Creative Critical & Review

Working hard on a fourteen hour shift Relentless pressure to support my family, But the words I hear are ‘you’re taking our jobs.’

Will I ever belong?

Constantly learning to speak their tongue Language barriers every step of the way, But the words I hear are ‘you can’t understand us.’ Will I ever belong?

Paying my way to earn an honest wage Integrity and hard work remain my constant ethos, But the words I hear are ‘I bet he’s a thief.’

Will I ever belong?

No thanks for the clean floors and doors and windows Suspicion written all over their faces, The words I hear are ‘they’re all the same those terrorists.’

Will I ever belong?

Young wide eyes upon me at home The traumatic journey has brought us here, The words they must hear are ‘it’s getting better.’ Will they belong?

Food on the table and clothes on their frames Running water and soap despite our cramped conditions, The words they must hear are ‘we’re warm fed and and safe.’

Will they belong?

Smiles from school and an education developing Hard work continues to give my best for them, The words they must hear are ‘make the most of your childhood.’

Will they belong?

Friends arrive and say they’ll stay But in the end they all disappear. No matter what happens to me or you, We’ll always be strangers here.

I stood on the edge of the cliff, my pulse hammering, staring at the speck in the distance descending into nothing. I gathered my courage, and without looking back, stepped off the cliff. I hurtled down, the wind stinging my face, my heart hurting in my chest. As I fell, I thought to myself, ‘How have I got myself in this position? I’m going to die out here!’

It started when I started training for the police force. I was always a top-flight student, however that came with problems. I was always picked on by people who were envious of the instructors favouring me, especially one group of boys, who enjoyed the physical aspects, but couldn’t succeed at any of the strategic training. One day, after a particularly hard training session, the leader of the group, Joe Adams, decided he couldn’t take the training anymore, and attempted to run away. He was, of course, caught at the camp boundary, and taken back in and he was thoroughly scolded. I tried to have as little to do with them as possible, but occasionally our lessons would overlap, and they would use the opportunity to tease and gossip about me like teenagers. At the end of a parachute session, Joe took my watch, which I had left at the side of the gym, and started running off with it. The watch was from my late mother, a family heirloom, and I couldn’t let him just run off with it. I chased him, and even when he ran out of the compound I kept chasing him. I kept chasing him, until finally he was blocked by a cliff. He waited until I was about fifty metres away from him, and with a wry grin on his face, dropped the watch off the edge of the cliff. I saw the sunlight glint off the clock face, and then, to my horror, it hurtled down into the ravine.

As Joe strolled off, a smug grin on his face, I sprinted to the cliff edge, and watched my last reminder of my mother hurtle into the distance. I stood on the edge of the cliff, my pulse hammering, staring at the speck in the distance descending into nothing. I gathered my courage, and without looking back, stepped off the cliff. I hurtled down, the wind stinging my face, my heart hurting in my chest. I gained speed, and gradually the speck in the distance got bigger and bigger. When the watch was just a couple of metres away from me, I snatched it out of the air, pulled my parachute cord, and felt the parachute unravel and tug me upwards. I slowly guided myself down to the ground, and when I finally reached the surface, I fell onto my back, breathing heavily, my heart still hammering.

However, it was not over yet. I was trapped at the bottom of a ravine, and the only way out was the way I had come down; climbing up the cliff. We used this particular section of the cliff face for climbing practice, but never without ropes and proper equipment. I had never made it up this wall without falling off at least once, but now I didn’t have a choice. I waited for my pulse to settle, and then set off up the cliff face. I gradually ascended up the cliff, putting one hand above the other, and one foot above the other. When I was about fifty metres up, I dared a glance down, and I felt a wave of nausea reach over me. But I kept climbing, and refused to stop, until I was twenty metres from the top. Here, there was a slight ledge, and I allowed myself to lean against the cliff for half a minute to recover some energy. I kept climbing, but the first move after my rest, I placed my foot on a loose rock, and it slipped off, leaving me dangling from my already tired arms. I hung on, and the pure terror in me was the only thing keeping me from falling. I scrambled around with my feet, desperately looking for a place to wedge one of them, until finally, to my great relief, I found a lip on the rock face, and I placed both my feet on it. However, I could not rest, I had to keep on moving. And so, I gradually made my way to the top of the cliff, hauled myself onto solid ground, and lay there, trembling. It was that day that I vowed to myself never to climb without a rope again.

A total of 340,000 people per year in the UK have to deal with being blind or partially sighted (Macular Society 2018, NHS 2022). This is an extremely difficult way to live, with increased living costs and precautions unavoidably affecting everyday life. Conditions that affect the lens such as cataract are relatively straight forward to treat surgically. Therefore, this means that the most common causes of permanent visual loss are due to retinal diseases such as age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma (World Health Organisation 2021). If the eye has irreversibly lost its function, one possibility would be to consider an ocular transplant. However, the eye is a delicate organ, and is connected to the brain via the optic nerve and this plays the crucial role in transmitting visual information to the visual cortex of the brain. The visual cortex is an area of the cerebral cortex, situated at the back of the brain, that receives and processes visual information. If the optic nerve is severed, is it almost impossible to reconnect due to the sheer number of nerve fibres that it is composed of making transplant an unlikely treatment of the near future (Turbert 2022, Rao, Stern et al. 2021, Discovery Eye Foundation 2015). Another, more feasible solution may be to try and repair the damaged retina. This would require an artificially engineered retina which could be inserted it into the eye, however, this would require a close match of cell tissue types to avoid tissue rejection. Therefore, using a generic stock of retinal cells may be unlikely to be successful. To overcome this challenge would require the technique to use cells from the patient. These would need to be able to develop into retinal cells in the test tube. However, to date it is unclear whether retinal cells differentiated in this way from adult cells would form physiologically relevant structures compatible with the normal retina.

Normal retinal development in a human embryo begins with the formation of an optic disc at around 16 weeks gestation through a process called vasculogenesis (Cook 2016). Vasculogenesis is the differentiation of angioblasts into endothelial cells and the formation of a primitive vascular network which will come to form the retinal blood network. Retina formation finishes at around 40 weeks. An article recently published by the New Scientist claimed that scientists successfully achieved artificial development of photoreceptive optic cups, showing rudimentary eye development from induced pluripotent stem cell(iPSC)-derived brain organoids in a test tube, which may make retinal replacement treatment of blindness a real possibility (Wilson 2021).

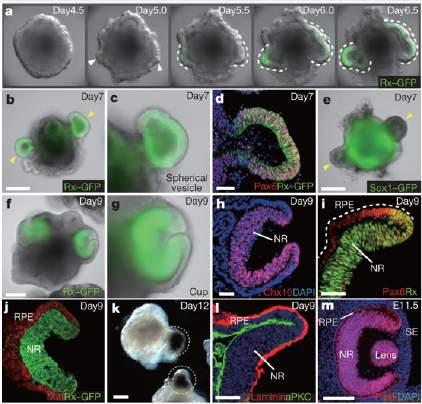

Previously, it was not known whether Optic cups could undergo ‘self-formation’, or whether they required specific external conditions or structures. Eiraku et al. (2011) developed a cell culture model using mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells, which showed the ability to become retinal cells (Eiraku, Takata et al. 2011). They confirmed that their cell culture model was representative of the retina by looking for expression of a key gene (Rx) which acts as a hallmark of retinal development. The development of the ES mouse optic cup (Fig. 1h) closely mirrored the normal mouse eye structure and gene expression (Fig. 1m), and was found to be intrinsically controlled without the requirement for external factors (Fig. 2).

Figure 1 Self-Formation of optic-cup-like structure in 3D culture of ES cell aggregates (Eriaku et al., 2011).

To determine whether the Rx gene was expressed in the ES cells, they inserted a reporter gene which produced a green fluorescent protein (GFP) when the cells were making Rx (Fig. 1a). These Rx expressing cells could then be visualised with fluorescent microscopy because of their green colour. By modifying the culture medium for the ES cells and by adding a basement membrane-matrix, they improved the efficiency of retinal induction (around 80% were strongly positive for Rx-GFP+ expression).

Finally, the team showed that the optic cups developed in their model are potentially photoreceptive through demonstration of expression of the appropriate components required for response to light stimulus.

Overall, this study revealed that in an in vitro model, retina development arises through cell differentiation with an intrinsic order, involving self-patterning. Once formed, the model is potentially capable of responding to a light stimulus. This work shows that in vitro differentiation of a functional retina is theoretically possible, and therefore supports the possibility that in the future, therapy to replace damaged retina caused by retinal disorders could be a feasible treatment for loss of vision.

The study that sparked the news story built upon the work by Eiraku et al. aimed to fully regenerate ocular components in vitro. This group aimed to determine whether whole eyes could be grown in vitro (Gabriel, Albanna et al. 2021). Similar to the previous paper, the starting point would need to be stem cells because of the variety of eye cells making up the various components of the eye. Rather than utilising ES cells (which are relatively hard to isolate and only found in embryos), this team set out to determine if it was possible to develop complete ocular differentiation from inducible pluripotential stem cells (iPCS) derived from humans. iPSCs’ were developed following the discovery that by inserting genes from primary embryonic stem cells into mature cells, the mature cells could reverse their epigenome (Carey 2012), allowing dedifferentiation into stem cells (induced pluripotency) (Takahashi and Yamanaka 2006). These pluripotential stem cells can then differentiate into any cell in the body (under the correct conditions). This has the significant advantage of being much more feasible in a human therapy because, mature cells from blood or skin are easy to obtain and can be transformed into iPSCs. In this work, retinal development was stimulated through the addition of retinol acetate ranging from 0–120 nM to the iPSC culture medium, because retinoic acid is critical to eye development. This led to development of organoids and subsequently into more complex structures. The team noted that the organoid structure resembled what appeared to be primitive eye development.

