Mastermind

Thicker Than Water

A Model of Faith

Finding Her Pulse

Going the Distance

The Mane Attraction

The Duality of Ham

At Home

Knockout

Seeds of Change

Strings Attached

Light it Up

Second Chance

When Cultures Collide

Sculpted from Sweat

Mastermind

Thicker Than Water

A Model of Faith

Finding Her Pulse

Going the Distance

The Mane Attraction

The Duality of Ham

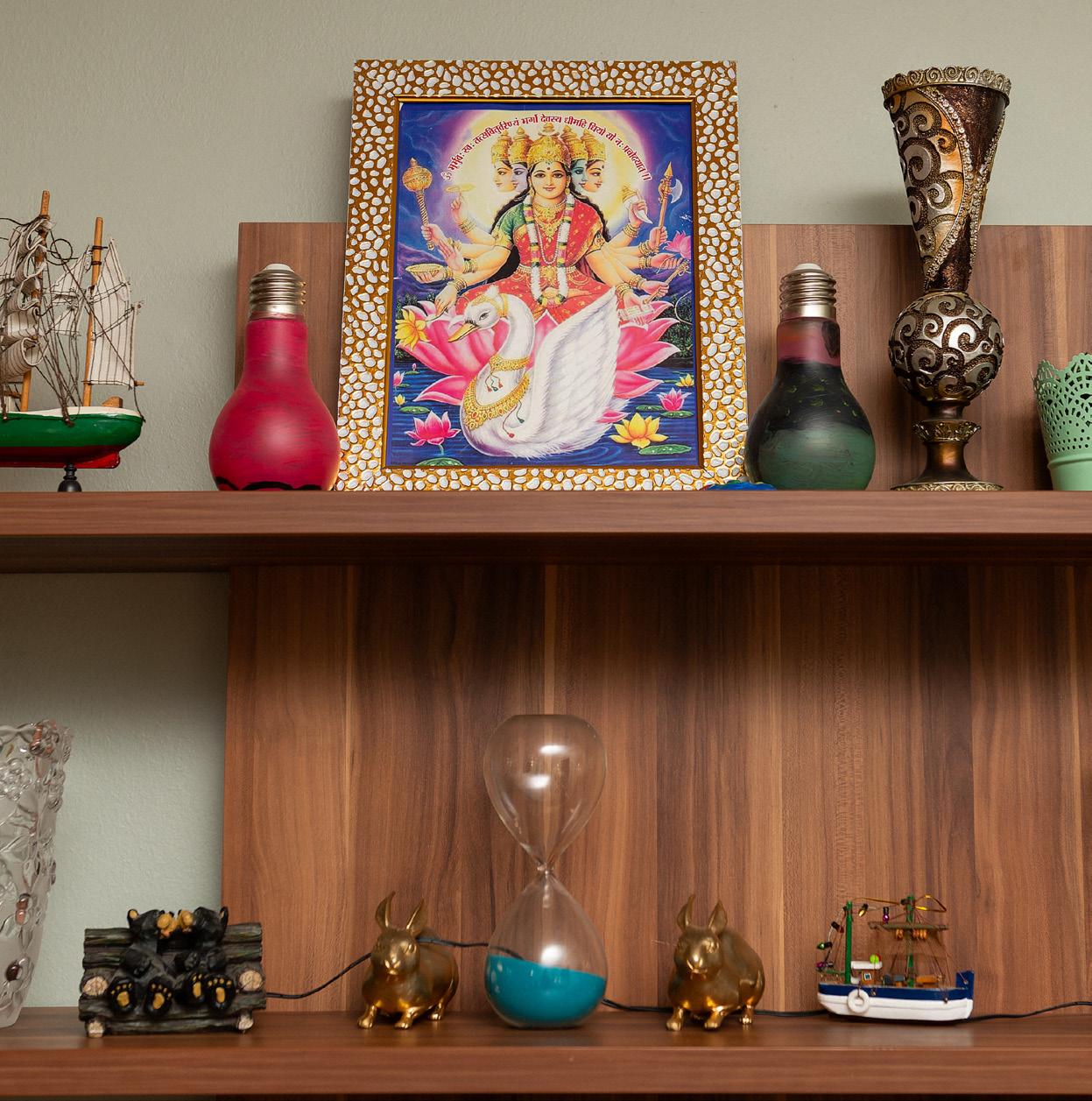

At Home

Knockout

Seeds of Change

Strings Attached

Light it Up

Second Chance

When Cultures Collide

Sculpted from Sweat

Going the Distance

ID magazine aims to represent the diverse population of Ladue High School and showcase the myriad of talents exhibited by the school’s students and faculty. Over the course of each issue’s conceptualization, the staff works hard to promote empathy, acceptance and open-mindedness amongst the student body. We hope to inspire readers to treat both our subjects and the world around them with sensitivity and care.

Scan to submit a correction or a letter to an editor

The Ladue High School administration agrees to allow the Ladue Publications staff to make content decisions and to operate as an opem forum, provided that they do not infringe on the rights of other students or create a substantial disruption at school as per the Tinker standard.

Scan to view Ladue Publications’ full policy

The doors swing open, letting in a bustling crowd. Some are weary-eyed from a lack of sleep, while others are as alert as ever. Still, even the most worn out individuals manage to muster enough enthusiasm to exchange the simplest of words with their peers. Starting at 7 a.m. nearly every morning, students and faculty flock to the school entrance. Together, they fill the halls with uproarious laughter, conversing and basking in one another’s company. At Ladue High School, no two students are alike. However, rather than allowing this to drive a wedge between them, they embrace one another’s differences.

In ID’s second volume, we strive to produce stories that aim to accurately capture the cultural makeup of our school’s population. This issue features a story about one student’s passion for fitness and competitive bodybuilding, and another profile that follows a student’s relationship with his faith and journey to becoming a deacon at his church. Though our collection of profiles all represent

differing aspects of identity, they are all written with the intention of celebrating and showcasing what makes the subject the person they are today.

As always, ID makes an effort to bring the community closer together by sharing details about the students who complete our school. Our publication firmly believes that inside each individual is a story, and what a pity it would be for such stories to remain untold. Thank you for taking the time to read about us, and welcome back to ID.

Executive Editor in Chief

Arti Jain

Managing Editor in Chief

Sylvia Hanes

Design Editor in Chief

Maya Mathew

Content Editor in Chief

Ella Braig

Copy Editors in Chief

Will Kodner

Katie Myckatyn

Photography Editor in Chief

Vincent Hsiao

Sta

Kaichen Chou

Loukya Gillella

Tiya Kaul

Nathan King

Emily Pan

Annabelle Reagan

Ira Rodrigues

Nyla Weathersby

Nina Ye

Isaac Zelinske

Michael Zegel

Photographers

Harper Buxner

Lathan Levy

Bella Soyfer

Isak Taylor

Advisers

Abigail Eisenberg

Sarah Kirksey

Alex

uncovers his identity by competing in national chess tournaments

Pieces being captured, clocks ticking and pencils racing against time to scratch notation echoed across the capacious room, decorated by a maze of black and white patterned checkerboards separating players. The tension between them could almost be torn apart with bare hands. A tumultuous silence among the significant number of people situated within the same space fosters an eerie silence, heightening the anxiety levels between observing spectators. A certain individual quietly sits back down at his table, mind refreshed, body rejuvenated and ready to win.

Alex Zhang (9) began his journey with chess when he was 6 years old, progressing into a national master. As of December 2024, Zhang ranks top 50 within his age group throughout the entire United States. Zhang’s passions first started when he watched his older brother, Max Yang, play a game of chess with his friends, sparking the flame that captivated Zhang into his lifelong journey with the game.

“[Alex] asked me to teach him how to play,” Yang said. “I remember that when I beat him the first time [Zhang was 6], he would flip the board over and get mad. But, he was persistent and kept wanting to play.”

Chess is a highly integrated part of Zhang’s life, and also plays a role in uniting and developing closer bonds with his family and friends. Zhang met his good friend, Ayden Huang (9) through chess in early elementary school. Since then, they have attended a variety of competitions together, even establishing a tradition to grab dinner at a few restaurants after their tournaments.

“The most memorable being the Chicago Open when I won $2000, and Barber, where I finished in third place.”

Currently, Zhang takes one-on-one online chess lessons from a tutor in Azerbaijan. While he used to have multiple coaches –– sometimes simultaneously –– and lessons in-person, he has transitioned to virtual sessions for their efficiency. When every second counts, saving time by eliminating the need to commute to and from lessons saves more time for Zhang to spend on chess or other activities.

“I got stuck for a long time at around 2200 rating,” Zhang said. “I was able to overcome it through intense training and work, [and] a good mentality going forward.”

Typically, Zhang practices consistently every single day. The amount of time he spends practicing varies, mainly depending on whether it’s a school day or weekend, but he always aims for about two or three games per day. At his level, each game could last between one to three hours.

“Chess has changed me as an individual,” Zhang said. “I was able to develop much better problem solving skills, as well as decision making skills. It also has allowed me to learn to trust my intuition, or gut feeling, a lot more.”

