Our thanks go out to all fans of modular architecture, who believe in its future.

Authors’ team: Jiří Kout

Martin HartJaroslav Sládeček

Kateřina Frejlachová

Matěj Beránek

Our thanks go out to all fans of modular architecture, who believe in its future.

Authors’ team: Jiří Kout

Martin HartJaroslav Sládeček

Kateřina Frejlachová

Matěj Beránek

With the assistance of KOMA MODULAR s. r. o., in cooperation with art Echo s. r. o..

Number of pages 152. Second edition.

Authors’ team: Jiří Kout, Martin Hart, Jaroslav Sládeček, Kateřina Frejlachová, Matěj Beránek

Graphic design, typesetting: Alexandr Hudeček

Editor: Jiří Kout

Contact: www.artecho.cz

Translated by:

EUFRAT Translating and Interpreting Centre in Pilsen (Zdeněk Benedikt)

Language editing by Simon O’Flynn

Cover photo:

Julius Filip, Development and Innovative Centre of Modularity

Czech Republic

No part of this publication may be copied or reproduced with the intent to distribute it in any form without the written permission of the publisher.

© 2012 KOMA MODULAR s. r. o.

All rights reserved.

Printed by: První dobrá, s. r. o.

Address: Hajní 1354,198 00 Praha 9 – Kyje

Design showroom in Lüneburg, Germany

© Jiří Hroník

Design showroom in Lüneburg, Germany

© Jiří Hroník

Dear readers,

The goal of this book is simply to please both fans of modular architecture and construction as well as readers with no prior experience with modularity but who are interested in learning about it. I Love Module was published in cooperation with the Department of Architecture of the Czech Technical University in Prague. The publication was made possible by KOMA MODULAR, one of the first companies in the Czech Republic to manufacture living containers. Over the years, the company has become the leader in the area of modular construction, while at the same time devoting energy to the popularization of modular architecture. The first edition of I Love Module was published on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the establishment of this company.

In this book we hope to uncover the reasons behind the birth of modular building and its ongoing spread, which over time has grown into the phenomenon called “modular architecture”. We will reveal the desires as well as the needs of people who want to live, work or study in a container. We will show you the material variety of modular buildings evoking the feeling of the future, as well as inducing the notion of a patina of world travel. We will also introduce buildings which you would never think are made of modules, just as you often can’t tell whether a building is made of bricks, concrete or wood. You will get acquainted with the unique properties of modular construction, which is often not only attractive, unique, exciting and unexpected, but also simply practical and convenient. We will touch on the milestones that represented significant changes in modular construction. We will guide you through the attractive world of modular architecture from its beginnings until the present time.

Dear readers, let us wish you pleasant and inspirational reading. Welcome to the Modular Age!

Authors’ team

“Don’t fight forces, use them.“

(R. Buckminster Fuller)

If you told someone in the Czech Republic or Slovakia that you lived in a container, they would probably be a little concerned. However, in the United States, Germany, Britain, Japan and the Netherlands, people longing for originality, modernity, experience and surprise will know exactly what it is about. Why is that and how did it start?

Modular architecture is based on three basic principles that follow from people’s needs – prefabrication, mobility and variability. If we want to get to the actual source and grassroots of the birth of modular architecture, we need to follow these historical needs.

The first documented example of a prefabricated construction dates back to 1624, when the British brought to the town of Cape Ann in Massachusetts a wooden panel building, which was to serve as a dock for their fleet of fishing boats. It had been prefabricated, shipped in pieces and assembled at its destination. During its lifetime, it was repeatedly taken apart and transported to other places as the fleet moved. Although the dockyard was not created in the process of space modulation, we can still consider it, thanks to its prefabrication and mobility characteristics, the original modular construction. This early example represents the first two of many unique characteristics of modular buildings – ease of disassembly and fast to transport. When there was a need for something more lasting and durable than a tent, the brilliant idea of creating a prefabricated modular building was born.

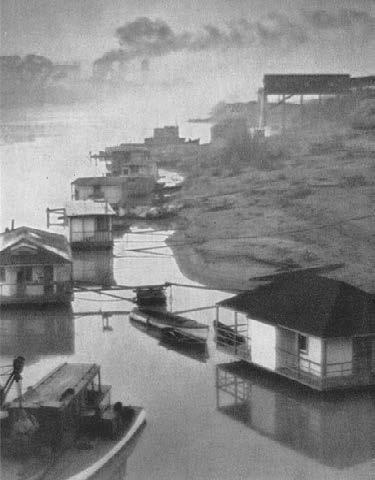

Overseas in the early 20th century, we see another example of a prefabricated construction, which was intended to be used as a temporary residence and which displayed another typical quality of later modular buildings – its own mobility. In this respect, it is in fact a successor of the mobile dockyard from the 17th century; however, it is not built for the purpose of being disassembled, but moved as a whole. We are talking about the still popular, originally wooden houseboats. Although the term houseboat might indicate that these are mainly floating homes meant to be lived in, they have also been used for business purposes – as mobile shops.

Currently, houseboats are intended mainly for long-term stays in one place rather than frequent travel. However, these floating houses often have their own motor and can be used to travel along many waterways. Self-propelled houseboats are nowadays very popular all over the world. In Europe, it is especially in Germany, the Netherlands, France and Great Britain where we can also find large floating modular buildings. These are houseboats without a motor that can be used for accommodation or other purposes, e.g. as galleries, shops or offices.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the territory that today makes up the Czech Republic saw the frequent use of other mobile homes intended for living. These were the famous trailer homes called maringotka, whose name spread mainly thanks to writer Eduard Bass and his books about life in a circus. These prefabricated wooden houses on wheels can be considered the predecessor of prefabricated mobile constructions in the territory of the then Austria-Hungary.

This photograph from 1922 depicts floating houses in Los Angeles. Houseboats are usually not self-propelled and any change in location requires the use of a towboat. In California, houseboat owners wanted to avoid paying property tax. However, the government introduced the so-called shadow tax, which was determined by the size of the shadow cast by the floating boat upon the sea bottom.

Trailer homes were a typical symbol of nomadic groups, who on their way to making a living preferred a life full of changes and freedom to having a stable home. On the one hand, such a lifestyle is free, but on the other it is full of uncertainty and requires a great deal of courage.

Trailer homes began to spread mainly before WWI, when it was no problem to travel around almost all of Europe. As early as in the 1880s, these trailers replaced the old wagons in which travelling artists used to transport their belongings. Their advantage of relatively comfortable mobile living was also utilized outside the circus by the Romanies, whose nomadic way of life was gradually suppressed by the Austro-Hungarian authorities. The definitive end to the Romanies’ migratory lifestyle came thanks to the totalitarian regimes in communist Europe (preceded by massacres of the Romany population during WWII), and the gypsy trailers gradually disappeared.

Trailer homes were popular in Czechoslovakia throughout almost the entire 20th century, although successful circuses gradually replaced them, following the US example, with caravans that first appeared in the United States right after WWII. However, trailer homes’ main characteristic, mobility, ensured their popularity for the rest of the 20th century, when they were often used as mobile facilities.

The first representative of prefabricated homes designed for permanent living without the intention of frequently moving were catalogue component wooden houses from the American company Sears Roebuck & Co., established in 1908. These were so-called “kit homes”, whose individual parts had been manufactured in a factory, and using an instruction

manual, the owners assembled the houses themselves. The manual was 75 pages long and the house consisted of more than thirty thousand parts. In the early 20th century, Sears Roebuck & Co. thus offered people the chance to purchase a relatively inexpensive house which everyone could quite easily build themselves. It kind of makes us wonder whether that famous Swedish home products company specializing in the sale of ready-to-assemble furniture found inspiration in the above-mentioned American company from the beginning of the 20th century.

