Cinnabar

Art By Cas Geiger

Art By Cas Geiger

Art By Cas Geiger

Art By Cas Geiger

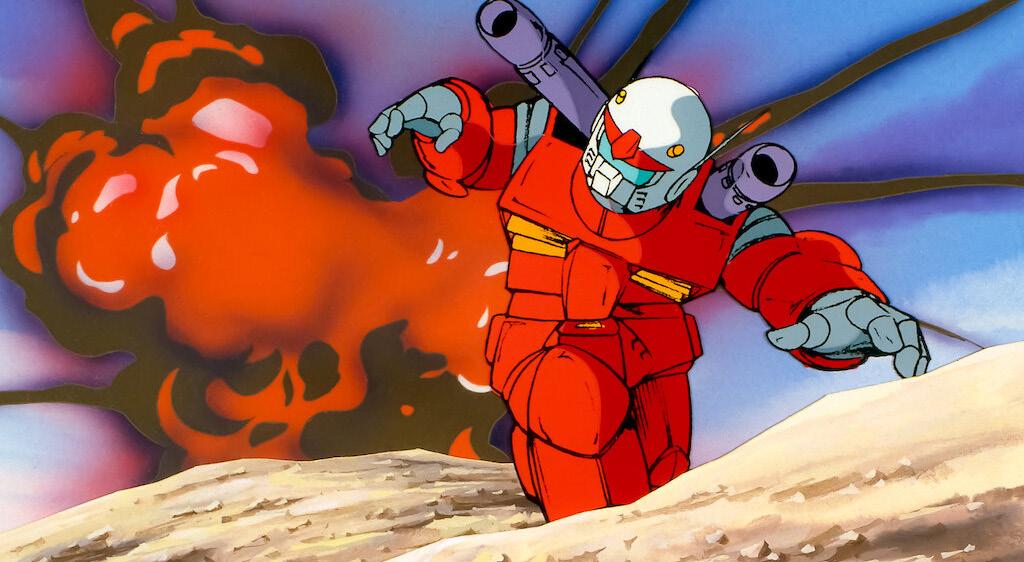

Unquestionably Tomino’s most well-known work, it is a space setting par excellence. The show (or the later-produced compilation movies recommended here) balances the horrors of war and the true tolls on human life with a well-written setting, interesting characters, and a classic story concerning a brutal war between a highly bureaucratic Earth and the rebelling space colonies surrounding it. It’s well worth the watch, and is a foundational pillar of a ton of other anime. In simple terms, it really is more than just big robots fighting.

Directed by Hiroyuki Yamaga

2 hours 1 minute

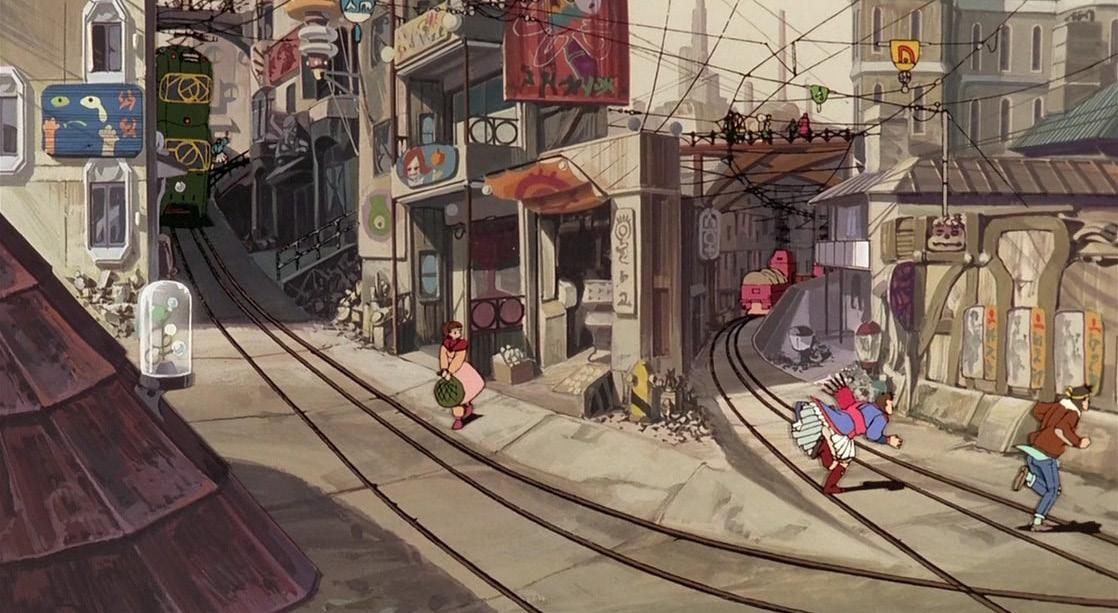

BY MAX ROTHMAN(Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honneamise)

