the pioneer

Editorial

Dina Abdul Rahman

A Word from the MEPI-Tomorrow’s Leaders Executive Director

File

Lina Kreidie

A Note to Our Students

Rena Haidar

The Gender Agenda of Civil Society Organizations in Lebanon: Intervention Constraints and the Absence of Cooperation and Action

Tonia Chahine

Listen to Women: Gender Bias in Clinical Pain Management

Melissa Bou Zeid

The Influence of Quotas on Promoting Women in Decision Making Positions

Maria Abi Akl

Unpaid Care Work in Lebanon: A Barrier to Women’s Economic Empowerment

Lynn al Jamal

Reallocating Soft Power in Sports: From Political Agendas to Sustainable Peace and Development

Rita Mroue

Automation and Gender

Shella Marcos El Douaihy

Women in Financial Technology: A Lack of Participation in Blockchain

Kassem Fattah

Queer Coding and Misrepresentation in Arab Media

Wafic Khalife

Social Media: A Curse or a Blessing?

Reina Al Sayegh

The Aftermath of Sexual Assault in Warfare: Analysis of UN Security Council Resolution 2467

Gheed Khiami

Inclusion of Women in Negotiations: The Syrian Women’s Advisory Board and the Yemeni Women’s Technical Advisory Group

Lyne Sammouri

The Role of Palestinian Women in Israel-Palestine Peace Negotiations

Contents

47 No. 1 (2023) 01 The Arab Institute for Women Lebanese American University 96

Vol

02 03 4 5 12 18 26 34 40 47 52 59 64 69 75

A Word from the MEPITomorrow’s

Leaders Executive Director

I have been working on MEPI Tomorrow’s Leaders-funded programs since 2015. By far, the Tomorrow’s Leaders Gender Scholars (TLS) program has been one of the most powerful and impactful to date.

Since 2020, LAU enrolled almost 400 TLS scholars, all of whom have successfully completed the one-year program requirement. Our TLS alumni not only completed two gender courses as part of their bachelor’s degree requirements, but they also attended a series of seminars and workshops on gender issues and produced policy papers to be considered for publication; all of this while being active ambassadors to raise awareness on issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion within their scholarly disciplines and communities. Wow!

Today, we at LAU are proud to say that we are graduating a new generation of changemakers: interdisciplinary leaders who are empowered and well-equipped to make the changes needed for a better tomorrow. It is the new generation of what I would call Inclusive Leaders!

This effort would not have been possible without the continuous support and trust of our partners at the United States Department of State and the U.S.-Middle East Partnership Initiative (MEPI), who never lost the faith in the youth of the region. Also, the precious support of many valuable LAU departments, staff, and organizations was essential to the success of the program, including LAU’s School of Arts and Sciences and its esteemed faculty and Writing Center, the Arab Institute for Women and the staff of Al-Raida, and LAU’s SDEM unit led by Vice President Elise Salem. Lastly, it goes without saying that we all owe a major debt of gratitude to the TLS administrative team. A message of gratitude goes out to our amazing and fearless team, led by Dr. Lina Kreidie, Dr. Jennifer Skulte-Ouaiss, and Ms. Tania Bou Arbid. Thank you for going above and beyond the call of duty for our amazing TLS students.

This publication is the culmination of the best work of the 2021–2022 cohort of TLS students. We are very proud to see their hard work come to life through this issue of Al-Raida. Congratulations to all.

al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023) 02 Editorial

Dina Abdul Rahman Executive Director, MEPI-Tomorrow’s Leaders Programs at the Lebanese American University

A Note to Our Students

Lina Kreidie

The Gender Agenda of Civil Society Organizations in Lebanon: Intervention Constraints and the Absence of Cooperation and Action

Rena Haidar

Listen to Women: Gender Bias in Clinical Pain Management

Tonia Chahine

The Influence of Quotas on Promoting Women in Decision Making Positions

Melissa Bou Zeid

Unpaid Care Work in Lebanon: A Barrier to Women’s Economic Empowerment

Maria Abi Akl

Reallocating Soft Power in Sports: From Political Agendas to Sustainable Peace and Development

Lynn al Jamal

Automation and Gender

Rita Mroue

Women in Financial Technology: A Lack of Participation in Blockchain

Shella Marcos El Douaihy

Queer Coding and Misrepresentation in Arab Media

Kassem Fattah

Social Media: A Curse or a Blessing?

Wafic Khalife

The Aftermath of Sexual Assault in Warfare: Analysis of UN Security Council Resolution 2467

Reina Al Sayegh

Inclusion of Women in Negotiations: The Syrian Women’s Advisory Board and the Yemeni Women’s Technical Advisory Group

Gheed Khiami

The Role of Palestinian Women in IsraelPalestine Peace Negotiations

Lyne Sammouri

al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023) 03

A Note to Our Students

Lina Kreidie MEPI-TLS Academic Director

You are published!!

You are today’s and tomorrow’s change makers.

Our dear second cohort of Tomorrows’ Leaders for gender equality. This a big leap towards gender equality in terms of advocacy and policy recommendations. We are so proud of you and your passion to meet all the challenges facing you, your community, and the world even as the road to equality and social justice is long and hard. Stand up strong for equity, equality, and all human rights.

Accomplishments and progress require the vast support of open-minded and courageous people and institutions. Our Tomorrow’s Leaders students have exactly that. Thanks to the Middle East Partnership Initiative at the United States Department of State for providing our students and our institution with the financial and ideological support to pursue the Lebanese American University’s (LAU) commitment to human rights and other liberal values. Thank you to the MEPI-TLS team, both in Lebanon and abroad, for your remarkable support for and implementation of this program. Without your dedication, our students would not have the tools that they need to pursue a bright and gender equitable future for us all.

Finally, to our students: Remember, prosperity happens only once social justice has been achieved. Fly high, stay connected, and keep us posted as you move forward beyond the borders of our LAU campus. We salute your work.

al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023) 04

The Gender Agenda of Civil Society Organizations in

Lebanon: Intervention Constraints and the

Absence of Cooperation and Action

Rena Haidar Political Science and International Affairs Major

Abstract

Lebanon’s vibrant civil society has shaped different aspects of the country’s political, economic, and social landscape. This paper aims to explore two main constraints obstructing the efficacy of local CSOs working on issues related to gender and women’s rights. The first constraint is the polarization between CSOs, and the second is the absence of networking and cooperation. The paper’s main recommendations for CSOs highlight the importance of strengthening cooperation between CSOs themselves, and between CSOs and the government. As for the state, the paper’s recommendations focus on how to create a bridge of cooperation with CSOs that are committed to action. Finally, the paper emphasizes that a strong, centralized agenda to gender and women’s rights can facilitate the coordination between and the efficacy of CSOs working to promote gender equality in Lebanon.

Introduction

Civil society organizations (CSOs) in Lebanon are a driving force in the fight against gender discrimination and inequality. Lebanon’s poor ranking on the Global Gender Gap Index—145 out of 153 countries—is reflected in the large number of CSOs in the country dedicated solely to issues of gender inequality and women’s rights. The critical influence of these local CSOs on gender inequality makes them critical actors in the field of gender equality; it is thus important to assess and evaluate their approaches to gender equality and the efficacy of these approaches.

al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023) 05

The latest data on the number of registered CSOs in Lebanon as of 2014 show that over 8,000 organizations currently operate in Lebanon: 62% of these CSOs operate at the national level, while the rest operate at the community level. Further, 40 % of beneficiaries of CSO programming are women (Beyond Reform and Developent [BRD], 2015). This huge number, which we can expect to have increased after the Beirut port explosion and the worsening economic crisis, highlights the importance of the work done by CSOs. Importantly, many of these organizations work specifically on issues of gender and women’s rights, including well-known organizations like ABAAD, KAFA, HELEM, SHIELD, MOSAIC, Seeds for Legal Initiatives, FE-MALE, Dar Al Amal, Arab Institute for Women, RDFL, CeSSRA, Haven for Artists, and many others.

The large number of organizations working on issues related to gender inequality and women’s rights means that there is a large spectrum along which CSOs define what counts as “gender equality,” and how organizations believe that this goal can be achieved. At one end of this spectrum is the achievement of full gender equality at all levels of society, including in politics. Some CSOs have chosen to fight for gender equality in certain sectors only, for example political rights, while others have chosen to focus on shifting societal attitudes toward gender as a way of eventually ensuring gender equality. The variegated approaches used by CSOs to attain gender equality, and the different understandings of what are the best strategies to achieve it, have made the actual goal of achieving full gender equality ultimately quite difficult. How can we achieve gender equality if CSOs and other actors do not actually agree on the best methods for achieving equality? What does this mean for the work of local CSOs in practice? These are the questions that are at the heart of this paper.

CSOs working on gender issues in Lebanon face various barriers. Despite their continuous efforts to thrive amidst the dreadful financial and political crises in Lebanon, their efforts to promote gender equality are driven backward by several constraints. The first constraint that this paper presents is the lack of a unified agenda driving the work of CSOs focused on gender inequality. The second constraint facing these CSOs is the absence of a constructive network of cooperation with formal government institutions which should be supporting this work. After discussing the implications of these constraints, the paper will present some recommendations for both CSOs and for government institutions to enhance their approach toward gender equality, gender mainstreaming, and women’s political and socio-economic empowerment.

