CAMELOT

SPRING 2023 ISSUE NO. 78

Lincoln Center Theater Review

A publication of Lincoln Center Theater

Spring 2023, Issue Number 78

Lincoln Center Theater Review Staff

Alexis Gargagliano, Editor

John Guare, Executive Editor

Jenna Clark Embrey, Executive Editor

Charlotte Strick, Design

Jenny Pouech, Picture Editor Carol Anderson, Copy Editor

Lincoln Center Theater Board of Directors

Kewsong Lee, Chair

David F. Solomon, President

Jonathan Z. Cohen, Jane Lisman Katz, Robert Pohly, and John W. Rowe, Vice Chairs

James-Keith Brown, Chair, Executive Committee

Marlene Hess, Treasurer

Brooke Garber Neidich, Secretary

André Bishop

Producing Artistic Director

Annette Tapert Allen

Allison M. Blinken

Judith Byrd

H. Rodgin Cohen

Ida Cole

Ide Dangoor

Shari Eberts

Curtland E. Fields

Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Cathy Barancik Graham

David J. Greenwald

J. Tomilson Hill, Chair Emeritus

Judith Hiltz

Sandra H. Hoffen

Linda LeRoy Janklow, Chair Emeritus

Raymond Joabar

Eric Kuhn

Ninah Lynne

Phyllis Mailman

Ellen R. Marram

Scott M. Mills

Eric M. Mindich, Chair Emeritus

John Morning

Elyse Newhouse

Rusty O'Kelley

Andrew J. Peck

Katharine J. Rayner

Stephanie Shuman

Laura Speyer

Leonard Tow, Vice Chair Emeritus

Tracey T. Travis

David Warren

William Zabel, Vice Chair Emeritus

Betsy Kenny Lack

John B. Beinecke, Chair Emeritus

John S. Chalsty, Constance L. Clapp, Ellen Katz, Memrie M. Lewis, Augustus K. Oliver, Victor H. Palmieri, Elihu Rose, and Daryl Roth, Honorary Trustees

Hon. John V. Lindsay, Founding Chair

Bernard Gersten, Founding Executive Producer

The Rosenthal Family Foundation— Jamie Rosenthal Wolf, Rick Rosenthal and Nancy Stephens, Directors is the Lincoln Center Theater Review’s founding and sustaining donor.

Additional support is provided by the David C. Horn Foundation.

Our deepest appreciation for the support provided to the Lincoln Center Theater Review by the Christopher Lightfoot Walker Literary Fund at Lincoln Center Theater.

To subscribe to the magazine, please go to the Lincoln Center Theater Review website—lctreview.org.

Front cover photograph © Nick Psomiadis; (right) Medieval Television © David Gander; (opposite page) chain mail © Creative Market. Back cover images: Glastonbury Abbey courtesy of the Library of Congress; Marbling art © ranasu/iStock/Getty Images.

© 2023 Lincoln Center Theater, a not-for-profit organization. All rights reserved.

Issue 78 THE MUSIC & THE MYTH: AN INTERVIEW WITH BARTLETT SHER 4 FROM A TROUBLED HEART SADIE STEIN 8 T. H. WHITE’S FINGERPRINTS CONSTANCE GRADY 10 EXCERPT FROM THE STREET WHERE I LIVE ALAN JAY LERNER 12 REARRANGING ELECTRONS: AN INTERVIEW WITH AARON SORKIN 14 LOVE & POLITICS KATE ANDERSEN BROWER 18

A LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

This edition of the Lincoln Center Theater Review is dedicated to the revival of an iconic musical, Camelot, directed by Bartlett Sher, whom our audiences will know from many productions, including South Pacific, The King and I, Oslo, My Fair Lady, and To Kill a Mockingbird, which was adapted for the stage by Aaron Sorkin. Now Sher and Sorkin are again collaborating on Camelot— a different kind of story about political ideals. Sorkin’s new book gives a more modern sheen to Guenevere and Arthur and challenges assumptions about power and goodness, idealism and humanity, making this old story new again.

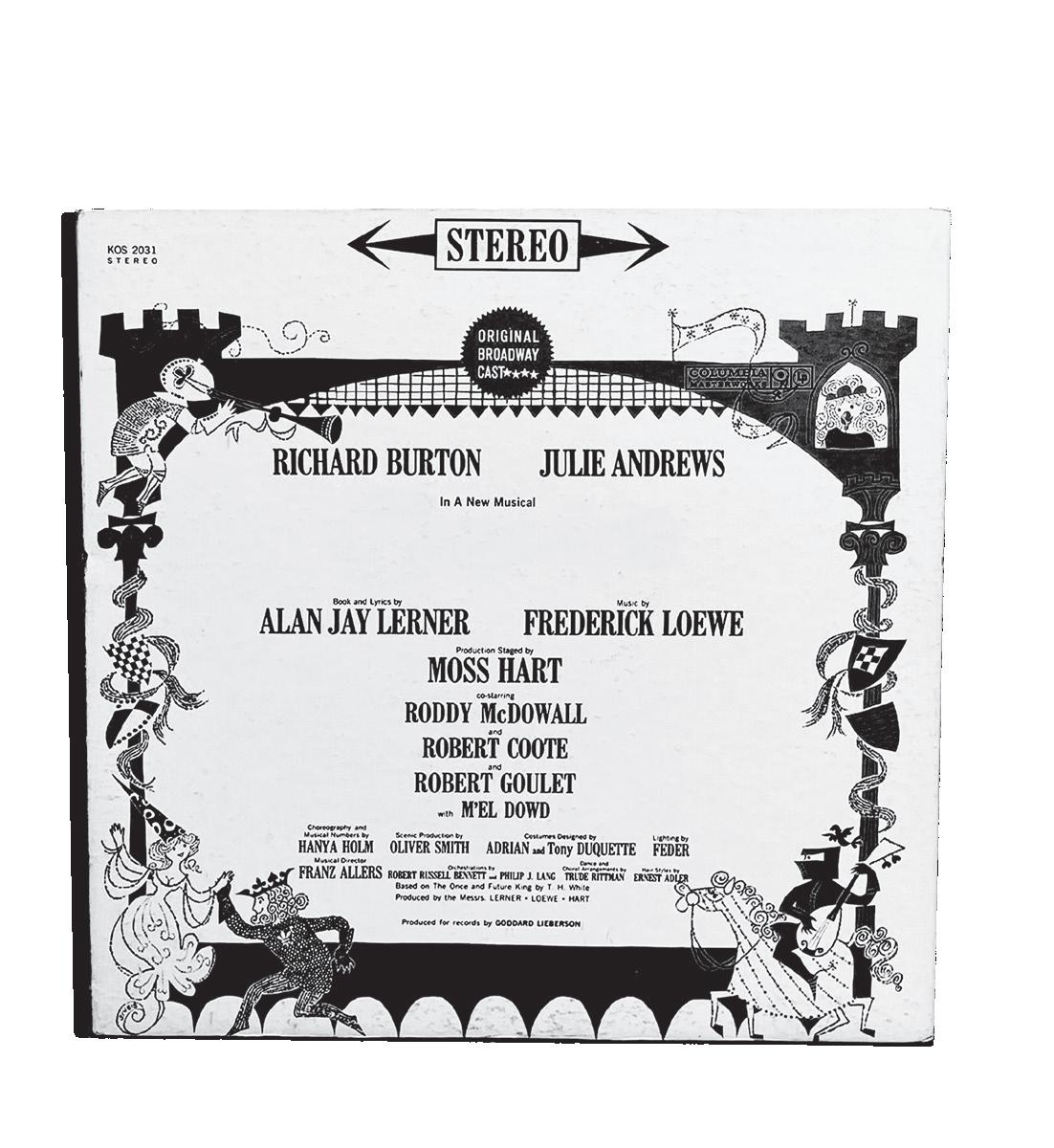

The legend of King Arthur dates back to the Middle Ages, and has been retold and reimagined in myriad ways. Perhaps the best-known modern versions are T. H. White’s The Once and Future King, a 1958 collection of fantasy novels about King Arthur published from 1938 to 1940, the most famous of them being The Sword in the Stone, which was turned into a Disney animated film in 1963. And, of course, the Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe 1960 musical Camelot, which was based on White’s work.

This issue of the Lincoln Center Theater Review is filled with history, romance, and myths of one kind or another. Bartlett Sher spoke to us about the journey of this production, his childhood in San Francisco, and the way in which a culture draws on its old myths. The writer Sadie Stein offers a portrait of the lonely life of T. H. White. The journalist Constance Grady describes the outsized influence The Once and Future King has had on pop culture, from Harry Potter to Star Wars. We have an excerpt from the memoir of Alan Jay Lerner about the effect that President Kennedy’s assassination had on the myth of Camelot and the musical itself, which the President loved. Aaron Sorkin talks to us about his love of musical theater, Don Quixote, and his own penchant for the Romantic. The biographer Kate Andersen Brower examines how politics infuse the marriages of many first couples.

Together with the production, these wonderful writers invite us to look at the way that myths are made, revisited, and reimagined.

Camelot is filled with wit and beloved music, but also with big ideas about political idealism— its optimism, its failures. It questions our assumptions about morality and our ideas about power—what it is and what it is for. Sher says, “Revivals always come around when you need them to,” and this Camelot seems to be coming around at a moment when we are collectively questioning and striving for something better.

The magazine also welcomes our newest staff member, Jenna Clark Embrey. Jenna is the new literary manager and dramaturg for Lincoln Center Theater, and will join John Guare as the co-executive editor of the Lincoln Center Theater Review.

Finally, since our 2006 The Coast of Utopia issue, I have had the privilege and pleasure of editing the Review, working with the genius staff to produce a publication of beauty and ideas conceived with the sole purpose of inviting theatergoers to explore a production more fully. While my work on the magazine has been a joy and I will miss it, I am looking forward to joining you, dear reader, and enjoying the pages of this extraordinary publication from my seat in the theater.

Alexis Gargagliano

The Music & The Myth

doing another Lerner and Loewe musical at the time, My Fair Lady. I thought, Camelot? Richard Burton? But then I learned that Lin-Manuel Miranda loved the show, and that it was his mother’s favorite musical. I said, “Lin, you have to help me.” He really, really loved it. He loved everything about what it did as a musical, and that opened me up to something I hadn’t expected. He was a great spirit in exploring it. It was a wonderful experience in the theater, but at the end I came to the very same conclusion everyone else had: that it was not a very good book.

AG: Did you know right away that you wanted someone to write a new book?

BS: After the gala, I asked Lin who he thought could write a new book. Immediately, he said, Aaron Sorkin.

While he was working on casting Camelot, the director, Bartlett Sher, spoke to our editors from his office at Lincoln Center Theater about his revival of the beloved musical. Sher has directed a breathtaking list of plays and musicals that Lincoln Center Theater’s audiences will remember, including To Kill a Mockingbird, South Pacific, and My Fair Lady.

JOHN GUARE: Our audiences will remember your revival of My Fair Lady, in which, without changing anything, you solved the problem of My Fair Lady in this jaw-dropping ending, in which she brings his slippers and then runs off. That gave My Fair Lady brand-new life. Why Camelot now?

BARTLETT SHER: Well, with My Fair Lady I think we were restoring the story to Shaw’s intentions. Eliza’s return with the slippers was introduced in the 1938 movie of Pygmalion, which Shaw wrote, because the studio wanted a happy ending. The people who made the musical bought the rights to the movie. We simply adhered to Shaw’s original vision. So, from a revival point of view, Camelot is a very different kettle of fish. It’s a musical that has incredible music—music that is absolutely beloved—but it didn’t really have a book that held up to the larger story.

