FEATURING 273 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s, and YA Books

FEATURING 273 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s, and YA Books

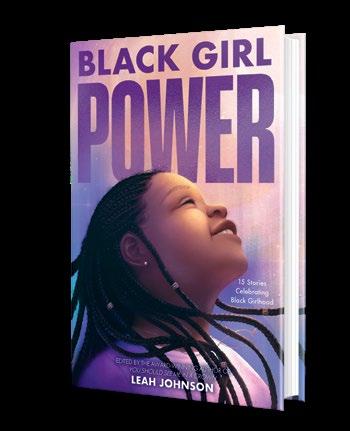

The author and bookseller celebrates Black girlhood with a new middle-grade anthology

FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK

IF YOU’RE A book lover, one of the most alarming trends of the past few years is the rise of censorship in U.S. schools and school libraries. During this year’s Banned Books Week (Sept. 22–28), PEN America, the literary nonprofit that advocates for freedom of speech, reported more than 10,000 challenges to various titles during the 2023–24 school year, statistics that were “off the charts,” according a memo about the preliminary findings. The American Library Association tallied fewer book bans in its own preliminary report, but however you keep score, there’s no doubt that right-wing activists today feel emboldened to challenge books—especially those by and about Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) and LGBTQ+ people—poten-

tially keeping these works out of the hands of young people in many communities.

As discouraging as this state of affairs may be, the response of the literary and education communities has been inspiring. The New York Public Library, for example, has launched a Teen Banned Book Club; this fall they’re reading Mike Curato’s Flamer —one of the most frequently challenged titles in recent years—and teens nationwide will have the opportunity to discuss the book with the author online on Nov. 21.

Elsewhere, bookstores have leapt into the void. In her hometown of Gainesville, Florida, author Lauren Groff (Fates and Furies, The Vaster Wilds) opened The Lynx, a shop with an “emphasis in books that are currently

Frequently Asked Questions: www.kirkusreviews.com/about/faq

Fully Booked Podcast: www.kirkusreviews.com/podcast/

Advertising Opportunities: www.kirkusreviews.com/book-marketing

Submission Guidelines: www.kirkusreviews.com/about/publisher-submission-guidelines

Subscriptions: www.kirkusreviews.com/magazine/subscription

Newsletters: www.kirkusreviews.com

For customer service or subscription questions, please call 1-800-316-9361

challenged or banned in Florida, as well as those by BIPOC authors, LGBTQ+ authors, and Florida authors.” (According to PEN America, Florida and Iowa lead the nation in challenges.) A nonprofit associated with the store, The Lynx Watch, works to distribute banned books throughout the state.

Author Leah Johnson, who appears on the cover of this issue, is also playing a vital role in the fight to protect access to books—not just by writing them but by selling them, too. Last fall, the author of the acclaimed YA novels You Should See Me in a Crown (2020) and Rise to the Sun (2021) opened Loudmouth Books in her hometown of Indianapolis. Loudmouth specializes in books by marginalized people; the impetus for the business was the wave of legislation facilitating book banning that has swept through many states, including Indiana.

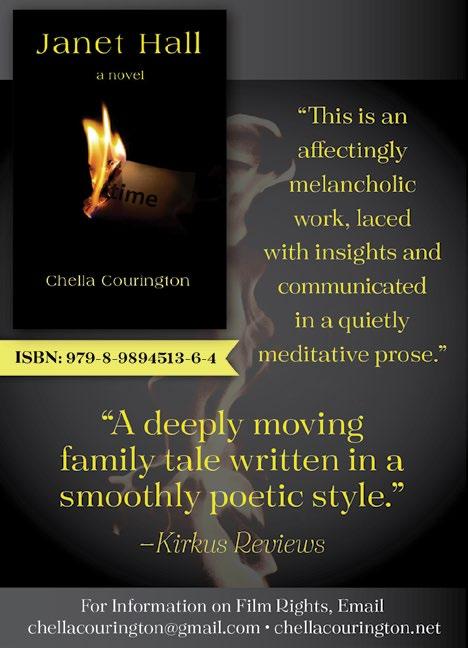

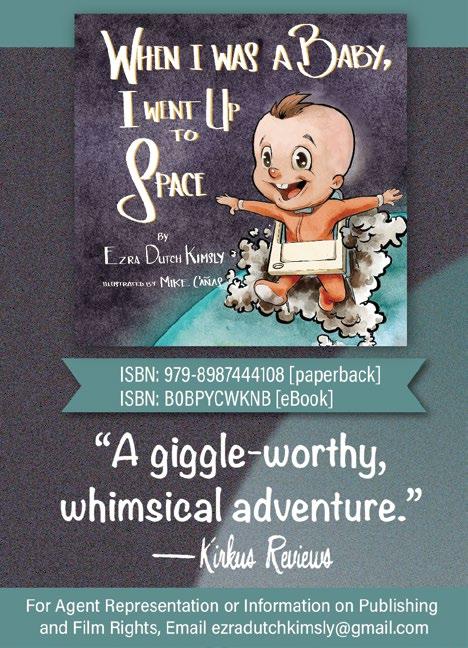

More recently, Johnson edited the middle-grade anthology Black Girl Power: 15 Stories Celebrating Black Girlhood (Freedom Fire/

Disney, Nov. 12), which brings together contributions by Elise Bryant, Kekla Magoon, Ibi Zoboi, Dhonielle Clayton, and others. As Johnson tells editor at large Megan Labrise in the cover story on p. 88, the new Disney imprint, headed by author Kwame Mbalia, made a “big statement” by putting the book on its inaugural list: “These narratives [of adolescence] are universal but so rarely given the time and the space to shine when it comes to us Black girls,” she says. That very challenge to the literary status quo is what often puts books like Black Girl Power in the crosshairs of would-be censors. The reactionary forces behind challenges and bans hate to expose young people to new narratives and new ways of seeing the world. Fortunately, literary citizens like Leah Johnson are fighting back with powerful stories and platforms for readers to find them. That’s something to celebrate.

Ingram’s Collection Development team of MLS-degreed librarians work to ensure that libraries are positioned to anticipate and meet patron demand.

Take advantage of these customizable programs today.

Trending Topic Lists:

iCurate Complimentary

Discover hundreds of complimentary curated lists.

Forthcoming Title Lists:

iCurate Coming Soon

To meet the need to easily manage new, forthcoming and tending titles, this annual subscription is NOW complimentary!

Essential Collection Analysis:

iCurate Core

Rebalance your collection with a one-time list suite of essential titles missing from your collection.

Tailor-Made Special Projects:

iCurate Custom

Supplement your collection team with Ingram’s librarians to curate high-quality, customized lists, tailored to fit your specific needs.

Diversity Audit:

iCurate inClusive

An effortless & effective diversity audit that delivers a one-time diversity assessment of your library’s collections. Including a comprehensive holdings assessment, data-driven reports, and actionable lists.

