SORTING OUT THE 2023 VENICE ARCHITECTURE BIENNALE

THE NATIONAL PAVILIONS

Prof. Johannes M. P. Knoops

THE NATIONAL PAVILIONS

Prof. Johannes M. P. Knoops

The 18th International Exposition of Architecture, or more commonly known at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale, is a global gathering of epic proportion. 63 National Pavilions, 18 practioners (a term coined by the curator to embrace those other than architects) in the Main Pavilion, and 38 practioners in the Arsenale form the core and foundation of this Biennale. And then on top of that, there are some site-specific works, several official collateral exhibitions, and many more unofficial installations spread throughout the city of Venice. All together they make for a dizzying assembly.

Curator Lesley Lokko titled this year’s Biennale, The Laboratory of the Future. To paraphrase Ms. Lokko, this is a biennale where decolonization and decarbonization are examined while placing the African continent at the center of where the future can be sorted out.

Not to single out this Biennale, but the Curator’s theme has always been left to interpretation and open-ended. I doubt there’s a heavy-handed dictatorial review of the National Pavilions’ proposals. Most pavilions, at least tangentially, connect with the curator’s mission statement, but there are always a few that seem to boggle me.

After letting it all sink in over a few days, I reviewed my notes and tried to sort this out. To make sense of things, I broke it down to identify threads that linked different pavilions… you can say I’ve prepared some parings in order to digest this all. Here are seven pairing for your consideration.

NORDIC: Girjegumpi

PERU: Walkers in Amazonia

NORDIC: Girjegumpi

PERU: Walkers in Amazonia

The Nordic Pavilion (representing Finland, Norway, and Sweden) hosts a project that started in 2018, titled Girjegumpi. The word is derived from two Northern Sámi words: Girji, meaning book, and Gumpi, a small mobile reindeer herder cabin on sledges, often pulled by a snowmobile. An archive of books focused on the architecture of indigenous peoples form the core of Girjegumpi. These were collected over the course of 15 years by Architect/artist Joar Nango. He is deeply committed to the Sami people, the last indigenous people of Europe. Originally a nomadic race, the Sami have inhabited northern Scandinavia for thousands of years. Nango’s library is a nomadic library. With each transient installation, he collaborates with other artists and crafts people as he draws us into seeing the sound building practices of indigenous peoples.

Peru created a highly immersive installation exploring the inherent insights of Amazonian communities including the Kichwa, Shawi and Awajún. The installation Walkers in Amazonia explores a certain phenomenon of regional walkers, those who traverse the rough Andean Amazon to observe, learn, share, and celebrate ancestorial knowledge, specifically biocultural insights. The installation acknowledges the shortcomings of modern progress in hopes of creating a new pattern language of mutual planetary nurturing.

GREAT BRITAIN: Dancing Before the Moon

CATALONIA: Ghost Stories: Carrier Bag Theory of Architecture

Though others have commented on the pavilion’s “clarity,” please don’t expect uniformity. Dancing Before the Moon, engaged six UK-based artists from a variety of diasporic communities to examine imported everyday rituals that have integrated into British life. The striking results are akin to the Biennale of Art. We are greeted by a travelogue touching on a variety of imported cultural practices. Then we become aware of a lyrical soundtrack permeating through the pavilion. Large-scale constructions fill the galleries, each with rich narratives, one referencing a Jamaican domino game, while another assemblage is coated in blue soap, Sabão Azul, a soap used at times to camouflage smuggled Angolan diamonds. The pavilion received a Special Mention from Gold Lion jury following Best National Participation.

Upon entering the defunct shipyard, visitors are met with suspended sheets that fill the space. Elegantly installed, these sheets evoke the sheets of Senegalese street vendors who use such sized blankets (or in Senegalese “mantas”) to layout and display their goods. Metaphorically, the installation becomes a street market of hot topics. Rather than displaying goods, these suspended pieces present a variety of issues from diaspora to equal rights. Working in conjunction with Top Manta (a movement of Senegalese street vendors), the project, Catalonia in Venice_ Following the Fish, rethinks various vacant store fronts throughout Barcelona to unite a community. By engaging architecture students from both Barcelona and abroad, the Reparation Atelier is an onsite laboratory to showcase options for these vacated spaces with collaborative programs such as welcome spaces, coworking spaces, and community kitchens.

