Featuring 351 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children's and YA books

KIRKUS VOL. LXXXVII, NO.

2

|

15

JANUARY

2019

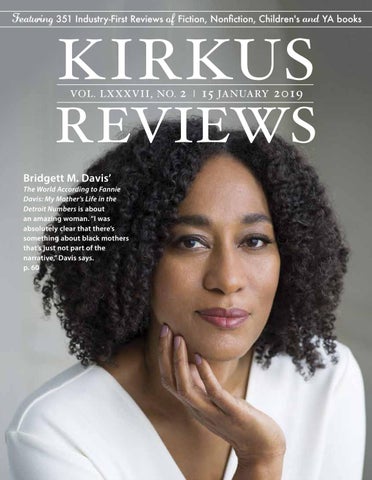

REVIEWS Bridgett M. Davis’

The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother’s Life in the Detroit Numbers is about an amazing woman. “I was absolutely clear that there’s something about black mothers that’s just not part of the narrative,” Davis says. p. 60

from the editor’s desk:

Excellent January Books B Y C LA I B ORNE

Chairman H E R B E RT S I M O N President & Publisher M A RC W I N K E L M A N

SM I T H

# Chief Executive Officer M E G L A B O R D E KU E H N mkuehn@kirkus.com Photo courtesy Michael Thad Carter

Talk to Me by John Kenney (Jan. 15): “It’s a case of death by internet when the fortunes of a beloved network news anchor take a nose dive after a shameful mistake on the set. Kenney opens his modern morality tale with a literal fall—a man jumping from a plane with no plans to open his parachute. As he plummets, he imagines the coverage: ‘Ted Grayson, the longtime anchor of the evening news, died today in an embarrassing skydiving accident on eastern Long Island. Sources say the disgraced former newsman may have taken his own life. He was fiftynine.’ A few weeks earlier, Ted exploded at the young Polish hairstylClaiborne Smith ist on the set, mistaking her smile of excitement for one of ridicule, shouting obscenities and repeatedly calling her a ‘Russian whore.’…A powerful and moving rendition of a story we’ve been waiting to hear: what it’s like to be the bad guy in this ripped-from-the-headlines situation.” House of Stone by Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (Jan. 29): “Life under Robert Mugabe’s brutal government takes center stage in this harrowing novel of Zimbabwe. Seventeenyear-old Bukhosi Mlambo has been missing for more than a week, since his disappearance during a political rally. His parents, Abednego and Mama Agnes, desperate to find him, have accepted the emotional support and help of their tenant, Zamani, the unreliable narrator through whom the story is told. Zamani, an orphan, feeling a ‘prick of opportunity,’ takes advantage of their desperation and endeavors to replace Bukhosi and go from ‘surrogate son’ to ‘son’ through a variety of manipulative acts….A multilayered, twisting, and surprising whirlwind of a novel that is as impressive as it is heartbreaking.”

2

|

15 january 2019

|

|

kirkus.com

Managing/Nonfiction Editor E R I C L I E B E T R AU eliebetrau@kirkus.com Fiction Editor L AU R I E M U C H N I C K lmuchnick@kirkus.com Children’s Editor VICKY SMITH vsmith@kirkus.com Young Adult Editor L AU R A S I M E O N lsimeon@kirkus.com Staff Writer MEGAN LABRISE mlabrise@kirkus.com Vice President of Kirkus Indie KAREN SCHECHNER kschechner@kirkus.com

Indie Editor M Y R A F O R S B E RG mforsberg@kirkus.com Indie Editorial Assistant K AT E R I N A P A P P A S kpappas@kirkus.com Editorial Assistant CHELSEA ENNEN cennen@kirkus.com Mysteries Editor THOMAS LEITCH Contributing Editor G R E G O RY M c N A M E E Copy Editor BETSY JUDKINS Designer ALEX HEAD Director of Kirkus Editorial L AU R E N B A I L E Y lbailey@kirkus.com

Submission Guidelines: www.kirkusreviews.com/about/submission-guidlines Subscriptions: www.kirkusreviews.com/subscription Newsletters: www.kirkusreviews.com/subscription/newsletter/add

from the editor’s desk

Vice President of Marketing SARAH KALINA skalina@kirkus.com

Senior Indie Editor D AV I D R A P P drapp@kirkus.com

Spin by Lamar Giles (Jan. 29): “Two African-American teens who dislike each other find themselves working together to solve the murder of a mutual friend. Kya Caine and Fatima ‘Fuse’ Fallon were both in the orbit of Paris Secord, aka DJ ParSec. Kya and Paris were friends from their neighborhood, while Fuse’s skill with social media made her the ideal person to promote this music among #ParSecNation fans. On the night Paris is murdered, both girls happen on the scene within minutes of each other; her death is a blow, and their shock and pain run deep….The depiction of the grassroots music scene that feeds hip-hop and keeps it cutting edge is seamlessly woven into the narrative. Not to be missed.” (Mystery. 12-18)

Print indexes: www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/print-indexes Kirkus Blog: www.kirkusreviews.com/blog Advertising Opportunities: www.kirkusreviews.com/about/advertising opportunities

Editor -in- Chief CLAIBORNE SMITH csmith@kirkus.com

|

Production Editor C AT H E R I N E B R E S N E R cbresner@kirkus.com Creative Lead A R D E N P I AC E N Z A apiacenza@kirkus.com Website and Software Developer P E RC Y P E R E Z pperez@kirkus.com Advertising Director M O N I Q U E S T E N S RU D mstensrud@kirkus.com Controller MICHELLE GONZALES mgonzales@kirkus.com for customer service or subscription questions, please call 1-800- 316-9361

Cover photo by Nina Subin

you can now purchase books online at kirkus.com

contents fiction

The Kirkus Star is awarded to books of remarkable merit, as determined by the impartial editors of Kirkus.

INDEX TO STARRED REVIEWS............................................................ 4 REVIEWS................................................................................................ 4 EDITOR’S NOTE..................................................................................... 6 KAREN THOMPSON WALKER’S HYPNOTIC NEW NOVEL............ 14 CHRIS CANDER WRITES THROUGH A PIANO................................ 24 MYSTERY.............................................................................................. 36 SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY.......................................................... 41 ROMANCE............................................................................................ 43

nonfiction

INDEX TO STARRED REVIEWS..........................................................44 REVIEWS..............................................................................................44 EDITOR’S NOTE...................................................................................46 ON THE COVER: BRIDGETT M. DAVIS............................................ 60 STEPHANIE LAND SHATTERS STEREOTYPES................................66

children’s

INDEX TO STARRED REVIEWS.......................................................... 74 REVIEWS...............................................................................................75 EDITOR’S NOTE................................................................................... 76 YOON HA LEE’S HIGH-OCTANE THRILLER.................................... 92 BOARD AND NOVELTY BOOKS.......................................................124 CONTINUING SERIES.......................................................................128

young adult

INDEX TO STARRED REVIEWS.........................................................130 REVIEWS.............................................................................................130 EDITOR’S NOTE..................................................................................132 SOMEDAY WE WILL FLY TAKES OFF..............................................138 CONTINUING SERIES.......................................................................143

In his lyric memoir in essays, Mitchell S. Jackson navigates family strife, crime, guns, toxic masculinity, substance abuse and addiction, and the meaning of “hustle,” among countless other timely topics. Read the review on p. 54.

indie

INDEX TO STARRED REVIEWS........................................................ 144 REVIEWS............................................................................................ 144 EDITOR’S NOTE.................................................................................146 INDIE Q&A: ANNA TODD..................................................................152 QUEERIES: OMISE’EKE TINSLEY.................................................... 160 INDIE BOOKS OF THE MONTH........................................................ 166

Don’t wait on the mail for reviews! You can read pre-publication reviews as they are released on kirkus.com—even before they are published in the magazine. You can also access the current issue and back issues of Kirkus Reviews on our website by logging in as a subscriber. If you do not have a username or password, please contact customer care to set up your account by calling 1.800.316.9361 or emailing customers@kirkusreviews.com.

