6 minute read

CAMPUS VIEW

Advertisement

Stories and photos by Tim Cohrs

Preserving history’s back pages

Gray Library’s Special Collections houses Lamar, SETX archives

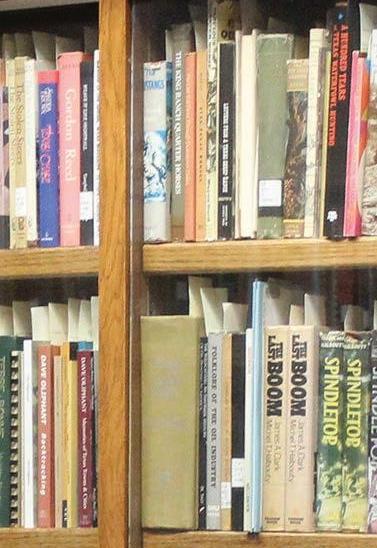

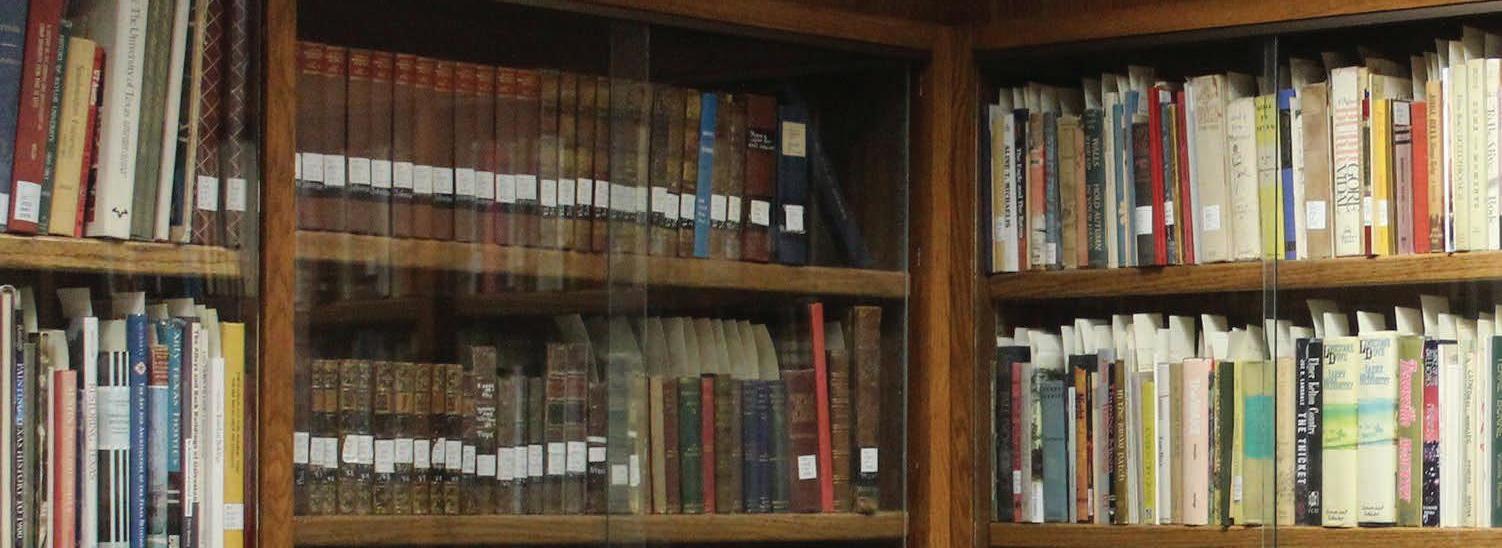

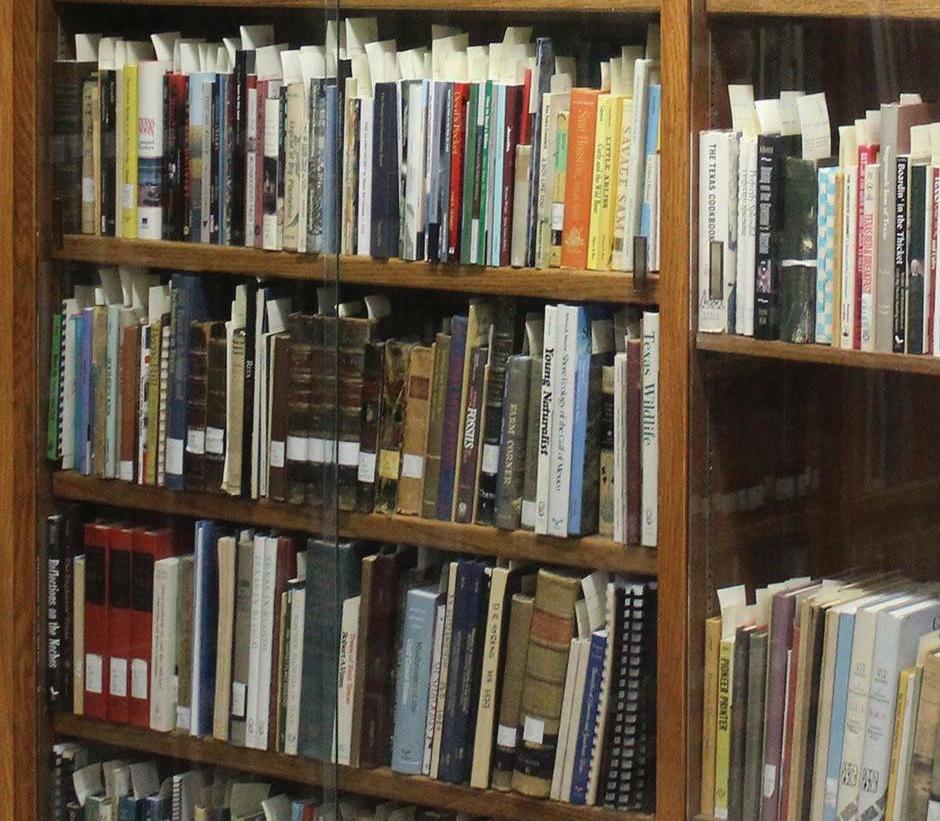

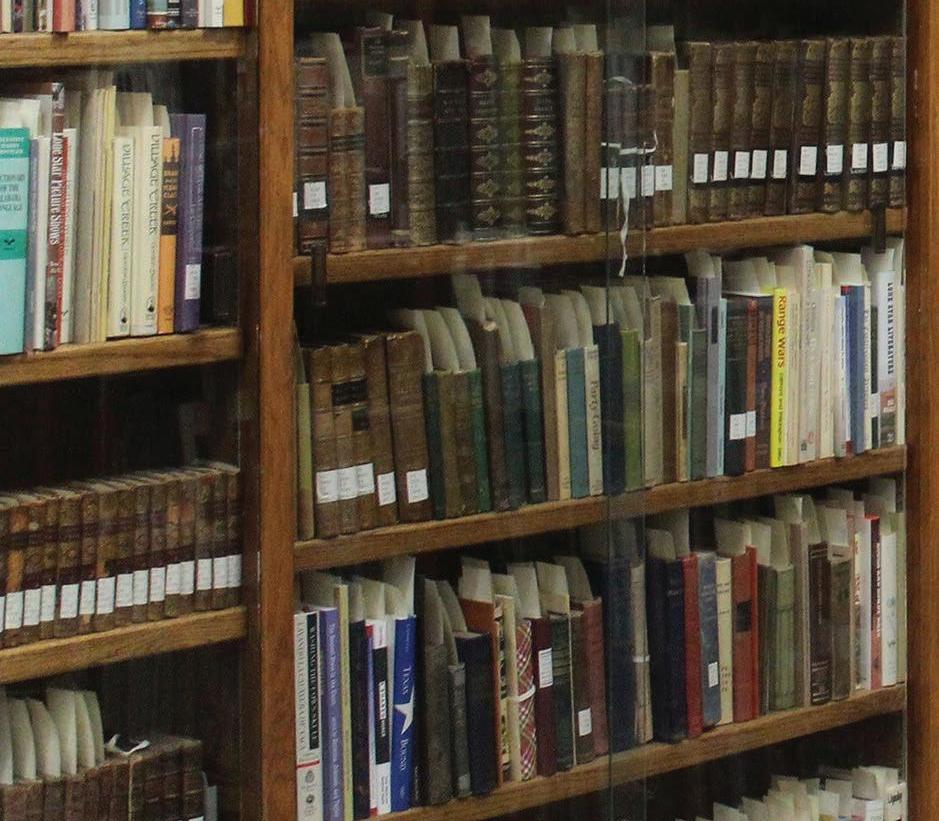

When most people exit the elevator on Gray Library’s seventh floor, they often turn left to the study floor without thinking. But if one turns right, one enters a world of more than 20,000 books, artifacts and memorabilia.

Lamar University’s special collections department is a repository for more than a million manuscripts, photos, books and other historical documents, not only regarding Lamar history, but also Southeast Texas and world history.

The department was founded during former LU president John Gray’s second tenure as president, and the effort was headed by two librarians, Maxine Johnston and Lois Parker.

Special collections was inspired by the Browning Collection at Baylor University in Waco, which Gray visited and admired, Penny Clark, special collections librarian, said. He asked then library director Maxine Johnston if Lamar could build a similar collection to give the library visibility and attract scholars.

