ALGONQUIN

FRIENDS OF THE PARK

Record attendance to build on, in 2022

FEMALE GUIDE BLAZED A TRAIL

Esther Keyser inspired generations of trippers

PROJECT CANOE

Transforming lives through the power of the outdoors

GATEWAYS TO THE PARK • SHUTTERBUGS GATHER AT ‘HOWL’ • BIRTH OF THE PARK 2022 EDITION 2022 EDITION ALGONQUIN LIFE

ExploreA place to

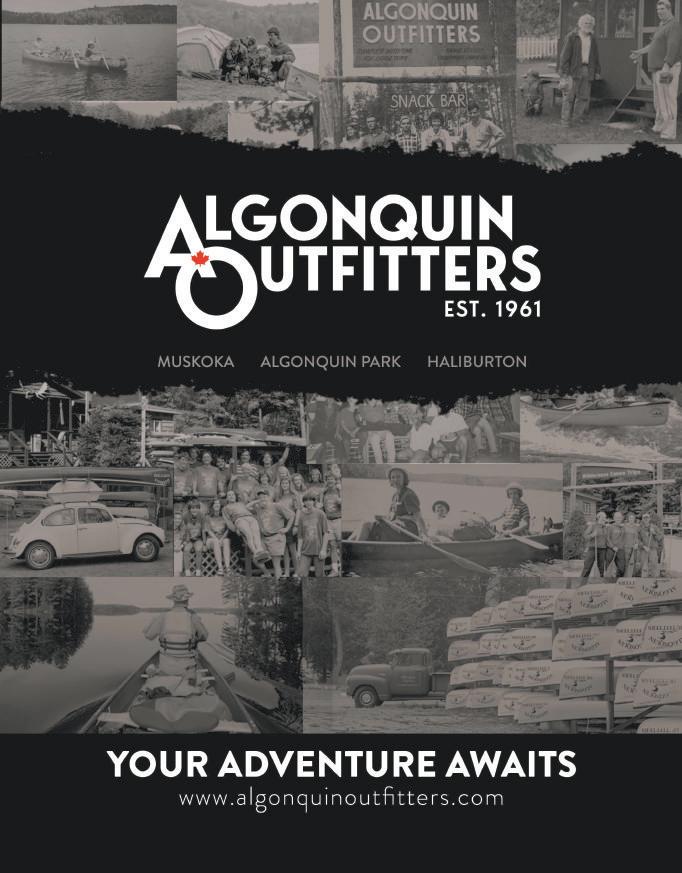

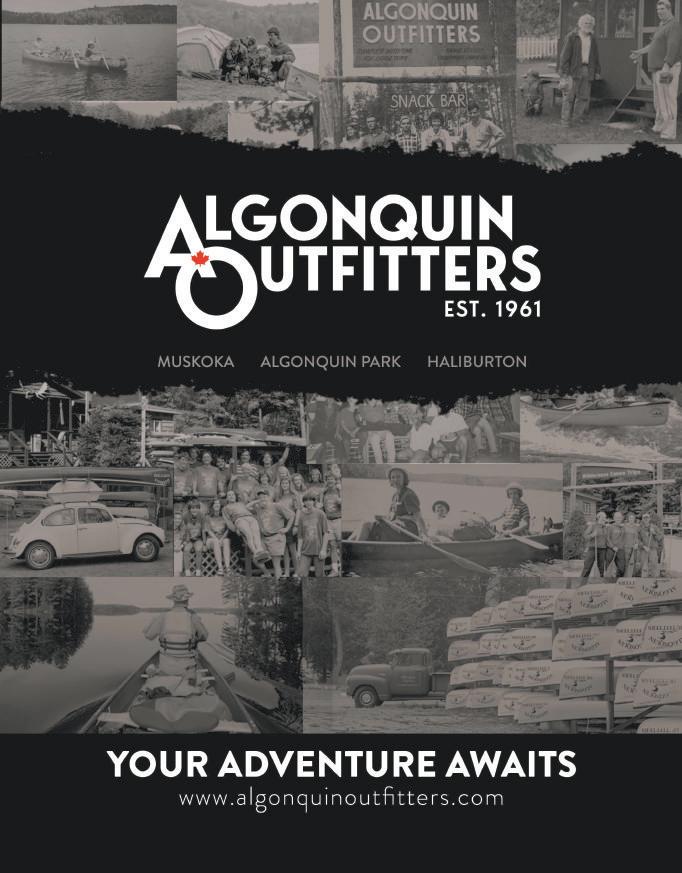

to you by

‘Your Adventure Awaits’ Brought

Com fortand fu ncti onality on thetrail

ThenewAbiskoTrekking TightsPro

For a better nature experience,choose clothing andequipmentthat fitsand worksperfectly.The new Abisko Trekking Tights Pro have beende velopedwithoptimal comfor t andfunctionalityinmind.Madefromacompressiveand fast-dr yingdouble-knittedstretch fabricin recycledpolyesterwithabrasion-resistant Cordura overtheseatand

knees.Securelegpocketswithenvelopeclosures,angled ergonomicallyforeaseraccess.Andacomfortable,high waistbandthatcanbeadjustedwithaninsidedrawstring. Functionalityandfeaturesthat,onthetrail,willjustwork andnot getintheway oftheexperience Ontrailaftertrail. Welcometo fjallraven.com or yournearestFjällrävendealer

www .f ja llr aven. co m

4 ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022

WHAT’S INSIDE

17

34 NOT ANY ORDINARY EEL The Kichisippi Pimisi holds a special place in Algonquin people’s past ... and hopefully has a promising future.

62 THE MESSAGE? GET OUTDOORS! Social media has power to promote the Park, but must be used wisely.

EDITOR’S NOTE Venturing deeper into Algonquin.

WELCOME TO ALGONQUIN LIFE Sharing a love of the outdoors.

GATEWAYS TO THE PARK Your access point will determine the enjoyment of your Park experience

10

11

13

MEET

Welcoming visitors – new and

– with big events

for 2022.

ALGONQUIN’S ‘FRIENDS’

old

planned

to help youth

the right trail.

21 IMPACTFUL OUTDOORS Businesses contribute

find

26 MASTER PLAN FOR THE PARK Recounting the long journey to set up a management plan for Algonquin.

Settlers left to make room for the Park. team up to create award-winning film.

The Algonquin journey of Esther Keyser.

SPIRIT planned 36 TRAIL BLAZER 43 BANISHED AND REMOVED 48 GETTING READY TO ‘HOWL’ Photographers gather at convention 56 PADDLING TO ‘TUMBLEHOME’ Canoe maker and cinematographer

64 WINTRY WILDERNESS and explore a special season here. 66 ADVENTUROUS

36 62 48 26 64 8 ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022

summer morning at Big Porcupine Lake, Algonquin Provincial Park.

ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 9

Venturing deeper into Algonquin

Algonquin Park is a vast, magnificent national treasure and – try as you might – you will never get to explore it all. With more than 7,700 square kilometres of epic terrain, this is a broad ecosystem, home to an amazing assortment of wildlife – from the majestic moose, right down to the smallest black fly larvae. You could spend a lifetime traversing its trails and waterways, and still have more to experience.

That metaphor also applies when assembling Algonquin Life magazine, especially when a certain global health crisis means it’s our first since our wellreceived inaugural 2019 issue. While our magazine took a hiatus, visitors to the Park didn’t – arriving in record numbers – to reconnect with nature when we all needed it most. And, like those disappointed when daily park capacity sold out, we wish we could fit in more stories.

Thanks to our partnership with Algonquin Outfitters (and their partners also advertising in this Algonquin Life), we are happy to be able to print more than 20,000 copies of this volume. Thanks to Algonquin Outfitters, you can find Algonquin Life in all their retail locations in and around the Park. We are also distributing the publication to the Algonquin Visitor Centre and other locations. Stories in this edition contain some helpful information about the Park, but we won’t be telling you how to pack for a backcountry excursion or even how to start a fire – you’ll have to ask the experts. The “fire” we hope to start is one of appreciation for Algonquin, through thoughtful features about people inspired and influenced by the region, and those instrumental in the health and preservation of the Park and its ideals.

We hope the following pages take you “deeper” into Algonquin and its past, present ... and its future promise. When you visit and explore this special place, be open to discovering something about yourself, too.

Vice-President, Content, Community and Operations

Dana Robbins

Vice-President, Community Sales

Kelly Montague

Regional General Manager

Shaun Sauve

Regional Director of Creative Services

Katherine Porcheron

Advertising Director

Jack Tynan jtynan@starmetrolandmedia.com

Distribution Manager

Andrew Allen aallen@metrolandnorthmedia.com

Editor Dave Opavsky dopavsky@metroland.com

Creative Services Supervisor

Juanita Gabriel

Graphic Designer

Brenda Boon

Account Representatives

Michelle Gallagher, Michael Hill, Jennifer McCrackin, Karen Morrison, Glenn Ward

Sales Co-ordinator

Christa Derry sales@metrolandnorthmedia.com

Contributors

Andrew Hind, Patti Vipond, Christine Luckasavitch, Roderick MacKay, Rich Swift

Editorial Office and Sales Metroland Media

345 Ecclestone Dr. Unit 8 Bracebridge P1L 1R1 tel: (705) 789-5541

Algonquin Life is published each June.

