a golden catbox of memory vol. 59

rahm issue KONSHUU

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the respective author(s). They do not purport to reflect the opnions or views of Konshuu or its members. The terms employed in this specific individual issue and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of Konshuu concerning the quality of any anime, manga, live action television series, or video games, or on the behalf of any creators, or concerning any legal statuses.

EDITOR’S note

KONSHUU | Volume 59, RAHM Issue

While I’ve been a part of CAA for nearly two years, and as I’ve gone through life, I questioned something: what does this club mean to me? I would say this is a fairly reasonable and important question for me to consider, seeing as I am its President now. No clear answer immediately popped up, so I take this page to reflect on my time here.

I joined Cal Animage Alpha as a Konshuu Writer in the September of 2022. I was an inexperienced freshman who had just come out of a sheltered high school experience, and my talent with writing had hardly been developed at that time. I later heard from people in charge of hiring decisions that I was the last pick of the applicants for that season. To think about this now, almost two years later and as the President of CAA, it is hard to know what my life would have been like without either Konshuu or CAA.

As a writer here, I met the closest friends I’ve ever had in my life, and over the course of two years, I’ve grown immensely as a person. I was challenged to think, develop, make decisions, and become a much healthier and happier human being. For the first time in my life, I not only became comfortable expressing myself, but was actively encouraged to do so by my friends. I would say that this change is also observable in my writing. Comparatively, my first article is markedly different from my most recent work, namely in terms of strong authorial intent and expression.

As time went on, I became more active in Konshuu and in CAA. I rose up the ranks, moving from Konshuu Writer, to Konshuu Vice Head, to Konshuu Head, and finally now to President. I made many more friends, and lived a lot more life. Over the course of this period, I saw, read, and otherwise experienced so many forms of poignant art, and the ways it has affected my life can never be understated. And yes, this is in reference to anime, manga, games, and other such mediums. I won’t forget the beauty of Neon Genesis Evangelion, nor Umineko no Naku Koro ni, nor Legend of the Galactic Heroes. However, in spite of this fact, I will attest that making friends in CAA and Konshuu, finding the best version of myself, and living each day to the fullest were the things that changed my life for the best. All of these life experiences and feelings are present and captured in contemporary otaku media, but it will never compare to the real thing itself. And that is what CAA means to me: it taught me how to truly and honestly live.

– Rahm, editor

Mikko Vu, Vice president

Daniel Padaoil, Rahm’s roommate

1) What is your favorite anime, and why? Least favorite (if any)?

Koe no Katachi, it was a rollercoaster of emotions for me and seeing the transformation of the characters really touched me.

2) What are your thoughts on the Rahm Issue?

Cool idea, sounds like a lot of work though

My favorite anime is currently Death Note! The way the story considers every probability and improbability from life-ordeath situations to things like a simple game of tennis makes me interested to find out which character has the better mind games. Any anime I dislike I usually forget about (Demon Slayer) YEAHHHHHHHHH RAHMMMMMMMMM MMMMMMMM THATS MY ROOMMATE YEAHHHHHHHHHHH LETS GOOOOOO NUMBER ONE PRESIDENTTTTTTT

3) Was anime a mistake?

Jokes aside, not at all, it’s changed many people’s lives including mine and its allowed me to relate to many people, allowing me to make friends and have a more enjoyable life.

No because it made Japan and ramen REAL

KONSHUU | Volume 59, RAHM Issue

����

No

My “Ojamajo because yet by Mappa. anime because yet by Mappa.

Rahm has

Wai Kwan Wu, held captive

favorite anime is “Ojamajo Doremi Dokka~n!” because I haven’t seen it but I heard it’s animated Mappa. My least favorite anime is “Chainsaw Man” because I haven’t seen it but I heard it’s animated Mappa.

3 CENT CORNER

Ara Cho, one of the cool awesome hip heads

My favorite anime right now would probably be, skip and loafer, I think the art style is so cute, and one of those romcom animes I would watch back when. It just brings back a lot of nostalgia for its style and story. My least favorite would probably be Code Geass cause I don’t freak with the art style.

Suzuki, current Events Head Officer!

My favorite anime would be 86! The show does a good job contrasting life on and off the battlefield, and it also does a good job showing how easily we take some things for granted.

Willow Otaka, #1 glasses enjoyer

���� wait it’s all the Rahm issue? �� always been

I freak with the Rahm Issue.

No but your mom was

I thinks its revolutionary, but it definitely had its weird moments, but overall I think anime in itself is inspiring. It’s a whole new way of story telling that a lot of people can adapt to. I freak with anime.

Maybe.

is best president :D

I like whichever anime has a glasses main character

Rahm is my favorite glasses wearing anime boy

No, but contact lenses are

Toshiro

Rahm

My favorite video game of all time is Heaven Burns Red, released for smartphone devices and Steam in 2022 and 2023 respectively. I believe that this game has many extremely unique and important ideas within the realm of gaming that have gone monumentally underlooked and underappreciated, and Heaven Burns Red’s unconventional blend of RPG combat, anime-inspired OST, and visualnovel story segments contribute to make it a masterpiece of gaming and of art. The reasoning for these claims is that this game is very good, and that you should just trust me and play it.

This feels unsatisfying, right? It’s probably not what you were looking for. Well, when you clicked on this article or flipped to this page, what exactly were you looking for? It stands to reason that given the thematic focus of this magazine on the anime and otakurelated media sphere, you probably were interested in something at the very least remotely tied to Japan that offered an engaging read. Perhaps more specifically, with the awareness of this publication being student-run, you might have been curious about the opinions or thoughts of college students nowadays. Maybe you even saw the first few lines of text or the header image, and thought the subject matter would be an interesting glimpse into modern pop culture. Or the last and most likely alternative is that you, subconsciously or not, wanted to measure your own ideas and philosophies against that of the ones presented here. Are your own conceptions about anime, manga, games, or some other media reasonable or relatable, based on what

you read and see in this magazine? Or anywhere else?

The truth is that every editorial you read here will most likely be subjective. This characteristic is not unique to Konshuu, and mirrors the broader landscape of contemporary media discussions nowadays. With the relatively new advent of the internet, each person’s words are becoming increasingly drowned out in the sea of everyone else’s ideologies, in a contest to see who can be the loudest and most enticing. Even without the internet, your own worldview is

formed through the people whose lives inform your own, as well as from the reactions of others to whom you’ve relayed your own experiences. Not a single piece of your set of beliefs is untouched by some other extremely subjective source. You probably understand this fundamentally, and yet there is a high chance that you were reading this publication to have the subjective opinions of this magazine’s staff juxtapose your own. While this view is largely permissible to a mainstream audience, especially given the context of articles like these relating to “fun” and “niche” pop culture topics, the inherent subjectivity of any writer in this field often goes unnoticed, even as readers formulate their opinions based on that writer’s narrative. At what point is the responsibility of other people’s opinions on the consumer? For instance, regardless of your sentiments about my brief overview of Heaven Burns Red, you are predisposed to accept that the presented opinions are legitimately mine. There also lies a deeper inclination to believe the accuracy of the facts I’ve told you. But, I actually lied to you in that first paragraph. You probably don’t know if Heaven Burns Red is even on Steam; it could instead be on the Epic Games Store. Or it might not even be available on computer platforms at all. Heaven Burns Red is not actually my favorite game, and there’s a chance I may not even like Heaven Burns Red at all. This game I’ve been mentioning might not even exist. And yet there is a chance that if I had not told you this, you would go out into the world with these potentially false statements, none the wiser.

The moment we consume analysis, critiques, or reviews, we have the tendency to put a lot of faith in the person presenting their case. We trust that they’ve done their research, or at least know how to formulate their ideas in a semi-enjoyable format for the audience. After all, these authors often seem to be qualified, whether it’s because of their position, experience consuming media, ways in which they communicate their thoughts, or any of the possible permutations in which we could appreciate their musings. But because of every human being’s subjective nature, a person’s view will

KONSHUU | Volume 59, RAHM Issue

Reality &

Subjectivity &

always run the risk of not resonating with their listeners, no matter how qualified the person might be on paper. This conflict has fostered an environment where many of the most popular writers and content creators prioritize vying over their audience’s attention, rather than trying to deeply communicate with them through their preferred platform. And, due to this strategy proving itself to be successful through the avenues of clickbait and promises of virality, the cycle of distorting reality to gain an enjoyable subjectivity persists. This phenomenon is even reflected in the language we use to refer to these works now. Rather than defining any one piece as an “article”, “video”, or “artwork”, the most common label these fall under now is simply “content”. The word “content” communicates that the nature of art and expression found in these mediums is becoming far less significant or profound, or perhaps most worrisome, far less entertaining. This shift calls into question why we place value in these kinds of literary creations and creators in the first place. While some will be satisfied with simple entertainment, the purpose that many writers aspire towards is to enhance an audience’s understanding or appreciation of a topic or piece of media. This goal is morally admirable, but the results of this effort are most often delegated to only a small percentage of the audience’s day-today attention and thought (let alone memory), meaning that the chance of positively contributing to a wider conversation for most writers is extremely small. The more a person’s opinions are built from their own experiences, the less chance they will resonate completely with others. And yet, the more a person’s opinions are influenced by others, the less they are able to meaningfully say. It’s quite the predicament, isn’t it?

