January 2023 MAGALOGUE 4

COVER IMAGE

The Temple of Life Alan Macdonald oil on linen | 162cm x 147cm +44 (0) 1463 783 230 art@kilmorackgallery.co.uk Kilmorack Gallery, inverness-shire iv4 7al SCOTLAND

2

Contents

The Rebirth of a Magalogue 5

Selected work 7

Universal Whispers 8

The timeless woodcuts of Paul Bloomer by Tony Davidson

Kami – in every tree 12 The world according to Pamela Tait by Tony Davidson Point of Departure 16

Pilgrim 18 Looking at a Painting by Georgina Coburn

Three Questions to Tony Davidson 22

One Train, Two Men and Three Trees 24 from the vaults 26

3

4

Magalogue 4

We have decided to bring the Magalogue back after a gap of over four years. There were just too many things to say about art and the role of Kilmorack Gallery’s stable of artists, and it is important to put things down on paper, so that they are caught and made real.

In Magalogue 4, we explore Paul Bloomer’s obsession with observing the natural world, we look at the things Pamela Tait’s discovers in trees and Georgina Coburn delves into Henry Fraser’s ‘Pilgrim.’

Tony Davidson Director of Kilmorack Gallery.

Oz | HENRY FRASER

| ROBERT POWELL

MCAULAY | Upright 4 acrylic on board | 30cm x 101cm

Whelped

ROBERT

before,Yesnaby | ALLAN MACDONALD

Last Light, Fife | CHRISTINE WOODSIDE

Disconnected | ROBERT MCAULAY

Galina iii | GERALD LAING

by Tony Davidson

Last Light, Fife | CHRISTINE WOODSIDE

Disconnected | ROBERT MCAULAY

Galina iii | GERALD LAING

by Tony Davidson

8

Whispers

Universal

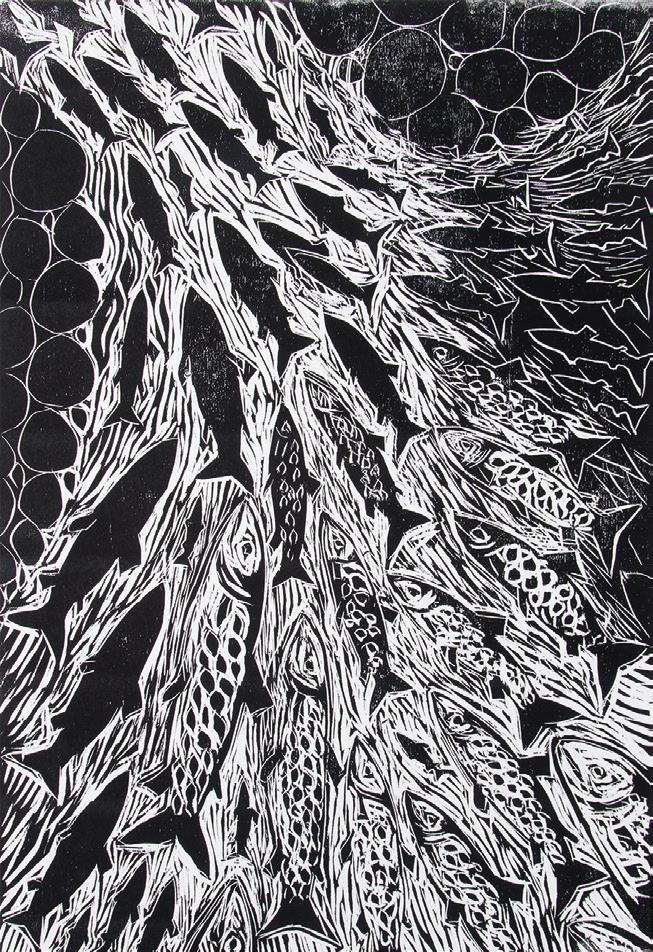

The timeless woodcuts of Paul Bloomer

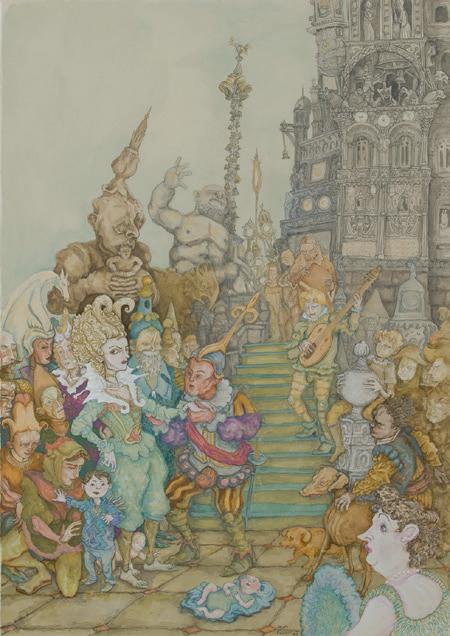

MoonTide, 2022 woodcut | 45cm x 30cm

