7 minute read

St Thomas of Canterbury and the English Martyrs

Paul Waddington visits one of Preston’s most interesting churches

Until the closure of St Augustine’s Church in 1984 (and later demolition), Preston had no fewer than 17 Catholic churches, and this excludes the churches in suburbs south of the River Ribble, which are not strictly within the current city boundaries. Of these, six are (or were) large impressive buildings located close to the city centre, and dating from the middle years of nineteenth century. The largest of the central churches is the Church of St Walburge, which was described in an earlier article in this series. This article concerns the Church of St Thomas of Canterbury and the English Martyrs, which was opened in 1867 and was the last of the six to be built.

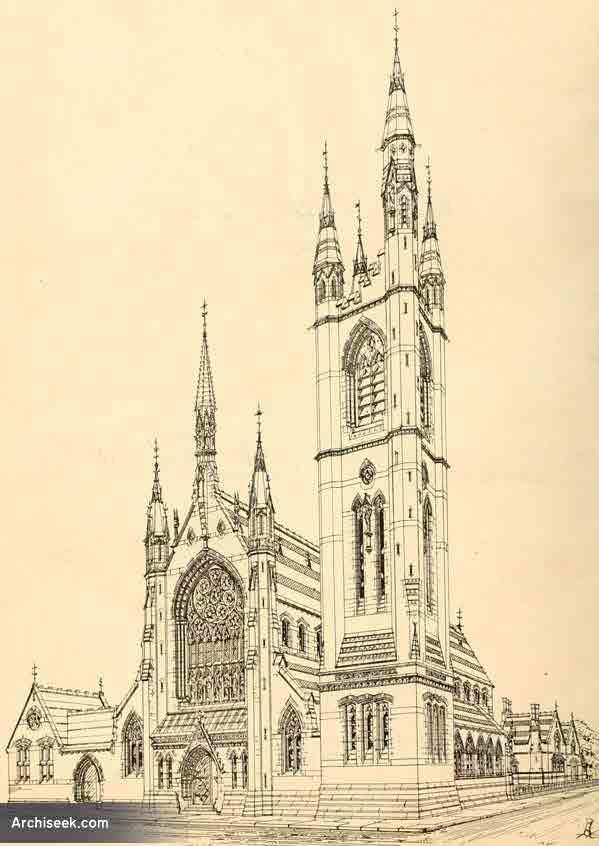

Sketch of EW Pugin's original design showing West End with proposed tower

The site chosen for English Martyrs Church (as it is usually known) is an historic one. Formerly known as Gallows Hill, it was the place of execution of sixteen of the leaders of the Jacobite Rising of 1715. A century later in 1817, Garstang Road, which is the main road leading north from Preston, was widened and its gradient eased, which necessitated the levelling of much of Gallows Hill. During the excavations, the skeletons of two headless bodies were found, as well as some timbers, which were thought to be the remains of the gallows. Another 50 years later the remaining part of Gallows Hill was levelled to make way for the building of the English Martyrs Church.

The exterior of the church today

In 1864, Bishop Alexander Goss of Liverpool* sent Fr James Taylor to establish a new church to serve the northern part of Preston. A temporary chapel was soon established in the stables of Wren’s Cottage, a several hundred yards to the north of the present church. Fr Taylor bought land at Gallows Hill, had it levelled, and engaged Edward Welby Pugin to design a permanent church. Pugin’s design was for a Gothic church built of rustic sandstone with a five bay nave and apsidal chancel. As was Edward Pugin’s practice in this period, the aisles to north and south were only used for circulation, so that the whole congregation could see the altar. He also designed a tower with four spirelets to stand at the southwest corner, but this was never executed.

Building started in time for Bishop Goss to lay the foundation stone in 1866, and was sufficiently advanced for the bishop to return in December 1867 for the opening ceremony. It had cost £8,000.

Western facade

Externally, the most striking feature was, and still is, the west end, which included a very large eight light window with intricate curved tracery. Mounted on the gable above the window, were a trio of prominent spirelets, decorated with niches and blind arches. These closely resembled the intended spirelets of the proposed tower. Pugin added statues to the tallest spirelet, which is corbelled from the apex of the west window in a manner that he used on several other churches. As a composition, the western facade is impressive, and would have been even more spectacular if the tower had been built. The nave was some 50ft to the apex, sufficiently high to allow tall lancet windows at clerestory level. The chancel had pairs of two light windows high in each of its five walls. Beneath, there were large oil paintings, and at floor level a row of statues of saints and martyrs. Naturally, there was a fine stone altar with reredos.