While many creators will have no issues over this dilemma and will evolve their work to exploit their audience’s ways of thought, many responsible ones have decided that setting some kinds of ground rules with their audience would help build honesty and respect. Whether these be statements of impartiality and accuracy, spoiler and content warnings, or even disclaimers stating how everything presented is simply one’s own opinion, these rules try to at least establish a shared baseline with the audience of what should be considered “reality” in that moment. While there is a certain level of inherent abstraction with how these boundaries are set, this action works at endearing the audience to the writer’s commitment to being transparent. But, whether or not these rules are effective, the sheer abundance of them across media often desensitizes people to the point where any striving towards transparency doesn’t make any noticeable difference in an audience’s perception. The truth is that this attempt at agreeing upon a shared reality, for all its good intentions, has become far more disposable and far less valuable than publicized opinions, due to current social trends emphasizing stylization and entertainment over the less-stimulating facts. This is not to say that the idea of reality is worthless. Obviously there will always be those who seek intellectual satisfaction from discovering the objective truth, but this concept of a de-emphasized reality seems to suggest a deep desire some people have for a stimulating entertainment above all else. The easiest comparison to make between separating the ideas of reality and subjectivity is to something akin to splitting yin from yang. Without one, the other holds no meaning.

At around this point, I would probably conclude with my own opinion on the topic of subjectivity, and perhaps subtly encourage you to share it with me. However, given the context of this article, this approach seems pretty hypocritical. Instead, I will conclude by giving my opinion on another matter entirely, hoping that my musings for the past two pages were in-depth enough to establish some level of confidence between you and I, to where you might hopefully believe this next statement of mine.

Heaven Burns Red is very good, and you should just trust me and play it.

This was probably inspired by my Umineko theorycrafting… Rahm Jethani staff writer

MUSIC FROM A COLD LAND

KONSHUU | Volume 59, RAHM IssuE

残響のテロル

The music found within Zankyou no Terror possesses a musical distinctiveness that sets it apart from many other anime soundtracks, only comparable in flair to the chilled Western-inspired hip-hop ambiance of Samurai Champloo. Emotions evoked by these compositions span a spectrum from solitude to optimism, resonating with the listener in various ways. Noteworthy is the experimental Icelandic influence, notably drawn from artists like Sigur Ros, Bon Iver, and Jonsi, which distinguishes Zankyou no Terror’s OST from the typical anime discography.

It is difficult to talk about Zankyou no Terror’s soundtrack without mentioning the prolific musical palette of its composer, Yoko Kanno, whose Western musical influences influence each of Zankyou no Terror’s songs in unconventional ways. The music with lyrics, aside from the Japanese openings and endings, is all sung in either English or Icelandic which in the context of the anime’s setting and plot, can make listeners feel wistful and out of place. The most effective song that is able to exemplify this is the song ‘Von’. Not only does it stand out in terms of its potential to stir intense emotions, but also for its usage resonating with the anime’s core musical aesthetic.

‘Von’, meaning “hope” in Icelandic, plays the most emotionally high-stakes moment in Zankyou no Terror. In the scene, multiple lives are at risk. Furthermore the setting of the abandoned neon ferris wheel in the middle of night creates an aesthetically contrasting scene. But despite the energy and tension of this narrative and visual backdrop, the song ‘Von’ is simple in most ways. With a slow tempo and simple repeating piano loop, listeners are lulled into feelings of hopelessness and numbness. The sense of dread conveyed by this song is what makes it so fitting for this scene. This feeling is then amplified by the vocals of Arnor Dan’s soft, ethereal falsetto. He repeatedly sings ‘Vetur, Sumar, Saman Renna’ (translating to “Winter, Summer, converging”). This is in reference to Lisa’s descriptions of Nine and Twelve, and the vocal anguish used when repeating the line can be used to interpret the feelings of both Lisa and Twelve in this scene. Each further verse and added string section only serves to heighten feelings of despair and drama, as the ferris wheel scene becomes more and more heartbreaking.

The instrumentation of ‘Von’ does border on melodramatic, but the simplicity of the composition allows for the piece’s placement in the episode to feel natural. Achieving this feat despite the potential mismatch of a tense and dramatic scene with a painful, cold song is impressive, and I commend the effort put into making this choice work.

The unique atmosphere created by the song remains unparalleled by any other anime. While I recognize that “unique atmosphere” is subjective, especially in music, it is not a stretch to say that many anime soundtracks can have similar energies or musical theory. For example, while many love the works of Joe Hisaishi and Hiroyuki Sawano, one cannot deny that many of their catalog sounds very similar, both in terms of instrumentation and music theory. This is not the case for the majority of Zankyou no Terror’s OST though, and especially not the case for ‘Von’, which stands as the crown jewel of Zankyou no Terror’s soundtrack.

Aside from ‘Von’, other notable tracks like ‘is’ and ‘seele’ further contribute to the show’s evocative mood, showcasing the OST’s ability to sustain a consistent atmosphere of loneliness, which is something I believe to be a strong indication of this anime’s high quality, given its risk of boring the listener. But regardless of the individual songs, Zankyou no Terror’s soundtrack not only embraces a distinctive Icelandic musical aesthetic but also pioneers an experimental soundscape seldom replicated in anime, leaving a lasting impression on its audience.

The title could not resist itself. IYKYK. Rahm Jethani staff writer

“THE WILL OF HUMANITY”

