Adaptive Learning

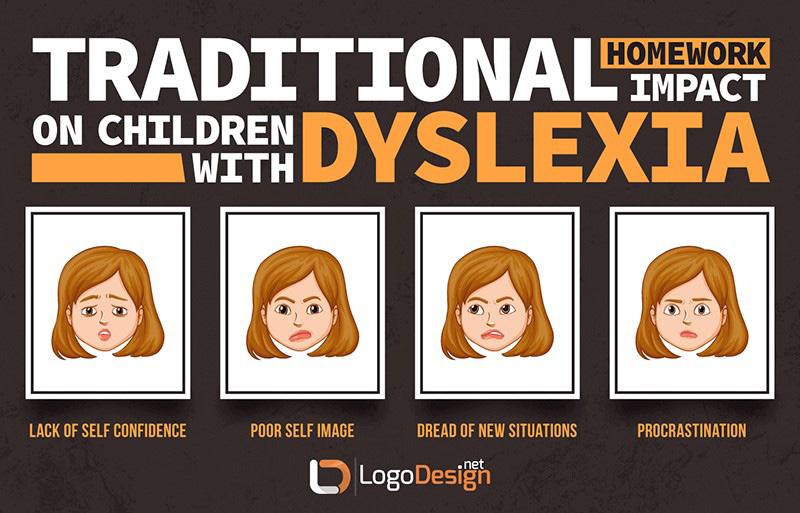

Dyslexia is a consequence of the way a person’s brain is organized. Learning to read requires making the association between printed symbols and spoken words and spoken sounds. These associations must become firmly fixed in memory for reading to be fluent. People with dyslexia have great difficulty establishing these associations. The exact cause of the difference in the brain is not known, but recent research and new tech nology make it possible to identify some of the differences in the brains of people with dyslexia. Also, dyslexia often appears in families across generations. Currently, the search for the genetic basis of dyslexia is underway in various locations around the world.

We do not really know how many people have dyslexia. Since there has not been a generally accepted definition until recently, estimates have varied widely. The National Institutes of Health have estimated that 15% of the population may have dyslexia. In Tennessee, we estimate that at least 100,000 students in K-12 classes have dyslexia.

There is no solid research evidence that using colored lenses will improve reading for individuals with dyslexia. For people with dyslexia to learn to read, they must receive many hours of careful, systematic instruction in the sound system of the language. Any other treatments which may be recommended and attempted should not replace direct instruction in reading and writing.

If your child has had difficulty learning to read words and spell, she might have dyslexia. Young children with dyslexia typically have difficulty learning the alphabet, rhyming, and dividing words into their sounds. Many parents of students with dyslexia describe their children as bright and eager learners until they encounter instruction in reading. At such time, they often become frustrated. Some times these children are able to memorize enough words to appear as if they are reading. When the number of words they must memorize becomes overwhelming (about third grade), the difficulty with reading becomes apparent. Simply stated, if your child has unusual difficulty pronouncing the words when he/she reads and spelling the words he/she writes (compared to others of the same age), you should consider an assessment for dyslexia.

If you think your child may have dyslexia, contact your school principal and explain your concern. Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEIA Reauthorization 2004) and Public Law 94-142, the Education for all Hand icapped Children Act of 1978, parents have the right to request an evaluation from the school, if a disability is suspected. Generally, schools provide a basic evaluation, and are required by state law to conduct testing to determine if a student struggles with reading due to characteristics of dyslexia. Should you wish to pursue the diagnosis privately, you should seek a qualified evaluator. If you decide to use a private evaluator, ask if this individual is familiar with diagnosing dyslexia and which areas she will be testing. An evaluation for dyslexia may include measures of word recognition, word attack (sounding out words), spelling, reading compre hension, phonological processing and written ex pression. In addition, a comprehensive evaluation should include assessment of receptive language skills (i.e., listening comprehension) which affect learning to read and write and must be included to help identify potential cause of any identified area of underachievement in reading comprehension.

No. Dyslexia is a lifelong condition. However, with appropriate remediation, individuals with dyslexia can learn to read and write. With good instruction, dyslexia becomes much less debilitating. Many students with dyslexia attend college and become successful in positions which require considerable reading and writing. Without this instruction, many people with dyslexia will suffer from frustration, decreased self-esteem, and difficulty maintaining employment commensurate with their ability.