Celia Brabazon

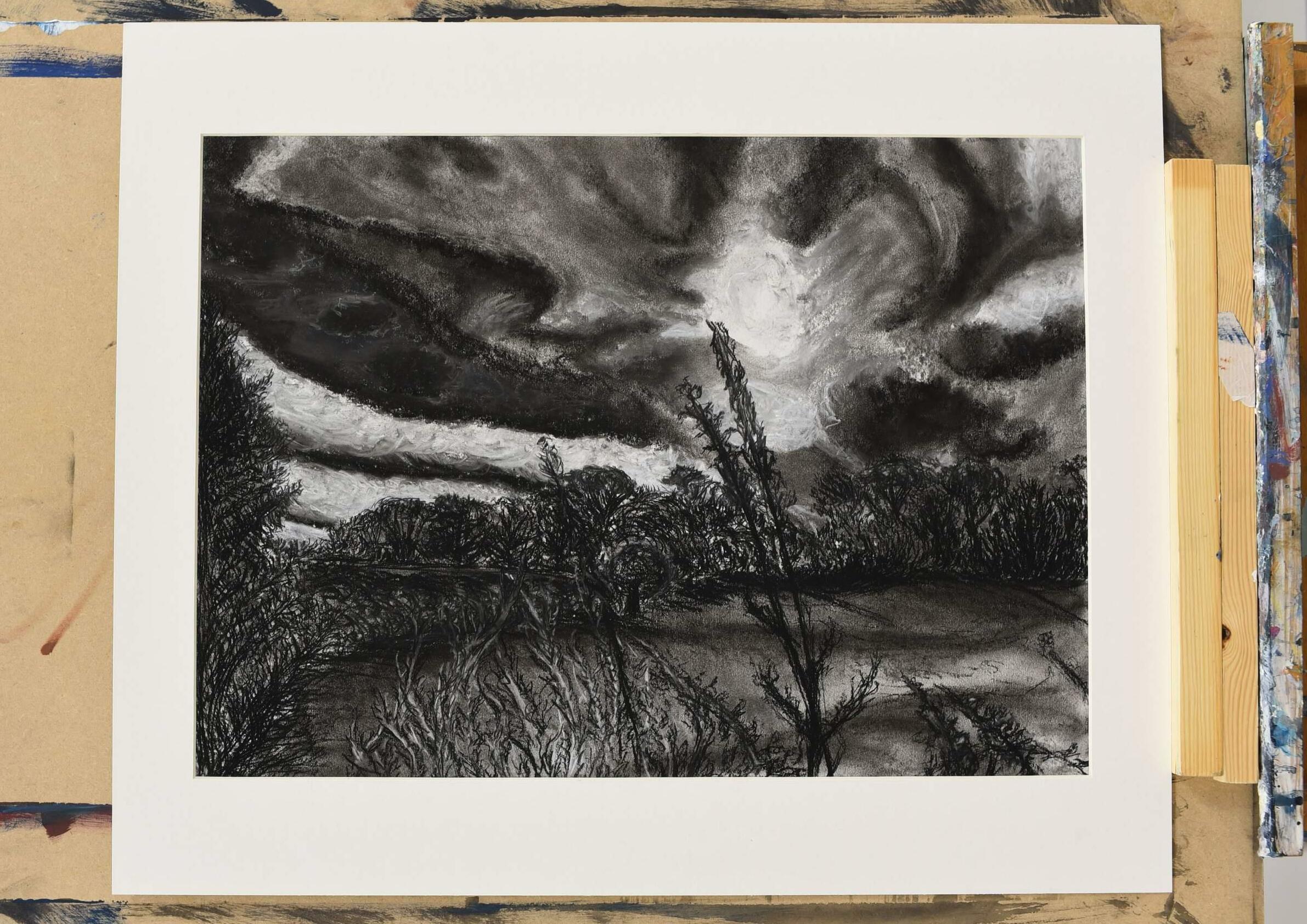

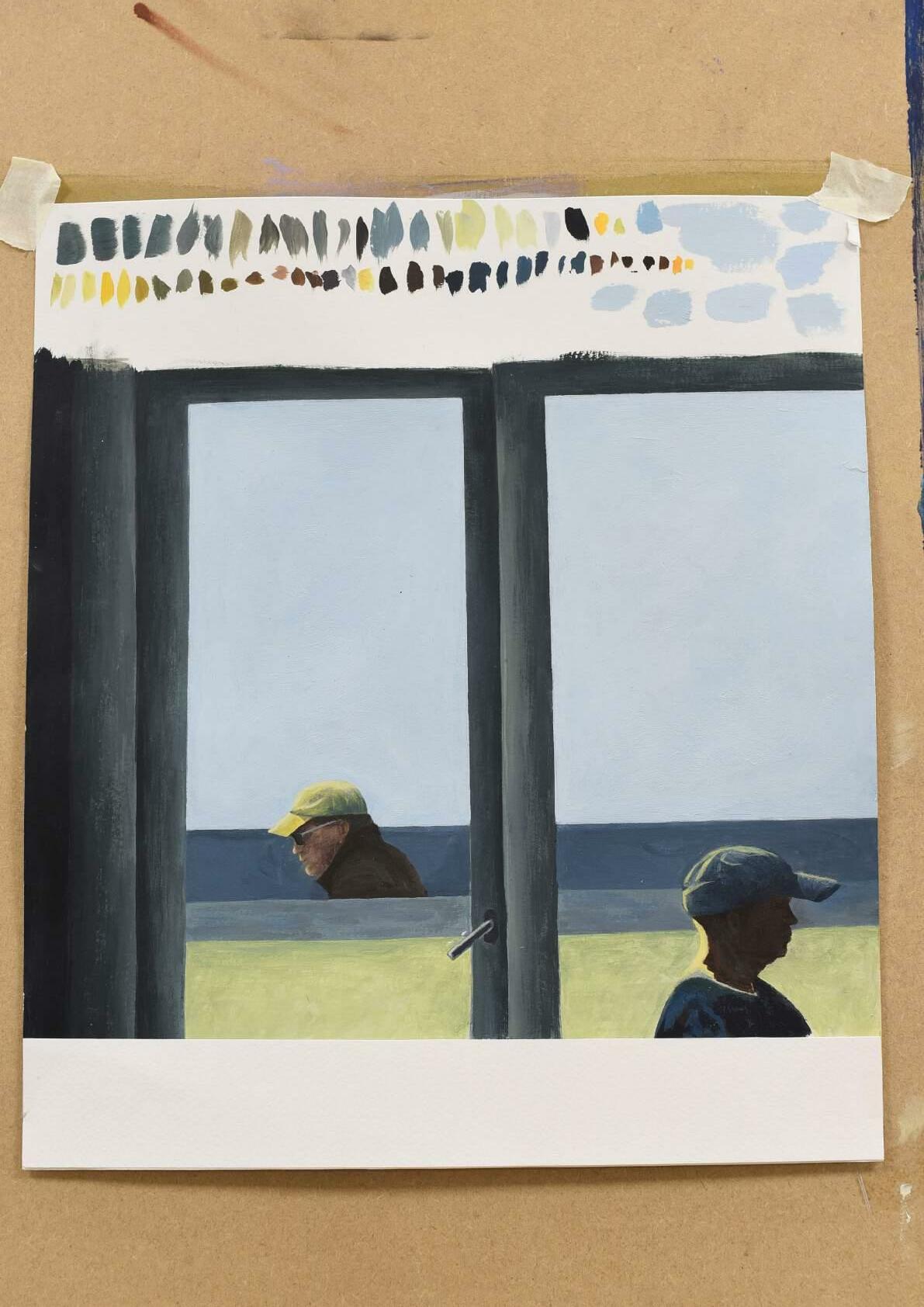

Upper School - Art

Celia Brabazon

Upper School - Art

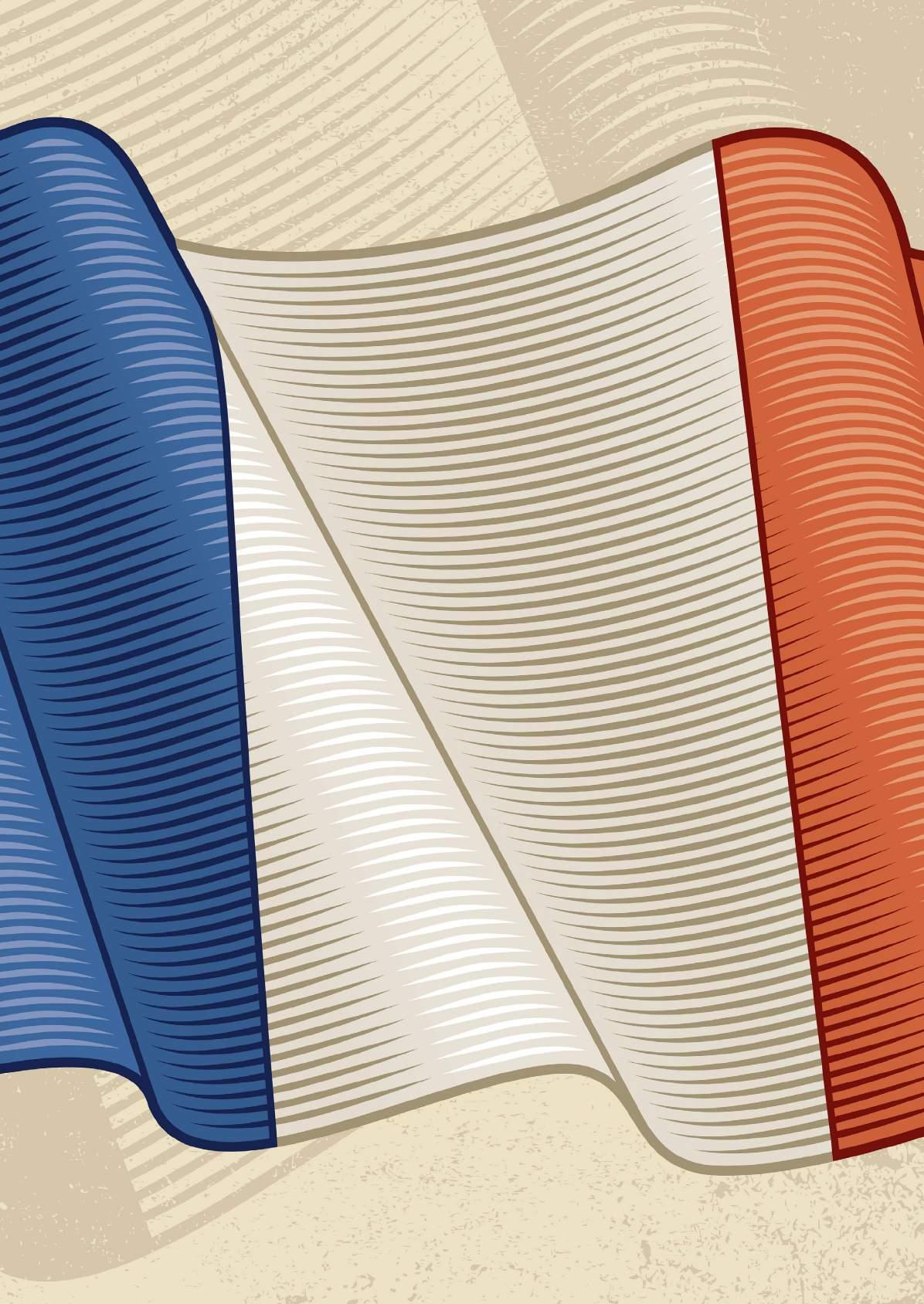

In the Spring and Summer terms of the Lower VI, our French students study the film La Haine (Hate). The film by Matthieu Kassovitz was released in 1995 and details a day in the life of three young men from a housing estate in suburban Paris. The film aims to highlight themes of social exclusion, racism and police brutality and it provides our students with a different picture of modern France and contemporary urban French society and the challenges they face. In this essay Emma Aellen analyses the similarities and differences between the three main characters in the film. This essay was completed under timed conditions and is a superb example of the linguistic level that our A-level students can reach. It also shows a great depth of insight and perception regarding the film and the issues that it raises.

La plupart du film ‘La Haine’ attarde sur ces trois personnages clés - Vinz, Saïd et Hubert alors l’audience a plein de temps pour apprendre sur leurs tempéraments et pour essayer de comprendre leurs actions. Tous les caractères dans le trio offrent les qualités et les opinions différentes et quelque chose d’unique. Ensemble, ils incarnent parfaitement les thèmes et l’environnement que Kassovitz voulait nous montrer.

Bien qu’ils semblent être très proches, les trois amis ne sont pas les mêmes. Ils ont bien sûr des origines différentes, Vinz est blanc et juif, Saïd est maghrébin et Hubert est noir d’origine africaine. Ils représentent alors le nouveau drapeau de la France : black, blanc, beur. Peut-être Kassovitz veut que l’audience apprécie la diversité d’une France moderne, en voyant les relations amicales entre ces personnes, qui viennent de races différentes. Cependant, on pourrait dire que ce trio n’est pas réaliste et qu’en réalité ces trois groupes seraient plus divisés. Cet argument semble être même plus raisonnable lorsqu’on considère les tempéraments et les motivations contrastés de Vinz, Saïd et Hubert. Vinz est le personnage du trio le plus fâché et violent pour la plupart du film. Il incarne l’esprit et l’agression des banlieues et ce comportement est un choix ; il veut que les autres le voient comme un caïd. Il dit à Saïd et Hubert ‘Si Abdel passe, je tuerai un keuf.’

De l’autre côté, Hubert semble être toujours calme et sérieux. Il ne veut pas faire partie de la violence des banlieues comme Vinz, il a des ambitions plus grandes. Il dit à sa mère ‘j’en ai marre de la cité, j’en ai marre, il faut que je parte d’ici.’ A la fin du film c’est Hubert qui convainc Vinz de laisser partir le skin et d’abandonner la violence. Il est en fait pacifiste pour la plupart du film. Saïd est en général un personnage plus drôle et moins sérieux que les autres. Son rôle de blagueur et de rigolo reste toutefois important ; il est nécessaire pour réduire l’intensité du film. Par exemple, la scène dans laquelle Vinz coiffe les cheveux de Saïd. Cette scène montre aussi que, même s’ils se disputent souvent les amis peuvent s’amuser ensemble ; il y a une unité qui les réunit, même après une dispute. Par exemple, quand Saïd et Hubert voient Vinz encore une fois à la gare. Ils l’acceptent de nouveau sans dire un mot de criticisme. Kassovitz semble vouloir montrer que les similarités et les différences entre Vinz, Saïd et Hubert sont plus significatifs pour eux que leurs différences. Même si leurs origines et tempéraments rendent leurs relations difficiles quelquefois leurs identités comme des banlieusards est la chose la plus importante. Le meilleur exemple d’une scène dans laquelle ils sont tous unifiés est la scène avec la journaliste. Les jeunes lancent tous des objets à sa voiture. Ce moment nous montre que le trio partage la même fierté et l’importance de leurs identités comme des banlieusards.

