NEWS FROM THE AUCTION AND GOLD MARKET

Dear Customers, Dear Coin Enthusiasts,

We have just concluded the first part of our autumn auctions with a record result: Auctions 410-414 brought some of the highest-grossing auction weeks in the company’s history. We are very pleased with your interest, and especially about the well-filled auction hall – finally we can meet many of you in person again, and our auctions will once more become a numismatic meeting place where like-minded people can exchange ideas and talk shop.

Now the second part of our autumn auctions is just around the corner, and from 28 to 31 October 2024 we will offer you sensational numismatic-, and this time also phaleristic highlights.

We want to draw particular attention to lot number 2166 of Auction 416, which contains the coin collection of Clementine of Orléans as part of the estate of Dr Alexander Eugen Herzog of Württemberg. It is a classic 19th-century coin collection in which the historical significance of the coins was valued more highly than their preservation. That is why there are many different qualities in this lot of 306 coins. You can read more about the impressive woman who was the original collector on pages 18-20 of this issue.

Coins from the ancient world will be auctioned in Auction 416 on 29 and 30 October 2024. Dr Eike Druckrey’s collection includes 305 Greek coins, which will be presented under the title “The Aesthetics and Conceptual World of the Early Greeks”. It is a tangible result of his shared enthusiasm with the ancient Greeks for all things beautiful. During the many years in which he built up his collection, Dr Druckrey tried to bring together the most fascinating Greek coins in the most

beautiful condition. More information about the collector and his collection can be found on pages 9-11.

Still more highlights from the ancient world will come under our virtual hammer on 31 October beginning at 2:00 pm as part of our eLive Premium Auction 417. Part 9 of the Dr W. R. collection will be auctioned off, containing coins from the time of the Roman civil war which followed the death of Nero to that of the Severan dynasty.

We are proud to be able to offer orders, decorations, coins and medals from the estates of ducal houses in Auction 415 on 28 October 2024. It contains 631 lots, which will come under the hammer of our auctioneers in cooperation with Philipp Württemberg Art Advisory GmbH. You can look forward to very special numismatic and phaleristic rarities that once belonged to persons who made history, including some from the estates of Dr Alexander Eugen Herzog of Württemberg and Carl Theodor of Bavaria. Our orders expert Michael Autengruber has described some of these interesting objects in more detail on pages 14 and 15.

As part of our series on numismatic museums around the world, on pages 16 and 17 we travel with Dr Ursula Kampmann to Zagreb, where she visited the Archaeological Museum -- and was very impressed by the rapid reconstruction of the museum after a devastating earthquake in 2020.

In our previous issue, you were able to follow the gradual discovery of ivory and elephants by the ancient Greeks in the first part of the article “Elefantenmünzen” by Prof. Johannes Nollé. Now we present the second part of the piece on pages 21-23.

We hope you enjoy perusing the latest issue!

Ulrich Künker Dr. Andreas Kaiser

Prof. Johannes Nollé.

Orders, Decorations and Medals from the Possession of the Wittelsbachs at our Auction 415

On 28 October 2024, Künker will hold its auction of orders and decorations, presenting objects of utmost historical value. The offer includes, for example, items from the estates of Alexander Eugen of Württemberg and Carl Theodor in Bavaria, the younger brother of Empress Sisi. You will not only find phaleristic rarities, but also outstanding medals and coins from their possessions.

Künker’s upcoming auction of orders and decorations, which will be held in collaboration with Philipp Württemberg Art Advisory GmbH on 28 October 2024, contains a total of 631 lots. The sale goes beyond the scope of orders and decorations to also include many medals and even coins from the estates of Dr. Alexander Eugen Duke of Württemberg and Carl Theodor in Bavaria. You can look forward to very special numismatic and phaleristic rarities from the possessions of people who made history!

The Estate of Carl Theodor,

Duke

in Bavaria (1839-1909)

There are historical figures whose life’s work still fills us with awe today. One of them is Carl Theodor Duke in Bavaria, son of Max in Bavaria, and younger brother of the Austrian Empress “Sisi”. He was a pioneer in Bavarian ophthalmology. After a life crisis, Carl Theodor decided to give up his military career to become a professional ophthalmologist. At that time, ophthalmology was making tremendous progress. With comparatively little effort, a good ophthalmologist could save a person’s sight, thus preventing them from becoming a helpless cripple. After all, a life of begging was the only option for destitute blind people in the 19th century.

Together with his second wife, Maria José of Braganza, who assisted him as a surgical nurse, Carl Theodor worked at the district hospital in Tegernsee, ran an outpatient clinic in Meran for a time, and founded an eye clinic in Munich at his own expense, which still exists today.

As head of the House of Wittelsbach in Bavaria (not to be confused with the Wittelsbach dynasty of Bavaria), he witnessed many historical events himself and inherited the family memorabilia of his ancestors. His estate, which will be offered in Künker’s auction 415, is of the utmost importance to Bavarian history.

Coin collectors in particular will be thrilled to see these iconic coins with verified provenance from the Wittelsbach estate. Among them are the histroy taler “Blessing of Heaven” (Segen des Himmels) from the possession of Max Joseph Duke in Bavaria, and a 3-mark commemorative coin “Golden Wedding Anniversary” (Goldene Hochzeit) from the estate of Carl Theodor’s widow.

Lot 285: Bavaria. Award medal for medical achievements on the occasion of the 70 th birthday of Carl Theodor in Bavaria on 9 August 1909. 14-ducat gold medal by Alois Börsch. Only two specimens struck. From the estate of Maria José, Carl Theodor’s wife. About FDC.

Estimate: 5,000 euros

On the occasion of the 70th birthday of Duke Carl Theodor on 9 August 1909, his wife Maria José funded this award in gold and silver. In February 1910, one gold and two silver medals were struck. Later in the year, another gold and two silver medals were produced, as well as one silver specimen for the Bavarian State Collection in Munich.

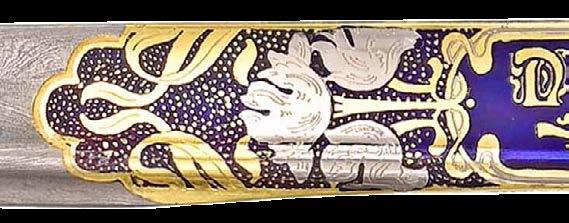

Lot 325: Honorary Sabre of the 3rd Royal Bavarian Chevau-légers on the occasion of Carl Theodor in Bavaria’s golden jubilee of military service on 11 October 1903. Unique.

Estimate: 10,000 euros

Even after retiring from his active military career, Carl Theodor remained an officer in the cavalry reserve. This meant that, despite his resignation from active service, he took part in the combat operations during the FrancoPrussian War of 1870/1. The 3rd Royal Bavarian Chevau-légers, the regiment he commanded, presented him with the honorary sabre on the occasion of his golden jubilee of military service in 1903. Carl Theodor had joined the military at the age of 14 on 11 October 1853.

Lot 322: Personal purse of Elector Carl Theodor of Bavaria (1724-1799).

Lot 317: German Empire. 3 marks 1918 D commemorating the golden wedding anniversary of the Bavarian royal couple.

From the estate of Maria José, Carl Theodor’s wife. Very rare. Extremely fine to FDC.

Estimate: 20,000 euros

Due to the shortage of silver caused by the war, only 130 pieces of the “Golden Wedding Anniversary” commemorative coin were minted, and King Ludwig III of Bavaria distributed a large portion of them as gifts. This is probably how this piece came into Maria José’s possession. The coin is one of the most sought-after commemorative coins of the German Empire.

Lot 355: Order of the Golden Fleece from the estate of Carl Theodor in Bavaria. II-.

Estimate: 10,000 euros

Shortly before his 20th birthday, Carl Theodor in Bavaria was initiated into the Order of the Golden Fleece as the 968th knight by his brother-in-law, Emperor Franz Joseph.

Lot 361: Gift box containing two gold medals of 35 ducats each, on the occasion of the wedding of Emperor Franz Joseph I and Elisabeth in Bavaria on 24 April 1854. From the estate of Max Joseph Duke in Bavaria, father of the bride. Extremely rare. About FDC.

Estimate: 40,000 euros

In the 19th century, it was customary to present guests at important festivities with commemorative medals whose weight and material directly reflected their rank and degree of kinship. Künker is pleased to be able to offer two gift boxes from the estate of Duke Carl Theodor in Bavaria, each containing two medals that were distributed as gifts on the occasion of the wedding of Emperor Franz Joseph I and Elisabeth in Bavaria on 24 April 1854. The gift box with the two gold medals was presented to Duke Max in Bavaria, the father of the bride. The gift box with the two silver medals was given to the bride’s younger brother, Duke Carl Theodor.

The Estate of Dr. Alexander Eugen Duke of Württemberg (1933-2024)

Alexander Eugen Duke of Württemberg was the fourth child of Albrecht Eugen of Württemberg and his wife Nadejda, daughter of Ferdinand I Tsar of Bulgaria. Alexander Eugen was a trained archivist and had studied art history, archaeology and auxiliary sciences of history. He worked for the Christie’s auction house, at the Bavarian State Office for Monument Protection, at the Bavarian National Museum and in the Bavarian Administration of State-Owned Palaces, Gardens and Lakes. He died childless on 18 February 2024. His death marked the end of the male line of the third Silesian branch of the House of Württemberg.

