KUA Design

➤ A PHILOSOPHY OF TEACHING AND LEARNING THAT IS INFORMED BY SCIENCE AND IMPACTS ALL EDUCATIONAL EXPERIENCES

12 SCIENCE OF RELATIONSHIPS

14 FOSTERING BELONGING

Finding effective strategies in research and neuroscience.

4 WHY IT MATTERS

KUA’s Head of School shares why kids deserve outstanding teachers.

16 SCIENCE OF INDIVIDUALITY

18 REIMAGINING HOMEWORK

Designing purposeful, equitable, and impactful learning beyond the classroom.

6 MAXIMIZING THE BENEFIT OF SCIENCE

Director shares the evolution of the KUA Design framework.

8 KUA DESIGN ON THE HILLTOP

Putting theory into practice at Kimball Union Academy.

Quotes from KUA people on KUA Design.

BY TYLER LEWIS

Five years ago, we challenged ourselves to deeply explore what more we could be doing to deliver on our fundamental belief that every student deserves outstanding teachers, coaches, and advisors. At the same time, we were observing a tsunami of neuroscience refining age-old educational practices and spawning new insights and approaches. We were also aware of the evidence-based best practices emerging from cognitive psychology research and spilling out of the doors of practically every school of education. Our goal was to bring science-informed, usable knowledge to our faculty—knowledge they could implement alongside their current expertise to guide our work with students and create the best possible environment for holistic adolescent growth.

So, we began exploring the intersections of neuroscience, psychology, and educational research and how they aligned with and informed our mission. We landed on what we call KUA Design, an educational philosophy of teaching and learning that we apply across all our educational experiences. The evidence has guided us to refine our practices

significantly, while also affirming our mission and fundamental beliefs around education and human development.

As great KUA educators such as World Languages Chair Scribner Fauver have been saying for years, “If you win their hearts, their minds will follow.” Science has overwhelmingly reinforced the transcendent impact relationships have on learning. The instincts and trial-and-error efforts of generations of outstanding educators have led to countless beautiful insights about teaching. However, even the most creative and experienced among us have found that neuroscience expands our understanding of motivation, engagement, emotions, and “sticky” learning.

As our journey began in identifying what every student deserves, we have developed what every great teacher is hungry for: a framework for understanding and professional growth. Great educators thirst for the keys to unlock excellence and passion in every learner. We’ve observed that the deeper our educators lean into KUA Design, the larger their rings of keys become. KUA Design is built upon a framework of four

“Science has overwhelmingly reinforced the transcendent impact relationships have on learning … [and] expands our understanding of motivation, engagement, emotions, and ‘sticky’ learning.”

—TYLER LEWIS Head of School

areas, or “sciences”—relationships, individuality, learning, and well-being—presented in practical terms that educators can understand and implement immediately. With this as the structure of our professional development and commitment to our practice, we have unified our educators around mission-aligned beliefs and practices that have elevated every aspect of our program.

We hope you will join us on this exciting journey. We have witnessed our students thrive from these expanding, evidence-based consistencies in our program. We know that our framework not only supports more robust learning and academic skill development but also positively impacts students’ social-emotional well-being and the development of metacognitive skills that improve their lives here at KUA and beyond. Additionally, the reception and buy-in from our faculty has been organic and expansive. They have authored iterations of the KUA Design framework through their own research and practice, as you will see in the pages ahead. This work is 100-percent practitioner developed and refined.

I am extremely proud and appreciative of the countless hours of commitment to excellence in teaching that this work has guided. Our efforts are exceptionally well led by Anne Peterson, director of the Gosselin Center for Teaching and Learning. Her insatiable quest to understand and support great learning and teaching fuels our innovation and commitment. Her work has impacted many teachers and learners, and that circle continues to expand with this publication. I am also deeply grateful to work with a faculty committed to a growth mindset and the curiosity to explore how they can use research, observation, and iteration to improve the lives of the young people they serve. Finally, I would like to thank our students, parents, and external thought partners for their feedback and insights as we have sought to translate the science into practice. As we continue our journey and evolution, we welcome your questions and contributions to this evolving dialogue. K

EDITOR

TRICIA MCKEON

Director of Marketing and Communications

Kimball Union

EDITORIAL DESIGN

WENDY MCMILLAN ’78 P’09 ’11

McMillan Design

COPY EDITOR

THERESA D’ORSI

PHOTOGRAPHY

COURTNEY CANIA

CONTRIBUTORS

JENNY BLUE, BILL DIAMOND, JULIE HASKELL, TYLER LEWIS, TRICIA MCKEON, ANNE PETERSON, TUCKER PRUDDEN, MATTHEW WILLIAMS, SCOTT WINHAM

KUA DESIGN ADVISORY BOARD

CHRISTOPHER DAY

Head of School, Cardigan Mountain School

NICOLE FURLONGE PH.D.

Professor of Practice and Executive Director of The Klingenstein Center, Teachers College Columbia University

JOELLA LYKOURETZOS P’25 Educator and Philanthropist

SARAH MCMILLAN ED.D.

CEO/Developmental Psychologist, McMillan Education

PHIL PECK

Retired Head of School, Holderness School

GLENN WHITMAN

Dreyfuss Family Director, Center for Transformative Teaching and Learning

KIMBALL UNION ACADEMY

(KUA) is a top private school in New Hampshire, offering high school students in grades 9 through 12 or a postgraduate year with a transformative college-preparatory education that places individual growth and development at its core. Founded in 1813, and one of the oldest boarding schools in the nation, KUA is rooted in history, yet unbound by tradition.

Our mission is to create a deep sense of belonging for every member of our community. Through intentionally designed experiences and challenges our students develop the knowledge, voice, and character to live with purpose and integrity.

KUA Design Review welcomes letters and comments. Email Tricia McKeon at tmckeon@kua.org. For more information about KUA Design, please contact Anne Peterson at apeterson@kua.org.

KIMBALL UNION ACADEMY PO Box 188, Meriden, NH 03770

Director shares the evolution of the KUA Design framework.

Anne Peterson brings 25 years of teaching and working with students one-on-one at the secondary school level—experience founded on an enduring love for neurodiversity and the desire to help all students become more knowledgeable, strategic, and purposeful learners. Here, the director of the Gosselin Center for Teaching and Learning (GCTL) talks about the introduction and development of KUA Design.

What is your role at KUA?

I am the director of the GCTL, now in my 10th year at the Academy. My role has evolved alongside the center’s mission, which now supports all students at KUA, not only those enrolled for learning supports. While I continue providing one-on-one support and collaborating with the GCTL team, I also work closely with faculty and administrators to plan and implement professional development initiatives, including the KUA Design Fellows program. I also collaborate with colleagues to refine our program.

Can you elaborate on the development of the framework that guides KUA Design?

In the summer of 2022, a team of faculty from different disciplines researched neuroscience-informed educational best practices. We explored mind, brain, and education science, focusing on research at the intersections of neuroscience, psychology, and education. The practices we found fit into four basic “sciences” that align with the values we hold at KUA. This framework features 28

teaching elements or strategies. For the past three summers, different faculty groups have conducted audits to add, delete, or consolidate elements based on findings from the previous year.