Co-Chairman

HERBERT SIMON

Publisher & CEO

MEG LABORDE KUEHN mkuehn@kirkus.com

Chief Marketing Officer

SARAH KALINA skalina@kirkus.com

Publisher Advertising & Promotions

RACHEL WEASE rwease@kirkus.com

Indie Advertising & Promotions

AMY BAIRD abaird@kirkus.com

Author Consultant RY PICKARD rpickard@kirkus.com

Lead Designer KY NOVAK knovak@kirkus.com

Magazine Compositor

NIKKI RICHARDSON nrichardson@kirkus.com

Kirkus Editorial Senior Production Editor

ROBIN O’DELL rodell@kirkus.com

Kirkus Editorial Senior Production Editor

MARINNA CASTILLEJA mcastilleja@kirkus.com

Kirkus Editorial Production Editor

ASHLEY LITTLE alittle@kirkus.com

Copy Editors

ELIZABETH J. ASBORNO

LORENA CAMPES

NANCY MANDEL BILL SIEVER

Contributing Writers

GREGORY MCNAMEE

MICHAEL SCHAUB

Co-Chairman

MARC WINKELMAN

Editor-in-Chief TOM BEER tbeer@kirkus.com

President of Kirkus Indie

CHAYA SCHECHNER cschechner@kirkus.com

Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK lmuchnick@kirkus.com

Nonfiction Editor JOHN McMURTRIE jmcmurtrie@kirkus.com

Young Readers’ Editor

LAURA SIMEON lsimeon@kirkus.com

Young Readers’ Editor

MAHNAZ DAR mdar@kirkus.com

Editor at Large MEGAN LABRISE mlabrise@kirkus.com

Senior Indie Editor

DAVID RAPP drapp@kirkus.com

Indie Editor

ARTHUR SMITH asmith@kirkus.com

Editorial Assistant NINA PALATTELLA npalattella@kirkus.com

Indie Editorial Assistant

DAN NOLAN dnolan@kirkus.com

Indie Editorial Assistant SASHA CARNEY scarney@kirkus.com

Mysteries Editor

THOMAS LEITCH

Contributors

Colleen Abel, Stephanie Anderson, Kent Armstrong, Mark Athitakis, Colette Bancroft, Audrey Barbakoff, Thomas Beheler, Nell Beram, Heather Berg, Elizabeth Bird, Christopher A. Biss-Brown, Sarah Blackman, Rhea Borja, Jessica Hoptay Brown, Jeffrey Burke, Kevin Canfield, Catherine Cardno, Hailey Carrell, Tobias Carroll, Charles Cassady, Ann Childs, Tamar Cimenian, Caridad Cole, Rachael Conrad, Adeisa Cooper, Jeannie Coutant, Kim Dare, Michael Deagler, Cathy DeCampli, Dave DeChristopher, Elise DeGuiseppi, Steve Donoghue, Anna Drake, Elspeth Drayton, Lisa Elliott, Tanya Enberg, Rosalind Faires, Joshua Farrington, Eiyana Favers, Rodney Fierce, Katie Flanagan, Mia Franz, Ayn Reyes Frazee, Jenna Friebel, Robbin Friedman, Roberto Friedman, Nivair H. Gabriel, Laurel Gardner, Jean Gazis, Fiona Giles, Chloé Harper Gold, Carol Goldman, Carla Michelle Gomez, Melinda Greenblatt, Vicky Gudelot, Tobi Haberstroh, Silvia Lin Hanick, Loren Hinton, Zoe Holland, Katrina Niidas Holm, Abigail Hsu, Julie Hubble, Kathleen T. Isaacs, Darlene Ivy, Kristen Jacobson, Wesley Jacques, Jessica Jernigan, Deborah Kaplan, Ivan Kenneally, Stephanie Klose, Lyneea Kmail, Andrea Kreidler, Alexis Lacman, Megan Dowd Lambert, Carly Lane, Christopher Lassen, Hanna Lee, Judith Leitch, Maureen Liebenson, Elsbeth Lindner, Coeur de Lion, Sarah Lohmann, Barbara London, Karen Long, Patricia Lothrop, Wendy Lukehart, Kyle Lukoff, Leanne Ly, Michael Magras, Joan Malewitz, Thomas Maluck, Collin Marchiando, Matthew May, J. Alejandro Mazariegos, Kirby McCurtis, J. Elizabeth Mills, Tara Mokhtari, Clayton Moore, Andrea Moran, Rhett Morgan, Christopher Navratil, Liza Nelson, Therese Purcell Nielsen, Katrina Nye, Erin O’Brien, Tori Ann Ogawa, Mike Oppenheim, Nick Owchar, Emilia Packard, Andrea Page, Megan K. Palmer, Derek Parker, Sarah Parker-Lee, Hal Patnott, John Edward Peters, Christofer Pierson, Shira Pilarski, Carolyn Quimby, Kristy Raffensberger, Stephanie Reents, Erica Rivera, Kelly Roberts, Amy Robinson, Lizzie Rogers, Elisa Rowe, Gia Ruiz, Lloyd Sachs, Bob Sanchez, Keiko Sanders, Meredith Schorr, Gretchen Schulz, Jerome Shea, Sadaf Siddique, Linda Simon, Margot E. Spangenberg, Allison Staley, Mathangi Subramanian, Deborah Taylor, Eva Thaler-Sroussi, Desiree Thomas, Bill Thompson, Renee Ting, Lenora Todaro, Jenna Varden, Christina Vortia, Katie Weeks, Audrey Weinbrecht, Amelia Williams, Kerry Winfrey, Marion Winik, Livia Wood, Bean Yogi, Jenny Zbrizher, Natalie Zutter

THIS YEAR, the first Tuesday of November is something more than Laydown Day for new books—it’s also the day of the presidential election, when no one is going to be paying attention to the latest fiction releases. But there are some exciting novels slipping into bookstores that day, beginning with Two Times Murder (Severn House, Nov. 5), the second novel in a mystery series by Adam Oyebanji. The hero, Gregory Abimbola, describes himself as “a bi-racial Russian of African descent pretending to be English.” He’s also a former Russian agent hiding out in Pittsburgh, teaching at a private school and—no surprise—getting mixed up in a variety of murders. Our starred review says this book

is “not to be missed.” (See the full review opposite.)

The title of Andy Marino’s chilling novel, The Swarm (Redhook, Nov. 5), refers to a brood of cicadas that appears in upstate New York a year before they’re due. There’s a dead body whose teeth and nails have been fully removed and who’s suspiciously untouched by insects. There’s a young woman caught up in a cult. There’s a forensic entomologist and a tech company founder trying to figure out what’s going on. “Readers who savor bugs and body horror will find plenty to enjoy here,” according to our review. “Shaggy, kinetic, and relentless.”

With any luck, we’ll know the next president by November’s second Laydown Tuesday, and

we’ll have more attention to spare for books. One to consider: Richard Price’s Lazarus Man (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Nov. 12), his first novel since Lush Life in 2008. When that book came out, our reviewer said, “There oughta be a law requiring Richard Price to publish more frequently. Because nobody does it better.” (In 2015, he published The Whites using the pseudonym Harry Brandt.) Perhaps he’s been writing this new book ever since he finished Lush Life, since it’s set in 2008, and follows a Harlem community in the aftermath of a building collapse. Our starred review calls it “an affecting novel by a literary urbanologist in top form.”

It’s been six years since Haruki Murakami published

a novel, and his latest, The City and Its Uncertain Walls (translated by Philip Gabriel; Knopf, Nov. 19), harkens back to an even older work, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World (1991). In a mysterious walled city, a young man interprets dusty dreams and then, returning to a more recognizable world, he grows up to become a librarian working with tangible books. Our starred review calls it “another beguilingly enigmatic tale from Murakami, complete with jazz, coffee, Borgesian twists, the Beatles, and other trademark motifs.…One of his most satisfying tales.”

Juhea Kim’s first novel, Beasts of a Little Land (2021), was a historical epic encompassing decades of 20th-century Korean history though a group of women trained by a renowned courtesan. Her enchanting new book, City of Night Birds (Ecco, Nov. 26), couldn’t be more different: Taking place in the world of Russian ballet, it follows one celebrated ballerina’s tumultuous career. Our starred review calls it “another brilliant page-turner.”

Laurie Muchnick is the fiction editor.

The second in Oyebanji’s A Quiet Teacher series doubles down on his hero’s skills and determination.

Gregory Abimbola is a complicated fellow with an incredible past. He’s the biracial British child of an African father and a Russian mother, brought up in a country where his “very skin was a scandal.” He’s a former Russian agent who’s hiding out in Pittsburgh after a failed attempt to kill him in Djibouti, teaching Russian and French to students at a private school whose privileged parents’ simplistic notions of race and culture are a constant source of frustration.

Everywhere he turns there’s a murder that needs to be

investigated and no one as equipped as he is to solve it. Now, a local police detective asks him to identify a body found in the river; a spurned suburban wife wants him to prove that her ex-husband’s death was not a suicide; and worst of all, a former colleague from the Russian Intelligence Agency orders him to discover— and dispatch—the killer of a fellow agent, threatening harm to his mother if he balks. There’s scant reward for success and danger lurking in failure, but as in Abimbola’s first foray into detection proved in A Quiet Teacher (2022), his code of honor makes it impossible for him turn his back on those who need him.

Oyebanji makes the unimaginable not only credible but compelling by exposing Abimbola’s rich inner life and setting it against the struggles of those who rely on him for help, most of whom can’t get out of their own way,

but nevertheless command readers’ sympathy for their challenges. Oyebanji’s puzzles are well-crafted and his solutions ingenious, leaving readers with both a sense of satisfaction and an appetite for more. Not to be missed.

Aber, Aria | Hogarth (368 pp.)

$29.00 | Jan. 14, 2025 | 9780593731116

A n aspiring photographer bent on concealing her Afghan heritage becomes embroiled in the Berlin techno scene and a fraught relationship with an older man.

Nilab Haddadi, known by most of her friends as Nila, is the daughter of refugees. Her parents, who once lived prosperous lives as doctors in Kabul, fled Afghanistan before she was born. All Nilab knows is the life they subsequently carved out in Berlin, and it, by turn, embarrasses and infuriates her: Their building is run-down and littered with Nazi graffiti, neighbors eye her comings and goings suspiciously, and memories of how carefully her family had to present themselves after 9/11 to avoid being harassed still loom large. After returning home from a boarding school where no one knew her true origins, 18-year-old Nilab has no desire to stick around an apartment defined by her dead mother’s absence and her father’s disapproval. She escapes to a techno club she affectionately refers to as the Bunker, where she quickly falls into the orbit of 36-year-old Marlowe Woods, known throughout the underground scene as “the American writer who always carried speed.” Though he has a “kind-of girlfriend” when they meet and Nilab’s friends warn her against getting in too deep, there is a queasy inevitability to their union. Coming-of-age stories focused on a relationship with an older, ill-advised paramour are a time-honored tradition, but Marlowe’s red flags are so glaring from the outset that Nilab comes across as startlingly, almost doggedly naïve. Aber’s storytelling also often undercuts its own tensions: Nilab narrates the novel from an indeterminate future, dampening the emotional immediacy, and more than once Aber elides dramatic conversations between characters in favor of describing the emotional aftermath. Still, Aber’s vivid depiction of

A campfire story about a girl whose brother is a bear.

