ISBN: 978-91-8040-418-1 Trita: A-2223

KTH School of Architecture 2022 Printed by US-AB

Student Editors: Axel Åström Yang Xu Editors: Erik Stenberg Jelena Mijanovic

Teachers

Students

Katharina Maria Bitschnau, Gottfrid Björk, Robert Capaldi, Yingnan Chen, Maria Dalmer, Alice Erkhammar, Tinghao Feng, Isabella Fyfe, Ludvig Göktürk, Natalia Hedström, Fadri Horber, Torulf Jörnholm, Timothy Charles Lewis, Gabriele Lipskyte, Robert Magnusson Årebo, Robbin Modigh, Maja Nordblom, Eszter Olah, Claudia Pavilanis, Hongting Xu, Yang Xu, Yuchao Zhang, Axel Åström

4 MassMassHousingHousing Studio

Erik Stenberg Jelena Mijanovic

Table of contents

The answer is mass housing 6

LCA Timeline, housing units 8

Doughnut Diagrams 10

Norra Kvarngärdet 13

Background 14 Building Structure 16 Use & Living Conditions 18 Is it Sustainable? 20

Karl Marx-Hof 23

Historical context 24 Funding 25 Construction 26 Living in Karl Marx-Hof 27 Housing for all 28 Housing evolution 29 Refurbishments 30 Vienna today 31

Vollsmose 33

Planning 34 Construction 35 Life in Vollsmose 36 Renovations 37 Deconstruction 38 Reuse 39 Co-Housing 40 Vollsmose past - present - future 41

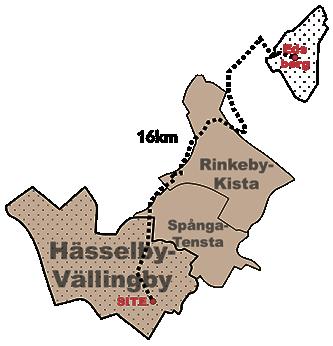

Vällingby 43

Historical context: the first ABC city in Sweden 44 Construction 45 Living in Vällingby 46 Maintenance 48 Situation today 50

Gottsunda 53

Historical question 54 Different features of Gottsunda 55 Economics features 56 Two cases — 57 Renovation case study 58 Question for today 59 Future development 60 Future housing 61

Bagarmossen

63

Preconditions 64 Constructions & materials 65 Use - social 66 Use - ecological 67 End of life - social/economical 68 End of life - ecological 69 Ideas for the future Bagarmossen 70 A changing population? 71

Bijlmermeer 73

Context 74 Modernism in Amsterdam 75 Construction 76 Use 77 Renewal 78 Renovation 79 Holding on to the dream 80 Today’s status 81

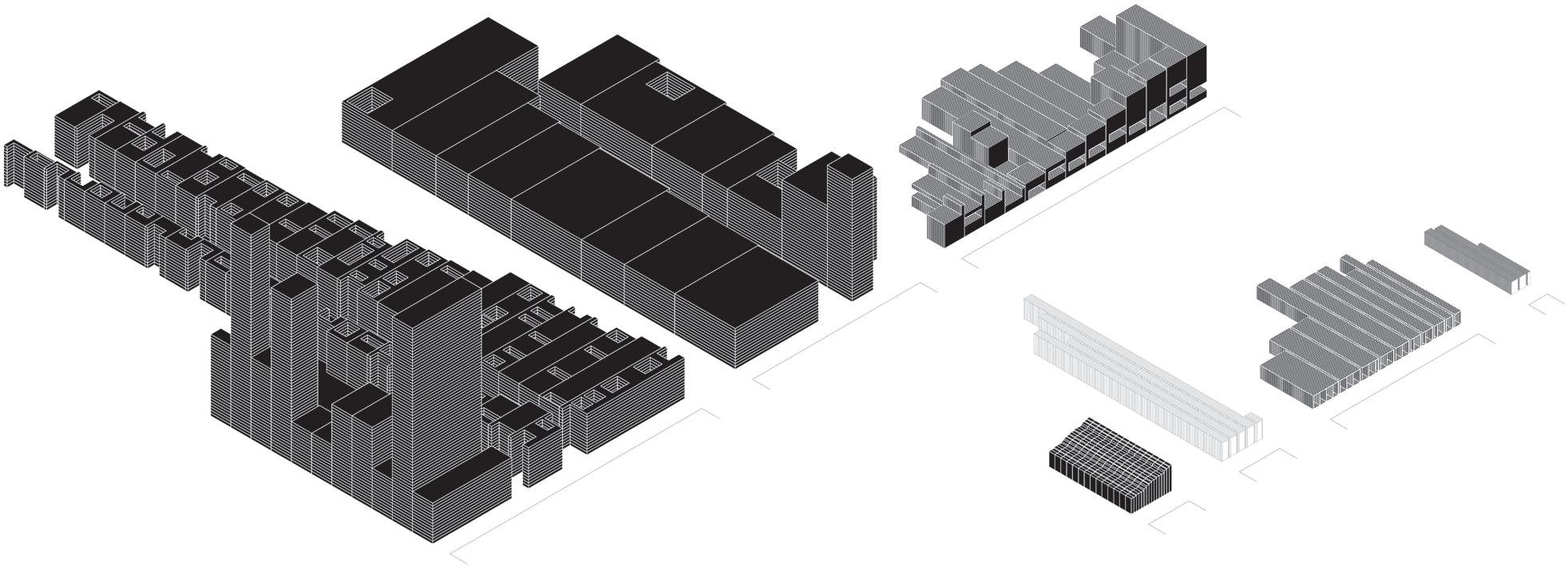

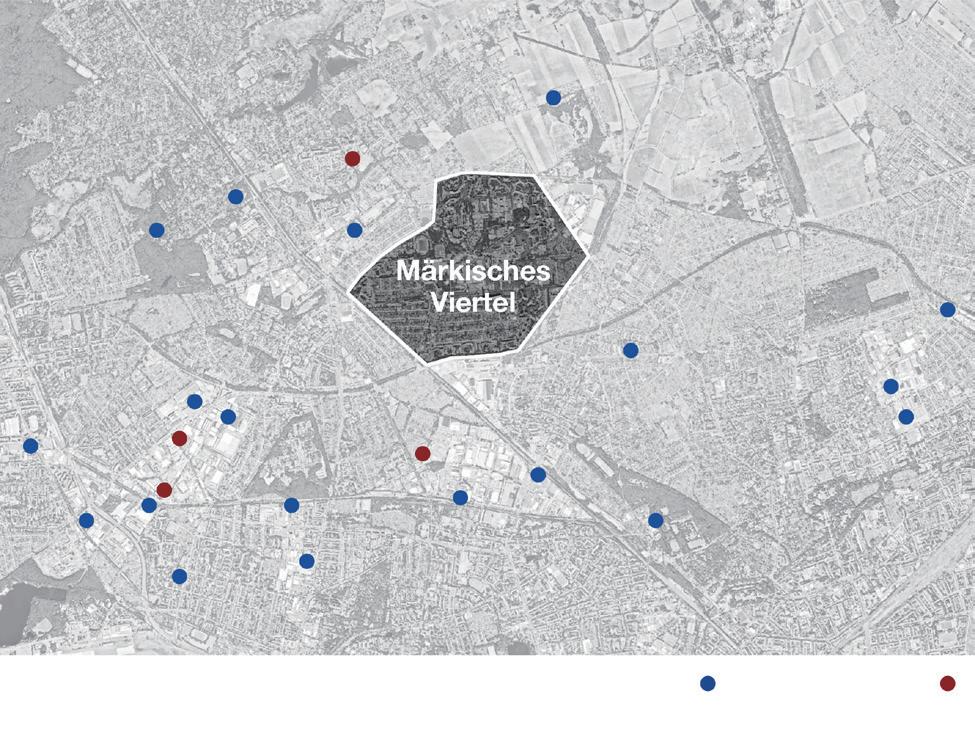

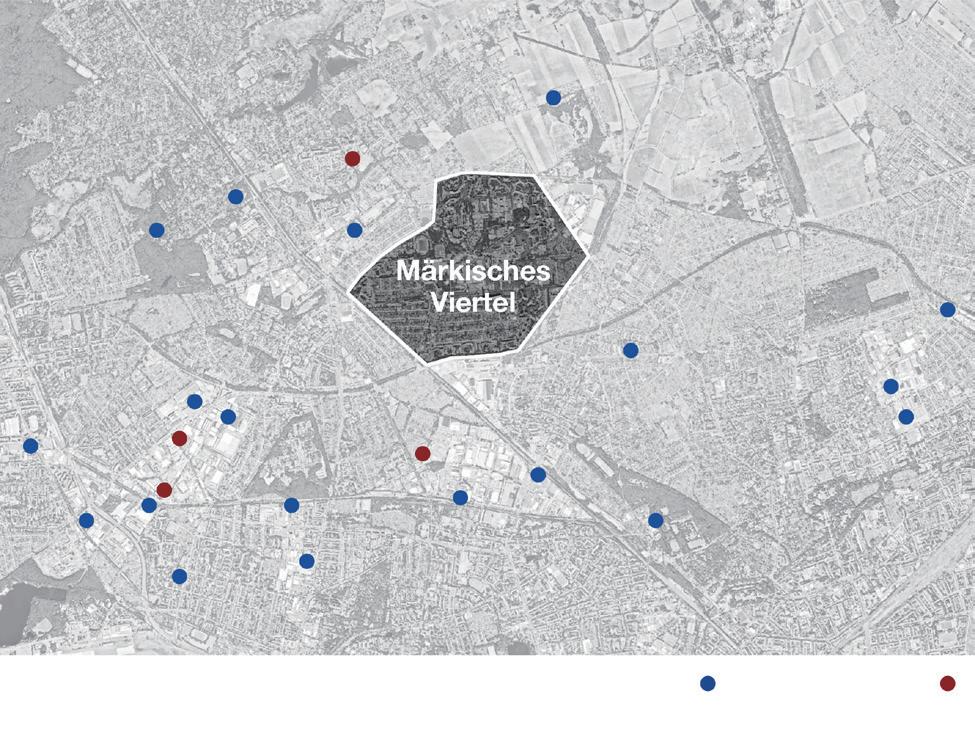

Märkisches Viertel 83

Timeline 84 Construction 85 Living in Märkisches Viertel 86 Renovation 88 Conclusion 90 Potential 91

Bibliography 93

Appendix 102 Norra Kvargärdet 102 Biljmermeer 106

5 Mass Housing

Introduction

Muddy and Motley Mass Housing for Millions of Homes

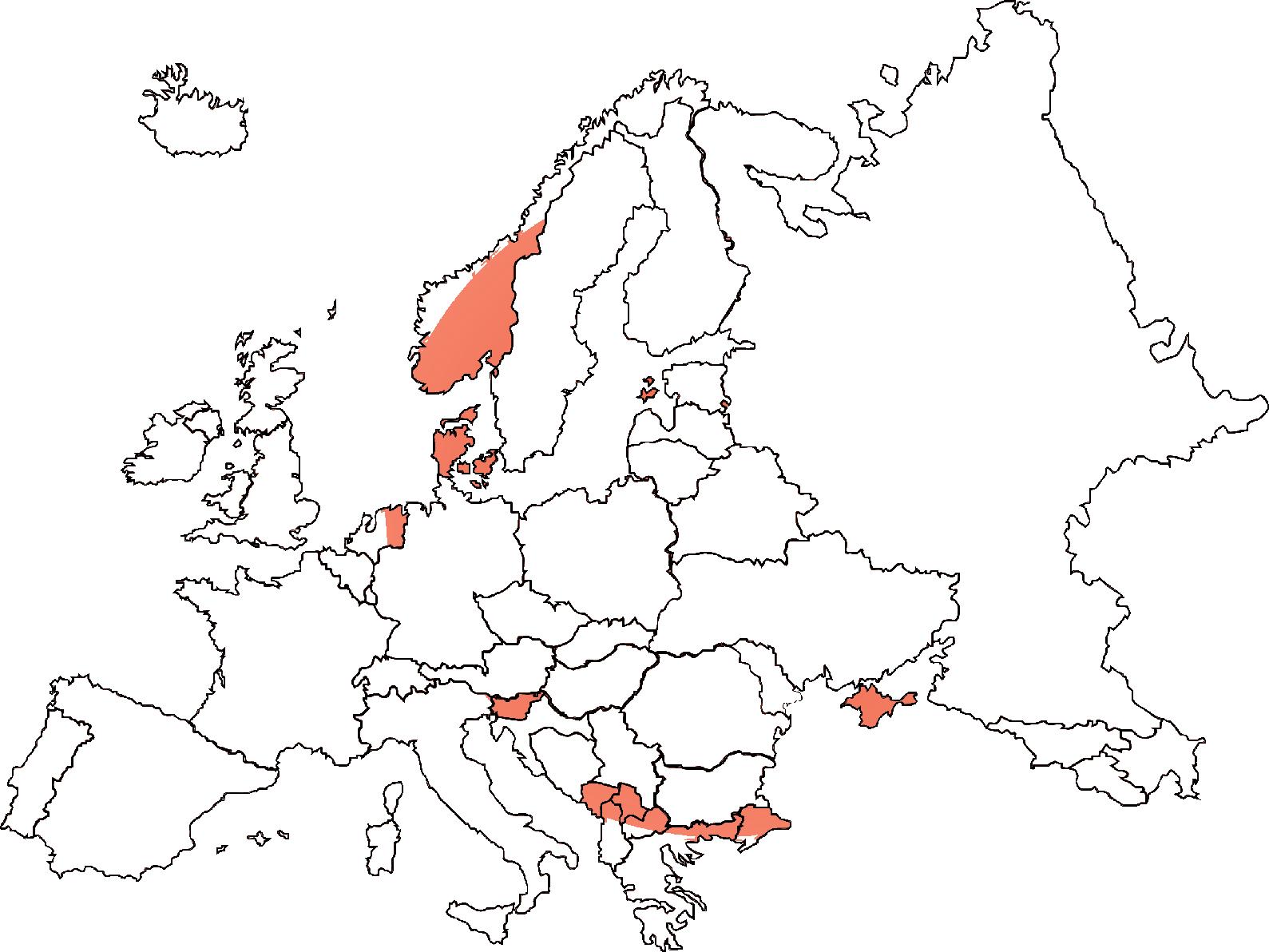

In the opening remarks of the International New Town Institute 2020 conference Taking Back Housing, Director Michelle Provost wondered why “...social housing, or affordable rentals, are now seen to be for losers…”? This remark can be understood as a critique of current European (and possibly global) housing practices where market driven solutions have not been able to develop adequate mass housing solutions for all. The conference went on to present a number of novel initiatives and critical perspectives on providing housing alternatives for a more and more desperate and growing group of urban dwellers. Why is an increasing number of groups of residents of the contemporary city left without the reasonable and qualitative choice that mass housing used to provide? This, the contemporary version of the Housing Question, is what we will consider in the Muddy and Motley Mass Housing for Millions of Homes Studio (4M2H) at the KTH School of Architecture throughout the academic year 20222023.

During the first project of the Fall Semester 2022, the students of 4M2H have explored mass housing solutions for a sustainable urban future through revisiting a selection of mass housing areas, such as the historical ABC-City Vällingby in Sweden and the large urban estate Märkisches Viertel in Berlin. We have looked at both Swedish and international examples of building mass housing to solve the

conflicting needs and desires of housing for the masses. This will shape a foundation for our future studies of guiding principles of mass housing during the 20th century. By interpreting living conditions and structural systems, we confronted issues of dwelling, domesticity, culture, tectonics and construction. An important aspect in the first project was the documentation and communication of our research findings. The methods and concepts of sustainability in mass housing were the broad focus and starting point. The narrower scope was to look at mass housing solutions that address the topics: Housing for All, Affordable Housing, Co-Housing, and Social Housing. The work was structured in weekly assignments looking at the social, economic, and ecological aspects of sustainability. The student’s findings were then organized following the building’s or residential areas whole life cycle; starting with the understanding of the contextual framework that made the projects possible, raw material extraction, construction, use/ living in the building, end-of-life and even looking into potential re-use in a new building project. These do not necessary mean cataloguing in an ordinary sense, but more as ways of exploring representation in drawings and model making in order to communicate research.