The greatest privilege in running a rural art gallery and always living close to creatures is that I share my life with more than just artists and visitors to the gallery. There is a deer that swims across the river Beauly very early in the morning, and there are bats, squirrels, leaping fish, mice and yes, rats. This is even more true for Paul Bloomer who blew north to Shetland over twenty-five years ago. In Shetland we are outnumbered by birds and nature, even if sheep-nibbled, is part of a shared life. Bloomer’s routines are cyclic. In summer he explores wild places and observes the creatures that live there and those who pass through, and in winter he draws, prints and paints what he has discovered over the summer. These creations are story-paintings, the whisperings of wild-places.

Bloomer’s studio is in a converted barn that overlooks St Ninians’ Isle and a small corner of this cluttered space is given over to making Indian-style flutes. Legend has it, he tells me, that the first bansuri flute was made when ‘the wind whispered a song through a hole carved in a piece of bamboo by an insect.’ It was a song of connectivity when wind, insect and bamboo together allowed music to happen.This search for harmony and discovered truth is in all of Bloomer’s work.

These summer walks take him to islands of quiet, remnants of what must have existed everywhere not so long ago. Such places inspired the story-paintings that exist in most ancient cultures: in aboriginal art, Celtic stone-carvings and native American art.These experienced wonders are the original origin stories and are a reminder

9

of what lies below the veneer of modern life.