Berlin and the novel’s earnest wrestling with shame about desire and identity will be of interest to many readers. A debut still in the process of finding itself—like its young protagonist.

Kirkus Star

Armstrong, Tammy | Harper/ HarperCollins (352 pp.) | $28.99 Oct. 8, 2024 | 9780063396142

Well-wrought touches of the fantastic enhance this tale of a girl growing up in a Canadian logging camp a century ago. About the time that Pearly Everlasting Hazen—named for a wildflower—is born in a remote logging camp in New Brunswick in 1920, her father, the camp cook, finds a tiny, orphaned bear cub in an ice-rimmed burrow. He brings the creature home, and his wife nurses her infant daughter and the cub together. As far as Pearly Everlasting and her family are concerned, Bruno is her brother, even as he grows big enough to unsettle strangers. The logging camps where the Hazens live are harsh places; if the work doesn’t kill someone, the weather might. Pearly Everlasting’s mother, Eula, is a healer who tends workers’ broken bones and other wounds, while her husband, Edon, keeps everyone fed. Pearly Everlasting and Bruno—and human older sister Ivy—grow up in this nurturing nest, attuned to the natural world and pretty much blissfully unaware of what’s beyond. Their only outside contact is a woman they call Song-catcher, an ethnologist who, with her companion,

Ebony, travels around with cumbersome recording equipment to document folk music and tales by people like Eula. The eventual snake in this childhood paradise is a new camp boss, a bully named Swicker, who arrives with a couple of minions and soon has Bruno in his sights. An attempt to bear-nap Bruno and sell him to an animal trader is foiled with the help of Song-catcher and Ebony, but later girl and bear, teenagers by now, stumble upon a murdered body, and Bruno is blamed and confiscated. Pearly Everlasting’s harrowing quest to get him back, on foot through the winter woods and then in a town that’s a complete mystery to her, is paralleled by the search for the pair by a young man named Ansell, a worker at the camp whose face is strangely webbed with silver scars, the result of a lightning strike. Armstrong, who has published five books of poetry and two previous novels, tells their tale in lyrically striking prose and makes its fairy tale elements work by grounding them in the grim realities and stunning beauties of life in a Depression-era logging camp. A campfire story about a girl whose brother is a bear becomes a warmly enchanting novel.

Arsén, Isa | Putnam (368 pp.)

$30.00 | Jan. 7, 2025 | 9780593718360

Sex and drugs and… Shakespeare. What begins as a marriage of convenience between two 1950s New York actors—one seeking to avoid scrutiny from the House Un-American

Activities Committee—results in more drama than they foresaw. Narrator Margaret Wolf, a member of the Bard Players, is a refugee from a hardscrabble Kentucky upbringing and from the violence and mistreatment of her early days in theater in Richmond. When she marries Wesley Shoard, a handsome, charming, and gay fellow cast member, it’s an unconventional union but one marked by love and affection. Margaret’s personal demons—including no small amount of overidentification with the roles she plays—leave her in a fragile mental state and out of work for a period. She accompanies Wesley to an unusual engagement at an isolated replica of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in the New Mexico desert. The couple’s relationship is tested during a summer of rehearsals there by numerous forces, including troupe members attractive—and attracted—to both of them; Margaret’s growing dependence on the pharmaceuticals—licit and illicit—she relies on to face the day; and the unexplained and menacing presence of a network of mobsters affiliated with the theater’s operations. The troupe’s engagement comes to a tumultuous end, with high stakes for Margaret and Wesley and a cinematic resolution to the duo’s woes, incorporating several nods to the Bard along the way. With sensitivity to a range of queer relationships as well as to Margaret’s unraveling psyche, Arsén paints a vivid portrait of 1950s backstage culture. The demands and compulsions of theater life create a satisfying backdrop for historical fiction that works as a page-turner.

The play’s not the only thing here; Arsén’s players intrigue as well.

Barker, Susan | Putnam (352 pp.)

$29.00 | Jan. 28, 2025 | 9780593718292

not just accepted but expected. An author doesn’t have to show us something new, because showing us something old in a new way provides its own thrills. What Barker offers here is essentially a vampire tale with subtle echoes of Dracula. Instead of trains and coaches, we have air travel. Telegrams are replaced by information gleaned from the dark web. And, in place of Bram Stoker’s bloodsucking revenant, we get an elusive woman with a camera and an eldritch god to feed. The story begins when two travelers, Jake and Mariko, discover that they share a terrible affinity. Both have lost loved ones to the same uncanny affliction, and both blame a strange woman who seems to be ageless. Mariko connects Jake with her dead brother’s wife. His interview with Mariko’s sister-in-law is both fascinating and chilling, as she describes her husband’s transformation from a charismatic artist to a monster she no longer recognized. Jake is convinced that the woman who seduced Mariko’s brother is the same woman who destroyed his best friend. After this, most of the text is composed of “testimonies” Jake gathers from other victims’ survivors and scenes from the perspective of the woman he’s hunting, and it’s a mess. However, horror fiction can survive—and even benefit from— mess. Dracula is a mess, but it’s a fascinating mess that moves at a fevered pace. Jake’s testimonies are repetitive and do nothing to advance the narrative, and the shifts in perspective seldom tell us anything new. The worldbuilding is rickety and kind of cringe. It turns out that the more you explain a terrible entity beyond human comprehension, the less terrible it gets. Similarly, the villain’s backstory makes her less, rather than more, frightening. An ungainly novel that undermines the promise of its premise.

Stuart Woods’ Golden Hour

Battles, Brett | Putnam (336 pp.)

$30.00 | Dec. 3, 2024 | 9780593331606

Battles continues his authorized takeover of Woods’ expansive turf with a tale that puts ex–CIA agent Teddy Fay in both the driver’s seat and the hot seat.

Ancient evil at large in the modern world. Horror has always been—at least, in its Anglophone form—a genre in which repetition is

Long before Teddy ended his career as a rogue intelligence agent by faking his death in a plane crash, he masterminded Operation Golden Hour, a task force devoted to taking down the Trust, in whose name Tovar Lintz funded terrorist operations around the globe. Now Tovar’s son, Felix Braun, chief executive of Braun Logistics and Security, has decided that it’s payback time against the agents behind Golden Hour, killing three of them and targeting the rest. Current CIA director Lance Cabot, one of the few people who know that Teddy’s still alive and flourishing under the guise of both Centurion Pictures producer Billy Barnett and Mark Weldon, star of Centurion’s new film Storm’s Eye, persuades him to go on the offense against whoever’s executing his agents and leaving a Trust signature behind. The publicity tour Mark Weldon is about to join in Italy for the screening of Storm’s Eye at the World Thriller Film Festival will provide the perfect cover, argues Lance. And he’s exactly right, for movie melodrama and offscreen maneuvering merge seamlessly with Teddy’s mission against Felix Braun, who’s very interested indeed to learn that the prime mover behind Golden Hour is still alive. Though there’s never any serious doubt about how all this will end, Battles plots much more tightly than Woods did—though that’s a low bar to clear—and fans of the series, first developed as a counterpoint to the ancient Stone Barrington franchise, won’t be disappointed.

Proof that the “golden hour” extends far beyond the ideal time to shoot movie exteriors.

Kirkus Star

Berlinski, Mischa | Liveright/ Norton (320 pp.) | $27.99 Jan. 21, 2025 | 9781324095200

A celebrated Shakespearean actress spends Thanksgiving rather differently than expected.

Berlinski follows acclaimed novels set in Thailand (Fieldwork, 2007) and Haiti (Peacekeeping, 2016) with a New York–based comedy of manners and morals featuring a brilliantly imagined female protagonist, Mona Zahid, one of the stars of a Shakespearean theater troupe based in the East Village. Until recently, the company was led by legendary director Milton Katz, but an article in the New York Times, filled with accusations of misconduct from a slew of actresses, led to his disgrace. Mona, herself “an out-and-out, unabashed Miltophile,” was not among the accusers. We meet her as she awakens in her Morningside Heights apartment on Thanksgiving Day to a full house— in addition to her surgeon husband, teenage son, and canine companion Barney, her in-laws and her college student niece, Rachel, are milling about. Absent is Rachel’s mother—Mona’s sister, Zahra—who died less than a year earlier, leaving Mona a stash of 150 pain pills of which there are now only six. Mona starts her day by taking two. Not long after, she hears the assembled family members begin to argue about Milton Katz and Donald Trump. She knows she should go out and save the day, but by then she has vaped some weed so strong she suspects it of being laced with “hallucinogenic toad drippings” and can only bring herself to put Barney on his leash and race out the front door, claiming she’s off to buy parsley. At this point the novel takes an amazing left turn; suffice to say, Mona will not be home for dinner. Readers who know their Shakespeare will thrill to Berlinski’s brilliant distillation of

the power and relevance of the plays and characters, but those who don’t will find they can easily come along for the ride. And a great ride it is. Wonderfully constructed, witty, warm, wise, and filled with an extraordinary sense of the relation between theater and life.