6 Mass Housing

What you are looking at is the catalogue of the students’ collective work for the first seven weeks. It takes its title from a lecture presented to the Housing Studio last academic year by Chalmers’ Professor Emeritus Claes Caldenby. He framed the history of Co-housing as an answer in search of its question. Over time, Caldenby explained, there have been a number of societal and architectural questions that have led to the same answer: Co-housing. How can we organize housing more efficiently? How can we make housing more sustainable? How can we promote more social interaction and use fewer square meters per person? We posit that Mass Housing has had the same fate and have re-framed the title of the lecture to reflect this perspective. Throughout the twentieth century, Mass Housing was the constant answer. Why has mass housing held this answer for so long and what are the contemporary questions?

During the remainder of the semester, the studio will continue to map an understanding of the history of mass housing architecture from a material, tectonic, structural and technological standpoints as well as engage in questioning the architect’s role in designing new living environments and its effects on society. With the contemporary housing question and sustainability as a springboard, the studio will deepen the understanding of how to develop the existing built environment and therefore limit the effects of new architectural production on our

environment. By analyzing and investigating how and why technologies such as industrialization and pre-fabrication have performed over long periods of time and how individual and common living conditions have been designed and adapted over time, we will be able to deconstruct conceptions of sustainability, mass housing and the role of the architect.

7 Introduction

“ The Answer is Mass Housing, but what is the Question?”

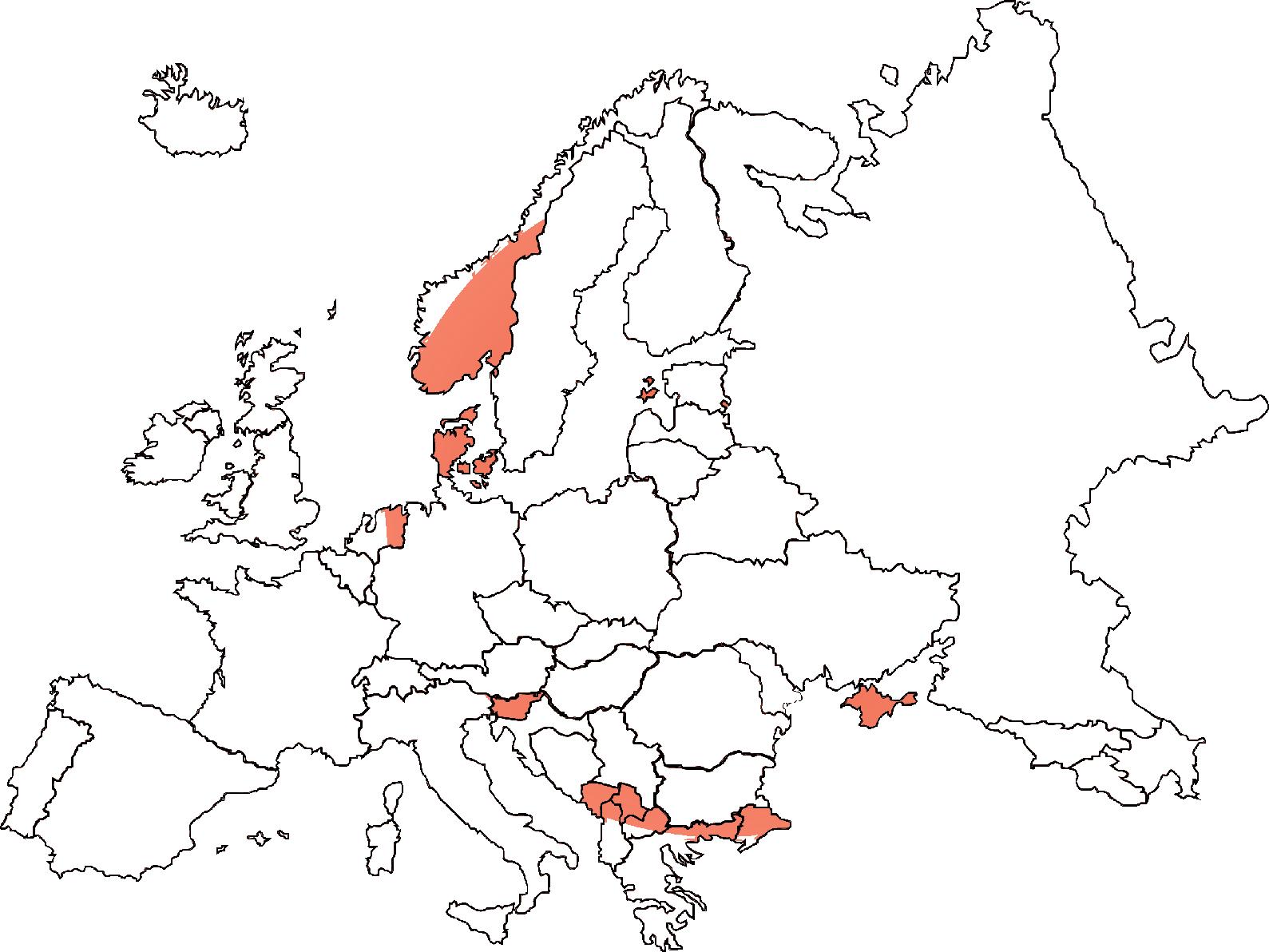

Norra Kvarngärdet Sweden WAR

Karl Marx Hof Austria

Vollsmose Denmark

Vällingby Sweden

Gottsunda Sweden

Bagarmossen Sweden

Bijlmermeer Netherlands

Märkisches Viertel Germany

8 Mass Housing

LCA Timeline, housing units

DESTRUCTION

0

A Construction B Use C Renovation World

II 1930 1940 1950 GSEduca iona Ve sion

OTTO WAGNER’S VIENNA LOSS AND COLLAPSE OF AUSTRO-HUNGARIAN EMPIRE OCCUPATION

Context LCA (Life Cycle Assesment) concept was took as reference for the stages.

War

POST WAR

9 LCA Timeline, Housing Units Global Oil Crisis Ukraine Crisis 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 FALL OF THE BERLIN WALL SEPARATION OF GERMANY CENTRUM SOLD TO PRIVATE REAL ESTATE COMPANY SURINAMESE INDEPENDENCE PLANE CRASH DEMOLITION GHETTO LIST RENTAL CRISIS WAR REFURBISHMENT RESTAURATION BECAME PROTECTED HOUSING AREA RENTING PRICES INCREASED NEW DEVELOPMENT PLAN 1447 housing units 1550 housing units 3638 housing units 3885 housing units 5000 housing units 5767 housing units 13000 housing units 17000 housing units MILLION PROGRAM

MARX HOF

MARX HOF

10 Mass Housing Social Fo u n d a t i o n G r eenh ouse gasemission Climate Freshwater Consump t io n Lsso fo ytisrevedoiB noitatserofeD retawdnuorG oP l ul t oi n E c ological Ce i l i n g emocnI dE u c a t ion Living Condition W o r k

Social Fo u n d a t i o n G r eenh ouse gasemission Climate Freshwater Consump t io n Lsso fo ytisrevedoiB noitatserofeD retawdnuorG oP l ul t oi n E c ological Ce i l i n g emocnI dE u c a t ion Living Condition W o r k NORRA KVARNGÄRDET Social Fo u n d a t i o n G r eenh ouse gasemission Climate Freshwater Consump t io n Lsso fo ytisrevedoiB noitatserofeD retawdnuorG oP l ul t oi n E c ological Ce i l i n g emocnI dE u c a t ion Living Condition W o r k KARL

Social Fo u n d a t i o n G r eenh ouse gasemission Climate Freshwater Consump t io n Lsso fo ytisrevedoiB noitatserofeD retawdnuorG oP l ul t oi n E c ological Ce i l i n g emocnI dE u c a t ion Living Condition W o r k GOTTSUNDA No Data Doughnut Diagrams Social Fo u n d a t i o n G r eenh ouse gasemission Climate Freshwater Consump t io n Lsso fo ytisrevedoiB noitatserofeD retawdnuorG oP l ul t oi n E c ological Ce i l i n g emocnI dE u c a t ion Living Condition W o r k BAGARMOSSEN Social Fo u n d a t i o n G r eenh ouse gasemission Climate Freshwater Consump t io n Lsso fo ytisrevedoiB noitatserofeD retawdnuorG oP l ul t oi n E c ological Ce i l i n g emocnI dE u c a t ion Living Condition W o r k NORRA KVARNGÄRDET Social Fo u n d a t i o n G r eenh ouse gasemission Climate Freshwater Consump t io n Lsso fo ytisrevedoiB noitatserofeD retawdnuorG oP l ul t oi n E c ological Ce i l i n g emocnI dE u c a t ion Living Condition W o r k KARL

Social Fo u n d a t i o n G r eenh ouse gasemission Climate Freshwater Consump t io n Lsso fo ytisrevedoiB noitatserofeD retawdnuorG oP l ul t oi n E c ological Ce i l i n g emocnI dE u c a t ion Living Condition W o r k GOTTSUNDA No Data

BAGARMOSSEN

11 Doughnut Diagrams Social Fo u n d a t i o n G r eenh ouse gasmission Climate Freshwater Consump t io n L sso fo ytisrevedoiB noitatserofeD retawdnuorG oP l ul t noi E c ological Ce i l i n g emocnI dE u c a t ion Living Condition W o r k VOLLSMOSE Social Fo u n d a t i o n G r eenh ouse gasemission Climate Freshwater Consump t io n Lsso fo ytisrevedoiB noitatserofeD retawdnuorG oP l ul t oi n E c ological Ce i l i n g emocnI dE u c a t ion Living Condition W o r k VÄLLINGBY Social Fo u n d a t i o n G r eenh ouse gasemission Climate Freshwater Consump t io n Lsso fo ytisrevedoiB noitatserofeD retawdnuorG oP l ul t oi n E c ological Ce i l i n g emocnI dE u c a t ion Living Condition W o r k BIJLMERMEER Social Fo u n d a t i o n G r eenh ouse gasemission Climate Freshwater Consump t io n Lsso fo ytisrevedoiB noitatserofeD retawdnuorG oP l ul t oi n E c ological Ce i l i n g emocnI dE u c a t ion Living Condition W o r k MÄRKISCHES

VIERTEL

Norra Kvarngärdet

Location: Uppsala, Sweden Size: 1447 units

Years of construction: 1962-1967

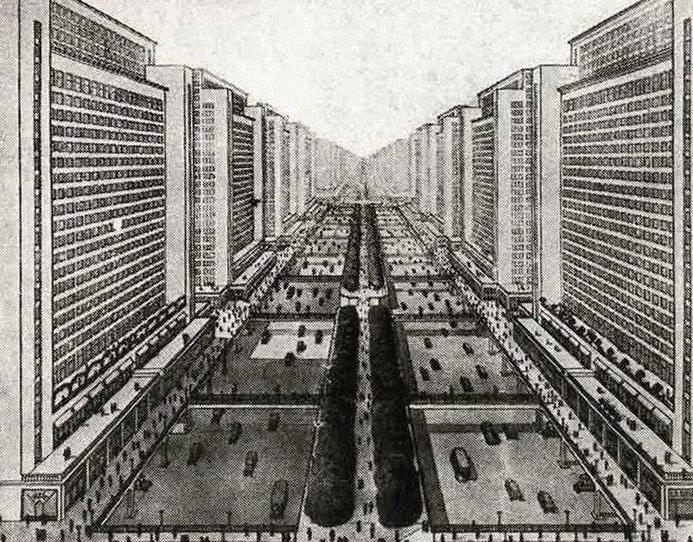

Case study by: Katharina Bitschnau

Gottfrid Björk

Fadri Horber

Background

Norra Kvarngärdet was built on the outskirts of Uppsala on what was then countryside and farmland. The entire area was designed by AnckerGate-Lindegren but mainly drawn by Stig Ancker on the order of the municipal housing company, Uppsalahem. The area was built with apartments and a small center consisting of a school and a grocery store. Land costs back then were low as it was far from the city center. Originally, the idea was to build the area with 3-7-storey houses, which was common during the Million Program era. This plan changed since the ground conditions were not suiting. The soil was soft, which meant that they decided to build low rise houses instead, with a new technique where the houses “floated” on the ground. They did so in order to avoid piling into the ground and keeping the costs to a minimum.

This was the first housing area in Sweden built as low and dense. This in turn gave the houses a preservation order, which means that the houses are protected from new exploitation.

2. 5 km ra dius

Figure 1.2.

Mass Housing from the 1960s

Figure 1.1.

Uppsala

14 Mass Housing

Historical building material suppliers (Aerial photo from 1975; https://www.lantmateriet.se/)

Upplands Betong (Photo by Evert Skirgård)

S:t Erik factory since 1909

Upplands Betong

Norra Kvarngärdet

Uppsala has grown rapidly, which has also led to Norra Kvarngärdet being considered as a central area today. Therefore, in recent years, Norra Kvarngärdet changed significantly. A number of non protected areas have been repurposed in order to create more space for new dwellings. For example, the former car parks from the 1960s are now a series of new residential buildings. The supermarket in the center was demolished and replaced by highrise apartment buildings. These areas were not part of the listed assembly, which made it possible to build new in an area that don’t have a preservation order. With the higher land costs today, it is more profitable to build higher and to undergo expensive ground piling. The new and taller houses form a “ring” around the historical area, which leads to visual segregation (fig.1.5).

Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.4.

1.5.

Norra Kvarngärdet

1960s, section west / east (Illustation based by Jolirak 2013-08-23)

Present, section west / east (Illustation based by Jolirak 2013-08-23)

15

Figure

Photo from site, 2022: looking at the new higher neighbourhood (Photo by Katharina Bitschnau)

