Paprika Paprika Art

By Skylar Li

By Skylar Li

By Skylar Li

By Skylar Li

An always renewed series, since it prides itself on its “experimental animation”: no episode is similar to another. Which does not mean no consistency bonding each of them, or no general scenario ongoing: but both of them are absolutely haphazard, and it makes the anime all the more funny, which it is as much as it is possible to be.

By Riichirou Inagaki

Fall 1999, J.C.Staff Directed by Shinichi Watanabe 26 episodes

By Riichirou Inagaki

Fall 1999, J.C.Staff Directed by Shinichi Watanabe 26 episodes

adventure full of scientific endeavors that is Dr. STONE Although one could argue that Senku’s accomplishments are wholly unrealistic and far too simple to ever replicate, it doesn’t distract from the fun escapadesSenku and co

undergo to revive humanity from literal rock bottom.

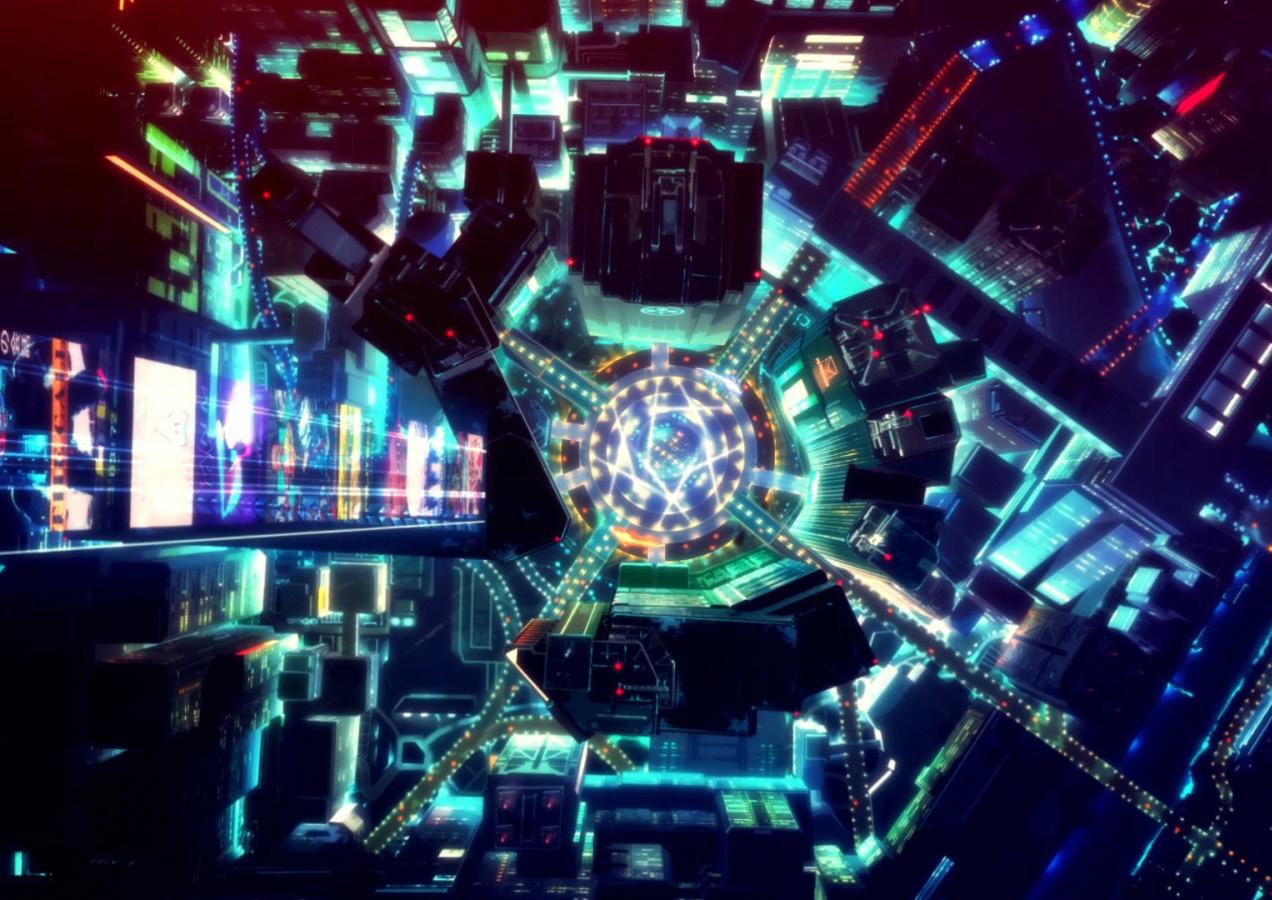

Redline is a movie about many things. It is about a man, a car, racing, love. Those who have seen it know it needs no introduction; nothing short of the viewing itself can really do so in a way that does it justice.