Bohman, Therese | Trans. by Marlaine Delargy | Other Press (192 pp.) | $16.99 paper | Jan. 14, 2025 | 9781635424188

A young woman’s platonic but passionate relationship with her mentor affords her insight into both the past and her own possible futures. When we meet the main narrator of this languid novel of ideas, she’s a young woman fulfilling an unpaid internship at Rydéns, a prestigious publishing house in Stockholm. A woman from a stolid middle-class Swedish family whose parents “dutifully went off to work without any particular career ambitions,” the narrator is overwhelmed by her own inexperience. She has to learn “from scratch: what to wear, how to use the printer and the photocopier…” Also, how to navigate the standard interpersonal politics of any office, which, in this particularly heady profession, also include entrenched positions on the nature of art, the function of publishing, and the ideology of commerce, as Rydéns struggles to place itself at the forefront of modern Swedish culture while still maintaining the prestige of a past steeped in traditional publishing values. Introverted and serious in nature, the narrator feels more kinship with literature of “genuine purpose” than she does with the sort of books her contemporaries are more likely to champion—easily marketable novels with “a clear message” but written in “dull prose, lying heavy and dead on every single page…as if the authors had followed a template for significant depictions of contemporary society.” The narrator’s iconoclasm soon catches the eye

of Gunnar, Rydéns powerful editor-inchief, whose own sensibilities are a reliquary of a rapidly vanishing age. Gunnar takes the narrator under his wing, grooming her to take over his position running Andromeda, the avant-garde imprint he founded. Over the next many years, the two form an enduring bond, centered around their love for ideas and the glimmering impossibility of something more they both feel developing between them. But when Gunnar’s ill health forces him into retirement, the narrator is left alone to examine the true nature of their relationship, of her identity within the systems she has helped to preserve, and of the art she celebrates. A confident, erudite novel, comfortable with developing at its own pace, Bohman’s latest adds to her growing cavalcade of young women with old, enduring ideals. Deeply provocative in its quiet contemplation.

Brandon, John | McSweeney’s (250 pp.)

$28.00 | Nov. 26, 2024 | 9781963270075

An old debt threatens to upend a young ex-con’s efforts to start his life over again.

“Nobody’s even,” aging crime boss Arthur Bonne tells the kid standing in his office. “There’s guys I help and guys I hurt. You fall in that first bunch. I’m asking you to do something for me, and if you do it right and don’t perform a full wop opera in my office, I won’t ask you to do nothing else.” The kid is Pratt Zimmer; he’s just 25, but he’s lived and lost enough to know better than to believe Bonne will ever leave him alone. Pratt’s fresh from a three-year jail stint for his part in a botched car theft that set Bonne back $250,000, and now Bonne expects more from him than just jail time to make them square again. Added to the money debt is an emotional one: Bonne partly blames Pratt for the death of his son, Matty, even though Pratt was behind

bars by the time his childhood friend’s indulgence in too many drugs got the better of him. “It could only be punishment,” Pratt realizes about the job. “That was the only thing that made sense. Forced penance for Matty.” In this novel and his others—especially Arkansas (2008) and Citrus County (2010)—Brandon explores the difficult circumstances surrounding desperate characters in humid, forgotten corners of the Southeast. Here, he’s crafted a compelling thriller set around Tampa in the 1990s as a young ex-con struggles to start his life over, even though the deck is stacked against him. It’s not just the job Bonne tells him to finish by the end of June— kill an accountant who’s stealing from Bonne—that’s the problem. Pratt’s still grieving the loss of his parents in a boating accident, coping with the guilt he partly accepts for not doing more to protect Matty from himself, and nursing a smoldering love for Kallie, Matty’s ex. He’s also facing a string of lowlife thugs, drug dealers, and a dirty cop as he tries to figure out how not to kill the accountant and still free himself from Bonne’s debt. Brandon keeps the story moving at a brisk pace, and his choice of a 1990s setting is especially interesting: It reminds readers how different—and how difficult—things like a stakeout were in a cellphone-free, GPS-less world. Brandon proves that even an impossible situation with only one outcome can suddenly yield an unexpected solution.

Callaghan, Jo | Random House (400 pp.) | $18.00 paper Jan. 7, 2025 | 9780593736852

The second book in the British Midlands–set Kat and Lock series reteams what may be crime fiction’s oddest couple, given that one half of the pair isn’t even human. A man has been found dead on Nuneaton’s Mount Judd, his nude body tied to a cross and his ears cut off. To

Offbeat stories from the provocative Can Xue blend the earthy and uncanny.

MOTHER RIVER

identify the victim and solve the crime, the Warwickshire police force’s DCS Kat Frank once again partners with Artificially Intelligent Detecting Entity Lock, the world’s first AI detective, who takes the form of a 3-D holographic image of a 30-something Black man. According to Professor Adaiba Okonedo—the Black scientist who created Lock and whose personal experience with racism has left her wary of cops—the idea is to use bias-free AI to “rebuild public trust and confidence in policing.” Also good: In a matter of seconds, the AI detective can do things such as “cross-check the victim’s facial characteristics, height and weight with all social media posts matching white men between twenty-five and forty in the Nuneaton area.” To mystery readers not predisposed to reaching for tech thrillers, the premise may sound intimidatingly geeky, but once Callaghan establishes her terms, it’s one fleet, accessible scene after another. For the Star Trek savvy, conversations between Kat and her literal-minded partner may recall exchanges with Mr. Spock (Lock: “Your entire theory is built upon nothing but your imagination”; Kat: “It’s called empathy, Lock”). The novel’s central question—should humans fear replacement by machines?—hums throughout, but never hinders the story’s forward momentum, and the plot’s big reveal is unlikely to be foreseen by even the AI-abetted reader.

This thriller may feature state-of-the-art AI, but its solid craftsmanship is timeless.

For more by Can Xue, visit Kirkus online.

Can Xue | Trans. by Karen Gernant & Chen Zeping | Open Letter (256 pp.) | $17.95 paper | Jan. 21, 2025 | 9781960385314

Thirteen offbeat stories from the provocative Can Xue blend the earthy and uncanny. The fiction of Can Xue (a pseudonym) owes debts to magic realism, surrealism, and the Modernists at their most abstruse, but she’s also consistently determined to make sure that familiar feelings of love and loss emerge through her work. In these stories, narrators are usually observing befuddling acts of nature: strange dark shadows emerging in the title story, stones appearing both in the soil and bodies of a community in “Stone Village,” mushrooms overrunning a field in “Something To Do With Poetry,” an elephant suddenly emerging in “Love in Xishuangbanna.” Sometimes, these unusual events serve as contemporary takes on folklore and allegory: The multiple narrators of “Smog City” describe their pollution-struck town with a diffidence that echoes our collective disengagement from climate change—“People’s windpipes and lungs were getting so used to the smog that they accepted it as ordinary air, and let it pass through their bodies quietly and unimpeded.” But more often, the storytelling is unmoored from big themes and mainly cultivates a mood of strangeness and wonderment, as characters transition from everyday life into something weirder. In “The Neighborhood,” a retiree’s concern about the disruptive construction of a sports

facility leads him to a series of shifts: the arrival of feral cats, and growing numbers of Qigong practitioners, thanks to whom “every tree and blade of grass in the garden contained their breath, revealing the traces of communicating with them.” In “At the Edge of the Marsh,” a young man is drawn to a town elder dismissed as “defective,” but through him enters into a more dreamlike and mystical relationship with nature. Translators Gernant and Chen keep the prose simple at the sentence level while allowing the oddness of the storytelling to bleed through. Mind-bending but warmly delivered domestic tales.

Chambers, Clare | Mariner Books (400 pp.)

$30.00 | Nov. 12, 2024 | 9780063258228

The arrival of a mysterious recluse at a British psychiatric hospital unlocks secrets from the past and sets in motion possibilities for the future. In 1964, Britain has not yet been reinvigorated by the youth revolution or the “Beatles phenomenon,” and many of its people are still marked by their World War II experiences; this is a stifling world of good manners, bad food, and limited opportunities for women. Thirty-fouryear-old Helen Hansford, however, has cracked the mold by choosing to work as an art therapist in Westbury Park, a psychiatric hospital, where she has met and begun a consuming affair with charismatic, married doctor Gil Rudden. An unusual patient, William Tapping, 37, arrives at the hospital; he doesn’t speak and hasn’t left his house in decades. His last living relative having died, Westbury Park becomes William’s home, a refuge where he can practice his considerable creative skills in Helen’s art class. At this point, the narration opens up to intersperse Helen’s story with chapters from William’s perspective, slowly revealing the reasons for his

isolation, withdrawal, and silence. In fastidious prose well suited to the novel’s period setting, Chambers traces William’s story back in time while advancing Helen’s growing difficulties with Gil and efforts to aid her struggling niece, Lorraine, now also a patient. While evocative of a buttoned-up time, the novel’s consciously understated tone (bad things are referred to as “unpleasantness”) muffles the few dramatic moments. More persuasive is the mood, redolent of post-war adjustments, and Chambers’ quiet but precise observations of circumstance (often drab), options, and individuals. Despite some two-dimensional minor characters, this is a finely detailed and modulated work, based on true events, that looks benignly on its characters and their trajectories. A composed period piece that pays sharp attention to the little things.