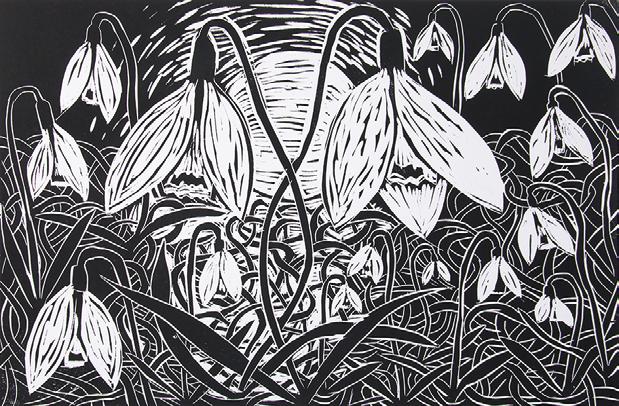

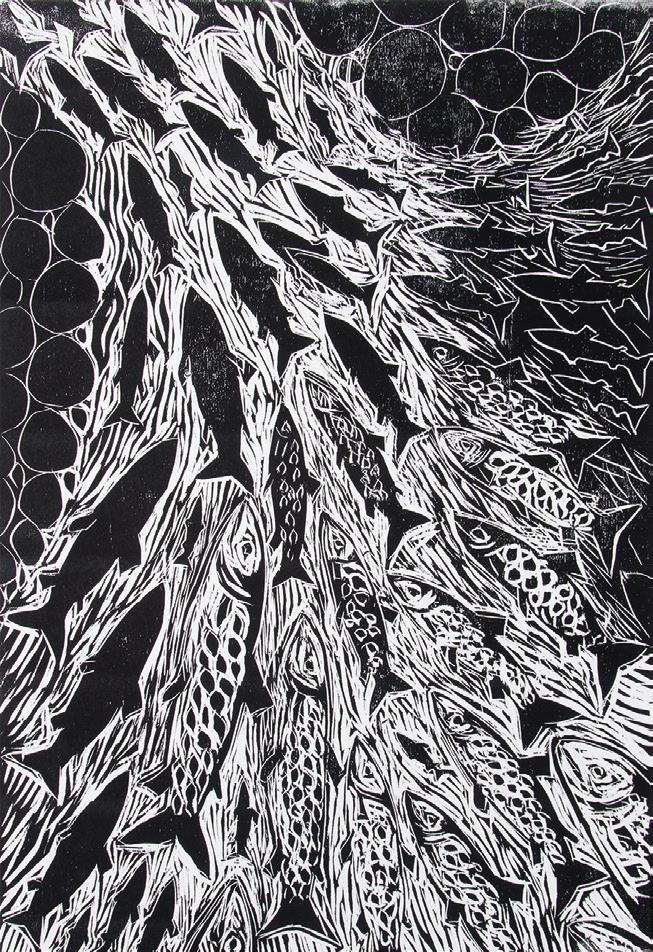

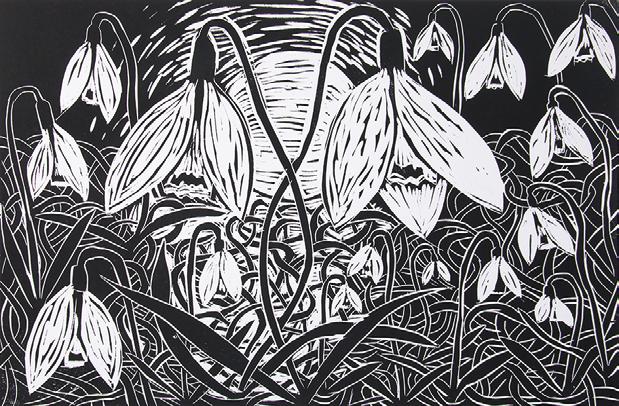

And these stories? The creatures don’t complain about bird flu, habitat loss and climate change. They are too busy in a universal dance. There are water songs where fish follow their upstream instinct, and whale songs, when these magnificent beasts exist in oceans that are now too noisy. Paul sees a lamb surrounded by ravens, and an owl and hare which share the same cool night air. These songs and rhythms are a continuity, where the wind in Shetland blows, and birds and other creatures circle endlessly around light and dark. Eventually, after winter, there are snowdrops.

There is also the suggestion that we too, are part of this song. The spiralling designs in Bloomer’s art speak of ancient ways and sometimes we feel this in art, with a half-remembered half-forgotten attraction. Like in every dance, we respond with instinct. Older things, truer things are there, Bloomer tells us, if only we would listen.