The word “iteration” is used frequently when discussing KUA Design. Does that mean this is an evolving process?

Yes, because iterating is central to any sound teaching philosophy! Research can guide us, but every educational practice is implemented with unique individuals in a

specific context—not a lab. We use evidence-based practices and carefully observe their effectiveness, iterating as needed. This requires a growth mindset and the flexibility to adjust as circumstances change.

How do you know KUA Design is working for students? Have you seen outcomes since its implementation?

This is the million-dollar question! In many cases, the answer is clear. For example, if a teacher gives students a dense, sophisticated reading assignment designed to engage them in

productive struggle and the teacher is met with blank stares, they need to adjust. Obviously, the plan isn’t working! We must find a way—in this case, by scaffolding instruction, perhaps by providing additional context or vocabulary—for students to gain purchase with the material so they can dig in and do the hard work we are asking of them.

We must constantly assess what’s working and what isn’t. However, the basics of learning are pretty straightforward: Our brain’s neural networks, which are made up of billions of neurons and connections, “learn” through effortful practice and making connections to prior knowledge. We’ve seen clear evidence of this, such as when students actively engage with material and practice problems until they can solve them independently—this leads to better performance on assessments and longer-term retention. We have known for almost a century that neurons that fire together, wire together! On a separate note, we’ve also seen that our evening “Tech Turn-in” program for ninth-graders has reduced unexcused tardies for first-period classes. We have data on this.

That said, many outcomes, such as improving teacher-student relationships or the effects of offering assignment choice, can be harder to measure. Teachers and students are, after all, complex human beings. In these cases, we rely on student feedback, research, and careful observation, with KUA Design principles as our guide. Continuous learning and improvement are at the heart of KUA Design and our mission as educators.

KUA DESIGN consists of four basic “sciences” that align with the values we hold at KUA. This framework features 28 teaching elements or strategies.

—ANNE PETERSON Director of the Gosselin Center for Teaching and Learning

How does KUA Design impact the work of the faculty?

Our faculty now have a clear roadmap to guide their work with students. In addition to aligning us around a shared purpose, this framework enables each faculty member to grow their practice in specific aspects. Teachers, especially early-career educators, today have a distinct advantage over those entering the field five or 10 years ago, especially if they’re staying informed by research.

KUA has been around for more than 200 years. Has this new approach changed the Academy’s offerings or core mission?

The core of KUA remains unchanged; it’s always been committed to relationships and the development of the whole person. However, KUA Design has given us a more structured, research-based approach to teaching. We now have concrete answers to long-debated topics and strong affirmation of our longstanding values around relationships, well-being, and seeing each student as a unique individual.

Research is evolving. How do you stay on top of the most recent research-informed practices?

Actively seeking out new research and using it to improve our practices is one of my favorite parts of my job. The GCTL serves as a clearinghouse for this information. While I’m confident in the current framework’s science and comprehensive nature, we will continue to tweak it as we refine our priorities. Faculty are deeply involved in this process. For the past two years, we’ve sent cohorts to the Learning and the Brain Conference in Boston to explore how advances in brain science can inform our work. Our professional development is aligned with KUA Design, and the ongoing contributions of colleagues are instrumental in bringing fresh research and ideas to the table.

What’s next?

Our current framework focuses on how teachers can implement best practices for students, and we’re also working to expand efforts to create a program specifically for students. This program will equip students with knowledge about how their brains learn and strategies to enhance their own learning.

Approaching this work from both the teacher and the student perspectives is key to maximizing the benefits of science. While teachers implement brain-based practices, students must be empowered with the tools to take ownership of their learning—both at KUA and beyond. This dual approach will create an even more robust learning environment. K

HERE’S A SAMPLING OF WHAT SOME KUA FACULTY ARE LISTENING TO AND READING TO UNDERSTAND SCIENCE-BASED PRACTICES THAT CAN IMPACT THEIR EVERYDAY LIVES.

HUBERMAN LAB

Stanford neuroscientist

Andrew Huberman discusses science and science-based tools for everyday life.

THE HIDDEN BRAIN

Explore the unconscious patterns that drive human behavior and questions that lie at the heart of our complex and changing world.

THE HAPPINESS LAB

Yale Professor Laurie Santos shares the latest scientific research and some surprising and inspiring stories that will change the way we think about happiness.

Permission to Feel: Unlocking the Power of Emotions to Help Our Kids, Ourselves, and Our Society Thrive Yale Professor Marc Brackett emphasizes the importance of recognizing and expressing all emotions for personal growth and well-being, introducing the “RULER” method to help individuals manage feelings and foster healthier relationships.

Validation: How the Skill Set That Revolutionized Psychology Will Transform Your Relationships, Increase Your Influence, and Change Your Life Psychologist Caroline Fleck explores how the powerful skill of validation—demonstrating empathy and understanding— can transform relationships, enhance self-compassion, and drive meaningful change in personal and professional contexts.

The Anxious Generation NYU social psychologist Jonathan Haidt argues that increased access to technology, social media, and overprotective parenting has significantly contributed to a rise in mental health issues, particularly anxiety, among young people.

Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI Wharton Professor Ethan Mollick explores how artificial intelligence—as a co-worker, co-teacher, and coach—is reshaping business and education and urges us to harness its power while retaining our identity and mastering collaboration with intelligent machines to create a better future.

Chatter: The Voice in Our Heads, Why It Matters, and How to Harness It University of Michigan psychologist and professor Ethan Kross offers the science and practice of harnessing our inner voice.

Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain

Northeastern University Professor Lisa Feldman Barrett provides a concise exploration of the brain’s workings, debunking common myths about emotion and perception while offering a fresh perspective on how our minds construct experiences.

Science has overwhelmingly reinforced the transcendent impact relationships have on learning.

“If you win their hearts, their minds will follow.”

—SCRIBNER FAUVER World Languages Chair

70 percent of teenagers are sleep-deprived, according to multiple studies. This contributed to KUA’s Tech Turn-In initiative for ninth-graders to help foster healthy sleeping habits by turning in tech devices by 10:30 p.m.

BECOME A SCIENTIST TO IDENTIFY AND NEGOTIATE YOUR EMOTIONS.

How do you feel right now? If you answer with “fine,” “okay,” “meh,” or “good,” take a moment to put a finer point on it. For example, if you’re feeling fine, be more specific: pleasant, content, at ease?

Dr. Marc Brackett, the founding director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, shared with KUA faculty during a professional development workshop that 25 years of data show how successfully identifying and negotiating our emotions—and those of others—has a positive effect on our academic progress, workplace success, relationship quality, and life satisfaction. Most importantly, we can learn to become more skillful regarding our emotional lives.

To do so, we must practice recognizing, understanding, labeling, expressing, and regulating our feelings. You can get started by downloading and exploring Dr. Brackett’s free app, How We Feel, which aims to help people identify feelings and become more skillful in dealing with them.

TEACHERS INTEGRATE ELEMENTS OF THE KUA DESIGN FRAMEWORK INTO CLASSROOM PRACTICES.

