE

Altitude in meters Nuraghi %

0-20 208 3.3 21-300 3074 48.6 201-700 2588 40.9 701-1000 389 6.2 >1000 62 10

The graphics and table show the distribution by category of altitude above sea level. From 0 to 300 meters it is considered plain, from 300 to 700 meters hills and above 700 meters mountains.

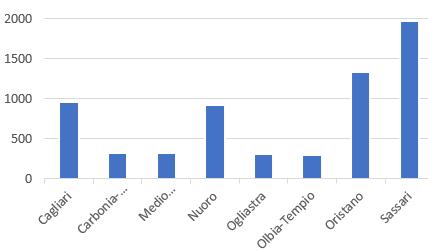

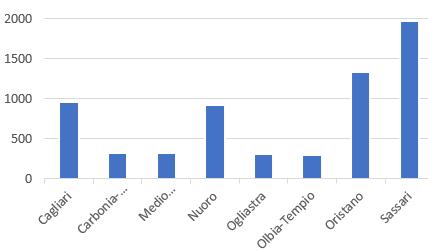

3.2.2.DISTRIBUTION OF THE NURAGHI BY PROVINCE

Province Nuraghi % Cagliari 961 15.2 Carbonia-Iglesias 319 5.0 Medio Campidano 317 5.0 Nuoro 926 14.6 Ogliastra 307 4.9 Olbia-Tempio 292 4.6 Oristano 1332 21.1 Sassari 1967 29.5

The graphics and the table show the distribution by province. The second most presence of nuraghi in Cagliari.

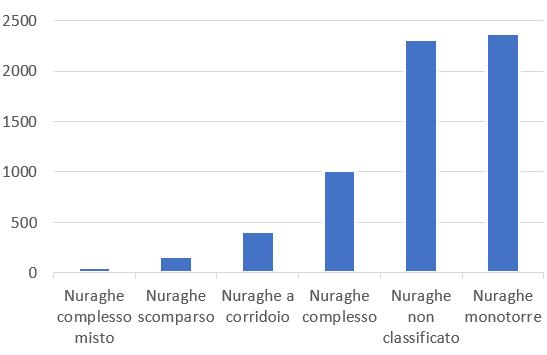

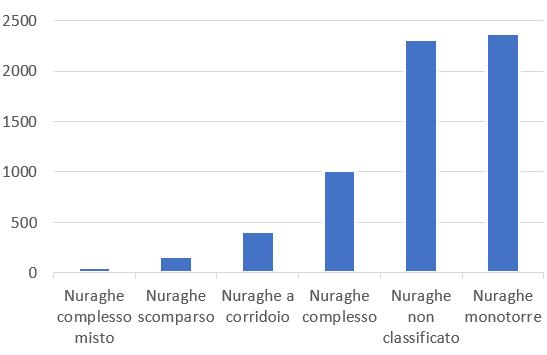

3.2.3.DISTRIBUTION

OF THE NURAGHI BY TYPE

Type Nuraghi %

Nuraghe complesso misto 51 0.8

Nuraghe scomparso 160 2.5

Nuraghe a corridoio 407 6.4

Nuraghe complesso 1015 16.1

Nuraghe non classificato 2313 36.6 Nuraghe monotorre 2375 37.6

The graphics and table show the distribution by type, and shows that the simple nuraghi (monotorre) is more present.

Source: sardegnarcheologica.it

by T Kriek

33

4.CONCLUSION

The Italian constitution provides important legislative texts to provide protection to its archeological heritage. They also regulate the steps for their inhancement and valorizzation, although the day to day of our present is making harder for us to be as involved in this process. Inroducing the walking tourism is a way of explorig new urban solutions to include these cultural goods and bring them closer and getting them to be easier to visit. As important as it is in our days, we should at the same time be careful about the environment and use sustainable solutions for such studies. The archeological goods present in the island of sardegne, as important as they are, represent a variaty of different types of buildings, dating of different times from the bronze era, for which researches are still trying to understand their function to the ancient society. I also studied their sitribution all over the Island, the altitudes of the lands they were built on, and the most discovered and present type until these days. This is foremost a theoretical study for the elements that are most important to the idea of the project to come.