A la fin du film il y a une autre scène très émouvante qui montre la même chose. Hubert convainc Vinz de laisser partir le skin et ils se réconcilient. Ceci montre que, malgré leurs tempéraments variables, Hubert et Vinz ne sont pas des tueurs. Les trois personnages sont différents mais ils partagent le même désir d’échapper à l’engrenage de violence dans lequel ils sont coincés. Leurs approches aussi sont variables, Vinz veut se battre agressivement contre les policiers qui, selon lui, les oppriment. Hubert veut quitter la banlieue, en travaillant dur pour trouver un meilleur environnement. Saïd échappe en s’amusant, et avec l’humeur. Ensemble ils donnent l’audience un message important pour ce film ; personne ne peut échapper à la haine.

Improved scientific understanding into cancer biology has helped reveal the mechanisms by which our immune system distinguishes between normal cells versus cancer cells and what specifically goes wrong in the tumour microenvironment to allow cancer cells to evade detection. Scientists have used these conceptual gains in immunological anomalies to ‘upskill’ our own immune systems to combat cancer by developing new ‘immuno’ therapies. This project evaluates the extent to which these new immunotherapies are being used in the ongoing fight against cancer by evaluating the comparative pivotal clinical trial data between chemotherapies and immunotherapies and discussing how this has translated into clinical practice. It is concluded that whilst chemotherapy remains a mainstay in cancer therapy across a wide range of cancers, the wider implications of the developing Immunotherapy drugs show a positive future for cancer sufferers. This treatment modality has and will continue to revolutionise the field of cancer therapy with significant advancements in several cancers such as prostate, melanoma skin cancers and breast cancer.

Immunotherapy is emerging as one of the most promising new treatments against several forms of cancer. Even though the principles of immunotherapy were described in the 1890’s, conceptual gains in cell biology, biotechnology and their application in the ongoing fight against cancer has only materialised in the last 10 years. These conceptual gains are steadily being converted into improvements in cancer diagnosis and treatment, with notable progress towards personalised cancer medicine. Traditional chemotherapy carries significant side effects that can limit use. Immunotherapy emerges as a potential adjuvant therapy that may help improve cancer outcomes for patients.

Looking into cancer cell formation and how the immune system fails to detect and attack these cells combines two of my favourite topics in biology: the immune system and cell theory. My interest in immunotherapy was further sparked by reading an article from 2018, about American immunologist James P. Allison and Japanese immunologist Tasuku Honjo who received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of cancer therapy by inhibition of negative immune regulation. I was intrigued to learn more about this exciting development. More recently, I read a BBC health article outlining the positive impact of immunotherapy on head and neck cancer. The article outlined how a new immunotherapy treatment called Pembrolizumab had a dramatically positive effect on a patient’s long-term survival which motivated me to extend by knowledge and understanding of this fascinating area. According to Cancer Research UK, someone in the UK is diagnosed with cancer every two minutes. Cancer is a condition that touches all of us either directly, via loved ones, or friends. Collectively, these aspects motivated me to complete this project. I hope the project will help me to develop research skills and deepen my knowledge of cancer treatments, time management, scientific essay writing and presentation skills.