To purchase a copy of Algonquin Life, order online at metrolandstore.com, where you’ll find us under Magazines/Lifestyle

Contents may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the publisher’s written consent

A publication of Metroland Media Group Ltd.

DAVE OPAVSKY, EDITOR dopavsky@metroland.com (For more, go to algonquinpark.on.ca)

sales@metrolandnorthmedia.com

algonquinlife.ca

10 ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 EDITOR’S NOTE

Q ALGONQUIN

(Photo: Karen Burgess | dreamstime.com)

Happiness is ALGONQUIN PARK

I’ve spent my life in the Park. My father came to Algonquin in the 1940s as a camper at Camp Pathfinder and the park has a been part of our family ever since. I continue to have the same passion for the outdoors and adventure that I had as a camper at the same Algonquin camp when I was young.

I’ve been very fortunate to share this love for the outdoors with my lovely wife Sue and our children Jessica and Tanner. It’s so rewarding to see them continue to live their lives with that same passion for adventure and love of the outdoors. Being able to build a business and a career around this love has been incredible. I have had the opportunity to meet and work with so many amazing people through Algonquin Outfitters and it’s these people that continue to inspire me to share this beautiful place with everyone. The roots and core of our business will always be connected to Algonquin and this beautiful area I’ve been fortunate to call home.

I still love to be on the water. I still love to be on a trip. I still love to be in the park. My father once told me, “Do what makes you happy in life” ... and for me that happiness is Algonquin.

I’m so happy to be able to share that with generations of my family and yours.

Algonquin Park at a Glance

• Algonquin Park is 7,725 square kilometres in area, larger than the entire province of Prince Edward Island.

• The park is located about 300 km north of Toronto, and about 260 km west of Ottawa, at approximately 45.8°, -78.4°.

• More than 2,000 lakes dot the landscape

• Algonquin is a natural paradise, with more than 2,100 kilometres of canoe routes and 140 kilometres of hiking trails

– Rich Swift

– Rich Swift

•The park lies in a transition zone between northern boreal forest and southern deciduous forest, resulting in teeming ecological diversity

• More than 1,000 plant species and 200 animal species live in the park, including 10,000 beavers, between 150 and 300 wolves, and approximately 4,000 moose

• More than half a million visitors each year are drawn to Algonquin, with 300,000 coming in July and August

ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 11

WELCOME TO ALGONQUIN LIFE ...

Algonquin Outfitters owners Rich and Sue Swift (right) and dog Finn, canoeing with their son Tanner and his wife Hannah (left).

(Photo: Limelight Photography)

A gathering of Algonquin Outfitters staff.

(Photo courtesy Algonquin Outfitters)

12 ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022

DOZENS of access points to the Park

BY ANDREW HIND

BY ANDREW HIND

For many visitors to Algonquin Park, Highway 60 – the Parkway Corridor – is all they know. This 56-kilometre roadway bisects the southern part of the park, entering from the west near Dwight and from the east near Whitney. When most people speak of entering the park, they refer to one of these entry points.

That’s perhaps understandable. Most of the park’s iconic attractions – the Algonquin Visitor Centre, the Algonquin Logging Museum, Bartlett Lodge and Killarney Lodge, Algonquin Art Centre – are found along this corridor. It’s also the easiest way to experience the Park: have car, will travel. But Highway 60 isn’t the only means of entering Algonquin Park. There are many more, far less-used access points.

“Algonquin Park is massive, with more than two dozen lesser-known access points scattered around its periphery,” explains Lee Pauze, executive director of the Friends of Algonquin Park. “These access points vary in terms of the amenities they offer. Most are really intended as a jumping off point for striking out into the interior, with no facilities and little for day-trippers to experience.”

There are exceptions, though. A handful of access points serve as launching points for backwoods adventures while also providing amenities and/or experiences for day-use visitors.

One of the more popular is at Brent, located at the far north end of the park on Cedar Lake. Once a bustling lumber town, the site of Kish-Kaduk Lodge, and a stop on the now defunct Canadian Northern Railway, Brent’s fortunes have declined since mid-century and today all that remain are a few atmospheric buildings. There’s a campground, and an Algonquin Outfitters outlet occupying the old train station.

Brent is also the site of the only interpretive trail on the north end of the park, leading to the Brent Meteor Crater. You can climb a lookout tower to gaze over this vast crater, dating back almost 400,000,000 years, and then hike down into the bowl.

ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 13

Many consider the Barron Canyon Trail – which overlooks the namesake canyon with its 300-foot cliffs – to be the Park’s most stunning natural feature.

(Photo by Bev McMullen)

Selection of access point will determine your enjoyment of the Algonquin experience

Also in the park’s north is Kioshkokwi Lake - Kiosk Access Point. Like Brent, Kiosk was once the site of a thriving lumber town. And, also as with Brent, there is now a fine campground here today, with flush toilets and an excellent beach. A unique feature is the circa-1927 fire ranger cabin that can be rented out.

Achray, in the park’s east, has much to recommend itself as well. Indeed, after the Parkway Corridor, it has more facilities than any other part of Algonquin, including campgrounds overlooking Grand Lake complete with flushing toilets, a beautiful beach, park offices, and a theatre for interpretive programming. There are also several interpretive walking trails ideal for day use, including: the Berm Lake Trail that begins at the campgrounds; the more ambitious 17-kilometre Eastern Pines Backpacking Trail; and the Barron Canyon Trail – which overlooks the namesake canyon with its 300-foot cliffs (many consider it to be the park’s most stunning natural feature).

And, of course, if backcountry hiking or deep woods canoeing is your game, there are many more access points to choose from, each another adventure, with endless beautiful scenes of nature. The variety of experiences is one of Algonquin’s greatest assets; it can be many things to many people.

“The selection of access point will really determine your enjoyment of the park experience because they are certainly not all the same. We often get calls from visitors who went to one of the remote access points and then were surprised when there was nothing there,” says Pauze. “It also comes into bear in the fall, because the park’s east is at a lower in elevation than the Parkway Corridor and its forest is mostly pine, which means fall colours are far less striking.”

Algonquin is a vast park with many access points offering access to this natural treasure. But not all access points equal. Reach out to park staff or a knowledgeable outfitter to ensure the one you choose matches your envisioned experience.

14 ALGONQUIN LIfe 2022

Listing&SellingThroughout Algonquin ♥ Muskoka ♥ Haliburton YOU COULD BE HERE BA.,SalesRepresentative 705-787-5463 ElissaBoughen PARKLEASES |WATERFRONT | RESIDENTIAL | LAND 2676MuskokaRd117,BaysvilleP0B1A0705-767-2121

ADVENTURE. RINSE. REPEAT. Weaddedstainreleasetechnology rightintothefabricsomoststains, evenredwine,disappearwithaquickrinse. Youcannowfreelyadventurefrom trailtotable. INTRODUCING THESPOTLESSDRESS RoyalRobbins.com

16 ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022

Par rySoundIndustrial Park 25WOODSROAD NOBE L, ON 705-342-1717 http://www.bobcatofparr ysound.com Bobc at ®,theBobcatlogoandthecolorsoftheBobcatmachineareregisteredtrademarksofBobcatCompanyintheUnitedStatesandvariousothercountries. ©2022BobcatCompany.Allrightsreserved.15749583 B OBCA T .C OM Ifyourideaofhighperformancemeanshighproductivity,then Bobcat ® utilityvehiclesaremadeforyou.

“WhenIthinkofBobcat equipment,Ithinkofreliable, hard-workingmachinesand gettingthejobsdone.”

-CarsonWentz ProfessionalQuarterback

“We’re back,” says Lee Pauze, Executive Director the Friends of Algonquin Park. The woman who heads the not-for-pro t charitable organization can barely control her excitement. Friends of Algonquin Park is, after all, devoted to interpretive outreach – it was founded in 1983 with a mandate to support Ontario Parks, principally in furthering the Algonquin Park’s vaunted educational programs.

But outreach is hard to do with COVID restrictions in place.

“We – the Friends and Ontario Parks –were cautious and conservative during the worse of the pandemic, and much remained closed or extremely restricted,” Pauze explains. “We’re starting to miss people, though, and are really looking forward to them returning to our facilities this year.”

Not that there was any shortage of visitors to Algonquin Park over the past two years. Visitation was way up about 150 per cent above normal each of the last two years as travel options were curtailed.

“The pandemic saw a rush of people coming who were discovering Algonquin Park for the rst time. They saw the park as something was that was COVID-safe and accessible, and of course something that was beautiful,” says Pauze. “I’m exciting about this development because they represent a whole new group of people coming.”

But the sheer number of people represented a problem. Any park has a capacity limit; exceed this limit and it begins to negatively impact the visitor experience. One of the ways Ontario Parks decided to manage the sudden in ux was by doing away with selling daily vehicle permits at the gates and mandating that they had to be pre-booked (up to ve days prior to the visit).

