10 minute read

MIRA ADOUMIER

PERIPHERAL LANDSCAPES

Mira Adoumier (1985, New York) is an author/independent filmmaker based in Beirut and Amsterdam. With an initial background in Psychology, Philosophy and Biology, she later completed a degree in Film Production at the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema (Concordia University, Montreal). Through her fictional, essayistic works and video installations with landscapes, she explores the relationship between peripheries and centres, opening spaces and strata of possible and alternate realities. Her first feature, ERRANS, premiered at CPH:DOX 2020 in the next:wave competition.

mira.adoumier@gmail.com www.miraadoumier.com

Your research centres around the notion of exile. What drove you to this topic? First and foremost, it is a condition in which I was born. My parents both fled the war in Lebanon in the eighties and after that we moved from one country to another. I was born in New York, lived in France, Indonesia, Malaysia, Tunisia... I was not only constantly living in exile, but also with a constant feeling of displacement. During my first semester at the Master, the focus was on subjectivity and our perspective as a filmmaker onto the world. I realized that as a subject, I have always evolved in the “in-between”: in between countries, cultures, languages, passports… I thought of this in-between space as a third space, at the junction of two spaces.

In our second semester on methodology, I started thinking of cinema and exile, in particular: What can the practice of cinema offer me to further define and explore the exilic position beyond mere representation? I was never really interested in the theme of exile as such but rather how I could convey through cinematic means the experience of the exilic position, the experience of alienation, of being in the liminality and the subjective experience of the specific relation of space-time that stems out of this external/peripheral position.

What I retain from my first year was the idea that there is a multiplicity, a multilayered potential encapsulated in that idea of periphery. The periphery is always multiple, whereas the centre is one. I started thinking more of peripher(ies) and the centre, and their relationship to each other, how they inform each other.

How do you define being decentred? Being decentred underlines that there is a centre (of gravity) and as such, it is defined by it. Being decentred means living in multiplicity. I see the centre as a place of power and dominance. I also see it as a subject of interest. In my research I used the concept of ‘decentred’, and I explore it in the two projects that I worked on: the periphery as a decentred landscape, a landscape from which I can look onto the centre more clearly than I could the other way around. These two landscapes were the forest and the night.

I don’t know what came first. Whether the theory informed my practice or the other way around, but I started noticing that instead of filming the subject, be it a character or an idea, I would turn the camera around and film the landscapes that contain the subject. it started in 2017 with with my feature film ERRANS (2020), which follows a woman looking for a man she met many years ago. One day, he went back to Beirut and she never heard of him again. The film starts with her arriving in Beirut by the sea and as she enters the city, going to each of the places and neighbourhoods he told her about, where he grew up, lived, and walked.

During my research on landscapes in cinema, I encountered an interesting concept. Fukei means landscape in Japanese. Fukeiron is a proposition developed by Japanese avantgarde filmmaker Masao Adachi in his A.K.A Serial Killer (1969). Instead of filming the subject of his film Adachi turned the camera around and filmed the landscapes in which the subject evolved and went through his life. When I was filming ERRANS, right before I entered the Master’s programme, I wasn’t aware of this cinematic proposition but I treated the landscape in which the man that the woman was looking for evolved, as a factor in how he evolved as a subject. But the relationship between life and landscape is also a reciprocal one. Landscapes in which we evolve not only influence us as a subject, but the perception of the landscape can also be a projection of our inner world onto it. According to the concept of topoanalysis developed by

Gaston Bachelard, human identity is intrinsically related to the places people have inhabited throughout their lives, with memories being stored in our physical surrounding environment. Related to this idea, Merleau-Ponty perceived landscapes as the homeland of our thoughts. Here, I find a lot of inspiration in the Impressionism movement, which

became only possible as a form of painting when painting was “freed” from the imperatives of representation after the invention of photography. Painters were finally able to express and transpose their inner angst onto their surrounding landscapes. Landscapes never felt as charged as through the brush of Turner or Monet. To come back to ERRANS, the woman in the film, whose presence is manifested through a voice over, is looking for the traces of this man she is looking for in the landscape, as if parts of him had rubbed off onto his surroundings.

The Fukeiron proposition is central in my approach to filmmaking. By turning the camera around 180 degrees, the idea is to expose state power and systemic violence which is necessarily embedded in the landscape. The thing missing for me in this approach are the impressionistic qualities that can be extracted in a landscape. If the outer world is nothing but a projection of our inner world onto it, then filming landscapes can also pertain to exposing an interiority. Beyond the political scope, it is something that I look for when I point my camera.

