Planning for Beauty

Celebrating ten years of the Olympic Park

2022 Issue 2 landscapeinstitute.org

Briskeby DESIGN TANK FOTO EINAR ASLAKSEN Location The Plus Designer Andreas Engesvik Produced in Scandinavia vestre.com Lifetime anti-rust warranty 200 RAL colours

PUBLISHER

Darkhorse Design Ltd

T (0)20 7323 1931 darkhorsedesign.co.uk tim@darkhorsedesign.co.uk

EDITORIAL ADVISORY PANEL

Stella Bland, Head of Communications, LDA Design

Marc Tomes, Landscape Architect, Allen Scott Landscape Architecture

Peter Sheard CMLI, Landscape Architect

Jaideep Warya CMLI, Senior Landscape Architect, BBUK Studio Limited

Jo Watkins PPLI, Landscape Architect

Jenifer White CMLI, National Landscape Adviser, Historic England

LANDSCAPE INSTITUTE

Editor: Paul Lincoln paul.lincoln@landscapeinstitute.org

Copy Editors: Jill White and Evan White

President: Jane Findlay PLI

CEO: Sue Morgan

Landscapeinstitute.org

@talklandscape landscapeinstitute landscapeinstituteUK

Advertise in Landscape

Contact Saskia Little, Business Development Manager 0330 808 2230 Ext 030 saskia.little@landscapeinstitute.org

Planning to be beautiful

‘So often, the price of ongoing and expanding modernity is the destruction...... of everything most vital and beautiful in the modern world itself. Here in the Bronx, thanks to Robert Moses the modernity of the urban boulevard was being...... blown to pieces by the modernity of the Interstate Highway.’ 1

Print or online?

Landscape is printed on paper sourced from EMAS (Environmental Management and Audit Scheme) certified manufacturers to ensure responsible printing.

The views expressed in this journal are those of the contributors and advertisers and not necessarily those of the Landscape Institute, Darkhorse or the Editorial Advisory Panel. While every effort has been made to check the accuracy and validity of the information given in this publication, neither the Institute nor the Publisher accept any responsibility for the subsequent use of this information, for any errors or omissions that it may contain, or for any misunderstandings arising from it.

Landscape is the official journal of the Landscape Institute, ISSN: 1742–2914

© 2022 Landscape Institute. Landscape is published four times a year by Darkhorse Design.

The clash between two versions of the modern world expressed here by American philosopher Marshall Berman is also eloquently addressed by Sabina Mohideen in her review of Straight Line Crazy, David Hare’s new play looking at the ongoing conflict between New York Parks Supervisor Robert Moses and urban campaigner Jane Jacobs [p60]. This debate on when and what to build is also at the heart of the development of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, whose 10th anniversary we celebrate this year. Stella Bland recalls the “barrage of criticism ...unleashed against the folly and vandalism of ‘corporate development’” [p23]. And yet, the result, less than a generation later is a park that is both popular and beautiful.

As the government struggles to articulate its thinking on the future of planning for beauty, we publish a series of articles on refocusing on beauty in the planning system [p31]; creating a new generation of design codes [p34]; Natural England’s GI Design Guide [p39]; Design Review in Wales [p40]; and searching for beauty in Scotland’s National Planning Framework [p41]. In searching for beauty, it is perhaps best to look at

the way in which landscape design and planning can both describe and then facilitate the implementation of a vision for a greener, more sustainable future. This approach is well illustrated by two case studies presented at the Mitigating Climate Emergencies Conference [p6] and also by a series of articles on the history of the Olympic Park and its current approach to stewardship [p13].

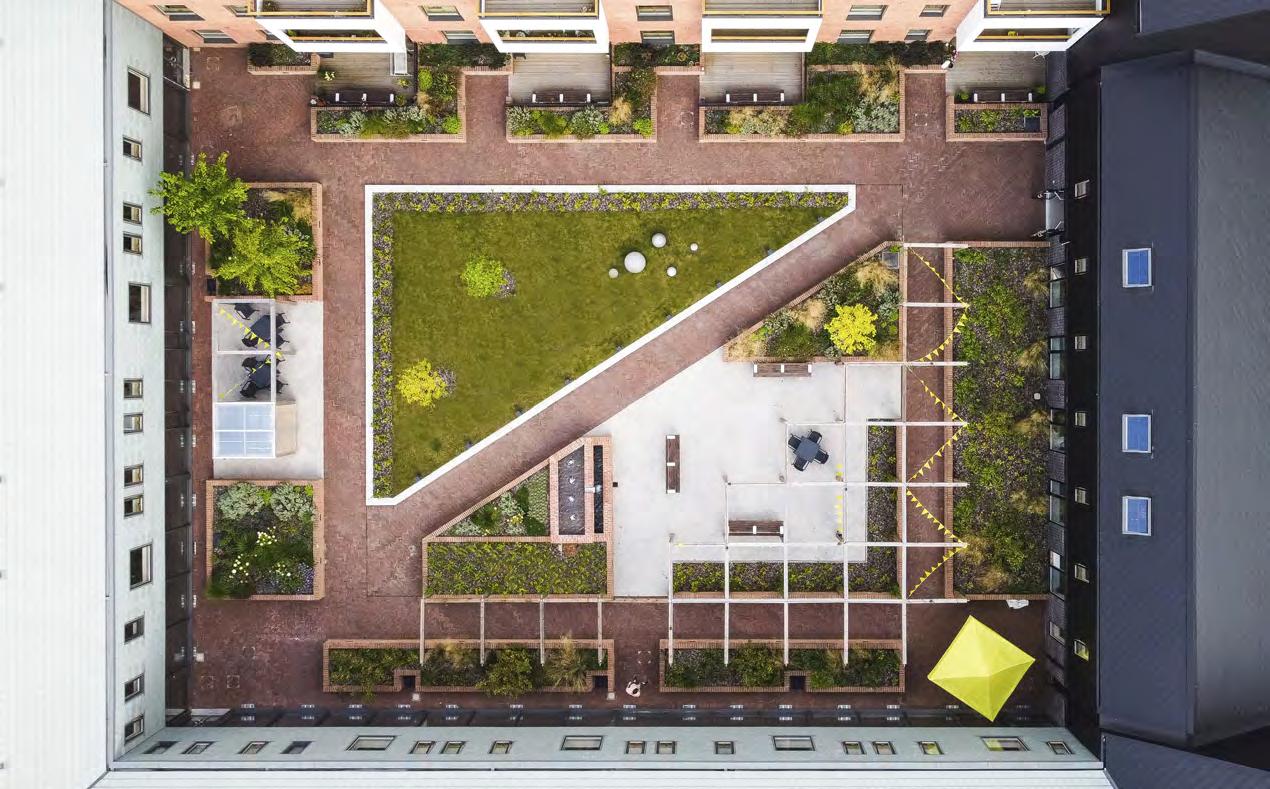

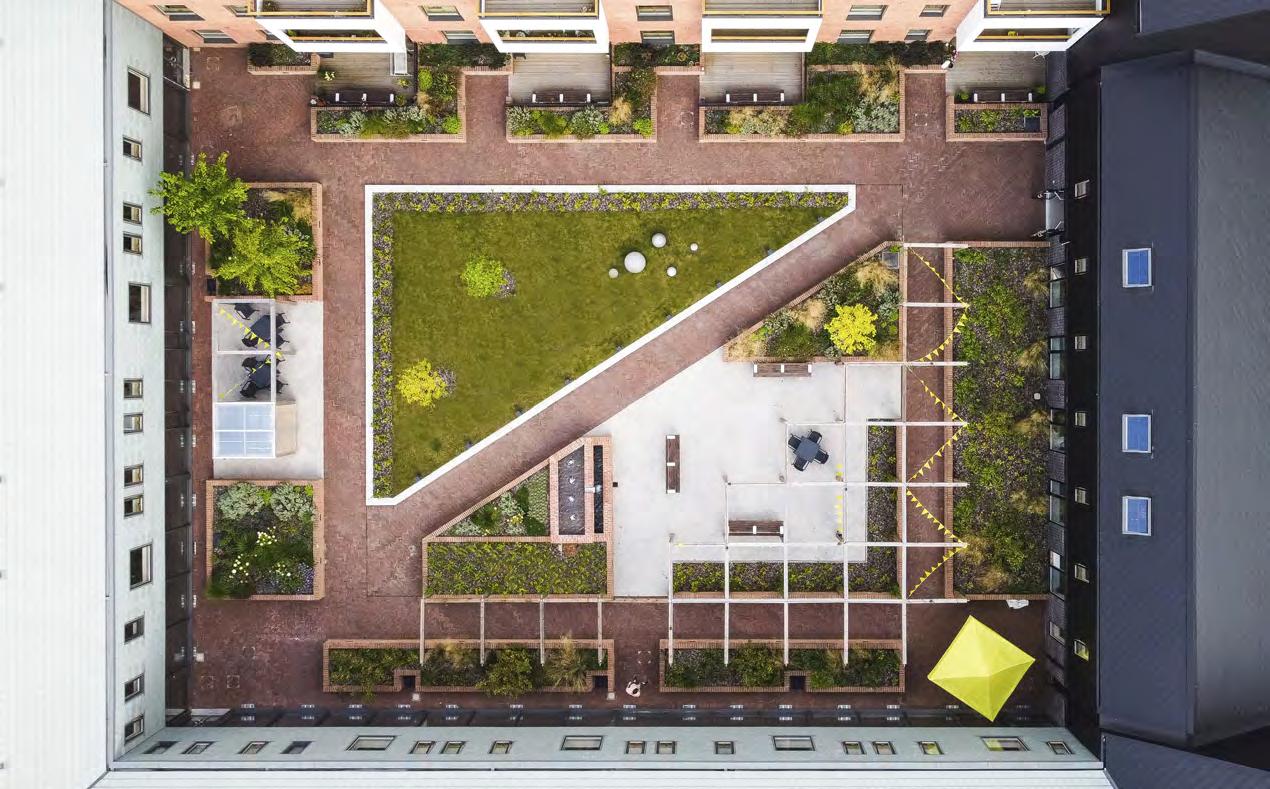

Beauty is much in evidence in a series of case studies: Exchange Square, Broadgate [p45], Alfred Place Gardens, Camden [p48] - both schemes moving the city decisively from grey to green. These are complemented by two schemes addressing the needs of older people which put landscape at the heart of successful development [p53].

Paul Lincoln Editor

1

WELCOME

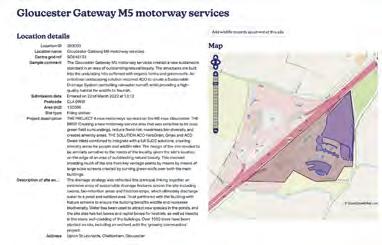

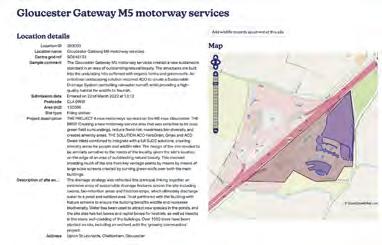

2022 Issue 2 landscapeinstitute.org Planning for Beauty Celebrating ten years of the Olympic Park View of the Olympic site in May 2022 Photographed by jasonhawkes.com

All

Melts

Air

of

Berman,

Landscape is available to members both online or in print. If you want to receive a print version, please register your interest online at: mylandscapeinstitute.org Make sure you also check that your mailing address is up to date. 3