APPRECIATIONS:UMBERTO ECO’S FOUCAULT’S PENDULUM TURNS 30........................................................................................... 167 |

kirkus.com

|

contents

|

15 january 2019

|

3

fiction COURTING MR. LINCOLN

These titles earned the Kirkus Star:

Bayard, Louis Algonquin (400 pp.) $27.95 | Apr. 23, 2019 978-1-61620-847-9

COURTING MR. LINCOLN by Louis Bayard....................................... 4 BIG BANG by David Bowman............................................................. 6 OUTSIDE LOOKING IN by T.C. Boyle...................................................7

Historical thriller veteran Bayard (Lucky Strikes, 2016, etc.) finds suspense in the three-cornered relationship of Mary Todd, her awkward but compelling suitor, Abraham Lincoln, and his closest companion, debonair Joshua Speed. About to turn 21 when she arrives in Springfield in 1839, Mary teeters on the brink of old-maidenhood. She’s too sharptongued and politically astute for the town’s eligible men— including, she thinks regretfully, handsome merchant Joshua Speed, whom she initially finds more charming than his friend Lincoln, who is as tongue-tied with ladies as he is plainspokenly eloquent at the Illinois statehouse. But Mary becomes intrigued by Lincoln, a rising Whig politician who finds a woman with brains and savvy enticing rather than off-putting. She doesn’t yet realize how destabilizing their budding romance is for Lincoln and Speed. For two years the men have shared a room and a bed, not in itself unusual for 19th-century bachelors, but as Lincoln hungrily learned the ways of polite society from his new friend, a deeper intimacy developed. By the time Mary appears, Lincoln and Speed, each profoundly lonely for his own reasons, share an unusually intense bond apparent to all. Alternating between Mary’s and Joshua’s points of view, Bayard chronicles the bumpy progression of the Lincoln-Todd courtship, its painful blow-up, and Lincoln’s subsequent collapse into crippling depression. There are no villains in this acute and compassionate portrait: When Speed warns Lincoln that Mary “will drain [you] dry,” we can see there’s some truth in this statement but even more truth in Lincoln’s retort, “Is it this girl you object to? Or is it any girl?” The author commendably refrains from imposing 21st-century sexual mores on the Lincoln-Speed relationship, profoundly loving but not physical in Bayard’s depiction. Mary Todd, by contrast, gets a welcome contemporary reappraisal as a woman of spirit and will, not the needy hysteric painted by traditional historians. Not a lot of action, but in Bayard’s skilled hands, three complicated people groping toward a new phase in their lives is all the plot you need.

THE SPECTATORS by Jennifer duBois................................................ 13 AFTERNOON OF A FAUN by James Lasdun......................................25 INSTRUCTIONS FOR A FUNERAL by David Means....................... 26 FINDING AGAIN THE WORLD by John Metcalf.............................. 28 VERSES FOR THE DEAD by Douglas Preston & Lincoln Child....... 29 THE OLD DRIFT by Namwali Serpell..................................................32 RUTTING SEASON by Mandeliene Smith..........................................32 GREAT AMERICAN DESERT by Terese Svoboda................................ 33 THERE’S A WORD FOR THAT by Sloane Tanen.................................34 FALL BACK DOWN WHEN I DIE by Joe Wilkins............................... 35 THE LIGHT BRIGADE by Kameron Hurley........................................41 THE PRIORY OF THE ORANGE TREE by Samantha Shannon......... 42

BIG BANG

Bowman, David Little, Brown (624 pp.) $32.00 | Jan. 15, 2019 978-0-316-56023-8

4

|

15 january 2019

|

fiction

|

kirkus.com

|

THE MALTA EXCHANGE

Religion and murder meet in Malta and Rome in this 14th entry in the author’s Cotton Malone series (The Bishop’s Pawn, 2018, etc.). The pope has died, and His Eminence Kastor Cardinal Gallo schemes to get the job. Unfortunately, he is “radioactive” in the church, even “proclaimed a threat to all the faithful.” Oh, and he only fakes his religious belief. All he wants is power, and he will kill for it. His identical twin brother, Pollux, is a Knight of Malta but not a priest and certainly not his brother’s keeper. Meanwhile, series hero Cotton Malone is on a special freelance assignment from Britain’s MI6, looking for rumored secret correspondence between Churchill and Mussolini. And former Army Ranger Luke Daniels trails Kastor, who is from Malta, where much of the story takes place. Cotton finds a mysterious ring engraved with a Maltese cross and a five-word palindrome that’s spelled out a tad too often. Perhaps a secret lies in the engraved words. He also uncovers documents hidden by Mussolini and looks for what’s hidden in an obelisk in Rome. The intrigue is intense as Kastor and a few goons will stoop to murder to abet his rise to the most powerful post in the Catholic Church. Thriller fans will have their violence fix, but the real fun is in learning about the inner workings of the church, its history dating all the way back to Constantine, and the troubled past of Malta. Cynicism about Christianity abounds; why else would Simon Wiesenthal have said that the Vatican has the best spy service in the world? Popes Pius XI and XII never stood up to the fascists, and perhaps heaven, hell, and the Holy Trinity were invented in the third century merely to differentiate Christianity from Judaism. Cotton is highly capable—“Failure was not his style,” meaning he fits in well among the can-do American heroes in the genre. But Kastor and Pollux are the conniving hypocrites who really pop off the pages. This one will appeal to Dan Brown fans and anyone else in the mood for a page-turning yarn.

y o u n g a d u lt

to a town in mainland Australia. One morning, teenage son Jarrah heads to school, artist and dad Finn goes to work in his home studio, and mom Bridget is preparing to leave for her job as a research biologist. Amid the bustle, for just moments 2-year-old Toby is unsupervised. Despite a supposedly secure gate, he gets into the backyard pool. His drowning shatters the family. Blackadder alternates short chapters from Jarrah’s firstperson point of view, Finn’s told in third person, and Bridget’s in second person, as if we overhear her talking to herself. It’s an effective way of building suspense, as we learn what each one knows—or doesn’t—about Toby’s death and about other members of the family. It also reveals their extreme emotions, ranging from blinding grief to rage, from delusion to suicidal impulses. Within weeks, the family’s once-warm relationships spiral into suspicion and guilt. Friendships and flirtations seem to turn into something more threatening. Then someone is arrested, and the stakes go even higher. Fast-moving but emotionally resonant, the book effectively takes readers inside the minds and hearts of a family blindsided by loss and trying to decide whether they can move forward together, apart, or at all.

Berry, Steve Minotaur (416 pp.) $28.99 | Mar. 19, 2019 978-1-250-14026-5

WAITING FOR BOJANGLES

Bourdeaut, Olivier Trans. by Kramer, Regan Simon & Schuster (176 pp.) $25.00 | Mar. 19, 2019 978-1-5011-4591-9

A young French boy’s adventures with his unpredictable parents. The nameless child narrator lives with his father, mother, and a pet crane dubbed “Mademoiselle Superfluous” in a French apartment crammed with a mountain of unopened mail, a TV crowned by a dunce cap, and a checkerboard-floored front hall. He’s enchanted by the life his parents lead, even when they pull him from school in part because he keeps missing days so the family can go on vacation—“to heaven,” his parents call it. And after the boy’s father, George, leaves his job as a “garage opener” at his wife’s insistence, the family enters into a seemingly limitless stretch of time in which they vacation in Spain, play Nina Simone’s “Mr. Bojangles” on the record player, and mix umbrella-topped cocktails in relative bliss. But reality intrudes after a tax assessor shows up at their apartment to collect an unpaid balance. The mother, already “charmingly ignorant of the way the world work[s],” strays further from reality and toward increasingly erratic and dangerous behavior. As the mother’s mental illness progresses and George and his son attempt to protect her from herself and others, the novel probes the painful and often futile lengths people will go to for those they love. Told partly in rhyme (and interspersed with excerpts from George’s diary), Bourdeaut’s debut is both a charming tale that revels in colorful detail and language and a heart-rending depiction of the brutal march of mental illness. Its part-rhyming structure almost always feels organic (only occasionally

IN THE BLINK OF AN EYE

Blackadder, Jesse St. Martin’s Press (384 pp.) $27.99 | Mar. 19, 2019 978-1-250-19995-9

An absorbing psychological thriller explores how a family reacts when the unthinkable happens. Death strikes in the first pages of this moving novel by Australian writer Blackadder (Chasing the Light, 2013, etc.). The Brennan family is adjusting to a recent move from Tasmania |

kirkus.com

|

fiction

|

15 january 2019

|

5

digging deeper into the world of romance (via podcast) A long, dark January night is the perfect time for a romance novel. I just had the pleasure of catching up with a backlist title: Kresley Cole’s A Hunger Like No Other (2006), the first in her Immortals After Dark series. I don’t think I’ve read a paranormal romance since The Vampire Lestat (does that count?), but I was prompted by a delightful new podcast called Fated Mates, put out by romance author Sarah MacLean and Kirkus reviewer Jen Prokop, in which they’re planning to discuss each installment of Cole’s series, episode by episode. Immortals After Dark is over-the-top fun, creating a world where every kind of creature co-exists: There are vampires, werewolves, Valkyries, sirens, furies, and more living peacefully (more or less) until, every 500 years, the Accession occurs, when they go to war in “a kind of mystical checksand-balances system for an ever growing population of immortals,” as Cole explains it. A Hun ger Like No Other features Emmaline Troy, half-vampire and half-Valkyrie, who’s shocked to learn she’s the fated mate of Lachlain MacRieve, the king of the werewolves (who turns out to be Scottish—who’d have thought?). After reading the book, it was fascinating to hear Sarah and Jen talk about it on the podcast, bringing their wealth of insight to a discussion of the book’s strengths and weaknesses, how it might have been different if it had been written today, and, as they put it in their podcast description, “feminism, patriarchy, modernity, and Moonstruck. Yes, the one with Cher.” If you want to dig deeper in the world of romance, this podcast is a great place to start. Or you could start with one of two January romances that earned starred reviews from Kirkus: The One You Fight For by Roni Loren or Nightchaser by Amanda Bouchet (both published on Jan. 1). Happy reading! —L.M.

reading as cutesy or forced) and lends the narrative a sense of flow and momentum. But it’s the irresistible, childlike sense of delight—even in the face of unimaginable sorrow—that renders the novel a genuinely enjoyable reading experience and one that sparks complex and conflicting emotions. A unique, evocative debut.

