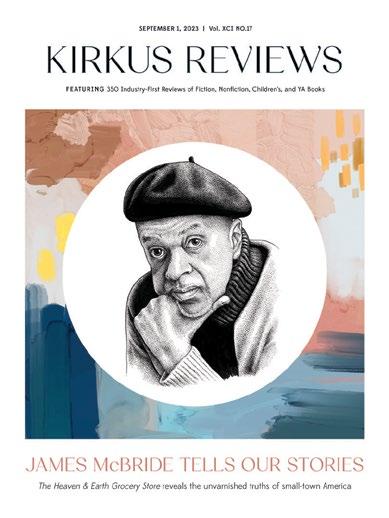

FEATURING 309 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s, and YA Books

QUESTLOVE IS THE PROFESSOR OF HIP-HOP

Class is in session with the award-winning musician and author of Hip-Hop Is History

FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK

FEATURING 309 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s, and YA Books

Class is in session with the award-winning musician and author of Hip-Hop Is History

FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK

ALAS, THERE’S NO European vacation in the cards for me this summer, and I’ll be watching the Summer Olympics on TV from the comfort of my couch in Brooklyn. But four new books offer the vicarious thrill of a Paris sojourn, all focused on outsiders who find themselves both entranced and bewildered by the City of Light.

Chicago native Jane Bertch arrived in Paris in 2006, not on a vacation or a journey of self-discovery but for a banking job. As she recounts in The French Ingredient: Making a Life in Paris, One Lesson at a Time (Ballantine, April 9), it took a while to assimilate in this rule-bound city— partly with the help of co-workers and a French

boyfriend—and then to realize that her true calling was the founding of a French cooking school. La Cuisine was conceived as a haven for “aspiring home cooks looking to sharpen their skills while meeting likeminded people.” Our reviewer calls it an “inspiring story that will appeal to foodies and budding entrepreneurs alike.”

Ruth Reichl—legendary restaurant critic, magazine editor, and author—is a real foodie, of course, but in her second novel she sends a fictional character named Stella St. Vincent to Paris in 1982 for an education in dining, fashion, romance, and other of life’s pleasures. Our critic found the plot of The Paris Novel (Random House, April 30)

Frequently Asked Questions: www.kirkusreviews.com/about/faq

Fully Booked Podcast: www.kirkusreviews.com/podcast/

Advertising Opportunities: www.kirkusreviews.com/book-marketing

Submission Guidelines: www.kirkusreviews.com/about/publisher-submission-guidelines

Subscriptions: www.kirkusreviews.com/magazine/subscription

Newsletters: www.kirkusreviews.com

For customer service or subscription questions, please call 1-800-316-9361

“wildly overcaffeinated,” and the characters “not even close to real people,” but the writing about food and wine, unsurprisingly, to be “almost worth the price of admission.” Plus, as she recently revealed on the Taste podcast, every meal that Stella eats in the novel is based on one that Reichl herself has experienced in Paris over the years.

Simon Kuper, a U.K. journalist, came to Paris in 2001 and bought a flat for £60,000 with plans to crash for a few weeks and then rent it out. Instead he wound up staying on, marrying an American woman, and raising two children. Impossible City: Paris in the 21st Century (PublicAffairs, June 4) is his perceptive and droll account of life there, puzzling over the rigidly insular ways of the locals and delighting, as one must, over the food and drink. He also had a front-row seat to the Covid-19 pandemic as it unfolded in “the world’s most compact city.” Our

reviewer calls it “an enjoyable, balanced read.”

The title of Glynnis MacNicol’s I’m Mostly Here To Enjoy Myself: One Woman’s Pursuit of Pleasure in Paris (Penguin Life, June 11) says it all: It’s August 2021, and the 46-year-old author has fled New York after a year of pandemic-enforced solitude to find romance— or at least sex—during a four-week stay in the French capital. It’s not her first such visit; she’ been coming every year for several years and has gathered around her a gang of single women friends (think Sex and the City) who encourage her to download the dating app Fruitz, where MacNicol creates a “watermelon” profile: “no seeds attached.” Our critic calls it a “fun memoir filled to the brim with humor and vulnerability.”

ISBN: 978-1-964428-00-0 [paperback]

ISBN: 978-1-964428-01-7 [eBook]

DISCOVERING JELLYFISH HAVE EYES IS A LIFELINE FOR NATIONALLY RECOGNIZED SCIENTIST RICARDO SZTEIN. UNMOORED BY HIS WIFE’S DEATH AND TRAPPED BY BUREAUCRACY, THE AMBITIOUS SCIENTIST RECKLESSLY SEEKS MEANING IN A MEANINGLESS DISCOVERY.

OR IS IT? COMPELLED TO PROVE ITS VALUE AND ALLEVIATE HIS GUILT, RICARDO IS BLIND TO THE PERILS OF HIS PURSUITS.

“Ricardo Sztein is an unforgettable character, and this story is de��nitely a winner.”

—Robert Bausch, Author of A Hole in the Earth

“In this original and provocative combination of science and ��ction, Joram Piatigorsky brings to life evidence of Dr. Johnson's observation that Truth can be made more accessible when draped in the robes of Fiction.”