Separate Agendas, Separate Ideas: The

Lack

of a Unified Strategy Among Gender CSOs

Cooperation, networking, and engagement in any field makes actions and results more structured and efficient. Similarly, if CSOs in Lebanon could set similar priorities in their work on women’s rights and gender equality, they could accelerate their goals and make results more sustainable and efficient. The fact that gender issues are “divided” into certain sub-focuses presents an important barrier to collective work and organizing. For example, the number of organizations focusing on the LGBTQ+ community is minimal compared to the ones working on women’s rights issues more broadly. Similarly, there are fewer organizations working on women’s political participation than there are organizations working on gender-based violence (GBV). Thus, it is important to ask what could happen if all CSOs in Lebanon shared the same

al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023) 06

vision and approach towards women’s and gender issues, and what gains could be achieved from this unity or solidarity.

The lack of cooperation between CSOs working on gender and women’s rights issues might also be tied to the lack of an organizing structure at the national level. Such an organization can help put actors in touch with each other and can give organizations more information about what they are working on (Lebanese Humanitarian and Development Forum [HDF], 2022). A report by the UNDP highlights that there is no directory for gender actors in Lebanon which facilitates access to their work, publications, announcements, and other important issues (UNDP & CRI, 2006). In addition, a mapping of 75 gender actors done by the Centre for Social Sciences Research and Action (CeSSRA) shows that 65 of these actors are in the capital Beirut, while the rest (10 actors) are spread over three other districts (CeSSRA, 2020). Their geographical concentration in Beirut compared to their relative lack across the rest of the country presents another limitation to the work of gender CSOs in Lebanon (CeSSRA, 2020).

A unified agenda for CSOs means that their programmatic interventions would not overlap or duplicate another CSO’s work. Knowing what the main priorities are in terms of gender equality and women’s empowerment eases the work of CSOs, directs their focus, and structures their approach. This unified agenda can take the form of a national strategy; a national strategy does exist in Lebanon but is not implemented. In fact, two national strategies exist, one focused on women’s rights and the other on GBV. The GBV national strategy plan was established by the Office of the Minister of State for Women’s Affairs (OMSWA), and it only tackles GBV (ABAAD, 2020). The OMSWA aimed to work closely with civil society actors to implement this national strategy plan, but its work has gradually diminished ever since its establishment (United Nations Population Fund [UNFPA], 2020).

A National Action Plan (NAP) on women, peace, and security was also created in Lebanon and endorsed by different stakeholders from government institutions to civil society, and others. This NAP was based on the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security (UN Women, 2019). The aim of this NAP was to create a structured plan to enhance women’s political and social participation, representation, and inclusion. Interestingly, this NAP was established with the help of only three CSOs, which is a very small number compared to the number of CSOs working on gender inequality in the country. The NAP also proposed only one suggestion on advancing networking and cooperation between civil society and the government. The NAP suggests that there should be a platform, or a portal enabling leaders in the civil society to communicate and partner with women parliamentarians (National Commission for Lebanese Women [NCLW], 2019). There are, however, a few important gaps in this proposal, including the limited political will to implement this strategy.

While these two national strategies are important, focusing on GBV or women’s social and political empowerment as separate issues are only piecemeal strategies for fighting gender inequality. Instead, CSOs should consider promoting a unified national plan that foregrounds several simultaneous and equally important goals as part of a holistic plan to fight against gender inequality.

al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023) 07

Another potential reason for the lack of a unified agenda among gender CSOs is related to financial donors. CSOs primarily operate through the funding they receive from international donors. The findings of an assessment done on the needs of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Lebanon highlights that donor funding does more than just provide cash: It also forms and structures the full governance of the organization, which includes the mission, vision, and basic guidelines or policies (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2009). Knowing that the financial resources of nearly all CSOs are from international donors, it can be deduced that the priorities and objectives of an organization rely heavily on what the donors want or ask from the recipients of their funds.

Networking and cooperation between CSOs could ultimately alter the quest for gender equality and gender mainstreaming. Setting out similar priorities between gender actors can make the process of achieving gender equality more sustainable and more effective. A solid example of this is the first ever feminist civil society platform created by civil society actors and activists in Lebanon after the Beirut port explosion in 2020 with the help of UN Women. The Feminist Civil Society Platform (LFSCP) includes 50 members, and its main aim is to consolidate the status of women in different sectors and fields. The platform succeeded in convening different signatories to bring up important concerns about the status of women to the forefront of civil society debates. The most recent demands by the members of this platform were about the underrepresentation of women in government institutions, notably as the general elections were approaching in Lebanon. A statement by the signatories also affirms that they will monitor and hold accountable any unequitable and unjust approaches toward women in the political realm (LFSCP, 2021). Again, it can be argued that once gender actors work collaboratively and unify their demands, their efforts may have a far-reaching impact on the government and on society more broadly. The feminist platform is a great pathway towards a more unified gender agenda; however, if its members will not integrate or revisit their own approaches to gender issues, the platform will become ineffective.

The Absence of Networking and Collaboration between CSOs and the Government

The long history of civil society actors in Lebanon makes them important stakeholders in relatively all aspects of the social, political, and economic arenas of the Lebanese state. Nonetheless, the Lebanese government seems to primarily depend on CSOs to achieve certain goals, rather than choosing to work with CSOs as collaborators. While networks and points of contact do exist between the government and CSOs, their existence is primarily rhetorical and often does not amount to concrete action or policy. Further, government funding of CSOs, particularly those working on gender, is lacking, which exacerbates any forms of cooperation and communication between the two stakeholders and increases dependency on international donors (AbouAssi, 2019).

In 1998, the National Commission for Lebanese Women (NCLW) was established and was endorsed by the Council of Ministers. This was the first ever official entity to represent the fight for women’s empowerment in the government, and it serves as the country’s official national women’s machinery (NCLW, 2022). The main objectives of this institution include creating equal opportunities for men and women to prosper in Lebanese society, and to mainstream gender in public institutions across Lebanon.

al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023) 8

NCLW mainly works with inter-governmental organizations and UN agencies and is not seen to have adequate networking with local CSOs. This makes it even harder for CSOs to build close relations with government institutions and it denies them the chance to interact and coordinate with other stakeholders. The role of NCLW is very critical for the work of CSOs on gender and women’s rights. Thus, fostering effective partnerships and coordination between the two stakeholders should be a primary focus for CSOs. In other words, a strong working relationship between NCLW and local gender CSOs is key to fighting for gender equality in a sustainable way.

Various laws still exist in Lebanon that block gender equality and women’s empowerment. Among these laws are the personal status laws, labor laws, the national social security law, the nationality law, and others. To challenge these laws, networking between CSOs and the government is needed. CSOs have done ample research, projects, and programs concerning these laws. However, due to the lack of constructive government connectivity and cooperation, the efforts of these CSOs often go unacknowledged by the government. For this reason, among others, stakeholders must work together and cooperate closely to improve the status of women, and to codify gender equality. A strong working relationship between gender CSOs and government actors can facilitate this work and can help to keep gender inequality on the agendas of various government actors.

Recommendations and Conclusion

The quest for gender equality and women’s rights in Lebanon begins at the local level. CSOs have been continuously working on providing women and gender minorities in Lebanon the opportunity to voice their concerns and to participate equitably in society. For this, assessing and evaluating the extent to which CSOs are properly working on gender issues requires rethinking their agendas and unifying them into one focused agenda. Furthermore, for the work of these CSOs to be legitimized and translated into policymaking, cooperation and networking with the government must be reinforced and nourished.

For CSOs to establish a more holistic and unified agenda which sets out their main priorities related to gender and women’s rights issues, this article suggests the following recommendations:

• Establishing a yearly forum for CSOs which only involves organizations that work on issues related to gender and/or women’s rights. The aim of this forum would be to articulate a unified agenda among these actors, which could be updated each year based on the different challenges and circumstances faced by these actors.

• CSOs must work closely on addressing the issue of their locations and who their beneficiaries are. Knowing that nearly all CSOs operate in specific districts and locations, and that this dictates the extent of their influence, CSOs must adopt a strategy that targets beneficiaries in their areas of operation and in districts where access to CSOs working on gender equality has been limited. They could open temporary offices, implement projects, and network with existing CSOs in those districts that may help them work toward gender equality.

• CSOs should lobby for the implementation of the NAP and provide evidence-based knowledge and reviews on its effectiveness and limitations on a yearly basis.

• CSOs must adopt new approaches with the donor community that limit their

al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023) 9

influence on how gender programs and projects should be implemented and who the beneficiaries of these programs should be, in order to ensure that local needs are met and responded to. This approach must be shared by all CSOs to prevent the duplication of work and program interventions.

For the government and its respective institutions, the below recommendations are presented concerning strengthening the ties between civil society and government actors on issues related to gender and women’s rights:

• Government financing of CSOs working on gender and/or women’s rights must increase. This can alter the dynamics of dependency on the international community for aid and could also create new forms of cooperation between the government and local actors.

• The government should modify the current NAP and add to it a new detailed section that deals with civil society cooperation.

• The NCLW should strengthen its ties with CSOs and should aim to collaborate more often with programs and projects that require full-scale engagement from all gender stakeholders or actors in Lebanon.