To give a brief synopsis to those who have not seen it: Redline is a very visually engaging movie set in the sci-fi future, concerning extreme pompadour-rocking driver J.P., and his undertaking of the legendary “Redline” death race, the most popular event in the galaxy. It is wild, fast paced, and contains absurd vehicular action and is stunningly animated. Every second of it feels practically alive, in motion, and oft best described as visually insane and artistically inspired. I must forewarn fairly - spoilers do lie ahead for the rest.

As much as Redline wastes very little within its short runtime on anything but the racing (and a bit on the romance), in the end, it is a film about the value within obsolescence – a message that is as relevant in its futuristic alien setting as it is now, both within its focus and abroad.

To start, this focus is quite hard to catch on the first or even second view; only paying attention to it does one see the thread laid from beginning to end. It lies in the very core rule (of the very few) that governs the actual race itself –entrants must be using vehicles powered by combustion engines. The manner of propulsion and indeed whatever fuel or architecture of the engines seems effectively ungoverned, from hover fans to legs to the classic wheels, but the rule remains consistent and explicitly stated.

This would, to an uninitiated observer, seem either an odd or meaningless re striction when taking to consideration that hovercrafts mounting homing rock ets and cannons are equally legal entrants as J.P.’s Trans Am 20000, a normal car by comparison. Despite this, however, none of these vehicles are in any way relevant to the universe they operate within. For all their speed or weapons, they are lesser than what is the standard of the time; anti-gravity powered vehicles. That power source seems the usual for all vehicles not seen participating in the race, from the mafioso’s large and luxurious observation vehicle to the chop per-esque motorcycle J.P. makes use of before the big race. Furthermore, it’s noted by J.P. that they provide a ton of power, as the bike clearly gets out of control immediately even from his highly skilled hands.

One must ask themselves – if this is the newest standard, and it wholly out classes the focal competition point in the race, then what is the point of bringing it up in the narrative? Why even add a detail like that, or take any time to men tion it (or simply make the cars run on the most advanced engine – it is a sci fi setting, after all)? In a sense, it seems to devalue the racers’ rides if they’re portrayed as the best, yet outclassed and inherently obsolete no matter how

advanced they are.

This fact itself though shows the film was produced by those truly passionate about classic cars and racing, and why it’s an absolute enduring favorite of yours truly. Long before I became an anime fan, I grew up with my father taking me to car shows and events. Going to events and seeing collections and ap preciators of vehicles older than we were is heartening, awesome despite their oft lackluster modern performance or features. The pinnacle of many a classic car fan, no matter the era, is the annual Rolex Monterey Motorsport Reunion races, where people from all corners of the country and globe bring their very best of every era to participate and gather in era-staged races around a proper track. This itself can be from a moving museum to cars created less than two decades ago, and it never fails to excite me at attendance.

In some sense – by many a critic’s assessment – this event is inherently mean ingless in its excitement value. None of the racecars at those events can hold to a modern F1 car, and almost all of them fail in terms of power, torque, fuel econ omy, and performance to today’s most cutting edge consumer electric vehicles. By all accounts, those interested in performance should be most excited by the Tesla smoking the 60’s sled in the dust, or at the very least more interested in the pursuit of that pinnacle than beating a half-century-dead horse. After all, what’s the point? Those vehicles are outdated, obsolete, unsafe, and no mat ter what will lose to the new paradigm of the era. Why do NASCAR stock cars use 5-speed manuals, when automatic race clutches shift faster than drivers can think? Really, outside a museum or maybe the aesthetic, why does anyone care?

The beauty and excitement of it, as Redline well exhibits and understands, isn’t about the death-race’s cars being the very best – it isn’t the point to make the most supremely overpowered vehicle. Rather, it revels in the creativity and the quirkiness of the obsolete; the lack of pinnacle capability forces room for user error in variables or deficits otherwise eliminated to computerized minimums by the most advanced technology of the era.

J.P.’s Trans Am 20000 using an oversized, custom-fit, highly temperamental en gine block is made irrelevant next to the anti-gravity film chase craft that easily keep up with the racers, but the viewer’s eye isn’t drawn to the latter. The race has more excitement when things are left to chance and skill – in short, the human element. The same can be said of the modern-day car, rapidly falling behind its electric successor, or any other case of stylish obsolescence. The work of the past – and the extent to the work capable with those tools – is thus rendered meaning anew, pulled from its irrelevance to continued excitement. The human condition is such that we are romantics, no matter the setting or era, be it here and now or far flung into the future.

To that exact love, Redline is a soliloquy: to the pointlessly irrelevant, to the value of the valueless, to driving fast in something old.

One could say that it feels somewhat… fresh.