"I enjoy [finding] the best moves that allow me to outplay my opponents."

“There’s been a few times [when] we both won money, and those are definitely good moments,” Huang said. “Often we’ll get food together once we [aren’t competing in a match].”

Alex Zhang (9)

At Zhang’s current level, tournaments are scarce and conditions are high for the few he can attend. A single trip to a good tournament can cost thousands of dollars, consisting of hefty financial requirements such as travel expenses, food for a few days and tournament entry fee. This doesn’t account for the amount of time spent planning or traveling and other events missed throughout the duration.

“When I was 7, I played against a high school student for my first game,” Zhang said. “I was winning, when my opponent literally took one of my pieces off the board. Obviously, he was cheating, but the arbiter for the tournament wasn’t very experienced and didn’t do anything. I won the game, but it was quite [the] amusing experience for me.”

Zhang was selected to represent Missouri in one of the most prestigious competitions. One player was selected from each of the 50 states to compete in the competition, representing their state. At a national tournament, Zhang won 7th, ranking top 10 within his age group at the time.

“I competed in many chess tournaments,” Zhang said.

For someone who has continuously competed for almost eight years, burnout is an exhausting and relentless challenge. As a freshman starting high school, not only will Zhang need to balance his increasing academic workload and extracurriculars, he will also continue perservering in overcoming the burnout. Zhang has developed many important life skills from playing chess, such as self-motivation and confidence. These skills helped him persevere and flourish into the individual he is today.

“[Alex] is very confident,” Yang said. “Even after tough losses, he is able to bounce back quick.”

Zhang plans on continuing his chess journey throughout his high school career and the rest of his life. The game has become an inseparable part of himself. It defines a part of his identity, and majorly contributed to shaping his character into the national master he has become today.

“I hope to make it into World Youth and represent the U.S. team, or reach the Fide Master title,” Zhang said.

Captions: Alex Zhang (9) sits before a chess board, pondering his first move. He has beaten his friend, Huang, in speed chess five times in a row. “Once upon a time, I was higher rated than him,” Huang said. “It’s humbling to say that, but I’m also very proud of him, and very happy he’s managed to reach these levels of growth.” (on page 5)

Zhang stands behind a chess board, symbolized as king of the game. His brother believed that Zhang’s patience and calmness allowed him to win matches.“It was the first thing he gave his all to,” Yang said. “He grew a lot as he learned what it meant to be passionate about something and work hard to achieve your goals.” (on page 7)

"He’s always been a confident person and that translates to chess rather than the other way around."

Max Yang, brother

Following in her siblings’ footsteps, Ruby Jurgiel discovers her own love of water sports

The sound of laughter drifts across the pool deck on a hot summer evening, drowning out the splashing from the swimmers in the pool. Cheers echo in the humid air, and the building enthusiasm is palpable. It’s Monday, which means competition day for Brentwood Swim Club. It also means an outing for the entire Jurgiel family.

Ruby Jurgiel (10) first gained her love for the water alongside her three older siblings at the Brentwood Swim and Tennis Club on the Gators Swim Team. Since then, she has become a tri-sport athlete. Ruby swims and plays water polo for the Ladue School District as well as pursuing synchronized swimming with a YMCA team and playing club water polo for the St. Louis Lions.

Ruby’s mom, Stacy Jurgiel, discovered the Brentwood Swim Club when her children were young. It was the family’s first swim club. While swimming eventually became an integral part of the Jurgiel family’s daily life, it started as a simple way to stay comfortable and escape the heat.

“Coming from Michigan, it was a little bit of a culture shock, and I couldn’t believe how hot the summers were,” Stacy said. “We immediately found a pool to join when we had kids so we could stay cool in the summer. They had a little lowkey swim team and we wanted to make sure everybody learned how to swim so we joined the swim team.”

As the children increased their team involvemnt, time management became very important. With an almost tenyear age gap between Ruby and her oldest sister, the Jurgiel parents were grateful for an activity that all participate in.

“It worked out great because… the whole family is all on the same team, so it’s very convenient,” Stacy said. ‘It’s one of the only sports where a wide variety of kids of different ages can all be on the same team, and you can be all there cheering each other on at the same time, at the same meet.”

This joint activity made it easier to coordinate their busy lives and maximize free time during the summer.

“The meets are on Monday nights and practices are every morning,” Stacy said. “It puts us all on the same schedule, on the same page, and that just makes for a much more enjoyable summer.”

However, preparing the Jurgiel children for a long, chaotic swim meet wasn’t easy. Stacy had to coordinate packing them up and sending them off to compete every week.

“[There were] lots of challenges, getting everybody suited up with their goggles and their towels and their snacks…” Stacy said. “Four kids off to a swim meet every Monday night. There’s a lot, but it was fun, too.”

In addition to supporting her children, Stacy found other ways to get involved on the swim team. Like many

summer league teams, the Brentwood Swim Club relies on parent volunteers to help organize and host swim meets.

“They have parents that are parent representatives that coordinate all the volunteers…I was getting involved in being the parent representative for many years on the Brentwood Swim Club,” Stacy said. “It was a lot of work, but so fun. I loved meeting all the families and all the kids on the team… I personally learned a lot, and I found it really rewarding to be able to be that involved in the team that all my kids were on.”

Although Ruby is an avid swimmer now, her entry into the sport was actually one of convenience, based on the Jurgiel family’s interest. As the youngest child, she remembers automatically following in her siblings’ footsteps.

“When I was little, they all swam,” Ruby said. “So as I grew up, I just did what they did.”

Her older siblings, Olivia, Jojo and George, aged 25, 23 and 20, respectively, paved the way for Ruby on the Ladue High School swimming and water polo teams. Some siblings might resent this similarity, but Ruby grew to actually love it. She gained confidence from watching her siblings participate in sports throughout high school.

“It made me more comfortable, just knowing someone else did it and had fun doing it,” Ruby said. “I like having that similarity between us.”

Besides building confidence, sharing a passion for swimming and water polo has given Ruby’s family something to bond over. It’s also helped them to understand each other better through struggles and triumphs.

“I can definitely talk about [sports] more with them,” Ruby said. “And they understand what I’m saying, versus other sports having a different language entirely.”

This connection is also meaningful to Ruby’s older siblings, especially her oldest sister Olivia. They are able to watch her journey and relate back to their own high school experiences as she succeeds and struggles in similar ways.

“It’s kind of cool, because it’s almost like watching it again happen from an outside lens,” Olivia said. “I know when I was in that experience, I remember not wanting to get up and go to an early practice Saturday morning, and seeing that same thing in Ruby. …but now I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, go… go take advantage.’”

In addition to connections from her siblings, Ruby had pre-existing relationships built with teammates and coaches from her club water polo team, the St. Louis Lions.

“All the coaches know me already,” Ruby said. “And most of them, I hope, like me because they liked my siblings and they know what to expect from me.”

Despite being guided by her siblings’ legacy, Ruby found her own place on the swim team during her freshman year of high school. That year, the team graduated a

large class of seniors, leaving this year’s roster with a high proportion of underclassmen. However, with some experience, Ruby looks to start the season strong.

“I’m excited to see us all come together because I know the captains last year brought everyone together,” Ruby said. “I think it’s gonna be interesting with the new freshmen and all the excitement.”

This familiarity has given Ruby the chance to forge her own path in a water sport that none of her siblings pursued: synchronized swimming. Years ago, she found a team at a nearby YMCA, where she still trains today.

“I think synchro was such a big growth avenue for her, because it’s a tiny team, and it was a team…of all ages,” Stacy said. “When she started off she was the youngest one on the team, when she was about 8 or 9 years old…So you just really learn a lot from the older kids.”

Ruby’s interactions with these older teammates taught her valuable lessons, not only for synchronized swimming but for her future as well. Joining the team at a young age shaped Ruby into a role model for her younger teammates.

“She learned an incredible amount, and has gradually grown up,” Stacy said. “Now she is among the oldest on the team, she’s got all these young kids under her and she’s become a mentor for the younger kids. They all really look up to her, and she really enjoys that. It’s been this kind of full circle.”

Like many young children, Ruby was not instinctively comfortable in the water. In fact, her parents had to enroll her in countless swimming lessons before she finally learned how to be relaxed.

“[With] swimming, you’re almost competing against yourself for faster time,” Stacy said. “Water polo is such a team sport, you’ve got to be really in sync with the other players. And, obviously, synchronized swimming is all about being in sync and making the athleticism look… very easy.”

Because they are so diverse, the three sports round out Ruby’s athletic identity. She works hard to maintain this balance, despite the demanding schedule and workload.

“Last year, she took a year off of synchro because she wanted to…play a high school sport and have that high school team mentality,” Olivia said. “She said that she really, really missed synchro, and that’s why she’s trying to do all three now. […] Even though it’s not part of the high school sports, [she’s] gonna still try to squeeze them all in. I feel like that’s something that takes a lot of dedication to make sure you make time for things that you love.”

These activities have taught Ruby more than just speed and coordination. They’ve left her with life lessons she is able to carry with herself beyond an athletic career.

"She’s become a mentor for the younger kids."