I think Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe’s initial intentions were to capture T. H. White’s very popular book, The Once and Future King—they have all this crazy magic in the book that wasn’t easy to accomplish onstage. There are stories of what a nightmare it was to produce. Moss Hart had a heart attack while they were on the road, and the journey to creating it was troubled.

JG: There’s the story of Moss Hart being wheeled into the hospital as Alan Lerner was being wheeled out of the hospital, and Lerner said, “This isn’t a musical, it’s a medical.” (Laughter)

BS: But, in the wake of Kennedy’s assassination, four years after the show had opened and closed in New York, this somewhat nostalgic, romantic musical, largely built on a kind of longing for some weird, misty place in English history, got grafted over a longing for an American Presidential universe that had been taken away. And the musical, and the idea of Camelot itself, garnered a big place in the consciousness through the music and through these myths that grew up around it.

ALEXIS GARGAGLIANO: What sparked this revival of Camelot?

BS: André Bishop [Lincoln Center Theater’s producing artistic director] suggested we do it for the Lincoln Center Theater gala, since we were

JG: If Camelot’s original book wasn’t great, what did the show deliver?

BS: I think it delivers a level of romance, and that you really feel the nostalgia for something missing or lost. You chart Arthur’s losing his bride and losing his kingdom, while knowing that he had been onto something great, which gives it a deeper, mythical kind of strength, which seems to push through no matter what. The thing that is moving is watching everyone accept one another in their failure, and watching everyone move ahead, even though mistakes were made. Arthur sees that he’s married to a woman who is obviously falling in love with somebody else. And his ability to accept these contradictions is very moving.

JG: I was surprised when I read a draft of the book and there was a reference to Voltaire and the Age of Enlightenment pops up. I thought, Wait a minute, we’re in the Middle Ages, aren’t we?

BS: Aaron didn’t want to look at time in such a linear way, so that all the influences of the thing we’re making are layered together.

AG: To create something out of time and place—mythological.

BS: Tadeusz Kantor, the Polish painter and director, influences all my work. He’s on the wall back there [gestures toward the poster hanging behind him]. He would say every work of art has its

5 BARTLETT SHER

AN INTERVIEW with BARTLETT SHER

Clockwise from bottom left: Ivy © imageBROKER/ Alamy; Frederick Loewe and Alan Jay Lerner © RBM Vintage Images/Alamy; Crown © Cheri Doucette/Alamy; Sword and The Stone book jacket. Reprinted by permis-

sion of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd © 1938, T. H. White; Bartlett Sher © John Lamparski/WireImage/Getty Images; Knight's helmet © mccool/Alamy; Feather courtesy of the Graphics Fairy; Aaron Sorkin © Gary

Hershorn/Reuters/Alamy; Sword © Denis Rozhnovsky/ Alamy; Foil over sword © Aitthiphong Khongthong / Dreamstime.com; Castle © Malcolm Fairman/Alamy; Gauntlet © Sergey Klopotov/Dreamstime.com.

own autonomous logic. I’m building my own autonomous logic—where Voltaire can be referenced and in a time that feels like the Middle Ages . . . except that it isn’t. I feel like Camelot doesn’t need to happen in a specific year. We’re making our version. Aaron has made the marriage more political. He’s made the stress more real. He’s gotten rid of all the magic. He likes the political idea that maybe Arthur pulled the sword out of the stone, but, as Guenevere reminds him, ten thousand people loosened it before him, which is a very big, democratic idea, as opposed to a magical one, and that’s very central to his point of view.

JG: Tell us a little more about Kantor.

BS: It’s his principle that you have to have what he called the sustained radicalism of the painter, where each time you move on to a new board you’re rejecting what you did before to make something new. With each new piece he wrote, he wrote a new manifesto, rejecting everything he’d done before and starting over again, in a pure spirit of the avant garde. He also made a distinction between the interpretive artist and the creative artist. I, the director, am the interpretive artist; you, the writer, are the creative artist, and they are very different impulses. That’s where Kantor has always fueled and supported me to try different things within the sort of safer environment of interpretive arts.

JG: What was the first musical you saw?

BS: I grew up in San Francisco in the sixties and seventies, and when I was eleven my family took me to see Hair. I sat next to my mom and the actors all took their clothes off, and I thought, What the heck is going on? And I thought it was really amazing. I remember them crawling onto the

stage, and I remember afterward leaving and seeing a couple of the actors coming out of the stage door and heading off into the night, and I thought, Oh, that must be a really cool life. Also, around that same time, I saw my first Grateful Dead concert, which was just as insane, but I thought it was really fun and very communal.

AG: The way you talk about San Francisco, it struck me as its own kind of Camelot.

BS: I do feel very lucky for growing up there. It was a very special time; it was so out of control, and it was going through such transformation. And it prepared me for everything else. When I went to Massachusetts, to Holy Cross College, I thought, This is so ordinary compared to where I grew up. It was as if I’d stepped out of a spaceship. But I think that’s an interesting link, because my growing up in San Francisco was very special and very tumultuous. My parents divorced, so I was going through a lot, but the city itself was filled with these extremely creative endeavors.

JG: How much of the rehearsal process is an act of discovery for you?

BS: About ninety percent. I have a lot of points of view, and a lot of work to do before we get there to ask the questions at the highest possible level, but you always have to be ready to go in some new direction if you discover something you didn’t expect halfway through.

JG: So you’re open to accidents happening?

BS: Oh! Accidents are critical. I think one of the illusions about directors is that somehow they have this received vision that they then prove to everyone as they move through the process, as opposed to an approach that they then use as an active exploration of a text. My job is assembling all that

information and selecting and pulling it together into a whole that’s going to be shared by all of us as we get there.

AG: I realize it’s early, but what can you tell us about the world that you’re creating?

BS: We’re going to build our own version of Camelot, our own version of this world, with our own sense of movement, with our own kind of structure to it, and explore it to kind of mirror who we’re becoming now, and who we are. I’m really interested in how Ariane Mnouchkine builds her company at Le Théâtre du Soleil— through mask work and movement work. Working with all of our actors and singers, we will try to build a physical world. I’m interested in approaching a musical in the American canon in a different way, through movement, because Camelot doesn’t operate the way most musicals do—it has no dances, no traditional numbers.

I’m going to try and build a company, and build a world to deliver what I think is a very powerful story, to get underneath the fingernails of both our own mythology about Camelot, our own mythology about democracy and lost democracy, and ideas that are good, and see if we don’t find ourselves with Arthur in this very ambivalent place—as a country, as a human being, as we look into the future. The show’s ending is very touching and very complicated—it is filled with hope, but also with lots of dread and doubt. I always say these revivals always come around when you need them to, and this Camelot seems to be coming around with some comfort for a dreaded future.

AG: I’m interested in your comment that revivals come back when we need them most as a society. When did you start having these discussions about the political optimism and hope in the show?

BS: Well, the hope and optimism are written in there. But one of the things I think theater can do is, within a culture, go to its old myths and use them to help reignite and sustain some core, almost subconscious, almost metaphoric connection to who we are.

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW 6

[SORKIN] LIKES THE POLITICAL IDEA THAT MAYBE ARTHUR PULLED THE SWORD OUT OF THE STONE, BUT, AS GUENEVERE REMINDS HIM, TEN THOUSAND PEOPLE LOOSENED IT BEFORE HIM, WHICH IS A VERY BIG, DEMOCRATIC IDEA, AS OPPOSED TO A MAGICAL ONE . . . .

I don’t make it specific, because I think then it gets didactic. There’s some other thing that happens. . . . I don’t know if it’s gathering on the hillside with the Greeks to tell the old tales of your culture, but it feels like there’s some special search that goes on when a culture comes to hear its old stories and wonder who we are now based on who we were when we first saw it. That’s one of the exercises of theater. The Hamlet I saw when I was sixteen is different from the Hamlet I’m seeing when I’m fortyfive. Revisiting our stories invites us to ask good, hard, powerful questions, and to examine what we’re working on and toward. This revisiting of our stories does this kind of subconscious healing, or strengthening, of a culture. I hope, somewhere in Camelot, you will get a chance to at least, even subconsciously, reconnect with something. Of course, I’m trying to do it in a different way, and I’m trying to look at it differently, but it is still about reconnecting with our old stories, which is the best way in which the spirit of a revival can hit you.

Preceding page: Sheet music for ‘If Ever I Would Leave You’ from Camelot

Top row (left to right): Ava Gardner taking a break while filming, Knights of the Round Table, 1953 © PictureLux/The Hollywood Archive/Alamy; Camelot street sign © eyecrave productions/iStock/ Getty Images; Camelot Castle music box.

Middle row (left to right): Reproduction of original signpost prop from Monty Python and the Holy Grail; Camelot Music store t-shirt courtesy of oldschoolshirts.com; Camelot Casino gaming token; Camelot, 1960, original cast rehearsal with Julie Andrews. Photo by Friedman-Abeles © The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

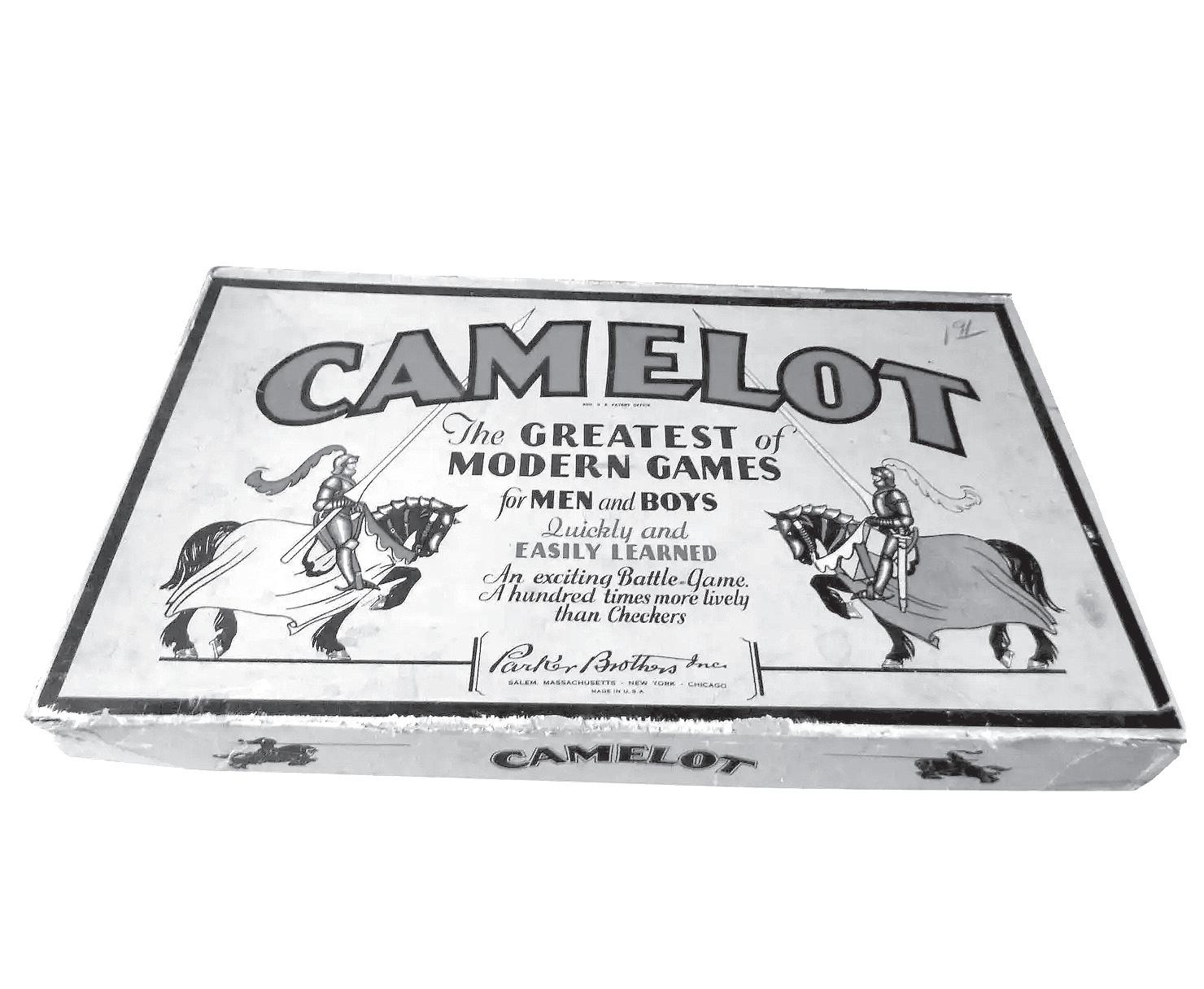

Bottom row (left to right): King Arthur ceramic Toby mug; Camelot board game box c. 1930s; Sir Lancelot and Guenevere Madame Alexander dolls; Camelot Casino gaming token.

