Co-Architecture : Architecture in Service of Community

Co-Architecture : Architecture in Service of Community

MMUNITY CO-

PRODUCER

TUTORS

4M2H: Muddy and Motley Mass Housing for the Millions of Homes Studio

K TH School of Architecture SE-100 44 Stockholm Sweden

Erik Stenberg, Associate Professor Frida Rosenberg, Adjunct Teacher

TABLE OF CONTENTS

STUDENTS

INTRO CONTEMPORARY CO-ARCHITECTURE

PROTOTYPES

THEMES CO-HOUSING

HOUSING TYPES

STUCTURALISM FLEXIBILIT Y

APPENDICES

SOURCE REFERENCES

COURSE LECTURES

4–5 6–9 10–11 12–13

68–69

122–123

14–15 156–157 196–205 206–209

STUDENTS

HOUSING TYPES

Erik Sandsten

Kamil Kowalski

Stellan Gulde

Tina Franc

STRUCTURALIS M

Alice Nilsson

Anton Valek

Julia Thiem

Rei Mark Seares

Stina Edlund

CO-HOUSING

FLEXIBILITY

Carl Ludovic Petersen

Elin Lennartsson

Adrian Andersson Martvall Bisrat Assefa Erik Karlsson

Hedvig Aaro

Frida Wollberg

Mattias Månsson

Nada El Kateb

Fredrik Skyllbäck Rebecca Wahlström

Studio visit to Cederhusen, Hagastaden by Folkhem and GA in May, 2021

Studio visit to Cederhusen, Hagastaden by Folkhem and GA in May, 2021

INTRODUCTION

In what ways does architecture make it possible to live together and how has this been tested in a variet y of housing formats throughout histor y from the early 18th centur y to the recent past? In front of you is an investigation into the range and depth of “co” in mass housing

architecture hasn’t been used more frequently in describing how architecture, beyond its t ypological limits, has formed spaces, places, and processes serving the communities we inhabit.

In Webster’s (unabridged) Twentieth Centur y Dictionar y of the English Language (New York 1938) “co-” is a

most commonly used is based on the idea of combining and the second, from mathematics, based on the action of complementing

When applied to architecture, “co” has historically been channeled into the concepts of communit y, commune, or common. These are all words that

together, in conjunction, jointly” but with different connotations. One way to distinguish between these intertwined words is to see the latin word communis (common) as the base, out of which communitas (community, fellowship) grows and subsequently commune (district or members) emerges. These concepts of “co” have been formed into a number of rich and diverse architectural t ypologies from the nineteenth centur y communities such as Godin’s familistère and the Shakers, to early twentieth centur y cooperative co-housing experiments, and reemerging in contemporar y discourse as co-living and co-working trends.

Both terms, combining and complementing, are useful in analyzing, understanding, and designing mass housing architecture where many individuals live together and by choice or default form social relations.

We have tried to take an ever more inclusive and broad perspective on coarchitecture as that component in mass housing which makes architecture social and in the service of communis. In doing so, we have gathered an even longer list of coarchitecture words (some with a greater and some with a looser connection to architecture) which we list for you:

6 I NTR O D UC TI O N T O CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

In order to understand such a vast territor y of common living terms, we have

solutions as well as more conventional and norm based social organizations implemented through architecture. The idea has been to locate, map and analyze protot ypes in a Swedish and international context shaping a foundation for future project proposals, re-formulating ideas of co-housing, collective housing, and urban conditions in which the collective, common, communit y is prioritized

This seven-week course was structured around weekly assignments—as a guide to documenting and communicating research—in order to construct a critical understanding of the case studies and an overall view of concepts such as collective housing and communit y. Emphasizing the architectural qualities by confronting issues of dwelling, domesticity, culture, as well as tectonics and construction, this catalogue has become a mapping of architecture in service of communit y.

We were interested in looking at construction, material, and details. Complementing tectonics with looking at the living conditions. How have architects and communities made or furnished spaces and how did they plan the housing; for what kind of family life? Thus, exploring both the dimensions of the rooms in the plan layout, but also more sof t value analysis of the general culture, context and life of the town, cit y or suburb. One of the important aspects

of the project was to understand the possibilities that rests in the construction system of mass housing as well as questioning space related to function, outdated norms and family constellations, which can allow for design maneuvers that can improve the home environment With pressing issues such as climate change, altering social and urban living conditions because of the pandemic, these case studies can be a tool in rethinking contemporar y living patterns giving focus to how we can live collectively

With a deeper understanding on how living patterns transform and change across time, we can better plan for future changes. Today, forms of lease constitute a limitation for sharing space and of ten entail great risks for those who want to test new forms of housing. Despite a growing interest in sharing, there is still a lack of a functioning infrastructure for a sharing economy, especially with regard to housing issues. So far, discussions about sustainabilit y in the housing sector have largely focused on materials during the construction phase and on energy consumption.

Today, in many cities there is a desire to make greater use of space and functionsa desire to increase the sharing potential Even if there is a will to share, there is a lack of experience and practical solutions to turn these ideas into realit y. How is it possible to scale up social values in the cit y?

7

This research turned to four foundational texts, which also has given structure to the catalogue. The four perspectives on Co-Architecture are: Housing types, Co

In her book, Redesigning the American Dream Dolores Hayden highlights three main housing strategies based on their programming of home, housework and their relationship in between various households: the Haven strategy,y the Industrial strategy andy the Neighborhood strategy. The neighborhood strategyy usually encourages frequent interactions and the formation of close relationships between their members. Neighbors are encouraged to cooperate within the communit y and to care for the neighbors.

Understanding Dolores Hayden’s discussion on the histor y of “three alternative models of home” was a way to analyze communit y. Hayden argues that in the 20th centur y, alongside the working environment, the built form of the household became one of the most important factors in order to organize notions of productivit y, leisure, collective, individual, traditional values, progressive communities and feminism were the

housing

Redesigning the American Dream: the future of housing, work and family life

In the book Living together - cohousing ideas and realities around the world, Dick Urban Vestbro suggests a model to describe different t ypes of cohousing, originally proposed by Dolores Hayden. The model consists of three different categories, which are: Ideal life, Rational society andy Ecological. While these concepts are not per fectly distinctive, some of the cases that we have studied have features from all three categories; these have been a tool to distinguish the

catalogue have of ten started as a reaction to contemporar y societ y and consequently tell us about the development of cohousing through histor y. From the ideas of utopian communities as a reaction to the industrial revolution and the rational service houses that enabled women to work , to the birth of the environmental movement that combined collaboration and communit y with ecological ideals. These new ideas about living and dwelling have pushed societ y forward by challenging its conventions

Living together - cohous ing ideas and realities around the world

8

I NTR O D UC TI O N T O CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

Using the book Utvecklingen mot strukturalism i arkitekturen edited by Anders Ekholm, some of the main ideas approach Structuralism from a perspective of the collective/communit y The initiators of the movement can be considered to be “Team 10” who were an international group of young architects, including J.B. Bakema and Aldo van Eyck from the Netherlands, Alison and Peter Smithson and John Voelecker from England as well as Ralph Erskine as a Swedish representative of the group only to name a few. This group formed af ter the 1953 CIAM Congress in Aix-en-Provence, engaging in critical discussions and discourse on the then prevalent ideas of functionalism in architecture and urban planning. In order to deal with perspectives on communit y, we formulated concepts that derives from the Team 10 primer, which deal with the reoccurring themes of the movement: Perpetual Mobilit y/ Adaptabilit y, Patterns and Relations/ Living in the Urban Fabric and Part and Whole/Individual in Community y

By looking into projects that we consider as protot ypes of this movement, we hope to understand how different aspects of coarchitecture deals with these concepts of Structuralism.

Flexible housing has developed enormously in connection with politics, economics, social demography, and technology. One important book is Flexible Housing by Tatjana Schneider and Jeremy Till The development of dates back to the 20th centur y

Af ter the First World War, the need for housing on a mass scale lead Le Corbusier to propose the industrialized Dom-Ino system in 1914, which is a concrete frame structure that consists of slabs and reinforced columns. By separating the interior from structure, the system created a free-plan thus

Ino highlighted the possibilities for mass production and challenged how the free plan could enable housing development. During the 20th centur y, we could distinguish three important movements

1920s, space standards dramatically reduced in response to urbanization and the housing shortage. Less space meant there was an increased interest in the to offer more shared communal space to compensate for the reduced sized of home. A byproduct of this is that the shared spaces provided facilitated coliving by creating a place for communities to meet

Utvecklingen mot struktural ism i arkitekturen

Flexible Hous ing.

