SUMMER REPORT

Foundations, Applications, and Aspirations at SOM

JUN 3 - AUG 9

JUN 3 - AUG 9

Foundations Applications

The Pillars of Innovation

Beginning the SOM Journey

The Big Build Challenge

Six Projects Six Urbanism

Modern City Building

Aspirations

Cultural Reflection and Expectations

Summary of Growth

Future Goals and Gratitude

Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill (SOM) is an architectural design firm founded in 1936 by Louis Skidmore and Nathaniel Owings in a Chicago loft. Their friend, engineer John Merrill, officially joined in 1939 and established the first branch in New York in 1937. SOM is one of the world’s most influential design firms, offering architecture, interior design, engineering, and urban planning. Since its inception, SOM has worked on the design, planning, and construction of single buildings and entire communities, such as office towers, financial institutions, government buildings, medical facilities, religious buildings, airports and other transportation hubs, interior renovation, entertainment and sport architecture, campus design, and large mixed-use complexes.

SOM is not only an architectural design firm, but also a professional research organization. It claims to be more like a laboratory, constantly exploring new design practices and creative solution. Every member within the team is dedicated to developing and designing creative concepts that have become industry standards and are used around the world. And clearly SOM has been follow this standard since the beginning. From its early days as a collaborative design platform to engineering solutions for the world’s tallest buildings, SOM has been dedicated to researching transformative changes in architecture, engineering design, urban design/planning, and interior design.

Today, SOM continues to investigate the latest technologies that are altering construction methods in the digital realm and taking the lead in developing sustainable solutions. At an

exhibition in London, SOM displayed an arched structure constructed by robots using glass bricks, demonstrating the potential of new and efficient construction technologies.

The company also brings its experimental spirit into the twenty-first century to address the pressing issue posed by climate change to human survival. SOM’s architects, planners, engineers, and designers are collaborating to find emergent solutions, with a focus on sustainable development projects. SOM addresses ten major urban issues, including livability, affordability, ecology, cuisine, mobility, waste, water, urban resilience, energy, and historic preservation. These ten components form the basis of SOM’s design process, which seeks to achieve sustainable development goals while promoting economic and social progress.

Teamwork is another golden rule within the firm. Every project is the result of the collaborative efforts of talented individual. SOM, founded by two architects and an engineer, has long believed that the power of collective wisdom outweighs individual ability. Collaboration within the team ensures that SOM’s designs remain unique and innovative. Furthermore, the project team includes designers and engineers with exceptional artistic abilities and advanced professional knowledge, as well as project managers with a thorough understanding of policies and economics. This multidisciplinary collaboration produces far more comprehensive design solutions than a single designer could produce on his or her own.

Throughout all 5 internships that I had before, SOM seems to be the most extensive, challengeable, rewarding internship among all. Not only because its well-prepared training program, but the holistic learning environment that every employee promotes. The internship program offers valuable experience for future planners, architects, and structural engineers. To test, to dream, to practice their idea, every intern get a chance to explore things beyond school. Additionally, interns can learn about SOM’s architectural legacy in New York City through carefully curated site visits, which are a program highlight. Interns gain insight into SOM’s architectural philosophy and impact on New York City’s urban fabric through carefully curated visits to the firm’s most iconic projects.

In addition to site visits, the program offers Lunch and Learns, a series of lunchtime lectures on the latest trends and innovations in the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry. Interns can interact with industry leaders, broaden their knowledge, and learn about emerging technologies and practices shaping the future of architecture and construction scope of work.

Getting closer to the end, the internship program highlights the exchange day with Turner Construction, which provides interns with a comprehensive understanding of the construction process from planning to execution. Interns also have the opportunity to visit Turner’s active construction sites.The experience gives a thorough overview of how architectural design

is accomplished, emphasizing the significance of collaboration between architects and builders.