Künker offers historically significant numismatic and phaleristic objects from his estate, as well as some rare books on phaleristics from his specialist library. The material comes from the German Empire and from Bulgaria, the homeland of his mother.

Lot 192: Württemberg. Royal Great Order of the Golden Eagle. Jewel of the order.

From the Alexander Eugen Duke of Württemberg Collection. Extremely rare. II.

Estimate: 5,000 euros

Los 184: Saxony. Order of Maria Anna. 1st class cross in original presentation case.

From the Alexander Eugen Duke of Württemberg Collection. Extremely rare. I.

Estimate: 5,000 euros

Lot 252: Vatican. Pius XI. Medal for the 300-year anniversary of the foundation of the Sacred Congregation “Propaganda Fide”, 1922. Very rare. Proof. Estimate: 5,000 euros

This was a personal gift from Pope Pius XI to Tsar Ferdinand of Bulgaria, as is proven by a card. The Pope himself wrote on it in German: Mit herzlichstem Apostolischem Segen Pius PP. XI. (With the warmest apostolic blessing, Pius PP. XI. XI.) The somewhat damaged cardboard box reads A.S.M. Ferdinando Re dei Bulgari.

The sincerity of Pope Pius XI’s blessing is particularly noteworthy given that Prince Ferdinand had been excommunicated by Pope Leo XIII in 1896. The pope had punished Ferdinand for having his son and heir to the throne baptized Orthodox for political reasons. At an unknown later date, his excommunication was lifted by another pope.

Long Service Ribbon Buckles of the German States

The auction will also feature an impressive collection of long-service decorations in the form of ribbon buckles from the German States. Nothing comparable has been seen on the market for decades. The consignor acquired the collection decades ago from the “medal veteran” Jürgen Bielitz, decorations dealer and collector. Several pieces were added to the collection and its catalog is likely to become a new reference work.

Lot 4: Anhalt-Dessau. 1st class military service decoration for XX years of service as Non-commissioned officer (Unteroffizier) and in the enlisted ranks (Mannschaft). This specimen is depicted in Nimmergut, NDA 14. Very rare. I-II.

Estimate: 800 euros

Orders and Decorations from Various Estates

Impressive estates and special collections should not conceal the fact that Künker’s auction 415 also offers a wealth of rare orders and decorations from Germany and all over the world from various possessions. To give you an idea, we present a few rarities.

Lot 442: Palatinate. Order of the Palatine Lion. Cross of the knights of the order. Extremely rare. II.

Estimate: 10,000 euros

Estimate: 15,000 euros

Lot 443: Prussia. “Pour le Mérite” order. Order cross. Rare. I-II. Estimate: 10,000 euros

Lot 394: Hesse. Electoral Hessian Wilhelm Order (Wilhelms-Orden). 1st class Commander set. 2 specimens. Very rare. II. Estimate: 10,000 euros

512:

of

Brest star of the Grand

II. Estimate: 5,000 euros

Lot

France. Legion

Honor.

Aigle.

Lot 97: Saxe-Altenburg. Decoration for veterans with the years 1813/1815. Very rare. II. Estimate: 1,000 euros

Lot 478: Saxony. Royal Military Order of St. Henry (Saxony). Jewel of the grand cross, 4th model. Very rare. II.

Ancient Greek Coins from the Druckrey Collection at Künkerin our Auction 416

Our Auction 416 presents exquisite coins from the ancient world. Highlights are the Druckrey Collection of Greek coins, a Brutus aureus, as well as the collection of Clémentine d’Orléans, daughter of Citizen King Louis Philippe and mother of Tsar Ferdinand I of Bulgaria.

On 29 and 30 October 2024, the Künker auction house will hold auction 416. It contains 1038 lots with select Greek, Celtic, Roman and Byzantine coins as well as issues from the Migration Period and the Islamic world. We present a few highlights.

The Dr Eike Druckrey Collection

“The Aesthetics and the World of Thought of the Early Greeks” – this is the title of and the idea behind Dr. Eike Druckrey’s collection of 305 exquisite Greek coins. He was not interested in accumulating as large a collection as possible, but rather in selecting the most beautiful works of art from the Greek Archaic and Classical periods that related to Hellenic ideas and concepts. This collection will open auction 416 on 29 October.

Lot 1044: Kamarina / Sicily. Didrachm, 415-405.

From Sotheby’s auction L09447 (1999), 10. Very fine +.

Estimate: 7,500 euros

Lot 1015: Poseidonia / Lucania. Stater, 530-500. From the Charles Gillet Collection, Bank Leu auction 77 (2000), 51. Very fine +.

Estimate: 7,500 euros

Lot 1222: Magnesia / Ionia. Themistocles, + 459 BC. Trihemiobol, 464-459.

Connoisseurs will be delighted to see all their favorites: Poseidonia, Kaulonia, Kamarina, Naxos, Syracuse, Abdera, Athens, Corinth... In short – anything that true lovers of Greek coinage dream of can be found in this collection. The beauty of these issues speaks for themselves. And they are a testament to Dr. Eike Druckrey’s keen eye for detail in selecting these pieces.

Further information on the collection and the collector can be found on pages 9-11 of this issue.

Invitation to reception

On the occasion of our spring auctions 415 to 416, we

you

a

by

“Beautiful horses on Greek coins from the collection of Dr Eike Druckrey” Tuesday, 29 October 2024, at 7 pm (after the end of the auction) in the auction room

Lot 1295: Ptolemy II, 285-246 / Egypt. AE obol, 264-263, unknown Sicilian mint.

From Roma Numismatics XVII (2019), No. 443. Very rare. Very fine +. Estimate: 1,500 euros

From Nomos auction 2 (2010), No. 150. Very rare. Extremely fine +. Estimate: 3,000 euros

A Celtic Rarity of the Highest Historical Importance

After the Druckrey Collection, ancient rarities from various possessions will be presented. You can look forward to a beautiful series of Celtic gold coins, including a hemistater of the Caletes, who gave their name to Pays de Caux in Normandy, and an impressive gold stater of the Eburones of the highest historical importance. After all, the motif of this coin is associated with an episode of the Gallic Wars. Modern historians believe this depiction to be a means of propaganda for a Celtic uprising against the Roman troops. In fact, the Eburones resisted Roman conquest. Led by their king Ambiorix, they attacked a Roman winter camp in mid-November 54 BC.

The 15 cohorts stationed there left in a hurry and were completely annihilated. Around 10,000 legionaries are said to have died, equating to about a fifth of the troops stationed in Gaul. Caesar took his revenge in 53 and 51 BC. He massacred all the Eburones he could find, burned their farms and drove off their cattle. There is archaeological evidence of this. After Caesar’s punitive campaign, the Eburones no longer existed.

Greek Coins from Various Possessions

Connoisseurs will also find numerous rarities in the section of Greek coins from various possessions, including an extremely rare 100-litrae piece from Syracuse, signed by Kimon, with a provenance dating back to 1917. Of exceptional beauty is a posthumous gold stater of the Philip II type, whose Apollo head reminds of the portrait of Alexander the Great. A wonderful drachm of Pherae is from the BCD Collection. Thanks to its immaculate condition, the elaborate depiction really comes into its own. And the same holds true regarding an archaic didrachm from Erythrae.

Lot 1503: Celts. Eburones. Stater, middle of the 1th century BC. Extremely rare. Possibly the finest specimen of this type. Extremely fine. Estimate: 12,500 euros

Lot 1561: Syracuse / Sicily. 100 litrae, 405-400. Obv. signed by Kimon. From the collection of a North German friend of ancient coins. From the R. Jameson Collection. Very rare. Extremely fine. Estimate: 50,000 euros

Lot 1598: Philip II of Macedon. Gold stater, posthumous, 323-317, Colophon. Extremely fine +. Estimate: 25,000 euros

Lot 1623: Pherae / Thessaly. Drachm, 460-440. From Hess auction 253 (1983), No. 165 and the BCD Collection. Very rare. Extremely fine.

Estimate: 12,500 euros

Lot 1070: Syracuse / Sicily. 100 litrae, 405-400. Obv. signed by Euainetos. From the Virgil Brand Collection, purchased in 1915 from Jacob Hirsch. Extremely fine.

Estimate: 10,000 euros

cordially invite

to

lecture

Prof. Johannes Nollé.

Lot 1651: Erythrae / Ionia. Didrachm, before 480 BC. Rare. Extremely fine.

Estimate: 15,000 euros

Aurei of Brutus and Pompeius

Künker is pleased to be able to offer a Brutus aureus, which was purchased from Spink & Son in London on 12 September 1969. The coin dates from 42 BC and is one of the issues used to finance the military campaign of Caesar’s assassins. The gold came from contributions of communities in Asia Minor. This aureus was probably struck before the meeting of Brutus and Cassius in Smyrna in early 42 BC, when they discussed how to proceed. The very attractive specimen of about extremely fine quality is estimated at 100,000 euros.