Top row (left to right): Ava Gardner taking a break while filming, Knights of the Round Table, 1953 © PictureLux/The Hollywood Archive/Alamy; Camelot street sign © eyecrave productions/iStock/ Getty Images; Camelot Castle music box.

Middle row (left to right): Reproduction of original signpost prop from Monty Python and the Holy Grail; Camelot Music store t-shirt courtesy of oldschoolshirts.com; Camelot Casino gaming token; Camelot, 1960, original cast rehearsal with Julie Andrews. Photo by Friedman-Abeles © The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Bottom row (left to right): King Arthur ceramic Toby mug; Camelot board game box c. 1930s; Sir Lancelot and Guenevere Madame Alexander dolls; Camelot Casino gaming token.

From a Troubled Heart

SADIE STEIN

LIKE MOST PEOPLE, I came to T. H. White from his epic The Once and Future King, the basis for countless adaptations and, of course, Camelot. He shaped my idea of the Arthurian legend and the countless figures who populate our cultural imagination. But I didn’t really come to understand the man until I read his biography. Perhaps you’ve read Sylvia Townsend Warner’s short stories, or the volumes of poetry she wrote (some with her partner, Valentine Ackland). But my favorite book, and the one I return to most often, is her 1967 biography, T. H. White, a small masterpiece of humanity. White, born in 1906 and known to his friends as Tim, was the author not just of The Once and Future King but of a number of successful sci-fi titles. A former teacher, he was prone to passionate enthusiasms—among them falconry and snakes—and wrote a memoir about his experience training a goshawk (which, in turn, inspired Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk.)

Townsend Warner captures his boundless excitement about these things, his humor, his kindness. But, more than anything, this is a portrait of loneliness. White had an unhappy and isolated childhood in Bombay, where his father, an alcoholic, was superintendent of the Indian police. He and White’s mother, said to have been emotionally withholding, separated when Tim was fourteen. In later life, he had no known relationships with men or women. Townsend Warner speculates that White was “a homosexual and a sado-masochist,” although others disagree on the question of his sexuality. In any case, he

was profoundly alone, and his work was colored with a shame and a self-protection that are painfully visible between every well-known line. Townsend Warner wrote, “Notably free from fearing God, he was basically afraid of the human race.”

He did love his dog, an Irish setter called Brownie. Townsend Warner writes extensively about his bond with Brownie, the love he could not express in other facets of his life. Upon Brownie’s unexpected death, he wrote the following heartbreaking letter to his friend David “Bunny” Garnett, presented in its entirety on the Futility Closet blog. Read this only if you are feeling emotionally tough:

Dearest Bunny,

Brownie died today. In all her 14 years of life I have only been away from her at night for 3 times, once to visit England for 5 days, once to have my appendix out and once for tonsils (2 days), but I did go in to Dublin about twice a year to buy books (9 hours away) and I thought she understood about this. To-day I went at 10, but the bloody devils had managed to kill her somehow when I got back at 7. She was in perfect health. I left her in my bed this morning, as it was an early start. Now I am writing with her dead head in my lap. I will sit up with her tonight, but tomorrow we must bury her. I don’t know what to do after that. I am only sitting up because of that thing about perhaps consciousness persisting a bit. She has been to me more perfect than anything else in all my life, and I have failed her at the end, an 180-1 chance. If it had been any other day I might have known that I had done my best. These fools here did not poison her—I will not believe that. But I could have done more. They kept rubbing her, they say. She looks quite alive. She was wife, mother, mistress & child. Please forgive me for writing this distressing stuff, but it is helping me. Her little tired face cannot be helped. Please do not write to me at all about her, for a very long time, but tell me if I ought to buy another bitch or not, as I do not know what to think about anything. I am certain I am not going to kill myself about it, as I thought I might once. However, you will find this all very hysterical, so I may as well stop. I still expect to wake up and find it wasn’t. She was all I had.

Love from Tim

Shortly afterward, he added,

Dear Bunny,

Please forgive me writing again, but I am so lonely and can’t stop crying and it is the shock. I waked her for two nights and buried her this morning in a turf basket, all my eggs in one basket. Now I am to begin a new life and it is important to begin it right, but I find it difficult to think straight. It is about whether I ought to buy another dog or not. I am good to dogs, so from their point of view I suppose I ought. But I might not survive another bereavement like this in 12 years’ time, and dread to put myself in the way of it. If your father & mother & both sons had died at the same moment as Ray, unexpectedly, in your absence, you would know what I am talking about. Unfortunately Brownie was barren, like myself, and as I have rather an overbearing character I had made her live through me, as I lived through her. Brownie was my life and I am lonely for just such another reservoir for my love. But if I did get such reservoir it would die in about 12 years and at present I feel I couldn’t face that. Do people get used to being bereaved? This is my first time. I am feeling very lucky to have a friend like you that I can write to without being thought dotty to go on like that about mere dogs. They did not poison her. It was one of her little heart attacks and they did not know how to treat it and killed her by the wrong kindnesses. You must try to understand that I am and will remain entirely without wife or brother or sister or child and that Brownie supplied more than the place of these to me. We loved each other more and more every year.

It’s true, White’s ending was as lonely as much of his life. But his generosity to younger writers was legendary, and his work has influenced everyone from J. K. Rowling to Ed McBain and Gregory Maguire, the author of Wicked . And he informed our attitudes toward the enduring mythology of the home he never knew in childhood. Although he was too young to serve in World War I, White would have had a youth informed by despair and the nihilism that followed. His solution was to create a work of escapism—both rooted in a reassuring myth of ancient Britain and profoundly modern— that continues to move and inspire today. And, in

creating an enduring vision of chivalric romance, he has touched anyone who has known isolation, shame, or fear—which is to say, all of us.

All this might seem a far cry from Lerner and Loewe’s epoch-defining 1960 musical. White, who died in 1964, would have lived to see it, although he was quite solitary by that point. But, in fact, I’d argue that there’s a thread of compassion and loneliness that the composers captured. This is, ultimately, a story about people searching for connection. And I can’t help thinking of White’s epitaph: “Author who from a troubled heart delighted others.”

An earlier edition of this essay appeared in The Paris Review.

SADIE STEIN is a writer and editor living in New York.

9 SADIE STEIN

Framed photo: T. H. White Collection. Harry Ransom Center; carved wood frame courtesy of THEDNAGROUPJODHPUR/Etsy.

T. H. WHITE’S FING ER PRINTS

CONSTANCE GRADY

TH. WHITE’S THE ONCE AND FUTURE KING is the definitive King Arthur story of the twentieth century, and it is born of tragedy and repression. White had a miserable childhood, and an adulthood of squandered hopes. His parents were by turns neglectful and abusive. He grew up gay, sadistic, and profoundly ashamed of both. Out of his pain he created a masterpiece: a work of legend and wonder, rooted in the human pain that he understood all too well. It’s in the odd position of being both deeply influential and half forgotten.

“I often wonder why White isn’t considered one of the founding fathers of modern fantasy, the way Tolkien and C. S. Lewis are,” The Magicians author, Lev Grossman, mused to NPR in 2010. “Perhaps one day, in the future, he will be.”

The Once and Future King is a loose adaptation of Thomas Malory’s fifteenth-century book Le Morte d’Arthur. Malory’s version of the King Arthur legend is one of the most foundational texts in the English canon, so much so that John Milton considered adapting it before he settled on Genesis as the source for Paradise Lost.

White first encountered Le Morte d’Arthur as a student at Cambridge, where he wrote his thesis on it. Where Milton did not venture, White decided to plant his flag. He felt, he wrote in excited letters to friends, as though he really understood Malory’s characters. He knew what they would do under any circumstances. He could make a book out of them.

Much of what White read into Malory’s characters came from his own life. He wrote the best of his childhood, which he spent living under

Left: Le Morte d’Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory, 1894 book spine design by artist Aubrey Beardsley from Volume 4 of The Studio Magazine © past art/Alamy.

the benign neglect of his grandparents, into Arthur’s orphaned idylls. The worst of it he gave to the tragic children of the witch Morgause. An idealized portrait of his professional persona as a teacher became Merlin. White’s deep and longlasting shame he attributed to Lancelot, who is tortured by an inner weakness he cannot bear to name.

By the time White was through, he had brought the psychological depth only a novel can grant to Malory’s legendary figures. As a result, you might say that, before The Once and Future King, when people wrote about King Arthur they were responding to Malory. Afterward, they were responding to White.

The Once and Future King has had two beloved adaptations. White’s first volume, The Sword in the Stone (originally published as a separate novella), became the Disney animated film of the same name. It’s probably responsible for a generation of Americans being unable to tell the difference between the titular Sword in the Stone and Excalibur. Camelot became a sensation of its own, and inspired the sublime Monty Python parody Spamalot.

Beyond the White adaptations, all modern retellings of the Arthurian legend have had to reckon with White’s influence. That includes the queer YA Once & Future series, which reimagines Arthur as a teenage girl from the future. The other most famous Arthurian retelling of the twentieth century, Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon, positions itself as a feminist response to The Once and Future King. In some places, it matches White beat for beat.

Meanwhile, White’s ability to ground his magic and marvel in psychological realism leavened with playful anachronism would be deeply influential for a generation of modern fantasy writers. Not just Grossman but also Michael Moorcock, David Eddings, and Gregory Maguire have cited White as a major influence.

J. K. Rowling has said that White’s child King Arthur is Harry Potter’s “spiritual ancestor”; both amiable jocks who aren’t the brightest kids around, they’re neglected by their adult guardians and bullied by their peers, but redeemed by their selfless love for the people and the animals around them. (When Neil Gaiman was asked if Rowling had plagiarized Harry from his own similar character, Timothy Hunter, in The Books of Magic, he replied, “We were both just stealing from T. H. White: very straightforward.”) And there’s more than a touch of White’s absentminded, tragicomic Merlin in Rowling’s wise and quirky Dumbledore.

White’s influence made it to the movies, too. Star Wars is laced with King Arthur references, from Luke’s orphaned childhood to his relationship with the Merlin-like Obi-Wan Kenobi and Yoda. Some of those references come directly from Malory, but it’s White’s depiction of a late-stage Camelot turned decadent and failed by its heroes that gives us the decayed and destroyed Republic of the later Star Wars sequels. “We are the spark that will light the fire that will restore the Republic,” Poe Dameron says in The Last Jedi. He’s echoing White’s dying Arthur, who describes the legacy of the Camelot he’s built as a candle and passes it on to a young Thomas Malory. “I am giving you the candle now—you won’t let it out?” he asks.