Stacy Jurgiel mother

“I never thought she would become a swimmer, because she took so long getting comfortable just putting her face in the water,” Stacy said.

Since, Ruby has conquered bubble-blowing and moved on to more advanced mental and technical challenges. Her aquatic abilities form the basis for all of her sports, but each one has its own unique skill set.

“You need to know how to swim for both [swimming and water polo],” Ruby said. “But swimming is all personal… and mental… versus [with] water polo [you] communicate with the teammates and throw the ball to them. It’s more about communication with the team versus individual performance.”

All of the sports that Ruby competes in require hard work and dedication, but each takes on a very different form of competition. Water polo and swimming, for example, center around fierce racing while synchronized swimming draws mainly from artistic performance.

“You learn about how to be a good competitor, how to be a gracious winner and a gracious loser and how to push yourself and persevere,” Stacy said. “Sports do so much of that.”

Sports have also taught Ruby to take pride in her achievements when hard work pays off. Her perseverance makes her feel accomplished and fulfilled once all is done.

“When [I’m] done with a practice or done with a meet, [I like] being able to look back and say, ‘I did that, I just swam that entire set,’” Ruby said.

Captions: The Jurgiel family swims together at a Brentwood Swim Club meet. At the time, Ruby Jurgiel (10) raced in the 6-and-under group. “[My parents] wanted us all to be together the whole time,” Ruby said. “At swim meets, that was where we were together.” Photos courtesy of Ruby Jurgiel. (on page 11)

Ruby chants the “L-A-D-U-E” and “‘Due Time” cheers with her teammates at Ladue High School Dec. 3 before their first swim meet of the season. This helped them bond with each other and get excited to race. “I think any high school sport is a great way to meet people,” Stacy Jurgiel, Ruby’s mother, said. Photo by Vincent Hsiao. (on page 13) Ruby competes in Ladue High School’s meet against Lindbergh High School, Mehlville High School and Oakville High School. Ladue High School won the meet with 182 points. Ruby placed second in her 50-yard freestyle event and also competed in three relays, swimming in a 50-yard freestyle, 200-yard freestyle and 100-yard freestyle. “When I’m swimming, I’m constantly counting strokes until the next breath and singing songs in my head,” Ruby said. Photos by Vincent Hsiao. (on pages 8-12)

ID

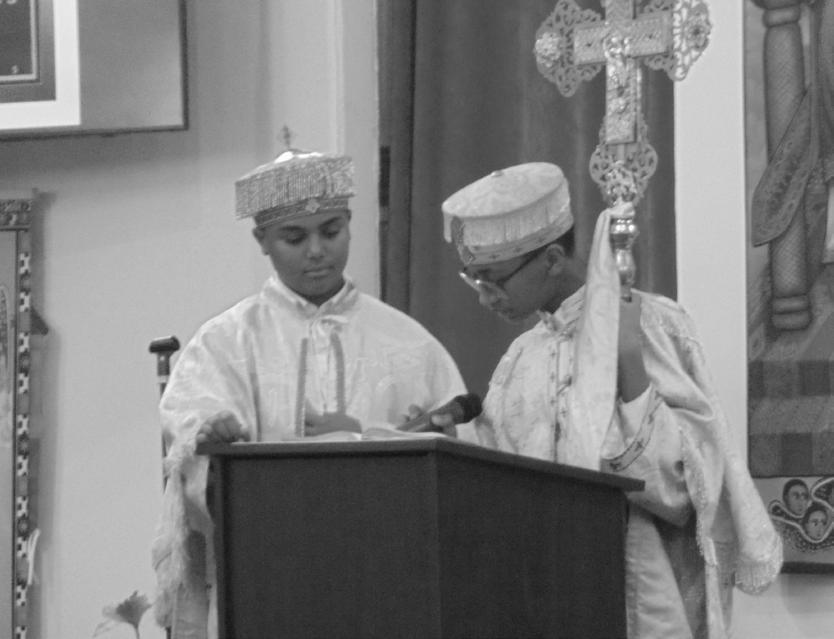

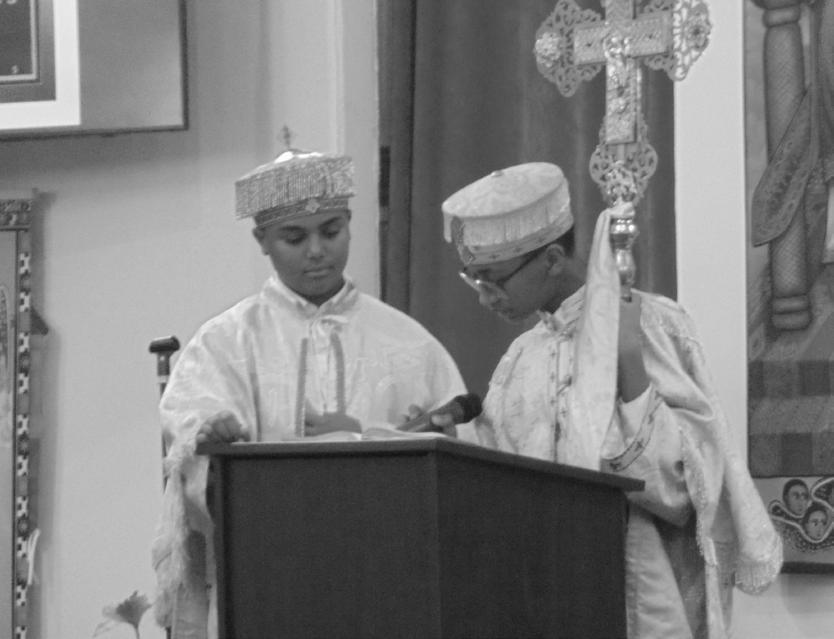

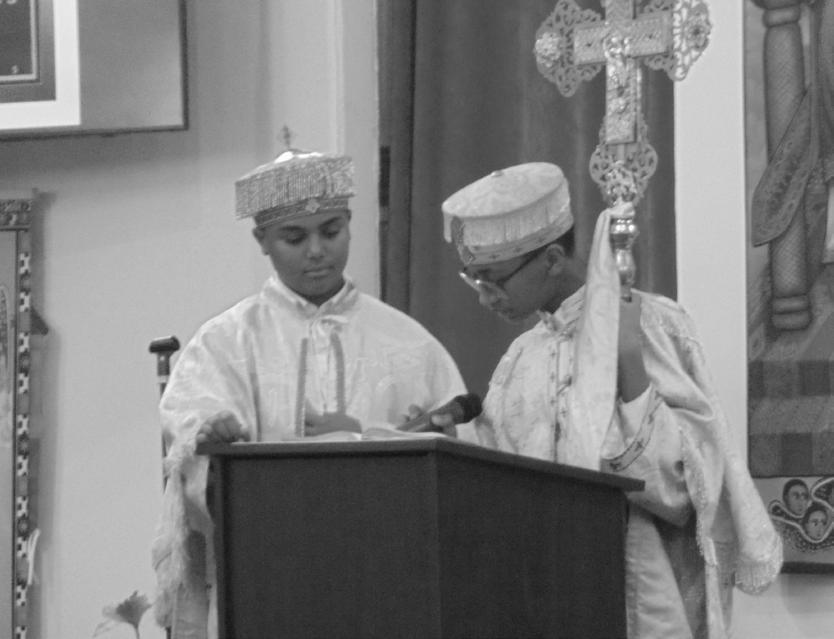

At 3 a.m., Fanuel Amede (10) rises. He dons a netela, a white garment traditionally worn by Ethiopian Orthodox men, and says a prayer, thanking God for his role in his life. At 4:30 a.m., he and his family drive to the Debre Nazreth St Mary and St Gabriel Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church and Amede takes his place at the front, assuming his responsibilities as one of the church’s deacons. Amede assists the priest in leading service, a sixand-a-half-hour long function in which participants stand to symbolize the struggles that God himself went through.

Amede became a deacon at the age of 10, assuming responsibilities of aiding the priest during service and helping around the church should needs arise. This decision was made after years of learning about the Orthodox faith and values through attendance at church every weekend.

“It was challenging at some points because I had to understand that it’s not like a normal job, it’s higher than that,” Amede said. “Everything you do is worshiping God, and it’s not a joke, not something you just do for fun.”

Amede especially fostered his knowledge by learning about the religious significance of different holidays.

“As a kid, when the holidays came, it was more like, ‘Okay there’s people coming from out of state to celebrate this holiday with us,’” Amede said. “But, since I became a deacon, I partake in more stuff and I see how these other deacons were taught, and that helps me get motivated to learn more.”

One of Amede’s older cousins inspired him to become a deacon. Amede said he viewed his cousin as a brother because of the amount of time that they’ve spent together.

“Before I became a deacon, I would see him and I would think, ‘Okay, I want to be that.’” Amede said.

Amede’s high level of involvement comes from an admiration for his uncle, a priest. From a young age, his uncle held lessons for Amede and his cousins within his home, teaching them the official Ethiopian language, Amharic, as well as other biblical stories and faith-based concepts.

