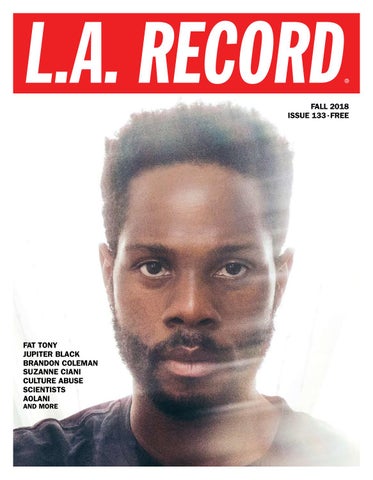

L.A. RECORD

®

FALL 2018 ISSUE 133 • FREE

FAT TONY JUPITER BLACK BRANDON COLEMAN SUZANNE CIANI CULTURE ABUSE SCIENTISTS AOLANI AND MORE

L.A. RECORD

®

FALL 2018 ISSUE 133 • FREE

FAT TONY JUPITER BLACK BRANDON COLEMAN SUZANNE CIANI CULTURE ABUSE SCIENTISTS AOLANI AND MORE