3 minute read

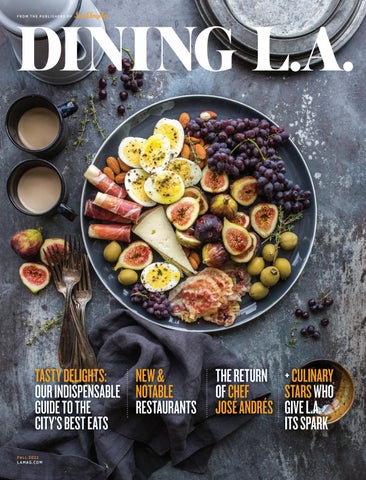

My Dinner with Andrés

AFTER TRADING IN HIS PAELLA PANS FOR BORSCHT BOWLS IN UKRAINE, CHEF JOS É ANDR É S IS OPENING THREE NEW RESTAURANTS IN DOWNTOWN’S CONRAD HOTEL BY JOEL STEIN

JOS É ANDR É S is finally, after all his world traveling, on vacation. He’s smoking a cigar in the Spanish beach town of Zahara de los Atunes, doing his version of relaxing, which, judging from the activity going on in the background of our Zoom call, involves about 7,000 friends. But in a few days, the 53-year-old restaurateur—whose bushy white beard makes him look like an Ernest Hemingway impersonator—will be slipping into one of his signature multipocketed fishing vests (phone, money, batteries, GPS system, cigars) and heading to Ukraine. Unless a natural disaster or another war or a plague of locusts strikes first, in which case, he’ll take his movable feast of a field kitchen there instead.

Andrés, though, has gone way beyond Hemingway’s famous volunteer mission as Red Cross ambulance driver during World War I. Through his World Central Kitchen, he’s providing emergency food assistance to the whole planet. Haiti, Puerto Rico, Beirut, Uganda, Nicaragua, cruise ships quarantined in port when COVID-19 first hit—if it showed up on a CNN ticker, chances are he went there. Using smartphone-era technology to summon local food trucks, restaurant workers, and volunteers, he’s built the Uber of food aid, delivering more than 70 million meals since 2010. Which explains why he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019, honored with a painting in the National Portrait Gallery, and recently had Ron Howard following him around for a documentary film called We Feed People (currently streaming on Disney+ and Hulu).

At the same time, the Spanish-born chef, who became an American citizen in 2013, is also expanding his empire of nearly three dozen restaurants. On the day we Zoomed in July, he was opening an outpost of his Eastern Mediterranean eatery, Zaytinya, in the new Ritz-Carlton in Manhattan. He’s also about to open a restaurant in the new hotel in the Old Post O ce building in Washington D.C., the former site of the Trump International Hotel, where,

ON THE ROAD in 2015, Andrés had originally planned to open a D.C. restaurant but pulled out when Trump started his anti-immigrant rants on the campaign trail.

Andrés takes a selfie with First Lady Jill Biden and Queen Letizia of Spain during a June visit to a refugee center in Pozuelo de Alarcón, Spain. Inset: Andrés’s new restaurant, Agua Viva, inside the Conrad Hotel.

More locally—in downtown Los Angeles—he’s opening three restaurants in the Conrad Hotel, part of the massive new Frank Gehry-designed complex on Grand Avenue across from Walt Disney Concert Hall. Two of them—San Laurel and Agua Viva—are already serving, and the most anticipated, Bazaar Meat, will be opening later this year. It’s the steakhouse version of Andrés’s West Hollywood spot, the beloved Bazaar, one of the few restaurants ever to earn four stars from the Los Angeles Times. The original Bazaar, in the SLS hotel on La Cienega Boulevard, was closed down during the pandemic in 2020, after the hotel was sold.

“I never left. I only took a little nap,” Andrés says of his two-year absence from the city.

He was eager not just to return to L.A., but also to get back to running all the food and beverage services in a hotel. “For me, hotels are very important. Because the hotel is the closest thing I have to feeding a small city. A hotel is an amazing ecosystem of multiple places where you have to take care of people,” he says. “The complexity of a hotel is my way of learning how to feed the world.”

I saw what he meant while I was sitting on the terrace of the tenth-floor Agua Viva, looking down on City Hall as the sun set, eating creamy crab croquettes and tender strip loin with chimichurri. It was undeniably good, but it wasn’t noticeably a José Andrés meal—no cotton-candy-covered foie gras or spherified olives that explode in your mouth or any of the other molecular-gastronomy delights that first made Andrés famous. Yet it was oddly perfect. The other diners—an attractive European couple to my left, a hipster Latin American group that came straight from the hotel pool— couldn’t have been better fed. It was as if Andrés was more concerned with giving people what they wanted than making them notice him.

“It’s not any di erent, putting a fancy place in a luxury hotel designed by Frank Gehry, than feeding Ukraine, where we opened kosher kitchens in Romania to feed the Jewish population,” says the man who, not long ago, repurposed his paella pans into bowls for borscht. “My dream,” he goes on, gesticulating so wildly that at one point he drops his phone, “is to feed a small town, maybe a city, maybe a country. I was always very interested in feeding the few, but I realized that that same intent could give me the power to feed the many.”