KONSHUU | Volume 59, RAHM Issue

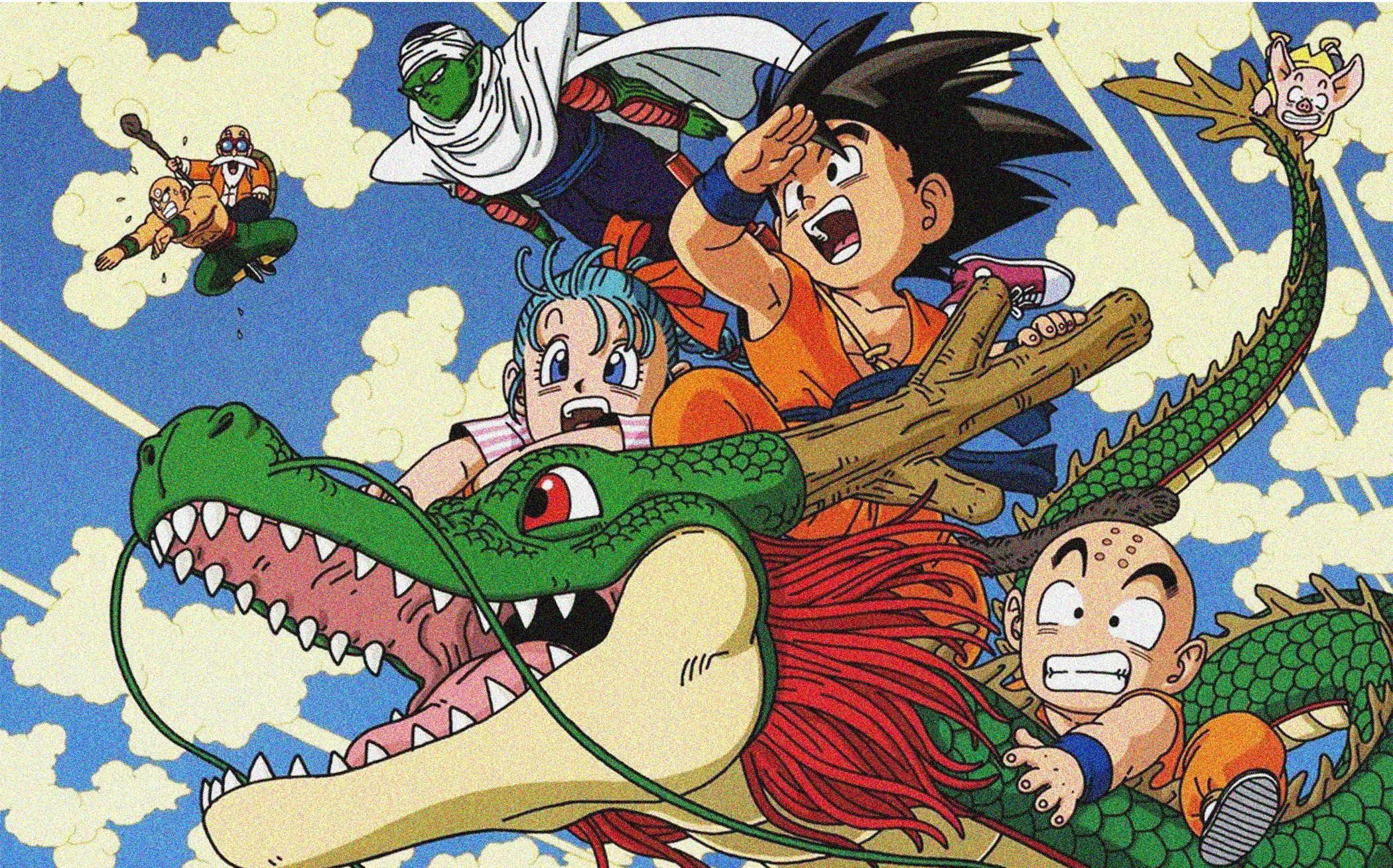

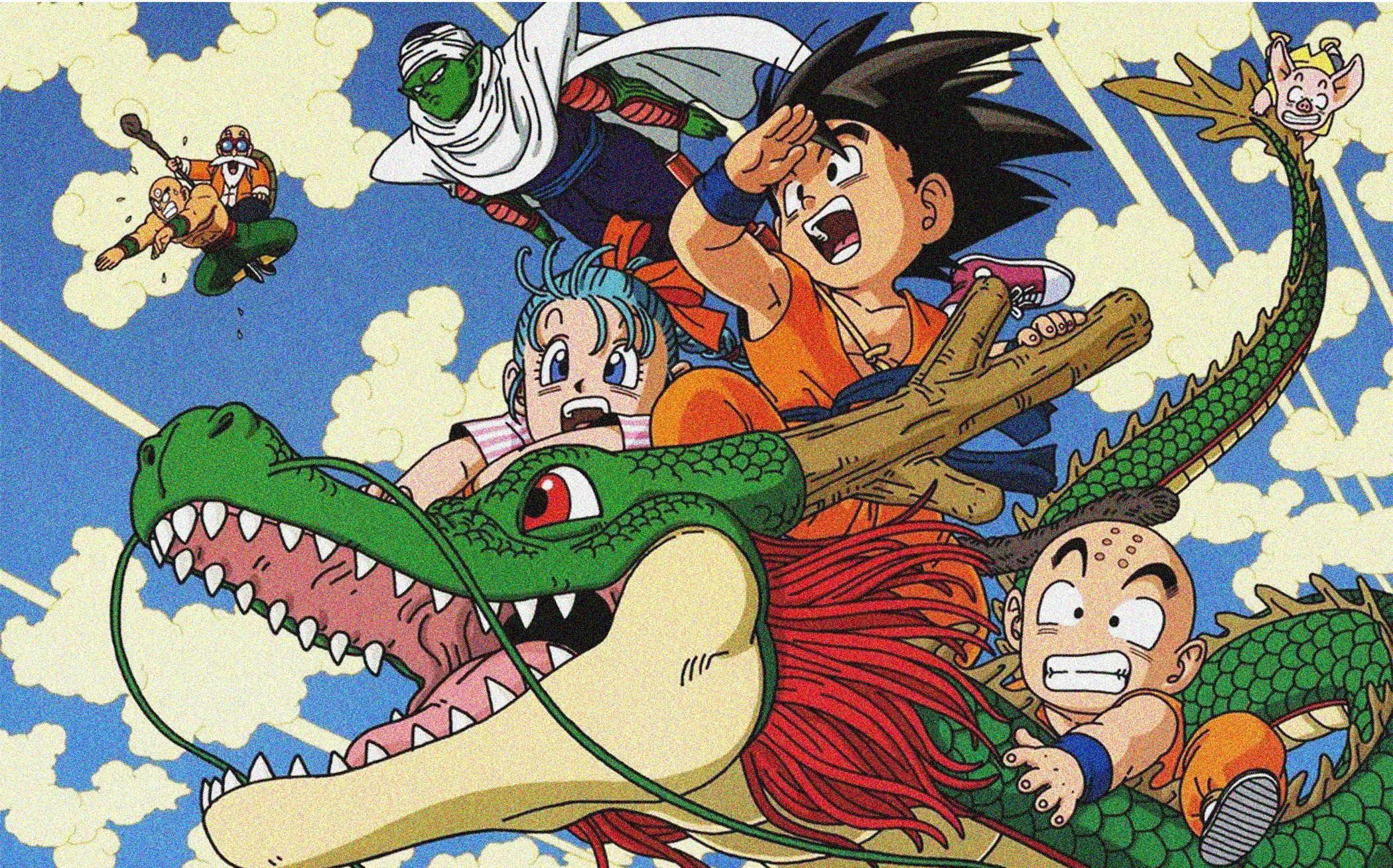

SPOILERS FOR TENGEN TOPPA GURREN LAGANN AND DRAGON BALL GT!

While admittedly a very simple archetype, characters who boast an indomitable will and an unyielding resolution to never surrender have the potential to be captivatingly portrayed in anime. They may commence their journey with a degree of naivety, gradually evolving their convictions as they navigate the complexities of their existence in the world. They might grapple with self-doubt only to undergo a transformative epiphany, emerging as staunch defenders of their principles and values. Or, in some instances, they might lack substantial character development but compensate with spectacular, visually stunning moments (as is the case with most popular shounen series nowadays). Regardless, this character trope has shown itself to be highly successful by appealing to the audience’s ideological sensibilities. However, within the realm of anime, such characters frequently encounter instances where they draw upon the collective “will of humanity” as a wellspring of power.

Take, for instance, Gurren Lagann’s grandiose “human will” themes, which hinge on Spiral Power—the ostensible force of evolution and humanity’s capacity to surmount any obstacle. Similarly, in Dragon Ball Z’s climactic battles, the Genki Dama occasionally becomes the linchpin, harnessing the energy relinquished by Earth’s populace. This concept is further magnified in Dragon Ball GT, where Goku rallies the denizens of the entire universe to manifest a Universal Genki Dama.

These moments invariably serve as climactic peaks within their respective narratives, amalgamating the characters’ ethical stances with humanity’s purported benevolent potential to illuminate rays of hope. Yet, while these instances are difficult to fault creatively, the notion of a singular “collective will” rings deeply hollow to me. Despite my inclination to appreciate these climactic moments, I find the notion of humanity’s will serving solely as an inexhaustible font of positivity rather uninspiring from a storytelling perspective. It essentially combines the power of friendship with deus ex machina—two tropes often criticized as among the laziest clichés in anime storytelling. Consequently, I am drawn more to subversive portrayals of human will, which delve deeper into thematic complexities to lay the groundwork for profound narrative climaxes.

Notable examples of anime that challenge the conventional portrayal of human will include Neon Genesis Evangelion and Babylon, among others. Evangelion explores humanity’s will through the lens of Jung’s collective unconscious, depicting a tumultuous convergence of disparate worldviews and ideologies—a chaotic yet neutral far cry from the overwhelmingly positive depiction seen in most anime. In contrast, Babylon poses the question: “What if humanity chooses wrongly?” The ensuing plot then delves into Camus’s “one true philosophical problem”—the question of suicide —and humanity’s susceptibility to manipulation. While certainly not flawless, Babylon adeptly showcases the darker underbelly of humanity’s purported limitless potential—a refreshing departure from the simplistic portrayals prevalent in mainstream anime.

Human will is often depicted as a dichotomous force, yet even this characterization oversimplifies reality. Most anime, and media in general, seldom explore the darker facets of humanity’s boundless willpower. Instances abound where morally corrupt individuals impose their beliefs on society, or where a single morally upright person makes a morally wrong misstep. However, scant are the examples where the collective will of humanity veers toward self-inflicted negativity.

Anime like Neon Genesis Evangelion and Babylon offer valuable counterpoints to the prevailing narrative of humanity’s unwavering righteousness. They challenge viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about the fragility of our moral convictions and the consequences of our choices. By delving into the murky depths of human psychology and societal dynamics, these series enrich the discourse surrounding the nature of human will, transcending the limitations of traditional storytelling tropes. In doing so, they remind us that the human experience is far more nuanced and unpredictable than the simplistic dichotomy of good versus evil. While it’s undoubtedly uplifting to witness humanity’s potential for unity and resilience, it’s equally, if not more important to explore the darker aspects of our collective will—our capacity for self-destruction, manipulation, and moral ambiguity.

(و ¬` ‿´¬) Rahm Jethani staff writer

3 CENT CORNER

1) What is your favorite anime, and why? Least favorite (if any)?

2) What are your thoughts on the Rahm Issue?

3) Was anime a mistake?

Tony T Angel Mendez, the guy that likes overused and old jokes cuz it makes for peak comedy

I’m too nice with anime and so I have a lot of favorites but just to say an answer imma go with demon slayer cuz they know how to do a final boss fight (I’m looking at you JJK). I dont have a least favorite, I just hate a lot of them. To start the list we got MHA, then Evangelion, then Oregairu, then Classroom of the Elite, then......