Play spaces are social places where lessons are learned

SWISS: Neighbours

AUSTRIA: Partecipazione / Beteiligung

Curators Karin Sander and Philip Ursprung had a very simple vision for the Swiss Pavilion. Built in 1952 their pavilion was designed by Bruno Giacometti. Its design is noteworthy and located next to an even more compelling pavilion, the Venezuelan Pavilion, designed by Carlo Scarpa and built in 1954. In hopes of challenging issues of territoriality, they removed a portion of the pavilion’s wall bordering with the Venezuelan Pavilion to create a new threshold aligned with Venezuela’s existing entry. Beyond national boundaries, the installation Neighbours, puts into question all boundaries.

The Austrian collective AKT & Hermann Czech came up with a most provocative proposal, Partecipazione / Beteiligung. They sought to connect the Austrian Pavilion, which is located directly along a Biennale boundary wall, with the district of Sant’Elena by proposing a literal bridge. In hopes of subverting the veil of exclusivity they hoped to make the Biennale truly accessible to all. They went as far as submitting plans to the proper Venetian authorities only to get rejected. Unthwarted, they revised their plans only to be rejected again. In the end they built a portion of the proposed bridge within their pavilion’s boundaries to at least provide a visual connection.

MEXICO: Utopian Infrastructure: The Peasant Basketball Court

LITHUANIA: The Children’s Forest Pavilion

MEXICO: Utopian Infrastructure: The Peasant Basketball Court

LITHUANIA: The Children’s Forest Pavilion

Play spaces are social places where lessons are learned

Perhaps the most rambunctious of national pavilions, Mexico offered music, dancing and mezcal in their Utopian Infrastructure: The Peasant Basketball Court. Created at a scale of 1:1 we have a portion of a campesino, a basketball court common to indigenous communities. These are community social spaces of collective participation and clearly not just for basketball. Acknowledging its US-centric reference, the installation also speaks to a certain decolonization.

In a milieu of exhibits focused on adults, Lithuania created a delightful reprieve, The Children’s Forest Pavilion. This joyful play space posits children in a learning environment to explore the woods for its insights and potentials. Ultimately the intention is to entice them to take agency over their natural ecosystem. Made of timber grown in the Curonian Spit and transported to Venice, the installation has a very crafted vibe. While acknowledging a child’s unique views, educational findings are presented on the values of outdoor play, where forests are seen as negotiated spaces for collaborative lessons.

SAUDI: IRTH, BELGIUM: In Vivo

SAUDI: IRTH, BELGIUM: In Vivo

Material choices are both narrative and moral choices

Constructed primarily of 3D printed clay tiles, the designers created an inverted landscape for us to explore. Earth is celebrated as an historical precedent in Saudi architecture and also its future. The visitor is further seduced by an aroma of lavender, frankincense, and myrrh, to further our visceral response. Titled IRTH, we are each invited to add additional tiles to this magical forest as they are produced on site.

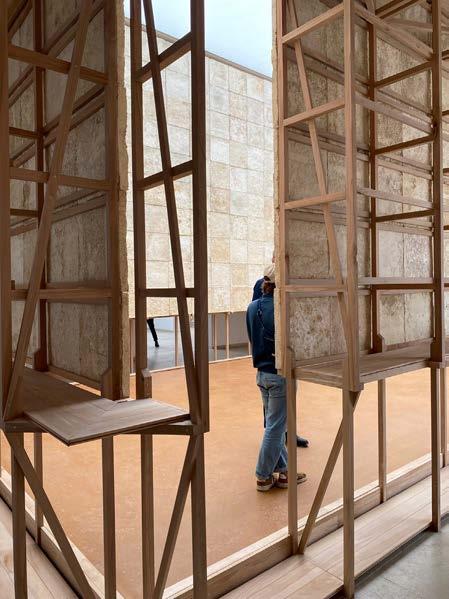

Rather than thinking of materials in terms of a resource to be extracted, in a world of limited resources Belgium asks us to re-think that model. Instead, they advocate the use of living organisms in the production of architectural materials. The In Vivo pavilion is a beautifully crafted pavilion within a pavilion. Measuring 12 x 6 x 6 meters we are confronted with an impressively detailed wooden framework that fills the central gallery. Once inside we delight in panels made of common dirt and mycelium (the vegetative portion of fungi). These organic panels sheath the entirety of its interior, to make what I consider this year’s most architectural installation, a space with a contemplative aura. Despite the installation’s repetitive manner, we delight in the uniqueness of each unit. The dirt, wood and mycelium were all sourced in Belgium.