Parking lots

Present

New Housing development

Housing

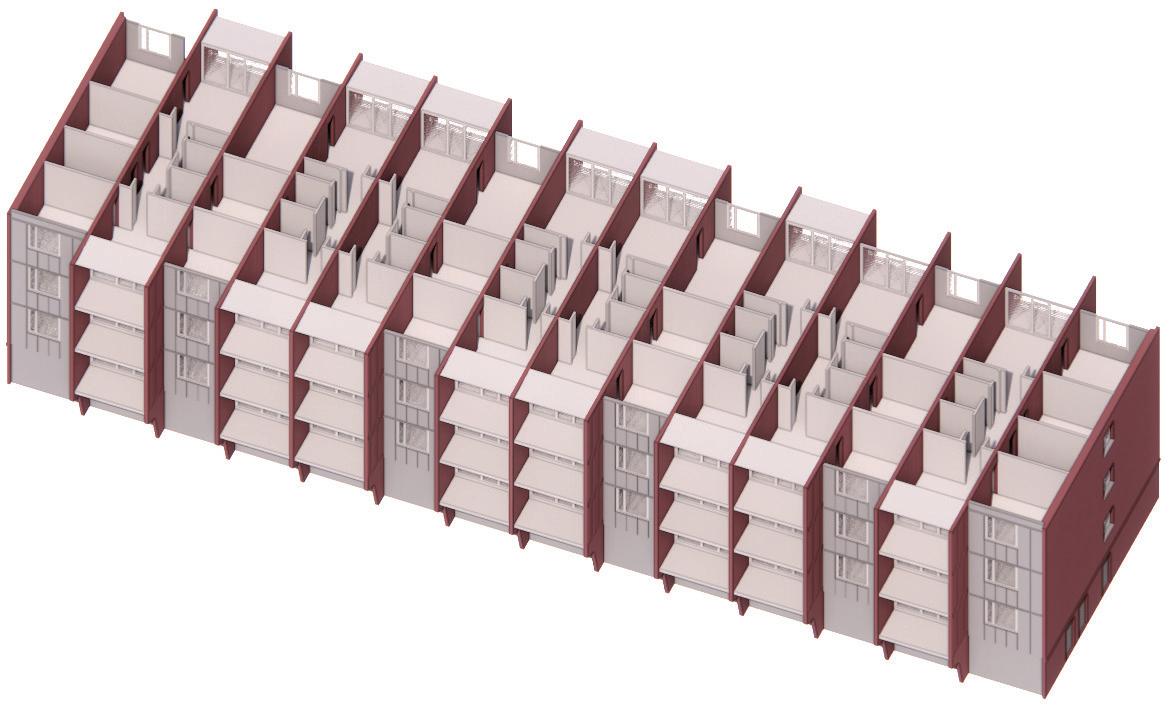

Building Structure

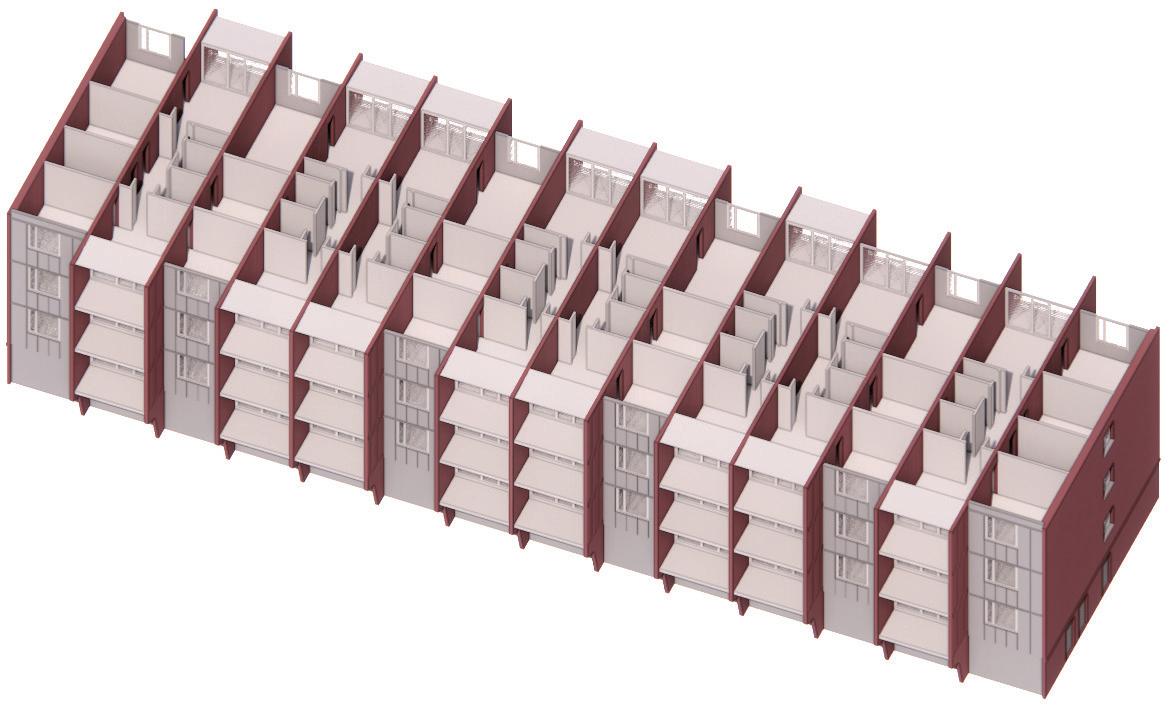

The structure of the low rise buildings is composed of 2-storey prefabricated concrete columns on the exterior wall. 1-storey prefabricated concrete in the inner part of the building. The concrete slab separating the two floors is also composed out of prefabricated concrete. The roof structure is composed out of prefabricated wood trusses, making it light-weight, thus interior columns are not needed for the upper floor. The columns are the main supports for the building, making the layout highly flexible if needed. The walls dividing the units, as well as the interior partitions are not loadbearings, thus the units and the entire floor can be altered as needed (fig.1.6, fig.1.7 & fig. 1.8).

The raw material that were used on these houses are for the most part locally sourced, in the vicinity of Uppsala (fig.1.2). Since it was housing for all, the cost had to be as low as possible. Saving money on transportation is a big factor in the production of locally sourced material. Prefabrication of certain elements also reduced the construction time-line, thus having a positive impact of the cost of the projects.

Figure 1.6.

Mass Housing from the 1960s

Figure 1.7.

Figure 1.8.

Detail based on (AGL Arkitekter plans from Archive)

16 Mass Housing 12 7 7 26

12 cm Brick 7cm Mineral wool insulation + wood structure 7cm Lightweight

F

concrete

açade structure

Revit model based on (AGL Arkitekter plans from Archive)

Nybygge på Kvarngärdet (Photo by Uppsala-bild 1963)

The structure of the new 5-storey buildings consists of prefabricated load bearing concrete walls, as well as prefabricated concrete floor slabs. The prefabricated load bearing exterior walls consist of the insulation as well as the façade material (fig.1.9, fig.1.10 & fig. 1.11). This strategy speeds up the whole construction process, but limits the overall flexibility of the units. Since the walls are loadbearing, the flexibility of each floor, and of the units itself are very limited.

As the building industry is on a more global scale, we presume that most of the elements used are not locally sourced, taking advantage of the globalization of the industry, this helps to reduce the overall cost of the projects. With lower construction cost, the units can be sold at a competitive rate, emphasizing profits over living conditions.

Figure 1.9.

Figure 1.10. Figure 1.11.

17 Norra Kvarngärdet 5

25 10 40 5 25 10 40

5 cm Façade

10 cm Mineral wool insulation 25cm Concrete

F

Present Housing

material

panels

açade structure

Detail based on observations Revit model based on observations

Construction process (Street View from Google Maps 2017)

Use & Living Conditions

In the low-rise housing area from the 1960s, more emphasis was paid on the green spaces and common areas around the houses. This means that care was taken at the planning stage to ensure that there are plenty of communal spaces. This is most evident in the northern part, where there is a clear traffic separation according to SCAFT, where the outdoor areas have been more clearly separated from car traffic to create a nicer and safer outdoor environment. The ground coverage for the low and dense buildings is only 36%. The low and dense buildings give the impression of living in detached family houses, so that one has the feeling of not being in the centre of Uppsala (fig.1.12).

Mass Housing from the 1960s

Typical 3-room apartment Each unit has on avarage 75 m2 to 80 m2 0

Apartment size 75 m2

Rent per month 8 400 SEK Rent per m2 1 380 SEK Owner Stena Fastigheter Energy 132kWh/m2year consumption

Präsentation A3

The older houses also have a much lower rent than the new apartment buildings next to them. Moreover, the lower buildings in general offer larger flats and more common areas, which create a better living environment. Originally, the flats were very affordable. However, the recent renewal has pushed the rent up significantly. It increased by up to 60%. This is still slightly below average, but it has put a lot of strain on the tenants and some have been forced to move out (fig.1.13).

Related common outdoor area

Common outdoor area includes: Court yards Playgrounds Parking lots Service streets

AREA: 75 m2

Figure 1.12. CAD drawings based on (AGL Arkitekter plans from Archive and Aerial information from Eniro.se)

Diagram information based on (Fastighetstidningen and Uppsala Kommun)

Figure 1.16.

18 Mass Housing

Vog Landscha sa ch ek en AG p CH 8006 Zü h P o ek numme P o ektname Zür ch Datum

2019 Ma VECTORWORKS EDUCATIONAL VERSION VECTORWORKS EDUCATIONAL VERSION

Planvorlage

1:1 P0000 01 01

200 400 600 800 1000 1200

Mass housing Norra Kvarngärdet owned by Stena Fastigheter

Older housing in Uppsala in general Figure 1.13.: Rent in SEK per m2 / year 2200

1400 1600 1800 2000

The new housing development next to the Million Program area from the 1960s has a very different approach when it comes to terms of space and land use. The buildings are taller to maximize the number of square meters that can be built on the plot and they are placed much closer together. As a result, the total ground coverage is by 62%, which means that there is barley any outdoor space left. In general they create a more urban environment with shops on the ground floor and flats on the upper floor, which is unlikely for this neighborhood and more typical for the central parts of Uppsala (fig.1.14).

The rents for the newly built apartments are very high, while having smaller apartments and outdoor areas. This means that tenants get much less for what they pay for. Furthermore, the apartment rents are also significantly above the average rental prices across Uppsala. However, the queue for the new flats is about half as long as for the old housing, which states that affordable housing is still high in demand and that only a fraction of people can afford this kind of new housing. Respectively, this new housing development contradicts in many ways the original idea of the Million Programme, which focused on affordable housing and high quality outdoor areas and green spaces (fig.1.15).

Typical 3-room apartment

Apartment size 62 m2 Rent per month 11 130 SEK Rent per m2 2 160 SEK Owner Stena Fastigheter Energy 123kWh/m2year consumption

Präsentation A3

AREA: 75 m2 AREA: 62 m2

Related common outdoor area

Common outdoor area includes: Court yards Playgrounds Parking lots

Figure 1.14.

CAD drawings based on (Uppsala Bostadsförmedling)

New housing in

New

Each unit has on avarage 8 to 9 m2 0

owned by Stena Fastigheter + 64% + 62%

2200 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1400 1600 1800 2000

Figure 1.15.: Rent in SEK per m2 / year

Diagram information based on (Fastighetstidningen and Uppsala Kommun)

Present, Cross-section west / east (Illustation based by Jolirak 2013-08-23)

19 Norra Kvarngärdet

GSEducationalVersion V g L d h h k AG St b h 7 CH 800 Zür ch P o ektnummer Pro ek name Zür ch Da um

1 P0000 01 01 2019 M VECTORWORKS EDUCATIONAL VERSION VECTORWORKS EDUCATIONAL VERSION P l a n v o r l a g e P r ä s e n t a t i o n

VECTORWORKS EDUCATIONAL VERSION

Planvorlage

A 3

Norra Kvarngärdet

housing in Uppsala in gerneral

Present Housing

Is it Sustainable?

In the comparisons between the new dwellings and the mass housing from the 1960s, the findings are that the older neighborhoods are more sustainable than the newer ones. Firstly, they are more spacious both when it comes to the apartment sizes as well as the outdoor areas. This in turn creates better living conditions for its residents, while being more affordable than the average housing in Uppsala. However, the recent renovation led to a significant rental increase. To ease the burden for the tenants, they came up with a schedule to spread the rental increase over a 3 year period. Consequently, when rents are raised dramatically, the issue arises that the residents are pushed out of the city center, increasing the pressure on affordable housing to the outskirts. This has led Norra Kvarngärdet to become more segregated, as affordable rents are no longer viable. Secondly, these houses are protected so there has not been any major changes to the façades, and the owners are forced to renovate rather than to replace. This reduces material consumption and the works taken place are more economical and sensible. Thirdly, the buildings are built with columns and slabs since only the columns are load-bearing, it becomes much easier to move interior walls, this provides a more flexible design that makes adjustments easier and can be tailored to the users needs. This also allows

Figure 1.18.

Mass Housing from the 1960s

the interiors to be changed throughout the years which is especially important as the exterior of the houses are protected. Finally, we would argue that the initial energy consumption during construction of Stig Anckers’ buildings is significantly lower because materials are sourced locally. The construction methods in regards with materials were efficient and with the recent renovations, the running energy consumption could be reduced, holding up to current industry standards (fig.1.17 & fig.1.18).

nergy consumption

iousness afford ability

adabtabi

durability

Figure 1.17.

material sourcing

Diagram based on (Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics)

20 Mass Housing

Photo from site, 2022: Courtyards of the 1960s housing (Photo by Katharina Bitschnau)

GSEd V e

s p ac

l i t y

By observing the new housing development, it is clear that it cannot compete with the neighboring past mass housing scheme in the following aspects. Firstly, the apartments are in general smaller along with the outdoor areas because the new development is built to densify the area as a whole, while taking away precious greenspaces from Norra Kvarngärdet. Since these apartments are newly built, the residents are expected to pay higher rents, even though they are offered less living space. Secondly, the new buildings are not protected, that means that more changes can be made to the exterior, and are subjected to be demolished and re-built in the near future. The new built neighborhood, has a prefabricated load-bearing wall and slab construction. This system does not differ between load-bearing and space dividing elements. Therefore, these apartments are rather static. That makes it difficult and expensive to change their layouts. As a result, tenants are more likely to move out, if their living situation changes. This limits the possibility to accommodate the ever changing needs of the tenants. Thirdly, for the most part, the new façades are not built with the same quality of materials and will probably need to be renewed after a shorter period of time, one can also assume that the materials and elements used for the interior also have a lower quality, resulting in more frequent

Figure 1.20.

Present Housing

renovation processes. Finally, the materials are not sourced nor manufactured locally, the globalization of the construction industry leads to higher greenhouse gas emissions, that arise from the transportation sector in order to bring the materials on site. Additionally, the energy performance of the new construction is barely better than the renovated housing from the 60s. In these projects, one would think that the buildings are energy efficient as a whole, however, it turns out that the mass housing of Norra Kvarngärdet, are almost at par, even though these projects were constructed 50 years apart. (fig.1.19 & fig.1.20).

Figure 1.19.

21

Norra Kvarngärdet

Photo from site, 2022: comparing the two neighbourhood (Photo by Katharina Bitschnau)

GSEd V

energy consumption

material sourcing

durabilit y s p a c iousness afford ability

adabtabi l i t y

Diagram based on (Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics)

Karl Marx-Hof

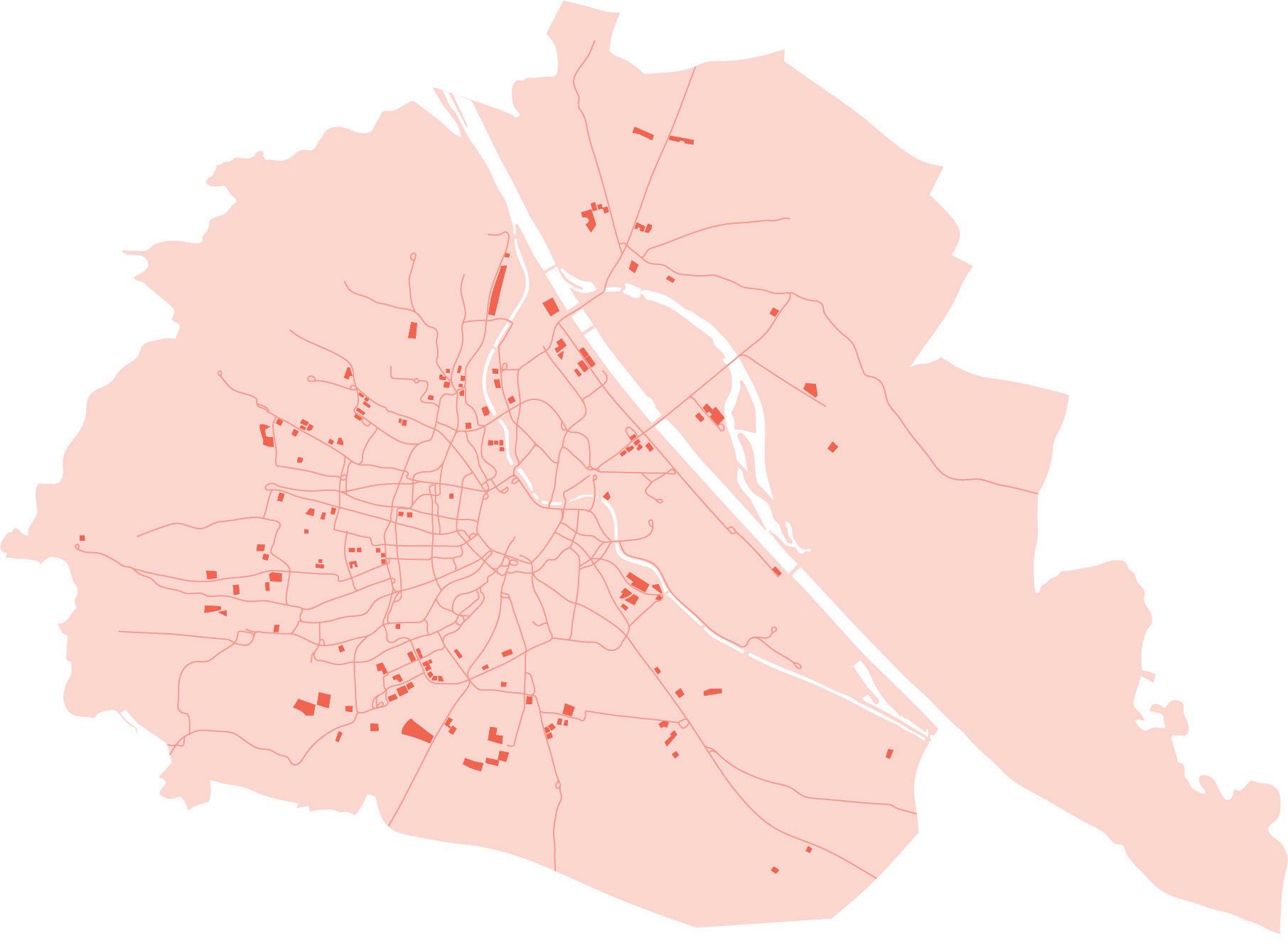

Location: Heiligenstädter Straße, Vienna, Austria

Size: 156,000 m², 1,382 units

Year of completion: 1930

Case study by:

Robert Capaldi

Robert Magnusson Årebro Axel Åström

Historical context

Figure 2.1.