34

Part II

5.LOCAL HERITAGE: THE CONTEXT OF SINNAI

5.1.GENERAL

SITUATION

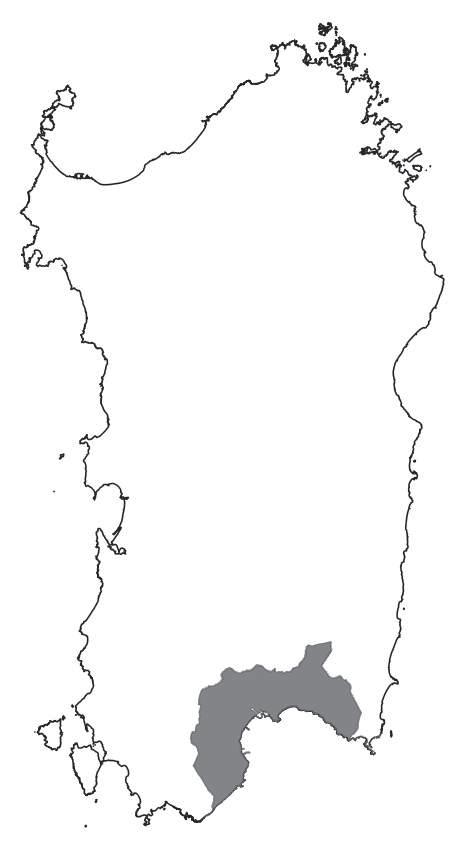

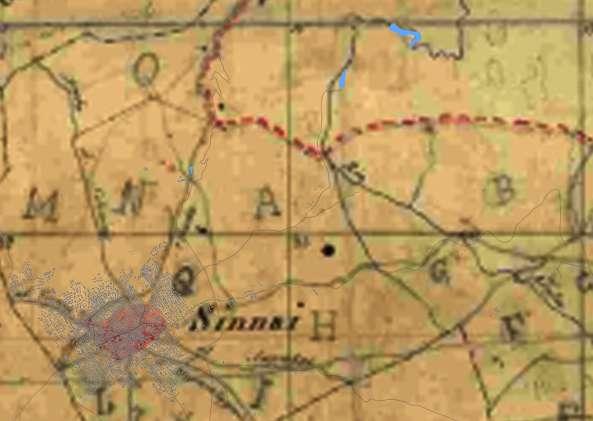

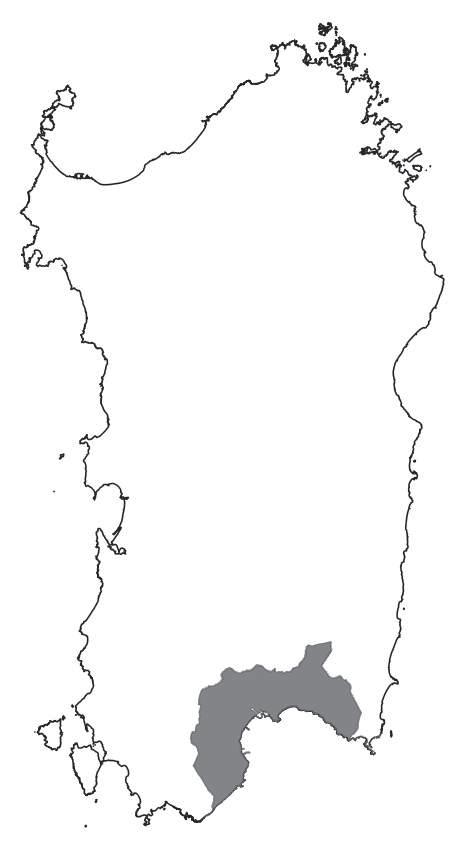

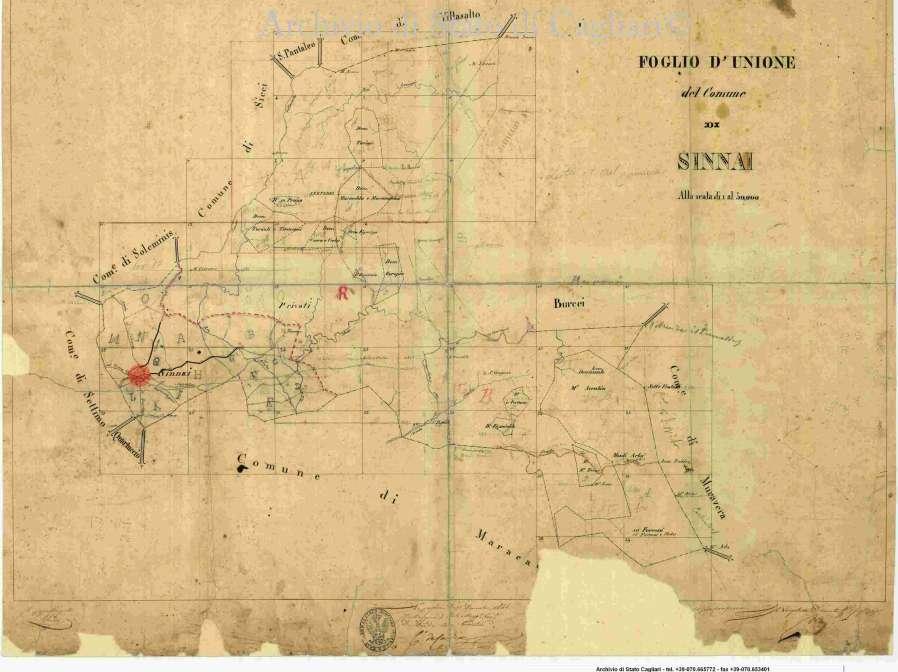

Sardinia Region map

The Image abouve represents the metropolitan city of Cagliari (CA) in south of the island with the limits of the municipalities. The darker frame represents the limits of Sinnai which is composed of two separate lands one is Sinnai and the other is Solanas.

Geographical data Altitude: 134 m a.s.l. minimum: 0 maximum: 1,067

Geographic coordinates in decimal system 39,3053° N 9,2045° E Area 223.91 km²

Source Official website of the municipality of Sinnai

36

5.2.THE CUTURAL ASPECT OF SINNAI

The Municipality of Sinnai is one of the largest municipalities of Sardinia. The city, which has about 17 thousand inhabitants, still preserves characteristics and typical traditions of the agro-pastoral culture.

Sinnai is a tourist destination of considerable interest in many aspects:

Artistic craftsmanship. Sinnai is famous for its baskets “su strexu ‘e fenu” unique in their kind for the quality and materials used such as rush and hay true artistic objects that still represent a secular tradition present in different families and an economic resource for some of them.

The village’s past is reflected in the pavement of the historic district, which is home to several typical Campidano homes, the parish church of Santa Piazza Chiesa, where Barbara is situated, and the Civic Museum of Archaeology, which also houses the Pinacoteca, which showcases figurative artwork, is located in the surrounds full of medieval and Nuragic artifacts.

The gastronomic tradition that makes it possible to enjoy Sardinian dishes in their original form in farms and restaurants.

the visitor can participate in cultural and recreational activities across the broad municipal territory by visiting exhibitions and seeing a variety of performances. In Sinnai, the Civic Theater, which opened its doors in 2004, produces the annual theater season in collaboration with L’Effimero Meraviglioso and features a schedule of performances that seeks to appeal to a wide range of preferences in theater, from classical to modern, from musical to dance.

Sports activities: Throughout the year, visitors to Sinnai can engage in sports and mountain and maritime trekking activities in the town and nearby hamlets, particularly at Solanas and Torre delle Stelle. A few trained and approved locals have organized themselves to guide visitors as they explore the fantastical world that awaits them at the city’s gates. You can book food and wine tours, artistic crafts, offroad adventures, dinghy, sailboat, quad, and foot tours. The countless festivals and folk festivals are genuine

37

Su Strexu ‘e Fenu

Fire tower from the 1st world war Sea diving in Torre di stelle

The civic theatre

times in city life where Sinnai’s best folkloristic and ethnomusicological expressions can be found. Events of popular interest involving international sporting competitions, choral performances, and entertainment festivals are included to these.