In Europe, we may see the origins of variable prefabricated buildings intended for long-term use in the “Dom-Ino” project (Domus-Innovatio). It was the brainchild of one of the greatest architects of the 20th century – Charles-Édouard Jeanneret a.k.a. Le Corbusier. He was originally a self-made man who had not studied architecture, but learned about this field by traveling around Europe in 1907 – 1914. At the time he designed a simple skeletal framework which residents could complete themselves with non-load bearing partitions. This project has its place in the history of modular architecture particularly because of the prefabrication of the supporting structure and the variability in the creation of the interior. An interesting link between “Dom-Ino” and its historical predecessors and contemporary modular construction is the dimension of humanitarianism, as the “Dom-Ino” project was intended for the war-stricken areas of the Flanders during WWI.

Sears Kit House –model 115, 1908–1914

A drawing of a Sears kit house from a catalogue, based on which customers decided which house was most suitable for them, given their needs and financial possibilities.

Sears Kit House

A catalogue house from the American company Sears, built in 1925 in Greensburg, PA. This typical example of a kit house can be found at 133 Grant Street. Kit houses have remained popular in the United States to this day..

“My only education is the constant observation of nature and the things around us.“ (Le Corbusier)

kiosk Slinge

© Scagliola Brakkee

execution by Bijvoet architectuur & stadsontwerp

kiosk Slinge

© Scagliola Brakkee

execution by Bijvoet architectuur & stadsontwerp

The first primitive cranes were used in ancient Egypt for the construction of pyramids. In ancient Greece and Rome, heavy blocks of rock were also lifted using crane mechanisms in the construction of fortresses and temples.

Thanks to the hoisting tackle, a combined pulley invented in the Renaissance, height was no longer an issue for cranes. Another milestone was the invention of the steam engine in 1756, from when cranes were no longer propelled by human or animal force. This foreshadowed the construction of very tall and demanding buildings. German Hans Liebherr had the first mobile tower crane patented in 1949.

In the 1970s, the current construction crane came into existence, enabling the transportation of products and building materials of up to 100 tons. This gave rise to a modular boom, as it was possible to handle larger modules, the assembly time was significantly reduced, and the only limitation was the load’s size for transportation.

“It is true that leaving the old brings uncertainty – a leap into the dark. However, if a person wants to help himself and others, he has to leave the good to fight for the better.“

The famous Czech entrepreneur Tomáš Baťa and his in-house architect, František Lydie Gahura, rightfully belong among the pioneers of Czech modular architecture, as they were the first to use a modular system to streamline the construction process, thanks to which they were ahead of the times. They first used the modular system in 1928 in the construction of so-called Masaryk schools, which consisted of units of fixed dimensions 6.15 m x 6.15 m, which later became the basic construction element of all of Baťa’s buildings in our country as well as abroad, where the company expanded. The transition from manual to mechanical production was also reflected in the need for faster construction of new factory buildings and the standardized modular system enabled both faster construction and greater functional flexibility. The advantage of modular construction was also used in the construction of partitions, both full and glass ones.

In the same manner, architect Vladimír Karfík designed the famous administration building No. 21, better known as Baťa’s skyscraper. With a height of 77 meters, it was then the second tallest building in Europe, and among other things contained Baťa’s famed office in an elevator sized 6 x 6 meters. Standardization and typization was also reflected in the construction of residential houses, which were not built in the form

Baťa’s skyscraper

Building No. 21 on the premises of the Zlín factories, founded by one of the greatest Czech managers, Tomáš Baťa. Baťa adopted the American system of numbering buildings –the first digit refers to the building’s position from east to west, the second its location from south to north. It was at the time the tallest building in the country and the second tallest in Europe. Each floor had an independent air-conditioning system, and there was a flower garden with a fountain on the top floor. The building was reconstructed in 2004.

(Tomáš Baťa)

of high-rises, but rather duplexes and fourplexes, according to Baťa’s vision, which was inspired by the English concept of garden towns. Great urbanistic plans and further development of the city of Zlín were terminated by WWII and subsequently the company’s nationalization in 1945. This urbanistic complex has remained a unique gem, which in 1990 was declared an Urban Heritage Site.

A historical photo of one of many types of Dymaxion houses. This particular one was built by the Butler brothers, using parts of a grain silo in 1941 in Kansas City, as per Buckminster Fuller’s design.

One of the most famous projects and the first real breakthrough at the time of the building industry’s effort to cope with the age of mechanical production (nowadays such a characteristic quality of modular buildings), was the “Dymaxion Deployment Unit” (DDU), designed by Richard Buckminster Fuller, an American architect and engineer. Because of the attempt to apply serial production in the building industry, these houses are considered predecessors of prefabricated modules, although DDUs are not entirely modular as they require a great deal of work on the construction site and are not variable.

“If the original is sulky, its reproduction is even sulkier; however, if the original is highly suitable for its intended purpose, its reproductions become even more graceful in confirming this suitability.“

Despite that, the cylindrical houses made of steel and corrugated iron, which were created in the USA in 1940, provided temporary shelter during an evacuation; they were used as mobile barracks and bomb shelters. The interesting thing about these houses, which provided accommodation for 24 persons, is the fact that although they were supposed to meet a strictly practical human need, which reflected the social situation of the wartime period, we also see an attempt at achieving an esthetic value in them.

Its provisional character, the possibility of easy transportation and the use of metal evoke a kinship between DDUs and today’s residential containers. It also amplifies Fuller’s statement that he tried to create houses with maximum effectiveness per kilogram of building material. That unequivocally confirms that the DDU is the original modular architecture. In other words, Fuller’s statement may be interpreted in such a way that his goal was to find such a material whose functionality and quality would offer equivalent properties as another, more expensive one. Already in the early 1940s, Fuller admitted in Dymaxions the natural character of metal, its raw genuineness.

From the octagonal design of the Dymaxion house of 1929, Buckminster Fuller managed to gradually develop his idea of a prefabricated aluminum house into the model known as Wichita, named after the town in the state of Kansas, where it was to be mass produced at the local plane factory. Seeing the first prototype, the factory owner abandoned the plan, saying that customers were not ready for such a “mechanical” type of house, and that there would not be any demand for such homes.

(Buckminster Fuller).

The unconcealed natural character of material is also found in other prefabricated houses that came after the Dymaxions, right after the end of WWII. Because of his expertise in the area of lightweight ready-to-assemble homes, Fuller, a pioneer of the factory production of homes, was hired to create the famous Wichita House, which weighed only 4 tons. This was made possible thanks to the technology of processing light metals and alloys from the mass production of war planes, which reduced their cost. Fuller planned the production of his for many people futuristic Wichita house on the bomber plane production lines at the Beech Aircraft Factory in Wichita, Kansas. Despite the much more comfortable interior and the attractive design of the Wichita house, its production was terminated in 1947 with the explanation that replicable houses of the Wichita or Dymaxion types were a utopian idea.

Fuller did not manage to launch the manufacturing of serial-produced houses, thus failing his own vision to produce 60,000 units per year. Despite that, the Wichita prototype is the most important prefabricated house construction of the 20th century, and it is surely the biggest wasted opportunity in the post-war residential recovery.

We see the immediate need for the utilization of idle factories after the war and the explicit use of metals also in caravans, including the legendary Manor camper trailers from the Spartan Aircraft Company, which came into existence at the same time as the Wichita House (their production was launched in 1946), and whose mobility followed

Caravan

A camper trailer from the Airstream Company. The aerodynamic shape and low weight of the aluminum shell are a guarantee of good gas mileage when being towed.