¿Rahm has an issue? ¿With what? ¿With who? ¿Why?

The Promised Neverland season 2. I genuinely do not know what the fuck they were thinking in making that season. You literally have anime of the year on paper and then you come out with some shitty fanfiction ahh story. Other mistakes are MHA, then Evangelion, then Oregairu, then Classroom....

Guilty always but ya’ll the soundtrack story like I be complaining

Damn is over, dictator issue this

Yes screwed we functional if we any not

KONSHUU | Volume 59, RAHM Issue

It’s not cool It’s not cool

Joey

officer Dragon Ball cause it’s cool; Elfen Lied cause it’s not cool

Joey Chao, some event officer that’s just there

Max Rothman, “Disorganized Yapper”

Tyler Wolfe, Sole TYPE-MOON Fan

Carlos Solano, Video Officer

Guilty Crown. People always be clowning on me ya’ll gotta understand soundtrack is top notch story ain’t that bad either swear people always complaining ��

Damn the Tony era over, the new CAA dictator got his own issue now, let’s see how this goes.

Gurren Lagann. After all these years, it’s still peak and with a great message. A love letter to 40 years of giant robot action.

My favorite “anime” of all time has to be Usogui. It is both the most well drawn and most grotesque looking manga I’ve ever read. Compare that to my least favorite piece of “anime” media: Umineko. Imagine walking into a restaurant and ordering an item off the menu. However, instead of delivering that steak to you, the waiter beats you to near death and tells you it’s all about the heart.

My favorite anime is Full Metal Alchemist Brotherhood. I think its a great cohesive story that explores different themes and school of thought that is executed amazingly. My least favorite is Sankarea, it touches on subject matter that is super triggering and they doesnt have even a satisfying conclusion for that kind of stuff. The writer kind of just doesnt touch on it ever again.

We need more ‘[X] Issue’ editions

Yes I think anime screwed with our heads we would be normal functional human beings we had not watched any it’s over (I swear I’m not projecting ��).

While I could yap forever, I will say no- tragedy of the commons aside, anime is still worth it

I always knew Rahm was a quirked up white boy, now we just need to see if he’s goated with the sauce.

FIRE PRESIDENT ISSUE!

No, but watching it certainly is.

No. The communities can suck but what community doesnt have crazy communities. That being said the ones that suck REALLY suck!

HOW DO YOU LIVE?

SPOILERS FOR THE BOY AND THE HERON / KIMITACHI WA DOU IKIRU KA!

After watching Hayao Miyazaki’s latest movie, The Boy and the Heron, I initially felt a bit disappointed. I had expected a somewhat fleshed out story, with more focus being on character development over the fantastical spectacle one knows to expect in a Ghibli movie. But most importantly, I also wanted to understand the depth of the philosophical questions I knew Miyazaki would insert into this movie (as he has done with all his other ones). While there were interesting characters, it felt as though their arcs were dropped very early on in favor of the aforementioned spectacle. Both plot threads and supernatural elements seemed to come and go in a much more sporadic fashion than Miyazaki’s prior movies. And, I could not pinpoint any depth that was unique to this film in particular. My disappointment was made worse by the fact that the first third of the movie handled its characterization and fantasy aspects much more concretely than the rest of the film, which incorrectly set my standards for the experience that the whole movie had to offer. However, due to my almost holistic enjoyment of Miyazaki’s films, I was troubled with my initial impressions, and I questioned both my thoughts of The Boy and the Heron, as well as its substance without comparison to other Ghibli classics. After reevaluating the film though, I gained a much deeper appreciation and love for The Boy and the Heron which helped it capture the magic Hayao Miyazaki’s work has always had on me. Furthermore, I realized that any meaningful analysis on this movie and its main character practically forces one to contend with the question (and the infinitely better Japanese movie title): how do you live?

Mahito Maki, the protagonist of The Boy and the Heron, starts off as a self-destructive boy who is unable to get over his mother’s death. He only acts as polite as he needs to around his father and foster mother, and his actions communicate grief, impassivity, and a self-imposed isolation. My favorite piece of Mahito’s early characterization is his imme-

diate attempt to distance himself from the boys at his new school by getting into a fight, followed by his self-inflicted injury afterwards to get out of school. The lack of dialogue in this section highlights his mental condition well, which was likely the goal the filmmakers had in directing these scenes in this way. It is also noteworthy that in these early parts of the film, Mahito only initiates conversations about things he wants, a stark contrast to other child protagonists of Miyazaki’s films. He possesses no humor or desire to entertain others’ whims. He is truly alone, and at this point in the movie, it would be inaccurate to say that he truly lives rather than just surviving.

The early sections of this film enhance character drama through abstract setpieces. Moments like Mahito’s dream of running through fire and resurfacing from water, the various appearances of the Gray Heron, the frogs crawling over Mahito’s body and face, and the construction of his mother melting all lend themselves to a sense of uneasiness and dread. Not knowing many of the rules of a world’s magic is very unlike Miyazaki’s other films, but in the case of The Boy and the Heron, this obscurity actually highlights the focus of these moments, that being on the feelings created

KONSHUU | Volume 59, RAHM Issue

rather than the insight they provide about the world’s rules. Many moments within the film also follow this format of abstraction highlighting feelings, so to that end, I won’t discuss them unless they are relevant (but they are universally fantastic).

Mahito’s journey into the other world marks the point where his arc begins to feel forgotten, but the experiences he goes through and the characters he interacts with in this alternate world serve to indirectly show his growth. For example, Mahito’s interactions with the alternate Kiriko almost immediately begin with him having to help her, such as with rowing the boat or cutting up the giant fish. After being so self-absorbed until this point, Mahito’s change of becoming a bit more sociable represents itself metaphorically through his bandage coming off and his scar being shown. In other words, he is still hurt and still healing, but he is able to let himself be more open through the actions he takes with others.

Mahito’s interaction with the dying pelican, which in my personal interpretation represents the world, questions the state of loss present throughout the movie. Mahito’s anger at the pelican for attacking the warawara and the pelican’s own remark that the world would not allow the pelicans to change are both ideas that shed light upon a conflicting concept: a victim feels death and loss personally, whereas the world impassively continues on. The choice of having the pelican communicate this to Mahito doubly presents the

chance for the audience to feel pity for this dying bird who had no choice, a state which Mahito himself struggles to find during their conversation. Finally, due to the bird’s death, Mahito is not able to gain peace through overcoming its philosophy, which suggests that in order to find that kind of solace, Mahito would be required to look inwards rather than blaming the world for its immemorial ways.

After entering the Delivery Room with the help of Himi, Mahito’s characterization is at its most unclear point. While his whole journey started because Natusko went missing, he doesn’t seemingly feel any attachment to her except through proxy as his father’s new wife. This is even something mentioned by the older Kiriko, which Mahito makes a point to ignore. His impersonal feelings towards Natsuko even make themselves clear when he first tries to wake her up,

as shown through his formal speech and Natsuko’s identity as just his dad’s wife in his mind. And, when speaking to her this way, Mahito’s words have no effect on Natsuko, instead just harmfully agitating the magic of the stone. Only when Mahito realizes and vocalizes his love for Natsuko as a true mother figure does she wake up. While there is no obvious development towards Mahito’s revelation, which is one critique I still have with this film considering its importance, the revelatory moment is represented beautifully through Mahito’s struggle against the storm of paper, and through Himi’s aid (considering that she is another version of his birth mother, thereby metaphorically helping him come to terms with his new mother). Another aspect of this scene which I found to be interesting is the location of the Delivery Room itself, as Natsuko was not apparently in the late stages of pregnancy yet. Therefore, the Delivery Room itself seems to be metaphorical, perhaps hinting that it is a place of rebirth. The symbolism of birth and rebirth is also present within the existence of the warawara, so its presence here seems intentional, too.

Near the end of the film, Mahito receives another piece of fantastic characterization, when the Great Uncle asks Mahito to take over his role of balancing the worlds. If one is to interpret Mahito’s scar metaphorically, then Mahito’s mention of it communicates the large extent of his growth throughout the film. He says his scar makes him imperfect and therefore unable to create perfect worlds, to which the Great Uncle agrees. This could represent Mahito’s acceptance of his pain, and the acknowledgment that his grief will continue to affect his life. But, Mahito also mentions the roles Himi, Natsuko, and the Gray Heron all played in being his friends, and helping him remember how it feels to want to live. I believe that this is how Hayao Miyazaki answers the question of ‘how do you live?’: by maturely accepting the life you have, and by maintaining the positive company of friends and family, you are able to find peace and truly live. This belief that Mahito comes to understand shapes his growth after the events of the film, too, as shown through the quick scene of his family moving back to Tokyo two years later. I love the small detail of Mahito not wearing his hat anymore, now showing more of his face to his family and to the world.