Civil society in Lebanon has been and remains a key player in the fields of human rights, gender equality, humanitarianism, refugees, education, development, health, and so much more. As a result, shedding light on the dynamics of CSOs in Lebanon is important to better understand how they contribute to enhancing gender norms and what their limitations are. This paper only addressed two of the limitations and challenges obstructing CSOs, but there remain other challenges that require exploration. While this paper relied on existing research and different observations made on the work of CSOs on gender equality and women’s rights in Lebanon, future research should include primary data collection, which requires interviewing CSO employees and exploring their relationship with other local actors on this specific subject matter.

The elimination of gender gaps in Lebanon requires the full cooperation of all stakeholders, specifically government actors and civil society groups. CSOs on their own cannot alter the status quo and change discourses on gender. The limitations and challenges that CSOs face on a legal and institutional level are impeding their progress and making it almost impossible to achieve their goal of gender equality in Lebanon. Building a unified agenda and strengthening collaboration between CSOs and government actors are two key strategies for advancing the fight against gender inequality in Lebanon.

10 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

references

ABAAD. (2020). Mapping gender-based violence programmes, services, and policies in Lebanon. https:// www.abaadmena.org/documents/ebook.1626097663.pdf

AbouAssi, K. (2019). The third wheel in public policy: An overview of NGOs in Lebanon. In A.R. Darwood (Ed.), Public administration and policy in the Middle East (pp. 215-230). Springer Science+Business Media. http://www.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-1553-8_12

Beyond Reform and Development. (2015). Mapping civil society organizations in Lebanon. https:// eeas.europa.eu/archives/delegations/lebanon/documents/news/20150416_2_en.pdf

Centre for Social Sciences Research and Action. (2020). Gender actors map. https://civilsocietycentre.org/map/gen/gender-actor

Lebanon’s Feminist Civil Society Platform. (2021). Lebanon’s Feminist Civil Society Platform calls for ensuring a fair and equitable space for women in the political sphere. https://arabstates. unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Field%20Office%20Arab%20States/Attachments/ Publications/2021/09/Lebanon%20Charter/LFCSP_STATEMENT_ENGLISH-2.pdf

Lebanon Humanitarian and Development Forum. (2022). Representation. https://www.lhdf-lb.org/ en/representation

National Commission For Lebanese Women. (2019). Lebanon National Action Plan on United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325. https://nclw.gov.lb/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/ Lebanon-NAP-1325-UNSCR-WPS-Summary.pdf

National Commission for Lebanese Women. (2022). Mission and vison. https://nclw.gov.lb/en/ mission-and-vision-2/

UN Women. (2019). Understanding the role of women and feminist actors in Lebanon’s 2019 protests. https://arabstates.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2019/12/gendering-lebanons2019-protests

UNDP. (2009). Assessment of capacity building needs of NGOs in Lebanon. http://www.undp.org.lb/ communication/publications/downloads/Capacity%20Building%20Needs%20 Assessmentfor%20NGOs.pdf

UNDP, & Consultation & Research Institute. (2006). Mapping of gender and development initiatives in Lebanon. http://www.undp.org.lb/WhatWeDo/Docs/Lebanon_Gender_Strategy.pdf

UNFPA. (2020). Lebanon: Review of health, justice and police, and social essential services for women and girls survivors of violence in the Arab States. https://arabstates.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/ pub-pdf/lebanon_3-12-2020_signed_off_1.pdf

11 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

Listen to Women: Gender Bias in Clinical Pain Management

Tonia Chahine Biology Major

Abstract

Research demonstrates that cultural barriers obstruct fair pain management between men and women. The nature of the healthcare gender bias has deleterious effects on women’s overall wellbeing. Erroneous perceptions of women as being “histrionic” or having “temper tantrums” have a long history in the medical field. Consequently, physical pain in women has been often mismanaged, with most of it being attributed to women being “overly emotional.” Women pay the price: When their pain is constructed as theatrical, they risk being misdiagnosed which results in inadequate healthcare treatment. The aim of this paper is to explore gender bias in pain management, and to track the different cultural hubs out of which such misconceptions emanate.

Introduction

The Problem

Medicine is said to be a talent: the talent of resolving the complexities of the human body. Therefore, patients expect their providers to be interested in their concerns and to take care of their pain as it is supposedly a physician’s lifelong mission. Similarly, patients expect their providers’ evaluation of the pain they are experiencing to be unbiased. Chronic pain is a symptom that can affect anyone: It is not restricted to certain races, religious communities, or certain genders (Samulowitz et al., 2018). Unfortunately, despite their similar experiences of chronic pain, men and women do not receive similar medical care and attention. However, women are entitled to adequate healthcare treatment free from gender bias: As Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) outlines, “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care.” This paper analyzes the discrepancy

12 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

between pain management strategies of male and female patients and argues that women’s pain is being overlooked in clinical settings. This issue will be theorized using an intersectional analysis that approaches the topic through the lenses of history, current events, and other key perspectives, such as psychology.

What is Healthcare Bias?

Healthcare bias refers to the ways that sociocultural norms and expectations, including those surrounding gender, are embedded within the healthcare sector. These biases affect societal approaches to medical care. Healthcare gender bias is implicit, which means that it stems from external pressures that people unknowingly acquire during and assimilate into their own lives. In other words, healthcare bias is the byproduct of the cumulative effects of traditional norms and cultural practices surrounding gender. Unfortunately, this societal “training” that physicians receive throughout their lives negates efforts in their formal educational training that attempt to teach them to approach their work through an objective lens. In other words, while physicians are trained to be objective in their work, they will always project their subjective biases. Many of these biases revolve around normative and stereotypical understandings of how men and women should behave and the ways that they deal with pain.

Briefly put, gender bias in healthcare reinforces the idea that women’s reasoning capacities are limited and therefore, their pain perception is exaggerated and hysterical. This stereotypical mindset prevents many women from securing the medical services they need and deserve, including an accurate and timely diagnosis, as well as receiving effective treatment. Gender bias also endangers men’s health. In most cultures, the emphasis on masculinity and “strong” men has led to a resistance on the part of some men to seek medical help, as this is sometimes seen as a sign of weakness. The problem of gender bias in healthcare has additional consequences. For example, this bias promotes a lack of interest in researching the female body and the various symptoms and disorders that women may experience. This lack of knowledge can lead to distorted perceptions, which can result in inaccurate diagnoses and treatment recommendations. It is clear that the consequences of gender healthcare bias can be much more severe than people might think.

Historical Background

Gender bias in healthcare has a long history. Widespread social stereotypes about how women perceive, express, and tolerate pain are not recent. These stereotypes about gender roles date back as far as ancient Greece, as Cleghorn (2021) points out, and women are still paying the price today. Women’s pain was and still is frequently linked to emotional or psychological issues rather than physical ones. In fact, hysteria, which has its roots in ancient Egyptian and Greek medicine, became popular in the 18th and 19th centuries as a way to describe any female sexual or emotional conduct that males regarded as dramatic, insane, or unfeminine (Raypole, 2022). Hysterical complaints were a prominent reason for women’s forced hospitalization long into the 20th century. It was not until 1980 that the diagnosis of “hysteria” was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (Tasca et al., 2012). The historical duration of this example of gender bias points to the overall seriousness of bias in healthcare. The longer such practices continue, the more rigid and impactful they become, further distorting women’s diagnosis and treatment.

13 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

Cultural Discourse and Illness Narratives

Women have been wearisomely accused of being too “hormonal,” too sensitive, and too dramatic. Khakpour (2018) explains her journey with Lyme disease in her book Sick: A Memoir. She discusses how her symptoms were dismissed by her doctors as a psychiatric issue, which delayed her diagnosis and her access to treatment. Khakpour writes that, “in the end, every Lyme patient has some psychiatric diagnosis, too, if anything because of the hell it takes getting to a diagnosis” (p. 130). While some cultures portray women as dramatic patients who exaggerate their medical pain, others envision women as having a “high tolerance” to pain. An important example of this type of normative cultural discourse that contributes to gender healthcare bias among physicians is related to childbirth. Many people believe that since women are able to give birth, a process that can be exceptionally painful, other types of pain that they might experience are somehow minor and incomparable. Not only is this a dangerous bias, but it defines all women according to their ability to reproduce, which is something that not all women choose to do during their lifetime.

Literature Review

In general, the literature shows that there is a discernible existence of gender healthcare bias against women in particular. Much of the literature on gender healthcare bias underscores the extent that implicit gender bias prevents women from receiving adequate medical support and treatment. Most studies emphasize the idea that women are not receiving the attention, credit, and respect they deserve from their doctors, while others point to the fact that most clinicians unconsciously regard their female patients as unduly emotional or as exaggerating their discomfort. The following literature review presents a brief overview of some of the most important research findings about gender healthcare bias.

His Diagnosis Drives Her Insane, Literally

Previous work highlights that women with chronic pain are frequently mistrusted and psychologized by their healthcare providers. In their study, Samulowitz et al. (2018) found that a medical provider’s prescribed treatment was influenced by the similarity or difference between their own sex and that of their patient. They go on to suggest that women received less effective pain relief, as well as more antidepressant and mental health referrals, than men. Alspach (2012) suggests that prejudice related to a patient’s gender does exist in healthcare, especially among older male physicians, which explains some of the disparities in patient management. These disparities include taking women’s symptoms less seriously and attributing them to emotional rather than physical causes and referring women less often than men for specialty care, even women with higher risk factors. This is in line with a recent study by Greenwood et al. (2018) on women’s mortality rates, which argues that “most physicians are male, and male physicians appear to have trouble treating female patients” (p. 5).

Only Gender?