Design studio

© Saab AB archive

Design studio

© Saab AB archive

The introduction of computer technology has changed just about any area of human activity that we can think of. Similarly, the use of computers has changed the production of modular systems.

The first accessible computers revealed a potential which very few had imagined. The turning point in architecture was the possibility of creating a design on the computer instead of the drawing board. Throughout the 1990s, thanks to email and the Internet,

computers also significantly entered the sphere of communication.

3D

The greatest software milestone in the development of modules was the use of programs that allowed designers to work in 3D and thus improve and speed up the process of preparing production documentation. These software applications can communicate with production machinery (e.g. CNC machines – computer numerical controlled), which results in a more efficient and accurate production process.

“It had a fitted fridge a kitchen table that folded into the wall and a bathroom. Family and friends came visiting to view the wonders. It seemed like living in a spaceship.“

(Neil Kinnock, owner of an AIROH house and future leader of the Labour Party of Great Britain))

that of houseboats and maringotka trailers. These mobile homes on wheels established themselves relatively easily on the post-war affordable housing market, and they have remained popular to this day.

At the time of their creation, they capitalized on the same advantages and needs of post-war factories as did Fuller’s projects. Caravans are noticeably closer to the current understanding of modularity – they are serially produced prefabricated dwellings on wheels, which in post-WWII America were much less futuristic than the Wichita House, and thus better accepted by society.

After WWII, Great Britain, which had the same needs as its ally, the USA, became the cradle of European modular architecture. The British had to resolve the issue of how to use wartime production lines, as well as providing accommodation for returning soldiers. The British government had promised them their own houses, so plane and car factories started to experiment with prefabricated homes, the most successful of which was the fully modular AIROH house. By 1948, the line that used to produce bomber planes had churned out 54 thousand of them. However, the real reason behind the success of AIROHs was the immediate need to have a “roof over your head”. The majority of those who lived in AIROH homes wanted to move to a conventional house at the earliest opportunity. Their shape and appearance directly relates to current residential containers, which makes them the beginning of European modular architecture as we know it today.

In the early 1950s, as a certain variation on caravans and houseboats, so-called “Mobile houses” appeared in the United States. These wooden houses are produced to this day not only in the USA, but all over the world. These homes were first in demand by people whose lifestyle required mobility. During the 1950s, they became a cheaper alternative for people who could not afford a conventional house. Their basic advantages are mainly mobility and the possibility to “build” the house without a building permit. Mobile houses are not permanent constructions. They are built on a chassis, which allows for their relatively easy transport. While caravans are mostly intended for temporary or holiday stays, mobile houses are larger, better equipped

and are usually transported only once to a set site, where they remain permanently. However, they retain the possibility of being transported, if their owner or other circumstances demand it. After being anchored, the chassis is covered by sheet metal cladding. When entering or leaving the house, there is the disadvantage of having to climb stairs whose height corresponds with the clearance of the chassis.

AIROH (Aircraft Industries Research Organization on Housing) was founded in 1946 in the war-stricken Britain as a part of a public housing reconstruction programme. Its serial-produced houses comprised two bedrooms, a lounge, a hall, and a kitchen with cold and hot water fitted with a fridge and a gas or electric cooker. There also was a bathroom with a heated towel rack in the house.

These serial-produced mobile homes are awaiting their new owners, who upon purchasing them can immediately have them transported to their property.

“Our new house cost about $83,000. I remember the rainy afternoon when they brought it to us. We had it custom made. We chose a thicker insulation and a protective cover so that it would be better protected during transport. We got an extra pack of tiles and two buckets of interior and exterior paint. We like our house and our friends often tell us that it does not look like it had been made in a factory.“

(Liberty House owner from California)

At the turn of the 1960s and 70s, increasingly wider and longer variations of mobile houses were built, which impacted their mobility. Nowadays, such houses usually become permanent structures. In some states, the tax paid on such a house depends on whether it stands on its own wheels. If so, it is considered personal property. If not, it is taxed as real estate. Although mobile houses are intended for permanent living, they are not constructed according to building standards, but rather to those applicable in the construction of trailers and caravans. Especially in the United States, mobile houses are often used for recreation. In Great Britain, these stationary caravans can be found on farms, where they provide accommodation for fruit pickers, and also in recreational areas. In Israel in the 21st century, ready-to-assemble houses have been used for residents in the Gaza Strip. Jewish settlements had been dissolved as a concession to Palestinian autonomy and the international community. These temporary houses were then provided as accommodation for people without a home.

Liberty Homes, one of the oldest manufacturers of modular houses, was founded in the USA in 1941. To this day, it specializes in prefabricated wooden homes – their design, production and sale across the entire United States. It is undoubtedly the first modular building in the history of modular architecture.

In 1958, the house met all the conditions to be called modular. Firstly, it was set upon proper foundations. It was thus clear that it had been built for permanent purposes. It was built in line with building standards, built by prefabrication, and transported to its location. The option of being able to add any number of modules enabled great variability without significantly increasing its construction time. At the same time, it did not lose its mobility, as it could be taken apart as easily as it was assembled and transported to another place. That is why we can consider the year 1958 the true beginning of modular architecture.

Modular homes with a wooden construction are still popular mainly in North America. Although prefabricated, they offer a wide range of layout variations (e.g. 2–5 bedrooms or other optional spaces such as a conservatory, workshop, porch, etc.) and even matching walls, carpets and interior decorations. A Liberty Home is in many respects similar to a mobile house, only without the chassis.

The history of ISO containers dates back to 1956 when an American truck driver, Malcolm McLean, thought of a way to save a lot of human labor in the transfer of goods from trucks onto ships. The idea was to load the entire trailer (only without the chassis), which skipped an unnecessary step in the transportation chain and at the same time remarkably increased transport safety by avoiding damage during the handling of consignments and hiding the contents from the sight of people, thus reducing the theft rate. McLean had his invention patented – a metal shipping container with reinforced edges, which allowed their handling by crane during reloading as well as the stacking of several layers, one on top of another. A shipping container has excellent static resistant properties, so it is no wonder that it soon became used in the building industry. It is true that according to some sources, steel containers had already been used in the Korean War in 1950–1953, but thanks to his patent, McLean is the first recorded, and thus provable, inventor of the shipping container as we know it today.

For modular architecture, the shipping container is undoubtedly a major milestone, as especially in Europe modules are currently produced in a similar way, using reinforced edges. That is why the year

Durability and stability are two of the most important reasons why the shipping container is also used in architecture. By easy modification – adding insulation and fitting its openings – it is possible to turn a shipping container into a functional modular unit. Especially in Europe, prefabricated modules are produced as construction units, using virtually an identical system of a steel frame with reinforced edges and paneling.

Bayside Marina Hotel © Yasutaka Yoshimura Architects

Bayside Marina Hotel © Yasutaka Yoshimura Architects

Since the Middle Ages, logistics has represented a series of activities whose task it is to ensure that goods are delivered to a specific place at the required time, quantity, quality and at adequate costs.

Just in time, or in other words the delivery of materials and parts exactly at the time they are needed in the production process. Also finished modules are brought to their designated site and assembled at exactly the required time, whether by road, water, air, railway or by means of combined transport.

The production of modules is efficient only if the internal logistics is efficient. Based on the nature of commodities, material storage facilities are usually divided into cold storage facilities (for materials whose quality is not degraded as a result of temperature changes), air-conditioned storage facilities (for materials requiring a constant temperature prior to processing), and warehouses for finished products – individual modules prior to being dispatched.