I find that the point of no return for most franchises is generally when they start listening to their audiences. While responding to audiences or any outside forces is not inherently awful, as they provide good feedback in refining a work, too much results in pan dering and a series feeling artificial. The existence of the later Macross entries which essentially copy the same formula as the original with one or two small changes (which in some cases ret conned the very message of the entire series) is a good example. While I find Macross 7 enjoyable and Frontier passable (buoyed by its excellent soundtrack), their very existence comes from creators responding to the aspects of the original that fans were particularly enamored with. To me, they don’t feel complete in of themselves anymore, as to fully grasp the meaning behind these series, the viewer has to understand the metafiction. Hence, I find that series driven by fan appeasement results not just in more limited thinking, but an inherent dynamic of needing to “see behind the curtain” in a sense and thus they lack the magic that makes captivating narra tives engaging. Frankly, this is definitely a personal complaint. I’m not trying to argue for why my perspective is the correct one or why people should agree with me; rather, this is just to illustrate where I come from when I discuss entries in franchises with numerous entries, like Precure

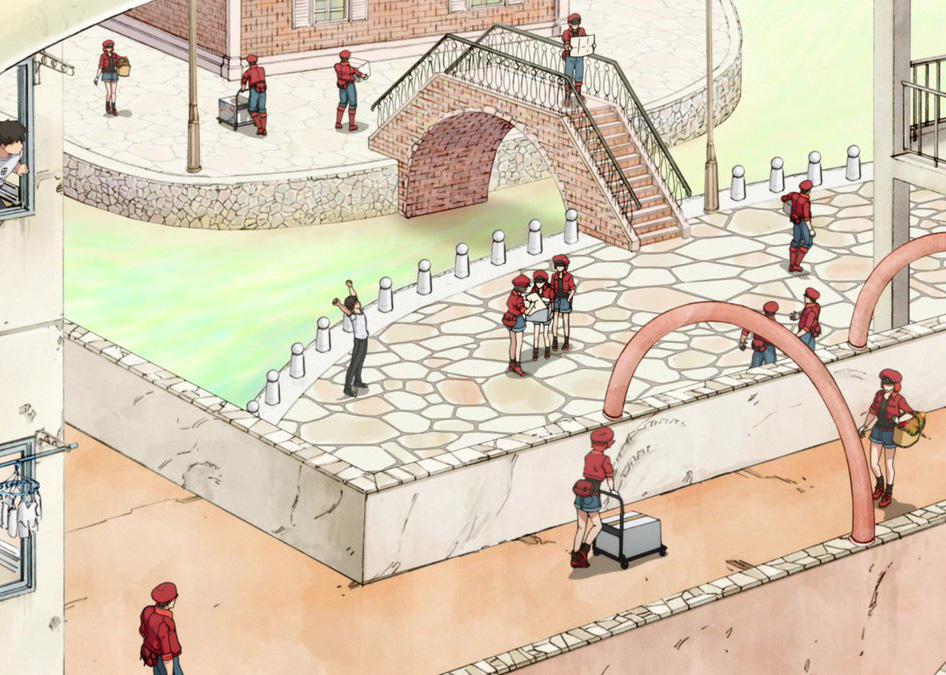

Although, the dynamic I described earlier isn’t exactly the best way to talk about Precure in a chronological sense, if only because the series has always been made to pander in a specific way to its au diences. The original entry, Futari wa Precure, essentially existed as Toei Animation’s attempt to engage a broader group of viewers in a magical girl show in the same way that Sailor Moon had wider appeal in its mix of magical girl tropes and elements from more tra ditionally male-oriented media. Precure's way of going about this

was to add aspects from battle shounen, namely the over-the-top choreography made famous in series like Dragon Ball or One Piece To say that this formula was a success would be an understate ment, as Precure has emerged as a huge cultural institution. Its audience consists not just of the directly targeted demographic of children, but also a wider otaku audience that has the disposable funds to spend on merchandise, perpetuating the corporate engine. Again, this feels reminiscent of how battle shounen have appealed to a wider audience beyond the main demographic of adolescent males. And yet, the first five Precure series, from Futari wa to GoGo! don’t feel nearly as “otaku” as more recent entries. A part of this could be some personal bias due to being born not two years be fore the first entry started – my view of Japanese geek culture will, after all, be more influenced on what I’ve personally observed in my lifetime. Still, I believe that the sixth entry, Fresh Precure, is specif ically the entry that transitioned Precure into more of a crossover hit compared to its predecessors, which merely borrow elements from other genres.

I say all that, but Fresh isn’t all that different from other series in the franchise, especially in the context of media as a whole. It’s not like comparing, say, nuclear engineering and philosophy. Fresh still features two to five girls bestowed with the magic power to transform into super sentai-like heroines in order to fight great evils that threaten the fabric of the world. Where it differs is in its presentation, characterization, and tone. The most immediate difference one can see between Fresh and its predecessors are the far more complex character designs. One look at official art and concept sheets shows that the characters in Fresh have designs that I can probably best describe as being extremely “otaku”, with a large amount of frills, ribbons, and other aesthetic additions that the label implies. It doesn’t exactly animate too well, but Fresh’s intention for more wide appeal is obvious even in this aspect.