Snowdrops, 2022 woodcut | 30cm x 45cm

Whale Song, 2022 woodcut | 45cm x 30cm

10

11 7

Kami – in every tree

The world according to Pamela Tait

by Tony Davidson

by Tony Davidson

12

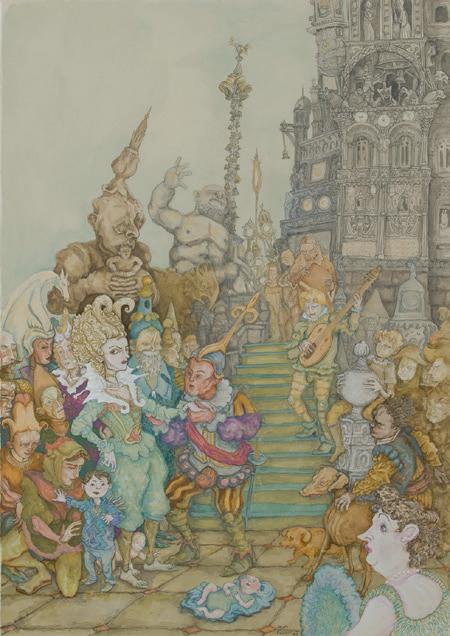

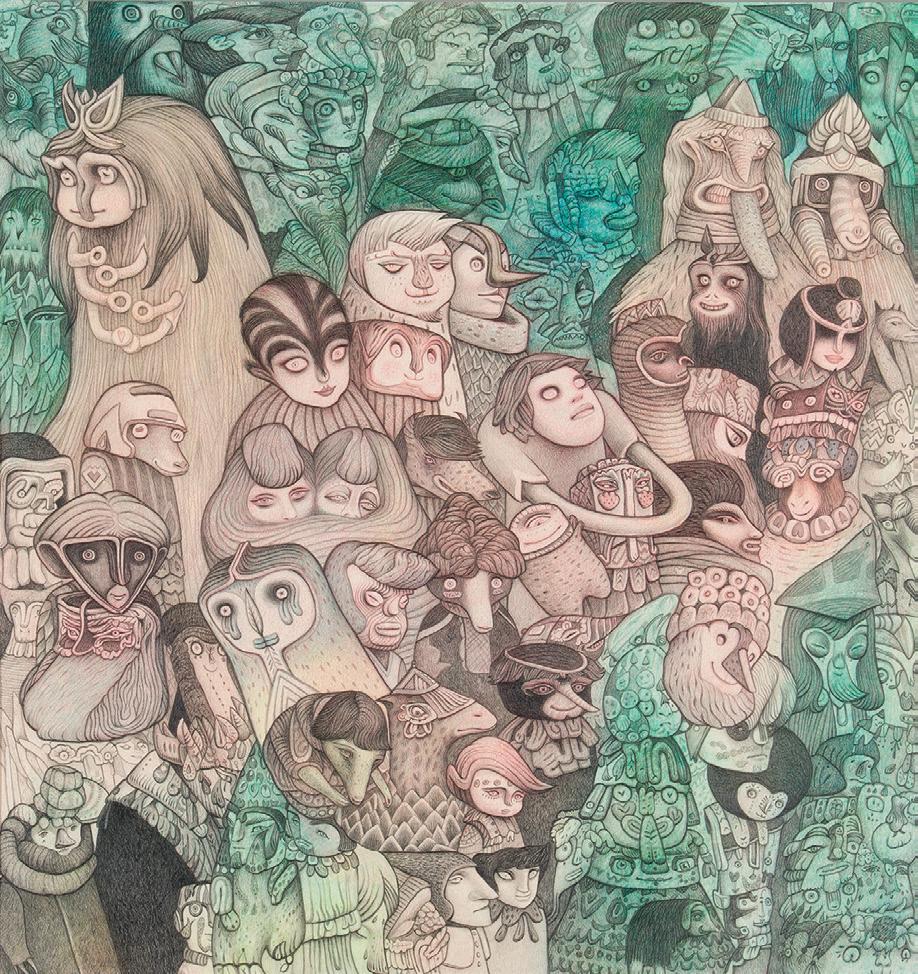

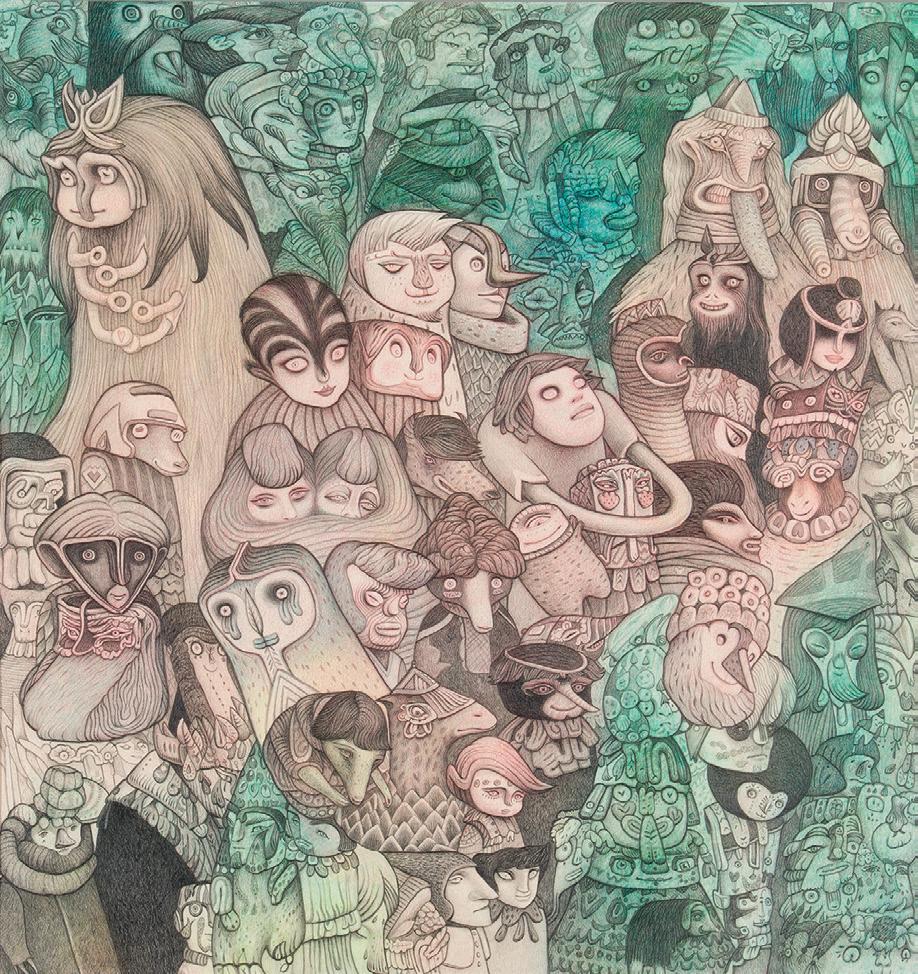

The Fairy Glen pencil on paper | 39cm x 35cm

Sometimes, what at first appears simple, has other layers folded into it. Two drawings with a hundred creatures in them now hang on the gallery’s wall. These are by Pamela Tait. In both drawings a myriad of shapes from a forest of trees have morphed into a procession of creatures. Some of these spirit beings are tall with totem-like heads and others are shorter, a hairy face poking out from a niche. A few are menacing while most are friendly. It is an echo of our world, and they remind me of Kami, the spirit gods seen in Miyazaki’s beautiful Studio Ghibli films. It is hard to clear this vision from my mind as later that day I walk the dog through an ancient wood that has almost vanished. I have the feeling that I am not alone here. There is an old spring above the gallery that feels like this too. In some places it feels that the spirits around me are more aware of my presence than I am of theirs, that I am being watched and weighed.