“I see him as an uncle and as a father, but I [also] see him as a church father [because of] the respect I have for him and how much he teaches me,” Amede said. “Seeing everything he does motivates me.”

Wongail Belete (11) is Amede’s first cousin. Her father, the priest, taught the two of them together, strengthening each of their connections to the Orthodox religion and to each other. Because of the time they’ve spent together, Belete sees Amede as a brother rather than a cousin.

“I call his mom ‘Mommy’ because she’s raised me like her daughter,” Belete said.

Amede and Belete both sing for the church’s choir, a co-educational group that meets every Sunday to practice. They perform at church functions, teaching the community aspects of biblical history. This knowledge has also helped Amede further a love for his faith and religion.

“There’s a certain song that talks about this character in the Bible where she asked God to open her heart and [listened] to the word of God,” Amede said. “When we sing that, it resonates with me.”

Belete said that she’s found community due to the choir.

“I feel like I am able to express myself way more, especially while singing, and it’s a way I communicate with what I believe in my faith,” Belete said. “It’s also really fun. I have a sisterhood with it and I make a lot of friends.”

As a deacon, Amede spends over 10 hours at church each week, a number that is often higher around the holidays. This sometimes makes it difficult for Amede to balance his responsibilities with that of a typical teenager’s.

“Once you get older, especially in high school, there’s a lot of pressure,” Amede said. “I’m always trying to find time to manage my life with God and everything. It’s not hard, but I would say it gets harder the older you get.”

While the responsibilities may sometimes be a lot to manage, Amede doesn’t complain, as his high level of church involvement is by choice. He takes on the responsibilities due to an internal desire to feel connected to God.

“At the end of day, I wouldn’t make that an excuse for myself,” Amede said. “I feel like there’s always time for God and, so, you can always find something to do.”

Amede has learned to navigate this balance largely due to his sister, with whom he shares a 7 year age gap. As the leader of her own religious choir, Amede’s sister sends him and his church weekly songs to practice and perform.

“She’s kind of like a role model for us,” Amede said. “She motivates me to push myself in the church, because I see her doing good things.”

One of the ways in which Amede resolves to further his commitment to God is by adhering to a fast during the holidays. However, Ethiopian fasts don’t only discourage food — they also warn against behaviors deemed to be sinful.

“I try to be less on social media when I’m fasting, especially during [the] Christmas fast and [the] Easter fast, because I’m like, ‘Okay, there’s better things for me to do. Instead of scrolling, I could be praying or doing something productive,’” Amede said. “I [also] try to cleanse my mouth by saying less cuss words and saying less things that I shouldn’t be saying.”

Beyond himself, Amede encourages Adam Esayas (12) and his other peers to adhere to periods of fasting.

“I get tempted to eat meat or dairy, but he gives me encouragement,” Esayas said. “One of the funny things he would say is, ‘If you fall on the sidewalk, you’re not just gonna stay there. You’re gonna get back up again.’ So it’s like, if you fail [the fast], you still can come back to it.”

Amede strives to serve as this role model to his peers because of the responsibility he assumes, both as a young deacon and as member of the Ethiopian Orthodox church.

“Our church fathers would always tell us, ‘What you do outside of church and stuff reflects onto our church as

a whole. You being kind to others, you showing them the right path, helps our church and that puts in a good word,’” Amede said.

This type of outreach has created a highly connected Ethiopian community at Ladue High School. Esayas found that this bond helps when following traditional values.

“I feel like if I went to a different school that didn’t have Ethiopians, I would break the fast, like, every day,” Esayas said. “Or, I would do this or that, because I don’t have anyone watching over me, which is helpful here, because I use them as a guide to not break anything.”

Amede said that going to school with Belete has strengthened their own bond, both as cousins and friends.

“The connection builds trust,” Belete said. “I trust him and he trusts me whenever it comes to advice and helping each other out with things. Even when it comes to [academic] clubs, we tell each other, ‘Oh my God, we should join this club together.’”

Due to Belete’s encouragement and personal involvement, Amede joined UNICEF, a club that raises money to provide resources for disadvantaged children throughout the world. Amede believes that the club is important to him because it follows his church’s value of helping others.

“Something that’s always been said in our religion and in our faith is ‘Give back to the people,’” Amede said. “This is my time to give back to people in need.”

One of the ways that Amede gives back is by teaching his peers to love God just as much as he does. At church, Amede teaches aspiring deacons stories and values of God.

“I feel like we learn what’s right and wrong together,” Amede said. “[With] me being older, I feel like I can be a role model for them and show them what they need to do.”

Among the group of aspiring deacons is the younger brother of Amede’s older cousin. This cousin was the one who inspired Amede to become a deacon in the first place.

“Seeing him study, it’s like a mini-me,” Amede said. “I used to be in his shoes, learning stuff about God and having to decide what I needed to do in church.”

Captions: Fanuel Amede (10) serves as a deacon at the Debre Nazreth St Mary and St Gabriel Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, an institution that he’s attended with his family since he was a child. Many of the church’s younger participants are also enrolled at Ladue High School with Amede. “We’re still friends, we’re still brothers and sisters, but it’s also [that] we revolve God around most of our conversations,” Amede said. (on pages 14-17)

The church features various religious symbols, especially in detailing on the walls and traditional garments worn by Ethiopian Orthodox priests. Wongail Belete’s (11) father is one of two priests in St. Louis church, and his involvement has helped Belete strengthen her own connection with God. “I’m much more educated on the topic of church, and that makes a lot easier for me to talk about it and not be afraid to do so,” Belete said. (on page 17)

"I’ll pray in the morning, at night and before every meal, and just thank God whenever I can."

Fanuel Amede (10)

Ring. The alarm clock goes off. Creak. The wood planks under the bed groan as she wakes from her slumber. Click. The snare drum opens — a symbolic motion, telling her the time is now. Rat-a-tat. The snare drum begins to sing its monophonic hymn, and Kimmi Lin (11) orchestrates it. Amidst the soft spoken voice and lowtempered manner, Lin begins her morning practice routine.

“Kimmi has the ability to really play perfectly, kind of in almost any situation, including very high pressure ones,” Tim Crockett, Lin’s percussion instructor, said.

Lin has been taking weekly percussion lessons with Crockett for the past seven years. They have prepared for numerous auditions over the years, from local group auditions to the National Youth Orchestra ones.

“Having a private teacher is important because they know more than you do,” Lin said. “[Something] may sound good to me, but it’s not actually that good.”

Kimmi is a percussion player — a musician whose capabilities are open to every instrument that is stricken, slapped or hit. While native to the drum set since age 7, the Ladue Percussion Program has allowed Kimmi to pick up a plethora of other instruments, mainly including timpani, marimba, snare drum, bass drum and several others.

“I don’t really do anything as much as I do percussion,” Lin said.

Lin is a part of several musical groups spanning from St. Louis to Taiwan. She is a percussionist for the Saint Louis Youth Symphony Orchestra, Webster Groves Young People’s Symphonic Orchestra and this summer, she received a full scholarship for 2 weeks touring with the Taiwanese National Youth Orchestra in Taiwan, where she was already spending the summer with her family. However, music is only a part of the trip.

“[My favorite part was] meeting the people there,” Lin said. “I feel like Taiwanese people are nicer.”

When playing and studying classical music, it is often a matter of precision — a numbers game, whereas in genres like jazz, it is typically a more creative endeavor. However, Lin finds a way to get the best of both worlds.

“I like listening to jazz more than I like listening to classical music, but I like playing classical music more than I like playing jazz,” Lin said.

Many view music as a pure form of expression, but Lin finds it comparable to other parts of her education.

“You have to learn the notes first, and then you focus on smaller details,” Lin said. “It’s kind of like math. When you practice, you have to repeat it a lot. You have to learn the formulas, you have to apply them and they get harder.”

her freshman year. However, her approach to practicing these monotonous etudes is unconventional. She uses highlighters to signify musical notation to read it by color, rather than by inked notation. Sharps are pink. Flats are blue. Loud is cool colors and soft is warm colors.

“I usually have to color my sheet music or else I almost can’t read it,” Lin said. “It’s how I first learn it. I color it before I first play it. It makes it easier to approach music because it looks so cute. I did it on my all-state music last year and it’s on my all-state music this year too. Last year, I put stickers on it so I would be motivated to practice.”

While music is often seen as a solo endeavor through concertos or long hours in the practice room, the real value is extracted out of the camaraderie of playing in a group.

“It’s both,” Lin said. “You have to like music personally, but the group makes it different.”

Norah Murphy (11) has been playing alongside Lin in the Ladue percussion section since seventh grade, often competing against each other for out-of-school music groups. They currently play together in the Saint Louis Symphony Youth Orchestra and the Webster Groves Young People’s Symphonic Orchestra.

“She’s very sarcastic and humorous, but when she’s playing percussion, she’s very serious and down-tobusiness,” Murphy said. “Kimmi is as good as it gets considering percussion. Her strong suit is being able to be precise and accurate.”

While music is often a great unifier, competition can often separate friend and foe. However, Murphy and Lin’s friendship surpasses the division of rivalry.