How do you use the periphery as landscape in the research projects you present during the Artistic Research Week? One of the outputs of my research is a three-channel installation called Dreams of a Wandering Octopus about a thousand-year-old forest in Lebanon. In this project I use the forest, which is on the edges of the mountain that is in the middle of Lebanon, as a peripheral landscape. The coastal parts of Lebanon contain its social and political centre. Instead of going on the streets where the revolutions were happening, I decided to go very far away to question and think about these events from the periphery. I was hiking in the forest between trees that are 2000 years old and imagining what they would tell me if they could speak. Part of the background research I did for this forest project was also looking into how forests are organized underground. Here, a whole network of structures is all functioning horizontally. Trees reroute resources to parts of the forest that are missing them. Not because they share any socialist ideology, but more because if one of them dies, they all are exposed to more elements and have fewer chances to survive. It is better that all of us stand together, and it would be interesting to look at how nature or natural organizations are structured to rethink how we relate to one another and to the environment as well. In a way, a form of ‘political botanism’.

My second project is a feature film project entitled The Night Came About. The Night Came About is a film I have been carrying with me for the past couple of years. It has been fed by my night excursions across Beirut over the years, observing the night and people I would encounter only there. Beirut is a small city, overcrowded, cramped, compartmentalized and where one cannot escape the constriction of conventions, where anonymity is impossible. The night offers a space of emancipation and a place where people of different social pockets can meet. Without idealizing it, the night was the only place where I could encounter over the course of the same night Palestinians living in refugee camps, university students, foreigners on a humanitarian mission, people from different spheres, class and worlds, people that didn’t have a place in the daylight. At dawn, I would watch these fortuitous groups separate, each disappearing into their burrows. I began to think of a night which, unlike the others, due to a certain accumulation in the atmosphere, suddenly transforms: Time stood still or rather, daybreak never came. An eternal night which could only end when the accumulation of tensions of all the violence stored in the bodies and in the memory of the landscape and its people would gather and turn towards the same horizon. The night would overflow, taking over the day, irrevocably changing the order of the old world maintained by the ineluctable succession of days and nights. In the end, isn’t this the essence of a revolution? A vertical breach in the horizontal course of time which, like a seismic wave, deviates its course in irrevocable, unforeseeable, and unimaginable ways?

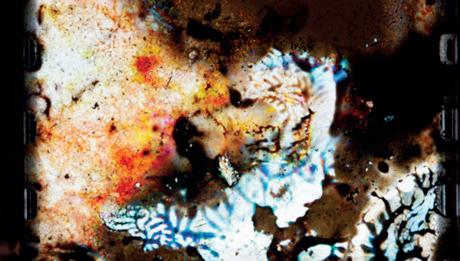

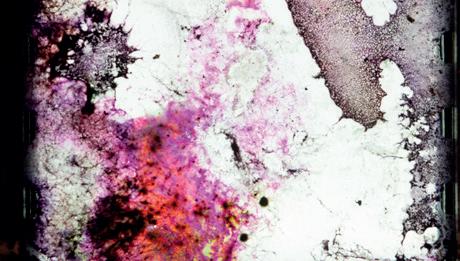

My third project was conceptualized during the production of Dreams of a Wandering Octopus. During my research, I started looking at different literature and scientific books written about forests, their ecosystem and particularly about how they organize, communicate, and distribute their resources underground through their roots and the web of mycelia that covers entire forests. I thought of ways to film or record this underground activity. As such, I decided to bury 35mm film rolls under the different areas and forests I was filming. At first, it was more of an experiment. I soon realized that the chemical reactions taking place differed according to the humidity level, the fungi structures, pH of the soil etc… The images that came out were like complex impressionist and abstract patterns. I thought to myself that if images are the result chemical reactions triggered and sculpted by light on film, these were also images resulting from chemical reactions except underground, without my intervention, a sort of a recording of the forest’s “subconscious” …

Interview by Lianne Kersten

Dreams of a Wandering Octopus (2021, 21min, 3-channel video installation) I watch you disappear behind the rocky hill as you walk lightly away, looking for your way back through the forest we got lost in. You asked: Do we come to nature to preserve our limits or to surpass them? Three voices unfold over three screens as a woman plunges into the depth of a thousand-year-old enchanted forest.

production The Camelia Committee with the support of the Beirut Art Center and the Master of Film editing Carine Doumit texts Mira Adoumier, Carine Doumit and Mohamed Abdel Gawad cinematography Mark Khalifé and Ramzi Hibri sound recording Tatiana el Dahdah sound design Jad Atoui voices Ziad Chakaroun & Carine Doumit coloring Chrystel Elias

The Night Came About (2023-24, 90 min) The sun is setting for the last time over Beirut and the city plunges into the night. As the characters unfold one by one, they reveal a landscape ravaged by past wars and more recent traumatic events. The night is prolonged, never-ending, eternal. As they dance the night away, a strident sound infiltrates the sonic scape. The ones that can hear it seem to recognize each other. As they slowly gather, they set in motion the dawn of a new day.

script Mira Adoumier, Carine Doumit Recipient of Cinema Development fund by the Arab Funds for Arts and Culture

Impressions from the Underground (in-development, 35mm stills) Projections of 35mm still films buried for 2 to 4 months under trees located in different areas of in the thousand-year-old cedar forest in Mount-Lebanon.

With the help of Onno Petersen and Charbel Saade