—Warren Poland, MD, Psychoanalyst, & Author of Melting the Darkness

All

Co-Chairman HERBERT SIMON

Publisher & CEO

MEG LABORDE KUEHN mkuehn@kirkus.com

Chief Marketing Officer

SARAH KALINA skalina@kirkus.com

Publisher Advertising & Promotions

RACHEL WEASE rwease@kirkus.com

Indie Advertising & Promotions

AMY BAIRD abaird@kirkus.com

Author Consultant

RY PICKARD rpickard@kirkus.com

Lead Designer KY NOVAK knovak@kirkus.com

Kirkus Editorial Senior Production Editor

ROBIN O’DELL rodell@kirkus.com

Kirkus Editorial Senior Production Editor

MARINNA CASTILLEJA mcastilleja@kirkus.com

Kirkus Editorial Production Editor ASHLEY LITTLE alittle@kirkus.com

Copy Editors

ELIZABETH J. ASBORNO BILL SIEVER

Magazine Compositor

NIKKI RICHARDSON

Contributing Writers

GREGORY MCNAMEE MICHAEL SCHAUB

Co-Chairman

MARC WINKELMAN

Editor-in-Chief TOM BEER tbeer@kirkus.com

President of Kirkus Indie CHAYA SCHECHNER cschechner@kirkus.com

Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU eliebetrau@kirkus.com

Fiction Editor

LAURIE MUCHNICK lmuchnick@kirkus.com

Young Readers’ Editor

LAURA SIMEON lsimeon@kirkus.com

Young Readers’ Editor MAHNAZ DAR mdar@kirkus.com

Editor at Large MEGAN LABRISE mlabrise@kirkus.com

Senior Indie Editor DAVID RAPP drapp@kirkus.com

Indie Editor ARTHUR SMITH asmith@kirkus.com

Editorial Assistant NINA PALATTELLA npalattella@kirkus.com

Indie Editorial Assistant DAN NOLAN dnolan@kirkus.com

Indie Editorial Assistant SASHA CARNEY scarney@kirkus.com

Mysteries Editor THOMAS LEITCH

Alana Abbott, Colleen Abel, Autumn Allen, Stephanie Anderson, Jenny Arch, Kent Armstrong, Heather Rose Artushin, Mark Athitakis, Diego Báez, Colette Bancroft, Audrey Barbakoff, Robert Beauregard, Heather Berg, Kazia Berkley-Cramer, Elizabeth Bird, Amy Boaz, Jessie Bond, Melissa Brinn, Jessica Hoptay Brown, Cliff Burke, Jeffrey Burke, Tobias Carroll, Sandie Angulo Chen, Alec B. Chunn, Amanda Chuong, K.W. Colyard, Rachael Conrad, Jeannie Coutant, Michael Deagler, Cathy DeCampli, Dave DeChristopher, Elise DeGuiseppi, Amanda Diehl, Steve Donoghue, Anna Drake, Jacob Edwards, Lisa Elliott, Lily Emerick, Chelsea Ennen, Jennifer Evans, Joshua Farrington, Katie Flanagan, Hillary Jo Foreman, Mia Franz, Jenna Friebel, Jackie Friedland, Roberto Friedman, Nivair H. Gabriel, Omar Gallaga, Laurel Gardner, Carol Goldman, Amy Goldschlager, Melinda Greenblatt, Valerye Griffin, Vicky Gudelot, Tobi Haberstroh, Geoff Hamilton, Sean Hammer, Alec Harvey, Mara Henderson, Katrina Niidas Holm, Natalia Holtzman, Abigail Hsu, Julie Hubble, Ariana Hussain, Kathleen T. Isaacs, Wesley Jacques, Betsy Judkins, Jayashree Kamblé, Ivan Kenneally, Lyneea Kmail, Alexis Lacman, Megan Dowd Lambert, Carly Lane, Christopher Lassen, Tom Lavoie, Judith Leitch, Maya Lekach, Elsbeth Lindner, Coeur de Lion, Sarah Lohmann, Barbara London, Karen Long, Patricia Lothrop, Mikaela W. Luke, Wendy Lukehart, Douglas MacLeod, Joan Malewitz, Thomas Maluck, Joe Maniscalco, Collin Marchiando, Emmett Marshall, Gabriela Martins, Matthew May, J. Alejandro Mazariegos, Kirby McCurtis, Jeanne McDermott, Dale McGarrigle, Kathie Meizner, Carol Memmott, J. Elizabeth Mills, Cristina Mitra, Sabrina Montenigro, Clayton Moore, Andrea Moran, Rhett Morgan, Theo Munger, Jennifer Nabers, Christopher Navratil, Liza Nelson, Mike Newirth, Therese Purcell Nielsen, Sarah Norris, Katrina Nye, Tori Ann Ogawa, Mike Oppenheim, Emilia Packard, Derek Parker, Sarah Parker-Lee, Hal Patnott, Alea Perez, John Edward Peters, Justin Pham, Jim Piechota, Vicki Pietrus, William E. Pike, Shira Pilarski, Margaret Quamme, Kristy Raffensberger, Kelly Roberts, Amy Robinson, Roberto Rodriguez, Lizzie Rogers, Kristina Rothstein, Lloyd Sachs, Bob Sanchez, Keiko Sanders, Caitlin Savage, Meredith Schorr, Gretchen Schulz, Gene Seymour, Jerome Shea, Madeline Shellhouse, Sara Shreve, Sadaf Siddique, Maia Siegel, Karyn N. Silverman, Linda Simon, Jennifer Smith, Margot E. Spangenberg, Allison Staley, Allie Stevens, Sharon Strock, Mathangi Subramanian, Jennifer Sweeney, Deborah Taylor, Paul Teed, Eva Thaler-Sroussi, Renee Ting, Lenora Todaro, Laura Villareal, Christina Vortia, Audrey Weinbrecht, Vanessa Willoughby, Kerry Winfrey, Marion Winik, Jean-Louise Zancanella, Jenny Zbrizher

THERE’S A VARIETY of appealing books coming out this month, but none more topical than Rufaro Faith Mazarura’s Let the Games Begin (Flatiron, July 9), a debut novel set during the Summer Olympics—here being held in Athens, not Paris. Olivia Nkormo and Ezekiel Moyo, both children of Zimbabwean immigrants to Britain, are fulfilling their Olympic dreams—Olivia as an intern and Zeke as a sprinter—when they meet extremely cute and begin a romance. According to our

starred review, “This layered story expertly captures the excitement of the Games while Olivia and Zeke’s developing relationship…serves as a prompt for personal reflection.… This delightful romance is a ray of sunshine.”

For a more astringent take on relationships, try Sarah Manguso’s Liars (Hogarth, July 23), the story of a spiky and difficult marriage. Jane, the narrator, is a writer, and her husband, John, is a visual artist who’s competitive with her. “The tone reflects a kind of bitter

self-resentment that an intelligent and self-possessed feminist has been roped into a conventional, sexist gender role,” according to our starred review. “A bracing story of a woman on the verge.”

a dragon’s hoard—and is later convinced to go back and actually rob that same dragon. Our starred review calls it “a soaringly good read.”

Following the success of Long Bright River (2020), Liz Moore returns with The God of the Woods (Riverhead, July 2), set in 1975 at an Adirondacks sleepaway camp called Emerson. Barbara Van Laar is a 13-year-old camper there, and her family also owns the place, so it’s particularly shocking when she’s discovered missing from her bed one morning—especially considering that her older brother disappeared from Emerson many years before. “As rich in background detail and secondary mysteries as it is, this ever-expansive, intricate, emotionally engaging novel never seems overplotted,” says our starred review. “Every piece falls skillfully into place and every character, major and minor, leaves an imprint.”

Jenn Lyons’ The Sky on Fire (Tor, July 9) is both a fantasy and a heist novel, a fun combination. Set in a world where dragons are as intelligent as humans, the book follows Anahrod Amnead, who was falsely accused of stealing from

If you’re looking for an immersive saga to last all summer (or at least for your entire vacation), check out Lev Grossman’s The Bright Sword (Viking, July 16), which spends 688 pages exploring the question of what happened to the Round Table after King Arthur died—along with most of the knights whose names you know. “Astoundingly, a fresh take on an extremely well-trodden legend,” according to our starred review.

Ten years ago, Dinaw Mengestu was a finalist for the first Kirkus Prize with All Our Names , and I’ve been looking forward to his next book ever since. Now he returns with Someone Like Us (Knopf, July 30), in which Mamush, a journalist who’s covered conflicts around the world, is pulled between his wife and young son in Paris and an exploration into the life of his father, Samuel, who’s recently died in the U.S. Our starred review calls it “a beguiling tale, fluently told and closely observed, that conceals as much as it reveals.”

Laurie Muchnick is the fiction editor.

A woman infiltrates a cabal of French radicals. Will she go native?

The narrator of Kushner’s fourth novel goes by Sadie, though her real name—like much of her identity—is clouded in mystery. She works undercover to undermine environmental activists, formerly for the U.S. government, but since a case went sideways, she’s gone freelance. Now, she’s been commissioned by unnamed “contacts” to disrupt the Moulinards, a small farming cooperative in southwestern France protesting a government effort to construct a “megabasin” to support large-scale corporate farming. The Moulinards’ leader, Bruno, is an “anti-civver,” skeptical not

just of capitalism but of the entire human species. (His writings—he exists largely in the form of email dispatches—argue that Neanderthals might have been better adapted for the planet.) Sadie has an arsenal of tools to monkey-wrench the monkey wrenchers—a willingness to exchange sex for access, a knack for languages and hacking, well-made cover stories, fake passports— but her work among the Moulinards stokes her own identity crisis. As she enters their world, she processes their enthusiasm, their philosophy (there are abundant references to critic Guy Debord), and their paranoia, which escalates as a national minister plans a visit to the region, upping the stakes.

Creation Lake

Kushner, Rachel | Scribner | 416 pp.

$29.99 | Sept. 3, 2024 | 9781982116521

As if echoing Bruno’s concern, Sadie is such a slyly clever human that she’s undermining her own humanity. Sadie is similar to Kushner’s earlier fictional protagonists— astringent, thrill-seeking, serious, worldly—but here the author has tapped into a more melancholy,

contemplative mode that weaves neatly around a spy story. Nobody would mistake it for a thriller, but Kushner has captured the internal crisis of ideology that spy yarns often ignore, while creating an engaging tale in its own right.

A deft, brainy take on the espionage novel.

VILLA E

Villa E

Alison, Jane | Liveright/Norton (160 pp.)

$23.99 | Aug. 6, 2024 | 9781324095057

A Modernist architectural masterpiece on the coast of southern France is at the center of a clash between two designers of genius—one widely celebrated, the other not so much.

Modeled on historical fact, Alison’s new novel is a twin bio-fiction tracing the connections and conflicts between 20th-century icon Le Corbusier—here named Le Grand—and Irish architect Eileen Gray, referred to only as Eileen. In 1925, when she was 40 and living in Paris, where she had a shop selling furniture she designed, Eileen traveled south and fell in love with a piece of coastal land. There, encouraged by her lover, Bado, she built the structure she’d been yearning to design, “a house that was intimate and modern but not a machine.” (Le Grand famously asserted, “A house is a machine to live in.”) Not a French citizen, Eileen couldn’t purchase the land herself, instead buying it in Bado’s name, which would be her downfall. The “slim white house, moored like a yacht, modern in the ancient sun,” is a triumph, but Bado makes it his own, eventually forcing Eileen to move on and design a second home in the hills. Le Grand becomes a frequent visitor to the coastal house, acknowledging its genius but seeing his influence in it:

“That genius and his own primary genius here mingled to make this villa. Masculine spirit meeting feminine

form.” Breaching the villa’s purity, he paints sexual murals on its white interior walls, which, because of his reputation, cannot be expunged. The novel explores the characters and lifelong achievements of both figures: he protean, domineering, and unrepentant; she sensual, committed, enduring. Looping, impressionistic, and atmospheric, narrated in retrospect from both characters’ points of view, the book offers more psychology than plot, but does so persuasively. A remarkable gender parable filtered through a sophisticated imagination.

Angoe, Yasmin | Thomas & Mercer (396 pp.) $28.99 | Aug. 1, 2024 | 9781662508332

In a dramatic change from Angoe’s trilogy about professional assassin Nina Knight, a disgraced daughter returns to her South Carolina family to find that it’s in even bigger trouble than she thought.