“Kimmi and I are very good friends,” Murphy said. “I love Kimmi because I can talk to her about percussion, but also just [about] my normal life.”

Lin is Taiwanese and visits every summer. During her trip a few summers ago, she picked up a teaching venture not directly related to percussion, but it turned into a takeaway for her practice routine back home.

“Two years ago in Taiwan, I taught my mom’s friend’s kids English and ukulele,” Lin said. “It taught me that I don’t think I’d be a good teacher. I was impatient. I need to take a lot of breaks and I incorporate that into my practice.”

Captions: Kimmi Lin (11) stands alongside her instruments in the Ladue High School Performing Arts Center Dec. 3. Lin’s favorite artist is Laufey. “School and practice are separate. I don’t like school, I like percussion.” (on pages 18-19)

Lin performs a bass drum etude. Tempo is an important factorduringauditionsandLinbelievesthisisacomponent to her success. “For 120 [beats per minute] I use ‘Stars and Stripes Forever.’” (on page 21)

In Missouri, there are two opportunities to compete as public high school musicians. All-suburban is composed of students from districts in the metro area, and all-state is composed of students competing from the entire state of Missouri. Lin has placed first chair for every audition since ID

Lin plays the snare drum. Lin prefers paper sheet music over digital. “My handwriting looks better on iPad, but you can’t really decorate on iPad. I also prefer sheet music because I don’t have storage on my iPad.” (on page 21)

"Kimmi is a completely diferent person when she’s holding a pair of sticks."

Norah Murphy (11)

Will Laurine learns how to overcome obstacles through running

As the melodic country ballads come to an end in his headphones, Will Laurine (9) positions himself on a line of white, painted grass to take off. Everything comes to a complete standstill. With a bang, Will’s shoes forms an imprint into the ground. His shoes continues to make imprints until he reaches his end destination.

When Will’s cognitive abilities kicked in at the age of 3, he tried sports ranging from soccer to football. He was always chasing something, from another kid to a ball. He was also always the fastest kid in any sport he tried.

“My parents had me join [cross country] because I was such an active kid,” Will said.“They were like,‘Let’s see if we can tire him out,’ and I ended up liking it from there on. I kept doing it every year.”

Will ran at races organized by the Jefferson County Youth Association and joined races at Lone Dell Elementary School when he was in second grade. Kristen Katz, the Jefferson County Youth Association organizer, was one of the reasons that Will started running.

“He was such a fast kid that he would just go,” Katz said. “If I’m not [mistaken], there was one meet where Will may have lost a shoe while he was running and Will finished.”

Going into running, Will had no expectations of being the fastest or having the most endurance. That all changed by third grade. Will decided to take running to the next level. He began to be able to run with sixth graders and was able to showcase his hard work.

“We just remember one of the parents saying, ‘Don’t let that second grader beat you,’ and the kid responded with ‘Mom, [he’s] just so fast,’” Will’s father Joseph Laurine said. “That was one of the moments when the people around him realized that he had something special.”

From third to sixth grade, Will progressively took running more seriously. In seventh grade, Will made it to the Junior Olympics in Greensboro, North Carolina. Will competed in the 13-year-old Pentathlon. During the 1500 meter race, he suffered a lower body injury.

“My hamstring gave out,” Will said. “I got hamstring tendinitis and it regressed me. I haven’t been able to get back into the group that I was in [a] few years ago.”

Will had trouble keeping his mind off of physical movement because he wanted to run like he did prior to the injury. He was unable to think about anything else.

“I had to get something wrapped around my leg and was told I wasn’t allowed to run,” Will said. “I could walk up the stairs, but [my dad said] I couldn’t go up to them multiple times a day. I didn’t listen to it. I physically couldn’t do it. There was a lot of video game playing. It was just anything I could do to get my mind off of moving.”

Will tried to back into running about three months after his hamstring tendinitis injury. Post-recovery, he found that his running was no longer at the level he wanted.

“I was mentally annoyed with myself,” Will said. “I just wanted to stop. I wanted to give up. [In seventh grade, the Junior Olympics was a] difficult race because mentally I just lost everything. I lost all the work I had done for the year before. I haven’t completely bounced back from it.”

In 2023, Will started regaining confidence in his running abilities. In Junior Olympics 2023, he did the multiples — a type of track event consisting of a high jump, long jump, shot put, 100 meter hurdles and 1500 meter race — and placed sixth in the nation for his age group. In fall of 2023, Will participated in cross country nationals and placed eighth in the nation in his age group.

“He has trained with collegiate runners,” Joseph said. “Post-collegiate professional runners have come and trained with him and some practices. They can’t maintain the pace and the reps that he can a lot of the time.”

For Will, hair ties are an essential. While they work to keep hair out of his face while he runs, Will’s hair ties have an ulterior motive: the amusement of his teammates.

“The first time I saw it, I thought it was funny,” Taylor Gase (10) said. “The way he puts up it looks like an unicorn.”

A staple that Will wears outside of running is his cowboy boots. The boots were more of a practical item when Will was growing up on a farm in the countryside.

“We had four acres and we had always been working and moving stuff,” Will said. “It was just easier to wear [cowboy boots] than cleaner shoes every day.”

When Will is preparing for the next meet, he often does fartlek training. Fartlek training is a Swedish technique that means “speed play,” and works on interval training.

“A fartlek is one minute on and two minutes off,” Will said. “Or two minutes on and three minutes off, or [a] version of that. Some people do 90 seconds on and 30 seconds off [but] that’s the college level workout.”

Will was able to transition to the high school cross country environment smoothly because he was able to find a supportive community. When Will arrived he was appreciative of the kindness and lightheartedness of his teammates during workouts, meets and runs.

“You’ll never know what’s going to happen,” Will said. “Even if we don’t run together, there’s going to be [a] comment [or] something odd. It’s always going to be funny. There’s going to be a joke. There’s going to be something that you’ll think about for the rest of the day.”

"Confidence

When Will is running with his friends, he likes to keep his mind busy. A way he does this is by observing his surroundings while he runs and discussing where to go.

“I will zone out because [I am] not paying attention,” Will said. “Sometimes we’re exploring and trying to find new routes. It’s a good thing that [we] get distracted or it’s a bad thing. There’s some ankles rolled because we’re not paying attention as much as we should.”

Will was able to overcome obstacles and become an All American. Being an All American is when an athlete has placed among top athletes in their sport at a national level in their age group. For him though, it was more valuable to be able to facilitate someone else’s love for running.

“So last year in track, [some kids with disabilities] wanted to do [the] relay,” Joseph said. “They were short and Will [took] it on the last leg. He could have been in the faster relay and they probably would’ve gotten first, but he preferred to be in this relay to help those kids out.”

is the

part.

You could be the fastest person ever and if you’re mentally not there, you could run terribly."

Will Laurine (9)

Will gave back by volunteering at the Jefferson County Youth Association where his journey in running started.

“If a kid fell, or if a kid was scared, [or] if a younger kid [felt] defeated, he was there to push them,” Katz said. “He was always that cheerleader to help everyone else.”

Will’s goal for high school running is to make it to state all four years of his high school career. Beyond high school, Will wants to continue to run purely for the love of the sport, whether that means running collegiately or not.

“I don’t know if I want to run in college, but if I go to college, I will definitely probably run in [college] for scholarships,” Will said. “It’s important to want to run because if you don’t want to run, you won’t ever be as good as you would be if you want to run.”

Captions: Will Laurine (9) runs during the Forest Park Cross Country Festival Sept.14. He placed 4th during the varsity white race. “We were trying to beat each other on the turn and [we] lost our footing,” Will said. “I was like, ‘I have to get up before him or he will beat me by a good amount.’ [I wanted to] finish the race, I’m not stopping [now].” Photo by Harper Buxner. (on page 24)

Wearing their sunglasses, Will runs in a triangle formation with Caden Wheeler (12) and Luke Ye (11) at Ladue High School. “I was training one day and [Caden and Luke] were there,” Will said. “So we started running together, since we are both trying to achieve around the same thing. I kind of integrated [into] their friend group.” Photos by Vincent Hsiao. (on page 27)

Will stares ahead while standing in Ladue High School’s stadium. He wore his signature cowboy boots, which he regularly wears outside of running. “[Cowboy boots are] what I grew up with most of the time,” Will said. Photos by Vincent Hsiao. (on page 27)

Kelly Bian strengthens her bond with Chinese culture through lion dancing

Acrowd gathers on the festive occasion of Chinese New Year, awaiting the performance of a traditional lion dance. This captivating dance is meant to bring good fortune for the upcoming year. Suddenly, a large and colorful lion costume sways onto the stage, leaving the audience amazed and intrigued. Children gaze at the colossal creature, and as it shakes its head, some are startled, while others are overcome with laughter. Guiding this motion is Kelly Bian (11), the head of the lion.

Before performances like these, Bian and her team must examine the location of the act. With this information, the lion dancing team determines what techniques will be utilized in their intricate and precise routine.

“[The location] really dictates what we’re going to do for our performance,” Bian said. “If it’s a smaller area, we have some activities. If it’s bigger, we go out to the audience and interact with other people.”