In this project, I intend to research why our immune system fails to detect and attack cancer cells, how immunology is being used by medical researchers to ‘upskill’ our natural immunity and I will evaluate the pros, cons and extent to which immunotherapies contribute to the fight against cancer in comparison to chemotherapy. By undertaking this project, I hope to achieve a better understanding of this area for my own personal interest.

“Tumours, or neoplasms (from Greek neo, “new”, and plasma, “formation”), are abnormal growths of cells arising from malfunctions in the regulatory mechanisms that oversee the cells’ growth and development. These abnormal cells can grow beyond their usual boundaries, invading adjoining parts of the body and spreading to other organs. This latter process is referred to as metastases. However, only some types of tumours threaten health and life. With few exceptions, that distinction underlies their division into two major categories: malignant or benign.”

Cancer is a major burden of disease worldwide, accounting for nearly 10 million deaths in 2020, with a considerable impact on society. Cancer remains the seconding leading cause of death in the world. In the 21st century, cancer has become the number one cause of death in developed countries. The most common causes of cancer death in 2020 were :

● Lung (1.80 million deaths)

● Colon and rectum (935,000 deaths)

● Liver (830,00 deaths)

● Stomach (769,000 deaths)

● Breast (685,000 deaths)

Within the UK, there are over 367,000 new cancer cases every year and over 166,000 deaths, with prostate, breast, lung, and bowel cancers collectively accounting for more than half (53%) of all new cancer cases in 2020. Only half (50%) of people diagnosed with cancer in England and Wales survive their disease for ten years or more (2010-11) and 38% of cases are preventable in the UK as of 2015.

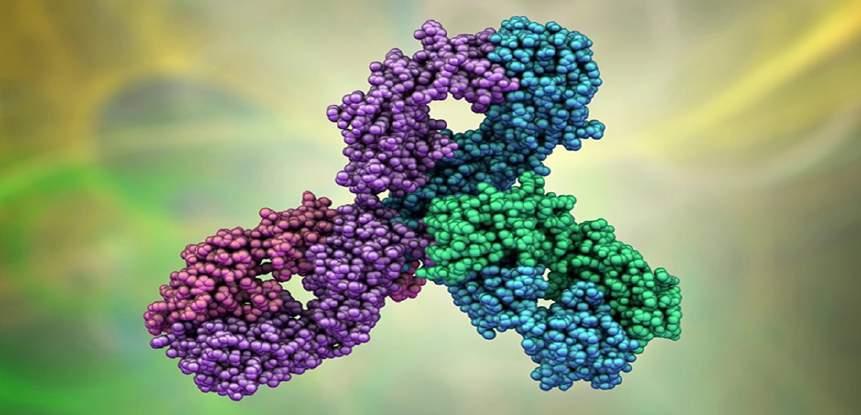

Upskilling immune cells – to what extent will immunotherapy replace chemotherapy in the treatment of cancer?Image: Pembrolizumab monoclonal antibody drug protein. Immune checkpoint inhibitor targeting PD-1, used in the treatment of head and neck cancer https:// www.123rf.com/photo_78432778_Pembrolizumab-monoclonal-antibody-drug-protein-immune-checkpoint-inhibitor-targetting-pd-1-used-in-t.html

This project reviews the extent to which design flaws in RBMK nuclear reactor design caused the Chernobyl disaster of 1986. The other factor considered is human errorany mistakes made after the design of the reactor which contributed towards the accident.

Sources look at the direct causes of the accident, and the physics behind it, as well as culture within the Soviet nuclear industry which could have contributed to the accident. They consist of: - accident reports, first-hand accounts, academic papers, an interview with an expert, websites, videos and books.

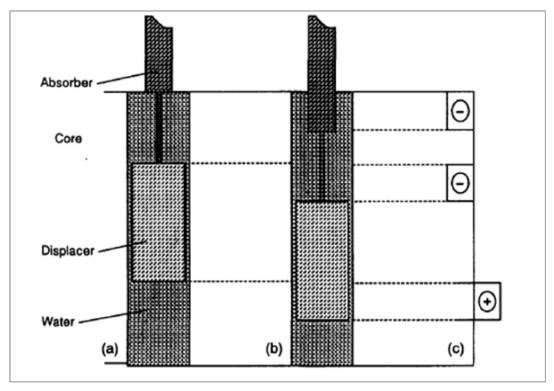

The first part of the discussion examines the RBMK reactor, how a graphite moderated reactor works and its specific flaws which contributed towards the accident- the design of the control rods, a badly displayed operational reactivity, complex void and power coefficients which were exaggerated at a low power level.

The second part consists of analysing the role human error played in the Chernobyl accident. This is divided into two seconds: firstly, longer term human error which increased the likelihood of an accident of this seriousness occurring e.g., ignoring safety recommendations and the inability to learn from past experiences. Secondly, mistakes made by the operators which contributed to the accident.

This project concludes that RBMK reactor design was deeply flawed in many major ways which culminated in the accident at Chernobyl. The ultimate blame therefore must be put on the design. However, the accident was not inevitable. The Soviet nuclear industry was unable to learn from its previous experiences, safety fears expressed by engineers and scientists were not acted upon. This culture within the Soviet bloc meant that a flawed design was not fixed, and although the danger of RBMK reactors was known they remained in operation. This aspect of human error played an instrumental role in causing the accident. Mistakes made by the reactor operators are deemed to be less important in the outcome of the accident- although rules were undoubtedly broken, they influenced the accident less than the other factors.

When choosing a topic for my EPQ I knew I wanted it to have an engineering base. This is the area I want to study in my higher education, and I have an interest in. Interest in the subject area was crucial in my motivation to complete the project on-top of my existing academic commitments. My interest in the Chernobyl accident began by watching the Sky/HBO miniseries Chernobyl in August of 2020. Despite being incredible in its cinematography and the effects of the accident on the people who experienced it, I felt underwhelmed by how it explained the engineering behind the accident. When starting my EPQ the next year Chernobyl was an area I wanted to research further.

Reading the book To Engineer is Human by Henry Petroski , which explains Civil engineering failures, factors behind accidents and how engineers learn from disasters gave me an interest in accident analysis; How did the accident happen? Which factors played a role? Why was the accident not prevented? When choosing a topic for my EPQ combining my fascination, but limited understanding, of the Chernobyl accident and my interest in engineering disasters meant that analysing the factors behind the Chernobyl accident was suitable. To give my project an engineering foundation I centred it around flaws in the design of the reactor.

Chernobyl is an infamous nuclear disaster and has shaped opinions around the world on nuclear power- being the only commercial nuclear power disaster to cause fatalities from acute radiation syndrome . In addition to this many historians consider Chernobyl to have, whilst not directly caused, triggered the collapse of the Soviet Union . This demonstrates its importance within a wider context and how it has had profound effect on global geopolitics influencing the downfall of the USSR.

This dissertation will evaluate the factors which caused the Chernobyl accident and attempt to draw a conclusion as to who/what is ultimately to blame for the disaster.

The events which led to the accident at Chernobyl nuclear power station, reactor No.4 have been analysed internationally for over 35 years. Due to the nature of the accident and its dangerous consequences multiple reports and re-reports have been published analysing its causes and who is accountable for it.

However, despite being the world’s worst nuclear disaster, I was surprised by how little literature there is on the engineering behind the disaster, especially in book form. Many sources on the subject tend to focus on the effects and consequences of Chernobyl; the evacuation, health, political repercussions etc, and not on the engineering and the responsibilities behind the accident. Many sources place the blame on the Soviet nuclear industry as a whole, this does not help answer my question. I want to know what it was within the Soviet nuclear industry that caused the accidentto what extent it was the design of the RBMK reactor.

The first stage of my research consisted of reading books around the topic, getting a feeling for the event and understanding the basics. The main body of my research consisted of academia and accident reports, both official and unofficial. For my in depth research I avoided newspapers, YouTube and other videos/articles/books not written by people with an in-depth knowledge of the subject, as inaccurate information surrounding this event is commonplace. To answer the question proposed in the project

I needed to gain an in-depth understanding of how RBMK reactors work, and books/videos which are often written for laypeople are simply inadequate for this. My research consisted of a blend of opinionated work and purely informative sources.

To what extent can RBMK

be blamed for the 1986 Chernobyl disaster

In the last few decades, China has transformed into a global superpower and has become an increasingly influential power. Since China’s opening to the world in the late 1970s and there being a wave of Chinese emigration, this has led to an influx of new information about China, including China’s Cultural Revolution. The Cultural Revolution is a fascinating period not only because it has stimulated so much debate, but because of how it has impacted China. It is often argued that without the Cultural Revolution taking place, China would not have transformed to the extent that it has since the need for drastic change would not have been necessary. Additionally, what is often surprising about the Cultural Revolution, is that despite the atrocities that took place and the number of deaths caused from this, the communist party and Mao’s legacy has been able to live on. This has led me to wonder how far the youth were affected during the Cultural Revolution since many of those part of that generation are the leading ministers of China today, including Presdient Xi Jinping who is actively preserving Mao Zedong’s legacy. Therefore, it is these reasons which initially influenced me to base my dissertation around the Cultural Revolution and how far Mao succeeded in manipulating the youth.