The most significant religious celebrations are those honoring Santa Barbara, the village’s patron saint, which are held on the second or third Sunday in July, the feasts of Saints Cosmas and Damian, which are held on the third Sunday in September, and Saint Helena, which are held in the last week of August. These celebrations, along with those for Santa Vittoria, St. Bartholomew, and St. Isidore, preserve the essence of the country rite.

There are three Catholic parishes located within the boundaries of the municipal area. One is in the Solanas city center, and it also provides pastoral services to the surrounding communities of Torre delle Stelle and Geremeas. The medieval parishes of Santa Barbara and Sant’Isidoro are the other two in Sinnai’s urban core. There are no established religious groups other than Jehovah’s Witnesses in Sinnai, though there is a small Islamic population made up of North African residents who are well-integrated into society. The charitable work of the religious organization “Misericordia di Sinnai,” carried out with the dedication of Catholic volunteers, is likewise of significant significance for the service provided to the community. The oldest social gatherings date back to religious festivals and carnivals, which were timed to the rhythms of agricultural work throughout the year.

In the historic rural churches strewn across the broad territory of the municipality, the cult of the saints, and in particular of those of the Greek-Byzantine tradition, has been preserved to the present day and is translated into enjoyable moments of communal celebration each year.

38

Is Cerbus the traditional carnaval of Sinnai

The Pro Loco and the municipal administration promote and help implement the cultural programs, which are created throughout the year with the help of regional organisations. The traditional Sinnaese Carnival, reviews of summer concerts and festivals in Sinnai and Solanas, the “Musical December” and “The pink color” in Sinnai, and the “La Fiera del Cestino” exhibitions of regional handicrafts are a few of the major events we can recall. To remember the New Year’s and Spring concerts of the Municipal Band Corps, the singing, dancing, and popular music events, the publication of a local periodical newspaper, and an established literary prize for Sardinian poetry are some of the most important cultural initiatives, in addition to the theatrical and dance season of Sinnai’s Civic Theater. The world championship of underwater photographs and the summer amateur and youth football tournaments are two of the most well-known athletic events supported by local groups, some of which are of an international scope. All the activities help to energize everyday life and enhance the community’s image.

The well-known St. Elena festival was canceled due to a lack of initiative. A permanent committee has been established to reorganize it for a while. While the feast of St. Elena falls on the Sunday following the Assumption, it is celebrated on August 18 according to the calendar of saints. To allow everyone in Sinnai the chance to participate who is away for the holidays in the middle of August, they started doing it on the last Sunday of August a few years ago.On this day, neighboring nations take part in the transportation of the enormous statue of the Saint from the parish church to her church in a lavish chariot drawn by festively decorated oxen. After the evening Mass on Sunday, a procession around the church takes place with the blessing of the fields. On Sunday morning, the solemn Mass is celebrated in the rural church with a panegyric of the Saint.The St. Helena statue The return procession, which begins on Monday evening after the Mass of Thanksgiving and includes a thought for the parish priest and the Eucharistic Blessing in the plaza, is accompanied by the singing of the Rosary in the local dialect. I choose to bring up this celebration in particular because the people of Sassari hold this saint in such high regard that they named one of the main highways leading to the highlands, the location of the majority of the Nuragic citadels, after her.

Source: sinnaionline.it/pages/ agostose.htm

39

The folk group of Sinnai wearing the traditional clothes

Statue of St. Elena

5.3.TRANSPORTATION AND ACCESSIBILITY

In order to visit Sinnai, it is better use private transportation, by using the SP15 provincial road going 14km and can take almost 25 minutes.

It is also accessible by public transortation as the bus, from the ARST bus station to the public square Saint Isidoro. This mean can tke up to 45 minutes to arrive to the destination.

The third mean to access The city is by taking three different means of transportation, first the bus M, then the metro of Cagliari, then the bus.

In the prospect of making a project in Sinnai, it should be more accessible. In the next map we notice the presence of train rails that only pass near the city of Settimo San Pietro, although there is no direct train that can go straight there. So the best ways would be either by bus or by a private car.

40

5.4.THE GEOGRAPHICAL AND MORFOLOGICAL ASPECT

5.4.1.LOCATION AND GEOGRAPHICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE TERRITORY

The Sinnai municipality covers a sizable portion of southern Sardinia between the Campidano di Cagliari’s eastern margin, Mount Genis to the north, and the Serpedd Massif and the Seven Brothers to the east. The Solanas hamlet, which encloses the coastal area between Torre delle Stelle and Cala Pisanu, just beyond Capo Boi, is a territorially independent property. The community grows primarily inland, along the new S.S. 125 road axis, up to the height of the M. Arbu and Su Niu des Crobus reliefs, the intersection of which forms the village’s northern boundary. With the exception of the sector where Sinnai is located, which insists on the Serpedd foothills, and the coastal strip of Solanas, this region is primarily characterized by steep and hilly reliefs. The Punta Serpedd (1067 meters), Serpeddieddu (1,017 meters), Bruncu Niu Crobu (1000 meters), M. Tronu (932 meters), Tratzalis (922 meters), and M. Genis (979) at the farthest north of the area are among the main reliefs. Punta Sa Ceraxa (1016 m), Bruncu Mitzargius (951 m), Bruncu Perdu Cossu (915 m), M. Eccas (918 m), and Mont’Arbu are all part of the Massif of the Seven Brothers (803).