When the show begins, Bian confidently performs as the head of the lion. She particularly takes joy in engaging with the crowd, who tend to react in numerous ways.

“I don’t really find it super nerve-wracking,” Bian said. “It’s just like any other practice. When it comes to audience interaction, that’s where I find lion dancing to be really fulfilling and fun.”

Bian has learned about a number of traditions that are a part of lion dancing, which she incorporates in her performances. These customs have a major role in the dance and signify prevalent beliefs in Chinese culture.

“Some new things I learned about my culture is the way instruments and traditions interact and the importance of these traditions,” Bian said. “For example, in mostly all lion dancing [performances], you’re supposed to have something called ‘eating the lettuce.’ In this part of the routine, the lion picks up lettuce, shreds it and throws it out to the crowd. This [symbolizes] getting rich in Chinese.”

Along with acquiring knowledge about customs, Bian has been mentored in lion dancing by a sifu – her teacher –and her sihings – meaning “older brothers” in Cantonese. She met her instructors at the St. Louis Chinese Language School, where she practices lion dance. Over time, one of her sihings, Erick Lynn, has identified Bian’s improvement in the communicational aspect of the dance.

“When Kelly first started to train with us, [she] was very quiet,” Lynn said. “As she started to learn more, she became very outspoken.”

This is Bian’s second year as a captain of the lion dancing team of STLCLS. Due to this, Lynn presumes that Bian will be able to employ her experience with directing the team in real world circumstances.

Bian’s contributions to the team extend further than her position as captain, such as assisting her novice teammates in getting the hang of things. Moreover, she has the responsibility of handling one of the main parts of the lion.

“Kelly has been both a tail and a head,” fellow lion dancer Garon Agrawal (12) said. “Currently, she’s a head, and she contributes a lot to the team by helping them in performances. She has a good influence in helping the younger, newer members.”

However, Bian was not always proficient at her craft. Due to an initial lack of experience and knowledge about anything related to lion dance, she had a rough start.

“I grew up with [lion dancing], but I didn’t understand the significance of it,” Bian said. “At the time, I wasn’t physically active, so I was super bad at it.”

Since then, Bian has improved in many ways. Lynn credits Bian with being present during practices and using criticism from teachers to grasp concepts quickly.

“You don’t have to tell Kelly to do something over and over and over again,” Lynn said. “Kelly will do it, take notes and teach people around her as well.”

Although Bian started lion dancing in eighth grade simply for fun, she soon realized that the activity became her passion. This encouraged her to gain beneficial life skills and a deeper understanding of her culture.

“I am really grateful that I started [lion dancing],” Bian said. “It made me connect more to my Chinese culture and value it a lot more. I also learned a lot about perseverance, how to communicate with people and general leadership.”

Lion dancing has fortified Bian’s identity by granting her access to Chinese folk traditions. She is involved in her culture in many respects, but lion dancing gives her an opportunity to share it with others.

“I feel like I’m [more strongly] connected to my Chinese culture,” Bian said. “[There are] many ways I interact with my Chinese culture. I eat Chinese food, I go to Chinese school every Sunday and I speak Chinese. Lion dancing is a way for me to interact with my culture in a physical way, while giving back to the community and spreading my culture.”

Captions: Kelly Bian (11) stands with the head of her lion costume, which denotes good fortune in Chinese culture. Lion dancing has provided Bian with an opportunity to get more in touch with her ethnic roots. “[Lion dancing has] helped [Bian] connect with her culture and [find] that community and people she can talk to,” Garon Agrawal (12) said. Photo by Vincent Hsiao. (on page 29)

“The role of [being the captain and] being able to step into that leadership role will help in [Bian’s] role at school, and then in college and work as well,” Lynn said. ID

Bian performs at a various events as the head of the lion. Bian enjoys allowing the audience to pet the lion and dancing with her teammates. “After being part of lion dancing for four years, the team has become like family to me,” Bian said. “The support we share during practices [and] before performances has created a very strong bond for us.” Photos courtesy of STLCLS. (on page 31)

Hamilton uses his past career as a lawyer to inspire his teaching and coaching

High School Musical” is a cult classic that captures the beautiful story of a man burdened with a choice. He has to choose between sports and theater, ultimately deciding both can exist in the same person. This story demonstrates how one person can enjoy what are sometimes considered conflicting hobbies. The concluding lesson leads us all to examine what society has deemed as ‘right.’ Enter science teacher Adam Hamilton: a man who took the lesson of “High School Musical” to heart and is now living a life that would make Troy Bolton proud. By finding a way to balance his teaching and coaching, Hamtilon tries to be a positive influence to his students and players.

Hamilton started teaching at Ladue High School two years ago. With him, he brought his previous experience as a teacher, a lawyer, a football coach and a man raised in a vastly different school environment.

“It was, ‘Sit down, be quiet, do the work,’” Hamilton said. “You were told you were smart when you got great grades. There was very little thought to the type of school work I did growing up.”

Despite the different learning environment Hamilton grew up in, he considers his family to be a major influence to his current teaching style. Hamilton’s mother managed the business end of a school, meaning he was able to see firsthand her relationship and connection with the students.

“The kids all knew her,” Hamilton said. “She built relationships with them, and kids could come to her when they had a problem. That influenced me to see that being an educator was more about connecting with kids than it was about knowing the subject best.”

Hamilton’s experience with school flipped once he attended University of Missouri School of Law. This change in environment largely contributed to the way he views both learning and teaching today.

“I didn’t learn how to think, especially think on my feet, until I got thrown into law school,” Hamilton said. “They take 150 human beings who are all incredibly intelligent [and] highly motivated, and you’re competing against one another for jobs, internships [and] clerkships. You’re directly ranked against one another; it’s a high-stress environment.”

Hamilton’s experiences while at law school didn’t just teach him a different way to learn, it also taught him a different way to teach. The quick pace and on-your-feet style of learning in law school classes are reflected in Hamilton’s teaching style while in his classroom.

“We come in with a plan,” Hamilton said. “But kid number one may have had a bad day. Kid number two may be having a great day. How do I adapt my plan to get the most out of those kids? That was really a lot of the trial work that I had, learning how to think on my feet, learning how to process information in real time and come up with answers.”

Just as Hamilton gained influence from his time as a lawyer, he looks to his time as a football coach as another place to draw inspiration for his personal attitude when it comes to teaching and supporting his students.

“I coach and teach kids before I teach science; meaning my job is to [use] science as a tool to help you become the best version of yourself,” Hamilton said. “I want to teach you that science is a great process to learn how to solve complex problems that have uncertain answers.[Such as] what house to buy, what car to buy, what college to go to. The process of science will help you make the best possible decision in those things.”

Hamilton’s father was a baseball coach when he was a kid. Growing up around his father’s coaching style helped him develop into the coach and teacher he is today.

“[My father] coached all my baseball teams,” Hamilton said. “We would never get the best athletes on our teams, but my dad would just grind like crazy to figure out how to make them better. We were never the most talented, but we always made the most growth. Seeing my dad say, ‘I don’t care where you are, I’m going to help you get to where you want to go,’ [that] really influenced what I want to be as a teacher.”

Hamilton’s passion for coaching doesn’t stop at high school sports. He recently began coaching for St. Louis Slam, an adult women’s football league.

“I was asked to help coach and it’s been an awesome experience,” Hamilton said. “For the first time in my life I’m coaching adults. It’s the first time in my life I’m coaching women, and I have just fallen head-over-heels in love with trying to help these amazing athletes become the best versions of themselves.”

I do need to push [my students] or things are getting tough, [they] know that I’ve made a connection and [I] care about [them] beyond just [their] grade.”

Hamilton’s passion for teaching stems from his love for his students. Behind every decision he makes in his classroom, his students’ best interests are at the forefront.

“I’m one of those crazy individuals who wakes up every day and I’m like, ‘Dude, I get to do this job,’” Hamilton said. “I want to try to be the person I needed when I was that age, because nobody understood me when I was that age. The idea of being a football player who did theater, I didn’t fit in either group. I like trying to find the kids that need help and figure out how [we can] help them.”

Hamilton doesn’t only have a positive influence on his students, but his coworkers as well. Science teacher Ben Nims works beside Hamilton in the science department.

“When you first meet him, he’s very friendly,” Nims said. “You can tell he’s very genuine, and he’s a very easy person to connect with right away. He shakes your hand, he looks you in the eye and he’s just easy to talk to.”

Hamilton sees his job as more than just an opportunity to teach science. He tries to help each student that enters his class, especially when it comes to their mental health.

"Unless I win the lottery, I will be here the rest of my career."

Adam Hamilton science teacher

Hamilton brings the same holistic mentality when it comes to coaching adults. His passion behind teaching is similarly seen in his time with this league.

“We won our first ever national championship this summer,” Hamilton said. “As we’re walking off the field, a group of high school boys stopped my female athletes and were asking them for [their] autographs. That’s such a big deal to watch these amazing athletes get recognized for their dedication, their sacrifice, their hard work, the mental and physical beating that this particular sport puts on you, and to see them rise to the pinnacle of being the best at what they do.”

