7 minute read

A problem for novelists

Joseph Shaw on the difficulties of writing Catholic fiction

In the last issue I reviewed William Whyte’s Unlocking the Church, about the movement, within Anglicanism and from about 1830, for a form of church architecture and corresponding programme of church restoration, which saw churches as sacred spaces, so filled with symbolic references that they could be read like a book. It might sound a dry subject but it aroused fierce passions at the time, and among other manifestations it gave rise to an entire sub-genre of novels and poetry.

The Tractarians and others involved in the debate decided that in order to made the points they wished to make, they needed to employ a wide range of literary forms. The great majority of their fiction output was—according to Whyte—terrible, from a literary point of view. It is hard to know how much of an impact it had in its day: it is all long forgotten now, although the related output of John Henry Newman, such as his novel Loss and Gain, is still read today. But it is a natural thought that fiction, as well as non-fiction writing, should play a part in the spreading of a theological message, and bridge the gap between the abstract and the personal, the academic and the popular.

One reason why the Tractarian novelists and poets wrote such bad stuff was that they were amateurs. Another, however, is specific to the task they had set themselves: of trying to persuade their readers of a laundry list of abstract theological points through the pages of their books. It is extremely difficult to do this while still penning a convincing story. The reader of a novel must be interested in the characters in the story to carry on reading, and if events are being driven by ideological necessity rather than by psychology, or if the action is interspersed by clumsy editorial comment, then the book ceases to be interesting.

This is a problem for novelists of all ideological persuasions, and catches up even with professional writers. This may sound surprising, because fiction is such a powerful medium of persuasion, and has been used to such devastating effect in our own lifetimes to attack the traditional family and gender-roles, the historical role of the Church, and so on. But these attacks have been most effective when they have been oblique. Thousands of films presenting traditional domestic life as an intolerable servitude for women, for example, have left their mark on society precisely because they did not proclaim their ideological distortions in the opening credits, but aimed, primarily, to tell an entertaining story and make money. The new generation of directors who can’t touch a Star Wars episode, Disney re-make, or Agatha Christie adaptation, without turning it into anti-patriarchy shout-fest, simply turn off their audiences.

We are fortunate, in the English language, to have superb authors who tell stories which reflect a subtle but all-pervading Catholic vision of the world and of human nature, in a way which is not off-putting to non-Catholics: Chaucer, Shakespeare, Dryden, Alexander Pope, Chesterton, Evelyn Waugh, Tolkein, and Graham Greene in his good moments. We do, of course, need new ones, to tackle the issues, genres, and needs of each new generation. In the Traditional Catholic movement, we even have a few novels which address the liturgical crisis more directly. I have in the past reviewed Natalia Sanmartin’s wonderful The Awakening of Miss Prim; earlier, there was the more lightweight but entertaining Smoke in the Sanctuary by Stephen Oliver, and from an earlier era, Alice Thomas Ellis’ The Sin Eater, and the profound and moving Judith’s Marriage by Fr Bryan Houghton, which I gather will soon be back in print, with his other two works, Mitre and Crook and Rejected Priest.

Of all these, only Miss Prim and The Sin Eater are books one could give to a non-trad, let alone a non-Catholic. Even with Miss Prim one would be taking a risk, not because the needs of the message have overwhelmed the needs of the story, but because of the Catholic setting. One can hardly forget that Catholic matters are at issue in the story, when it is set in a sort of Catholic colony, though even this is done with a very light touch. One can avoid even this, like my brother’s Ten Weeks in Africa (written under the name J.M.Shaw), but obviously it is difficult to drill into the most detailed Catholic issues without letting on. This task is handled in a very unique way by the American Catholic convert of an older generation, Flannery O’Connor.

I wish the best of luck to Catholics writing now, particularly those of a traditional cast of mind who see that what afflicts the human spirit today is, as it always has been, the absence of God’s grace, and that those significant chance events which mark the turning points of our personal narratives are those in which created things are called upon to play a role in grace’s work. The novelist’s task is to make that process comprehensible, without making it appear crude and obvious. To see the Lord of History at work while respecting the autonomy of each human agent is not an easy task: it is a divine one.