Red Vienna

Post-war Vienna was a cultural melting pot where the working-class converged under poor living conditions. In 1919, the number of households in the city had increased, which in combination with stalled construction, galloping inflation and an influx of workers resulted in severe overcrowding and a widespread housing shortage. The standard of the existing housing stock was generally low, plagued by sanitary issues, poor air quality, excessive moisture, and lack of natural light. It was under these circumstances that the Social Democrats gained control of the municipal administration and declared housing as a fundamental need for all humans,

stating that ’’A good, spacious, and bright home is an important cultural factor in every person’s life’’.

Consequently, housing construction was declared a social product and integrated into social policy. The call for affordability and improved living conditions marked the start of a period known as Red Vienna, during which the Viennese municipality pursued a series of rigorous social housing programs across the city. The social democratic administration also introduced several taxation schemes aiming to stimulate the economy and raise the necessary funds for the planned municipal housing programs.

24 Mass Housing

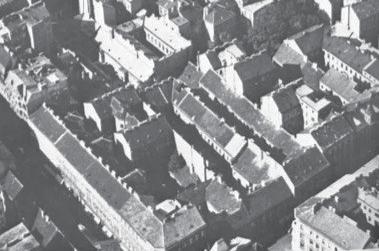

Municipal housing projects in Vienna, 1934 (Wienbibliothek.at, 2022)

The start of Red Vienna Breitner’s tax is introduced 1st housing construction program

Karl Marx-Hof is completed

Karl Marx-Hof

Vienna becomes a federal province

2nd housing construction program

The fall of Red Vienna

1919 1922 1923 1927 1930 1934

Funding

Factories produce materials for social housing built by government owned construction companies

Factories employ the working class

Government runs the factories, allowing them to control both working conditions and output

The worker pays tax to the government

The new housing increses the living standard of the workers

By taxing assets, the government activates stale cash, allowing it to re-enter the economy and boost production

Figure 2.2.

New taxation policy

In 1923, Hugo Breitner, the City Councilor of Finance, introduced a new tax system that taxed people progressively according to their expenditures. The new tax reform included a variety of different taxation schemes, designed to allocate the costs from the poor majority to the rich minority.

Breitner abolished the existing flat tax on rental units and replaced it with one that only affected the top 20 percent of rents. A progressive housing construction tax was also introduced, which was mainly aimed at larger properties and luxury apartments. These were taxed at extraordinarily high rates, while the

Government gets returns in form of rents, taxes and profits

The politics that built Karl Marx-Hof (2022)

working-class residences were left relatively untouched. Breitner’s taxes were also imposed on luxury goods to raise further funds for investments in social and public infrastructure.

Examples of taxes implemented

- Social wellfare fee - Car tax

- Concession tax - Pitch fee

- Entertainment tax - Horse fee

- Subletting fee - Sales tax

- Service charge - Utilities tax

- Meals and drinks charge - Advertising fee

Karl Marx-Hof

25

Rent relative to income

Pre-war Red Vienna

Figure 2.3

Figure 2.4.

The five year plan

Figure 2.5. Annual construction rate (10=10 000 units) (Blau, Eve, 1999)

In 1923, the municipality of Vienna announced a major housing development plan, consisting of 25 000 units over a five-year period. The construction goal was reached one year in advance and exceeded by 5 000 units in 1928. Therefore, the second five-year plan was initiated one year earlier than planned, in 1927, with a more ambitious goal of 6 000 dwellings a year until 1932.

To streamline the construction process, everything from metal fittings to windows and park benches was standardized and mass-produced. The standardization of building components was so

Resource extraction sites (Wienbibliothek.at, 2022)

Standardization streamlined production (2022)

extensive that even the dimensioning of bricks was affected. The construction material was transported by municipally owned trams and trains, which further reduced construction costs.

Raw materials were locally sourced, with the majority coming from within the city limits. Limestone was transported from quarries west of the city and bricks were produced in the southern district of Ober-laa. The close contact with production made the Viennese builders informed customers, allowing them to maintain a high standard of materials without going over budget.

26 Mass Housing Construction

1923 1922 1925 1927

Launch of second housing program 1929 1924 1926 1928 1930 1931 1932 10 20 30 40 50

Karl Marx-Hof

Limestone quarry Kaltbrunn Limestone quarry Hinterbrühl

Oberlaa brick kilns

Living in Karl Marx-Hof

Figure 2.6.

Figure 2.9.

Figure 2.7.

6 m

Figure 2.8.

Improved living conditions

The schematic plan of Karl Marx-Hof is related to the load bearing ‘heart-wall’ centrally located throughout the plan (Fig. 2.9). The structure is stabilized by the ‘towers’, which are shown in plan (Fig. 2.8) as rooms with a dept of 6 m.

Horizontal construction such as slabs, floors and roofs were standardized concrete elements, while the vertical structure was made in brick (Fig. 2.11). Although the bricks had standardized measurements (Fig. 2.10), this was a time-consuming method. A necessary element to increase labor and involve as many workers as possible in construction.

Figure 2.10. Figure 2.11.

Karl Marx-Hof drawings (2022)

Since its completion, Karl Marx-Hof has gone through a series of alterations and updates. Since the original plan was supported by communal baths the most natable is changes in the bath- facilities. The kitchen and bath has a determent relation to each other thanks to the original piping (Fig. 2.8).

The complex was originally designed to house around 5 000 tenants. However, as living standards improved, the apartments were inhabited by fewer people. Today, the number of tenants has decreased significantly to around 3 000. The households are generally smaller and home to 1 or 2 people.

Karl Marx-Hof

27

Housing for all

Figure 2.12.

Figure 2.13.

Courtyard space throughout the years (2022)

Site plan, Karl Marx-Hof (2022)

Figure 2.14.

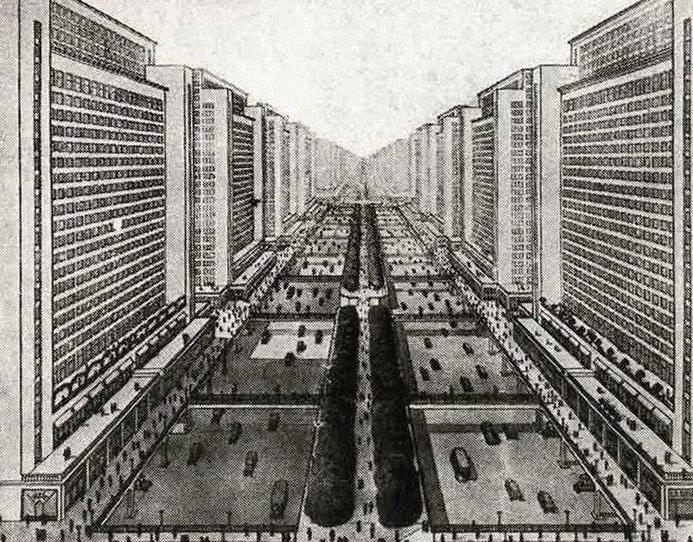

More light, more space

The issue of housing and its social significance had been approached during the 19th century. Largely at the mercy of speculation of land within the free market. The result was an exploitation rate of up to 85% of the plot. 83% of all apartments where small or minimal flats, 16 to 40m². 44% of the oneroom apartments housed more than 3 persons while 36% of the two-room apartments housed more than 5 persons.

Out of this inadequacy, the social democratic municipality stated a new agenda turning to new ideals regarding the social housing policy: That

Increased living space (2022)

Figure 2.15.

Ottakring, Vienna (Wulz, Fritz, 1979)

Figure 2.16.

Aerial view, Karl Marx-Hof (Wienbibliothek.at, 2022)

only healthy and sufficiently spacious housing should be built. This policy originated with a new ideal: 70% of the plot was to be left unbuilt.

In Karl Marx-Hof as much as 83% of the plot was left unbuilt. The shifting morphology of the volumes creates a variation within the urban context, as well as including the citys fabric, roads, gardens, within the structure. This creates a social and ecological urban strategy that holds until today in Vienna. The importance of social, sanitary and hygienic aspects changed from a technical aspect into an acitve socio-political stance.

28 Mass Housing

15 % 50 % 70%

Housing evolution

Dwellings before Gemeindebau

This survey, who reaches from the mid 1700-dwellings until the 1900-dwellings of Karl MarxHof, is investigating the inhabitants relationship to basic living qualities. Relationship to the street is of importance, hence it points out a citizens relationship to public space within the city.

Manufakturhaus (mid 1700) a common way of housing was related to place of employment, in this case a “Weinhauerhaus” a production factory for wine and spirits. The master and manufacturer was living in the front while the workers shared space in the back, facing the yard and the manure stack.

Rinnböckhof, (1864) A planned hosing facility for workers under the employer Josef Rinnöck. This strategy for houising allowed connection to the facade and surroundings, allthough structures like this was usually built outside the city limits. There are eleven units, 16-40 m² of living space, connected to one single shared corridor that access to 4 toilets. The avarage occupancy rate of 5 persons meant that 55 people was compelled to share 4 toilet facilities.

Bassenahaus (end 1800) A commonly used scheme for housing under the bourgeois free market approach to Vienna. The middleclass dwellings are located in relation to the street while the workers are located to the backyard. The common corridor is only providing secondary light to the apartments, while the centrally located courtyard (15% of the plot) is providing less than effecient daylight to the 5 units shared among workers. With an occupancy of 5 people - 25 tennants shared 3 bathrooms among them.

Karl Marx-Hof (1927-1930) 57m² is shared between 2-3 occupants, 4 units is distributed around the staircase. The toilet facilities has been moved inside the apartments while the common spaces are placed centrally in the plan. The apartments windows are now facing the street, and the greater couryard (83% of the plot) presenting another social class to the public life in Vienna.

Figure 2.17. Generic floor plan, Manufakturhaus

Figure 2.18. Floor plan, Rinnböckhof

Figure 2.19. Generic floor plan, Bassenahaus

Figure 2.20. Floor plan, Karl Marx-Hof

Karl Marx-Hof

29

Street Street Street Street Master dwelling Worker

Worker Worker Middle Class

Courtyard Courtyard Courtyard Common Common Common Wc Wc Wc Wc

Worker

Dwellings

Refurbishments

1950s

Reparation of the damage caused during the Austrian Civil War

€35 €30 €25 €20 €15 €10 €5

1986 - 1992

General restoration including the installation of new water pipes, lifts, windows, and doors

2010 - 2015

Refurbishment including roofs, terraces, loggias and surfaces

Figure 2.22. Figure 2.21. EU Waste Hierarchy (environment.ec.europa.eu, 2022)

Conservation measures

Refurbishment funding (in millions) (geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at, 2022)

Since its completion, Karl Marx-Hof has undergone a series of refurbishments, to restore original details and modernize the apartments according to today’s standards. The first refurbishment took place in the 1950s, during which the damage that was caused during the Austrian Civil War was repaired. Between 1989 and 1992, a general restoration was carried out, including the installation of new water pipes and lifts as well as energy efficient windows and doors. Smaller units were reconfigured into larger ones and the building complex was connected to the district heating system, providing the tenants with central heating. The refurbishment was conducted in

accordance with the Vienna Housing Promotion and Rehabilitation Act, which contains provisions for the subsidization of new housing and the rehabilitation of existing residential buildings and dwellings. The renovation costs amounted to 32,4 million euros, of which 29,2 million originated from municipal funding.

In 2010, Karl Marx-Hof underwent its latest refurbishment, including roofs, terraces, loggias, and surfaces. General maintenance and modernization work was carried out, including the implementation of a new waterwell system for the irrigation of the large green areas.

30 Mass Housing

1 2 3

Reduction Recycling Recovery Disposal

Self-financed Municipal subsidies

Prevention

Most preferred Least preferred

Vienna today

Amsterdam

46%

Vienna 45% 650 € Paris 20% 1750 € 30

apartment 10 30

Figure 2.23.

1961 40 50

Figure 2.24.

Share of housing stock (%) (Data from Wiener Wohnen, 2018)

Figure 2.25.

Rent comparison in Europe (Data from Wiener Wohnen, 2018)

Property ownership in Vienna

Municipal flat Condominium House ownership Other main rent Other 10% 1000 € 20 40

Tenants Flat owners House owners Sub-tenants and others

Standard of municipal dwellings

Category A - Min. 30m2 floor space, kitchen, toilet, bath room; heating system or fixed heating installation

Category B - Bed/living room, kitchen, toilet, bathroom

Category C - Running water and toilet inside flat

Category D - No running water and/or no toilet inside flat

1971 1981 1991 2001 2017

Evolution of living space in Vienna (m² per capita) (Data from Wiener Wohnen, 2018)

Vienna, the world’s best city?

Today, the City of Vienna excels in a variety of different fields. Most notably is probably the city’s high quality of life, as international surveys have suggested many times over. On closer inspection, it’s easy to see why the viennese model is so highly regarded. The city offers among the most affordable, accessible and stabile housing in Europe, with low rents, short waiting lists and long-term leases.

Today, subsidized rental apartments make up a quarter of Vienna’s total housing stock and are distributed according to a maximum income limit system similar to the one introduced a century ago.

Figure 2.26.

Vienna in figures (Data from Wiener Wohnen, 2018)

The Austrian capital has the world’s highest quality of life, Europe’s highest proportion of rental housing and is one of the least segregated capitals in Europe. It has also recieved numerous awards throughout the years, relating to topics such as liveability, sustainability and innovation. Many of these are attributable to the municipal social housing model that was introduced during the Red Vienna era. Despite the many new housing policies that have been implemented over the years, the key principles that were adopted during the First Republic still hold true: affordability, high quality, social cohesion and a good social mix.

31

Karl Marx-Hof

Share of rental housing Average rent 1100 € Zurich 29% 1450 € Munich Cooperative 20

Vienna Austria

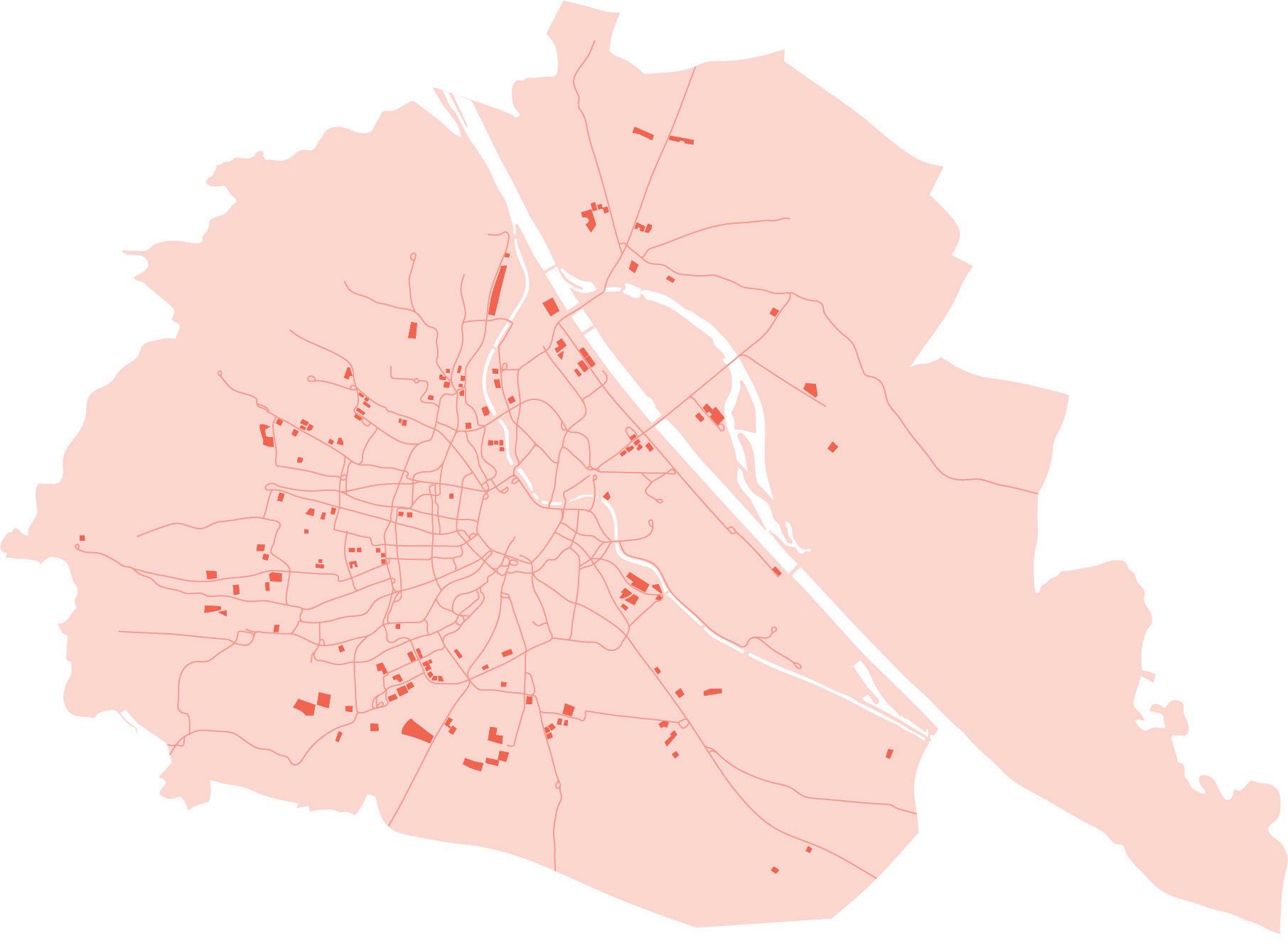

Vollsmose

Location: Vollsmose, Odense, Denmark Size: 255,353 m² (3,638 units), and 54,000 m² business Years of construction: 1966 - 1970, 1970 - 1974, 1978 - 1981, and 2020 - 2029 (proposed)

Case study by:

Isabella Fyfe Eszter Olah

Birkeparken Bøgeparken

Egeparken

Other buildings

Stage one: 1966 - 1970

Stage two: 1970 - 1974

Stage three: 1978 - 1981

Figure 3.1. The construction stages of Vollsmose (Diagram based on information from multiple sources)

The Vollsmose Plan

The Vollsmose Plan was proposed in 1964. The plan comprised nine housing areas bordered by four major roads within the ‘Vollsmose square’. Construction began in 1966 and finished in 1981, occurring in three stages (fig. 3.1.). The plan changed considerably in response to shifting societal ideals over time. The uniform appearance of stage one was criticized upon its completion in 1970, as was the idea of the ‘planned city’. Stage two was thus modified to include buildings of varying lengths, heights, and typologies. By the time construction began on stage three, ideals had changed so much that the buildings were built as terraced houses.