While I have my complaints on certain aspects of The Boy and the Heron, I have found myself becoming more and more attached to its style and presentation of themes as time continues to pass. While The Boy and the Heron doesn’t have the most unique message, its use of abstraction, thoughtful characterization, one of Joe Hisaishi’s best soundtracks, and Studio Ghibli’s trademark brand of magic have merged to create a poignant work of art that stands tall amongst the best of Hayao Miyazaki’s work.

Worth the wait. Rahm Jethani staff writer

THE WORLD OF SAITOU

SPOILERS FOR LITTLE BUSTERS!, LITTLE BUSTERS! REFRAIN, AND LITTLE BUSTERS! SEKAI NO SAITOU WA ORE GA MAMORU!

As an avid Key/Visual Arts fan, I have seen quite a large amount of their catalog. My watching patterns with Key’s anime often consists of watching a show all the way through, then saying goodbye through each series’ respective OVAs. I usually do this to find some sense of closure from the OVAs, which, in Key’s case, are usually released after the anime finished airing. While this closure doesn’t always come, I have consistently maintained this pattern with my viewings of Angel Beats!, Charlotte, and Planetarian. However, I never got around to watching the OVA of Little Busters! until very recently. Little Busters! and its sequels, Refrain and EX, were the first Key anime that I ever watched, so I was confused as to why I’d never even heard of the existence of Little Busters! Sekai no Saitou wa Ore ga Mamoru!

Having been released after the original series but before Refrain, Sekai no Saitou wa Ore ga Mamoru! was made to be watched without the knowledge that the characters were living in an infinitely repeating, false world. As such, the OVA follows the characteristically silly antics of the Little Busters, while having no relevance in terms of progressing the plot or character progression. At a glance, one could reductively describe it as pointless filler. And, only at a glance, this description would absolutely be true. But, Sekai no Saitou wa Ore ga Mamoru! is more than meets the eye, and its interpretation of Little Busters!’s themes is both simple and retroactively beautiful.

Having watched Little Busters! Refrain beforehand, it was clear that there were a lot of similarities between Mask the Saitou’s authoritative strength in this OVA, and Kyousuke’s cunning control in Refrain. This should be obvious given how they are the same person, but while I think these parallels are intentional, there is a notable difference that should lead to different analyses of these characters. While they each dominate their own environment (Saitou with the school rankings and Kyousuke with the reality of the world), Saitou is operating within the rules of the world. His success, as opposed to Kyousuke’s complete control, is almost entirely determined by what weapons the crowd of students gives him or his opponent. In this way, Mask the Saitou’s “power” is completely dependent on his classmates, and is also essentially random because of this. So then, you might ask, how does he keep winning his fights? While the audience isn’t shown any of his battles, Saitou announces his pow-

KONSHUU | Volume 59, RAHM Issue

er comes from his determination to “protect the world of Saitou”. This draws comparison to Kyousuke’s determination to protect his friends, which manifested into the power to create a false world. Just like Kyousuke, Mask the Saitou’s will seems to have an actual effect on the world.

In the final fight, between Riki and Saitou, it appears as though Riki will easily be decimated. However, just as Saitou is about to land an attack, the voice of Komari can be heard. She walks through the fight, along with Rin, in a comedic moment while reading the story of “Run, Melos!” out loud. And, as the literary romantic Kyousuke hears the dramatic conclusion of the story beneath the mask, he begins to cry and says he isn’t able to hit Riki. Mask the Saitou then forfeits the match, and Riki becomes the school’s battle-sequence champion. As the sun sets, Kyousuke hands Riki the mask, telling him that he is now the new “Mask the Saitou”, and that it is his responsibility to protect the world of Saitou.

This ending is reminiscent of the ending of Refrain, where Kyousuke relinquishes ownership of his false reality after he observes the strength of Riki’s will, and the world disappears (comparatively in this OVA, Saitou relinquishes ownership of his mask after he observes human compassion, and the mask literally disappears from the rest of the series). While Riki didn’t need to do anything in the fight, his role as the new Mask the Saitou raises a question as to its significance: what does it mean to protect the world of Saitou?

In my mind, Mask the Saitou’s nature as a transferable, literal mask suggests that rather than literally being Kyousuke’s false world, the world of Saitou is instead an idea that can be “worn” by anyone. And, the idea of the world of Saitou is most likely the same idea that gave Kyousuke’s version of Mask the Saitou power: the reliance on others for strength, and the determination to protect something apart from oneself. This conclusion thematically reinforces the events leading up to Riki’s escape from Kyousuke’s world. At the end of Refrain, Riki had to prove to Kyousuke both his own strength, founded upon the lessons he had learned from others, and his determination to protect Rin no matter what happened. In this way, Riki at the end of Refrain ideologically embodied his role as Mask the Saitou. If one wanted to continue this logic, they could say that once this had happened, Riki’s

“If

desire for his friends to live was transposed upon the real world, just like how Kyousuke’s Mask the Saitou commanded power within his fictional one.

Interspersed with the main plot of Mask the Saitou, the Little Busters! OVA also features a comedic subplot about Kurugaya purposefully giving misleading advice to the other members of the Little Busters in order to teach them actual life lessons. I could superimpose deeper meanings onto this section of Sekai no Saitou wa Ore ga Mamoru!, but in truth they’re mainly played for laughs, so I won’t dive into them too much. One small detail worth noting, though, is that the position of Kurugaya and the other Little Busters as side characters makes their comedic antics and subsequent character growth a comforting story element. To know that these characters would be able to successfully live their lives beyond their time spent as ‘Little Busters’ does provide a small bit of closure for series fans, especially given the OVA’s main focus being on Riki and Kyousuke.

As a final goodbye to Little Busters!, Sekai no Saitou wa Ore ga Mamoru! is very aware of its strongest themes, and displays them proudly. While it misses the mark in terms of its narrative cohesion with the rest of the Little Busters! series, Sekai no Saitou wa Ore ga Mamoru! is one of the most effective final OVAs of any of the Key anime released so far.

you don’t hit me, then I can’t bring myself to return your embrace. Now, hit me!” Rahm Jethani staff writer

REMEMBERING THE LEGEND

SPOILERS FOR LEGEND OF THE GALACTIC HEROES!

If your life was to suddenly end, how do you think you would be remembered? This is, in many ways, a doomed question, but let’s try to answer it anyway. In all likelihood, those who knew and loved you would feel deeply saddened by the loss. If you were fortunate enough to be part of a large or tightknit social group, your absence would shake their emotional foundation quite hard, no matter how significant your individual presence might have been. Your beliefs, mannerisms, and behaviors would live on well beyond your physical death. Yet in truth, as the years would pass, you would be remembered less and less. Those who heard your name would bolster the “idea of you” to make up for their faltering memory, but the impossibly intricate “you that lived” would disappear from many of their minds, merging with their fictional and idealized version of you. Posthumous idealization isn’t necessarily a tragic thing, as every death invites it to some extent, regardless of circumstances. Idealizing deceased loved ones can help people cope with the pain of loss or guilt, for example. Even a person’s worst deeds can become rose-tinted after death or disappearance.

Contending with this concept can be extremely difficult, and can often lead to nihilistic outlooks on the flawed nature of human memory. After all, how does one even come close to answering the question of how they will be remembered? It is a question that’s almost impossible for most people to answer confidently, and might lead to hopeless paranoia and dread in some cases. However, there is an OVA series that strongly rejects nihilism, while also, miraculously, depicting loss and legacy from an impersonal viewpoint. This show is able to treat the nuanced subject of legacy with the kind of philosophical dignity it deserves. The anime in question is the 1988 cult classic, Legend of the Galactic Heroes.

On the side of the democratic Free Planets Alliance, Admiral Yang Wenli represents the commonplace, righteous soldier. He’s known for being a militaristic genius with a kind and thoughtful heart, proudly upholding the practices of democracy even in situations where that behavior would be disadvantageous. His leadership in battle led the Alliance to numerous achievements, as his fleet never lost a single battle. To the common supporter of democracy, “Miracle Yang” was living proof that their political philosophy was correct.

But then, Admiral Yang Wenli “the Magician” died.

Yang’s adopted child Julian Minci and his wife Frederica Greenhill remembered him quite differently than the public. This is natural, as they were very close, and his family had had the chance to observe all of Yang’s habits and quirks. For example, Julian and Yang talked at length about the irony of war having “heroes”, and the simple joy of studying history rather than being at the forefront of it. Furthermore,

KONSHUU | Volume 59, RAHM Issue

Julian also realized how much Yang was unable to take care of himself, often resorting to sleeping or drinking on the job. In Julian’s mind, Yang Wenli was much more of a man, full of flaws and humor and unrealized dreams, than a myth, representing an entire political belief system. Likewise, Frederica also observed Yang’s various idiosyncrasies. To Frederica, Yang was her childhood hero, and even though they were only married for two years, she came to love him for the man he was. She knew of his contemplative and indecisive nature, and comforted him in a way that history would never remember.