“Some people who were used to the old system resisted the change, but permits have been an invaluable in ensuring a positive visitor experience,” Pauze explains. “Perhaps more importantly, managing the number of people helps to sustain Algonquin. The park represents a nite

ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 17

e Friends of Algonquin Park are eager to greet visitors again

BY ANDREW HIND

(Photo courtesy the Friends of Algonquin Park)

Algonquin Park was one of the few Ontario Parks properties that were able to open their visitor centre, thanks to the generosity of the Friends.

resource. How much can it withstand? You can love something too much; there may come a time when the park’s popularity becomes detrimental, and we may need to close popular trails for rehabilitation.”

The sudden in ux of people visiting the park for the rst time posed another challenge. The Visitor Centre has always represented a vital messaging tool – it’s where people went to discover how to make the most of their visit, and how park staff educated visitors about safety and rules. But when the pandemic struck like a hammer blow, visitor centres in park and across the nation were shuttered.

Algonquin Park was one of the few Ontario Parks properties that were able to open their visitor centre, thanks to the generosity of the Friends. The group stepped forward to purchase state-ofthe-art software for a capacity counter, counting patrons as they entered and left, keeping an accurate count that is displayed it on a Smart TV to ensure capacity limits were not exceeded. More, the counter is linked to an app that visitors can access on their phones, so they know when the facility is quiet and therefore safe to visit without crowding.

With the worst of the pandemic behind us and the Friends back in full-outreach mode, visitors to the park in 2022 will enjoy a much-improved experience from the sometimes-chaotic 2020 and 2021.

“We are returning to our signature special events this year,” says Pauze, acknowledging that in the pandemic-era one need to plan for change just in case. “I think there is an appetite for longtime visitors to return to family traditions. Many would book their camping vacations around our annual events, which of course were cancelled the last two years due to COVID.”

These events include: Loggers Day (July 23), bringing to life Algonquin’s logging

Algonquin Park’s signature

LOGGERS DAY

(10 a.m. - 3 p.m., Saturday, July 23 at the Logging Museum.

Admission $2)

Loggers Day is a fun and educational event that brings to vivid life Algonquin’s logging past. There are numerous demonstrations, sample an old-time loggers’ lunch (noon to 2 p.m., while quantities last, $10 per person), and listen to the music of the Wakami Wailers throughout the day.

Logging Days represents a great opportunity to explore the Algonquin Logging Museum, which includes a recreated camboose shanty, log chutes, old stables, blacksmith shop, sleighs for transporting logs, and a steam-powered ‘alligator’ (a tug that could actually portage across by land between lakes and river).

MEET THE RESEARCHER DAY

(9 a.m. - 3 p.m., Thursday, July 28. East Beach Picnic Pavilion)

The Algonquin Wildlife Research Station (AWRS) is a little-known but integral part of Algonquin Park. Founded in 1944 to produce high-quality research to inform wildlife management, the staff at AWRS has studied many species of reptiles and amphibians, sh, birds, and mammals (including Algonquin’s iconic wolves). ‘Meet the Researcher Day’ offers the public a chance to meet biologists and learn about their work Includes a fundraising barbecue (noon to 2 p.m., or while quantities last).

CELEBRATING ALGONQUIN PARK

(7 p.m. - 10 p.m., Saturday, Sept. 10. Algonquin Visitor Centre) Close out the summer with an evening of presentations on all that is special and beautiful about Algonquin Park and the Canadian wilderness it represents. Guests will have an opportunity to meet the varied presenters, and there will be silent auction, door prizes, and refreshments served. Admission and pre-registration required (algonquinpark.on.ca/news/celebrating_algonquin_park.php).

For updates on all events, go to www.algonquinpark.on.ca/ involved/calendar/

past and present; Meet the Researcher Day (July 28), where you meet the scientists and tours facilities at the Algonquin Wildlife Research Station; and Celebrating Algonquin Park (Sept. 10).

In addition to special events, Algonquin will once again play host to its interpretive

programming, such as the popular Public Wolf Howls, Evening Programs at the Outdoor Theatre, and Guided Walks with Park Naturalists.

“We can’t wait to welcome people back to Algonquin Park and to re-introduce them to our events and facilities,” says Pauze.

18 ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022

GETPACKSTHATCAN CAR RY ITALL. AV AILABLEFORSALE AT INSPIRED BY CANAD A ’SBEAUTIFULALGONQUIN PROVINCIAL P ARK,TIMELESSPIECESOFGEAR. VOYA GEUR CANOE PA CK BADHASS BAR R ELHARNESS | 30 & 60L ALGONQUIN CANOE PA CK | 95L ALGONQUIN55 BACKPA CK | 55L WWW. LEVELSIX. C OM WWW.SHOP.ALGONQUINOUTFITTERS. C OM

Impactful outdoors

The sweet summer anticipation of tasting a cool new brew has an additional pleasure kick this year.

In July, Lake of Bays Brewing Company in Baysville is introducing Birch Blonde, a refreshing blonde ale. However, sales of the new ale will do more than please beer lovers’ palates.

Lake of Bay Brewing Co. is raising funds for Project Canoe through a collaborative brew with @AlexisOutdoors (a.k.a. Careena Alexis), a well-known Ontario outdoors enthusiast and YouTuber with followings on Instagram and Facebook. A portion of the proceeds from the collaboration will support Project Canoe, an organization that has provided camping and canoe experiences to marginalized and disadvantaged urban youth since 1977. In addition, Algonquin Outfitters in Huntsville will match all donations made to Project Canoe by the brewery.

On her Alexis Outdoor website, Alexis says her mission is to encourage everyone, especially women and young persons, to get outside and learn the skills needed to be comfortable in the great outdoors.

“When @AlexisOutdoors introduced us

to Project Canoe, we were super excited to support an Ontario charity whose mission is to provide youth with opportunities to build self-esteem, self-awareness, and selflove through the power of educational and therapeutic outdoor programming,” says Lauren Young, marketing manager at Lake of Bays Brewing Co.

Since Project Canoe’s launch 45 years ago by Dr. Herb Batt, the organization has helped over 4,000 marginalized and disadvantaged urban teenagers to experience camping through their wilderness canoe programs in Ontario’s Algonquin Provincial Park. This year, the organization is offering five-day canoe trips on July 1-5 and Aug. 22-26, and eight-day canoe trips on July 21-28 and Aug. 8-15.

The goal of Project Canoe’s camping trips goes beyond fostering the campers’ appreciation for nature’s beauty. The program is designed to teach important skills that the participants will use throughout their lives. As well as learning basic canoeing and wilderness camping skills, campers become team members who learn cooperation and relationship building. They build a supportive community around

ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 21

Businesses contribute to help youth find the right trail

Project Canoe uses the outdoors as a transformative environment where kids have a chance to develop the resiliency needed for future success.

Careena Alexis (centre) who is @AlexisOutdoors, an influencer doing a collaborative brew with Lake of Bays Brewing Co., is pictured with LOB brewers James (left) and Brandon(right).

(Photo courtesy LOB Brewing Co.)

Lake of Bays Brewing Co. and Algonquin Outfitters are supporting young campers taking Project Canoe’s summer trips through sales of new Birch Blonde beer.

STORY BY PATTI VIPOND

PHOTOS: PROJECT CANOE

Since Project Canoe’s launch 45 years ago, the organization has helped over 4,000 marginalized and disadvantaged urban teenagers to experience camping through their wilderness canoe programs in Ontario’s Algonquin Provincial Park.

themselves while, importantly, having lots of fun amid the spectacular landscapes and lakes of Algonquin Park.

Project Canoe staff use the outdoors as a transformative environment where kids have a chance to develop the resiliency needed for future success, often despite significant barriers in their lives. Campers come to Project Canoe through children’s aid societies, mental health agencies, schools, community organizations and recommendations from friends and family. These children would otherwise be unable to go camping because of financial, social, emotional, learning and behavioural limits. Children are never disqualified from applying or going on camping trips because of finances. Project Canoe has bridged that gap for thousands of kids over the years and given them access to the Canadian wilderness that they might never have experienced otherwise.

The organization has an industry-leading staff to youth ratio of one staff for every two youth. This helps create connection between all campers during trips and gives them opportunities to develop social skills. All staff is trained in Advanced Wilderness First Aid, CPR and have National Lifesaving Society certification as well as Therapeutic Crisis Intervention certification.

Project Canoe’s summer wilderness canoe trip program is the organization’s core program, but educational nature hikes and special single day nature programs for youth in High Park are also offered in Toronto during the year. Volunteers help run events, fundraising and summer programs, and also reliably donate gently used outdoor gear and clothing for the campers.

“Our company’s heart and soul started with a love for the great outdoors, so we really felt their mission reflected our values in promoting people to take a step back from their busy lives and enjoy the great outdoors and what it has to offer,” says Young. “We know how impactful the outdoors can be to one’s life and are proud to be able to support a charity who understands that as well.”