BIG BANG

Bowman, David Little, Brown (624 pp.) $32.00 | Jan. 15, 2019 978-0-316-56023-8 A kaleidoscopic portrait of America in the years leading up to the assassination of John F. Kennedy—and a chillingly prophetic vision of how we got to where we are. This is a novel that Bowman, the author of Let the Dog Drive (1992) and two other books, left unpublished when he died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 2012. But unpublished does not mean incomplete. Bowman articulates a vivid point of view in this novel, or, more accurately, a series of points of view, beginning with a prologue in which a variety of historical figures (Norman Mailer; Elvis; J.D. Salinger’s young daughter, Margaret) react to the killing of the president. From there, the action shifts to Mexico City in 1950 and the confluence of some unlikely expatriates, including William S. Burroughs and E. Howard Hunt. “The novel you are about to read is true,” Bowman writes. “All the people who are mentioned—just as Bob Dylan sang—I had to rearrange their faces and give them all another name. Still, this novel is true history.” What Bowman is saying is that history is itself a story, one we tell as much as live. His juxtapositions of incidents and individuals are, in that sense, as much constructions of his imagination as they are mashups of overlapping events. Albert Camus and Maria Callas carry on an affair. JFK and Aristotle Onassis commiserate—and strategize—over the Kennedys’ stillborn child. Bowman is sly about acknowledging his inspirations: Mailer, as established in the opening, and also Don DeLillo, whose Underworld this novel resembles and who appears as a young advertising copywriter. And yet, to call the book derivative is to miss the point. Instead, it is sui generis, the kind of novel that invents its form out of its own frenzied convocation of voices and moments: the 20th century in all its majesty and fear. Bowman’s testament is both lament and celebration— for the betrayed promise of the United States as well as the tragedy of the author’s premature demise.

Laurie Muchnick is the fiction editor. 6

|

15 january 2019

|

fiction

|

kirkus.com

|

Once Timothy Leary opened the Pandora’s box of LSD, everything changed. outside looking in

OUTSIDE LOOKING IN

Fitzhugh and Joanie Loney and their teenage son, Corey. Fitz has been struggling to support himself as a Harvard graduate student in psychology, one of Leary’s advisees, though one who is, as the title says, on the “outside looking in” as the psychedelic hijinks commence. It isn’t long before Leary seduces his student into the inner circle, where Joanie joins them and the nucleus of this family starts to destabilize as they make themselves part of a larger communal tribe. All in the name of science, as Fitz continues to believe, though Leary soon finds himself ousted from Harvard, his work discredited, his students in limbo. Is he a radical, reckless visionary or a selfpromoting huckster? Perhaps a little of both. Without advocating or sermonizing, and without indulging too much in the descriptions of sexual comingling and the obligatory acid tripping, Boyle writes of the 1960s to come from the perspective of the ’60s that will be left behind. It is Leary’s inner circle that soon finds itself on the outside—outside the academy, society, and the law—living in its own bubble, a bubble that will burst once acid emerges from the underground and doses the so-called straight world. In the process, what was once a

Boyle, T.C. Ecco/HarperCollins (400 pp.) $27.99 | Apr. 9, 2019 978-0-06-288298-1 Once Timothy Leary opened the Pandora’s box of LSD, everything changed. Few novelists have benefited more from the freedom unleashed by the psychedelic revolution than the prolific Boyle (The Relive Box, 2017, etc.), but here he shows a buttoned-down control over his material, a deadpan innocence in the face of seismic changes to come. It’s an East Coast novel of academia by the West Coast novelist, and it’s a little like reading Richard Yates on the tripping experience. The novel’s catalyst is Dr. Timothy Leary (“Tim” throughout), though Boyle has wisely opted not to make him the protagonist but instead a figure seen and idealized through the eyes of others. At the novel’s center is the nuclear family of

y o u n g a d u lt

|

kirkus.com

|

fiction

|

15 january 2019

|

7

THE BETTER SISTER

means to a scientific or spiritual end becomes a hedonistic end in itself. And Fitz finds his family, his future, his morals, and his mind at risk. “I could use a little less party and a little more purpose—whatever happened to that?” he asks, long after the balance has been tipped. Keeping his own stylistic flamboyance in check, Boyle evokes a cultural flashpoint with implications that transcend acid flashbacks.

Burke, Alafair Harper/HarperCollins (320 pp.) $26.99 | Apr. 23, 2019 978-0-06-285337-0 When a corporate lawyer who divorced his first wife and married her more successful sister is found dead in his home in the Hamptons, his teenage son goes on trial for murder. The fans who put Burke’s (The Wife, 2018, etc.) last domestic thriller on the bestseller list are going to be happy with this one, a gimmick-free murder mystery with a two-stage surprise ending and uncommonly few credibilitystraining plot elements. No double narrator! No unreliable narrator! No handsome psychopaths from central casting! And though there’s usually at least one character in this type of book who isn’t quite three-dimensional, most of the players here feel like they could have worked in a domestic novel without a murder, which is a kind of test for believability and page-worthiness. The star of the show is Chloe Taylor, a woman’s magazine editorin-chief who has become a hero of the #MeToo movement and a target of misogynist haters on social media. The lumpy area beneath the surface of her smooth, pretty life is the fact that she married her boozy, unstable, maternally incompetent sister’s ex-husband and has been raising her nephew, Ethan, as her own son. When his father turns up dead, Ethan tells so many lies about his doings on the evening in question that despite the fact that he’s obviously not a murderer, he ends up the No. 1 suspect. As soon as he’s arrested, his real mom, Nicky, swoops into town and the sisters form an uneasy and shifting alliance. You’ll think you have this thing all figured out, but a series of reveals at the eleventh hour upend those theories. Most of the important people in this novel are women—the head cop, the defense attorney, the judge—and their competent performances create a solid underpinning for the plot. You’ll kill this one fast and be glad you did.

PICKLE’S PROGRESS

Butler, Marcia Central Avenue Publishing (288 pp.) $27.00 | $16.99 paper | Apr. 9, 2019 978-1-77168-154-4 978-1-77168-155-1 paper Identical twins Stan and Pickle McArdle live tangled lives, fulfilling expectations imposed on them in childhood by their controlling mother. Until one day, they just don’t. After leaving a party in the wee hours (drunk—as usual), Stan McArdle and his wife, Karen, get into an accident on the George Washington Bridge after Stan swerves to avoid a young woman standing in the road. Stan and Karen are injured (there’s blood), but they help the woman into their car and sit to await 8

|

15 january 2019

|

fiction

|

kirkus.com

|

the cops. Fortunately, Stan’s twin brother, Pickle, is on the force, and it’s him they call, knowing he will cover for their drunkenness yet again. The book starts with a crash then slows as the characters’ personalities develop: fussy Stan, bossy Karen, insecure Pickle, and reclusive Junie, the woman from the bridge, who now lives in the basement of Stan and Karen’s brownstone. They exist, as it were, in cages where they feel comfortable. But each squeezes between the bars occasionally to interact in an out-of-character way. Pickle eventually asks a question, which unravels a well-kept secret, which springs the locks of their cages, creating a twist. Butler’s debut is character-driven, with little action and lots of dialogue in which her people maneuver and manipulate to get what they want (or think they want). The characters are exaggerated, often unlikable, and unperceptive at times. Except maybe for Pickle, who, after all, does make progress crawling out of a mold he’d allowed himself to be cast into. There’s no closure to the question “Now what?” But if she’s willing, Butler has a great opportunity to write a sequel and develop more nuanced and introspective characters. In this study of how childhood experiences shape perception, and how deception keeps people caged, Butler shows that nothing need be set in stone.

past impacted the future, including the secret of Hanna’s lost decade. Readers may want to urge Max to confess his secret to Hanna...but then there would be no story. Cantor elevates love as a powerful force that transcends tragedy and shows how music speaks to even the cruelest hearts. A powerful story that exalts the strength of the human spirit.