While developing the KUA Design framework in the summer of 2022, questions arose about its implementation. What mechanisms would encourage and ensure that faculty adopted brain-based strategies in their work with students? One such mechanism became what we call “10% Goals.” We borrowed this idea of 10% Goals from the Center for Transformative Teaching and Learning (CTTL). The idea is not that teachers radically change overnight; rather, they would focus on manageable, steady growth in their practices.

While many elements of the framework, such as “modeling a culture of empathy and kindness,” were already commonly practiced by KUA teachers, others, such as regularly integrating retrieval practices each week, were less familiar to many educators. To encourage faculty to adopt these less familiar strategies—and recognizing that professional development is most effective when educators have agency— we asked them to choose one element they weren’t already using and wanted to implement. By focusing on one (or possibly two) elements each year and committing to genuine effort, faculty will gradually integrate most, if not all, of the framework’s relevant elements into their teaching practices.

During the 2022-2023 school year, we supported this initiative by organizing small Professional Learning Community (PLC) groups that met periodically throughout the year. These groups provided mutual support for achieving goals through class visits and group discussions.

In the following academic year, we repeated the process of selecting new 10% Goals. We continued meeting in PLC groups and added a new component: a nameplate for each faculty member. These nameplates, displayed outside classrooms or offices, included the teachers’ 10% Goals, their names and departments, and books or events that inspired them professionally. This transparent sharing with students, parents, and colleagues fostered even greater commitment to the 10% Goals.

This year, we introduced a redesigned teacher evaluation process to support the 10% Goals elements. Every teaching faculty member is now partially evaluated on the practice of their 10% Goals. Faculty are asked to collect evidence of these practices within their classrooms and write short reflections on their progress during the first trimester. Each teacher then meets with the department chair to review goals, practices, evidence, and self-reflections. Following this meeting, the department chair writes a brief reflection. The same process will be repeated in the spring, with all documents shared with the academic leadership.

The gradual introduction of the 10% Goals, along with the implementation of ongoing support and growing expectations, has motivated our faculty to embrace the KUA Design framework and apply its principles in their teaching. These practices have become an integral part of our classroom culture. Teachers report that KUA Design strategies enhance classroom culture and outcomes while helping students feel better supported in their learning. —Julie Haskell

“Teachers report that KUA Design strategies enhance classroom culture and outcomes while helping students feel better supported in their learning.”

—JULIE HASKELL Dean of the Faculty, Visual Arts Teacher

Kimball Union Academy hosted the Science of Teaching and School Leadership Academy in partnership with the Center for Transformative Teaching and Learning (CTTL) at the St. Andrew’s School. The four-day conference in July 2024 brought together teachers and school leaders interested in how the brain learns and how to create learning experiences informed by the most promising mind, brain, and education research and strategies.

“The field of neuroscience has exploded in the past two decades, with new applications of the research seeming to come online practically daily,” says Anne Peterson, director of the Gosselin Center for Teaching and Learning. “Our commitment to the application of this research has been tremendously impactful on our teaching and our students learning here at KUA. We are excited to partner with the CTTL to help broaden understanding of this important work.”

Faculty from KUA, plus educators from around New England and KUA’s partner school in Scotland, Robert Gordon’s College, participated.

“I came out of the conference at KUA last summer so energized about my teaching, and that was exactly what I had been looking for,” says Desiree Sheff, mathematics teacher at Concord Academy. “I had about 30 different things that I wanted to try out and realized that I had to narrow it down to two or three. Those have been highlights of my year so far.”

10 % Goals

has motivated our faculty to embrace the KUA Design framework and apply its principles in their teaching.

THE KUA DESIGN FELLOWSHIP is a dedicated summer research and professional development opportunity for faculty to advance neuroscience and research-informed teaching practices within the Kimball Union community. In its first year, the Academy selected four fellows to engage in research related to their professional work. These educators, representing departments across campus, undertook projects related to curricular and co-curricular areas of the KUA program that tied directly into the KUA Design framework. Each fellow completed a literature review of their research, wrote about their findings, and presented their work to faculty colleagues. (See pages 14, 18, 22, 26 for this year’s Fellowship reviews)

Positive relationships are foundational to learning because they motivate healthy connections and growth.

6 Get to know your students and their unique stories.

6 Model and encourage a culture of empathy and kindness.

6 Promote physical and social-emotional safety in all areas of school life.

6 Cultivate an awareness of your personal biases and cultural blind spots.

6 Ensure that all students—regardless of their age, nationality, gender, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, ability, socio-economic status, or other personal identifiers—feel known, heard, and respected.

6 Make all physical spaces reflective of those represented in them.

6 Build and maintain healthy boundaries with students.

BY MATTHEW WILLIAMS

When I joined Kimball Union Academy in 2023, I was tasked with defining belonging for our community—a challenge that felt both exciting and deeply meaningful. Through a series of interviews, small group discussions, surveys, and audits, I worked to understand what belonging means to the students and employees at KUA.

This process led to the creation of the following definition: “At Kimball Union Academy, fostering belonging is a continual commitment, ensuring every member feels welcomed, respected, and valued. This involves deliberate actions that demonstrate inclusivity and support, recognizing the diverse experiences and perspectives within the community. True belonging embraces differences while finding common ground, creating safe spaces for authentic expression. It’s a shared responsibility among all members to cultivate an environment where everyone feels included, supported, and empowered to be themselves, fostering connections and friendships within the community.”

Although this definition encapsulated the essence of belonging at KUA, I was left with a lingering question: How could this philosophy be translated into tangible, actionable strategies in the classroom? This curiosity propelled me into further research, with the goal of answering two burning questions: Is belonging actually important and are there measurable, data-centric outcomes that show its necessity. One of the key findings was that

when students feel they belong, it activates the brain’s reward system, which in turn releases dopamine that enhances motivation, engagement, and emotional well-being (Lieberman and Eisenberg, 2009). The classroom can be an intimidating place for students, so realizing that a student’s sense of self within the classroom reduces stress and increases engagement excited me as it meant I was on the right path. To deepen my understanding of the relationship between neuroscience and diversity, I attended the Center for Transformative Teaching and Learning conference in July 2024 at KUA. This experience proved pivotal. The conference focused on the intersection of neuroscience, diversity, and equity, providing a foundation for how cognitive science can inform educational practices. One of the most impactful moments came from my conversations with Dr. Michael Platt, a keynote speaker and neuroscientist from the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Platt’s research explores how the brain processes social behavior, and his insights into the biological underpinnings of bias—how mirroring, synchronicity, and shared goals influence belonging—were transformative for my work. His guidance reinforced the importance of designing strategies rooted in an understanding of how the brain works, particularly in the context of fostering inclusivity and mitigating bias in educational settings. Bias, as Dr. Platt explained, is biologically ingrained in the

human brain—a survival mechanism that helps us make quick decisions but can also lead to unconscious prejudice. However, the prefrontal cortex—the brain’s center for rational thinking and self-regulation—can help override our biology, allowing for more thoughtful and equitable interactions (Platt, 2020).