Jacinda Brodie has already had quite the day before she learns of her beloved grandfather’s heart attack. Conrad Meckleson, her ex-mentor and ex-lover, has persuaded the D.C. college where she’s a teaching assistant to deny her a research fellowship she thought was in the bag. And he’s landed a fat contract for a book he hopes will return him to bestseller lists, a story based on family secrets she confided in him, the most shocking of which is that Jac pushed her father, Brook Haven police chief Montavious Brodie Jr., over a cliff to his

death. Resolved that her story is hers alone, Jac lets herself into Meckleson’s place, packs up the notes he’s taken over the years, and dashes off a series of bridge-burning emails to the college administrators on her way out the door. Back home in Brook Haven, things are even worse. Her grandfather, Montavious Brodie Sr., the only family member who hasn’t judged Jac harshly, dies shortly after her arrival, leaving her to solace herself with old school friends Sawyer Okoye, now an administrator for the police, and Nicolas Tate, the mayor’s son. Jac instantly takes against Faye Arden, the mayor’s pushy fiancee, who’s renovating the notorious Murder Manor, where the caretaker reportedly killed over a dozen victims 50 years ago, into Moor Manor. Her granddad’s heart attack, Jac decides, was engineered by Faye. Just in case the enmity between the two women isn’t fierce enough, Meckleson pops up to accuse Jac of theft.

Endless skeletons in the family closet, all disclosed by a protagonist who makes one reckless move after another.

Anthony, Jessica | Little, Brown (144 pp.) | $18.99 paper July 30, 2024 | 9780316576376

Can the secrets and misdeeds of a marriage be survived?

The events of an unseasonably warm Sunday in November provide the backdrop for Anthony’s short, no-holds-barred account of a crucial juncture in the married life of a young couple in 1950s Delaware. As Sputnik 2 and its crew—the doomed “space dog,” Laika—orbit the earth, Kathleen and Virgil Beckett are on a collision course of their own. While Virgil brings the couple’s two boys to church and looks forward to squeezing in one more late-season round of golf, Kathleen dons an old bathing suit and proceeds to their

(somewhat depressing) apartment complex’s pool; the only unusual aspect of that sequence of events is Kathleen’s refusal to get out of the pool as the afternoon stretches into evening. Over the course of the day, Anthony deftly sketches out each character’s backstory and secrets. Virgil has relocated the family from Rhode Island to Newark, Delaware, for a fresh start and new job in the insurance industry in order to correct unacknowledged deficiencies (involving women and alcohol) in his behavior. Kathleen, who had been an accomplished college tennis player noted for her endurance, mulls over her past life and loves as she floats in the pool and decides upon the best tactic to employ in determining the future of her marriage. Complicating the couple’s relationship are external forces applied by parents, friends, and old (as well as fairly recent) lovers, but it will be up to Virgil and Kathleen to figure out how much to disclose to each other…once they’re on the same course. Anthony’s sharply focused portrait of seemingly average lives in midcentury America reveals the complexities of those lives in the course of one balmy day.

A novella packing all the imagery and storytelling power of a novel.

Auci, Stefania | Trans. by Katherine Gregor & Howard Curtis | HarperVia (416 pp.) | $18.99 paper

Aug. 27, 2024 | 9780063389151

Auci concludes her expansive saga of the Florios, a famous real-life family of Sicilian industrialists. Previous volumes (The Florios of Sicily, 2020; The Triumph of the Lions, 2024) traced the family’s fortunes from 1799 to 1893. This final installment in the saga finds the uber-successful family facing far less salubrious circumstances during the years 1894 to 1935 and concludes with an elegiac epilogue set in 1950. As

mounting debt and regional rivalries erode the value of the dynasty’s assets, Ignazio, feckless heir to the manufacturing, mining, fishing, and winemaking empire, faces business and political challenges beyond his ability to maneuver. Though he attempts to maintain some degree of control of the business, the Florios’ sumptuous lifestyle is threatened. At home, Ignazio’s often-neglected wife, Franca, suffers as a result of his womanizing and the pressure to produce a male heir in order to carry the dynasty forward. (Changes in attitudes about women’s roles may factor in here, too.) Replete with detailed descriptions of the family’s various homes, travels, and social engagements—and of Franca’s fabulous wardrobe and jewelry—the account plunges the once-fortunate clan into the devastation wrought by World War I. Cameo appearances by contemporary figures including Giacomo Puccini and various European royals keep the glitz factor high as Auci deftly conveys the family’s fall from grace. Gregor and Curtis have translated the novel from Italian while retaining some phrases in the original for effect. This is the final book in a trilogy that serves as the basis for the Hulu miniseries The Lions of Sicily, and it includes a summary of the historical events underlying the plot as well as a family tree helpful for identifying the Florios, many of whom share the same given names. A sweeping finale to a panoramic portrait.

Belardes, Nicholas | Erewhon (304 pp.)

$27.00 | July 23, 2024 | 9781645661290

Eco-horror arrives in Baywood, a small coastal California town. The students of Baywood High are uneasy and irritated. They gripe: “Now, all kinds of adults are pretending to die. Deading. That’s what we call it, have

been calling it, because, well, we’ve done it before, like more than a year before the adults ever thought to start their stupid version.” The kids deaded to make a point, but now something eerie is happening with the adults, “something completely unrelated. Something similar. Everywhere in Baywood, people lying on sidewalks and streets.” The chapters pivot among different perspectives to tease out what’s happening. Then an esoteric cult called the Risers appears amid the supernatural chaos to heighten anxieties about the current situation. The characters include Bernhard Vestinos, the owner of an oyster farm; Chango Enriquez, one of his employees; Chango’s teenage brother, Blas, an avid birder; Ingram Evans, an older birder; and Kumi Sato, Ingram’s friend. At a certain point, it’s hard to keep track of all the characters, though Chango and Blas are persistent standouts because of their relatable sibling interactions. The story is told from every possible point of view: Chapters from different third-person perspectives meld with a collective “we” that represents the teens of Baywood. One chapter uses the second person “you,” and several are told in the first person. Scientific information about oysters and birds is fascinating but eventually overtakes the plot. Blas and his fellow students are smart, cleareyed, sardonic, sometimes apathetic in a way that captures adolescence. They’re fed up with the adults’ lack of action in the important matters that caused them to “dead” in the first place: “We did it to make fun of ourselves. We did it because we die and it isn’t fair. You see, we’d already held GUN CONTROL rallies, BLACK LIVES MATTER rallies, EARTH DAY rallies. Those always got us nowhere. Adults don’t listen. We know that.” Admirably, these teen characters continue to place blame where it belongs.

An enticing premise and promising characters, but in desperate need of focus.

The hits just keep on coming. Be glad you’re a reader and not a character.

IF YOU TELL A LIE

Berry, Lucinda | Thomas & Mercer (271 pp.) | $16.99 paper

July 23, 2024 | 9781662512629

A series of anonymous notes threatening to disclose the secret four women have kept for more than 20 years brings them together again, this time to create additional havoc.

In their different ways, Blakely Garner, Thera Grey, Grace Howard, and Meg Watson had all been misfits. They bonded at Camp Pendleton, a place for gifted children, with Blakely as their natural leader. Trouble arrived, or was revealed, in the form of tennis coach Jared Crosby, whose good looks made Blakely think she could use an apparently compromising photo Meg took of the two of them to make Clint, a fellow camper, jealous. The prank succeeded beyond everyone’s wildest dreams, and not in a good way. Clint swiped and shared the picture, Crosby got fired, and by the time the dust settled, his wife, Regina, was convicted of stabbing him 117 times and attempting to kill their twin babies as well. Now, 26 years later, someone claiming to know the sordid truth behind the story has written all four ex-campers, pulling Thera away from her work as a psychic and spiritual counselor, Grace out of her orbit as a supermodel influencer, and Meg from her marriage to Claire to meet at the plush Houston home of Blakely. Regina, it seems, has been granted parole, and she’s obviously learned who pushed her over the edge into murder. Or maybe, since this is

another poisonous Berry special, that’s not so obvious after all, and the truth is even darker and more devious. The hits just keep on coming. Be glad you’re a reader and not a character.

Bieker, Chelsea | Little, Brown (336 pp.) $26.97 | Sept. 3, 2024 | 9780316573290

After receiving a letter from her incarcerated mother, a Portland woman’s shocking past comes crashing into her present. Granola mom Clove is doing her best to keep it together. She’s trying to wean her 3-year-old son, adjust to summer break with her school-age daughter at home, and grab a moment or two with her finance-world husband when he is finally able to hop off work calls. She soothes her anxiety with compulsive shopping, elaborate wellness regimes, and copious trips to the organic grocery store, “the safest place on earth.” She had thought that her lifestyle and having a family would help her escape a brutally traumatic childhood and grant her safety. But then one day, a letter comes from a California correctional center: Clove’s mother, Alma, convicted for the murder of Clove’s father after years of suffering harrowing physical abuse at his hands, has discovered Clove’s whereabouts. Alma is part of a #MeToo wave of women whose cases are being reevaluated, and she needs Clove’s eyewitness account of that night to be her path out of prison. Clove—who has told almost no one the truth of who she really

is—needs to make a decision: help Alma and expose her secrets to her present family or turn her back on her own mother. Bieker is trying a more conventional plot with her third book, stuffing this story in the container of a thriller when it doesn’t quite fit. But what Bieker has always been best at is creating female characters with vivacity and precision, and she does that again in Clove, painting an indelible portrait of what living with intergenerational trauma and a legacy of abuse can look like.