This film is about the growth and development of Shirotsugh "Shiro" Lhadatt, a candidate and participant in the fledgling space program of the Honneamise Kingdom. While the program is left to the wayside as worthless with encroaching war, the RSF continues to try and put a man into space. A lovingly animated and well-rendered world, the kingdom and universe feel natural yet totally alien. The RSF’s striving to touch the stars is endearing to our own past struggles for the same- and the unifying greatness such achievements generate.

1981, Sunrise Directed by Yoshiyuki Tomino 3 films

1987, Gainax

1981, Sunrise Directed by Yoshiyuki Tomino 3 films

1987, Gainax

Stars and the aether often play a contextual role as a literal immediate space wherein the action can take place; it is however a pretty fairly widespread use to make them not exactly the place, but part of it – its firmament, its scenery. And in this case, this very scenery has more than simply an aesthetic interest. Starry nights are doubly defined: they require that two kinds of conditions be met. Spatially, the environment must be such that the eye, almost wherever it chooses to fall, does so on the sky and its uncountable lights – or at least its deep, navy blue, possibly mixed with dusty purple if the action is set in a city. Temporally, night is unavoidable: there must be no sun, or not enough for the moon and its shining cortège to be obscured. The characters involved by the action happen thus to be outside, and at a time when human beings are expected to sleep: the first effect, and perhaps the most researched one, of starry night is subsequently more or less artificial isolation. Two characters – sometimes, though rarely, more – are thereby in such a position that it is ideal for them to discuss. This is especially true when they happen to be on a journey at this moment, thanks to the scenario, and thereafter alone in huge spaces – if not with sleeping companions whose role will at most be to, precisely, break the situation by waking up and asking the others what they were doing or saying. Before it happens (if it does so), the starry night has created for those speakers a “most-outer-space”, perhaps more outer even than the interstellar one, always filled with massive and numerous spaceships. They are finely isolated (or at least so they think, and so is the spectator expected to think with them), meaning they can freely and frankly interact. Series like Fate Grand Order: Absolute Demonic Front Babylonia intensely use this technique – and rightly, for it is most easily inserted in their own context, and is extremely effective when it comes to building and defining, not that many charac-

ters, but rather relationships between them.

This “elsewhereness” of others might be the consequence of two things: either they do sleep, or they do something that explains why they do not sleep. In the latter case, the starry night is even more obvious when it comes to its “breaking role”: it is the physical outside, when night itself takes back its rights, by opposition to inner spaces where human activities keep going on, despite the sun being gone for a long time already. The starry night is also, in this situation, a decompression chamber: herein (or rather hereout), the ongoing activity absolutely ceases, it is at most a far rumour and an indistinct light coming through the window of the balcony. For, even though the most usual setting is that of the journey and the waggon or the caravan, it is not that rare that it be for instance a ball from which one character then another, or both at the same time, take a break on this very balcony, as it may happen in How Raeliana ended up at the Duke’s Mansion or the original Gundam series. In both cases, the balcony and its starry ceiling absolutely isolate characters from the ball (until they come back to it or are joined by some others). Conventions cease to rule every word and gesture, or loosens for a moment their hold. This goes a step further when it helps the characters leave behind them even their own rules for a decisive moment and crucial talks, which the somehow cosy and relaxing atmosphere which stars, obscurity and solitude bring with them enables. This is especially true for Kaguya-sama: Love is war – the first kiss that never ends, where night also provides a neutral space, where no character, not only dominates, but also needs to dominate. Sun-ruled day is a time to shine and perform in this very world: night, on its side, offers a way out of it, through dreams or through discussions friendly discussions.