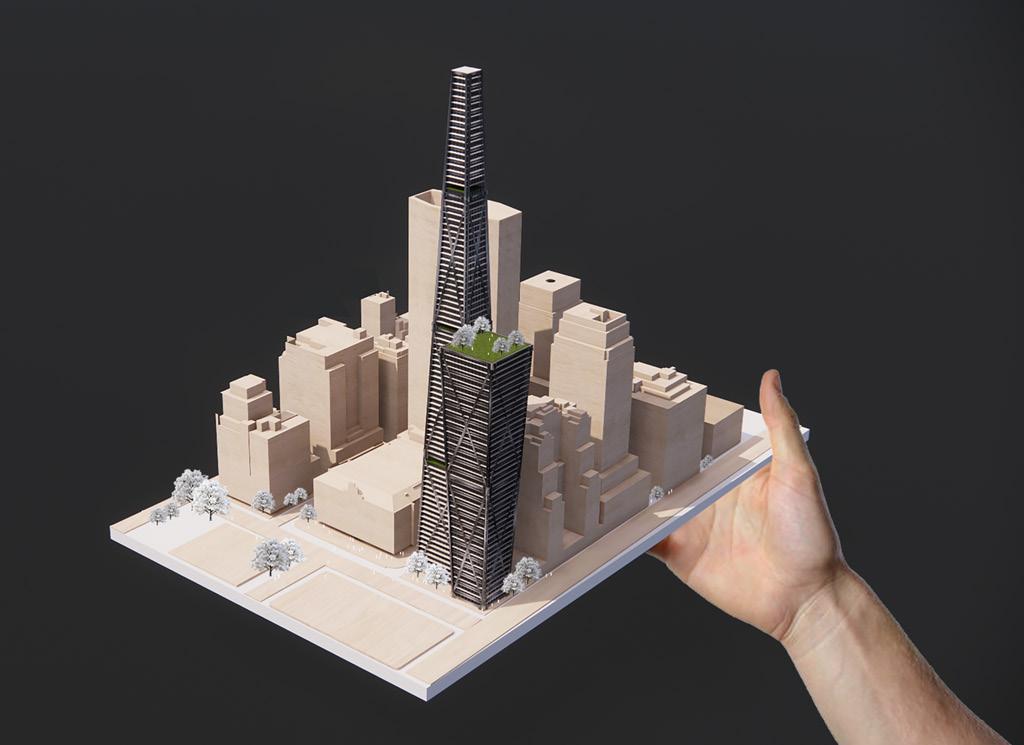

Since 2019, the Big Build has been an annual competition between interns. Four teams of structural engineering, architecture, urban design, and interior design interns were formed to participate. In these groups, interns worked with their peers for three weeks to design and build a tower measured from four different criteria, height, aesthetic, structure stability, and sustainability. This year, we’ve been assigned a site at 109 E 42nd St in midtown Manhattan, which already houses a Grand Hyatt hotel. Despite the fact that this is an internal competition, the team has been fully engaged and

motivated to complete the work.

The site is located in one of Manhattan’s busiest areas, Grand Central Station. More than 750,000 people pass through the terminal, and an estimated 10,000 people visit for lunch, exercise, and shopping. It is not easy to construct anything next to this massive transportation machine. Our team quickly became acquainted with the site and attempted to understand it through our own expertise, as we all saw it from different perspectives. But the main focus is on three tasks: transportation-oriented devel-

opment, adaptive reuse, and structure innovation. Because of time constraints and competition requirements, the team has agreed that we can only complete the work successfully if we solve all of them collaboratively early in the competition. The city was not built by dreamers, but by a group of practitioners. Thus, we untangled our project in a realistic manner and attempted to follow the workflow that we learned at SOM.

