5 minute read

Kate Mulgrew

THE SWIRLING BLUE-GRAY WATER of the Hudson River dominates the view from Kate Mulgrew’s 11th-floor apartment on New York’s Upper West Side. “Many, many times it’s saved me,” she says, gesturing with a dramatic sweep of her arm toward the window. “You look out there and forget that you’re in a city. Because we all seek solitude—I know I do—surely as much as we seek society.” In the sunshine, Mulgrew’s hair is a wheaty gold, much softer than the vermilion lion’s mane she wears as Red, the cranky Russian jailbird on Orange Is the New Black.

Her mouth is ungrimaced. But as she gazes out the window at the colorless industrial New Jersey coastline, a smile creeps onto her lips. “New Jersey could really do something about its shores, don’t you think? Look at this nonsense, it’s so bad. I mean, what would it take to fix that?” Her voice rises in feigned hauteur: “For no other reason than to please our eyes.”

Advertisement

That’s the kind of candid, jaunty, pinch-of-sarcasm verbiage that graces the pages of Mulgrew’s memoir, Born With Teeth (on sale April 14). Written with a marvelous flair for anecdote and detail, the book recounts her childhood as a member of a big Iowa family so Irish Catholic that her mother danced with JFK at his inaugural ball. Young Kate was exposed to Spinoza and Shakespeare, but also to life’s cruelties with the deaths of two sisters. Her parents were rich in charm (sample bon mot from her mother: “If you ever call a man on the telephone, you will get cancer of the hand”) but emotionally repressed. “Shadow and light is the Irish way,” she says over coffee in her bright living room. “What is hidden remains hidden. It can be beautiful and it can be quite painful.”

Hiding was never Mulgrew’s style. After high school she made her way to New York and into the classroom of famed drama teacher Stella Adler. By 20 she was starring on the new soap Ryan’s Hope by day and shuttling to Connecticut every night to play the lead in a Stratford production of Our Town. Her course was set, and two decades of steady work on stage, TV, and film followed, including topline roles on Mrs. Columbo and HeartBeat and guest spots on Cheers and Murder, She Wrote. She moved to Seattle, then L.A., with her theater-director husband and their two sons. (They split in 1993; she later married Ohio politician Tim Hagan.) In 1995 she made history as Star Trek: Voyager’s Capt. Kathryn Janeway, the only female skipper in the sci-fi franchise, and the part she regards as her greatest success.

But all that time, she was nursing an injury that wouldn’t go away. At 22 she’d given birth to a girl and only glimpsed her before the child was untraceably adopted. “I could not have known the pain and regret I would feel so quickly afterwards,” she says. “That’s what the book is about. How the search for my