Demolition Partial demolition / renovation Preservation New boundary

Figure 3.2. 2019 statutory development plan proposed works (Diagram based on information from Civica, FAB and Odense Municipality, 2019)

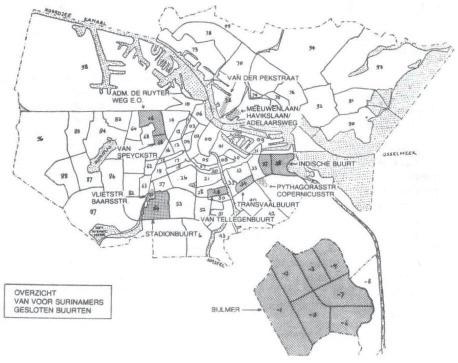

The Vollsmose of the Future

In 2018, the Danish Government released the One Denmark without Parallel Societies: No Ghettos in 2030 strategic plan. Additionally, Vollsmose’s boundary changed to exclude three of the nine housing areas. The six that remain were labeled ‘hard ghettos’. In 2019, the statutory Development Plan: The Vollsmose of the Future was released. The plan shows how the share of public family housing will be reduced to no more than 40 percent by 2030 to achieve the goal of the 2018 strategic plan. 1,000 public family homes will be demolished, those preserved will be renovated, and 1,600 new private family homes will be built by 2030 (fig. 3.2.).

34 Mass Housing

Planning

Granparken Lærkeparken Fyrreparken

Egeparken

Bøgeparken

Birkeparken

Hybenhaven Slåenhaven

Tjørnehaven Granparken Lærkeparken Fyrreparken

Egeparken

Bøgeparken

Birkeparken

Hybenhaven Slåenhaven Tjørnehaven

Granparken Lærkeparken Fyrreparken

Egeparken

Birkeparken Bøgeparken Granparken Lærkeparken Fyrreparken

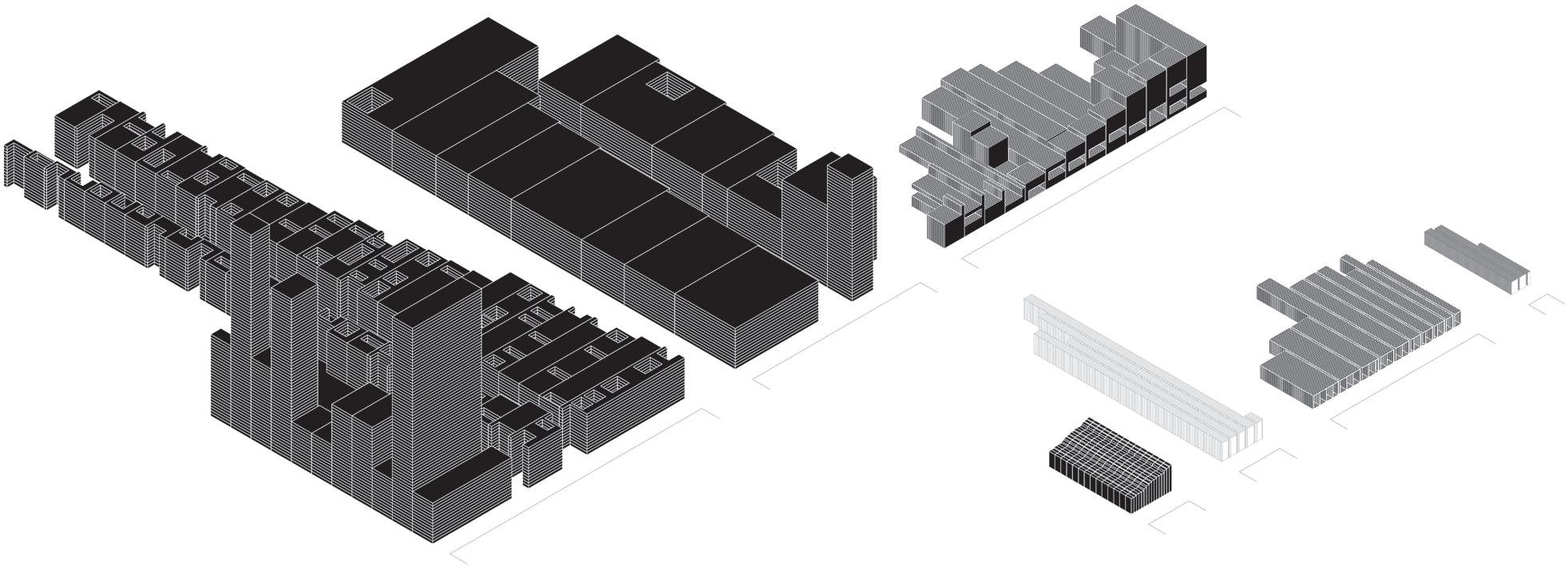

Construction

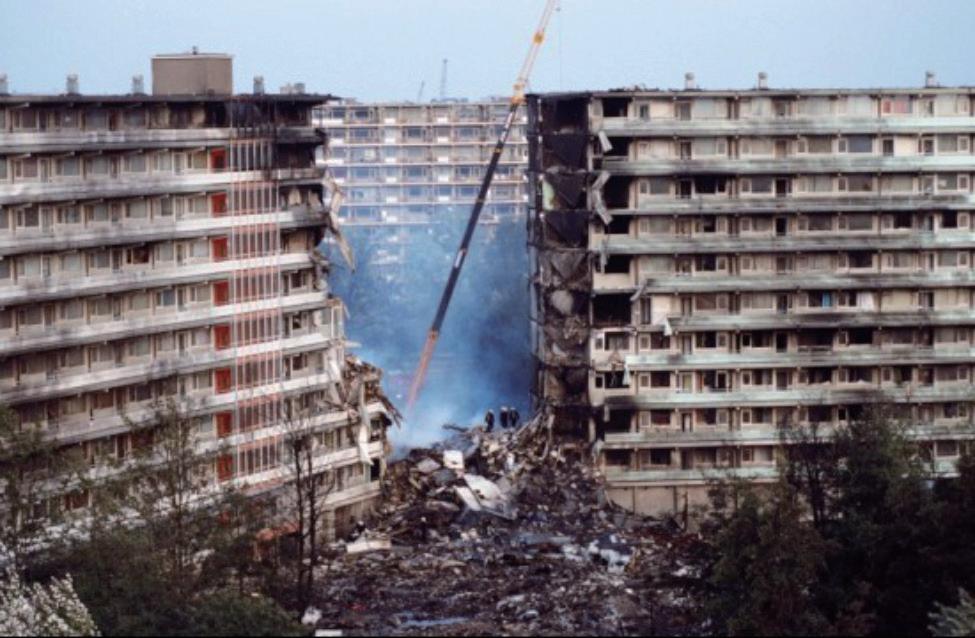

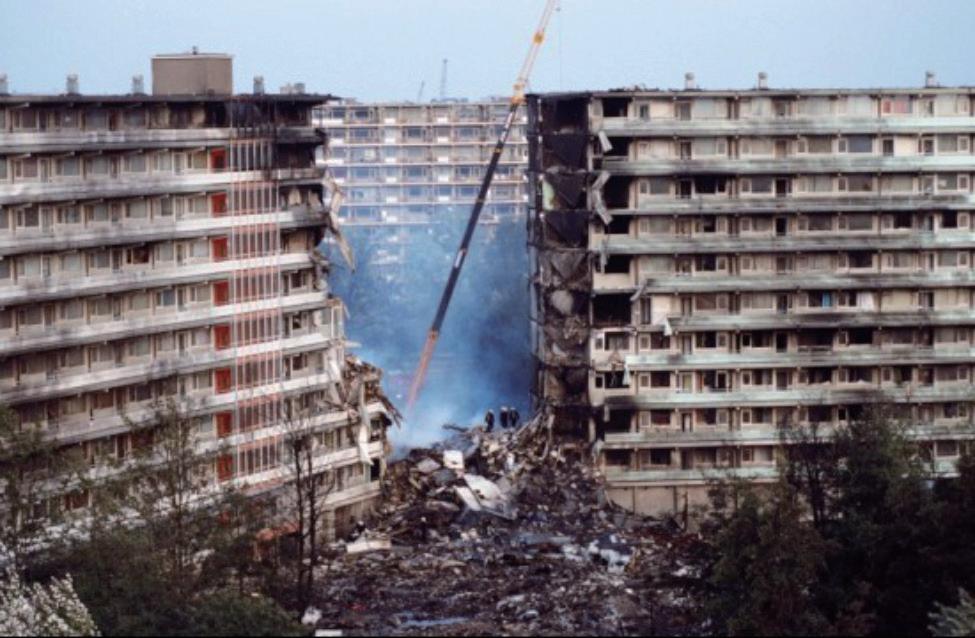

The construction of Vollsmose began in 1966. Buildings were erected using prefabricated concrete elements that were lifted into place by cranes and cast together on site (fig. 3.3.). This industrialized construction technique was typical for public housing in Denmark at the time, though, it was a relatively new and untried method. Between 1960 and 1980, the majority of Denmark’s public housing was built using this technique which was developed to quickly erect many buildings due to a lack of housing, resources, and skilled work force after WWII. The construction method allowed Denmark to successfully overcome it’s housing shortage in a short period of time. Many buildings in Denmark constructed using this method are still in use today.

16,000 0

As part of the 2019 statutory development plan, 35 percent of Vollmose’s existing residential building stock or 89 374 m2 will be demolished. Additionally, there will be 143 759 m2 of new construction. The majority of the demolition will comprise the prefabricated concrete high-rise residential structures. The concrete elements in these structures have a considerable embedded CO2 footprint. For example, almost 2 000 tonnes of CO2 eq. is embedded in Birkeparken block 65’s concrete elements alone. Birkeparken block 65 accounts for approximately one fifth of the total proposed demolition works in m2. Therefore, constructing The Vollsmose of the Future will have a substantial environmental impact in terms of carbon footprint.

n

c o n

n s

14,000 i

o n b e g

c

s m o s e c o n

o

35 Vollsmose

1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

2,000 P r e f a b r i c a t e d

4,000 s t r u c t i o

6,000 b e i n g s V

8,000 l

10,000 s t r u

12,000 t i

Figure 3.4. Number of newly built public houses in Denmark per year. The majority were built in a 20 year period between 1960 and 1980. (Graph based on information from Heunicke et al., 2021) 35% or 89 374 m2 demolition 56% or 143 759 m2 new build

Joint cast in place between wall elements

Joint cast in place between external vertical wall elements

Joint cast in place between inner wall element and deck

Figure 3.3. Prefabricated concrete construction method (Diagram based on information from Heunicke et al., 2021)

Figure 3.5. Proposed demolition and construction works (Pie charts based on information from Heunicke et al., 2021)

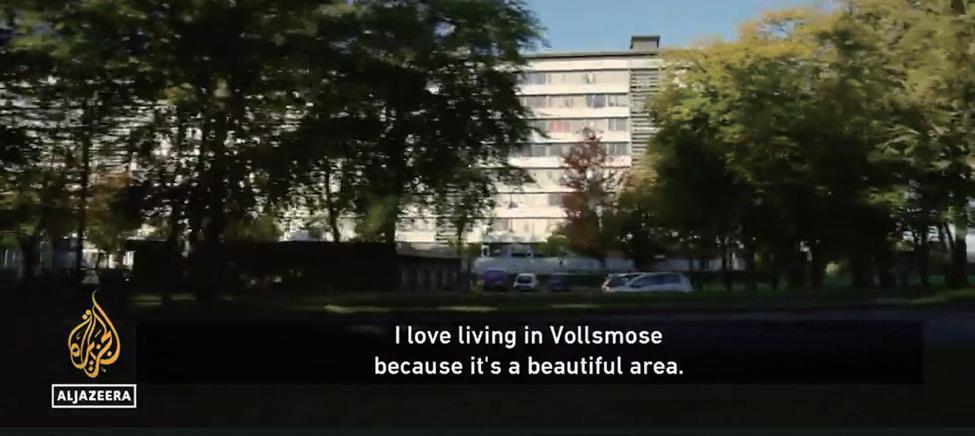

Life in Vollsmose

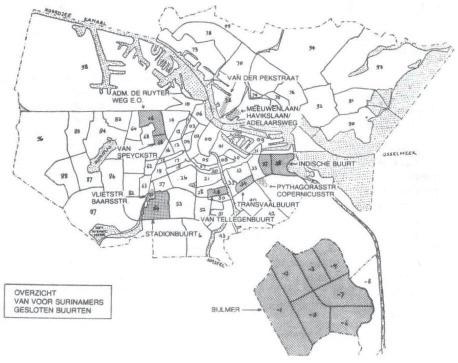

The first residents moved into Vollsmose in April, 1968. Since then, Vollsmose and to a greater extent Denmark have undergone significant changes across more than half a century. In 1972, Vollsmose experienced a rental crisis and a large portion of apartments became vacant. Rent was affordable for socially disadvantaged people thanks to housing subsidies and thousands began to move into Vollsmose. By the mid 1970s, several social issues had started to emerge and the high proportion of non-Western residents were seen as the causation. This mindset continues today in Vollsmose. Because of this, non-Western immigrants and descendants face discrimination based on race, ethnicity, national origin, and other protected grounds, says the UN.

1. Figure 3.6. New residents move into Vollsmose, March 1969 (Photo taken by Fyens Stiftstidende’s press photographers, 1969)

2. Figure 3.7. Excerpts from a documentary film about Vollsmose. Resident Ibrahim El-Hassan reflects on their life in Vollsmose and Danish Prime Minister Lars Lokke Rasmussen’s 2018 New Year’s speech. (Photo taken by Baker, 2019)

3. Figure 3.8. Children in Bøgeparken walk towards a billboard that reads ‘Do you have questions about the future of your home?’ (Photo taken by Ringkjøbing, 2022 2019)

4. Figure 3.9. Demolition works underway in Bøgeparken, 2022 (Photo taken by Wedell, 2022)

36 Mass Housing

2 1 4

3

Renovations

Figure 3.10. Between 1994 - 1995, half the units in Egeparken’s seven-storey block were converted from four- and one-bedroom units to two- and three- bedroom units. (Diagram based on information from Engberg, 2000)

1968 - 2006

Vollsmose underwent several renovations between 1968 and 2006. In the 1980s, renovations were conducted to fix extensive construction damages that resulted from the use of new building techniques and materials in the 1960s and 1970s. Other renovations attempted to tackle social issues that had started to emerge in the mid 1970s. For example, at Egeparken during 1994 and 1995 a major physical renovation was undertaken in an attempt to deter large ethnic families from living there by downsizing half the units (fig. 3.10.). In turn, it was hoped that the relative number of Danish residents in Egeparken would increase.