y o u n g a d u lt

IN ANOTHER TIME

Cantor, Jillian Harper Perennial/HarperCollins (336 pp.) $16.99 paper | Mar. 19, 2019 978-0-06-286332-4 Max Beissinger and Hanna Ginsburg fall in love, but their relationship is destined for heartache when Hitler comes to power and outlaws marriage between Germans and Jews. Max, a bookstore owner, stumbles across Hanna playing her violin at the Lyceum and is smitten. Hanna takes care of her sick mother and practices her instrument in hopes of earning a place in an orchestra. She conceals her growing affair with Max from her mother and sister, who would not approve of her dating outside the Jewish faith. Max has a secret, something he discovers in a journal his father kept, that causes him to suddenly vanish, often for months at a time, telling no one where he is going or where he has been. Hanna breaks off their engagement because of Max’s disappearances, but Max believes his secret can save Hanna should the fraught political climate take a turn for the worse as Hitler continues to rise in power. One evening, when he and Hanna are at his bookstore, Nazis bash the door open. Max grabs Hanna to secure her in a hidden closet, but she breaks away and rushes back for her violin. The Nazis grab them both, and they are separated. The next thing Hanna knows, she awakens in a field, not remembering the events of the past 10 years. Max, who had a mysterious glimpse of the future, knows she must be alive and works to find her. Cantor propels readers back and forth from the 1930s to the ’50s in this well-researched historical novel, showing how the |

kirkus.com

|

fiction

|

15 january 2019

|

9

LEADING MEN

playwright’s life—but also plagued by doubts about his own purpose (“If Frank could not be the fountain, he could at least feel the spray,” Castellani writes). In portions of the novel set in 1953, Castellani imagines that the couple meets a glamorous Swedish mother and daughter, “these fierce and delicate greyhounds, with their taut slender necks,” the younger of whom, Anja Bloom, they take under their wings. She will become an international star known for her work in art house cinema, but her fame won’t soften her “haunted and hard” heart. Castellani (The Art of Perspective, 2016) shuttles between 1953, when Williams was collaborating with Paul Bowles to write the screenplay for Luchino Visconti’s Senso, and now, when Bloom’s star has faded but she is still in possession of Williams’ (imaginary) last creation, a terrible one-act play, Call It Joy, that he wrote to assuage his guilt for not visiting Merlo in the hospital in 1963 as he was dying of lung cancer. Will Bloom allow the play to be performed? In an ambitious act of ventriloquism, Castellani includes the entire script of the play here. There are only a few missteps in the novel; it is not clear, for example, why anyone would fall in love with the petty and cantankerous writer John Horne Burns. Humane, witty, and bold, this novel imagines the life of a loving but tortured couple.

Castellani, Christopher Viking (368 pp.) $27.00 | Feb. 12, 2019 978-0-525-55905-4 To the spate of novels investigating the lives of famous artists and their relationships with the people who loved them most, add this intriguing take on Tennessee Williams and his lover of 15 years, Frank Merlo. Nicknamed the Horse by Williams for his stocky build, Merlo was a man from a working-class Italian family in New Jersey who rose to elite echelons of society through his relationship with Williams, becoming friends with, among others, Anna Magnani and Truman Capote (whom neither he nor Williams cherished). Castellani’s Merlo, with a heart that’s “big and simple and practical,” is the focus here. Merlo is fulfilled by his work for Williams—arranging the details of the scatterbrained

BOY SWALLOWS UNIVERSE

Dalton, Trent Harper/HarperCollins (464 pp.) $26.99 | Apr. 2, 2019 978-0-06-289810-4

An Australian teen aspires to reassemble his broken home, bust a drug ring, and decrypt his brother’s odd pronouncements. That’s a lot for a 12-year-old living outside of Brisbane to take on; and this, Dalton’s debut novel, also feels like a case of reach exceeding grasp. But it has the virtue of an earnest and bright narrator in Eli, who, as the story opens in 1985, is living with his mother and her boyfriend, Lyle, who are scraping out a living as small-time heroin dealers. His older brother, August, prefers to communicate by writing in the air with his finger, and his air-scribbles are generally koanlike and inscrutable: “Your end is a dead blue wren,” “Boy swallows universe,” and such like. The closest thing to a normal person in Eli’s life is Slim, an elderly small-time criminal whose knack for prison escapes in his youth has become the stuff of legend. After a falling-out with rival dealers, Lyle is killed, mom is sent to prison, and Eli loses a finger, leaving the brothers to live unhappily with their alcoholic father. Dalton’s novel is a kind of picaresque, built around comic scenes amid the grim setting, involving Eli’s taking cues from Slim in the ensuing years to either break into things (such as the prison where mom is sentenced) or break out of his desultory existence by angling his way into a journalism internship, where he’s determined to reveal the truth about the esteemed businessman who’s also a drug kingpin. “A confident sneak can make his own magic,” Eli explains. But the 10

|

15 january 2019

|

fiction

|

kirkus.com

|

A young man makes a demanding but soul-stirring trek through the kitchens of France’s finer restaurants. the cook

magical elements promised in the novel’s early pages, mostly via August’s non sequiturs, either get abandoned or turn out to be relatively pedantic matters of interpretation. A likable debut that trades its early high-flown ambitions for dramatic but familiar coming-of-age fare.

to transplant surgery. The trajectory of this novel is a similar forward march, but it encompasses more emotional and sensory detail; it’s slim but potent. The story follows Mauro and his love of cooking from childhood (baking cakes in elementary school) and young adulthood (weaning his friends off fast food with homemade meals) to pursuing a culinary career in his native France. Every tale of culinary apprenticeship seems to demand a trial by fire in a perfectionist kitchen, and this one is no different: He’s chided, whacked in the head with a melon baller, and works endless hours. His social life vaporizes; his girlfriend leaves him. But the author does a fine job of exploring why someone like Mauro is still enchanted by the lifestyle. A love of food is part of it, and she writes lovingly about “the taste of a tomato, the subtlety of a stalk of asparagus, the crunch of a curly endive.” She’s less interested in food porn, though, than in the way the kitchen provides a kind of holistic calm: “He can cook by ear as well as with his nose, hands, mouth, and eyes.” What Mauro’s life lacks is time to rest, and the anonymous narrator, vaguely suggested as a potential love interest, frames his life as bittersweet, shaped by success in the culinary world but

THE COOK

de Kerangal, Maylis Trans. by Taylor, Sam Farrar, Straus and Giroux (112 pp.) $22.00 | Mar. 26, 2019 978-0-374-12090-0 A young man makes a demanding but soul-stirring trek through the kitchens of France’s finer restaurants. De Kerangal’s previous novel published in English, The Heart (2016), was a straightforward tale of organ donation from the donor’s death

y o u n g a d u lt

|

kirkus.com

|

fiction

|

15 january 2019

|

11

Fifteen sharp and cutting short stories. not everyone is special

resisting the compromises his increasing success demands, his “mental life simmering carefully like milk over a fire.” A life like Mauro’s is forever uncertain, the story suggests, but sweetened by an endless cookbook’s worth of options. Too short to feel like a full-bodied novel but an admirable literary lagniappe.

sad sacks and beautiful losers you find in American fiction from Steinbeck to Bukowski. The opener, “Too Late for a Lot of Things,” resembles Sedaris’ infamous “Santaland Diaries,” if the smallish person at Santa’s Workshop were meaner and tormented by heartland hicks instead. Denslow clearly likes flash fiction, and you find it in ultrashort pieces like “My Particular Tumor,” which recalls the narrator’s obsession with his organs in Palahniuk’s Fight Club, and “Bio,” which chronicles the sad bylines of a writer in a failing marriage. Palahniuk’s underground echoes again in “Punch,” which imagines that citizens are given a pair of federally mandated vouchers to legally pummel someone every now and again. The stories here are deeply grounded in everyday life, mostly among people who aren’t making very much of their days, but Denslow allows a touch of magical realism every now and again. In “Proximity,” our leading man can teleport. “It just hurts like a bitch,” though. Meanwhile in “Dorian Vandercleef,” a writer discovers that the subject of his novel is in fact writing the same book—in the first person. Finally, in the title story, a troubled youngster in a strange institute yearns to discover his secret power. Elsewhere, the specter of death hangs over stories in ways

NOT EVERYONE IS SPECIAL

Denslow, Josh 7.13 Books (160 pp.) $16.99 paper | Mar. 27, 2019 978-1-7328686-2-5

Fifteen sharp and cutting short stories from Austin-based writer Denslow. Denslow opens his debut collection by quoting a Tom Waits song, so it’s no surprise the characters within resemble the kinds of affable, sometimes-laughable

12

|

15 january 2019

|

fiction

|

kirkus.com

|

MIRANDA IN MILAN

both morbid and morbidly funny. The narrator of “Mousetrap” gives his running monologue of suicidal thoughts before an ironic accident saves his life. Another guy attends the funeral of a friend, albeit in hopes of getting laid. When a best friend dies in “Extra Ticket,” the survivor doesn’t know how to process his grief. A collection of heartfelt, deftly composed stories about the human condition.

