7 minute read

Alcuin of York

Philip Goddard looks at the life of a remarkable English scholar

Until around 1970 the most important books on the Catholic family’s bookshelf were the Holy Bible and the Roman Missal. For traditionalists they still are. I wonder, though, how many Catholics, traditionalists or not, are aware of how much of the 1962 Roman Missal can be attributed to the work of one man, and an Englishman at that?

The precise year of Alcuin’s birth in York is not known, but it must have been around 735, the year in which St Bede died. His talents were recognised at an early age, and in 766 he became Master of the Cathedral School, where he had himself been educated, as well as Librarian of the Cathedral Library. He occupied this position for some fifteen years, until, on a visit to Italy in 781, he met the man in whose service he was to spend the rest of his life, Charles, King of the Franks, who is known to history, flatteringly, as Charlemagne. Charles’ father was Pepin, known to history, somewhat less flatteringly, as Pepin the Short, who in 747 had become sole ruler of the Frankish Empire.

When Pepin died in 768, his kingdom was divided between his two sons, Carloman and Charles. Carloman died in 771 and Charles became sole ruler. In 774 he visited Rome, where he received the title “King of the Franks and Lombards and Patrician of the Romans” from the Pope. It was Charlemagne’s great ambition to introduce the benefits of civilisation to the semi-barbarous Frankish court. He was therefore on the lookout for men of learning whom he could conscript into supporting him in this task. He decided immediately that Alcuin was just the right man, and succeeded in persuading him to move to Aachen, his capital, as tutor to the royal family and household.

Charles had chosen well. Alcuin not only thoroughly revised the curriculum of the palace school in line with English schools but wrote or rewrote the textbooks himself. However, he was no mere schoolmaster but a deeply learned scholar and, like St Francis after him, a great humanist long before the advent of the Renaissance. He took the same delight as Francis in the physical world in all its aspects, as God’s creation for our use and enjoyment. This emerges strongly in his poetry, of which he wrote a good deal, in the classical metres perfected by the great Roman poets. His themes were the glory of God, the beauty of nature and its transitoriness. His prayer on retiring to bed deserves to be widely known (and used):

His love of nature and his sorrow at its transitoriness is well illustrated in his lament for his lost nightingale and its sweet voice:

His poetry can also display a sharp sense of humour. On one occasion he received a note from his friend Samuel, Bishop of Sens, to the effect that he was planning a visit. This was highly inconvenient at the time, since Alcuin’s household was suffering from the effects of a particularly poor harvest. But Alcuin, instead of simply writing a letter asking him not to come, sent him a poem, in which he appealed to the good bishop’s well-known fondness for good living:

Charles’ father, Pepin, had been an enthusiastic Romaniser of the liturgy. In 753 Bishop Chrodegang of Metz had visited Rome and had persuaded Pope Stephen II to return with him. Stephen’s visit, during which he anointed Pepin and his two sons, Charles and Carloman, as Kings of the Franks, lasted from 753 to 755. This long papal visit enabled the local clergy to familiarise themselves with the nobility and dignity of the Roman rite, and the beauty of its chant, and thus supplied a powerful incentive towards its adoption. Charles continued his father’s policy. But the universal adoption of the Roman rite was severely hampered by a great shortage of suitable books. In an admonition dated 23 March 789, Charles complains of the poor quality of the existing liturgical books, and urges that the task of copying them be undertaken by older men, exercising the greatest care in their work. At about the same time he requested Pope Adrian I to send him a Roman sacramentary. Adrian sent him one which he described as “ immixtum” (i.e. a pure sacramentary of the papal rite, untainted by external elements), known to history as the Hadrianum.

But there was a problem with the Hadrianum. It was a purely papal sacramentary; it contained the liturgy only for the stational days, when the Pope was accustomed to celebrate Mass in one of the stational churches of Rome, and for papal feast days. It did not include any Masses for the ordinary Sundays of the year. Charlemagne therefore gave Alcuin the task of supplementing

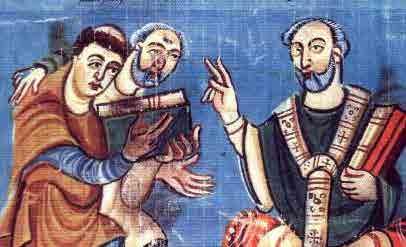

Bishop Otgar of Mainz with Alcuin of York (centre) being introduced to his pupil Rabano Mauro from a Carolingian manuscript of 831

the papal sacramentary by adding Masses for the ordinary Sundays of the year and non-papal feast days, drawing on both Roman and Gallican sources, and composing additional votive Masses himself. At the same time Alcuin also undertook the task of revising the Roman Lectionary for the use of the Gallican Church. The result was a hybrid Romano-Gallican liturgy, which eventually replaced the local rites throughout the Frankish kingdom. Such was the reverence which the papal sacramentary inspired that originally the Hadrianum and Alcuin’s supplement (the “ Hucusque”, as it became known) were kept strictly separate, but as the years went by they were gradually merged. Towards the end of the tenth century this Romano-Gallican liturgy was adopted in Rome itself, and from there it spread throughout the West. A large number of additions were made over the intervening centuries, particularly Masses for new feasts such as Corpus Christi, the Sacred Heart and Christ the King, as well as extra celebrant’s prayers such as those recited at the Offertory, but notwithstanding this the core of the 1962 missal which we still use today is the work of Alcuin of York.

In 796 Charlemagne appointed Alcuin Abbot of St Martin’s Abbey in Tours, where he remained for the rest of his life. At Tours he established a school, whose pupils included some of the most important scholars of the early mediaeval period, to whose commentaries we owe so much of our knowledge of the liturgy of the time. He also encouraged his monks to perfect the Carolingian script which, as a result of its adoption by Renaissance scholars, is the ancestor of our modern scripts. When, in 800, Charles was crowned Holy Roman Emperor, Alcuin presented him with a complete Bible, written in his own monastery scriptorium, the text of which had been corrected and purged of errors by himself. And being the man he was, he still found time to appreciate the local wines.

While he was at Tours he became involved in the controversy surrounding the Adoptionist heresy. The Adoptionists claimed that Our Lord was not the true Son of God but merely His adopted son. One of its leaders was Felix, Bishop of Urgel, and Alcuin wrote a defence of the orthodox doctrine, Contra Felicem, in seven volumes. As a result, Felix’s teachings were condemned and he recanted.

Alcuin never returned to England. In old age he thought much about his approaching death, and these thoughts are reflected in his verse, for example in a poem addressed to Archbishop Adelhard of Canterbury:

Shortly before his death, which occurred in 804, he wrote his own epitaph:

Next time you open your copy of our beloved Roman Missal, think of that great Englishman, Alcuin of York, and say a prayer of thanksgiving for his life and work, which endures to this day.

The translations of Alcuin’s poems are by Helen Waddell, taken from “Mediaeval Latin Lyrics” (Penguin Classics, 1952) and “More Latin Lyrics” (Gollancz, 1980).