However, the library did not have the funding, personnel and resources to develop such a collection. But there was a ready-made source of interest already in place.

“(Johnston) and Lois Parker had been

working on collecting things on the Big Thicket,” Clark said. “They had both been very active in the preservation of the Big Thicket. This was something they really had a passion for.”

The Big Thicket archive was the starting point around which the special collections department was built.

“The Big Thicket is one of our big calling cards,” Clark said. “It is one of the things that makes us distinctive. One of the things that (Johnston) did, was she would lobby very hard for the creation of a Big Thicket National Park. It did not become a National Park, it became a National Reserve, which is somewhat different. It was the first National Reserve in the United States.”

One of the department’s largest collections was donated in 1970. The Larry Jene Fisher Collection contains negatives and scrapbooks documenting the destruction and raising awareness of the Big Thicket. It furthered the movement to make Big Thicket a National Preserve.

“(Fisher) was an outsider — they call him the Renaissance man of East Texas,” Clark said. “There are scrapbooks, but it’s primarily a collection of negatives. We used some grant money (and) we have digitized the collection.”

The department recently acquired the Wanda A. Landrey collection, which contains stories Landrey heard from residents of the Southeast Texas community regarding the Big Thicket.

“Wanda grew up in Beaumont, but her people were from the Big Thicket,” Clark said. “When she was a little tiny girl — you know how most parents might tell their kids fairy tales at night? — her dad told her stories of outlaws of the Big Thicket. So anyway, she fell on pretty much the traditional route. She went to college, she had children. She taught school for a while, but then she came back and she got her master’s in history at Lamar. Wanda has written five or six local history books. She had cassette tapes, which we had professionally digitized, and she also had transcripts made of these oral histories.

“She would spend several days a week for years going out and interviewing old people in the community, and they’re really fascinating. They give us the social history. They talk about what it was like — one woman talked about how she was born in an oilfield town and how dangerous it was that a lot of the gases coming off the oil wells were dangerous. Some people died, and it was a cost of doing business. Some people got sick.

“One woman talks about how her father — her mother died, and he just leaves her Gray Library’s Special Collections department, le ft, houses more than one million items, including books, pictures and manuscripts. Charlotte Holliman, library associate, bottom left, looks through a book from the Herb and Kate Dishman cookbook collection. The collection, above, contains 1,600 cookbooks from as early as 1501.

there in the oil field town and he assumes some woman will take care of her. You have really good or some terrible things that come up. There’s stories of lynchings, so there’s really everything of life. We’re really blessed to have the Landrey collection.”

Another recent addition to the department is the David P. Lewis Collection. Lewis is a Lamar alumnus, receiving both a bachelor’s and masters degree from the university.

“We recently received a grant to have digitized and uploaded on the portal of Texas history, 750 images from David Lewis’ collection,” Clark said. “David is something I’d never heard of till I came to Lamar — he is a mycologist. In other words, he is a person who studies mushrooms. He has co-authored a book published by the University of Texas press, and has also co-authored 22 scientific publications. He is very, very much a scientist. He’s very meticulous. He has documented a lot of the Big Thicket Association — some of their field trips, some of their Big Thicket days.”

Lewis’ collection also documents the advocates and authors that helped motivate conservation efforts.

— Penny Clark

“It documents some of the interesting people who dedicated years of their life fighting for the Big Thicket, and a woman named Geraldine Watson,” Clark said. “She claimed that she got death threats for her work in the Big Thicket, that if she would go to the grocery store, people would spit on her because of her support of the Big Thicket National Preserve. It was a very controversial thing to do.”

The idea of a preserve was not universally accepted. People feared losing their homes, hunting lands and jobs within the logging industry as a result. The topic of taxes was also part of the fight against making the land nationally protected.

“Some people felt like they were going to lose their homes, that was one of the concerns that made people really touchy,” Clark said. “Well, some people say, ‘You know, our family’s been living here 150 years and you’re not taking our land. Also, there was the concept of the free range — allowing cattle to roam free, allowing hunting. People were afraid — this was East Texas — that they could no longer hunt in this area. They felt like that they would lose a lot of their hunting rights.”

The Big Thicket is home to four of the five carnivorous plants found in North America, plants that eat insects, which Lewis spotlights in his collection.

“When I was a child growing up, I heard they were carnivorous, and I thought, ‘Hmm, would I be walking along and one of the plants make a snack out of me?’” Clark said. “But they just eat insects, luckily.”

Clark also said the reason Lewis studies the mushrooms is because the growth of mushrooms is correlated with a healthy ecology.

Collections — page 22