75,000 euros is the estimate of an aureus struck shortly afterwards, showing the portrait of Sextus Pompeius on the obverse, and the heads of his father and brother on the reverse. The coin was minted in 37/6 BC to finance the construction of the fleet.

Lot 1809: M. Iunius Brutus. Aureus, 42 BC, mint in Asia Minor (Smyrna?).

Purchased on 12 September 1969 at Spink & Son, London. Very rare. About extremely fine.

Estimate: 100,000 euros

Roman and Byzantine Rarities

Of course, these two aurei are not the only Roman rarities in this auction sale. Künker’s auction 416 features everything a collector’s heart desires: rare aurei, fine bronze coins, denarii with excellent portraits, and some interesting provincial issues – there is truly something for everyone.

From

Estimate:

Lot 1822: Sextus Pompeius. Aureus, 37/6 BC, Sicilian mint. Very rare. Very fine.

Estimate: 75,000 euros

Lot 2077: Uranius Antoninus, 253-254. Tetradrachm, Emesa.

From Leu auction 10 (1974), No. 349. Very rare. About extremely fine / Extremely fine.

Estimate: 7,500 euros

Lot

Estimate: 50,000 euros

Lot 2078: Postumus, 260-268. Aureus, 258/60, Cologne. From Jacob Hirsch auction XIV

Estimate: 25,000 euros

2108: Crispus. Solidus, 319/20, Trier.

From Leo Biaggi de Blasys auction, No. 2058. Very rare. Traces of reworking at the edge. About extremely fine.

Lot 1970: Aelius. Aureus, 137.

MMAG auction 17 (1957), Lot 462. Rare. Extremely fine / About extremely fine.

40,000 euros

(1905), Lot 1407. Very rare. Extremely fine.

Lot 2193: Artavasdus, 742-744 with Nicephorus. Solidus. Extremely rare. Very fine.

Estimate: 20,000 euros

Lot 2036: Diadumenianus. Quinarius, 217-218. From Triton XX (2017), No. 805. Very fine +. Estimate: 25,000 euros

Lot 2106: Constantine I (306-337). Solidus, 313-315, Trier.

From Hess-Leu auction 49 (1971), No. 456. Extremely fine.

Estimate: 35,000 euros

Lot 2200: Alexander, 912-193. Solidus. Very rare. Very fine. Estimate: 20,000 euros

Lot 1704: Judaea. Shekel, year 3 (= 68/69), Jerusalem. From the Samel Collection, Künker auction 334 (2020), No. 2264. Extremely fine. Estimate: 10,000 euros

Lot 1706: Judaea. Tetradrachm, 133/4. From the Samel Collection, Künker auction 334 (2020), No. 2404. Extremely fine. Estimate: 10,000 euros

Lot 1834: Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra. Tetradrachm, ca. 36 BC, unknown mint. Very rare. Very fine +. Estimate: 40,000 euros

Roma Universa:

The Clémentine d’Orléans Collection

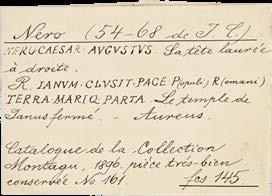

The coin collection of Clémentine d’Orléans was entrusted to Künker for auction as part of the estate of Dr. Alexander Eugen Duke of Württemberg, the rest of which will be sold in auction 415. This is a typical collection of the 19th century, with its collector attaching more importance to the historical significance of a coin than to its condition. As a result, this multiple lot of 306 coins contains pieces of many different qualities.

Clémentine d’Orléans was the daughter of Citizen King Louis Philippe and received an excellent education. Clémentine owed her love of history to her father, who personally taught this subject to her and her siblings. Clémentine also inherited her unique business acumen from her father, with which she managed the inheritance of her husband, Duke August Ludwig Viktor of Saxe-Coburg-Koháry. It was a vast estate of more than 150,000 hectares in Lower Austria, Hungary and present-day Slovakia. As a wealthy member of the high nobility, Clémentine systematically pursued the goal of elevating her sons’ ranks: She secured the position of Tsar of Bulgaria for Ferdinand I in return for considerable investment in Bulgarian infrastructure.

Part 9 of the

Dr

Clémentine traveled all her life. When she became too old to do so, she began to collect coins. A preliminary comparison of the handwriting on the coin slips and letters written in her own hand suggests that Clémentine identified her coins herself. She was particularly interested in Byzantine coinage, and owned the reference work of the time, Sabatier’s catalog.

Clémentine’s coin collection is a numismatic ensemble whose significance goes far beyond the coins themselves. It is a great stroke of luck that this collection has survived intact. Künker has therefore decided to keep it this way and offer it as an ensemble.

Further information on the collection can be found on pages 18-20 of this issue.

W. R. Collection in our eLive Premium auction 417

Our Auction 417, taking place on 31 October 2024 as an eLive Premium Auction, is dedicated to the general collection Roma Universa. It is part 9 of the Dr. W.R. Collection and covers the period from the era following Nero’s death up to the end of the Severan dynasty.

Part 9 of the Dr. W.R. Collection will be offered by Künker as eLive Premium Auction 417 on 31 October 2024. The 682 lots cover the period from the time after Nero’s death to the end of the Severan dynasty. As always, the Dr. W.R. Collection unites all fields of Roman numismatics. The collector was interested in gold, silver and bronze coins, in issues from the mint in Rome but also in local coins produced in the various municipal centers of the provinces. In doing so, Dr. W.R. always paid utmost attention to the quality of his pieces. But their historical background was also an important factor. Therefore, this collection contains numerous coins with interesting reverse depictions. The estimates of the individual lots range from the low 2-digit to the mid 4-digit segment.

We present a little selection of particularly interesting pieces.

Los 3011: Otho, 69. Antiochia / Syria. Tetradrachm, year 1 (= 69). Very rare. Very fine +. Estimate: 2,000 euros

Los 3015: Vitellius, 69. Sestertius. Rare. Very fine. Estimate: 5,000 euros

Los 3037: Diva Domitilla. Denarius, 82/3. Very rare. Very fine +.

Estimate: 1,500 euros

Los 3051: Bone token, 80. Probably unique. Very fine. Estimate: 500 euros

Los 3052: Julia Titi.

Denarius, 80/1. Rare. Extremely fine. Estimate: 600 euros

Los 3061: Domitian, 81-96. Aureus, 81. Very rare. Extremely fine. Estimate: 5,000 euros

Los 3180: Hadrian. Denarius, 130-133. Extremely fine +.

Estimate: 400 euros

Los 3083: Domitian, 81-96. Caesarea Maritima / Judaea. As, 92. Rare. Extremely fine. Estimate: 750 euros

Los 3293: Marcus Aurelius, 161-180. Ephesus / Ionia. As, 161-165. Very rare. Extremely fine. Estimate: 1,000 euros

Los 3103: Nerva, 96-98. Aureus, 97. Rare. About extremely fine. Estimate: 6,000 euros

Los 3324: Faustina II. Aureus. Rare. Extremely fine. Estimate: 6,000 euros

Los 3161: Plotina. Denarius, 112-114. Very fine.

Estimate: 1,000 euros

Los 3349: Lucius Verus, 161-169. Aureus, 161/2. Extremely fine +.

Estimate: 7,500 euros

2,000

The academic Crantor of Soloi (c. 335-275 BC) is mainly known for his commentary on Plato’s Timaeus. In this commentary, he makes it clear, among other things, that Plato considers the cosmos to be eternal and not created at a certain time. This view shared by the academics had been attacked by certain sophists since late antiquity. Proklos Diadochos defended Plato’s view, and by extension Crator’s, in De Aeternitate Mundi with 18 arguments.

In our eLive Auction 84 from 4-8 November 2024:

The Borstel Treasure trove

“A coin trove has been found in Borstel”, said the finder, commenting on the events in June 1992 in the district of Diepholz. While using a rotary tiller to plant crops on a plot of land behind his home, he and a colleague had come across some coins and potsherds. The origin of the coins was determined by subsequent searches and digging on a 50-metre-long piece of arable land: a clay pot buried in the ground, with numerous silver coins of various sizes and some gold coins.

The hoard, which has become known as the Borstel Treasure, contains a total of 937 coins, including 16 gold guilders (14 Rhenish guilders and 2 guilders from the Bishopric of Utrecht), 92 groschen coins ( mainly grotens of the Oldenburg counts,

in particular Gerhard the Quarrelsome, but also of the counts Nicholas and Dietrich the Fortunate), as well as 818 silver schwars (mainly Bremen coinages of the second type with key shield). The hoard also contains coins from the counties of Diepholz and Hoya, the city of Stade and the Bishopric of Verden, as well as some hollow pennies. The hoard was handed over to the Landesmuseum Hannover and then to a Hamburg coin expert for cleaning, processing, and scholarly evaluation.

The hoard consists mostly of coins that cannot be dated with any certainty, as none of them bears an inscription with a date. The date of the hoard’s concealment, however, can be determined from the few datable pieces – four white pfennigs of Johann von Hoya as the administrator of the cathedral chapter in Münster – and was thereby set in the period between 1460 and 1470. A temporal connection with the Battle of Borstel Heath in 1462 is possible, but cannot be proven. However, the types of coins can be seen as typical for the Bremen area at that time, especially the frequent occurrence of Bremen “Schwaren” and Oldenburg “Groten”. It is reasonable to assume that these were the hidden savings of a farmer from the Borstel region.