Fifteen years ago, I discovered a love of Japanese films, especially ones with Shinto elements, those that had nature guardians at their core. In many of these films there is a parade like in these two works: when Chihiro crosses the bridge in Spirited Away, the rotating kodama (tree spirits) in Princess Mononoke and even the unhinged parade in Paprika. When the parade is seen by the protagonist, a hidden world is revealed, and the film awakens to tell its story. The glimpsed parade gives awareness of this otherworld and the (im)balances in it. From this vision we gain some understanding of this parallel world, and are able to appease the gods by living like them. Hopefully

13 9

balance is eventually restored. But that is the world of Shinto-influence Japanese films. I walk on.

Pamela Tait tells me she’s not seen many Japanese films and has never heard of Kami, but I have seen little bits of Japanese influence in the studios of other artists: manga prints are not far from Alan Macdonald and Paul Barnes’s easels, Hokusai waves are in others and Basho’s haikus are often pinned discreetly where they can be read. Parades of spirit creatures, of course, aren’t restricted to Shinto. Fairies are not so different. Like kami, they can be either small or large, friendly or cruel, and are protective of the natural world. They are only sensed when silence has a sound. This is an artist’s secret tool: to be hyperaware, to be able to sit in the dark long enough to see again. Without this, there is less to paint about. An artist should see the straight lines that form a circle.