In the guise of a suspense story, Bieker delves into the heart of what it really means to survive violence.

Brew-Hammond, Nana Ekua

Amistad/HarperCollins (288 pp.)

$28.99 | July 9, 2024 | 9780062976734

A couple navigates marital troubles. The first novel for adults from author Brew-Hammond, set in the early 1970s, opens with 22-year-old Kokui Nuga celebrating the Christmas holiday at a hotel in Accra, Ghana. It is there that a server first catches her eye; when she comes back on New Year’s Eve, the two talk, and he introduces himself as Boris Van der Puye, who will soon head to the U.S. to attend a community college in Buffalo, New York. Despite the fact that his days in Ghana are coming to an end, the two date and fall in love, and Kokui also applies, and is accepted to, the school. Kokui’s father, Mawuli, isn’t thrilled with her decision; he wants his daughter to stay and work for his thriving paper company, but Kokui resists: “Leaving her father’s haunted house of disrespected women was the only plan she was clear on.” Her mother, a victim of Mawuli’s frequent philandering who has since moved to Togo, also urges caution, but Kokui and Boris marry and move to the U.S., first staying with Boris’ cousin in Brooklyn, then

moving to Buffalo for school. When things start to unravel and Kokui returns to Ghana after her father’s death, she starts to wonder whether she made a mistake, telling her mother that she feels “trapped by him. Like, if I push for something I need or tell him how I truly feel or show him who I truly am, I will spoil everything between us. And he lies, Ma.” Brew-Hammond’s prose and dialogue are workmanlike, but this tale of a garden-variety couple ultimately feels thin.

Brew-Hammond is talented, but there’s just not much here.

Cuadros, Gil | City Lights (220 pp.) | $17.95 paper | June 4, 2024 | 9780872869097

Poems and stories that capture a queer Chicano writer’s reckonings with illness, family, and desire in the midst of the AIDS epidemic.

Composed in the years before the 34-year-old Cuadros’ death from AIDS in 1996, the works in this collection are embodied and energetic, charged with the urgency of a young writer racing to mine and document as much of his experience as possible. In “Hands,” the opening story, an AIDS patient prepares for his death, finalizing his will and getting rid of his belongings, grappling with unresolved childhood memories. Though the narrator’s body is deteriorating and he’s certain he’ll die soon, life keeps shattering through the gloom: While gardening, he receives “a warm charge…from the earth,” and he befriends an immigrant woman named Yoli whose warm, maternal character disrupts the resentment he harbors toward his abusive parents. This tension between degeneration and life, and between the divine and the profane, pervades the collection. An HIV-positive queer man finds himself pregnant in “Birth,” one of the last stories the

author wrote. “Heroes,” which may have been the beginning of an unfinished novel, portrays moments of sexual intimacy as the narrator contends with the effects of illness and medical treatment on his body. Embodiment is vividly rendered throughout the pieces, especially in “Dis(coloration),” in which the narrator explores the cosmetics aisle of a drugstore and experiments with a new fading cream for his discolored skin. Spirituality is treated with equal importance, with speakers supplicating, grasping toward the divine in poems like “A Netless Heaven” and “It’s Friday Night and Jesus Is at the Laundromat.” Though there’s a brisk, unfinished quality to some of the stories (understandable, given the circumstances), this doesn’t overshadow their depth, detail, and poignancy. On the contrary, readers will easily recognize in these works a writer approaching the height of his powers. Brief essays by Justin Torres and Pablo Alvarez bookend the collection, contextualizing Cuadros’ life and writing.

A moving, necessary tribute to a singular voice of queer literature.

Deaver, Jeffery & Isabella Maldonado Thomas & Mercer (444 pp.)

$28.99 | Aug. 6, 2024 | 9781662518713

Deaver and Maldonado’s first collaboration pits a Homeland Security investigator and her former quarry against a ring of serial killers working their way through California.

Special Agent Carmen Sanchez snaps to attention when her kid sister, Selina, is attacked and nearly killed, saved only by the intervention of a luckless good Samaritan. The crime seems random, but Carmen and Prof. Jacoby Heron, a super-hacker expert on intrusion—what he calls “someone or something deliberately entering into a place or situation where they’re unwelcome or uninvited”—she once investigated,

soon link it to the very recent murder of real estate developer Walter Kemp in San Diego. The killer, identified to the sleuths by a spider tattoo on his wrist and to readers early on by the name Dennison Fallow, clearly has a plan that involves more victims, but what is that plan—and what does it have to do with cyberattacker Tristan Kane and the H8ers, a disgruntled group of men whose online whining about all the opportunities snatched away from them by the privileged few would make them pathetic if its consequences weren’t so lethal? Deaver evidently contributes the Chinese-box construction of the plot, in which the solution to each riddle seems to open new mysteries, and Maldonado provides a swiftly evoked sense of the characters’ social backgrounds. But it’s hard to tell which of them is responsible for the blistering pace, the numerous flashbacks to previous episodes that supply important details about the characters’ motivations at the cost of diluting that hard-won suspense, the stilted relationship between Carmen Sanchez and Jake Heron, or the sense of anticlimax that attends the last few revelations. A series seems inevitable. More a compromise than a synthesis, but nonetheless intriguing for all that.

Douglas, Claire | Harper/ HarperCollins (400 pp.) | $18.99 paper July 30, 2024 | 9780063277465

A novelist is beset by small harassments inspired by her books—and then the attention starts to escalate. Emilia Ward, author of the successful DI Miranda Moody series, has decided to kill off her beloved main character after 10 years, even though Miranda has brought her success and fame. As she works on the final drafts of Her Last Chapter, delving into the dark world of a serial killer, she begins to find small gifts and offerings on her doorstep—a broken seagull

figurine, a funeral wreath—that point to certain plot elements in the earlier Moody books. The police, of course, find little they can do, but Emilia feels more and more as if she’s not only being targeted, but also followed. Louise, a friend who’s on the force, is not directly involved in the investigation, but when Emilia’s teenage daughter, Jasmine, goes missing, Louise is immediately on the scene. Jasmine is found without incident, but the scenario clues in Emilia to a chilling truth: Only the people nearest and dearest to her could have orchestrated it, as it’s a plot point in her as-yet-unpublished novel. Could it be her ex-husband, now married to her ex-friend? Or her current father-in-law, himself a former cop? Or even Louise, who’s been acting strangely? As the sense of threat escalates, Emilia must confront a shameful secret as she tries her own hand at investigation. The novel mostly centers on Emilia, though there are occasionally chapters from the point of view of a female detective investigating a serial killer, and chapters concerning a girl named Daisy whose mother seems to have been murdered by this same killer. Will all the stories overlap? Yes, of course. There are an awful lot of characters and names to keep straight, but overall, the book is well constructed and paced.

Thoughtful, twisty, and tense.

Drager, Lindsey | Dzanc (212 pp.)

$17.95 paper | Aug. 13, 2024 | 9781950539970

Buses drive themselves, birds have disappeared, and you can’t see the stars: This spare and striking novel is what comes next.

“The Conglomerates conglomerate until all corporations become, essentially, one. The bus with no driver keeps making its loop, and the road that goes nowhere dead ends.” The faceless, soulless rhythms of an increasingly automated world shape our unnamed narrator’s daily existence,

after she’s informed that the bus she drove down Route 0 can now drive itself. She has lived in the same small town her whole life, and she’s cobbled together an eccentric family: her neighbor Uri; her dead father’s twin, Luce; the triplets she carried as a surrogate and kept after the intended parents died. This life isn’t exactly what she had hoped for. She’s had many dreams: to run away from town with “The Only Person [She’s] Ever Loved,” to become a radio astronomer, to hear the skylarks again, to see the stars. But the birds disappeared a long time ago, and the sky has been blank for just as long. This is the town’s new normal as it barrels toward The Crisis, which could be one thing, or “a series of crises, a web of crises different for every single person on this Earth.” But now, a series of strange occurrences may alter the town’s rhythms forever: Our narrator’s déjà vu is getting worse, making her feel as if she’s lived entire days before; jobs are disappearing as fast as strange nests are popping up; The Demonstration, a protest between YES and NO that has been going on for as long as anyone can remember, adds a new chant; a strange legend about the town—that it was mapped onto the solar system—leads the entire populace on a hunt for the truth. After she learns her late father’s theories on reality, our narrator is left to question the only world she’s ever known. What if she reversed the bus route she’s always driven? What if she went past the road’s dead end? What if she found a way to see the stars?

A speculative novel told in fragments peels back the surface of a small town’s reality.

Elias, Asha | Morrow/HarperCollins (272 pp.)