5.4.2.GEOMORPHOLOGICAL TRAITS

The territory of Sinnai is mainly mountainous and very articulated with numerous river engravings sometimes very suggestive from a landscape point of view. Based on the geological characteristics, the modeling of the territory of Sinnai assumes peculiar characteristics that allow to differentiate two large areas: the northern sector, consisting mainly of metamorphic lithological series (schist); the centralsouthern sector dominated by late-Hercynian granites. The northern part includes the sectors of P.ta Serpeddì, Tuviois, Pala Manna, Tratzalis ne. The penepiano was subsequently modified by tectonic events related to the Alpine orogeny that produced a rejuvenation of the reliefs determining the beginning of a new erosive phase of the earth’s surface. This erosive action has continued to the point of exposing the granite intrusions by eliminating from their top most of the schist metamorphic cover. In this sector there is also the granite massif of M.Genis, which constitutes

Source: lsticuto di Geologia Ambientale e Geoingegneria del C.N.R.- Sede di Cagliari

42

a geomorphological typology with very peculiar characteristics. Its shapes in fact contrast decisively both for the type of morphology, and for its greater alitude compared to the surrounding metamorphic schist reliefs, due to the different geological nature that imposes itself in the landscape with its steep walls and irregular and jagged slopes. Granite lithologies also characterize the centralsouthern sector of the territory of Sinnai, which is also distinguished by the different modeling of its surfaces. One of the features More evident physical is the different structure of the hydrographic network that assumes a sub-angular morphology. In fact, the flow of water in this region is strongly conditioned by the geometric fracturing of granite. The intense contractions originated during the cooling of the batolite have in fact originated a small mesh of cracks that forces a development of the geometries of the hydrographic lattice strongly conditioned from these structural guidelines. The most evocative morphological aspects of this sector undoubtedly refer to the peaks of the Seven Brothers. whose rugged aligned ridges are visible from all over the Gulf of Angels. The slopes of this mountain massif have a rather marked acclivity, sometimes with rough and sub-vertical rock walls.