22 ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022

Lightweight

fu ncti onality on thetrail

ThenewKebAgileTrousers

For a better nature experience,choose clothing andequipmentthat fitsand worksperfectly.The new lightweight Keb Agile Trousers combineexcellentfreedom ofmovement withdurabilityandprotection.Madeinadouble-woven, quick-dryingstretchfabricusingrecyclepolyamideand

elastan.Thelegpocketsandkneesaremadewith G-1000 LiteEcoStretch forextraabrasionresistance.Functionality andfeaturesthat,onthetrail,willjustworkandnotgetin thewayoftheexperience.Ontrailaftertrail.Welcometo fjallraven.com oryournearestFjällrävendealer.

www .f ja llr aven. co m

26 ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022

The Stein family, visitors from New York State on a day trip in the Park interior, in the early 1980s. (R. MacKay collection)

A SENSE OF

aving wildernessS

BY

BY

“Algonquin Park should be a natural environment where people ... can escape for a while from the increasing pressures of urban life”

– Bill Calvert

ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 27

RODERICK MACKAY

It was noted back in the pages of Algonquin Life 2019 that when Algonquin Park was established by the Ontario government in 1893 it was far from being a true, untouched wilderness. Loggers had harvested pine there for many years and fires had scarred the landscape. Much of what land was forested was characterized by second- or third-growth scrub. But the land was resilient and through the efforts of the park rangers, and lumber company and government fire rangers, the forests and lakes eventually recovered to the extent that people, especially those dwelling in the confines of cities and towns, began to consider it a wilderness of sorts.

During the new Park’s first two decades, two railways were constructed across it, and lodges sprang up alongside. In 1936, a public highway was opened through the southern portion of the Park. Both Park Superintendent George Bartlett and Park Superintendent Frank MacDougall made decisions to keep leases and other development out of the Park interior, in 1912 and 1931 respectively. In 1954, Park Superintendent George Phillips was quoted in a Maclean’s magazine article:

“It’s a battle without end ... To preserve a wilderness park you have to fight fires that would burn it up, bugs that would eat it up, lumbermen who would chop it down, poachers who would trap and shoot

it clean, fish hogs who would catch every fish, wolves that would catch every deer and businessmen who would turn it into a honky-tonk of dance halls and hot-dog stands.”

In 1961, Park Naturalist Grant Tayler, in a paper on Wilderness camping in Algonquin Park, wrote:

“From the beginning of ... recorded history, the Algonquin Highland country has been used for wilderness camping ... It was the way of life to the Algonquin, Iroquois, and trapper. Modern man ... has turned this way of life into a form of recreation which is attracting thousands more every year. Modern equipment has not only eased the comfort of camping and increased the carrying capacity of the average man, but increased the number of people capable of camping. If this newly found recreation is permitted to expand uncontrolled, it will eventually spell the end of the wilderness ...”

In 1963, George Priddle conducted research regarding wilderness perception among Park users and discovered they were not looking for a pristine wilderness. Logging was not considered a concern at that time, although there was evidence of its presence. Priddle wrote: the “biggest complaint by all interior users of the Park was the amount of garbage on the campsites and along the canoe trails.” So, in

1969 and 1970 attempts were made to solve the garbage problem. In Algonquin Park – A Place Like No Other we read:

“In 1969 over $70,000 was spent in cleaning up the garbage that had accumulated since 1893 ... Thirty men were sent out in the spring to clean up campsites ... In the autumn a special effort was made to collect older cans and bottles that had accumulated on the most heavily used routes. The interior maintenance crews gathered 10,000 bushels (352,390 litres) of garbage that had accumulated in the interior of the Park, and that was taken out by truck, boat, and Otter aircraft, and then transported to the incinerator [and for

28 ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022

“If this newly found recreation is permitted to expand uncontrolled, it will eventually spell the end of the wilderness ...”

Some of the garbage flown out of the Park’s interior campsites, about 1969. (Algonquin Provincial Park Archives and Collections, photo #3288)

otherwise appropriate disposal]. Beginning that year, yellow garbage bags were issued to interior campers so they could carry out their cans, bottles, and other non-burnable garbage.”

Throughout the 1960s, as more canoeists used the Park, the presence of logging had become more noticed. Other uses of Algonquin Park were beginning to come into conflict as well. Projections suggested that the number of visitors using the Park would almost double by 1975, so, in 1966, the Ontario government began to formulate a park plan based on Park Superintendent Frank MacDougall’s earlier concept of “multiple use.” A Provisional Master Plan was published in 1968. It included activity zones, meant to keep competing uses separated. The plan did not please everyone, but it was a start.

In September 1969, the Ontario government set out to produce a revised and improved Master Plan under the guidance and leadership of former Premier of Ontario Leslie Frost. In 1971, Leslie Frost commented to the Minister of Lands and Forests that the “principal problem of Algonquin Park is simply people.” Assisting Mr. Frost and Park Superintendent Bill Hueston in working with an Algonquin Park Advisory Committee of citizens and coordinating an Algonquin Park Task Force of government policy and research

Toadvertisein MuskokaLifeor ParrySoundLife Contactusatsales@metrolandnorthmedia.com MAY/JUNE2022 GOLFPARRYSOUND•TASTYBRUNCHRECIPES•BOATREVIEW:SYLVANMIRAGEX3CLZ ‘SILVER-WEAR’ Artisanbreathesnew lifeintooldcutlery TRANQUILTIMES andwildlifeencounters atBlindBaycottage Foxontherun Hideandseek ...withmom CATCHUPWITH ALGONQUINLIFE ONLINE ToviewourE-Editions. JUSTGOTO muskokaregion.com ForE-Editions,scrolltothebottom andclickon“E-Editions.” Yourhometown storeforallyour DIYprojects &more! (705)724-2810 489MainStreet,Powassan 19595OpeongoLine,Barry’sBay,ON (613)401-4595•evesescapespa.com ComevisitusatEve’sEscape foranexperiencetoremember! ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 29

specialists was William “Bill” Calvert. When interviewed in 2012 for the Algonquin Oral History Project, Calvert commented on the challenge of protecting the “wilderness”: “Algonquin is full of non-conforming issues: logging, hunting, fishing, cottages, youth camps. All of the non-conforming issues are wrapped into one.” Some people wanted all the non-conforming uses, especially logging, eliminated and Algonquin to become a wilderness park. Those hopes were dashed in July 1973 when Minister of Natural Resources Leo Bernier referred to the Park as the “Average Man’s Wilderness” and established the Algonquin Forestry Authority to supply logs to local sawmills.

A means of balancing the conflicting interests was addressed in the Master Plan, written in large portion by Bill Calvert and published in late 1974. Again, dividing the Park into activity zones was a key concept. Included in the plan were a large recreation/ utilization zone in which strictly managed logging and traditional recreation activities would co-exist, development zones, historic zones, natural zones, and wilderness zones in which nature would be relatively undisturbed. In a 1975 article to announce the plan, Calvert wrote:

“Algonquin Park should be a natural environment where people of average means can escape for a while from the increasing pressures of urban life ... The outstanding feature of Algonquin Park is that it places within easy reach of the vast urban population of northeastern North America a reasonable example of the wilderness that covered this land before it was occupied by Europeans. Even if the present forest is somewhat different from the original, the ‘feel’ of wilderness is still there, and it requires only a little imagination to visualize its primeval state.”

Calvert considered preservation of the Park interior to be the main goal, professionally and personally: “That’s the real Algonquin.”

The basic objective of wilderness management, as written in the Master Plan, “is to maintain natural conditions as the ruling principle to which all activities and uses shall normally be subservient ... To achieve this, only those facilities, uses and land treatment measures which protect the area, provide visitor safety and perpetuate or enhance natural conditions will be permitted.” To accomplish that, it was necessary to consider special requirements of recreation management, including those primitive types of recreational improvements and facilities which are necessary for sanitation, fire and site protection, and for the protection and safety of users. Campsites and campsite access would be unobtrusive and located on bedrock where possible.

When interviewed in 2012, Calvert’s canoeing and trails specialist, Craig MacDonald, recalled:

“My job was to try and look at the capacity of Algonquin Park to camp in the interior and what that required was a field examination of all the lakes on all the canoe routes ... So I have been around the shoreline of every island of every lake that’s on a canoe route ... We didn’t like campsites at portage entrances because it caused too much congestion ... We were going to have designated sites and we wanted an idea of the capacity.”

In September 1969, the Ontario government set out to produce a revised and improved Master Plan under the guidance and leadership of former Premier of Ontario Leslie Frost.

ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022

An objective of recreation management was also “to provide high quality recreational experiences in a natural setting to an optimum number of visitors and to control use to maintain and enhance the ... primitive character of the area.” To limit and more equitably distribute the impact of canoe trippers on the environment a quota system was introduced in 1976.

In 2012, Calvert said it was recognized by government that while some areas would exclude logging, others would include that necessary economic activity. As he had written in 1972:

“The special role that Algonquin must have within the social and economic fabric of the regional community has been identified ... Algonquin will continue to contribute to resource production activities in the region.

“However, the nature and amount of this contribution will depend upon the extent to which diversification of the economic base provides alternatives for the maintenance of the local communities.”