The objective of Egeparken’s renovations in the mid 1990s was not realised. Bosnian refugees moved to Vollsmose just after the renovations and many settled in Egeparken. This example typifies how physical renovation projects in the Danish social housing sector have tried and failed to address social issues in ‘problem’ housing estates. Today, radical and long-term physical and social changes, in addition to wider urban strategic solutions, are favoured in Denmark as the appropriate means eradicate these ‘ghetto’ residential areas. The Vollsmose of the Future is one example of this. The plan has sparked much debate between government policies, residents, and the social housing sector as to whether it is the ideal solution.

Plumbing upgrades

Electrical improvements

New kitchen, bath, and toilet Plastering and painting works

New patio, doors, and windows

Replacement of flooring and fixtures

Improving accessibility in some units Balcony extension and new glass protection

Upgrade of outdoor areas including landscaping

New ventilation system, refurbishment of heating

Post-insulation of facade and improvement of thermal bridges

Figure 3.11. List of proposed renovation works at Birkeparken (List based on information from FAB, January 2021)

2 000

Preparation works for the installation of washing machines, and dryers 1 099 DKK increase 1 000

Future monthly rent Current monthly rent

Figure 3.12. Birkeparken 2021/2022 current and future rent. The increase will help fund the statutory renovations. (Graph based on information from FAB, 2022)

2020 - 2029 (proposed)

A series of demolitions and renovations will occur from 2020 to 2029 to transform Vollsmose in line with the statutory development plan. Public housing associations Civica and FAB are responsible for these works. In Birkeparken alone, FAB will demolish 200 out of 439 homes and renovate those that remain between 2022 and 2025. These renovations (fig. 3.11.) will be done with a focus on achieving DGNB silver certification in sustainability. They will be financed through loans and grants again from The National Building Fund, the housing department’s ongoing savings for renovations and maintenance, and rent increases (fig. 3.12.).

37 Vollsmose

3 000 4 000 5 000 6 000 0 DKK

Granparken Granparken

Deconstruction

Birkeparken

Birkeparken 65 Vollsmose

Birkeparken

Birkeparken

Brick facade 22 m³

Birkeparken

Concrete facade 444 m³

Interior walls 346 m³

Concrete primary walls 1463 m³

Ton of CO2 2286 tonnes

Concrete floor slabs 3296 m³

ton C O 2 eq.æ k v 2286 ton

3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0

3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0

Ton of CO2 2286 tonnes 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0

Roof deck 533 m³

Steel 40m³

Concrete stairs 91m³

Lift 7pieces

Glass 44m³

Figure 3.13 Birkeparken Block material catalogue (Diagram based on Ressource Blokken, 2021)

The Resource Block is a joint research project between industry partners,housing association and research institutions. The project is working with two residential areas on the ghetto list and maps the existing resource stock, tests and documents the quality of the secondary materials in the buildings and investigates the potential to disassemble and reuse the secondary materials in new buildings. The aim is to develop scalable reuse solutions.

Ny produktion Birkeparken

Window frames 78m³

Ny produktion Birkeparken

Disassembly of the buildings will happen in steps: as in a traditional demolition the existing buildings will be stripped down to the structure, the structure is then cut with a diamond cutter into box modules and deck/wall elements that are lifted out with a crane. The advantage of demounting the building into larger modules and elements is that the monetary and environmental cost of cutting and crane lifting can be reduced.

The Danish Technological Institute tested the concrete for its composition, strength and potential pollution and found that the majority of the building elements are clean of toxic chemical compounds and can thus be reused. However, the concrete elements are only suitable for use in passive environments (i.e. non-loadbearing functions) as their composition and the strength do not live up to current standards.

Distribution of CO2 emission from the the recycling of concrete elements

Possible environmental savings by recycling concrete 1732 tonnes of CO2

Possible environmental savings by recycling concrete 1732 tonnes of CO2

Figure 3.15. Embedded CO2 in all concrete elements of buildings in Vollsmose (Diagram based on Ressource Blokken, 2021)

Beton gulvplader

Concrete floor slabs

Concrete primary walls

Distribution of CO2 emission from the the recycling of concrete elements

Interior walls

Concrete facade

The pie chart shows the amount of embedded CO2 for all concrete in the building, as well as the estimated CO2 impact during separation of the elements for the purpose of recycling. This constitutes 14% of the total CO2 and thus enables saving a total 1700 tonnes of CO2

Brick facade

Window frames

Glass

Concrete floor slabs

Proportion of CO2 from cutting elements Birkeparken New construction

Birkeparken

Interior walls

Concrete facade

Brick facade

Beton primære vægge Indvendige vægge Beton facade Mur facade Vinduesrammer Glas

Beton gulvplader

Concrete stairs Steel Roof deck Roof insulation Asphalt roofing Energy consumption for cutting Blades replacement

Betontrappe Stål Tagdæk Tagisolering Tagpap Energiforbrug til skæring Udskif tning af klinger

Birkeparken

3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0

Window frames

Concrete primary walls Glass

Beton primære vægge Indvendige vægge Beton facade Mur facade Vinduesrammer Glas

Concrete stairs Steel Roof deck Roof insulation Asphalt roofing Energy consumption for cutting Blades replacement

Proportion of CO2 from cutting elements Birkeparken New construction

Betontrappe Stål Tagdæk Tagisolering Tagpap

Energiforbrug til skæring Udskif tning af klinger

ton C O 2 eq.æ k v. 2286 ton

tonnes

Ny produktion

Figure 3.16. CO2 emmission in case of a new construction (Diagram based on Ressource Blokken, 2021)

An LCA has been carried out on the residential block Birkeparken 65. The calculation is representative, i.e. that it has been calculated what a similar building would have in terms of CO2 impact if it were to be built today.

38 Mass Housing Betont appe Ene giforbrug til skæring Udski tning af klinger

Birkeparken

Concrete Concrete Glass Window Brick Concrete Interior Birkeparken New construction 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 Ton of CO2 2286

3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 ton C O 2 eq.æ k v 2286 ton

Figure 3.14.

Demolition in Vollsmose (Photo taken by Hanne Kjær, 2022)

Reuse

Figure 3.17.

Circular urban regeneration (Diagram based on Ressource Blokken, 2021)

Based on the development plan for Vollsmose, six Danish architects:Effekt, Panum & Kappel, Spektrum, JaJa and 3XN were asked to participate in a design process and to come up with technical solutions for how to reuse the existing building stock to build new row houses in the area. As the concrete elements cannot be reused in load bearing functions the designers had to find other solutions to fulfil the loadbearing requirements e.g. using steel frames.

Figure 3.18.

Figure 3.19.

Figure 3.20. Figure 3.21. Figure 3.22.

Vollsmose regeneration project concepts (Ressource Blokken, 2021)

JAJA

When the block in Vollsmose is to be demolished, we suggest one separation arranged to reestablish a new residential quarter, built around a strong community on a human scale.

3XN

The project seeks to create a modular building system based on recycled concrete elements from Birkeparken.

Future buildings are designed so that their structural principles are prioritized according to the greatest need possible flexibility in layout and use, long lifetime and a rational construction process. Facades can for example appear in brick and wood. Brick is a long-lasting material that patinas beautifully and is already well known in Vollsmose’s context.

EFFEKT

A wooden building system, which is ‘designed for disassembly’, gives new life and new value to old prefabricated building components.

SPEKTRUM ARKITEKTER

The proposal challenges the traditional ‘betragtning af et hjem og’ comes with a bid on social housing enclaves with fluid and graduated boundaries between private and public spaces.

39 Vollsmose End of use phase Maintenance and flexibility Installation of elements in new construction Screening of construction - Should it be dismantled or simpky renovated? Environmental and resource mapping Inclusion of residents. - What can we do together? Preparation of tender materials with requirements for dismantling.

performs environmental remediation. Items are forwarded to the other user Processing with a view to recycling and upcycling Storage in warehouse Removal of elements Circular process local application Use phase Preparation for disassembly

Contractor

PANUM & KAPPEL

Montagerækkerne is an offer for a new housing development, created based on directly recycled elements and ma terials, resulting from the demolition of Blok 45 in Birkeparken.

Co-Housing

Concept of co-housing

Based on Danish experiences with bofællesskaber, the concept of ‘co-housing’ was introduced internationally in the late 1980s by McCamant and Durrett (1988). Key recurring values in definitions and practices of co-housing are community, autonomy (as in self-governance), affordability and, since the 1970s, ecology (as in resource-saving, ecological housing and lifestyle). Since the 2010s, these values have tended to be subsumed under the umbrella of ‘sustainability’ and its different dimensions – social, ecological and economic.

Employment and occupation, education, image and safety, cultural bridging and multicultural dynamic development, commitment, co-operation and local ownership (The Secretariat of Vollsmose 2003).

The belief is that by raising the standards of the area you can attract a better tax base and lessen the burden on the social services and thereby create a more mixed group of residents. The rationale of this strategy is that success in attracting more resourceful residents will endorse the area with more social and economic capital, which will raise the area as a whole.

Social and economic sustainability are prioritized in order to create more socially mixed neighbourhoods and attract citizens that will constitute a larger tax base.

Example of cohabitation

- small, close-to-low housing with common rooms - shared cultivation gardens, laundry, car sharing - young couples - duplexes - single parents - young people who share housing

Multigenerational homes - duplexes on multiple floors - small accessible homes - two storey family homes - families with children - grandparents/ seniors

Mixed housing cluster - common outdoor areas - apartments - townhouses - duplexes - single parents - singles

Figure 3.23.

Cohabitation (Diagram based on Bydelsplan for Fremtidens Vollsmose,Konkurrenceforslag, 2022)

The communitarian view of social capital prevalent in the Kvarterløft programme ties it to the nexus of ideas around the reinvention of community in urban policy, which is an international phenomenon of the 1990s. In the Danish case the community imaginary invokes the idea of the close-knit village community saturated with capabilities for communal action. The aim of the Kvarterløft programme is through topdown initiated bottom-up action foster the re-building of communities based on this imaginary.

Extra barriers for ethnic minorities are likewise the case in relation to the development of social capital. The increasingly popular concept of social capital in academic and policy arenas take in relation to the Kvarterløft programme the form of responsibility, ownership, and networks among residents which lead to increased capacity for action to improve the environment in, and reducing the problems of local neighbourhoods.

40 Mass Housing

gasmission

“There are parallel societies around the Danmark. Many people with the same problems are lumped together. It creates a negative curve. A counterculture. There where one does not take responsibility, does not use the possibilities we have in Denmark – but stands out. Holes have been made on the map of Denmark. Therefore, we must drop the illusion that parallel societies and ghettos will disappear if we just give them time. For example, Vollsmose, the powerlessness and isolation. ” (“Lars Løkke Rasmussens nytårstale 1. januar 2018”)

“Vollsmose’s edge must be broken. Today, the area is like an island in Odense, surrounded by four-lane roads and with border planting on all sides. The way to a new and stronger Vollsmose is to break with Vollsmose’s basic idea, plan, structure and create an open district in immediate connection with the rest of the city and the river valleys, with more businesses, educaion and services.”

The quote is from the latest publication in a long series of reports about the analysis of Vollsmose. 2Break Kanten- Open Vollsmose” is pulished by the Multifunktional Bydel, which was a project in he housing comprehensive plan 2008-2012, a collaboration between Odense Municipality and housing associations, Højstrup, OAB and FAB, the residents of Vollsmose and the Landsbyggefonden.

The case of Vollsmose is a complex package. It has to be examined from many different aspects. We have to take into account the social, economical, ecological, historical and political sides in order to get closer to the understanding of the evolution os Vollsmose.

The comprehensive regeneration plan of Vollsmose is targeting the improvement of housing conditions, social integration, aiming to provide job opportunities, puts emphasis on education, while taking into account the environmental impact.

On the other hand the project is somewhat bilateral. While we see the intention to a change towards the better, the question arises, is it what the residents want?

“We must set a new goal of completely tearing down the ghettos. In some places by tearing down the concrete, demolishing buildings, spreading out the inhabitants and rehousing them in different areas. In other places by taking a control of who moves in. We must close the holes in the map of Denmark and recreate the mixed neighbourhoods, where we meet each other across our differences” (“Lars Løkke Rasmussens nytårstale 1. januar 2018”)

41 Vollsmose

Fo u n d a t i o n G r eenh

Climate F

t io n L sso

retawdnuorG oPull t noi E

Ce i l i n g

dE u c a t ion Living

W o r k

Social

ouse

reshwater Consump

fo ytisrevedoiB noitatserofeD

c ological

emocnI

Condition

Vollsmose past - present - future

Vällingby

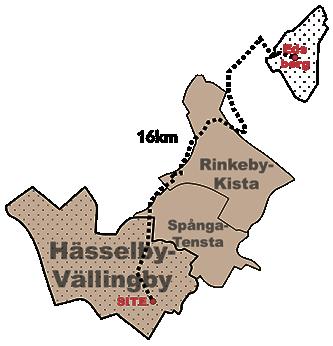

Historical context: the first ABC city in Sweden

Figure 4.1.: the historical events and background of the inauguration of Vällingby as the first ABC city in Sweden. It is important to note that the history of co-housing in Sweden dated back to the 1930s: the word ‘kollektivhus’ came into widespread use with the first modernist projects. Proposals to build large kollektivhus around 1930 were intended to solve two problems at the time: a shortage of housemaids, and the right of married middle-class women to work.

From Acceptera to ABC city

In Sweden, the relationship of modern architecture to the welfare state starts with their common ascendance around 1931-1932. Created by architects and city planners, the manifesto Acceptera mentioned the concept ‘family hotel’ and claimed that housing should embrace a functionalism orientation. With the architectural exploration into the future form of living, the model ABC city was accepted. ABC stands for work, dwelling and centre. In this model, the new town would be largely self-functioning units consisting of working, housing, and their commercial and cultural functions in the centre.

The neighborhood unit was a town planning idea of the 1940s intended to highlight the democratic importance of the ‘group society’, with certain collective facilities in the neighborhood. Since the Social Democrats achieved their first majority in the Stockholm municipal elections and formed their national government, over a long period of Social Democrats hegemony, housing policies were manifested as ‘social engineering’, associating urban planning and the design of dwellings with the paradigm of ‘the good life’ and ‘the just society’.

44 Mass Housing

Question: how do we build a new modern city for the new democratic society?

Figure 4.2.

Building types in 1950s Vällingby. (Illustration based on Svenska Bostäder, Vällingby)

1950s Vällingby

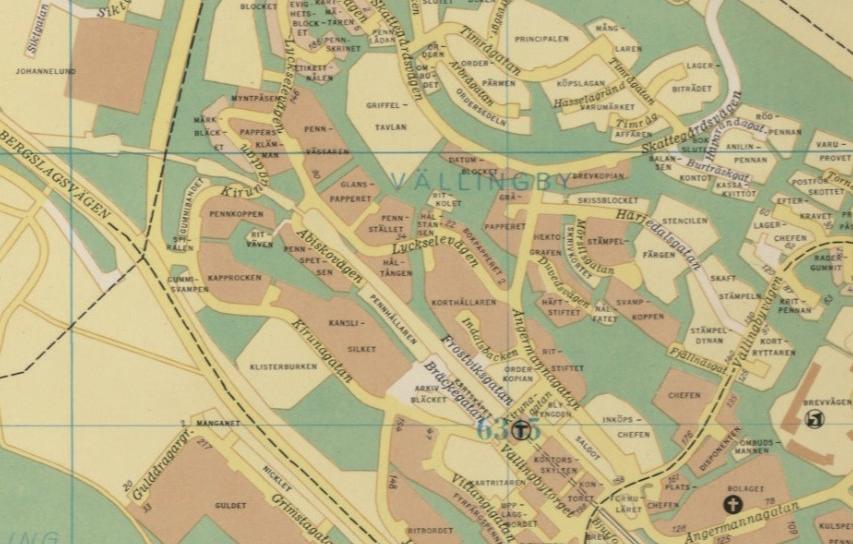

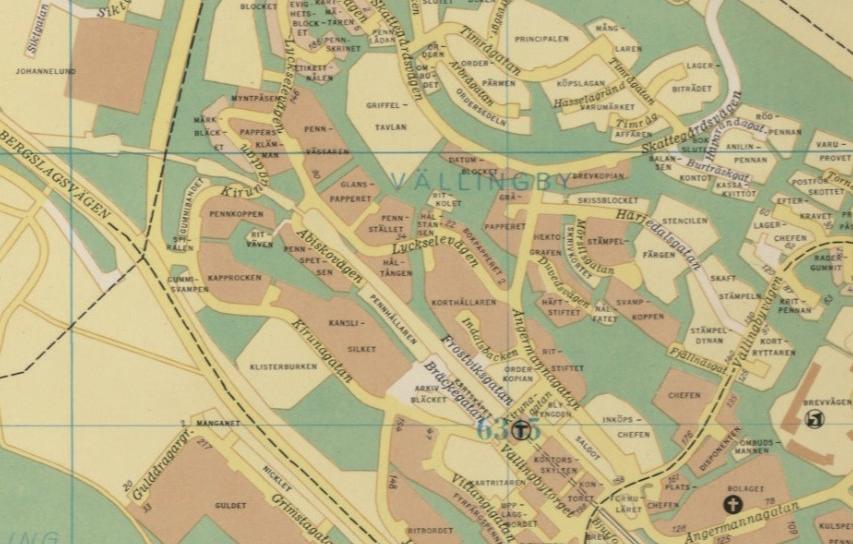

During 1950s, a large amount of residential buildings, industries, offices, shops and infrastructures were constructed in Vällingby along with the new subway line (Fig. 4.2). Engaged by architects Paul Hedqvist, Ragnar Uppman etc. and construction companies SB(Svenska Böstader), HSB(Hyresgästernas Sparkasse), SKB(Stockholms Kooperativa Bostadsförening) etc.