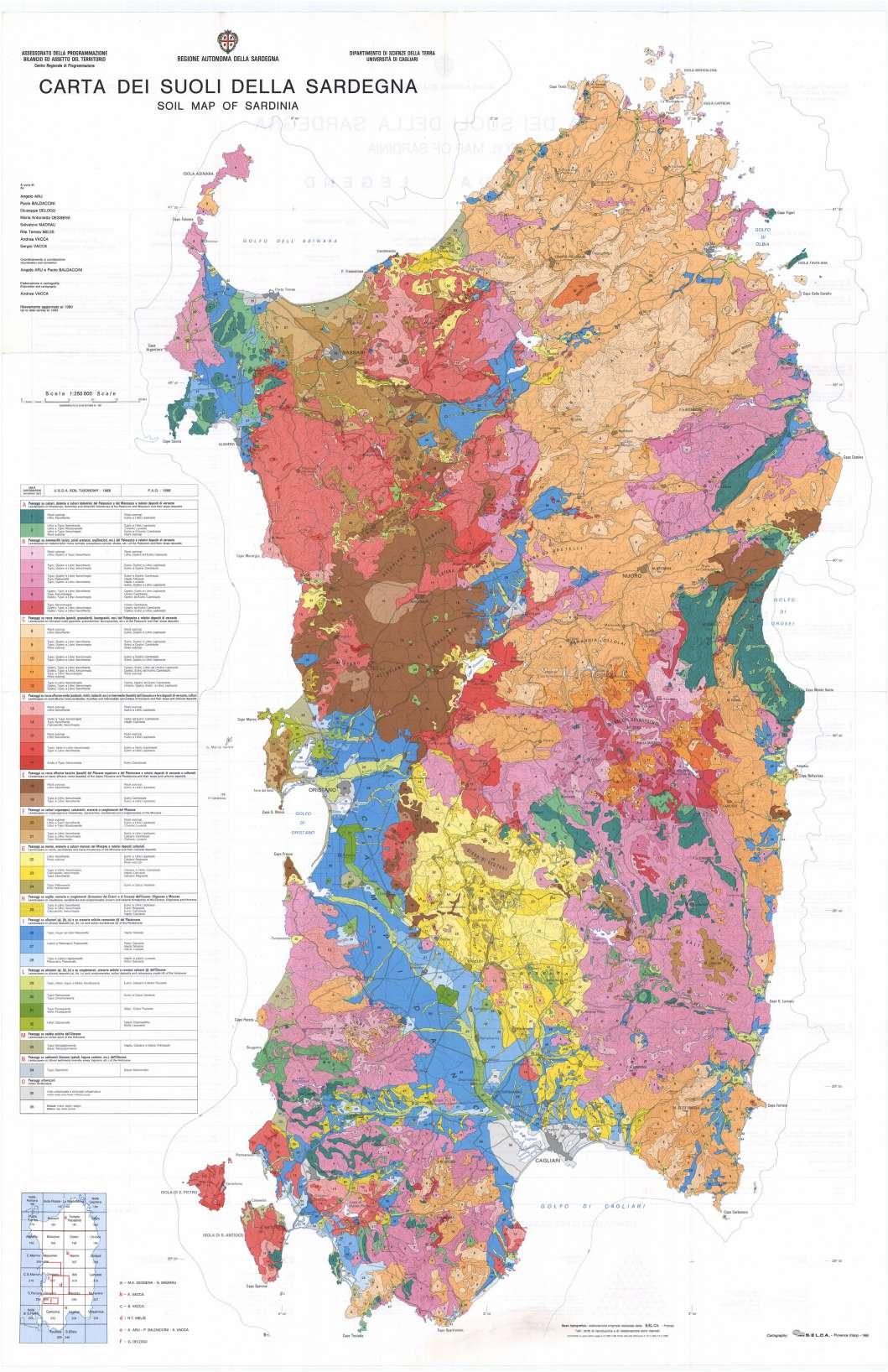

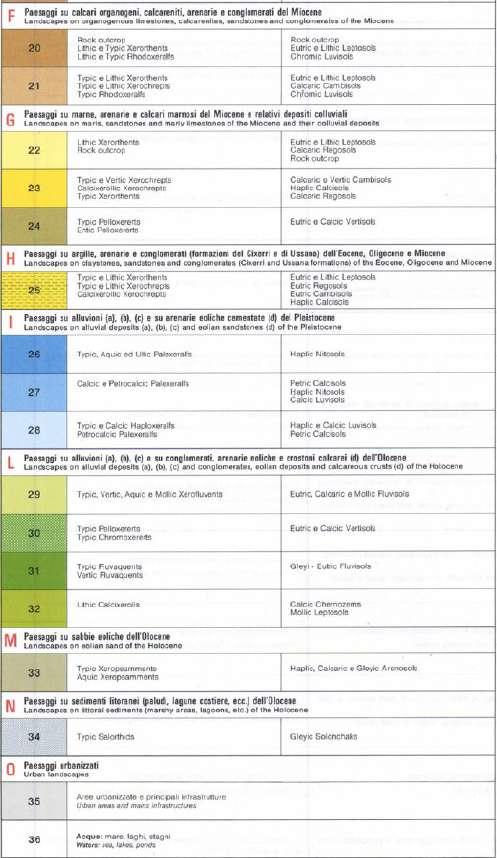

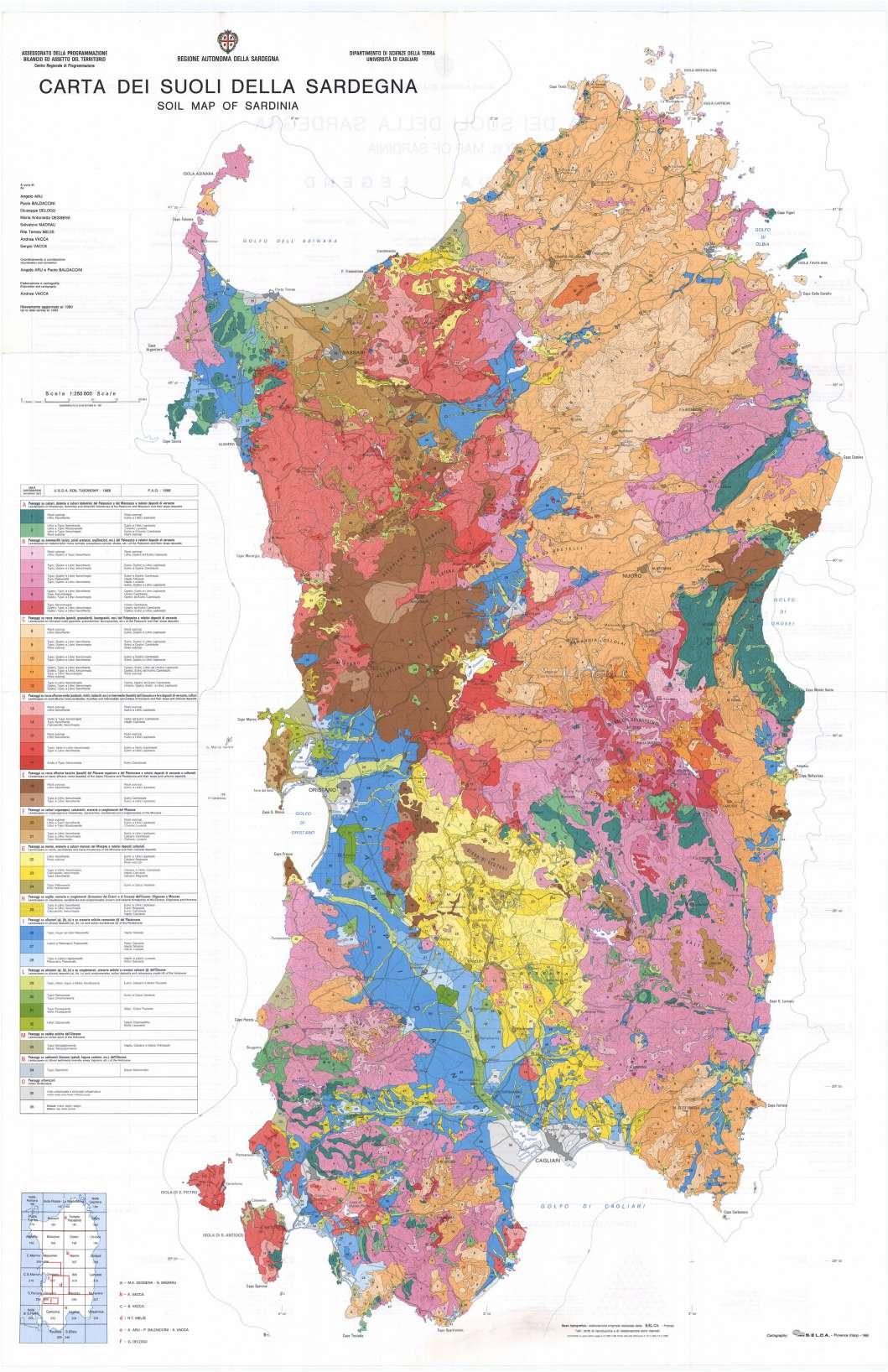

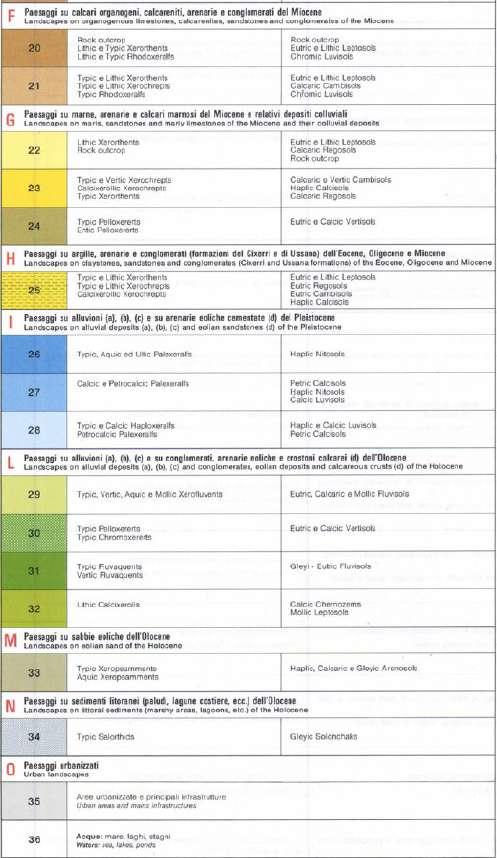

5.4.3.TAXONOMETRIC MAP OF THE LAND OF SARDINIA

With order to create the following map, huge Landscape Units regarding lithology and its shapes were used. According to the degree of evolution or deterioration, existing and future use, and the requirement for specialized interventions, each unit was divided into sub-units (cartographic units) composed of soil associations. Two classification schemes have been used: the FAO scheme and the Soil Taxonomy (Soil Survey Staff, 1988). (1989). The classification level reaches the Subgroup in the first instance. The substrate, the kind of soil and landscape, the primary pedogenetic processes, the classes of usable capacity, the most significant degradation phenomena, and future use are all specified for each pedological cartography unit.

Year: 1991

Authors: Aru A., Baldaccini P., Vacca A.

Source: Portale del suolo

Osservatorio Regionale Suoli della Sardegna

43

44

45

A hydrographic basin, drainage basin, and also called catchment area, or a watershed, area from which all precipitation flows to a single stream or set of streams. The boundary between drainage basins is a drainage divide: all the precipitation on opposite sides of a drainage divide will flow into different drainage basins. It offers a constrained surface area where physical processes relevant to general hydrology can be taken into account. The climatic variables and the water and sediment discharge, water storage, and evapotranspiration are important in the mounatains of Sinnai. It helped create a valubale terrain form that represents the begenning of a large mountain chain, and where there were created two water bodies. One of them is the historical pond called the “diga storica di Santu Barzolu”