That Is Solid

into

- the experience

modernity, Marshall

1982

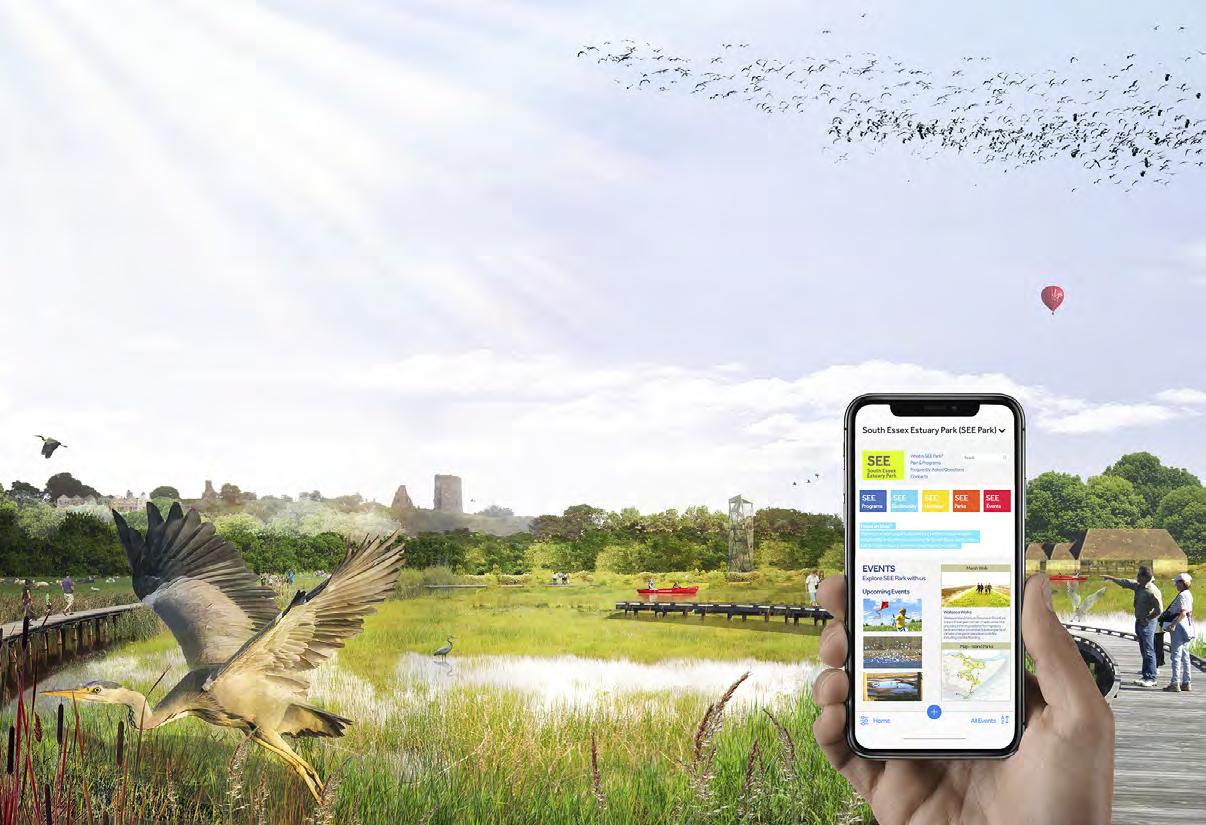

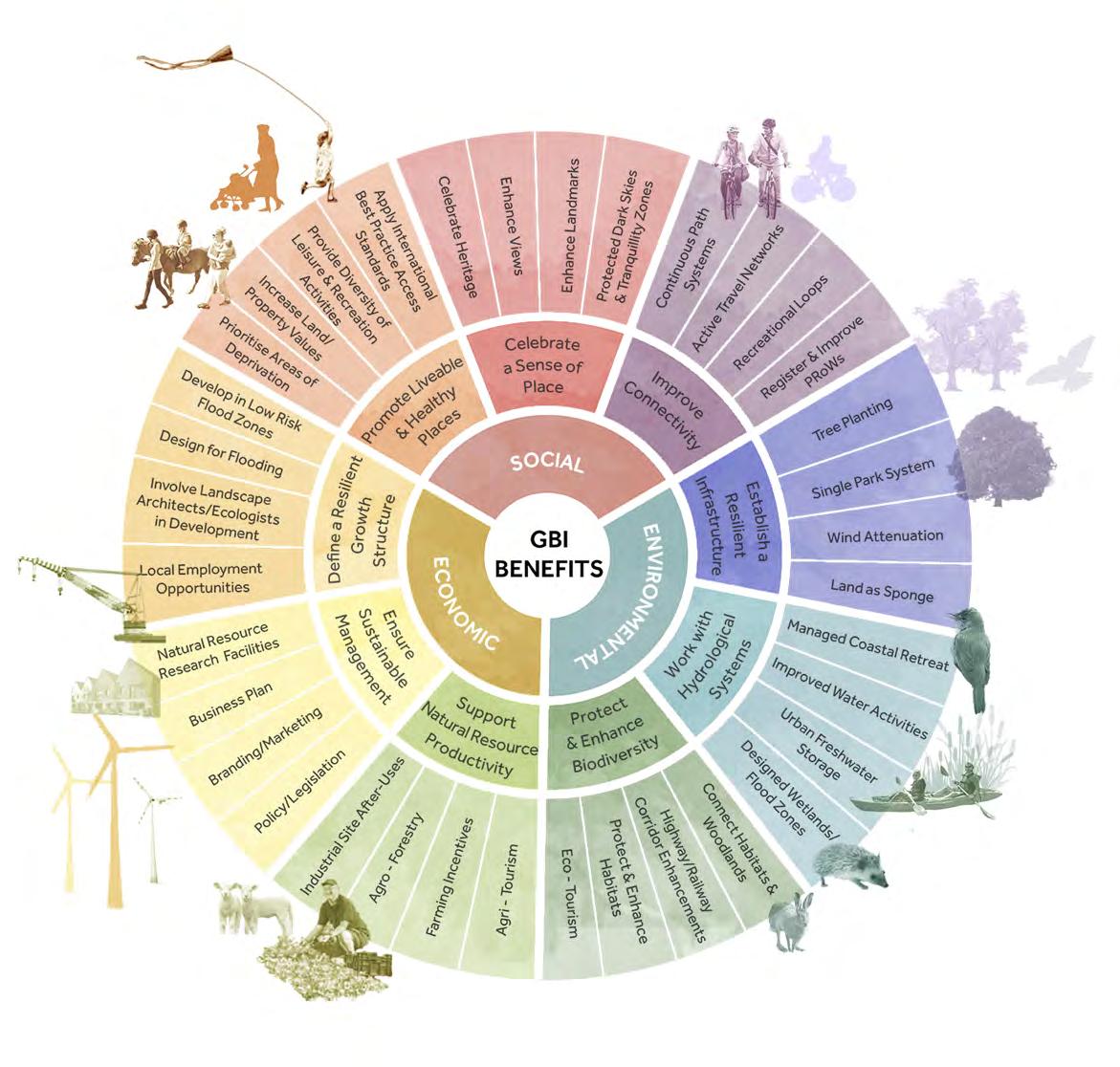

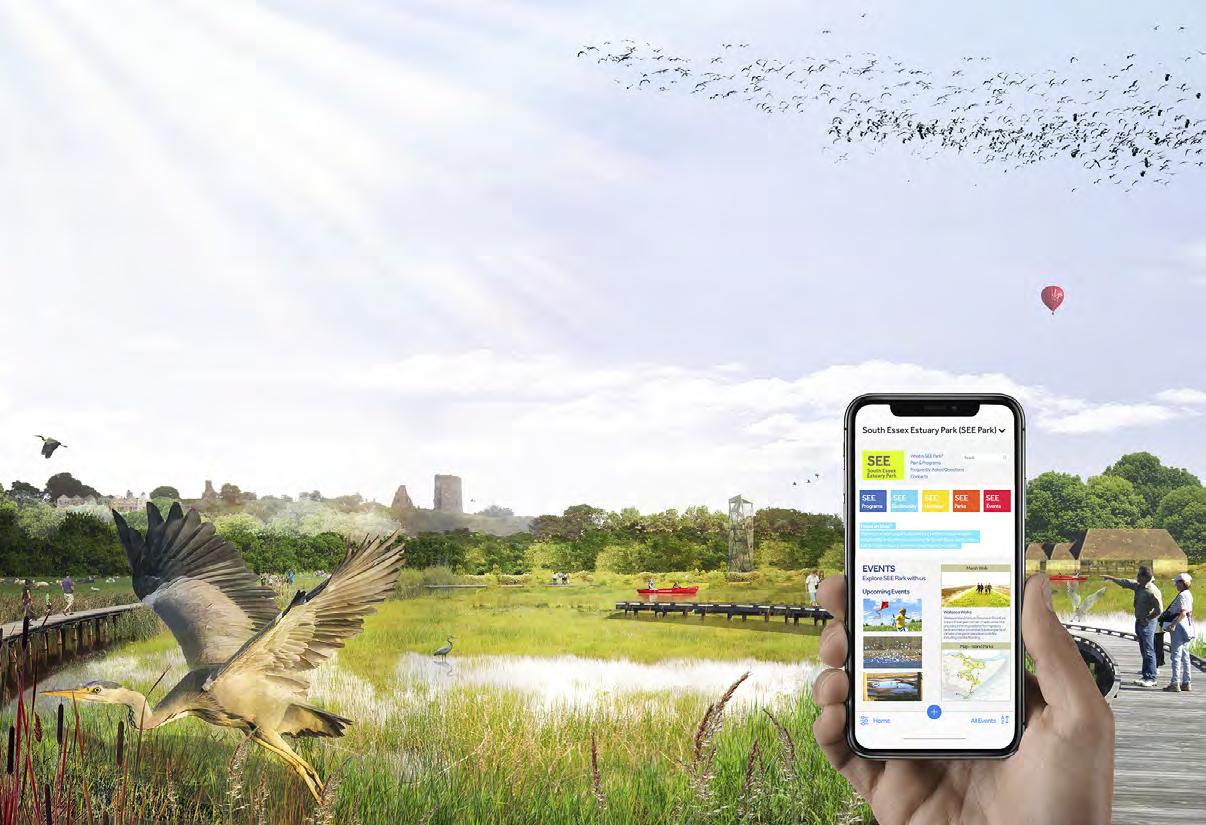

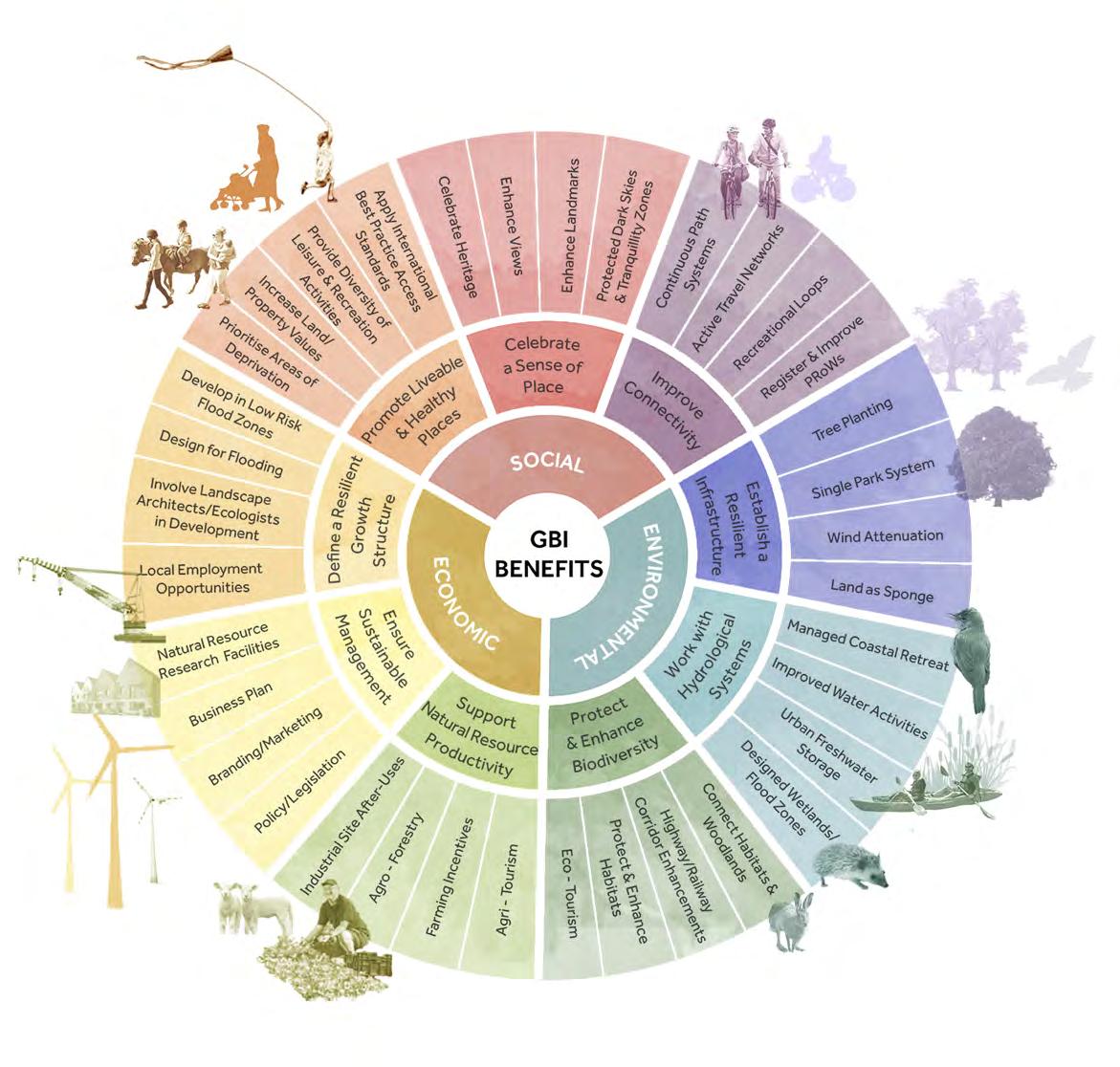

FEATURES Contents 4 BRIEFING: COP26 OLYMPIC PARK 10TH ANNIVERSARY Forest for Change at Somerset House Mitigating climate and biodiversity emergencies 6 Changing Spaces CPD Conference Reducing the impact of climate change in Gorton Park 10 Soaking up the pressure 7 Beauty and stewardship planning for the future of the Olympic Park 14 26 30 Reflecting on design and development of the Park Landscape Legacy Looking at a new generation of design codes Evaluating the impact of this report two years on Design review is at the heart of design quality in Wales Introducing Natural England’s new guide 34 40 38 The Leading Line Living with Beauty Design review Landscape is at the heart of this year’s London Festival of Architecture The Architecture of Landscape Green Infrastructure 17 Ten Years On

64 Graduation Ceremony 67 Cultivating Competence 69 CAMPUS: Learn from anywhere 60 53 58 Straight Line Crazy Landscape Design for Older People’s Homes Climate Emergency Revisiting the debate between Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses Responding to vulnerability in the design of landscape for older people Advice for practitioners CASE STUDIES FEATURES REVIEW RESEARCH CLIMATE EMERGENCY LI LIFE Award-winning landscape planning South Essex Green and Blue Infrastructure Study Lining up a new park above the tracks at Liverpool Street Station Scotland’s National Planning Framework 45 41 Exchange Square, Broadgate In Search of Beauty From grey to green as a highway becomes London’s newest park An update on the Government’s planning reforms 48 44 Alfred Place Gardens The Levelling-up Bill 50 5

Mitigating Climate and Biodiversity Emergencies –CPD conference

The LI’s most recent conference on climate emergency took place in March. The three-day online event is now available to download from LI Campus. https://campus.landscapeinstitute.org/

The conference looked at the ways in which the landscape profession is central to the fight against climate change and diminishing biodiversity. Speakers included [from left to right] Monika Nair, Atkins; Sue Morgan, Landscape Institute; Deborah Saunt, DSDHA Architects; Lord Deben, Chair of the Climate Change Committee; Mary Creagh, former Shadow Cabinet Member for the Environment; Lucy Marshall, landscape architect and Will Sandy, landscape architect. A number of speakers presented work that focused on communication of climate emergency messages. These included The Forest for Change, which took place at Somerset House and West Gorton Community Park in Manchester. These case studies are set out in the following pages.

BRIEFING: CLIMATE AND BIODIVERSITY EMERGENCY

6

Changing Spaces in Somerset House

The Forest for Change at the London Design Biennale challenged the dictum of the building’s architect that no tree should be planted in the courtyard, and in so doing, raised awareness of the United Nations Sustainable Goals.

Philip Jaffa

In June 2021, the Forest for Change adorned the courtyard of Somerset House, London, home to the London Design Biennale, the first major public event in this space following lockdown. Conceived by Es Devlin, I created a forest of

juvenile trees with a glade at its heart, where the public would happen upon an art installation celebrating the 17 Global Goals agreed at COP25 in Paris by the UN.

The creation of this event space was indeed a journey of the heart, whilst unexpectedly also an education into the effects of climate change on tree selection for our urban environments.