The Irresponsible Captain Tylor is the type of series that generally won’t work on its own due to its status as a parody of stories with structured militaristic organizations. Yet, due to featuring a character who subverts the understanding of the leader of a serious organization as being the most responsible capable individual of said group, the series avoids the trap of needing further context. After all, the dynamic which it satirizes is inherently fairly obvious; coupled with wider mainstream understanding of science fiction and political stories thanks to series like Star Trek, Captain Tylor is consequently an extremely accessible series. Its appeal in escapism and comedy lies in the same roots as something like Great Teacher Onizuka. An under qualified individual being given a role with high responsibility and prestige, yet nailing it due to their unconventional tactics which break conservative expectations of what that role should entail. It’s a setup as old as time, transcending time and culture.

Where those two differ, though, is in how they are serialized. Where GTO is a series that lasts a while due to how it utilizes a formula of focusing arcs on different individuals which its protagonist must help and thus demonstrate the merit of his ways, Tylor instead works as one cohesive story. The entire original television series’ run focuses primarily on one period of time where the protagonist proves himself and his tactics worthy. Justy Tylor, as a sort of satirization of ‘Genius Captain’ characters like Legend of the Galactic Heroes’ Yang Wenli, is a rather stagnant character as the main arc of the series focuses on how his subordinates change their views on him. Furthermore, the actual setting of The Irresponsible Captain Tylor is not really all that important; given the series’ focus on comedy, it mostly acts as a sort of backdrop for gags that provide some level of ca-

tharsis. The Irresponsible Captain Tylor is thus a fundamentally solid gag parody series over its 26 episode run, with the main struggle of the plot, that of the main character overcoming the odds in increasingly unpredictable ways, coming to a logical conclusion by the final episode where, with his crew’s approval, he ditches the structured organization that he is a part of in search for adventure. It’s nothing special or unique, and to be frank, Tylor can get fairly crass or lowbrow at points, but there’s a lot of heart and effort put into the series’ portrayal of this aspect, which is why this finale comes across well.

In some regards, you can’t really tell that The Irresponsible Captain Tylor is based off of a light novel series. Partially, one could boil this down to an understanding that the tropes and conventions commonly associated with modern light novel writing were not nearly as potent in the era of Tylor’s release. There’s some truth to that, but it’s still striking how the series feels animated with goofy expressions and overblown reactions doing a lot to imply how characters are feeling. It’s not like the series has amazing production values or anything, but a part of its charm is in how kinetic it feels. The sequences of Tylor avoiding danger by accident are made all the more compelling due to how the series is directed, something which I think speaks to the strength of it as an adaptation. There’s some parts that really don’t look great, but the bombastic portions that really matter are done well. As a whole, Tylor really isn’t something that I consider an outstanding masterpiece of its era or anything, but it’s enjoyable and there’s nothing wrong with that. A solid 7/10, if you will, which in some part is down to how the conclusion of the series contains a large amount of energy in its direction and presentation.

That said, the followup OVA series consisting of ten episodes seems to waver with its understanding of what makes Tylor work. The first two episodes follow up the television series relatively well, or at least as well as you can do in succeeding a story which seems pretty concluded. There’s some aspects of its construction that feel disjointed, such as the main conflict in the story’s background still occurring despite the television series closing up that plot point, but it seems like something that would be the result of the television series choosing a specific point to end in its adaptation of a still-serialized novel series. Having never read the series, I can’t necessarily say this with any level of certainty, but I would not be surprised if the television finale took certain liberties, which is why I don’t necessarily mind. The plot of the first two episodes aren’t anything groundbreaking, but then again, that isn’t really a big deal as they deliver a similar sort of dynamic as the series with everything feeling truly concluded by the end. One aspect in which they exceed the television series is in their production, which is something of a given due to being OVAs. Still, despite my personal predilection towards the television series’ Tatsunoko Production over the OVAs’ Studio Deen, the OVAs undoubtedly look better. There’s a real focus on delivering the sort of science fiction aesthetic that something like The Irresponsible Cap-

tain Tylor warrants in the sort of series it satirizes, and yet the series still feels whimsical as it is, after all, a parody.

Where I get a bit more negative is with the following eight OVA episodes, which seem to eschew the series’ strengths in favor of adhering to source material. Again, I’ve never read the novel series, nor do I plan to, so I can’t exactly make comparisons with too much authority. Yet, the way the rest of the Tylor OVAs are written feels distinctly like the product of a light novel, which is the opposite of the way the television series came across. They feature a sharp increase in pondering monologues from various characters, as well as elaborations on the wider universe of The Irresponsible Captain Tylor This doesn’t necessarily sound like a terrible thing, but it isn’t all that preferred given the type of story Tylor is; while the background characters are important features of Tylor, they don’t necessarily warrant extra elaboration into their deeper thoughts or focuses. After all, they primarily work as reactionary figures to the bizarre shenanigans that Tylor gets them in.

mainly focuses on one character. After all, there’s a reason why the protagonists’ name is in the title – he fundamentally drives the plot. Even episodes of the television series where he does not physically appear still work because he remains a narratively important subject that the other characters ponder upon. As several of the OVA’s episodes strongly focus on other background elements, they lose the series’ charm and become basically any other military science fiction story.