White’s fingerprints are all over popular culture: the way we think about King Arthur, the way we write fantasy, what we think a fantasy story should look like. So, in a sense, we don’t have to wait for White to be considered one of the founding fathers of modern fantasy the way Tolkien and Lewis are. He already is one of fantasy’s great forefathers, whether we’re willing to grant him that honor or not.

11 CONSTANCE GRADY

CONSTANCE GRADY is a senior correspondent for Vox, where she writes about books, theater, and culture writ large.

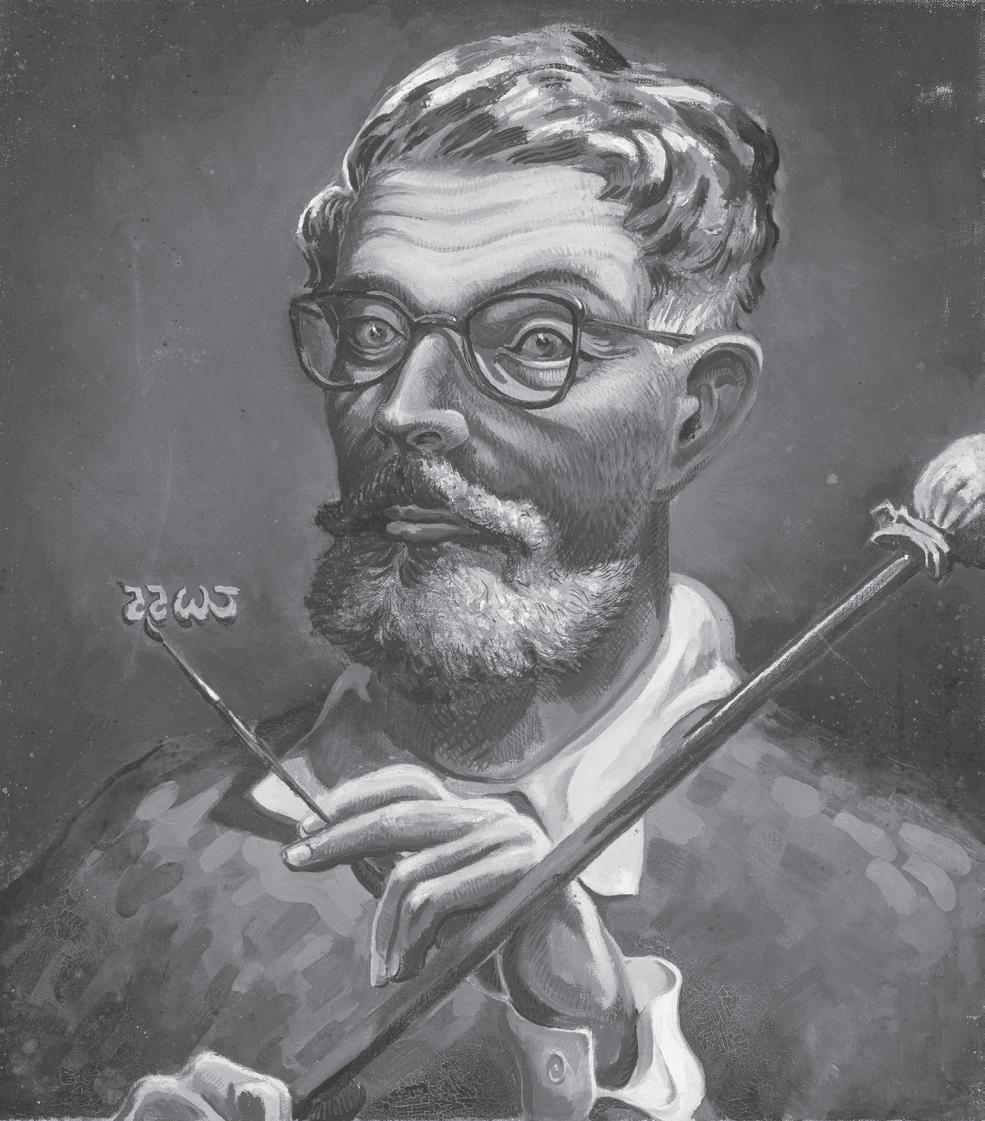

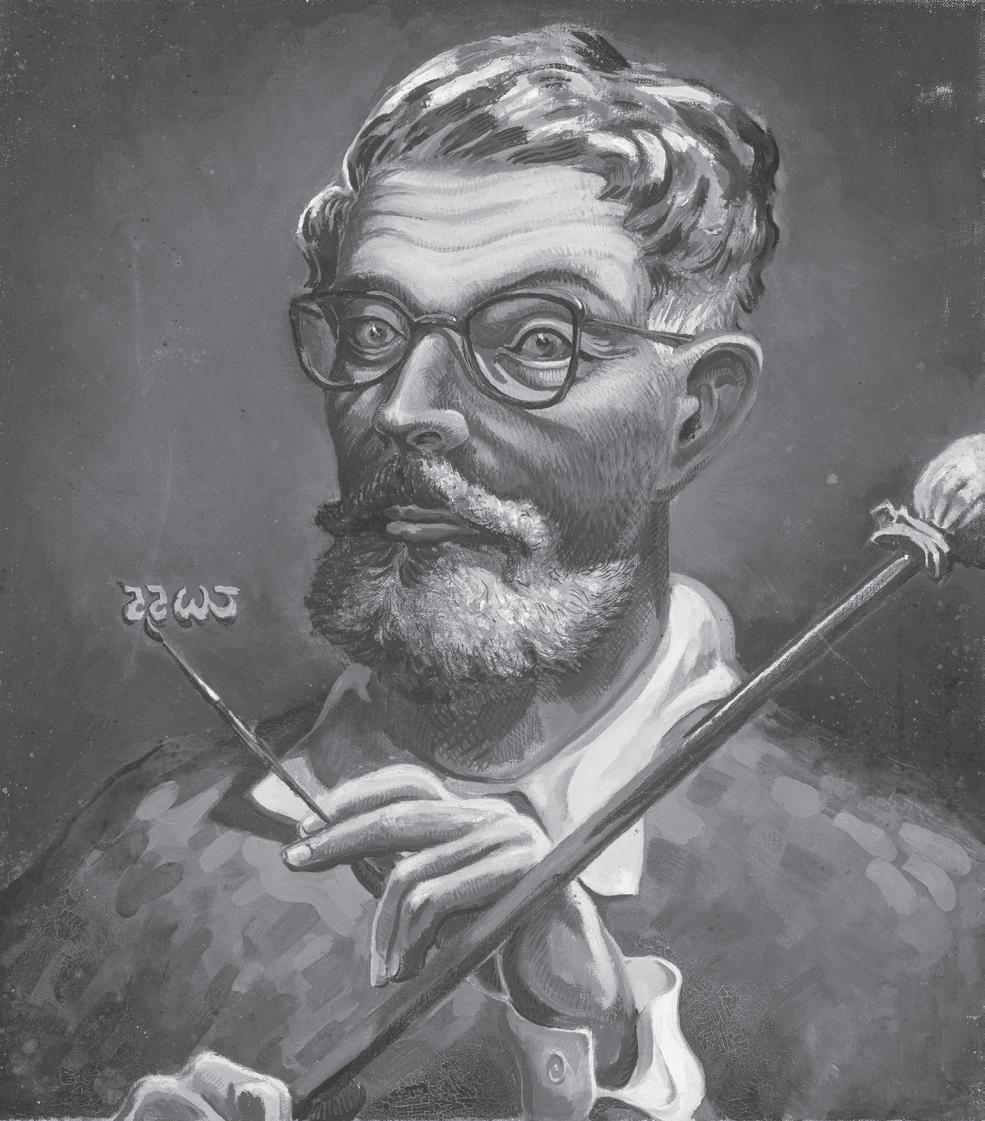

Background image: T. H. White © Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images. Above: Self-portrait, 1955, by T. H. White. Oil on canvas, T. H. (Terence Hanbury) White Art Collection, 69.20.1. Harry Ransom Center.

THE STREET WHERE I LIVE

ALAN JAY LERNER

AS I SAID WHEN I FIRST MENTIONED his name in this book, there will never be another Moss Hart, and no priest, minister, rabbi, or lama can convince me that taking him away at the age of fifty-seven was anything but senseless cruelty. I believe deeply there is a Divine Order and that life is without end, but at times Fate deals with it so frivolously that it seems without meaning.

But the tale of Camelot was not over.

On November 22, 1963, at Dealey Plaza, Dallas, Texas, the life of every human being on this planet was suddenly changed. The following week, Theodore H. White went to Hyannis Port and interviewed Jacqueline Kennedy for Life magazine. Teddy White, President Kennedy, and I had been classmates together in Harvard, and the President and I had been coeditors of the school yearbook at Choate. The interview occupied the two-page centerfold of Life and the second page began as follows:

another Camelot again. Once, the more I read of history the more bitter I got. For a while I thought history was something that bitter old men wrote. But then I realized history made Jack what he was. You must think of him as this little boy, sick so much of the time, reading in bed, reading history, reading the Knights of the Round Table, reading Marlborough. For Jack, history was full of heroes. And if it made him this way—if it made him see the heroes—maybe other little boys will see. Men are such a combination of good and bad. Jack had this hero idea of history, the idealistic view.’ “

But she came back to the idea that transfixed her: “ ‘Don’t let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment that was known as Camelot’—and it will never be that way again.”

“

‘When Jack quoted something, it was “usually classical,’ she said, ‘but I’m so ashamed of myself—all I keep thinking of is this line from a musical comedy.

“ ‘At night, before we’d go to sleep, Jack liked to play some records; and the song he loved most came at the very end of this record. The lines he loved to hear were: “Don’t let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment that was known as Camelot.” ’ “

She wanted to make sure that the point came clear and went on: “ ‘There’ll be great presidents again—and the Johnsons are wonderful, they’ve been wonderful to me—but there’ll never be

The interview then continued for another half-page and ended: “She said it is time people paid attention to the new president and the new first lady. But she does not want them to forget John F. Kennedy or read of him only in dusty or bitter histories: For one brief moment there was Camelot.”