Global Goal 15 – Protecting all Life on Land, and as such, forests are vitally important for sustaining life on earth, and play a major role in the fight against climate change. This was our

starting point for the project, whilst agreeing that the forest’s purpose was to shroud the art piece by Es Devlin.

Having designed the 450-tree forest in terms of tree shape and form to achieve this, the challenge soon

BRIEFING: CLIMATE AND BIODIVERSITY EMERGENCY

1.

2.

1. View of the Forest for Change placed in the courtyard of Somerset House.

© Ed Reeve

2. The Mayor of London visits the scheme.

7

© Adam Lawrence

became which tree species to choose and to justify why, with the “why” fast becoming the pressing question of the day.

The initial temptation was to plant a native forest. A native tree is defined as a tree that colonised Britain some 10,000 years ago since the last Ice Age. However, increasing numbers of pests and diseases are attacking the UK’s trees, some with devastating consequences. Many of these problems have been imported, a consequence of the increasing use of European trees that tolerate our changing climate better than the natives. Current diseases within our native tree communities include Ash dieback (chalara), whilst our native oaks are declining at an unprecedented rate due to drought, flooding, pollution, pests, and diseases such as oak dieback and wilt. Horse chestnuts are under threat both from a bacterium (bleeding canker) and a leaf miner. The list goes on. Significantly, these trees are no longer readily available in our tree nurseries and hence were not available for our use.

Looking around London streets for inspiration, I discovered the incredible fact that there are more than 500 tree species on its streets today. When did this happen?

Speaking to David Johnson of Barcham Trees, I learnt that the major suppliers had been increasingly growing trees adapted to the changing climate of the urban environments for years – information we all know, but now put into context. Hence, trees that grow tight crowns and therefore do not restrict passing traffic or encourage root systems to spread which, as a result, thrive within restricted root zones, tolerate higher temperatures and stronger pollution levels, and have lower water demands.

The final piece to my jigsaw came during a conversation with Tony Kirkham MBE VHM, former head of the Arboretum, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, about his struggles with their trees because of the reality of climate change. He said: “The best way to ensure the long-term sustainability of our urban trees communities is to plant as wide a range of tree species as possible, because we don’t quite know what will happen.”

Given the circumstances, this

appeared to be the common-sense approach to the future of urban tree planting and my forest. Ultimately, the final selection for the Biennale was made up of 26 different species including several natives. The considered placement of each tree created differing sensory journeys to the art, while screening it, and, importantly, created a great-looking multi-height, form, and colour tone collective for the month of June.

Finally, the importance of the forest’s legacy was not lost. Following the Biennale, all trees were donated to the London Boroughs of Islington and Southwark, where they have been rehoused in numerous community schemes, schools, and streetscapes.

Philip Jaffa is the founding director of Scape Design with 30 years’ experience designing landscapes for the international tourism industry. Philip is passionate about the issues that motivate today’s ‘Conscious Traveller’ and as such pushes the debate around regenerative design, circular economies and how best to preserve the world’s most precious landscapes in relation to the future of travel.

BRIEFING: CLIMATE AND BIODIVERSITY EMERGENCY

3.

4.

3. View of the Forest at night.

© Project Everyone

4. Learning in the Forest.

8

© Project Earthshot

Glass, brass and a touch of class.

Barnsley, borne out of traditions of coal mining, glass making, brass bands and the surrounding beauty and inspiration of the Pennines, now has a first-class town centre and adjoining areas, including a new town square, incorporating retail, relaxation, and leisure facilities for all the community and beyond to enjoy.

Project: The Glass Works, Barnsley.

Client:

Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council.

Landscape Architects: IBI Group.

Contractor: Henry Boot Construction Ltd.

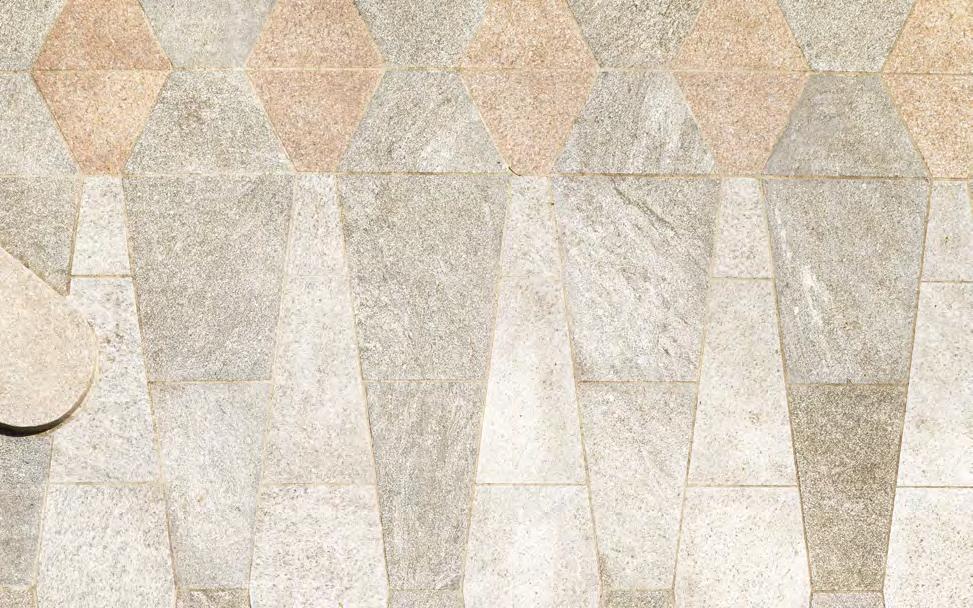

Materials Used:

Kobra Green and Yellow Rock granite paving: Kobra granite kerbs.

For further information on all our paving products please visit: www.hardscape.co.uk or telephone: 01204 565 500.

Soaking up the pressure

Jenny Ferguson

Manchester has a reputation for being one of the wettest cities in the UK. Climate change is exacerbating this by increasing the frequency of heavy rainfall events. Could a new park which uses a series of swales, rain gardens and bio-attenuation features to direct rainwater away from homes and prevent flooding be the answer?

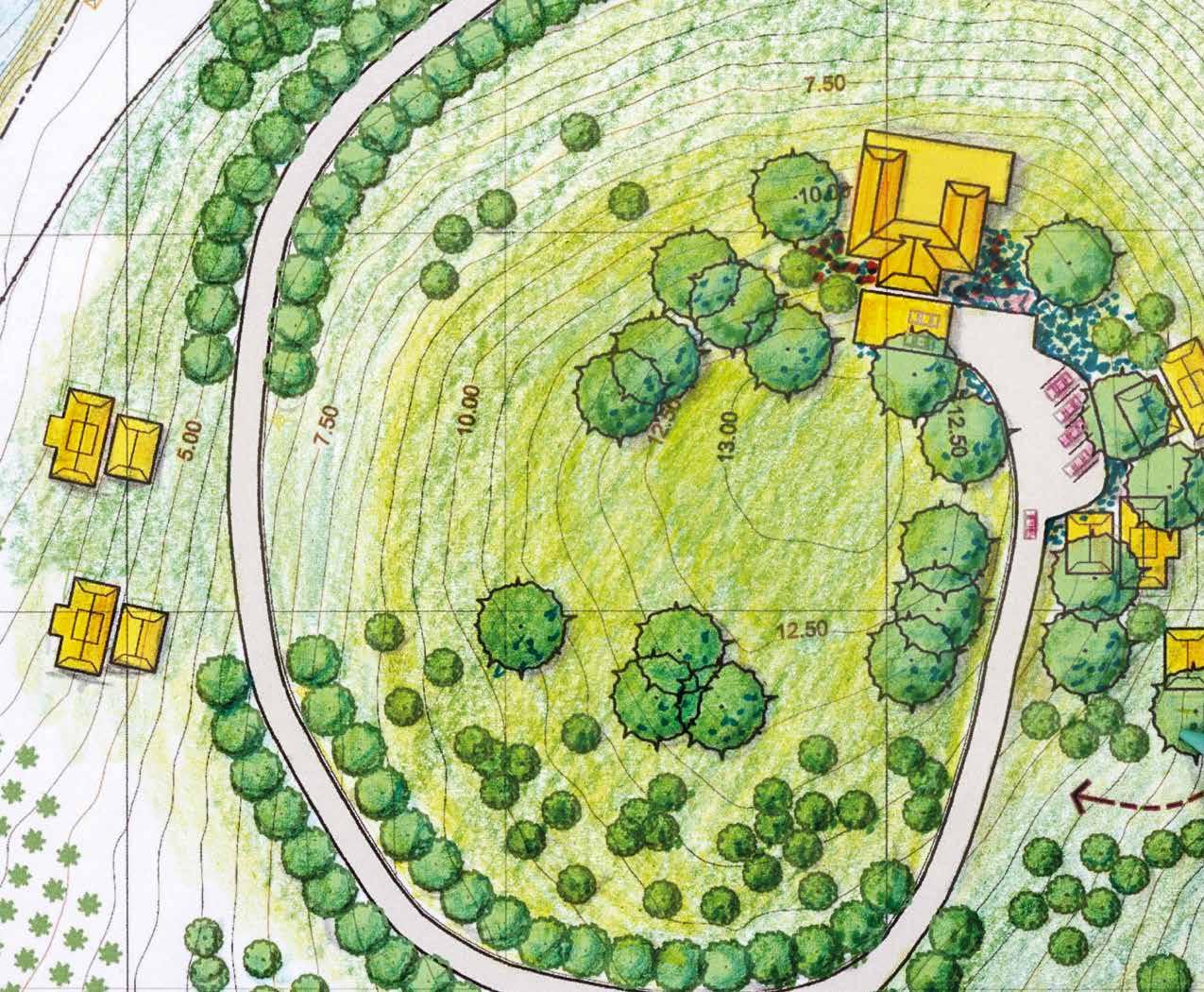

West Gorton Community Park is the final element in a £100m regeneration scheme of 500 new homes, community facilities and school improvements (the lovingly nicknamed ‘Sponge Park’ opened in summer 2020). It is the first UK demonstrator project for the “GrowGreen” initiative,

funded by the European Union’s 2020 Horizon programme. The project was a result of close collaboration with Manchester City Council, the housing and care provider Guinness Partnership Ltd and the University of Manchester, with the primary objective being to assess how nature-based solutions (NBS) could help combat the effects of climate change. The University of Manchester will monitor the design interventions over the next five years to ascertain how effectively the park can reduce flooding, improve health and wellbeing, and increase biodiversity. The data gathered will help inform the design of other green spaces, regeneration schemes and flood prone areas across the EU.

To reduce the capacity and flow rate of storm water from entering the active drainage system, BDP Landscape, together with Arup Civil Engineers, proposed to block up existing road gullies and divert the rainwater from surrounding road networks into the park, through

a series of sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) including bioswales, rain gardens, permeable paving, grass basins and pebble channels. A primary aspiration was to dovetail NBS and SuDS features into the overall park design, to add character

An inventive new park is helping to reduce the impacts of climate change, create nature and beauty and connect a Manchester community.

BRIEFING: CLIMATE AND BIODIVERSITY EMERGENCY

1. Bioswales creating informal play opportunities. © BDP

2. Bioswale timber stop dam to control flow of water. © BDP

1.

10

2.

© BDP

and richness to the landscape, and to encourage engagement with the natural environment.

Community engagement carried out jointly with Groundwork

Greater Manchester identified the neighbourhood’s aspirations for the park, including areas for families to come together, to play, exercise, grow food, and to host community events. Hands-on workshops and games helped raise awareness and educate people about the impact of climate change and how this would shape and influence the developing landscape designs, to create a future-proofed, climate adaptive and resilient park.

Pedestrian and cycle access was improved by linking each of the three park areas together, by redirecting traffic and through the incorporation of raised table crossings. Widened paths, improved sightlines and new solarpowered lighting increases safety at night, while seating added along routes provide areas for people to rest and enjoy the spaces. The park is split into three different character areas:

Woodland Play Space: Naturally tactile elements such as timber and rock are used in the playground, with objects placed to encourage physical movement and free play. A pebble rill captures water run-off and acts as a play feature for children to follow. Planting along this rocky creek captures and attenuates the water on its journey down to the ammonite shell, where you can listen to the sound of rainwater trickling into the chamber below. To the south, a sunny glade has been created by removing a dense cluster of existing trees, allowing light to penetrate down to the timber seating and ‘wild boar’ play features below.

The Meadow: In parallel with the primary pedestrian path, a sinuous trail with steppingstone logs and beams offers an alternative route and fitness trail for exploration. It meanders through the meadow and orchard picnic areas, with seating niches nestled into wildflower mounds using low timber sleeper retaining walls, and has steppingstones through the rain garden which lead to a storytelling space and living willow arch. Timber check dams across the swale slow

BRIEFING: CLIMATE AND BIODIVERSITY EMERGENCY

3. Raised vegetable planters for use by community.

4. Timber play structures and wildflower planting.

© BDP

5. Play area with cobbled drainage feature.

© BDP

5.

4.

11

3.

the flow of rainwater and encourages greater infiltration. Any remaining water reaches the raingarden and pontoon deck, where it is absorbed by moisture loving species including a feature multi-stemmed alder (Alnus) tree.

Community Garden: Open lawns, community growing areas and a south-facing Piazza enjoy full community use for events, sports and pop-up markets. Permeable paving filters rainwater through a series of formal channels which irrigates the new trees and plants and provides a rich, sensory environment for the community to enjoy. Long benches designed using stone filled gabion baskets provide habitat space for beneficial insects. Communal raised beds help create a sense of community spirit for residents who wish to grow their own food and provide easier access for disabled users and visitors. A timber pergola structure with an acrylic roof harvests rainwater into butts beneath, reducing the need for potable water irrigation.

A multilayered and artistic approach was taken to the planting and green infrastructure design, to enhance local biodiversity and amenity value. Over 60 new trees have been planted throughout the park to transform empty hard spaces into shady leafy green spaces, cooling the park in summer, providing habitat for birds, and improving the urban environment by filtering pollution and sequestering carbon. Over 180 linear metres of native beech hedge provide a soft boundary treatment which provides habitat and foraging opportunities for wildlife. Over 3,000m2 of wildflower swathes, bulbs and drought resistant planting provides rich nectar sources for pollinators.

A number of information signage boards have been placed around the park, designed to inform and educate people as to how the SuDS interventions and green infrastructure is designed into the fabric of the park design, as part of a conscious adaptation to climate change.

The community have taken pride – and ownership – of the new facility, which promotes social cohesion and wellbeing, together with the significant environmental benefits.