The site has provided us with a new opportunity to alleviate New York City’s housing crisis, though we recognize that building offices and hotels will be more economically viable. However, this high mixed-use community, which essentially reduces the size of commercial space while providing more market rate and affordable housing, will allow for more sustainable and risk-averse development, especially given the recent pandemic. Architects and structural engineers collaborate to achieve the highest design quality while adhering to the Floor to Area Ratio (FAR), height constraints, and program distribution guidelines. This is the place to demonstrate the magic of SOM as a collaborative operation combining the efforts of engineers and designers. Reliability, stability and efficiency are essential for primary structure in any project, but we cannot overlook or underestimate the formal aesthetic and user experience provided by architectural design. Embracing the site’s unique past, the building massing is designed as vertically stacked programs separated by a garden that extends the public space. Each program, when stacked vertically, creates a unique architecture that is deeply rooted in New York City’s increasing heat island effect. The new structure incorporates architectural elements such as high ceilings, verandas, lush courtyard gardens, and a terra-cotta facade. This referencing not only links the architecture to its specific context, but it also rediscovers the wisdom of iconic responses from the past, which is still very relevant today.

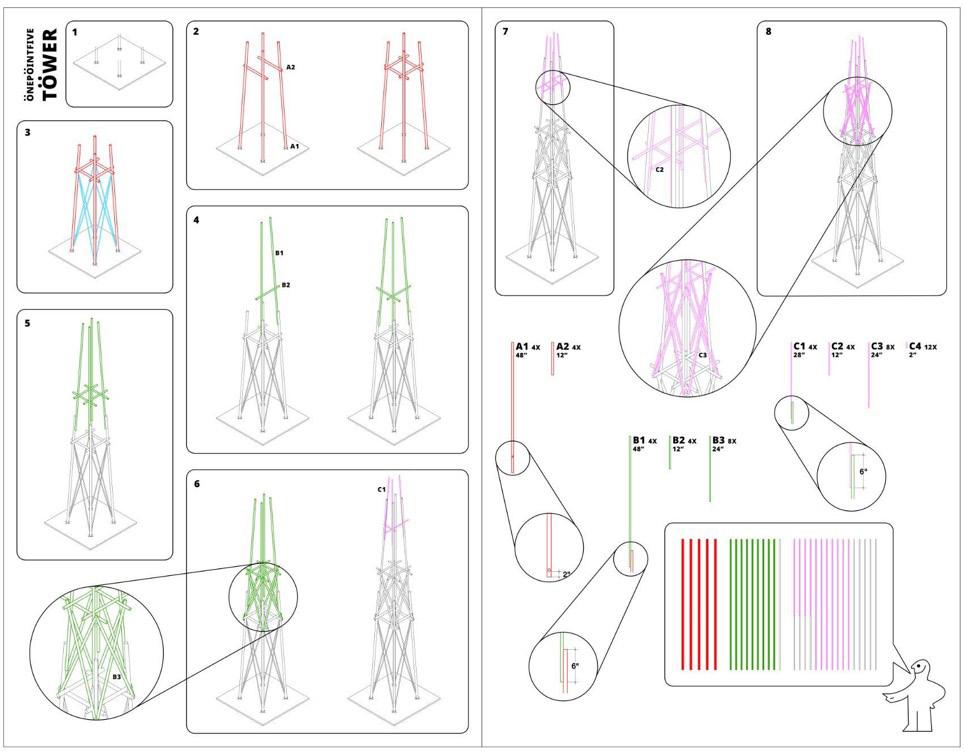

The actual Big Build Day is limited to four hours with provided materials and tools. Our team has prepared a design manual that clearly

documents each step of the tower installation process in advance. We understand there are two parts to the competition: an undefeated design and a solid construction process. Just like a real project, effort is required during both the design and construction phases. However, you would never expect what is coming during the process. The team ran out of time and materials at the last moment, resulting in a less stable foundation for the entire tower. Overall, it was a fun experience, and each team member is extremely responsible with their expertise.

SOM, a design firm known for its interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, and global teamwork, is constantly encouraging innovation. During the Big Build Competition, we collaborate with SOM staff, attending multiple sessions led by a team of architects, planners, and engineers, applying classroom knowledge to complex design environments, and learning on the job.