The aspect which I think best benefits from this, though, is char acterization. Rather than featuring bland faceless monsters as

villains, Fresh’s villains are mostly human. I say this both as a de scriptor of their humanoid character designs, as well as the way their character arcs are written, although these two aspects are correlated to an extent. Previous entries mostly had their protago nists fight generic monsters, which didn’t exactly lend itself to deep character writing or interesting dynamics between the heroes and villains. In contrast, the villains of Fresh are not just “good for a kid’s show”, but outright some of my favorite villains in media as a whole. The most obvious example would be the character of Eas, who takes on a human identity of Higashi Setsuna. As a standard Precure villain for the first half of the show, Eas’ role mostly entails siccing monsters on the main characters on a weekly basis. Yet, throughout these appearances, she continuously finds herself in teracting with the main cast, particularly Momozono Love, in her human form. This results in Eas continuously contemplating her purpose as an individual fighting for Moebius (the main antago nist). While this plays out somewhat slowly, it culminates in Setsu na eventually rejecting her identity of Eas completely, choosing to assist the protagonists as Cure Passion. The trope of an antago nist becoming a Precure would later be reused in many other en tries, but the particular slow burn of Eas’ character arc is uniquely powerful and is a major strength of the show’s first half.

And yet, Eas is only my second favorite villain in Fresh Precure, as Westar, one of her allies under Moebius, outright steals the show every time he’s on stage. Admittedly, Westar’s arc is largely similar to Eas as a denizen of Moebius’ technological dystopia, Labyrinth. He initially starts out hostile to Earthlings as his assigned task is to conquer and assimilate them into Moebius’ network. Slowly but surely, he begins warming up to the main characters, eventually outright joining them against his original master in the final few episodes. However, Westar differs from Eas in terms of the way his arc unfolds. Where Eas became Setsuna and eventually Cure Passion by meeting the main heroes and having their influence illuminate the truth of their conflict to her, Westar’s shift is more gradual. Westar isn’t exactly brought over to the heroes’ side via some dramatic scene filled with tension and pathos. Rather, he simply begins to understand the flaws with Labyrinth and starts to enjoy his time on Earth. It should be mentioned that Westar is al most entirely a comic relief character, as his schemes to subjugate Earth involve, among other things, transforming a character’s wig into a monster, which makes everyone in their town gain strange hairstyles. And yet, this fact actually works in the favor of Westar’s characterization. Said wig example, for instance, really isn’t thwart ed by the protagonists’ actions. The scheme fails because simply put, the denizens of the characters’ town find their new hair exciting and don’t really mind. This sort of dynamic with Westar’s failed ac tions give him a kind of “Team Rocket” dynamic, which really works in terms of his slow shift from an antagonistic and somewhat off putting “himbo”, to an individual unsure of how to balance his devo tion to his master with his newfound appreciation of the world he must conquer, to an outright ally of the forces of good.

Neither Eas nor Westar’s dynamics are subtle, but they are done very effectively in slow burns that make use of the fact that each Precure entry runs through a full year and has around fifty episodes. Additionally, they show the effect that Toei’s slightly increased fo cus on a broader audience had, as the characterization is simple enough to be understood by children, yet powerful enough to where it can captivate adults. It is this balancing act between the child and otaku audience that Fresh Precure excels at as it conveys far

more depth than a series of this category is typically capable of.

Fresh’s immediate successor, Heartcatch, perhaps walked the tightrope better. Fresh’s conflict is still a direct hero versus villain story, with the antagonist being a technological nightmare hellbent on conquering worlds and collecting individuals as data, opposed by the heroes who stress the importance of human individuality. It’s a fun themewhich gives the later episodes a very interesting visual aesthetic of an extreme dystopia run purely by a computer, but it’s mostly set dressing for the conflict of good against evil. In comparison, Heartcatch’s story is a generational conflict with large implications which it actually lives up to. It thrives not just as a story that is “good for what it is”, but a genuinely captivating tale of an individual trying to live up to the lineage that has been passed down to them. As I described in a previous article, Heartcatch isn’t so much a story of man against man, but rather man against time – its characters struggle in their attempts to be as great as their predecessors and ultimately leave a lasting mark on the world, be coming everlasting legends beyond their days.