46

5.4.5.HYDROGRAPHIC BASIN

5.5.THE HISTORICAL ASPECT

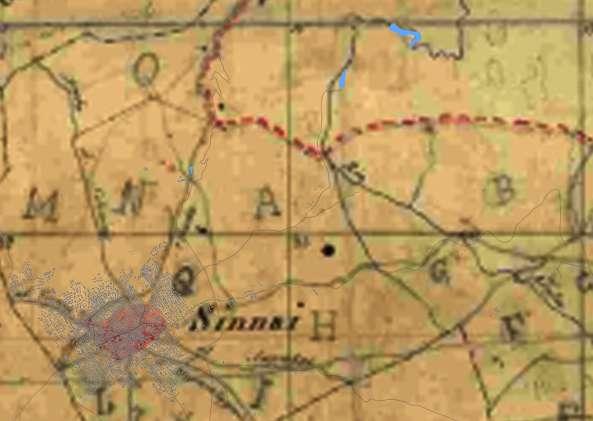

5.5.1.THE TERRITORY OF SINNAI: THE NURAGHI AND GIANTS TOMBS’ SPREAD

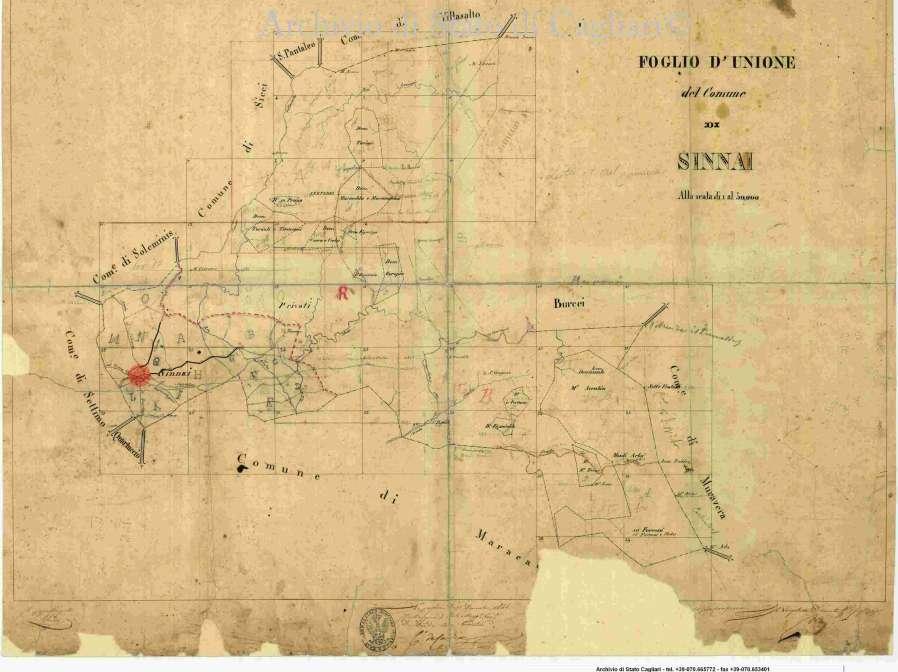

The necessity to protect the lands and the goods, including the pastures, the cultivated fields, the crops, the heads of cattle, and the communication channels that allowed them to trade their goods with those of others, led to the construction of nuraghi, fortresses, and guard runs. The majority of the nuraghi are found on rocky heights where they watch over the crops, pastures, and, most importantly, the communication pathways along the major waterways.

Archaeological censuses conducted in many island towns have revealed that single tower nuraghi and complex nuraghi constructed with multiple tholos runs can be found on the same piece of ground. The complicated nuraghi are always fewer than the monocorre and spread out in a manner that suggests that each has its own area. Based on the information we have, it may be concluded that the nuraghi initially just consisted of monotowers and that the complex tholos nuraghi were later constructed using the monotowers that already existed. Complex nuraghi appear to be the outcome of families competing with one another to achieve a social standing that is superior to the others.

The distribution of the nuraghi will be specifically examined in Sinnai on the following map, where we will find that they can be divided into six categories that will be illustrated in the legend of the map, distinguished by symbols, and a second time in a table where we associate the type to each nuraghe’s name.

