NEWS FROM THE AUCTION AND GOLD MARKET

Dear Customers,

Dear Coin Enthusiasts,

In view of the tropical temperatures of over 30 degrees Celsius here in Germany at the time of going to press, it’s hard to imagine that we are about to hold our autumn auctions, Part 1, which will take place from 23 to 28 September at the usual location in Osnabrück. Over these six days we will be auctioning around 3,900 lots with a total estimated value of 10 million euros. The numismatic rarities fill five auction catalogues. On the first pages of this issue you will find a detailed preliminary report on Auctions 410 to 414. In addition, we take a closer look at some topics and collections -- for example on pages 7-8, where the collection of Heinz-Falk Gaiser on the subject of Württemberg coin history is described.

Last autumn, we auctioned the first part of the Lodewijk S. Beuth collection in Auction 393, in cooperation with Laurens Schulman B.V. The first part comprised the “Coins of the Netherlands and the Dutch overseas territories since 1795” and is now being supplemented by the second part, “Coins of the Netherlands from the beginnings under the Merovingians to 1795” (Auction 414, in collaboration with Laurens Schulman B.V.). We are delighted to auction the second part of this important collection of Dutch coins, and thus help make the history of our neighbouring country become better known. Dr Margret Nolle and Manuela Weiss have cooperated to produce a numismaticallyand historically informative catalogue that brings to life the history of the Netherlands from its beginnings to its

transition to the Batavian Republic, using beautiful and often extremely rare coins to bring the past to life before our eyes. Our trade fair team was also on the road again this summer, visiting international coin fairs. Among other activities, we were pleased to sponsor the first Evento Numismatico in Madrid, which included both a coin fair and a convention to which prominent Spanish numismatic experts were invited. The convention included a visit to the mint in Segovia, about which we report in more detail on pages 16 and 17. The American World's Fair of Money was on our programme again too.

On pages 18-21, Professor Johannes Nolle has once again published a lecture that he gave to the numismatic association “Münzfreunde MannheimLudwigshafen” as part of our historical programme. It’s about elephants and their images on coins.

The viewing of the items in our autumn auctions, Part 1, will be possible on our premises until 28 September 2024, and we want to inform you that selected coins from the autumn auction of our partner “Myntauktioner i Sverige AB” in Stockholm will also be on display in Osnabrück from Tuesday, 17 September to Monday, 23 September 2024. We ask you to kindly make an appointment in advance by calling +49 (0)541-962020. For lovers of coins from the ancient world and collectors of orders and decorations, Part 2 of our autumn auctions will take place at the usual location in Osnabrück from 28-30 October 2024. A separate edition of Künker Exklusiv will be published for these auctions.

We hope you enjoy reading this latest issue, and we look forward to seeing you in person during our fall auctions at the Vienna House Remarque in Osnabrück.

Dr. Andreas Kaiser Ulrich Künker

Six Days of Thrilling Numismatic Excitement in Osnabrück – Preview

of our Fall Auction Sales 410-414

Our Fall Auction Sales will feature several world-class special collections. The topics include the Thirty Years’ War, Lösers, Württemberg, the German Empire, the Netherlands, Russia, the U.S. and precious individual pieces from the German states and all over the world.

O

ur Fall Auction Sales will take place from Monday 23 to Saturday 28 September 2024. Every single day is bursting with numismatic highlights, as several special collectors have entrusted Künker with the sale of their treasures, allowing their pieces to re-enter the numismatic cycle. Customers will therefore encounter several world-class collections:

• Auction 410: Minted history of the 30 Years‘ War and the Peace of Westphalia – The collection of a German Manufacturer and History enthusiast

• Auction 411: Coin History of Württemberg –The Heinz-Falk Gaiser Collection, Part 1

• Auction 412: Gold coins, including US coins | Coins and medals from the Medieval and Modern Times, including the Regina Adams Collection of Löser

• Auction 413: German coins since 1871, including an important collection from private ownership in Mecklenburg

• Auction 414: The Lodewijk S. Beuth Collection, Part 2 –Coins of the Netherlands from the beginnings under the Merovingians to 1795

Our total estimate for the approximately 3900 lots amounts to 10 million euros. And while we will naturally be highlighting spectacular individual pieces in this preview, no collector should miss out on the opportunity to browse the catalogs carefully. As there are many collections on offer, there are numerous lots with estimates in the two- and low three-digit range.

Auction Sales are always a social event. So take the time to participate in the sale on site, and enjoy a nice chat with like-minded people during the breaks!

Minted History of the Thirty Years’ War and the Peace of Westphalia – The Collection of a German Manufacturer and History Enthusiast

There is really only one word to describe this collection –breathtaking. Leafing through the almost 400 pages of the catalog, admiring the countless multiple gold coins and multiple talers from the period of the Thirty Years’ War simply takes your breath away. The German manufacturer and history enthusiast who put together this collection over decades did not limit himself to the German players in this war. His focus is on Europe as a whole, which is why his collection paints a dramatic picture of intra-European entanglements.

As a result, all the major and minor protagonists of the Thirty Years’ War can be found on the coins: the Emperor as well as the Swedish, Danish, English and French kings; the Spanish Habsburgs as well as Italian princes. And in terms of beauty, the coins and medals of the United Provinces of the Netherlands compete with those of the German territories. Anyone looking at the material will be in awe of the numismatic splendor created at the transition from the late Renaissance to the early Baroque period.

Our Specialists have taken great care to present this unique collection in its historical context. For this reason, numerous comments on the history of the Thirty Years’ War and its historical figures can be found throughout the catalog.

Johannes Nollé tells us more in his article on pages 22-23 of this issue.

Lot 15: England. Charles I, 1625-1649. Triple Unite, 1642, Oxford. Mint mark plumes. Very rare. About extremely fine.

Estimate: 40,000 euros

Lot 45: Poland. Sigismund III, 1587-1632. 1627 reichstaler, Bydgoszcz. Very rare. Very fine.

Estimate: 40,000 euros

Lot 94: Hungary / Transylvania. Georg Rakoczi, 1630-1648. 10 ducats, 1631, Kolozsvár. Very rare. Very fine +.

Estimate: 50,000 euros

Lot 84: Spain. Philip IV, 1621-1665. 1632 cincuentin (50 reales), Segovia. Only 10 specimens known. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 30,000 euros

Lot 132: Habsburg hereditary lands. Ferdinand III, 1625-1637-1657. 10 ducats, 1650, Breslau. Probably unique. Very fine +.

Estimate: 75,000 euros

Lot 305: German States / Nuremberg. 10 ducats, 1627. Extremely rare. Extremely fine.

Estimate: 50,000 euros

Lot 142: County of Schlick. Henry IV, 1612-1650. 10 ducats, 1630. Unique. Extremely fine. Estimate: 100,000 euros

Lot 409: German States / Holstein-Schauenburg. Justus Hermann, 1622-1635. 4 ducats, 1624. 2nd known specimen. Very fine.

Estimate: 50,000 euros

Lot 425: German States / Wallenstein. 1627 double reichstaler, Jitschin. Very rare. Very fine. Estimate: 50,000 euros

A Monetary History of Württemberg –The Heinz-Falk Gaiser Collection, Part 1

Are you interested in Württemberg and its coins? In this case, you will be amazed by the Heinz-Falk Gaiser Collection. The avid collector focused on this field for decades. With much patience, expertise and enthusiasm, he succeeded in putting together a world-class collection of Württemberg issues. The first part including 153 lots will be crossing the auction block on 23 September 2024.

It contains Württemberg coins from the beginnings of the 14th century up to 1693, when Eberhard Ludwig was prematurely proclaimed of age. The coins therefore portray the old state of Württemberg, which got caught up in the conflict over Protestantism and partly came under imperial rule.

Like any truly committed specialist collector, Heinz-Falk Gaiser not only looked for rare and precious denominations, but placed equal importance on adding fractional coins to his ensemble. As a result, he was able to acquire many extremely rare denominations of the highest quality available on the market. Although many of them have estimates in the double and low triple digits, his coins are of a quality that both collectors and curators dream of.

It was only on rare occasions that Heinz-Falk Gaiser allowed himself to “get carried away”, as he put it. But since he collected coins for decades, these “rare occasions” were frequent enough to secure some of the great rarities of Württemberg numismatics. Those who are not collectors of Württemberg coinage, but are rather interested in artistic Renaissance pieces will therefore find some numismatic icons of the finest quality. After all, Heinz-Falk Gaiser paid special attention to the quality of his pieces. Therefore, even the ‘only’ very fine issues are often the best specimen of the respective type that exist on the market.