My research culminated in the development of several actionable strategies, rooted in neuroscience, to foster belonging in the classroom. These insights underscored the importance of tools such as bias checklists, which engage the prefrontal cortex to bring implicit biases into conscious awareness. For example, a bias checklist for classroom interactions might prompt educators to reflect on whether their teaching materials represent diverse perspectives or are unintentionally favoring certain students in discussions.

One example strategy that came out of this research is blind grading. Blind grading emerged as a powerful tool to reduce stereotype threat, a phenomenon where anxiety about confirming negative stereotypes can impair performance (Quinn, 2021).

By removing identifying information from student assignments, blind grading reduces bias and levels the playing field, ensuring assessments reflect true learning and ability.

Studies conducted at the Yale Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning show that educators can bring in bias from students’ previous work, scores, gender, race, ethnicity and even work ethic into the assessment process. Likewise, Dr. Camille Terrier,

“This journey has highlighted the importance of continual learning and reflection.”

—MATTHEW WILLIAMS Dean of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, English Teacher

from the School Effectiveness and Inequality Initiative, discusses in her 2020 article “Boys Lag Behind: How Teachers’ Gender Biases Affect Student Achievement” how blind grading reduced inequities in the grading process for male middle school students in math classrooms. With feedback and transparency about the purpose of blind grading, students began to appreciate its equitability. While these strategies have shown promising results, implementing them requires intentionality, consistency, and collaboration. For example, blind grading necessitates additional preparation and clear communication with students.

Strategies such as timely and actionable feedback are one of the most powerful tools for enhancing student learning, with high-quality feedback shown to accelerate progress by up to eight months (AITSL, 2017). To maximize its impact, feedback must be timely, specific, and constructive, offering students clear guidance on their strengths and areas for improvement. When delivered effectively, feedback fosters motivation, engagement, and a sense of ownership over learning, encouraging students to reflect on their progress and apply actionable steps for growth. These practices not only improve outcomes but also empower learners to take charge of their educational journey. The improvements I have observed in classroom culture—greater student engagement, reduced anxiety, and a stronger sense of community—are a testament to the transformative

potential of these teaching practices. This journey has highlighted the importance of continual learning and reflection. Conducting research is not a linear process but a dynamic and iterative one, requiring educators to adapt their practices based on new insights and evolving student needs. And fostering belonging is not a one-time initiative but a continual commitment—a shared responsibility among educators, students, and the broader community. By grounding our practices in research, we can intentionally create environments that not only support academic success but also nurture the well-being and growth of every individual. K

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). Spotlight: Reframing Feedback to Improve Teaching and Learning (2017). https://www.aitsl.edu.au/tools-resources/resource/spotlight-reframing-feedback-to-improve-teaching-and-learning. Lieberman, Matthew D., and Naomi I. Eisenberger. “Pains and Pleasures of Social Life.” Science 323, no. 5916 (2009), 809–891. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1170008. Platt, Michael. The Leader’s Brain: Enhance Your Leadership, Build Stronger Teams, Make Better Decisions, and Inspire Greater Innovation with Neuroscience. Wharton School Press, 2020. Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning. “Blind Grading.” Yale University. https:// poorvucenter.yale.edu/BlindGrading.

Quinn, David M. “How to Reduce Racial Bias in Grading.” Education Next 21, no. 1 (2021).

Terrier, Camille. “Boys Lag Behind: How Teachers’ Gender Biases Affect Student Achievement.” Economics of Education Review 77 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. econedurev.2020.101981.

All brains are unique and draw from their individual abilities and experiences.

6 Teach content using multiple modalities.

6 Provide students with choice in the acquisition and demonstration of knowledge.

6 Help students build their metacognition and become more independent learners.

6 Manage cognitive load and working memory demands so students can focus on learning goals.

6 Use direct instruction to introduce students to new concepts and material, recognizing that inquiry based learning has its place.

6 Define key terms, concepts, and symbols and check for understanding.

6 Encourage and support productive struggle, scaffolding instruction to meet the needs of all learners.

BY BILL DIAMOND

Why do I assign homework that looks, reads, and feels like something I did 30 years ago? This was the question I asked myself as I embarked on a summer research project as a KUA Design Fellow. My goal was to delve into the role of homework in modern education, exploring its potential as a transformative tool rather than a rote task. My study focused on a literary review of homework studies that span the last 40 years: best practices, teacher and student motivation, and the efficacy and efficiency of homework as an extension of the classroom experience through the lens of KUA Design. By examining this rich body of research, I sought to understand how intentional homework design could better align with students’ diverse needs, foster intellectual curiosity, and support long-term learning. I also had the opportunity to create a workshop where I presented my findings and led KUA colleagues in a homework design creation exercise.

Before this study, I recognized homework as a key tool for introducing and reinforcing content and preparing students for assessments. However, I began to question whether traditional approaches were achieving their full potential. In 2006, the most widely referenced and comprehensive meta-analysis of the effects of homework on student achievement, published by Cooper, Robinson, and Patall, found “generally consistent evidence for positive influence of homework

“For summative homework, feedback is a cornerstone of my approach.”

—BILL DIAMOND Chair of the History Department

on achievement.” Yet, I wondered: What makes some assignments effective while others feel like mere busy work? My research revealed that purpose, equity, and feedback are critical components of meaningful homework, challenging me to rethink how I design and implement assignments.

Central to my findings was the importance of articulating the purpose of homework. Research by Xu and Wu (2012) demonstrates that students engage more deeply when they understand the “why” behind their work. Reflecting on my classroom practices, I realized assignments often lacked the specificity needed to connect with students’ intrinsic motivations. Inspired by this insight, I now ensure that every task has a clear purpose that is communicated to students. For instance, reading assignments are paired with guiding questions to focus attention on key themes, a practice that I have previously used, but I am now in tune with ensuring questions align more closely with how they are used during class discussions.

Another transformative element of my study was exploring some of the roles that equity and neurodiversity play in homework practices. Studies by Cooper (2006) and Hong (2004) underscore the importance of tailoring assignments to account for students’ unique processing speeds, access to resources, and self-regulation abilities. These ideas also guided my efforts to integrate homework more seamlessly into classroom instruction. For instance, I frequent-

ly model expectations for assignments during class, using scaffolded examples to provide students with a clear roadmap. This approach not only increases student confidence but also fosters a sense of ownership and accountability. Additionally, I’ve prioritized offering my students opportunities for collaboration whenever possible, empowering them to engage with assignments in ways that resonate personally. Through my research, I was reminded how significant the role of feedback is in transforming homework from a perfunctory exercise to a meaningful dialogue. Research underscores that actionable feedback, rooted in metacognition, not only enhances student learning but also nurtures resilience and a growth mindset.