During my time as an Urban Design/Planning intern at SOM, I was fortunate to be involved in six different projects, each with a unique focus. The full exposure to current City Design Practice in the New York City office allows me to reflect on the current world-class development both domestically and internationally. Building successful twenty-first-century cities will require more than just throwing around catchphrases like “smart city,” “sustainable development,” and “economic growth.” Instead, the internship taught me to think in terms of active principles that will help me with the ongoing task of designing rich, rewarding, transit-enabled, high-density cities while taking into account air, water, people, policy, interest rate, scale, and other urban design essentials.

Comparing these projects in different regions, cities, and communities can teach us a lot because they all address a pressing issue in today’s world. Due to project confidentiality, I am UNABLE to share the project’s name or any other details, but I would like to go a step further and discuss which typology they fall into. The FIRST is the project’s identity, which either creates or preserves a distinct feature of the environment.The SECOND aspect is compatibility, which helps to maintain regional harmony and balance. THIRD, adaptability enables transformable design features and positive growth. The FOURTH component is diversity to ensure variety and choice. The FIFTH component is open space, which regenerates the natural system and makes cities greener. The FINAL one will be sustainability, which refers to a long-term commitment to the ecological ethic.

City designers require a set of overarching principles to address larger concerns and improve urban life quality. Equally important, designers must protect and improve the natural environment that all cities inhabit. These principles are fundamental to persuasively commu-

nicating the need for city stakeholders to consider urban growth in terms of creating livable, sustainable communities.

It is imperative for us as city builders to acknowledge the potential value that a harmonious environment in a city can impart. This enables us to approach spatial patterns from a wholly humanistic perspective, enabling the realization of designs that will truly benefit the general public. Thus, examining how individuals interact with and view urban environments can aid in our understanding of what constitutes a satisfying experience and what distinguishes a city. How can these findings be applied to create more livable spaces in future designs?

Three components make up the analysis of environmental imagery: identity, framework, and meaning. The word “individuality” is a direct translation of “identity.” Recognizability and individuality go hand in hand, and when an urban element has a distinct personality, it is frequently recognizable at the same moment. Examples include New York’s World Trade Center (icons) and Fifth Ave. (streets), which is well-known for its luxuries. Meaning is related to meaning. For the time being, the author disregards the meaning component of the study and concentrates on the comparatively objective imagery of urban form features since meaning involves too many individual, social, and cultural differences.

Buildings, landscapes, and people must all be interconnected to form an integrated whole if a unique city is to be constructed. A clear and profound impression can only be achieved by connecting the sensory experience with the real meaning. In order to build cities that

people from diverse backgrounds can enjoy, we should focus on the imagery’s material clarity and give the meaning room to grow. It is important not to overlook the city’s essential operations. Therefore, realistic, meaningful, safe, development-friendly, and communicative urban imagery is necessary for making cities livable and supporting spatial orientation.

Follow with Compatibility, which builds on identity by ensuring that the design fits within its context and works harmoniously with surrounding elements. In an urban setting, compatibility is characterized by the greatest number of choices and differences. It should go without saying that the best cities provide their residents with the widest range of options, all of which have the highest likelihood of success. By offering the most job and educational opportunities while preserving economically viable living and working options, the compatibility principle promotes sustainability. The city is by its very nature sustainable, and compatibility adds to its livability and attractiveness. Compatibility demonstrates its support for accessibility by promoting the advantages of using a variety of transportation options. By encouraging a diversity of visual experiences in a city through a mix of old and new, large and small, and recognizable places and buildings, compatibility supports the identity principle.

Plans for district or city development that are inappropriate can be easily identified because they are discordant, confusing, oversized, disproportionately small, or just “wrong” for the environment in which they are intended to be used. Places that are actually livable typically make sense in terms of the size and composition of the surroundings. Determining the appropriateness of city design requires defining a project’s character. In order for a project to be successful, it is necessary to first comprehend its fundamental nature before determining the necessary physical attributes for the given situation. The design process and the contextual character are the two main points of emphasis.

Urban design needs to be examined and studied at every stage of development to make sure it fits right. This procedure clarifies the compatibility problems and offers suggestions for potential fixes. Urban planners frequently discover that a community is unable to concentrate on finding a solution to a land-use issue. For instance, every political campaign season brings with it fresh project ideas to address a declining downtown, such as the construction of a ballpark, a new city hall, main street beautification, and so forth. In these situations, shifting the context could break the impasse. For instance, planners might reframe the issue in terms of a larger citywide project, like restoring a public shoreline, where all interested parties can see the advantages.