Yes. Research indicates that individuals with dyslexia also can have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which includes the predominately inattentive subtype, the predominately hyperac tive-subtype, and the combined subtype.

Click on the below link to view a larger version online. https://www.readingrockets.org/article/faqs-about-dyslexia

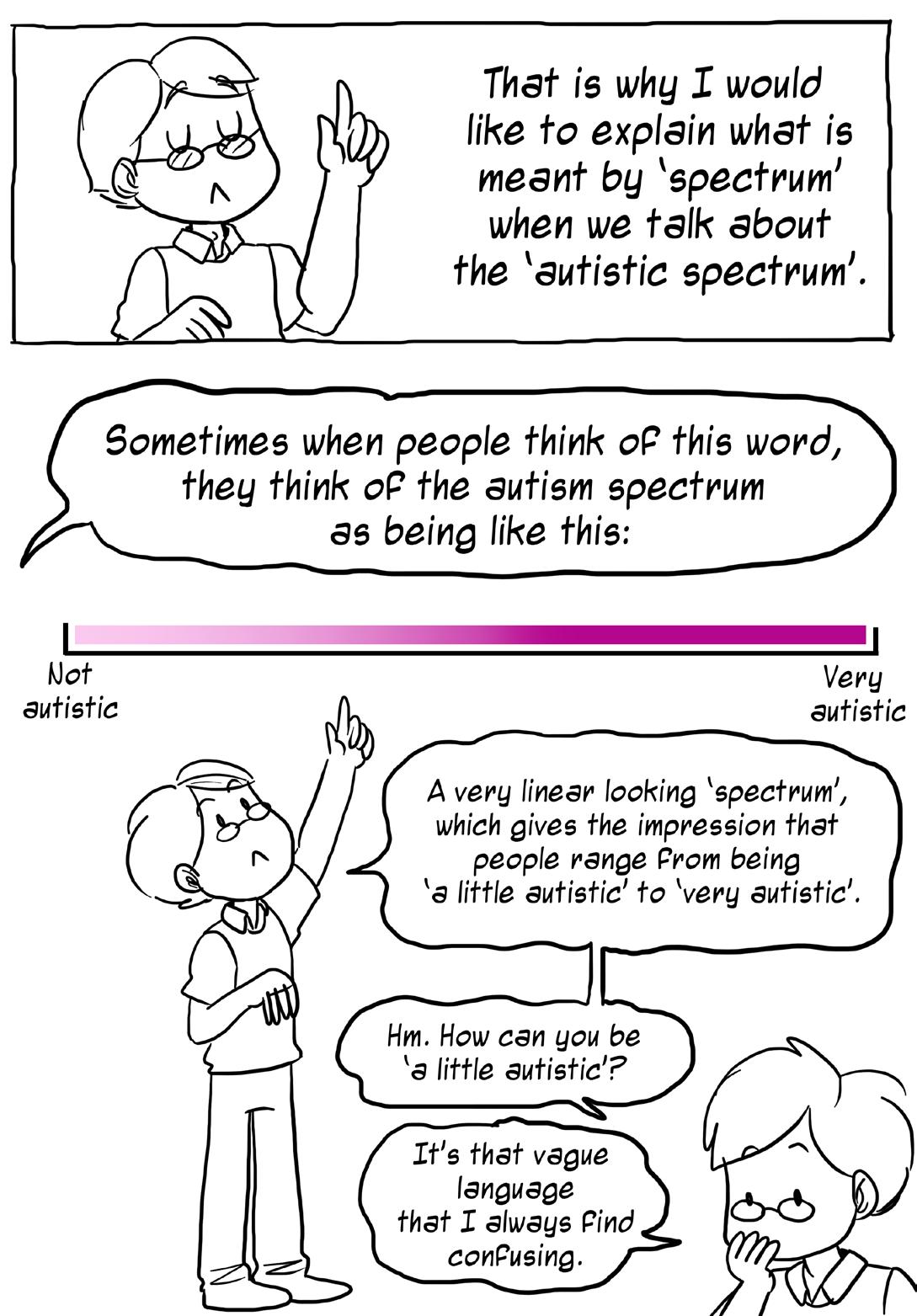

Adapted from: P. Kluth (2010). “You’re Going to Love This Kid!”: Teaching Students with Autism in the Inclusive Classroom.