Duckett, Katharine Tor (208 pp.) $14.99 paper | Mar. 26, 2019 978-1-250-30632-6 A sequel to The Tempest, with Miranda cast as the heroine, Prospero as the villain, and a Moorish witch as Miranda’s love interest. A thoughtful novelist might have taken this idea in many interesting directions. She might have tried to match the atmosphere of Shakespeare’s great romance, weaving a tale of spirits and enchantment. She might have cast a hard eye on history, examining the workings of patriarchy and colonialism in her 17th-century Italian setting. She might have probed Miranda’s psychology and that of her father. Or she might have explored a complex and sophisticated civilization through the eyes of an innocent seeing it for the first time. If

THE SPECTATORS

duBois, Jennifer Random House (352 pp.) $27.00 | Apr. 2, 2019 978-0-8129-9588-6

y o u n g a d u lt

A mass high school shooting prompts a reckoning for a controversial talk show host and those around him in duBois’ (Cartwheel, 2013, etc.) third novel. “He was Matthew Miller then,” remembers a man named Semi, the host’s lover in the 1970s, who knew him as an idealistic lawyer and then a candidate for mayor of New York. But in 1993, when The Mattie M Show publicist Cel is struggling to defuse reports that two high school boys who gunned down multiple classmates watched his show regularly, Mattie presides over a TV carnival of people confessing to “vices and depravities the average viewer didn’t even know existed.” The show’s evolution from a substantive public affairs program to a wildly popular venue for “rubbernecking and mayhem” is more explicable than Mattie himself, an empathetic interlocutor of the damaged and deranged on camera but a mystery to his staff off the air. Semi’s recollections of their affair and break-up intertwine with Cel’s story to create an atmospheric chronicle of New York’s bohemian gay subculture in the freewheeling 1970s, a keening depiction of the AIDS-stricken ’80s, and a poignant portrait of Cel, who got out of the rural working class via Smith but still lacks the self-confidence to claim—or even know—what she really wants. Mattie remains remote and enigmatic, even in his final encounters with Semi, which move him toward a fateful change of direction without readers ever really understanding him. This is not a fault but simply a given of duBois’ accomplished narrative, which ranges widely to investigate contemporary culture through the complicated human beings who inhabit it: Cel’s party-girl roommate and a judgmental pal from Smith, a predatory journalist, the TV show’s seen-it-all producer, and one of the shooters (via a scarily thoughtful letter to Mattie) are among the other characters sketched with acuity and perception. The ending respects Matte’s opacity but allows him to make some kind of amends to Semi, while Cel gets the fresh start she deserves. Elegant, enigmatic, and haunting.

|

kirkus.com

|

fiction

|

15 january 2019

|

13

INTERVIEWS & PROFILES

Karen Thompson Walker IN THE DREAMERS, A MYSTERIOUS EPIDEMIC PUTS INHABITANTS OF A CALIFORNIA TOWN TO SLEEP By Benjamin Rybeck Photo courtesy Dan Hawk

to fear just as a human being walking around, but as a writer I can channel some of what would otherwise be fear, because as a writer in a fictional universe, I’m controlling the story. What’s so frightening about real situations is that we don’t have control.” Not to suggest The Dreamers, Walker’s nimble and lyrical second novel, functions purely as horror, but it does borrow familiar tropes, using them to tell a much larger tale of connection and defamiliarization in an America that seems particularly post-2016. “I’ve always been interested in contagion stories,” Walker says. “There’s something clarifying about life-or-death situations—how certain parts of ordinary human life collide with the extreme.” Walker’s contagion takes the form of sleep: college students on one dormitory floor begin to nod off and then cannot wake up even though they still dream. Nobody knows why this is happening. The floor is quarantined. Outsiders—particularly a shy girl named Mei— fall under suspicion; students are shuttled to a detention center against their will. Elsewhere, cops and scientists roll in, as does the media (as in any good disaster). Others in the town harden themselves against their neighbors. They lock themselves away as survivalism takes hold. And that California air in this book, that California ground: so dry, so brittle. The Dreamers always hovers on the verge of smoke. Fire. Reading the above may have brought to mind images of recent history that seem particularly of our moment: California blazes, detention centers, suspicion of outsiders. “The way that I like to work,” Walker says, “is I come up with one fantastical element—this sleeping sickness—but after that I really want to set it in the real world.” (Her first novel, The Age of Miracles, also concerned disaster, albeit a more fantastical sort: the literal slowing of Earth’s rotation.) “Over time, as I’m writing, I’m always using things in our real world.” Let

Midway through Karen Thompson Walker’s The Dreamers (Jan. 15), a novel about a contagion that spreads throughout a California college town, she describes a lesson discovered at an inopportune moment: “…how disease sometimes exposes what is otherwise hidden. How carelessly it reveals a person’s private self.” Reading this, I found myself thinking of how horror—good horror, anyway—can operate in fiction, reaching out its fingers to flick on a lamp in an otherwise darkened basement. We see things in horror beyond the horror, and the scares are actually about something far deeper. “Sometimes I feel a little of my own fear,” Walker tells me over the phone one morning, “but I also think writing for me channels it. When I read the news, my imagination supplies details, and I’m quick to jump 14

|

15 january 2019

|

fiction

|

kirkus.com

|

this not sound like opportunism—rather, cognizance. She started writing this book well before 2016 (that year where something really did feel like it happened to Earth’s rotation—maybe not so fantastical after all) but certainly kept writing it afterward. “More than me trying to make a point about the state of our culture or world, I just want the book to feel real,” she says. Walker’s authorial eye seems to see everything and everyone in this book. “I didn’t ever want the same moment of the epidemic or outbreak to be told in two perspectives….I tried to make every chapter advance the story of the spreading disease while also revealing something new.” Like a contagion itself, I suppose—moving ever forward, the disease, and revealing frightening truths along the way, private truths—until something stops it or no one remains. Benjamin Rybeck is the author of a novel, The Sadness, and general manager of Brazos Bookstore in Houston.

y o u n g a d u lt

Duckett intended to do any of those things, her debut novel shows little sign of it. The characters lack depth, and the writing lacks magic. As the story begins, The Tempest is over, and Miranda has returned to her native Milan with her father before setting out for Naples to marry Ferdinand. Nobody seems to like her much in Milan except a witch called Dorothea, who was born in Marrakech but for some reason is working at the ducal palace as a maidservant. Miranda may have fallen for Ferdinand, but that was only because she hadn’t yet set eyes on the likes of Dorothea. (O brave new world!) Prospero storms around making pompous pronouncements and breaking his word: It turns out he never actually ditched his powers or drowned his books, and instead of forgiving his brother, the usurper Antonio, as he promised to do, he keeps him chained in the dungeon. Oppressive mysteries threaten vaguely. Miranda dreams of heaven: “Above her, the sky was endless and blue, a shade almost purpureal, cushioning flocculent clouds in its fathomless depths.” Thankfully, such almost purpureal prose is rare; for the most part Duckett sticks to unobjectionably pedestrian language. The novel fails to explore its promising premise in any depth. Shakespeare this ain’t.

BESOTTED

Duclos, Melissa 7.13 Books (246 pp.) $16.99 paper | Mar. 13, 2019 978-1-7328686-4-9 In this debut novel, two women experience life, love, and loss as expatriates in Shanghai. Sasha moved to Shanghai a few years ago to get away from her overbearing father. Liz arrives in China looking for something to shake up the predictability of her life. Both working at the same international school, Liz gratefully moves into Sasha’s spare room and the two become roommates, friends, and eventually lovers. They explore the expat community of Shanghai, a raucous group of English speakers that meet in bars every week to party and remind themselves they’re not alone, including Dorian, an architect and longtime acquaintance of Sasha’s who wants to put down roots. Liz, meanwhile, has made her own friend: Sam, a Chinese language-exchange partner who wants more from Liz than just help with his English. The book is told entirely from Sasha’s point of view, a kind of omniscient first person that takes a little bit of getting used to while also creating distance from the other characters, as the reader is unsure if they are getting an accurate picture of events or just Sasha’s thoughts on what might have happened. The relationship between Sasha and Liz, in theory the heart of the novel, is hard to connect to, as readers hear only one side of the story and many more anecdotes about fights and misunderstandings than moments of connection and love. The true star of this piece is the expat community that Duclos has perfectly |

kirkus.com

|

fiction

|

15 january 2019

|

15

drawn. Any expat who has spent an amount of time in Asia will find at least something in there that speaks to their own experience. The worldbuilding is excellent. Though the love story is a bit hollow, the parts about living as an expat in China ring true.