During a public review process, showing how the part planners are thinking about relates to the bigger picture usually makes it seem more important and can give new ideas for how to tackle the bigger picture. One crucial component that is often lacking in the process of designing a city is the capacity to comprehend and convey the larger context.

How can we acknowledge that there is no absolute precise solution can be predicted in today’s urban design? Each large urban development spans more than decades and requires certain degree of adaptability to accommodate the growth of the city. The principle of adaptability seems provides an important distinction between urban design and pure architecture design. Oftentimes in real estate market, a costly development is made by plans that reflect absolute architectural certainty. Such plans tend to be limited, too rigid. Urban design on the other hand inevitably expect programmatic change, ownership replacement, transition in natural environment, etc. Ultimately, future-facing urban design creates a compelling physical framework that can tolerate the ongoing change of physical elements and uses and still maintain a sense of wholeness overtime.

The idea of adaptability can be both applied

to the physical form and uses. Without the discipline of dividing large sites into parcels, human nature aims at placing new buildings in the center of whatever land is available. Doing so almost destroys a number of additional potential building typology that would have been available if thoughtful parcelization had been accomplished. Zoom in to a building, in the nature of things, old tenants give way to new, while change in usage lead to new design requirement and sometimes a total renovation of a site. This mutability is organic to city life and must, therefore, be organic/adaptive to city design. To enable adaptable use changes, these design elements should be considered: site adequacy, building adaptability, and open space adaptability.

Experience, history, and science all demonstrate how diversity is fundamental to natural systems. Successful human-scale city development requires both choice and variety. A livable city should have a variety of housing options, employment opportunities, services, cultural and religious events, eye-catching architecture, recreational and leisure activities, and easy access to healthcare and education. When combined, these options give city dwellers the greatest variety of chances to lead fulfilling, varied lives. The maximization of mixed use and visual variety are two crucial components of the variety and choice principle for city builders. If diversity in the visual arts uplifts people’s spirits, then a blend of residential, commercial, and service uses gives cities the drive to keep them vibrant and forward-thinking around the clock.

A diverse range of buildings, both old and new, big and small, bold and modest, can be found in good urban settings. As obvious as it may seem, variation is crucial to producing a visual interest that draws the viewer in and stimulates their imagination. The widest range of cultures, ages, languages, ethnicities, economic strengths, and lifestyles are expressed and benefited by a good city.

Since the middle of the 20th century, and more so now, the speed and scope of development are causing these components of diversity to vanish or, at the very least, become more challenging to combine. In certain regions of Asia, entire neighborhoods are being constructed in one go, using only one style of residential building. Although this “repetition compulsion” may achieve programmatic objectives, it nearly never offers subtle, human-scale variation. Furthermore, it falls short of providing the options for living, working, and recreation that greatly enhance a city’s allure. A culture’s ability to tolerate repetition, or at the very least, to put up with it, is inversely correlated with diversity. Experience has shown that, regardless of project size or development pace, the best city developments foster choice, diversity, and economic vibrancy. Three design techniques can help create an environment that is visually appealing.

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of urban construction is open space, which is far more crucial to livability than is commonly realized. Climate and cultural differences influence the types and attributes of open space, but good urban design always demands certain natural attributes to mitigate the harshness of the city and the built environment’s constraints. Numerous studies have demonstrated the positive effects of green spaces on one’s physical, mental, social, and spiritual well-being. Urban green space is essential for public health, social cohesion, and sustainable living in addition to being aesthetically pleasing. By applying their skills and professionalism, landscape architects create spaces that are healing, increase economic value, raise educational attainment, and strengthen resistance to climate change. Their work goes far beyond simple landscaping. As a result, together we are crucial in understanding and forming how humans and built environment interact. Mental health, social structure stability, physical health, child development, senior health, community economic vitality, and environmental sustainability are all directly impacted by this work.