47

5.5.2.TABLE OF THE DIFFERENT NURAGHI AND THEIR TYPES IN SINNAI

NAME TYPE

Antiogu Oi

Nuraghe complesso

Antoniola Nuraghe complesso

Arcu su Crabiolu Tomba di Giganti

Baccu Mereu Nuraghe monotorre Baiocca I Tomba di Giganti

Baiocca II Tomba di Giganti

Bruncu s’Allegau Nuraghe complesso

Bruncu Scala Suergiu Nuraghe non classificato

Bruncu Senzu Nuraghe monotorre

Bruncu su Castiu Nuraghe monotorre

Bruncu su Pisu Nuraghe monotorre

Cannaxeral Nuraghe monotorre

Cannaxera II Nuraghe monotorre

Cirronis II Nuraghe monotorre

Conca ‘e Idda Tomba di Giganti Conca Santinta Nuraghe monotorre

Correxerbu Nuraghe monotorre

Costa Fonai Nuraghe monotorre Cott’e Baccas Nuraghe monotorre

Crabili Serreli Nuraghe complesso

Cuccuru Gravellu Nuraghe complesso

Cuccuru Nuraxi Baiocca Nuraghe monotorre Cuccuru San Giorgio Nuraghe complesso

Cuili Sirigu Nuraghe monotorre dell’Isolotto Nuraghe monotorre Ferricci Tomba di Giganti Ferricci Nuraghe complesso

Funtana ‘e Landiri Nuraghe a corridoio

Funtana Landiri I Tomba di Giganti

Funtana Landiri II Tomba di Giganti Garapiu Nuraghe monotorre Genn’e Bentu Nuraghe monotorre Genna ‘e Mari Nuraghe monotorre

Giria Corona Nuraghe non classificato

Is Arredellus Nuraghe monotorre

is Berrittas Nuraghe monotorre

Is Cortis A Fonti e pozzi

Is Cortis B Fonti e pozzi Lepuri Nuraghe a corridoio

49

Longu Nuraghe a corridoio

Lorenzu Origa Nuraghe monotorre Maletta I Nuraghe monotorre Maletta II Nuraghe monotorre

Masoni Porcus Nuraghe monotorre Maxia Nuraghe complesso Mitza Crubetta Fonti e pozzi Mont’Arbu Nuraghe complesso Monti Eccas I Nuraghe monotorre Monti Eccas II Nuraghe non classificato Monti Saius Nuraghe monotorre Mustatzu Nuraghe non classificato Nuraxeddu Nuraghe monotorre Nuraxeddu Nuraghe monotorre Pireddu Nuraghe monotorre Pirreu Nuraghe a corridoio s’Arcu s’Arcedda Nuraghe non classificato s’Arrideli Nuraghe monotorre sa Castangia Nuraghe complesso sa Fraigada Nuraghe monotorre sa Guardia di Ferricci Nuraghe monotorre sa Perdera Nuraghe complesso sa Rocca Arrubia Tomba di Giganti sa Tuppa is Procaxius Nuraghe non classificato San Gregorio Nuraghe monotorre Sant’ltroxia Nuraghe monotorre Sant’ltroxia Tomba di Giganti Santu Basileddu Fonti e pozzi Serraidda Nuraghe monotorre su Crabiolu Nuraghe monotorre su Crastadroxiu Nuraghe monotorre su Fromigosu Nuraghe complesso su Gallesu Nuraghe complesso su Rei Tomba di Giganti su Rei II Tomba di Giganti su Zinnibiri Tomba di Giganti

Taulaxial I Tomba di Giganti

Taulaxial II Tomba di Giganti

Taulaxial III Tomba di Giganti

Zinnibireddu Nuraghe complesso Zinnibireddu l Tomba di Giganti Zinnibireddu Il Tomba di Giganti

Zurreddu Nuraghe monotorre

50

6.CONCLUTION

In this part, I analized the different aspects of the local heritage context, the city of Sinnai and its mountains. There are mentions for its cultural context with the local gastronomy and festivals, also its geografical situation next to the start of a chain of mountains which gives it two different types of terrains, one plane and the other with high and disturbed morphology. I should also mention that Sinnai is composed of two different lands apart from each other, the other is solanas, situated on the medeterranian sea. I elaborated a general situation map that shows the accessibility to the city, using a private mean of transportation and also the public ones. The other maps show the hydrografical basin and the spread of the nuraghi in the mountains while sheding the lignt on their vicinity to the water courses while identifiying their different types and their names. This part is the second step after the theoretical study in the first part, that would allow a better explaining for the area of study after analysing these different aspcts.

51

Part III

7.REGIONAL LAWS FOR THE PROTECTION OF ARCHEOLOGICAL FINDS

7.1.ENHANCEMENT OF THE AREAS CHARACTERIZED BY HISTORICAL SETTLEMENTS

The dynamics of the island settlement show a trend toward a gradual weakening of internal areas in favor of major urban centers and coastal areas: The historical process of countries and territory abandonment has an impact on the entire region’s ecosystem, landscape, and socioeconomic conditions. The recovery and social, cultural, and economic revitalization of historic centers, the enhancement of historic rural settlements, the redevelopment of landscape values in degraded areas, and the revitalization of smaller centers, individually or collectively, are all addressed through the creation of strategic synergies within the complex regional system. Together with additional measures , The DOMOS and BIDDAS Calls have been activated to support the enhancement of the residential character of the island’s historic centers and encourage the restoration of their economic and social vitality. Both were born as a result of L. R. 13 October 1998, n. 29’s provisions. “Protection and enhancement of the historic centers of Sardinia”and the provisions of the Regional Landscape Plan.The two calls ask for donations to be made in order to carry out initiatives that can greatly improve the historical building heritage. The small and extremely small municipalities in Sardinia are taken into consideration in the regional planning because they are unique in their own ways: Due to the lack of or difficulty in using primary access infrastructures, these tiny rural municipalities, mountain communities, and ancient villages with significant landscape value and a strong historical-cultural identity, but they are nonetheless marginalized in relation to the system of material infrastructures and intangible infrastructures (insufficiency of services). These communities, which make up a distinctive hinterland, struggle to manage their local resources and services, and they are also experiencing population decline, which worsens the condition of vacant buildings and public areas. The CIVIS Call has been activated within the European resources with the goal of enhancing the services and quality of the urban system of the networks of small towns in Sardinia. The primary goal of the CIVIS Call was