9

A LISTING OF CONTEMPORARY CO-ARCHITECTURE (Web-links accessed 2021-05-15)

This catalogue offers a number of cases— protot ypes—of co-architecture that serves as an insight to historical development relating to the four themes Housing t ypes, Co-Housing,

analysis and research the Housing Studio investigated possibilities to update, develop and change aspects of co-architecture in these studied protot ypes. This stage in the research is not included in the catalogue. However, we have included the continued investigation into contemporar y co-architecture by listing relevant books, websites, housing projects and research investigations

Grip, Elsa, Kärnekull, Kerstin & Sillén, Ingrid (red.), Gemenskap och samarbete: i kollektivhus och bogemenskap, 2019

Alternativ.nu www.alternativ.nu/index.php Boföreningen Framtiden www.boframtiden.se Bo i Gemenskap www.boigemenskap.se Cohousing Association of the United States www.cohousing.org/default.aspx

Cohousing Resources www.cohousingresources.com

Eurotopia, Director y of Intentional Communities and Ecovillages in Europé h ttps://eurotopia.director y/ about-eurotopia/ Föreningen för byggemenskaper www.byggemenskap.se Handbok för vardagsekologi, www.a l ternativ.nu /h an d b o k/b o / kollektivhus.html

Intentional Communities, www.ic.org Kollektivkontakten http://move.to/kollektiv Kollektivhus NU, www.kollektivhusnu.se Seniorhusföreningen i Karlskrona www.seniorhus.se Wikipedia, http://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kollektivhus

Lind, Diana. Brave New Home: Our Future in Smarter, Simpler, Happier Housing, 2020:

Common, NY, Boston, DC, and Atlanta, spawned Noah Apartments in May 2020 ShareNYC – 3 pilots announced in 2018 (Ascendant Neighborhood Development, Common, PadSplit)

WeLive, ex NYC and Arlington (connected to WeWork)

Ollie – ex Carmel Place NY, ALTA+, Long Osland (four C’s – convenience, comfort, cost savings, community)

X Social Communities, ex Miami, Fort Lauderdale, Chicago Archive (SF )

Embassy Network Hacienda (Brooklyn)

Lightning Society (Bushwick) Outside (Lisbon)

Co-Liv Lab (network org) Starcity (CA)

The Collective (London) PodShare (LA) PadSplit Thrive (https://thrivecolivingcommunities.org)

Las Abuelitas ( Tuscon AZ)

Nesterly, founder Noelle Marcus

Making Room: Housing for a changing America (exhibit Nat Building Museum 2017)

Minka Homes (from Japan)

Harvest by Hillwood (agri-hood) TX Eco Village in Ithaca, NY Serenbe in Atlanta GA

10 CO NTEMP O RARY CO -AR C HITE C T U R E

Co-Housing books, papers, masters theses, and handbooks:

CoHousing Cultures, Handbook for selforganized, communit y -oriented and sustainable housing (2012) https:// w ww.jovis.de/en/books/details/product/ cohousingcultures.html

CoHousing Inclusive, Self-organized, community-led housing for all (2017) https://www.jovis.d e/en/ b oo ks/d etails/ product/cohousing _inclusive.html

Design for gender equality - the histor y of cohousing ideas and realities (2012)

h tt p s://core.ac.u k / d own l oa d / pdf/80716121.pdf

Living together – Cohousing ideas and realities around the world (2010)

h tt p ://kollektivhus.se/w p -content/ uploads/2017/06/Livingtogetherwebb-1.pdf

Social, Affordable & Co-operative Housing in Europe (2020) http://www.housingagency.ie/publications/ social-affordable-co-operative-housingeurope

Living Alone Together: Individualized Collectivism in Swedish Communal Housing (2019)

https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/ diva2:1302073/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Co- living Real Estate in Sweden: A new investment opportunity (2020) https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/ diva2:1439971/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Bringing people together through housing and combatting loneliness(2019) https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/ diva2:1377500/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Coliving: an emerging term without a

https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/ diva2:1371948/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Cohousing and resource use A case study of the Färdknäppen cohouse (2014) https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/ diva2:762639/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Recently completed Swedish research projects:

Max 4 Lax by Theor y into Practice

( Vinnova UDI stage 1)

https://www.theoryintopractice.se/max-4-lax Elastiska Hem by Kod arkitekter ( Vinnova UDI stage 2)

https://kodarkitekter.se/projekt/elastiska-hem/ Framtidens delade boende by Akademiska Hus h tt p s://www.akademiskahus. se/aktuellt/n y heter/2020/11/ coliving-kan-halveraklimatavtr ycketper- person/

Contemporar y Co-Housing in Europe by Hagbert, Larsen, Thörn, and Wasshede http://kth.diva-portal.org /smash/record. jsf ?pid=diva2%3A1380580&dswid=-2398

- Divercit y by Föreningen för byggemenskaper and Theor y into Practice ( Vinnova) https://www.divcit y.se/omprojektet

Contemporar y Swedish Co-architecture

- Allihoop https://www.allihoop.se/

- Co- live https://colive.se/index-en.html

- Convendum https://convendum.se/sv/ coliving/stockholm/

- Hus 24 https://hus24.org/

-LifeX https://www.joinlifex.com/stockholm/ coliving-apartments

- Stena fastigheter https://www. stena f asti g heter.se/stena- f asti g heter/ nyheter-ochpress/co-living-i-gaffelseglet/

- Sällbo https://www.helsingborgshem. se/nyheter/sallbo-ett-ny tt-satt-att-bo

- Tech-Farm K9 Co-living https://www.k9coliving.com/

11

PROTOTYPES

HOUSING TYPES CO-HOUSING

24–29 30–35 40–4 5 4 6–51

SHAKERS 1806-1910

ONEIDA 1851-1879

KIBUTZ 1910 90–95ELFVINGGÅRDEN 194 0 36–39

AFFLECK HOUSE 194 0 52–57

DÄCKSHUS 1960

OVERVECHT-NOORD 1960 58–61

ÅLSTENSGATAN 1933 DUGGREGNET 5 1957 WANDELMEENT 1977

PRUITT IGOE 195 4 61–67

HÄSSELBY FAMILJEHOTELL 1956 96–103

78–8 3 84–89 104–109 110–115

WALDORF SEMINAR 1962 116–221

SEA RANCH 196 4

UNDERSTENSHÖJDEN 1995

PROTOTYPES

STRUCTURALIS M

BURGERWEESHUIS 1960

ROBIN HOOD GARDENS 1972 - 17

WALDEN 7 1975

DE ZONNETRAP 1980

132–137 138–14 3 144–149 150–155

FLEXIBILITY

KOLLEKTIVHUSET 1935 164–169 170–175 176–181 182–187 188–193

E XPERIMENTHUSET 195 3

UNITÉ D’HABITATION 1952 SUPER ADOBE EMERGENCY SHELTERS 1995-1997

VÄSTRA ORMINGE 1971

HOUSING TYPES COMMUNIT Y

At the turn of the 20th centur y many intellectuals, theorists and politicians started generating schematic models of how home life should be developed in the industrial societ y. The industrial revolution not only brought big alterations to the working industr y and economy, but also to the societ y at large. The opinion that an universal architecture could either promote or oppose certain social behaviors began developing. New societal movements and ideals started shaping, no aspect of life was too small to be considered, and the qualities of the new ideal household were elaborated clinically. Starting from the most basic of elements to then expand to a larger perspective; from the interests of the individual to the family unit, the collective, the communit y and then societ y.

Alongside the working environment, the built form of the household became one of the most important factors in order to organise the new rational societ y

collective, individual, traditional values, progressive communities and feminism modern housing ideas.

In her book “Redesigning the American Dream” Dolores Hayden highlights three main housing strategies based on their programming of home, housework and their relationship in between various households: Haven strategy, Industrial strategy and the Neighbourhood strategy These three strategies, and their strong relationship to certain architectural st yles, became the starting point for our research into the communal aspects of var ying housing t ypes.

14 THEME S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

1. Situation plan of Trudeslund, Vandkunsten Architects, 1979 - 1981

1. Situation plan of Trudeslund, Vandkunsten Architects, 1979 - 1981

15HOUSING TYPES

HAVEN STRATEGY

The haven strategy is a social living structure initiated at the start of the industrial revolution. As the pursuit of work led people from the countr yside to the cities, the housing crisis that emerged made strangers live tightly together in the same apartments. Many people did not even have a permanent living space and were instead forced to rent a spot in different apartments ever y night. Because of the health and moral problems with this cramped living, especially because of the rise in children born outside of relationships, many ideas and ideals started to emerge about how to organise people in relation to the new urban societ y. One natural way was to look at the living habits of the higher classes, which invariably have been idealised and imitated throughout histor y

The way the bourgeois upper class lived in the cit y differed a lot from the former life of the new urban working class, mostly because of the upper class’s high emphasis on the privacy of the immediate family. For people who were brought up on a pre-industrial farm, the idea of individual privacy practically did not exist, as ever yone on the farm lived as one large extended family, sometimes upwards of 50 people. Now the home instead became a refuge for the working man where he can spend time with his wife and biological children, and where

the woman can serve the family and be protected from the tough capitalist societ y. This strategy of social structure was coined the haven strategy by the author Dolores Hayden.

The focus of this strategy is ver y much the privacy and isolation of the nuclear family in their unit, without any features which encourage communal social activities. Social life outside of the family still exists but naturally gets more of a formal character, which means planned meetings instead of chance encounters.