Raine (2000), on the other hand, argues that disparities in healthcare outcomes are not always attributable to gender healthcare bias. Raine notes that such disparities are also related to important variables such as differences in disease prevalence and severity, as well as patient preferences. While this may be true, Samulowitz et al. (2018) affirm that disparities in men’s and women’s care cannot be attributed to distinct medical needs. In

al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023) 14

their systematic review, FitzGerald and Hurst (2017) found that implicit bias based on patient characteristics does affect healthcare professionals. The review, however, makes no mention of any specific bias or patient characteristics, which might include race, gender, socioeconomic status, or something else. More studies are needed to accurately determine the types of bias that influence healthcare professionals.

Fortunately, however, some of the literature on gender bias in healthcare does point to potential solutions. Raypole (2022), for example, argues that it will take a large-scale shift in medical research methods as well as the systems that reinforce prejudice to affect such a change. This will be a difficult task. Relatedly, virtue epistemology—an approach to medicine wherein the medical doctor is just concerned with finding the truth, and only the truth, without having to consider other variables or be driven by their emotions and prejudices—could be used to combat healthcare gender bias in clinical decision-making (Marcum, 2017).

Analysis Manifestations of the Problem

Is it possible that some women are exaggerating their pain, forcing medical professionals to downplay their symptoms? Maybe. However, this cannot be generalized, especially because of engrained gender norms and stereotypes as discussed earlier. Therefore, it is important to explore the problem from the perspective of the clinician and to analyze how the physician’s own gender identity influences their appraisal of female pain. For example, a female physician may be more understanding, as well as experienced with and receptive to women’s pain, particularly menstrual pain. This is not to say that compassionate male doctors are not available. Nonetheless, one can never completely understand what another person is going through unless they put themselves in their shoes. It is worth noting, however, that despite being female, doctors may still retain prejudices towards other women. The findings from this literature review reveal that there is no individual standpoint from which the problem can be addressed, assessed, and eliminated. Rather, the problem of gender bias must be acknowledged at the structural or macro level.

On a psychological scale, when a doctor minimizes women’s worries or pain, they unconsciously infantilize them, insisting that they know more about their bodies than they do themselves. This is often very frustrating for patients. Patients who are regularly exposed to this type of treatment and dismissal may lose trust in healthcare professionals and forego regular health screenings. This can result in late diagnosis, which can be fatal in some cases. According to a shocking new survey, a third of Australian women may have postponed getting medical care because they are afraid of appearing melodramatic or tiresome. Rapana (2018) observed that about 40% of women fear being labeled “drama queens” or hypochondriacs if they speak up when something does not seem right. Additionally, a poll conducted by Pink Hope, a preventative health resource for breast and ovarian cancers, indicates that one in three women really shunned medical guidance for this reason (Rapana, 2018).

Proposed Policies and Solutions

One might assume that there are almost no viable solutions for an issue arising from culturally entrenched gender biases, or that the solutions will take too long to implement

15 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

or that they will be ineffective in the short-term. These beliefs must not prevent policymakers and other stakeholders from working to limit the manifestations of gender bias in healthcare by raising awareness about the issue among clinicians and other healthcare providers. Medical training should confront the reality of gender bias and provide professionals with the needed skills to avoid making healthcare decisions based on stereotypes and gender-biased beliefs. If they are sensitized to gender bias, clinicians can learn to listen to women’s symptoms and reconsider any diagnosis or therapy that is not working for them. Incorporating university courses or seminars on the psychology of women’s pain and on gender more broadly into the medical school curricula, for example, is an important starting point for addressing gender bias in healthcare.

Moreover, increasing the number of female healthcare practitioners should be a component of any strategy hoping to challenge healthcare gender bias. This is because, as described in earlier sections of this paper, female medical professionals can have additional insights into the symptoms of their female patients based on their own personal experiences. If more female students are empowered to join the healthcare industry, they may become part of the solution.

There are numerous other policies that could help combat healthcare gender bias. For example, it is vital to create healthcare facilities and centers that are entirely femalefocused, with only females having access to them. These centers would not only focus on treating women, but they would also focus on collecting data about female health issues. Such research is important for addressing the lack of knowledge about women’s various health problems and the overall lack of interest in female health issues. Various stakeholders should be involved in creating and financially supporting these research and clinical centers including governments and international donors.

The effort to improve healthcare treatment relies not only on the efforts of providers and others, but also on the attempts of women themselves and healthcare advocates to reshape public attitudes towards bout women’s bodies and healthcare. This is particularly important concerning the ways that mental health impacts the body, given that mental healthcare is stigmatized and, worse, is often treated separately from physical health and wellbeing. Chronic stress, for example, can cause stomach cramps and painful headaches, and vice versa. As a result, knowing how to approach these issues as interrelated is key. In other words, advocacy efforts must be accompanied by awareness-raising campaigns so that women are aware of gender bias, how to challenge it, and what to do when they need medical care. Women must be masters of their own bodies.

Conclusion

Gender healthcare bias against women exists, particularly in cultures where women are viewed as second-class citizens, weak, overly sensitive, and histrionic. Although the solutions are long-term and difficult, this does not invalidate their usefulness; they are meant to raise awareness about the problem and inform people that it happens. Gender bias in healthcare actively harms millions of women who put their faith in their healthcare professionals to help them. A woman must always remember that she is the expert of her own body. Some doctors may dismiss her symptoms, but it does not rule out the possibility that they are real. When it comes to their health, women should

al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023) 16

be persistent and forthright until their doctors are willing to listen. While there are many healthcare professionals struggling to correct gender bias in the field every day, it is important to continue raising awareness about the issue so that women can have access to substantive and equitable health care.

references

Alspach, J. G. (2012). Is there gender bias in critical care? Critical Care Nurse, 32(6), 8–14. https://doi. org/10.4037/ccn2012727

Cleghorn, E. (2021). Medical myths about gender roles go back to ancient Greece. Women are still paying the price today. Time. https://time.com/6074224/gender-medicine-history/ FitzGerald, C., & Hurst, S. (2017). Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BMC Medical Ethics, 18, 1–18. https://bmcmedethics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12910-0170179-8

Greenwood, B. N., Carnahan, S., & Huang, L. (2018). Patient–physician gender concordance and increased mortality among female heart attack patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(34), 8569–8574. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1800097115

Khakpour, P. (2018). Sick: A memoir. Harper Perennial.

Marcum, J.A. (2017). Clinical decision-making, gender bias, virtue epistemology, and quality healthcare. Topoi, 36, 501–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-015-9343-2

Raine, R. (2000). Does gender bias exist in the use of specialist health care? Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 5(4), 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/135581960000500409

Rapana, J. (2018). 1 in 3 Aussie women suffer from “drama queen syndrome.” Body and Soul. https:// www.bodyandsoul.com.au/health/womens-health/1-in-3-aussie-women-suffer-from-dramaqueen-syndrome/news-story/5d670e883465b521376d60ca69fb9803

Raypole, C. (2022, January 19). Gender bias in healthcare is very real—and sometimes fatal. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/gender-bias-healthcare

Samulowitz, A., Gremyr, I., Eriksson, E., & Hensing, G. (2018). “Brave men” and “emotional women”: A theory-guided literature review on gender bias in health care and gendered norms towards patients with chronic pain. Pain Research & Management, 2018, 1–14. https://doi. org/10.1155/2018/6358624

Tasca, C., Rapetti, M., Carta, M.G., & Fadda, B. (2012). Women and hysteria in the history of mental health. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 8, 110–119. https://doi. org/10.2174/1745017901208010110

17 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

The Influence of Quotas on Promoting Women in Decision Making Positions

Melissa Bou Zeid Pharmacy Major

Abstract

Gender discrimination is keeping women from participating in politics on equal footing with men. To modify this, several countries and stakeholders have implemented gender quotas to promote women’s representation in political institutions. However, time has proven that quotas are double-edged weapons with both negative and positive effects. This paper seeks to analyze the pitfalls of gender quotas and will introduce potential solutions that can increase the productivity of quotas.

Introduction

Angela Merkel, one of the most authoritative female leaders in the world, has proven that women can manage decision-making positions. Her foreign policies, and her economic and energy reform propositions have helped her to reach the top of Forbes’ list eight times (Conolly, 2015). And yet, it is apparent that women are still underestimated when it comes to their political competencies. The underrepresentation of women in politics is a global problem. In fact, only 7.8% of the CEOs of the largest companies and corporations in Europe are women, while only 31 women held executive roles across these organizations (Catalyst, 2022). As a result, governments, boards, and administrations are dominated by men. While gender-related associations, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and other stakeholders have worked toward breaking the existing glass ceiling for women in leadership roles and in politics, they have mainly focused on implementing quotas, which can be controversial, hard to implement, and in some cases, have mixed results. In general, gender quotas exist in three major forms. The first one is known as a “reserved seat quota,” which allocates a specific number of places for women in parliaments. The second type is a “legislative quota,” which mandates that a set number of a political party’s nominees are women. The third and final type of quota is known as a “voluntary party quota,” where parties themselves are responsible for ensuring that women are equally represented among their candidates (Bush, 2011). While some argue that quotas are vital for preserving spots for women in parliaments and in politics more broadly, opponents claim that they are unmeritocratic and inefficient (Robbins & Thomas, 2018). These disagreements

18 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

over the worth of gender quota systems highlight the need for further investigation and research. Accordingly, this policy paper will investigate some of the reasons why quotas might be ineffective. The paper draws on a rigorous literature review and current evidence from gender quotas around the world. The paper concludes with a discussion about how to navigate the disagreements over the effectiveness of gender quotas and offers several recommendations.