Besides my personal interest in this topic, I believe that this dissertation will serve a wider relevance. Today, the youth of China are being subjected to similar conditions to the youth of the Cultural Revolution. President Xi Jinping wants children and students not just to obey, but to love the Communist Party. For example, at the 2019 conference organised to mark the 100th anniversary of the student-led anti-imperialist May Fourth Movement, Jinping said “We need to … strengthen political guidance for young people, guide them to voluntarily insist on the Party’s leadership, to listen to the Party and follow the Party.”1This explains why indoctrination, censorship and surveillance have been carried out and imposed on the education system in order to manipulate the youth into following the communist values. However, analysing how the youth were affected during the Cultural Revolution could indicate how far Xi Jinping, and other totalitarian leaders, can succeed in revolutionising an entire generation. Therefore, this is why I am investigating to what extent Mao succeeded in manipulating the youth during the Cultural Revolution since it could help answer broader questions such as how far totalitarian leaders can ultimately change human nature and one’s moral compass.

Before I begin my discussion, it is worth clarifying some of the key terms. Firstly, in my dissertation, I have left the term ‘youth’ to mean anyone who was of age to become a Red Guard during the Cultural Revolution. This tended to be between the ages of 13 and 25. Additionally, I have periodised the Cultural Revolution to be between the years 1966 and 1969. The periodisation of the Cultural Revolution often varies amongst historians. The Chinese Communist Party have recognised the year 1976 to mark the official end of the Cultural Revolution since this was the year of Mao’s death. However, some historians have argued that the year 1969 should be seen as the end of the Cultural Revolution as this was when all rebel organisations were dissolved and the period of social upheaval from the grassroots finally ended. To make my dissertation more narrow in focus, I decided to go with the periodisation of 1966-69. Since I am focusing more on the youth, it also makes more sense to go with this periodisation since the youth of the 1970s would be of a different generation from the youth of the 1960s cohort.

As an aspiring Historian, I hope that this project will greatly improve my research skills and in learning how to express my opinions in such a way that shows validity and strength in an academic argument.

To what extent did Mao Zedong succeed in manipulating the youth during the Cultural Revolution?

In this project I will look into how genetics can contribute to an individual becoming a fallacious and misconceived, but equally fascinating, type of character - a psychopath.

To determine how these biological factors are conducive to the disorder, I will explore one specific gene, the MAOA gene, how low variants of it may arise and the effects these have on dopamine in the brain, as this neurotransmitter can explain many symptoms associated with antisocial personality disorder. Additionally, in my literature review, I will explain how an individual can be tested for having a deficiency of this particular gene, and why this can be useful to them.

My discussion is where I will debate the extent to which the MAOA gene really is an explanation for psychopathy, by exploring other factors which interact with the gene, such as environmental stressors including childhood trauma and substance abuse, leading to its methylation.

Furthermore, I will discuss other genes which have been shown to correlate with psychopathic behaviour, such as the COMT gene, as this will show that there is not just one biological component giving rise to aggressive and impulsive actions.

The conclusion I will reach in this project is that whilst the MAOA gene does play a part in the development of psychopathic behaviour, this factor becomes small and almost negligible when the bigger picture is looked at. The gene interacts with many other elements, and there are also aspects of behaviour that have no relevance to this component at all, so the extent to which it contributes is fairly trivial.

Psychopathy, or more accurately, Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD), is one of the most widely researched mental health disorders there is. It encompasses countless unusual behaviours and is often used as an umbrella term for many other less known or less common cognitive irregularities, such as sociopathy or dyssocial personality disorder.

In this dissertation I am going to explore a scientific explanation for behaviour associated with ASPD, by looking at one gene called monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) that can have a profound effect on the brain and behaviour when in a low-activity form.

In the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition), this disorder is described by an extreme lack of empathy and remorse, immoral judgements and actions, aggressive and impulsive behaviour as well as egocentricity. It lists specific criteria for diagnosis of the disorder in addition to these symptoms, one of them being that the antisocial behaviour does not occur in the context of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

These criteria are there because having one or even several of the aforementioned symptoms does not make an individual a psychopath, or mean they have ASPD. For example, someone may have a lack of ability to connect with others and form relationships, however this would not be enough to diagnose them - in fact, many people with ASPD are charming, charismatic and have the ability to analyse others and easily gain their sympathy and attention.

The word ‘psychopath’, to the majority of people, would probably conjure up a lot of negative connotations and impressions. It is a word that is often thrown around, with no real meaning, and seems to spark intrigue despite its unfavourable implications, but not many people understand the causes and the complexity of this disorder.

My aim in this project is to break down and understand in detail one of the factors possibly contributing to behaviour associated with ASPD, called the MAOA gene. This is a biological, genetic influence which is not often considered when looking at causes of psychopathic behaviour, hence my desire to explore it. Understanding as many factors as possible which are conducive to mental health disorders is the first step to providing help for affected individuals, especially factors which are not easily identified just by speaking to someone, or looking at events in their lives.

By investigating a fascinating scientific point of view, I hope to not only expand my own knowledge on this condition, but to also encourage others to focus on the causes and explanations for it rather than the immoral behaviour, as this is the most effective way to understand and consequently develop support for those affected.

Of course, as aforementioned, ASPD is an extremely complex disorder, and there is rarely one sole cause. One abnormal gene in an individual’s DNA is unlikely to be the root of a plethora of antisocial characteristics, but it can certainly contribute.

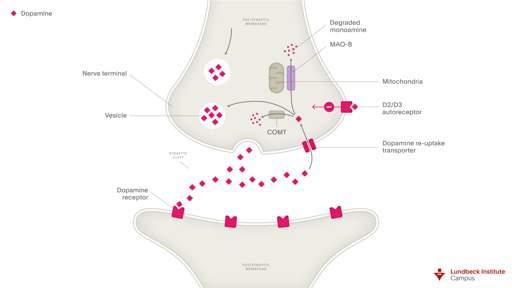

Before looking into the regular function of the MAOA gene, it is important to first understand dopamine, and how it works.

Dopamine is a fairly well known neurotransmitter which sends signals from the body to the brain, and between nerve cells, triggered by an action potential. This is an electric charge which travels down the axon of the presynaptic neuron, which is the neuron carrying signals towards the synaptic cleft. This action potential triggers calcium ion channels to open and the ions diffuse into the presynaptic membrane. When it reaches the terminal at the end of the neuron, vesicles containing neurotransmitters, in this case dopamine, fuse with the membrane and release their contents by exocytosis, which diffuse across the synaptic gap, into receptors on dendrites (branches of a neuron that receive communications from other cells ) of the postsynaptic neuron. Here the dopamine is converted back into an electrical impulse and the process of transmission begins again, and continues from this neuron to the next. This whole process can be seen in figure 1 .

Figure 1 - Synaptic Dopamine Reuptake and Degradation

This project investigates the impact of menstrual stigma on adolescent girls through two avenues: the physical management and mental burden of menstruation. The data, primarily from India, Bangladesh and Kenya, showed that most girls from low income households in developing countries could not afford sanitary pads and were forced to use old cloths. This meant the girls would be in great discomfort and increase anxiety about showing blood in public. It was evident from the research that there were great gaps in knowledge about menstruation and misconceptions about the cause of menstruation were prevalent. These misconceptions led to socially ostracising menstruating girls. Some studies found that menstruating girls were restricted from life and social interactions, while other studies found there was associated sexual and domestic abuse associated with menarche. The project found that the mental burden of keeping menstruation a secret and discomfort from the injuries caused by stiff materials that should not be used to absorb menstrual bleeding would disrupt the ability of the girls to succeed academically. This lack of opportunity would contribute to girls being unable to rise from their socio-economic position.

Everyday there are more than 800 million people menstruating and yet the experience of menstruation as an adolescent is mentally and physically distressing. The physical symptoms of menstruation such as cramps are widely minimised and girls are deemed as overdramatic, weak or attention seeking. In developing countries, this is exacerbated by the prevalence of cultural beliefs in place of education. The project focuses on how menstrual stigma is destructive to the lives of adolescent girls. The reason stigma is the key theme of the project is that the taboo nature of the topic is part of what allows the oppression to continue. The lack of access to facilities or to the appropriate products stems from the view that menstruation is not a basic need. Menstrual products are not deemed as a basic necessity by the policy makers and therefore the default in developing countries is not to have access to sanitary products. The stigmatisation of menstruation causes the ostracization of adolescent girls as they are punished for bleeding. This project is based on exploring how menstrual poverty creates a capability poverty trap for adolescent girls. A capability poverty trap describes how splitting one’s focus on various different problems in life can reduce your ability to excel at any of them. Adolescent girls have the mental burden of keeping menstruation secret and simultaneously have to live with the physical pains of menstruation that are only exacerbated by their inadequate conditions. They are trapped by the demands and burden of managing menstruation which consumes their mental capacity. These additional stresses distract from academic performance and social interactions and therefore remove opportunities. The continuous disruption permanently disadvantages the girls leading to a greater drop-out rate and worse academic performance in the end. This topic is infrequently discussed in the media or considered in conversations about global poverty. The opportunity cost of menstruation for adolescent girls places them in a poverty trap yet this is rarely factored into economic models to decrease inequality. My aim in this project is to highlight the importance of menstruation in a girl’s life and how being complacent in addressing the stigma surrounding it is detrimental to the lives of adolescent girls.