The t ypology is usually, but not all the time, freestanding units, and it is generally as well equipped as possible when it comes to the functional amenities. Despite of this it can be pointed out that this strategy is the most dependent on exterior societ y out of the three strategies, both regarding work and income, housework, but also leisure and social life. These aspects are not intended in the haven strategy, and are expected to function independently of this living ideal. These different factors also make it possible to divide this strategy into subcategories, such as whether you are supposed to work from home, or whether you have external servants.

16 CO N C EPT S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

17 2. Ålstensgatan H O U S IN G TYPE S // HAVE N

INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY

To understand the concept of the industrial strategy that D. Hayden points out you have to grasp the fascination of that time for the machine aesthetics

International modernists found through architecture a certain fondness in suggesting something machine-made, acknowledging industrialization, mass production, and engineering, or that used elements of metal structures (ships, aeroplanes, motorcars, etc.) in an eclectic fashion as a proof of honest y and authenicit y. And most importantly,

societal questions that arose during austere times.

It was an assured method but became more a matter of arriving at an appearance than of actually being what it seemed, a fact that contradicted demands for honest y and truth in architecture, and denied the logic of structural principles

consumption of space from becoming too privatized, the special social needs of families headed by women, the elderly, and single people had to be highlighted. Central to the idea of the social condenser is the premise that architecture has the

intention of the social condenser was to

a goal of breaking down perceived social hierarchies in an effort to create socially equitable spaces. Another important factor of the industrial strategy is the strive towards an universal coherence in terms of the build form. No longer should the context be desisive of how we build our lives around the architecture, but intertwined and equal. Through rational means we would come up with sollutions and material that could be implemented and duplicated any where on the planet.

Ingenious schemes for communit y participation cannot correct the wrong program,

the tracts of scared huts. Modern family patterns and housing needs are too com-

- Dolores Hayden

18 CO N C EPT S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U R E

Unité d’Habitation

Unité d’Habitation

19H O U S IN G TYPE S // INDU S TRIAL

NEIGHBOURHOOD STRATEGY

The neighbourhood strategy is usually structured to encourage frequent interactions and the formation of close relationships between their members. Neighbors are encouraged to cooperate within the communit y and to care for the neighbors.

Neighborhood communities are t ypically formed by a group of people who are consciously committed to living as a communit y. The communities comprise private units and communal facilities, and they are planned based on social contract design principles that reportedly encourage more social interaction, helping to build more cohesive communities. The neighborhood strategy offers people to access and share the ownership in a communal place, to support cohouser members, to have a greater social responsibilit y and to enjoy the meaning of being a communit y.

In the book Redesigning the american dream (1984), Dolores Hayden described that “The neighborhood strategy produced the program for low rise, multifamily housing treated as a village with shared common, court yards, arcades and kitchens The models for the neighborhood strategy were the cloister and the village. The designers who favoured this approach believed that in the terms of housing, the whole must be more than the sum of its parts. For private space to become home, it must be joined to a range of semiprivate, semi-public, and public spaces, and linked to appropriate social and economic institutions assuring the continuit y of human activit y in these spaces. The neighbourhood strategy not only involved thinking about the reorganisation of home in industrial at ever y spatial level – from the house, to the neighbourhood, the town, the homeland, the planet.”

20 CO N C EPT S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

4. Elfvinggården

4. Elfvinggården

21

H O U S IN G TYPE S // NEI G HB O URH OOD

DIAGRAM OF HOUSING TYPES AND COMMUNIT Y

UnboundUnsupported DispersedRestrained

Individualit y

Famil y

Societ Community y

Social controlSupported ConcentratedNovelty

How is the social interests of the individual expressed/considered in this protot ype? Is it free/liberal/unbound or is the individual bound to a certain social control of other inhabitants or to the public due to mechanics of surveillance, human presence or transparency?

How is the family life supported or constructed within the protot ype? Does it get support through aid/service/ maintenance?

Where does the communal activities take place? Or is communit y evident through other aspects? Are these common grounds usually concentrated or dispersed?

As for the societal aspect its more in terms of its time established (the prototype). Is it innovative/groundbreaking in its context (novelty) or is it conservative/restrictive/ perhaps tr ying to preserve status quo or deep time (Restrained)? What is societ y gaining from this protot ype?

1.Vanna Venturi House, Chestnut Hill, USA, (Robert Venturi, 1964)

Wright, 1940)

3.Hälsingegård Jon-Lars, Sweden (Anders and Olof Andersson, 1857 )

4 Ålstensgatan, Stockholm, Sweden (Paul Hedqvist, 1933)

5.Däckshus in Kallebäck , Gothenburg, Sweden (Erik Friberger, 1960)

6.Llewellyn Park, New Jersey, USA (Alexander J. Davis et al., 1853)

7.High-rise of Homes, New York, US (James Wines, 1981)

8.Catalogue-houses, Egna-Hem (Sweden, 1900 - )

9.Elfvinggården, Bromma, Sweden (Backström & Reinius, 1940)

10. Wandelmeent, Hilversum, Netherlands (L. de Jong, 1977 )

11.Trudeslund, Birkerod, Denmark ( Vandkunsten Architects, 1981)

12.Stacken, Göteborg, Sweden (Lars Ågren, 1980)

13.WSM Zoliborz, Warsaw, Poland (Barbara

14.Habitat 67, Montreal, Canada (Moshe Safdie, 1967 )

15.Pruitt-Igoe, St.Louis, US (Minoru Yamasaki, 1954)

16.Duggregnet 5, Stockholm, Sweden (Georg Varhelyi, 1957 )

17.Panopticon, origin from the parallelogram by Robert Owen and phalanster y of Charles Fourier (Jeremy Bentham, 1790)

Group, 1930)

19.Cité Radieuse, Marseille, France (Le Corbusier, 1952)

22 CO N C EPT S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

23 hrobhgieN oo d Ha ven lairtsudnI 4 7 6 1 15 9 1 11 1 10 1 5 3 2 8 1 12 1 13 1 14 1 16 1 17 1 18 1 19 HOUSING TYPES

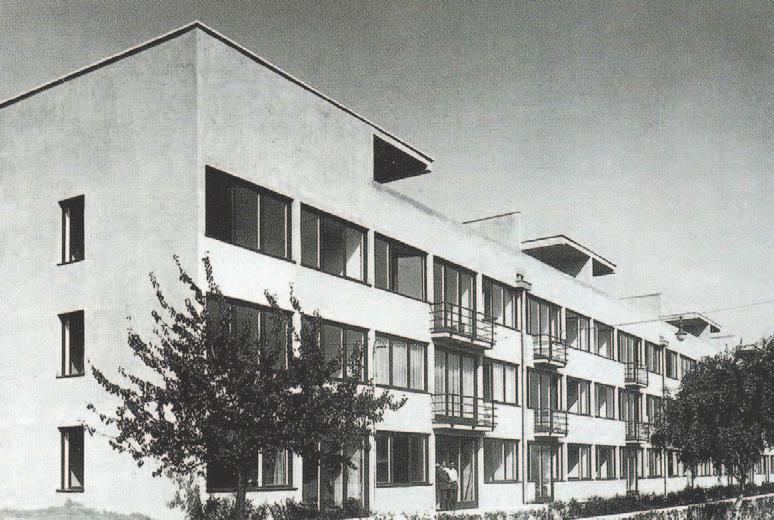

Å LSTENSGATAN

24 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U R E Erik Sandsten

Community Strategy: Haven Lifespan: 1933 - today Architect: Paul Hedqvist Place: Ålsten, Stockholm

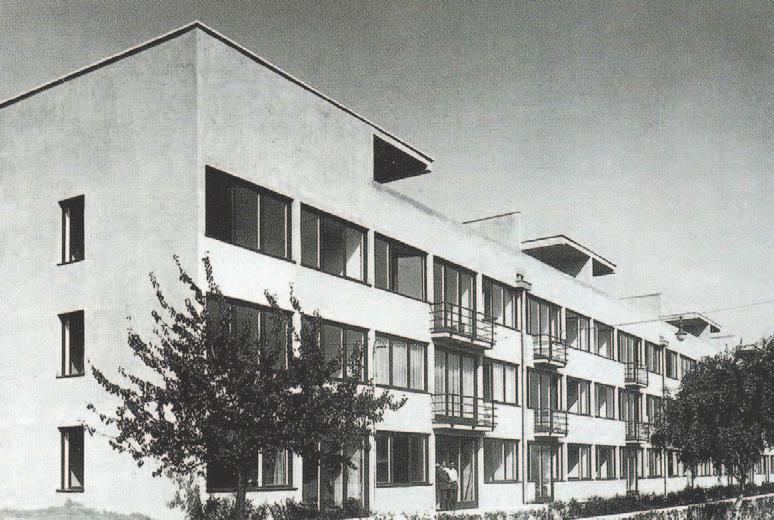

The Ålsten area was converted from farmland into a district of suburban single-family housing as a part of the expansion plan for the cit y of Stockholm in the early 20th centur y. The broad and straight main street was planned by Albert Lilienberg and Thure Bergentz and was initially meant to feel like a monumental and cit y -like boulevard, crowned with a never constructed citizen’s building at the end