And yet, everyone grieved for Admiral Yang Wenli.

On the side of the autocratic Galactic Empire, Emperor Reinhard von Lohengramm represents the ideal of the rare, morally good dictator. He’s known for being a charismatic leader with a just and fierce mind, standing by and improving the system of autocracy without ever compromising on his morals to lead with love rather than fear. His takeover of the Galactic Empire led to numerous social advancements, and made many people on the losing side of the Free Planets Alliance submit to the Empire due to Reinhard’s positive reputation. To his subjects and enemies, Reinhard “the Golden Lion” was living proof of the goodness that came from properly exercised dictatorship.

But then, Emperor Reinhard von Lohengramm died.

Just like in Yang’s case, those close to Reinhard remembered him quite differently than the public, such as the Empire’s Fleet and High Admirals, and his wife Hildegard von Mariendorf. This is similarly natural, due to their closeness and frequent interaction allowing for a more developed reading of Reinhard the man. The Fleet and High Admirals saw both his regrets and moral decisions weigh heavily on him, and saw a glimpse into his conflicted heart. They knew that, for example, Reinhard had never recovered from the death of his best friend Siegfried Kircheis at the hands of an assassination attempt that had instead been meant for him. They knew that Reinhard was fighting through the pain of his sister isolating herself on a far-off planet. Likewise, Hildegard also saw a different side of the New Empire’s dictator.

She saw a man whose lack of common life experiences manifested into raw outbursts, such as exhibiting nervous avoidance towards romance and throwing wine glasses in rage.

And yet, everyone grieved for Emperor Reinhard von Lohengramm.

Legend of the Galactic Heroes presents the idea that the two versions of a person, “the idea of the person” and “the person that lived”, exist in harmony with each other. As a result, it is impossible for one person to fully see the ways in which people would remember them. However, rather than giving in to despair over this impossibility, Legend of the Galactic Heroes suggests that how these different versions are remembered is not what matters at the end of the day. Rather, the importance lies instead with how both versions affect the lives of the people who knew that person, no matter which was considered “authentic” or not. Although there would likely be countless others with as much universal presence as Reinhard von Lohengramm and Yang Wenli, it would never erase these mens’ individual impacts on the lives of the people who knew them, and the people who knew those people, and so on. Legend of the Galactic Heroes tells us that the memory of a person will never be forgotten, regardless of how it is interpreted by and through others. In this way, one continues to live through history, influencing peoples’ lives until the end of the universe.

They say every person dies two deaths… Rahm Jethani staff writer

3 CENT CORNER

Nicholas Wonosaputra, “Annie May’s Talent Manager”

Erik Nelson, Japanese correspondent

1) What is your favorite anime, and why? Least favorite (if any)?

Code Geass simply because I still have yet to find something else that my brain can compute more efficiently. Re:Zero S1 is my least favorite because many of its storytelling decisions frustrate me, especially when there’re specific elements that I like a lot

2) What are your thoughts on the Rahm Issue?

Absolute banger 11/10 I totally have seen the finished product before giving this response

x

and gon’s relationship is painfully relatable

3) Was anime a mistake?

Is human expression a mistake? I liken it to a happy little accident.

Your mom was a mistake

Yes, instead

KONSHUU | Volume 59, RAHM Issue

Hunter

hunter. Killua

Rahm

My favorite Monogatari, compelling story to a whole to its favorite because essence one of

Unadulterated

Felix Levy, ball knower

Jacob Malach

Lionel Verano, that one dude who really likes Re:Zero

Anje Chimura, #1 anime fan favorite show is Monogatari, because it is a compelling coming of age that brings its dynamics whole new level thanks artistic merits. My least favorite is Evangelion 3.0+1.0 because it tramples the essence of the original, also of my favorite shows ever

Favorite is attack on titan, least favorite is attack on titan because it is the only anime I’ve watched

Unadulterated kino

I give it my official seal of approval and endorse everything said within it

Most fav? Re:Zero. It’s the anime that got me into anime. I love the writing and plot. Emilia ftw Least fav? Your lie in April. mid anime tbh. doesn’t strike a note with me

I like Spirited Away because it’s really pretty and the aesthetics tie in really well with the storytelling. I also really like Neon Genesis Evangelion for its profound portrayal of human consciousness :)

Yes, just watch ball instead or something

No but you should need a license in order to watch it

It’s great! It’s prob the best thing in Konshuu so far tbh

There are no mistakes. only happy accidents... except for Anime, which ya is a mistake

Peak???

No I love anime!

FUTURE REDEEMED IS PEAK XENOBLADE

SPOILERS FOR XENOBLADE CHRONICLES 3 AND XENOBLADE CHRONICLES

3: FUTURE REDEEMED!

The Xenoblade Chronicles series, as well as the entire Xeno series for that matter, is one that is very close to my heart. Its explorations of what it means to live, how to adhere to what you believe, and how to overcome overwhelming odds have deeply affected its many players across the years. Future Redeemed, Xenoblade Chronicles 3’s final and largest piece of downloadable story content, is a beautiful culmination of what the series has come to represent. Miraculously, it strikes the perfect balance of being a love letter to previous installments of Xenoblade Chronicles 1 and 2 while honoring the themes of Xenoblade Chronicles 3, and it is also able to bring everything together in a hopeful look to the future. And, being a Xenoblade game, of course it had to be hype as all hell.

In terms of action-JRPGs, Xenoblade has always had an extremely unique combat system, closer to that of an MMO than to a portable Nintendo game. While Xenoblade Chronicles 3 mixed the best combat elements from 1 and 2, Future Redeemed goes a step further. Like Xenoblade Chronicles 2’s prequel DLC, Torna – The Golden Country, Future Redeemed uses a “community” system, where players are forced to interact with the growing Colony 9 in order to unlock elements of progression. However, thanks to the feedback the developers received on Torna, Future Redeemed’s community system retains all the benefits while getting rid of nearly all the drawbacks. In essence, Future Redeemed uses positive reinforcement to motivate players to engage with its community aspect. Exploration means that you can get more items to unlock more moves to defeat bigger monsters to receive bigger rewards from the community system.

Nothing in this loop feels insignificant either; every gameplay feature here feeds into multiple other ones, making engagement with the community and the world a joy rather than a requirement. With Future Redeemed, a player is now able to feel genuine happiness about bringing more life to Colony 9, rather than an exhausted relief about meeting the minimum requirements for taking on a main story quest. Combat is also expanded upon in FR, with more customizability and more creative ways being offered to take down certain encounters. Xenoblade combat has never felt this good.

The characters are great in Future Redeemed, too. Of course we have the returning characters of Shulk and Rex, whose presences are still able to create inspiration in many forms. Both characters dealing with the fact that they are fathers is a nice moment of bonding, with their advice offered to each other showcasing the well-rounded people they’ve become.

KONSHUU | Volume 59, RAHM Issue

This is a level of fanservice that I’m willing to tolerate, because these moments build meaningfully upon previous ones rather than just calling back. Shulk’s wistful “to you” at Colony 9 hits, man. The other standout returning character is N, who gets a lot more development in this prequel than I was expecting. We see his destruction of the old City, and we see him wrestle with his selfish desire for eternity against his feelings of immeasurable guilt. His conversation with Ghondor before the old City’s destruction and with Matthew before the final showdown against Alpha show the final embers of N’s human consciousness rebelling against the empty promise of Mobius. The writers of this story handled this moment perfectly, creating sympathy for such a deeply despicable character.

The new characters are brilliant too, albeit slightly archetypical. Most of the new cast work well because of their relationship to already existing characters. For example, Matthew is interesting because of how his personality subverts the audience’s expectations of who Xenoblade Chronicles 3’s Noah is supposed to be descended from. Having Matthew be a hot-headed idiot pugilist with a big heart, in comparison to Noah being a soft-spoken and deeply serious sword-wielding musician creates a very interesting dynamic in a metatextual sense. Likewise, A’s relationship to Alvis benefits her in a similar way, with her more human qualities being the result of Shulk and his friends’ humanity rubbing off on Alvis. Glimmer and Nikol unfortunately get very little development, with the bulk of it just playing off of their relationship with their parents.

What truly shines above all else in Future Redeemed, though, is the fulfillment of philosophical concepts and journeys that have taken place across the series, as well as the moments of hype spread along to help this aspect resonate with players. The concept from Xenoblade Chronicles 3 of Origin being a collective-unconscious-powered supercomputer is already fascinating, but the ways this idea is built upon in FR creates naturally stemming consequences of their world birthed between the two others. Despite it being a philosophical battle between Alpha’s and Mobius’ solutions, neither is perfect. Having grappled with the latter in the base game, addressing the former in this prequel also provides an opportunity for the Xenoblade franchise to reflect on itself, due to both Alpha and the Xenoblade series intending to move on to a wholly new future. This is why the multiple references to Xenosaga, while being a completely wild direction, are cohesive to the journey of the Xenoblade series. The solution that both the protagonists of Xenoblade Chronicles 3 and the writers of the series face is that no matter what direction you go, life is about continually moving forward without disregarding the past.

