SILENT OCCUPATION

Sarah van Sonsbeeck Artist in residence Amsterdam Academy of Architecture

AIR PROGRAMME

The Artist in Residency of Sarah van Sonsbeeck is a cooperation between the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture and the AIR programme of the Amsterdam University of the Arts. The Amsterdam University of the Arts invites the Artist in Residence to inspire students and teachers by confronting them with topical developments and issues from the arts practice. These tailor-made AIR programmes focus on innovation and connection in an international and multidisciplinary context.

WINTER SCHOOL

Curator: Sarah van Sonsbeeck

Coordination: Maike van Stiphout, Patricia Ruisch, Marjoleine Gadella

LECTURERS AND CONSULTANTS

in alphabetical order

Markus Appenzeller, Defne Ayas, Anneke Blokker, Jana Crepon, Maarten Doorman, Oene Dijk, Kester Freriks, Tijs Goldschmidt, Yasmijn Jarram, Laurens Jan ten Kate, Yuki Kho, Jan Richard Kikkert, Annick Kleizen, Maarten Kloos, Pelle de Koning, Barend Koolhaas, Filippo Lodi, Tracy Metz, Ahmet Öğüt, Jarrik Ouburg, Antonis Pittas, Jan Rothuizen, Radna Rumping, Michel Schöpping, Raphael Vanoli, Job de Wit, Fred Woudenberg, Hans de Zwart

COLOPHON AND CREDITS

Concept & idea

Sarah van Sonsbeeck & Roosje Klap

Graphic design

Roosje Klap

Photography

Eddo Hartmann

Text editing

David Keuning and Richard Glass

Flags printed at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten, Amsterdam by Guillaume Roux, Pieter Verweij and Katharine Wimett.

Publication printed in Pantone Silver on Popset Virgin Black by Drukkerij Tielen, Boxtel

Special thanks to Ahmet Öğüt, Marijke

Hoogenboom and the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten Amsterdam

Publisher

Amsterdam Academy of Architecture © 2019 Amsterdam Academy of Architecture and the authors

academyofarchitecture.nl

SILENT OCCUPATION

Sarah van Sonsbeeck

Artist in residence

Amsterdam Academy of Architecture

ATTENTION, EMANCIPATION, IMAGINATION

Marijke Hoogenboom

When the American composer and music theorist John Cage published his seminal book Silence in 1961, I believe he was less interested in proposing new compositional principles, but more deeply concerned with establishing a different relationship with his listeners, who in Cage’s view would not passively receive (musical) messages anymore, but emancipate themselves by being attentive to their surroundings, and by being able to step in and out of an acoustic world on their own will. Let’s suppose that he’s an artist that – like Sarah van Sonsbeeck – introduces silence not as lost time or as a means for retreat and withdrawal from the world, but rather the opposite: as a social necessity and an effective tool to relate to the world and to find out what it is to be human and how we want to live together.

At the Amsterdam University of the Arts, we have the privilege of trusting the innovative potential of the arts and confronting contemporary challenges rigorously with the expertise of artists. It was a great pleasure for us to have Sarah van Sonsbeeck as Artist in Residence and curator of the Winter School 2018. Having said that, her intervention into the territory of the Academy of Architecture does not stop with the end of the residency period. This booklet is a response to the research that Sarah has conducted with 180 students on the emerging role of silence within architectural practice. It is in itself an artistic proposal for the realisation of a great variety of ‘silences’, so that they can be experienced anew by an audience and generate imagination beyond the author’s intentions.

SILENT OCCUPATION a personal strategy for reclaiming space

Sarah van Sonsbeeck

Over the course of two weeks in January 2018, 180 students from the Academy of Architecture in Amsterdam and I joined forces during the Winter School. In this two-week research and design programme, students of architecture, urban design and landscape architecture explored the Kop van Java (Head of Java Island), an as yet undeveloped plot in the centre of Amsterdam. This new generation of designers is not just designing our built environment, but our mental space as well. How do we experience the space that is designed for us? How does it influence us and others? The space we presume to be our own (privately, architectonically, legally) is not as solid as architectural drawings or documents of ownership might suggest. We have laws regulating the right to have a home, and the quality of that home, but how about the right to silence? Or the right to speak?

On paper at least, ownership of a space may end at a physical border, but sound often travels past physical barriers. In 2006, I asked my noisy neighbours to pay a portion of my rent, for the space they were taking up in my home with their noise. This led to artistic research into reclaiming space, with works such as the Faraday Bag (2010), a ‘democratic tool for data silence’ shielding phone signals, and the Anti Drone Tent (2013), which renders users invisible to thermal imaging cameras. Inspired by the Occupy movement, I see my artistic research not as a

means of communally opposing a regime, but as a personal occupation, reclaiming the space we have lost.