Lot 769: Württemberg. Ulrich, 1498-1550. 1507 taler, Stuttgart. “Reitertaler” (horseman taler). Very rare. Probably the finest specimen in private possession. Extremely fine. Estimate: 30,000 euros

Lot 800: Württemberg. Louis the Pious, 1568-1593. 1585 taler, Stuttgart, minted from the silver of the Christophtal mine to celebrate his wedding to Ursula von Pfalz-Veldenz. Only 458 specimens minted. Very fine to extremely fine.

Estimate: 15,000 euros

Lot 830: Württemberg. John Frederick, 1608-1628. 2 ducats, 1623, Stuttgart, minted to celebrate his being appointed Circle Colonel of the Swabian Circle in 1622. Very rare. About extremely fine.

Estimate: 15,000 euros

Lot 868: Württemberg.

Louis Frederick, administrator and guardian of Duke Eberhard III, 1628-1631. 1/2 reichstaler, 1629, Stuttgart-Berg, minted from the silver of the Christophsthal mine. Extremely rare. Extremely fine.

Estimate: 15,000 euros

Lot 877: Württemberg.

Eberhard III, 1633-1674. 1640 reichstaler, Stuttgart-Berg. Very rare. Extremely fine.

Estimate: 15,000 euros

Lot 888: Württemberg.

William Louis, 1674-1677. 1677 reichstaler, Stuttgart. Very rare. Extremely fine.

Estimate: 15,000 euros

Auction 412: Gold and Silver Coins with Numerous Special Collections

24 and 25 September 2024 are designated for our general auction sale. But what does “general” even mean? The special collections offered on these days were simply not large enough to be presented in a separate catalog. But of course, they are just as important as the other collections.

The Regina Adams Collection

The Regina Adams Collection, for example, “only” contains 31 selected lösers of the Welf dynasty – however, it is incredibly difficult to find 31 lösers of such extraordinary quality. It was of utmost importance to the collector to be able to see every single detail of the motif. On page 15 you will find a detailed description of this collection.

Lot 1543: Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. Friedrich Ulrich, 1613-1634. 1625 löser of 2 reichstalers, Goslar or Zellerfeld. Yield of the mine of Saint James (“St. Jacob”) near Lautenthal. Extremely rare. Extremely fine +.

Estimate: 15,000 euros

Lot 1544: Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. Augustus II the Younger, 1635-1666. 1638 löser of 5 reichstalers, Zellerfeld, celebrating the emperor’s confirmation of the succession. Extremely rare. Extremely fine to FDC.

Estimate: 40,000 euros

Los 1551:

Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. August the Younger, 1635-1666. On the death of the duke. Löser of 4 reichstalers, Zellerfeld. Extremely rare. Extremely fine.

Estimate: 40,000 euros

Ivan III (IV)

Atragic chapter in Russian history is at the heart of this collection: Newborn Ivan was installed on the Russian throne at just 2 months old, only to be overthrown one year later. But what do you do with an innocent child that had been tsar for a short time? Elizabeth Petrovna, the daughter of Peter the Great, became Empress of Russia in 1741. She kept Ivan in captivity throughout her entire reign. Catherine the Great, who liked to present herself as an enlightened monarch, considered this to be dangerous – so she had Ivan killed in 1764.

Only a few coins were minted during Ivan’s rule from 28 October 1740 until 6 December 1741. We are able to offer 16 of them – an incredibly large number given Ivan’s short reign.

Lot 1848: Russia. Ivan III (VI), 1740-1741. 1741 rouble, Moscow, Red Mint. Very rare, especially in this quality. About extremely fine.

Estimate: 20,000 euros

By the way, if you are interested in Russian numismatics but cannot afford the coins of Ivan III (IV), there is another special collection on offer : 54 lots from the time of Paul I, including numerous copper coins of spectacular quality. Estimates start as low as 10 euros.

Lot 1852: Russia. Ivan III (VI), 1740-1741. 1741 rouble, Saint Petersburg. With special edge minting (chain edge). Extremely rare. About extremely fine.

Estimate: 100,000 euros

Estimate:

U.S. Gold Coins

And there is a third special collection to be offered in catalog 412. Almost 200 lots with U.S. gold coins – mainly Double Eagles – will be crossing the auction block. Of course, the offer features many great rarities. All pieces were graded.

Lot 1504: U.S.A. 20 dollars 1929, Philadelphia. PCGS MS65. Extremely rare. Extremely fine to FDC.

Estimate: 20,000 euros

A Great Selection of Rarities

It goes without saying that auction 412 also contains rare coins from many other parts of the world. At this point, we present you two examples: a modern Chinese coin set of which only 50 specimens exist, and a 1581 broad taler of Cologne of 2 1/2 talers, the only known specimen in private hands.

Los 1506: U.S.A. 5 dollars 1800, Philadelphia. NGC MS64PL. Extremely fine to FDC.

Estimate: 30,000 euros

Los 1276: China.

Commemorative coin set 1900 “Dragon and Phoenix”.

Set No. 9 of 50 issued sets. Proof.

Estimate: 50,000 euros

Los 1606: German States / Cologne. Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg, 1577-1583. Broad 2 1/2 taler 1581. Extremely rare. Of the highest historical and numismatic importance. The only known specimen in private possession. Extremely fine.

Estimate: 75,000 euros

Lot 1907: Russia. Paul I, 1796-1801. 1798 copper kopeck, Suzun (Kolyvan). Novodel. Very rare. About FDC.

2,000 euros

Catalog 413: German Coins After 1871

Lot 3220: Reuss, elder line. Heinrich XXII, 1859-1902. 20 marks 1875. Very rare. Extremely fine to FDC.

Estimate: 35,000 euros

More than 1,000 German rarities minted after 1871 are offered in auction 413. They include a collection from a Mecklenburg private collector as well as imperial gold coins from the collection of an industrial entrepreneur from western Germany. Look forward to the great rarities of the German Empire such as 3 marks Frederick the Wise, 20 marks Heinrich XXII of Reuss, elder line, 20 marks Ernest II of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha as well as 20 New Guinean marks.

Estimate: 100,000 euros

Lot 3272: Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Ernest II, 1844-1893. 20 marks 1872. Very rare. Above-average quality. About extremely fine.

Estimate: 50,000 euros

Lot 3360: German New Guinea. 20 New Guinean marks 1895.

Only 1,500 specimens minted. NGC PF64 CAMEO. Proof.

Estimate: 50,000 euros

Catalog 414: Dutch Coins from the Lodewijk S. Beuth Collection, Part 2

On 27 and 28 September 2023, we realized incredible results with the sale of the first part of the Lodewijk S. Beuth Collection. At the time, the about 1,200 lots were sold in collaboration with Laurens Schulman B. V. and fetched a total result of 5.2 million euros. Ten lots were sold for six-figure results.

Now – once again in collaboration with Laurens Schulman B. V. – the second part of the collection will be on offer. It contains coins from the beginnings of the Netherlands under the Merovingians up to 1795.

Estimate: 25,000 euros

1,3:1

Estimate: 20,000 euros

Following the traditional order of Dutch numismatics, the elaborately designed catalog presents Dutch coins arranged according to the seven northern provinces.

Do we need to say more? Connoisseurs know exactly what the Lodewijk S. Beuth Collection stands for: extraordinarily rare coins of unusual quality that have not been seen on the market for decades. Collectors of Dutch coins who do not carefully study this catalog have only themselves to blame.

Off-metal

in

Estimate: 20,000 euros

Lot 4598: Zeeland. 30 guldens, 1683, Middelburg. Extremely rare. Extremely fine +.

Estimate: 25,000 euros

Lot 5055: Kampen. Double rose noble n.d. (1600). Imitation of a sovereign by English Queen Elizabeth. Only 5-6 specimens are known of. Extremely fine.

Estimate: 75,000 euros

To order a catalog contact Künker, Nobbenburger Straße 4a, 49076 Osnabrück; phone: +49 541 962020; fax: +49 541 9620222; or via e-mail: service@kuenker.de. You can access the auction catalogs online at www.kuenker.de. If you want to submit your bid from your computer at home, please remember to register for this service in good time.

For auction catalogs 410-414 and a detailed auction overview simply scan the adjacent QR code

Lot 4316: Holland. Philip the Handsome. 1487 broad real d’or, Dordrecht. Very rare. Very fine.

Lot 4377: Holland.

strike

gold of 5 ducats from the dies of the 25 stuiver from 1694, Dordrecht. Extremely rare. FDC.

Lot 4462: Holland / Amsterdam. 5-ducat piedfort of 1673, Amsterdam. Minted during the siege by French troops. Very rare. About FDC.

Lot 2823: Saxony. 3 marks 1917 E “Frederick the Wise”. On the 400th Reformation Jubilee. Very rare. Proof.