With increased awareness of sustainable issues and climate change directly impacting people’s lives, the design of community spaces and public realm is more important than ever. At West Gorton, the combination of natural solutions and intelligent drainage systems provide an innovative solution that supports the local community and solves many of the local council’s challenges. The result is a park that reduces flooding in one of the UK’s wettest cities, creates a net gain in biodiversity, but most importantly provides a lasting community space where residents can relax, feel safe and ultimately enjoy as a wonderful place where they can come together.

Jenny Ferguson is an Associate Landscape Architect, and chartered for over 14 years, Jenny has been responsible for the development and delivery of a number of notable projects, including the recently completed West Gorton Community Park. With a passion for contemporary ecological urban design, Jenny has a flair for creating dynamic environments, with an emphasis on enhancing people’s experience of landscape, whilst increasing ecological and environmental values.

BRIEFING: CLIMATE AND BIODIVERSITY EMERGENCY

6. Community Garden with water channels taking water to trees and planting beds. © BDP

7. Bespoke timber signage post. © BDP

8. Information sign boards. © BDP

6.

7.

12

8.

Celebrating ten years of the Olympic Park

This year marks the 10th anniversary of the Olympics in London 2012, and perhaps more significantly, the 10th anniversary of the creation of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park: by any measure, one of the most successful Olympic parks to be created in recent years, with a legacy for sport, community and landscape. Some of those involved ten years ago and many of those still involved in its design and management comment on this astonishing legacy.

1. View of the Olympic site in August 2010. © jasonhawkes.com

1. View of the Olympic site in August 2010. © jasonhawkes.com

FEATURE

1.

13

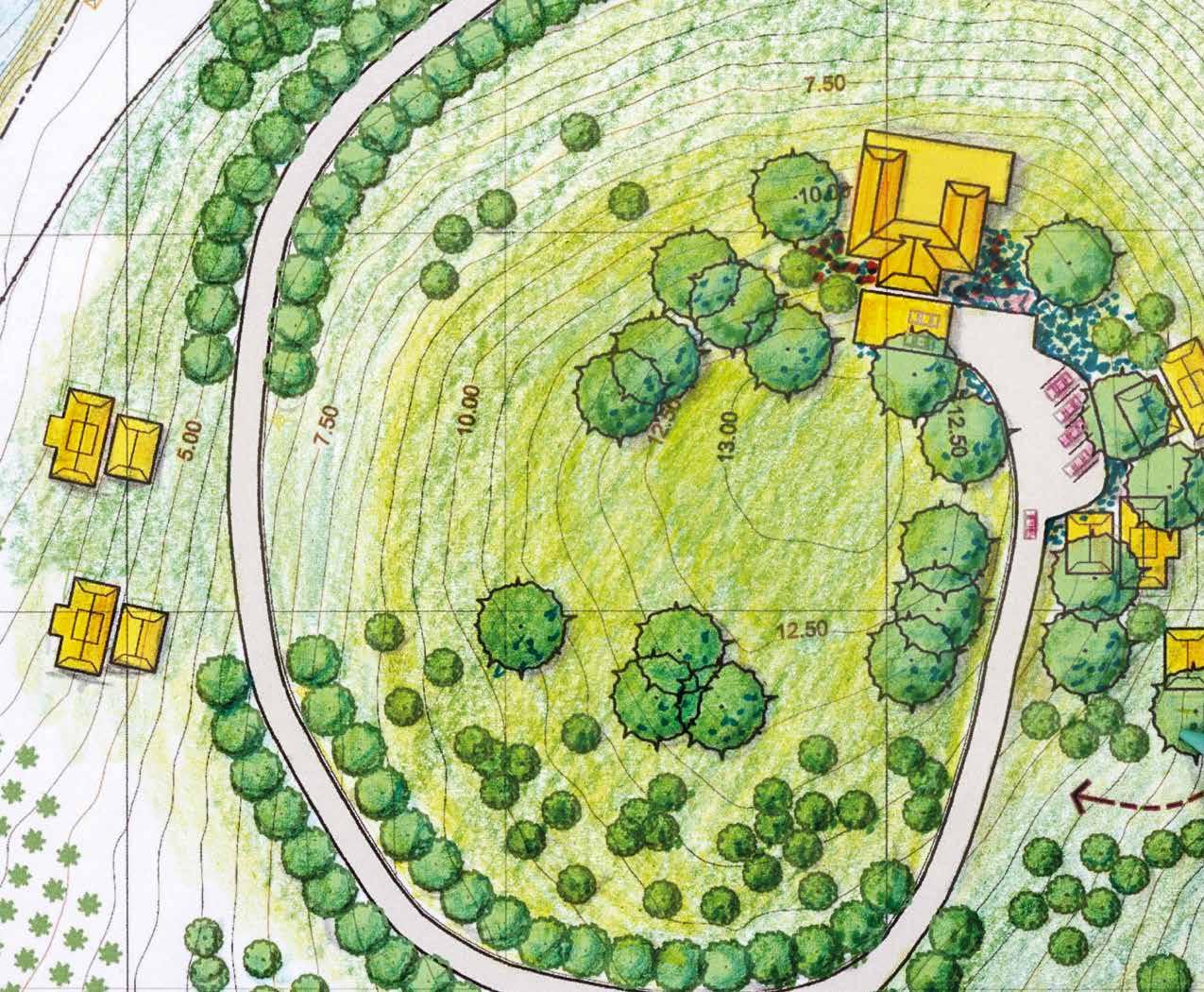

Landscape Legacy

Beauty and stewardship are at the heart of maintaining this legacy for future generations.

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park is celebrating a place which created something special in people’s minds and a designed London landscape that had not been seen since the creation of The Regent’s Park. It has been heralded1 as a successful Olympic Park with a legacy for sport, community, ecology and landscape – the continued development amplifying business innovation, education, art and culture.

With the Park at the heart of developing a ‘Great Estate’ in mind, it is a perfect time to reflect on beauty, as the government has placed beauty on the agenda within the context of planning legislation reform in England. The National Planning Policy Framework includes reference to beauty within the three intertwining sustainable development objectives –economic, social and environmental. The social objective ‘to support strong, vibrant and healthy communities… by fostering well-designed beautiful and safe places’ is encapsulated in the organisation, that manages and maintains the Park, the Legacy Corporation’s priority themes of promoting convergence, employment and community participation, championing equalities and inclusion,

and ensuring high quality design and ensuring environmental sustainability. With preparation to transition to a different organisation on the horizon, the Corporation is looking to embed these themes as part of the foundation of the stewardship of the estate.

There is no doubt that the original designers and landscape architect clients had a clear vision to create something beautiful that fulfilled a multitude of other functions. The directive to construct a place to host the ‘greatest show on earth’ which would be the greenest, most accessible and sustainable Games followed throughout the design and construction process.

What have we been left with as a legacy? There are two distinct areas of the Park that have clear identities. The

1 https://olympics.com/ ioc/news/london-2012a-legacy-that-keepsgiving https://matadornetwork. com/read/repurposedolympic-sites-stillworth-visiting-today/

FEATURE

1. Great British Garden Pond next to the London Stadium. © London Legacy Development Corporation

1.

14

Ruth Lin Wong Holmes

2. Gardens looking back to The Podium.

© Rahil Ahmad/LLDC – 2012

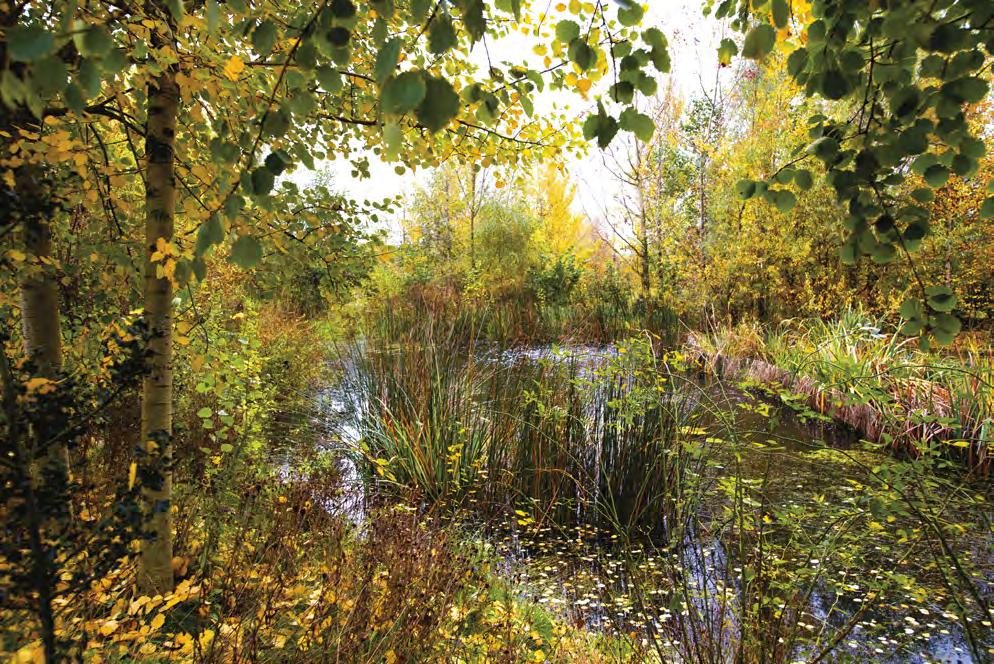

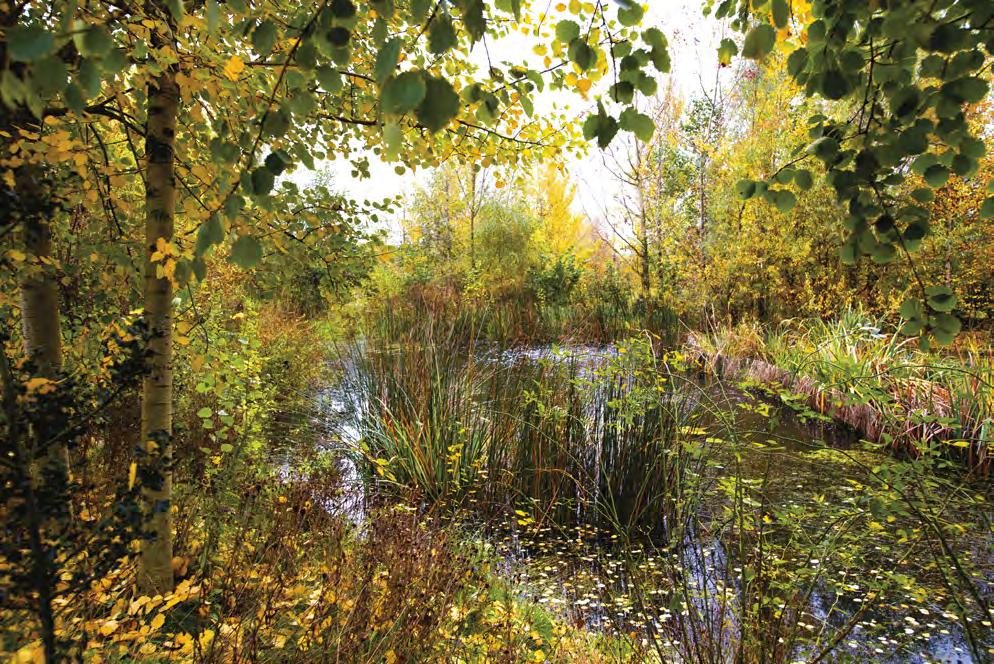

3. North Park view of wetlands along River Lea.

© In-Press/LLDC

A benefit of having such a young and developing landscape is that the first generation of designers are invited back annually to guide the current Park management staff.

2 Great Dixter Biodiversity

Audit Prepared by Andy Phillips for the Great Dixter Charitable Trust https:// www.greatdixter.co.uk/ great-dixter-biodiversityaudit

3 https://globalgrasshopper. com/destinations/uk/top20-of-the-most-beautifulparks-in-london/

4 Hoyle, Helen & Hitchmough, James & Jorgensen, Anna. (2017).

All about the ‘wow factor’?

The relationships between aesthetics, restorative effect and perceived biodiversity in designed urban planting. Landscape and Urban Planning. 164. 109-123. 10.1016/j. landurbplan.2017.03.011.

south of the Park is bold and bright, full of activity and horticultural delight with the planting designs of Piet Oudolf, Nigel Dunnett, James Hitchmough and Sarah Price. The water fountains, artwork and playful landscape are there to entertain, and it is often observed to be the most vibrant, attractive and diversely populated part of the Park. Confidence is drawn from Great Dixter’s research indicating their sophisticated horticulture delivers successfully for beauty and biodiversity2 . The north of the Park, by contrast, is a controlled and managed blend of contoured landscape, where habitat areas support a variety of wildlife, and where it is noted to be calmer and soothing with its green tones and integration of water and topography. Wide accessible paths cut through the sculpted landscape with the newer addition of the London Blossom Garden bringing interest and colour through flowering trees, surfacing detail and bespoke benches. A benefit of having such a young and developing landscape is that the first generation of designers are invited back annually to guide the current Park management staff. There is a fascinating exchange of views and learning at each meeting where a deep understanding of the planting design is explored and tested. Delicate light touch interventions each year are monitored, and largescale changes are planned to prolong the same horticultural interest as when the gardens were designed in 2012. Regular correspondence with the landscape architects who guided and designed elements of the Park is something which is unique and different about this site. Other significant parks require historical research and interpretation of a design intent, with the challenge of translating this into modern landscape management practices and contemporary use of the park. Promenading and perambulation to experience a ‘piece of the countryside’ in the city has been replaced with places to ‘do something’ where you feel safe and welcomed.

Developments around the Park have been rising out of the ground at a spectacular rate, with a variety

of architectural quality, massing and built form. The dominant emerging skyline has been enclosing the Park, forming a legible boundary. Sometimes the boundary is formed in a traditional way with park railing, road and residential building frontage. Other parts of the Park have a looser enclosure with transport infrastructure, cultural establishments and education buildings between the sporting venues of London Stadium and London Aquatics Centre. The pavilion buildings, like the Velodrome, sit within the landscape providing the termination of views, landmarks and large-scale wayfinding that makes the Park legible despite the complexity of levels, waterways, bridges and landform. The legacy venues form part of the set piece modern picturesque views, that

are accessible to everyone should they choose to visit – offering that Instamoment – on the looped paths that gently guide people around the Park. The beauty of the Park, and of many parks of a reasonable size or scale3 like other London parks such as Crystal Palace Park, Alexandra Park, Brockwell Park, Dulwich Park, Battersea Park and The Royal Parks, is that they have the capacity to have something to delight everyone. Research touches on the powerful attractive nature of planting and flowers for both people and wildlife4 But does everyone find the wilder aesthetic of the north of the Park beautiful? Not everyone will think so; for some it is a calm and magical place of great beauty, where spotting a kingfisher or observing the bumble

FEATURE

2.