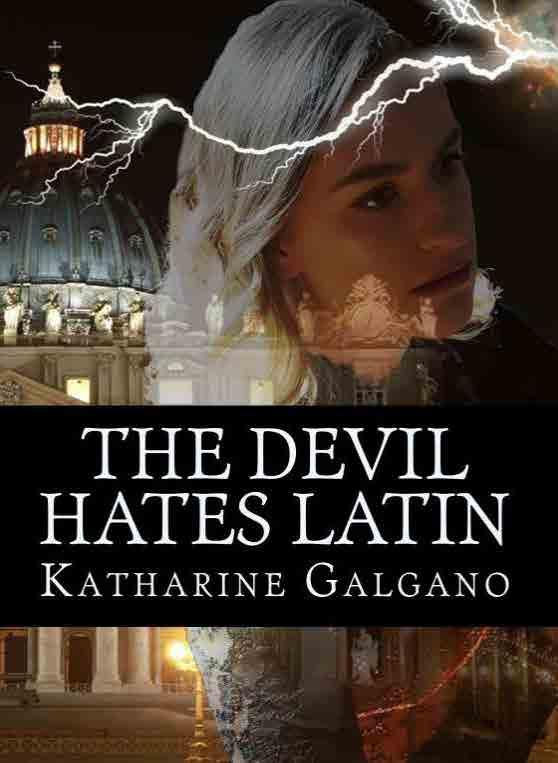

The Devil Hates Latin by Katherine Galgano

From the general to the particular, I turn to this novel set in a somewhat fictionalised present. The author (the book is pseudonymous) informed me that this was just ‘a bit of fun’, what a traditional Catholic might read without much effort in the evenings, and one should certainly see it in that spirit. It does not aspire to great literary perfection or psychological profundity, but it hangs together as a story, it is not over-long, and I, for one, found it as entertaining as it was unpretentious.

It is set in and near Rome, and although most of the protagonists are non-Italians, it takes as its starting-point the social crisis gripping Italy. Italy is a pleasant place to holiday, strewn with wonderful Baroque churches and classical ruins, but the country is in deep trouble. The Italians, to put it simply, are not forming families and having children. The motives of the various characters in the story which impinge on this question are well-observed, as is the struggle of the Italian family at the centre of the action to free itself from attitudes which, at bottom, are incompatible with the emergence of a new generation.

Another theme which may be surprising is the attraction of what looks like a Catholic restorationist project but which is, it turns out, fake. It is a sad reality that, as it has become impossible to trust the orthodoxy or moral probity of many Catholic institutions associated with dioceses and long-established religious orders—whether schools, seminaries, or anything else—it has been no less necessary to treat new institutions, often proclaiming their traditional outlook and orthodoxy with trumpets, with extreme caution.

The example in the book is clearly inspired by the Legionnaires of Christ. I fancy that the relative lack of success which this and similar institutions have enjoyed in the UK is largely due to the fact that the cult-like ‘hard sell’ they employ is such a massive turn-off over here. But that isn’t the heart of the problem: it is their attitude to the Catholic tradition, not as to an object worthy of veneration and therefore of preservation and continuation, but as a box for tools which may or may not prove useful. This item, taken out of its original context, might serve to keep the faithful in awe of the clergy; that one looks good in photographs; this one over here can be used to make potential whistle-blowers quiet: but let’s leave alone that other one, the local bishop doesn’t like the old Mass. Under the name of discernment and creativity, they have adopted an attitude of the manipulative instrumentalisation of holy things: a form ofSimony, a trade in the means of grace.

The Devil Hates Latin weaves something of a thriller-plot out of these materials, with a bold supernatural climax. I don’t say this climax is wholly successful: the incorporation of the supernatural into a naturalistic novel is a very tough trick to pull off. However, it is an interesting attempt and wraps things up nicely; the reactions of some of the villains to it is a very good touch.

Overall, I recommend this novel as, in the author’s words, a ‘bit of fun’: not to be taken too seriously in literary terms, but part of an interesting and necessary debate on human nature, the Catholic tradition, and how normal life can be restored in our own dark times.

The Devil Hates Latin(315pp; Regina Press) is available from the LMS shop, £14.99 + p&p.