As a result of protests from the neighbouring suburban areas, the goal for the architect Paul Hedqvist instead became to design terraced buildings along the street which reduced the perceived scale and monumentalit y of the already built road. This he achieved by rotating each housing unit away from being parallel to the street, and then placing the adjacent volumes with the front facades offset from each other. This breaks the typically long and straight facade of joined housing units, and it also gives the housing units a better view towards south and the water Qualitative Diagram

The st yle is functionalism, with its simple white cubic volumes and few ornaments. Paul Hedqvist was interested in how affordable family housing could be created with this st yle, and a way the idea of affordabilit y is evident in the plan is how many rooms each of the 94 constructed housing units have on an area of about 120 square meters (84 sqm above ground). Each unit has its laundr y room, boiler-room food storage, and spare room, all in the cellar. The two

kitchen, dining room, living room, WC and three bedrooms. The plan got some critique for its lack of storage space

An important aspect in Hedqvists idea of affordable family housing is shown to be the privacy of each family member, and the goal was to create the feeling of a freestanding house in a tight terraced t ypology. It was also important that ever y family had the necessar y daily household amenities under their own roof, a level of comfort, and privacy, rare just a few decades before

, Qualitative Diagram 1.Initial view at arrival

The social exchange in this project is always of a more hierarchical t ype. Because of the closed and privately owned nature of each unit, the social life is inevitably taking place on the terms of the owner and his/her family In the plans to the lef t the rooms of a

darker for the rooms which more exclusively are used by the family, and a lighter hue for the rooms which also may be relevant in the case of external social interaction

It is interesting to note that, because the upper bath is the only WC in the house, it is to be used even by guests

The hall is designed to be portioned off with a curtain, which creates an even more private living room for the family.

The semi-shielded area in the front exterior of each unit is created by the offset relationship between the building volumes, and together with the greener y it is in a sense helping to bring the perceived scale of the street down

There are two rooms in the house with a clear adaptabilit y, one ver y dark in the cellar and one next to the entrance. The ver y narrow one on the ground

in many later renovations the wall to the living room has been torn down, to create a more open and bright living room

The functional rooms in the cellar, including the spare room, is what gives this unit a high level of autonomy It makes a communal laundr y, heating facilit y, guest room, food storage, workshops and shared work-areas, which can be found in co-housing projects, obsolete

25

HOUSING TYPES // HAVEN // Å LSTENSGATA N

26 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U R E = : ( %% , % /0 /1 5 )/%)%/ 5 (.( %/1)% 5 )-4 /1 %)/ % 0)/1 , &+1 , /0 /1 ),1 5 %? 9):) , 0)/1 , 0) ( 0%/ 0 (%/1 , ( 261 + +/): +1- ) 42 A &/ ) 0 % ( -+ 4 )+;% 0)/1 1),1 5 / -/ ( ) % ) %5 /) 261 B )%1) ,)%01)/ %/ 2 = + 4 : ;) ,/1 +; , ( / 0) + 0)/10 ( D ) ,2 ) ) ,+ /1) ,? 3 ( %.0)/1%/ , (0+ /1 5 D 2

27 % & % () + ) ) , -% %. ) / (01)/ 23 % 4 ( -+ + / + %/ () 0 (5/ %%) 4 ( 5/ -0 (2 61 7 0)( - / )%% )8 5 )+2 9 01 (, % +/ % ) / 0 (%/1 ( 5/ / /0 /1 ),1 5 %.) + %/ %// /1 ): / +;, ( %2 61 ;)/+1 (() ) , / 0 (%/1 %/ / +1 %%/1 0)( % %5 / -/1 + ( 8( / ) ) ,+ / / + (1 0 4():)() ,/1 2 61 + 1 %/1 %01)+1 ; %/1 5 )/: 4% -8%5%/ ) ) , //1 /) + %/ 5+/) .%5+1 % ) 8 .- ( + ( , 5 ( 4 261 1 + ) /1 +;+ / ( /1 4 ): +4. %4 5 % + 5 (0 ;- 1 2 C %) / + %/ 5+/) .0)/1 / 0 (%/1 +;, ( 2 HOUSING TYPES // HAVEN // Å LSTENSGATA N

The terraced buildings on Ålstensgatan were created as isolated refuges packed into a tight building t ypology. As a result of the intent of making these units as

where communal exchange can take place is the exterior. The vastness of this straight road without any real common areas or features of interest makes it ver y anonymous, and it almost becomes more of a space in relation the urban scale than to a potential communit y Shielded from this road is a semi- public zone, framed by the front facades and by hedges towards the street, but with no borders between the neighbours. The

trees and bushes help to create cover from the street, which helps to create a more private or maybe even communal feeling in this semi-public zone. Without the greener y, this street would have similar dimensions to a streetcar road in than the varied street width of a t ypical suburb. But these intermediate spaces bring the scale down to something familiar. A sign of a possible communal life in this semi- public area, despite of the privacy of the housing units, is the paved paths between the front doors of some neighbours.

Perspective of the street

Daylight study, view towards south on a summer evening

Perspective of the street

Daylight study, view towards south on a summer evening

28 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U R E

Ålstensgatan is a private t ypology, with a similar idea of communal life as the freestanding houses around it, even though it is a mass housing project which achieves this in a cheaper and more dense way. The plan is ver y complete for the number of square meters, and the architect has added the cellar with amenities to avoid the need for shared rooms in the neighbourhood. Privacy was seen as more desirable and luxurious than the potential assets of communal life in this case.

Each unit has its own heating facilit y and its own laundr y room, and even a

took space from the living areas, for example the kitchen and the dining room, to give the families these amenities. At the time of construction, the terraced house typology was new to Sweden, and the design decisions is clearly a way to establish it as a more private t ypology, as opposed to a communal one which it may have potential to be.

The exterior semi-public area may be seen as an attempt to create a closer communit y, both between immediate neighbours but also through the visual connection to the street. The spatial dimensions of this space is at

2.Aerial overview least creating a possibility for more social encounters than with a front door right at the sidewalk, but there are many factors which decide to which extent; where people choose to park their car and how they travel, the age and season of the organic elements for example

A low level of greener y, like at the time of construction, creates a ver y vast and anonymous space, and a high level of greener y, like what has happened at some instances in the last few years, creates secluded spaces even in front of the buildings. The level of greener y can because of this not be counted as part of the architectonic plan, but is rather a way to give the inhabitants a choice together with their neighbours about the desired level of privacy or openness. Another reason for classifying it as the haven strategy is because a well developed communit y can appear even if the architect has the opposite vision, which may be true in these historical buildings available only for high-income people who are proud of their area. This is relevant if you expect to get the same result if you would replicate or mass produce this t ypology in a new context

2. Aerial overview

29

HOUSING TYPES // HAVEN // Å LSTENSGATA N

THE AFFLECK HOUSE

Housing types Strategy: Haven Lifespan: 1940 - today (donated in 1978 to LTU)

Architect: Frank Lloyd Wright Place:

designed for the ground it is standing on and served as a protecting, single family

making it a per fect example of a home within the Haven Strategy

familiar with Wright’s work, especially liking his house Fallingwater and therefor contacted him when they were to build their per fect home. Wright answered with

of land to build on, and af ter that the work on the plans started Wright had a focus on giving his clients satisfying homes to a low cost, aiming to solve according to him a problem in the housing architecture of America, the “small house problem”. He was also especially interested in making homes modern in both st yle and technology to serve as a functional home for a long time.

challenging site, the house had to take care of a fort y feet ravine and a small stream of water running through their plot. You enter the building from the north end on the top of the ravine which enhances the feeling of a modest one story house. The north façade is keeping the secret of the plan from the viewer being completely closed with windows carefully placed at the top of the brick wall. It is not until you turn lef t and enter the big, air y living space and walk to the south corner of the living room you can feel the light and the height difference of the site. Something quite radical at the

time is its open plan in the living space with a lot of daylight and large windows. Also placed in the south corner is a big balcony that runs along the sides of the open living space. If you would have instead turned right entering the hallway you would have found yourself walking up a few steps and through a long corridor with bedrooms appearing one by one on your lef t and a thick, long wall without windows on your right

Elizabeth and Gregor y lived in the home till they passed, and then the family donated the house to Lawrence Technological Universit y in 1978.

30 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

Familysupported Familyunsupported Individualityunbound CommunityConcentrated Community Dispearsed Societynovelty Societyrestrained Individualitysocial control

31H O U S IN G TYPE S // HAVEN // AFFLE C K H O U S E

1. The entrance of the house

T he common spaces

Shown in the picture above is what you see entering upon the site. The main entrance is in the center of the picture and to the right you can see a closed façade with top placed windows. The picture to the right is of the balcony. The two pictures together show you the start and the end of the journey for a guest

In the perspective you can see guests waiting to be let in to the home to the right and the others who are just exploring the home. The cut of the perspective is stairs leading down to the basement.