The complete Borstel Treasure trove will be auctioned in our next eLive Auction 84 from 4 - 8 November 2024 in around 100 lots.

Los 3555: Diva Julia Domna. Denarius, 218, minted under Elagabal. Very rare. Very fine +.

Estimate: 750 euros

Los 3606: Caracalla, 198-217. Soli-Pompeiopolis / Cilicia. As. Very rare. Very fine.

Estimate:

euros

Los 3648: Plautilla. Akrasos / Lydia. As. Probably unique. Very fine +.

Estimate: 1,000 euros

Los 3450: Manlia Scantilla. Denarius, 193. Very rare. Very fine. Estimate: 1,250 euros

Los 3499: Septimius Severus, 193-211. Attuda / Caria. As. Probably unique. Extremely fine. Estimate: 3,000 euros

Los 3553: Julia Domna. Emesa / Syria. Tetradrachm, 215. Very rare. Extremely fine +.

Estimate: 1,000 euros

The newly discovered coin treasure with parts of the clay pot in which it was buried.

Archdiocese of Cologne, Dietrich II of Moers, 1414 - 1463. Gold guilder, no date (1432), Bonn. Very fine. Estimate: 350 euros.

County of Oldenburg, Nicholas, 1401 - 1447. Groten, no date. Extremely rare. Very fine to extremely fine.

Estimate: 600 euros.

County of Hoya, Erich, 1377-1427.

Bracteate, Hoya. Very rare. Almost extremely fine. Estimate: 500 euros.

The Beauty on Coins, and the Beauty of Coins –

The Dr. Eike Druckrey Collection

Even the Greek language itself reveals the importance of beauty in the life of the Greeks. It has an extensive repertoire of words that denote beauty or individual aspects of it: kállos/kallónē (beauty), kósmos (adornment), lamprótēs (splendor), harmonía (harmony, evenness), euandría (beauty of men, of masculinity), euteknía (beauty of well-behaved children), eunomía (beauty of the state due to good constitution), euámpelos (beauty of vines), euántheia (beauty of flowers), euboos (beauty of cattle), eúhippos (beauty of horses), eúhydros (beauty of abundant water), eúkarpos (beauty of fruits) and so on. The utmost goal was kalós kagathós, a state of beauty and goodness.

Few peoples were as enamored of beauty as the Greeks – no matter what endeavor they undertook, their quest for beauty always played a central role. As a result, it is impossible to fully grasp the essence of this people without understanding, empathizing with, and ultimately sharing the Greek’s enthusiasm for beauty. Coin collector Dr. Eike Druckrey (fig. 1), who spent decades of his life trying to understand the quintessence of the Greek people and the aesthetics associated with it, has mastered this particularly challenging task. The Dr. Druckrey Collection is a tangible result of his enthusiasm for beauty, which he shared with the Greeks. Over the many years of building up his collection, he tried to bring together the most beautiful Greek coins in beautiful, if not the most beautiful, condition. In this way, his collection is a numismatic realization of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s saying: “Among all peoples, the Greeks have dreamt life’s dream most beautifully” (Goethe, Maxims and Reflections, published in German by M. Becker, Weimar 1907, 56 No. 298). By making the pieces he assembled with great effort and passion available to other collectors in auction 416, he enables them to add the splendor and beauty of the most exquisite Greek coins to their collections.

When it came to reaching this goal, the Greeks, on the one hand, had an eye for natural beauty, i.e., the beauty of their surroundings – such as the beauty of a landscape (especially mountains, rivers, springs but also the climate), of a person, an animal or a plant – and on the other hand, they strove to create beauty themselves. And especially their most important creation, the city, was meant to be beautiful. Since the late 8th century BC, Greek cities were designed and laid out according to a grid pattern with right-angled streets. The aim of Greek urban planning was that both the external, i.e. the structural appearance of a city, and the urban constitution as well as the culture of the people who lived in it to be beautiful. In the ideal city, citizens should exude beauty both through their education and their appearance.

It is therefore no surprise that the coins of the cities of Classical Greece were meant to use beautiful motifs to illustrate the advantages and especially the beauty of the city that commissioned them. In her dissertation “The Power of Beauty” (Die Macht der Schönheit, Bonn, Habelt publishing house, 2003), my Ph.D. student Dr. Isabelle Maupai analyzed and presented the pursuit of beauty in Greek cities during the imperial period. Most of the criteria for beauty of this period had been around for a long time, are thus traditional and therefore also apply to the periods from which the pieces in Dr. Druckrey’s collection originate, i.e., the Archaic, Classical and Early Hellenistic periods. It is impossible to deal with the various areas and aspects of the Greek quest for beauty within the limited space of this article. Therefore, it will focus on how cities presented themselves by depicting beautiful women.

The Greek word for city, pólis, is feminine, which is how the idea came up to represent a city through the image of a woman. It was clear to the Greeks that the representative of their city had to be beautiful. These beautiful women could be the city’s patron goddess, a spring nymph that provided water for the city, its founder, or its personification (the city’s tyche).

The Druckrey Collection contains a coin presenting a city’s tyche on a tetradrachm of the Phoenician city of Arados (No. 1282). She wears a mural crown, making her easily recognizable as the personification of the city of Arados. Such city goddesses were called tyche (“goddess of fate”) as they were supposed to embody the desired good fortune and prosperity of a city throughout the centuries. The tyche of Arados is well-coiffed. Small curls frame her graceful face, she wears earrings and a veil at the back of her head that falls over her shoulders. Throughout the Greek East, women wore many different types of veils. These veils were meant to reflect a woman’s good manners, her elegant modesty and respectability. The city goddess was considered a virgin, and she was to remain a virgin forever: no one was allowed to deflower her, i.e., to break the mural crown on her head. This idea of a virgin city persisted into the early modern period: When Tilly, the commander of the Catholic League, captured Protestant Magdeburg in 1631, this was ironically referred to as the “Magdeburg wedding”. With the breach of its walls, the city of Magdeburg (the name means “maiden city”) lost its virginity, it was raped. The “Magdeburg wedding” was more than just an image. Soldiers who were completely brutalized during the long and cruel Thirty Years’ War did terrible things to girls and women in Magdeburg. Similar incidents occurred in ancient times when cities were conquered, so it is understandable why the walls of a city should not be breached and why the “virginity” of a city’s deity was so important.

The goddess Athena often appears in the same role as a city’s tyche and acts as a patron goddess: a beautiful female head with a beautiful helmet can be seen on the obverse of many coins. There were two reasons why Athena was a visually decorative and highly symbolic motif on a coin’s obverse: For one, the Greeks imagined Athena to be a beautiful yet strong, even warlike goddess – she embodied an athletic type of a woman that also applied to the well-trained Spartan women

Fig. 1: The collector Dr. Eike Druckrey.

Didrachm of Hyele/Elea/Velia in Lucania, 340/334 BC: head of Athena with Attic helmet (Lot 1020; estimate: 200 euros).

Stater of an unknown Sicilian mint, c. 345/300 BC: head of Athena with Corinthian helmet (Lot 1032; estimate: 500 euros).

Tetradrachm of Arados in Phoenicia, 92/91 BC: city goddess with mural crown (No. 1282; estimate: 200 euros).

Drachm of Pharsalos in Thessaly, 424-404 BC: head of Athena with Attic helmet (Lot 1164; estimate: 500 euros).

Stater of Soloi in Cilicia, c. 385/350 BC: Athena with Attic helmet (Lot 1267; estimate: 1,250 euros).

Stater of Side in Pamphylia, c. 460/430 BC: Athena with Corinthian helmet (Lot 1263; estimate: 1,000 euros).

Drachm of the Brettian League, c. 215/205 BC: Hera Lakinia with veil (Lot 1021; estimate: 600 euros)

Drachm of Knidos, 449/411 BC: head of Aphrodite (Lot 1242; estimate: 500 euros).

Decadrachm of Syracuse, 400/379 BC: reed woven into the hair (Lot 1073; estimate: 10,000 euros).

Tetradrachm of Syracuse, after 480 BC: wreath hairstyle with hanging plait (Lot 1061; estimate: 400 euros).

Tetradrachm of Syracuse, after 480 BC: wreath hairstyle with folded over hanging plait (Lot 1062; estimate: 750 euros).

Tetradrachm of Syracuse, 450/440 BC: wreath hairstyle with intertwined neck braid (Lot 1065; estimate: 600 euros).

Tetradrachm of Syracuse, 420/415 BC: wreath hairstyle with ribbons and sakkos (Lot 1066; estimate: 1,250 euros).

Tetradrachm of Syracuse, 415/405 BC: wreath hairstyle with central rosette and tuft at the back of the head (Lot 1067; estimate: 2,000 euros).

Tetradrachm of Syracuse, 415/405 BC: wreath hairstyle with wide head band and curls taken out (Lot 1069; estimate: 5,000 euros).

