24 minute read

RECLAMATION

ABUSE OF FAI H

Story package by Olivia Malick

Advertisement

Women share tales of religious oppression, breaking free

For centuries, people have looked to religion for salvation and understanding, seeking a sense of community in their congregations and a sense of purpose.

According to the Pew Research Center, approximately 78 percent of Americans identify with a religion, with 70 percent of that group identifying with some form of Christianity, or religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ.

While religion can be a positive force in a person’s life, it has also been used to justify wars throughout history.

Religion can also serve as a conduit for physical, emotional and spiritual abuse. This is the story of two women who left their oppressive religions.

“Religion disarms people — their guards go down,” Stuart Wright, chair of the LU sociology, social work and criminal justice department, said. “Religion makes claims to speaking for god and having this kind of cosmic order, so people are less likely to put up defenses and use their analytical skills.”

BEGINNINGS

As a child, Eleanor Skelton was taught to believe that she was responsible for the suffering and death of Jesus Christ.

Every year her family would go see The Passion Play, a dramatic portrayal of Jesus’ life, beginning with his birth and ending in a violent recreation of his death.

“I remember going for the first time when I was two and a half,” Skelton, now 31, said. “I remember it being kind of scary, but it wasn’t very graphic yet. He was hung on the cross, but it wasn’t very bloody.”

Skelton said the play became increasingly brutal as she got older. She wasn’t able to even approach the man who portrayed Jesus afterwards because she was afraid that he would think she was responsible for his death. By the time she was nine, the actor who played Jesus was being kicked and spit on, and screamed while he was forcibly nailed to the cross, fake blood cementing the scene in the audience’s minds.

“I was told the message that the man on the cross should’ve been me,” she said. “I was told that when I was bad, I was hurting Jesus.”

Skelton was raised in a fundamentalist Christian household where the interpretation of the Bible was strict and literal.

“A fundamentalist religion is one which tries to reclaim the pure original beliefs of that faith, but I would suggest that those are claims, and not often factual,” Wright said. “(These are) claims that cannot actually be authenticated.

“People’s ideas of originality, sometimes are pieced together in certain ways that take on cultural and political overtones that don’t really have anything to do with the original teachings of the sacred texts, whatever they may be.”

Claire Robertson, Beaumont senior, remembers her mother being religious when she was growing up, but everything changed when her mother remarried to her current husband, when Robertson was 11 years old. He was a member of the United Pentecostal Church and Robertson said it wasn’t a big jump for her mother to convert to his religion.

“I was a preteen and change is really hard at that age,” Robertson, now 24, said. “Between getting a new stepdad, moving houses and changing churches, I threw a bit of a fit. For a couple of years, they had to really strong arm me into attending church at all. But eventually, I was fully a part of the church.

“I attained salvation in the way the UPC views attaining salvation, which is being baptized in the name of Jesus. I was filled with the Holy Spirit with evidence of speaking in other tongues, which is an unknown language to you that comes to you while you pray.

“I repented my sins, of course, and I began living what they call a ‘holiness lifestyle.’ That involved changing the way I dressed, I stopped cutting my hair, I monitored my media intake and started attending youth groups regularly. I really got into it pretty deep and pretty fast. I think because I was young and impressionable, and so much change had happened in my life, I kind of latched on to that as a coping mechanism,

— Claire Robertson

but I genuinely did believe it — I had always had a belief in the Christian God growing up, so it wasn’t a huge leap for me to become part of this church.”

SUBSET OF SOCIETY

Skelton, who was born in Beaumont and spent part of her childhood in Port Neches and Nederland, said her family participated in, but was very much separated from, society. She said that she attended fairly “normal” churches in Texas. Her family moved to western Colorado in 1999, where they attended a small multi-denominational Christian church that was “average.” In 2003, the family moved to Dallas and attended Rockwall Bible Church, which Skelton said was the first “cult” church they attended. In 2006, the family moved to Colorado Springs, which Skelton said is the evangelical Mecca.

“People want to know, were you a part of ‘X’ group?” she said. “Like the fundamentalist Mormons, they’re part of that group their whole lives. They have multiple wives and they live in the desert. People see that and they think cult. The crazy thing is, while we didn’t exactly look like that, a lot of our teachings were very similar.