TheLakeside Smokehouse

restaurant

SpectacleLake Lodge & Lakeside Restaurant

makingmemoriestraditions

TheLakesideSmokehouseRestaurantat SpectacleLakeLodge,featurestheeverpopular‘smokerlicious’favorites allpreparedtoperfectionbyour talentedculinaryteam.

Enjoythespectacularviewof SpectacleLakefromourmulti-level DiningRooms,FiresideLoungeor SeasonalOutdoorPatio.

LODGEROOMS& LAKEFRONTCOTTAGES

OurAccommodationsandRestaurant offeryou a year-roundgetawaythat focusesonanenvironmentto rejuvenate themind,bodyandsoul.Special packagesforweddingsandeventstoo. SpectacleLakeLodgeislocated just35minuteseastof renowned AlgonquinProvincialPark.

www.spectaclelakelodge.com 202SpectacleLakeRoad,Barry’s Bay, Ontario 18005674044

ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 31

A young Bill Calvert camping in the Algonquin “wilderness” in the mid-1960s.

(Algonquin Provincial Park Archives and Collections slide)

It is very much to Bill Calvert that we owe thanks for what specific parts of Algonquin Park are set aside from other activities to this day, as “wilderness.” In 1969 he wrote, “The ‘true’ value of the Park lies in the aesthetic, inspirational, and biological aspects of the wilderness environment.”

As chief architect of the Master Plan, Calvert personally pored over maps to delineate each area to be protected. When interviewed, he recalled: “You just wanted to do a good job on behalf of the Park. You had a window of opportunity to be one of the lead stewards in a fantastic place ... Algonquin Park is the, to my mind, the most accessible and finest wilderness area in eastern North America ... It’s because of the accessibility of the Park,” compared with the mountain parks that require special skills for travelling. “You think of the vast numbers of people in eastern North America ... this is it!”

Calvert commented about one of his toughest decisions:

“Probably when it came down at the end of the day [it was] sort of drawing the lines on the wilderness zones, or then primitive zones. Now I thought, ‘I’m protecting this lake, and this lake isn’t.’ That bothered me a bit. You sort of make the decision, ‘Well, am I going to make the decision and sell it and if I don’t, somebody else is, and if I know somebody that’s better qualified, go and ask them now’ ... It wasn’t that difficult but it gave me more pause than anything else.”

In the end, there was nobody else with as much experience in the Park to make those determinations. Calvert’s painstaking decision-making resulted in the wilderness zones that can be seen by all, laid out on the official Park map produced by The Friends of Algonquin Park.

Calvert hoped his lasting legacy will be that areas of Algonquin Park will continue in their natural state as wilderness. He said, “Whatever you protected here in the hope that it will continue ... if you were able to look forward a hundred years, what’s still going to be in place, it’s likely to be the zoning and what you protected.”

When interviewed in 2014, former Park

Superintendent John Winters said:

“If you go back to the 1974 Master Plan, in its era and even to this day, I think it was a brilliant piece. The one thing it ... says [is] that [regarding] the interior of the Park, you are only going to get there by hiking or by canoeing. You’re going to get this wilderness experience ... I say what they wrote was truly brilliant when you look at the principles of a protected area.”

The 1998 Management Plan updated the previous Master Plan, and included in its protected areas the 25,000 hectare LavieilleDickson Wilderness Zone that had been established by the government in 1993. In 2006, the Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act echoed a decades-earlier call to return parks to their natural state as much as possible, emphasizing the role of “ecological integrity.” In 2011, a memorandum of understanding adopting the Leave No Trace program was signed by The Friends of Algonquin Park, Ontario Parks, and an organized group of backcountry recreationists.

In 2013, after six years of discussion by the Algonquin Forestry Authority, the Algonquins of Ontario, Ontario Parks, and other stakeholders, “A Joint Proposal for Lightening the Ecological Footprint of Logging in Algonquin Park” was added as an amendment to the Management Plan. Wilderness Zones were increased from 11.9 per cent to 13.7 per cent, Nature Reserve Zones were increased from 5.8 per cent to 6.8 per cent, and Natural Environment Zones were increased from 1.8 per cent to 10.9 per cent, with a corresponding decrease in the Recreation/Utilization zone, in which logging could take place, from 77.9 per cent to 65.3 per cent.

Although logging still plays a role in the Park, the wilderness-like zones, with their sense of wildness, have gained much ground since zoning was first proposed. Now, under the Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks, the managers and staff of Ontario Parks continue to work at saving the Algonquin Park back country’s sense of wilderness for future generations.

Bill Calvert helped make official

the tradition of keeping the interior of Algonquin Park wild. He was a family man, well-respected for his many accomplishments and leadership in provincial and municipal government service. As a volunteer, he was the lead instigator in spearheading the formation of the Friends of Algonquin Park non-profit charitable organization, before its inception in 1983. One of Bill’s favourite sayings was “move the yardsticks,” and he was extremely adept in doing just that as the first Chairman of The Friends of Algonquin Park from 1983 to 1993.

Quite sadly, Algonquin Park lost one of its most significant friends and protectors of wilderness when William C. Calvert passed away in March 2019. (This is just one of many stories about Algonquin Park to be found among the historical documents held in the Algonquin Provincial Park Archives and Collections.)

Roderick MacKay is author of books on Algonquin Park history, including Algonquin Park – A Place Like No Other: A History of Algonquin Provincial Park; Spirits of the Little Bonnechere: A History of Exploration, Logging, and Settlement, 1800 to 1920; and A Chronology of Dates and Events of Algonquin Provincial Park. All three titles are available from The Friends of Algonquin Park bookstore at the Algonquin Visitor Centre or online.

ALGONQUIN LIfe 2022 33

Bill Calvert, July 2017. (Photo courtesy of Erin [Calvert] Simpson)

Kichisippi

Pimisi The

TheKichisippi Pimisi

BY CHRISTINE LUCKASAVITCH

BY CHRISTINE LUCKASAVITCH

American eels (Anguilla rostrata) are a remarkable fish that was once extremely abundant throughout tributaries to Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River, including the Ottawa River and its tributaries. Within the Ottawa River watershed, this species has experienced a dramatic 99 per cent decline in population since the 1980s. American eels have been extirpated from many parts of its Ontario range and is in serious decline where they are still present. They are now listed as endangered under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007.

American eels (Anguilla rostrata) are a remarkable fish that was once extremely abundant throughout tributaries to Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River, including the Ottawa River and its tributaries. Within the Ottawa River watershed, this species has experienced a dramatic 99 per cent decline in population since the 1980s. American eels have been extirpated from many parts of its Ontario range and is in serious decline where they are still present. They are now listed as endangered under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007.

ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 1

Younger generations will not have the opportunity to hold a connection with this fish that was once so integral to our lives as Algonquin people.

ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 1

The author holding an American eel. (Photo courtesy Christine Luckasavitch)

Younger generations will not have the opportunity to hold a connection with this fish that was once so integral to our lives as Algonquin people.

34 ALGONQUIN LIfe 2022

The author holding an American eel. (Photo courtesy Christine Luckasavitch)

The American eel is known to Algonquin people as Kichisippi Pimisi, which translates to “big river eel.” Algonquin Traditional Knowledge (ATK) states that Kichisippi Pimisi have been an essential part of Algonquin culture since time immemorial as a provider of nourishment, medicine and spirituality.

Pimisi were once extremely plentiful across Anishinaabeaki (Anishinaabeg territory), making up 50 per cent of all fish biomass. They were one of the most important and dependable sources of sustenance, particularly during long journeys and harsh winters. Oral knowledge states that eel were once so plentiful that over a thousand could be caught in an evening – enough to sustain an entire village.

The skin of Kichisippi Pimisi has healing properties and can be used as a cast or brace for broken bones or sprains and to rid the body of infections once dried. Oral knowledge also suggests that Pimisi skin has the ability to heal sore throats when applied to one’s neck.

American eels are born in the Sargasso Sea in the Caribbean and travel along the shores of the Atlantic on ocean currents as they grow. Once they reach brackish water (a mix of fresh and saltwater), female eels continue travelling far into river tributaries where they will stay until sexual maturation (which can be as long as 30 years). Once they have reached this point in their life cycle, they begin to migrate toward the ocean and back to the Sargasso Sea where they will mate, thus restarting the life cycle of the American eel.

Across Anishinaabeaki, most rivers are

no longer free-flowing due to hydroelectric facilities. As only female populations of eel travel deep into tributaries throughout the Kitchisippi (Ottawa River) watershed, female eel populations face an almost certain death they pass through the turbines of hydroelectric dams as they make their way back to the Sargasso Sea to breed.

The cumulative effects of eel mortality during outward migration are truly devastating. Hydroelectric facilities, reduced access to habitat imposed by man-made barriers throughout waterways, commercial harvesting in jurisdictions other than Ontario, contaminants and habitat destruction, alteration and disruption are amongst the most significant threats to the survival and recovery of Kichisippi Pimisi in Ontario.

This high mortality rate has led to a severe impact on the presence of Kitchisippi Pimisi throughout Algonquin territory. Our younger generations will not have the opportunity to hold a connection with this fish that was once so integral to our lives as Algonquin people. It is vital that Kichisippi Pimisi be restored to its historical range to re-establish the ancestral connection between Algonquin people and Kichisippi Pimisi.