Württemberg – Regional History as Reflected

in Coins

In Auction 411, we present a very high-quality and historically interesting collection of rare Württemberg coins. This extraordinary collection brings Württemberg’s regional history to life through the coinage of its rulers, in an almost complete series from the 14th to the end of the 17th century. (Fig. 1).

A special feature of Württemberg’s history is the fact that in no other territory of the Old Empire did the dukes have to share their power with the regional estates. “Nowhere do the estates have more prestige and weight than in Wirtemberg”, a travel writer noted in the 18th century. The Württemberg estates represented in the state parliament (also known as the “Ehrbarkeit”), which comprised the landed gentry and the middle classes of the state, and Duke Ulrich I concluded the “Tübingen Treaty” on 8 July 1514 (Fig. 3). In it, the Duke undertook to regulate matters of taxation, national defence, justice, and warfare, as well as the sale of parts of the country, only with the consent of the estates. After this agreement, the sovereign was partially disempowered by the state parliament in the execution of fundamental state affairs. The Tübingen Treaty is considered one of the world’s earliest constitutional documents, along with the Magna Carta of England. It offers unique testimony to the separation of powers in the late Middle Ages -- and was to remain in force until 1806. However, this dualism in the governance of the country repeatedly led to violent conflicts between the estates and the ruling dukes, especially on issues of taxation and expenditure on the maintenance of a standing army.

Württemberg, a state of the Holy Roman Empire which existed from the High Middle Ages on, derived its name from a castle on the “Wirtemberg” (today in StuttgartRotenberg), of which only a few remains still exist. A certain Konrad von Wirtemberg, who was apparently also the builder of the castle of the same name, is mentioned in a document from the year 1081. In the 12th century, the “Wirtemberger” family was elevated to the rank of counts; by the end of the 14th century, they had managed to steadily expand their core territorial possessions, primarily through advantageous marriages. The most significant territorial acquisition was the County of Mömpelgard (French: Montbéliard, now the Département Doubs in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region), which Count Eberhard III was able to secure for himself in 1397. The Nürtingen Treaty of 25 January 1442 established a peaceful division of the land of Württemberg between Count Ludwig I and his brother Ulrich V. According to this, Ludwig received the Urach part with the areas of the county in the west and south and the possessions in Alsace, while Ulrich was awarded the Stuttgart part. With the Münsingen Treaty of 14 December 1482 and the Esslingen Treaty of 2 September 1492, Count Eberhard V im Bart of Württemberg-Urach, the later Duke Eberhard I, succeeded in reversing the division of Württemberg. In this agreement, the indivisibility of the country and the right of primogeniture were established for all time with the participation of the estates, an important prerequisite for the elevation of Württemberg to a duchy by Emperor Maximilian I at the Imperial Diet in Worms on 21 July 1495. Duke Eberhard im Bart, who is still revered in Württemberg today and who was celebrated by the Württemberg poet Justinus Kerner in his poem “Der reichste Fürst” (in his musical arrangement, it is the unofficial state anthem of Württemberg!), gave Württemberg its first state constitution and founded the University of Tübingen in 1477, which soon developed into a centre of learning with outstanding scholars (Fig. 2).

3: Auction 411, Lot 780, Ulrich, 1498-1550. Ducat 1537,

: MO : PEL : Bust left with large beret//MONE

NO

AVR

WIRTENBER

I537

Four-field coat of arms (Württemberg, Teck/imperial storm flag, Mömpelgard). Estimate: 7,500 euros

in the upper field on the left the antlers of the House of Württemberg, on the upper right the rhombuses for Teck, on the lower left the imperial storm flag with the black eagle, on the lower right two fish for the County of Mömpelgard.

Duke Ulrich I -- who signed the Tübingen Treaty -- caused such political and military turmoil through a sensational murder of his equerry Hans von Hutten in Württemberg, out of jealousy, that Emperor Charles V put him under a severe ban (German: “Acht und Aberacht”) in 1516 and placed the country under Habsburg rule. Ulrich was forced into exile for 15 years and Archduke Ferdinand of Austria, the future Holy Roman Emperor, became the provisional ruler of Württemberg. It was not until July 1534 that Duke Ulrich was able to return to the state, which he received from King Ferdinand I only as a fiefdom of the empire. As a result of the duchy joining the Schmalkaldic League, Ulrich introduced the Reformation with a Lutheran orientation throughout the country in 1534. In the course of this transformation he secularised all Catholic church

property. During the reign of his son Duke Christoph (1550 –1568), a great many regulations and laws were drawn up; the Great Church Order of 1559, following the Peace of Augsburg, became the state’s basic law with the decisive involvement of the reformer Johannes Brenz.

At the turn of the 17th century, Württemberg experienced a significant economic boom under Duke Friedrich I (1593–1608). The Duke was not only successful at expanding his rule, but also pursued an active economic policy in the mercantilist style as a representative of early absolutism (Fig. 4). In order to closely link the newly acquired Oberkirch office and the city in the Renchtal valley with Württemberg, he had a road built over the river Kniebis, which promoted the expansion and commercial viability of the Christophstal mine in the northern Black Forest. The mining and smelting operations there were intended to guarantee the country’s self-sufficiency in raw materials.

Fig. 4: Auction 411, Lot 816, Frederick I 1593-1608. Reichstaler 1607, Christophstal, with the title Rudolf II. 28.45 g. Stamp cutter Jean (Johann) Cassignot. • FRIDERICVS • D • G • DVX • WIRTEMBERG • Triple-helmeted, four-field coat of arms (W•rttemberg, Teck/imperial storm flag, Mömpelgard), below to the sides the divided date 16 • - • 07//• RVDOL PH • II • IMP AVG • P • F • DECRETO • St Christopher with the Christ-child on his left shoulder strides through a river, in his right hand a tree trunk, in his left an eagle shield in a baroque cartouche, below in a decorative border the date • 16 • 07 •.

Estimate: 10,000 euros

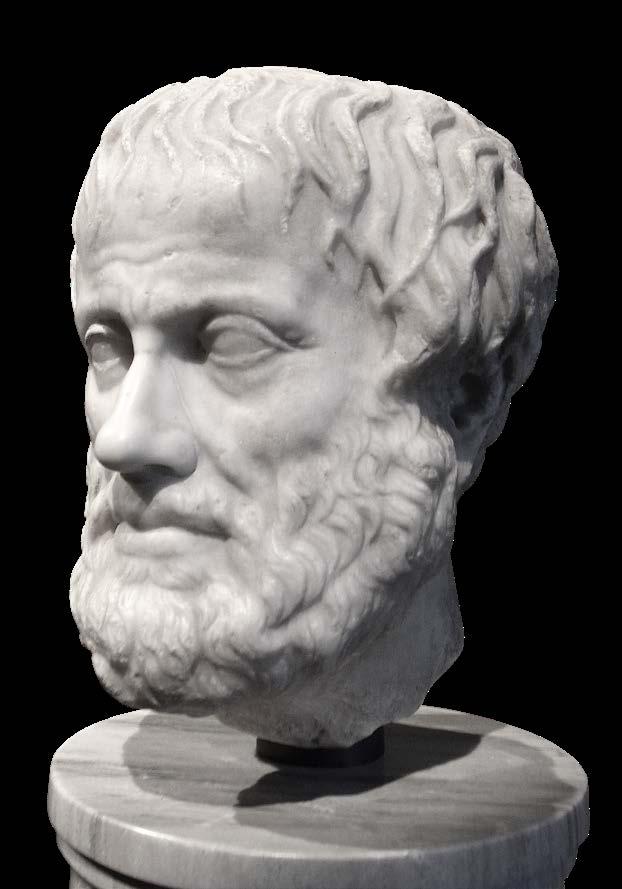

Fig. 1: The crowned, quartered coat of arms of the Dukes of Württemberg from the armorial of Johann Siebmacher (1561-1611);

Fig. 2: Equestrian statue of Duke Eberhard I im Bart in bronze by Ludwig Hofer (1859), courtyard of the Old Palace in Stuttgart.

Fig.

Stuttgart. 3.49 g.

A mint and a brass mill were also built, and brass was produced. By encouraging the immigration of Protestant refugees who had been driven out of Carinthia, Carniola and Styria by the Catholic Habsburgs in 1599, he acquired experienced miners who had found new homes in the region. The Duke had his architect Heinrich Schickhardt build a new settlement in the inhospitable forest on the eastern edge of the northern Black Forest, which was given the name “Freudenstadt”(“City of Joy”) (Fig. 5). On the mountainous Swabian Alb, where the soil was too poor for growing grain, hemp and flax of the finest quality were grown and woven into linen in Urach. The Urach linen-weaving mill existed for around 200 years, and its products were in great demand in Milan, Genoa and Venice.