Fresh just isn’t that. It doesn’t have nearly the grandiose scope that Heartcatch does. But yet, I like it almost as much, because it’s a re finement of what makes traditional magical girl storylines so good, with compelling heroes and villains. It uses the most narratively cohesive elements that appeal to otaku and rather effectively com bines them with elements that Precure already possessed. While Heartcatch is probably the series I enjoy more of the two, it outright wouldn’t exist without Fresh, which defined the way the franchise would mix its two clashing audiences. At the risk of using a vaguely defined term that is hard to explain, Fresh also has a slight bit more “charm” to it. Heartcatch is an utterly refined work and is close to what I’d describe as perfect in its style, characters, and overall presentation. There’s a sort of amateurish effort in Fresh where it feels as though Toei Animation hasn’t exactly figured out their long term direction for the franchise. This is unlike modern Pre cure series, which feel almost too stale for mindlessly following the direction set out by Fresh and Heartcatch. In no better place can this be seen than Fresh’s first opening, which is a fairly catchy song that fits the otaku-esque feel that the series is going for, yet is sung completely out of tune. A musician friend of mine with no context described it as being mixed horrendously and questioned if anyone had actually properly listened back to it. In spite of that, I find its clumsiness charming in almost the same way I find Westar’s clum sy path from inept villain to goofy hero engaging. Fresh isn’t the type of series that would ever be considered perfect by anyone with its numerous flaws, but it has a unique feel to it. Without ever feel ing like it’s pandering, as the production is far too clumsy an effort to effectively do so, Fresh Precure manages to surpass the original entry in terms of influencing the franchise’s direction, in its blend of different genres and demographic appeals. It possesses a charm that is hard to replicate, and that in of itself is rare in a sequel, much less a series that is the sixth entry in a large franchise. Much like its characters, Fresh Precure does not wish to be but a piece of data as it instead defines the entire trend.

If you’ve ever been on the myanimelist.com forums, you’ve probably noticed that many of the discussion threads for popular anime and manga are either fans gushing or trolls baiting. In a word, these threads are toxic. It goes without saying that the baiting is toxic. Only people with severely low self-esteem get a kick out of repeatedly insulting others because they have differ ing opinions on cartoons. However, “fans gushing” isn’t something most people would call “toxic.” “Toxic” isn’t really the right word for the deeper issue that under lies “gushing” and “baiting.” Alas, I chose to use “toxic” at first because I know it’ll get a greater response from whoever reads this than “unproductive” will, which would be the most accurate descriptor for the gush-bait dyad. Despite ostensibly opening a “discussion” forum, someone who creates a thread to gush about their lat est favorite anime or manga being “the GOAT” isn’t look ing for discussion, which is to say a discourse. They’re looking for confirmation from others. They’re there to learn what they already know. Similarly, someone who creates a thread to bait fans of a piece of media isn’t looking for discussion. They’re looking for fireworks. Some pretty lackluster fireworks in my honest opinion, but hey, it seems like some people are really into that. Why would they spend so much time regurgitating the same talking points to strangers online otherwise? The alternatives are truly frightening.

Of course, there will always be a time and a place for gushing over what you’re into and tearing apart what you’re not, but neither of these mindsets are conducive to discussion. A healthy discussion should not only help you to refine and deepen your thoughts on a piece of media, it should be able to change your thoughts or at the very least enable you to understand perspectives different from your own. To enter such a discussion,

you need to be open-minded, but there’s more to it than that. My intuition (and hope) is that there are many peo ple who have found themselves dissatisfied with this kind of “discussion” of anime and manga proliferating on the internet but haven’t been able to quite put their finger on why they feel so empty after reading most forum threads, reviews, or critiques even if they agree with them (and perhaps especially when they only agree with them). If you just thought something to the effect of “that’s literally me” just now, I salute you! Accepting that you’re lacking something in life is the first step to filling it. That said, the beautiful and terrifying thing about media analysis is, if you take it seriously enough, that lack is never filled! If you’re willing to accept that, then I implore you to start discussing anime and manga (and all other media) productively. Here are some tips for contributing to an analytic discussion:

1. Instead of writing about whether something is good or bad, try writing about why something is interesting

The point of an anime or manga review is to inform people whether a given piece of media is worth con suming. Media reviews are practical and will always have a place, but when discussing media, you have to eventually go beyond matters of likes and dislikes, or how well a show conforms to generic standards of quality, if you want to say anything unique. It’s fine to start with simple impressions like “I think this show is interesting because [insert aspect here],” but rather than explaining your reasoning with your likes and dis likes, actually investigate what lies beneath your pref erences. Say you dislike mecha shows. Why? Maybe because you’re just not into giant robots, or maybe you’re unsettled by how so many mecha shows glori fy militarism and military technology despite the often hackneyed and hypocritical anti-war moralizing of their narratives. The latter possibility, by involving the politi cal stakes that always lurk behind artistic taste, is much more likely to spark an interesting discussion. Now that you’ve thoroughly conveyed why you’re not into giant

Writer

Writer

robots, people can properly respond to your ideas be yond simple agreements or disagreements in taste.