“It seemed like we were part of normal life — we didn’t go live in the desert with a prophet. We had all of these justifications, ‘We’re different, but it’s OK.’ It took me a really long time to realize we were in a cult.”

Robertson, who left the UPC in January 2020, said that after leaving the church and reading Steve Hassan’s BITE Model of Authoritarian Control, she came to the conclusion that the UPC is a cult. BITE stands for Behavior, Information, Thought and Emotional control.

Wright, who has studied different religious movements and cults, said that there is no one legitimate or valid scholarly definition of a cult.

“There’s probably 50, 60 or 70 scholars around the world who study new or firstgeneration religions, or religions that are on the margins or fringes of societies,” he said. the margins or fringes of societies,” he said. “There are two domains of definitions. If one is speaking theologically from a Christian perspective, I suppose they could use the term to mean a heresy or departure from orthodox tenets of the faith, which is very subjective, of course.

“Sociologically, they run into problems since the definitions turn on a different social science set of assumptions, and there is considerable academic disdain for the word and it lacks coherent and consistent criteria.

“There’s a lot of disdain for the term ‘cult’ because it’s been hijacked by people with other interests. It was hijacked in the 1970s by what we call ‘anti-cult’ groups — some of them might be harmful and some of them, I’d say most of them, are completely benign, so you have to take them on a case-by-case basis.”

Robertson said she didn’t realize how much influence the UPC wielded over her until after she left.

“When I first left, I wasn’t thinking, ‘Oh, I just left a cult,’” she said. “I hadn’t really grasped that idea yet. It wasn’t until I got some distance when I realized how much the church and their ideas had been controlling every single aspect of my life. Not only what I wore and where I went, but the kind of thoughts I allowed myself to entertain, or the people I allowed myself to talk to or the emotions I allowed myself to have — there were things I would stop myself from feeling because I felt like it was sinful. That level of control at every level of my life was so exhausting.”

Neither Skelton’s nor Robertson’s parents grew up in the strict religions they came to know. Wright said there are different pushand-pull factors that lead people to these faiths.

“A pull factor might be they sense a very strong sense of community,” he said. “Sometimes, that community turns into a controlling environment. It doesn’t necessarily have to be but there's a fine line between a tightknit sense of belonging and brotherhood and fellowship, and policing and surveillance — mutual spying on people to report any deviation from the norms.

“I think communities have always struggled with that, the tension between freedom and control.”

TEACHINGS

Skelton was homeschooled in Christianbased education from the age of five until she graduated high school, often hidden away in a room she describes as a closet inside her father’s dentist office.

“Homeschooling wasn’t really popular yet and my parents were convinced that if people found out I was being homeschooled, Child Protective Services was going to come and take me,” she said. “We weren’t required to register with the school district or anything, so it was like nobody knew I existed. That happens to a lot of homeschool kids — we’re under the radar, so there’s no one to really check on you.”

Skelton said she was kept in the room for eight to 10 hours a day, barred from interacting or seeing other children, including those who were her father’s patients.

Skelton followed curriculum published by Abeka (then known as A Beka Book) one of the main publishers of American Christian-based education materials. She watched classes via VHS tapes, and later DVDs.

The history textbooks Skelton studied portrayed figures like Confederate General Robert E. Lee as a hero and reframed other historical events she said.

“My mom had the answer keys, so she would check my quizzes and collect my tests and then send them back to Abeka,” Skelton said. “They would grade you on handwriting

Abuse — page 10

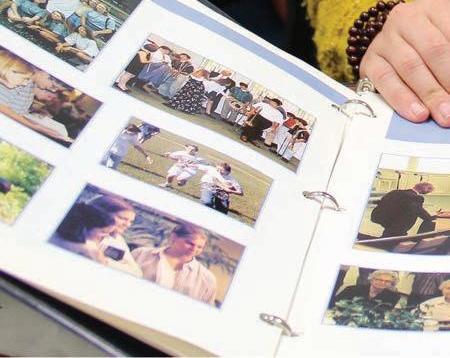

Eleanor Skelton, far left,looks through directories from churches she attended as a child. Skelton and Claire Robertson, cutout, shared their stories of leaving oppressive church groups.

because it was considered to be almost a spiritual thing. We were taught that if you didn’t get As and Bs, you were displeasing God.”