Let me address mental health first. Numerous studies have shown the positive effects of green spaces on people’s mental health. For instance, how it affects stress relief, mood enhancement, focus improvement, and cognitive function enhancement. There is mounting evidence that being in green spaces can lessen the symptoms of anxiety and depression. Additionally, green spaces can improve community safety and uplift residents’ mental well-being. My previous work and research at MIT Sensible City Lab even proved a positive relationship open space and resident’s happiness from urban data point of view.

One of the most well-known psychological advantages of green space is that it aids in the recovery of individuals suffering from cognitive fatigue. People encounter cognitive fatigue, also known as mental fatigue, at some point in their lives. It is especially noticeable in our fast-paced, technologically-dependent society. It shows up as persistent mental exhaustion, poor attention span, and decreased effectiveness when solving problems. Studies indicate that even a short period of time spent in nature can have a major positive impact on mental clarity and attention span. This has real consequences on productivity, emotional well-being, and even long-term mental health; it’s not just a “feel-good” factor.

Green space design is crucial for fostering social equity and community building in terms of social cohesion. Green urban environments meet broader public health objectives by fostering social interaction, a sense of belonging, and social equity. The profound comprehension that landscape architects possess regarding the ways in which green space components impact individual behavior and social integration can also be useful in public health strategies that support social equity and are founded in conventional medical interventions.

We can begin to comprehend the complexity and actual nature of green spaces by acknowledging the innovative role played by urban designers in creating these areas and appreciating their influence. The fundamental issues

that we subsequently need to address are then established by this multifaceted viewpoint.

We need to start thinking about whether a project will take up irreplaceable land in the new world of sustainable development. This includes land that is suitable for agriculture, land that supports ecosystems that impact plant and animal life, and land with scenic qualities. Developers must also carefully assess an area’s suitability, avoiding areas vulnerable to wind, earthquakes, flooding, wildfires, storms, and damage from the sun. Air and water are more important to maintaining a population than almost any other resource, thus they must be preserved. Environmental carrying capacity and land-use management are commonly used to protect the air, water, and other natural environment elements.

Comparing data on air and water quality and quantity in relation to population growth and associated pollution has become a common practice for planners. Finding the development capacity within particular air basins and watersheds can be done with the help of this relationship. Over time, the relationship has the potential to improve. An area can support a higher population while maintaining the appropriate levels of air and water quality and quantity through intelligent environmental stewardship.

Planners must take into account new land zone designations in order to prevent destructive natural hazards and to preserve or regenerate irreplaceable lands, such as animal migration corridors, riverfronts, watersheds, and high-quality agricultural lands. These will specify which lands need to be preserved as well as where and when nondestructive urban development is allowed.

These days, infrastructure spending is almost always the result of haphazard, ad hoc development decisions, despite the fact that it is primarily funded by the public. Unfortunately, “following the developmental money” frequently results in settlement patterns that are disjoint-

ed, unreliable, and unsustainable. Instead, in order to direct new city growth toward areas that meet sustainable goals, infrastructure supporting those goals should take precedence.

The relationships that people have with their built environments on a functional, visual, and tactile level are at the center of what I would refer to as “the present tense” of city building today. Intelligent modern city planning is fundamentally concerned with maximizing and improving those relationships. All of the major planning domains - housing, transportation, open space, institutional services, infrastructure, industry, and commerce - are covered by this straightforward mandate.

The idea that the physical environment can be usefully shaped and that different design techniques can produce a desired physical form is the foundation of the practice of city design. In order to achieve desired outcomes, any coherent philosophy of city building must also assume that the design process can influence political and economic forces. City design is typically understood to operate as a component of the public realm, from which it can inspire, direct, and influence actions in the public and private sectors. However, this is not always the case.