“We were objects of pop art, and the fashion and sexual revolution, to say nothing of the publishing boom. All this has suddenly opened up. However, the biggest discoveries came in the 1950s (…) The following decade only made it all the more popular. London was again in the spotlight of world architecture.” (Peter

Cook)1956 is a breaking point in the development of modular architecture, as without the shipping container, current European modular architecture would hardly be the same.

A very interesting milestone in the development of modularity and prefabricated buildings from new and innovative materials was the establishment of the Archigram group of avant-garde architects in London in 1960. Archigram strived to create a concept of new ‘high-tech’ architecture based on scientific discoveries and technical achievements. The group thus looked for ways to satisfy people’s needs at the time with technical development. Since the beginning, its membership base (made up of Warren Chalk, Ron Herron, Dennis Crompton, Peter Cook, David Green and Michael Webb, with the collaborating designer Theo Crosby) created very technicist projects reminiscent of large machines – refineries. The group’s visionary displays were influenced by the architect Louis Isadore Kahn, but also industrial production, science-fiction literature, and the development of astronautics. Their graphic expression was clearly influenced by the comics culture.

Members of Archigram dealt not only with individual buildings, but also designed futuristic urban solutions, the most famous of which was the Plug-in City or the so-called “Walking City”. The creator of one “Walking City” is the famous Peter Cook, who presented the vision of an assembled and cybernetically controlled Plug-in City in 1964 (two years after a similar idea by Isozaki from Japan). The city, comprised of steel modules of buildings and roads, gradually spreads like a continuous strip, like a highway. Using permanent cranes, residential cells are inserted and moved within the weight-bearing framework. Architecture thus becomes a consumer good, which undergoes constant self-recovery (just as cars get replaced) – it gets metabolically restored as a living organism.

The fantastic works of the Archigram group had a great influence on the further development of architecture and its technicist concept is a direct reference to modular architecture.

Habitat 67 is a model community and housing complex built next to the Saint Lawrence River in Montreal, Canada. Comprised of 354 prefabricated units – reinforced concrete modules, it was the dominant feature at the EXPO 67 World Fair. Its creator is an Israeli-Canadian-American architect, Moshe Safdie, for whom Habitat was the start of a stellar career. Safdie was born in 1938 in Haifa, which is now Israel; however, he and his family moved to Montreal, Canada, for which he designed Habitat – an extraordinary housing complex consisting of 158 one- to three-bedroom apartments with numerous small terraces and gardens.

Habitat 67 was designed as the prototype of a modular system which was to streamline the building process and thus reduce costs. The ingeniously assembled modules show the variability and playfulness of modular architecture, but due to the materials used, they do not achieve the speed of construction or the financial efficiency of today’s modules. For this reason, the prototype was never applied on a mass scale. Despite that, the project is a milestone in the history of modular architecture, as it offered a real, though until-then only visionary, solution to community housing.

This housing complex, designed by the Israeli architect Moshe Safdie on the occasion of the World Fair in Montreal, Canada, became an icon of the city and one of the symbols of architects’ efforts to support social integration.

Richard Rogers‘s early work contained revolutionary ideas. Wimbledon House was originally designed for the architect‘s parents in the 1960s. The architect‘s family lived there until 2013. In 2015, the house was donated to Harvard University to be used for research and for teaching architecture. Between 2015 and 2017, this unique and listed building was caringly restored.

Another great name in the history of modular architecture is Richard Rogers. This world-famous British architect was born in Florence in 1933, from where he and his parents emigrated to Great Britain in 1939. In 1968, Rogers and his team (Su Rogers, John Young and Laurie Abbot) designed a breakthrough modular project – a prefabricated house called “Zip-Up”. The house is still part of an exhibition of prefabricated houses at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and even after 40 years its design is still appealing and current. Rogers followed the idea of prefabrication and structural simplicity with the aim of designing a house for his parents in Wimbledon. He finally succeeded and created the still inhabited “Wimbledon House”, whose concept directly influences the best modular buildings of today. Richard Rogers’ son and his family now live in the house.

In the former Czechoslovakia, we can see a follow-up to modularity in the form of the not very attractive, but practical Unimo cells, which were used, for example, as facilities for workers during the construction of the Prague underground system in the 1970s, and which,

because of their shape, clearly remind us of current residential modules. However, poor insulation properties and the excessive use of hazardous materials (formaldehyde), and in the end also innovations in modular production which came to post-revolutionary Czechoslovakia from Western Europe, led to a transition from Unimo cells to living containers. To this day, the need for temporary housing is one of the basic characteristic features of modular construction.

In the Czechoslovakia of the 1970s, we also see other attempts at prefabricated construction. In Zlín (formerly Gottwaldov), the landscape engineering company Pozemní stavby Gottwaldov produced modules with a concrete shell. These freely followed up on the Habitat project; however, in competition with the construction of panel apartment buildings (in the form that we can still see today in many Czech as well as Slovak suburbs), concrete modules, which were more costly, did not stand a chance of being used on a larger scale. Following a few minor construction projects, their development was soon terminated.

A futuristic-looking and, at the time of its construction, an incredibly visionary architectural work which stirred up deeply rooted conventions in the area of residential buildings, was erected in the Japanese metropolis – Tokyo. It was in 1972, at a time of wild developments in technology, design and fashion, when just about everyone longed for novelties and let themselves be carried away by a tireless current of enthusiasm and endless invention. At world fairs, buildings and products of unprecedented shapes and colors were exhibited, which provided inspiration for the daring idea to create a building made of socalled capsules – units that will be unified and attached to one stem, as in a bunch of grapes, which will provide them with power and water. That is how the residential and administrative building Nakagin Capsule Tower by architect Kisho Kurokawa was created, making an indelible mark in the history of architecture. It was the first ever execution using this capsule system.

Architect Kurokawa was part of a movement known as Metabolism, which came into existence in Japan in 1960. Its members included other prominent Japanese architects such as Kenzo Tange and Arata

“Architecture is like a theater stage, with people playing the lead roles. The whole art of design is about being able to direct the dialogue between these people and the space that surrounds them.“

(Kisho Kurokawa)

Can you still remember those exciting moments when you or your children played with LEGO or similar building blocks? One block – one component – one module – one house, two blocks, three blocks, space… modular architecture.

There are countless spatial combinations and possibilities when using modular units. The only rule of the game is the system. Combine in your home rectangular blocks and cubes of different sizes and color. Choose either a wooden, brick or aluminum facade. Decide where there will be small windows, or windows along the entire wall, and how to arrange the modules… That is your architecture – your game.

The possibility of being able to easily dismantle the construction enables constant development. Modular buildings are never final and definite; they are buildings that change over time as they adapt to our current needs. A modular house is alive.

This rare example of capsule architecture was built in Tokyo in 1972, following a design by Kisho Kurokawa. It is part of the Japanese Metabolism movement.

Isozaki. In the 1970s, they were behind a number of unique buildings such as the pavilion at the Osaka World Expo in 1970 and the SONY building in Osaka from 1976.

Arata Isozaki, Kenzo Tange’s student, created among other things the utopian vision of “Space City” from 1962, in which individual residential modules would be placed on horizontal beams suspended on tall

pillars. Using helicopters, these could be easily replaced with new and improved modules. This structure above the city would gradually replace the original city on the ground.

The story of the birth and development of world modular architecture ends here. However, that does not mean that it is the end of their history. On the contrary, everything is just beginning. As we could see, the driving force behind the birth of modular architecture has always been a desire for something new, better, more comfortable and accessible. Since its beginnings, modular architecture has symbolized a longing for modern life, freedom, the need for immediate housing, the effort to achieve greater efficiency of the building process, and easier transportation of the “building material” to the construction site.