So, what do we know of kami? They are either foul or fair, so don’t cross them. They are invisible and inhabit sacred spaces: hills, rivers and trees. They move from one place to another – touring their realm. There are many types of kami and each one has a unique role, and finally, if we look after them, they’ll look after us. This is an ancient and somehow right-feeling way to live with nature, and one possibly overlooked by monotheism.

14

I walk the dog further and look at the vast hole where the forest once was. Burial cairns, hut circles and our archaeological past has vanished with the forest too. I decide to make a rotating kodama (tree spirit) sculpture to leave on my next visit. It is best not to offend the little folk and maybe, with an offering, they will return.

Sunny and ShadowyTrees graphite | 28cm x 39cm

15

Point of Departure

16

ALLAN MACDONALD |oil on canvas | 31cm x 61cm

17

Pilgrim Looking at a Painting

by Georgina Coburn

Pilgrim acrylic on board | 120cm x 120cm

18

Henry Fraser’s Pilgrim feels like a sublime summation of his practice. Acknowledgement of the human condition, and the vision which enables us to keep walking the road, however long or difficult, is always present in his work. Whenever I encounter one of his paintings, I am struck by simple truths and a myriad of emotions.

In Pilgrim (acrylic on board 120cm x 120cm), Fraser’s characteristic humour appears in the words ‘shant be long’ scratched into the top right-hand corner, a wry nod to the truth that the way is often serpentine. We can disappear down pathways or into paintings searching for a destination that is ever elusive or unseen. The vocation of a creative life is a calling that cannot be denied. That sense of honesty and authenticity permeates Fraser’s highly empathic work. The impasto scallop shell in the bottom right hints at the camaraderie of walking together, a measure of charity, kindness, and a scoop of sustenance on the road less travelled.

The artist’s palette is of earth and flesh, made luminous by his sensitive range of marks, scratched, stippled, and masterfully blended. The figure appears like an icon, bringing forth light from the soul of the viewer. The pale face shines through, invested with tiny accents of muted colour, drawing the viewer close. Recognition of the human face is hardwired deep within us, a well of expression often hidden, which the artist brings to light.

Fraser’s bold abstraction is tempered with immense subtlety. Tiny eyes are sharpened to points of light and a halo sweep of brushwork frames the head of a pilgrim,

19

held slightly to one side in thoughtful repose. Features are rendered with economy, a single brush mark of Alizarin coupled with grey shadow form a nose and the mouth is a soft, muted line of pink. The scale of the face feels cosmic, yet these small details are tender, bringing unexpected intimacy to bold abstraction.

Fraser creates a quiet space within the painting, held in the natural orbit of the face which moves in its essential humanity. The passage of time and light bring illumination.You don’t notice the gold at first.You need to move around and into the painting before that shimmer of awareness emerges, like hope. This quality pervades all Fraser’s art, together with strength and courage, to see where the painting leads.

Regardless of the raw or nuanced emotions that surface contemplating Fraser’s work, I always feel elevated and comforted by his vision of humanity. How miraculous, in a world filled with such destruction and uncertainty. As my eyes connect with the those of the Pilgrim, I incline my head, transfixed and altered by the experience. Fraser’s head and shoulder figures are often alone, but the act of seeing between artist, subject, and viewer completes a circle and we stand alone no more. The Pilgrim’s eye meets ours, the other looking into the wide beyond.

20

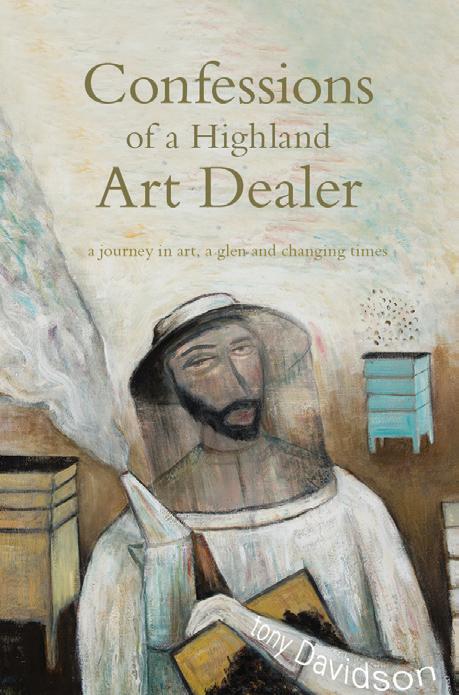

Highland Book Prize 2022 Longlist

‘An unexpected page-turner’