Taking steps toward reconciliation with Indigenous peoples also means extending respect and support to other-than-humanbeings – fish, rocks, trees, water, and all others – who also call this place home. Advocating for safe eel passages around hydro dams will support a resurgence of Kitchisippi Pimisi populations across our ancestral territories. For additional reading, go to cwf-fcf.org/en/explore/eels/

Christine Luckasavitch is an Omàmìwininì Madaoueskarini Anishinaabekwe (a woman of the Madawaska River Algonquin people), belonging to the Crane Clan, and mixed settler heritage. Christine continues to live in her ancestral territory, much of which is now known as Algonquin Park, Ontario. She is the owner of Waaseyaa Consulting and Waaseyaa Cultural Tours, the co-owner of Algonquin Motors, and the Executive Director of Native Land Digital, the organization behind NativeLand.ca. Her work centres around creating safe and respectful spaces for Indigenous voices.

ALGONQUIN LIfe 2022 35 2 ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022

The release of 400 American eel at Fitzroy Harbour – an initiative between Canadian Wildlife Federation, MNRF and the Algonquins of Ontario in 2014.

(Photo courtesy Christine Luckasavitch)

The American eel is known to Algonquin people as Kichisippi Pimisi, which translates to “big river eel.”

Paddling her own canoe

The Algonquin journey of guide Esther Keyser

When Esther Keyser became Algonquin Park’s first female canoe guide in the early 1930s, backcountry camping was a new concept and guiding was a male domain. Keyser inspired generations of canoe trippers and became part of the Park’s history.

STORY BY PATTI VIPOND | PHOTOS COURTESY

STORY BY PATTI VIPOND | PHOTOS COURTESY

Whether by nature, nurture or some other decisive influence, Esther Sessions Keyser adored being outdoors very early in life. At 10 years old, she did her first solo camping trip at Arkwright Hills Campground near her hometown of Fredonia in western New York, U.S.A.

Esther’s singular desire to be alone and commune with nature foreshadowed the weaving of her life into the fabric of the history of Algonquin Park as its first female canoe guide. It was the

36 ALGONQUIN LIfe 2022

KEYSER FAMILY

Keyser’s son John believes the spiritual essence of Algonquin Park kept Esther paddling through her 80s, stopping only during her husband Joe’s final illness.

summer of 1927 when she entered the Park for the first time as a teenaged camper at Northway Lodge on Cache Lake. Esther always said she fell in love with Algonquin at first sight.

“There were exciting people at Northway that stimulated her visions for her own future like founder Fanny Case and guide Charlie Skuse who was an old woodsman who taught the campers how to build a fire and go fishing,” recalls John, Esther’s second child with husband Joe Keyser, who she called Minawaska. “I think she just fell in love with the landscape, the water and the richness. It was a wonderful window through which she developed a very spiritual connection early on with the Park. The spiritual essence of the place kept her coming back to the trails until she was 88, and keeps us coming back now.”

In 1932, Esther was the 17-year-old executive director of the Northern Chautauqua Council of Girl Scouts. Though the pay was low, she had the summer months off to canoe and camp. Two years later, she was running a professional guide business in Algonquin. Wilderness camping was a new activity to the public and usually helmed by male guides. Esther’s first clients were groups of women eager to try backcountry canoeing. When

demand for co-ed canoe trips began, she led them as well.

“She had an inner confidence and strength,” recalls John. “She always had a high level of comfort being by herself in nature.”

“She knew who she was and what she wanted,” adds Amber Keyser, John’s daughter and Esther’s granddaughter. “Esther and I shared a real love of explorer narratives. We would pass books back and forth about Shackleton going to the South Pole and Sir Edmond Hillary. There was a huge element of men doing what they did for fame or glory. That was not what drove Esther. She did what she did for her soul, her heart and her happiness. She never would have done it to be a role model for future generations, though she has inspired and motivated many of us. She had a core sense of knowing who she was and what she wanted. It was profound enough for her to do things people said she shouldn’t or couldn’t.”

Esther secured a land lease on

Algonquin’s Smoke Lake and built a cabin to store supplies, canoes and other necessities for her guided trips. A small addition was added in the 1940s to accommodate the couple’s three children. That same cabin, still without electricity, running water or indoor bathroom, is where John’s family heads most summers to use as base camp for their multi-day back country canoe trips.

Esther’s brother Manley, the first in the family to come up to Algonquin, built a cabin next door. His doctor had recommended a trip to the Park to rid Manley of asthma. His condition improved and he decided to make Algonquin his summer home.

With the Keyser legacy now embedded in four generations at the lake, John’s family keeps the cabin despite ongoing land lease fee increases and the long trip from their home in Oregon in the States. John and his wife Marilynne’s five grandchildren call it their favourite place.

Despite being the Park’s first female guide, Esther doesn’t trumpet that

ALGONQUIN LIfe 2022 37

TOP LEFT: When Keyser started her professional guide business in Algonquin in 1934, her first clients were groups of women wanting to explore the new activity of back country canoeing. TOP MIDDLE: During the summer of 1927, Esther Sessions travelled to Algonquin Park for the first time as a teenaged camper at Northway Lodge on Cache Lake. BOTTOM MIDDLE: Keyser had a beautiful view of Algonquin Park’s Smoke Lake from the front porch of her rustic cabin, a Keyser family retreat that still has no hydro or indoor plumbing. TOP RIGHT: Esther and her husband Joe, an outdoor educator who founded a camp at the State University of New York at Fredonia, were bonded throughout their marriage by a love of outdoor living.

“There was a huge element of men doing what they did for fame or glory. That was not what drove Esther. She did what she did for her soul, her heart and her happiness.”

accomplishment in Paddling My Own Canoe, her popular memoir, co-written with John. Respected for being honest and non-judgmental, Esther was also known for her low-key modest personality. John needed to convince his mother that her unique life was book-worthy.

“We pushed her to get it together because we knew it was a fascinating story,” recalls John. “It was during the latter years of her life. She was running out of energy so the idea of doing a book was imposing. She had archives of her poetry, paintings and trip logs that made a rich landscape to draw upon. I was in Oregon and she was in Utah. I would write a draft chapter and send it to her or go down and visit. Once we started, she really got into it, changing things around, putting it in her own words. We had a lot of fun with it.”

Every summer, canoe trippers who have read the book arrive at the dock of the Keyser’s Smoke Lake cabin to ask if this is where Esther lived and talk to those who knew her.

“They are very interested in how Esther cooked and baked over an open fire, where and how she caught fish, and her favourite campsites,” says John. “Canoe trippers are hungry for that kind of information.”

On their canoe trips, the Keysers often stay at campsites built over 60 years ago by Esther. Arriving at Birch Point, Esther’s creation and her favourite campsite, on Big Trout Lake is like a homecoming. A few years ago, Amber was sent a photograph taken at Birch Point a few months after Esther’s death in February 2005. Someone had taken charcoal from the fire and written ESK RIP on the rocks.

“We have camped at Birch Point many times and there’s a resonance of all those experiences we shared with Esther and our family,” says Amber. “That’s powerful, that idea of connection to place. It’s something she instilled in all of us. My kids, nieces and nephew feel that same connection though they never knew Esther.”

Her grandmother hugely inspired Amber. She remembers Esther as being profoundly feminist and a generous person who valued her life enough to put her needs in a primary position. Esther also taught her grandchildren to live simply.

“My parents believed in living below your means like today’s voluntary simplicity movement,” says John. “Don’t over consume, live quietly and gently with nature as a partner and not as a dominant exploiter. Respect for nature was modeled from the time we were small.”

“Grandma Esther always saw herself as a

38 ALGONQUIN LIfe 2022

Arriving at Birch Point on Big Trout Lake – Keyser’s favourite campsite of the many she built –always feel like a homecoming to her family on their canoe trips.

The cabin Keyser built on Smoke Lake to store supplies for her guided trips is still used most summers by her son John’s family as a base camp for their multi-day back country canoe trips.

ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 4

DEET FREE (ASALWAYS)

DEET FREE FAMILY FRIENDLY

FAMILY FRIENDLY

GENTLEONSKIN

GENTLEONSKIN

NEVEROILY ORGREASY

NEVEROILY ORGREASY

AVAILABLEAT:

UPTO 12 HOUR PROTECTION UORP D LYMADE IN C A

ADAN

com

5 ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022

steward of this land and felt it was a privilege and a blessing to be there,” adds Amber, whose children’s book Paddle My Own Canoe is based on Esther’s life. “She certainly recognized the primary right of First Nations and the importance of conservation. I think she gave that sense to all of us that being able to walk, however momentarily, in this space is profoundly important. We have this sense of needing to be good stewards of this land.”

John describes his father as an outdoorsman of the first level. Joe was an outdoor educator who founded a camp at the State University of New York at Fredonia. While Joe was operating this camp, Esther was operating Girl Scout camps in New York State. Both had outdoor living in their blood and it was a bond throughout their marriage.