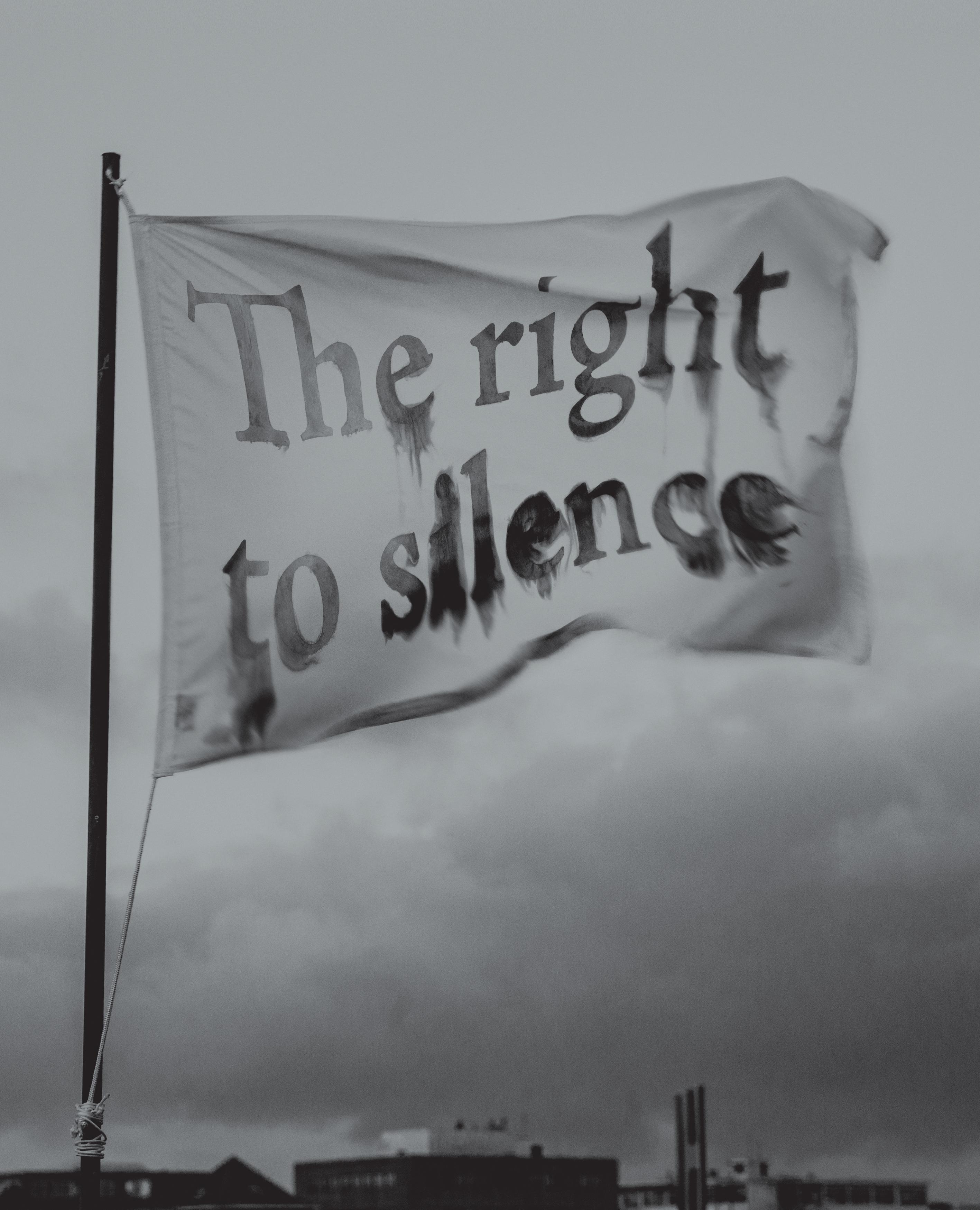

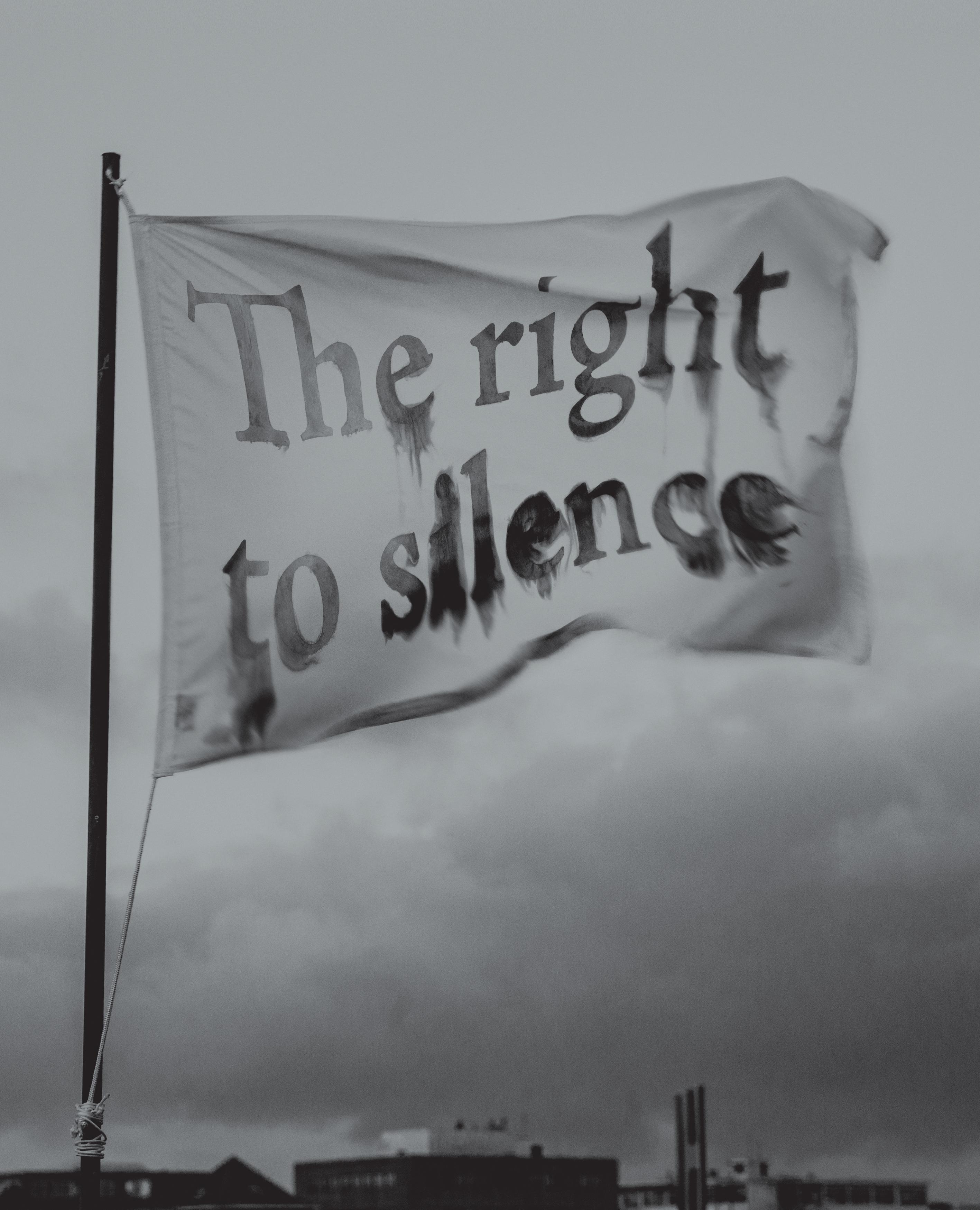

For this publication, we translated each of the students’ plans into a flag printed with a thought pivotal to their approach, in water-dissolvable black ink. We then planted these flags at the Kop van Java, in the same way a flag was once planted on the moon. We are not claiming physical ownership however, but claiming mental space, claiming poetry, claiming hopes and dreams of mental architecture and of what could be. The rain will render the flags unreadable as the thoughts are transferred to all who have seen them.

THE SILENT UNIVERSITY

Winter School opening night lecture (excerpt)

by Ahmet Öğüt

Many migrants in the UK are unable to practice their former professions. Due to their status, they may not be allowed to work or teach. Invited by the London-based Tate Modern and the Delfina Foundation in 2012, Ahmet Öğüt initiated the Silent University, giving a voice to people who are not normally included in British professional debates or education. Later, The Showroom also became involved. The first lecturers included a pharmacist from Syria, an accountant from Congo, a marketing manager from Zimbabwe and a calligrapher from Iraq. Since then, it has become an established platform. In 2013, the Silent University became active in Stockholm in partnership with Tensta konsthall. The following year, Stadtkuratorin Hamburg and W3 established the Silent University in Hamburg, Germany. Yet another year later, a new branch was established in Mülheim, Germany by the Impulse Theater Festival in collaboration with Ringlokschuppen Ruhr and Urbane Künste Ruhr. In his Winter School opening night lecture, Ahmet Öğüt talked about his initiative.