Robertson said she was indoctrinated into the idea of purity culture, which she believes is used to maintain control over people in the church.

“I would define purity culture as the idea that my body has never belonged to me, or my body belongs to God and in the future, it will belong to my husband,” she said. “This idea comes from when Christ died for our sins — he paid the price. So, purity culture is living in a way that exemplifies these ideas of abstinence, modesty and purity in your lifestyle — like staying away from drugs and alcohol because your body is a temple.

“Purity culture has been pretty toxic because naturally, as you grow up, and go through puberty, and get into relationships and fall in love, you want to express yourself, and express yourself romantically. Then you're shackled with this guilt that you've sinned against God, by acting on your own very natural, very human desires. What I think is unhealthy and unnatural is pretending like we are not sexual beings until we get married. And then all of a sudden, you're supposed to have compatible, healthy, open communication and rewarding sex with your partner for life.

“I think that's a breeding ground for potential abuse or for needs not being met by either partner. I think it makes you feel shame for your normal desires.”

Skelton’s parents read books by evangelical Christian author James Dobson, founder of Focus on the Family, whose vision is to, “Redeem families, communities and societies worldwide through Christ.” Skelton said that Dobson’s book, “The Strong-Willed Child,” which recommends corporal punishment to parents so that their children will follow the teachings of God, led her parents to believe that hitting her and her siblings was a way to ensure they were obedient to God.

“Dobson apparently teaches that when your child has a tantrum, you hit them until they stop resisting, so they submit to your will to become a good kid,” Skelton said. “My parents got the impression that you had to beat your child until they stop crying because crying is like rebellion.

“Some of these books have been known for really harsh disciplinary methods. The book, ‘To Train Up a Child,’ by Michael and Debi Pearl, was implicated in the deaths of three children — and they say, ‘Oh, we don’t mean for kids to get hurt or killed.’ Well, you write something like that, and that’s kind of Eleanor Skelton’s family portrait from fall 2002, featuring her father, mother, and two younger siblings whose faces have been covered to respect their privacy.

what you’re encouraging. Maybe you don’t outright say it or want it, but some people are going to take it that way.”

Skelton said she can remember her parents taking turns hitting her from a young age, to the point she could not catch her breath.

“When I was eight or nine, my parents started spanking me with a ping pong paddle and then my parents started to break it,” she said. “The paddle would split and then I would have to buy a new one with my allowance money because my parents said, ‘You made us so mad that we hit you so hard that it broke the paddle.’

“I’m thinking now, as an adult, if you hit your kid hard enough to break a ping pong paddle on them, that’s too hard.”

When the paddle wasn’t hard enough, Skelton said her parents used a belt.

“Sometimes (my dad) would just snap at us if we were misbehaving,” Skelton said. “But other times he would really react. One time I was chasing my sister around the house and he got so mad. He dragged me to the garage and sat me down on a bench. He yelled at me about how I was too old (12) to act that way and then he hit the bench with a belt.

“It hit my arm and left this big U shape. I remember seeing stars it hurt so bad, and not even being able to hear what he was saying anymore because I was so focused on not crying because crying was bad. He told me he meant to hit the bench — I don’t know if I believe him.”

Skelton’s mother made her wear long sleeves to avoid the chance of anyone discovering what had happened. She said anything that could be perceived as disobedience was punished. She recalled the day her two-year old brother was hit by their father for hours just because he cried for their mother.

“I was upstairs doing my home school and I could hear my brother screaming and he wasn’t stopping,” she said. “I tried to go knock on the door because I thought something was medically wrong. My dad opens the door and says, ‘I'm dealing with something. Close the door.’

“I went upstairs, and my mother was crying in the master bedroom. I asked her what was wrong and she said, ‘I can’t take this anymore.’ I could hear my dad beating my brother with the ping pong paddle and I asked my mom to make him stop, but she wouldn’t. I wanted to call the police. That was when I started to think that something was really wrong with my family.”