2. Be consistent with your terms and rigorous with your logic

This tip goes without saying when it comes to most writing. Of course, people are naturally inconsistent and irrational much of the time, but it’s important to at least qualify the logical inconsistencies that inevitably come with discussing media when you’re writing to persua sively put forward your ideas. This mandate of consis tency goes beyond simply knowing how to use technical terms like art and animation properly instead of confus ing the two, for instance. It applies to the progression of your arguments. Say I’m arguing that Neon Genesis Evangelion is not a subversion of the mecha genre but a celebration of it. I first need to establish what I mean by the mecha genre and what would count as a sub version of it, perhaps bringing in examples of subver sive works of art from other mediums to corroborate my argument. If I want to persuade anyone, I then have to be consistent in my usage of these terms, otherwise I risk falling back into the purely subjective realm of “I like this because I like it” or “I dislike this because I dislike it.” All discussion of media is subjective at its core, but you can approach a greater standard of objectivity by establishing clearly-defined terms at the start of your argument and sticking to them.

3. Remember that anime and manga don’t exist in a bubble

The example I just gave of looking at subversive works of art from other mediums to help determine wheth er Neon Genesis Evangelion is actually subverting the genre it belongs to would apply to this tip as well. Due to how niche the subculture of the anime and manga fandom can be, a lot of discussion on these mediums assumes that after a certain period they have evolved and are continuing to evolve by and large in a vacuum.

Fortunately, the people involved in these discussions are probably aware that anime and manga do continue to be influenced by other mediums to this day. Howev er, much discussion sticks to comparing any given an ime and manga series only to other anime and manga series. This kind of medium-insestuous discourse has the unfortunate side-effect of downplaying how much anime and manga borrow from other mediums, and not just from mainly visual mediums like film and western comics but from other narrative mediums like literature and plays.

4. Remember that all art and media is propaganda (and that doesn’t have to be a bad thing)

All art is created by people, and art can only exist as art if it’s interpreted by people. People, whether they’re aware, unaware, or willfully unaware of it, are involved in many “projects” simply by living, and these projects result from us investing care into them. “Propaganda” is admittedly a charged term to represent this care that all art is caught up in. “All art is political” or “all art is social” are both ways of expressing the same idea. It comes back to the example I gave in the first tip about how maybe the reason one might not enjoy mecha shows is actually because they think that those shows hypocrit ically glorify war while offering lampshaded critiques of it. It’s always possible to go beyond discussing art simply in terms of taste. The claim that one can have an apolitical aesthetic appreciation of art is itself po litical in how it so self-consciously disavows any politi cal affiliation or social responsibilities. Art is all social, but we are all social beings, so this is both obvious and not necessarily a bad thing. It is, however, something one must keep in mind if they want to go beyond a sur face level discussion of likes and dislikes and delve into what exactly makes those preferences tick and what their broader implications are on a social level.

3rd Year, Philosophy 13/08, the eighth of Undecimber; a great day, since it is the position of that wonderful episode.

Warning: Although this article would hardly be con sidered as a real spoiler, it is precisely hard to read without having seen (or read) the 16th episode of Neon Genesis Evangelion. Watching it right before, right after or while reading it, albeit not necessary, is politely advised.

Neon Genesis Evangelion is more than often present ed – sometimes sincerely, sometimes in a caricatu ral manner – as a series trying to make a philosophi cal or psychological use of its 26 episodes. One may therefore ask, why to select the 16th of them rather than any other. Which question is easy to answer: its very specific action is such that it illustrates maybe at best a crucial, albeit paradoxically also only pos sible, gradation between the three initial “children” –that is, our protagonists. Whereof gradation the sub ject is not easy to express, but might be assimilated to their main desires, or rather even the core of their ethics – the way they act, almost the way they “ex ist”. This gradation, it is unexpected, does not have Rei and Asuka as its extreme points with Shinji at the middle, but Rei between Asuka and Shinji. The first of them to be approached will be the last named, for being the “true” protagonist of Evangelion, he is the one with whom the series spends most of its time, and to whom more happens – especially in that 16th episode, in which he stays absolutely cut off from the rest of the characters and the whole world, in a situ ation of panic which rapidly (… as always in Evange lion) turns out to be an opportunity for the character to think – and especially about himself.