3.

15

bee brings great joy – away from the intensity of the high street or office development. For others it is untidy, uncared for and does not feel safe 5 . There is concern that this wild, ecological definition of beauty is not inclusive, welcoming or inviting and the transition between the more rural environment that reaches out of London along the Lee Valley6 was not designed for the global majority. Therein lies one of the challenges of stewardship – providing equitable enjoyment of the Park.

Design is part of the equation, with the ongoing management and maintenance being another. Programming of spaces with invitation and welcome to ‘do something’ in the Park, along with the reinvention of spaces or insertion of new ideas or changes, can make the difference – but they have to be thoughtful and considered, ideally with an element of co-design with the communities who deserve to be better served. Landscapes are dynamic and continually change in response to the environment, climate, politics, funding, resources and the people who shape them. Those who have the power to influence and deliver change shifts and alters over time and the choices around what is beautiful, significant and valuable are moulded by influence and advocacy. The legacy we want to leave and be sustained sits within policy, guidance, corporate philosophy and people’s memories.

The quality of the design of significant parks and open spaces in London has left a special legacy that is being continued through skilled and careful management and maintenance, recorded in drawings, reports and management plans and the continuum of people handing on their knowledge over generations. The skill of

interpreting design intent and how that can be transformed and adapted for the shifting use of greenspace takes a collaborative approach, talented people and sufficient resources. Fast-forward another 10 years, and Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park will have changed significantly, with the greenspace nestling within the wider estate, with homes and offices overlooking the landscape. Hopefully that landscape will be a delightful place where everyone can find something they find beautiful and can enjoy. Future communities will be able to access the ecological, equitable and economically

important benefits of the Park, and that it will function in a sustainable, equitable and ecological way.

Ruth Lin Wong Holmes has 25 years’ experience as a Chartered Landscape Architect working for the public, private and voluntary sectors. Currently, she works at the London Legacy Development Corporation, responsible for Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park and developing neighbourhoods. She worked for The Royal Parks caring for historic parkland in London after working for a Groundwork Trust.

4. Wetlands along the River Lea. © In-Press/LLDC

5. Aerial view of North Park showing Lee Valley VeloPark, Lee Valley Hockey and Tennis Centre and part of Chobham Manor neighbourhood. © In-Press/LLDC

5 A case study exploring the role of cultural values in ethnic minority under-representation in UK parks – Snaith, B. (2015). The Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park: Whose Values, Whose Benefits?

6 Lee Valley Regional Park Framework https://www.enfield. gov.uk/__data/assets/ pdf_file/0012/5106/ cd-42-lvrpa-areaproposals-4-improvingenfield.pdf

https://library.olympics. com/Default/doc/ SYRACUSE/2287929/ over-125-years-ofolympic-venuespost-games-use-theolympic-studies-centre 95% of permanent venues still in use for London 2012.

FEATURE

4.

16

5.

2. Bridging the Gap schools programme. Designs for Greenway 2007.

Ten Years On

Ten years after the Olympic Games, a number of those involved in the design and development of the park look back on their engagement.

Young people were instrumental in highlighting gang-related territorial postcode issues that could plague the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park [QEOP], prompting the new E20 postcode.

Nick Edwards Architecture Crew, Youth Architecture Forum

My involvement in democratising the landscape of the Lower Lea Valley started in the halcyon New Labour days of the early noughties, with its ‘Sustainable Communities’ agenda. I was in the right place at the right time, living in LB Newham and working on estate renewal as part of a New Deal for Communities programme.

In 2003

I co-founded Fundamental

Architectural Inclusion, a CABE-funded Architecture Centre with the aim of building long term relationships with people to help them genuinely take part in the process of change in their neighbourhoods. Against the massive backdrop of the Stratford Metropolitan Plan, our pilot project tested the appetite of young people to be involved. Our approach was creative, utilising film and other multidisciplinary techniques, which led to the birth of the self-styled Architecture Crew, Britain’s first Youth Architecture Forum.

In the same time frame, London was bidding to host the 2012 Games, which created a great energy and focus for the Crew. They carried out

peer research to gauge the effect of hosting the Commonwealth Games on young people and East Manchester’s regeneration and even presented their own designs for the Aquatics Centre, following the same design brief as the architecture competition to the 2012 Bid team.

FEATURE

1. Park Life Legacy Youth Panel Event 2011. © Fundamental & Olympic Park Legacy Company.

©

Fundamental

1.

17

2.

London winning the Bid in 2005, and the subsequent legacy imperative offered a fantastic opportunity to roll the Crew model out across the host Boroughs through the creation of the Legacy Youth Panel [LYP]. We facilitated monthly meetings with young people, EDAW and the masterplan team, where the Panel critiqued the masterplans as they emerged, culminating in a Manifesto, and making an official response to the Legacy Masterplan Framework. We also worked in primary and secondary schools across the host Boroughs, feeding ideas for the park directly into the masterplan team.

Young people were instrumental in highlighting gang-related territorial postcode issues that could plague the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park [QEOP], prompting the new E20 postcode. They also sat on the judging panels for international architecture competitions, resulting in Erect architectures’ Timber Lodge and Tumbling Bay playground in North Park and James Corner Fields Operation’s South Park Plaza. My own involvement culminated with LYP members regularly sitting on the Quality Review Panel and the creation of a Youth Board for LLDC in 2014.

I was privileged to have witnessed first-hand the transformation of this corner of east London from neglected fly-tipped brownfield land to undulating wildflower meadows, wetlands and reed beds along the former tidal, canalised river Lea. I now work as an architectural tour guide and have proudly shown hundreds of people from all around the world the QEOP, telling the story of the pivotal role young people played in shaping it. In the early noughties, young people were lucky if they got to ‘choose the colour of the swings’. It took a lot of hard work and lobbying to get to a point where they are now more likely to be involved in the redesign of their neighbourhoods.

Nick Edwards is an architectural educator and Tour Guide; he co-founded Architecture Centre Fundamental Architectural Inclusion 2003–14 LB Newham.

3. Architecture Crew recruitment flyer 2007.

© Fundamental. Design: Alphabetical Order.

4. Legacy Youth Panel Manifesto 2009.

© Fundamental & London Legacy Development Corporation. Design: Alphabetical Order.

5. Legacy Masterplanning Framework consultation at EDAW 2008.

© Fundamental & London Legacy Development Corporation

6. Legacy Schools Programme planning game for Legacy Masterplan Framework consultation 2009.

© Fundamental & London Legacy Development Corporation

FEATURE

5.

6.

3.

18

4.

The park became the star for those visiting the Games and demonstrated to a global audience the power of great landscape architecture.

Phil Askew

The ‘expert client’

In 2009, I was privileged to be asked by John Hopkins to ‘help out’ on the client team for the delivery of the 2012 Olympic Park – an experience that for me has been transformative. When John described the brief, I got it – the opportunity for landscape architecture to reflect a bold new approach and respond to the real challenges of climate change and city living.

In the three breakneck years that followed, I had the opportunity to work with some amazing people and learn daily from an extraordinary team of project managers, designers, and experts. It enabled my transformation from a designer to a client, and in doing so, I realised that an expert client enables the creation of a good brief and a design team to work effectively and collaboratively. Sadly, John passed away before the completion of the park for the Olympics, but I was hugely inspired by his passion and commitment and today I often ask myself – what would John have thought?

Ralf Voss The Athletes’ Village

When we received the call to come to London, we were open for everything but certainly not sure what we were getting into. The projects we had done previously in England, like the landscape design for Tate Modern or the Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance, were more compact and clearly structured compared to the Athletes’ Village. The situation on site, with its vast soil remediation process, stripped of almost all natural and cultural context and a draft masterplan that did not have political backing, did not bode well for a Swiss landscape team.

Landscape architecture was key to establishing this new part of London as an urban quarter and not a residential estate.

The landscape vision for theOlympic Park was a bold one which set out to challenge thinking and show how relevant green infrastructure is in the face of a changing climate. Every part of the completed landscape was carefully considered and had a purpose and integrity. The process of ensuring all the components, soils, plants, drainage, lighting, irrigation, management, and buildability worked together required huge effort and collaboration. For me, it demonstrated that we have worldleading expertise and skills to design and deliver landscape architecture at scale and, in doing so, change perceptions and design approaches. The park became the star for those visiting the Games and demonstrated to a global audience the power of great landscape architecture.

Dr Phil Askew is Director of Landscape & Placemaking at Peabody. He is leading on Thamesmead, London’s New Town and one of London’s largest regeneration and development projects.

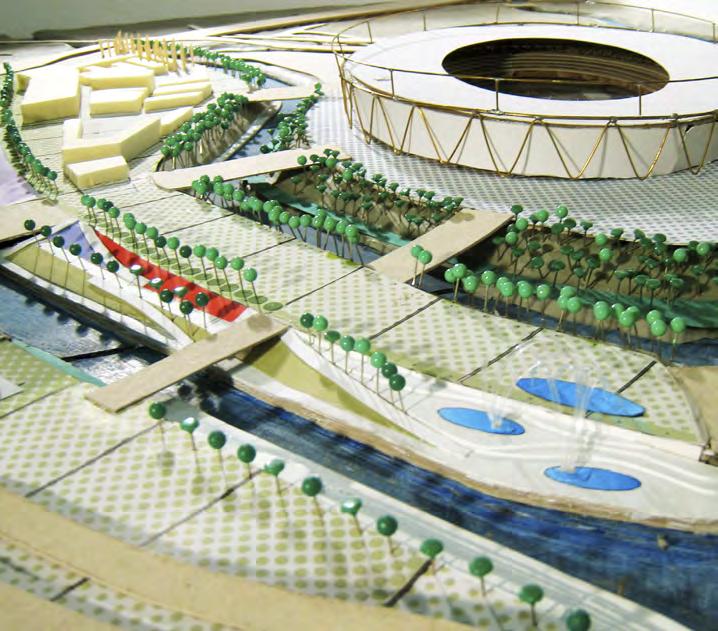

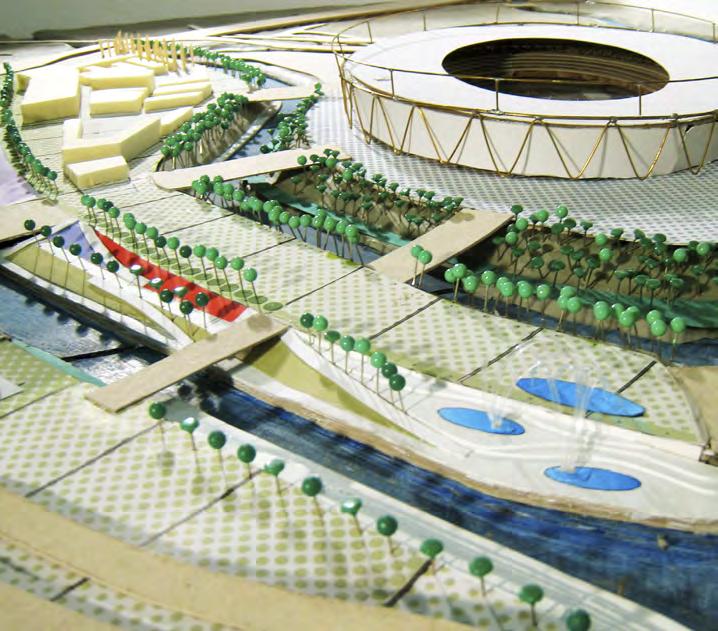

With a little help from our friends, we quickly established a first London base in Borough Market and filled the space with a large-scale work model to fast track the design and the coordination process with clients, developers and the master planning team, as well as with a series of different architects and planners. VOGT had used a design process

based on analogue model work successfully before, but this time the method was applied to a whole urban quarter and its variety of open spaces. It also showed its merits as a tool for communication within our office and with the large and always changing design teams of architects, with client representatives and authorities alike. Scale and model changed over months and years, but the landscape story remained. The landscape architecture was key to establishing this new part of London as an urban quarter and not a residential estate. The new landscape brought back elements and reminders of the former natural, infrastructural, and cultural context of the Lea valley. It pushed the questions of sustainability, urban nature and rainwater management in dense urban quarters further and made a clear statement of how the legacy of large scale events can be achieved for the London games and for other events to come.

Ralf G. Voss, landscape architect at VOGT Zurich, trained in Hanover and Edinburgh, was VOGT’s project director for the East Village Landscape.

FEATURE

7. Model for the Athletes’ Village. © Vogt

19

7.

Peter Neal Starting with the park

I was seconded part-time to support the planning and design of the Olympic Park a year after London won the bid to host the Games. Working for both the Olympic Delivery Authority and CABE Space created great synergy, giving us the chance to put CABE’s growing body of research and guidance directly into practice. Here was a unique opportunity to collectively create and test a truly contemporary model for twentyfirst Century urban parks in London and demonstrate how to start with the park at a significant scale.

The project respected but did not replicate London’s great pedigree of public parks. It has transformed a neglected and polluted stretch of east London, providing a green heart and ecological infrastructure for the increasingly dense and high-rise communities of Stratford. Central to its success was designing the sequential process of change rather than adopting a fixed approach to master planning; embracing the Games in 2012 whilst preparing in parallel for the subsequent transformation and long-term legacy. For me, the particular beauty of the park is not static but dynamic, expressed through this living and working landscape – the changing of the seasons, the song of reed warblers, raucous picnics and the hubbub of children playing at Tumbling Bay.

The stature of the project brought together the very best of the landscape professions who somehow were not scared off by the intimidating and punishing programme – brief-writers, ecologists, engineers, planners, politicians, project managers, quantity surveyors, designers, horticulturalists, soil specialists, nurseries, contractors and landscape managers. Individually and collectively, they all made the park what it is today, and most but not all are named and featured in the book John Hopkins and I wrote about the project. But especially, the park represents a

remarkable professional legacy and testament to John’s vision, tenacity and wit for the urban landscape.