Skelton’s mother wouldn’t call the police and her brother eventually stopped crying after passing out from exhaustion. Skelton said her father’s abuse of her mother was more emotional and mental than physical.

CRACKS BEGIN TO FORM Skelton said she felt suicidal for the first time at 14, after her father made her drop out of the church recital she had been practicing the violin for. He made her drop out on three separate occasions.

“I don’t know why my dad couldn’t just let me go,” she said. “I would attend all the rehearsals, and then at the last minute he would say I couldn’t go to the recital, and then I look like the asshole for dropping out. Nobody knew what was really happening in my house.”

Skelton called the Focus on the Family hotline, but they didn’t offer much help. She said she felt like she was always going to be alone and she was never going to be good enough for her parents to not punish her.

At 19, Skelton started college at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs. She wanted to major in English, but her father wanted her to become a dentist so she could run his practice with him. They got into an argument and after she threatened to leave, her father allowed her to pursue a major in English, although he still tried to convince her to become a dentist.

By 2011, Skelton started feeling like she wanted to leave again. At 22, she had never spent the night away from her parents.

“I spent a night away from home only four weeks before I moved out,” she said. “I was getting more and more unhappy, and my dad was cracking down on me again, trying to make me be a dentist.”

Skelton read the “Harry Potter” series for the first time and took a humanities class that discussed art, politics and war — different ideas she had never been allowed to explore before.

“My parents flipped,” she said. “They found that I was watching Harry Potter DVDs in the house. My sister turned me in, and then they raided my room and they took all the fantasy literature out of it because they decided I had a problem.

“They were talking about not letting me go back to school in the spring. That was the real breaking point. I started making a plan to leave. My dad made me cut all my hair off, because he said that women with longer hair get raped, because they can hold you down — he read some book. Then he enrolled us in Taekwondo — it was one of his weird anxiety things.”

Robertson said cracks in the UPC’s teachings started to show when she met people unlike herself, people who had different gender and sexual identities.

“I realized what the church has been telling me about other people was completely wrong,” she said. “I never would’ve called myself homophobic, I never saw myself as homophobic, but I was so deeply homophobic.

“The rhetoric of the church is about how anyone who differs from cis(gender), or straight, is an abomination to God, and the way I viewed God was that he created all of

the universe, all of nature, everything, he makes us perfect, and anything we do to change that is an abomination, which is a really hard mental hurdle to overcome.

“Even though I think I was an accepting friend, I would have never outwardly supported the LGBT community, because I was so scared of the backlash that I would receive in church if I ever came out with those kinds of ideas.”

Robertson said it was a Lamar study abroad trip to Brighton, England in 2019 that changed her life and the perception of the things she had been taught for the past decade.

“We went to the Brighton Museum and Art Gallery, and they had an exhibit called The Museum of Transology,” she said. “We just happened to be traveling with a trans guy at the time, and he and I just happened to go through this exhibit at the same time. I think it was destiny, because the combination of that exhibit with someone who was trans and them telling me their experiences absolutely changed my life.

“Up until that point, I had said horrifically homophobic things out loud that are so embarrassing like, ‘I think trans people are just confused. I think it must be part of a mental illness. If they received therapy they would come to their senses.’ Stuff like that actually came out of my mouth and I thought it was OK.

“It wasn’t until I started meeting people and learning about other people’s experiences that I thought, ‘No, they’re just people with a different life experience than me.’ I literally did not recognize them as the same kind of person as me until I had that experience in England. I’m so embarrassed of the ideas that I used to entertain.”

LEAVING

Robertson said she felt like she was living a double life at times. In 2018, she volunteered at the Jefferson County Democratic Party during the mid-term elections, but she didn’t tell anyone, only her mother, for fear of retribution.

“When I was deciding that I was going to leave the church and kind of working my way up to that, I thought to make things easier for myself and for my mom, because I didn't want her to worry about me, that I would just quietly move away and stop attending church and nobody would know,” she said. “I thought, when I visit home, I can just wear the skirt and put my hair in a bun and nobody will be the wiser.

“My friend referred to this as functionally closeted, which I think is a great term. I was all set to live a double life like that. I just kind of accepted that because I was so scared to come out as someone who didn't want to be involved in the church anymore.”