While most educators agree that no recipe exists for teaching any individual student or group of stu dents, there are certainly some guidelines that can be helpful for supporting students with certain labels. Students with autism may have unique needs with learning, social skills, and communication, therefore, teachers will need strategies to address each one of these areas. These ten simple ideas will help teachers address some of the aforementioned needs and provide guidance for bringing out the best in learners with autism labels.

Oftentimes, educators needing information about a student will study the individual’s educational re cords. While these documents are certainly one source of information, they are seldom the most help ful source of information. Teachers wanting to know more about a student with autism should ask that student to provide information. Some students will be quite wiling and able to share information while others may need coaxing or support from family members. Teachers might ask for this information in a myriad of ways. For instance, they might ask the student to take a short survey or sit for an informal interview. One teacher asked his student with autism, to create a list of teaching tips that might help kids with learning differences. The teacher then published the guide and gave it out to all educators in the school.

If the student with autism is unable to communicate in a reliable way, teachers can go to families for help. Parents can share the teaching tips they have found most useful in the home or provide video of the learner engaged in different family and community activities. These types of materials tend to give educators ideas that are more useful and concrete than do traditional educational reports and assess ments.

Whenever possible, educators should use interests, strengths, skills, areas of expertise, and gifts as tools for teaching. Can a passion for GPS be used to inspire more reading (operations manuals), new math skills (be a “human GPS”-calculate shortest route between two places), or fun social studies questions (“How would the world be different today if Christopher Columbus had GPS?”) . [For more on using fascinations to support students with autism see Just Give Him the Whale, a book I wrote on this topic with my colleague, Patrick Schwarz.]

Students with autism may have unique needs with learning, social skills, and communication. These ten simple ideas will help teachers address some of these needs and provide guidance for bringing out the best in learners with autism.

In some classrooms, a handful of students dominate small-group conversations and whole-class dis cussions. While it is important for these verbal and outgoing students to have a voice in the classroom, it is equally important for other students — including shy and quiet students, students using English as a second language, and students with disabilities — to have opportunities to share and challenge ideas, ask and answer questions, and exchange thoughts. To ensure that all students have opportunities to communicate, teachers need to put structures and activities in place that allow for interaction.

In one classroom, students were asked to “turn and talk” to each other at various points in the day. A high school history teacher used this strategy throughout the year to break up his lectures and to give students time to teach the material to each other. After giving mini-lectures of fifteen minutes, he asked students to turn to a partner and answer a specific question or re-explain a concept he had taught. For instance, after giving a short lecture on the Presidency, he asked students to discuss, “What qualities do Americans seem to want in a President?; and “How has this list of desired qualities changed over time?” A student with Asperger’s syndrome who needed practice with skills such as staying on topic and turn taking was able to practice them daily.

Teachers can also provide opportunities for communication by giving all students “airtime” during whole-class discussion. One way to do this is to ask for physical whole-class responses to certain prompts. For instance, instead of asking, “Who can tell me a fraction that equals one half?”, the teacher might say, “Stand up if you think you can name a fraction that equals one half”. This strategy not only gives all learners a chance to give an answer, but it allows for some teacher-sanctioned movement, something often welcomed by students with autism. Whole-class physical responses are also appropri ate for students who are non-verbal, making it a perfect choice for the diverse, inclusive classroom.

Choice may not only give students a feeling of control in their lives, but an opportunity to learn about themselves as workers and learners. Choice may be especially helpful for students with autism who have special needs when it comes to learning environment, lesson materials, and communication.

Choice can be built into almost any part of the school day. Students can choose which assessments to complete, which role to take in a cooperative group, and how to receive personal assistance and sup ports. Examples of choices that can be offered in classrooms include:

• Solve five of the ten problems assigned

• Work alone or with a small group

• Read quietly or with a friend

• Use a pencil, pen, or the computer

• Conduct your research in the library or in the resource room

• Take notes using words or pictures

Writing can be a major source of tension and struggle for students with autism. Some students cannot write at all and others who can write, may have a difficult time doing so. In order to support a student struggling with writing, a teacher may try to give the child gentle encouragement as he or she attempts to do some writing- a word, a sentence, or a few lines. Teachers might also allow the student to use a computer, word processor, or even an old typewriter for some or for all lessons. For some learners, be ing able to use a word processor when writing helps them focus on the task at hand (content) instead of on their motor skills (process).