I can’t wait for the future of this series. Connecting the new world of post-Xenoblade-Chronicles-3 with Xenosaga is a bold move, but judging from how the philosophy of the Xenoblade series has always been preserved throughout its runtime, I have no doubt that the next installment will be spectacular.

I’ve seen that look before… Rahm Jethani staff writer

AND THE SOUND OF AMPLIFIED YOUTH

KONSHUU | Volume 59, RAHM Issue

SPOILERS FOR K-ON! AND K-ON!!

K-ON!

The fundamental idea that the slice-of-life genre is built upon is that of capturing the experience of some kind of daily life, and then projecting unifying themes across them. While the approach to telling these kinds of stories has generally remained the same over the years, the number of ways a series is able to depict this kind of “daily life” is, of course, quite varied. Although, in order to retain the attention of their audience, slice-of-life shows often place a large emphasis on comedy and character drama, which has the effect of these kinds of stories bearing repetitive narrative arcs with simplistic and clichéd characters. While words like “repetitive”, “simplistic”, and “clichéd” have accrued a negative reputation for themselves within the realm of media discussion, it’s important to realize that the slice-of-life genre almost demands this level of constancy. In this way, “slice-of-life” is more than a genre; it’s a mood, an atmosphere, and also an aesthetic. And, these traits almost always necessitate that their presentation be relaxing. Due to this, relaxation in slice-of-life is often achieved through the structure’s inherent familiarity rather than the events within the structure itself. This is to say that beyond shallow perception, there is a potential for deep, rich slice-of-life storytelling.

When I first entered high school, simply put, I did not fit in. As the new students began joining school clubs, I was also quickly pressured to do so but unfortunately, I did not have any particular passions. School life then moved by too fast, and as a result, I was unable to join any club and went through the entirety of high school feeling left out, not a part of any social group or circle. This then motivated me, as soon as I entered college, to join as many clubs as possible. I could not count on my fingers the amount of clubs I successfully joined during my first semester, but even then, my passions did not have any particular direction. And so, as my attendances in most of these clubs gradually waned, I was ultimately made to realize through my new close friends that “passion” did not solely facilitate me living the “best version of school life”. Rather, it was the expressive, thrilling, exciting, and beautifully fun experiences that I shared with my new friends that came to define my “best version of school life”.

To those who know the premise of the anime series K-On!, this anecdote should sound very similar to the show’s introductory episodes (as well as to whole of The Tatami Galaxy, but I’ve already written an article about that), and while stories of this type are general enough to resonate with a wide audience, one must also acknowledge that people often have a propensity to connect with the slice-of-life premise simply due to the comparatively small level of abstraction as compared to other genres. So considering both this fact and my own predisposition to connect to the anime’s central thematic axis, it is no wonder that as soon as I started watching, K-On! quickly drew me in.

But, while the initial hook of K-On! meets the qualities of what I find to be “interesting,” neither it nor any sense of relatability wholly kept me from watching the show. Rather, what kept me watching until the very end of both seasons were ironically several storytelling aspects that I have, in the past, often dismissed as being “uninteresting.” When I say “uninteresting,” you might assume that I’m referring to lazy narrative clichés, poor writing, or something just as equally and subjectively prone to a viewer’s worst kinds of judgments, but you would be wrong. No, I had initially brushed off many of the best aspects that K-On! proudly touts with the term “uninteresting” exactly because I truly believed this anime was just as fantastic as its reputation had made it out to be. Before I had even watched its first episode, my preconception of K-On! was that it was a shining example of the best kind of anime from its era, produced by one of the most highly acclaimed animation studios of its era, with some

Functionally, this is also about Umineko. Rahm Jethani staff writer

of the best “high school girl band” anime music ever in the height of the “high school girl band” anime era. I had grown up with K-On! always being in my peripheral anime-sphere vision. And every person I knew who had watched the anime had told me that it was awesome. And so, because of the aforementioned “shallow perception” that one could develop towards slice-of-life stories, and this collectively perfect image that made up the animation entity known as “K-On!,” I had subconsciously condemned it as “uninteresting;” the epitome of the “it’s not for me” sentiment.

As a quick side note, a “perfect story” does not exist; there is no objective way to create perfection in a narrative work. Some have brought up ideas of a perfect story being self-contained or having the most satisfying plot points, but these definitions don’t have any quantifiable way of being proven correct either. Final Fantasy XV is an incoherently cluttered mess of a video game, with prequel movie, a prequel anime, several pieces of downloadable content most commonly in but not limited to sidestory episodes (one of which being an epilogue that fundamentally changes your understanding of the antagonist unless you already watched a different prequel anime), and finally an epilogue novel that rewrites the original ending of the game. The way to experience the story of Final Fantasy XV is objectively not self-contained, and yet I personally think it is a better story than something completely self-contained like Code Geass: Shikkoku no Renya, for example, which is a crime against all that is good in the world, and can burn forgotten in a dumpster fire. This is all to say that perfection is subjective, and as one’s views grow, change, and develop, so too do their views on what makes a good story.

With this in mind, at some point in time, after I had seen and learned more of the world and of media, my tolerance and viewpoint on the platonic idea of “perfection” had changed to where I was willing to watch K-On! on the suggestion of a friend. When this friend suggested K-On!, it wasn’t like it was an out-of-the-blue kind of thing, either. Before this, I was also recommended classics that I had never seen, such as Neon Genesis Evangelion, Tengen Toppa Gurren Lagann, and Dragon Ball, just to name a few. While I took K-On! as simply another one of these, something had profoundly changed within me after watching those other classic anime that had removed “uninteresting perfection” as an obstacle for viewing media (a subject best left for a different article).

As I started my journey through the first few episodes of K-On!, I slowly became familiar and immersed in the high-quality aspects of it that one would come to expect, namely the soundtrack, artwork, pacing, writing, and atmosphere. But as I became more accustomed to the anime’s structure in these early episodes, I became aware of a quietly remarkable feature that carries into each episode for the entire series. This feature is K-On!’s ability to create an interesting and entertaining episode with only a small amount of things actually happening in them. Drastically simplifying this episodic structure, it wouldn’t be inaccurate to say that very little of actual consequence happens in most episodes. While this literary tool is fairly typical in slice-of-life shows as a whole, K-On! manages to stand out. This is especially notable due to the timeframes that the two seasons occupy, with the first season spanning two years and the second season spanning one year. Also of note, the second season is twice as long as the first despite taking up half the time chronologically. Even though time might be tempted to inflate and stretch in a story paced this way, K-On!’s use of memorable and charming characters and events serve as anchors, and do a great job of grounding the viewer into the daily lives of these girls going through their high school lives.

KONSHUU | Volume 59, RAHM Issue

The way that K-On! is directed also dedicates its efforts into showing how the main characters perceive that high school experience. Many anime of this type (and slice-of-life shows in general) tend to show their characters’ inner thoughts and feelings through a somewhat contrived or non-immersive method, such as characters having inner-dialogue soliloquies or addressing the viewer directly to communicate themselves. While this type of presentation isn’t bad by any means, I find that lighthearted media whose characters communicate to the viewer directly or indirectly have the risk of feeling disingenuous, as though the writers either don’t trust their viewers’ intelligence, or lack the ability to effectively pull off the “show, don’t tell” writing sensibility. In comparison, I think K-On! bypasses this pitfall in two ways. Firstly, there is almost no inner dialogue in the entirety of the 39 episodes, and if there ever is, its usage serves as a specific joke rather than a comedic or narrative crutch. By having the characters voice themselves audibly in their high school environment, most often to their classmates and friends, every instance of a character’s development feels natural and built up to. For this to be done so effectively in an anime that contains barely any tension is a testament to how thoughtful the masterful writing and direction is. The second way K-On! bypasses the feeling of disingenuous presentation is its very conscious treatment of time. In many slice-of-life shows, the issue of time is often trivial, with all involved characters being able to speak in a non-conscious void of time (whether this be inner-dialogue or addressing the audience). Any conscious attention drawn to time, then, is often left feeling like a plot contrivance rather than a natural force, both in terms of the feel of pacing and in terms of audience perception. However, due to K-On!’s slow yet constant sense of time progression, there are many instances where main characters involved in pivotal plot points are not given time to show the audience their feelings and thoughts. Because of this direction choice, the viewer gets a more accurate sense of what it is to live a daily life; you don’t always know what everyone else is thinking. Even if you were to try and observe everyone you knew, you would inevitably neglect certain aspects of that attention. It is an impossible task. We all live with biased perception, after all. But, even as K-On! masterfully portrays this concept, it always does so in a way that strengthens the time given to the characters who are portrayed, instead of weakening the time with those who are not. Decisions like

this, as well as nearly every directorial decision in this anime, are used to lighten the mood, help the viewer relax, and provide an authentic and cozy experience. All of this is shown honestly to the audience in the first few episodes, and highlights an extremely important element of K-On!: it trusts you to understand. K-On! trusts you to enjoy it, and to love it.