Once the interview appeared, it immediately became a major news story. At the time, I had offices on the Lexington Avenue side of the Waldorf Astoria. Life magazine came out on Tuesday. Wednesday afternoon, I was crossing the lobby of the Waldorf on my way to the Park Avenue side of the hotel, when I passed the news-stand. The Journal-American, now defunct, had just been delivered. In headline letters above the title of the newspaper I saw:

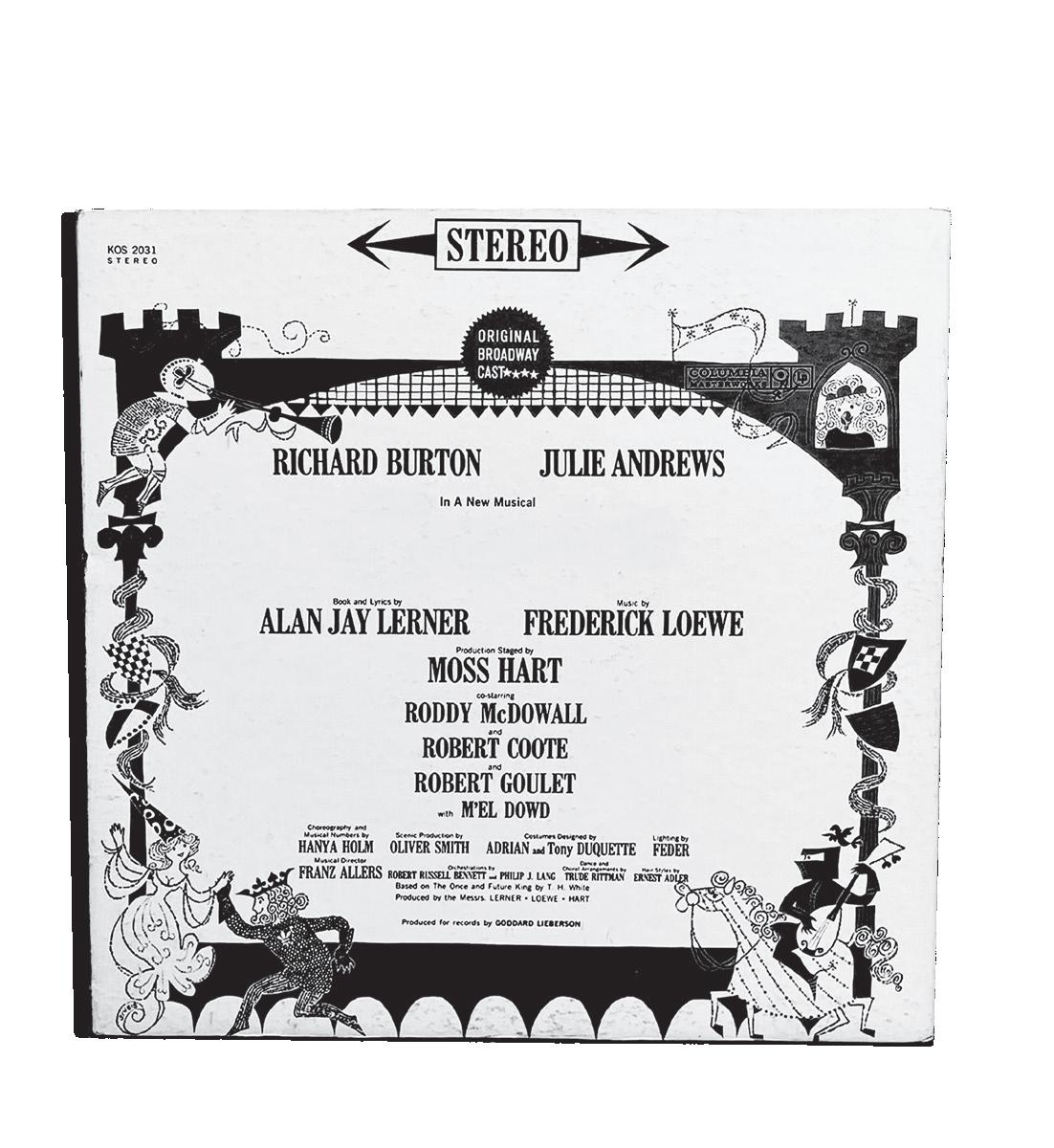

Above: The Knights of the Round Table engraving as a vinyl record © Chronicle/Alamy; LP sleeve and Side B label for the

EXCERPT FROM

Camelot 1960 musical soundtrack, courtesy of Masterworks Broadway, a label of Sony Music Entertainment.

Don’t let it be forgot That once there was a spot, For one brief shining moment That was known as Camelot.

The tragedy of the hour, the astonishment of seeing a lyric I had written in headlines, and the shock of recognition of a relationship between the two that extended far beyond the covers of one magazine, overloaded me with confused emotions. I was so dazed that I did not even buy the newspaper. I lived on Seventy-first Street at the time and I started to walk home. It was not until Eighty-third Street that I realized I had passed my house.

Camelot was then on the road, playing the Opera House in Chicago, a huge barn of a theater with over three thousand seats. I was told later what happened that night.

The theatre was packed. The verse quoted above is sung in the last scene. Louis Hayward was playing King Arthur. When he came to those lines, there was a sudden wail from the audience. It was not a muffled sob; it was a loud, almost primitive cry of pain. The play stopped, and for almost five minutes everyone in the theatre—on the stage, in the wings, in the pit, and in the audience—wept without restraint. Then the play continued.

Camelot had suddenly become the symbol of those thousand days when people the world over saw a bright new light of hope shining from the White House. Later, Samuel Eliot Morison wrote his monumental Oxford History of the American People, which ends with the death of President

Kennedy—the last page of the book is the music and lyrics of Camelot.

Ironically enough, also from that moment on the first act became the weak act and the second act, the strong one. God knows I would have preferred that history had not become my collaborator.

For myself, I have never been able to see a performance of Camelot again. I was in London when it was playing at Drury Lane, having arrived a few days after the producer, Jack Hylton, suddenly died. But I did not go the theatre. I could not.

ALAN JAY LERNER (1918-1986) was an American lyricist who created some of the most enduring works of musical theater, including My Fair Lady, Gigi, and Camelot Excerpted from The Street Where I Live: A Memoir by Alan Jay Lerner. Copyright © 1978 by Alan Jay Lerner. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

13 ALAN JAY LERNER

President John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy © Bettmann/Getty Images.

Don’t let it be forgot, That once there was a spot, For one brief shining moment That was known as Camelot.

Rearranging Electrons

the dungeon. I think that, from that moment on, I just kept wanting to write Man of La Mancha and Don Quixote in some fashion, no matter what it was, whether it was The West Wing or A Few Good Men, or, now, Camelot.

JG: It’s interesting that you didn’t go into writing musicals immediately. Is Camelot your first musical to be produced?

AS: It is my first musical of any kind.

JG: Did you ever go to straight plays when you were a kid?

In the fall of 2022, in the midst of his rewrites on the book for Camelot, our editors spoke to Aaron Sorkin, the Academy Award-and Emmywinning screenwriter, director, and playwright whose credits include A Few Good Men, The West Wing, The Newsroom, the stage adaptation of To Kill a Mockingbird, and a multitude of other iconic shows, films, and plays.

JOHN GUARE: One of my favorite things that I learned about you in my preparation for today was that you sold intermission drinks at the Palace Theatre. I sold intermission drinks and checked coats at the National Theatre when I was at Georgetown.

AARON SORKIN: We are brothers, then.

JG: Something most of our readers won’t know about you is that you went to Syracuse University to study musical theater writing, of all things. What was the first musical you saw that made you say, “That’s where I want to be”?

AS: Before my family moved to Westchester, which we did when I was eight years old, I was growing up in Manhattan, going to a private school in the village called the Little Red School House, and one of my classmates, when I was four or five, was the son of Herschel Bernardi, who had just taken over from Zero Mostel in Fiddler

on the Roof, and one Sunday we had a playdate. But there was some babysitter emergency, and whoever was looking after us had to park us backstage at the Imperial Theatre during Herschel Bernardi’s Sunday matinee. Now, my friend was used to being there—that was dad at the office. But I didn’t understand any of this. What I remember is just standing, frozen. Now I understand it was backstage, but back then I didn’t know what backstage was, and I was watching a guy in profile, singing “Miracle of Miracles” to an audience that I couldn’t see. I stood there watching, like I was watching somebody who had just stepped off a spaceship. I was mesmerized.

The first time I saw a musical and at least understood I’m sitting in a theater watching something onstage was Man of La Mancha. I remember sitting at the back of the balcony—those were the seats my family could afford. I saw the top of a bassoon just peeking out of the orchestra pit, and it gave me chills. I was somehow aware, at that moment, that there was something alive in this building. We were about to rearrange the electrons in this building somehow. And, sure enough, the scariest staircase in all of theater came down on chains, and the guys from the Spanish Inquisition came down into

AS: My parents took me to the theater a lot. When they were a young couple, they got into the theatergoing habit. It was more affordable when they were newlyweds, but they took me a lot, and often took me to plays that I was too young to understand. Like Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? when I was nine years old. I didn’t understand it, but I loved the sound of dialogue. It sounded like music to me. And I wanted to imitate that sound. As a result, what a line of dialogue sounds like is as important to me as what it means.

ALEXIS GARGAGLIANO: When you write, do you say the lines out loud?

AS: Yes, I do. I’m very physical when I’m writing. I do play all the parts. I’m talking out loud. I’m up and down from my desk, and I’m walking around—that is, if it’s going well. If it’s not going well, I’m just miserable, facedown on the couch. I’ve been asked if I get writer’s block—writer’s block is my default position.

JG: How old were you when you wrote A Few Good Men?

AS: When I started writing it I was twenty-four, and I was twenty-seven when it opened on Broadway.

JG: I read that it came out of a conversation with your sister, and I’ve always wanted to know what kind of research you did.

AS: A Few Good Men came out of a conversation with my sister at a family dinner. She had just graduated from law school and joined the Navy JAG corps and was involved with this case. I remember her saying, “You don’t know this, but the U.S. has a Navy base in Guantánamo Bay.” This was before

15 AARON SORKIN

AN INTERVIEW with AARON SORKIN

Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, 1964, by Salvador Dalí, watercolor with pen and ink © 2023 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-

Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society.

Photo: Private Collection, courtesy of Swann Auction Galleries/Bridgeman Images.

Guantánamo Bay was the world’s most famous prison. The government's attorneys were all majors and captains, very high-ranking officers. My sister, who had just been in the JAG corps for seven months, was a lieutenant, as were the other defense lawyers. And I said, “Why are all the defense lawyers junior officers and all the prosecutors senior officers with years of experience?” And she said something that would end up being a line in the play and the movie. She said, “Probably to make sure it never sees the inside of a courtroom.” And then, suddenly, I had a play that I wanted to write.

After that I got hold of transcripts from other court marshals and handbooks, things that I could grab some terminology from—the goal being that the audience thinks these guys know what they’re talking about.

JG: How long did it take you to write A Few Good Men, with all that research?

AS: I wrote it about twenty-five or thirty times. It took several years. This was my first play, so it was also me going to school. I was kind of learning how to write a play. While I’m very proud of it, and I had a great time doing it, it still feels a little like my high-school yearbook picture.

JG: How do you break down the spine of your lead character?

AS: I do worship at the altar of intention and obstacle. Somebody wants something, and something is standing in the way of them getting it. The tactics that your protagonist uses to overcome the obstacle, that’s the character. Whether they succeed or fail doesn’t really matter.

JG: I think you’re the only person I’ve ever heard of who had William Goldman

as a mentor, and I’m curious what you learned from someone who said that film writing is all action and no dialogue. What did you learn from Bill that makes him so important to you?

AS: I started learning from Bill Goldman before I even met him. He wrote a book that I strongly recommend to anyone who wants to be a screenwriter, and I would strongly recommend it to anyone who wants to be a dental hygienist. It’s just a fun read. It’s called Adventures in the Screen Trade. Before A Few Good Men went into rehearsal, and the script was kind of making its way around town, Bill Goldman read it and called me out of the blue and said, “You know, I’ve read your play, would you like to meet for lunch?” He took me under his wing, and until he passed away, just a few years ago, he was the first person I showed pages to, he was the person I talked to. JG: One of the things that you have become most famous for is pictures of worlds. What are you looking for when you’re setting out a world that you may not know very much about?