The most comprehensive transformation of my homework practice is in my “Advanced Topics: Geopolitics Since the Fall of Saigon” course. I have applied strategies from my fellowship research to create purposeful and student-centered assignments. To provide flexibility, I set a weekly due date for homework, allowing students to balance their workloads effectively. Each reading is paired with guided questions and reflections, encouraging deeper engagement with the material. Drawing from Sallee’s research and 2008 article, “Doing our Homework on Homework: How Does Homework Help?” I emphasize learning over grades. Weekly homework is capped at 15 percent of the course grade, reinforcing its formative purpose. For summative homework,

feedback is a cornerstone of my approach, with written assignments returned alongside detailed comments and questions to prompt further inquiry and refinement. The key is to ensure feedback goes beyond checking for completion (McGlynn, 2019). I have also incorporated opportunities for collaboration and creativity, such as group analyses of geopolitical scenarios that challenge students to think critically and solve problems collectively. For example, in studying the history that led into the Iranian hostage crisis, I asked groups of students to prepare a briefing for President Carter on action steps he could take in response to the situation. These practices have transformed homework into a meaningful extension of the classroom, driven by flexibility, feedback, and student agency.

Additionally, one of the most impactful practices I implemented this year was conducting regular homework surveys to collect data on student preferences and the efficacy of their work outside the classroom. These surveys provided invaluable insights into how students perceive assignments, the challenges they face, and the conditions under which they thrive.

My work this year has reshaped my understanding of what homework can and should be. To translate these findings into actionable strategies, I developed a Homework Creation Template and Homework Audit Sheet. These tools serve as frameworks for designing assignments that align with best practices. The

Homework Creation Template, for example, prompts educators to consider the purpose of an assignment, the estimated time required for completion, opportunities for differentiation, and how the task connects to summative assessments. By using this template, I ensure that each homework task is intentional, meaningful, and tailored to meet diverse student needs. By aligning assignments with the principles of purpose, equity, and feedback, I aim to create a classroom culture that values inquiry, effort, and reflection. K

Cooper, Harris, Jorgianne Civey Robinson, and Erika A. Patall. “Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Research, 1987–2003.” Review of Educational Research 76, no. 1 (2016): 1–62. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543076001001.

Hong, Eunsook, Roberta M. Milgram, and Lonnie L. Rowell. “Homework, Motivation and Preference: A Learner-Centered Homework Approach.” Theory Into Practice 43, no. 3 (2004): 197–204. https://www.jstor. org/stable/3701521.

McGlynn, Kaitlyn, and Janey Kelly. “Building a Bridge Over Homework: How to Design At-home Assignments That are Both Valuable and Effective.” Science Scope 42, no. 6 (2019): 36–41. https://www.jstor. org/stable/26898905.

Sallee, Buffy, and Neil Rigler, N. “Doing our Homework on Homework: How Does Homework Help?” The English Journal 98, no. 2 (2008): 46–51. https://doi.org/10.58680/ ej20086828.

Xu, Jianzhong, and Hongyun Wu. “Self-regulation of Homework Behavior: Homework Management at the Secondary School Level.” The Journal of Educational Research 106, no. 1 (2012): 1–13. https://doi. org/10.1080/00220671.201.

Memory, attention, assessment, and feedback are essential to the learning process.

6 Integrate retrieval practices into your work with students to strengthen long-term memory and knowledge transfer.

6 Give frequent, low-stakes formative assessments to monitor student learning and guide instruction.

6 Provide all feedback as quickly as possible; make it actionable and be mindful about how it will be received.

6 Build comprehension through scaffolded notetaking instruction and the use of skeleton/partial notes.

6 Minimize distractions in the learning environment and leverage strategies to maximize student attention.

6 Highlight patterns, emphasize relationships, and provide background knowledge and skills as needed.

6 Communicate the most essential content at the beginning and end of your time with students, using the time in the middle for practice.

BY JENNY BLUE

After Open AI launched

ChatGPT in 2022, I gave a speech to the KUA community about the power of generative AI, which can create original written content in response to a prompt. I warned students not to allow a chatbot to rob them of their agency. I told them that words have power when they reveal personal truth, and that identity and voice and integrity are intertwined. I asked them, “If you cede the development of your voice to a chatbot—if you allow it to do the thinking for you— then how will you know who you are?” I went on to assure them that I would never outsource my work to generative AI. I concluded with all the vehemence I could muster: “I will continue showing up for you in all my flawed humanity. I ask that you do the same.”

Now, thanks to learning about generative AI through my work as a KUA Design Fellow, I am less interested in guarding students against AI and more interested in harnessing its power as a teaching and learning tool. The KUA Design Fellowship has given me confidence in my ability to adapt to a world where generative AI will be a constant learning partner for students and teachers rather than a threat to learning.

Last summer, I plunged into the nascent body of research on generative AI’s growing presence in education, specifically in the English classroom. I read myriad studies and synthesized my findings into an essay that was part literature review, part meditation. I also explored ways in

“Most importantly, generative AI has given me more time to build relationships with students.”

—JENNY BLUE

The Peter Holland ’57 Lionel Mosher Chair of English

which I could cultivate what Ethan Mollick, who studies innovation and entrepreneurship at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, calls “co-intelligence.” Although I remained ambivalent, AI’s power intrigued me, and I emerged from the summer invigorated by its potential to transform my teaching practice.

This past fall, I began using generative AI to help build writing rubrics, lesson plans, and assignment models. By making my expectations transparent and more accessible, AI is improving my students’ learning. Their writing now more closely aligns with my expectations, and I can easily tweak any of these tools with a simple command rather than having to rewrite them from scratch.

Most importantly, generative AI has given me more time to build relationships with students: Rather than spending hours upon hours innovating on my own, I now use that time to meet with students and connect with members of the KUA community. In fact, I have even been able to join our winter musical production of Les Misérables because I have more available time to spend with students and colleagues.

While the advances that generative AI promises are exciting, they also pose significant ethical issues that we must address as educators. We need to help our students understand that their voice matters and create the conditions in which they are willing to productively struggle to bring their own ideas into the light. Teachers such as

Emily Pitts Donahoe (2024) write about how generative AI enables the contours of writing instruction to fall into sharp relief. I agree. Now that generative AI is here, teachers and students of writing need to reckon with what matters when we ask students to write. We cannot slam the door on generative AI since students have already let it in—as have I, with tools such as Brisk, Grammarly, and ChatGPT 4.

As gatekeepers, teachers have control over how it shows up in our classrooms. We can learn how to set a table for this new guest, to welcome parts of it in and leave other parts behind. KUA is, as a school community, actively engaged in this process. Because of my research on generative AI, I have led faculty workshops on AI literacy and contributed to building a comprehensive academic policy around the use of this technology.

I haven’t felt this excited to be an English teacher since I first began at KUA, when everything was new. Even though I have been teaching for more years than Ulysses spent away from Ithaca, I feel like I am setting out on an adventure. I am indeed, as he said, “a part of all that I have met”—including, it turns out, a generative AI. K

Donahoe, Emily P. “The AI Skills Students Really Need.” Unmaking the Grade (blog), June 14, 2024. https://emilypittsdonahoe.substack. com/p/the-ai-skills-students-really-need. Mollick, Ethan. Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI. Penguin, 2024.

Emotion, cognition, and physical well-being are interlinked.