Modular architecture is a never-ending fight for better living conditions, accessible to the widest range of people who are not afraid of the unknown, are curious and have the desire to discover the constantly developing type of architecture called “modular”.

“A successful business transforms before it has to.“

(Jonas Ridderstrale)

The history of modular architecture also started to unravel in the Czechoslovak federation, be it in the form of historical or modern maringotka trailers, unimo cells or reinforced concrete prefabricates from Zlín. However, the real onset of modular construction came after November 17, 1989.

The first major milestone in the development of contemporary modular construction in the Czech Republic was the Velvet Revolution in 1989 and the subsequent disintegration of the Slušovice co-operative farm in 1990. The Slušovice co-op was phenomenal and managed virtually the impossible during the totalitarian regime – to become a prosperous and developing company. The system of management and the company’s rules resembled those of the most “capitalist” companies and another Czechoslovak phenomenon – Baťa.

Slušovice cared about the quality of its staff and their work ethics. Everyone could be either promoted or transferred to a lower position from one day to the next. People talked about their work with enthusiasm at the pub, which was unheard of during the communist totalitarian regime. This unique work environment enabled the recruitment of managers from among people behind the iron curtain even before the revolution, who managed to capitalize on the acquired experience following the fall of communism and the decline of the Slušovice Co-Op.

A number of new businesses were established in the Zlín Region, and after some time living containers of the Western European style started to be produced on the former Slušovice premises. Thanks to the disintegration of Slušovice, there are now a lot of successful companies operating in the Zlín Region. One of the most innovative in the region is KOMA MODULAR, which has over the years become the Czech leader in the production of modules. It was the first company to start producing containers from galvanized sheet metal, and it invented a low-energy comfort module. But first things first…

One of the new generation of Slušovice managers was Stanislav Martinec, the current owner and director of the KOMA Company, who was sent to head one of Slušovice’s companies in Vizovice by the Co-Op’s management. At the time, maringotka trailers were produced at the Vizovice plant, and director Martinec was put in charge of this rather problematic operation. Production had stopped, and the new trailers, which did not sell very well, were scattered around the plant’s premises, yet no one seemed to be concerned about this state of affairs.

Martinec, who was used to certain work efficiency, was forced to lay off most of the employees.

Subsequently, during the following several months, the post-November situation dramatically developed. In the end, it was clear that there was no way to stop the disintegration of Slušovice. This was probably the result of the fact that the Slušovice Co-Op was seen as a model example of the totalitarian regime. Despite differing views of Slušovice, in the historical context it is clear that given the atmosphere in society at the time, the disintegration of Slušovice was inevitable.

The then director of the Vizovice plant had to respond to the new situation. He put together a group of several dozen people and established a new company – Mobimont, which abandoned the production of mobile trailers and started to produce living modules called Mobires. Neither this led to long-term stabilization, though. The unclear group of those who laid claims to the property, where the production plant was located, lots of people who did not understand the workings of a “capitalist” company, management without clear competencies – all this foreshadowed the end of Mobimont within several months. Despite its failure, it is clear that it was Mobimont that planted the first seeds of modularity in what is today the Czech Republic.

Period promotional material from the Mobimont Company and its Mobires modular recreational system..

KOMA MODULAR

In early 1991, Mobimont was succeeded by the ACRO Company, which immediately switched from the production of Mobires to standard living containers, which were being produced on a large scale in Western Europe. This came about because ACRO had a much clearer management structure than its predecessor, Mobimont. ACRO was owned by Stanislav Martinec, who had come from Mobimont, and a German partner, who thanks to his business contacts in Western Europe helped launch production of the well-known standard living containers. However, the differing opinions of the two partners on the company’s development, its sales strategy and goals resulted in the company existing only briefly, roughly as long as Mobimont.

The end of ACRO did not mean the end of the production of living containers in Vizovice. In 1992, less than a year after the establishment of ACRO, Stanislav Martinec together with Martin Hart founded a new company – KOMA MODULAR, which successfully continued in the production of living containers, and thanks to a change in its position on the sale of its products, fully established itself particularly on the European market. KOMA started to innovate production and build up a stable company, which has become a dominant player in the area of modular construction in the Czech Republic.

The milestones of the company include the launch of production of containers made from galvanized sheet metal, the first rental of living containers (1995), the production of stackable containers, the

development of special modules such as luxurious public restrooms, the development of explosion-proof containers with 8psi resistance, launching the architectural competition “Modular Architecture”, production of the low-energy comfort module, approval of the construction of modular kindergartens in the Czech Republic and the purchase of top-of-the-line CNC machinery for the cutting and bending of sheet metal with significant support from the European Union. Gradual innovations led to the realization of the Czech EXPO 2015 pavilion, winning the “Company of the Year 2015” award, the construction of hotels in Paris, the construction of modular hospitals, the development of design modules for relaxation, and the construction of modular airports in Senegal. Currently, the company is owned solely by Stanislav Martinec, who holds the position of Managing Director, although cooperation with the former owners continues to this day, with Martin Hart remaining at the KOMA Company as its Director of Development and Innovation.

KOMA MODULAR

Module production facility with state-of-the-art technological equipment.

“He who seeks truth shall find beauty. He who seeks beauty shall find vanity.“

(Moshe Safdie, autor Habitat 67)

Modular architecture is a hot topic today, as its environmental and economic aspects increasingly arouse interest among both experts and the general public. Because of its original and controversial esthetics, it is an inspiration for many architects, from young pioneers to world-famous studios. Let us take you on a tour of the most successful and inspirational examples.

“Sustainability is increasingly important. In this respect, it would be interesting to mention sustainable construction and the relationship between a building and local resources and materials. The way this affects the surrounding is that the local materials determine the building’s appearance.“ (Juri Troy)

The talk of the latest trends in the construction business is dominated by discussions on green buildings, sustainable architecture, or if you wish, environmental construction. But what is sustainable architecture? If someone thinks sufficient insulation makes a building green, they are mistaken. A green building must be environmentally friendly in all of its aspects – from its production, the entire life cycle to its disposal.

It is understandable that the degree of environmental friendliness of a building very much depends on the materials used in its construction. We finally see a strengthening desire in Czech society for an environmentally-friendly way of life; however, this is often ill-advised. For example, if someone in the Czech Republic longs for a beautiful wooden house of first-rate Canadian wood and is filled with a warm feeling from living in an environmentally-friendly home just because it is mainly made of wood, they are wrong. The carbon footprint left by the transportation of wood from Canada to the Czech Republic will not be insignificant. Therefore, we need to see a building aspiring to be called environmentally friendly in a complex light. In this light, can an environmentally-friendly building be modular?

The prerequisite for modular architecture to be green is its prefabrication, which ensures the efficient use of materials and the creation of accurate solutions. In the Czech Republic, modular construction is based on the concept of a metal frame, which in terms of the environment is rather unsuitable compared to wood. It is obvious that as a building material, wood, coming from a renewable forest, is more environmentally

friendly than the mining of non-renewable ore, despite the fact that metal can be recycled. Wooden houses are essentially more environmentally friendly than houses whose basic building material comes from non-renewable resources. However, we need to take into consideration the wider picture. What materials shall we use to build houses if quality wood is not available within an accessible distance? How do we cope with the need for “spatial economy” and build an efficient multiple-storey building?

Metal can never achieve the “renewability” of wood, but it goes hand in hand with the regional mineral resources. Unlike the wooden modules from North America, metal-frame modules can be used in the construction of multi-storey buildings. The prefabrication of modules enables high efficiency and the minimum waste of material, which is sorted and recycled. If efficient and environmentally-friendly procedures are adhered to not only by the producers of modules, but also their suppliers, the entire process of prefabrication of a modular building becomes environmentally friendly. We also need to take into consideration the transport of materials, so that the transfer of building materials to the container production hall does not leave a significant carbon footprint.