AS: Let’s assume we’re talking about nonfiction. At the beginning of the process, you don’t know what you’re looking for yet. You’re poking around with a flashlight and hoping you’ll trip over something that will give you some questions to ask. I like a place to feel real—but there’s a difference, from a dramatist’s standpoint, between truth and accuracy. Accuracy is what a journalist needs. I’ll give you a tiny example. Mark Zuckerberg was liveblogging on a Tuesday night when he was a sophomore at Harvard, because he had just had a date that didn’t go well and he was very angry, and he was drinking—and drinking to get drunk. I know this, because he tells us this in the live blog. So I imagined the date, and that’s what we open The Social Network with. Then we go to his dorm room, where he begins drinking and liveblogging and hacking into the student directories, or Facebooks, as they call them at Harvard, grabbing pictures of women students and using them to set up a Web site he called FaceMash, which is what they call a hot or not Web

site that became so popular in just a matter of a few hours in the middle of the night on a Tuesday that it crashed the school’s whole computer system. Now, here’s my point. The way I started the scene in the script was we’re on his computer screen. He walks through the frame, powers up his computer, comes back in the frame, puts a glass down. Ice goes in the glass, vodka goes in the glass, orange juice goes in the glass—all while we’re hearing the voice-over of what he’s blogging. About two weeks before we started shooting, we found out that he was actually drinking beer that night. Beck’s, to be exact. And David Fincher, our director, whom I love, said, “Aaron, you know we’ve got to change it to beer, we’ve got to change it to Beck’s.” I urged David not to do that. It’s not just that the screwdriver is more visually interesting to make than opening a beer. It’s that having a beer doesn’t necessarily read to the audience as drinking to get drunk—that could just be a college kid who’s thirsty on a Tuesday night. What was important was that he was drunk. What was important was that he was drinking to get drunk. We needed that. I lost the argument, by the way—it’s a beer in the movie. And that was accurate. But what would have been more truthful was the vodka and orange juice. AG: What is it like to work on Camelot and be able to live in the truth part and not have to worry so much about the accuracy?

AS: Well, you’ve brought up an interesting thing. When Bart asked me if I wanted to write a new book for Camelot, I answered yes about as fast as a person could say yes. I knew that one of the things that I wanted to do was tell the story without any supernatural elements. The legend of King Arthur has been around for hundreds of years, centuries, and there are all kinds of tellings of the story, but in all of those tellings, as far as I know, there is magic involved. Merlin is a magician—he can turn Arthur into a hawk who flies above and see things. Morgan le Fay can build an invisible wall around Arthur to trap him in the forest. It’s a fairy

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW 16

I JUST KEPT WANTING TO WRITE MAN OF LA MANCHA AND DON QUIXOTE IN SOME FASHION,NO MATTER WHAT IT WAS, WHETHER IT WAS THE WEST WING OR A FEW GOOD MEN, OR, NOW, CAMELOT.

tale. And it’s a really good fairy tale, but I thought it might be interesting to see how this story lands if it feels real, if it feels like it’s taking place in the world that we’re living in. In fact, Guenevere debunks the whole origin story of Arthur’s being able to take a sword out of a stone because he was the chosen one. She says that 9,999 people loosened it for him. I wanted them to be humans. Because, as sad as the end of the story may be, it is also meant to be inspirational—look what humans are capable of if we reach high. This is what I mean by I’ll try to write Don Quixote as many times as I can get away with.

AG: When I first heard that you were doing this show, it didn’t automatically make sense to me—Aaron Sorkin writing a musical set in a mythological place in the Middle Ages—but when I read the script, with its exploration of democracy and idealism, it seemed quintessentially Sorkin. So now that we’re speaking, the

through line from Man of La Mancha to A Few Good Men to The Newsroom to Camelot feels so clear. Once the magic is stripped away, we are really talking about humanity and progress. AS: If magic is involved, I feel like the stakes aren’t as high. I found it exciting to turn a magical character into someone real. For instance, Morgan le Fay, Mordred’s mother. Traditionally, she’s magical and can do bad things to Arthur, but it also turns out, if you do some research, that she’s a scientist at a time when science hadn’t quite been invented yet. People who were scientists were just scary; they were like conspiracy theorists. So I thought

it would be fun if she had no magical powers, but was a scientist, and also an opium addict and an alcoholic, so she talks through a kind of stoned haze about the new century, and how science is going to crack the world wide open.

Also, I should mention that we’re not finished with the script yet. Well, for me scripts are never finished; they’re confiscated.

JG: By whom?

AS: By the director or the producer— somebody comes in and says, “Pencils down.” It’s either because the critics are coming, so we’ve got to freeze the show, or we’ve got to start shooting now.

JG: James Joyce would say that manuscripts were never finished, they were abandoned. But I like confiscated.

AS: I take a slightly more optimistic view.

JG: Another Lincoln Center playwright, Tom Stoppard, who is famous for writing about worlds outside himself, is at this point in his life writing plays that face up to something in his own life. You are one of the few playwrights who have not dipped into his past. Is there a Glass Menagerie waiting inside you somewhere?

AS: I’ll answer that. But first I’ll say really good weekend golfers look at professional golfers and say, “Those guys are playing a different game.” Professional golfers look at Tiger Woods in his prime and say, “That guy is playing a different game.” Tom Stoppard is playing a different game. Okay. As a playwright, he and Tony Kushner are simply in a league of their own. They are both Mozart living today. When we were rehearsing To Kill a Mockingbird, which we were doing at Lincoln Center, in the doorway, one day, came Tom Stoppard, who wanted to meet me and wish me luck. He had a play rehearsing down the hall. This guy that I worship, and I’m terrified of, was being really friendly to me. And

Aaron Sorkin © Miller Mobley / AUGUST

IF MAGIC IS INVOLVED, I FEEL LIKE THE STAKES AREN’T AS HIGH. I FOUND IT EXCITING TO TURN A MAGICAL CHARACTER INTO SOMEONE REAL.

then the first day of the first workshop of Camelot, Tom Stoppard shows up like Marley’s ghost. So, if nothing else, I kind of live to not embarrass myself in front of Tom Stoppard. Now, to answer your question, I am aware—and I’ve been aware for a long time—that I don’t write autobiographically, or don’t consciously write autobiographically, and I wonder if that’s a weakness of mine. Why can’t I get in touch with the kind of blood that’s running? Do I just not have an interesting story? I don’t know the answer. But you asked me is there a Glass Menagerie in my future—I hope so, because a lot of times when a playwright does that he ends up writing some of his best work. I think that my only connection to autobiography is that the protagonists that I write are my father. He’s no longer alive, but my father, like Don Quixote, always lived with one foot in a different century. He was just a good man, and a very intelligent man, a lawyer. Goodness and civility were always important to him.

JG: He sounds like Atticus Finch.

AS: Atticus was one of his favorite characters. Yes, he’s like Atticus Finch. He’s like Jed Bartlet. And, in this iteration of Camelot, King Arthur. AG: Is he the reason that you’re such a Romantic?

AS: Yes, I’m happy to give all the credit to my father. Romantic, idealistic. And that’s another reason the whole idea of Camelot is a good fit. I tend to write romantically and idealistically.

LOVE & POLITICS

KATE ANDERSEN BROWER PRESIDENTIAL PARTNERSHIPS ARE FORGED decades before couples step onto the national stage. By the time we meet them, they have already made countless sacrifices and weathered many storms together. Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s affair with Eleanor’s social secretary, Lucy Mercer, began almost two decades before he became President. Ultimately, the betrayal gave Eleanor the space to become the most consequential First Lady of the twentieth century. Hillary Clinton tolerated her husband’s affair with the cabaret singer Gennifer Flowers while he was the governor of Arkansas because she was playing the long game. But this negotiation between what Hillary Clinton was willing to tolerate in her marriage in order to reach the White House may be less scandalous and, in some ways, more profound than it appears. For First Ladies, their sacrifices can even mean giving up some of their own sense of self for their husbands.

One of the most famous power couples in Western literature is King Arthur and Guenevere. Of course, their match began as a political act, but their particular brand of love brings Camelot, a symbol of peace and hope, to life. With great power comes great pressure, though, and they must decide how much of themselves they are willing to sacrifice in order to preserve Camelot. In the end, it is their very relationship that upends the utopia they created.

It is said that politics is all about compromise, and in political marriages those compromises come with high stakes and they play out on a public stage. Jackie Kennedy famously used

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW 18

Opposite page (top right): First Lady Betty Ford dances on the Cabinet Room table on the day before departing the White House. January 19, 1977 © David Hume Kennerly/Everett Collection.

Camelot to create the illusion of a brief period of harmony in the country made possible by her husband. But she, more than anyone, knew the sacrifices demanded of the First Lady in order to create that illusion. Decades later, Michelle Obama was schooled in the demands of a Presidential marriage. Michelle, who had graduated from Princeton, earned a law degree from Harvard, and became, first, a corporate lawyer, and was an executive at the University of Chicago Medical Center, when she was asked to examine a video of herself to find out why she had made people so mad. Her husband was the only person on earth she would even consider going through that humiliating exercise for.

It was during Barack Obama’s 2008 Presidential campaign that Obama’s adviser David Axelrod asked Michelle to watch herself giving a speech on the campaign trail so that she could see why she was being perceived as “angry.” Of course, she had never thought of herself in that way, and she was genuinely hurt that her offhand remark, when she said, “For the first time in my adult life, I’m proud of my country,” had caused such an uproar. Michelle knew all too well that the country she loves has a long history of labeling Black women that way. After she and her husband became the first Black President and First Lady, they celebrated what their election meant for the country, but as

a couple they worried about being in uncharted territory.

“I had lived with an awareness that we ourselves were a provocation,” Michelle wrote in her memoir, Becoming. But the idea that her very mannerisms, her way of speaking and being, could hurt the man she loved cut her to her core. Add to that the inherent pressures of raising two young children in the spotlight—Sasha was seven, and the youngest person to live in the White House since John F. Kennedy, Jr., and Malia was ten—and you have a tinderbox of resentment to work through. An ongoing conflict between love and duty. For Michelle, that meant giving up a career that was a part of her identity in order to focus on their children as she and her husband carried the heavy burden of being “firsts.”

The match of [King Arthur and Guenevere] began as a political act, but their particular brand of love brings Camelot, a symbol of peace and hope, to life.

Left: President Barack Obama unexpectedly runs into Michelle on her birthday in the basement of the White House, January 17, 2012. © Christopher Morris/VII/Redux.

Barack and Michelle Obama . . . believed in the possibility of a more perfect nation, and in their o wn imperfect human way they made their marriage work while reaching for Camelot.

In some ways, Barack and Michelle Obama represent Arthur and Guenevere 2.0. They believed in the possibility of a more perfect nation, and in their own imperfect human way they made their marriage work while reaching for Camelot. F.D.R. and Eleanor also shared a strong belief in the values of democracy and progress; their great love and affection for each other became secondary to their passion for social reform. When F.D.R. was the assistant secretary of the Navy, Eleanor would take their five children away from Washington to their Campobello retreat, off the coast of Maine, during the summer. While she was out of town, his relationship with Mercer grew. Historians say the affair likely began sometime during 1916, but it was in 1919 that Eleanor discovered the love letters, when she was unpacking her pneumonia-stricken husband’s luggage. She was devastated. She burned them and offered her husband a divorce. He refused, knowing that it could ruin his political career.

Eleanor’s granddaughter, Nina Gibson Roosevelt, recalled how it changed their relationship. “I can remember her saying, ‘You forgive, you don’t necessarily forget, but you can forgive.’ From then on, their marriage became a partnership in a way that freed her to become the woman she became. So through adversity sometimes we rise and become things that we never thought we might become.” On April 12, 1945, President Franklin Roosevelt died at his cottage in Warm Springs, with Mercer by his side. Eleanor was at work back in Washington, where she had delivered a speech that afternoon. But it was through her work as First Lady that she found herself, and through an intimate relationship she shared with the journalist Lorena Hickok. Her husband’s infidelity gave her the freedom to pursue her own passions.

Every Presidential couple tries to reconcile the feelings that they should somehow make everyone else in the country happy while also fulfilling each other’s needs. An impossible task, to be sure. In a famous episode of 60 Minutes in 1975, during an interview, First Lady Betty Ford shocked the nation simply by being honest. She acknowledged that all of her children had experimented with marijuana, and she said that if she were a teenager she would probably try it herself. She also admitted to seeing a psychiatrist, and she revealed that she was prochoice. None of this was considered proper behavior for a First Lady. One man actually wrote, aghast and without a trace of irony, “You are, because of the position your husband has assumed, expected and officially required to be PERFECT.” What his definition of “perfect” was is anyone’s guess.