The Thirty Years’ War was a catastrophic time for the small duchy of Württemberg. Hardly any other part of the empire suffered so much during the war as Württemberg, which had been occupied almost continuously by foreign troops since 1628 and was the scene of numerous battles. In addition, the duchy lost about a third of its territory in 1629 as a result of the restitution edict of Emperor Ferdinand II, which ordered the return of the Catholic property confiscated by Duke Ulrich I. When Duke Eberhard III (1633 – 1674) returned from exile, he

the restitution meant the restoration of the duchy to its 1624 borders. The Duke now used mercantilist means to try to revive the economy of his country and to restore order. The Protestant church and school system and the University of Tübingen in particular owed their renewal to him.

With Duke Friedrich Karl (Fig. 7), Württemberg had its first baroque ruler. He ruled as a guardian from 1677 to 1693 on behalf of the son of Duke Eberhard III, Crown Prince Eberhard Ludwig, who was one year old upon succeeding his father. The administrator, who had been educated at several European universities and was keen on education, was particularly concerned with the school and church systems and founded the first Stuttgart grammar school, the “Great Pedagogium”.

found Württemberg in a desolate condition: The country had been depopulated by plague and famine. Of the estimated four hundred thousand inhabitants, only sixty thousand had survived the horrors of war. Furthermore, 6,000 Württemberg soldiers had fallen in the Battle of Nördlingen in 1635 as allies of the Swedes. The state was in the grip of bitter poverty; daily life, and in particular the economy and culture of the country, remained bleak and disorderly for many decades. The Duke’s main concern was to assert his sovereign rights over the Emperor and to persuade him to withdraw the restitution of church property, which had been a condition of the Duke’s return. However, he was unsuccessful in this for many years, as Ferdinand II had added the duchy to his own estate (Fig. 6). It was only through the skilful negotiations of his adviser Varnbüler in the Peace of Westphalia, with the support of Sweden, France, and the Protestant imperial estates, that an agreement was reached in the Duke’s favour. For Württemberg,

In order to improve his finances, Friedrich Karl turned to a small “trade” in soldiers, for which he had to obtain loans from South German banks. He then sold his numerically insignificant regiments to Venice, Holland and Vienna. However, his greatest personal adventure was his capture by French officers during the Palatinate War of Succession in 1692. He was taken to Versailles, treated very politely by King Louis XIV, and soon released again. The courtesy shown to the Duke-Administrator by Louis XIV during his brief captivity made him very suspect in the eyes of Emperor Leopold I. The Emperor deposed him in 1693 and, when Friedrich Karl begged for permission to remain in office, is said to have replied laconically: “Too late!” Friedrich Karl was eventually appointed Generalfeldmarschall, an honourable but militarily insignificant title.

Margret

Nollé

FRID • CAROL • D • G • D • - WIRTEMB • ADMINIST • Armoured bust right with lace jabot, below the signature M (die-cutter Johann Christoph Müller)// 16 • D • P • F • 81 • Crowned, four-field coat of arms (Württemberg, Teck/imperial storm flag, Mömpelgard), laurel wreath around.

Estimate: 10,000 euros

Fig. 5: Reverse of a Freudenstadt gift thaler from 1627 with a bird’s-eye view of Freudenstadt. Freudenstadt City Archive.

Fig. 7: Auction 411, Lot 892, Frederick Charles, 1677-1693. 1/2 Reichstaler 1681, Stuttgart. 14.58 g.

Fig. 6: Topographical map of the Duchy of Württemberg from around 1619 by the Ghent engraver Pieter van Keere (1571 – c. 1646) from his atlas “Germania Inferior id est Provinciarum XVII”.

1,5:1

Wolfgang Steguweit Was Awarded the Cross of the German Order of Merit

On 11 May 2024, Wolfgang Steguweit received the Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. The German President thus honored a numismatist who is not only very popular in his own country, but also internationally known for his commitment at FIDEM. We are very happy for Wolfgang Steguweit and would like to congratulate him.

We have published Wolfgang Steguweit’s memoirs in 2024 (in German), because we do not want people to forget what life was like for a scholar in the GDR, and what great things were achieved by numismatists after German reunification to get coins back into the collections where they belong. While supplies last, you can order Wolfgang Steguweit’s memoirs (in German) from our customer service. We used the work as a source for this brief overview of Wolfgang Steguweit’s life.

Wolfgang Steguweit was born in late August 1944. After fleeing from Königsberg, now Kaliningrad in Russia, he ended up in what later became the German Democratic Republic. This almost prevented Wolfgang Steguweit from becoming a numismatist in the first place. Although he was interested in art history and coins from an early age, he was not accepted to study this field at university. After an apprenticeship as a technical draughtsman, someone suggested that he study to become a teacher specializing in art education. He thought this detour might lead to working in a museum one day. And, indeed, he was offered a place at the university in 1963.

In his very first semester, however, Wolfgang Steguweit incurred the displeasure of the regime. He refused to become an informer for the Ministry for State Security (Stasi). In doing so, he made himself a potential suspect. When he was allowed to look at his 1000-page Stasi file after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Wolfgang Steguweit found out that up to ten informers had been assigned to spy on him.

Of course, there were consequences. Instead of being able to give up his unloved job as a teacher after two years, as was customary, he had to continue in this position for a full four years, even though he had already secured a job at a museum before graduating. He had heard that the coin cabinet of the Castle Museum in Gotha was looking for a numismatist – a dream come true for any coin enthusiast. So 23-year-old Wolfgang Steguweit hitchhiked to Gotha and convinced the museum’s director that he was the right man for the job. She kept the position open for him for four years, until, in the summer of 1971, he received official permission to go to Gotha. In Gotha, he should have enjoyed the right to affordable

housing. But in the real-life socialism of 1971, there were no available apartments in Gotha. Wolfgang Steguweit threatened to camp out on the market square if the authorities did not give him housing. And indeed, they found something: a room in the attic of Gotha’s castle.

By modern standards, his living and working conditions were unimaginable. In winter, it was just as cold in the office in the morning as it was outside. The stove in the tiny room provided heat, but when the wind was bad it produced so much smoke that Wolfgang Steguweit could hardly see the coins on his table. Nevertheless, he organized his first exhibition in the very first year. It would be one of many.

Wolfgang Steguweit was stubborn, dedicated and incredibly hardworking. He managed to get the museum’s carpenter to build coin cabinets, had the janitor give him an extra room for the coin collection, and turned Gotha into a national center for numismatics. He processed the coin finds of the archaeological services and also curated the Weimar coin collection of about 15,000 pieces. As a result, Wolfgang Steguweit was allowed to hire a second numismatist, a typist and a conservator specializing in metals.

One thing he was not allowed to do, however, was to travel to the West, even though he was repeatedly invited to do so. After all, he made sure that foreign numismatists took advantage of Gotha’s coin collection for their academic work. Those who came to Gotha had to give a lecture there, which is why Wolfgang Steguweit was always in contact with foreign scholars. He was to discover later that all these visits were closely monitored and his superiors were always informed immediately.

It was not until 1986, when Michel Hebecker became the new director in Gotha, that Wolfgang Steguweit was allowed to make his first trip to West Germany in 1987. Shortly thereafter, he was appointed director of the Berlin Numismatic Collection. He was thus in the right place to sift through the numismatic holdings and to secure the most important treasures for public collections when the GDR’s state-owned foreign currency company called ‘KoKo’ was liquidated. Thanks to Wolfgang Steguweit, 1,500 rarities are now part of museum collections. As the numismatist was perfectly familiar with the criminal activities of KoKo, he made sure that all the pieces were cataloged in such a way that they could be returned to their rightful owners at any time in the event of legitimate claims.

One project in particular brought Wolfgang Steguweit and our auction house together. In 2007, he learned that several heavy boxed containing

the entire collection of ancient coins of Gotha and the top pieces of the early modern collection had turned up in Coburg. They had been taken to safety before the war under unclear circumstances. After tough negotiations, Wolfgang Steguweit was able to persuade Coburg to return the coins – for a higher sum, but still far below the market value of the coins. He asked us for help. The founder of Künker, Fritz Rudolf Künker, and one of our most loyal customers, Friedrich Popken, who sadly passed away recently, stepped in to provide initial funding. The rest came from the State of Thuringia and the Cultural Foundation of the German Federal States. The Ernst von Siemens Art Foundation made sure the acquisition would take place through long-term pre-financing.

There is much more to say about Wolfgang Steguweit: Of his decision to resign as director of the Berlin numismatic collection in 1992 in order to fulfill his duties as deputy director until his retirement in 2009. Of his love of medals, his countless academic publications, of the founding of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Medaillenkunst (German Society for Medallic Art) and the publication series “Die Kunstmedaille der Gegenwart in Deutschland” (The contemporary art medal in Germany).