Chen, Karissa | Putnam (512 pp.)

$30.00 | Jan. 7, 2025 | 9780593712993

Major political, military, and economic events in 20th-century China affect the lives and romance of two Shanghainese over many decades. By moving around in time and place—including Shanghai, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the U.S. from 1938 to 2008—Chen illuminates the parallels and relationships among key moments in China’s recent history. Intertwining the macro and micro, she makes readers care deeply about the impact of history on her characters’ very private lives. Even the characters’ names change to denote their code-switching based on geography and situation. Star-crossed lovers Suchi and Haiwen meet as first graders in pre-WWII Japanese-occupied Shanghai. A family crisis caused by Shanghai’s shifting politics forces Haiwen to enlist in the Nationalist

Army in 1947, before he can propose to Suchi. After Mao’s defeat of Chiang Kai-shek, Suchi lands in Hong Kong, and Haiwen in Taiwan; they meet briefly in the 1960s and do not communicate again until they cross paths in 2008 Los Angeles. Though they follow different paths and marry other people, they remain emotionally “tethered to each other,” as predicted in 1945 by a fortune teller who also described the concept of “mingyun”—a person’s “personal destiny” as determined by a combination of their intrinsic nature and chosen actions— which is so important to the story. Chen avoids romanticizing or demonizing any of her characters. Nuances of class and ethnicity, as well as political identity, come to life as she digs into crevices of ambivalence and muddled motivation. Suchi marries out of financial desperation. Haiwen abandons his passion for the violin to fight for a cause he knows is lost. Suchi’s father, a bookstore owner with progressive ideals, finds himself disillusioned once the Communists he backs take over. Haiwen’s cosmopolitan, Anglophile parents are vilified by both Nationalists and Communists. This is historical fiction at its most effective. Romantic lyricism and hard-edged realism merge in this compelling novel.

Child, Lee | Mysterious Press (256 pp.)

$28.99 | Sept. 3, 2024 | 9781613165669

A collection of short stories featuring the seedier side of life by one of the country’s best crime writers.

“Fabergé eggs they ain’t,” Child admits in the foreword, and he’s right. These are unfancy little eggs—to stretch the metaphor—that don’t overshadow his novels, and yet they satisfy our innate craving to read about other people’s failings and misadventures. Some of them end in twists that harken back to

O. Henry, such as “Ten Keys,” where a drug-running escapade ends in a surprising way. It also has the book’s best line: “He was a white guy…the product of too many generations of inbred hardscrabble hill people, his DNA baked down to nothing more than the essential components, arms, legs, eyes, mouth.” “My First Drug Trial” is also like that, with a last line that pops off the page. In “The Bodyguard,” a guy is hired to protect a young woman who is the high-value target of a rich and prominent couple. A nice twist at the end makes the bodyguard doubt himself, and the reader might smile. And then, in “The Greatest Trick of All,” there’s a professional killer who can nail you from a thousand yards and thinks he can’t be stopped. Said “greatest trick” is getting paid twice for a hit, but in this case, he might be mistaken. Most of the stories won’t keep you on the edge of your seat, but they’re easy, brief explorations of the darker nooks and crannies of humanity. But one story takes a sad turn into the past: In “New Blank Document,” a freelancer is assigned to write a sidebar about the brother of a modestly accomplished Black American artist living in Paris. The crucial, heart-rending story has to do with the fate of a second brother not everyone knows about; think Jim Crow. Finally, the title tale features a narrator you’d never want to meet in real life. Twenty tasty morsels, served over easy.

Coble, Colleen & Rick Acker

Thomas Nelson (352 pp.) | $18.99 paper | Nov. 12, 2024 | 9780840712578

Af ter losing her husband, grandmother, and job in quick succession, a young woman strives to uncover a criminal conspiracy while falling back in love with her hometown and its people.

A year after her husband, Jason, died in an accident, attorney Katrina Foster arrives at Talk, Inc., the Silicon Valley company where she’s employed, to find the FBI raiding the premises. David Liang, the chief executive, is under investigation for embezzlement and has apparently fled the country, leaving Liv Tompkins, his pregnant girlfriend—who’s also the company’s chief technology officer, and Katrina’s friend—behind. On the same day, Katrina’s beloved grandmother dies of a heart attack. Shattered by upheaval and loss, Katrina travels home to North Haven, California for the funeral, where she learns that she’s inherited her grandmother’s restaurant. With a lead on a new job back in Silicon Valley, she offers to sell the business to handsome restaurateur Seb Wallace, a local man with a tragic past who has become a major success. Katrina also has a secret: Liv loaded a prototype of Talk’s AI software onto her phone after Jason’s death, and she often speaks to the chatbot of her dead husband for comfort. She starts asking him more questions about the night he died, and he finally says, “I think I was murdered.” Returning to the homey comfort of North Haven, Katrina vows to uncover the truth behind Jason’s death, which involves a mysterious Satoshi egg that contains the code to $30 million worth of Bitcoin, a possible international assassin, and a potential mole in the FBI. She’s helped by her family, Liv, and Seb, with whom she falls deeper and deeper into attraction. It’s a high-octane thriller with the grounding touches of Katrina’s Norwegian heritage, the hygge of North Haven, and a very sweet romance between two likable, vulnerable people. Romantic suspense comfort food—just like waffles with cloudberry cream.

Corin, Joshua | Thomas & Mercer (287 pp.) | $16.99 paper Dec. 10, 2024 | 9781662523533

The line between fact and fiction is blurred when a dogged daughter seeks the truth about her mother’s murder. In 1995, when AOL chat rooms are new and all the rage, 15-year-old Bostonian Katie McCann, a self-professed “book-obsessed dork,” finds a kindred online spirit in 19-year-old Dev, who’s “WmbleyLnDet” to Kat’s “KMcCann14.” Their shared passion is renowned mystery writer Carissa Miller, who created the witty and charming detective Adrian Lescher, basing him on noted criminologist Alik Lisser; Miller’s reputation has grown even more glamorous since her mysterious disappearance. Kat’s interest isn’t random. When she was 6, her mother, Barbara, was murdered, and Lisser was instrumental in proving that the crime was committed by her father, Bill, who was convicted and died in prison. Dev, who’s tracked down Lisser’s phone number and address, presses Kat to contact him. When Lisser schedules a speech at Harvard, Kat is convinced to try. Lisser, it turns out, is equally interested in her. At the end of their long meeting, Kat is convinced that he, not her father, killed Barbara. Many twists follow. In addition to encouraging nostalgia for the early days of online chat, before skepticism of other people’s identities and agendas became the norm, Corin also includes many references to mystery literature and film. The first-person narrative nicely captures Kat’s passion and youthful recklessness;

A rabbit-hole whodunit full to overflowing with Easter eggs.

the title is a warning to both Corin’s resourceful heroine and his readers. A rabbit-hole whodunit full to overflowing with Easter eggs.

Dervis, Suat | Trans. by Maureen Freely Other Press (192 pp.) | $16.99 paper Dec. 10, 2024 | 9781892746931

A man reflects on the crime that sent him to prison— and on his uncertain future. Turkish author Dervis’ novel, first published in 1957, is now available to Anglophone readers in Freely’s tautly paced translation. The title character is a former medical student named Vasfi who’s leaving prison after having spent more than 12 years there, sentenced for his role in a man’s death. Initially, his mood upon reentering the wider world is bleak: “To look at the people around him and think of himself as a murderer was a torment he could barely endure.” Eventually, he thinks back over the events that sent him to prison, which related to his infatuation with Zeynep, a woman who lived in his neighborhood. He longed to be with her, but fate had other plans, and she ended up engaged to his greatuncle. When he confronted her with his feelings, she rejected him and went on to reveal that there were aspects of the situation—including the fact that she had previously been married and divorced, and had a 4-year-old child—of which he was completely unaware. His unresolved feelings remained an issue, however, and he eventually got into a fight with his cousin Nuri when Nuri claimed that Zeynep had been unfaithful to her new husband. That fight resulted in Nuri’s death and Vasfi’s prison term. In her introduction, Freely accurately describes this book as “a social-realist page-turner.” It isn’t until the long flashback has ended that the book takes a more philosophical turn, as an

Star-crossed skaters whiz through decades of melodrama on and off the ice.

increasingly destitute Vasfi wanders through the city overcome by desperation and self-loathing. And he gradually realizes something: “His Zeynep—the incomparable Zeynep of his youth—no longer existed.” It’s not until after this moment that he can find a path toward redemption. A melancholy look at dashed illusions.