In 1874, Fr Taylor moved on to build other churches elsewhere in Lancashire. He was replaced by Fr Joseph Pyke, who soon decided that the church should be enlarged, and asked Edward Pugin to return and design an extension. Unfortunately, Edward Pugin died before any work could be undertaken, but the project was passed to his younger brother, Cuthbert, and his half-brother, Edmund Peter (known as Peter Paul). In partnership as Pugin and Pugin, they took down the apse at the eastern end, and extended the nave by two bays. They also added transepts and a new and enlarged apsidal chancel, which was under a differentiated roof line. The result was to increase the seating capacity by a third, as well as providing side altars in the transepts and a more generously sized sanctuary. The foundation stone for the extension was laid by Bishop Bernard O’Reilly in 1887, and the work was completed in 1888 at a cost of a further £8,000.

The extended church is large, with a seating capacity of 850. The round columns of the arcade have foliated capitals and are tall and slim, which serves to emphasise the considerable height of the building. Above the arcading, lancet windows (two per bay), together with the large west window, supply plenty of natural light, giving the church a spacious feeling. The ceiling is nicely finished with the spaces between the roof trusses filled with planking to form a sort of wagon roof.

The remodelled sanctuary

Interior decoration

Unlike the earlier design, the new chancel was separated from the nave by a chancel arch, from which was suspended a rood with the figures of Our Lady and St John at either side. The floor level of the sanctuary was raised, giving the altar greater prominence. The walls of the new sanctuary were arranged in three tiers, the lowest one being plain stone. Above, the statues of saints and martyrs were reinstated, and at a higher level, each of the five walls of the apse has a pair of two light windows containing stained glass, but with sufficient clear glass to provide plenty of natural light. The oil paintings were not reused in the remodelled church.

The high altar was reinstated, but with a more elaborate reredos incorporating an impressive monstrance throne, surmounted by an ornate canopy in the shape of a spire. Pugin and Pugin, as always, proved themselves masters of interior decoration. They were able to reuse much of Edward’s work, such as the rood, the statues of saints and martyrs and the windows, and yet improve on the design.

The church had to wait until 1921 for its consecration, indicating that it took a long time to pay off the debt. Since then, it has remained relatively intact, escaping the worst excesses of postVatican II reordering. The creation of a narthex beneath the choir loft in 1964 must be considered an improvement, as perhaps can the relocating of the baptismal font to its current position in the centre aisle.

What is most pleasing for the present day visitor, is the survival of many original Pugin features, which in many churches have been jettisoned in the name of post-Vatican II liturgical practice. These include the high altar, the marble altar rails with their gates, and the marble pulpit, which stands on pillars and is complete with its wooden tester. Another interesting feature is the war memorial chapel with an impressive number of names of fallen heroes of the First World War.

Act of confidence

In the year 2000, a new community room was added. This was an act of confidence at a time following years of declining congregations, largely due to slum clearance and the migration of former parishioners to new housing estates where new churches had been built. Nevertheless, the decline continued. In 2012 the presbytery was sold, there no longer being a resident priest; and in 2014, the parish was merged with those of St Ignatius and St Joseph, and renamed the Parish of St John XXIII. The future for the church, and the other churches in central Preston was looking very bleak.

Bishop Campbell celebrating Mass in September 2017

Bishop Michael Campbell OSA, Bishop of Lancaster since 2008, has been very determined to secure the future of Preston’s central churches. He arrived too late on the scene to save St Augustine’s, but did manage to save three others. He handed over the care of St Walburge’s to the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest in 2014 and the Church of St Ignatius’ to the Syro-Malabar community in 2015. In September 2017, he entrusted the English Martyrs Church to the ICKSP, marking the occasion by celebrating a Pontifical Solemn Mass. The ICKSP now offers daily Mass in the Extraordinary Form at both its churches in Preston.

* Preston was in the Diocese (later Archdiocese) of Liverpool until 1924, when the Diocese of Lancaster was erected.