The emphasis on the public interest in city design stems from the government’s historical accountability for important tasks like maintaining open space, streets and transportation networks, community services, and utilities. Urban planning/design can influence the general quality of the environment and assist in arranging later private development by assisting in the design and arrangement of these fundamental services.While public sector management is

still emphasized in planning practice today, city design services are increasingly being hired directly by developers or by a combination of public and private entities for large privately financed developments. Design studies in these cases begin with an investigation to determine the appropriate purpose and feasibility of the project. Plans present alternative ideas for the character, function, and creation of a quality environment. The goal is to guide both new private development and redevelopment, both of which accommodate public-interest requirements.

With the ultimate goal of bridging the gap between design and planning, city building makes a significant contribution to the even more expansive field of environmental design by coordinating and connecting the contributions of engineers, planners, architects, and landscape architects. When used as a cohesive unit, this multidisciplinary team approach can counteract the pressure to grow. With the responsive building design, sufficient access, and required services, a planning program can satisfy the needs of contemporary development, openspace preservation, environmental preservation, and sustainable growth.

SOM is a company that adapts quickly to the changing needs of the world and considers the needs of various individuals when advancing their careers. Many organizations have been formed for different types of workers, including those advocating for gender equality in the workplace, those holding seminars and trainings, and various minority groups. More recently, an Asian organization has started to take shape, with the goal of enabling everyone to find their own belongings. There is an annual career evaluation for each person, even though

there is no specific target for promotions. The assessment has a very clear framework, and it allows for good two-way communication between the individual and the assessor. This allows for a better understanding of the individual’s strengths and weaknesses as well as their career development plan. Setting better goals for the future and recognizing one’s strengths and shortcomings both benefit from good twoway communication.

Every SOM office functions as a studio. A de-

sign studio head and a technical studio head typically oversee different aspects of design and technology within the team. Although cross-office and cross-national coordination is frequent, it essentially consists of various fields working together. For instance, San Francisco might handle the overall architectural design of a project in China, Chicago would handle the institutional design, New York would handle the landscape, and London would handle the interior design. A studio can serve as a good model for personal development, and if you can stay on the same project team throughout, you can observe each other’s growth and cultivate a tacit understanding that will help you advance in your career. Learning in various groups can also broaden the network as people share and learn from one another at the same time.

I can tell that every employee at SOM are passionate about architecture and the company from our conversations. Being a global business, SOM surely offers its employees a global perspective and a more extensive platform for cutting-edge research and education in addition to design and construction. Simultaneously, SOM, being a big business, has its own operating systems, which serve as a good model for designers wishing to build their own sky. However, there are some differences between different offices because of the influence of various industry systems and cultures, and we hope you can have a more thorough understanding.

While research can be done on city design, design city is a highly specialized field. As a student in Harvard GSD’s Master of Architecture in Urban Design program, I’ve been tasked with using an architectural perspective to gain a detailed understanding of the dynamic within cities, including housing, infrastructure, public

space, ecology, and other subjects. Urban design has a variety of presences and functions in different times, economies, societies, cultures, and political backgrounds in every city, despite being a long-standing method of shaping the built environment. Urban design can be understood as various forms and executions based on courses such as Cities By Design or Urban Design Contexts and Operations. It can be applied to the planning policy to guide spatial development, or it can be combined with craftsmanship and mathematics to build cities in antiquity. It can also be incorporated into future city visions or simply serve as a management tool. With an emphasis on diverse clientele, it can even be referred to as town design, landscape urbanism, total design, etc. I have frequently found it difficult to precisely define urban design in academic settings, as the field frequently occupies an ambiguous intermediate position.

Although the school has given us a wealth of design knowledge, skills, and vision, it lacks the complexity and practicality of managing a project in the real world. Both are essential to urban designers, but it appears that only practice strikes a good balance between the two in terms of degree of rigor. Urban design is both a practice and an art form that deals with creating spaces for people in urban areas. The secret to success is knowing how to properly negotiate each skill we have learned and use it at every turn. In practice, we make assumptions, but occasionally we overestimate them to the point of oblivion or fail to recognize the boundaries within the academic community. I’m not saying that studying urban design in school is good or bad, but the internship or practice can make us reevaluate how we approach projects using creative yet useful design strategies. As a result, students won’t have any trouble defining urban design correctly or determining whether there are any particular processes that lead to good urban design.