But how do you sum up a life lived for numismatics? For sure, the Cross of the Order of Merit is definitely well deserved.

Wolfgang Steguweit received Germany’s Federal Cross of Merit for his numismatic achievements. Photo: Thüringer Staatskanzlei / Jacob Schröter.

Detail of the 1713 medal by Nikolaus Seeländer commemorating the foundation of the Gotha coin cabinet, which can now be seen in Gotha thanks to Wolfgang Steguweit. Photo: KW.

A magnificent collection of Dutch coins:

From

the beginnings to 1795

Dutch history

Most Germans, and almost all of their other neighbours, know far too little about the history of the Netherlands. The Dutch, who live in a country that is quite small in terms of area, have managed to leave a clear mark on history with their hard work and skill, and were the economic centre of Europe – or, indeed, of the world at that time -- for quite a long period. This economic prosperity went hand in hand with great cultural achievements. The period is rightly referred to as the “Golden Age of the Netherlands” (De Goude Eeuw). It is well worth reading one of the books by the eminent Dutch cultural historian Johan Huizinga (1872-1945) about this period: “Holländische

Kultur des siebzehnten Jahrhunderts” (Dutch Culture in the Seventeenth Century) has been published in a German translation by the Munich-based Beck publishing house and is available at a low price. We are delighted to be able to make our neighbouring country better known by auctioning the second part of a magnificent collection of Dutch coins. Margret Nollé (history) and Manuela Weiss (numismatics) have cooperated to produce a numismatically- and historically informative catalogue that brings the history of the Netherlands, from its beginnings to the transition to the Batavian Republic, to life before our eyes, using beautiful and often extremely rare coins. Kampen at the mouth of the Ijssel

One of the extremely rare pieces in this collection – the triple rose obol of Kampen – is worth a closer look (Fig. 1). Kampen (Fig. 2), situated at the mouth of the river Ijssel, had developed into one of the most important cities in the

Fig. 1: Auction 414, Lot 5055. Kampen. Double rose obol, no date (1600).

of a sovereign of Queen Elizabeth I of England.

5-6 known. Excellent.

Fig. 2: Willem & Joan Blaeu, 1652, view of Kampen.

from Psalms was commented on by several Church fathers (for example by Jerome, the translator of the Bible into Latin, in his letter to Eustochius, 22, 32) and also appears frequently on coins. The coin featuring Elizabeth I does not bear the coat of arms of the English queen, but rather the city arms of Kampen, which depict a castle.

Netherlands from the High Middle Ages to the early modern period. The Ijssel side of the city still reflects the former heyday of Kampen: Towers, gates, churches, and magnificent merchant establishments catch the eye (Fig. 3). The city with its great history is unfortunately a far too little-known jewel of the Netherlands.

Kampen’s rise was already well advanced when, around 1230, the Bishop of Utrecht granted the settlement -- which had become increasingly important -- the status of a city. The people of Kampen had the qualities that still characterise the Dutch today: tenacity, daring, coupled with a sense of what is feasible. In short, they had a good sense of business. Around 1300, Kampen was involved in Baltic Sea trade like no other Dutch city. Merchants from the city bought herring, butter, meat, grain, hides and furs, wood and wood products (pitch, tar) in the Baltic region and in return supplied salt, wine, fabrics, and steel in particular. The Ijssel, which is connected to the Rhine (Fig. 4), enabled the people of Kampen to sell their goods deep into the interior of Germany and to make enormous profits from this intermediate trade. Around 1410, Kampen had 120 ships involved in long-distance trade; the city probably had a population of around 13,000. Merchants from Kampen were also heavily involved in trade with France, Spain, Portugal, and England. In addition, the people of Kampen had a flourishing textile industry. Kampen was also known for its master belland cannon casters. The most famous bell founder of the early modern period, Geert Wou van Kampen (1440-1527), lived in the city beginning in 1482 and became very wealthy. 129 of his bells can still be found in Central and Northern Europe. They continue to be heard today in Osnabrück, Lüneburg, Erfurt, and many other cities.

Kampen reached the height of its prosperity in the 15th century. It had joined the Hanseatic League in 1441, but the people of Kampen were more interested in their own affairs than in the aims of the Hanseatic League, which led to repeated conflicts. Kampen’s membership in the Hanseatic League, which was in decline, had brought few advantages. In the 16th century, Kampen’s Baltic Sea trade declined. Poland and Russia gained increasing influence over the local trading activities in the region and made life difficult for the Kampen merchants. The “discovery” of America shifted trade away from Kampen: The Dutch cities that were located directly on the coast had an advantage over Kampen, which could only be reached via the Zuiderzee. In addition, the mouth of the Ijssel was increasingly silting up, making shipping more and more difficult for the people of Kampen.

The decline of Kampen continued until the 1590s, when an unprecedented exodus of Huguenots from France, Jews from Spain, and Protestants from the Habsburg Netherlands greatly augmented the population of the rebellious Netherlands. New techniques and a committed entrepreneurial spirit came to the Netherlands with these refugees. The Golden Age was ushered in.

The triple rose noble

It was during this period – around 1600 – that the triple rose noble was minted, which will be offered in our Auction 414 as Lot 5055. This is the second multiple rose noble to be offered by our company in recent times. In Auction 362 (Salton Collection), a multiple of eight rose nobles weighing 60.95 g was offered as Lot 1280. It was estimated at 250,000 euros and was knocked down at 700,000 euros after a bidding war. Connoisseurs among collectors know that you often get the chance to acquire such rarities only once in a lifetime, and they have their price.

The triple (?) rose noble without a date – probably minted around 1600 – weighs 20.44 g. For a triple rose noble, which should weigh about 23 g, it is underweight. This is due to its role as a gift coin. A contract of employment for the Kampen mint master Hendrik Wijntgens (1589-1611) has been preserved. In it, Wijntgens is commissioned to produce gold award medals in the form of multiple rose nobles or gold sovereigns weighing between 13 and 61 g. Such award coins or medals, which could be awarded like (or instead of) medals, often did not meet the nominal weight. This can also be observed in the Braunschweig-Lüneburgian ducats of Duke Julius, which were minted around the same time. Whether this was an oversight or a case of embezzlement at the mint cannot be determined today. The award medals, which were produced in various denominations, are so rare that Purmer’s catalogue (Handboek van de Nederlandse Provinciale Muntslag 1568-1795, Deel II, 2009) only lists one double rose noble, while higher denominations are completely absent.

The reverse of the triple rose noble also shows the English Queen Elizabeth I on the throne, with sceptre and orb in front view. Since the coin very emphatically focuses on the ruler, it could also be justifiably described as a sovereign, i.e. a coin with the image of the sovereign. The inscription on the obverse quotes Psalm 37, Verse 25: NON VIDI IVSTVM DERE(lictum) N-EC SEMEN EI(us) QVÆ(rere) PANEM/I have never seen the righteous abandoned, nor his children begging for bread. This verse

The obverse shows the double Tudor rose, consisting of an outer red- and an inner white rose, as Elizabeth I was of the House of Tudor. The rose is double because it combines the coats of arms of the House of York (white/silver rose on the inside) and the House of Lancaster (red rose on the outside). By marrying Elizabeth of York, Henry VII (Tudor) was able to finally end the Wars of the Roses (1455-1485), which had been waged for decades, in January 1486. Around the double rose is the inscription MONETA AVREA IMPERIALIS CIVITATIS CAMPENSIS/ gold coin of the imperial city of Kampen. In the centre of the rose is the quartered Spanish coat of arms: Fields 1 and 4 show the coats of arms of Castile (castle) and León (lion), fields 2 and 3 the coat of arms of Aragon (poles; normally there are only 4, without a crossbar). Fields 1 and 4 are again quartered and show the coat of arms of Castile (castle) in fields 1 and 4, and the coat of arms of León (lion) in fields 2 and 3.

English coins (nobles and sovereigns) were a popular international means of payment since England had become a great power under Elizabeth I, and were often imitated, especially in the Netherlands and Denmark. In the case of the ‘award’ coins, however, it is unlikely that the fact that English money was readily accepted in international trade played any major role. What seems to have been much more important is that Elizabeth I supported the freedom movement of the General States -- and sent Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, to the Netherlands from 1585 to 1587 to reinforce the rebellious Dutch. Although there were disputes between Dudley and the Dutch, Queen Elizabeth was popular with the English. In the difficult times in which this coin was minted, Kampen may well have used such pieces for awards, and presumably also for bribes. However, many of the higher denominations would soon have been melted down again, so it is a stroke of luck that such pieces have survived to this day, to give us a glimpse into the birth of the free Netherlands.

