10 minute read

Cover Story

From Chasing to Solving Labor Scarcity

Part I: Current Automation Adoption by the US Nursery Industry

Advertisement

By Amy Fulcher¹, Alicia Rihn¹, Laura Warner², Anthony LeBude³, Margarita Velandia¹, Natalie Bumgarner¹ & Susan Schexnayder¹

¹ University of Tennessee, ²University of Florida, ³North Carolina State University

During exit interviews of Tennessee Master Nursery Producer Program, I ask graduates “How is the labor situation at your nursery?” I hear many comments like the following:

“Terrible. We can’t get no help. We’ve got about ½ done what we should have by this time of year. Have 5 guys; I need 10 or 15. It’s been really tough this year. This is the toughest year since I’ve been in business.”

“100% H-2A now, plus one domestic laborer in the winter. Prior to H-2A, one person at work but 8 people on payroll.”

“It is begging. There are no workers. It doesn’t matter what you pay them, no one wants to work. For all nurseries this is our next huge problem. Nursery stock price hasn’t gone up. Same price it was 15 years ago. Liners and baskets went up. Fuel went up. Locked in fertilizer. Prepay or else $800 pallet (if you can get it). Probably will have to do it [H-2A].”

“Not 10 people standing in line to work at our nursery anymore.”

In the U.S., labor costs to produce specialty crops represent nearly 40% of total cash expenses; more even than dairy operations. Across all specialty crops, nursery crops are very manual labor-intensive, which makes the nursery industry particularly vulnerable to labor scarcity. Challenges of hiring sufficient employees are made worse by limited availability of a combined domestic and foreign labor workforce that is increasingly insufficient to meet today’s nursery labor demands. There is no indication that this situation will improve. Across the U.S., nursery producers are exploring automation and other technologies to address labor concerns.

A three-part article series was developed to aid the Tennessee nursery industry as they navigate automation options, automation trends, and the perceived benefits and outcomes of automation, with the goal of helping to prepare nurseries for an increasingly labor-scarce future. In this issue of Tennessee Greentimes, we present Part I, “Current Automation Adoption” that describes growers’ use of a range of container- and field-production automation technologies. In future issues of the magazine, we will share Part II “Advances in Automation within Task,” in which we evaluate the portion of a given task that is automated and compare that to previous automation levels. In Part III “Outcomes from Adopting Automation and Perceived Helpfulness Analysis,” we will present nursery producer perceptions of helpfulness that they associate with specific pieces of automation as well as examine outcomes growers anticipate from using automation.

The information presented in this series is from the Labor, Efficiency, Automation, Production (LEAP) Nursery Labor and Automation Survey that was conducted in 2021 and asked respondents about practices that they used in 2020. The survey was sent to 1,225 employees at a manager or higher position at U.S. nurseries. We compare these national survey results with results from a survey conducted by phone interview in the southeastern U.S. over a period of several years (Posadas, 2018), which for simplicity we refer to here as having been conducted in 2006, and an abbreviated data set from that survey (Coker et al., 2010, 2015). Averages (means) and standard deviations are presented. Mean separation was conducted at a significance level of alpha = 0.05.