Why Gender Quotas Might Not Work as Well as We Hope

Traditional critiques of gender quota systems revolve around two primary issues, first, that quota systems are unmeritocratic, and second, that they “work against” the ideological basis of electoral democracy—in other words, that people are “forced” to vote for these candidates, and political parties are “forced” to select women candidates. The critique that gender quota systems are unmeritocratic is problematic for several reasons. First, the criteria used to define “merit” are uncertain and overgeneralized (Murray, 2015). Further, a “neutral” list of objective qualities that a desired candidate should have does not exist. Rather, the definition of merit changes depending on voter communities and preferences. Finally, the implementation of a quota system is not shown to affect the merit of those who get elected, as many leaders with low educational or skill levels, those who are corrupt, and those who have cheated the system for any number of reasons are frequently still able to enter politics irrespective of whether a gender quota system exists.

Additionally, rivals of gender quotas sometimes base their arguments on inaccurate historical and political perspectives. For example, quotas, especially in Europe, receive great opposition and antagonism because political leaders claim that this policy was adopted by the Soviets, even though this myth has long been disproven by research on the subject (Dahlerup, 2004). Another argument used to contradict the usage of quotas is that they may violate the historical norms and values of a country. Yet, such an argument is not convincing. For example, there are millions of acts that are performed daily that go against the norms and values of society. Further, these norms and values change, and have changed historically. In this case, the implementation of a gender quota system might be a change for the better.

More serious concerns about the efficacy of gender quotas revolve around traditional political culture, and how newly elected women leaders would fare in this environment. For example, some critics claims that gender quotas might further stigmatize women because those already in positions of political power would feel that women were “forcibly” placed into politics in a way that challenges the status quo. This would only exacerbate current forms of gender stereotyping and discrimination, as women are already underestimated and undervalued in the political arena. For instance, a woman who was placed on an industry’s board only for publicity and because of a quota might be viewed unprofessionally and therefore further marginalized, which could lead to damaging psychological outcomes (He & Kaplan, 2017). They will also suffer from the negative treatment she receives from her male coworkers, who believe that they were “forced” to cooperate with her because of their company’s publicity stunt. Further, psychology suggests that even though male workers might believe in the gender equality agenda, they might be demotivated to collaborate with women when it is imposed on them (He & Kaplan, 2017). Something similar might

19 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

occur to women members of parliament elected because of a quota system. Relatedly, quotas affect the workplace’s general stability. This is because organizations must accommodate to new rules and regulations that might not be welcomed by everybody. From a psychological perspective, this generates internal conflicts, for what is seen as a gain for some (women) is perceived as a loss for many others (men).

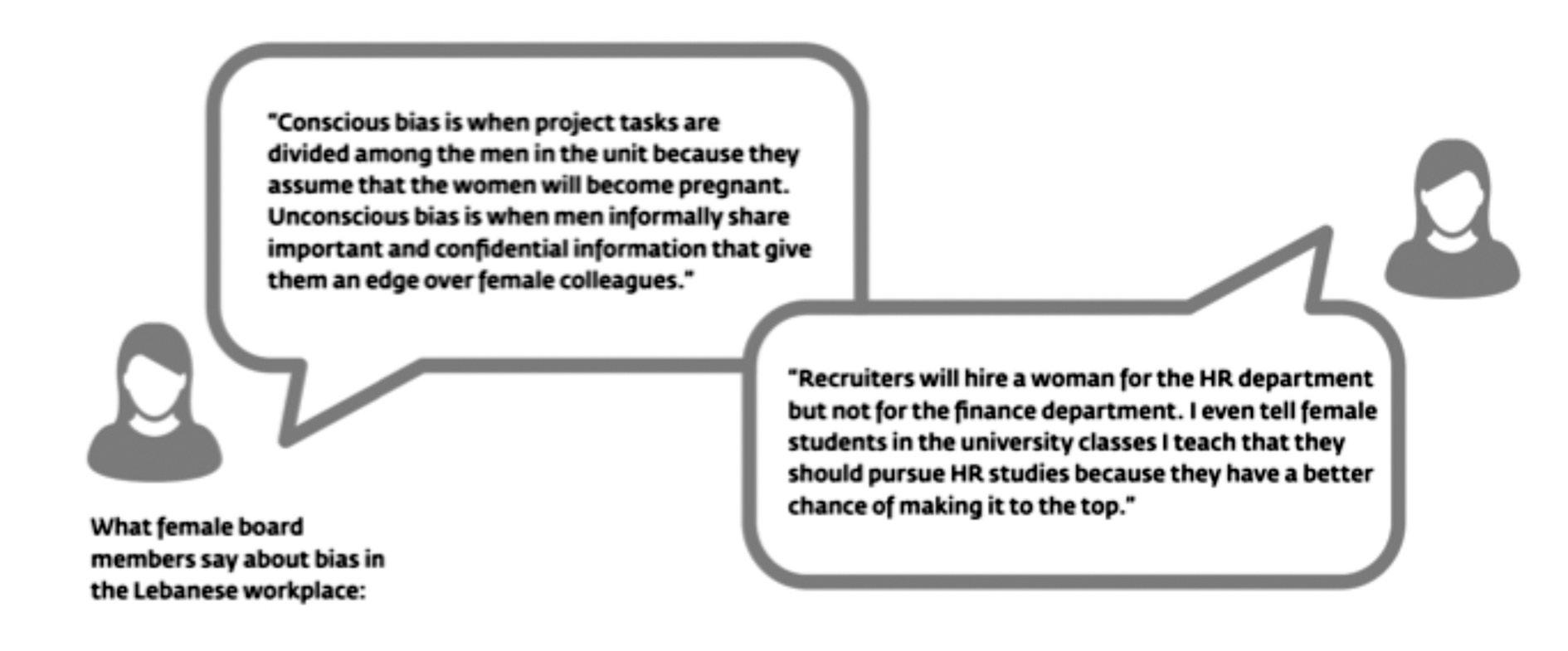

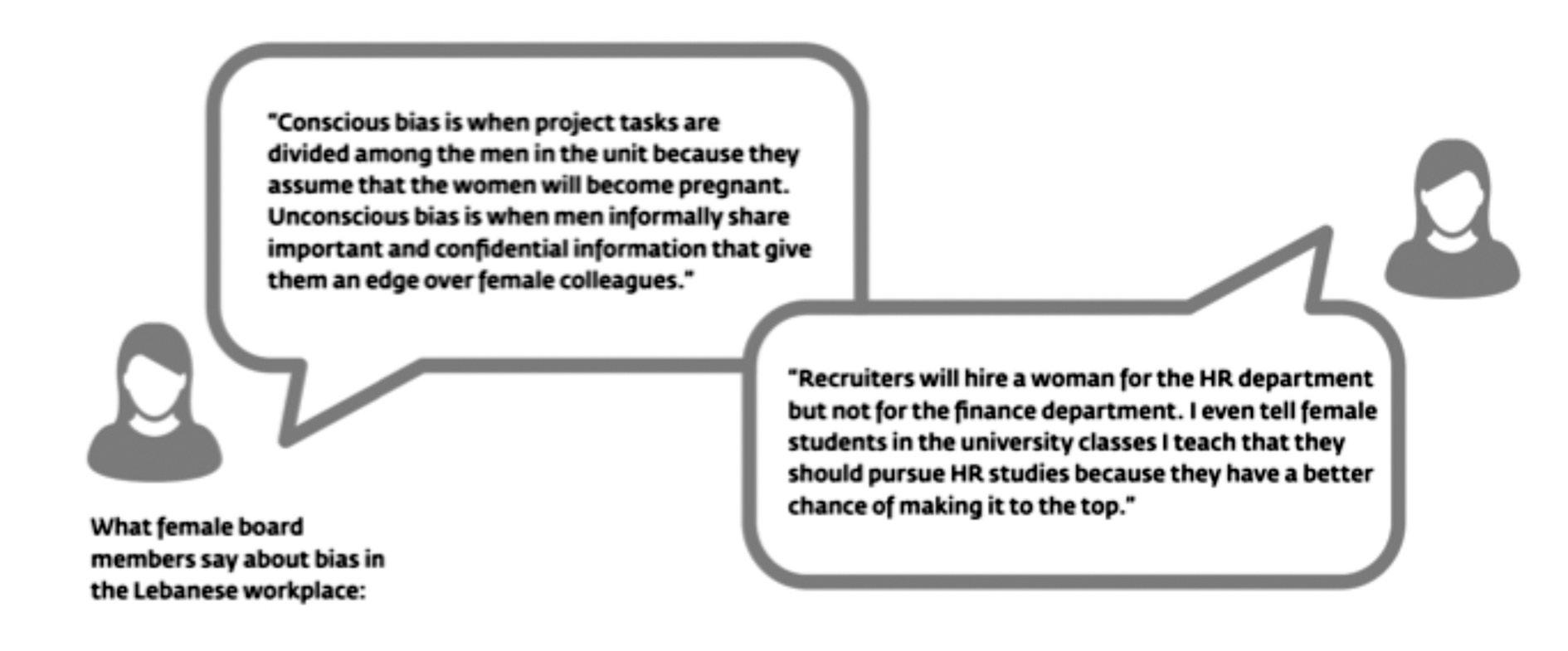

Note. Image taken from International Finance Corporation [IFC], 2019.