$28.00 | July 30, 2024 | 9780063312791

offered his dream job in Miami, they pack up their home in Wichita, Kansas, and move to a house zoned for “the best public elementary school in Florida.” The book opens as the family attends back-to-school night at Sunset Academy, and Melody is shocked to discover how different their new community is from the one they’ve left. Their daughter, Lucy, will be entering a school where mothers and children dress in astoundingly expensive (and revealing) designer clothing. Drinking and drugs are rampant among parents, and popularity seems tied to the size of a family’s donations. Initially intimidated by the fancy cars and tummy tucks, Melody is delighted when she makes friends with Darcy Resnick, who seems to share her down-to-earth sensibilities. It’s not long, however, before Charlotte Giordani, one of the queen bees, takes an interest in the new mom, and Melody starts getting caught up in everything she thought she hated. Unfortunately, she makes a misstep and quickly alienates Charlotte. Rather than slink into obscurity, Melody decides to run against Charlotte for PTA president, which will be either her only chance at redemption or the ultimate social suicide. While the story is entertaining from the start, the first several chapters describe the materialism of this Miami community in a tone that’s more angry than funny. The author devotes so much space to mocking the affluent Miamians that by the time the central conflict emerges, readers may have lost interest. Once the plot starts moving, though, the tensions between characters rise and the novel takes on a new heft. Deeper issues related to honesty, loyalty, parenting, and mental health emerge, each of which is examined with admirable grace and just the right touch of humor.

A woman struggles to find her place in a wealthy community full of social climbing and scandals. When Melody Howard’s husband, Greg, is

An ultimately satisfying tale about adult mean girls.

Ten

Emar, Juan | Trans. by Megan McDowell

New Directions (176 pp.) | $15.95 paper Aug. 13, 2024 | 9780811232074

A clutch of stories set in the author’s native Chile— and surrealist parts unknown. Originally published in 1937, this collection by Emar (18931964) arrived at the height of the Modernist movement; his eeriness and fluid, satirical approach to storytelling put him in league with better-known European and North American contemporaries. Indeed, his work seemed to anticipate the elliptical style that would make Borges world famous. These 10 stories are placed in a sensible sequence— “Four Animals,” “Three Women,” “Two Places,” and “One Vice”—but any concept of order is deceptive, as each story finds an unusual approach that sometimes only barely adheres to its supposed subject. “The Green Bird” concerns a taxidermic parrot the narrator received while living in Paris, but what starts as a cool remembrance of youth soon takes an absurd and violent turn. “Papusa” concerns a tsar holding court with a ghost, a jester, and the woman of the title—a scene the narrator observes through an opal on a ring. “The Hotel Mac Quice” centers on a man and his wife out for a stroll on vacation before becoming separated because of the man’s sudden urge to find his toothbrush. “The Unicorn” opens with a notice in the paper by a man who is looking for the safe return of “my best ideas and my purest intentions,” launching a satirical

trek to the Egyptian pyramids and Ethiopia, home to the mythical creature. Clearly, plot summary only goes so far; the best stories here thrive purely in Emar’s language, which can be richly synesthetic; “Damned Cat,” the most potent story here, starts with a nature walk that features stones that store heat, a weed that “smells of interplanetary distances,” and a cat observed with a peculiar geometric rigor. Veteran translator McDowell doesn’t attempt to make these stories adhere to logic, but they all possess a certain clarity—concerned with violence and loss, thoroughly sensual, but questioning what our senses tell us. Offbeat yarns from a sui generis author.

Fram, John | Atria (416 pp.) | $29.99 July 23, 2024 | 9781668031445

The sins of a televangelist and his kin come home to roost. When Toby Tucker and his sister were kids, their guardian, Uncle Ezra, made them spend four hours on the couch every Sunday watching The Prophecy Hour, a “glitzy, exuberant, overwhelming televangelism program” hosted by “America’s prophet,” fire-and-brimstone preacher Jerome Jeremiah Wright. Now, two-plus decades and a whirlwind courtship later, Toby is married to Jerome’s granddaughter Alyssa, and the couple are traveling to Hebron, Texas, with Toby’s 7-year-old son, Luca, to celebrate Alyssa’s 30th birthday at the Wright’s compound. Toby has never put any

A clutch of stories set in Emar’s native Chile—and surrealist parts unknown.

stock in Jerome’s predictions, but he is nevertheless unnerved to learn while en route that the man’s most recent broadcast ended with three grim warnings seemingly intended for Toby and Luca. Toby’s anxiety skyrockets when, just hours after they arrive, someone kills Jerome; a surprise storm of biblical proportions takes out the phone, internet, and access roads; and Luca starts seeing and conversing with an apparition he calls Mister Suit. Toby soon realizes the remaining Wrights are contriving to pin Jerome’s murder on him. Worse, once Toby is sidelined, Alyssa and her brother Richard have plans for long-haired, sparkle-loving Luca that start with a stay at a churchrun wilderness camp that destroys sweet, sensitive boys like him. The situation seems dire, but the Wright clan has no shortage of terrible secrets, and Toby won’t go down without a fight. By turns searing, soapy, and spine-tingling, Fram’s latest pays homage to Southern Gothic icons Michael McDowell and V.C. Andrews while also tipping its cap to modern horror great Jordan Peele. Though there’s a particular contrivance on which the plot leans a bit too heavily, that’s a minor quibble; exquisitely rendered, realistically damaged characters lend credence to myriad mad twists, propelling the tale from portentous start to pulse-pounding finish. Trenchant, terrifying fun.

Frazier, Soma Mei Sheng | Henry Holt (224 pp.) $27.99 | July 30, 2024 | 9781250872715

Mĕi Brown is a recent Dartmouth dropout working as a private chauffeur with a dodgy roster of clients— one of whom hires her to drive all the way across the country. When Mĕi picks up 20-something Henry Lee, she can’t help

The novelist expounds on suburbia, Jewish fiction, writing for TV, and more.

BY LAURIE MUCHNICK

TAFFY BRODESSER-AKNER made her name as a celebrity profiler, getting inside the heads of people like Gwyneth Paltrow and Tom Hanks and making them resemble humans instead of icons. With her first novel, Fleishman Is in Trouble , she proved she could do the same with fictional characters. Now she returns with Long Island Compromise (Random House, July 9), an even more ambitious and gripping novel set in the fictional town of Middle Rock, New York. BrodesserAkner, 48, lived on Long Island until she was 6, when her parents divorced and she moved to Brooklyn with her mother, visiting her father in Great Neck on the weekends. “I say I’m from Brooklyn, because it used to feel so braggy to say you’re from Long Island,” she reveals. “Though now it’s braggy to say you’re from Brooklyn.”

The book centers on the wealthy Fletcher family: Carl, who inherited a Styrofoam factory; his wife, Ruth; and their children, Nathan, Beamer, and Jenny. In 1980, Carl was kidnapped from their driveway and held for a week until Ruth paid a $250,000 ransom— most of which they never got back. Forty years later, the family gathers for the funeral of Carl’s mother, Phyllis, and it’s clear that all their lives have been deformed by the kidnapping.

I recently spoke to Brodesser-Akner by Zoom from her home on Manhattan’s Upper West Side; our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

to be a suburb and then became more and more its own place, its own ecosystem. I meet people from Long Island who are loath to leave, even for a weekend, if they don’t have to.

Is the book written about the Long Island in your head, or did you do research? Is Middle Rock based on a particular place?

Well, what did you do with all your education? You just returned to this place and perpetuated the same life you had

Colm Tóibín has a book out now called Long Island. Why is it a good title?

Because it’s a mythical place. First of all, I love

how many Long Islands there are. Is it fancy Long Island? Is it working-class Long Island? I don’t even know which Long Island I’m from. It was designed

Middle Rock—the closest you can call it is Great Neck. I didn’t do research, though I tried. The Great Neck library has a full-time historian, which is hilarious because I think the library down my street [in the city] is only open two afternoons a week. It’s pretty amazing the resources—in terms of schools and libraries— that kind of money gives you. And then my most judgmental parts are like,

One of the things I’m looking at in the book is the way we have not progressed. I think that’s an urgent matter, the dearth of ideas and creativity of the cloistered generation that did not come from trauma or struggle. I think my generation was maybe the first group of people who did not come from a historic struggle directly. And what did they do with it? They were educated, they know everything, and then they went into finance. They use their minds for their money to make [more] money, which is great. I haven’t figured out how to do that! But I am worried about the fact that our lives are not better than our parents’ lives. It really is remarkable

to me that it’s hard to know how to give your children a better life than you had.

What do you mean by a better life?

The state of curiosity and intellectualism. The state of using the money you’ve been given or earned to understand the world better, and to make it better. It does not seem that that’s an imperative or a value that is taught outside of elementary school.

Do you think this is a specifically Jewish book? I didn’t, until everyone started telling me it was, like Fleishman. I always wonder if anyone ever called [Jonathan Franzen’s] The Corrections Christian. I also wonder if anyone even called Crossroads Christian, and that is a story about a pastor in a Christian church. I think the sort of underlying paranoid question of this question is, Are Jews really considered American? And I guess the answer is: If you call The Corrections an American novel, and you call Crossroads an American novel, and you call this a Jewish novel—even though all it has is a bar mitzvah at the end, and a dybbuk flying around—then I guess you don’t really consider Jews American. We’re still some sort of asterisk to the American experience, which is maybe clearer than ever these days.