Environmental modular architecture is also assisted by constant technological developments, which enable modules to be designed that are fully independent, equipped with solar collectors or panels, heat pumps, etc. Thanks to its variability, easy disassembly, the possibility of recycling, excellent heat insulation features, etc., modular architecture offers a number of environmental solutions.

James & Mau + Infiniski

© Antonio Corcuera

Designed by: James & Mau

Location: Curacaví, Chile

Year: 2009

Compared to conventional brick buildings, the Infiniski Manifesto House has a great advantage – the material used in its construction is available virtually free of charge and is fully recyclable. The house is basically made up of four shipping containers. The exterior part of the house is made from wooden pallets. The partitions, floors and part of the facade are made from recyclable material, which is produced in a similar way as paper. It is special artificial wood, which at first sight resembles the classic cardboard boxes for fruits, but has unique physical properties.

Designed by: KOMA MODULAR s. r. o.

Location: Lozorno, Slovakia

Year: 2011

Three low-energy M3 modules were used to build the golf club’s facilities, combining the advantages of modular buildings with those of energy-efficient ones. The heating for buildings built from M3 modules can be arranged by using heat pumps, which further reduces operating costs. The interior partitions in rental low-energy M3 modules are done in such a way as to allow quick rearrangement of the interior space. Any type of siding can be used on M3 modules; it is attached to the skeleton via a wooden grid. In Lozorno, Thermowood heat-treated pine siding was used for the outer shell of the building.

Author: Aitor Iturralde & Carles Cabratosa

Location: Castellón, Spain

Year: 2014

A wooden modular system enabled 100% digitization of both the entire production process as well as the living area in a family house in Spain. Based on this process, the NOEM architectural firm was able to design a bioclimatic smart house tailored exactly to the clients’ needs. The component data was digitally sent directly to the cutting machines during the production process ensuring maximum precision. Thanks to this procedure, significant time and resulting financial savings were achieved all under the control of the

architects and clients. The result is a timeless smart house design that, among other things, can regulate the amount of sunlight indoors based on weather forecasts and, if required, the entire house can be operated with a smartphone.

Author: KOMA MODULAR s.r.o. and Adéla Bačová

Location: anywhere in the world

Year: 2020

In autumn 2020, the Fashion Line design module, developed by KOMA in cooperation with designer Ms. Adéla Bačová, was presented at Designblok in Prague. Fashion Line is a 21st century modular building kit that is completely prefabricated. Each part of this kit is subject to design specifications, but it is only the distinct interconnection of these parts that creates a modern/stylish/mobile modular architecture. The piece system allows users to configure the modules according to their own inclinations. Thanks to the sophisticated design of the parts, it is impossible to choose a “wrong” configuration that could distort the final appearance. Fashion Line received an award in the prestigious Red Dot Design Award competition.

Fashion Line RELAX KOMA MODULAR s. r. o © Julius Filip

What is a module and what is modular architecture? A module is an expression for a certain fixed size, consistent adherence to which ensures regularity in repetition, order and the certainty that individual parts will create a functional whole. The brick, a mass produced construction unit, can be considered one of the first modular systems. However, the term “modular architecture” includes something more. It covers buildings created from prefabricated modular components, similar to bricks; however, the major difference is that these modules already contain living space, which speeds up the construction process.

Modularity also entails clearly defined rules, such as the size of modules. These are produced by serial prefabrication based on duplication, which is why the size of modu-

les cannot be arbitrarily chosen. There are a limited number of versions. At the same time, a module must be easily transportable – its size is thus limited by the ability to transport it and set it down on its designated site. These are the rules we need to accept and play by. Does it seem boring to you? Modular architecture is a game with rules, and aren’t set rules what makes a game interesting?

It is now easy to create modular buildings consisting of one or several units. The use of multiple modules offers a great number of variations. The structure can respond to the outside environment and adjust to specific needs throughout its lifespan. Modularity and the ability to be assembled thus allow for variable expansion or reduction of the building depending on the current and future requirements and needs of its users. On top

“Modular architecture turns the user into a designer, who influences the variety of products offered by a company on the market. As a result, the arrival of modularity has enabled the competence of determining the function and appearance of products to be transferred from the producer to the customer.“ (Ron Sanchez)

of that, modules can be equipped with various properties; they can also contain kinetic mechanisms, which can bring an added value. The limitations and boredom which may be perceived at first sight are compensated for by the high degree of variability and flexibility of prefabricated modules.

Such level of modularity has been seen only recently and allows prefabricated houses to be tailor-made to any wish the customer may have. One of the main achievements of modular prefabrication is that it allows different expectations to be met and at the same time can be precise and fast thanks to the use of modularity and efficiency of modern machinery production. An example of the utilization of modularity is the design of a typical small house for a young family with currently limited financial resources. A family

grows in time, so at the beginning its demand for space is at the lowest. The design of a modular building inherently includes the possibility of expansion. Its square footage can easily be increased proportionately to the growing needs of an expanding family.

The main asset of modularity is the cost efficiency not only in production, but also in the event of any defects arising during the building’s use. Thanks to the modular system, it is not necessary to repair the structure of the entire building, but merely replace the faulty module.

Modularity is a space in which it is possible to move only according to certain rules. However, these rules offer unexpected experiences and excitement. Modularity is in fact a game which can be played by anyone.

Designed by: Ross Stevens

Location: Wellington, New Zealand

Year: 2008

One of the most unique modular houses towers as a stack of containers at the foot of a steep slope. It uses the space between the containers and the inclined terrain to expand the intimate living space to the exterior. The main facade, segmented by the ISO measurements of the container ribs, gives off a very uncompromising, solid, but attractive impression. Thanks to the unconcealed use of recycled materials and components, a pleasant tension between the new and old is felt both inside and out, which gives the house its unique personality and informal appearance with an industrial touch.

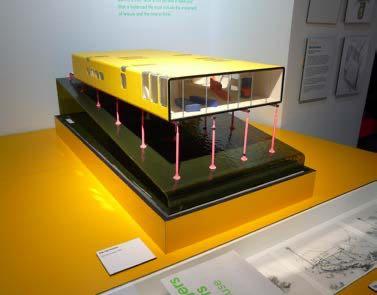

Designed by: Yasutaka Yoshimura Architects

Location: Yokohama, Japan

Year: 2009

A minimalistic modular hotel was built by the sea in Yokohama. Japan is one country that has to import most of its building materials. Unlike the surrounding countries, the prices on the Japanese construction market are much higher due to high labor costs. One way of eliminating this situation is to import not only building materials, but complete

buildings. Bayside Marina Hotel uses the measurements of shipping containers that are fit for long-distance transport. Adhering to the standardized container size made the transport of individual parts of the hotel very inexpensive. Individual modules were made in a factory in Thailand, from where they were transported to Japan and assembled on site.

Author: KOMA MODULAR s. r. o.

Location: Otrokovice, Czech Republic

Year: 2013

The first low-energy modular kindergarten is located in Otrokovice, Moravia, and, thanks to the use of large-space modules, its construction took less than three months. The investor is the Lapp Kabel company, which has built dozens of similar buildings in several countries for its employees and female staff members with children. The

kindergarten provides space for a total of 42 preschoolers in its three classrooms and is technically equipped with solar collectors, underfloor heating, and external roller shutters and canopies, in addition to air conditioning. The material-pragmatic construction is accompanied by colourful accessories.

Author: Chybik+Kristof Associated Architects / KOMA MODULAR s. r. o.