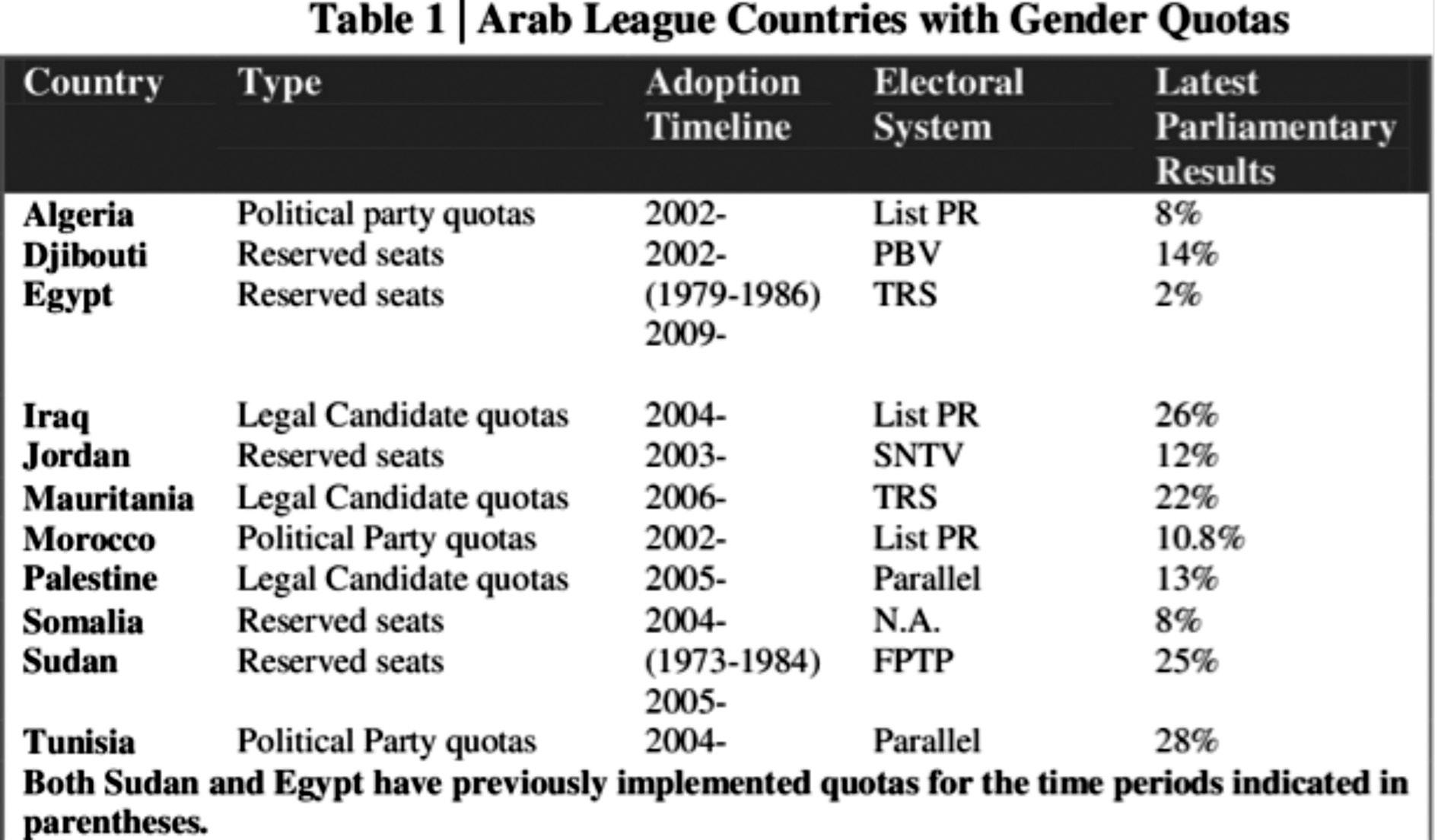

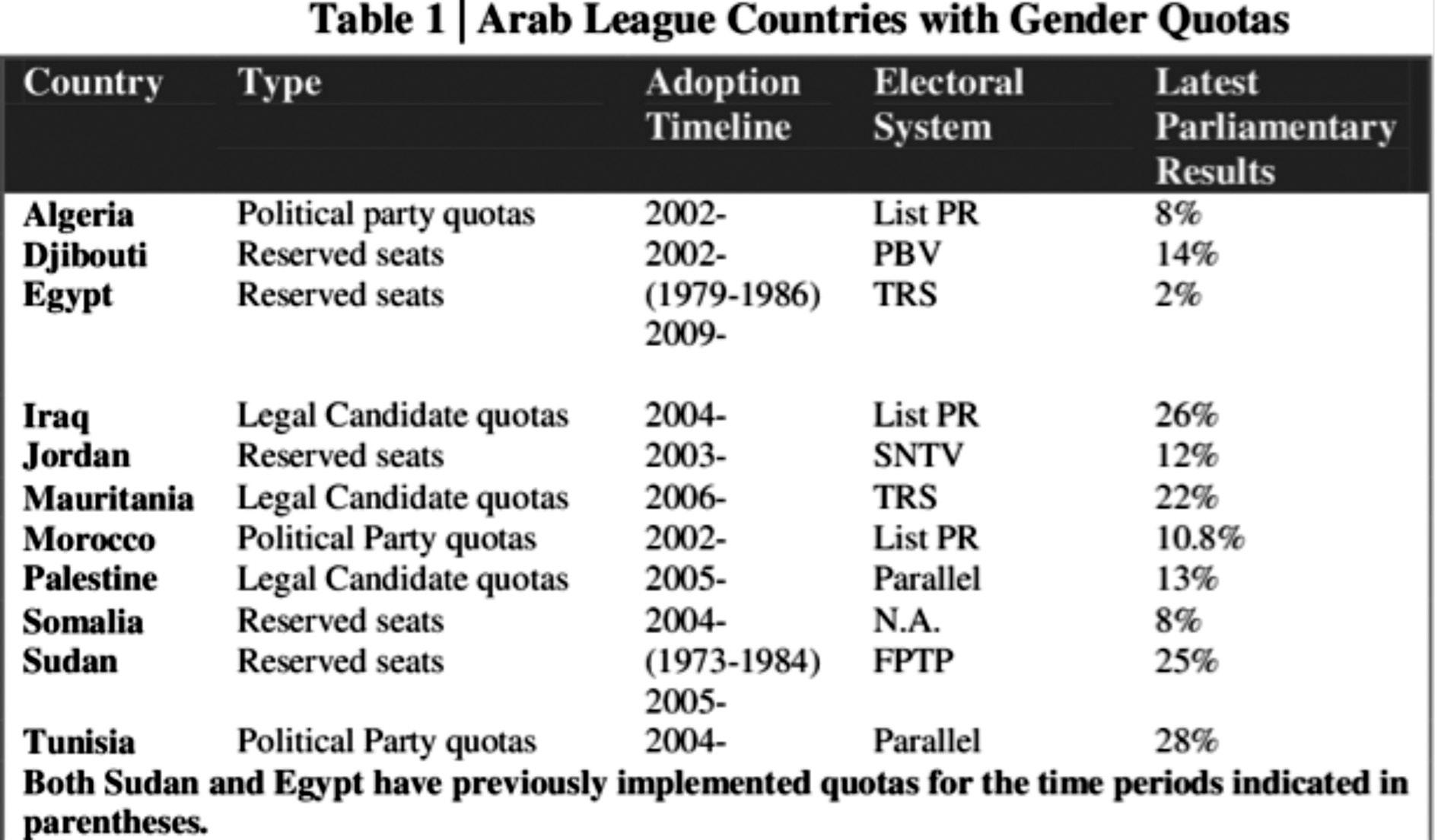

Moreover, according to a study conducted by Gender and the Economy (He & Kaplan, 2017), only 5% of the 500 prominent CEOs of 2016 were women, despite the introduction of quotas. Based on these numbers, it is estimated that at least 30 years are needed for women’s representation to reach 30% (He & Kaplan, 2017). A few important examples of this slow upward growth can be found in countries that have adopted a gender quota system. For example, the implementation of gender quotas at the municipal level in Spain were shown only to increase the number of women on political party lists. Meanwhile, the number of women that were eventually elected to the position of mayor or into other political positions with decision-making power did not increase. In fact, prior to the introduction of quotas, the percentage of female mayors was equal to 13% in 2003. Twelve years later, this number increased by 6% among the municipalities irrespective of whether the municipality had mandated gender quotas (Bagues & Campa, 2017). Additionally, “reserved seat quotas” implemented in the Arab region (see Figure 2, below) often reserve a minimal number of seats for women candidates, tempering the effects of such gender quotas even further (Welborne, 2010).

20 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

Figure 1

The challenges faced by women in boards and industries, even after the implementation of different gender quotas

Exploring Alternative Strategies Strategy 1: Secularization

Even though quotas seem unsuccessful in promoting women in decision-making positions, several initiatives can be mobilized to increase the effectiveness of quotas, whether major or minor. One solution proposed to render the employment of quotas more efficient is to promote secularization in countries where religion and politics are closely intertwined (Dahlerup, 2004). This is because the pre-existing norms and traditions embedded within various religious communities might reinforce gender roles and stereotypes, leaving women in a disadvantaged position. This is particularly true in the case of Lebanon, where men are seen as leaders while women are restricted to their gendered roles as “caregivers” and face many barriers that prevent them from entering the political sphere. Implementing a quota system will not sufficiently address this system and the gender discrimination it enforces. Relatedly, imposing such a major change would not be appreciated or understood by many, which could lead to conflict. Instead, promoting secularization can help to better secure gender equality at the core of society, which can lead to better women’s political representation over the longterm.