The Shinjian modus is at the end of this gradation because it its the most open to the “outside world” – meaning Shinji’s outside world, which is made up, above all, of persons. On the one hand, the Asukan

modus is concerned with its sole person as an objec tive – which does not mean a Machiavellian picture in which all the others have no reason to be but to be used, but a much more complex and emotional scheme in which the instance of judgement regard ing success and goals is the inner self, influenced and shaped by the outside as it may still be. It is important to remember that this Asukan modus is the way Miss Langley herself puts it, not necessar ily the way she really thinks, feels and behaves –much closer to the Shinjian modus than she would willingly admit. On the other side, that instance is to be found at least partly elsewhere: for Rei, it is one person, Ikari Gendô – whose judgements and goals are almost automatically adopted by Rei; for Shinji, it is “the whole world”. That stance has two possible meanings, which fortunately happen to be here both true: he is desiring to be complimented, reassured by others as a whole or at least by one (for others are the world, or at least the part of the world which is able to approve or reject your person and actions). When he gets trapped, which occupies most of the episode, his words are not: “why am I not able to go out?” but “why does it refuse to open?”, “Open!”; not “Let me out of here”, but “Get me out of here”. Those “others” are summoned nominally (“Misato-San”,

“Asuka”…), until he comes, desperate, to ask “Please, someone help me”. Shinji wants to be “one” by being one-among-the-others, one for the others. Very clas sically, he is because he is recognised as being – and he is what he is because he is recognised as such. Shining possibly less than Asuka does not prevent him – on the contrary! – to “belong to” the social fab ric, for he shines for the others, and the others he ask to help him when he feels helpless.

On the very other end of the spectrum, the Asukan modus also deals with the will of being one, but by being One – that is, a “sufficient”, autonomous entity, not needing these others, able to solve situations on ist own – and better than the others, for the One is ex cellent. This modus means always chasing after that which “shines”, no matter what precisely it is; it might be more concerned with pride and superiority than with belonging and integration. As a certain Aizen put it, admiration is something utterly different from acceptance, if not its very contrary; and it is admira tion that this modus seeks out. Thereby it is almost that of hybris: a permanent tension towards power or at least grandeur, and a real wrath against that which comes on ist way. Whether one “belongs” or not is interesting, however, but above all to the extent that it is a way to glitter: the logic behind is more that of a pyramid than that of a fabric, the idea to be cut off from which sometimes terrifies Shinji. Asuka on her side has already experienced the absolute severing of such bonds – much more harshly than it occurred between Shinji and his father, whose relation could at best be deemed as dampened, and cold when it does not get too hot. Having “understood” that rela tions are things one may too easily lose, she made her modus such that it would be looking after those things one does not share but “possesses” – that which may be grasped, she desires. Shining does

not indeed only mean shining for the others, which is why Shinji does not despise at all such a possibility, but being the one who shines – a quality, an ability one acquires and demonstrates.

The Asukan modus however, in its pride and desire to grow and possess, confronts during that very six teenth episode an hurdle much more impossible to overcome than the Shinjian modus. As our “main pro tagonist” is trapped, far from the sight and reach of the others, in a very Asukan moment, she expresses a bit of laughing contempt for that one who failed – but is got on her nerves by Rei, whose modus is almost impermeable to such demonstrations and who hardly agrees with the way Asuka behaves at that very moment.

The Reian modus is truly the most specific of the three, the most different from any other – while at the same time the middle point; for she does not want to exist thanks to the instance of judgement to which she refers, as Shinji almost does, and nev ertheless abdicates everything on its behalf. That is why one should not be misled in understanding gen uinely, almost naively these ways of being as merely quantitatively different. Qualitatively, they have al most nothin in common; and the nearest happen to be probably the two extremities. Rei does not indeed want to be “one” at all: she wants to act – that is, to abide by the orders of her instance, Ikari Gendô. Whereas Shinji and Asuka try to “be” something in their complex world, one by creating and reinforcing bonds with it, being part of it to the greatest possible extent, the other by dominating and relying as little as possible on it, Rei faces a world essentially con stituted by Ikari and “gladly” – “willingly”, given how little the question of will is present in her case, would hardly be appropriate – obey its law.

These three modi are three ways to be in the world, and in multiple fashions: they deal with ethics (values, and actions – what guides them as well as how they should be performed), inclusion and identity. The Asukan modus is that of the ivory tower one builds – gleaming, solid and sufficient (one could al most say “self-being”); the Shinjian modus is that of a child who wants to help and be helped. One finds his salute in being “complete”, the other in being able to help and likely to be helped – and loved. The Reian modus is that of the devotee (or of a strange lover or very young child), whose actions have no meaning but themselves, for they do not need any further end: they are those which the instance has prescribed –the instance which loves and is loved.

Heybot! Is truly an anomaly, as in, it’s difficult to comprehend how it even managed to come into fruition. It’s a 50-episode ‘children’s show’ that has, to my surprise, somehow managed to make its way onto popular platforms such as Crunchyroll, albeit remaining largely untouched and unheard of regardless. When you see surreal comedy, kids, body horror and gods tagged all in a row, you know something is up. “Who is this actually for?” is probably one of the first things that comes to mind upon booting up episode one, and even after finishing the show, I struggle to fully answer that. Within seconds, the viewer is immediately greeted with its unique brand of absurdity, and the fact that the first three-minutes end up being what would be the circum stances of the penultimate episode before playing it off as a joke is a testament to that; it only becomes funnier when the true penultimate episode makes light of the entire final battle that was supposed to be built up to. As a continual barrage of audio-visual and even emotional stimulus, Heybot! can be a challenging show to take in, but it works on multiple levels, with its structure intriguing enough to where I feel it to be worth a look.