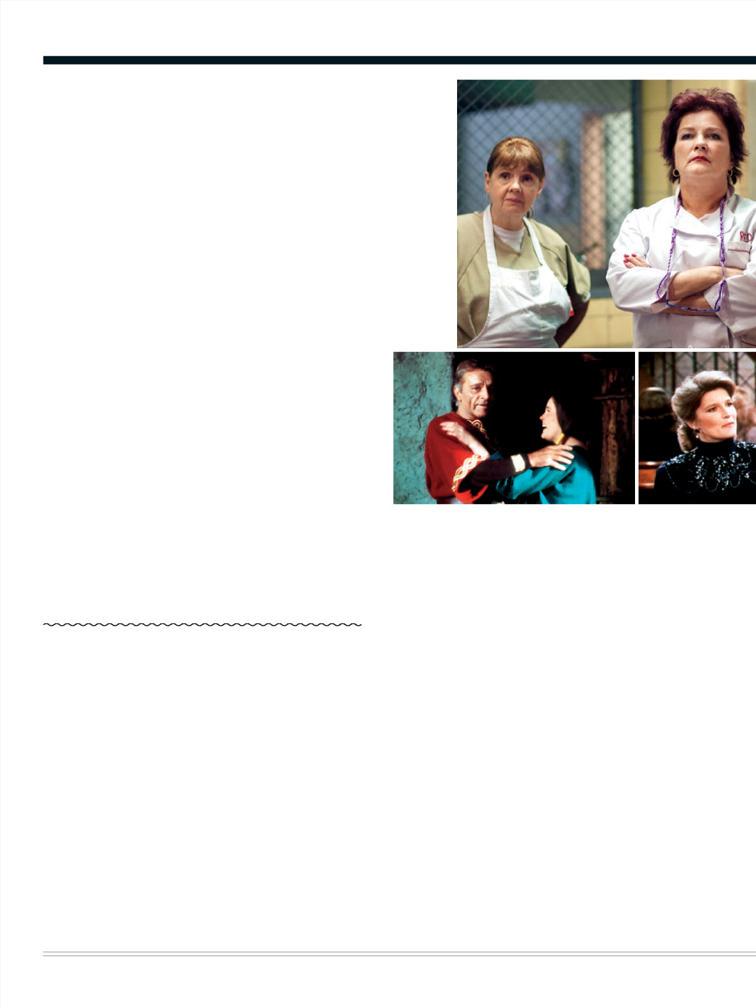

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT Annie Golden, Kate Mulgrew, and Abigail Savage on Orange Is the New Black; Mulgrew on Star Trek: Voyager; meeting her biological daughter, Danielle; with Shelley Long on Cheers; with Richard Burton in Lovespell

daughter would set me on this 20-year path towards reclamation.” Her account of the quest, which concludes with a reunion scene that’s tearful in its delicateness, isn’t even the memoir’s most harrowing passage. In one paragraph that runs four pages long, Mulgrew describes being assaulted and raped by a stranger in her Manhattan apartment hallway. “The only way to write about it was to write about it honestly. It’s the sharing of the thing that a lot of women struggle with. But it was so random, that this guy just targeted me. Why should I be ashamed of that?”

Many of her professional memories, however, center on what she calls the “eccentricity of genius.” Geraldine Page, walking into a restaurant in a long raccoon coat, her breasts visible as she greeted Mulgrew. Richard Burton, in the book’s tastiest chapter, offering the inexperienced Mulgrew advice: “This business will kill you.... It’s no place for a real man and it’s death to a good woman. Get the f--- out before it’s too late.”

She believed him. “He importuned me, as only a Welshman could, to save my soul. Having relinquished his, I think, to the dogs. His absolute message was: Real people don’t do this. And then he was left to his whiskey, and I of course went into the other room and had a whiskey of my own. I totally got Burton that night, but I threw his advice away, because I was going to be the exception.”

Judging by the past two years, especially, she has been. Orange Is the New Black (its third season, which she reveals will be lighter in tone, is available on Netflix June 12) has given Mulgrew’s

IS IT HARD TO LET GO OF YOUR BEAUTY? YES, VERY. I WAS PRETTY, SO IT’S TOUGH. BUT WHY WOULD I PUT A KNIFE TO MY FACE AND THINK THAT’S GOING TO REVERSE TIME?” career a new lift. She earned her firstever Emmy nomination last year. “I will be 60 this month,” she says. “I couldn’t play Red at 35. I’m no longer cast for my sexuality or physical charisma, so in a way it’s freeing.” (Free to write more as well. Born With Teeth ends in the late ’90s, before the success of Tea at Five, her uncanny one-woman stage show about Katharine Hepburn, and OITNB. Asked about another memoir, she says, “That may come.”)

She laughs when discussing plastic surgery. “I’ve never once danced around my age or clearly, now, my face. Is it hard to let go of your beauty? Yes, very. I was pretty, so it’s tough. But why would I put a knife to my face and think that’s going to reverse time? It’s absurd. And for what, to get a role on a sitcom or a cameo in a feature film? No, you do that and you’re not believable as anything other than the movie star you so need to be, or else you’ll disappear. I’m not interested in pretending to be other than who I am.” ■