confessing to the murders of three young women, Vladimir is in prison, awaiting a harsh sentence; but Ilya is certain of his innocence, and although he is thousands of miles away, he sets out to prove it. Moving between the small town of Leffie, Louisiana, where Ilya is housed with the Masons, a pious, middleclass host family, and Berlozhniki, a former mining town where he shared a tiny apartment with his mother, grandmother, and brother, Fitzpatrick underscores the contrast between Western excess and Russian impoverishment. On the road to Leffie, Ilya whizzes past grocery stores—“the shelves were completely full,” he notices with amazement—video stores, pizza places, gas stations, and a huge building shaped like a pyramid with two glass walls: the evangelical Star Pilgrim Church, where the Masons worship every Sunday. Their house is sprawling, with foyers, a den, multiple bathrooms and bedrooms, and a heated outdoor pool that, Ilya is shocked to see, can be illuminated for night swimming. Of the Masons’ three daughters, only the sardonic Sadie, the eldest, seems to understand Ilya; as he soon discovers, she, like him, harbors secrets. He should not have been surprised, he reflects, “but his own secrets had made him myopic, made him forget that the world, even America, was a tangle of lives, all twisted and bent.” Ilya confides in Sadie, sharing his worries: Vladimir’s life, he reveals, is inexorably tangled. Unlike Ilya, who excelled academically, Vladimir struggled; he became a petty thief and drug addict, never keeping his promises that he would turn himself around. Beset with guilt, hoping desperately to save Vladimir, Ilya searches the internet for clues to the murders, and, with Sadie’s help, he discovers the corruption and betrayal that landed Vladimir in prison. An absorbing tale imparted with tenderness and compassion.

LIGHTS ALL NIGHT LONG

Fitzpatrick, Lydia Penguin Press (352 pp.) $27.00 | Apr. 2, 2019 978-0-525-55873-6

Devoted brothers, living a world apart, are enmeshed in a mystery. Making a poised, graceful literary debut, Fitzpatrick follows the aspirations and anguish of Ilya, a 15-year-old Russian exchange student who arrives in the U.S. burdened by worry about his older brother. After

GIRAFFES ON HORSEBACK SALAD

Frank, Josh with Heidecker, Tim Illus. by Pertega, Manuela Quirk Books (224 pp.) $29.99 | Mar. 19, 2019 978-1-59474-923-0 With help from comedian Heidecker (Tim and Eric’s Zone Theory, 2015, etc.) and illustrator Pertega, “pop-culture archaeologist” Frank (The Good Inn, 2014, etc.) adapts into a graphic novel a never-produced film collaboration between surrealist artist Salvador Dalí and classic-Hollywood absurdist Harpo Marx. The first 40 pages of this graphic novel are mostly straighttext exposition, detailing how Frank came to reconstruct the unproduced film and explaining the brief time Dalí and Marx spent together in mutual admiration. This sluggish start sets the stage for what is to come: an illustrated adventure that kicks off in 1930s New York but eventually engulfs the world, thanks to “the Surrealist Woman,” an enigmatic beauty with fantastical reality-altering powers. We first encounter her through visionary businessman Jimmy, who discovers an artistic self he never knew was inside him when the Surrealist 16

|

15 january 2019

|

fiction

|

kirkus.com

|

In a fantastical feminist adventure, three generations of women travel the world in pursuit of new opportunities. virginia woolf in manhattan

Woman arranges an otherworldly musical performance. As Jimmy and the Surrealist Woman fall in love, the happiness she feels triggers global chaos (the Great Pyramid floods, Venice runs dry, the streets of Paris suddenly all go in one direction). Jimmy’s vulgar, ambitious, unfaithful fiancee, Linda, becomes enraged by the attention the Surrealist Woman receives— both from Jimmy and from society—and rallies the forces of order to prosecute the Surrealist Woman. The story is a bit on the nose about freedom of expression versus societal oppression and expectation. Most enjoyable are Groucho and Chico Marx, who work on behalf of the Surrealist Woman; their playful, punny dialogue contrasts with the stiff exchanges between Jimmy and Linda or Jimmy and the Surrealist Woman. Pertega’s art shines in detailed close-ups and as the story delves deeper into surrealism (dripping wax effects, rivers of hair, complex page layouts), while the plainer scenes and more distant perspectives render the characters flat. An intriguing pop-culture artifact—more so for its background than its execution.

are usually solved by OWEN’s deus-ex-machina abilities. Kirklin and Laury are mostly ciphers, and not very interesting ones at that, but the banter between the drab Henry and the supercilious OWEN is worth the price of admission. A fun, relatively harmless comic thriller about the nature of cities, the threats of technology, and how to blow stuff up good.

VIRGINIA WOOLF IN MANHATTAN

Gee, Maggie Fentum Press (471 pp.) $15.95 paper | Mar. 28, 2019 978-1-909572-10-2 In a fantastical feminist adventure, three generations of women—including Virginia Woolf, back from the grave—travel the world in pursuit of new opportunities.

y o u n g a d u lt

THE MUNICIPALISTS

Fried, Seth Penguin (272 pp.) $16.00 paper | Mar. 19, 2019 978-0-14-313373-5 A bureaucratic bean counter and a snarky artificial intelligence team up to find a terrorist working to destroy America’s largest near-future city. Fried (The Great Frustration, 2011) offers a very weird debut novel that somehow manages to transport Conrad’s Heart of Darkness to a futuristic mega-city with a minimum of social satire but grand sociological observations about cities on the scale of Geoff Manaugh’s A Burglar’s Guide to the City (2016). Our Everyman hero is Henry Thompson, an efficiency expert with a murky government entity and, as one nemesis notes, “the biggest milquetoast bean sorter in the history of the United States Municipal Survey.” After a number of the agency’s facilities are bombed and its artificial intelligence platform is infected with a virus, Henry’s boss, Theodore Garrett, sends him to the futuristic city of Metropolis to hunt down the suspect. Henry’s partner in this venture is the aforementioned AI, OWEN, a harddrinking, newly sentient personality who manifests as a hologram but turns into a bulldog and faints at the sight of blood. These two unlikely partners are chasing Terrence Kirklin, their agency’s station chief in Metropolis, who has clearly gone rogue. Kirklin has disappeared with Sarah Laury, an 18-year-old Olympic gold medalist, playwright, genius, and, oh yeah, the daughter of the mayor of Metropolis. Fried can’t quite decide what he wants to play here—it’s too buddy-cop comic to be a hardcore thriller and too tongue-in-cheek about technology to be a serious social satire, but it’s still a fun read. The narrative is packed with irrelevant but fun-to-read set pieces including a gunfight in a museum, a couple of car chases, and a few deadlocks that |

kirkus.com

|

fiction

|

15 january 2019

|

17

A teenage boy finally gets to know his absentee father, but not until after the man has fallen into a coma. the book of dreams

“Suddenly there’s time again; & I’m in it,” declares Woolf, the internationally acclaimed literary modernist who committed suicide in 1941, now resurrected in 21st-century New York City due to a thunderstorm and the mental focus of another author and critic, Angela Lamb, who travels from London to the U.S. and then Istanbul to deliver a paper at a Woolf conference. Distinguished British author Gee (My Animal Life, 2011, etc.) doesn’t worry too much about the questions arising from her icon’s peculiar comeback; she just breezes forward, rather like the revivified Virginia herself, who becomes increasingly eager to embrace her second chance at life. First published in Britain in 2014, the novel is presented in overlapping conversations as Angela and Virginia explore their sudden relationship, which is variously tetchy, competitive, caring, and celebratory. Angela’s marriage to explorer Edward is failing, and she has parked her beloved teenage daughter, Gerda, at a boarding school in England for safekeeping during her own absence. But Gerda is being bullied at the school and decides to embark on a trip, too, to find her mother and possibly restore her parents’ relationship. Virginia and Angela, meanwhile, enjoy New York,

18

|

15 january 2019

|

fiction

|

kirkus.com

buying clothes, drinking at the Algonquin, and visiting the Statue of Liberty, while bickering over writing, privilege, time passing, and the problems of the book business. Moving on to Istanbul, the novel’s conversations and speculations intensify, as do its longueurs and intermittent feel of a travelogue. But the delivery of Angela’s conference paper, a rousing paean to Woolf, writing, and seizing the day, heralds a moving conclusion. An imaginative love letter to a literary hero is given vitality, depth, and charm through the playful intelligence of its seasoned author.