The weight of criticism and the toll it takes on a Presidential marriage is difficult to calculate—it’s never possible to really get inside a relationship— but since leaving office in 2017 the Obamas have pulled back the curtain just a few inches.

“During the time we were there, Michelle felt this underlying tension,” the former President wrote in his memoir A Promised Land. “The pressure, stress, of needing to get everything right, to be ‘on’ at every moment. . . . There were times where I think she was frustrated or sad or angry but knew that I had Afghanistan or the financial crisis to worry about, so she would tamp it down.” In short, he simply did not have the bandwidth to handle her needs.

Compared with the Clintons and the Trumps, the Obamas’ marriage and its trials and tribulations might seem tame, but that is what makes it so compelling. They represent the power dynamic playing out in many relationships, but on a grand stage and under outsized pressure. They had to decide whether their needs rose to the level of

being addressed amid the immense strain of the positions they held in the White House. The President’s role is obvious, but the First Lady’s is not—a reality that, ironically, only adds to the stress of the position. As Presidential partner, she is everything and nothing all at once. She has to define the job for herself. Nancy Reagan considered it within her purview to sniff out and fire staff members whom she suspected of being disloyal to her husband. Ronald Reagan desperately wanted everyone to like him, and, of course, everyone likes to be liked, but Nancy was willing to sacrifice that admiration to be her husband’s ultimate protector. And she paid the price: in a December 1981 Gallup poll, she had the highest disapproval rating—twenty-five percent—of any modern First Lady.

Most First Ladies avoid total honesty while they’re in the White House, but they’re liberated

20 LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW

Every Presidential couple tries to reconcile the feelings that they should somehow make everyone else in the country happy while also fulfilling each other’s needs.

after they leave. (Nancy Reagan’s My Turn is a must-read for anyone interested in First Ladies.) In her post-White House memoir, Michelle Obama was similarly startlingly honest. She wrote about her and her husband’s struggles getting pregnant, then suffering a miscarriage, and she revealed that both Malia and Sasha were conceived through in-vitro fertilization. She had to administer the shots required in the process herself while her husband was away serving in the state legislature in Springfield, Illinois. Well before the White House, they had sought couples counseling that saved their marriage during a time when she worried that his political career “would end up steam-rolling our every need.” So it was during those early years that the power dynamic between them began to shift, and her career began to take a backseat to his political ambitions. It was a bargain they made in order to preserve what they had.

Inside the White House, when a President talks about wanting his staff to achieve a work-life balance, the joke is always that he’s referring to his home life and no one else’s. Staff members are

expected to miss their own children’s birthday parties and doctor’s visits when duty calls. And, while Michelle made the case that her husband was home more often as President than he had been when he commuted to Springfield, Illinois, or to Washington, D.C., there were still many things that he missed. But dinners in the second-floor residence, a sacred private space for First Families, were inviolable. So much so that even Michelle’s mother, Marian Robinson, who moved into a small suite on the third floor to help care for her granddaughters, wasn’t invited.

But you can have only so much privacy when you live above the store. That was obvious when the President’s Daily Brief (or, as Michelle called it, “The Death, Destruction and Horrible Things Book”) was presented at the breakfast table every morning: a heavy thump that rattled the coffee cups.

There is an obvious paradox that the Obamas negotiated every day of their eight years in the White House: that of maintaining a private life in the most high-profile positions imaginable while also recognizing how endearing their domestic life was to much of the country. Michelle grew up on Chicago’s South Side, and keeping it real was one of her superpowers; it was why she eventually became such a sought-after campaigner, earning the nickname “the closer” from Obama aides. Her mom-next-door persona included sometimes making fun of her husband’s morning breath and his body odor. Some people thought this unbecoming of a First Lady, but most of the country seemed to enjoy her candor and her ability to take her husband down a peg or two when she felt that it was necessary.

Lady Bird Johnson considered her role to be “balm, sustainer, and sometime critic for my husband.” She even gave L.B.J. “critiques”—if she thought he was doing “too much looking down” during a speech, or sounded breathless, she told him so. Sometimes she graded him on his performance. One speech earned “a good B+.” Joseph Califano, a close Johnson adviser, put it well when he said, “She was more important to what he did in the White House than any staffer.” L.B.J., who could be cruel to his wife, actually appreciated her input. He needed her opinion, because he must have known that, like every President, he was surrounded by yes men. And it made her feel like a true partner.

In 2022, when Barack Obama was asked about how to navigate political opposition at the Copenhagen Democracy Summit, he warned leaders, “Sometimes we get filled up in our own self-righteousness. We’re so convinced that we’re

21 KATE ANDRESON BROWER

President Reagan saying goodbye to Nancy Reagan at Andrews Air Force base, November 17, 1984. Courtesy of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.

right that we forget what we are right about.” But what applies to politics also applies to marriage: Obama needed to be reminded, from time to time, that at home he was a father and a husband first, and not the leader of the Free World. His wife was his grounding influence.

The Obamas now have a renewed sense of relative privacy, and multimillion-dollar brandbuilding deals. Their combined influence goes well beyond politics; critics refer to their postPresidential life as “Obama, Inc.”

Growing together in a relationship is always a challenge, but after a couple has made it to the stratosphere of American political power—he could not have become President without her by his side—the obligation to fulfill a duty to the position and to oneself shifts dramatically. The Obamas can finally exhale. Sure, more attention is given to their courting of multimillion-dollar donors to fund the Obama Presidential Center, and the global media blitzes to promote their respective blockbuster memoirs, but what is even more interesting is this: they now have the chance to rebalance a relationship that has been out of whack for too long.

Since leaving the White House, they have become more themselves and less guarded. The former President directly campaigns for Democratic candidates, and the former First Lady, who has long expressed disdain for the nastiness of politics, devotes her time to her nonprofit When We All Vote, which seeks to encourage voter registration. During their portrait unveilings

at the White House, Obama made this plea for understanding: “What you realize when you’re sitting behind that desk, and what I want people to remember about Michelle and me, is that Presidents and First Ladies are human beings like everyone else. We have our gifts. We have our flaws. You’ve all experienced mine. We have good days and bad days. We feel the same joy and sadness, frustration and hope.”

It is often First Ladies like Michelle Obama and Betty Ford, women who feel free to say what’s on their minds because they will never run for office themselves, who are most popular in any White House. The overtly political ones, à la Hillary Clinton, are the most polarizing. But while women like Michelle and Betty did not want to enter politics as candidates, they recognized that, like Guenevere, they could serve the greater good by being the partners their husbands needed.

In her memoir, Michelle Obama described the profound moment when her husband asked her to come to his side in the middle of the day. It resonated with her because it was a recognition that their marriage was the most important thing in his life, and the carnage of that particular day made him want to hold her close. The day was December 14, 2012, and twenty first graders and six adult staff members had been killed by a gunman in Newtown, Connecticut.

“My husband needed me,” Michelle later wrote. “This would be the only time in eight years that he’d request my presence in the middle of a workday, the two of us rearranging our schedules to be alone together for a moment of dim comfort.”

No matter how heavy the burden of the Presidency, there was an undeniable emotional, almost magnetic pull, they had to each other in their darkest moments. Human nature, and the need for love, acceptance, and empathy, triumphs, even inside the White House, where the stakes are at their highest.

KATE ANDERSEN BROWER’s latest book, Elizabeth Taylor: The Grit & Glamour of an Icon, is the first authorized biography of the actress. Brower is the author of the No. 1 New York Times bestseller The Residence and of First Women, also a New York Times bestseller, as well as Team of Five, First in Line, and the children’s book Exploring the White House The Residence is being made into a television series produced by Shonda Rhimes for Netflix.

22 LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW

Former First Lady Anna Eleanor Roosevelt, waving her hand during the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, California, July 1960 © Ed Clark/The LIFE Picture Collection/ Shutterstock.

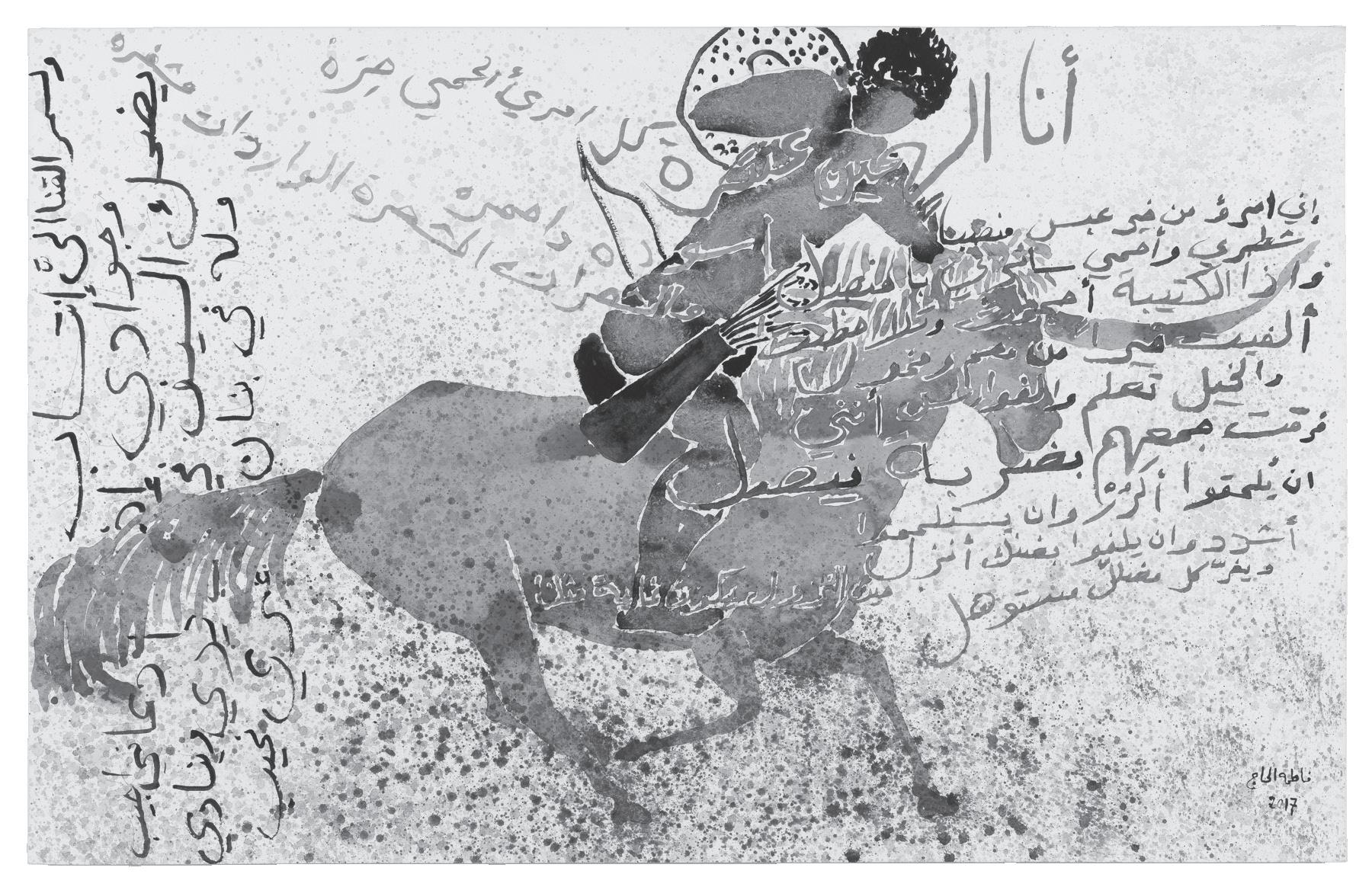

CHIVALRY , for most of us in the West drums up images of knights— specifically, white knights on horses, at round tables, or on bended knee before a woman. But this idea of chivalry arrived in Western Europe by way of the Iberian Peninsula, where it had been brought by the Arabs, who had been celebrating courtly love, gallantry, generosity of spirit, and chivalry since at least the early sixth century AD. One of the most celebrated of these warrior poets was Antarah ibn Shaddad, a Black man born into slavery to an Ethiopian mother and an Arab father. He was a fierce warrior who gained his freedom, remained devoted to his one true love, and became one of the most celebrated poets in Arabic literature.