Tetradrachm of Syracuse, 415/405 BC: wreath hairstyle with lampadion (Lot 1068; estimate: 2,500 euros).

who were considered by the Greeks to be beautiful and desirable representatives of the female sex. On the other hand, Athena was thought to be a virgin, just like the personified goddess of a city. Athena was therefore worshipped in many cities as the protector of a city and was invoked as “Poliás” (city goddess). However, other functions were also often attributed to her: Athena was also the patron goddess of olive trees, which were very important to the Greeks, of craftsmen and of new inventions. In the latter role, she was considered the goddess of science and thus of wisdom. To this day, Athena’s head is part of the emblem of many academic institutions (fig. 2).

A beautiful Sicilian stater without legend, reminiscent of the coins of Corinth, features the head of Athena with Corinthian helmet (No. 1032): Athena pushed the helmet back to reveal her face. The helmet has a neck guard, from which the goddess’s curls flow. On a didrachm from Hyele/Elea/Velia (No. 1020), Athena wears an Attic spherical helmet with panache and ornaments in the form of wings. Her face shows that she is determined to fight. A particularly graceful head of Athena can be found on a drachm from Thessalian Pharsalos (No. 1164). On this coin, the goddess also wears an Attic helmet with elaborately draped panache. The cheek flaps of the helmet are folded up, revealing the girlish beauty of her face on this coin in the Druckrey Collection. In contrast, Athena appears rather fierce, more warlike than beautiful, on a late classical stater (3rd quarter of the 5th century BC) from the Pamphylian city of Side (No. 1263). Although this city, which was then on the edge of the Greek world and whose people spoke a language of Asia Minor, made efforts to adopt Greek forms of art, it did not achieve the same level of beauty. Athena wears a Corinthian helmet without neck guard and with panache, which she pushed back. Another beautiful head of Athena can be seen on a very rare stater from the city of Soloi (No. 1267). The city, which was located even further east than Side in Cilicia, appears to have had an excellent engraver. He created a beautiful head of Athena with Attic helmet. In this case, the specific shape of the helmet may have been intentional. After all, it was said in Soloi that the city had been founded by the Athenian constitutional reformer Solon, due to the similarity in name. However, the citizens of Soloi had nothing to do with Athens’ cultural heyday, as they were known to speak poor Greek, so much so that certain linguistic errors are still referred to as Soloikisms today. On the coin from Soloi, Athena’s helmet is adorned with a leaping griffin. Griffins were mythological creatures whose back bodies were that of a lion, while they had a bird-like torso.

But the athletic, girlish type of Athena was not the only type in line with the Greek ideal of a woman. Women of a more mature age,

such as Hera, the wife of Zeus, were also popular. They could be considered beautiful and were depicted on coins. A stater of the southern Italian Brettian League depicts Hera Lakinia, who had an important sanctuary not far from the city of Kroton, as a beautiful and dignified middle-aged woman (No. 1021). Hera

wears a diadem and much jewelry. Earrings and necklaces are status symbols, as Hera is the wife of the highest god of the Greeks. This is also indicated by the scepter draped over her left shoulder. A loyal and exemplary wife and protector of the family, she wears a head veil. However, she was not particularly successful in this role with her notoriously unfaithful husband – no female beauty was safe from him. In a way, it was only logical that the supreme Greek god was depicted as a lover of beauty and the female beauty associated with it. Behind Hera, we can see a grasshopper with short tentacles: apparently, it is one of the dreaded migratory locusts that came in swarms from Africa and threatened to devour the abundant grain fields of southern Italy (for the depiction of the locust see S.M. Hurter, Crickets/Grasshoppers/ Locusts. A new view on some insect symbols on coins of Magna Graecia and Sicily, Nomismatika Chronika 23, 2004, 11-20). Hera Lakinia was apparently invoked to protect the grain harvest from the invasion of these dreaded insects.

The third goddess to enter the beauty contest on Mount Ida, not far from Troy, alongside athletic and beautiful Athena and Hera, the beautiful well-married woman in her prime, was Aphrodite. Her domain was all that had to do with female beauty. She was often stylized as the embodiment of aggressive beauty, a seductive force that could cause men to lose their minds, often leading to nasty arguments and even wars. In the Dr. Druckrey Collection, Aphrodite appears on a beautiful drachm, minted by the city of Knidos in the 2nd half of the 5th century BC (No. 1242). Knidos was one of the most important cult sites of Aphrodite in the Greek world. For Knidos, the Greek sculptor Praxiteles (c. 390-320 BC) created one of the most famous and seductive Aphrodite statues of the ancient world, Aphrodite of Knidos. It was one of the bestknown statues of the ancient world, and so far 200 imitations of this work have been found (fig. 3). On the coin from Knidos, which was struck several decades before Praxiteles created his marble statue, Aphrodite is depicted with a fierce expression while still maintaining her elaborate hairstyle. Her hair

Fig. 5: Fountain of Arethusa, JN.

Fig. 3: Praxiteles, Aphrodite of Knidos, Rome, Altemps Collection, JN.

Fig. 2: The head of Athena is still used in the signets of many academic institutions.

Fig. 4: Syracuse, peninsula of Ortygia from a bird’s eye view, Wikipedia, Agostino Artnoir Sella.

stretches over her head like a string of pearls, and a diadem-like ribbon is draped over the front of her head. At the nape of her neck, Aphrodite’s hair ends in a long hanging two-part braid that consists of an upper oval and a lower spherical section. Half of the upper oval section is covered by a piece of cloth, while the lower spherical section is completely wrapped in such a fabric.

The importance of her hairstyle for a woman’s beauty becomes particularly apparent on coins from Syracuse. They depict a woman’s head surrounded by four dolphins. In some cases, reeds is woven into the woman’s hair (No. 1073). All this indicates that the depicted woman is the nymph Arethusa. Water deities were frequently depicted on coins from Sicilian cities – river gods and beautiful nymphs. Given the hot summers, water was a precious commodity in Sicily. People, especially those living in larger cities, depended on fresh water springs. There is a good reason why the poet Pindar began his victory hymn to the Syracuse tyrant Hieron, whose racehorse won at Olympia in 476 BC, with the exclamation: “Water is best!” (Pindar, Olympian Odes 1.1). In ancient times, people believed that springs and trees were kept alive by beautiful young women who were considered daughters of Mother Earth and the sea god Oceanus. These women were referred to as nymphs. Time and again, virile vegetation gods – such as Pan and the satyrs – and river gods pursued these attractive young women. Many of them tried to escape the savages and preserve their virginity; after all, water was supposed to be pure. Therefore, the mistress of the water had to remain untouched. It was the goddess Artemis, who was averse to sexuality, who helped the nymphs fend off their intrusive admirers.

Arethusa is a common name for springs. It means something like “wetter”. According to myth, Arethusa was a nymph who once had her spring in the Greek mountains of Arcadia. Because of her beauty, the river god Alpheios, who flowed past Olympia, was attracted to her and pursued her. The goddess Artemis made sure that the beautiful Arcadian girl could escape. Arethusa is said to have disappeared under the Ionian Sea and resurfaced on the island of Ortygia (“Quail Island”), the settlement center of Syracuse (fig. 4 and 5). It is nothing short of a miracle that a freshwater spring emerged so close to the sea. This is another reason why Arethusa and her spring enjoyed so much popularity. The coins featuring Arethusa in the Druckrey Collection – most of which are of exquisite quality – show the nymph with so many beautiful hairstyles that the coins could still provide much inspiration for today’s hairstylists. The rapid evolution of Arethusa’s hairstyles also shows how women hairstyles were subject to ever-changing fashions even in ancient times. The basis was usually a wreath hairstyle (see M. Gkikaki, Die weiblichen Frisuren auf den Münzen und in der Großplastik zur Zeit der Klassik und des Hellenismus. Typen und Ikonologie, Diss. Univ. Würzburg, Würzburg 2011). The long hair, which stretched across the head in many segments, is depicted by fine incised lines, creating a cap of hair. This hair is parted in the middle and rolled over at the forehead. At the temples, the roll of hair falls down in front of the ears. At the nape of the neck, the fine hair of beautiful Arethusa ends in a hanging plait (No. 1061). On an exquisite tetradrachm (No. 1062), the hanging braid was wrapped around and ends at the back of the head in a tied bundle of hair. On another tetradrachm, the roll at the forehead is wavy rather than straight, while the braid in the neck is elaborately intertwined (No. 1065). Arethusa’s hairstyle on another coin is particularly distinctive (No. 1066): There are many ribbons woven into her hair, and they also cover the major part of the hanging braid. This is called a “sakkos”, or “sphendone” hairstyle, because the hair is covered in a “cap”

or a “headband”. Over time, Arethusa’s hairstyle had to adapt to new developments. The hanging braid became old-fashioned, and the hairstyle took on a two- or three-part form. On a tetradrachm (No. 1067), the forehead area is first framed by a wreath of curls; from the center of the head, the curls fall down in a rosette-like fashion, but are still close to the head; the back of the head is covered by a big tuft of hair. This tuft cannot be seen on another tetradrachm (No. 1068); only two individual curls fall down the neck from the two rolls of curls that are separated by a hair band. Above the middle of the head, curls are depicted like small flames, which is why the hairstyle was referred to as “lampadion” hairstyle. Lampadion means small torch; and our word for “lamp” derived from this root. On a beautiful tetradrachm with the name of Euainetos, Arethusa wears a wide, decorated hairband that wraps around her entire head, covering large parts of her hair. The central part of the head is segmented into thin strands like rosettes. Individual curls were taken out of the hairband to loosen up the hairstyle (No. 1069).