Hamilton’s passion for teaching and coaching leads him to try and make strong connections with all of his students.

“I try to get to know my students in terms of what motivates them, what are their interests and take a genuine interest in those things,” Hamilton said. “I’m a learner. I love to learn things. So, if it’s something we have in common, great. That’s a way that we can have a connection. So when

“When I was growing up we didn’t talk about mental health,” Hamilton said. “My family has a very deep history of mental struggles, and one of the things I’ve learned real quick about being in this profession is young men need to hear from grown men. It’s okay to not be okay. It’s not okay to not tell someone.”

Having been brought up in an environment that doesn’t pay much attention to mental health, Hamilton has made it his goal to insure his students never feel that their mental health is ignored.

“My mother suffered from anxiety very badly and [she] was of a generation that didn’t get help,” Hamilton said. “I saw it affect her personality. I’ve been very outspoken about my own journey with anxiety. I have no problem admitting that when I need to, I go see a therapist, because it’s my mental health coach. I tell people all the time, if I wanted to teach somebody how to throw a curveball, I can’t do it, because I’m not a baseball coach. I’m gonna go find a baseball coach to teach them. So why do we not want to receive mental health coaching?”

Caption: Science teacher Adam Hamilton stands on the field as he prepares his players for their match against Hazelwood highschool Sept. 27. Hamilton has been working at Ladue for the past two years both as a teacher and as a football coach. “There is a desire to do what’s best for kids on both sides of the ball,” Hamilton said. “And I don’t mean both sides of the ball with football, I mean with academics and athletics.” (on pages 32-34) ID

The usual smell of cigarette smoke permeates the hot, humid streets of Mumbai, India, a scent oddly comforting to a then-16 Reva Shetty (12). It lingers on her clothing as she evades an entourage of incoming traffic and rogue street food stands from the comfort of her car. The windows are rolled down, and a sense of nostalgia washes over her as she takes in the chaotic scenery one last time. In just a few hours, her experiences will become memories, the streets and views she has known for the past 14 years, inaccessible. Moonlight gently illuminates the streams of nearby water fountains, their rhythmic beating muffling her internal apprehension. She finally arrives inside the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport, where she’s greeted by the structure’s characteristically tall, yet familiar, coffered walls. Reva is headed for the United States, a location she frequents every summer. This time, however, she is staying. Permanently.

In the spring of 2023, Reva made the decision to move to St. Louis from Mumbai, India with aspirations of pursuing post-secondary education in the United States. However, St. Louis is not completely foreign to her.

“I was actually born in St. Louis,” Reva said. “My parents got divorced when I was two. My mom got custody, so I moved back to India, [where] she’s originally from.”

Coming to this conclusion was simple enough — settling in and adjusting to her new life proved more difficult.

“I didn’t know anyone here, so starting a new life was a bit jarring, especially with making friends at school,” Reva said. “My first days in St. Louis were [spent] mainly missing my routine back home and hating the time difference.”

In fact, the 11 hour time difference between St. Louis and Mumbai was initially a significant barrier for Reva and her childhood friend from India, Isha Waingankar. Now seniors, they have known each other since fifth grade.

“Growing up with Reva was one of the best parts of my school life,” Waingankar said. “She gets me, and there was never an awkward phase in our friendship. We spent almost every day together because of school and tutoring.”

Though maintaining contact is still occasionally challenging, the two friends have made it work.

“We try to connect every couple of days and text throughout the day to stay in touch,” Waingankar said. “Both of us are late sleepers, so we can talk for most of the day without issues. We text about random things, keeping each other updated on everything, big or small.”

Amidst chaotic adjustments and confusion was excitement: Vilaas Shetty, Reva’s father, was glad to reunite with his daughter long-term. Their contact had previously remained limited to visits during vacations or video calls.

“I was thrilled when [Reva] said she was interested in

coming here to finish her school,” Vilaas said. “She would come [to the U.S.] for about six weeks to spend the summer and had been doing that for years. I’ve always wanted her to live here. I just never thought it would happen.”

Initially, no one could say for certain how Reva was going to adjust, but her versatility, adaptability and friendliness expedited the process exponentially.

“[Reva] made friends very fast,” Vilaas said. “She was ready and willing to just try new things [and] meet new people. She found activities that she really liked and people with common interests.”

Moving to another school or state is often a commonality and even a unifier for many. Virtually uprooting your entire life, including the existing customs, traditions and values you have known and practiced for years, is not.

“[Reva has] had to adapt to everything: the type of food people eat here, what they like to do and how they talk,” Vilaas said. “She’s fluent in English, but that’s different from hearing people talk with an American accent or at high speeds.”

Though Reva emphasized keeping an open mind to ensure a smooth-sailing transition, she still needed downtime to familiarize herself with aspects of American education and culture that still felt foreign to her.

“Here, you guys are more extracurricular focused. [In India], we’re more academically focused and everything revolves around your studies,” Reva said. “At some levels, it was hard [adjusting], but it was also a lot easier because I realized that I didn’t have to be as focused on my grades.”

Beyond the academic sector, Reva had yet to fully immerse herself in the American lifestyle. Fortunately, her newfound friends were able to introduce her to their favorite pastimes and events, both day-to-day and exciting alike.

“[My friends helped me with] absolutely mundane stuff like going out to get a bagel because I had never tried a bagel before,” Reva said. “[Also like], going to football games, dances and arcades — just all the American experiences that I’ve seen in movies.”

Besides technical and habitual differences, there was an environmental learning curve for Reva.

“She grew up in a city of over 20 million people. This is rural by comparison,” Vilaas said. “That city also never sleeps. Over here, we’re all going to bed and it’s 9 or 10 at night, so that took her some getting used to as well.”

In addition to her father, Reva lives with her grandparents. Despite periodic cultural and generational divergences, they are able to connect over shared interests.

“My grandmom and I bond over a lot of things. I introduced her to ‘Hamilton,’ the musical,” Reva said. “We sing a lot of ‘Hamilton,’ but my grandfather, we bond over Bollywood music.”

Alongside her move to the U.S., Reva also transported a decade’s worth of passion for and experience with Bollywood Dance, a vibrant style of Indian dancing that combines traditional and contemporary western elements.

“Growing up in an Indian environment, every festival you dance,” Reva said. “Bollywood music and Bollywood in general is a huge part of our culture. I danced a lot as a kid, and so I dance a lot now as well.”

Waingankar has seen Reva’s evolution from their school years to the present, and she could not be prouder of her childhood friend’s accomplishments in dance.

“We loved dancing together during school concerts, farewells and DJ nights on school trips,” Waingankar said. “Reva’s dancing style is extremely graceful. She dances with confidence and passion.”

Now co-president of Bollywood Dance Club, her affinity for the club dates back to her junior year.

“I joined because it seemed fun and I like Bollywood dance,” Reva said. “The presidents at the time both realized that I know a lot more about [it]. They were like, ‘You should be president,’ and I was like, ‘I would actually love to.’”

Reva has since assumed an integral role in leadership by choreographing dances for the Bollywood Dance Club, producing routines for Passport Night at Old Bonhomme Elementary School, Spoede Elementary School and Conway Elementary School, as well as International Week and Rams Around the World at Ladue High School.

“We do different choreographies for all of them,” Reva said. “It gets boring after a while if you’re doing the same one for every single thing, and the rehearsals become redundant. It’s also more fun to expose [the audience] to different songs.”

Overall, arranging routines for the Bollywood Dance Club, staying connected to the community and continuing dance has helped Reva regain a sense of unity and peace.

“I feel the most at home when I’m dancing,” Reva said. “I have confidence in my group, myself and what everybody does for the dance.”

Captions: Reva Shetty (12) showcases photos from her childhood and trip to India this past summer. She visited her mom, family and friends. “[It] was a bit nostalgic going through the streets as a different person because my life has changed since I’ve come here,” Reva said. Photos courtesy of Reva Shetty. (on pages 39-41)

Reva poses in front of her home and address plaque. After reuniting with her father and grandparents, she has made many new memories and retained her culture. “We have a lot of Indian cooking going on,” Reva said. “I also like telling people about Indian food, mainly because that’s something that really connects me to [Mumbai].”

Photos by Vincent Hsiao. (on pages 40-41)

"[She’s had to] learn how to live in two diferent worlds."

Vilaas Shetty, father

Gabe Ponce represents his culture

The nerves before stepping on the mat, heart racing, fists clenched with adrenaline. Face to face with the opponent, analyzing, reading and preparing. The sound of the bell marks the beginning and the end; the beginning of the fight and the end of all distraction. No homework, no school, no other obligations; just desires and goals.

Gabe Ponce (12) has been boxing for almost seven years. For five of those, he’s been training at The Boxing Therapy gym in St. Charles, Missouri.

“I started back in sixth grade,” Gabe said. “There was a summer where I kind of just did nothing and I got pretty fat. So my mom told me I had to start doing some exercise. We had a boxing bag in the basement that I never really used, but I started using that.”

Those who know boxing know it’s a never-ending hustle, but not many know what training truly looks like. Gabe is meticulous when it comes to preparation.