Faladé, David Wright | Atlantic Monthly (304 pp.) | $28.00 Jan. 21, 2025 | 9780802164063

After World War II, a young French Jewish woman has romantic liaisons with two very different Black men.

Faladé’s second historical novel, after Black Cloud Rising (2022), is set in Paris and its suburbs and revolves around a young woman named Cecile Rosenbaum, whose experiences mirror those of the author’s mother, which he described in the New Yorker in 2022. The book opens with a chapter set in 1943; while the family is completely secular, Cecile’s grandparents and other Jewish neighbors are lost to the purge and she herself is hastily confirmed and enrolled in Catholic school. The second chapter jumps ahead to 1947, when Cecile meets a Senegalese French girl named Minette on the bus to the Communist Youth Conference. Through Minette, Cecile will connect with a young West African man named Sebastien. Both are acutely aware of politics and their relationship is plagued by ideological questions,

laid out rather pedantically. “Yes, she was white and he black, her of the colonizers and him the colonized, but what was each one willing to give, and to give up, in order to be together?” As Cecile and Seb struggle to find their way, she meets an African American GI in a jazz club. Mack Gray is from “KC, Baby!” He calls her Baby exclusively rather than her name, speaks in a Southern dialect, and introduces her to soul food, but is also eager to understand her situation and background. He concludes, “She was white and from money, but the money long gone...both of them easy targets as a result, yet neither lying down for nobody—not for nobody.” Though the characters and settings of this novel are well-researched and carefully drawn, the memoir version of this story in the New Yorker is more compelling than the fictionalized one. Vividly dramatizes issues of race and politics in turbulent post-war Paris.

Fargo, Layne | Random House (464 pp.) $28.00 | Jan. 14, 2025 | 9780593732045

Star-crossed figure skaters whiz through decades of melodrama on and off the ice.

Fargo’s latest feature pairs skaters entwined by destiny and irradiated by fan and media obsession, as she cleverly tells her tale by alternating between narrative sections and clips from the script of a fictional 2024 documentary called The Favorites: The Shaw & Rocha Story. Katarina Shaw and Heath Rocha

are “small-town Midwestern trash,” both orphans, he of mysterious origins. Teen lovers, they enter the world of skating at the 2000 Nationals, where they meet their rivals, brother and sister skaters Garrett and Bella Lin, the privileged twin children of figure skating icon-turned-coach Sheila Lin (and an anonymous Sarajevo Olympic Village sperm donor). For the next 14 years, violent passions, bloody on-ice accidents, bedroom betrayals, sabotage, paparazzi-driven scandals, and nonstop cliffhangers—“Unfortunately, it was only the beginning”—lead up to an epic brouhaha at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Russia, by which time the reader’s capacity for outrage and surprise has gotten quite a workout. But don’t give up in the stretch: “NBC Sports commentator Kirk Lockwood reports live from the Sochi Olympics. ‘In all my years covering skating,’ he says, shaking his head solemnly, ‘I’ve never seen anything like this.’” Though the stereotype-driven characterizations of the skaters are a couple dimensions short of real or relatable—Heath in particular is a furious cipher—Fargo does a nice job with the narrators of her documentary. One of them, a former skater turned gossip blogger named Ellis Dean, can be relied on to spill the tea (“That program was the most passive-aggressive shit I’d ever seen— and I’m from the South, honey”), while an uptight U.S. Figure Skating official dryly tows the party line: “Ice dance can have a certain sensuality to it, yes. Many programs express the beauty of the love between a man and a woman. But what Ms. Shaw and Mr. Rocha were doing bordered on vulgarity.”

After all the histrionics and hormones, the unlikely ending Fargo bestows on her characters is a hoot.

Colleen Hoover–style romance heads to the Olympic rink. Buckle up.

Gardiner, John Rolfe | Illus. by Maria Nicklin Bellevue Literary Press (224 pp.) | $17.99 paper | Jan. 14, 2025 | 9781954276321

A clutch of wry coming-of-age tales, the first in 20 years from the veteran Gardiner.

deafness and embrace of sign language slyly reveals everyone’s failures to better understand themselves.

Foursquare but often affecting studies in domestic anxiety.

For more by Layne Fargo, visit Kirkus online.

The 10 well-turned stories in this collection usually feature narrators looking back on awkward but meaningful moments in their youth. The narrator of “Tree Men” is a failed academic who comes into himself as an assistant for a tree service. In the title story, a man recalls an ill-advised flirtation with a hard-to-read classmate at a Christian college. In “Virgin Summer,” a young man’s student-exchange trip to France offers some historical and social enlightenment. “Freak Corner” looks back to 1953, as the narrator explores the history of his deaf sister, a transgender neighbor, and the neighborhood bullies who tormented them both. Gardiner’s narrators are writing from a position of maturity, and some stories feature more grown-up types: “The Man From Trenton” centers on a semi-successful writer and a noisy conflict he had with a man on an Amtrak quiet car, while in “Familiars,” two couples who’ve taken vacations together for 17 years find their friendship beginning to fray. But even in those cases, Gardiner is interested in his protagonists’ past youthful foibles and how they shaped the flawed adults they became. Gardiner began publishing in the early 1970s in publications like the New Yorker, and his prose sometimes has an overly mannered, slightly fusty feel. One man, fearing death, “wondered if he was getting the scythe man’s signal,” and a plot point about a viral blog post in “Familiars” feels untenable. But at his best, he has a nuanced sense of characterization and a knack for writing gracefully about stress without undercutting the tension. That talent is strongest in “Freak Corner,” where the narrator’s sister’s misunderstood

Goldberg, Tod | Soho Crime (304 pp.)

$25.99 | Oct. 29, 2024 | 9781641296137

Eleven dark tales offer a perplexing take on the Festival of Lights. Christmas crime stories often focus on the more secular aspects of the holiday: shopping, presents, parties, snow. But many of the stories Goldberg selects seem to regard Hanukkah—a relatively minor festival—as deeply religious and widely observed, even by secular Jews. The tension between characters’ focus on celebrating the holiday correctly and the egregious aspects of their personal behavior is unsettling. In David L. Ulin’s “Shamash,” an aging man becomes increasingly obsessed with his grandmother’s menorah as his traumatic past prods him to violence. In James D.F. Hannah’s “Twenty Centuries,” a mother turns her back on the death of her adult child to go home and light candles with her new husband. A spurned girlfriend uses a Hanukkah party to get revenge against her boyfriend in Liska Jacobs’ “Dead Weight,” and the annual Hanukkah party at Sucks to Be U Records, with a carefully curated menu of Jewish delicacies, has an equally grisly finale in Jim Ruland’s “The Demo.” A selfdiagnosed sociopath loses it when her no-good brother-in-law disrupts her family’s latke celebration in Stefanie Leder’s “Not a Dinner Party Person.” And editor Goldberg seems to regard his hero’s string of thefts, drug deals, and causal mayhem as some sort of Maccabean victory. Only in Lee Goldberg’s “If I Were a Rich

The novelist and critic surprises readers with a delightful book set in a midcentury New York women’s hotel.

BY MARION WINIK

STILL IN HIS 30 s , novelist and cultural critic Daniel M. Lavery has a long list of achievements. He founded the website The Toast, had a five-year run as Slate’s “Dear Prudence” columnist, and published several books that retell classic texts from a humorous feminist perspective. Among them is The Merry Spinster (2018), which Kirkus, in a starred review, called a “wholly satisfying blend of silliness, feminist critique, and deft prose.”

In 2020, a hybrid memoir—that addressed, among other things, his gender transition—made a splash and received another Kirkus star. Of Something That May Shock and Discredit You , our critic enthused, “Everyone should read this extraordinary book.”

That same year, the one where we all stayed home, Lavery went deep into the reading that would lead him to write Women’s Hotel (HarperVia, Oct. 15), about a group of characters who live and work at the fictional Biedermayer Hotel in 1960s New York. We caught up with him over Zoom to discuss this latest Kirkus-starred feat of literary magic. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Women’s Hotel seems quite different from your previous work. Would you agree? I think so. After the memoir, I was interested in writing something removed from my own experience—I wanted to write the kind of book that I had been reading a lot of. During the pandemic, I spent a lot of time with books from an imprint of Dean Street Press called The Furrowed Middlebrow. They specialize in reprinting lesser-known British, Irish, and American

women writers from about 1910 to 1960.

So classic—or at least existing—texts did play a role.

Yes, and I was also influenced by novels like Rona Jaffe’s The Best of Everything and Mary McCarthy’s The Group. I love the kind of book that describes a lot of little moments in the lives of quite a few people.

I had the feeling, reading Women’s Hotel, that it was

not of the present time. It felt like something I dug up at a yard sale, a forgotten gem from another era. I’m thrilled to hear you say that! When I finally got to see the cover of the book, I felt they got it just right. While it’s not ever totally possible to recreate a historical period that you didn’t live in, I tried to think about what novels from that era had to say about friendships and resentments and ambitions, and the way that people talked to and about one another. I gave my characters attitudes and perspectives that I could feel affection for but that felt totally different from [my own].