Johannes Nollé

Fig. 3: View of Kampen with the Ijssel and the city bridge over it. (Wikipedia, Michielverbeek)

Fig. 4: The Ijssel, the connection between the Rhine and the Zuiderzee. (Wikipedia, Weetwat)

Who Was Frederick the Wise?

We think we know him: Frederick the Wise who hid Luther at Wartburg Castle. In fact, his myth was only created after the ruler’s death. Numismatically speaking, the German Empire immortalized him.

III the

Annaberg or Wittenberg. Very rare. Very fine. Estimate: 20,000 euros. Hammer price: 75,000 euros. From auction 358 (26 January 2022), No. 182. The obverse shows a portrait of young Frederick the Wise, the reverse the portraits of the Saxon rulers who competed with him for power.

A Difficult Starting Position

On 17 January 1463, Frederick III, who became known as “the Wise” after his death, was born as the eldest son of Elector Ernest of Saxony. After Ernest’s death on 26 August 1486, Frederick took over the rule – not alone. He shared it with his youngest brother John, who resided in Weimar. Another player in this game was his uncle, Albert the Bold. Even though the latter had agreed to the Partition of Leipzig one year earlier – a treaty that determined the division of the Ernestine and Albertine branches – nobody could say at that point whether Albert would honor this arrangement or not. Thus, Frederick III had to be careful. But this came naturally to him as he was a careful person anyway.

His hesitation caused numerous political defeats. First, he failed to incorporate Erfurt into his territory. Then he failed to retain the guardianship of the minor Hessian landgrave. Not to mention the fact that, after the death of his two brothers, his family was unable to maintain control of the bishoprics of Magdeburg, Halberstadt and Mainz.

And then there was his greatest defeat, which came about because he did not even dare to take up the fight for the imperial crown because of a rebellious Augustinian monk, even though Frederick would have stood a good chance against the other candidates – Francis I of France, Henry VIII of England and the Habsburg Charles I of Spain. He was a German prince, had a voice in the Electoral College and was by far the least powerful of the four candidates, a quality that electors greatly appreciated in emperors. In addition, Frederick owned part of the silver mines of the Ore Mountains and had thus enough resources to come up with the necessary bribes. But history would have taken a different path if Frederick had ventured to take this step. That is why posterity calls him “wise”; his contemporaries probably used other adjectives.

Frederick and Luther

But let us go back in time to understand why Frederick did not throw his hat in the ring. On 18 October 1502, he founded a university in his residential city of Wittenberg. One of those who taught at the university of Wittenberg was the Augustinian monk Martin Luther. Things were getting rather hot for him in 1518.

The Pope initiated legal action against him, which jeopardized the reputation of Frederick III and his university. First, Frederick III made an effort to crush the legal proceedings, even though he did not share Luther’s views.

We know that Frederick was pious, made pilgrimages to Jerusalem and had assembled a gigantic collection of relics. But it did not work out. His next idea was to ask Cardinal Cajetan in December 1518 to let Luther publicly discuss his theses.

Emperor Maximilian I died as early as one month later. A new emperor had to be elected. The issue of Luther had destroyed Frederick’s chances as a candidate. He had proven to all of Germany that he could not even keep his university in order. The result: Charles I of Spain was elected emperor Charles V on 28 June 1519 and Luther was given the chance to defend his theses in Worms. We know how the story ended. Luther was placed under the imperial ban. Frederick tried to limit the damage by negotiating a deal that established that the imperial ban would not be enforced in Saxon territory.

Luther’s Saxon followers thus thought they were given carte blanche. As early as in May 1521, the first priests married. In January 1522, the Wittenberg Council – not the Saxon Duke! –adopted a new (Protestant) church order. Frederick outlawed it within the same month. But events had taken on a life of their own: In March, Luther returned to Wittenberg. Thus, Frederick lost what influence he had on what was happening. At some point, he probably had no choice but to put a brave face on it and to accept the Reformation. Frederick died on 5 May 1525. Protestant sources claim that he converted to Luther’s Protestantism on his deathbed.

Marketing the Reformation

His death thus paved the way for turning Frederick the Wise into an icon of Protestantism. One of the best-known artists of the time helped in this endeavor: Lucas Cranach. He had set up a workshop and established a way of producing his works quickly and cheaply by distributing different tasks between him and his assistants.

The portrait of the elderly duke became an iconic image. He is depicted with white sideburns and a black, velvet beret. Numerous pictures of him are on display in art collections today because Frederick’s successors systematically distributed his portrait to all important princes, mostly together with their own portrait. Thus, once the Reformation had become acceptable, the princes made sure to benefit from the glory of being the successor of Luther’s (involuntary?) patron.

A contemporary source tells us about the incredible volume in which these portraits were produced: On 10 May 1533, Duke John paid the painter Lucas Cranach 109 guldens and 14 kreuzers for creating 60 small pictures of Frederick and 60 small pictures of him.

Most of them came with a legend that explains how John wanted his brother’s fate to be interpreted. The poem, written by Luther himself, states that Frederick had kept the peace in the empire by means of reason, patience and good fortune as he faithfully elected the emperor without putting himself first. He – Frederick – founded the university in Wittenberg, where God’s word emerged (this is how Luther liked to speak about himself; author’s note), with the help of which the papal power was overthrown and the right faith restored.

100,000 euros.

From Künker auction 413 (25/26 September 2024), No. 2823.

The Myth of Frederick in the 19th Century

Luther’s followers continued to act as skillful propagandists until well into the 20th century. So let us take a large step forward in time, right to the First World War when 31 October 1917 marked the 400-year anniversary of the day when Luther nailed his theses to the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church. It had become customary to celebrate large feasts on the occasion of such centenaries, and to issue commemorative

Frederick the Wise, painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder and his workshop. Portrait after 1525 with tablet written by Luther.

Portrait of young Frederick the Wise, painted by Albrecht Dürer, 1496.

Frederick

Wise, Albert the Bold and John the Steadfast. First klappmützentaler n.d., minted in

German Empire. 3 marks “Frederick the Wise”. Proof. Estimate:

coins in the context. In fact, the most important representatives of Protestant churches in Germany and abroad had been planning in early spring 1914 to hold international celebrations of Lutheranism in Wittenberg. Representatives of numerous European countries, the U.S., Canada and Austria had agreed to come.

But then the First World War broke out. In Germany, Lutheranism lost its international element and people once again turned to Luther as a national phenomenon. They resorted to the image of Luther portrayed by the SaxonPrussian historian Heinrich von Treitschke. The latter had claimed that Luther had merely anticipated German unification. And von Treitschke considered Bismarck to be Luther’s congenial successor. Therefore, only Germans could truly understand Luther as Luther was the personification of the soul of the German people.

But was he really? And did he also embody the soul of southern Germany, a mostly catholic area that had suffered under Bismarck’s policies of the Cultural Struggle? 1,800 Catholic priests were arrested, and church property worth 16 million gold marks was confiscated under Bismarck. At that time, in the spirit of the Enlightenment, the Protestant majority declared the Catholic minority Reichsfeinde, enemies of the Reich. Bismarck was fond of using this term, which he later applied to socialists and the Polish. The Nazis would pick up on this politically charged insult in their anti-Jewish propaganda. In other words: in the early 20th century, the figure of Luther served more to divide Germany than to unite it. And no one could afford to divide the country in the middle of the First World War. The Saxon Wettins, who had long returned to Catholicism (after all, it had secured them Poland for two generations), were not exactly pleased about the idea to put a portrait of Luther on Saxon coins. They therefore supported the decision of the Reich Treasury (Reichsschatzamt) and the Federal Council to reject the motif. Their reasoning was officially based on an objective argument: only members of the ruling princely houses could be depicted on the obverse of coins of the German Empire.

Therefore, a new motif was needed. And Frederick the Wise was a perfect choice as he had been stylized as Luther’s protector by the Reformation. In this way, Luther was implicitly included in the image without being depicted himself and, above all, without causing controversy in Catholic circles.

The chief engraver of the mint in Muldenhütten, Friedrich Wilhelm Hörnlein, was commissioned to design the coin. He was inspired by the iconic portrait of Frederick the Wise from the workshop of Lucas Cranach and created one of the most beautiful portraits in the coinage of the German Empire. By the way, the circumscription “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott” (A Mighty Fortress Is Our God) reminded contemporaries not only of the hymn composed by Luther. While this song was still kind of an unofficial Protestant anthem in the 18th century, it had firmly established itself as a national battle song during the German campaigns of the early 19th century. The students of the Wartburg Festival of 1817 had sung it, and many others who advocated national ideas had followed their example. During the First World War, the national interpretation of the song reached a climax when countless military and civil postcards with motifs of war featured this verse as a motto.