Now, comprehensively overviewing or even accurately explaining what the series is even about is a monumental task, but simply put, joke battles. Yes, it may be difficult to believe, but Heybot! does in deed have jokes. A lot of them are downright awful and some may be difficult to comprehend without knowledge of the language, but I assure you that they're there. When it isn’t referencing everything under the sun, including material that the average Japanese viewer, let alone a child for that matter, couldn’t be expected to recognize, it constantly stoops to the most low-brow humor imaginable with fart jokes, sex jokes and uncanny facial expressions. It’s also extremely meta and breaks the fourth wall on the regular. This is the show that directly asks its viewers to write its episodes and has its discard ed character designs endeavor to become full-fledged characters. Moving on though, these joke battles are conducted through the use of Voca Bots, miniature robots that spew slews of puns through the insertion of Voca Nejis, screws which are used to construct gags. Without any clear idea of what the series is doing, it may not be ob vious what exactly is happening during these segments as they kind of blend into the apparent randomness that constitutes the rest of the show, but they do serve as a general throughline that connects the massive cast to one another and remain relevant in one way or another.

Heybot! feels like a grab-bag of ideas, perhaps stream of conscious ness-esque is a better way to put it. Characters can leap from playing and parodying a slew of video games in one episode to journeying through literal hell in another. Large-scale, universe-defining events

can just unfold on a whim without explanation, for example the so lar system’s obliteration. This isn’t to say that this is an attribute ex clusive to the series, as a multitude of episodic shows also feature characters in wildly different situations between episodes, but a key difference is Heybot!’s self-awareness of its own episodic nature and use of selective continuity. It acknowledges itself as a Sunday morning cartoon where any progress resets back to the status quo between episodes, which are framed as disconnected incidents, to which the characters believe so as well. Well, that is, until it eventually becomes more noticeable towards the end that it doesn’t, and one suddenly realizes that never actually had. Gradual change is inflicted upon the world by the screw-fetishist prince, Nejiru, and companion, Heybot, which compounds until it can no longer be ignored and real ity begins to warp.

The arbitrary becomes important; that is to say, there lies plenty of purpose in the apparent randomness. The series excels in how it wea ponizes its unpredictability, crafting an atmosphere where seemingly anything can happen, and then proceeding to utilize cutaway gags to great effect in disguising its story that’s unknowingly thrown direct ly in the viewer’s face. Within episodic adventures, relevant events could just as easily blend in with aforementioned ‘randomness,’ leav ing viewers oblivious to their significance until it's too late and every thing cleanly comes together in epiphany. Minor characters can have entire arcs in the background of cutaway gags, and it’s not even a stretch to say the fart jokes are actual plot points and a driving force of the narrative at large. It’s all too easy to forget that all the goofi ness on the screen is indeed part of the show’s plot, but in retrospect the foreshadowing is all there.

Returning to the initial question of who the show is actually for, the most reasonable answer may ultimately be the staff themselves. Their care shines through and while it may be my personal interpreta tion, I would like to believe they were having fun in producing the show and mashing nonsensical ideas together, something that the majority of the industry can’t really attest to. While the show is obviously also a glorified toy commercial for the Voca Nejis, Voca Bots and potato snack, Imochin, they’re all advertised the ‘Heybot way,’ meaning in the most chaotic way possible. It sounds counterproductive, but at the same time, it’s exactly the type of thing that Heybot! would do. Despite being repeatedly shown as delicious, Imochin is somehow made out to be unappealing through exaggeration as Heybot continually goes ballistic over it, gorging himself to the point where it becomes dis gusting to fathom purchasing. An entire episode is even focused on the sale of Heybot toys where a less intricate version seeks to murder and replace the original, having felt inferiority brought about by con sumers picking up the newest and fanciest goods. This is the type of approach that the show is founded upon and continues to abide by. For comparison, in the final episode, Heybot! is censored on televi sion and replaced by a safe, unambitious, watered-down version of itself, the stark contrast emphasizing the original show’s personality. It drives home just how different things could have been, and how Heybot! could have easily been a soulless pile of mediocrity amidst a sea of mind-numbing children’s media. Instead, we end up with noth ing less than a small miracle in its creation, as one of the more unique experiences I’ve come across in anime.

Writer MAX R. 4th Year, Japanese Perfect for rewatches.

An utterly insane piece of speculative history with cool mili tary stuff.

Yes, a building like that of the UNO is great — but imagine having a gigantic pyramid underground, and a never ending park around it!

ALEXANDRE HAÏOUN-PERDRIX

ALEXANDRE HAÏOUN-PERDRIX