6 Support mindful habits around nutrition, exercise, sleep, and devices.

6 Teach students how to identify and manage stress.

6 Make time and space for joy, humor, and play.

6 Teach students to recognize, label, and regulate a wide range of emotions.

6 Help students develop their personal values, strengths, and purpose.

6 Nourish students’ sense of place, both locally and globally.

6 Embrace and promote the expectation that every student can grow.

BY SCOTT WINHAM

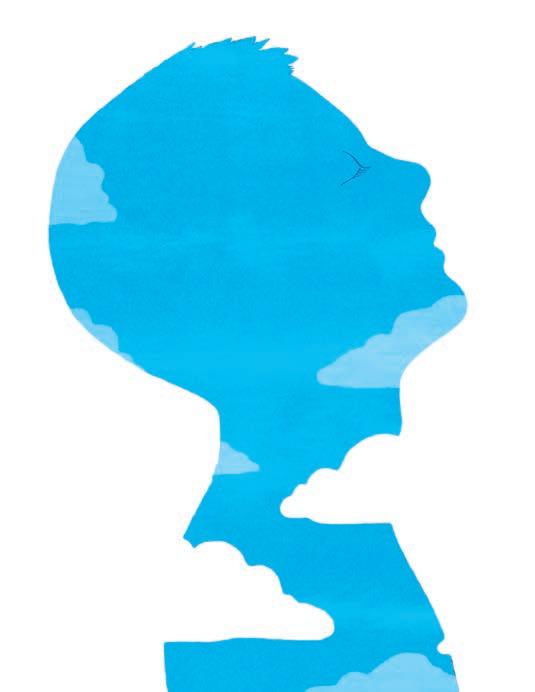

As the dean of Residential Life, I am interested in how to optimize our boarding students’ time in their dorms. Initially, I hoped to consider the aspects of dorm life between dinner and “lights out”—when students must turn out the lights and go to sleep—during my fellowship. However, after beginning this process, I realized two things: First, sleep is crucial for many reasons, especially to teens; and second, everything that happens between dinner and lights out can impact healthy sleep. Although I have always known the importance of sleep, I had not fully appreciated the many ways it impacts our students’ well-being and academic performance. Through my research, I discovered several fascinating insights into adolescent sleep patterns and how we, as a school, can foster positive sleep hygiene. The scientific community has long established the critical role of sleep. However, some findings stood out for our work with teenagers. Teen brains naturally shift to prefer later sleep onset due to delayed melatonin production. This change means that traditional, early school start times may not align with their biological clocks. Additionally, our evolutionary history suggests we are designed to sleep in sync with natural light cycles, highlighting the importance of exposure to natural light. Another crucial point is that

while individual sleep needs vary, the optimal duration for teens is around nine hours. These factors became guiding principles in evaluating our current practices and exploring areas for improvement.

I came across studies by Feinberg and Campbell (2009) that used EEG readings to shed light on the changes in sleep patterns during adolescence, emphasizing the significance of slow-wave sleep and REM sleep in memory consolidation, cognitive development, and synaptic pruning. Their work underscores how crucial adequate sleep is for teens, not just for rest but for their overall brain development. The role of sleep in consolidating memory and the development of the prefrontal cortex—responsible for executive functions such as impulse control and anxiety management—further solidifies the need for prioritizing sleep in our students’ routines.

The physical benefits of sleep are equally compelling. According to Mason et al. (2023), adequate sleep is crucial for physical growth, muscle recovery, and overall health. Adolescents who get less than eight hours of sleep are significantly more likely to sustain injuries and have weakened immune systems. This reinforces the need to advocate for better sleep hygiene as part of our students’ physical well-being, especially for student-athletes.

Reflecting on our practices at

“The role of sleep in consolidating memory and the development of the prefrontal cortex … further solidifies the need for prioritizing sleep in our students’ routines.”

—SCOTT WINHAM Dean of Residential Life

KUA, I found that our lights-out policy and the nightly shut-down of the internet at 11:30 p.m. support healthy teenage sleep patterns, aligning reasonably well with our students’ natural rhythms. Our 8:30 a.m. class start times, though constrained by various factors such as sports and meals, also seem to strike a balance, though there is always room for improvement. The timing of our Study Hours, from 8 to 9:30 p.m., followed by a later lights-out, appears beneficial based on research by Holz et al. (2012) and Gais et al. (2006). These studies showed that learning activities conducted shortly before sleep positively impact memory consolidation, particularly when followed

by adequate rest, and reinforce the importance of structuring evening activities in a way that supports both learning and sleep.

Exposure to light emerged as another critical factor. Bright or blue light exposure in the evening delays melatonin production, disrupting sleep onset. Conversely, morning sunlight helps regulate sleep cycles. This insight has prompted me to consider ways to adjust our dorm environments, perhaps by dimming lights in the evening and encouraging natural light exposure in the mornings, and we will be conducting dorm audits to see where we can make improvements. Also, simple activities such as walking to the dining hall before class can offer valuable morning light exposure, aiding in better sleep regulation. For our students who live in different time zones than KUA, it is of the utmost importance to get as much natural light as possible when they are reacclimating to the rhythms of campus life.

Technology use before bed is another area of concern. Hysing et al. (2015) highlighted the negative impact of screen time on sleep, including shorter duration, delayed onset, and overall sleep deficiency. Encouragingly, face-to-face social interactions, as discussed by Jones and Wikle (2023),

promote better sleep patterns. This insight has been instrumental in shaping our policies, such as the new “Tech Turn-in” policy for ninth-grade boarding students. The anecdotal feedback has been positive, with students reporting getting more sleep and parents appreciating the initiative. This success has sparked discussions about extending similar opportunities to other grade levels.

While policies can set the stage, empowering students with knowledge about healthy sleep practices is crucial. This fall, we initiated a program of educating dorm proctors on the importance of sleep and asking them to lead dorm meeting activities designed to educate our boarding students and promote positive sleep hygiene. The inaugural meeting in October focused on brain science and the impact of sleep on brain development and cognitive function, featuring an engaging trivia contest. Ongoing work will focus on the physical benefits of sleep and the impact of light and how nutrition affects healthy sleep. Additionally, sharing this information with parents ensures a holistic approach, reinforcing these habits both at school and at home.

This fellowship has deepened my understanding of the multifaceted role of sleep in adolescent development. While I always knew sleep was important, this research has illuminated just how critical it is for cognitive, emotional, and physical health. KUA’s current practices are on the right track, but there is always room for growth. By continuing to refine our approaches, fostering a culture of awareness, and putting sleep-encouraging structures in place, we can better support our students in achieving healthy, restful nights and, ultimately, greater overall well-being. K

Feinberg, Irwin, and Ian G. Campbell. “Sleep EEG Changes During Adolescence: An Index of a Fundamental Brain Reorganization.” Brain and Cognition 72, no. 1 (2010): 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. bandc.2009.09.008.

Gais, Steffen, Brian Lucas, and Jan Born. “Sleep After Learning Aids Memory Recall.” Learning & Memory 13, no. 3 (2006): 259–262. https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.132106.

Holz, Johannes, Hannah Piosczyk, Nina Landmann, et al. “The Timing of Learning before Night-Time Sleep Differentially Affects Declarative and Procedural Long-Term Memory Consolidation in “Adolescents.” PloS One 7, no. 7 (2012). https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040963.