Generally speaking, I tend to have biases towards stories that truly work on their own without any need for outside information on tropes or conventions of a given genre. While the television series of The Irresponsible Captain Tylor sometimes relies on some understanding of a sort of story type, it remains entertaining even without that context due to its fundamentally simple premise. The complex political/military dynamics and the world being fairly scientifically developed are, if anything, gimmicks for a story which is in reality a simple comedy about a fool who is in reality hypercompetent due to his idiosyncratic behaviors. In that way, it draws comparisons to, say, comedy series like The Office (US) or Great Teacher Onizuka After all, it’s fun to consider that even those we consider worthy of respect are, in reality, fools who just get lucky. It subverts our understanding of societal norms while also allowing viewers to feel better about their own lives, likely as a small part of larger organizations, whether that be the military, a place of education, or a workplace.

Beyond that, the setting of The Irresponsible Captain Tylor is also something which the television series rightfully lacked more detail in. In part, extra detail on the workings of Tylor’s world was unnecessary due to the dynamic of the series as it serves to bog down the pacing of the story even more in the OVA. The Irresponsible Captain Tylor in part works due to, again, the audience’s vague understanding of tropes within these sorts of political and science fiction narratives. Something like Legend of the Galactic Heroes was able to serialize itself further with its Gaiden episodes due to how the entire point of the franchise was its presentation of a fascinating multi-layered world with numerous parties, factions, and agendas at play. That sort of series was thus highly conducive to further material being made to give more understanding to different characters and the world as a whole. Tylor, on the other hand, is far more of a story that

Excluding the enjoyable first two entries, the followup OVA series for Tylor runs into issues as its style is more conducive to comparisons to more serious science fiction stories rather than comedies. The Irresponsible Captain Tylor is far less equipped to deal with a different set of expectations akin something like Legend of the Galactic Heroes or Star Trek, as its roots are primarily in comedy. In some regard, the issues with Tylor’s later entries are somewhat similar to my issues with the follow-ups to Crest of the Stars. As I mention in my article, Crest of the Stars works as a romance-adventure series with a scientific backdrop. The later Banner of the Stars entries fail due to focusing far more on political exchanges in said science fiction world. In the case of both Banner of the Stars and the Tylor OVAs, the focus on background elements draws unneeded comparisons to works of a different genre which they ultimately pale in comparison to. In some regard, the fact that they are both light novel adaptations likely contribute to this issue. Given my speculation, I believe that Tylor is indicative of issues that light novel authors encounter in not recognizing their own strengths and weaknesses. It’s not terrible, but it serves as a good case study of narrative scope. In some regards, I think that more focus should be emphasized in media. There are exceptions where it works out, but often, a lot of stories try unsuccessfully to be thirty different things at once where they could be one or two things superbly.

13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim is a sci-fi role-playing game that wears many of its anime influences on its sleeve. In addition to its masterful anime-inspired art style, certain plot points also reference notable anime such as Super Dimension Fortress Macross, Megazone 23, and The Girl Who Leapt Through Time. Despite these homages initially seeming derivative, many critics and fans have agreed that 13 Sentinels is much more than the sum of its parts, and that it easily possesses one of the best sci-fi narratives of the past few years. Even the famed auteur Yoko Taro has gone on record to praise this game for its brilliance. With all of this critical acclaim and popularity, some fans have understandably called for an anime adaptation. This is a very bad idea.

Another issue that comes up in the conversation of adapting 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim is more central to its main selling point. 13 Sentinels is very unique, even within the realm of gaming, as it has 13 main characters. Aside from the main characters, there are also many side characters with complex motivations and backstories. Aside from the obvious pacing problems this alone would bring, this issue would also ruin the identity of 13 Sentinels. In the game, each of the main characters’ individual chapters reveal more about the overall plot, as well as uniquely connecting the characters to each other. The beauty of this game is most clearly seen when different characters interact with each other in different scenarios, because the player has insight into all of the characters’ pasts. Without spoiling, this kind of storytelling would be impossible to deliver on, even if the story was rearranged, due to the characters’ intersections and interactions being nonlinear.