Open plan living space and balcony

Single family home

Social gatherings in the home

With this I’m tr ying to focus on the hidden life of the house, meant to be invisible to guests and the common spaces. In the bottom right you can see what is called “The maid’s room”, letting us know the house is also built for staff working for the family. This is an interesting aspect looking at communit y within architecture, in this private “Haven” home the family was not meant to live alone. The architect is also actively hiding this other life in the house, by placing the only interior staircase in a room the guests will never enter, the kitchen

The family never had staff living there and these rooms were slowly transformed into teenage bedrooms and workshops

32 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

Perspective

2. The balcony in the south corner

2. The balcony in the south corner

33

1:100

Plan 1:500 H O U S IN G TYPE S // HAVEN // AFFLE C K H O U SE

The building is mainly built of masonr y

of load bearing brick walls, some of them

has been replaced with leaning cypress walls. The south façade opens up with glass windows and doors, creating a

The roof tretches horizontally outside of the brick walls creating an overhang to rest under during rainy days. The roof too has been opened up with windows,

giving the view to the sk y from within the building. For the roof on the outside those openings are lef t as holes without the protecting glass. Entering the building you are drawn forward by the guiding roof windows and the glass wall in front of you. Following the yellow line in the axonometric you can see how the glass keeps dragging the visitor in to the social space, in contrast

entering the site

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Brick, cypress, glass, concrete, copper, asphalt Load-bearing masonry

Usonian, Single family dwelling

Brick Cypress Concrete

34 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U R E Glass Copper

35 Axonometric H O U S IN G TYPE S // HAVEN // AFFLE C K H O U S E

ELFVINGGÅRDEN

Kamil Kowalski

Kamil Kowalski

A housing complex for unmarried women - “single educated ladies, who have lived

lives and whose annual income does not exceed SEK 6,000 and who are under 60 years of age” (Statens Offentliga Utrednigar), built by Systarna Elfvings Foundation and Olle Engk vist in 19391940, designed by Sven Backstrom and Leif Reinius.

The complex constisted of nine buildings. As apartments were intended for people without families, rooms were relatively compact, although they included

Housing types Strategy: Neighbourhood Lifespan: 1940- today

Architect: Sven Backstrom / Leif Reinius

Place: Stockholm, Sweden

kitchenettes and toilets. All the buildings were connected with covered arcades to the main building in which communal spaces, such as cantine and shared ‘ living room’ were located.

The building was operated by the foundation, providing residents not only with meals, but also services such as cleaning and laundr y conducted by a household staff. It was intended that the residents would have to do as little housework as possible. A grocer y store was located next to the main entrance.

36 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

37HOUSING TYPES // NEIGHBOURHOOD // ELFVINGG Å RDE N

38 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U R E

Communal space

Individualityunbound

Familysupported

Communityconcentrated

Societynovelty

Societyrestrained

Familyunsupported Individualitysocial control

Communitydispearsed

39

HOUSING TYPES // NEIGHBOURHOOD // ELFVINGG Å RDE N

PRUITT IGO E

Stellan Gulde

The Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis became most famous at the moment of its demise. The iconic picture taken in the moment of demolishon has been aclaimed to depicture the ver y essence of failed architecture ever since. I quickly learned, this statement is a

whole situation.

The thirt y -three high -rise towers built in the 1950’s were supposed to solve the impending population crisis in inner cit y St. Louis. It was supposed to save the urban poor from the indignities of the downtown slums that lacked natural light, water and fresh air. And for a short while, it worked. It was a housing marvel

But soon enough things went bad, and as they did the situation escalated rather fast. The integration of the Pruitt and Igoe apartments resulted in most of the white residents leaving en masse, along with those black residents who could afford single-family dwellings elsewhere. The only tenants lef t were those who literally could not afford to go any where else

Pruitt-Igoe’s fall from grace began almost immediately. There was little money to keep up the 33 towers, and they subsequently fell into disrepair

The combination of unfortunate design choices, deepseated racism, and poorlystructure housing policy could be said to be the reasoning for the twent y year

Housing types Strategy: Industrial Lifespan: 1954 - Demolished in 1972

Architect: Minoru Yamasaki Place: Saint Louis, US

The reasons for the decline were manifold, far too complex to deal with in full here, but at a simple level, St. Louis was a declining city well before residents moved into Pruitt-Igoe. The majorit y of residents came from the Afro-American communit y and were disproportionately affected by the cit y ’s rising unemployment. Unemployed residents could not pay rent and therefore rental income reduced. At the same time, the St. Louis Housing Authority had, for ideological reasons, decided that the entire maintenance programme was to be funded by rental income alone. This combination of events ensured there was little or no money available for essential maintenance work. The infrastructure deteriorated and in a spiral of decline, crime rose, vandalism increased, leading to greater deterioration of the fabric: a true vicious circle

At its peak occupancy in 1957, 9% of the complex remained vacant; by 1960,

skyrocketed to 65% by 1970. With the apartments occupied almost exclusively by a dwindling number of low-income residents, a number of whom subsisted on welfare.

Charles Jenks, architectural critic, stated that the modern movement in architecture died at exactly the hour when the public housing complex was demolished: July 15, 1972, 3, 32 P.M. “Boom, boom, boom”

40 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

41 Jul y 15, 1972, 3,32 P. M H O U S IN G TYPE S // INDU S TRIAL // PRUITT I GOE Familysupported Familyunsupported Individualityunbound CommunityConcentrated CommunityDispearsed Societynovelty Societyrestrained Individualitysocial control

Fictive perspective based on the sto ries told by former tenants

The vandalism that led the housing authorit y to install a bunch of unbreakable designs in the tower...Instead of tr ying to enhance their exsistance, we’ll just make things so they can’t be destroyed Ever y thing had to be protected, light around them with mesh metall, protecting

a great deal about this. They even had their PR department brought out to witness the new installation

Shared outside spaces and interior corridors

haviour of a stigmitazied place

The urban p oor

Several outdoors activities and gathering spots

The only human reaction to be presented with an unbreakable object is to tr y and break it.

The fact it was unbreakable made you want to tr y and destroy things. There was a screen around the lightbulb that kept you from breaking it. But you know, kids

We just put water in it, throw it up, and the light would get hot and as it gets hotter it

42 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U R E

Site plan and connections to buildings, only 40 % of the planned lighting was maintained

4. Tenant family overlooking the complex

3. The Pruitt Igoe complex seen from above

3. The Pruitt Igoe complex seen from above

43

H O U S IN G TYPE S // INDU S TRIAL // PRUITT I GOE

Implementation

The apartments were deliberately small, with undersized kitchen appliances. “Skip-stop” elevators stopped only at

an attempt to lessen congestion. The with large communal corri- dors, laundr y rooms, communal rooms and garbage chutes. Pruitt–Igoe was initially seen as a break through in urban renewal. Residents considered it to be “an oasis in the desert” compared to the extremely poor qualit y of housing they had occupied previously, and considered it to be safe. Some referred to the apartments as “poor man ’ s penthouses

Residents cite a lack of maintenance almost from the ver y beginning, including the regular breakdown of elevators, as being a primar y cause of the deterioration of the project. Local authorities cited a lack of funding to pay for the work force necessar y for proper upkeep of the buildings. In addition, ventilation was poor, and centralized air conditioning nonexistent. The stairwells and corridors attracted muggers. The project’s parking and recreation facilities were inadequate; playgrounds were added only af ter tenants petitioned for their installation

Mainly concrete

Slab structure 1949 Multistory-houses. 33 11-story apartment buildings consisting of 2,870 apartments

1 Structure

Average load bearing columns in concrete Normal stair system

2 Interior support spaces

3 Circulation

Line of circulation Means of going up or down One way in - one way out

4 Layers of building system

Standard puncture windows Pods divided by insulation and concrete walls

5 Collective space (section)

Degree of public (intense yellow) to collective (bleak yellow) spaces

44 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U R E

1 2

in

5. Axonometric examp of multistory-housing Pruitt Igoe

5. Axonometric examp of multistory-housing Pruitt Igoe

45

3 4 5 H O U S IN G TYPE S // INDU S TRIAL // PRUITT I GOE ple

DUGGREGNET 5

Stellan Gulde

The house was built as a residence “ from the cradle to the grave” with larger family apartments higher up, small youth

restaurant, pharmacy and laundr y on be studios, a restaurant and a garage with a petrol station in the basement. At the time, there was a severe housing shortage in Stockholm and a youth hotel with many small apartments would solve the housing issue for young people who moved to Stockholm af ter the Second World War. There were 115 available beds for the adolescents. The intention from

from all socioeconomic stages of life could live in Duggregnet 5. A small village in minature for 400 people

Housing types Strategy: Industrial Lifespan: 1957 - today Architect: Georg Varhelyi Place: Björkhagen, Stockholm

preschool and infant ward as the parental insurance was not invented at the time. If you needed to repair yourself, there were doctors and dentists in the house next door. As a crown jewel, a funeral home was also planned. A house for all needs. Built in durable and reinforced concrete

Strongly resembling Le Corbusier ’ s famous Unite d’Habitation projects, the building was designed for a highly diverse program and with extraordinar y apartments, comprising up to four stories. For the interior design, the architect

upper parts of the house, which resulted in apartment entrances from corridors

A majorit y of these apartments are vertically zigzagged around central corridors. It provided large apartments

windows in two directions that let in a lot of light. Some rooms had double ceilings and tall windows. According to Varhelyi,

what he succeeded best with

All facades are different. To the west, it is the windows that stand out. To the east, the balconies dominate the perspective with like small birdhouses. To the north you understand that it is a staircase inside the small concrete glass windows and on the south side you can see how the corridors appear behind recessed balconies. In this way, the architect wanted the house’s functions to be visible on the facade. Big but at least honest.

previously youth appartments, are genomgångslägenheter or passager apartments. These are destined for new arrivals, which, according to the Settlement Act from 1 March 2016, all municipalities in Sweden are obliged to receive and arrange temporal housing for. This is administrated by the Swedish Migration Board.