Simon Green A true piece of green infrastructure

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park continues to develop as a positive legacy of the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. As part of the team working with the lead designers (LDA and Hargreaves), Arup developed the detailed design and specifications and led and coordinated the public realm and landscape design team for the South Park, through the planning, construction, tender and implementation process. This was my first experience of a truly landscape-led and systems approach to solving complex and technical challenges and master planning part of a city.

Sustainability and multifunctionality, as well as beauty, were at the core of the landscape proposals and at all levels of thinking, from the installation of a soil-washing plant to clean 30,000

tonnes of site material for reuse in the works (ensuring a cut and fill balance for the project and the reclamation and cleaning of 8.5km of riverside to transform the waterways throughout the park), down to the detailed specification of non-PVC pipes for surface water drainage to reduce the use of plastics and cut embodied CO2, and the use of concrete mixes with the highest possible recycled material content.

A true piece of green infrastructure, QEOP has enabled the regeneration of this part of East London, and demonstrates the power of landscape to generate value across the spectrum – getting the landscape or GI in first as catalyst for development whilst addressing climate change, biodiversity resilience and adaptability. The involvement of multiple stakeholders and public private partnerships as well as the local community both at Games time and in Legacy mode has ensured the success of the park, with rigorous management and maintenance considered from the outset.

This landscape-led multidisciplinary team approach must be seen as the norm rather than the exception in city design and regeneration.

FEATURE

Peter Neal is a landscape architect and environmental planner and a fellow of the Landscape Institute.

Simon Green is a landscape architect and master planner at Arup. He is a visiting tutor for landscape design and urbanism at Kingston University and a panel member on the High Street Task Force.

8. Park during the Games. © Peter Neal

20

8.

As landscape architects, we were at the interface of the competing demands of every interested party.

Andrew Harland Living the park

“Where has the park gone?” This was the first question I asked when LDA Design took on the landscape masterplanning of the Olympic Park in 2008. Civil engineering infrastructure had come to dominate the park and fragment the site. It was essential that landscape architects took charge, to secure a decisive response at a scale to match the infrastructure and the games buildings. We identified the site’s real asset, the River Lea, sluggish and polluted and sunk deep in a channel. The steep banks were pulled back to create the park and to give the river a heroic presence.

I think it was a defining moment for the profession when LDA Design took on leadership of the largest and most complex landscape project that has been delivered in the UK, with a team of 20. There was a lot of scepticism at the outset among the other project teams because we were “only” landscape architects, about to disrupt the progress of the engineering and construction. Over time, we changed perceptions – through persuasion,

tenacity, and by delivering. During that three-year design phase, we lived the park. I had never experienced such intensity before. Every move was made in the glare of intense national scrutiny and governed by sheafs of protocols. As landscape architects, we were at the interface of the competing demands of every interested party: the venues and the infrastructure teams, the ODA departments, and statutory stakeholders. Our co-consultants proved to be fantastic collaborators, but we all had to raise our game to a whole new level. It was fun, bonding, and massively rewarding.

LDA Design has since worked on a dozen Legacy projects and my close bond with QEOP is constantly reinforced, from the University College London East [UCLE] campus masterplan and East Bank to a landscape protection study and being on review panels. The power of QEOP lies in its social purpose and the sloping lawns of the River Lea throng with local families every weekend. Now my daughter has even chosen to make her home in Hackney Wick, two minutes from the park.

Andrew Harland is a director at LDA Design and jointly led LDA Design’s work on the Park.

Neil Mattinson A purposeful park

The legacy of London 2012 is the strongest ever delivered by an Olympic Games, anywhere. There are no decaying white elephant venues here, but a Park that welcomes young mothers and the newly retired equally. This is a purposeful landscape, a driver of social and economic change, providing doorstep nature for once neglected areas and catalysing a rebalancing of London – a pull east that continues ten years on.

The creation of the Park was ambitious in myriad ways. It was the first time that new wildflower planting been delivered on such a scale in the UK. Many of the site’s ecological targets have been realised: otters have been sighted; kingfishers are flourishing. This on a site so badly contaminated, it had to be completely stripped and rethought as a riverine park.

For me, the Park has a boldness that you rarely see. That’s its secret. Landscape at this scale – any scale, really – is likely to miss its mark if it is not truly ambitious. You must be confident enough to identify the power

FEATURE

9. The paving pattern design being tested in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern. © LDA Design

21

9.

in the landscape. It will provide the single, strong, simple idea that will lead everything else – here, it was the River Lea. From there you can build in the new views and make sure it becomes both part of the everyday and is also loved for being special.

The Park was a commission like no other with the ultimate, non-negotiable deadline and the world watching and waiting. A large team of specialists working at breakneck speed and an expert ‘hands on’ client combined to make it the most demanding and most rewarding project of my career, an experience which will stay with me forever.

I believe it moved things on, pioneering new standards in ecology, adaptability, and sustainability, and ensuring landscape architecture was seen as key to unlocking potential. I still get asked to showcase the Park to new clients, and they get it straight away because its power is plain to see.

Ben Walker Creating a proper park

My first day in my first job in 2007 was working on what is now Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. How lucky was that? The standout landscape of a generation. It was ‘in at the deep-end’ stuff, but what a wild swim.

The park has been a constant throughout my career. I’m now helping to develop new landscape thinking to transform Carpenter’s Estate, which borders QEOP, working with teenagers and finding out what home, shared spaces and the park means to them.

I learnt so much on this project, and every time I head back, I see the value of the decisions we made over ten years ago. For example, the initial plans for the Olympic Park had overlarge concourses, which we pushed back on to ensure that we could create a generous, enduring green space –a proper park! – whilst making sure it was safe and comfortable for large

numbers of people. I’ve taken this learning with me onto other projects such as Battersea Power Station, another at-scale, decade-long LDA Design project where we are creating fabulous new public realm for a formerly cut-off industrial site.

Leading the complex design process for the park positioned landscape architects front and centre. It also put reuse of materials and carbon sequestration at the heart of the design, setting ambitious targets for biodiversity gain that are only now making their way into design standards. Landscape-led design has gained traction because it results in the most remarkable places, and the creation of the park is pivotal to this shift.

Every year, I host a walk around Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park for landscape architecture undergraduates from my alma mater, the University of Edinburgh. Sharing a fraction of what I’ve learnt with students about to embark on their professional lives is a highlight. I can’t help but feel proud, and I can’t help but wonder what they will look back on with a similar sense of pride 10-15 years from now.

Benjamin Walker is a director at LDA Design and London studio lead. Current projects include Carpenter’s Estate and Battersea Power Station.

Neil Mattinson is a director at LDA Design and jointly led LDA Design’s work on the Park.

FEATURE

10.

11.

10. Landscape masterplanning for the Park aimed to secure a decisive response at a scale to match the infrastructure and the games buildings.

© LDA Design

22

11. Model of South Park. © LDA Design

Stella Bland Vandals or Visionaries?

Our perceptions of place and landscape change with time. Before 2012, a barrage of criticism was unleashed against the folly and vandalism of ‘corporate redevelopment’ of the derelict site in east London for the Olympic Park. Suspicion of change was partnered with nostalgia. But did the critics have a point?

Rob Aspland Working with clay

I’d worked on some complex and challenging projects before the Olympic Park, but this commission was at another level. I remember how tricky the first few months of the project were, because our first contribution to the park design was to challenge assumptions that had long been held about the size of concourse needed and the retention of a stream channel in the north of the park.

We knew that having less concourse (which would only get removed post-Games) and diverting the channel would allow us to create way more park both for the Games and the Legacy modes, and also make more of the river. In hindsight that may sound obvious, but we were working in the context of an early works contract that was already seeing earth moved and bridge abutments built. We had to make the argument with exceptional technical rigour and conviction, working collaboratively with

crowd movement specialists, river and drainage engineers, ecologists, structural engineers and cost consultants to get what we knew to be the best result for the park.

We won those early arguments and developed a design that set new standards in inclusion, habitat creation, and water and waste management. We brought the same technical rigour to dealing with countless technical challenges along the way. Seemingly in stark contrast though, we developed that design of the park using a large-scale working physical model constructed from clay. This malleable, tactile material allowed us to express a playful and sculptural topography that framed views and shaped habitats. What struck me at the time, and which has stayed with me since, was how precision and rigour was the enabler to the sort of creative freedom exemplified by our work with the clay, not the antithesis of it.

Rob Aspland is a director at LDA Design. He is working to transform Westfield Avenue and movement around London’s South Bank.

Distrust of grands projets lies deep in the British psyche. Hackney author Ian Sinclair spearheaded the campaign against developing the site with his Ghost Milk, a scorching diatribe on “the long march towards a theme park without a theme”. Protesters believed the whole meaning of the site lay in its past, its post-industrial ruins, so any new place was bound to have no meaning. Sinclair wrote about “wild apple orchards and abandoned forests”. The truth was that the site was so seriously contaminated, very little could be retained. The designers had to focus on delivering for the Games and creating a place for community to thrive. However, the design faced genuine jeopardy, with civil engineering infrastructure dominating and fragmenting the site.

What was needed was a step back. When LDA Design was brought in, they argued that the park was too small. The landscape had to make a decisive response at scale, and the River Lea given the prominence it deserved to bring design coherence to the Park. This was the kind of move which Capability Brown might have relished, and his lead was followed in opening and closing views, and in achieving an interaction between monumental architecture and the landscape – a 21st century picturesque.

Those campaigning against developing the site were making a powerful point, however, when they argued for the need to build from small transactions. In other words, build from how people interact with the place –first life, then spaces, then buildings. All grands projets should be rooted in

FEATURE

The power of the park has always been in its social purpose.

12.

12. The Lower Lea Valley was once the hub of London’s industry, dominated by scrap yards and tanneries, munitions factories and gasworks. © Olympic Development Authority

23

what people want from a site. The idea behind the Olympic Park was to create a sustainable community and bring new opportunity to east London. The emerging East Bank cultural quarter will be a common ground where you don’t have to spend money to feel connected. UCL East has been master planned to be genuinely accessible and useful to local people. The public realm for Here East responds to Hackney Wick’s entrepreneurial nature, with Yard spaces for artists and makers. Whether you are in the mounded, natural north of the park or the ordered, gardenesque south, there is a strong connection between people and place.

Even though the original critics of the Olympic Park longed for a London that might well never have been, to “build from small transactions” remains critically important. It’s this that makes a place lively and inclusive. The power of the park has always been in its social purpose.

Stella Bland is a director of LDA Design and head of communications. She spent six years at CABE, the Government’s advisor on architecture, urban design and public space, where she delivered the UK’s first green infrastructure conference and a festival on low-carbon living.

Lyn Kinnear Stitching the Fringe

The projects that KLA led are stitching the Olympic Fringe Legacy projects together. The design of Marsh Lane, Drapers Field, Abbotts Park and Chobham Academy supported the legacy of increasing access to sport whilst integrating the existing community of Leyton and the new community of the Olympic Park. One of the key design themes of these projects was to increase access to sport through play.

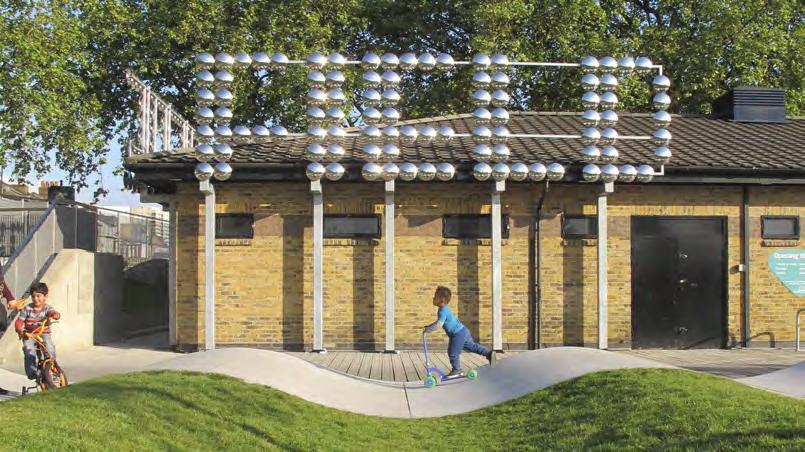

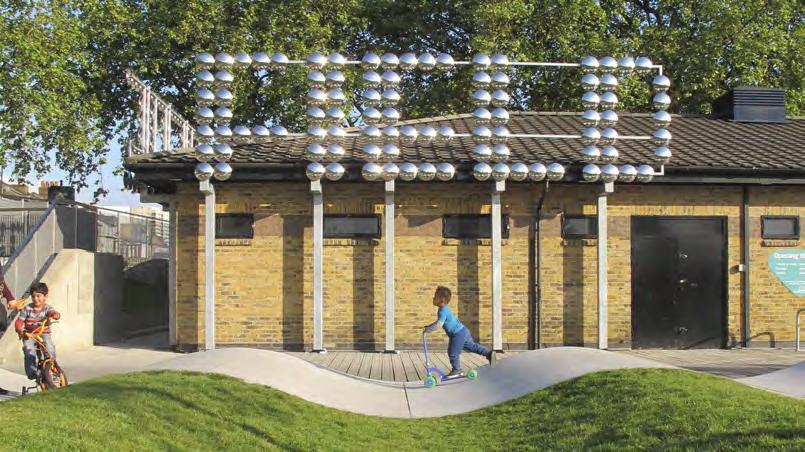

Drapers Field is a particularly strong example of this as we created a revitalised park that has a strong local design identity as well as blurring the boundaries between sport and

play. A strong design language of non-territorial and non-age specific play was created though landform and informal play, as well as creating focal points such as a concrete wave that had multiple functions: a skate area, water play and scooter practice for all ages. This was set within an undulating grass surface and new Scots pine glade.

This project was also an opportunity to show how to design an active walk to school from the existing communities of Leyton to the new all-age academy on the North East corner of the Olympic Village. KLA designed the Academy school playground, the new football pitches opposite, the raised alignment of Temple Mills Lane and new bridge, as well as Draper Field Park, and this

gave the practice an opportunity to make a new substantial piece of playful city landscape within a grove of pines on the edge of the Lea Valley.

We also used our experience of working with communities to create a focus for positive community cohesion that significantly revitalised a forgotten corner of London and supported London wide initiatives such as reducing childhood obesity.

The creation of the Olympic Park and the leading role that the profession took in its creation gave landscape architecture public visibility.