While some students with autism are ultra-organized, others need support to find materials, keep their locker and desk areas neat, and remember to bring their assignments home at the end of the day. Con sider implementing support strategies that all students might find useful. For instance, teachers can have all students copy down assignments, pack book bags, put materials away, and clean work spaces together. Structuring this time daily will give all learners the opportunity to be organized and thoughtful about how they prepare to transition from school to home. Specific skills can even be taught during this time (e.g., creating to-do lists, prioritizing tasks).

Some students with autism struggle with transitions. Some are uncomfortable changing from envi ronment to environment, while others have problems moving from activity to activity. Individuals with autism report that changes can be extremely difficult causing stress and feelings of disorientation. Teachers can minimize the discomfort students may feel when transitioning by:

Use a visual timer so students can manage time on their own throughout an activity.

• Giving reminders to the whole class before any transition.

• Providing the student or entire class with a transitional activity such as writing in a homework note book or for younger students, singing a short song about “cleaning up”.

• Asking peers to help in supporting transition time. In elementary classrooms, teachers can ask all students to move from place to place with a partner. In middle and high school classrooms, stu dents might choose a peer to walk with during passing time.

• Provide a transition aid (a toy, object, or picture).

Sometimes students are unsuccessful because they are uncomfortable or feel unsafe or even afraid in their educational environment. Providing an appropriate learning environment can be as central to a student’s success as any teaching strategy or educational tool.

Students with autism will be the most prepared to learn in places where they can relax and feel secure. Ideas for making the classroom more comfortable include providing seating options (e.g., beanbag chairs, rocking chairs); reducing direct light when possible (e.g., using upward projecting light, providing a visor to a student who is especially sensitive); and minimizing distracting noises (e.g., providing ear plugs or headphones during certain activities).

Some students work best when they can pause between tasks and take a break of some kind (walk around, stretch, or simply stop working). Some learners will need walking breaks — these breaks can last anywhere from a few seconds to fifteen or twenty minutes. Some students will need to walk up and down a hallway once or twice, others will be fine if allowed to wander around in the classroom.

A teacher who realized the importance of these instructional pauses decided to offer them to all learn ers. He regularly gave students a prompt to discuss (e.g., What do you know about probability?) and then directed them to “talk and walk” with a partner.

If students are to learn appropriate behaviors, they will need to be in the inclusive environment to see and hear how their peers talk and act. If students are to learn social skills, they will need to be in a space where they can listen to and learn from others who are socializing. If students will need special ized supports to succeed academically, then teachers need to see the learner functioning in the inclusive classroom to know what types of supports will be needed.

If it is true that we learn by doing, then the best way to learn about supporting students with autism in inclusive schools is to include them.

Paula Kluth (2010)Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is characterized by problems with attention, impulse control, and hyperactivity. It usually develops in childhood, but may not be diagnosed until adolescence or adulthood.

Approximately 9% of children in the United States between the ages of 13 and 18 have ADHD, according to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). It is four times more likely to be diagnosed in boys than in girls.

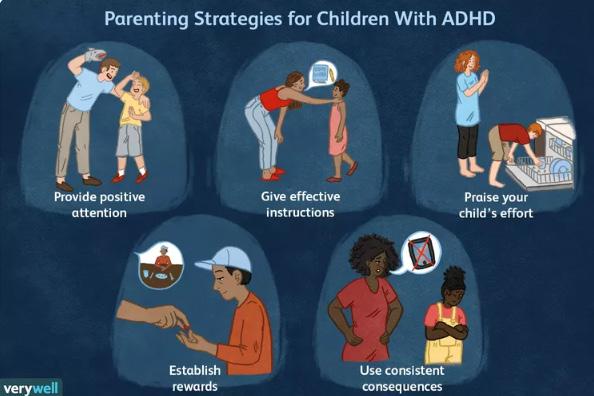

The struggles that children with ADHD face, such as difficulty paying attention, may become apparent once they start school. As such, parents and teachers will need to work together to help kids learn to cope with their ADHD symptoms.