AUSTRALIA: Unsettling Queenstown

BRAZIL: Terra

AUSTRALIA: Unsettling Queenstown

BRAZIL: Terra

This highly layered installation, Unsettling Queenstown, examines both the displacement of its first settlers from their mother country and the ultimate displacement of its indigenous people and extraction of resources. The very name Queenstown espouses colonization. The installation is defined by a wireframe representing a wellknown piece of colonial architecture, but behind that lies a bigger story. By demapping the current landscape, the original aboriginal names of locations are reveled and in so doing the curators are inviting us to learn the narratives of its indigenous people.

Though history tells us Brasília was placed in the geographic center of the country, this installation, Terra, makes evident that the Oscar Niemeyer designed capital was not located in a generic uninhabited tropical forest. Instead the constructon of Brasília required the forcible displacement of Indigenous and Quilombola communities. To express the ancestry and future of Brazil, raw earth covers the pavilion’s floor from wall to wall, while a variety of rammed earth plinths showcase the valuable lessons these people have to offer. This year’s jury of the Gold Lion awards named it Best National Participation.

TURKEY: Ghost Stories: Carrier Bag Theory of Architecture

FINLAND: Huussi

TURKEY: Ghost Stories: Carrier Bag Theory of Architecture

FINLAND: Huussi

Ghost Stories: Carrier Bag Theory of Architecture, encourages us to listen and understand the stories of abandoned buildings. Based on an essay by Ursula Le Guin, the Carrier Bag is a proposition that man’s first tool had been a bag, not a weapon. The installation relied on open submissions to compile hundreds of unoccupied buildings. Surprisingly this happens to be an unproportionally large number in this country when compared to other countries. Turkey’s installation is a moral plea to consider options of reuse and repurpose by both traditional and innovative means.

Did you realize that 30% of all domestic water consumption is used to flush our personal waste down toilets? And that this wastewater is a large source of environmental damage? Titled Huussi, a Finnish word for outhouses with compost toilets, this installation advocates vernacular solutions. Though what was on display was quite contemporary and a fine example of good Finnish design. This particular model relies on wood chips sprinkled over each use and then the wood chips are to be later collected for nurturing soil. Though this is one option, at the same time the installation advocated the necessity to re-think entire waste systems at an urban scale. I found this to be one of the clearest messages. In my interview with Haziq Ariffrin, a member of the team, the upbeat enthusiasm for their mission was joyously contagious. Who knew that talking about poo would be such fun.

Motivated by issues of memory and place, Johannes Knoops explores hidden urban narratives. As a Professor of Interior Design at FIT/ SUNY, he shares his passion for a design to communicate narratives. In addition to his teaching, Knoops maintains a multi-disciplinary studio on Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

jmpknoops@mac.com www.knoops.us

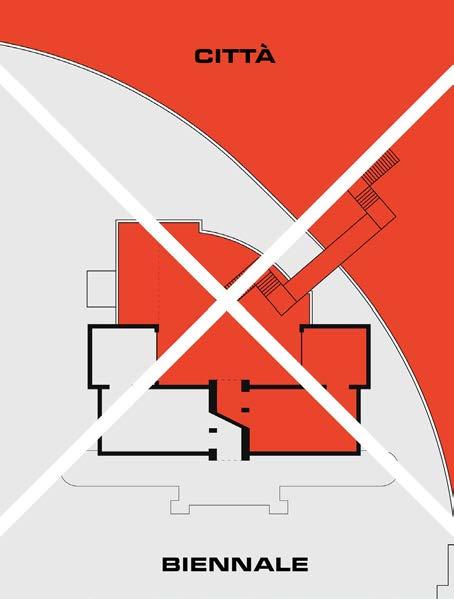

The Central Pavilion at the Biennale Giardini

Photo by Steven Varni

The Central Pavilion at the Biennale Giardini

Photo by Steven Varni