Lynn Kinnear is principal of KLA and has over 30 years’ experience as a landscape architect working in the urban realm.

FEATURE

13.

14.

24

13, 14. Concrete Waves at Drapers Fields. © KLA

FEATURE

25

15. View of the Olympic site in May 2022. © jasonhawkes.com

The Architecture of Landscape and the Landscape of Architecture

The London Festival of Architecture is increasingly at the heart of debates on landscape and placemaking as well as architecture. Its director reflects on its impact across London.

Year on year, the London Festival of Architecture stages a vibrant and diverse programme of public

events and interventions across the capital. From lectures and debates to engage and stimulate professional and academic audiences to activities for children and their families. With a rich mix of installations, exhibitions, tours, talks, performances and public realm interventions, the Festival continues to enthuse and to engage with the public, test new ideas, and celebrate and support London’s architectural and design talent.

From a personal perspective, ever since joining the team in 2016, I have been struck by the Festival’s ability to impact everyday experiences of the city: something that’s going to be needed more than ever as London continues to emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, and as we focus more keenly on the climate emergency.

Making of cities today should be a democratic act between the professionals and the public. A year ago, the Government made changes

Rosa Rogina

Rosa Rogina

FEATURE 1.

26

1. The Mobile Arboretum is a green installation designed by Wayward Plants and located in Cheapside and Aldgate, inspired by the collective history of London markets. This picture shows the installation in, Aldgate.

© Luke O’Donovan

to its planning policy framework, including a range of measures which positioned inclusive placemaking, improvements to communities’ infrastructure and beauty at the heart of the planning system. And whilst I have some reservations around the use of the word “beauty”, as its meaning is more commonly associated with aesthetic appearance rather than quality, this announcement came as a timely reminder for the industry to drive up design standards and to create more inclusive spaces that reflect and are designed in collaboration with their final users.

Ever since the first edition of the London Festival of Architecture in 2004, then titled the Clerkenwell Architecture Biennale, the Festival aims to democratise discussions around architecture and find new ways to look at familiar places. In 2004, the Festival staged a cattle drive down St Johns Street to Smithfield Market, simulating the historical market route, while two years later 15,000 people went to see Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano driving 60 sheep across the Millennium Bridge, making use of the historic droving rights of the Freemen of the City of London.

Back in 2008, the Festival stretched its ambitions further, with Exhibition Road closed to traffic for the first time to showcase new work and future possibilities. Activated with popup installations by practices including Foster + Partners and 6a Architects, food stalls and performances, the road closure served as part of the public consultation on the long-term improvements to the public realm on one of London’s key routes. The event was followed by the implementation of Dixon Jones’ pioneering shared spaces scheme ahead of the 2012 London Olympics, a pivotal moment of turning a piece of pop-up tactical urbanism into a permanent public good.

Building on the Festival’s rich legacy of urban experimentation and innovation, in recent years we have been collaborating with a variety of organisations, including leading cultural organisations, local authorities, business improvement districts and private organisations on a number of design competitions.

FEATURE

2.

3. 4.

2, 3. Exhibition Road 2008.

© London Festival of Architecture

4. Home Away from Hive by Mizzi Studio.

27

© Luke O’Donovan

From temporary seating and pocket parks to more permanent public realm interventions, these projects aim to showcase value of good design and make a demonstrable impact to the urban environment for people who live, work, and visit London. Our mission has always been to support emerging talent and showcase the difference that even a very small-scale intervention can make to our city.

To coincide with the 10th anniversary of Dixon Jones’ shared space works and in the run-up to the UK hosting the COP26 Summit in November 2021, last summer we returned to Exhibition Road to collaborate with Discover South Kensington, the V&A, Science Museum and Goethe-Institut on a design competition seeking a series of temporary greening interventions that explored greater greening and biodiversity for the road. An algae factory, a timber mound, and pieces of decommissioned wind turbine blades were introduced for a period of three months, also informing longer-term thinking about further improvements to the area’s public realm and ecology.

The after-effects of COVID-19

have made us test unknown models of using the city in many ways relatable to the urban conditions that a festival can create; from pop-up bike lanes and new pedestrian walkways to al fresco dining. And although there is a growing list of good practice examples, the last two years served as a reminder to us all that a shift to a more adequate and equal provision of access to urban space has been far too slow.

In this context, London Festival of Architecture’s 2022 theme of ‘Act’ feels particularly relevant. After such as long period of enforced passivity, the imperative to act is felt by so many of us, whether we are architects or not, while the pandemic has exposed a vast number of things that need to be challenged. One thing is certain – we need to act now. For the Festival, we have collaborated with a number of

FEATURE

5.

6.

5. Algae Meadow by Wayward and Seyi Adelekun.

© Luke O’Donovan

6. Bodies in Urban Spaces.

28

© Luke O’Donovan

London Festival of Architecture’s 2022 theme of ‘Act’ feels particularly relevant. After such a long period of enforced passivity, the imperative to act is felt by so many of us, whether we are architects or not, while the pandemic has exposed a vast number of things that need to be challenged. One thing is certain – we need to act now.

London Boroughs on the delivery of engaging public realm interventions as part of our competitions, including Somers Town Acts with Camden Council and Pews and Perches with the Royal Docks.

Both projects take into account the imperative to act. Somers Town Acts project involved developing a creative temporary installation along Phoenix Road, which is planned to be transformed as part of the Greening Phoenix Road project. Design proposals took into consideration aspirations that have emerged through community engagement, including creating a space that moves from grey to green, safe and accessible for all, sociable, well-connected, and that reflects the unique character of Somers Town.

Pews and Perches invited architecture, design students, and recent graduates, to deliver five playful benches that celebrate and transform the Royal Docks as a place to sit, rest and play. Now in its third year, the project highlights the transformative impact of small-scale interventions in the public realm and showcases design solutions that reflect on how architecture should act in the face of climate emergency, social injustice, and the needs of a changing society.

Due to their temporary nature, festivals can often be distanced from the life of the cities in which they are held. Yet, it is precisely their temporal dimension that can offer opportunities for festival producers and participants to experiment, test ideas and negotiate change.

Rosa Rogina is an architect, researcher and curator currently working as Director at London Festival of Architecture, leading on development, curation and delivery of the Festival’s annual programme. She has previously worked for MVRDV, Grimshaw Architects and Farshid Moussavi Architecture. Rosa has co-curated the Montenegrin Pavilion at the 2018 Venice Biennale and has been curator in residence at Vienna Design Week 2020.

FEATURE

7.

8. 9.

7. Happy Street Rail by Yinka Ilori.

© Luke O’Donovan

8. Monuments to Mingling by Sohanna Srinivasan, for City Benches, City of London.

© Agnese Sanvito

9. Water Water Everywhere by Betty Owoo and Quincy Haynes.

© Luke O’Donovan

29

Refocusing on beauty in the planning system

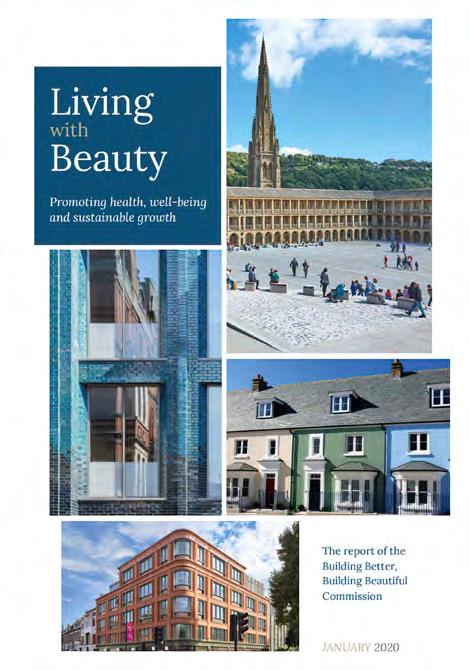

Living with Beauty, the report of the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission attempted to put beauty at the heart of planning. Two years later, Kate Bailey looks at whether this idea can be salvaged.

FEATURE

30

I have to admit that, when it’s uttered by government ministers and their advisers, the word ‘beauty’ sets my teeth on edge. I can’t accept that a consistent ideal of ‘aesthetic beauty’ is shared by different cultures and sectors of society, nor that it can be mandated by the adoption of new rules for a planning profession that is rarely design-trained. Personally, I was dismayed by the (effectively abandoned) Planning White Paper proposals (2020) to “draw inspiration from the idea of design codes and pattern books that built Bath, Belgravia and Bournville.”

A quick online search reveals the extraordinary diversity of architectural styles across regions

and nations around the globe. Reviews of award-winning modern buildings mention simple forms, flowing lines, inspirational spaces and the penetration of natural light more often than ‘beauty’. To me, the Sydney Opera House is instantly recognisable; the Icelandic church in Reykjavik is an inspired landmark; the Marina Bay Hotel in Singapore is a technical marvel; Frank Lloyd Wright’s ‘Fallingwater’ house is an architectural masterpiece; and the delightful Frank Gehry ‘Dancing House’ in Prague brings a smile to my face. But can any of these famous examples be said to be ‘beautiful’ in any conventional sense? Might some people describe them as ‘ugly’?

Architectural preferences are personal and, in my view, style is the least interesting aspect of building design. I was always taught that form follows function and I agree with Ray Eames – “the ‘looks good’ can change, but what works, works.” If a building is designed well, at a human scale, with high quality modern materials and practical, comfortable spaces

inside and out, then it will become an attractive home for someone regardless of any superficial details added to the front face.

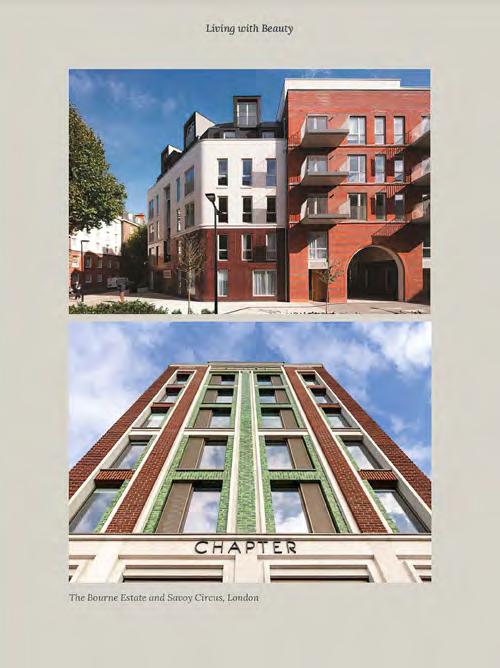

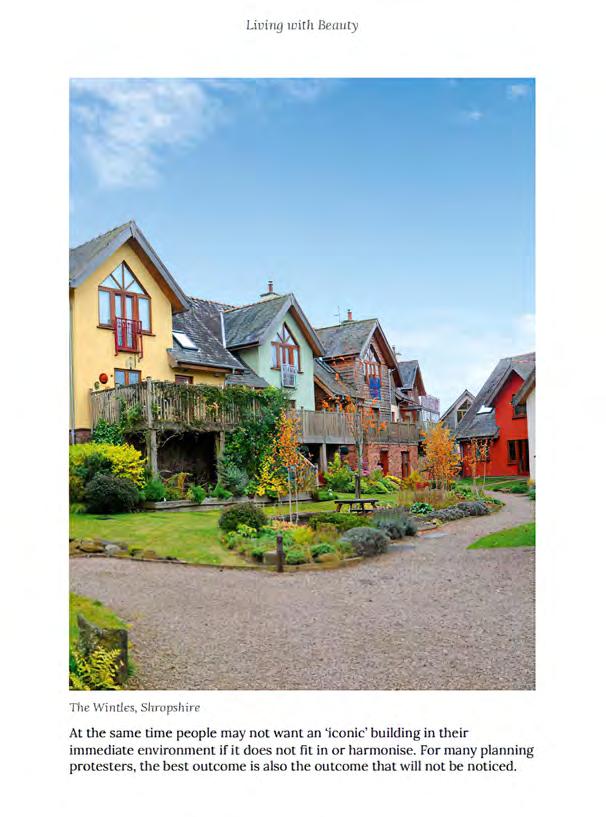

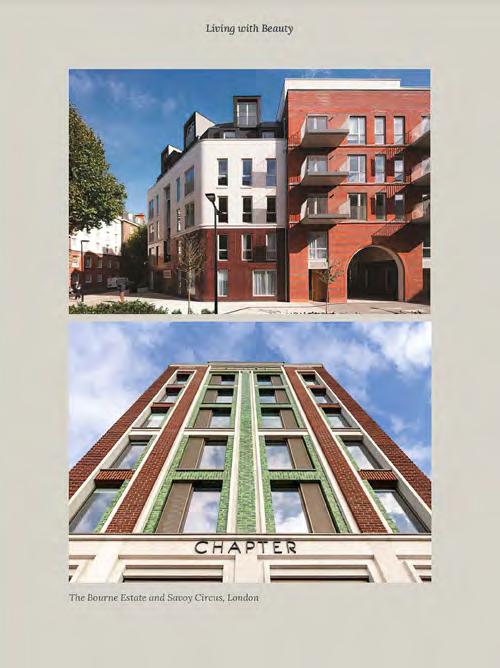

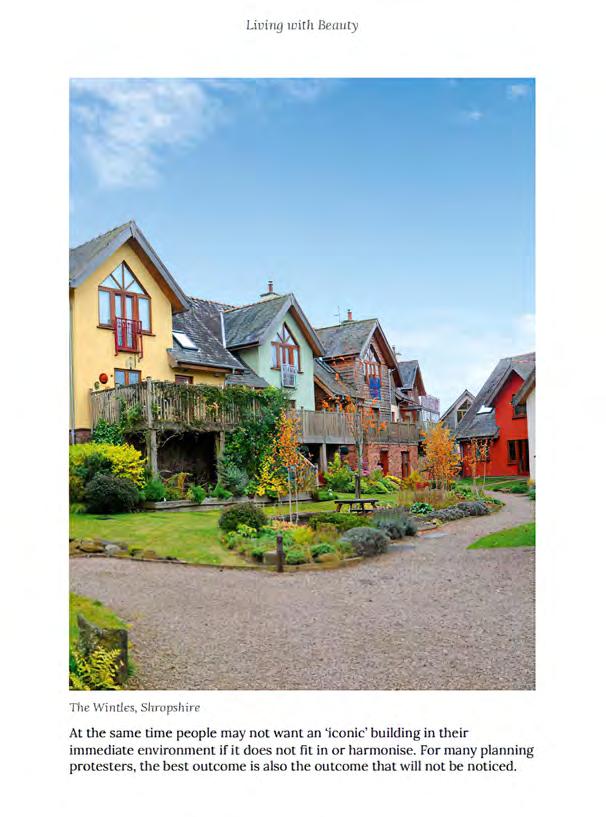

You may remember that the purpose of the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission was “to tackle the challenge of poor-quality design and build of homes and places, across the country and help ensure as we build for the future, we do so with popular consent” (Commission terms of reference). Their final report ‘Living with Beauty’ (2020) is illustrated with examples of fine buildings that are, on the whole, relentlessly symmetrical (The Piece Hall, Halifax), often in high density urban locations (Savoy Circus, London), reflecting Georgian proportions (Bourne Estate), or in romantic rural settings (vivid sunset over Malmesbury), or ‘pastiche’ villages (The Wintles, Shropshire). These images demonstrate a distinct preference for the charming, the rural, the nostalgic – and a very firm dislike of the modern, the innovative and the utilitarian.