Press Play for Advice On Improving Focus

Hosted by Editor-in-Chief and therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast, featuring Amishi Jha, PhD, a psychology professor, shares how to improve your attention span amid daily distractions. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now: Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts / RSS

Kids and teens with ADHD have unique needs in the classroom. Here are some strategies that parents and teachers of students with ADHD can use to help them succeed at school.

Classroom rules should be clear and concise.2 Rules and expectations for the class should be regularly reviewed and updated when necessary. Rules should be posted in the classroom where they can be easily read.

It’s often useful to have a child repeat back rules, expectations, or other instructions to ensure that they understood. Teachers should keep in mind that a child may have heard the words that were said but misunderstood the meaning.

A child with ADHD may find it helpful to have an index card with the rules taped to their desk for quick reference.

For kids who struggle with time management and “shifting gears” from one task or class to the next, having a schedule handy and reviewing it often can make transitions go more smoothly. You can also use timers, taped time signals, or verbal cues to help a student see how much time is left for an activity.

Students with ADHD are susceptible to distractions, so it can be beneficial to seat them away from sources of classroom disruption such as doors, windows, cubby areas, and pencil sharpeners. Try to limit other distractions in the room, like excessive noise or visual stimuli like clutter, as much as possible.

If a child has an especially difficult time dealing with distractions, being seated near the front of the class close to the teacher may be helpful.

Listening to “white noise” or soft background music can actually improve focus and concentration for some kids with ADHD, though it can be a distraction for those children who don’t.

Kids with and without ADHD benefit from frequent, immediate feedback about their behavior. When necessary, any consequences given for unwanted behaviors should also be swift.

Provide immediate praise for good behavior. If a negative behavior is minimal and not disruptive, it is best to ignore it.

Rewards and incentives should always be used before punishment to motivate a student. To prevent boredom, change up the rewards frequently. Do not use the loss of recess as a consequence for negative behavior.

Kids with ADHD benefit from physical activity and may be able to focus better after being outside or in gym class. Prioritizing rewards over punishment will help ensure that school continues to feel like a positive place for kids with ADHD.

Kids with ADHD tend to struggle with sitting still for long periods of time, so giving them frequent opportunities to get up and move around can be a big help.

You can provide them with a physical break by having them hand out or collect papers or classroom materials, run an errand to the office or another part of the building, or erase the board. Even something as simple as letting them go get a drink of water at the water fountain can provide a moment of activity.

Students with ADHD tend to be restless. While a standard classroom rule may be that students must sit in their seats during lessons, a child with ADHD may be able to stay on task better if they’re allowed to stand up.

For kids who tend to fidget, holding a small “Koosh Ball” or something tactile to manipulate (like Silly Putty) provides a little stimulation without disrupting the classroom.

Some studies have claimed that chewing gum may improve certain students’ concentration, but the research has not been conclusive. Furthermore, many schools do not allow students to chew gum.

For a child with ADHD who is prone to becoming overwhelmed, it can be helpful to reduce the total workload by breaking it down into smaller sections. Teachers can help students avoid feeling overloaded with information by giving concise one- or two-step directions.

Kids with ADHD may also have sleep problems that affect their behavior and their ability to pay atten tion in class.6 In general, students tend to be “fresher” and less fatigued earlier in the day, though teens and college students are more likely to struggle with morning classes. It’s also not unusual for kids to have a bit of a slump after lunch.

If possible, plan to have the class tackle the most difficult academic subjects and assignments when they are most alert and engaged.

Children with ADHD may need extra help from a classroom aid, though these staff members are not always available. Likewise, access to academic support services for students with ADHD may not be in place.

Even if a child does have one-on-one help from an adult, it can sometimes be helpful to arrange for peer support. Pairing a student with ADHD up with a willing, kind, and mature classmate can be a beneficial experience for both kids. A child’s “study buddy” can give reminders, help them stay on task or refocus after being interrupted, and provide encouragement.

Working with another student can also help a child with ADHD improve their social skills and enhance the quality of their relationships with peers—both of which can be struggles for kids with ADHD.

A successful school strategy for a child with ADHD must meet the triad of academic instruction, behav ioral interventions, and classroom accommodations. While the regular implementation of these strat egies can make a world of difference to a child with ADHD, they will also benefit the whole classroom environment.

For more information about anything covered in the magazine, or general information about learning support, please contact:

King Edward VI School SENDCO Mrs Ramshaw znr@kes.hants.sch.uk