Strategy 2: Targeting Unconscious Bias

Another suggested strategy to increase the efficacy of quota implementation is the targeting of unconscious biases that contribute to gender inequality (Mishra, 2018). For instance, the prevailing theories that women cannot hold serious leadership positions because of family duties, their responsibilities as wives, or their responsibilities as mothers can and must be amended. To a certain extent, such a solution might succeed in eradicating the negative outcomes of quota application in both the short- and long-

21 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

Figure 2

Table depicting the inconsiderable representation of Arab women in the political sectors even after the employment of numerous quotas

Note. Image taken from Welborne, 2010.

term. However, the work of undoing unconscious bias takes years of hard work and effort, making this solution time-consuming even though it is necessary in the fight to get rid of gender inequality (Kuschmider, 2021).

Strategy 3: Defining Merit-based Criteria

Another strategy includes redefining the credentials, requirements, and qualifications of leadership roles before employing quotas as a way of challenging the idea that quotas are unmeritocratic systems that unfairly promote women (Mishra, 2018). However, finding common denominators between males and females in terms of leadership qualifications and requirements that can satisfy an entire voting community is not plausible. Furthermore, having male and female leaders with identical capabilities would effectively work to keep various other communities out of political leadership. For example, people without access to higher education, poor people, and people who do not have specific credentials will all be kept out of politics, which challenges the core goal of democracy, which is to represent a diverse voter body. In other words, diverse voting communities would not be well-represented with such a list of qualifications and requirements for entering politics. For example, forcing the Lebanese parliament to include the same number of men and women, all with similar educational and cognitive qualifications and experiences, would be disadvantageous. While their similarities might facilitate their ability to work together to address political problems, they might also disregard problems that do not directly affect them. For example, as privileged politicians, they might not feel an urgency to advocate for strong anti-poverty laws even if many of their constituents are in need of such policies. Thus, the decisions of a board or a parliament composed of leaders with identical backgrounds would be controlled by unconscious biases. Therefore, it

22 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

Figure 3

The Different Forms of Unconscious Bias

Note. Image taken from Suarez, 2019.

can be safely concluded that pinpointing the criteria for meritocracy is a double-edged solution, which can have both positive and negative results.

Strategy 4: Strengthening Women’s Rights in Everyday Life

A final strategy to increase the effectiveness of quotas is related to the status of women more broadly. If women are not financially, socially, and educationally ready, the implementation of quotas will not work. Accordingly, to stimulate women’s participation in the public sphere in general, and in decision-making positions and politics in particular, stronger welfare systems must be developed. Welfare systems can help to ensure the education, training, and employment of women, while orienting them towards being socially and financially independent. As a result, women would be empowered and might more readily exercise their rights to participate in politics and beyond. Moreover, welfare systems assist in housing and childcare, especially in low-income areas. Therefore, what might be a burden on some women and a cause for their lack of participation in multiple fields, such as childcare and family care, will be diminished. According to Orloff (1996), welfare systems applied in 20 different industrialized countries supported the presence of women in economic and political sectors. Therefore, welfare systems can significantly and positively impact quota systems because they support the social rights of women and encourage them to participate in politics and the public sphere.

Recommended Solutions to Render Quotas more Effectual

To increase the efficacy of gender quotas, various policies, initiatives, and strategies can be used. First, gender activists and professionals can provide mentorship programs and sessions that teach political leaders about the advantages and disadvantages of quotas. Then, those responsible would get the chance to further understand when and how they should rely on gender quota systems. This way, officials can learn how to properly track the implementation of gender quotas and can simultaneously implement other policies that can help strengthen women’s empowerment in the political sphere.

Additionally, quotas should undergo trial phases and should continuously be studied. For instance, gender quota systems can be implemented in municipal governments and then, based on whether this trial was successful, be subsequently implemented at the national level. For instance, the Spanish electoral quota was first applied on a minor group of participants and was then extended to a larger group (Bagues & Campa, 2017). Thus, quotas can be studied and tried before their use at the national level. This can reduce the potential drawbacks of a gender quota, which can consequently give officials the chance to prevent these problems.

Relatedly, another solution could be the creation of small committees responsible for the development and oversight of gender quotas. For example, if the quota involves the health industry, a committee formed of doctors, pharmacists, and nurses should be the one to decide how it should be applied. Thus, the suggested quota would be tailored to fit the specific context in which it is implemented. Subsequently, this specialization would increase quota efficiency, decrease its unfavorable missteps, and promote equality and equity.

23 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

Conclusion

Although the aforementioned policies are capable of rendering quotas more efficient, their viability in countries such as Lebanon is still questionable. Real-life examples prove that quotas are inefficient and that women are still relying on “balancing acts” to step over societies’ gender stereotypes to access leadership roles and, once they secure these roles, to flourish therein (Zheng et al., 2018). In Lebanon, women’s rights and feminist advocates have long argued for the use of a gender quota system to guarantee women’s equal representation in parliament. Most recently, ahead of the 2022 parliamentary elections, a proposal was drafted that would reserve 26 seats for women out of the 128, 13 for Muslims and 13 for Christians (Tabbara, 2021). However, the proposal was rejected by parliament, resulting in only 15% women candidates (out of 1,043 registered candidates), and a total of eight women elected to parliament (Houssari, 2022). It is important, therefore, to keep pushing for a gender quota system in the short-term while simultaneously working to implement some of the strategies suggested in the previous sections to remove gender inequality and discrimination that prevents women from entering politics to begin with.

All in all, conflicts related to gender equity, equality, and discrimination are still apparent. On the one hand, gender quotas, which have been implemented since the early 20th century, have positively influenced women’s involvement across different sectors to varying degrees. Yet, their drawbacks suggest that quotas necessitate amendments to render them more effective and beneficial. Thus, the importance of these other policies cannot be understated, as women’s underrepresentation in politics is a major issue plaguing women around the world.

references

Bagues, M., & Campa, P. (2017, September 9). Electoral gender quotas fail to empower women. VOX, CEPR Policy Portal. https://voxeu.org/article/electoral-gender-quotas-fail-empower-women Bush, S.S. (2011). International politics and the spread of quotas for women in legislatures. International Organization, 65(1), 103–137. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020818310000287

Catalyst. (2022, March 1). Women in management (quick take). https://www.catalyst.org/research/ women-in-management/

Conolly, K. (2015, January 7). Ten reasons Angela Merkel is the world’s most powerful woman. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/07/ten-reasons-angela-merkel-germanychancellor-world-most-powerful-woman

24 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

Figure 4

The Advantages of Specialized Quota Committees

Note. Image prepared by author.

Dahlerup, D. (2004, October 22). “No quota fever in Europe?” [Conference paper]. International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA)/CEE Network for Gender Issues Conference, Budapest, Hungary. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242554715_No_ Quota_Fever_in_Europe

He, J., & Kaplan, S. (2017, October 26). The debate about quotas. Gender and the Economy. https:// www.gendereconomy.org/the-debate-about-quotas/ Houssari, N. (2022, March 16). Over 1,000 candidates register for Lebanese elections. Arab News. https:// www.arabnews.com/node/2043931/middle-east International Finance Corporation. (2019). Women on board in Lebanon. https://www.ifc.org/ wps/wcm/connect/7435b2c5-04a3-4201-abe2-3f2133b4b8a6/Women_on_Board_in_Lebanon. pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=mN5USK2

Kuschmider, R. (2021, August 11). How to unlearn unconscious bias. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/ balance/features/how-to-unlearn-unconscious-bias#:~:text=Because%20unconscious%20 biases%20are%20based,to%20a%20person%20or%20situation

Mishra, S. (2018, August 13). Women in the C-suite: The next frontier in gender diversity. Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2018/08/13/women-inthe-c-suite-the-next-frontier-in-gender-diversity/

Murray, R. (2015, December 7). Merit vs equality? The argument that gender quotas violate meritocracy is based on fallacies. London School of Economics (LSE). https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/ politicsandpolicy/merit-vs-equality-argument/

Orloff, A. (1996). Gender in the welfare state. Annual Review of Sociology, 22, 51–78. http://www.jstor. org/stable/2083424

Robbins, M., & Thomas, K. (2018, December 5). Women in the Middle East and North Africa: A divide between rights and roles. Arab Barometer. https://www.arabbarometer.org/?report=women-inthe-middle-east-and-north-africa-a-divide-between-rights-and-roles

Suarez, S. (2019, May 28). Four reasons companies can’t afford to ignore unconscious bias in the workplace. Grand Rapids Chamber. https://www.grandrapids.org/blog/diversity/unconscious-biasworkplace/

Tabbara, R. (2021, October 25). Women’s representation in parliament: A tale of plentiful proposals but limited political will. L’Orient le Jour. https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1279197/ womens-representation-in-parliament-a-tale-of-plentiful-proposals-but-limited-political-will. html

Welborne, B. C. (2010). The strategic use of gender quotas in the Arab world. International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES). https://aceproject.org/ero-en/regions/africa/MZ/ifes-the-strategicuse-of-gender-quotas-in-the

Zheng, W., Kark, R., & Meister, A. (2018, November 28). How women manage the gendered norms of leadership. Harvard Business Publishing Education. https://hbsp.harvard.edu/product/H04NZTPDF-ENG

25 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

Unpaid Care Work in Lebanon: A Barrier to Women’s Economic Empowerment

Maria Abi Akl Biology Major

Abstract

The aim of this article is to examine the impact of unpaid care work on women’s economic empowerment (WEE) in Lebanon and to propose a policy solution and a plan of action. The paper begins with a literature review of the causes and effects of unpaid care and highlights previous policies with the aim to produce policy recommendations in Lebanon. Unpaid care has its roots in the discriminatory social norms that judge care as a woman’s responsibility. This view has various repercussions on women, most notably, it hinders women’s economic empowerment. To address these issues, this paper highlights the need for a multidimensional policy centered around the recognition, reduction, and redistribution of unpaid care work. Some of the proposed recommendations include tackling discriminatory social norms through the educational sector and the media, increasing the government’s investment in time-saving infrastructure, and the ratification of non-transferable parental leave policies.