Among the many strengths of K-On!, one that I never doubted my potential enjoyment of was its cast of dynamic yet cohesive characters. They each broadly fit an already established character archetype, but do so in a way that compliments other characters and fits the anime’s excuses to get everyone into numerous hijinks. Ritsu is the impulsive and brash leader, Mio is the nervous/shy and serious foil to Ritsu (often serving as the tsukkomi to Ritsu’s boke), Mugi is the kind and pampering mother of the group, Yui is the charming yet airheaded child-figure, and Azusa fills Mio’s serious role as Mio starts lightening up throughout the series. These characters go through their own journeys of self-discovery and growth through their interactions with the other band members, but their personalities largely remain the exact same at the end as they were at the beginning. I often praise anime characters for being subversive, as I believe that is one of the best ways to keep things interesting as a viewer, but K-On! reminded me of the strength that comes with well-executed tropes. The consistency and reliability of each character’s personality, while dually serving the aesthetic of comfort and coziness of the show’s aesthetic, also made understanding their motivations and actions more accessible as a viewer. Furthermore, the anime’s focus on comedy was also able to be used in order to accentuate the differences of each of its different cast members. As a result, if these characters had had more layers, or if they had been less archetypal, I genuinely think that the experience of watching K-On! would suffer. This is not to say that the characters have no depth or complexity at all, but rather that along with their unique qualities, they also still fit snugly into pre-established archetypes while endearing a viewer to them. By crafting this kind of balance, with by-the-book characters and moments of idiosyncratic character bonding, the show writers create a rare experience that still meaningfully engages the audience through innocent and wholehearted entertainment. This is one of the many ways in which K-On! embodies the essence of youth; a deeply methodical presentation of simple-seeming constants.

Going more into the time dedicated to character bonding (and to character interaction overall), it’s clear that this is where K-On!’s presentation of youth is the most strong. Every instance of people talking to each other in the anime serves a purpose, whether it be to diegetically communicate information to the viewer, help move the plot along, or create various moments of emotion or humor. Despite each interaction clearly serving an identifiable purpose, in practice nothing in this regard is executed in a heavy-handed fashion; again K-On! takes great care to have its meticulousness become invisible. This is especially impressive in scenes consisting mostly of pure humor, which is to say, a majority of K-On!’s scenes. The dialogue between the characters maintains a comfortable and natural pacing, with the punchlines and gags serving as energetic high points for the less energetic and simmering buildups of daily conversations. Eventually, a viewer may subconsciously get used to this structure, as it becomes the most common way the anime greets them. Therefore, the frequently occurring changes in conversational dynamics both engage the audience while furthering K-On!’s focus on its lively characters.

In both seasons of K-On!, its plot works from the shadows. You hardly notice the methodical structure of carefully placed story moments unless you’re looking for them, or unless noticing these narrative moments is an intentional decision by the showrunners. Oftentimes, as K-On! is quite episodic in nature, the story in each episode has ample room to breathe and showcase the many sides of its characters. As stated before, this process is often done through innocent yet wholehearted humor, which is always interwoven with the plot of any given episode to endear the viewer to many of the directions K-On! takes them. And, for a third time, much of the magic in this aspect of K-On! shines due to how unnoticeable it makes itself. Standout examples come from the multi-episode mini-arcs focusing on Ho-kago Tea Time going on summer trips, going to a music festival, and preparing for their final school festival. In these episodes, humor is mixed with meaningful character moments that give insight to their motivations and history. Furthermore, the tone of each episode is flexible enough to vary from a bubbly whimsicality to a surprisingly genuine sadness, while supporting the various plot points along the way.

KONSHUU | Volume 59, RAHM Issue

While it isn’t always done, the times when K-On! chooses to actively use continuity are thoughtful as well, used to emphasize different aspects of its plot. An example is during the music festival mini-arc, which has an episode focusing on the entirety of the Ho-kago Tea Time band members. They have their own set of varied shenanigans and antics, and moments of introspectivity that serve as some of the highlights to the anime, at least in my opinion. The following episode, though, shifts its focus to some time in the near future, with strictly Azusa as the focal point. The choice to depict the next chronological point of the story this way, with a recognizable shift in focal emphasis, can make the observations from Azusa in this episode feel extremely personal to a viewer. When she thinks about her busy friends who have just come back from the festival, when she is shown to feel left out, and when she is shown to hang out with friends other than the Ho-kago members, these are points that are given to the viewer to digest for themself. As the ideas in K-On! can be both broadly interpreted and applied to many peoples’ lives, these kinds of plot points scattered throughout the entirety of the anime facilitate a conscious awareness of one’s own life. I find K-On!’s presentation of this idea to be successful, due to it conversing with an entity separate from just a “viewer” or even as a “person operating off of the same social understanding slice-of-life shows are built on.” People are fundamentally being talked to by K-On! as just “people,” which as basic as it sounds, is a level of respect many slice-of-life anime fail to demonstrate. After all, the less present narrative abstraction is, the more likely an audience will buy into the narrative itself.

As K-On! continues, and especially in the second season, all of its meticulously crafted aspects begin to emphasize time, as the main cast bar Azusa are now seniors who are bound to graduate at the end of the year. While whimsy and episodic plots centered around humor are still the bread and butter of the anime, there are many more occasions compared to the first season that emphasize a longing for things to remain the same. There are more moments of introspection, moments focusing on final exams and final performances, and moments that will now actually make an audience sob. In order for this transition to have been made, the many previously hidden aspects of K-On! now no longer hide themselves. The episodic plots become more noticeable due

to it being a constant in the midst of the social and schedule changes of the main characters. The masterful character moments begin to incorporate more sentimentality into the cheerfulness (an excellent example being the end of season 2’s episode 20), and the characters themselves become more busy and less able to do the things they used to with their band members. Practice becomes more infrequent, people’s constant procrastinations become more stressful, and time continues to slip painfully by. I am conflicted on how to interpret the tonal shift in K-On!’s second season. On one hand, as a terminal VisualArts/Key fan, sentimentality and tear-jerkers are what I’ve come to judge slice-of-life anime endings by, and K-On!! builds up to this state much better than others of its type. On the other hand, sentimentality has a very palpable risk of overpowering the balance of a show, especially one not built to handle such a change. I’ve seen many examples of shows that use the golden syrup of sentimentality without realizing how strong it is, and the end result becomes an ending that feels both unrewarding as an invested viewer and unfulfilling as a person seeking meaningful art. After seeing it through to the end, my belief is that K-On!! ends with a measured balance of sentimentality when looking at how it affects the show’s other aspects. Due to not abandoning its strengths in favor of any kind of overdrawn emotionalism, K-On!! instead shifts its focus to use its strengths to emphasize the aspect of limited time. This technique works because the aspect of time was not only given a whole season to be developed, but was also a natural consequence of the environment the anime was set in. A thematic conclusion to fictionalized high school character journeys in media, especially in Japan’s three-year system, lends itself well to lining up with graduation. As such, K-On!!’s direction doesn’t feel out of place, and instead acts as more of a foil to compare and contrast with the first season. In order to discuss why the ending of K-On!! means so much to me, though, I need to jump back to the concept of “slice-of-life.”

The slice-of-life genre is philosophically incomplete as a narrative structure; it works based on a shared communal consensus of how the real world operates in order for a viewer to be fully engaged with the ideas presented in the work, in a much more concrete way than many other genres of fictionalized storytelling. As such, even though I’ve marveled at and greatly enjoyed nearly every element presented

by K-On!, those same simple and rich elements had been subtly begging me to stop. They had begged me to stop my mindless acceptance of its message, and to bring in my own understanding, as well as to bring in myself, so that I might integrate an even more profound message into myself. After all, without being conscious of this self, my self, that was actively being conversed with by the work, how could I possess any accuracy or basis for my judgments about it? What sense of validity did I possess to judge any piece of art that didn’t make me question my thoughts, not only about the work itself, but also about the same thought processes used to question the art? To experience another’s art is to simultaneously become the product of the artist ourselves, and while the same efforts and feelings put into the work will almost never transfer one-to-one into the output we receive, our reception is, of itself, a unique canvas. I had, in my initial viewing of K-On!, nearly robbed myself of this gift given so directly to me by its youthful introspections. This realization caused me shame at first; I had been so eager, for so long, to abide by my surface and outsider impression of K-On!, yet when I had committed myself to its ideology I had almost neglected one of the most important of its many messages. However, as I luckily caught this feeling, the feelings of shame shifted towards optimism.