46 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

Community

Family

Individuality

Community

Familysupported

Individualityunbound

Familysupported

Individualityunbound

47H O U S IN G TYPE S // INDU S TRIAL // DU GG RE G NET 5

unsupported

Concentrated

Dispearsed Societynovelty Societyrestrained

social control

– In 1957, the highrise building that Georg designed was compleated. It breathed modernism in a way that no other building could measure up to. Was

– Yes, he probably thought it was hisY masterpiece, the house in Björkhagen. There he combines what he think is most important: the social qualities, the light, the form...There are sections there he was really happy with the result, where the sun shines through the whole thick house. He would have liked to move there

with his family, but his wife did not think it would be appropriate to live there with children.

Community facilities

generations under one roof, creating that one house to stay in for a lifetime

Inhabitants of New Sweden

Neccessary facilities downstairs

... But a week earlier, I had been assigned a student room.

– Björkhagens Residential Hotel...It does not sound so fantastic. But how bad can it be?

– Ouch...

The room was furnished, but it felt more like a prison cell ...

– Well, at least I can smoke indoors without feeling ashamed. And it probably feels better as soon school starts ...

3. Comic strip

48 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

4. Sun study section with perspective

Perspective showing relation between domestic and public corridor

4. Sun study section with perspective

Perspective showing relation between domestic and public corridor

49

H O U S IN G TYPE S // INDU S TRIAL // DU GG RE G NET 5

Interior Loadbearing system

Between 2001 and 2004 the programe changed, what former was the youth hostel and hotel rooms became

- 8th. This also included a renovation of the canopy and balconies.

As I visited the building and transcended upwards in the stairwell hall I reached the point were the former youth hostel ceased and was faced with a gate. Prior equipped with survailence cameras.

Svenska Bostäder - a municipal housing company fully owned by Stockholm Municipality

view, possible to take part in from the as you would think, but instead rather exclusive.

This started an investigation of how the building changed over time, both ideologically and in term of maintencene

Svenska Bostäder, land lease

Multistory housing. 108 apartments. 20x one roomers

47x 3 rooms and a kitchen 40 % of total are rental appartments today.

Design regulations & construction

Building

1 Interior walls

bones. A spine of a load bearing 500mm wall that seemingly goes through all the way down supports the pre casted concrete panelwalls distributing the loads sideways

2 Structure Rational structure system with a variation in zig zag slabs.

3 Exterior walls All facades have different outlooks, in order to highlight the function behind them - a sign of honesty.

4 Windows enables daylight to shine through appartments from two sides

Landscape

A Centrum Georg Varhelyi not only designed this building, but also the centrum around it trying to create a holistic sense.

B Statue and allotment gardens

In front of the house stands The fountain of Björkhagen, a sculpture and fountain created by Email Näsvall in 1963, showing working people in different professions and stages of the day. Ini tially the tenants were intended to get access to allotment gardens in connection to the building

C Citizens House

In connection to the house lays the citizens house, meant to provide an open and protected space for cultural and political activities for all citizens of Björkhagen and surroundings. This particular space changed its function in 2002 from a public meeting room into a restaurant and independent school programme for primary and middle school use

50 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

Exploaded axonometric view of Duggregnet 5

Axonometric view of type etage apart ment

Axonometric view of stairwell hall

Axonometric view of stairwell hall

51

H O U S IN G TYPE S // INDU S TRIAL // DU GG RE G NET 5

D Ä CKSHUS

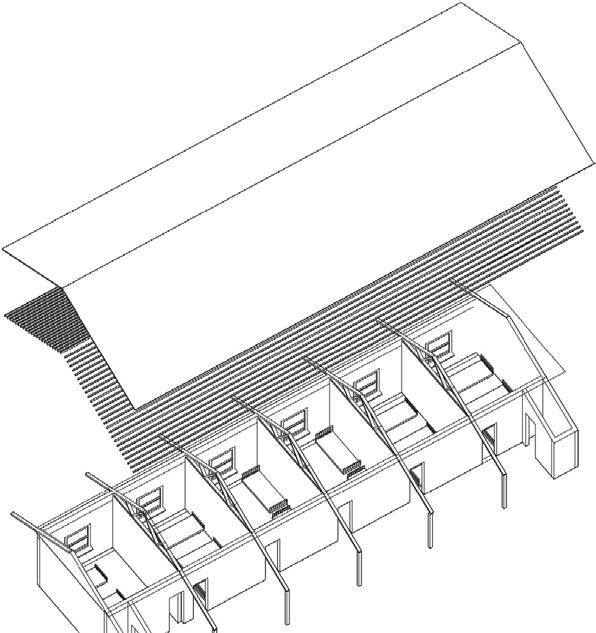

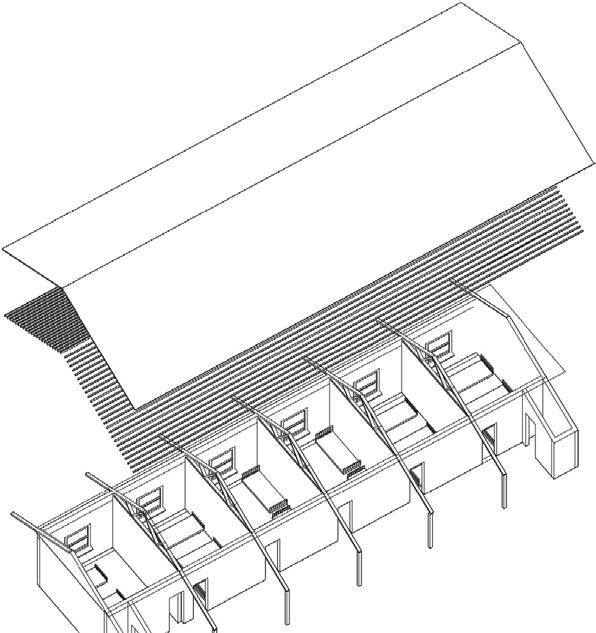

Erik Friberger was an architect in the functionalist and structuralist movement, and this project is a protot ype where he wanted to show how to construct prefabricated and inexpensive housing, in a tenant- governed process. The question of how to utilise prefabricated systems was important at this time in Sweden, as a potential way to solve the housing crisis in the early 20th centur y

The main idea with the tenant- governed design process was to let people plan a house of a size within their budget, on a designated lot on the multi-storey t ypology which meant a lower cost per unit. The given lot, constrained by the concrete structure, would still be to their disposal for future additions. This would give the working class the same

disturbance from neighbours and a better ventilation in comparison to standard apar tments.

The building is a system of 18 freestanding single-family units evenly placed on a three-storey concrete structure. The units and the structure

Community Strategy: Haven strategy

Lifespan: 1960 - today

Architect: Erik Friberger Place: Kallebäck, Gothenburg

are clearly separated and with different

supported by a system of columns and cantilevered beams, with a span of 10 meters between the columns. Because of this structure, it was only possible to extend the housing units to the columns and not to the edge of the cantilevered

plan as it created almost two meter wide balconies all around the units on each

these balconies was never realised due to structural limitations

staircases, which means six units are reached by each stair. Installations originates next to the stairs which made it necessar y to place kitchens and WC close to the stairs inside of the units. The tenant- governed process led to a large variation in colour and window placement in the housing units, but all ended up about the same size, about 120sqm each, and because of the dense building this led to, the project was partly seen as a failure by Friberger himself.