Timing varies greatly. The summer internship is a crucial chance for students enrolled in Harvard GSD’s two-year Master of Architecture in Urban Design (MAUD) program to re-establish

their career path prior to the start of the second year. Whether you are an urban designer with architectural precision, an architect with an urbanist mindset, or a real estate developer who values design in general, all it takes is to test your interest in the real world to see how much it can change your perspective. In addition, MAUD is a post-professional program that requires each student to enter with a specific level of knowledge about the AEC (architecture, engineering, and construction) sector. Upon graduation, students are expected to apply the knowledge they have acquired in school to their chosen career path. An improved way to approach this would be to consider the entire MAUD period as three parts (you could divide it even further if you’d like). The first part would be phase A, the second part would be phase C, and the summer between the first and second years would be phase B. Try to investigate a variety of urban design options in Phase A, test them out in Phase B, and either stick to your decisions from Phase A or continue to hone your passion.

In my future professional path, I’ll keep honing my graphic communication skills and concentrate on my capacity to transfer theory into practice. I’ll keep raising my standards and becoming more professional by reading books on the subject and going to classes that are pertinent to the current state of affairs. I’ll make an effort to put what I’ve learned into practice and gain experience for my next job. I’ll put a lot of emphasis on honing my oral expression and communication skills when it comes to communication skills. Cross-cutting issues, like the need for climate change plans to balance the interests of the public and private sectors, frequently call for integrated activities across multiple disciplines. the requirement for equitable land use, housing, transportation,

environmental protection, and equity considerations in climate change plans. Regarding my future professional goals, I’m committed to stay employed in the architectural and urban design fields and to carefully consider my areas of interest and strength. But I also learned from my internship at SOM that we need to set realistic career goals based on market demand and industry trends. It is critical that we identify our areas of expertise and passion in the AEC industry.

During my brief seven-year career transition from architecture to urban design, I completed six different internships, SOM has been the most influential to me professionally. I owe a debt of gratitude to SOM for giving me worthwhile internships, as well as to all the seniors who have mentored and assisted me. I would like to express my gratitude to Keith and Angel for giving me the chance to speak with them over coffee, for giving me more specific ideas for developing my career going forward, and for pointing out the aspects of my work that needed improvement. Additionally, I would like to express my gratitude to Jenny, Alex, and Shivani for their encouragement and support, which have helped me advance in my practice. My teamwork, communication, and project management abilities have all significantly improved as a result of this internship. Despite the short duration of this summer experience, I felt really satisfied. I’ve grown up doing research and enhancing it with practice, from working hard and being passionate about my work to learning how to reflect on it. I’ve been able to extend my horizons, sharpen my critical thinking abilities, learn how to interact with people on a global scale, and truly experience the coziness and warmth of our departmental family thanks to this internship. This will be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity that will greatly influence how I plan my future career.

In addition, I want to express my gratitude to the 22 individuals that I collaborated with during my internship. Our regular happy hours and daily lunches helped us to become close friends and learn more about one another. Despite our lack of victory in The Big Build, I

would like to express my gratitude to my teammates, Albertine, George, Xuefei, Ankit, and U jin. I had a great opportunity to learn from my teammates because of everything from U Jin’s extremely detailed user’s guides to Albertine’s expert knowledge of the architecture to Ankit’s meticulous approach. When I ran out of ideas, my desk companions Nal, Kaicheng, and William also offered me countless possibilities. I welcome you to visit me at Cambridge in the upcoming year, and I hope that we can all continue to grow our friendship for many years to come.

Lastly, I want to express my gratitude to my girlfriend and parents for their encouragement and support throughout my career aspirations outside of my internship.

This Harvard Summer CPT report maintains strict confidentiality. No project names, client details, or sensitive information related to SOM are disclosed. All images are credited to Chenhao Luo and must not be used elsewhere. This report is solely for academic purposes and should not be shared beyond this context.