Hysing, Mari, Stale Pallesen, Kjell Morten Stormark, Reidar Jakobsen, Astri J. Lundervold, and Borge Sivertsen. “Sleep and Use of Electronic Devices in Adolescence: Results from a Large Population-based Study.” BMJ Open 5, no. 1 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1136/ bmjopen-2014-006748.

Jones, Blake L., and Jocelyn S. Wikle. “Activities and Social Contact as Antecedents to Sleep Onset Time in U.S. Adolescents.” Journal of Research on Adolescence: The Official Journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence 33, no. 3 (2023): 1048–1060. https://doi. org/10.1111/jora.12857.

Kinsey, Amber W., and Michael J. Ormsbee. “The Health Impact of Nighttime Eating: Old and New Perspectives.” Nutrients 7, no. 4 (2015): 2648–2662. https://doi.org/10.3390/ nu7042648.

Mason, Lorcan, James Connolly, Lydia E. Devenney, Karl Lacey, Jim O’Donovan, and Ronan Doherty. “Sleep, Nutrition, and Injury Risk in Adolescent Athletes: A Narrative Review.” Nutrients 15, no. 24 (2023): 5101. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15245101.

Tarokh, Leila, Jared M. Saletin, and Mary A. Carskadon. “Sleep in Adolescence: Physiology, Cognition and Mental Health.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 70 (2016): 182–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. neubiorev.2016.08.008.

Typaldos, Marlene, and Daniel G. Glaze. “Teenagers: Sleep Patterns and School Performance.” The National Healthy Sleep Awareness Project (2021).

Urrila, Anna S., Eric Artiges, Jessica Massicotte, et al. “Sleep Habits, Academic Performance, and the Adolescent Brain Structure.” Scientific Reports 7 (2017). https:// doi.org/10.1038/srep41678.

BY ANNE PETERSON

As adults working in a boarding school, we are acutely aware of the habits of teenagers. We spend time with students not only in the classroom but on the playing fields, in the dining room, and late into the evening while on duty in the residence halls. And we don’t need experts or studies to point out the profound presence of technology and devices in our students’ lives.

When we started discussing how to help teens better manage the impact of devices on their lives at KUA, we leaned into our approach to teaching and learning, which relies on brain science to guide our work inside and outside the classroom. Specifically, we focused on the science and data around technology and sleep to lead our efforts for the 2024–2025 school year.

We wanted to create an environment where students can interact face to face, cultivate healthier sleep habits, and, ultimately, enhance their overall well-being. Knowing how foundational sleep is for learning, we were intentional in our focus to create a cellphone policy that emphasizes sleep. In September 2024, we introduced our “Tech Turn-in” policy, which requires boarders to securely store their devices in a lockable charging station by 10:30 p.m. until 6 a.m. every night except Saturdays.

Multiple studies have shown that more than 70 percent of teenagers are sleep-deprived (Wheaton et

al., 2018; Gradisar et al., 2011).

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends that adolescents need eight to 10 hours of sleep a night to support their rapid physical, emotional, and cognitive development (Paruthi et al., 2016). Without sufficient rest, teens may struggle with focus, problem-solving, and emotional stability—all essential for their success in school and relationships. Chronic sleep deprivation also increases the risk of long-term health challenges, including anxiety and depression (Blackwelder et al., 2021).

Quality sleep is crucial for adolescent brain development, particularly for the prefrontal cortex, which governs impulse control and decision-making and is still undergoing significant development during adolescence. This brain region is highly sensitive to sleep deprivation, meaning that teens lacking sleep often face difficulties in regulating emotions, making decisions, and achieving academically (Urrila et al., 2017).

Unfortunately, electronic devices can disrupt both the quality and quantity of sleep teens get. The allure of smartphones, tablets, and laptops often keeps teens awake far beyond a healthy bedtime. Even Netflix’s cofounder has remarked that sleep, not competitors such as Hulu or YouTube, is the company’s biggest rival. Screen time before bed correlates with shorter sleep duration, delayed onset of sleep, and poor sleep quality, especially when the content is engaging or

stimulating (Hysing et al., 2015)— and when is it not?

We know from the brain science research that guides our teaching and learning philosophy that ninth grade is developmentally more challenging––and that with the right support systems, students can leverage a positive year to chart a successful path through college.

So, we focused on building a foundational program for ninth-graders. As we started crafting a policy for the youngest members of our community, we heard from health center staff who expressed concerns that if devices were not available overnight, students might lose access to mental health hotlines or medical support. We knew the policy would cause challenges for faculty on dorm duty at lights out when the devices are collected. We also knew we’d need to establish a system for emergency communication with families without burdening dorm parents with middle-ofthe-night calls. Ultimately—in consultation with the ninth-grade dean, director of IT, dean of residential life, dorm heads, and dean of diversity, equity, and inclusion—we designed and implemented a policy that includes a designated, on-call administrator for families in the case of an emergency.

We installed 24-bay charging carts in each ninth-grade dorm. Each student has their own secure charging bay with a personal code, allowing devices to charge overnight

Blackwelder, Amanda, Mikhail Hoskins, and Larissa Huber. “Effect of Inadequate Sleep on Frequent Mental Distress.” Preventing Chronic Disease 18 (2021). http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/ pcd18.200573.

Gradisar, Michael, Greg Gardner, and Hayley Dohnt. “Recent Worldwide Sleep Patterns and Problems During Adolescence: A Review and Meta-analysis of Age, Region, and Sleep.” Sleep Medicine 12, no. 2 (2011): 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. sleep.2010.11.008.

Hysing, Mari, Stale Pallesen, Kjell Morten Stormark, Reidar Jakobsen, Astri J. Lundervold, and Borge Sivertsen. “Sleep and Use of Electronic Devices in Adolescence: Results from a Large Population-based Study.” BMJ Open 5, no. 1 (2015). https:// doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006748.

Paruthi, Shalini, Lee J. Brooks, Carolyn D’Ambrosio, et al. “Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine on the Recommended Amount of Sleep for Healthy Children: Methodology and Discussion.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 12, no. 11 (2016): 1549–61. https://doi. org/10.5664/jcsm.6288.

Urrila, Anna S., Eric Artiges, Jessica Massicotte, et al. “Sleep Habits, Academic Performance, and the Adolescent Brain Structure.” Scientific Reports 7 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ srep41678.

Wheaton, Anne G., Sherry Everett Jones, Adina C. Cooper, and Janet B. Croft. “Short Sleep Duration Among Middle School and High School Students—United States, 2015.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67, no. 3 (2018): 85–90. http:// dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr. mm6703a1.

“Without sufficient rest, teens may struggle with focus, problem-solving, and emotional stability.”

and ensuring accessibility in the event a student needs to be in touch with home. At 10:30 p.m., students place their devices in the carts under dorm parent supervision. If a student needs their phone during the night and takes it from the cart, they and the dorm parent will have a follow-up conversation.