1.Initial view at arrival

Qualitative Diagram

Erik Sandsten

52 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

, , ,

The common areas for this multi-storey

This includes three exterior staircases, garage, long -term storage for each unit, bike and stroller room, central heating room, laundr y, association assembly room and other utilit y rooms

All the rooms except the assembly room are without insulation, and the amount of daylight in these rooms is ver y low. It is

is to help the tenants to get to and from their unit, and the front of the building is dominated by carports and parking lots

2.View of typical housing unit

2.View of typical housing unit

53

3.Section

HOUSING TYPES // HAVEN // DÄCKSHU S

54 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U R E %& () (+ % & % , & &(% ( ( / ,% 01 %& 2 & && 34 & &(% ( 5 % 0 & + (,% ,%& % & , & (6 6 ,% + ( (3.6 & &%(++70 % 0& 0 (++ /& 0 ,4 / %+,% 0 & ( %+%&7 ; (35%& ( 6( / =3, %,% 0 & %&5%,& & ( ,% 0&% 3 / (3 & &% ? (& A6 , / & , 0 6%& . +(,% % B / ) % 0& &(%5 ++ B ) & %& ) , 7( & , C () (+ 5 6%& & ( & 6 / H %)(&

55 8 % +(& , 0( (0 % ++ ( 9(% &( 5%& & , +%3(& ++ : &3 &(+ / 6 %)( 7 &5 (+ % : +% , % / , & &(% ( & 0 (++4 & & 64 5%& ( = 0(& , &3 &(+ DDDDD & , C ( 6 % )(& DDDDDDD; & & 34 % ( ,E6 + % FG DD : ( , 33 & ( && & &% IH % +7,( 0 5 , % ) &(% 0 & (, () )%5 / 6 6+ % 0& (,/ 3 &( & 6( C% 0. & %+,/ % ,+7 JI ( %&% / 3( 6 (+&& /(% A6 ,(00 0(& & 6()% 0 KI?(++ 3(, /% %& & ( & ,% 5 ,/ 3 I 5 %& L % , & M & +% 0 & 6& &( 3 & /& &% 3 NI L &+ ( ,% 0% 6 & & ( , ( C7( ,5 % % .O3 ) & 6( C% 0% & / & OI ( %(&% 3 &% 0 3 .% +(& , &5%& 6 ,(7+% 0 & 1I ( , & (0 / & ++ ( , %C PI 6 %)(& & (0 / ( %& Q&& % & /( Q) (0 H %)(& R % 08 %& I &, / 3 &(% ( +%3(& ( % JI % + & + & &(% ( ,& ) &%(+ 5(0 6% 6 KIH %)(& C%& & ,& +%)% 0 3 NIS( 0 +%)% 0 35%& 5% , 5 &5 % , OIS 0( , ( 5 (+ % & % , ( /(3%+% 7 ( (, T (& 6 %)(& A& % 6( /& % 5 1IS( 0 5% , 5 & 5( , (0 (&)%5 /U & 0 PIV +(& ,5(++(0(% & % 0 6 % + 3 %& % F WIQ % 0 3 / (+ 7, / ) &%+(&% HOUSING TYPES // HAVEN // DÄCKSHU S

The two shadowed perspectives, both taken on a summer day at noon from opposite sides of one of the shared entrances, show the most frequently used space in the building. These communication areas can be described as spaces solely for circulation, and together with the rest of the buildings

as the laundr y, the parking garage and a green slope southeast of the building, it is merely a byproduct of the main concept of privacy for each family

The space, with its low ceiling height in relation to its length, together with the way little daylight gets into the space, makes it quite uninviting and therefore less attractive as a space for any thing more than circulation. The fact that this space is without climate barriers and doors complicates the privacy aspect, as it makes the space reasonably accessible

the other hand this is also making it more anonymous and thereby less attractive as a collective space for the tenants

Another interesting aspect is the hierarchy between the ceiling height of

as this is shown to be reversed from the standard, with a lower ceiling height on

or a cellar, and not of an entrance. The conclusion is that this is a building where the tenants share certain amenities, but in no way are encouraged to maintain a communit y in the social sense.

56 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

haven strategy because of the total independence of each unit. The large housing units, with a great view of central Gothenburg, have good chances of hosting the more formal meetings ver y much associated with the haven strategy. The large private balconies take focus from a potential collective garden, and each of the three staircases are used by just a few households. The few necessar y semi-public spaces are not enabling chance encounters between neighbours, and the lack of a climate

shell around these shared spaces do not encourage such activities in the cold climate of Gothenburg. Even though efforts seems to have been made to brighten up the shared spaces, such as light coloured paving materials and white walls, it still fails in being a good place to meet your neighbours. Lastly, while the most economical and rational energy preservation method is a shared climate shell, the concept of the project leads to the opposite, which means the driving force for this project is shown to be freedom and individualit y.

57

HOUSING TYPES // HAVEN // DÄCKSHU S

OVERVECHT-NOORD

Kamil Kowalski

58 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE Housing types Strategy: Neighbourhood Lifespan: 1971- today Architect: H.W.M. Janssen Place: Utrecht

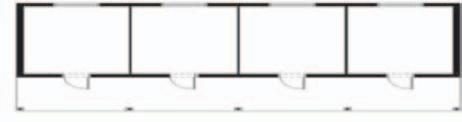

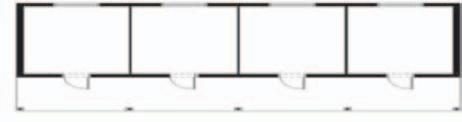

Completed in 1971 in Utrecht, planned and realized by architect H.W.M. Janssen and funded by the Cit y of Utrecht Administration via the Department of Building and Housing Services (Schmid), Overrecht Noord consists of 10 four- and seven-storey buildings based on the same plan.

On each storey four three- and four

the current standard of nuclear family

communal space connecting them to a staircase, supposed to be managed and inhabited by the residents themselves in a way which best suits their needs, serving as a threshold between family and communit y. A number of different

Individualityunbound

uses for the spaces were found by the residents, such as common living areas, cafes and workshops - some of them focused mainly on the families

while others were concerned with the a cloackroom with a tolilet served as a threshold space between the communal area and private spaces

When the building was built this approach to shared spaces, governed by the was a novelt y. As the cit y administration expressed a concern regardnig interest

a public campaign and informational events were conducted (Schmid)

Familysupported

Communityconcentrated

Societynovelty

Societyrestrained Familyunsupported

Individualitysocial control

Communitydispearsed

Urban plan

59

H O U S IN G TYPE S // NEI G HB O URH OO D // O VERVE C HT-N OO R D

Communal space

Communal space

60 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U R E

61H O U S IN G TYPE S // NEI G HB O URH OO D // O VERVE C HT-N OO R D

W ANDELMEENT

Housing types/Community Strategy: Neighborhood strategy Lifespan: 1977 - today Architect: Place: Hilversum, Netherlands

The project

The idea behind Centraal Wonen Hilversumse Meent aka. Wandelmeent dates from the 1970. The project, which comprises 50 houses and

the governement-subsidized rented housing sector. In 1977 133 people moved in. Each household rents a house with private facilities (kitchen, bathroom) and the use of common facilities. The houses var y in size from 41-107 m2. There are communal areas at two levels: the cluster and the group. There are ten clusters and almost all houses (44) belong to a cluster. A cluster is an intentionally created social and spatial unit. Each cluster consists

houses, a common dining room and kitchen, terrace, washing machines, and a garden. This means that socially a

households, about 10-12 people. The composition of clusters is the result ofthe result of a careful process of acquaaintance and choice/selection.

“Outsiders often think it’s a borderless party here, but if I do not want contact, I close the door behind me. We have our privacy here, just like everyone else.

Each front door can be locked ”

/ Margriet Jobse

https://www.trouw.nl/nieuws/elke-voordeur-kan-gewoon-op-slot~b8b6ba0f/

T he foundatio n

The Centraal Wonen Foundation was created from a private initiative to develop a living communit y. This movement was ideologically motivated. They wanted to live in groups

People no longer wanted to isolate themselves in the fortress of their own home or withdraw from social inequalit y Architect De Jonge offered to make the design on a “no cure, no pay ” basis. This district was developed in the early 1970s on the former communal pastures of Hilversum, as an enclave next to Bussum.

Fifty houses is just the right scale.

With more houses, it becomes too anonymous, with less you are too de pendent on each other.”

/ Margriet Jobse

https://www.trouw.nl/nieuws/elke-voordeur-kan-gewoon-op-slot~b8b6ba0f/

Tina Franc

62 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

63H O U S IN G TYPE S // NEI G HB O URH OO D// WANDELMEENT h d dl dK Kitc en an laun r y C Craf tshop S Storage H Hobby Y Youth center M Meeting space I Independent house C ommunal Semi-Communal Private

Common spaces m2

Dispersed - Each cluster of 4–5 units shares a garden, kitchen/dining/living room and a laundry room. The whole community shares a common house, li brary, sauna, workshop, gym, guestrooms, youth centre and garden.

private houses 41-107 m2 common dining room and kitchen 33 m2 social activitiy/meeting house 95 m2 day care 41 m2 youth club 41 m2 hobby building 21 m2 pottery 6 m2 repairs, guest room and sauna 30 m2

In Wandelmeent you always choose your neighbors. If a house becomes available, people within the cluster can register for

only then someone from the so-called candidate list from outside. It’s different from a waiting list. The cluster

which candidate best meets it. Some

newspaper.