A common problem that comes when adapting video games into anime is simply the difference in time between the two mediums. 13 Sentinels has around 30 hours of content, while a typical anime-adaptation season may only be around 26 episodes. Even factoring in reasonable parts to skip or change, the time difference suggests how unreasonable asking for a good adaptation would be. This issue can also be seen with other adaptations like Persona 5: The Animation and Nier: Automata Ver1.1a, which have both been criticized for terrible pacing and unfaithful representation of its source material. This problem is compounded by the fact that 13 Sentinels itself has an insanely complicated story, with around 250 plot-essential key terms. There is absolutely no possible way in which its narrative could be delivered within the anime medium, given anime’s more linear nature.

Hypothetically though, if 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim is adapted into an anime, there are actually many aspects of it which would translate seamlessly. For one, the initial impressions of some characters and plot elements clearly fit established archetypes, and a lot of the dialogue takes inspiration from slice-of-life anime. The game could also carry over its stunning imagery of food, lighthearted comedy, and other tropey moments heavily associated with a high school setting. Another component that would translate well is the original soundtrack of the game, due to the game composer (Hitoshi Sakimoto) drawing inspiration from his prior anime soundtracks.

As much as it pains me to say this, 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim can never be a good anime. Keep in mind, this is coming from someone who has extensively and lovingly played the original game. While it has all the right aesthetics and drama, its sheer depth of storytelling would make it an impossible fit for an anime format. Furthermore, an improper adaptation would risk butchering its hard-earned reputation, and could alienate potential fans. This adaptation is simply impossible.

RAHM JETHANI

RAHM JETHANI

3rd Year, Philosophy and Biology

Clarke’s Third Law is, in my opinion, often the wrong way around.

There are countless series, anime and otherwise, that concern themselves with the final frontier. From A Trip to the Moon to The Expanse, the cosmos presents a wide canvas on which to paint a narrative. Despite the void being as such, space itself requires worldbuilding. It is not merely a barren highway between narrative setpieces, but a stage itself. The depiction of how individuals interact on and with this stage is important, and a hard choice presents itself. Unlike most other places, the void is hostile to all life. Answering the question of where and how people live is a delicate one, where the answer dictates whether a piece of media leans to science fiction or science fantasy. I assert that through the challenge of balancing the two, a creator can achieve a setting that feels thought out and believably realistic, but still leave room for fantasy that can sit supported by the audience’s suspension of disbelief.

Worldbuilding sets the characterization of environments and the background populating it. If the narrative and events wildly contrast the setting’s flavor, the whole story can start to disjoin itself. To this end, space must be dealt with. Often, the answer to space in sci-fi is handled simply. It is in that merely a space between places of interest, an equivalent of an ocean crossing between continents. With various modes of transport, characters traverse it, and the details of this are effectively wrapped and done. Any concerns are usually addressed with fantastical means – hyperdrives cut travel to nothing, ships just have perpetual air and gravity, etc.

However, the more grounded a piece of media is supposed to feel, the more attention must be paid to this. Even if fantastical elements cut it, real questions suggest themselves to the audience. The care put into this – in writing and presentation – can show an informed writer from an uninformed one. Properly illustrated vehicles, liv-

ing conditions depicted with mindfulness to the setting, and so on, all contribute to push a world that much closer to ours.

But what of series that sit in the middle between futurism and fantasy? In these, the balancing act becomes the most challenging to sell best. Enough care and attention must be paid to make aspects feel plausible and real, but left open enough to not over-answer granularly and ruin the higher aspects of a world. With all the bias I can muster as a writer, I can use Mobile Suit Gundam as an example of doing it right in this regard. The broad setting and the background are well designed to balance real astrophysics and fictional designs. O’Neill cylinders are existing concepts closer to reality than fiction, with aspects such as food procurement, gravity, and society being addressed to push the narrative home. By having believable life in space, and realistic (enough) means of getting to and from space, the narrative has to keep these in mind while managing to change enough rules to get around the square-cubed law. To my biased self as someone who greatly enjoys good science fiction, this is the most savory setting. It (or any other equal example) shows care to truly think how we could live in the future, however far flung, but can stay inspired enough to show fantastical things.