‘When talking about the Silent University I wouldn’t use definitions like “art”, “social project”, or “workshop”. The best word for it is a platform, a radical education platform. It’s an organisation that demands a policy change.

‘When I first visited London in 2012, I observed that many organisations were focusing on providing help to specific communities based on age, gender or ethnicity. That was before what mainstream media called the “migration crisis”. When millions flee from armed conflicts or other crises and arrive in Western European countries, they have to wait a

very long time before they receive their legal documents. I didn’t see any organisation that focused on the knowledge gained by those who are not allowed to work, through their previous education. Their university degrees are often not recognised because of restrictions of migration laws, language limitations and other bureaucratic obstacles. We skipped this waiting process and immediately recognised the knowledge of everyone involved and participating. Since then, every member of the Silent University has been working and collaborating as lecturer, consultant, or coordinator.

‘As an artist doing short-term projects, I’m often offered three-month long exhibitions or six-month residencies. In the art world, initiatives that last longer than two or maybe five years are not common. So how can you work in such a context on a topic like this, when you know it’s about a lifetime of everyone involved? We brought together universities, academies, art institutions, museums and community organisations in order to find ways to sustain the idea longer than one single organisation can commit to alone.

‘First, I thought it’s important to make it easy for the lecturers, so they could give their lectures in their native language or in the language they feel most comfortable in. It’s our problem, as an audience, to understand what’s being said. In the beginning, we tried different methods. We even tried silent lectures. That confused everybody. It was already a big challenge for everyone to be present actively during a lecture presented in multiple languages. Sometimes, more than five languages were even involved simultaneously, everyone was translating for each other.

‘The solution cannot just be creating an online education platform, as it’s a physical problem. People are invisible and not recognised where they are. We have to honour everyone’s presence. I didn’t want to initiate yet another marginalised organisation. I always wanted to challenge the existing institutions. That’s what we did. And we were able to transform

those institutions to a certain extent, because they were able to work with the Silent University. That was the main achievement I would say, but there is still a long way to go.’

Student: ‘What was the “art” part in it? Please help me out.’

Ahmet: ‘Yeah, what’s the “art” part in the Silent University? It was a general confusion from the start. I had to explain an idea that didn’t exist yet to the people that came to the first meetings. But only they had the power and the knowledge to make it happen. First, I had to convince the institutions that even if we would start within an artistic context, the lectures would ultimately transform into a collaborative yet autonomous organisation. And that’s what happened. Some of the branches are well established to the extent that even if the directors of the collaborating institutions change, that doesn’t put the continuity of the Silent University in danger.

‘Demanding a change of perception is important. I think art, or an artistic position, doesn’t have to be limited to artistic action. If I always keep acting as an artist, I will sabotage my own ideas. Now, after six years, the Silent University is autonomous and independent from me. I only see it from a distance. Before, they wouldn’t even start without me. It’s what I wanted it to become. That’s the power of art. Exactly there. When you don’t limit art to itself.’

thesilentuniversity.org

THE UNTOUCHABLE PRESENT

Sink the Kop van Java (Head of Java Island) just below the water surface, creating a water mirror

Jeroa Amanupunnjo, Daniël Ankoné, Jelle Engelchor, James Heus, Ergin Kurt, Iris Lunenburg, Bram Oude Monnink, Anna Torres, Piero Vidoni, Inga Zielonka

DISAPPEARING IS AN ACT

A structure blowing in the wind, alternately hiding and revealing its surroundings

Joep van Amelsvoort, Chantal Beltman, Wim Caspers, Renee Duijzers, Henry Holmes, Hester Koelman, Philip Lyaruu, Pedro Silva Costa, Veronika Skouratovskaja, Loretta So

THE RIGHT TO SILENCE

A field of thoughts where everyone may plant a flower to remember

Stephanie Ete, Myrna Eussen, Eek van der Krogt, Vincent Lulzac, Wieger Postma, Jordi Rondeel, Maurice Visser, Robert Younger, Anna Zań

A LANGUAGE WITHOUT WORDS

A voluptuous landscape of acoustical earth mirrors receiving and broadcasting sounds

Philippe Allignet, Onno van Ark, Ayla Azizova, Stijn Dries, Lejla Duran, Niels Geerts, Milo Greuter, Jacopo Grilli, Flavius Ventel

THE UNSPOKEN TAKES A SEAT

A landscape of chairs, inviting speech or silence

Anne-Roos Demilt, Daan Foks, Boukje Gabreëls, Sebastiaan van Heusden, Jacob Heydorn Gorski, Koen Karst, Danijela Kirin, Noury Salmi, Léa Soret