My route into this particular topic stemmed from two experiences. Last winter, I had done a course on global inequality and the circumstances which create global poverty by making it extremely difficult to get out of poverty once plunged into it. On a more personal level, I had grown increasingly frustrated at the cost and waste my menstrual products were creating and I had experienced many menstrual related health problems myself so I turned to reusable alternatives. I began doing a lot of research into the menstrual products on the market. I had come across a menstrual cup made of an anti-microbial material meaning it could remain hygienic without being sterilised by boiling water. It was being distributed to girls in areas of limited water access creating a sustainable, cheaper alternative to pads and other products for the girls and seriously improving their lives. In future, I would like to have a career in development economics and working towards a more equal world in future. However, the systematic oppression of girls and women in the world is contributing to additional hurdles to gain the same opportunities as male counterparts. It is widely acknowledged that there are gender pay gaps and increasingly government policies are trying to reduce the effects of motherhood on career progress. Such an effort to reduce menstrual poverty is not so widely publicised and by most not even thought about. I will begin by doing a source by source evaluation of the literature I based this project on. This will outline the methodology of data collection and the reliability of it which is integral to the discussion of the findings. The discussion will first consider the physical constraints of menstruation of adolescent girls. The limited access to proper facilities or clean access in addition to the struggle to buy sanitary pads. This will cover the effects of using inappropriate absorbents on girls’ lives and the measures they must resort to in order to afford the available products. The second half of the discussion will look at the impacts of social perceptions and misunderstanding of menstruation. This focuses more on the mental burden of menstruation and the need for secrecy. This will be followed by the conclusion in which the physical and mental experience of menstruation will be considered together with solutions proposed by the studies.

Figure 1. A graphical representation of income growth illustrating the S shape curve.

Developmental economists Professor Duflo and Abjihit wrote this book to describe the ways in which poverty traps do not allow for growth from the global poor. The concept of poverty traps utilises an S shape curve intersecting a 45-degree line from the origin to model the difficulty for someone below the threshold line ‘the intersect’ to save money and sustain their wealth. The model shows how even as income today increases, income tomorrow will decrease if the income does not cross over the threshold. The poverty trap means that even with actions intended to improve the income today, if it doesn’t do so by enough, the loss will outweigh the gain. An example of this is a farmer buying a small amount of fertiliser to improve the crop yield. The profits of the crop yields must exceed additional expenditure of buying the fertiliser and therefore enough fertiliser needs to be bought to cover a large portion of land. In a nutrition-based poverty trap, the worker needs enough calories to sustain the strength to work but if the work pay is too low, the perfectly able worker cannot access the necessary nutrients through food. This means they become unable to maintain their fitness and they underperform, thus losing said job, which leaves even less income to obtain food. The poverty trap threshold is the point at which the calories consumed surpass the metabolic rate necessary for survival and allow excess energy for strength building. The concept of a poverty trap is a cycle in which only a large increase in income today can sustain a continued growth and anything under it will lead to decline. This concept dates back to 1958 from a doctoral thesis by Dipak Mazumdar but first appeared in my research from Noble Prize-winning economists Professor Duflo and Abjihit.

Dear Diary,

It is me again. I grew tired of gazing at the savage sea water with a smell you could die of. But what was worse was the enormous crowds that also boarded this ship. Especially the men that had a room next to me. They were constantly drunk and so loud throughout the night. It annoyed the living daylights out of me. However there was no way that I could board the ship in second class. I found this out after squabbling with one of the ship’s crew members after finding out I was only a few dollars off. Therefore I had to stay in third class which isn’t the best however it will make do for now. After unpacking my few belongings for the voyage ahead, I left my room and stood by the railing separating me and the sea. I started to think about why I had to abandon home.

Back home my opinion was not valued at all because apparently girls belong in the kitchen, no where else. Well, that was what my father told me every day, at least. I wasn’t allowed to go to school nor was I allowed to go play with friends until the whole house was spotless, and I found this completely unfair because my brothers didn’t have to do anything. Over time, the favouritism for my brothers from my father increased. It increased so much that I wasn’t allowed to see my friends whatsoever, nor was I allowed to telephone them from home or send letters. I had had enough of my father. I had enough of everything to be honest. The way my father would call me terrible names and how my brothers would join in as if nothing was wrong. I knew that America was my only way out of this isolated and miserable life and into a much better life with freedom and much more.

I will be living with my aunt for a little bit until I can get back on my feet and find a job and even better, a place to live. She also immigrated from Germany to America because she couldn’t stand living with my uncle. He would beat her if she even spoke back to him. But before I could dream of this, I had to get there first. I had no clue how but I would work out a way. I vaguely remember the route to my aunt’s house after my long phone call with her last night on my way to the harbour as I explained my whole plan to her. As I was walking back to my room, I could smell the food from the ship’s restaurant. I couldn’t afford anything from there however it reminded me of my mother’s cooking from when she was still alive. She passed from catching a deadly virus which I believe was due to the poor conditions my father made her live in. She was never allowed to wash or brush her teeth. I felt around in my pocket for a tissue to dry the few tears that fell down my cheeks; however all I could find was this pendant of my mother’s. She gave it to me on my 13th birthday as a good luck charm. This made me cry even more. I held it close to my heart and sobbed. After a while of weeping, I heard the men coming back to their room drunk again. I rushed back to my room and went right to bed in hope to fall asleep.

Emily Ardern -Jones

Emily Ardern -Jones

Episode 1 can be found here - Episode 2 can be found here -

Episode 3 can be found here - Episode 4 can be found here -

Episode 5 can be found here - Episode 6 can be found here -

Episode 7 can be found here - Episode 8 can be found here -

A story from the memories of Evíndàl, of the forest tribe of Lúthè-Íldàl, translated from elvish by Rosa Shepherd

My mother stood tall, surrounded by the flames of a thousand fires. The sun elves were burning her up from the inside, yet she faced them down, channelling her energy into the vines that surrounded our treehouses, flicking them at her attackers. She wasn’t going to make it; that much I knew. Her eyes, still green despite the flames all around us, caught mine. She was almost finished. A sun elf blasted her with a jet of white-hot flame, and she fell to the ground.

A hand gripped my shoulder and I turned around, panicking. But it was my father’s face that looked down at me, not one of them. He led me to the others, where a makeshift raft waited. I felt something scorch my bare feet, and turned around-

I woke up screaming. That was the third time I’d had that nightmare. Every time I closed my eyes, the same dreadful scene greeted me: my mother, surrounded by flames. I haven’t told my father - a good decision, I thought, as he was already so worried. Our home planet had been destroyed, he had our whole tribe to look after, and a traumatised daughter would only add to his stress. We were going to seek refuge with the angels, on their strange planet they shared with the Dwarves and those funny ape-like creatures they were cursed to live among. Apparently the angels were the least powerful of our races, their ancestors having been so greedy that they wanted control over all the elements, but that was only our side of the story. I met one, a lúthè like us, and she seemed alright. Still, I was only young, and it’s not my place to judge. I slid out of my hammock, and tiptoed over to the edge of the raft. The view was amazing from here; I could see right across the Dûrsàl lanes to the shimmering mists surrounding úlúth. It was peaceful here, nearly enough to make me forget about recent events. Sitting down and pressing my blistered hands against the moss covering of the raft, I felt footsteps approaching.

Saìró, my best friend since, well, forever, sat down beside me. His presence was comforting - a scrap of normality after everything that had happened

“I heard you get up,” he said, sounding worried, “You should try and sleep. Remember what your father said - we need to rest if we’re going to make it to earth before the sun elves catch up.”

I sighed. He was right, but I’d rather be tired than have nightmares. I hadn’t told anyone, even Saírò and Híthró, and I usually tell them everything. I just didn’t know how to phrase it, and as the chief’s daughter, I was expected to never show weakness. However, of course, Saírò guessed how I was feeling. It was uncanny how he always did that.

“You’ve been having nightmares, haven’t you?” He sighed and shuffled closer to me. “Why didn’t you tell me?”

“I’m not supposed to be weak.”

Saírò put his arm around me. Honestly, he was like my therapist! “That’s not showing weakness, Evíndàl. That’s a sign you’ve been strong for too long.”

Suddenly, there was a small explosion behind us. Saírò looked at me and rolled his eyes. I stifled a grin. “Hey lovebirds. Couldn’t sleep? Me neither. Sorry to interrupt a moment here, but Evíndàl’s father wants us all in the, uh, meeting room? Might have been a chamber thing but I wasn’t really listening.”

Híthró was holding one of his new experiments, a purple spark that apparently exploded on impact. He was always experimenting with something or other, which was not very elvish of him. Most of us preferred to stick to the tried and tested way of things. He was also a massive tease, and over half of anything he said was completely made up for someone’s amusement, usually his own.

Stretching, I stood up. Saírò did the same. Of course we would be wanted in the meeting. As the last children in the tribe, what they were deciding would affect our future more than anyone’s. We made our way to the council chamber; ‘meeting room’ according to Híthró, where the elders were already sitting down.

- Destino Cultural is a podcast created by students at KES

Thursday the 29th of October 1941. The day I lost everything. It wasn’t just physical things I lost; I lost all hope...

When I had woken to the faint sound of my mother clattering around making porridge in the corner, it hadn’t occurred to me that it might be the last time I ever do so. I unfurled from my pile of musty blankets on the cold, wooden floor and padded across the room to the table. My sister was still sleeping in her makeshift bed and Father was rereading a newspaper from 1938. It may seem strange to you, that he was reading an old newspaper, but we’d been confined in this small basement for the past six weeks without being allowed out. This was our new way of living – as Jews in a Nazi operated country.