According to the 1954 general plan led by Sven Markelius, Vällingby centre and offices were built surrounded by multiple types of housing units for different group of people.

Figure 4.3.

Case 1 - Silvret 2

Statistis systems of Silvret 2 (Illustration based on Ingemar Nyquist, “Elementbyggda flerfamiljshus - 9 metoder”)

Year of completion: 1958

Construction Cost: 640 SEK/ m²

Ownership: SB → Condominium Association (2020)

Frame system: Bifurcating inner walls load-bearing Lifting device: Tower slewing crane

Factory Location: Edsberg (16 km from site)

The limitation of housing production due to a lack of labour are the context for Silvret 2. To reduce the need for labor on site, a new prefabricated method of construction was used. The construction time dropped to 60 percent compared to traditionally built houses.

Figure 4.4.

Case 2 - Atlantis

Type: row house

Overview of Atlantis (Illustration based on Stockholm stad, “Construction matters of Atlantis“)

Ownership: condominium association

Living area: 3 886 m2, 29 terrace houses

Inhabitants: family with at least two children

Year of completion: 1954

Architects: Jon Höjer, Sture Ljungqvist, Fritz Ridderstolpe, Hasse Hansson

Construction cost: ca. 571 SEK/per house unit

Rent in 1956: 1300 SEK/m2

Before the project began, those who were interested were required to invest 5 percent of the estimated production cost.

45

Vällingby Construction

Load-Bearing Walls

cenrtrum industriområde småhus allmänt ändamal fler familjshus

Living in Vällingby

Greenspace map in Vällingby (data from dataportalen.stockholm.se)

Greenspace map in Vällingby (data from dataportalen.stockholm.se)

Figure 4.5.: social changes in Vällingby

Skog Urban gronstruktur av oppen karaktar

Skog Urban gronstruktur av oppen karaktar

Greenspace map in Vällingby (data from dataportalen.stockholm.se)

Figure 4.6.

Urban gronstruktur av naturtomtskaraktar

Urban gronstruktur av naturtomtskaraktar

Skog Urban gronstruktur av oppen karaktar

Urban gronstruktur av lummig karaktar

Urban gronstruktur av tradkaraktar

Urban gronstruktur av tradkaraktar Urban gronstruktur av lummig karaktar

Urban gronstruktur av tradkaraktar Urban gronstruktur av lummig karaktar Urban gronstruktur av naturtomtskaraktar

Oppen till halvop pen grasmark oppen vatternyta Buskmark

Oppen till halvop pen grasmark oppen vatternyta Buskmark

Oppen till halvop pen grasmark oppen vatternyta Buskmark

Oppen hallmark Odlingslott eller frukttradgard

Oppen hallmark Odlingslott eller frukttradgard

Oppen hallmark Odlingslott eller frukttradgard

Green space map in Vällingby today. (Illustration based on Stockholms stad, "Dataportalen")

Figure 4.7.: green space map in 1954 Vällingby. The distribution of greenery has remained intact. The abundance of nature is an asset for the district and refines living experience. (Stockholms stad, "Compare Maps")

70 years in Vällingby

Since 1952 when people moved into Välllingby gradually, the new town witnessed its heydays as well as slow decay (Fig. 4.5). The first decade was the most prominent era when families arrived with their young children. Then problems arose with teenage boom, and increasing crime rates. People moved out for multiple reasons: the long commutes from Vällingby to their working places, old city centre continuing to attract people with the history and diversity, buildings and infrastructure becoming dilapidated, the segregation between north and south Vällingby, and the increase of housing price with the process of privatization.

46 Mass Housing

Case1 - Silvret 2

The Silvret 2 includes 119 apartments with total area of 8,020 m². Apartments were wider than usual, 12 meters, resulted in large living space. The floor plan is strongly typified, which brings flexibility in apartment size (Fig. 4.8). In the 1960s, Grimsta began to have several social and youth problems. One cause of the problems was considered to be the too many small apartments. The one-room apartments with a kitchenette, which were initially intended for pensioners, often went to socially deprived people. Thanks to the efforts of community workers, the trend turned in the mid1970s.

Case 2 - Atlantis

The Atlantis neighborhood includes 29 terrace houses and common buildings such us laundry room, garage, storage, sauna, and exercise room. Though there are several different types of housing, the basic layout is the same: made up of three halflevels, kitchen open to a large family space for social need and adaptivity, which an advanced approach for the time (Fig. 4.10).

As a ‘bostadsrättsförening’ housing, Atlantis has developed a different form of living and ownership. A distinctive feature of Atlantis is the united community and the engagement of its members, which contributes a lot to the sustainability and vitality of Atlantis.

Figure 4.8.

Plans (Illustration based on Ingemar Nyquist, “Elementbyggda flerfamiljshus - 9 metoder,” )

Figure 4.10.

Entry floor plan (Illustration based on Hemnet, “Lövängersgatan 23”)

Figure 4.9.

Figure 4.11.

Second floor plan (Illustration based on Hemnet, “Lövängersgatan 23”)

47 Vällingby

interior space of apartment in Silvret (Svenska Bostäder, “a Picture Story of Silvret 2")

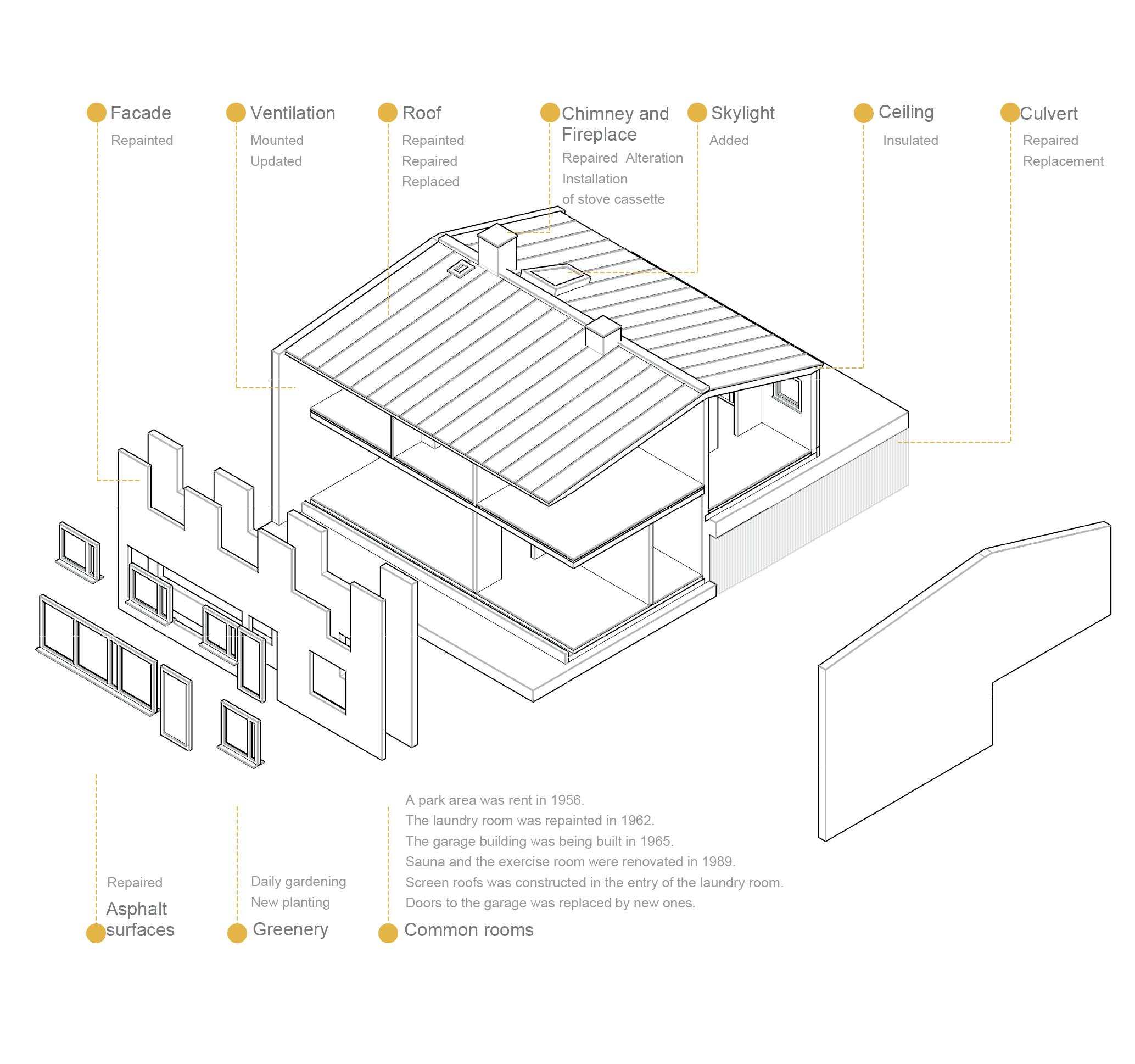

Roof material change (from asbestos to tin) in 1997 Renovated in 2006 2032

Bathroom change in 2006

25 years 6 years

20 years

Facade Cladding Renovation in 1983, 2008, 2022

Glazing of Balcony in 1986, 2017

Wood Panel Add in 2009 Repaint in 2028

OVK Control in 2019 2025 Case 1 - Silvret 2

Svenska Bostäder depreciation plans: LAND PLANT: FRAMES: CEILINGS: FACADE AND BALCONIES: WINDOWS AND FRONT DOORS: BATHROOMS: ELECTRICITY: PIPES: VENTILATION: LIFTS/ ESCALATORS:

100 years

30 years Figure 4.12. Maintenance detail of Silvret 2 (Illustration based on Ombildningskonsulten, “Ekonomisk Plan för Bostadsrättsföreninggen Silvret 2”)

Maintainence cost in next 10 years (2020 - 2030)

40 years 40 years 40 years 50 years 50 years 50 years

ROOF: FACADE: BALCONIES: LAUNDRY ROOM: HEAT FACILITIES: SEWAGE/WATER: VENTILATION: OVK CONTROL: ELECTRICITY: TOTAL: ESTIMATED FEE RAISED:

500 000 SEK

50 years 20 years 30 years

20 years 55 000 SEK 100 000 SEK 900 000 SEK 400 000 SEK 2 550 000 SEK 250 000 SEK 300 000 SEK 2 200 000 SEK 7255 000 SEK 9 SEK/ m² and year

48 Mass Housing

Maintenance

Figure 4.13.

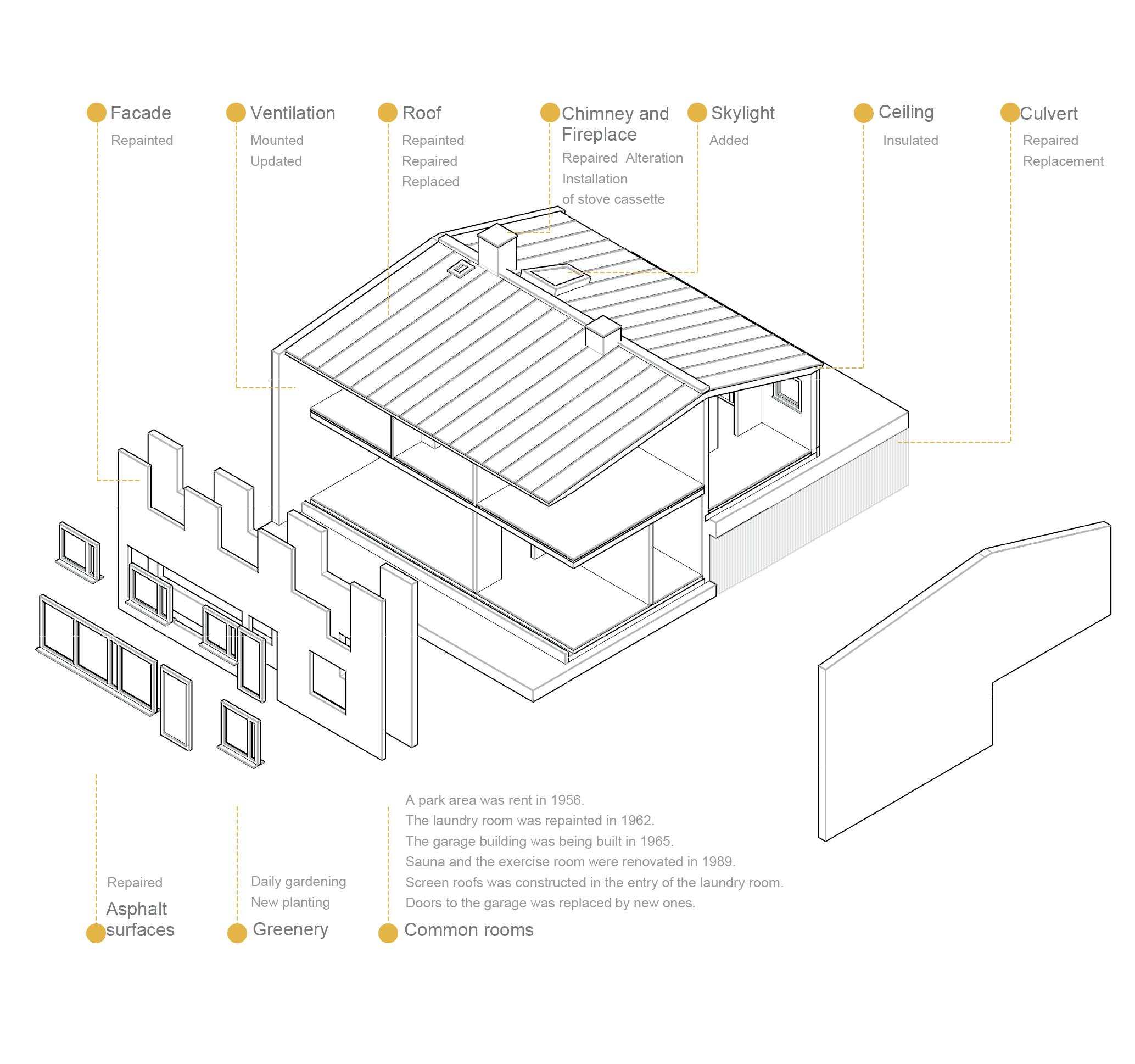

Case2 - Atlantis: life cycle of building elements

Maintenance detail of Atlantis (Illustration based on Stockholms stad, “Construction Matters of Atlantis”)

-ROOF: -DOWN PIPES: 25 years 25 years Painted in 1957

Leakage in 1985 and repaired in approx. 1987 Replacement in 2011

Hot-water pipes insulated in 1979 Repaired in 1985

Replacement of cold-water pipes in 1993 Renovation of water and sewage systems: 2021 -CEILING: Insulated with new false ceilings in 1975 Insulated with horizontal ceilings in 1992

-HEATING SYSTEM:

20 years 15 years

Added a new boiler to the joint heating system in 1969; Proposal of installing a heat pump system in 1984; Updated to the central heating system in 1987; Reconstruction of heating plant in 1989; Added a new central boiler in 1992.

*ENERGY:

Energy saving measurements to reduce the oil consumption in 1979.