The numerous Syracusan pieces from the Dr. Druckrey Collection thus demonstrate the extent to which ancient beauty ideals focused on hairstyles.

Coins from other Greek cities also feature the heads of nymphs. A coin from Ternia (No. 1031), shows the nymph who gave the city its name. Like Arethusa, she has a wreath hairstyle and is adorned with beautiful earrings and a necklace. The other side of the coin features one of the most graceful depictions of the Greek goddess of victory, Nike. A winged young girl is seated on an altar, gazing at a bird that has just landed on her elegantly outstretched right hand. The goddess of victory wears a thin robe that accentuates her beautiful figure. The nymph Kamarina is depicted with similar grace on another didrachm (No. 1044). She was considered the ruler of the lake near the city of Kamarina, which is now dry, but was a gathering place for waterfowl of all kinds in ancient times. The Greeks appreciated the beauty of such bird paradises. In a famous passage in his Iliad (II 459-466), Homer described the flocks of birds in the Asian meadow on the Kaÿstros River, which flows into the sea near Ephesus. In Larissa in Thessaly (No. 1161) and Sinope in Asia Minor (No. 1194), the nymphs who gave these cities their names also adorn their coins. The nymph Larissa is depicted from the front, looking at the observer of the coin.

Along the north and west coasts of Asia Minor, there were cities that believed to have been founded by Amazons. These militant women, who according to myth had taken over the role of men, were also good coin motifs, as they embodied the city’s ability to defend itself and also made for a beautiful picture. In the Dr. Druckrey Collection, there is a tetradrachm depicting the Amazon Kyme (No. 1210).

1,7:1

The experiences cities had gained in depicting female city goddesses benefited the Hellenistic kings who wanted to immortalize their wives on coins. The beautiful and dignified portrait of Philistis, wife of Hieron II of Syracuse, depicts the queen with a veil in the style of the deity Demeter (No. 1091).

Dr. Eike Druckrey’s magnificent collection shows that it was primarily the head of a woman, rather than a full-body depiction, that expressed the beauty of female figures on coins that epitomized a city’s identity. Coins were too small of an object to convey to the people of antiquity what statues or the almost completely lost paintings of these times could express. The Greek cities and their artists were quick to recognize what depictions and what designs could be used to effectively highlight the beauty of their city goddesses on coins.

Prof. Dr. Johannes Nollé

Drachm of Larissa in Thessaly, c. 370/360 BC: The nymph Larissa (Lot 1161; estimate: 1,000 euros).

Drachm of Sinope in Pontos, c. 330/300 BC: The nymph Sinope (Lot 1194; estimate: 250 euros).

16-litrae coin by Hieron II, c. 240-216 BC: head of Philistis with veil (Lot 1091; estimate: 1,000 euros).

Stater of Terina, 400/356 BC: The nymph Ternia // Nike (Lot 1031; estimate: 4,000 euros).

Didrachm of Kamarina, 415/405 BC: The nymph Kamarina on a swan (Lot 1044; estimate: 7,500 euros).

Tetradrachm of Kyme in Aiolils: the Amazon Kyme (Lot 1210; estimate: 750 euros).

1,7:1

When Bavaria and Russia clashed …

Shortly after Carl Theodor, Count Palatine and Elector (1724–1799, reigned as Elector Carl IV of the Palatinate beginning in 1742 and as Carl II of the electorate of Bavaria) also took over the government in Bavaria, he tackled the project of re-establishing the English administrative “tongue” of the Order of Malta as the “English-Bavarian tongue” – this had previously been lost during the Reformation. In 1782, Grand Master Emanuel de Rohan Polduc (1725 –1797, reigned beginning 1775) established the Order’s Grand Priory of Bavaria. He endowed it with the properties of the Jesuit order, which had been dissolved by Pope Clement XIV (Lorenzo Ganganelli – 1705–1774, Pope beginning 1769) in 1773 under pressure from the Kings of France, Spain and Portugal. Carl Theodor appointed his illegitimate son Karl August von und zu Bretzenheim (1768–1823), who had become a Count in 1774 and a Prince in 1789, as Grand Prior from 1782 to 1799.

The Russian Tsar Pawel I (1754–1801, reigned 1796–1801) –Protector of the Order of Malta beginning 1797 and as of 1798, after the expulsion of the Order of Malta by the French General Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821, reigned from 1804 to 1814 and in 1815 as Emperor of the French) de facto Grand Master of the Order of Malta -- established a Catholic Grand Priory of the Order in the Russian Empire in 1797 as a result of the third partition of Poland in 1793. He attached it to the “English-Bavarian tongue” administrative division, which thus became the English-Bavarian-Russian “tongue” of the order. In the following year 1798, Pawel also founded an Orthodox Grand Priory of St. John of Jerusalem [Орден Святого Иоанна

in the Russian Empire, which he provided with 98 commanderies.

After the death of Carl Theodor on 16 February 1799, Maximilian IV Joseph of Palatinate-Zweibrücken-Birkenfeld (1756–1806, reigned as Elector Maximilian IV Joseph beginning 1799 and as King Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria beginning 1806) took over the government in Palatinate-Bavaria. On the day he took office, or two days later according to some sources, he dissolved the Grand Priory of Bavaria of the Order of Malta -- which was unpopular with the people anyway – by means of long-prepared measures and with immediate effect. He dismissed the Grand Prior Karl August, Prince of Bretzenheim, whom he hated (“the bastard son of his predecessor”) and had all the order’s estates confiscated in favour of the Royal Court

Chamber.

These actions resulted in extremely harsh countermeasures by the choleric Grand Master of the Order – the Russian Tsar Pawel I Petrovich – who interpreted this as a clear act of partisanship by Bavaria in favour of the French Republic and against the strategic interests of the Russian Empire. He saw his own interests as Grand Master of the Order and as Tsar (Emperor) of the Russian Empire as being clearly threatened by the ill-advised action of Bavaria. After receiving news of the move, Pawel I, in one of his infamous and universally-feared rages, ordered that the Bavarian ambassador to the court of St. Petersburg, Franz Xaver Freiherr von Reichlin-Meldegg, be taken into custody and forced to leave the Russian Empire immediately. The latter was taken by police (not even by the military!) in an extremely humiliating manner on a cart directly to the border of the Russian Empire, on the direct orders of the Tsar. The Tsar further ordered that the Russian army –which was on its way to France – was to immediately invade the Electorate of Bavaria. Neither Maximilian IV Joseph, nor his foreign minister Maximilian von Montgelas (1759-1838, in office from 1799 to 1817), nor the government of the Electorate of Bavaria had foreseen these reactions; they were therefore completely taken by surprise by the measures.

The matter was not to be allowed to escalate any further. It was decided to send a diplomatic mission to St. Petersburg to appease the angered Tsar Pawel and to negotiate with him: the elector’s brother-in-law, Wilhelm, Count Palatinate and Duke of Zweibrücken-Birkenfeld zu Gelnhausen (1752–1837), together with the Bailli Frà Johann Baptist Anton Freiherr von Flachslanden (1739–1822), Governor and administrator for the Grand Prior of Bavaria, and François Gabriel Chevalier de Bray (1765–1832), a skilled diplomat and “High Secret Adviser” in the Bavarian foreign ministry.

Elector Maximilian IV Joseph was forced to offer Tsar Pawel the withdrawal of all measures taken against the Order of Malta in Bavaria, to re-establish the Grand Priory of Bavaria, and to recognise the Russian Tsar as the legitimate Grand Master of the order. At the end of August, the legation reached St. Petersburg, and after brief but successful negotiations, an agreement was reached that essentially fulfilled all of Tsar Pawel’s demands. Only the dismissal of the previous Grand Prior Karl August Prince of Bretzenheim remained in force.

In his place, the Elector’s second son, Karl Theodor Prince of Bavaria (1795-1875), who was only four years old at the time, was appointed Grand Prior, and the Bailiff of Flachslanden as his Governor and thus the de facto regent of the Order of Malta in Bavaria. The Russian invasion was prevented, and with it the war against Bavaria, in which Bavaria would certainly have been defeated.

In gratitude for the favourable outcome of the affair, on 28 August 1799 Tsar Pawel I accepted Wilhelm of PalatinateBirkenfeld at Gelnhausen, Duke in Bavaria, as the 325th Knight of the Imperial Order of St. Apostle Andrew the FirstCalled [Имперáторский

and presented him with the order’s insignia in diamonds. At the same time, Wilhelm was admitted as a Commander to the Russian Grand Priory of the Order of Malta. The Bailiff of Flachslanden was appointed Russian General and received the Imperial Order of St. Prince Alexander Nevsky [Императорский

It is precisely this jewellery of the Order of Andrew, from the estate of Duke Wilhelm – though completely stripped of its jewels – that was presented to Duke Wilhelm in Bavaria by Tsar Pawel I Petrovich on 28 August 1799, and is now being offered in our Auction 415 on 28 October 2024 under lot number 371. It is likely to be one of the very few surviving diamond awards of the order from this period, even if only in the form of the casing. Experts nevertheless consider this object to be of historical and museum quality.