Did the screenwriting you did for the Fleishman TV series, and the success of that novel, have an impact on this book?

Yes, it paralyzed me. Here’s what happens when you’re

making a television show. You hire people. You write it, you produce it, but mostly you’re hiring people. And as you hire the 350 people that it takes to make a TV show, each one starts out by telling you how much they loved your book. I hope it was true—it might not have been, it might have just been good interviewing skills— but you come to think that Fleishman is all you have to offer the world. And so you try to distill what it is that people loved about it.

The one thing I can say I was good at was moving on and starting over. I had some big stories, and I still had to write the next story. But my editor and my agent, who had never seen me not hand something in, saw me hand in seven completely different drafts of this huge book, one of them 700

pages. And they both at different times said, “Do you want to let this one go?”

So when you handed in those drafts, did your editor say, “This isn’t it?” Or was it just you not being happy with them?

Some of them were almost there, but nothing was a revelation. And again, from publishing so much, I’m very acquainted with the sounds of people loving something. And it’s never people saying, “I love it.”

When people love something, they start talking about themselves. And that was my metric. When that first happened, it was one of my agents who called me and said, “I just finished your book, and I have to tell you about something that happened to me when I was young.”

I am worried about the fact that our lives are not better than our parents’ lives.

Can I tell you something about myself? We find out late in the book that Phyllis Fletcher’s birth name was Frieda Mutchnick. I actually had a great-aunt named Frieda Muchnick. I’ll tell you why this is funny. Because in my last book, I had a character named Philippa London. And the name of the guy who interviewed me [when I bought a coop apartment] was Philip London. And he kept talking about how much he loved the book; he’s like, “I read it three times.” And I’m like, “And?” And he had no recollection of the character with his almost exact name. So I’m very glad you saw that. I think it would be a very funny thing if by the end of all my interviews someone would be like, “Oh, that’s my name!”

Long Island Compromise Brodesser-Akner,

Random House | 464 pp. | $30.00 July 9, 2024 | 9780593133491

noticing that he guards his enormous suitcase religiously. Although the two gradually grow closer on the long journey from San Francisco to Syracuse, trading barbs through the limo’s partition, Henry’s easy charm and good looks can’t fully alleviate Mĕi’s suspicions. She repeatedly calls her grandfather, her L ǎoyé—who’s responsible for finding her passengers looking to pay off the books—to see what he thinks about Henry. Since the death of his wife, L ǎoyé’s camped out in the family garage, smoking marijuana and watching old films, shrinking his existence to fit one room. Mĕi recalls the ways his encyclopedic knowledge of history and “ability to educate painlessly” bolstered her high school education and how his acerbic wit offered a lifeline through her teenage years; now she frets over his reluctance to leave home. L ǎoyé’s unquestioning support of her decision to drop out of Dartmouth after her father’s untimely death—buying her a car and introducing her to clients in need of a discreet chauffeur—further strengthens their bond, and she finds herself missing him terribly. With L ǎoyé’s encouragement, she continues the journey, and the lengthy stretches of driving allow Mĕi to reflect on life in the wake of her father’s passing—especially her estrangement from her mother, whose tacit acceptance of his death Mĕi can’t understand. Finally, Henry’s insistence on unusually frequent breaks leads Mĕi to confront him about his precious luggage, and once his secret is revealed she begins to see the world in a very different light. Frazier expertly weaves historic and contemporary injustices faced by Chinese Americans and Uyghurs through this fast-paced, propulsive book, which is at its most powerful when depicting the way Mĕi’s family navigates life after catastrophe. She has a knack for writing funny dialogue—scathing sarcasm underpinned by a great deal of love—and there are plenty of hilarious exchanges to lighten the dark political context of the novel.

A vital, enthralling debut in which devastating social commentary is delivered with a wink.

An extraordinarily beautiful depiction of an ugly world in the making.

NAPALM IN THE HEART

Kirkus Star

Guasch, Pol | Trans. by Mara Faye Lethem

Farrar, Straus and Giroux (256 pp.)

$18.00 paper | Aug. 13, 2024 | 9780374612955

A bleakly brilliant novel of a near future in which humankind has descended into unspeakable brutality.

Catalan poet Guasch makes his fiction debut with this elegantly lyrical view of a world torn apart by an unspecified catastrophe: a plague, perhaps, or climate change. Either way, people hide in dark rooms during the day as wolves descend from the hills, “striding among the houses.” The narrator has remained in his little sun-blasted village to take care of his mother, widowed after her husband’s desperate suicide. Resigned to the world’s terrors, Mom has taken up with a fascist beast whose “head is shaved, like all of them,” servant of a new regime emblematized by a mysterious place called the Factory. The narrator, meanwhile, yearns for his boyfriend, Boris, to whom he writes lovely, evocative letters: “I love you the way we love those who’ve left long ago,” he writes, “and those who haven’t yet arrived….” Boris has relocated to a distant city where life is perhaps a tiny bit better—or so the narrator finds after, in a moment worthy of Cormac McCarthy on the one hand, he dispatches his mother’s suitor and then, evoking Albert Camus on the other hand (“Mother died today. Or yesterday, maybe, I don’t know”), desultorily seeks a place to bury her after he

reunites with Boris, a distant and often sullen young man who has his own priorities. Throw in a little Mad Max-ish chaos of roving gangs, and it’s amazing that anyone or anything can survive, not to mention the narrator’s love for Boris, which, he slyly notes, “dared not speak its name.” Intimations of other European modernists— Schnurre, Dürrenmatt, Cela—resound quietly throughout a text punctuated by museum-worthy photographs to stunning, memorable effect.

An extraordinarily beautiful depiction of an extraordinarily ugly—and wholly credible—world in the making.

Hamill, Shaun | Pantheon (496 pp.)

$29.00 | July 23, 2024 | 9780593317259

The surviving members of a powerful teenage coven of magicians reunite in East Texas. Much like Hamill’s debut, A Cosmology of Monsters (2019), this meaty horror novel is a treat for readers whose nostalgia gravitates to the likes of Stand by Me, Twin Peaks, or, most thematically, Stephen King’s It. In a similar vein to Chuck Wendig’s Miriam Black novels or Stephen Graham Jones’ Indian Lake trilogy, Hamill takes some ordinary young people and puts them through the metaphysical wringer to see what’s left at the end. In Clegg, Texas, circa the late 1990s, we meet best pals Hal, Athena, and Erin. Their chance encounter with a lost boy in the woods leads them to classmate Peter and his grandfather,

Professor Elijah Marsh, an eccentric practitioner of the titular magic who teaches them the ropes. “This power, this energy, this Dissonance?” explains the professor. “It’s born from discomfort. From unhappiness. From pain. This world we occupy, and which we hope to control, is a broken, violent place.” Grappling with forces they don’t really understand leads to a disaster that claims many lives, including one of their own. Unfortunately, our heroes aren’t in great shape two decades later. Erin is a barista going nowhere, Athena parlayed her magical talents into running an occult bookstore, and recovering alcoholic Hal is on his way to prison for murder. When an invitation to a 20th-anniversary memorial service arrives, no one wants to revisit the scene of the crime. But after a well-meaning closeted teen named Owen botches a necromancy spell and finds himself playing Renfield to a bad actor, they’re forced to reunite not just to confront their past but employ all their collective gifts to save the world. The rules governing Hamill’s fantastical universe can be a little hazy, but when the nightmare-fraught tale is filled with monsters, teleportation, time travel, and other supernatural wonders, it’s more fun to embrace the chaos.

A wistful, emotional roller coaster that finds worse than memories waiting at home.

Heller, Peter | Knopf (304 pp.)

$28.00 | Aug. 13, 2024 | 9780593801628

Two men on a hunting trip encounter a civil war.

Heller’s novel follows Jess and Storey, two friends in Maine, as their annual hunting trip turns calamitous. Early on, Heller references a bridge being out and a way forward blocked. The exact nature of the catastrophe isn’t revealed until partway through, though there are some hints. “All summer the entire state had been

convulsed with secession mania,” Heller writes. He describes the situation Jess and Storey are in as being “in the wake of a rolling catastrophe,” with all the momentum that implies. The duo doesn’t encounter another living person until a significant part of the book has passed— and once they do, their situation becomes even more unsettling, as it seems they’re in a war zone with little sense of who’s fighting, and on what side. (The way this escalates allows for a rare moment of gallows humor when Storey says, “The helicopters suggest to me it’s not just a Maine thing.”) The two men find a girl, Collie, who’s become separated from her family, giving the second half a little more structure. Jess and Storey’s journey across an uncertain landscape is interspersed with Jess’ thoughts on his now-defunct marriage and his long friendship with Storey. Heller ably captures the white-knuckle momentum as the two men try to stay alive—bringing this book closer in tone to James Dickey’s WWII–era thriller To the White Sea than to Cormac McCarthy’s The Road . But that choice also makes the speculative elements feel disconnected from the story of the long friendship at this novel’s heart; it’s not hard to imagine much of the same action occurring in the wake of a natural disaster. An ambitious story of survival that doesn’t always click, but is frequently thrilling.