Introduction

Unpaid care work refers to the activities that help meet the various needs of families or community members, whether material, developmental, emotional, or spiritual (Chopra & Sweetman, 2014, as cited in Rost, 2021). Caring for children, the elderly, and doing household chores such as cooking, cleaning, and even fetching water, are a few examples of unpaid care work. Unpaid care work is difficult labor that is essential to any household’s everyday operations, and it is also necessary for strengthening and renewing social bonds between family members and the community (Chopra et al., 2014). Such activities are categorized as work since a person could be paid to do them (Ferrant et al., 2014).

Unfortunately, such work disproportionately falls on the shoulders of women, particularly the marginalized in developing countries. In fact, part of the slow and uneven progress of gender equality and women’s economic empowerment (WEE) programming can be attributed to women’s higher share of unpaid care work (Ferrant & Thim, 2019). Around the world, women spend three times as much time doing

26 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

unpaid care work as men do, ranging from 1.5 times in North America to 6.7 times in South Asia (Ferrant & Thim, 2019). In fact, around 4.1 hours are spent by women every day on domestic work and unpaid care as opposed to 1.7 hours for men, a contribution by women that is estimated to be worth around $11 trillion (Diallo et al., 2020). To respond to this growing problem, Goal 5.4 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) specifically targets girls and women’s unequal share of unpaid care work (Moussié & Alfers, 2018). Particularly, governments are urged to recognize the importance of unpaid care work through infrastructure, public services, policies for social protection, as well as to encourage shared responsibilities in the household (Moussié & Alfers, 2018). Moreover, this target is also considered a prerequisite for SDGs 1, 5, 8, and 10, which target gender equality, the reduction of poverty, inequality, and sustainable development through decent work, respectively (Hammad et al., 2019). The significance of the problem of unpaid care work lies in the lack of recognition and attention attributed to this type of labor, resulting in ineffective solutions, the persistence of the problem, and women increasingly suffering the repercussions. Additionally, unpaid care work often leads to the violation of human rights, especially for women living in poverty, including the rights to education, decent work, social security, health, and the right to enjoy scientific progress, which all ultimately contribute to the hindrance of WEE, as this paper will demonstrate.

Multiple stakeholders are involved in the issue of unpaid care work, first and foremost women and girls, who bear the direct consequences. Other stakeholders include men and boys who can also contribute to unpaid care work. On a national level, the government has a crucial role to play. In Lebanon, this includes the Ministry of Economy, the Ministry of Social Affairs, and even the Ministry of Education. Furthermore, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), private companies, and the educational sector can all play key roles in challenging unpaid care work.

Primary research was not performed in this study. Instead, a cause-and-effect approach was applied during the literature synthesis and review, in which the causes and effects of the problem were gathered, reviewed, and synthesized from several sources. Additionally, this paper reviewed both former and current policies related to the problem of unpaid care work with the intention of making several recommendations to ameliorate the problem going forward.

Literature Review

The aim of this paper is to examine the impact of unpaid care work on WEE in Lebanon and to propose, in addition to previous studies, recommendations and policies to tackle this issue. The proposed hypothesis is as follows: Unpaid care work represents a barrier to WEE in Lebanon. Studies have been conducted to shed light on unpaid care work and demonstrate its impacts on several levels and in multiple countries. This paper adds to the existing body of literature by specifically analyzing the impact of unpaid care work on WEE in Lebanon.

Causes

The causes of unpaid care work have been investigated by researchers around the world. Routine housework takes up the majority of women’s unpaid care time, followed by caring obligations, but this varies depending on a country’s economic growth

27 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

(Ferrant & Thim, 2019). Unpaid care is prevalent in all countries but especially in poor and developing countries. Women performed more unpaid care in poor households due to lower-quality infrastructure, larger families, and a reduced ability to purchase care services (Razavi, 2016). In low-income countries, up to 14 hours each day are allocated by women in rural areas to unpaid care work (Oxfam International, 2020). However, inequalities in caring obligations remain even in households with greater wealth and education, as women dedicate more than 60% of their time to housework and care, regardless of their work status, pay, or education levels (Ferrant et al., 2014). Social norms influence gender roles by defining which behaviors are socially appropriate and acceptable: In most societies, paid work is perceived as a masculine task, whereas unpaid care work is recognized as a woman’s duty (Ferrant et al., 2014). Girls and boys are assigned different household and care responsibilities from an early age (Ferrant & Thim, 2019). Women’s domestic and care responsibilities change over time, with unpaid care work increasing significantly when they marry and have children, with more time spent on childcare and household chores during motherhood (Ferrant & Thim, 2019). Furthermore, mothers-in-law often pressure young and newly married women to “show their value” by completing more difficult chores (Marphatia & Moussié, 2013). While marriage and parenthood result in higher amounts of unpaid care work, the opposite is true for men; although fatherhood results in more time spent on childcare, men’s time spent on ordinary housework actually reduces after a child is born, as the mother staying at home with the child performs the majority of household tasks (Ferrant & Thim, 2019).

In Lebanon, gender inequality is severe. In fact, according to the Gender Gap Index, Lebanon is ranked 135 out of 144 nations (Avis, 2017), and is ranked third to last in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, with only Syria and Yemen having worse gender gap scores, ranking at 142 and 144, respectively (Avis, 2017). In a study on the impact of socialization on gender discrimination and violence in Lebanon, results revealed that from an early age, boys are given entitlement over their sisters by society and parents (Avis, 2017). The way that boys are raised gives them superiority and dominance over women. According to one study, when questioned about the characteristics that make up a “perfect” woman, respondents primarily mentioned being “obedient,” “devoted to her family,” “being a good housewife and mother,” and “maintaining the reputation and dignity of her spouse,” but qualities linked to education, for example, were rarely mentioned (Hamieh & Usta, 2011, p. 14 as cited in Avis, 2017). These ideas confirm that discriminatory social norms are a major contributing factor to unpaid care work.

Effects

Unpaid care has tremendous consequences that mostly affect women. Due to unpaid care work, women around the world are left with little time on their hands to pursue an education, find a decent job, be active members in their communities, or voice their opinions in society, which works to keep them trapped at the lower end of the economy (Oxfam International, 2020). They have a lower probability of engaging in paid work, and those who do are more likely to be limited to informal or part-time jobs, causing them to earn less than their male counterparts (Ferrant et al., 2014). This in turn leads to the dependence of women on someone else, mostly their spouses, for their income, hindering WEE. Entrenched gender norms dictate that women are more likely

28 al-raida Vol 47 No. 1 (2023)

to sacrifice their paid jobs for the sake of unpaid care (Mercado et al., 2020). This is reflected by labor force participation rates in Lebanon, which is 23.5 % for women and 70.3 % for men (UNDP, 2016, p. 6, as cited in Avis, 2017). Women worldwide prefer flexible and less-regular work as it permits them to care for their children (Moussié & Alfers, 2018). However, flexible work is often poorly remunerated (Qi & Dong, 2015). Eventually, more time spent on unpaid care work leads to reduced time for paying jobs, education, rest, and self-care (Rodriguez, 2021), which compromises women’s access to their human rights and their economic empowerment. Regarding the right to education, disproportionate care responsibilities can lead to girls and women dropping out of school or university, limiting the time and energy they can dedicate to education and extracurricular activities, and limiting their progress and opportunities (Public Services International [PSI], 2021). Unequal unpaid care might also prevent women from entering the labor force, or it might push them to accept low-wage, informal, and unstable occupations with little or no social security, thus hindering the rights to decent work and social security (PSI, 2021).

Unpaid care can be demanding, both physically and emotionally, negatively affecting women’s health (PSI, 2021). Psychological problems such as depression and anxiety, as well as physical and emotional distress could all result from this immense workload and the lack of respite for women (Seedat & Rondon, 2021). In addition, lack of access to technologies and services, such as suitable energy sources or piped water, can jeopardize their right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress (PSI, 2021). In conclusion, the unequal distribution of unpaid care work due to discriminatory social norms jeopardizes women’s rights to equality and non-discrimination (PSI, 2021). Finally, on a long-term scale, children will see their mothers at home and start internalizing the idea that the household is where women “belong,” thus further engraving and strengthening the discriminatory social norms that are at the root of unpaid care work.

Policy Synthesis