Originally, the coins featuring “Frederick the Wise” were supposed to have a mintage figure of 350,000 specimens. But in the middle of the First World War, silver was needed for other purposes. Only a symbolic number of 100 pieces were produced. 30 specimens were held back by the Saxon minister of finance. Other pieces were added to coin collections in ways that we can no longer trace today. The rest was melted down again during the 1918 revolution.

Thus, “Frederick the Wise” became the most beautiful, rarest, most popular and therefore most expensive coin of the German Empire.

A Spectacular Collection of German Coins Minted After 1871

Therefore, the quality of a collection of coins from the German Empire is (unfortunately) often measured by the fact of whether it contains a “Frederick the Wise” or not. But there are so many other magnificent issues in the field of German coins minted after 1871. You can acquire most of them in extraordinary condition in the upcoming auction 413 – even we at Künker rarely have the opportunity to present such an extensive offer of such exquisite quality.

Here you can find a few other spectacular coins from auction 413. But this is only the tip of the iceberg. So do not miss out on carefully studying the catalog if you are interested in German coins minted after 1871!

Dr. Ursula Kampmann

Lot 2524: Baden. 5 marks, 1875. Extremely rare in this quality. Proof. Estimate: 15,000 euros

Lot 2600: Bavaria. 1918 commemorative coin in the size of a 3-mark piece, iron, commemorating the kings’s visit to the mint. Very rare. Almost mint state. Estimate: 7,500 euros

Lot 2602: Bavaria. 3 marks, 1918. Commemorating the golden wedding jubilee of the royal Bavarian couple. Very rare. Matte. Proof. Estimate: 30,000 euros

Lot 2635: Hamburg. 5 marks, 1896. Rare year. About FDC. Estimate: 1,500 euros

Bibliography: Wolfgang Flügel, Konfession und Jubiläum. Zur Institutionalisierung der lutherischen Gedenkkultur in Sachsen 1617-1830. Leipzig (2005) Armin Kohnle und Uwe Schirmer (ed.), Kurfürst Friedrich der Weise von Sachsen –Politik, Kultur und Reformation. Leipzig (2015)

Lot 2651: Hesse. 5 marks, 1888. Rare, especially in this quality. Proof, min. touched.

Estimate: 5,000 euros

Lot 2834: Saxe, Coburg and Gotha. 2 marks, 1911. Extremely rare, especially in this quality.

Only 100 specimens minted. First strike, about FDC.

Estimate: 10,000 euros

Lot 3129: Mecklenburg-Schwerin. 10 marks, 1878. Very rare in this quality. FDC.

Estimate: 4,000 euros

Lot 3142. Mecklenburg-Strelitz. 20 marks, 1873.

Very rare, especially in this quality. About FDC.

Estimate: 15,000 euros

Lot 3148. Mecklenburg-Strelitz. 20 marks, 1905. Very rare. Proof. Estimate: 12,500 euros

Lot 3187. Prussia. 10 marks, 1889 A. Very rare, especially in this quality. About FDC.

Estimate: 10,000 euros

Lot 3220. Reuss, elder line. 20 marks, 1875. Very rare, especially in this quality. Extremely fine to FDC. Estimate: 35,000 euros

Lot 3288. Saxe-Meiningen. 20 marks, 1872. Very rare. About FDC.

Estimate: 25,000 euros

Lot 3429: Weimar. 5 reichsmarks, 1933 J. Eichbaum. Very rare. Proof.

Estimate: 10,000 euros

Künker as a Supporter of the First Evento Numismático in Madrid

On 28 and 29 June 2024, the first Evento Numismático Internacional was held, creating a new meeting place for the Spanish-speaking numismatic community.

Until recently, there had been no major international coin show in Spain. And this is quite surprising. After all, Spanish numismatics has not only a diverse community of collectors and dealers, but also an extremely active mint that is interested in classical numismatics. Given the sheer amount of public coin collections in Spain and the country’s numerous curators and scholars of international renown, one might well wonder why this active scene had been lacking a meeting place.

Jesús Vico, Agustín “Augi” García of Daniel Frank Sedwick LLC and Luis Domingo wanted to change that. They created an event for aficionados of Spanish numismatics. And this event is completely different from anything we knew before.

The Evento Numismático in Madrid is a synthesis of many different forms of numismatic gatherings. At its heart is a coin show – because nothing gives coin collectors more pleasure than hunting for something new to add to their collection. And the easiest way to finance such events is through table fees paid by coin dealers. The coin show is accompanied by a congress, for which the organizers collaborated with the best-known Spanish scholars. Dr. Alberto J. Canto Garcia, Dr. José María de Francisco Olmos, Pere Pau Ripollés and Martín

Almagro Gorbea were just some of the speakers who presented their latest research findings. In addition, the organizers held a high-profile roundtable discussion in which representatives of customs, police and tax authorities discussed with coin collectors and dealers how to effectively protect cultural property.

The international session was organized by CoinsWeekly. Andrew Brown, National Finds Advisor with the British Portable Antiquity Schemes, Ursula Kampmann of CoinsWeekly and Klaus Vondrovec of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna discussed past and present forms of collaboration between the academic world, laypeople, the coin trade and collectors.

However, the coin show and the conference sessions were just one part of the event. The main focus of the Evento Numismático was on networking. Therefore, there were plenty of opportunities to talk to each other and to connect with people from other countries and professions.

On the first evening, the Spanish Mint organized a reception at its in-house museum, which we recently presented in our Exklusiv. The second exhibitor evening was held at the Prado. And there was an excursion to the Segovia Mint for all those

who wished to participate. Glen Murray himself took the opportunity to guide the 50 or so visitors through the extensive grounds.

The first Evento Numismático in Madrid was a great success, and we at Künker are delighted about this. After all, we have supported the organizers as a sponsor from the very beginning. As an international auction house, it is very important to us that there are well-attended meeting places in important markets. That is the only way for us to meet new customers on site. That is why we attach great importance to supporting the initiatives of other coin dealers. And when they come up with a concept as innovative as that of Jesús Vico, Agustín “Augi” García and Luis Domingo, it is an even greater pleasure for us.

By the way, there will be a second Evento Numismático. If you are interested in Spanish coins and the issues of the Spanishspeaking world, mark your calendars for 25 to 28 June 2025!

Petr Kovaljov, our representative in Brno, Czech Republic, also came to the Evento. Here you can see him at the CoinsWeekly booth with Ursula Kampmann. Photo: MM.

Organizers and sponsors of the first Evento Numismático in Madrid. Photo: INM.

A view into the event hall of the Evento Numismático in Madrid. Photo: UK.

Fabian Halbich represented our team at the first Evento Numismático in Madrid. Photo: UK.

The Regina Adams Collection: an excellent collection of Lösers

Regina Adams has been collecting Lösers for almost a quarter of a century – even though the American state of Massachusetts, so far away from the places where the Lösers were minted, is now her home. Two things have always connected Regina Adams with these very special coins: First, she was born in Celle, one of the ducal residences of the Dukes of Braunschweig and Lüneburg; and additionally, she is a gifted professional photographer with a trained eye for aesthetics and beautiful things. After all, her husband, John Adams, is a passionate coin collector. The birthday present of a Löser for his wife in 2000 became the starting point for a collection of 31 Lösers, mostly in excellent condition. The Adams couple has now decided to dissolve the collection and sell it at our autumn Auction 412. We have always supported the collecting activities of Regina and John Adams over the years, and are now proud

Lot 1544: Braunschweig and Lüneburg.

August the Younger, 1635-1666.

Löser for 5 Reichstaler 1638, Zellerfeld, on the imperial confirmation of the succession.

Of the utmost rarity. Cabinet piece.

Expressive patina, sharply defined, excellent mint gloss.

Estimate: 40,000 euros

Coins are particularly impactful through their images, which is why Prof. Nollé has gone into some important aspects in more detail: The coats of arms, which very often adorn the reverse sides of the coins and are composed of many individual smaller coats of arms, are particularly important. They provide precise information about the territories belonging to the dukes.

The dukes depicted on the obverse sides of the coins often appear on horseback. This alludes in part to the symbolic horse of the Welfs, which ultimately goes back to the worship of white horses by the Germanic peoples, as recorded by Tacitus. Another tradition emerged during the Italian Renaissance. Based on the ancient equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, equestrian statues of generals and rulers became fashionable during this period. The horse was identified by Renaissance scholars, particularly those who studied the theory of the state, with the people of the state, who were to be steered in the right direction by a wise and loving ruler, as in the case of a horse being trained. French influence can be seen in the fact that rulers of Braunschweig-Lüneburg had themselves portrayed with an allonge wig, modelled on that of the “Sun King”.

Short biographies provide us with a closer insight into the individual rulers depicted on the Lösers. Numerous coins refer to August the Younger, who turned his court in Wolfenbüttel into a cultural centre of his time and founded the Wolfenbüttel Library, which is still famous today. Coin collectors, numismatists and history enthusiasts will find it worthwhile to take a closer look at our Catalogue 412.