The elements take charge, turning the Kop van Java (Head

of Java Island) into a wave breaker again

Blake Allen, Jean-François Gauthier, Nina Kater, Danny Kok, Steven van Raan, Steve Schaft, Susanna Scholten, Monique Verstappen, Hongjuan Zhang

RECLAIMED BY NATURE

LET THE ISLAND SPEAK

Large antennas receive undetectable sounds from the Kop van Java (Head of Java Island)

Nedyalko Balev, Roy Damen,

Stephanie van Dullemen, Sanne Janssen, Dennis Koek, Tom Lodder, Sanne Mulder, Carolina Nunes Pereira Chataignier, Aoi Yoshida

SILENCE AND I HAD A TALK

This group wrote and recited a poem as their proposal, as to them silence is a highly personal experience that can best be experienced through poetry

Liza van Alphen, Matilde Bazzolo, Bastien Botte, Joske van Breugel, Anne-Marije van Duin, Julia Gersten, Shant Moushegh, Roxana Vakil Mozafari, Kasper Neeleman, Menno Ubink

SILENCE CAN BE SEEN

Make the particles in the air visible at night with a giant light beam

Tale Bjelland, Anouk van Deuzen, Giovanni Ferrarese, Wouter Grote, Nyasha Harper, Kinke Nijland, Sjaak Punt, Sharon Sportel, Elena Staskute

SILENCE IN THE FREQUENCY

An acoustical mirror to connect the Kop van Java (Head of Java Island) with the faraway

Tina El Chaer, Sophie van Eeden, Joris Gesink, Ignacio Gubianas, Niels Hulsebosch,

Despo Panayidou, Hanna Prinssen, Tom Bruins Slot, Tom Vermeer, Lauren Wretham

A ritual fire on the Kop van Java (Head of Java Island) to draw visitors in and unite them

all

Andrej Badin, Esther Bentvelsen, Ruben Dahmen, Sander Gijsen, Caroline Mazaro, Mees van Rijckevorsel, Fabien Tarvidel, Ritger Traag, Catherina Vanschoenwinkel, Wouter van der Velpen

MEMORIES I THOUGHT I LOST

COMING SOON

A large structure with the words ‘coming soon’ refers to all plans and hopes for the Kop van Java (Head of Java Island)

Thea Cali, Roel van Loon, Andreas Mulder, Kiwa van Riel, Marieke Schut, Jesse Stortelder, Vito Timmerman, Martijn Verhoeven, Mark Vergeer, Aneta Ziomkiewicz

GRADUALLY SLOPING

Let the Kop van Java (Head of Java Island) gradually descend, ending beneath the water’s surface.

Alex Berkmann, Jeroen Boon, Venetia Kollia, Tobias Kumkar, Jasmijn Rothuizen, Oscar Sanders, Ewout Vanvooren, Susanne Vruwink, Anne Wies

CEMETERY OF THOUGHTS

A cemetery to keep (un)wanted thoughts

Corné Bloed, Angelina Hopf, Jako Hurkmans, Kristina Košić, Evie Lentjes, Tessa Schouten, Martynas Solovejus, Max Tuinman, Laurens van Zuidam, Lui Xianglingrui

Ctrl Alt D el PARAKEET

Bring the disruptive green parakeet to Java Island by placing a heat-generating server park

Adan Çardak, Jan Eiting, Olivier Lodder, Charlotte Mulder, Matthijs Noordover, Ilona Pauw, Ana Barbara Pessoa, Tamara Redjem, Lindsey van de Wetering

A SCALE OF EXPECTATIONS

Float the Kop van Java (Head of Java Island) so its land level is determined by the weight placed upon it

Sherif Azmy, Vincent Janssen, Bart Jonkers, Rosa Jonkman, Maro Lange, Sveta Polishchuk, Ivo Susi, Viktoria Tashkova, Anne Floor Timan, Edgars Rozkalns

JAVA IS CALLING

A network of phone booths connects the Kop van Java (Head of Java Island) to numerous places in the world

Miks Bērziņš, Veerle Hendriks, Salaheddine Chekh Ibrahim, Art Kallen, Sybren Lempsink, Bart van Pinxteren, Marlena Rether, Laura Rokaite, Lesley Thoen

DO NOTHING

Do nothing, let the rest do everything

Yvette van Bakel, Sanne Danz, German Gomez Rueda, Jakub Jekiel, Jeroen Muller, Juliana Perrone Celotti, Magali Sanz, Quita Schabracq, Niek Smal