What other research did you do?

I spent some time at the New York Public Library gathering historical and architectural details and also found a few newspaper columns

about life at women’s hotels. Three of the characters in this book are loosely based on real people.

Do tell.

Stephen, the elevator operator, is partly inspired by Stephen Donaldson, the first openly queer student to attend Columbia (it’s Cooper Union in the novel). Like his namesake in the book, Donaldson actually contacted the dean, via a social worker, after his acceptance and asked if they would register a “known homosexual.” He was told he could attend if he promised to enter psychoanalysis and not seduce the other students.

Lucianne is loosely based on Lucianne Goldberg, who founded the Pussycat League, a sort of tongue-incheek anti-feminist organization of the 1960s, although the connection there is much more tenuous. The

glamorous character Gia Kassab, who comes to New York with the intention of marrying a man her mother dated when she was growing up, is inspired by Joan Brady, who ended up marrying a midcentury writer named Dexter Masters, whose work I happen to love. She published a beautiful piece in the Daily Telegraph after Masters’ death called “Why I Stole My Mother’s Lover,” and I just adored it. It was so frank and remorseless and libidinal.

The phenomenon of the women’s hotel is discussed in the foreword, advancing the idea that the thing the residents share is that they just don’t want to be home. That seems contrary to one of the most universal motivations in literature. These are characters who, both for reasons they could articulate and ones they couldn’t, are avoiding living at home. Some feel they failed, some have been rejected, others have just sort of washed out. Because the book is set right before there’s a significant counterculture, they are waiting for a moment that hasn’t quite arrived—but when it does, it will help them make sense of their lives.

Are there characters you particularly identify with?

Yes—Katherine, Lucianne, and Ruth, though they’re all quite different from one another. With Lucianne, it’s the perverse desire to tweak things, to poke at situations sometimes to my own detriment. With Katherine, it’s obsessional worry about being rejected, which can itself become very selfish.

And like Ruth, I know the feeling of sometimes just wanting to get out of everything and glom onto somebody else’s life.

Katherine is a recovered alcoholic with a story that seems straight out of the Big Book. Are you sober? I am. I got sober in 2013. But alcoholism looks very different in Katherine’s life versus mine. I did read through the Big Book , and thought quite a bit about Alcoholics Anonymous. Here’s a midcentury institution that is actually

becoming more and more influential, unlike the women’s hotel, which is on the opposite trajectory.

Katherine’s relationship to AA is meant to show that this is something understood at the time as brand new and transformative. This is the wave of the future. This is going to be the thing that actually helps people.

Speaking of the downward trajectory of the women’s hotel, let’s talk about one of the throughlines of the plot, the end of breakfast

These are characters who, both for reasons they could articulate and ones they couldn’t, are avoiding living at home.

service at the Biedermayer. The first sentence of the book tells us, “It was the end of the continental breakfast, and therefore the beginning of the end of everything else.”

I love books that are interested in food and creature comforts. I find that so much of my ability to be a convivial, caring person rests on when I get my little meals and treats. As long as I have them in exactly the right order and configuration, I’m a delight. When I don’t, my ability to be a person in the world often really falls apart.

When their free breakfast goes away, and the Automat is shutting down, and the availability of big, well-made breakfasts and lunches around the city is disappearing, everybody has different reactions to it. Lucianne tries to score meals from dates and former co-workers. Other characters start stealing. Others eat less. Some try to pretend it isn’t happening.

The Biedermeier is part of a class of institutions that grew up in the 1920s and ’30s— boarding houses, automats, kitchens and cafeterias serving cheap batch food—that supported the growth of an artistic middle class in major cities. As the book unfolds, that infrastructure is crumbling. My characters are living through this period of change. Because they are funny and interesting and resilient, they will make it through, and go on to live other ways—but it is, I think, a loss.

Marion Winik hosts NPR’s podcast The Weekly Reader.

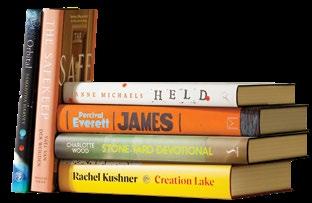

Percival Everett and Rachel Kushner are among the authors contending for the award.

The shortlist for the Booker Prize has been revealed, with Percival Everett and Rachel Kushner among the authors in contention for “the best sustained work of fiction written in English by authors from anywhere in the world and published in the U.K. and/or Ireland.”

Everett made the shortlist for James, his retelling of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the point of view of the enslaved Jim. The novel was a finalist for the Kirkus Prize and also longlisted for the National Book Award.

Kushner was named a finalist for Creation Lake, which also made the National Book Award longlist. She was previously longlisted for the Booker in 2018 with The Mars Room

Samantha Harvey was the sole British novelist to make the longlist, for Orbital, which was previously shortlisted for the Orwell Prize for Political

Fiction and the Ursula K. Le Guin Prize for Fiction.

Australian author Charlotte Wood was named a finalist for Stone Yard Devotional, alongside Dutch writer Yael van der Wouden for The Safekeep and Canadian author Anne Michaels for Held

Edmund de Waal, chair of this year’s judging committee, said in a statement, “Here is storytelling in which people confront the world in all its instability and complexity. The fault lines of our times are

For more literary awards news, visit Kirkus online.

here. Borders and time zones and generations are crossed and explored, conflicts of identity, race and sexuality are brought into renewed focus through memorable voices.”

The winner of the prize will be announced at a London ceremony on Nov. 12.

—MICHAEL SCHAUB

Man” does the hero recognize the irony of his appropriation of Jewish cultural symbols in facilitating his crimes. Feh.

Josaphat, Fabienne | Algonquin (288 pp.)

$29.00 | Dec. 3, 2024 | 9781643755885

A coming-of-age story mixes Black Panther Party ideals with besotted romance. It’s 1968 and Nettie Boileau, the beautiful, orphaned daughter of a murdered Haitian doctor, arrives in Oakland, eager to assist with the first free medical outreach of the Black Panther Party. “If she couldn’t do this, then what point was there in even living?” 20-year-old Nettie asks herself, in a story built of breathless interior rumination. Her best friend, Clia Brown, is crushing on her, but the novel’s opening scene supplies Nettie with another reason to exist when she “lock[s] eyes” with the capable Panther Party captain, Melvin Mosley. He has been called in to dispatch the racists menacing the home of a boy with sickle cell anemia, but “what distressed her the most was how handsome he was.” In due course, Melvin will give Nettie a gun and a pregnancy, two time-honored plot devices. Nettie takes both to the Midwest, following Melvin to his assignment to help open an Illinois chapter of the party. Young Nettie soaks up the rhetoric of Stokely Carmichael; she “caught those words like falling rain, swallowed them like holy water.” But the high of revolutionary ardor precedes the low of Melvin’s infidelities and the bitter winters of Chicago. Worse, the FBI moves in to shut down the Panthers, and it’s Nettie and her body that pay the price. Josaphat, a Haitian-born writer living in South Florida, quotes Huey P. Newton, Fred Hampton, and James Baldwin to strong effect. Police are “pigs” here, and the Panthers’ newspaper “was like a portal,” reporting “who in the community had been imprisoned, whose

death went uninvestigated, whose bail needed to be posted, and who needed legal assistance.” The author is drawing clear parallels between police violence then and now. In her acknowledgements, Josaphat writes that she has “always been fascinated by the minds of radicals.” Unhappily, her cliched prose makes a poor container for the history she reveres.

A strong premise set amid the Black Panther Party falters in its execution.

Korn, Gabrielle | St. Martin’s (304 pp.)

$29.00 | Dec. 3, 2024 | 9781250323484

A group of survivors finds new ways to live and love as the world burns around them. Set in 2041 and 2078, Korn’s dystopian sophomore novel serves as both a prequel and sequel to her debut novel, Yours for the Taking (2023). In 2041, the world is falling apart due to rapidly accelerating climate change. As storms, fires, and viruses destroy cities, millions of climate refugees find themselves without homes. Kelly, a hacker and activist, is traveling across the United States and writing letters to the daughter she left behind. Seven years earlier, Kelly joined a group she believed would save the world. Starting from her childhood, Kelly recounts in devastating detail how and why she left—and, even more importantly, why she’s returning. In 2078, a group of queer characters seeks out new ways of surviving in a world that is unimaginable and nearly uninhabitable. Max, a nonbinary person who grew up in the Winter Liberation Army, discovers truths about their home that make it impossible to stay. Survivalist Orchid sets out to save her ex-girlfriend Ava from the Inside Project, a highly selective, government-funded climate protection program. Meanwhile, Ava and her daughter, Brook, have escaped the Inside after unearthing a deadly secret. Finally, climate refugee

Camilla decides to wait for her friend Orchid to return, while their group travels further north for safety. As Max, Orchid, Ava, Brook, and Camilla try to survive both together and apart, they begin to discover the known and unknown connections among them. As the novel races to a finish, the dual story lines converge satisfyingly, if a bit too conveniently. However, Korn’s worldbuilding and character development (especially Kelly) breathe life into the novel as it explores societal collapse, political conspiracies, and the pliable nature of historical narratives. The novel ends with a perfect blend of sadness and hope that refuses to downplay the dangers of climate change nor discount humanity’s desire to survive.