An energy investigation in 1983. An energy inspection in 1992. The energy declaration was completed in 2007.

49 Vällingby

Situation today

Figure 4.14.: energy consumption of residential buildings in Välllingby (classified by kWh/m2 per year). Most of housing built in 1950s has a relatively high consumption of electricity. (Illustration based on Boverket)

Ecological Sustainability

Today in Sweden, the energy performance requirements of new buildings are strict. However, when Vällingby was constructed, the carbon footprint of buildings did not draw so much attention. To compensate the high consumption of energy (Fig. 4.14.), several measurements were adopted, for example improving envelope’s insulation. Today, some old buildings have an excellent energy class because of the adoption of thermal mass energy supply system, which offers clean and renewable energy. New housing buildings, such as the Vällingby Allé, were built with the potential to install solar cells on roofs.

Social sustainability

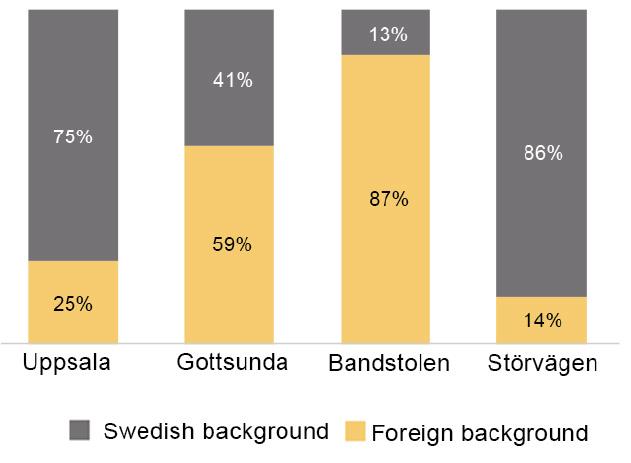

An obvious segregation of income exists between the north and south Vällingby (Fig. 4.15), which are the rowhouse neighborhood and the apartments respectively.

Figure 4.15.: average income (in SEK) of residents in Vällingby, together with the location of municiple services and public spaces. (Illustration based on Hitta)

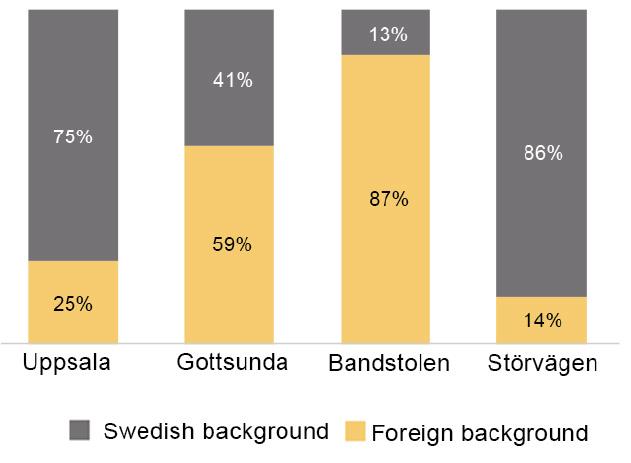

The average data of the whole area compared with that of Stockholm shows that inhabitants in Vällingby have lower income, lower education, higher unemployment, and less health. Additionally, Vällingby also has a relatively higher percentage of residents with foreign backgrounds, 45.9 percent (Fig. 4.17.), which means today the ABC city is an arrival city for new comers to Sweden.

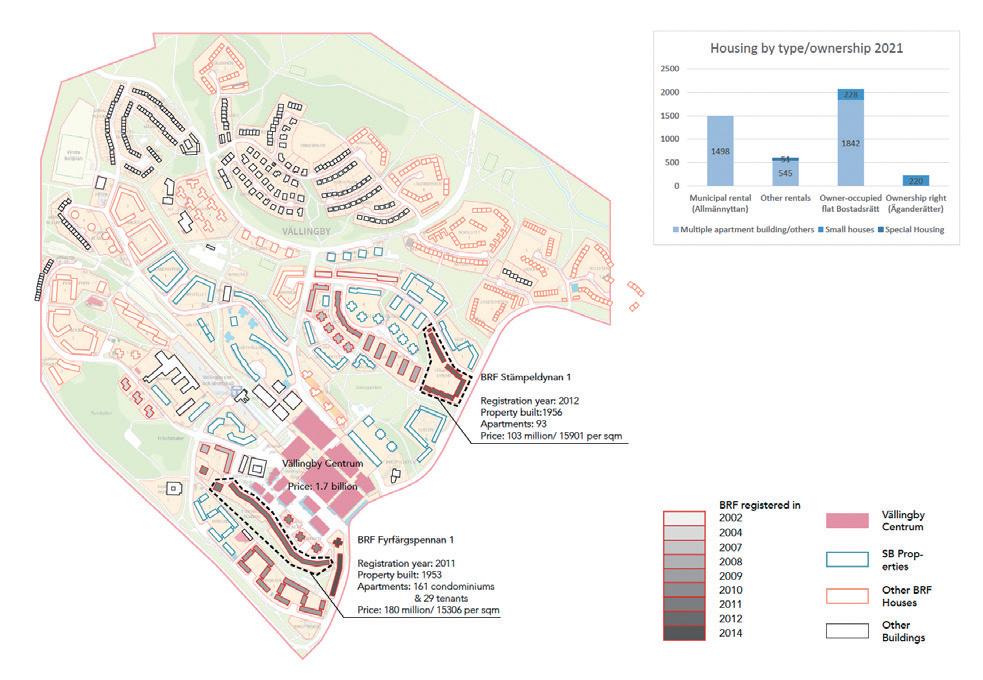

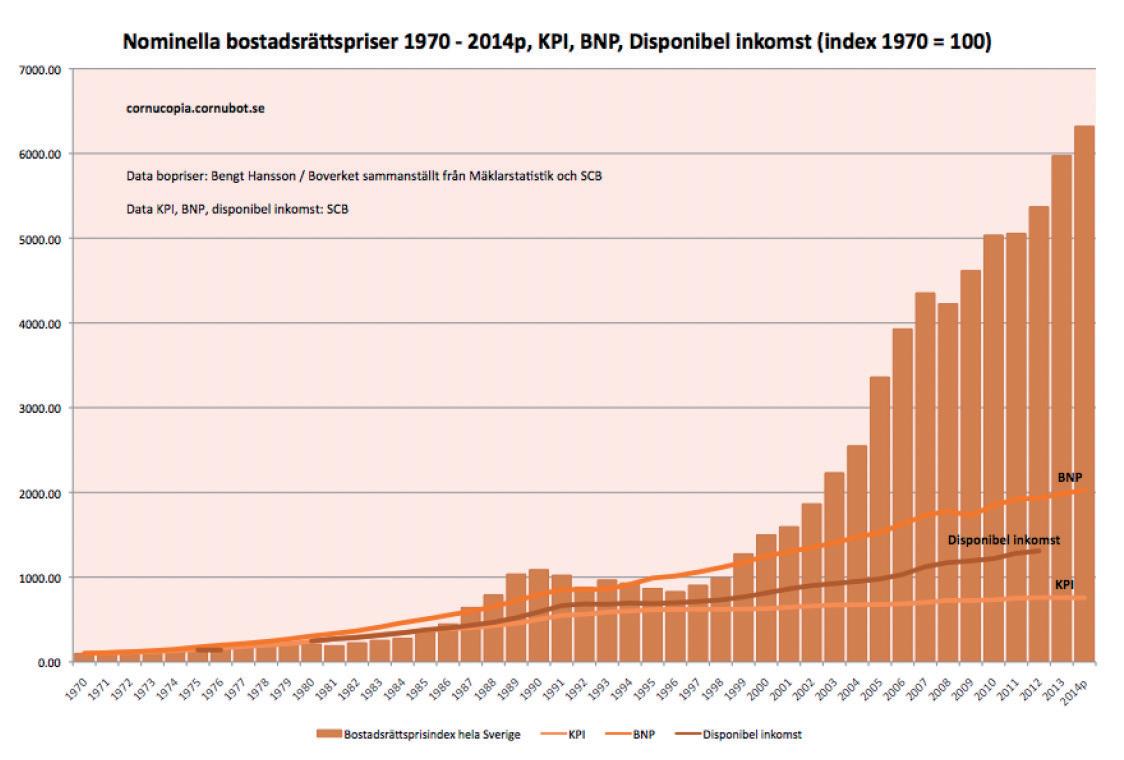

Economic sustainability

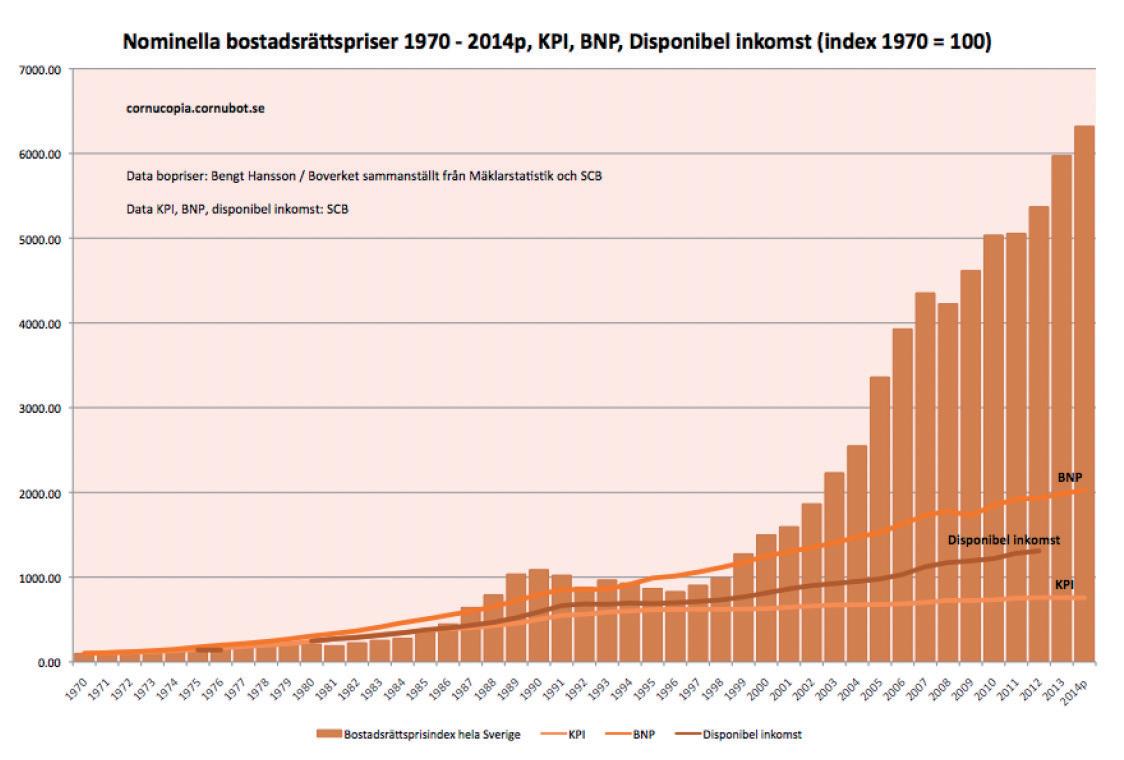

Dating back to 1990s or earlier, neo-liberalism began to influence Swedish politics and society. In 1992, the government formally allowed local decisionmaking concerning conversion of public rental housing into market forms (cooperative housing). The municipal housing companies were selling their properties in Vällingby to private real estate companies. The housing price was soaring while income was growing unstably (Fig. 4.18.).

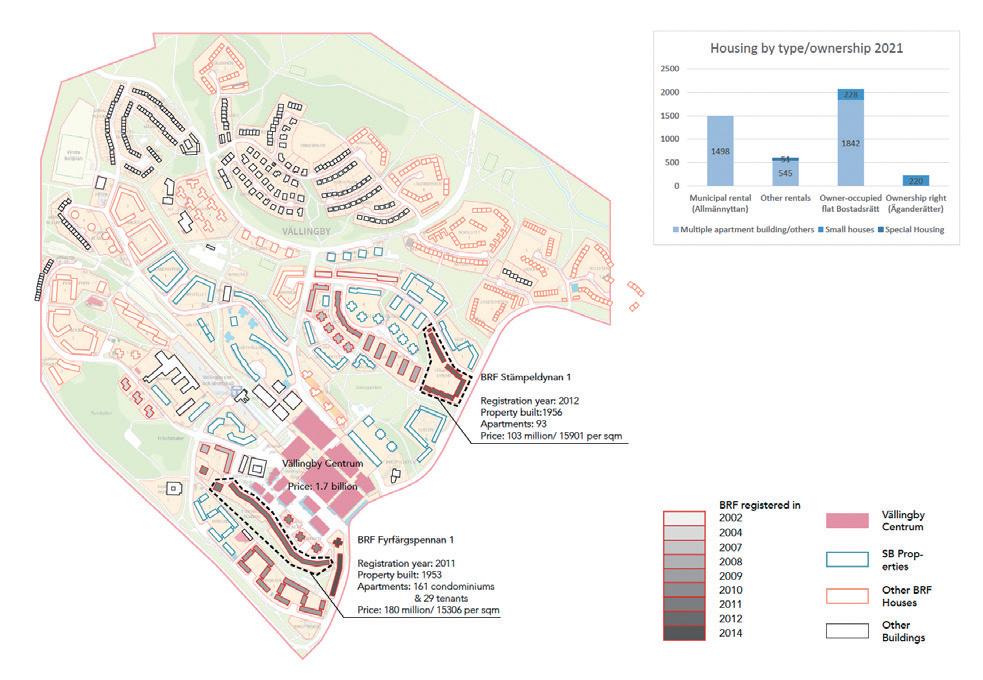

Figure 4.16.: ownership map of housing buildings in Vällingby; ownership composition in various types of housing. (Illustration based on Stockholms Stad, “Områdesfakta Vällingby Stadsdel”)

At the same time, housing built in 1950s was aging and renovations became necessary. This expenditure becomes another burden on the financial situation of the local inhabitants.

50 Mass Housing

Energy Declaration of Housing building in Vällingby in unit of kWh/m² och år (data from www.boverket.se)

<60 60-85 85-110 110-135 >210 135-160 160-185 185-210

<60 60-85 85-110 110-135 >210 135-160 160-185 185-210 <60 60-85 85-110 110-135 >210 135-160 160-185 185-210

Figure 4.17.: population with foreign background in Vällingby compared with the percentage in Stockholm. (Illustration based on Stockholms stad, “Facts of Sub-urban Area ” )

Spånga Station

Figure 4.18. housing price change compared with income. (Cornucopia, “Bostadsrättspriser 1970 – 2014”)

Beckomberga

Figure 4.19.

Future plan

Hässelby Stand

- Urban development within the existing street layout.

- Vällingby centre continues to be reinforced as a centre for several districts, which will involve adding houses, workplaces, and town centre functions in a way that reinforces the value inherent in its status as a heritage environment of national interest.

- Improved public transport links are required.

Centre Key meeting point Metro station

Nature/culture reserve Urban corridor Strategic connection rail or road devel opment agreed or in progress

Strategy of Vällingby development (Illustration based on Stockholms stad, “Stockholm City Plan”)

- Improve the safety and accessibility of the park corridor between Hässelby Gård and Ormängstorget.

- Create an attractive recreation area with better links between Nälsta and Vällingby.

- Strengthen the connection across Vinsta to Hässelby Gård.

- Develop serviced and business surrounding Råcksta metro station.

51 Vällingby

Hässelby Gård

Gottsunda

Location: Uppsala, Sweden

Size: 5 000 units

Year of construction: started at 1960s

Case study by:

Robbin Modigh

Feng Tinghao Zhang Yuchao

Historical question

Population problems

The development of residential areas in Gottsunda began in the 1960s with the Million Housing Programme, which aimed to provide affordable, high-quality housing to all Swedish citizens. Uppsala faced rapid population growth at the time, as did the rest of Sweden. Until 1963, Uppsala’s population growth rate was maintained at around one percent per year, but after 1963, it increased rapidly to over two percent.

Therefore, in order to solve the housing problem caused by the population growth, the Uppsala municipality approved in the planning proposal for South Valsätra in 1966, with a plan to build more

than 3,000 new collective housing units and 490 detached houses. In 1970, the municipality planned an additional 5,000 housing units in North Gottsunda, in which several distinctive features of the Million Housing Programme were reflected, including a central, enclosed residential area, underground passageways connecting to external areas.