“I think my father realized my mother had values that connected her to people,” John recalls. “She was an effective leader because she was a very good listener and led by example.”

John believes it was the spiritual essence of Algonquin Park that kept Esther paddling through her 80s. Though she stopped going on canoe trips during her husband’s final illness, Esther paddled again after his passing. Her last canoe trip in 2003 was the first one for Amber’s new baby son. Four generations of Keysers went on that trip together.

“There was my grandmother, parents, husband and my little baby and it was amazing,” recalls Amber. “Esther has had an outsized influence on my life. In my childhood memories, it feels like I spent every summer at the cabin. In fact, it was probably only two weeks every other year.”

When Esther chose her land lease on Smoke Lake, two white pine saplings swayed her decision. The small trees had escaped loggers when the rest of the lake’s forest was cleared. The pair of pines frame the cabin’s entrance. When John looks at them, he thinks of the ritual his mother did when arriving and leaving. She hugged both trees, and her family still does.

Paddling My Own Canoe by Esther S. Keyser is published by The Friends of Algonquin Park, with all proceeds supporting Algonquin Park. For more information or to order, visit store. algonquinpark.on.ca/cgi/algonquinpark

MIDDLE: Esther and Joe’s kids John (centre) and Joe (right), and later daughter Beth, joined their parents on canoe trips and trail hikes in Algonquin Park from infanthood. BOTTOM: In 2003, the first female guide in Algonquin Park made her last canoe trip at the age of 88, accompanied by three generations of Keysers, including granddaughter Amber’s new baby son.

ALGONQUIN LIfe 2022 41

Esther and Joe’s kids John (left), Beth (centre) and Joe (right) joined their parents on canoe trips and trail hikes in Algonquin Park from infanthood.

42 ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022

Banished Removed and

BY RODERICK MACKAY

BY RODERICK MACKAY

Algonquin Park was established in 1893, in an area of the province of Ontario that was unsuitable for settlement and therefore largely unsettled. Through the years, Algonquin Park grew in size, to its current area of 7,632 square kilometres. In the process, for a few farming families there was a human cost, fortunately only in lives changed, not lost.

Previously in Algonquin Life (2019), we read about the Algonquin people who lived along the Madawaska River, now within Algonquin Park. They and their ancestors lived off the land, trapped, and hunted in that territory for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. In 1868, Chief Somogoneche, who had lived on Galeairy Lake since at least 1854, asked for reserve lands for the Algonquins in nearby Lawrence Township. He was refused.

Although legal title to the land could not be obtained by the Algonquins, that did not stop their use of the land. By the

In 1914, four “settler” families were forced to leave their clearings and cabins when the Algonquin Park boundary was extended eastward

ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 43

John McGuey (left) and Dennis McGuey, and hunting dogs at the Basin Lake farm. (Algonquin Provincial Park Archives and Collections, photo #3718)

1878 survey of Nightingale Township, indigenous farmers Peter Charbut and Joseph Francis had cleared farms within the township, on Galeairy Lake and at the head of Rock Lake respectively. In 1911, land was added to Algonquin Park, comprising most of Lawrence Township and Nightingale Township. Thirty-two Algonquin families using the townships for hunting or settlement were required to cease those activities and leave.

The Algonquin of the Madawaska were not the only people to be removed to make way for Algonquin Park. In 1914, four “settler” families were forced to leave their clearings and cabins when the Algonquin Park boundary was extended eastward; taking in the equivalent of eight townships, including Guthrie. ln Spirits of the Little Bonnechere we read:

“Fortunately we know a great deal about the lives of some of these settlers, relatively speaking, because of the author’s fortune in the mid-1970s of having met and

interviewed five former residents of this area: Peter and Henry McGuey and their sister Hannah Hyland, as well as Mary Garvey and her brother Mike. All had spent their childhood on the Little Bonnechere, and all appeared to have excellent recall of memories ... ”

Unfortunately, at the time I knew of no descendants of Tom O’Hare or the widow McDonald to interview. What little information I could glean about the families eventually came from other sources.

In 2020 it is quite difficult to locate the old farm clearings, but back in 1913 Paddy Garvey, Dennis McGuey and the widow of Ronald McDonald each had large farm clearings and proper houses, then easily seen from busy sections of the Bonnechere Road. Tom O’Hare’s holding was smaller.

Tom O’Hare, possibly of Sligo, Ireland, and his wife Bridget Kelly moved to the Bonnechere, about 1906. Tom was a brother to Mrs. McDonald, whose farm was just up the road. According to Hannah Hyland,

Tom O’Hare worked for a lumber company and lived on a small clearance, inside what was to become Algonquin Park, “maybe a mile or a mile and a half from the park gate.” The O’Hares became part of an existing community stretched out along the Bonnechere Road. As with the three other settlers occupying land in the Township of Guthrie, Tom and Bridget O’Hare did so as squatters (without legal ownership of the land). The townships taken into the Park were never opened for settlement.

The McDonald farm was on the north side of the Bonnechere Road, at Sligo, where the Bonnechere River can be seen in close proximity to south of the modern road, about two kilometres inside Algonquin Park. It is known that others had lived previously in the small squared log building, and may have farmed the land before the McDonalds. Photographs of the building are few. One image was taken by John Joe Turner from across the river about 1930, when he lived in the house. Fortunately the photograph was provided for copying in 1980, as the original was later lost when a new wife of one of Turner’s sons “cleaned house” and burned many family photographs.

Garvey farmhouse and outbuildings. (Algonquin Provincial Park Archives and Collections, photo #1976.14.1)

Garvey farmhouse and outbuildings. (Algonquin Provincial Park Archives and Collections, photo #1976.14.1)

44 ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022

Paddy Garvey, said to be of Sligo, Ireland, came to work in the square timber firm of John Egan, arriving on the Bonnechere about 1855. Years later, he took up farming on the west side of an uphill stretch of the road running north-south, near the north end (about km 13.5 on the Basin Road). It was a large farm, stretching from the road to the river, with the house and barns within 50 metres of the modern road. I remember asking Mary Garvey what the house looked like when I interviewed her in 1976. She attempted to describe it in detail, but eventually brought out a black and white photograph. Only reluctantly did she agree to it being copied, because she was embarrassed about the washing hanging on the fence line.

The McGuey farm, at Basin Lake, just north of Basin Depot (about km 14.2 on the Basin Road) was on a road along which supplies were taken north to logging camps on Grand Lake. Another farm, cleared about 1875 by Frank Foy and on which the McGueys had previously lived and still grew crops in 1913, was upstream on the Bonnechere River along a then lessused section of the Bonnechere Road. The McGuey family had moved down to Basin Lake about 1906.

No photograph or specific location of the O’Hare clearing has yet been found, although John Joe Turner gave some clues: “Down on this side of Sligo, when you cross the creek there, there’s a little clearing on the left hand side. I think they have it planted with trees now. He built a place there and that was known from that time as the O’Hare place ... ” When he was interviewed in 1976, Turner was likely recalling the clearing as it was in the 1930s, when he worked as a park ranger. About that time old settlers’ buildings were being demolished and their clearings were being planted in pine, for in 1914 the settlers all

Kioshkokwi L Kawawaymog L Opeongo L Cedar L Petawawa R Bonnechere R Kamaniskeg L Golden L Round L Lake of Bays SCALE 10 520 40 Km Ottawa River HUNTSVILLE DORSET MADAWASKA WHITNEY PEMBROKE 60 1893 1894 1894 1904 1914 1911 1951 1951 1963 1993 1960-61 1978 1978 1978

TOP: Expansions of Algonquin Park over the years 1893 to 1993.

(From Algonquin Story, Second Edition, The Friends of Algonquin Park) BOTTOM: Farms of the settlers in Guthrie Township in 1913.

ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 45

(Detail of map from Spirits of the Little Bonnechere, 1996 edition.)

Back in 1913 Paddy Garvey, Dennis McGuey and the widow of Ronald McDonald each had large farm clearings and proper houses, then easily seen from busy sections of the Bonnechere Road.

had to leave their homes and start again elsewhere.

As explained by the writer of an article in The Eganville Leader of May 29, 1914: “The Ontario government is gradually getting rid of the settlers in Algonquin Park. At the headwaters of the Bonnechere and the Petawawa Rivers in that portion of territory which is within park limits, there are a few yet remaining and with the purpose of buying the properties of these settlers for the government the Superintendent of the Park, Mr. Bartlett, visited the parties interested and secured their prices. Mr. Bartlett will probably recommend that these properties be bought. Among the settlers affected are: Messrs. Dennis McGuey, Paddy Garvie [sic], John [sic] O’Hare, and Mrs. Ronald Macdonald [sic].”

The Guthrie Township squatters had much work invested in their farms. By 1914, Paddy Garvey had lived along the Bonnechere Road for over 49 years, only marrying his wife Augusta in 1884.

They raised seven children there. Dennis McGuey and his wife Margaret and their children had lived on two different farm sites along the road for 34 years. They raised nine children there. James McDonald and his brother Ronald (who died in 1906), and Ronald’s widow Catherine and their family had lived for 30 years at Sligo, where the river runs just beside today’s gravel road. They had five children, one of whom is buried there. Tom and Bridget O’Hare were relative newcomers, with only eight years as settlers on the Bonnechere Road. They raised a daughter.