Location: Vizovice, Czeh Republic

Year: 2013

The international architectural firm, Chybik+Kristof Architects & Urban Designers, designed a multifunctional employee canteen for the modular building manufacturer, KOMA MODULAR. The two-storey building, made from nineteen modules in total, is located right on the company grounds in Vizovice, Moravia, and is used for cultural and social events in addition to its main

purpose. The main elevated building of the canteen is completely glazed around its perimeter with large-format shop windows and it is elegantly connected to the outdoor terrace. The façade of the building works mainly with neutral tones of grey and black, while the interior layout is enlivened with bright colours.

Modular Canteen for Employees

Chybik+Kristof Associated Architects / KOMA MODULAR s. r. o. © Marek Malůšek

Author: KOMA MODULAR s. r. o.

Location: Paris, France

Year: 2019

The modular extension of the four-star hotel, LE RELAIS DE LA MALMAISON, in Paris demonstrates further applications of modular construction in practice. The hotel extension contains 28 fully air-conditioned rooms, each with its own balcony and bathroom. The entire extension is four storeys high. The hotel is located in a park, so the

efficient construction using modules, which does not burden the surrounding area with construction traffic as standard construction does, was the main reason why the client, Serie Flex, decided to use this method of construction.

KOMA MODULAR s. r. o.

Location: Prague, Czech Republic

Year: 2021

The design of KOMA RENT’s headquarters was created in cooperation with designer, Ms. Adéla Bačová. On two floors of the building with wheelchair access, there are offices including conference and meeting rooms and a chill-out area for relaxation. There is also a small terrace located on the upper floor for relaxation, which can be reached using an internal staircase one module wide. The building’s interiors are dominated by areas of industrial concrete

and metal décor; they are complemented by solid wood panelling, which in turn adds warmth and cosiness to the spaces. The glazed interior partitions support the airiness of the interior. The large windows with lowered parapets also contribute to the lovely light conditions of the interior spaces. The façade consists of corrugated perforated sheet metal. Allusions to industrial architecture can thus be found both inside and outside of the building.

We live in a century where the movement of people, things and information has become a natural part of our existence. We transport goods over previously unimaginable distances, smoothly fly through time zones to travel to far-away parts of the world in just hours, and in a few seconds we can find out just about anything from the comfort of our homes. Why do we do that? Is it in our nature? Are we still fundamentally nomads and explorers longing for knowledge and experience, or are we becoming too lazy to move and thus have everything brought right under our nose?

From time immemorial, people have traveled the world looking for the most convenient place to live, looking for the ideal home, a place where they will prosper, start a family… The human need for a home is unwavering; it is a prerequisite for a happy life. People look for a permanent refuge, and when they find it, they adapt to it. It can be in the mountains, by the sea, in the desert, in a city or in the country. At a certain time of one’s life, a person has to decide. He has to say: “HERE is where I will live and work. HERE is where I will build a house. HERE is where I will raise my children. HERE is where I want to die.”

Can we imagine our stationary HERE, often firmly rooted on Earth’s surface, lifting up and following us as we move? Can we imagine our HERE moving THERE, so that we wouldn’t lose our home, administrative building, or hospital, for example? Is it possible to create a new HERE somewhere else, even if only temporarily, because both HERE and THERE is our HERE?

Are we able and willing to accept the idea that a man is in fact a nomad who is losing his need to be rooted in one place? Can we admit that our existential desire to have our immobile HERE actually limits us and makes us unhappy? Could we and would we want to move our home with us, be it over short or long distances? Or is this notion a thing of the past and do current trends bring us back to our roots that are firmly planted in the ground?

Either way, we cannot ignore the fact that movement and the characteristic temporality are natural and enriching for man. It is true that moving, not only to a new home, but with one’s existing home, still sounds like science fiction. However, mobility is part of our lives in more common situations.

Seasonal and sporting events, festivals, fairs, temporary accommodation and offices in need of facilities must quickly meet various demands connected with a particular type of event, need or location. It is not desirable for festivals to leave behind permanent public restrooms, changing rooms, box offices or shops. Modular shops, pavilions, restrooms or offices with the much appreciated feature of adaptation are already available and will most likely continue to be used in the future. Mobile temporary buildings enliven public spaces without having a definitive shape or location. Mobile modules are not affected by the whims of time, the climate or fashion. Mobility, movement, the transport of products and their re-use are an effective form of recycling and sustainability.

“The Information Age whets our appetite for the discovery of the unknown. We are standing at the threshold of curiosity and motion. … We are ready for more than just sharing information across long distances; we are ready to physically update this information.“

(Jennifer Siegal)

Hypercubus STUDIO WG3

Designed by: Studio WG3

Location: Austria, anywhere in the world

Year: 2012

The Hypercubus project is an attempt at a new interpretation of the hotel concept. As a logical outcome of the innovative concept, a design was created with a characteristic architectural expression, sophisticated functionality and intelligent construction. The name Hypercubus, derived from a geometric shape, is the name for a mobile hotel room designed for two persons. The equipment of the mobile rooms provides independence from external resources, which allows its use as a temporary unit as well as its assembly into larger structures. These properties and easy transport are suitable for both seasonal and long-term use in various locations. With its concept, Hypercubus falls into the category of “minimal housing”.

VIP restrooms

KOMA MODULAR s. r. o. © ADCO

VIP restrooms

Designed by: KOMA MODULAR s. r. o.

Location: anywhere in the world

Year: 2011

KOMA MODULAR, in cooperation with its European partner in the area of mobile sanitation systems – TOI TOI & DIXI and ADCO, developed and produced two prototypes of luxury men’s and ladies’ sanitation containers with an attractive atypical paneled facade. These restrooms are equipped with high-quality fixtures, special lighting, and audio and video equipment. Entry is through automatic glassed-in doors. Notification on whether a toilet stall is vacant or occupied comes in the form of a strip of green or red LED lights.

Author: ÁBATON

Location: Spain

Year: 2014

The mobile home project by the Spanish studio, Ábaton, reflects several fundamental architectural themes that architects around the world have been grappling with for a long time. First and foremost, it is the design of a mountable and transportable unit that can be placed practically anywhere. Its proportions are the result of long-term study by the studio. It consists of three separate spaces with an area of 27 m2 (9x3) with a gable roof that reaches a height of 3.5 m. The kitchen and living room, bathroom, and bedroom for two people form a harmoniously conceived interior in spite of its modest dimensions. Large glass panes open the interior up to the surroundings and, thanks to the solid wooden construction, virtually the entire unit can be recycled.

Author: MAPA Architects

Location: Maquiné, Brazil

Year: 2013

The MINIMOD project by South American firm, MAPA Architects, is a prefabricated module with a total area of 27 m2 that takes advantage of all the luxuries afforded by factory production. Tailor-made for the client, the building can be manufactured in six weeks; then it is simply loaded onto a truck and transported to the client’s site. Thanks to the steel frame construction of the module, clients can also choose their

own composition of materials for the interior or façade. The unit can thus serve for both residential and commercial use – the project is also very environmentally friendly as it requires no major ground intervention. Individual modules can also be interconnected to form larger units. The price can be expected to be roughly USD 1,000 per m2

Exhibition Pavilions at DESIGNBLOK & FASHION WEEK in Prague

Author: KOMA MODULAR s. r. o.

Location: Prague, Czech republic

Year: 2016

CITY design modules manufactured by KOMA MODULAR served as exhibition and sightseeing pavilions at the Holešovice Exhibition Centre in Prague as part of the DESIGNBLOK & FASHION WEEK show. The company used the easily manipulated and structurally simple edifices to present modular architecture. The modules, based on a trapezoidal

floor plan and designed by Chybik+Kristof Architects & Urban Designers, can be combined and mutually interconnected, while the side sections can be completely glazed. Such modular units are being increasingly used for one-off events held in city centres.