Program

Residents

50 homes plus common areas

133 people moved in 1977: one and two-parent families couples and singles 38 men 41 women 54 children

Eating together Design

Having dinner in the shared kitchen varies week. Every dwelling also have their own fully equipped kitchen

The development was co-designed by ar chitects and future residents, which allowed for a level of cus tomisation of the dwellings and created a diversity of sizes and internal layouts.

Since the project is located at the intersec tion between two walkways, the local res idents will cross the project, on their way to, for example, the bus stop or the shop ping center across the street. In this way, they can get in touch with the inhabitants of Wandelmeent

Every weekday morning at ten o’clock there is coffee in the meeting room, an nounced by a resident who walks on the street with a bell. There is always coffee at half past six on Wednesday, Friday and Saturday nights. Everyone is responsible for the coffee every ten weeks and ac cording to a rolling schedule, you are also responsible for keeping the common ar eas clean

64 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U R E

Perspective of the common kitchen

Perspective of the common kitchen

65

H O U S IN G TYPE S // NEI G HB O URH OO D// WANDELMEENT Floor 1 Floor 2

Design regulations & constructionIm p lementatio n

The houses are characterized by an arc shaped roof made of precast concrete elements.The woodfacade above the masonr y is stained bright red. The doors and windows with 15 cm wide window wood all around are brightly colored, yellow, orange, blue, green, red. All kinds of details have been developed with residents.

Pieter Weeda, the architect who designed the complex in consultation with the future residents, was ver y clear. All facades and window frames must be red. His idea was approved and the wooden facades were painted in the color Wandelmeent Red.

Ever yone could choose the color of the windows in their own house from blue, yellow, green or orange. The cluster had to decide the color of the windows in the common kitchen. All the doors to the clusters were painted red. Pieter reserved blue for the doors of the common buildings to separate the appearance from the clusters.

Since the project were codesigned by the architect and the future residents it led to a great diversit y in the layout of the plans as well.

The interior walls were delivered untreated and could be wallpapered or painted as desired.

On Only y two wo of t the e hooususeh e ol o ds s avve e in inststanant ac acceces to the he comommomon ki kitcchehen/n/di d ni ning ng ro roomom, , thhe e re rest st havave e to entnter er frorom ou outtssididee.

On Only y two wo of t the e hooususeh e ol o ds s avve e in inststanant ac acceces to the he comommomon ki kitcchehen/n/di d ni ning ng ro roomom, , thhe e re rest st havave e to entnter er frorom ou outtssididee.

66 PR OT OTYPE S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

Buildings uildings

1 Roof

prrecast concrete. Copper on top.

2 Interior Thhe project were code signed by the architect and thhe future residents and that led to a great diversity in the layout of the plans.

3 Structure Cooncrete

4 Exterior walls Bricks and wood

5 Windows

15 cm wide window frame in bright colours

67H O U S IN G TYPE S // NEI G HB O URH OO D// WANDELMEENT

CO-ARCHITECTURE IN CO-HOUSING

Co-Housing: a brief Introduction relation to conventional housing. The be collective, communal, collaborative or co operation (Vestbro), but implies that this type of housing offers more of these as pects than ordinary housing. In this publi cation, we will explore what has constitut ed cohousing through history by studying some examples from different eras With the book ”Living together” edited by Dick Urban Vestbro as a starting point, we have examined ten prototypes that inter pret cohousing differently. Vestbro sug gests a model to describe different types of cohousing, originally proposed by Do lores Hayden. The model consists of three different categories, which are:

Ideal life

Rational society

Ecological

However, the concepts are not perfectly distinctive, some of the prototypes have features from all three categories. But they have been a tool to distinguish their

These prototypes have often started as a reaction to contemporary society and consequently tell us about the develop

ment of cohousing through histor y. From the ideas of utopian communities as a reaction to the industrial revolution, and the rational servicehouses that enabled women to work, to the birth of the envi ronmental movement that combined col laboration and community with ecological ideals. These new ideas about living and dwelling have pushed society forward by challenging its conventions. The outcome of the prototypes that we have examined

since the beginning, some never got fur ther than paper architecture and some lasted for a limited time. Therefore, the prototypes do not only tell us about their contemporary society, but also about its development. For each prototype, we will discuss what made them successful or not, the reasons behind it, and what this tells us about society. We will also look at the architecture that enabled or hindered their development. What do the organi zation of buildings or rooms, the materi als and the construction tell us about the ideas of cohousing?

68 T HEME S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

69CO -H O U S IN G // CO -AR C HITE C TUR E

End of the industrial revolution

Shakers OneidaMonasteries

Robert Owen Charles Fourier

World War IThe first car

Kibbutzim

The gr

70 CO N C EPT S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE Collective housing (C

Godins familistère

T. Jeffeson’s Student housing

Apartment hotels (USA) Central kitchenCollec F

18001820184018601880190019101920

World War II

Environmental movement

reat depressionFall of the Berlin wallApollo 11

Smaller Communes

The Sea Ranch

CCP)

Cohousing communities

Eco- Villages

Oneida

Shakers

Kibbutz Understenshöjden Bofaelleskab (DK)

Self-work model 2nd half of life m.

ctive housing (SE)

Family hotels

Service housing (elderly)

Senior housing

19301940195019601970198019902000

The Sea Ranch

Ytterjärna Seminar

Kensal House Hässelby familjehotell

Rational society

Ideal life Ecological or other goals

71

CO -H O U S IN G // CO -AR C HITE C TUR E

CO-ARCHITECTURE IN IDEAL LIFE

Ideal life: a brief Introduction

The idea life movement within collective housing encompasses different types of communal living which all feature very

these different communities share. The central aspect about the ideal life mou vement is the focus of each community, on creating an environment to facilitate

by each group. In this way they all share the pursuit of different ideals, or common goals, than the rest of society surrounding them.

This leads to a common rejection of the social norms that were in costum at the time. Partly through having these distinct ideals, the communities are often forced to isolate themselves from the society they are surrounded with and create their very own, fully functioning community We traced back the ideal life movement within collective housing and found its

one being, also being the oldest, would be the religious one, leading us back to mon asteries and later to Thomas More. The other stream is a secular, utopian social ist movement with its starting point going back to thinkers like Charles Fourier, Rob

of course overlaps with the ideal of a ratio nal society

Examples that qualify themselves as “Ideal Life” communities can be found throughout histor y, although the concen tration of communities, present in the western part of the world, showed a de cline since through the 20th centur y to

this day. Therefore we have chosen three examples active in the 18th, 19th and 20th century respectively. We try to give a fair example of how an ideal life community can look like. The chosen examples dif fer on some important points but also

the section of ideal life mouvement is that indeed the prototypes chosen belong all to a larger mouvement which had differ ent communities. Therefore we always confront in one part the movement as a

are the Shakers, active between 1747 until ~1900, The Oneida, active between 1840 until 1880, and the Kibbutz which was founded around 1905 and still active to this day

the religious and the secular part of the ideal life mouvement we had to recognise that the pursuit of an ideal life through a community almost always goes hand in hand with spiritual thoughts and beliefs. Moving towards the more secular part of the ideal life we noticed a crossover, a transition with the Rational Society as well as the Ecological Movement

72 CO N C EPT S O F CO -AR C HITE C T U RE

73I DEAL LIFE // CO -H O U S IN G % ( ) ,. // 0 ( 1 2 // 0 34 /(5) ) /1/ ()( /( // 0 () 3( /6 4 ,(7) /1(/ ), ( 5(/ 4 1 8 ,9( 1 / () 1/(1 / %:7 -( 4 2 /70 6 7 / () 0 () 34 4 9 / 34 ?) 34 7 1 / () /( (, ) / -, / 8 ,( 7) (6 / B0/ ,7 7/ 7 ) ,( 7) C ) /) 7 / 5(/9 C ) / 1 / ) , % 14 (),( 7) / 4 / 4 )1/ 6 1 , C ) / B/,4 , 7/ D(/9

RATIONAL SOCIETY IN CO- HOUSING

Rational societ y regarding collective housing in architecture is an orientation concerned with technology to make the household more effective. Throughout histor y, it persuades a modern way of living in line with the political conditions at that time. Early examples of collaborative

product.

The orientation aimed to improve the standard for the large population concerned dwelling standards, leisure time and working conditions. The residents were not necessarily involved in the design process of the cohousing, they were rather seen as the users. Utopian ideals are the foundation of a rational societ y. The book Utopia written by Thomas More, challenging existing societal ideas in the 1500s, gave birth to what would later develop to collective housing. His vision deals with people coming together contributing to an

people so that they would have equal living conditions. And later also developed to the idea of production in connection with facilities.

During the 1930’s the question about the situation for women was raised. The domestic work was a restraint for women

to get a professional career. Through a collective organization of domestic work women should be able to prioritise their career. A new t ype of collective housing was introduced that consisted of individual apartments with some shared facilities and spaces. There was of ten a large supply of services in the building, such as kindergarten, shops, a manned laundry room and a restaurant ( Vestbro 1968)