53

to offer residents of small urban centers a greater variety and higher caliber of social, cultural, educational, touristic, and economic services in order to encourage the stability of populations in the inland areas of Sardinia, assisting in the fight against depopulation and the preservation of landscape values. In a key move, CIVIS shifted to collaboration networks in minor urban centers by advocating a network approach for municipalities.The network concept has shown to be an effective force for improving the territory in this situation, becoming more so as it has been successful in creating territorial networks of neighboring municipalities or theme networks, that is, mainly composed of urban centers, even those that are not adjacent, that have a common goal of development in terms of widespread acceptability and who intend to pursue it in a way that must necessarily take into account the rights and responsibilities of each component as well as their capacity for integration. In addition to the regeneration and restoration of the smaller towns’ population patterns, with a focus on their historical sites, the pursuit of quality and landscape congruence with the relevant context, a proper characterization of the landscape’s environmental context, The CIVIS Call has worked to integrate educational, cultural, and social services. It has also sought to maximize the availability of facilities and support for production activities, as well as to promote initiatives with broad appeal. To achieve these goals, it has supported recovery initiatives with high urban quality that aim to repurpose abandoned properties in historic districts.

7.2.PERIMETER OF PROTECTION

To protect the archeological goods, there are two different peremiters:

7.2.1.PERIMETER

WITH INTEGRAL PROTECTION

The total unbuildability is proven. With potential longterm monitoring of the deteriorating circumstances, the cautious repair of the remaining structures is permitted. The responsible bodies may always undertake study, research, excavation, and restoration operations, as well as transformation interventions relating to this activity. Public works of soil protection-related interventions are permitted, with the awareness that any incidental intervention on the subsurface has to be approved by the relevant Superintendence for Archaeological Heritage.

54

7.2.2.CONDITIONAL PROTECTION PERIMETER

The total unbuildability is proven. Studies, research, excavation, restoration, and similar transformational interventions by the responsible entities are always permitted. The property may be used for grazing, and interventions for public works of soil preservation, reclamation, and irrigation are permitted, with the awareness that any incident intervention on the subsoil requires approval from the relevant Superintendence for Archaeological Heritage. Additionally, it is permitted to build modest infrastructures (such as roads, rest areas, hedges, etc.) to enable public access to, use of, and enjoyment of the asset without impairing the landscape’s natural and environmental qualities. According to the principle of minimal intervention, lightweight infrastructures must be constructed from high-quality materials (wood, iron, natural, or local stones), with the exception of reinforced cement conglomerate for above-ground structures, and fastened to the ground with non-invasive anchorage.

7.2.3.RELATIONAL PERIMETER

As this study aims to include multiple Archeological goods within the urban fabric of the city of Sinnai, we can say that our perimeter would be bigger, and would incorporate all of them and their protection perimeters, as well as for the roads connecting them, starting from the city, from the square near the Sant’Isodoro church, towards the mountains through Via Emilia passing through the nuragic buildings, and the historical water pond of Santu Barzolu, and finally turning through the historical road Via Sant’Elena where the visitor can visit the old church for the Saint and go back towards the historical city center of Sinnai. Each one of these archeological sites has a great value, and each one of them represents a story and a national heritage. This project is about setting a bigger perimeter of protection that has also the role of including these protected areas in the city’s perspective. Thus, the path connecting them would make them more valubal and imposing.

There are multiple future additional plans for this project, form introducing a bike lane, to installing resting and food areas along the way. It would also be interesting greating close oraganizational centers ,since the society is very active, to give informational tours and teach the kids about the Sadinian history and how to conduct the excavations.

55

7.3.PROGRAMMATIC LINES OF THE MUNICIPALITY OF SINNAI

These are a few of the thematic axes that will be developed as key directives by the future administration of the Sinnai municipality. The following are two of the 28 recommendations that were recalled in regard to the priorities determined for the first term of administration because of their importance in terms of both substance and methodology and their connection to the goals of this thesis. * Interventions that will improve the cultural, historical, and archaeological heritage. Systematizing the existing available resources for their maximum utilization in this field is more critical and necessary than ever: Municipal Archaeological Museum, Pinacoteca, D’Aspro Collection, Museum Layout “Sala Filtri” by Santu Barzolu; future Ethnographic Museum and the interweaving of the TRAMAS project, sacred art heritage in the historic churches of Santa Barbara and Santa Vittoria, historical and archaeological emergencies widespread in the municipal territory already the subject of study and census. Planning in this area will need to take into account the necessity of consolidating and securing the Via Colletta premises as well as the prospects presented by modern communication technologies to expand the possibility of utilising the asset across the entire region. In order to support the proposed initiatives of excavation and improvement of the Nuragic fortress of Ferricci, it is intended to continue the emergence in the municipal grounds of Solanas of a visual “museum” devoted to the Nuragic civilization, which would provide visitors with a narration based on video images and audio descriptions of the primary structures and artifacts of the Nuragic civilization , with a focus on protonuraghe (corridor), nuraghe (tholos), tombs of giants, well temples, ceramics and bronze era artifacts. The narrative will make special mentions of the monuments found on the land of Sinnai - Solanas and its environs (Nuraghe Ferricci, Mitza Crubetta’s well temple, Sa Rocca Arrubia’s giants’ tomb), as well as the greatest examples in the local area (nuraghe Arrubiu and Barumini, temple to well of Santa Cristina, tomb of giants of Is Concias, etc.). The narration linked to the objects will include accurate recreations of the bronzes and perhaps of the Mont’e Prama “giants,” as well as meticulous reconstructions of the time’s weaponry, utensils, and clothes, with probable allusions to the customs presently in use. We intend

56