Michael Autengruber

Carl Theodor, Elector of Palatinate-Bavaria (1724-1799)

Prince Karl August of Bretzenheim (1768-1823)

Pavel I Petrovich, Tsar (Emperor) of Russia (1754-1801)

Literature:

Autengruber, Michael, and Feder, Klaus H.: Bayern und Malta – Das Großpriorat Bayern der Bayerischen Zunge des Souveränen Malteser Ritterordens und seine Insignien (1782-1808). Brannenburg and Konstanz 2002.

Freller, Thomas: The Anglo-Bavarian Langue of the Order of Malta. Malta 2001. Gavrilova, Liudmila: Treasures of the Order of Malta – Nine Centuries in the Service of Faith and Charity. Moscow 2012.

Taube, Baron Michel, de: L’Empereur Paul Ier de Russie Grand Maître de l'Ordre Souverain de Malte et “Grand Prieuré Russe” de l’Ordre de Saint-Jean-de-Jérusalem. Geneva and Paris 1982

Frà Johann Baptist Anton, Baron of Flachslanden (1739-1822)

Wilhelm Duke in Bavaria (1752-1837), around 1799

Wilhelm Duke in Bavaria (1752-1837), around 1810

Maximilian IV./I. Joseph Elector/King of Bavaria (1756-1825)

Maximilian von Montgelas (1759-1838)

Casing of the award of the Russian Order of St. Andrew in diamonds

Medals from the estates of ducal houses at Künker

At our Auction 415 of orders, decorations, coins and medals from the collections from the high nobility and of private individuals on 28 October 2024, a whole series of rare and very rare non-wearable medals, some in their cases, from the estates of ducal Bavarian and Württemberg and royal Bulgarian heirs will also be auctioned, including some early examples by the artist Karl Götz.

From the estate of Duke Max in Bavaria (“Zither-Maxl”, 1808 - 1888), father of the Austrian Empress Elisabeth (“Sisi”, 1837 - 1898), comes, for example, offered under Lot 361, the pair of official commemorative medals in gold for the marriage of Emperor Franz Joseph I (1830 - 1916, reigned beginning 1848) and Elisabeth Duchess in Bavaria on 24 April 1854 in Vienna, each for 35 ducats, diameter 55.8 mm, 986/000 ducat gold, weighing 122.2 and 122.3 g respectively, by Konrad Lange (1806 - 1856). The medals show the busts of the bridal couple on the obverse, facing right, with the die cutter’s signature “K.LANGE”. The reverse depicts the scene of the couple’s blessing by Joseph Othmar von Rauscher, Archbishop of Vienna, in the Augustinian Church in Vienna, and not -- as is often incorrectly stated in specialist literature -- in the Hofkapelle zu Wien. The two pieces are in the original, lavishly-designed presentation casket in Morocco leather, studded with brass appliqués, in which they were presented to Duke Max by his son-in-law, Emperor Franz Joseph I. These golden medals were only given to very close members of the bridal couple’s families.

A similar pair of medals, but in silver (Lot 362), comes from the estate of the younger brother of Empress Elisabeth, Carl Theodor, Duke in Bavaria (1839-1909). These two specimens are also in the original, lavishly-designed presentation casket in Morocco leather, studded with brass appliqués, in which they were presented to Duke Carl Theodor by his brother-inlaw Emperor Franz Joseph I. These are also somewhat rare examples of the medal, which should not be confused with the later restrikes, which are marked on the edge with “MÜNZE WIEN”.

From the estate of Maria José Duchess in Bavaria (1857-1943), née Infanta of Portugal, daughter of King Miguel I of Portugal (1802-1866, reigned from 1828 to 1834), married to Dr med. Carl Theodor Duke in Bavaria -- who later in life became an important ophthalmologist in München – comes the premium medal for services to medicine, which his wife Maria José Duchess in Bavaria donated on the occasion of the 70th birthday of Carl Theodor Duke in Bavaria on 9 August 1909 in gold, in silver (and in bronze?). The renowned medallist Alois Börsch (1855–1923) was commissioned with the design and production of the dies. The medals show on the obverse the bust of Carl Theodor facing left, with the die-cutter’s signature “A.BOERSCH” in the neck area; on the reverse is a five-line inscription in Latin under laurel branches. Of the gold medal, probably 14 ducats (Lot 285), diameter 41.1 mm, 986/000 gold, 48.7 g, only two copies were minted, the first in February 1910 (at 142.10 M), when Carl Theodor had already died, the second

Auction 415, Lot 361 Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Commemorative medal for the marriage of Emperor Franz Joseph I to Elisabeth, Duchess in Bavaria, on 24 April 1854 in Vienna.

A pair of gold medals, each worth 35 ducats.

In the original presentation box. From the estate of Duke Max Joseph in Bavaria (1808-1888). Extremely rare.

Estimate: 40,000 euros

in July 1910. Of the silver medal, silver, 44.2 g, two copies were struck (at 5.40 M) in February 1910. In July 1910, two more silver medals were struck, and in December 1910 another one in silver for the State Coin Collection. Three of these five copies are being offered in the auction (Lots 286, 287 and 288); the medals were no longer awarded due to the death of Carl Theodor on 30 November 1909.

The auction offers a whole range of other interesting Bavarian and foreign medals from the family of the dukes in Bavaria, including other rare pieces.

Michael Autengruber

Literature: Gebhardt, Klaus: Alois Börsch – Königlich Bayerischer Münz- und Hofmedailleur. München 1998.

The Ophthalmologist’s Sabre

On 11 October 1853, at the age of just fourteen, Carl Theodor Duke in Bavaria (1839–1909) joined the Bavarian army as a Second Lieutenant at the request of his father, Max Duke in Bavaria (1808–1888).

50 years later, having been promoted to General of Cavalry, equipped with his own regiment (the Royal Bavarian 3rd Chevaulegers Regiment Duke Carl Theodor), having been awarded a doctorate in medicine and become a renowned expert in ophthalmology with his own clinic, the Duke celebrated his fiftieth anniversary of service in the Bavarian army.

On this occasion, the officers of his regiment decided to present their sponsor with a special gift in the form of a Chevaulegers honorary sabre, for which the officers themselves raised the funds. The renowned armourer firm Karl Kaiser & Co. in Solingen was commissioned to make the sabre, and presumably also provided the design.

The design of the sabre blade, with its elaborate floral Art Nouveau decoration and Art Nouveau script, was striking even for München – the centre of the new style named after the magazine Die Jugend published there –and extremely modern for the time. This makes this sabre an important example of the widespread reception of this new art movement at the turn of the century, even in the decoration of military objects.

Michael Autengruber

It is an extraordinary, very luxuriously-crafted ceremonial sabre in the design of the sabres of the Royal Bavarian Chevaulegers, with a heavy grip handle showing a Bavarian lion and coat of arms, openwork, with floral decoration inside and outside, grip cap with lion’s head, the latter with red glass eyes, made of non-ferrous metal, hand-engraved, chased and gilded, probably with a polished bakelite handle with intact gold winding.

Artistically, however, the most remarkable feature of this sabre is the design of the blade: It is a Damascus steel blade with fullers on both sides, 93 cm long, with an etched floral Art Nouveau decoration, and the dedication in Art Nouveau script:

Das k. b. 3. Chevaulegers Regiment / seinem hohen Inhaber / HERZOG KARL THEODOR IN BAYERN K.HOHEIT / zur Feier seines 50jährigen Dienst= / Jubiläums am 11. Oktober 1903

… on the front side, as well as the names of the officers von Grundherr / Freiherr von / Gebsattel / Freiherr von / Crailsheim / Negrioli / Götz / Scherf / Schäffer / Cnopf / Willmer / Schrön / Hanemann / Thaler / Savoye / Münsterer / Welsch / Hammerbacher / Merckle / Freiherr von und / zu Aufsess / Herzog / Ludwig / Wilhelm / in Bayern / Richter / Lilier / Schilffarth / Roschmann

… on the back. The blade has a blued background and the raised parts are gilded. Unfortunately, it is not known who created this extremely tasteful Art Nouveau design, whether it was by the Kaiser & Co. company or by another artist. This purely decorative weapon has the manufacturer’s designation C / K / Co between two sabres on the ricasso, surmounted by an

Lot 325: A ceremonial sabre of the 3rd Chevaulegers Regiment made for the celebration of the golden service anniversary of Carl Theodor in Bavaria on 11 October 1903. Unique.

Estimate: 10,000 euros

Numismatic Museums Around the World: The Archaeological Museum in Zagreb

Today we want to share with you a positive story about a resilient group of people who refused to give up in the face of adversity: after being devastated by an earthquake in 2020, the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb opened its doors to the public again in July 2024. Numismatics played a significant role in this.