—ANNE PETERSON Director of the

Gosselin

Center for Teaching and Learning

Though a few parents had initial questions or concerns, the overall response has been positive. Many families have expressed appreciation for the steps we’re taking to support their children’s health. During our 2024 Fall Family Weekend, we hosted a forum on the Tech Turn-in policy. One common theme emerged: Why limit this program to ninth-graders? One parent, initially skeptical about the policy, shared that seeing his daughter benefit from improved rest and focus changed his perspective entirely. Another parent shared that they “have plenty of evidence that the Tech Turn-in is working. We were pleasantly surprised with the level of engagement we witnessed from students in general and especially our son during class time.”

Although it would be an overstatement to say our ninth-graders openly appreciate having their devices stored each night, the benefits are becoming evident. One student remarked, “If we didn’t have Tech Turn-in, I wouldn’t get enough sleep.” The ninth-grade dorm heads observe that the dorms quiet down quickly, with more (continued p. 30)

students heading to the gym in the morning than in previous years. Students are more alert in class, and we’ve had 40 percent fewer unexcused tardies in first-period classes this year for ninth-grade boarding students.

We will continue the Tech Turn-in program for ninth-graders next year, and we’re considering a few adjustments. For instance, gathering an inventory of devices from families before the school year begins would streamline the process. We did not do this before the students arrived this year, so it took some time to determine who had phones, computers, and tablets (and how many!). It would also be helpful to have upperclass student leaders with good technology habits work with our ninth-graders to reinforce the benefits of getting off technology at night.

We are also in the process of surveying students and families about extending the program to 10th-graders and are exploring an opt-in option for upper grades. Although we want students to practice more self-regulation as they move through our program toward college, we also understand that devices and applications are intentionally designed by skilled technology experts and corporations to hook us, students and adults alike. Self-control in the face of these technologies may not always be possible simply because of the way human brains are wired.

In implementing the Tech Turn-in policy, we’re taking a proactive stance to support the health, focus, and academic success of our students. As we consider broadening this initiative, our goal remains the same: to foster an environment where our students can thrive, fully rested and ready to meet the challenges of each day. By prioritizing sleep and minimizing nightly screen time, we hope to foster self-awareness and instill habits that support students’ well-being and personal growth well beyond their time at the Academy. K

Trust, feedback, and care inform coaching strategies.

BY TUCKER PRUDDEN

O“We want our students to not just know what to do but also why it will help them.”

—TUCKER PRUDDEN Learning Specialist at the Gosselin Center for Teacher and Learning, Assistant Boys’ Varsity Lacrosse Coach

n any given weekend you can find teams dotting playing fields across America—from the smalltown baseball diamond to the high school lacrosse field to the highstakes action of an NFL stadium. All teams experience highs and lows, but one thing can really make a difference in a player’s growth: coaching.

Here at Kimball Union, we use KUA Design to inform our coaching practice. It’s an approach to learning that’s built upon positive relationships and uses brain science to design intentional challenges so students can grow and learn. It’s a model that has and will refine my coaching practice with the lacrosse team just as it does my role as a learning specialist in the Gosselin Center for Teaching and Learning.

So, what is good coaching? And can good coaches, like good teachers, be more intentional in designing these opportunities? Many already employ so many healthy educational strategies, but can these be named more clearly, cited specifically at critical moments, or verbalized when describing a drill. After all, we want our students to not just know what to do but also why it will help them.

Whether it is the high-five celebrating the shared success of a goal scored or an arm around a disappointed teammate after a loss, the relationship between members is critical to the growth of a team. A good coach will intentionally build relationships by the care they show student-athletes beyond the

boundaries of the playing field. It’s those moments that build trust and, as a result, create an optimal learning environment.

We start by putting incredible effort into connecting with students. After all, good relationships require effort to build and effort to maintain, particularly when that connection can be challenged through emotionally charged moments. In the dorm, I congratulate a student on a grade; I publicly applaud acts of community citizenship on the field; and I ask my daughter to say hello to students on the Quad. These connections make it easier to ask them to remove a hat in the dining

hall or take on a difficult matchup on the field. Instructional design coach Zaretta Hammond calls these practices “trust generators.” Let me tell you: They work.

Brain science tells us that good feedback is critical to growth. Sport is inherently a place where feedback is plentiful! It’s my role to use feedback in a timely, specific, and supportive way to make them stick. My goal is twofold, to show students there is a way for them to improve and that they can improve.

Research tells us this approach

increases feelings of control and self-efficacy, which are the foundation of learning motivation. Social psychologist Carol Dweck says that “constantly practicing and modeling a growth mindset is paramount to this model and the encouragement of progress over product allows for reflection and improvement.” Revisiting skills and drills in practice serves as a more obvious example of interleaving, and we introduce schemes through multiple modalities such as a whiteboard, film, walkthrough, and then live practice. My conversations promote resilience. At the end of a drill, I know I have achieved these goals when I blow the whistle and hear players say: “One more rep, Coach!”

My planning often starts by identifying skill-based growth opportunities—where to improve and what strengths to leverage. I then scaffold the use of those skills throughout a practice and during the course of a season. I encourage a student-athlete to use skills they are less proficient in when the stakes are low and offer additional suggestions to consider when they reach developmental thresholds.

Sport’s purpose, in our holistic educational model, is a place where students can experience lessons on the field that promote lessons for life. If we believe the experiences in sports serve to validate social-emotional, cognitive, and physical growth, then KUA Design is the ideal model for this work. K

“When it comes to knowing my brain, knowledge is power! Learning about neuroscience and how the brain works has made me realize that having a different brain isn’t a bad thing at all. All brains are different. Understanding just how my brain works has brought me more joy, and I love sharing what I know with others.”

ADI RUNGE ’25

“We are so fortunate to be involved in a school that has devoted extensive research and time in understanding the best ways to optimize learning for a teenage brain.”

JOELLA

LYKOURETZOS P’25 KUA Design Advisory Board

“I now know that strengthening my neural pathways through what my teachers call ‘effortful, spaced practice’ is the key to success in math and other classes. Learning requires meaningful work!”

—FITZ HAMNER ’25

“KUA Design is truly a student-centered, holistic model of education in action. It provides students with myriad and varied opportunities to gain knowledge and understanding of how our physical, mental, emotional, and essential selves operate as an integrated, whole system. KUA Design fosters the development of valuable, transferable, sustainable skills that support lifelong learning and overall health and well-being.”

JOSEPH DONARUM Psychology Teacher

“If I had had access to KUA Design back in the early 1990s when I started, I would have been able to target my development rather than thrash around in the dark using trial and error. Neuroscience gives us a common understanding and vocabulary of how learning happens so that we can be more effective teachers. Real magic happens when everyone is paddling in the same direction.”

SCRIBNER FAUVER World Languages Chair

“That we should be using efficient teaching methods should go without saying, but really putting an emphasis on neuroscience, on methods that have been shown to work based on how the brain is structured and how it functions, makes so much sense.”

URSI HERFORT Arts Teacher and Learning Center Teacher

➤ GREAT EDUCATORS THIRST

FOR THE KEYS TO UNLOCK EXCELLENCE AND PASSION IN EVERY LEARNER.

WE’VE

OBSERVED THAT THE DEEPER OUR EDUCATORS LEAN INTO KUA DESIGN, THE LARGER THEIR RINGS OF KEYS BECOME.