A few hours later, we heard the knock from above signalling that the person hiding us wanted to talk. It was a special knock – not just an unrhythmic banging – that told us it was safe to act. Father climbed up the ladder and pushed open the trapdoor that led to above. He climbed out and closed the door behind him.

From where I was, I could hear the muffled sound of voices. This time though, the voices were agitated. When the door opened again, it wasn’t Father or our hider who entered – we had been betrayed...

The man who stood in our basement wore the swastika of our enemies. He surveyed us from a distance and then barked at us to climb the ladder. When I reached the top, I saw Father bound to a chair and our hider was trembling in the corner. My sister climbed up after me, closely followed by Mother and then the enemy. He walked over to my mother and, in a threatening tone, demanded she held out her hands. She did what he asked – she had no choice. When he had finished tightening the cords that tied her wrists together, he moved onto my sister. Then it was my turn. I winced as the rope dug into my skin, binding my rights to freedom, but I said nothing. We still had a chance.

There is a period of time which I don’t remember. All I know is that we were shoved into the back of a van and then forced to eat some stale bread. The next thing I knew, my family and I were lying on a stone floor with a few woven sacks lying in a heap beside us. My sister was still lying unconscious on the floor but both my parents were awake. We were in a box like room with no windows and a sturdy metal door. There was a lit oil lamp attached to one of the walls and a crack of light seeped under the door but that was all we had to see by. Father was surveying the room for any possible escape routes and Mother was attempting to shake my sister awake. I decided that nothing I could do would be of any use so I went back to sleep.

I was woken by Father’s cry of exclamation. He was standing in one corner where he’d found that a small portion of the wall could be opened like a door. It wasn’t a large gap but it led to the outside world and we should be able to fit through it. I wondered why it was there. Had it been created by Jews like us who were trying to escape this imprisonment? If so, how many of them had made it out alive?

Lower School Scholar - Creative Writing Escape Capsule 215 Log 42

London United Kingdom Earth

If anyone finds this, this is my last entry on this log. The year is 2201. My name is Zog, and I am from the planet Zugo. I managed to escape from Zugo and Earth was the nearest planet on the capsule’s radar. I am writing this so the inhabitants of Earth can learn about the appalling living conditions on Zugo, and how there will be many more immigrants after me to seek refuge on this planet.

Zugo is a much smaller planet than Earth. It’s actually twice as small as Earth’s Moon, and is located between Mercury and Venus. The inhabitants of Zugo are known as ‘Zugizens’, short for ‘Zugo Citizens’, and we share a number of similarities with humans ; only the green tinge of our skin sets us apart. Our planet is a single country - the idea was that there would be no languages or borders to divide us, and we would all live harmoniously. The ordinary people follow the system for our whole lives. But we don’t realise that our lives will very shortly turn into torture.

The real reason that the system had been put in place was that the government could keep us all in one place and ‘keep a cap on crime’ as they said. There are thousands of laws on Zugo, ranging from the most serious, like ‘Murderers will be put to death’, to ‘Any member of the public talking with a beggar will be prosecuted’. When we were first taught about these laws in school, we laughed, believing it was all a joke. Two days later, our teacher disappeared. We discovered a law that ‘Any teacher who is laughed at by his/her students does not deserve to teach and will be prosecuted’. It was only then that we realised the severity of the rules.

Living conditions on Zugo make this side alley seem to have high-end hygiene. It’s like a desert, boiling by day and freezing by night. All houses of the ordinary people were the same, with numerous holes in the walls and roofs and crawling with disease-carrying bugs. Hundreds of people die every year, and many more contract deadly infections. There are no windows to keep heat in, and we would surely freeze to death at night if we didn’t light a fire in the centre of our room. Many children die every year as a consequence of hypothermia. But it’s the adults who have it the worst. Once a Zugizen turns 16, it is compulsory to visit the National Employment Office, where they are sorted into one of two groups : Office workers and Field workers. Both are equally bad. If an office worker doesn’t complete their daily assignment, they face an eye-watering 30 minute flogging. In the fields, manual labour - such as constructing and maintaining buildings - is purposely painful and energy-sapping. People have been known to keel over and pass out, unable to cope with the burning heat. They are then beaten with a spiked metal pole. The pay is extremely low, and is barely enough to buy a loaf of stale bread and some mouldy Zugo-Cheese.

On the other side of the divide, the government and the trade leaders live a life of supreme luxury. They live in huge palaces that are run by hundreds of field-working servants, and are exempt from the back-breaking labour which we have to do. They publicly emphasise how much luckier they are than us, and treat us like something that’s come out of a toilet. It’s like a dictatorship : where the few have so much and the many have so little.

If you’re reading this, you may well be wondering, ‘Why can’t the poorer people work to gain these positions in the government?’. It’s not that simple. On Zugo, you are born with your rights, you don’t earn them. Whatever your family did for work before you, you would follow their lead. If your parents were builders, you would become a builder ; if your parents worked in the government, you would inherit the position, along with all of their assets. It means that your future is already cut out for you, whether you like it or - in the case of the majority of Zugizensnot.

As I said before, my name is Zog, and I am a 16 year-old Zugizen. To be precise, my age is 16 years and 244 days. My family consisted of my parents, my 2 brothers and I, and we were happy - happy, that is to say, for a Zugizen family. My parents were both field workers, and so were 2 of my brothers. We had a relatively clean flat, with only a few rats crawling around, and in nearby bins there were plenty of newspapers and plenty of leaves strewn across the ground that could be used to fuel our fire at night. But good things can only last so long. One night, the Secret Police came to our flat. We were huddled around our fire for warmth, and my father was telling funny stories to keep our mood up. We were laughing at my younger brother, who had laughed so much that he wet himself, when the door was battered down and the officers walked in, their navy blue jackets dripping with rainwater from the storm outside. They didn’t even give a chance for my parents to speak ; they just handcuffed them and dragged them out of the room. My next oldest brother ran after them, and I followed him, only to see the unmarked black van screeching off into the rain, sending puddles spraying as high as the roofs of the houses.

I never saw my parents again. My brothers and I asked every one of our neighbours and close friends, but nobody had seen them. Our whole lives were turned upside down. With no parents, my older brother was the only person earning money in our household, and it was starting to put a strain on him - everyday, he would slump in through the doorway, with dark circles under his eyes, and collapse , clutching his sparse daily payment in his blistered hands. It was barely enough for food, let alone the rent and the repairs for the roof. We were starting to grow thinner, our skinny rib bones sticking out prominently, stretching our dry, cracked skin. I had to steal, but my little brother no longer had the energy to go to school, and just stayed at home, curled up in a deformed ball in the corner of our room. As my sixteenth birthday drew closer, I felt so helpless and so scared of my life ahead of me, something which I had no control over whatsoever. It was seven days from my birthday when I realised that I had had enough. I had had enough of being hungry and fearing for my life. It was time for a change.

I made a plan - my brothers and I would sneak into the police station and steal one of the emergency escape capsules, which were designed for space travel. As we had been taught in Physics, their ion drive thrusters could propel the pod for 1 light year, and they have enough food supplies to last that long as well. Our destination would be wherever was closest. It was crazy, but it was the only way to escape. We had to escape. So when my brothers refused to come, I couldn’t understand. They both hated Zugo, so why did they want to stay? They said that it was in case my parents resurfaced. My hopeful mood dropped like a stone. As much as I wanted to contradict them, my parents were dead, end of story. I wasn’t going to wait around for my death too. You may call me a coward, but I would never have stayed on Zugo, even if my brothers did. I wanted to start on a fresh planet, with nobody to be afraid of.

At midnight that night, I said goodbye to my brothers. It was probably the hardest thing that I will ever have to do in my life. I tried one last time to persuade them to come with me, but they stuck with their decision.

I hugged them one last time, then left, dragging my small, tattered briefcase behind me. My plan played out perfectly : at a quarter past midnight, I crept cat-like along the corridor, careful not to alert the guards, and opened the door to the escape pod launch bay. The moment I turned the handle, an ear-splitting wail pierced the air. I shoved the door open and sprinted towards the nearest capsule. Once I had shut the hatch and buckled myself in, I turned on the ignition, and I felt the vibrations shoot through my whole body as the engines fired. The radar beeped animatedly ; it had located the closest planet, labelled ‘Earth’. I selected it as my destination, and flicked the ‘Takeoff’ switch, which amplified the vibrations tenfold. I closed my eyes as the world outside turned to an orange and grey cloud of smoke, and I was sucked into my seat as I was propelled into space. By the time that I looked back, Zugo was nothing more than a green and grey dot in the void of blackness.

The journey was arduously long. The capsule wasn’t built for luxury or entertainment, so I fidgeted in my seat, trying to find a comfortable position, before staring at the passing asteroids and comets or just dozing off. I lost count of the days, and whether it was day or night as I drifted through empty space. I made entries on this log from time to time, reflecting my feelings about leaving and whether my brothers were safe. It was, and still is, my greatest companion throughout the trip.

Yesterday, whilst I was sleeping, the radar began to beep energetically. I blearily looked up to check the notification, and filling the window of the capsule was a great blue, green andwhite orb - Earth. The journey was complete. The descent was by no means smooth ; if I hadn’t been strapped in, I would’ve been bounced around like a ping-pong ball. My view turned into a blaze of orange as I pierced the atmosphere. Suddenly, the flames were replaced by small square patches of green, rapidly growing larger and larger. I could feel my heart frantically pounding on my chest. I had no idea what to do. Was this the end? Was I going to die already?