When they learned they were being evicted, both Dennis McGuey and Paddy Garvey corresponded with government officials in an attempt to get adequate compensation for their properties, or if possible to retain use of the land. Dennis McGuey wrote: “I have been a fire ranger over 25 years. If only I could be left here I would be quite content ... Or you might appoint me park ranger. I know this country well. I know the hunters’ trails,

where they go into the park. This is a good place to watch them. I can do my duty in that line all right.”

In 1976, Dennis McGuey’s daughter Hannah recalled the day Superintendent Bartlett visited their farm:

“He just came along one day and told Dad and Mother that the park was taking over the township ... and Dad says, ‘Well I’m not going out.’ They said ‘You’ve no claim on this land. You’re a squatter ... You’ll just have to go.’

“And Dad said, ‘I won’t move.’ And they said, ‘What are you going to do if you won’t move? What are you going to live on?’ Dad said, ‘The same as we always did.’ But [Bartlett] said they wouldn’t let him work the land. He said the government owned the land ... The wild hay belonged to the government. He just told [Dad] they’d starve us out. He told Paddy Garvey and them [sic] all the same story, you know. He went around and told everybody the same thing. We had to get out.”

We learn from Hannah the strength of

McDonald farm as photographed in 1930, when J.J. Turner lived there. (Algonquin Provincial Park Archives and Collections, photo #5692)

McDonald farm as photographed in 1930, when J.J. Turner lived there. (Algonquin Provincial Park Archives and Collections, photo #5692)

46 ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022

the settlers’ hard feelings: “We wanted to have a civil war and [have] everybody get out their guns ... ”

Again turning to Spirits of the Little Bonnechere, we read: “The pleas were of no avail, however, and it was reported [in the annual report for Algonquin Park] that ‘the four settlers who squatted in the Township of Guthrie have been satisfactorily settled and are leaving their places.’” According to Park Superintendent J.W. Millar, writing in 1928, Tom O’Hare received the sum of $500 as compensation for the burning of his house and barn by the government. Settlements for the larger clearings and structures amounted to $1,800 for Patrick Garvey, $1,100.00 for Dennis McGuey, and $1,200 for Mrs. McDonald.

Patrick Garvey and his family moved to Renfrew and shortly thereafter to Killaloe. Dennis McGuey and his family moved to farmland just south of Whitney. It is believed that Mrs. McDonald and her family moved to Killaloe. Tom and Bridget O’Hare and their daughter moved to Killaloe.

That just about cleared the Park of would-be occupants, with the exception of the Algonquin DuFond family living on Manitou Lake. But for a mining claim they took out in 1888, they likely would have been banished in 1893, but the old people of the family, Ignace, Francis and his wife Suzanne, were permitted to remain in the Park until 1918. Perhaps that is a story for another time.

This is just one of many fascinating stories to be found among the historical documents held in the Algonquin Provincial Park Archives and Collections.

Roderick MacKay is author of books on Algonquin Park history, including Algonquin Park – A Place Like No Other: A History of Algonquin Provincial Park; Spirits of the Little Bonnechere: A History of Exploration, Logging, and Settlement, 1800 to 1920; and A Chronology of Dates and Events of Algonquin Provincial Park. All three titles are available from The Friends of Algonquin Park bookstore at the Algonquin Visitor Centre or online.

BookNow! SteamshipCruises•DiscoveryCentre www.realmuskoka.com/1-866-687-6667 MuskokaWharf,Gravenhurst AUTHENTICMUSKOKA History•Environment•Sustainability •Lumber•BuildingSupplies•Hardware •PlumbingandElectrical•Propane •Paints/Stains•ToysandGifts •GardenCentre •BottledWater•BottleReturn Magnetawan“IntheHeartof theAlmaguinHighlands” ProudlyCanadian 705-387-3988 1-866-582-3988 E-mail:magnetawanbuilding@bellnet.ca Monday-Saturday85ClosedSundays GreatPrice FriendlyAdvice Sendalittlepiece ofMuskokaasa thankyougift! Appreciationgift! Congratulationsgift! Checkout themuskokagiftbox.com andletusdeliverforyou. ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 47

Photographers get ready to HOWL

Professional and hobbyist nature photographers will gather at the Howl Wildlife Photography Convention in October for its usual slate of world-class speakers, Algonquin Park field trips, live music and camaraderie.

BY PATTI VIPOND

BY PATTI VIPOND

After being cancelled in 2020 and 2021 courtesy of the pandemic, the second Howl Wildlife Photography Convention will happen on Oct. 21-23 in Whitney.

Howl Convention founders Steve Dunsford, a wildlife/nature photographer, and “Bongo,” a South Algonquin Township councillor and owner with wife Andrea of Camp Bongopix, will ensure the convention is safe for nature photographers and featured speakers coming to Whitney, a scenic town nestled beside Algonquin Park’s Eastern Gate. Howl’s itinerary includes wildlife photo forays into the Park, fabulous meals, musical evenings and a group of renowned international wildlife photographers as

speakers.

Howl will open on Friday evening with speaker John E. Marriott, a renowned author and ethical nature photographer from Alberta. On Saturday, the convention’s itinerary includes guided nature hikes in Algonquin Park and an interactive Q&A panel featuring speakers Sandy Sharkey, a world-renowned wild horse photographer, and Connor Thompson, a wolf biologist at the Algonquin Wildlife Research Station. Saturday night’s featured speaker is writer/ photographer and conservationist Melissa

Groo from upstate New York.

Early Sunday morning, participants will grab their cameras for a wildlife outing in the Park. A presentation by outdoor educator and wilderness guide Chris Gilmour will end the convention on Sunday afternoon. Speaker presentations will be at the Lester B. Smith Community Centre and all meals will be served at the Mad Musher Restaurant. Nightly music jams will happen at the outdoor campfire venue, Bongopix Tavern.

The idea for the Howl Convention started

2022in 48 ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022

with Bongo. After buying an old Whitney cottage resort in 2015 and renaming it “Camp Bongopix,” the former wedding photographer’s quest was to hold events there. His mission resulted in Saturday jam nights and the annual Black Fly Festival. In early 2018, he noticed lots of nature photographers stayed in Whitney for quick access to the Park. Why not hold an event for photographers? Dunsford agreed and offered to help him to create a roster of food, speakers and outings. After almost a year of meetings, the first Howl Convention

happened in October 2019.

“Our main objective was to create an event that would bring like-minded photographers together, from beginners to professionals, for networking, inspiration, good food, music and trips into Algonquin Park,” explains Dunsford. “By having a small group of people, everyone can meet each other. At the first Howl, there was a lot of interaction and new friendships. Many photographers now follow each other on social media.”

Photographers tend to work alone,

“Our main objective was to create an event that would bring like-minded photographers together, from beginners to professionals, for networking, inspiration, good food, music and trips into Algonquin Park,”

For photographers wanting an entirely different photography experience, Dunsford recommends experiencing the special serenity and starry skies of Algonquin Park at night.

For photographers wanting an entirely different photography experience, Dunsford recommends experiencing the special serenity and starry skies of Algonquin Park at night.

ALGONQUIN LIFE 2022 49

(Photo by Steve Dunsford)

but are a gregarious group when they get together. To keep things interesting, Dunsford and Bongo decided not to have guest speakers simply present their photos. Instead, the first Howl featured a mix of speakers like Randy Mitson talking about using marketing and social media, and Mark Peck, who is manager of the Schad Gallery of Biodiversity at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto.

Dunsford moved to Whitney 26 years ago when a friend who owned the Algonquin East Gate Motel wanted to semi-retire and asked for help with the place. For Dunsford, life in Whitney led to love and marriage to Dee Clarke, an Algonquin Park Warden and Interior Group Leader. Dunsford practised photography while working variously at the LCBO, as a canoe guide and, for seven winters, as a guide at a dog sledding company in Bancroft.

Tragically, his wife Dee died in January 2001 after the trail groomer she was riding in went through the ice on a lake in Algonquin Park. Not knowing what to do next, Dunsford took up a friend’s offer of a trip to India that July. It was a trip the friend had previously wanted to take with the couple.

“Looking back, it was an incredible trip,” recalls Dunsford. “We went on an 11-day trek through the Himalayans. I had a DSLR camera and took photos the whole time. At the 20,000-foot pass, all you could see was snow-capped peaks. I left a photo at that pass of Dee holding onto a moose as they were collaring him. I also left some prayer flags. Those are flags put up by Buddhists to send prayers and messages to heaven.”

Dunsford continued to travel to Ireland, Morocco, Spain and the USA while trying to figure out a new course for his life. When he finally came home to Whitney, the Parkland Restaurant was for sale. Though he had never even worked in a restaurant, Dunsford bought it. The eatery became The Mad Musher.

“The first few years were difficult because I had no clue what I was doing, but I figured it out,” chuckles Dunsford.

The photographer bought his first camera with 100 bubble gum wrappers and 50 cents when he was a kid in Los Angeles.