Recycling, i.e. the idea of re-using what has already been produced, is a natural result of environmental efforts and a way to reduce the wasting of resources. The savings brought by recycling are based on the notion that a product does not lose its value, but gets reused in a new context, and our environment is thus not burdened with new waste. In recycling, the way a product is used, and also its structure, shape and color, often change. A recycled product can be appealing and desirable.

How is the idea of recycling related to modular construction? Do we want to and can we live and work in waste, in a used ISO container which was transported by sea, air, railroad and trucks? In contemporary container architecture, which is quite popular around the world, the answer is unanimous. And we are not talking about any “shabby” buildings, quite the contrary.

ISO containers are used to transport all kinds of goods. However, their lifespan, i.e. the time for which a container can be used for its primary purpose, is surprisingly short, even though they are built to last. Containers are often used only for one-way trips, as it doesn’t pay to send them back empty. As a result, non-recycled containers turn into an ever increasing amount of waste. However, these useless standardized and

unified containers, which correspond with minimum living space requirements and allow easy handling and stacking, can find a secondary use in architecture and the building industry. Building a home, restaurant or office from shipping containers that bear the attribute of waste, but also a patina of world travel, is in a way a symbol of controversy and revolt. Unfortunately, the system of mindless consumerism, which is manifested by the constant consumption of new things and the production of an endless amount of waste, is strongly rooted in the minds of most people in western society. Thus, the effort to reuse this waste is like swimming against the current.

The point of container architecture is not to directly compete with existing construction technologies, but to offer an alternative, which can bring a number of advantages. One of the most significant pros of container architecture is the economic aspect, especially today, when the demand for budget housing is high. Moreover, buildings made from containers can boast unique informal industrial beauty. Following relatively easy modification, containers meet the standards of modular cells and offer a wide range of uses and functions. Nothing stands in the way of architects’ imagination in starting the process of an endless container recycling adventure.

“Modular architecture is very attractive to the most of the architects … but most of the attempts fail due to the high price or because the project is over-designed to meet the taste of the masses, which eventually means high price of production. Actually the only part of modular architecture that has overcome this obstacle is container architecture, also because modules are not designed for this purpose and can be just taken from the transport chain when they are needed for construction purposes.“ (Jure Kotnik)

Designed by: Keith Dewey

Location: Fernwood Village, Canada

Year: 2006

Zigloo Domestique is a 2-bedroom, 2-bath family house built from eight shipping containers stacked one on top of another on three levels. The ideas of the project are recycling and efficiency. The outside of the house does not conceal but rather accentuates the industrial rawness of the containers with a shiny coat of paint. Also the original signs and markings on the containers have been left on purpose. Its wood consumption is only about a quarter compared to that of a standard house in Canada.

“When people see this house, they don’t say: ‘What is this?’, they say: ‘Oh, it’s a house and a very interesting one, too.’ It’s not an exaggeration. But creating a house like this requires a bit more creativity and determination.“ (Keith Dewey)

Designed by: Bijvoet architectuur & stadsontwerp

Location: Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Year: 2005

The terrace restaurant Wijn of Water consists of nine 40-foot shipping containers. The building was designed with regards to its temporary character and tight budget. Its technical installations have been effectively placed on the outside. Upon entry, the restaurant opens up with a terrace facing the Maas Canal. On the top floor, there are offices and a technical room. The building makes subtle use of the contrast between the city skyline and the view of the river. The vertically positioned container creates a landmark and the L-shaped arrangement of the ground floor protects the premises from winds.

Designed by: Poteet Architects

Location: San Antonio, Texas, USA

Year: 2010

The sustainability of this house does not rest merely in the recycling of a ship container. The green roof is separated from the top part of the container and provides shade and air flow. The interior is insulated by spray foam and covered with bamboo panels, both on the walls and the floor. The wastewater from the sink and shower is used to

water the plants on the roof. The house also makes use of other innovative materials. The container is set on foundations made from recycled telephone poles, the terrace from air-ventilation padding placed in a steel frame, and the exterior light fixtures are made of disc plow blades that are commonly used and accessible in Texas.

Author: Arcgency

Location: Copenhagen, Denmark

Year: 2015

The northern harbour of Copenhagen is currently undergoing a major transformation as factories there have outlasted their original purposes. The Unionkul Project is a temporary modular administrative building that can later be relocated to another site thanks to its construction from shipping containers. At the same time, it is something of an experiment in prefabricated architecture, offering both functionality and high flexibility at low financial cost. The containers are stacked up to three storey levels and offer spaces for offices, meeting rooms, and storage in their layouts. Insulating sandwich panels are fitted directly into the frames, and the easily accessible technical wiring allows for easy maintenance. The entire building is finished in grey paint to reflect the industrial character of the environment.

Author: KOMA MODULAR s. r. o.

Location: Prague, Czech Republic

Year: 2014

The minimalist building consisting of two prefabricated modules is located in the immediate vicinity of a high-traffic Prague junction, the Prague Main Railway Station. It meets both the needs of SIXT Speed Lease car rental and is also a security facility for the adjacent car park. The solution of the building made of pre-manufactured modules was arrived at mainly for the ease of han-

dling and speed of installation. In addition, the train station lobby is located below the structure so it was practically impossible to build anything other than a modular construction. The exterior steel-sheet cladding in neutral anthracite colour reflects the industrial container origin of the modules, while the interior is defined by a distinctive bright orange painted finish.

“Give a client the container frames, instruct him, and let him fill them up as he likes (space, materials, colors…) so he can identify with the building. That’s what I call architecture.“

(Han Slawik)

(Han Slawik)

In this day and age, individuality is encouraged in the developed world. Virtually everyone has the need to distinguish themselves from others. People set themselves apart by their clothes, perfumes, tattoos, hair-styles, body piercings, sports, pastimes, the films they watch, the books they read, or the way they bring up their children. Each person is unique and wants to be unique. Freedom and people’s relative affluence allow them to lead rich, varied lives. These needs also include the desire to live, work and do business in a unique environment, in an original building which can meet the individual needs of each and every one of us.

Originality, uniqueness, exceptionality, distinctiveness, design, unconformity, functionality, practicality, accessibility, transportability, durability… These are just a few of the qualities that people look for in

buildings for their professional and private lives. Is it possible for one replicable system to meet all of the above-mentioned expectations? Is it possible that a unified construction system could offer all these qualities, to which we could add the requirement for high construction speed, the need to minimize the environmental burden on the surroundings of the construction site, and the necessity of an affordable solution? Isn’t it a contradiction in terms – a replicable system and at the same time a unique solution?

Modular architecture is produced by prefabrication, which is based on a simple replicable construction. That presents a certain limitation – the construction is always the same… While such constructions in Europe are mostly made of metal, North America uses predominantly wooden constructions. Prefabrication means that a factory pro-

duces either one or the other. However, variability starts with the construction, as it offers different sizes of blocks and cubes. Further development could also offer other geometric shapes; however, the ISO measurements of living containers refer to their origins as shipping containers – their clear and practical orthogonal shape. This boxy character is disrupted by further modifications and the subsequent building process, which creates tension resulting from the “breaking of rules”.

As we can see, modularity itself is sufficiently variable. The true inventiveness and experience of originality of each building comes when choosing the facade and arranging the modules. The sandwich structure of walls allows the use of practically any type of facade. Its application is not a problem, either, as it is usually done at the factory. Combining modules and their arrangement