Iwill never forget my visit to the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb on 18 July 2020. My colleague, Prof. Dr. Ivan Mirnik, had promised to show me the coin cabinet, even though it was closed to the public. Only then did I learn just how much the entire cultural landscape of Zagreb had suffered from the consequences of an earthquake that I had not even heard about. Violent tremors had shaken the earth near Zagreb on 22 March 2020 – two weeks after the shock cancellation of the Numismata coin show. Our world had changed so rapidly since 7 March 2020, that news outlets were unable to cover everything that was happening. COVID-19 was dominating headlines – not only in Germany – and shifting attention away from other tragedies, such as an earthquake that had cost “only” one human life.

A Museum Destroyed

It was an intense magnitude 5.4 earthquake that rocked Zagreb. Several churches were severely damaged, and the roof of the Croatian parliament collapsed. The Archaeological Museum was also affected. Ceramics and glass display cases shattered, statues toppled, 178 exhibits were in some cases severely damaged, parts of the ceiling fell in, and the walls became tattooed with cracks. After the initial shock, curators rushed in to secure the objects. These were taken to the basement, only to be moved again hastily after a storm caused flooding in Zagreb at the end of March.

By the time I visited the museum in July, the initial shock had given way to a defiant “We’ll rebuild this no matter what!” sentiment. The curators of the Archaeological Museum have had all too much experience with this, unfortunately. The war for Croatia’s independence from communist Yugoslavia between 1991 and 1995 had also left the museum in ruins; it was not to be reopened until shortly before the new millennium. Dr. Mirnik told me at the time that the funds for reconstruction were more or less available. Scholars, the public and politicians unanimously agreed the work should be done as quickly as possible.

A Symbol of Croatian Identity

The Archaeological Museum in Zagreb represents the Croatian identity, as does its coin collection. It has its roots in the Croatian national movement of the 19th century. The “Young Illyrians”, opposed to the Habsburg rule of the time, collected anything and everything that documented the emergence of Croatia as a nation. Coins played a very special role in this.

The Archaeological Museum showcased this in an exhibition in 2019, at a time when Croatia was preparing for the introduction of the euro. This meant that the country was abandoning its national currency, the kuna. Currencies with this name have existed on Croatian soil since the Middle Ages. The name likely dates back to the era of pre-money economy; the word “kuna” means marten, and marten pelts were the currency in which taxes and duties were paid in the Croatian region during the early Middle Ages.

Croatians are thus well aware even to this day of how important coins are for the identity of a nation, and that this is the reason the “Young Illyrians” started a coin collection in the 19th century. This collection was transferred to the new National Museum – the predecessor of the Archaeological Museum – upon its founding in 1836. The first curator cataloged approximately 1,000 coins. He was able to joyfully witness the rapid expansion of his collection. A little over a decade later, the catalog already comprised 26,000 items. By 1900, the Archaeological Museum’s coin collection had swelled to an impressive 100,000 items. They have been and indeed still are the subject of numerous numismatic catalogs and monographs, which the team of numismatists at the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb regularly publishes in both Croatian and English.

Today, the Archaeological Museum’s coin collection comprises some 280,000 items – mostly Roman coins, although the research focus leans more toward Celtic and medieval coinage.

Swift Reconstruction

It took four years to repair the worst of the damage and renovate the museum interior. A sum of 2 million euros was invested, most of which came from insurance. Financing was supplemented with a solidarity fund, domestic and international donations as well as funding from the city of Zagreb itself. A decision was taken to simultaneously earthquake-proof the building. Zagreb, after all, is situated at the junction of the Eurasian and African plates, rendering earthquakes relatively common. Indeed, the city even owes its present appearance to an earthquake. The modern city with the prestigious buildings we know today was only created after the earthquake of 1880 had reduced Zagreb – known at that time as Agram – to ruins.

Now only renovation of the façade is still pending. It will cost around 3 million euros, which Mayor Tomislav Tomašević has promised to finance from the city budget.

Coins in the Exhibition

Before the earthquake, the numismatic department had a permanent exhibition open to the public which had been compiled during the era of communist Yugoslavia. The people of Zagreb were very proud of the exhibition, as the presentation of the objects was groundbreaking for its time. In a darkened room almost reminiscent of a treasure vault, the coins were displayed on large plates and illuminated with spotlights. While this might differ somewhat to present day display methods, the creativity of the exhibition organizers deserves our respect. After all, in the shortage economy of communist Yugoslavia, they did not have the same resources available as we do today.

Nevertheless, the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb has now opted to follow the trend and integrate the coins into the general exhibition – resulting in several display cases containing coins that make the people of Zagreb justifiably proud.

The exhibition is just temporary, however. Miroslav Nađ, senior curator in the numismatic department, explains that only a few highlights are currently on display. As soon as circumstances allow it, a new permanent exhibition is to be designed, in which a much greater number of coins will be displayed.

The earthquake in Zagreb caused the tip of the cathedral’s southern spire, which was scaffolded at the time, to break off. Photo: UK.

The Mazin Hoard

Nevertheless, the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb is certainly worth a visit for anyone interested in numismatics. One highlight of the current exhibition, for example, is the hoard discovered in Mazin. It is testament to the extensive trade network of the Iapydes, a Celtic tribe that settled inland between the Istrian peninsula and Dalmatia from around the 9th century BC. Relatively little is known about the Iapydes, except that they ravaged Aquileia in 171 BC. The Romans repeatedly waged campaigns in their territory. At the hands of Augustus, the Iapydes were forcibly placed under Roman rule in a civitas.

The Mazin hoard was probably buried sometime during the first half of the 1st century BC. The hoard contains a vast array of items that actually have just one thing in common: they are all made of bronze, which was used to make weapons, tools and jewelry. It includes not only fragments of damaged bronze objects, but also heavy Roman coins, i.e. aes grave (45 pieces), aes signatum (17 pieces) and aes rude (456 pieces), as well as Roman Republic asses and the fractional pieces thereof. They all served as melting material – as did large bronze coins from Carthage (505 pieces) and Egypt (40 pieces) – and even two coins from Hieron II of Syracuse and the Arcadian city of Caphyae found their way into this hoard.

Discovered in a stone chest in 1896, the hoard also lent its name to other hoard discoveries of similar compositions. They take us back to the period of transition between money and ingots, show that what functioned as a coin in Roman and Greek cities quickly became an ingot again in rural areas, and illustrate just how seamless the transition from money to a means of barter was in ancient times.

The Mazin hoard is just one example of the many interesting objects and hoard discoveries housed at the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb. If you end up visiting the Croatian capital during your vacation, be sure to plan a trip to the Archaeological Museum. And not just for the coins! Also because the resilience of our Croatian colleagues deserves respect.

Sometimes, it is not about putting on the biggest exhibition with the most amazing coins, but about spreading the joy and knowledge of numismatics against all odds!

Dr. Ursula Kampmann

A glimpse of the half-empty museum. Two toppled statues are still to be moved the basement. Photo: UK.

During my visit back in July 2020, the first signs were already visible that reconstruction work was to begin soon. Photo: UK.

A glimpse of the renovated rooms.

Photo: Miroslav Nađ / Archaeological Museum in Zagreb.

The Mazin hoard. Photo: Miroslav Nađ / Archaeological Museum in Zagreb.

The coin cabinet on the ground floor was temporarily used to store the rescued objects. Photo: UK.

Republic of Croatia. 500 kuna, 1941.

From the possession of the family of Croatian dictator Ante Pavelić.

From Künker auction 256 (2014), No. 6732.

Estimate: 3,000 euros. Hammer price: 5,000 euros. 2:1

Gold from Rhodes for the Battle for Rome

On 30 November 2024, Künker will be auctioning an aureus minted by Caesar’s assassins in 42 BC. The extremely rare piece is estimated at 100,000 euros. We tell the story of a coin that takes us back to the heart of the Roman civil war.

It always seems so simple: a knife, a bullet, a bit of poison and the tyrant is gone and freedom restored. But the men who successfully assassinated Caesar on the Ides of March in 44 BC found out that, unfortunately, the world does not work this way. Although Caesar fell to their daggers, nothing that happened afterwards went as planned: no one was interested in Brutus’ eloquent appeal to restore the Republic as his audience had fled to safety.

Brutus and Cassius Driven Out of Rome

What was to happen after the assassination? Nobody knew. So they decided to do nothing for the time being. On 17 March 44 BC, the survivors agreed not to change Caesar’s decrees, while his assassins were granted amnesty. This was a declaration of political ruin for both sides. Brutus and Cassius did not reap the fruits of their conspiracy, and Mark Antony refrained from taking revenge.

Of course, this agreement was not permanent. It was only a means to buy time for the battle lines to be drawn. In this process, Mark Antony discovered what a good hand fade had dealt him. He was a consul, while his opponents Cassius and Brutus were only praetors. This opened up a number of possibilities for him.

At the beginning of June, Mark Antony succeeded in persuading the Senate to assign his opponents the task of procuring grain in the provinces of Asia and Sicily respectively. An affront! A praetor’s place was in Rome. This mission was nothing more than a nicely disguised way of taking away their praetorships. It was a declaration of war, and it was understood as such. The next coup followed a few days later. Mark Antony had the Senate vote on which provinces Cassius and Brutus were to administer once they had completed their terms as praetors. They were given Crete and Cyrene respectively – the least important provinces in the entire Roman Republic! But