Luckily, the capsule had the answer. It deployed a parachute, which slowed the fall dramatically. As much as I hate the leaders on Zugo, they really put some thought into designing the capsule. My impact with Earth was soft, and the capsule slowly tilted to one side, then became still. I opened the hatch of the capsule, and went outside.

Earth is a lot cleaner than Zugo : the air isn’t thick and smokey, and there aren’t any putrid smells filling it. My first impression of Earth is certainly a good one.

Night has fallen now, and tomorrow, I hope to meet some humans. I hope that they will be worth the long journey from my home.

I pray that my brothers are safe.

Zog

The main idea behind the DNA damage theory of aging is that unrepaired DNA damage accumulates over time. DNA damage refers to physical alterations in the double helix structure (most common ly single-strand breaks of a DNA molecule). These, if unrepaired, are a cause of point mutations in dividing cells[3].

My project aims to assess the use of Hutchinson-Gilford Progeroid Syndrome (also referred to as progeria) as a model for the natural aging process with emphasis on the mechanisms. I will compare the two and draw a conclusion. In the literature review, I will outline current proposed normal aging mechanisms and then move on to look at those in progeria along with treatments for the condition. In my discussion, I will briefly evaluate the current models for aging and then HGPS as a model for aging. I will then look at the transferability of treatments for HGPS to natural aging. The conclusion I will reach is that though HGPS presents many similarities to normal aging, there are also differences, and we must accept that all models have limitations. HGPS is certainly useful in aiding our understanding of normal aging and HGPS models for aging (cells and mice) can have a role in preclinical trials.

After reading Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal, I gained a keen interest in aging. Whilst Gawande focuses more on the holistic side, I wanted to investigate the scientific side of aging. Upon doing some basic research, I found that aging is a complex topic surrounded with ambiguity. It is hard to put aging down to a single mechanism but on a cellular level is the idea of senescence. Cellular senescence has been shown to be repressed in cancerous cells but promoted in aging cells and so it has been suggested that senescence is a protective mechanism against cancer. In youth, this benefits us, but as senescent cells accumulate as we get older, this can be detrimental[1]. The skyrocketing of life expectancy for humans in the past 200 years can largely be credited to better understanding of healthcare, hygiene and diet but this raises a question as to whether there is a limit to the age we can reach. Well for some, this potential limit occurs much earlier than for most. One such example is those affected by progeroid syndromes (PS). This means they age at an accelerated rate compared with an unaffected person and often die much earlier on in life. I encountered this group of diseases when reading the paper “The Hallmarks of Aging”, a review article, which explains many mechanisms involved in aging[2]. Often mice models with these progeroid syndromes are used to model an aging individual. This intrigued me and I began to research PS further. One of the better known and understood syndromes is Hutchinson-Gilford Progeroid Syndrome, a rare genetic condition. Through this EPQ I would like to understand the mechanisms behind Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria and see how it relates to aging and, ultimately, assess the usefulness of Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria models.

DNA damage is most frequently caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS), also known as free radicals. These are very reactive chemicals made from O2; they have the ability to oxidise DNA leading to oxidised bases and single/double strand breaks. Antioxidants (either produced by our bodies or consumed through diet) inhibit oxidation of DNA by reacting with or breaking down ROS. Howev er, sometimes the level of ROS exceeds the levels of antioxidant; this imbalance is called oxidative stress. The increase in ROS levels can cause the cells to stop replicating (they reach cellular senes cence). The discovery of characteristics of a senescent cell are probably why the free radical theory has been suggested[4]. A senescent cell expresses a Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) which leads to decreased regenerative potential, inflammatory response and can bring about tissue dysfunction. For example, senescent cells secrete proteases which can disrupt the cell membrane structure by severing receptors or signalling complexes. Senescent cells are also thought to secrete proteins coded by the SASP gene that affect healthy nearby cells. This is exacerbated by the exponential accumulation of senescent cells with age[1].

DNA damage is extremely frequent yet the effects are somehow countered. DNA repair mechanisms specific to different types of damage are in place with most excising the damaged area. For the dou ble strand breaks (DSB), the repair mechanism is mainly the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) in which Ku proteins, which align the DNA, facilitate the binding of nucleases and polymer ases to cut back or fill in nucleotides at the broken ends of DNA. Once these are compatible, ligases join the DNA ends[5]. A more accurate method of DSB repair is the homology-dependent DSB repair where the broken section is retained, as opposed to it being lost in NHEJ, as the missing section is copied off of the homologous chromosome[6].

ROS also trigger the immune system leading to excess inflammation which then plays a role in the development of many age-related conditions such as COPD, CVD and chronic kidney disease[4].

Figure 1: A, how telomerase protects DNA ends; B, the effect of abundant telomerase; C, the effect of insufficient telomerase[7]

TO WHAT EXTENT CAN

OF HUTCHINSON-GILFORD PROGERIA BE USED TO MODEL NORMAL AGING?

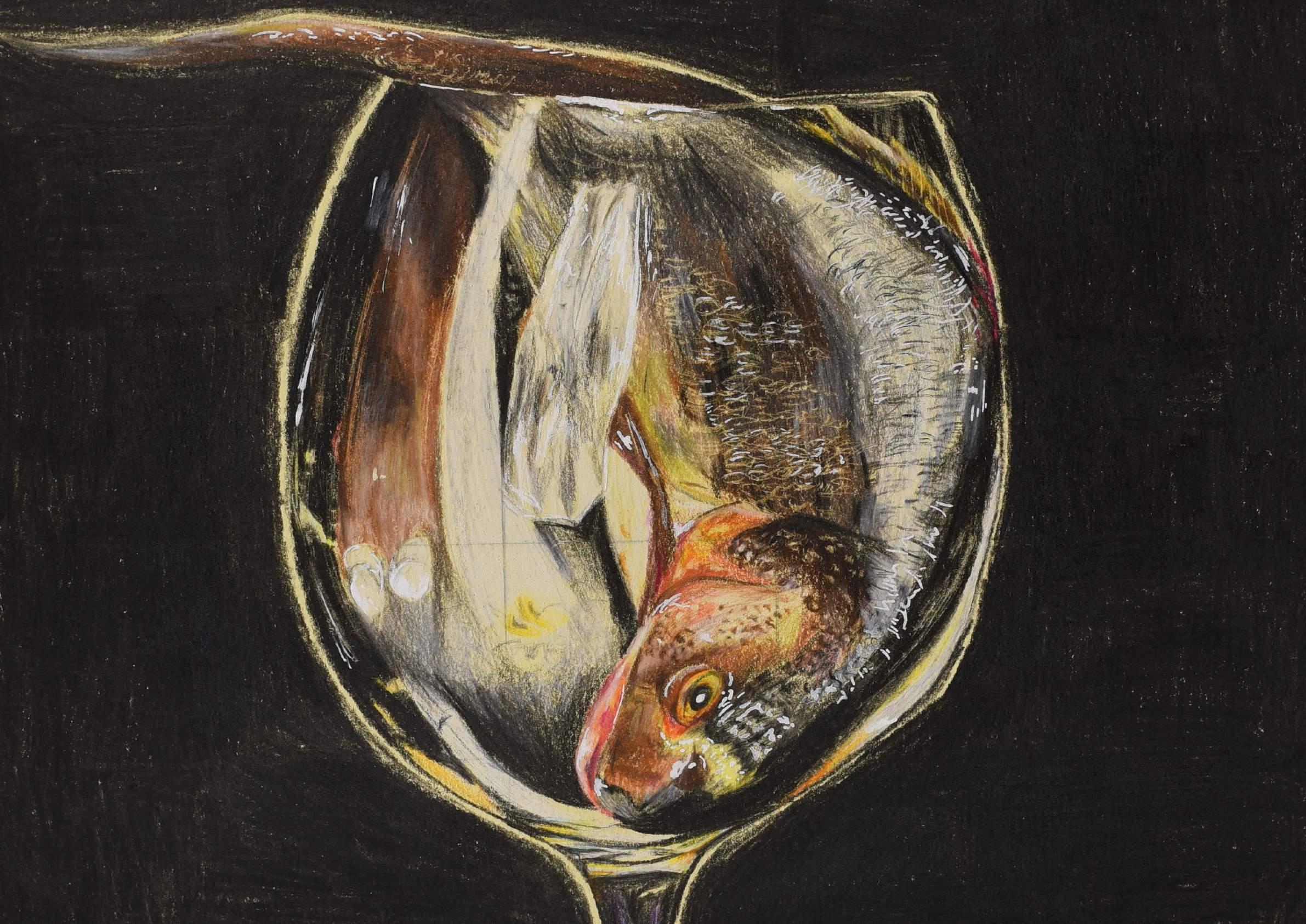

Upper School - Art

Upper School - Art

I hope that you enjoy this small selection of work produced by KES students during the previous academic year. I’m sure that you will agree that they are impressive in both their range and depth. Many of these have been researched and written outside of our core curriculum, albeit with the guidance and support of their teachers. This demonstrates the kind of intellectual curiosity and independence that we aim to foster in all our students.

Lawson Co ordinator for the Very Able

Cover art by: Tessa Thomson

Mr

Lawson Co ordinator for the Very Able

Cover art by: Tessa Thomson

Mr