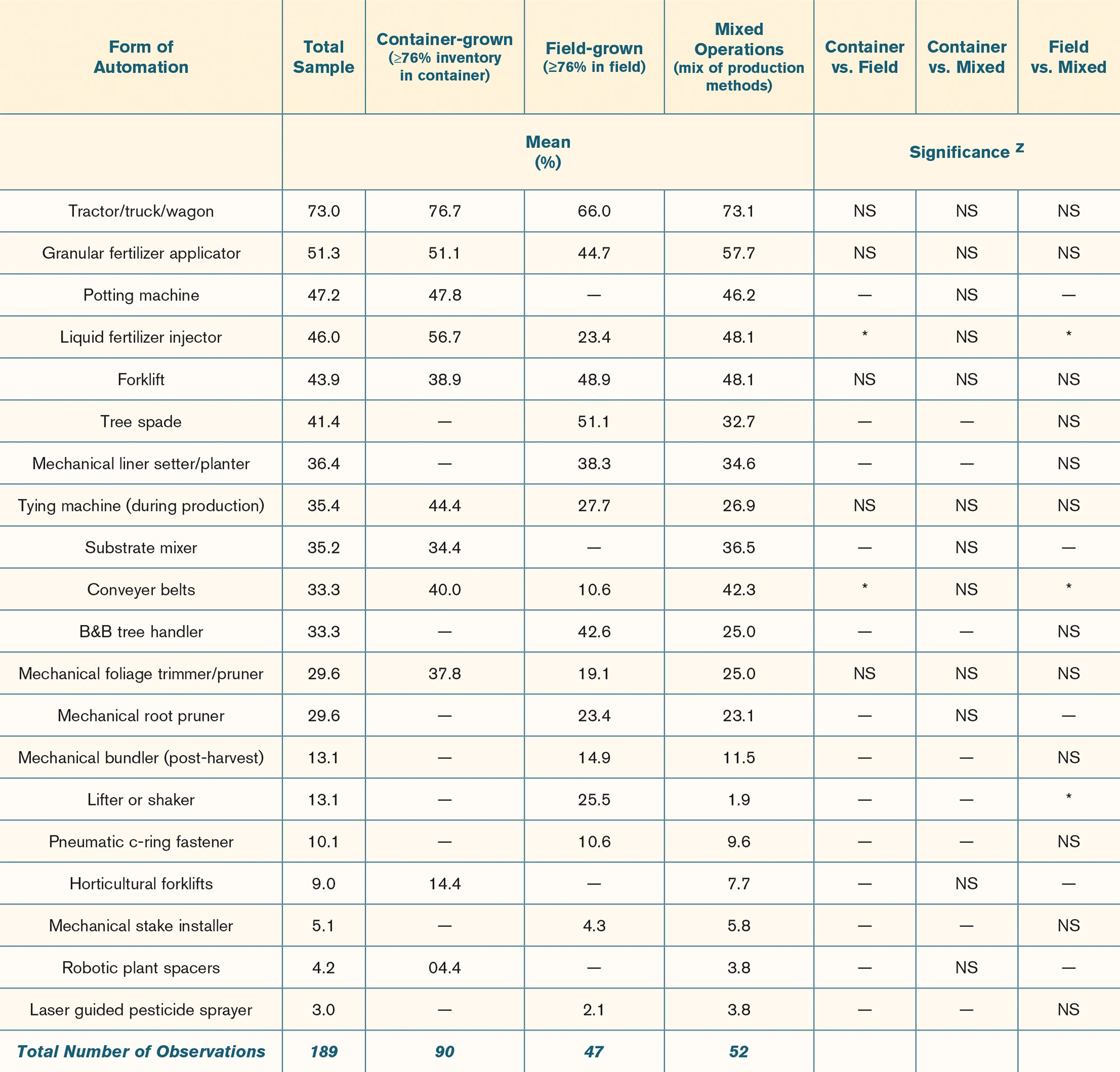

Nurseries are adopting automation to help with a range of container and field production tasks (Table 1). Current use of automation technology was highest for use of trucks or tractors with wagons (73.0%) (Fig. 1). Granular fertilizer applicators, potting machines, liquid fertilizer applicators, forklifts, and tree spades were used by roughly 40 – 50% of survey respondents. Mechanical liner setter/planters, tying machines, substrate mixers, conveyer belts, B&B tree handlers, mechanical foliage trimmer/ pruners, and mechanical root pruners are in use at approximately 28 – 35% of responding nurseries. Less than 20% of nurseries responding to the survey are using mechanical bundlers (post-harvest), lifters or shakers, pneumatic c-ring fasteners, horticultural forklifts (Fig. 2), mechanical stake installers, robotic plant spacers, or laserguided spray technology.

Figure 1. Wagons are widely used to transport plants within nurseries.

Figure 2. A horticultural forklift can be used to move plants and impose the desired spacing when they are placed in the production block.

The type of production system impacted whether certain automated nursery technologies have been adopted into current use; sometimes as a function of the production method itself (Table 1). Certain technologies were not relevant to respondents, depending upon the type of production system (i.e., container grown, field grown, mixed system container and field) about which they were reporting, and therefore all possible comparisons were not made. For example, “mechanical bundlers” was not a response option for container-only nurseries. More container nurseries (56.7%) and mixed system nurseries (48.1%) adopted liquid fertilizer injectors than field nurseries (23.4%). Survey results suggest that responding field nurseries (10.6%) currently use fewer conveyers than either container (40.0%) or mixed nurseries (42.3%). Field nurseries (25.5%) use lifter/shakers more than mixed operations (1.9%).

Since the 2006 nursery survey, automation of nursery tasks has roughly doubled, yet automation of tasks remains below 35% when averaged across all types of tasks. Some types of automation have been adopted more quickly than others. The current survey found that conveyers ( Fig. 3 ), although a technology newly available for the green industry, were as widely adopted (33.3%) as other pieces of automation that have been available for field and container production for a long time, such as B&B tree handlers (33.3%) and substrate mixers (35.2%). In the 2006 nursery survey, just 2% to 9% of nurseries used conveyers for moving plants, with the exact percentage varying by the specific plant handling task (Coker et al., 2010, 2015).

Figure 3. Conveyers can be used to move plants following potting onto wagons and when orders are pulled to move from wagons to trucks or shipping racks.