THE BOOK OF DREAMS

George, Nina Trans. by Pare, Simon Crown (400 pp.) $26.00 | Apr. 9, 2019 978-0-525-57253-4

A teenage boy finally gets to know his absentee father, but not until after the man has fallen into a coma. The story opens as Henri Skinner, a former war reporter, jumps into the Thames to save a young girl from drowning. After Henri labors back onto shore with the girl and releases her, he stumbles into oncoming traffic and sustains serious injuries. Henri’s son, Sam, is surprised and devastated to learn that at the time of the accident, Henri had been en route to a father-son event at Sam’s school. With a stellar IQ and a membership card to Mensa, Sam is hardly a typical kid. He’s also a synesthete, meaning his senses overlap in ways that allow him to perceive information through intense interconnected sensory experiences. Without informing his mother, Sam begins visiting Henri in the hospital daily, hoping to draw his father out of the coma he has fallen into. Sam grows acquainted with a slew of characters from the hospital, including a young girl named Maddie, who is also comatose, and Eddie Tomlin, the only woman who ever stole his father’s heart. As Sam’s visits continue, Henri’s prognosis looks increasingly bleak. Yet somehow, Sam feels himself bonding with his father in new and meaningful ways. Told from the alternating perspectives of Sam, Henri, and Eddie, the story contains many flashbacks, memories, and dream sequences as well as detailed tracking of Henri’s physical progress. Translated from George’s (The Little French Bistro, 2017, etc.) original German, the narrative moves at a gentle pace, often mimicking the repetitiveness that is borne of repeated visits to a sick room. The author uses Henri’s evolving mental state to explore possible states of existence and a shifting continuum of consciousness that occupies the spectrum between life and death. Although the story seems to stall at points, it raises interesting existential questions about the purpose and definition of life. Through the challenges and losses that each character endures, the author conducts an effective exploration of connections that transcend physical boundaries. A slow-moving but poignant story about longing, nostalgia, and the pain of missed opportunities. |

MALAWI’S SISTERS

death in his or her own sometimes-destructive way: Malawi’s father and mother, Malcolm and Bet, rely on substances to deal with their pain, while Malawi’s two sisters, Kenya and Ghana, are forced to confront the realities of their relationships with their romantic partners, their parents, Malawi, and each other. Several of the characters will be immediately recognizable to readers—the high-achieving but unsatisfied older sister, the hippie middle sister—and at times Hatter (The Color of My Soul, 2011) seems to want to shoehorn other storylines into the novel, such as the coming-of-age of Malawi’s nephew, Junior. Hatter does try to make her characters more than stock types, and she generally succeeds, weaving the events of the story with the characters’ pasts, unveiling their motivations, and encouraging readers to regard them with compassion, all while attempting to capture the energy of a larger social moment. But in an effort to seem evenhanded and tie a neat bow on an otherwise difficult and complicated story, Hatter defangs the movement she attempts to fictionalize and portray with respect. Though it’s a nice effort, Hatter falls short of giving Black Lives Matter the literary treatment it deserves.

Hatter, Melanie S. Four Way (320 pp.) $19.95 paper | Mar. 15, 2019 978-1-945588-30-3 A family’s attempts to cope with loss are complicated when their personal tragedy forms the seed of a larger movement. Malawi Walker, the youngest of three daughters of a prominent upper-middleclass black family from Washington, D.C., has recently moved to Florida to work as a teacher and be closer to a man she’s dating. On her way home after a long evening spent hanging out with a fellow teacher, Malawi crashes her car and, with no cellphone service to call for help, walks up to the home of Jeffrey Davies, a white man, who shoots her twice after she knocks on his door. When she succumbs to her injuries, the Walker family quickly unravels, each remaining member coping with Malawi’s

y o u n g a d u lt

|

kirkus.com

|

fiction

|

15 january 2019

|

19

CEMETERY ROAD

can’t compare to that of his long-dead violinist sister, Anna. In fact, the chain of vengeance goes back even further, since Cara’s grandfather Sergai Kaskov murdered Anna as payback for the time years earlier when Anna’s father and brother broke Kaskov’s finger bones in the gulag where they were imprisoned together because they feared him as yet another possible competitor in the days when she was still alive. Svardak succeeds in snatching Cara from her concert tour and hiding her out in the wilds of West Virginia as he cackles over the fate she’ll share with her most recent predecessor, violinist Marian Napier. Fortunately, Cara’s guardians, forensic sculptor Eve Duncan and Detective Joe Quinn of the Atlanta Police Department, and Michael, Eve’s preternaturally empathic 10-year-old son, are fully equal to the challenge of locating her before she can follow Niccolò Paganini and Jascha Heifetz into history. So for that matter is Cara herself, who’s so eager to consummate her recently professed love for Eve’s childhood friend Jock Gavin that she’s doubly watchful and resourceful in planning her escape. But restoring Cara to the bosom of her family is only one more chapter in the war declared by Svardak, who’s “crazy, not a ruthless sociopath,” as Joe helpfully observes, and who’s bent on eliminating everyone Cara loves before he returns to sweep her up again, this time for keeps, as a final tribute to his dead sister. The densely woven backstory, the oracular speeches, the elliptically motivated vendetta, and the constant recourse to near-supernatural powers all suggest that what Johansen (Vendetta, 2018, etc.) is writing is not a fairy tale for adults but a fairy tale with a mostly adult cast.

Iles, Greg Morrow/HarperCollins (752 pp.) $28.99 | Mar. 15, 2019 978-0-06-282461-5 Bad things are astir on the banks of the Big Muddy, hallmark territory for homeboy Iles (Mississippi Blood, 2017, etc.). “Buck’s passing seems a natural place to begin this story, because that’s the way these things generally start.” Yep. This particular bit of mischief starts when a Scoutmaster, surrogate father, and all-around good guy gets his head bashed in and his body dumped into the Mississippi. And why? That’s the tangled tale that Iles weaves in this overlong but engaging yarn. Thanks to the back-room dealing of a bunch called the Poker Club, the little river-bluff city of Bienville has brought a Chinese paper pulp mill to town and, with it, a new interstate connection and a billion dollars— which, a perp growls, is a billion dollars “in Mississippi. That’s like ten billion in the real world.” But stalwart journalist Marshall McEwan—that’s McEwan, not McLuhan—is on the case, back in town after attaining fame in the big city, to which he’d escaped from the shadow of his journalist hero father, now a moribund alcoholic but with plenty of fire left. Marshall’s old pals and neighbors have been up to no good; the most powerful of them are in the club, including an old girlfriend named Jet, who is quick to unveil her tucked-away parts to Marshall and whose love affairs in the small town are the makings of a positively Faulknerian epic. Iles’ story is more workaday than all that and often by the numbers: The bad guys are really bad, the molls inviting (“she steals her kiss, a quick, urgent probing of the tongue that makes clear she wants more”), the politicians spectacularly corrupt, the cluelessly cuckolded—well, clueless and cuckolded, though not without resources for revenge. As Marshall teases out the story of murder most foul, other bodies litter the stage—fortunately not his, which, the club members make it plain, is very much an option. In the end, everyone gets just deserts, though with a few postmodernly ironic twists. Formulaic but fun.

LOST ROSES

Kelly, Martha Hall Ballantine (448 pp.) $28.00 | Apr. 2, 2019 978-1-5247-9637-2 On the brink of World War I, three women fight internal battles on the homefront. Novelist Kelly (The Lilac Girls, 2016), who offered the perspectives of three women during World War II in her bestselling debut novel, turns back the clock to examine the lives of another female trio as the world enters the Great War. Connecting the two novels is Eliza Ferriday, the New York socialite with a heart for social justice, who is the mother of real-life Lilac heroine Caroline Ferriday. The book is a prequel, though it is a silk thread that binds the two stories. Eliza is enjoying the high life with her Manhattan and Southampton social set, making regular visits to Paris and St. Petersburg to sightsee with close friend and confidante Sofya Streshnayva as the world buzzes with talk of impending war. Eliza takes the threat more seriously than beautiful Sofya, a cousin of the Romanovs who, like most of her ilk, is living in a bubble of denial about the danger that lies ahead. When Sofya’s stepmother hires Varinka Kozlov, the daughter of a local fortuneteller, she unwittingly brings

DARK TRIBUTE

Johansen, Iris St. Martin’s (384 pp.) $28.99 | Mar. 26, 2019 978-1-250-07588-8 Think the competition among music students at Juilliard is fierce? Wait till you hear what the family of violinist Anna Svardak has done, and is prepared to do, to anyone they consider a rival. By the time John Svardak sets his sights on Cara Delaney, he’s already murdered four other violinists on both sides of the Atlantic because their music-making 20

|

15 january 2019

|

fiction

|

kirkus.com

|

y o u n g a d u lt

|

kirkus.com

|

fiction

|

15 january 2019

|

21

HOUSE ON FIRE

trouble into their home. Although young Varinka is a kind soul, her family is closely connected to a pair of local thugs leading Bolshevik uprisings against the bourgeoisie White Russians. Soon, Sofya’s family is caught in the crosshairs of a revolution, Eliza is powerless to help from New York, and Varinka must make a choice about where her loyalties lie. Though the writing is rich and vivid with detail about the period, the storytelling is quite a bit slower than in Kelly’s captivating debut, and both the plot and relationship development feel secondary to the historical scene-setting. A nuanced tale that speaks to the strength of women.