Wolfenbüttel Castle served the dukes of Braunschweig-Lüneburg as their residence from 1283 to 1754.

You can download the English-language brochure “The Welfs’ Splendour in Historic Coins –The Regina Adams Collection at Künker” as a PDF here.

Numismatic Museums Around the World: The Segovia Mint

The train ride from Madrid to Segovia takes just 26 minutes. And Segovia is home to one of the most important sights of numismatic Spain: the Segovia Mint, which has been transformed into a museum and allows visitors to understand how coins were made in early modern times.

Looking at this coin, you will immediately notice a number of characteristics: First of all, the coin was struck with the utmost precision – even the smallest details of the coats of arms are clearly visible, even though the coin weighs a mere 170 grams! An enormous amount of pressure must have been applied to strike such a large surface with this level of precision! Then there is the missing piece on the left edge, the result of a clipped planchet. These two things indicate that this coin was not struck by hand, but created with the latest minting technology of the time: a roller press.

The design reveals where the issue was minted. In the left field, it shows a small section of a two-story aqueduct, reminiscent of the great Roman aqueduct preserved in the center of Segovia. The ruins of the former mint that produced this representative coin have also survived. They were neglected and abandoned for many years, until an American numismatist saw them, recognized their importance, and decided to

devote himself to restoring this cultural heritage. Glen Murray succeeded. Where there were crumbling ruins two decades ago, there is now a museum where you can learn how coins were made in the 17th century. And the Segovia Mint is not just a single minting room, but an entire complex of buildings where everything is geared to roller press minting.

A Numismatic Revolution

At the beginning of the early modern period, European trade multiplied, resulting in an increased demand for heavy silver coins, i.e., talers. Traditional hand striking reached its limits. An innovative mind in Zurich therefore developed a method that would become the new standard in the industry.

Let us go back to 1554. During the Reformation, Zurich had confiscated church property that generated a surplus. And the Council of Zurich wanted to turn that surplus into coins. This required the minting of an average of 10,000 pounds of account per year. The 984,772 talers, 60 million groschen and 2.6 million fractional coins produced over six years by the St. Gallen mint master Hans Gutenson, who had been specifically hired for this task, and his 58 journeymen were not nearly enough. Council member and goldsmith Jakob Stampfer therefore developed a completely new minting machine: the roller press.

A roller press is basically a water-driven roller that can be used to roll a sheet of metal to any desired thickness. Jakob Stampfer had the idea of transforming the previously smooth rollers into coining rollers by engraving them so that they became the equivalent of upper and lower die. The rollers pressed the motif onto a sheet of metal that was fed through them. Traditionally, planchets were punched from these metal sheets after the rolling process. The innovation was that instead of punching planchets out of the metal that would later be struck into coins, the roller press produced a sheet of metal from which ready-made coins could be punched. If the metal was too short to produce a completely circular coin, this resulted in a phenomenon that is described as “clipped planchet” or “edge clip” in catalogs.

Jakob Vogler brought the roller press from Zurich to Hall. He was the last member of a group that had to tried to make money with this new minting technique. But neither the inventor of the roller press nor Jakob Vogler became rich as a result. It was the Tyrolean archdukes who became rich thanks to the invention of the roller press because they saved a lot of money as the new way of minting required much less skilled labor than hammer coining. However, roller press minting was only profitable in cases of mass production. This was the case in Hall, as silver from the Schwaz mine was minted into coins there, resulting in a mass production of talers.

When the Spanish Habsburgs were looking for a way to mint the silver from the New World in a cheap, quick and precise way, they asked their Austrian counterparts in Hall. The result was a transfer of technology. Six journeymen from Hall traveled to Spain to set up the new mint. For this purpose, they first had to find a suitable location. After all, roller presses depended on water power. And while Tyrol had plenty of fast-flowing streams, water was in short supply in Spain.

In 1583 Segovia was chosen as the site for the new mint. There was already an old paper mill that used the water of the Rio Eresma. It was here that the royal architect, Juan de Herrera, built the mint. Juan de Herrera is better known for El Escorial, which was built according to his plans and under his supervision. The fact that this important artist was commissioned to design the mint shows how much importance King Felipe II attached to the project.

In 1585, two roller presses arrived from Tyrol packed in boxes. They had to be reassembled before regular minting could begin in 1586. By the way, the first 100 coins created with the new roller presses were distributed to the city’s poor by royal decree.

A Tour of the Segovia Mint

But it would be wrong to assume that the museum is only focused on the minting process itself. Rather, the mint is a large complex that was specifically designed to transform the silver, copper, and gold it received into coins as efficiently as possible. By the way, it was not only the state silver of the Spanish treasure fleet that was coined here. Private individuals also turned to the mint to have raw metal minted into easily convertible coins for a fee.

The first thing every visitor sees is the large entrance gate (1). In the 16th century, this was the only entrance to the secure area, which was surrounded by high walls. To the left of the entrance was the guardhouse, which was manned day and night. This prevented unauthorized persons from entering the mint. If worst came to worst, the guard could use the jail right next to the guardhouse. Caught offenders could be imprisoned there (2).

Incoming goods were transported through the gate into the large complex of buildings on the right side (3). This was where the smelter and the assay furnace were located. Experts checked the purity of the incoming metal before it was taken to the scales. A clerk was in the room to record exactly who had brought what and how much. Once the silver had been accounted for, it could be locked away in the room next door.

Fig. 3: Roller press minting was invented in Zurich and perfected in Hall. The roller press depicted here is a reconstruction that can be admired in Hall. Photo: KW.

Fig. 2: The aqueduct of Segovia. Photo: UK.

Fig. 1: Spain. Felipe IV. 1632 cincuentin (50 reales), Segovia. Only 10 specimens known. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 30,000 euros. From Künker auction 410 (2024), No. 84.

This walk-in vault had no windows. It was only accessible through the room with the scales.

On a lower level, but easily accessible via a ramp, was the great minting hall (4), where the roller presses did their noisy work. Driven by the power of the Rio Eresma (5), the wheels set in motion the heavy machines that produced the coins. Today the museum’s exhibition room is located here. Visitors can learn details about the history of the mint and its machinery. They can see archaeological finds from the mint and some original roller presses. Most impressive, however, are a number of working machines that are set in motion during the tours. These include the replica of a roller press (6) and a hammer coining press (7).

From the minting hall, you can enter another room where metal sheets and – after the introduction of screw presses –planchets were produced and reworked. It was turned into a nice restaurant. A visit to Ingenio Chico is highly recommended.

This is the end of the tour, but do not forget to return to the ticket office. There you will find great literature on minting technology and numismatics. The works are available in Spanish and English.

If you are in the area, do not miss out on visiting the Segovia Mint! It is considered the oldest surviving example of industrial architecture in the world.

Dr. Ursula Kampmann

The large entrance gate to the Segovia Mint. Photo: UK.

The prison of the mint. Photo: UK.

The large L-shaped building complex where the delivered metal was processed. Photo: UK.

The minting halls are located at a lower level. Photo: UK.

The water turns the mill wheel, which in turn sets the roller presses in motion. Photo: UK.

Reconstruction of a roller press.

Photo: UK. Reconstruction of a hammer coining press. Photo: UK.

Elephant Coins: 1. Greeks and Asian Elephants

A

visit to the Mannheim-Ludwigshafen Coin Collectors’ Club

This year, the Künker auction house is once again supporting the work of numismatic associations by financing lectures. As part of Künker’s support for numismatic scholarship, I gave a Künker lecture at the Münzenfreunde MannheimLudwigshafen on 12 June 2024.

The Chairman of the association, Claus Engelhardt, had selected the lecture about elephants on coins from three lectures offered in consultation with the association members. The focus was to be on coins from antiquity, but views of later times were also desired. In this lecture, I wanted to use a few examples to give a first impression of what rulers wanted to express with their depictions of elephants on coins, and which historically significant events are reflected by such coins. In this issue of Exklusiv, we publish the first part of the lecture, which deals with the Greek world.

Once again, it was a great pleasure for me to meet with the members of this extremely lively association and spend an evening in the “Zorba the Greek” restaurant with them, discussing the topic of the lecture and general aspects of coin collecting.

Our special thanks go to Professor Frank L. Holt, who provided us with a photograph of the Alexander double daric by

Images of Elephants, Today and in the Past

Thanks to a brilliant German humourist and a TV show, our modern image of the elephant in Germany has been infiltrated by the idea of a cute and bright, but also somewhat silly cartoon-, plastic- or stuffed animal called Wendelin, who eventually ties a knot in his trunk so as not to forget anything important (Fig. 1).