A page-turning queer, feminist dystopia.

Littell, Robert | Soho (208 pp.)

$25.95 | Jan. 28, 2025 | 9781641296861

The veteran spy novelist indulges what he calls an “obsession” with Leon Trotsky to imagine the Russian’s brief New York sojourn. Born Lev Davidovich Bronshtein, Trotsky took his betterknown name from one of his prison guards. Littell mentions in a foreword that his own father was born Leon Litzky, but he had the surname legally changed in 1919 to Littell because of its resemblance to the infamous revolutionary’s nom de guerre. This nominal link is why, the novelist says, he “couldn’t resist fantasizing” about Trotsky’s 10 weeks in New York just before the 1917 revolution erupted. Trotsky sails with his longtime companion and their two sons in early 1917 to New York, where his fame has preceded him. J. Edgar Hoover conducts his immigration interview, a likely anachronism, and the press greets him on the pier. Trotsky moves into an apartment in the Bronx and begins writing for the Russian-language

newspaper Novy Mir and the Jewish Daily Forward. He begins an affair with a journalist named Frederika Fedora, who has ties through her father to Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata. He gives speeches and argues with various emigres and sympathizers, including Nikolai Bukharin and Eugene Debs. The average reader might be mystified by the factional nuance and rhetoric that emerge among committed Socialists, Bolsheviks, and Mensheviks. The U.S. visit comes to an end when the czar abdicates and Trotsky feels he must return to a Russia where revolution has begun again. While the historical characters are little more than foils and talking heads, Littell creates a wellrounded personality in Trotsky. Some of the character development derives from his highly active and vocal conscience, whose contrarian bent constantly tests the man’s convictions and assertions. And note that Trotsky associates his conscience with a “childhood nemesis” named Leon Litzky—which may make sense if you’re fantasizing about an obsession.

A colorful but uneven venture into historical fiction.

Kirkus Star

Muchemwa, Chido | Astoria/House of Anansi Press (176 pp.) | $17.99 paper Oct. 8, 2024 | 9781487012465

In her debut collection, Muchemwa—a Zimbabwean writer living in Toronto—deftly chronicles both family tensions and national struggles. The first three stories in this empathically rendered collection provide a useful summary of Muchemwa’s skill at capturing emotional complexity and avoiding cliches. “Who Will Bury You?,” “This Will Break My Mother’s Heart,” and “If It Wasn’t for the Nights” play out like a chamber drama: A young

Zimbabwean woman moves to Canada, where she falls in love with another woman; back home, her devoutly Christian mother wrestles with her own feelings. In three stories, Muchemwa takes readers inside the heads of mother, daughter, and the daughter’s fiancee in turn, taking each of their struggles seriously and arriving at a moving conclusion. These three pieces start the collection on a high note, and Muchemwa’s attention to detail throughout the book pays welcome dividends, even down to small things like characters’ taste in books. A character in one story describes reading Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, while two others bond over their shared love for Anne McCaffrey’s science fiction novels. Muchemwa skillfully deploys references to books and music where you least expect it, as when the narrator of “Finding Mermaids” goes looking for a woman who is said to be “evidence of the power of mermaids.” The person she finds is far more idiosyncratic: “She wore a headband made from goatskin and a cowhide pinned around her shoulder, but under the hide was a black System of a Down T-shirt with the sleeves ripped off.” Elsewhere, in stories like “Kariba Heights” and “The Last of the Boys,” Muchemwa steps back in history, exploring Zimbabwe’s colonial past and struggle for independence. The total effect of this notable collection is of an author demonstrating her range and skill. An impressive and expansive collection.

Parlato, Terri | Kensington (304 pp.)

$28.00 | Dec. 24, 2024 | 9781496738622

Marital dysfunction is complicated by an inexplicable kidnapping. After a short prologue that finds Nathan Liddle helpless “as a bug on its back” and expecting to be killed at any moment by his beautiful wife, Eve Thayer, a psychiatrist, the story flashes back three weeks to the couple’s

strained marriage. While their new baby, Rosewyn, is the proverbial bundle of joy, her needs and bouts of ill health add strain to their relationship. So does Nathan’s careless extramarital affair with a free-spirited woman named Nicole. A parallel plot thread follows Det. Rita Myers and her handling of multiple local crimes. The two threads converge when Rosewyn is kidnapped from the home of babysitter Barbara Singleton. For a while, suspicion falls on Donald Barry—a disgruntled patient of Eve’s—and his wife, Gail, but some strange additional twists widen the circle of suspects. The surprise return of the baby doesn’t solve the original crime; it just deepens the mystery. Parlato’s thriller is breezy but a bit muddled, full of feints, shadowy suspicion, and an 11th-hour murder. Short chapters ricochet among the first-person perspectives of Eve, Nathan, and Rita, making for a quick read and giving the illusion of pace. Both Eve and Rita commiserate about their jobs and their struggles to achieve the elusive work-life balance, Eve with her old friend Rachel and Rita with her brother Danny. The overall effect resembles a Lifetime thriller: half skillfully executed soap opera, half diffuse whodunit.

A lively pop thriller with a pair of hard-working heroines that could almost have been written by AI.

Ragan, T.R. | Thomas & Mercer (287 pp.) | $16.99 paper Nov. 5, 2024 | 9781662517303

The murder of a bullying ex-journalist threatens to rip the lid off the many scandals plaguing a toney Sacramento neighborhood. Time was that Rosella Marlow was widely respected by her professional peers and her neighbors. In fact, her lovingly preserved home in the Fabulous Forties district won the Best House on the Block award twice. But since her husband and son were

killed in a car accident and her house has lost top honors to Chloe Leavitt’s far inferior place, she’s gone off the rails, spying on her neighbors, vowing vengeance for their slights, and becoming the recipient of anonymous notes (“I Know What You Did”) and menacing stick figures. Even Shannon Gibbons, the nobody she’s plucked out of nowhere and moved into the Forties to serve as her researcher and footrest, is put off on their first meeting by her brusque manners and casual cruelty. When Shannon returns the following day, she finds Rosella dying after having been stabbed in the neck by a letter opener. Since there’s no husband left in the picture, Det. Seicinski and Det. Toye elevate Shannon to the top of their list. But that’s only because they don’t know about all the secrets held close by Chloe, who quickly bonds with Shannon, and by Jason and Dianne Abbott, Kaylynn and Nicolas Alcozar, Becky and Holly Bateman, and, yes, their children. Seicinski and Toye will make two arrests before the cascade of unsurprising surprises reveals a killer only Shannon will have failed to suspect. Expertly paced revelations that disturb the heroine and her new neighbors a lot more than the reader.

Rishøi, Ingvild | Trans. by Caroline Waight | Grove (192 pp.) | $20.00 Nov. 19, 2024 | 9780802163493

A Christmas story about a 10-year-old Norwegian girl who believes in miracles, and her 16-year-old sister.

“Hello, two motherless children and an alcoholic here, can you please give us two more weeks?” This is the phone call that Melissa resorted to just once, according to her little sister, Ronja. It’s the full truth, which the sisters try to keep hidden—from the neighbors, from the schools, and even from themselves. The story focuses on one Christmas season when, ever so briefly, their father dries out

and gets a job as a Christmas tree seller before once again falling apart. As he disappears into bars, Melissa takes over his job, doing the work before and after school, but for less pay. Soon, her coworker Tommy brings Ronja in to convince customers to buy decorative wreaths so he and the girls can split the commission. She hawks them, saying that “all proceeds go to children in need!”—that is, she and her sister and Tommy’s soon-to-be-born child. But Ronja is too young to be working at the tree market, so her efforts must be kept secret from the owner. Though the sisters love their father, he’s unable to care for them and regularly put food in the fridge, so they’re desperate. But as much as they hope no one sees their situation, everyone does—and just a scant few try to help: There’s Aronsen, the across-the-hallway neighbor who feeds Ronja a few meals and irons her Christmas costume. The caretaker at school who shares his lunch with Ronja every day. Ronja’s friend Musse and his dad, who find her wandering in the cold and try to get her sister to take her to the emergency room. Ronja is convinced that when things are at their worst, a miracle can happen, because sometimes they just do. But then again, sometimes they don’t.

A heart-wrenching tale of children trying their utmost to take care of each other.

Ross, Adam | Knopf (528 pp.)

$29.00 | Jan. 7, 2025 | 9780385351294

A teen actor in 1980 Manhattan grapples with the consequences of fame, his eccentric family, and the advances of a family friend. This longawaited follow-up to Mr. Peanut (2010) and the wellreceived story collection Ladies and Gentlemen (2011) chronicles a season of upheaval in the life of a child actor on the cusp of adulthood. It offers a blast to the past in the vein of Garth Risk Hallberg’s City on Fire (2015) and the