‘Surreal and magical, painting in a jewel of colours a lost world of eccentrics and artistic endeavour’’

‘It’s just bloody good’

‘A great read. Couldn’t put it down and finished it too quickly. Waiting for the next book now. Buy it.’

21

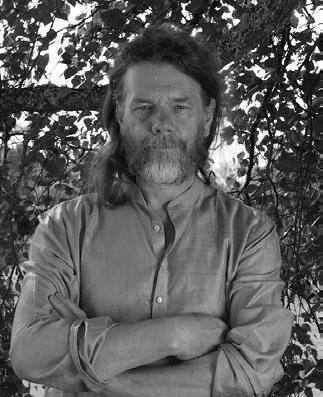

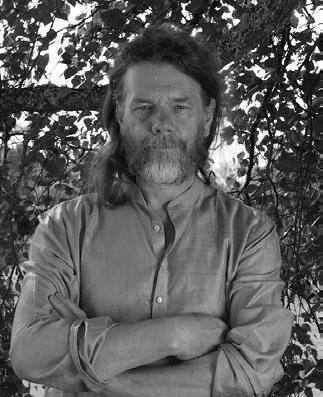

Three Questions to Tony Davidson

Writer of CONFESSIONS OF A HIGHLAND ART DEALER and founder of Kilmroack Gallery

Your book is about the gallery as part of a wider ecosystem. How do you feel the story of gallery and glen reflects global changes?

One of the themes of CONFESSIONS is that everything connects. In the book, I connect first with artistic and glen families, and then, as the gallery grows, it connects with more of the world, into something beyond physical geography. The word ‘ecosystem’ is a good one because the health of the gallery (and the world) is measured by a complexity of interrelationships. Like an ancient forest, it is the richness of connections that make it strong. I see art as a battle against simple two-dimensional monoliths. It increases connections.

Your current exhibition pays homage to some of the artists you have represented over the years including Gerald Laing. How have artists shaped your approach as an art dealer?

Kilmorack behaves artistically. Gerald Laing one told me that ‘there’s no such thing as good enough’ and I’ve taken that to heart. It’s best to do your best. I believe that a fairy dies every time a company is guided only by financial decisions. True longevity and worth are about more important things than paying safe and chasing a buck.trained as an artist

22

and this was my calling. One day I packed up my belongings and left the city, never to return. I remember waking up the following day in a highland village thinking ‘what have I done.’ Life was quiet, and I had left all my friends and urban lifestyle behind.

Some would say that establishing a gallery is a special kind of madness. What has enabled the gallery to thrive and what do you feel are its greatest assets?

Everything we do is a kind of madness. Our actions are both important and unimportant and should be both remembered and forgotten. I both care, so I do a good job, and don’t care, so I can move on. The maddest are probably the people that follow the straight path.

Available from the gallery, Amazon and a few good book shops more questions and answers

23

OneTrain,Two Men and Three Trees

MARK EDWARDS

mixed media

31cm x 61cm

24

from the vaults

Snow days, 2005

+44 (0) 1463 783 230 art@kilmorackgallery.co.uk by beauly, inverness-shire iv4

26

7al

28 www.kilmorackgallery.co.uk

Last Light, Fife | CHRISTINE WOODSIDE

Disconnected | ROBERT MCAULAY

Galina iii | GERALD LAING

by Tony Davidson

Last Light, Fife | CHRISTINE WOODSIDE

Disconnected | ROBERT MCAULAY

Galina iii | GERALD LAING

by Tony Davidson

by Tony Davidson

by Tony Davidson