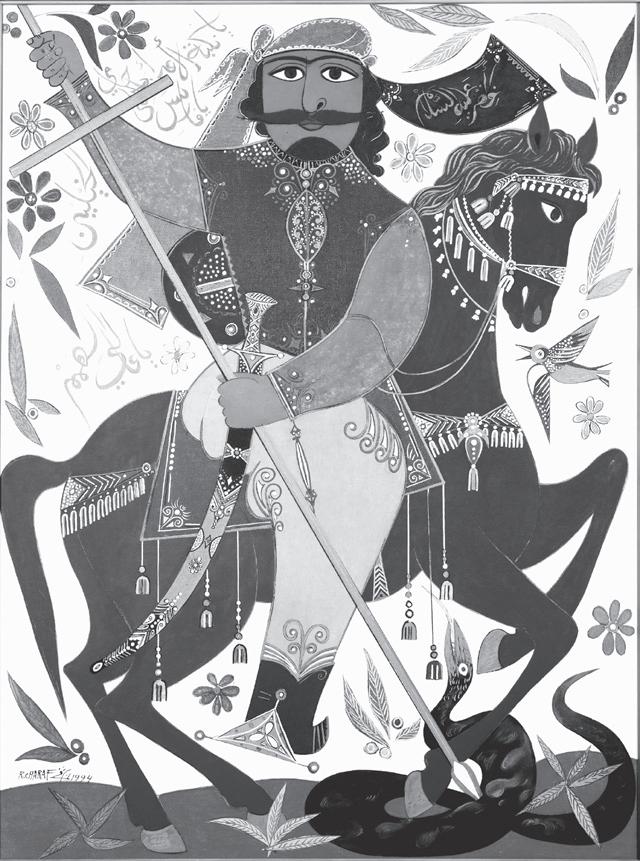

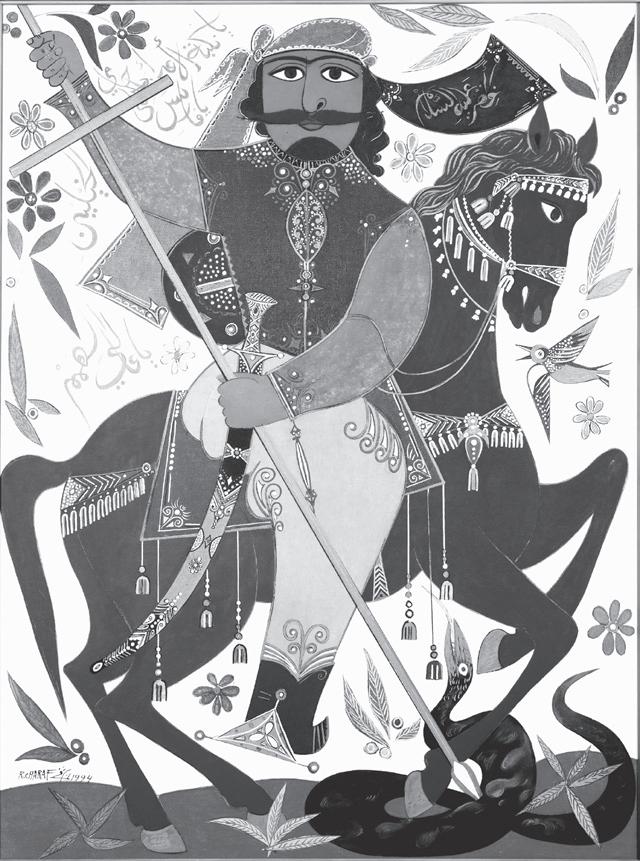

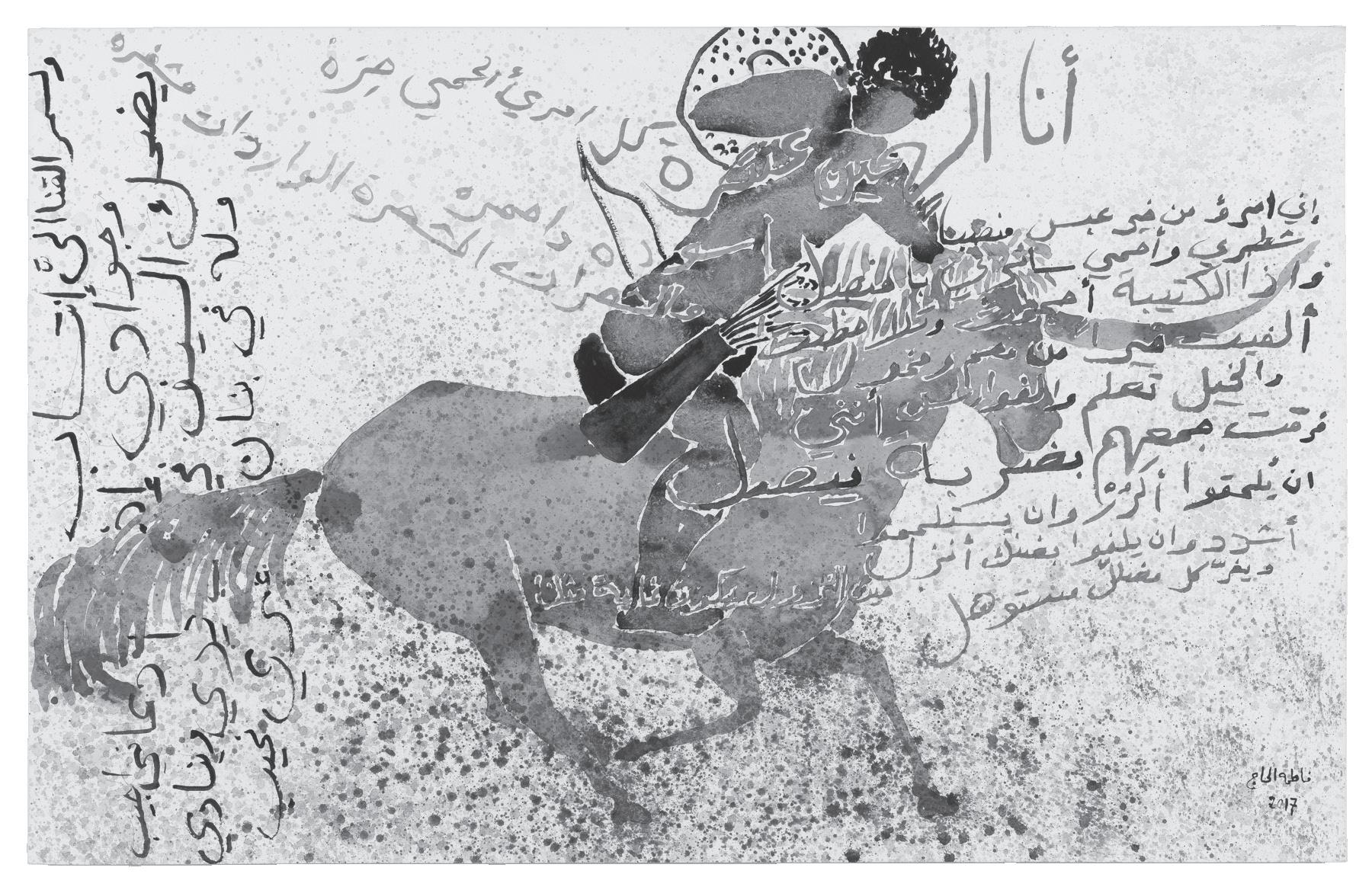

From top: Abla and the Moon, 2019, by Boutros Al-Maari. Acrylic on canvas © Boutros Al-Maari. Courtesy Galerie Claude Lemand, Paris; Antarah, 2017, by Fatima El Hajj. Acrylic on paper. Courtesy of the artist; Horseman, 1994, by Rafic Charaf, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Rafic Charaf Family Collection.

ANTARAH IBN SHADDAD, TRANSLATED BY JAMES MONTGOMERY

From top: Abla and the Moon, 2019, by Boutros Al-Maari. Acrylic on canvas © Boutros Al-Maari. Courtesy Galerie Claude Lemand, Paris; Antarah, 2017, by Fatima El Hajj. Acrylic on paper. Courtesy of the artist; Horseman, 1994, by Rafic Charaf, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Rafic Charaf Family Collection.

ANTARAH IBN SHADDAD, TRANSLATED BY JAMES MONTGOMERY

Fools may mock my blackness! but without night there’s no day!

Lincoln Center Theater Review

Vivian Beaumont Theater, Inc.

150 West 65 Street

New York, New York 10023

NON PROFIT ORG U.S. POSTAGE PAID NEW YORK, NY PERMIT NO. 9313

Top row (left to right): Ava Gardner taking a break while filming, Knights of the Round Table, 1953 © PictureLux/The Hollywood Archive/Alamy; Camelot street sign © eyecrave productions/iStock/ Getty Images; Camelot Castle music box.

Middle row (left to right): Reproduction of original signpost prop from Monty Python and the Holy Grail; Camelot Music store t-shirt courtesy of oldschoolshirts.com; Camelot Casino gaming token; Camelot, 1960, original cast rehearsal with Julie Andrews. Photo by Friedman-Abeles © The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Bottom row (left to right): King Arthur ceramic Toby mug; Camelot board game box c. 1930s; Sir Lancelot and Guenevere Madame Alexander dolls; Camelot Casino gaming token.

Top row (left to right): Ava Gardner taking a break while filming, Knights of the Round Table, 1953 © PictureLux/The Hollywood Archive/Alamy; Camelot street sign © eyecrave productions/iStock/ Getty Images; Camelot Castle music box.

Middle row (left to right): Reproduction of original signpost prop from Monty Python and the Holy Grail; Camelot Music store t-shirt courtesy of oldschoolshirts.com; Camelot Casino gaming token; Camelot, 1960, original cast rehearsal with Julie Andrews. Photo by Friedman-Abeles © The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Bottom row (left to right): King Arthur ceramic Toby mug; Camelot board game box c. 1930s; Sir Lancelot and Guenevere Madame Alexander dolls; Camelot Casino gaming token.

From top: Abla and the Moon, 2019, by Boutros Al-Maari. Acrylic on canvas © Boutros Al-Maari. Courtesy Galerie Claude Lemand, Paris; Antarah, 2017, by Fatima El Hajj. Acrylic on paper. Courtesy of the artist; Horseman, 1994, by Rafic Charaf, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Rafic Charaf Family Collection.

ANTARAH IBN SHADDAD, TRANSLATED BY JAMES MONTGOMERY

From top: Abla and the Moon, 2019, by Boutros Al-Maari. Acrylic on canvas © Boutros Al-Maari. Courtesy Galerie Claude Lemand, Paris; Antarah, 2017, by Fatima El Hajj. Acrylic on paper. Courtesy of the artist; Horseman, 1994, by Rafic Charaf, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Rafic Charaf Family Collection.

ANTARAH IBN SHADDAD, TRANSLATED BY JAMES MONTGOMERY