Kistler, Bonnie Atria (416 pp.) $27.00 | Mar. 12, 2019 978-1-5011-9868-7 A late-night fender bender exposes a family’s fault lines in Kistler’s domestic suspense debut. High school senior Kip Conley has been grounded since the state of Virginia suspended his license for operating under the influence, but tomorrow is Kip’s 18th birthday, and his father, Pete, and stepmother, Leigh, are out of town, so Kip borrows Pete’s truck and attends a house party. Just before midnight, Kip’s 14-year-old stepsister, Chrissy Porter, bursts in. Kip ignored her phone calls, so she biked through the rain to warn him that their parents are en route. Racing home, the kids swerve to avoid a dog and hit a tree. Although the damage is minimal, the truck is stuck, prompting a neighbor to call 911 and the police to arrest Kip, who has been drinking. Leigh hires her best friend from law school to defend Kip against what she presumes will be minor charges, but the next day, Chrissy suffers a fatal cerebral hemorrhage. Kip claims he’s innocent of manslaughter because, contrary to what he told the cops, Chrissy was driving when they crashed. Pete believes him, but Leigh accuses Kip of lying to save himself. Pete and Kip move out, and Leigh disappears into her job while investigators try to corroborate Kip’s account. Can the once “perfectly blended” clan survive the truth—whatever it may be? Subplots stemming from Leigh’s work as a divorce attorney tie into the central mystery and bolster the book’s narrative drive. Though Leigh’s maternal grief is palpable, she’s not the story’s sole focus; Kistler takes pains to explore the uniquely devastating ways in which the tragedy impacts Pete, Kip, and Chrissy’s other surviving relatives. Evocative writing and wholly realized characters complement a multifaceted tale that’s both harrowing and profound.

THE CONVICTION OF CORA BURNS

Kirby, Carolyn Dzanc (344 pp.) $16.95 paper | Mar. 19, 2019 978-1-945814-84-6 Kirby’s assured debut depicts the travails of a displaced daughter in Victorian England. Born to Mary Burns, a prisoner in Birmingham Gaol, infant Cora Burns is consigned to the local workhouse. She grows up there, makes one friend, Alice Salt, and excels at school, but then Alice drives her to commit a terrible crime. Her youth excuses her from prosecution, and at 16, Cora is sent to work at a nearby asylum, not knowing her mother is committed there. Like her mother, Cora has a child out of wedlock and is confined in Birmingham Gaol. Her child is also removed by authorities. This is only one of many parallels in Kirby’s multilayered narrative of grim coincidence, origin mysteries, and severed pairs, symbolized by the half medal Cora wears around her neck. Cora is determined and resourceful due to the hardships of her upbringing, but she is also capable of rage, which she mostly keeps contained—except on those unpredictable occasions when she doesn’t. Thomas Jerwood, the master of the house where Cora, upon release, is referred as a housemaid, is an amateur scientist whose treatises on nature and nurture appear every few chapters. Mrs. Jerwood is a bedridden madwoman who, when she spots Cora, upbraids her by another name, Annie. Meanwhile, Dr. Farley, resident physician at the asylum, is attempting to treat Mary Burns with hypnotherapy. His scientific observations are also interspersed in the narrative. Jerwood’s young ward (and guinea pig), Violet, befriends Cora but at times seems unusually distant, her appearance and accent slightly altered. The convoluted plot promises a thematic bombshell that never drops, although a Marxist gloss is attempted. Kirby makes no concessions to sentimentality even at the risk of alienating readers with an unappealing protagonist: Cora’s personality approaches the sociopathic as she guiltlessly exploits those around her. Still, the language is atmospheric and perfectly pitched, and the dialogue is spare and evocative. An ambitious effort that, despite its imperfections, will keep readers riveted. 22

|

15 january 2019

|

fiction

|

kirkus.com

THE SECRETARY

Knight, Renée Harper/HarperCollins (304 pp.) $26.99 | Feb. 12, 2019 978-0-06-236235-3 Having served her powerful employer at the expense of all else, a devoted secretary finds herself a pawn in her boss’s ruthless game—a betrayal that comes with consequences. Reliable and conscientious to a fault, Christine Butcher is hired as secretary and personal assistant to Mina Appleton just as Mina is coming into power, having gently ousted her aging father from the family business. And so it is that Christine finds herself the right-hand woman to the new |

y o u n g a d u lt

|

kirkus.com

|

fiction

|

15 january 2019

|

23

the weight of a piano is a gentle meditation on the healing power of art—and its limitations Chris Cander got the idea for her new novel, The Weight of a Piano (Jan. 22), when she heard about someone trying to give away a piano. Intrigued by the predicament, she asked for more details and was inspired to write a story about Clara, a young woman whose father gave her a piano and, very soon after, died. It’s not unusual for people whose parents have passed away to feel the enormous weight of that absence, but for Clara, that emotional weight is matched by the weight of that piano. Clara, who received the piano as a child, grows up to have a way with car engines but not much of a musical ear. The piano, with all Chris Cander its hassle and expense, carries with it Clara’s complicated feelings about her father and his expectations in giving it to her. It’s all she has left of him, but that doesn’t make it easy to deal with. Little does Clara know, the piano has a long history, one that intersects with hers in ways she can’t imagine. Alternating chapters tell the story of Katya, one of the piano’s previous owners, a gifted Russian pianist whose life was marked by heartache but who found endless joy in her music. But just because the piano came into Clara’s hands, does that make her responsible for all that weight, emotional and physical? What does it mean to respect the history of someone or something else without taking responsibility for that history? “Just exploring [that question] made me feel better,” says Cander. “That speaks to a much broader set of concerns than just physical possessions; it speaks of cultural importance and social importance.” Ideas, experiences, and even physical objects draw people together. “Being respectful of that thread, that connection, is what makes us human.” —C.E.

Photo courtesy Lauren Volness

chair of Appleton’s Supermarkets, a chain that was once “synonymous with fair trade and good practice”—principles that don’t much interest Mina. Petite and polished—a media darling who charms the country on national TV—Mina demands total allegiance, and Christine, a workhorse who prides herself on absolute discretion, is only too happy to oblige. Catering to Mina becomes not just her duty, but her obsession; Christine serves Mina first and always, at the expense of her own family. “We flourished together, Mina and I,” explains Christine. “She, undoubtedly, the dominant species. I, like a woodland plant, able to blossom in her shade. I was good groundcover, you might say.” When Mina’s business practices become the subject of a legal investigation, Christine is there—good groundcover— assisting her, making moves that will reroute the course of her own life. “I made some questionable choices,” she reflects ominously in the novel’s opening pages. “Choices I suspect many would have made in my position.” But the power dynamic will shift: Christine, the silent, watchful secretary, will not allow Mina’s betrayal to go unpunished—no matter the personal cost. Mina and Christine—neither quite fleshed out—seem to exist only in relation to one another; this is not a book about character but about mutual destruction. This gives the novel a somewhat flimsy quality, but what it lacks in substance it makes up for with style. Knight lays it on thick, foreshadowing the violence to come early and often, giving the book an over-the-top gothic quality; not subtle but an awful lot of fun. A cinematic page-turner steeped in atmosphere and just awaiting its adaptation to miniseries.

OKSANA, BEHAVE!

Kuznetsova, Maria Spiegel & Grau (272 pp.) $26.00 | Mar. 19, 2019 978-0-525-51187-8

Uprooted at age 7 from her home in the Ukraine as her family immigrates to the U.S. and a new life, Oksana Konnikova grows up permanently seeking her place in the world. Tragicomic and bittersweet, Kuznetsova’s debut treads the not-unfamiliar ground of immigrant alienation. Oksana’s biography from infanthood to her 30s, delivered in snapshot chapters that can seem like short stories, is the tale of a smart, rebellious outsider for whom family is the only constant. Oksana’s first American home, which she shares with her mother, father, and cougar grandmother, is a crummy apartment in Florida where she begins both the business of assimilation and a habit of impulsive, questionable behavior. From here on, the story is dotted with relationships explored, boundaries tested, and a roller-coaster home life, all infused with Ukrainian and Russian culture that Oksana has scarcely known firsthand. Girlfriends, boyfriends, college, work, relocation from New York to the West Coast follow, and all the while Oksana—the darkly comic outsider with an urge to write—is yearning: “I wrote about how much my grandmother loved returning to the

Chelsea Ennen is an editorial assistant.

24

|

15 january 2019

|

fiction

|

kirkus.com