However, after going through some personal events, Robertson said she felt her life was out of control and she wanted to reclaim it.

“I called my mom and I told her I needed to talk to her about something important,” she said. “I went to her house and I just opened the conversation with, ‘I am deciding to not attend church anymore for these reasons, specifically — I want to support the LGBT community and I don't think I can do that and be apostolic.

“My mom cried and cried, which is the one thing I didn't want to see, of course. She was crying and said, ‘Does this mean that you're gay?’ At the time I said no, but now I feel that I don't know, because I never had the freedom to explore any of those ideas.

“But even if I'm not gay, I don't want to be a part of a system that actively hurts gay people. As I spent more time away from the church, I realized I actually escaped from a brainwashing cult. I believe my mom is still brainwashed, unfortunately. We don't have contact anymore because of different reasons, but I think that as long as she's married, and as long as she's attending the church, she'll never really know the extent

Claire Robertson speaking on her church’s platform in 2016.

that it hurt me.

“I'll never know who I could have been if I didn't have all those years trying to conform to this standard of UPC. I don't know what ideas I could have had because all of my ideas were selected for me.”

Robertson began giving away all of her church-related responsibilities as she prepared to leave the congregation, but she didn’t tell anyone why she was doing it.

“I know my mom started telling people, probably by saying, ‘Claire really needs prayer, she doesn't think she wants to be part of the church anymore, will you please try to say something to her?’” she said. “In the beginning (after she left), I got a couple of really nice text messages, a couple of really nice Facebook messages saying things like, ‘No matter what, we'll always love you, we're here for you, if you ever want to talk.’

“I remember, I got one message in particular that was like, ‘I don't understand, and I don't support why you’d leave, but we're always here for you,’ or something like that, which looking back is kind of condescending, but I think they were coming at it in the most genuine way that they could. I can't blame them because where they're coming from, they really believe that they have the secret to life, the secret to happiness and salvation. So, of course, when you believe that, and you see someone actively leave on purpose, it's kind of crazy and hard to understand.”

Skelton said she realized she needed to make a change when she started seeing a counselor.

“My parents got more and more concerned about me,” she said. “Even though most the time I was staying at school late to do calculus homework, my dad taped the number for campus police on the microwave and he would text me and call me all the time.”

Skelton’s parents also tracked her cell phone and knew when she moved from one building to another.

“So, I started making a plan to leave. I didn't know what to do yet, or where to go. Then my hand was forced because we went on a family vacation and my dad didn't let me have my laptop or cell phone. My parents had a plan to send me to Bob Jones Univer— Eleanor Skelton sity (a private evangelical school in South Carolina). I was three years into a degree program, I didn’t want to lose credits and I didn’t want to leave my friends.”

Skelton was ready to leave her family and her church when she found out her parents had withdrawn all of the money out of her savings account.

“Some of that was money I'd earned on campus, it wasn't all from them — they'd emptied out $10,000 out of my savings account,” she said. “I was like, ‘What do I do now?’ I talked to a bunch of friends, they're like, ‘Well, it can be hard, but you can do it.’

“I told my professors about it, and they were like, ‘This is really wrong.’ I told one of my English professors who told the other professors, so all the chemistry professors knew I was having a problem, all the English professors knew, so both my majors were like, ‘This is not happening to this child.’

“And they gave me money for the apartment deposit. I still didn’t have a car, but another friend on campus gave me a bike. And seven people in five cars, some of them even from my church, got together to help me move out.

“I had two meetings with the pastor, right before I moved out. In one of them he asked me what was going on? He asked, ‘Is there any sexual or physical abuse in your home that I don't know about?’ He did at least ask that. I said no, because I didn't know I was being physically abused.

“He told me that the Bible wants you to submit to your parents, and I’m an unmarried woman, and I’m supposed to submit to my dad until I have a husband. I gave in for a little bit, but I eventually told my parents I was going to leave.”

Skelton said her pastor walked out of his last conversation with her, telling her she was being deceived by Satan.

“I just sat in the sanctuary, and it still makes me cry to think about it, because I never had a pastor just, like, walk out on me like that,” she said. “I felt like I always tried to be the good kid and please the spiritual leader within reason.

Abuse — page 20