The BBBB executive summary does, however, offer some important

FEATURE

Kate Bailey

1. Cover of the report of the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission from which all images for this article have been taken.

© Department for Levelling Up Communities and Local Government

31

1.

advice: “We advocate an integrated approach, in which all matters relevant to placemaking are considered from the outset and subjected to a democratic or co-design process ... We advocate a radical programme for the greening of our towns and cities, for achieving environmental targets, and for regenerating abandoned places.” Phew! I’m not sure that design codes will achieve the desired result, but at least the title of the report has a sub-heading that the LI can support: ‘Promoting health, well-being and sustainable growth’.

The ‘Planning for the Future’ White Paper (2020) was heavily influenced by the BBBB Commission. It talked about a “fast track to beauty” of “high quality developments where they reflect local character and preferences.” Local preferences? I would suggest that many homeowners fiercely defend the style of house that they themselves chose because they’ve sunk their savings into it and their children have grown up there, even if it’s draughty, leaky, old fashioned, costly to heat and their children have left home. Is it unkind to describe them as unimaginative and resistant to change?

The planning process has long been concerned with local character and appearance, but it achieves wildly varying outcomes in different postcode areas. The new Design Codes are intended to define what is or is not acceptable in planning terms, but does anyone know how to deliver house designs that are “provably popular”? If we look around recent housing estates, what is ‘popular’ tends to include cars parked on front gardens, high fences for privacy and a distinct absence of trees that would potentially drop leaves onto their front gardens.

In 2021, during the pandemic, the Housing, Communities and Local Government (HCLG) Parliamentary Committee considered the Government’s proposed reforms to the planning system (‘Planning for the Future’ 2020). The Committee’s report of June 2021 ‘Future of the Planning System’ advised the government that the enhancement of design and beauty in the planning system “needs to consider a broader definition of design than one focused on aesthetics. This

should include ensuring innovations in design are not unduly stifled and the subjective nature of beauty is recognised.”

When considering evidence on design and beauty (section 10), the HCLG Committee was told that “it is clearly not a legitimate purpose for the planning system to impose the personal stylistic preferences of the more vocal members of the community on the wider community.” Their overall recommendation in this section was that “the Government must ensure that its [design policies] reflect the broadest meaning of design, encompassing function, placemaking, and the internal quality of the housing as a place to live in, alongside its external appearance. Given the problems with defining beauty, and to ensure a wider approach to design, there should also not be a ‘fast track for beauty’.”

During many years of facilitating community engagement workshops in different locations, I often concluded that the main reasons that the people with the loudest voices objected to proposals for new housing estates related to the numbers of additional dwellings proposed for an established neighbourhood, suburban area or rural village. Protesters often focus on the perceived pressures of more cars on their roads, the numbers of additional people who will overwhelm their utilities and local facilities, and the ‘vast’ areas of greenfield land that are being built on. Green Belt policies are robustly supported not because Green Belt land is beautiful (much of it is neglected grazing land), but because such policies provide an

effective mechanism for keeping new development at bay.

However, in many rural locations, where property prices are high and many houses are used infrequently as second homes or holiday lets, this new requirement for the planning system to deliver beautiful new homes seems to me to be neglecting the valid concerns of existing communities. As a ‘Places Matter’ Design Review panellist, it is clear to me that many proposals for new housing fail to take account of the needs of the whole community and the wider environment, particularly where development will place increased pressure on under-resourced local services such as schools, health facilities, parks and public spaces.

For me, one of the few positive consequences of COVID lockdowns has been a welcome shift in our conversations about new housing

FEATURE 32

Our ambition should be to become the most trusted of all the built environment professions to deliver healthy multifunctional spaces and places, that can be appreciated as beautifully designed, at the same time as providing climate-resilient environmental and social benefits for the communities we serve.

developments, with greater emphasis on access to local services, walkable neighbourhoods, priority for pedestrians and cyclists over vehicles, outdoor spaces for health and exercise, contact with nature and biodiversity gains.

The most recent Queen’s Speech referred to the DLUHC ‘Levelling up and Regeneration’ policy paper (published 11 May 2022), which will hopefully go some way towards addressing these issues. “In the Bill – we have taken important steps to make sure that good design which reflects community preferences is a key objective of the planning system, reflecting the important recommendations of the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission. This includes the National Model Design Code and stronger national policy on the importance of good design; changes which are already having positive effects.”

(DLUHC 2022)

It is to be hoped that the DLUHC Minister Michael Gove can find a way to resolve the apparent tensions between the planning emphasis on codified design and beauty, the failure of the housing market to provide affordable and liveable places for diverse groups of people, the Defra/ Environment Act emphasis on biodiversity net gain and nature recovery, and the BIES focus on energy security and the current government’s ‘Plan for Growth’.

I would suggest these mixed messages point to the need for the landscape profession to focus the attention of our clients and allied professions firmly on providing an urgent and consistent response to the climate and biodiversity emergencies. The DLUHC minister has accepted that planning for a sustainable climateresilient future means considering “all matters relevant to placemaking”

(BBBB summary). We know, and must continue to advise, that successful placemaking also means listening out for, and taking account of, the views of under-represented groups within our society in order to understand what ‘beautiful’ design means to their local communities.

Our job is to create beauty in the

places we design for everyone to enjoy. We do this by masterplanning with nature-based solutions, by codesigning attractive, multifunctional and healthy residential and commercial environments, and by contributing to design codes that promote the creation of sustainable, climate resilient and ecologically rich neighbourhoods.

Our ambition should be to become the most trusted of all the built environment professions to deliver

healthy multifunctional spaces and places, that can be appreciated as beautifully designed, at the same time as providing climate-resilient environmental and social benefits for the communities we serve.

FEATURE

Kate Bailey is chair of the Landscape Institute Policy Committee, writing in a personal capacity.

33

The leading line: a new generation of design codes

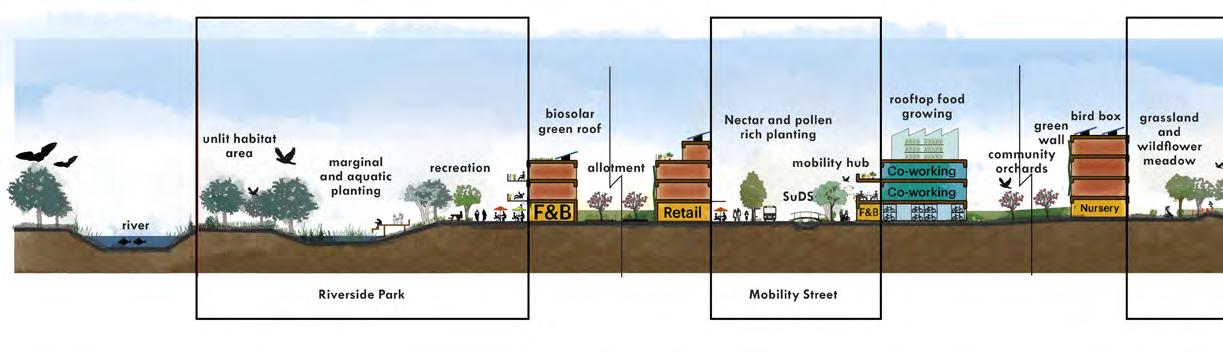

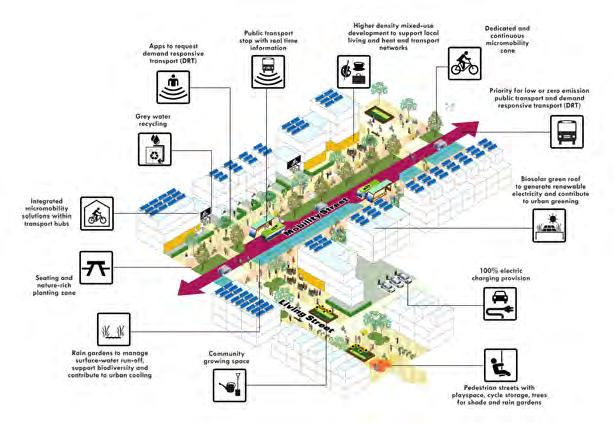

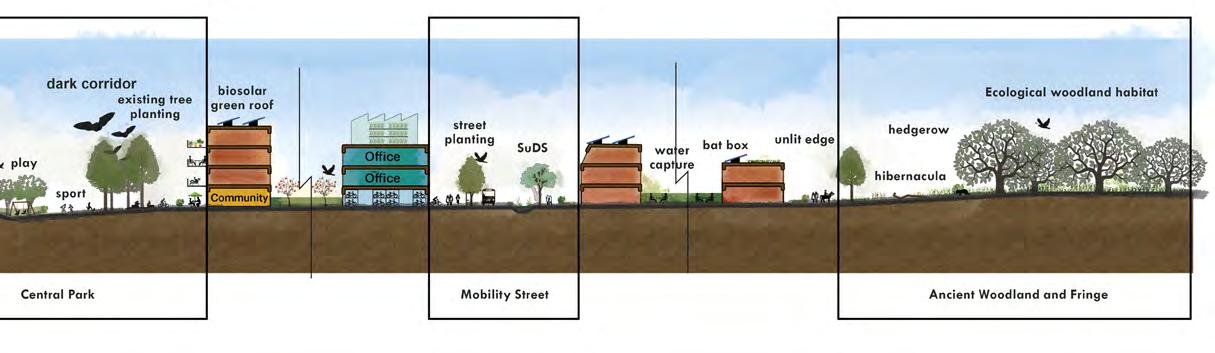

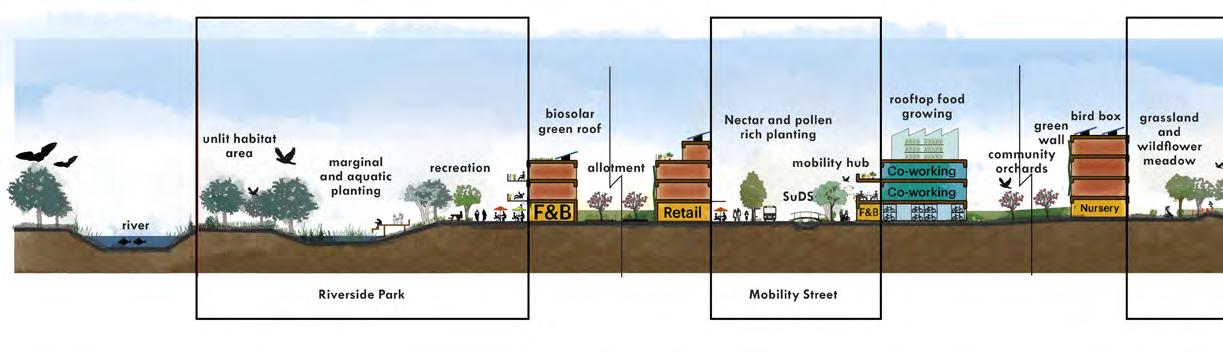

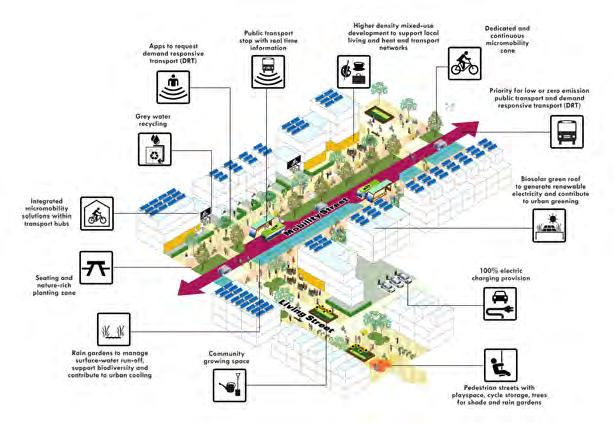

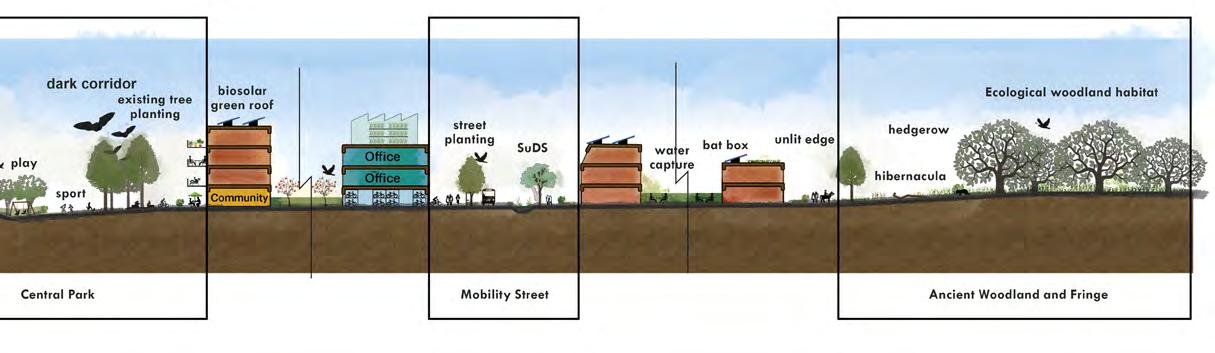

What needs to change for net zero and nature recovery to become the starting point for all new development? One answer could be a new generation of design codes with environmental vision.

Tom Perry