Iglesias, Gabino | Mulholland Books/ Little, Brown (352 pp.) | $29.00 Aug. 6, 2024 | 9780316427012

A Puerto Rican teen out to avenge the murder of his mother finds himself in an even darker place when Hurricane Maria strikes, bringing with it ghosts, demons, and horrific visions.

After his mother, a low-level drug dealer named Maria, is shot in the face

for encroaching on someone’s territory, her son, Bimbo, will stop at nothing to avenge her—including torturing and murdering people for information. Most of his close friends don’t want any part this. But after one of them, Xavier, is murdered and Gabe, the primary narrator of the book, barely escapes the killers, their outlook changes. Torn between loyalty to Bimbo and love of his girlfriend, Natalia, who tries to talk sense into him (she’s desperate to escape to the United States), Gabe ultimately embraces his anger. When the hurricane hits, causing an epic power outage, all kinds of people go missing and little attempt is made by the authorities to find them. Myth crashes into reality when “a very large human made of shadows and with a black hole for a face” is seen at the edge of the storm. Prayers and incantations to various Orishas can’t erase unthinkable visions including that of a father bashing in his newborn baby’s skull with a brick because he was born with a horn in the middle of his forehead. In this epic darkness, no amount of bloodshed is enough for Bimbo, and Gabe, finding comfort with a gun, stays with him. Iglesias is an unstoppable force himself, intensifying the grief and widespread helplessness felt on the island post-Maria, along with the supernatural elements. The book isn’t without its excesses, but it’s a step up from his previous novel, The Devil Takes You Home (2022).

A mostly successful combination of horror, crime, and teen lit.

Jones, Gayl | Beacon Press (224 pp.) $26.95 | Aug. 20, 2024 | 9780807030035

A surprising, welcome gift from one of America’s finest and least predictable writers. This chronicle of a Black GI’s return to the American South after World War II

provides Jones with the occasion to kick back and gently unravel the story of Buddy Ray Guy, an erstwhile Army cook and tractor repairman, who’s on something of a quest to find the book’s eponymous “Unicorn Woman,” whom he first beholds, albeit from odd angles, at a carnival near his hometown of Lexington, Kentucky. Though he can see the “spiraled horn” protruding from the woman’s forehead, Buddy is just as astonished by the “slender, dimpled arms [that] were the color of my own” since he’s more used to finding “white freaks” at carny sideshows. From then on, the enigmatic woman stalks Buddy’s dreams as he makes his way from Kentucky to Memphis, trying to parlay the mechanical skills he picked up in the military into a full-time civilian living in a postwar America still tethered to racial segregation. When Buddy confesses his obsession with the spiral-horned woman to Esta, his sometime girlfriend, she chalks it up to Buddy’s wildly romantic imagination: “You are more of a freedom seeker…than a unicorn seeker, Buddy Ray,” she tells him. “I don’t know whether freedom seekers are ever truly satisfied.” Nevertheless, not even the vicissitudes of Jim Crow America can keep Buddy from following through on his dreams, whether they involve conversing with the elusive unicorn woman or figuring out how to make the best use of his craft. All the while, Jones weaves a captivating tapestry of African American life in the 1940s from Buddy’s dreams and the wide-ranging information he collects on his quest throughout the mid-South from friends and relatives. He keeps his eyes and ears open to all manner of input, whether it comes from fragments of an Amos ‘n’ Andy radio broadcast or from the folk wisdom he gathers at

restaurants, homes, and places of worship. Most of all, it’s Buddy’s narrative voice—digressive, reflective, witty, and wise—that sustains one’s attention and affection throughout this warm, savory evocation of the elegiac, the fantastic, and the historic. Even when she dials down the intensity, Jones is capable of quiet astonishment.

Kellerman, Jonathan & Jesse Kellerman Ballantine (368 pp.) | $30.00

Aug. 6, 2024 | 9780525620143

Father and son Kellerman collaborate on the fifth Clay Edison PI adventure. On Northern California’s Lost Coast, the executor of a woman’s estate needs help sorting out some curious monthly payments the deceased had been making. Having no luck with one private investigator, she asks Oakland ex-cop turned PI Clay Edison. Soon the original PI, Regina Klein, bawls him out in bleep-worthy terms for horning in on her case, but they form a temporary alliance to solve a complicated plot that’s rife with peril. It looks like someone is running a real estate scam on an isolated location on the Lost Coast called Swann’s Flat. A narrow and dangerous road twists and turns to the destination, and Clay sideswipes a teenage cyclist on a hairpin turn. The girl, Shasta, doesn’t blame Clay for her minor injuries, and she becomes a key in a story that’s peppered with vivid

The prevailing mode is irony, ranging from playful to grotesque.

HELLO, HORSE

descriptions: Clay sees “the Pacific Coast baring its teeth. It was a crude, ax-hewn land, bunched like the front end of a head-on collision.” And Regina is one of an abundance of well-drawn, entertaining characters: She has a gift for acting and easily switches from garbage-mouth to sweetness and light as the situation calls for. As a pretend married couple, they go to Swann’s Flat and let a B.S. artist named Beau try to sell them property in this “private residential community”: “Find your heart on the Lost Coast!” Clay checks in frequently with his real wife, Amy, who’s at home with their two kids. He even consults with her on how much risk he should take; they are a loving family apparently devoid of flaws. Meanwhile, a one-hit-wonder novelist can’t be found, and another young man is missing. Years earlier, Shasta’s dad had fallen into oblivion off a cliff so high you couldn’t hear the thump at the bottom. Maybe it was an accident or maybe not. And maybe Pop won’t be the cliff’s last victim. Crisp, witty dialogue zips this well-paced story along so that when violence happens, it comes as a shock.

Kellerman fans will love this one.

Kemick, Richard Kelly | Biblioasis (224 pp.) | $16.95 paper

Aug. 6, 2024 | 9781771966078

Eleven strange, sly stories by an intriguing Canadian writer. Kemick has published a volume of poetry (Caribou Run), an account of his stint in a Passion play (I Am Herod ), and a stage production called Amor de Cosmos: A Delusional Musical The tales here mix whimsy, weirdness, lust, and Canadian politics, bringing to mind George Saunders and the slackers from Wayne’s World. In “Gravity,” two teenagers are paid to make insulting

alterations to political campaign signs. The narrator ponders how he’ll miss his life’s “infinite simplicity” when his 16-year-old girlfriend has their baby. In the 50-page “Satellite,” a convent school in a future world of constant fires and smoke has teens and nuns in full habit competing fiercely at ice hockey. In “Patron Saints,” infidelity touches a gay couple in Paris, where an escaped tiger roams the streets; one of the men trades quips with a talking dog. At a Canadian teachers’ conference in Cuba in “Sea Change,” two attendees struggle to find the enthusiasm for adultery while pro-democracy protests turn into “state-sanctioned violence.” In “Our Overland Offensive to the Sea,” a Canadian colonel, “after an RV vacation to Gettysburg,” decides to stage a mini civil war in Manitoba with live ammo and some troops dragooned from prison and introduced with their crimes, as in “Carl (Drugs).” Kemick writes with the detail and clarity of good journalism. The prevailing mode is irony, ranging from playful to grotesque, which forms a distancing frame for the author’s sympathetic sketches of life’s portions of pain, hope, or confusion. He has a penchant for alternating between things familiar and bizarre. The “simplicity” of the teens’ life in “Gravity,” for instance, includes a mother who “hung herself with a plugged-in strand of Christmas lights.” Provocative, entertaining short fiction.

Low, P.H. | Orbit (432 pp.) | $19.99 paper July 9, 2024 | 9780316569200

A pair of former Lost Boys return to the Island to steal a famous fairy. Peter’s roster of Lost Boys never changes; when one Boy grows up, Peter simply collects another to take his name and place. That rule once allowed unrelated best friends Jordan and Baron to join as “the Twins.” Sure, Jordan had to pretend

to be a boy and use Dust to glamour her missing hand, but it was worth it for a life on the Island. Years after her first menstrual period outed her and nearly cost her her life, Jordan is a famed underground fighter with a mean drug addiction. Half a decade of heavy Dust use has left her reliant on a street drug—and the landlord-dealer who supplies it—to get by. Determined to get out from under his thumb, Jordan hatches a plan to return to the Island with Baron and steal Tink from Peter. Complicating her endeavor is the fact that no grown-up has ever gone to the Island and lived to tell the tale. But Jordan may just be the only person ambitious enough to succeed. And when she takes up the pirate captain’s hook, well, that’s where the story really takes off. Low walks a knife’s edge here, remaining faithful to Barrie’s original work while transplanting it into an invented world. The novel showcases the brutality of the Lost Boys’ existence, as members of their little tribe kill wantonly. Peter comes off as particularly frightening here. Readers will recall his line in Barrie’s novel, “I forget them after I kill them,” as they watch him cull the followers who have grown too old and make Dust from his victims’ ground bones. Intersectionality abounds. Jordan has a congenital limb difference and a complicated relationship to her gender identity. Baron lives with intense anxiety, as well as suicidal ideations. Both heroes are Chinese-coded. The grown-up Peter Pan sequel readers needed all along.