“I’ll do four or five rounds shadow boxing,” Gabe said. “Just to warm-up stuff like that. That changes depending on the day. Monday and Wednesday is just conditioning training, stuff like that. Tuesdays and Thursdays are sparring days.”

Sparring is a popular part of training for all boxers. It builds the required experience needed for stepping in the ring. Knowing the basics of boxing and being able to take a punch is a vital tool for all boxers.

“You just take the beating and there’s not much you can do about it,” Gabe said. “It’s just that universal experience for all boxers. At one point, somebody’s just gonna beat you up and you’re gonna be mad. It separates the people from who want to be there and who don’t.”

Sparring builds experience for the fight. Even through taking hits and the pain, Gabe recognizes its worth.

“My nose bled, but I won, and it was the coolest feeling ever,” Gabe said. “To feel that you accomplished something within an eight month time frame, fighting in front of bunch of people you don’t even know, it was a really cool experience.”

Behind the hours of work, the fights and the sparring is none other than Gabe’s father, Jose Ponce. His father has been his trainer since he first began boxing.

“It’s the love of the sport and the love that I have for my son,” Jose said. “I would not have anybody else train him unless I know and I can trust that trainer. Gabriel is training in a style [where] he has an opportunity to really go places because of his ability in the game. That’s why I keep falling in love with it each and every day.”

Those hours of work don’t only include boxing. Despite being a student-boxer, for Gabe, the student always comes first. While he has aspirations for becoming a professional, he prioritizes having a strong academic career.

“I would love to, if the opportunity’s there, to turn profesknow it’s not going to be easy. But I also do want to

make sure that I’m going to a good college. It’ll be tough, but I think it’ll be worth it.”

While boxing is a way for father and son to bond, knowing when to have fun and when to get to work is important to their relationship and their overall dynamic.

“When we’re at the gym, it’s almost like he’s not even my dad,” Gabe said. “He’s 100% real with me. If I have a bad day, he’ll tell me. If I have a good day, he’ll tell me. He’s just always pushing me.”

After training multiple successful fighters, Jose treats his son no differently. Jose keeps gym and home life separate. Jose does have good intentions by separating those two lives and holding a high standard.

“I’m a lot harder on my son than I am on other fighters,” Jose said. “The reason why is because I know my son’s ability, I know what he has and I train him harder and stronger. I’m harder on him, but I know that he can understand where I’m coming from. I know that he can handle it.”

Jose is no stranger to the ring, with an impressive and lengthy career spanning almost 40 years. He has studied numerous styles of fighting in front of thousands of people.

“I started at the age of 10 years old in Los Angeles at the Boys and Girls Club,” Jose said. “I was taken there by a cousin of mine many moons ago and I enjoyed it. It was very nerve-wracking at first, because as a new guy in the sport, as a new kid, you don’t know what to expect, but I found something in the sport that I really liked. And to me, it was that rush.”

Gabe describes his first hand experience with using boxing to represent his family and background. The ambience and the support from those around him was a key factor is his victory. Not many young people have the chance to carry on a deep rooted legacy as Gabe did.

“I fought on Cinco de Mayo and that was such really cool event,” Gabe said. “I had Folklorico, I had mariachi music in the background, I had my Sombrero, my poncho. It was really powerful to fight on that day and represent my country.”

While he doesn’t have many fights under his belt, Gabe has still made a name for himself as a worthy competitor in the boxing community. As of October 2024, his record is 5-2, but he has multiple fights scheduled for later this year.

“I’ve had seven amateur fights so far,” Gabe said. “In my opinion, my record should have been six and one. I did get robbed in the Golden Gloves, but I can’t change that. So it is what it is. I’ve learned to live with that. I’ve had seven fights which I know doesn’t seem like a lot, but, I’ve been training super hard. I train with guys that have 20-30, plus fights they’re all bigger than me. I get work with them and I give them good work too. I know for a fact I have the ability.”

"I’m a lot harder on my son than I am on other fighters."

Jose Ponce, father

Jose quickly grew out of being a new kid to boxing. His love for the sport carried him further and further into his fighting career over the years.

“I fought in the amateur program for many years,” Jose said. “I fought in a professional environment for even longer, from boxing to professional kickboxing and Muay Thai.”

Like many backstories, there is an influence of culture. To Gabe and his family, boxing is an important part of their heritage. Not just in the fighting itself, but the representation that it provides.

“We came from that culture all the way from the Aztec culture,” Jose said. “Mexico has pride in its boxing community [and] the legacy that it leaves behind and Gabriel sees that. This is his second time fighting on Mexican Independence Day. What other amateur in St. Louis with the Hispanic background has that opportunity? [I], for example, my entire career never have fought on Mexican Independence Day. And that to me was my ultimate goal in boxing and in my life.”

Former boxer, coach and owner of Boxing Therapy, Jose Jones holds high praise for Gabe. He is a fmaily friend of the Ponces.

“He has come a long way with not only in boxing but life in general,” Jones said.

“When it comes to boxing, you can tell that this young man has grown so much with his technique and discipline. He’s a man that enjoys the sport. He breathes boxing, and he enjoys boxing as a whole.”

Captions: Gabe Ponce (12) and his father Jose Ponce begin their training in the ring with combo training on the focus-mitt. His father has trained countless professional fighters in St. Louis. “Gabriel is surrounded by that type of environment where he sees what that top level looks like,” said Jose Ponce.(on page 42-43)

Gabe gets his hands wrapped by his father before his training session. Wrapping is a daily ritual before stepping into the ring for protection. “I like having my dad as my coach better than another person,” Gabe said. (on page 45)

Gabe ends each session with a cool down routine. Each session is short but they’re non-stop work and training with zero breaks. “most people see boxing as like a sport where it’s all dirty and people are just fighting, but once you really understand the sport more, it’s more about technique” Gabe said. (on page 45)

Red inflatable gloves hang from the ceiling. Countless flags also hang to represent the many backgrounds that enter the gym. “I wanted to create a program that can actually help kids with their life,” Jose Jones said. (on page 45) ID

Horseback riding through the Californian mountainsides led to a sight that is all too common: trees completely burnt, lying lifeless, while people just pass by paying no attention to them. For a young Sophie Cowlen (10), this sight reminded her of another time in Colorado when she was staring through her window at another empty mountainside. No life, no homes.

“It’s really sad knowing that all those places could still have been flourishing today if it wasn’t for the impact of climate change,” Sophie said.

This experience inspired her to protect the environment in and outside of school through various activities.

In January 2024, Sophie started an Instagram account on sustainability to educate people on a wider scale. The account is fairly new, but she strives to deliver globaly impactful content on what she’s most passionate about.

“I basically post photos and videos about how to be more sustainable,” Sophie said. “So about [things] like sustainable fashion and limiting your CO2 emissions. I really want to educate, especially young people, on the climate crisis.”

Although Sophie likes to project the big picture on sustainability, she prefers to focus her content on sustainable fashion. To her, social media seemed to be the perfect place to bring awarness to teens all over the world.

“I’m constantly bombarded on social media with over consumption and things that are so unsustainable, especially targeted towards teens, which is why I’m so passionate about that online,” Sophie said.

To further her connection to the environment, Sophie enrolled in the Sustainable Investigations class taught by social studies teacher Kelley Krejnik. Sophie also believes that this class is a great opportunity for her to get involved with the environment and obtain real-life experience.

“Even if [someone] doesn’t go into sustainability as a career, it’s still going to affect their lives with climate change,” Sophie said. “It’s something that we all need to learn, and I love that it is part of the curriculum.”

Seated in a class that reflects her passion, the interest and enthusiasm Sophie demonstrates along with her contributions are often noticed by Krejnik.

“[When] Sophie signed up, she was very eager to take Sustainable Investigations as a sophomore because she has a lot of passion to tackle the challenges with our environment and climate change,” Krejnik said. “She has shown enthusiasm for all of the different topics that we’re learning in the class.”

Out of the various topics that Sophie was learning in this class, the scientific reasons behind many occurrences in the environment, such as the ozone layer, coral bleaching, and hurricanes, interest her the most.

“We’ve learned about the growing strength of hurricanes due to warming waters and numerous other things,” Sophie said. “I feel like I have a much more scientific understanding of a lot of modern climate issues.”

Not only does Sophie focus on topics in class, but she also worked on projects that promote sustainable practices and make the campus a hotbed for sustainability.

“[Sophie] is collaborating on a project to help improve the sustainability of our campus,” Krejnik said. “She’s focused her attention on our habits, behaviors and materials in the lunchroom.”

Along with other coursework and projects Sophie contributes to in the sustainable investigations class, she also feels a deep connection encouraging her to educate herself and contribute to the learning of others in the class.

“When I go in there, I feel like there’s so much I want to say and so much more to do,” Sophie said. “Every conversation that we have in there I feel so passionate about because I feel like I can really contribute to what we’re learning about.”

Adding to her involvement in school, Sophie became a member of the Student Action for a Greener Earth (SAGE) Club her freshman year. Jumping right into this club, she contributed to the native pollinator garden project.