Table 1. Nursery use of automation and mechanization technologies as determined in a survey of decision-makers representing the U.S. nursery industry. The survey was conducted in 2021 and asked about practices that respondents used in 2020.

z Significance was tested using ANOVA and Tukey’s honestly significant difference test at a significance level of 0.05. Within comparisons between production methods, presence of an * in the corresponding cell indicates that the automation technology used was different between the two production types being compared; an NS in the corresponding cell indicates that there was not a significant difference between the two production methods; – in the corresponding cell indicates the comparison was not made because the automation technology was not applicable either to one or both production methods.

Several factors can influence which automation is readily adopted. Some forms of automation, such as tractors, trucks, and wagons, have multiple uses within nurseries, whereas some of the lesser-adopted automation technologies have very specialized applications. For example, robotic plant spacers, mechanical stake drivers, and pneumatic C-ring fasteners are all helpful in reducing manual labor, yet each accomplishes only one specific nursery task. Other types of automation require a large capital expense that may be cost prohibitive for smaller nurseries and other nurseries that operate with smaller profit margins. In the 2020 survey, nursery producers responded that purchase and installation and related costs associated with automation technology were the highest-ranked barriers to automation (Rihn et al., 2022). In addition, some automation is not stand alone but rather necessitates more involved planning, additional space allocation, and other changes that can increase the overall complexity and costs of adopting the technology. As an example, investing in a potting machine includes a capital expense of at least $50,000, as well as a protected structure such as a building, plus access to 3-phase electricity and/or a generator (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). Adoption of a potting machine may also require additional hoppers, a dedicated front-end loader, more tractors and tracking trailers, and drivers to achieve maximum efficiency. Ironically, a potting machine may require a significant amount of task-dedicated labor at fixed time periods to maximize its production capacity. One Tennessee nursery recently adopted a potting machine that requires approximately 15 workers to maximize its pots-per-minute output capacity.

Figure 4. Building, conveyers, hoppers and other costly infrastructure may be needed when investing in a potting machine.

Figure 5. A generator necessary to operate a portable potting machine.

While cost is a known barrier to adopting some automation technologies, there are programs that can make automation and other capital improvements more affordable. Tennessee nursery producers have a unique opportunity to invest in automation through a partnership between the Tennessee Department of Agriculture’s (TDA) Tennessee Agriculture Enhancement Program https://www.tn.gov/agriculture/farms/taep. html and the University of Tennessee’s Tennessee Master Nursery Producer (TMNP) Program www.tnmasternursery.com. Following TDA acceptance of their application, growers can fulfill their eligibility for enhanced levels of cost share, currently at 50%, with a current TMNP certification, versus just 35% cost share without the TMNP certification. Some of the technology that growers can apply for include automated irrigation controllers, sprayers, and potting line equipment.

••••••••••

Automation Side Benefits

In 2020, the LEAP Team held national listening sessions and talked with nursery leaders from across the U.S. Many growers on the call had already taken the plunge and invested in automation. Other than labor savings, what were some of the most common benefits that they listed? Product consistency, predictability of task completion, and timeliness of tasks leading to more uniform products. By better controlling when crops are pruned, the production manager can better control when they will be in flower or achieve market size. By investing in potting technology, large volumes of a crop type, such as crops grown on contract that need to be ready for sale at the same time, will be potted within a smaller time window and reach their “finished” size together. For example, one nursery was able to accept an order that was due in eight weeks because the nursery was able to pot 19,000 plants in three days. If done by hand, the potting step alone would have taken the nursery three weeks to complete. One of the take-home messages from the listening sessions was that nursery producers who invested in automation did not just achieve labor savings, they gained better control of their production schedules and gained new sales opportunities.

••••••••••

References and Additional Resources

Coker, R.Y., B.C. Posadas, S.A. Langlois, P.R. Knight, and C.H. Coker. 2015. Current mechanization systems among greenhouses and mixed operations. Bulletin 1208. Mississippi Agriculture and Forestry Experiment Station. http://www.mafes. msstate.edu/publications/bulletins/b1208.pdf

Coker, R.Y., B.C. Posadas, S.A. Langlois, P.R. Knight, and C.H. Coker. 2010. Current mechanization systems among nurseries and mixed operations. Bulletin 1189. Mississippi Agriculture and Forestry Experiment Station. http://www.mafes. msstate.edu/publications/bulletins/b1189.pdf

Posadas, B.C. 2018. Socioeconomic determinants of the level of mechanization of nurseries and greenhouses in the southern United States. AIMS Agriculture and Food 3(3):229-245.

Rihn, A., M. Velandia, L.A. Warner, A. Fulcher, S. Schexnayder, and A. LeBude. 2022. Factors correlated with the propensity to use automation and mechanization by the U.S. nursery industry. Agribusiness. 2022:1-21. https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.21763