Rip Tide

McKeegan, Colleen | Harper/ HarperCollins (272 pp.) | $27.99 Aug. 13, 2024 | 9780063305540

women struggle to overcome unhealthy teenage relationships, McKeegan’s novel has the trappings of a beach-read mystery. On the first page of the first chapter, labeled “Beach Week 2022: Day Six,” a dead body shows up; then the book jumps back to “Day One” and alternates between Beach Week 2022 and events at least 15 years earlier. Kimmy, a “finance superstar,” arrives in Rocky Cape after a long absence. Her younger sister, Erin, has been living at home since her difficult divorce at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. As the week wears on, each sister relives painful memories of secrets and betrayals. The depiction of their love-hate relationship as kids is funny if painful, and McKeegan’s depiction of the sex, drugs, and general hedonism of teens during the early 2000s rings painfully true. Kimmy got in over her head and ended her senior year in deep trauma and humiliation. Now she reconnects with old friends, including her high school passion, Justin, who slept with her regularly back then though his official girlfriend was Erin’s nasty friend Madison. Despite Kimmy’s memory of Justin’s part in her ultimate humiliation, she can’t resist their mutual attraction during Beach Week. Erin had a secret teenage passion, too: Peter, an older college boy with whom she carried on a confusing flirtation, her devotion fueled by his mixed signals. After moving home two years ago, she fell into an affair with the married Peter. Now Peter is that dead body. Eventually the book moves past Day Six to follow the detective—a former classmate of Kimmy’s—who’s investigating whether Peter’s death was suicide or murder. There’s a fun twist at the end but McKeegan’s strength is bringing to life the intricate family and small-town social dynamics on display.

Sisters in their 30s return to their Jersey Shore hometown, where they revisit lingering demons from their adolescence.

Although it’s really about the ways young

A dark, witty beach read about beach-town shenanigans.

Newman, Nathan | Viking (288 pp.)

$29.00 | Aug. 13, 2024 | 9780593654903

A wayward 20-something art critic discovers a great deal about himself and his hometown in pursuit of a missing package.

The inciting incident for debut author Newman’s raucous first novel is a simple mix-up of the Royal Mail. Natwest, a once-precocious English teen and aspiring art critic, has aged into a pretentious young adult finally headed off to university. The morning before departing his small town for the big city, Natwest anxiously awaits the arrival of a discreet package of particular length and girth, only to inadvertently swap parcels at the post office with his mother’s employer, dentist Dr. Richard Hung (pun very much intended). As Natwest attempts to recoup his item, his path intersects with a number of seemingly minor characters whose roles gradually assume greater importance: Mrs. Pandey, a former teacher who fostered young Natwest’s potential; Joan, a widower across the street who’s getting back into the dating scene; and Mishaal, a local imam enduring an unhappy marriage. Newman expertly threads together the minor events and small mishaps of the characters’ lives in a convincing recreation of the inescapable social overlap that often defines life in a small town. Underlying it all is a preoccupation with beauty and the value of art. Natwest obsessively sees references everywhere: His mother in an orange nighty recalls “Leighton’s Flaming June ”; the stares of disapproving neighbor boys “pierced him like the arrows in a St. Sebastian picture.” More than motifs, artistic legacies are also the source of much of the book’s humor—at one point, Natwest imagines Geoff Dyer attending his funeral. Newman

works in more profound interactions as well. Reconnecting on a park bench, Natwest and former mentor Mrs. Pandey debate the artistic merits of a nail salon mural painted in the style of Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam , the outstretched fingers on each figure sporting pink nail polish: It’s Žižekian, it’s Jungian, it’s Pop Art in situ, “Warhol’s soup cans, restored to the Asda aisle.” In seeking to balance intelligent prose, insightful commentary, and compelling characters, Newman delivers. Smart and funny, Newman’s debut is a refreshing take on juvenilia and the enduring potency of art discourse.

Kirkus Star

Ogawa, Yoko | Trans. by Stephen Snyder Pantheon (288 pp.) | $28.00 Aug. 13, 2024 | 9780593316085

A young Japanese girl spends the pastoral summer of 1972 with her asthmatic cousin. Focusing on characters of an age when the world seems full of wonder and possibility, this engaging bildungsroman explores the friendship and mutual curiosity between two extraordinary young people. Our narrator is 12-yearold Tomoko, who has been sent to live with her aunt’s family in the wake of her father’s death as her mother studies dressmaking in Tokyo. In comparison to their young charge, the family is outsized—sophisticated and wealthy inheritors of a soft-drink empire, complete with a country estate—and includes Tomoko’s enigmatic aunt; her half-German uncle, who is more absent than not; and their charismatic 18-year-old son, Ryūichi, off studying at university. The center of Tomoko’s orbit is her younger cousin, Mina, an ailing bookworm who persuades Tomoko to raid the local library for her fix and eventually shares the secret of her

hidden collection of matchboxes, given to her by a crush. This curious duo is lightly grounded by the inclusion of groundskeeper Kobayashi and cook Yoneda, who has curiously bonded late in life to Mina’s German grandmother, Rosa. If this weren’t enough to fill a Wes Anderson film’s worth of oddballs, there’s always Mina’s pet pygmy hippopotamus, Pochiko, the last survivor of a family zoo closed since World War II. While much of what we see on the surface is idyllic, Ogawa laces her narrative with real-life tragedies, among them the mysterious suicide of Japanese writer Yasunari Kawabata and the massacre of Israeli athletes at the Olympics in Munich. Facing complicated themes with deceptively simple language, she pulls off a neat trick here, painting everything in miniature and often in hindsight without losing the immediacy of Tomoko’s experiences. A charming yet guileless exploration of childhood’s ephemeral pleasures and reflexive poignancy.

Pedersen, Kailee | St. Martin’s (304 pp.) $29.00 | Aug. 20, 2024 | 9781250328243

A Nebraska family’s unquenchable violence is interrupted, then accelerated, by a femme fatale. This incantatory debut builds menace from its opening phrase:

“Moonlight slashes open the boy’s face.” The boy, Nick Morrow, is indeed menaced—and beaten—by father and brother; mom is killed off in childbirth in the second paragraph. Nick is trapped on his family’s “one thousand acres of rich loam atop the Ogallala Aquifer,” a place called Stag’s Crossing, thanks to the stag’s head perched on the front gate. It’s just the first decapitation featured in this grisly and relentlessly readable horror story. The author toggles 40 staccato chapters, each titled “Then” or “Now,” shifting between Nick’s adolescence and an excruciating time

A brilliant fable of sisterhood, class, and our relationship to nature.

BEAR

three decades later. The patriarch, Carlyle Morrow, possessing “a violence keen and beautiful as the silver curve of a fishhook,” has engineered a ruse to bring home his two estranged middle-aged sons. The favored older, Joshua, brings Emilia, his “high-strung, unintimidated” Asian American wife; Joshua’s choice of her ruptured Carlyle’s hold on his offspring. Now, thanks to the shocking and unnatural nature of Emilia, the Morrow patrimony of cruelty, wielded “with an ancient and primeval ecstasy,” will climax. And when it does, the author—who was adopted from Nanning, China, onto a Nebraska farm—is merciless. She writes with a rare acuity, bending her language toward fable, salting it with words like “demesne,” “eidolon,” and “sinfonietta.”

She is excellent at blurring the animal and human, even as her unbroken tone lacks the quotidian details that can relieve and ratchet horror. Still, few readers are likely to quit before the final chapter, “Then & Now.”

An assured and bloody fable heralds the arrival of a gifted new voice attuned to ancient modes of damnation.

Phillips’ follow-up to her acclaimed debut, Disappearing Earth (2019), again concerns a pair of sisters in a gorgeously evoked, off-the-beaten-track setting, this time with a close focus on the complicated psychology of the sibling relationship. Elena and Sam’s beautiful mother was “an orphan with two toddlers by the time she was twenty-five” and now, not long past her 50th birthday, is dying of causes related to inhaling solvents at the nail salon where she worked. Her daughters toil at the golf club restaurant and in the snack bar on the ferry; their plan is to make ends meet until their mother dies, then sell their house and the valuable land it occupies and leave the island. Phillips opens the novel with an excerpt from the fairy tale “Snow-White and Rose-Red” by the Brothers Grimm: “‘Poor bear,’ said the mother, ‘lie down by the fire, only take care that you do not burn your coat.’”

The Devil Raises His Own

Phillips, Scott | Soho Crime (384 pp.)

$27.95 | Aug. 6, 2024 | 9781641294935

The seamy side of silent pictures.

Phillips, Julia | Hogarth (304 pp.)