15 minute read

What Lies Beneath Above: Mineral, Wind, and Groundwater Estates in Texas and The Severance Implications

from THL_JanFeb21

by QuantumSUR

Energy companies will be left behind if focus is not shifted to what is shaking our global conscience: climate change, the economy, the COVID-19 pandemic, and racial inequality. This is a reckoning period. Reinvention is amiss. In 2021, energy companies must cut greenhouse gas emissions by exploring investments in renewable energy and green technology amid pressures from investors, regulators, and customers. Even the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission is directing companies to focus on climate-related disclosures.1

These pressures have mounted in Texas after the statewide electricity crisis in below freezing temperatures. Yes, we now know that the cause of the Texas Blackout was a “perfect storm” literally and figuratively—the combination of freezing natural gas pipelines, failed wind turbines, the loss of some natural gas and coal generation, and the loss of a nuclear reactor.2 Here’s what happened: Cold temperatures forced an extreme electric demand and a decrease in supply. Wind turbines froze. Natural gas wells froze, too. And pipelines. Don’t leave out the critical pipes at coal and nuclear power plants; they froze as well. Equipment panels went offline. The “perfect storm” for disaster.

Energy companies face a complex problem: building reliable infrastructure in the midst of climate change while creating jobs and a clean energy economy under President Biden’s goal of reaching a net zero emissions future by 2050.3 The collective impact of the pandemic, the blackout, and climate change has increased the draw of investment in diverse, green energy assets such as wind power. The severance of the wind estate in Texas is unclear, but legal precedent provides guidance. Let’s analyze a scenario to highlight the issue.

Wind estate severance: an example You have volunteered to take a pro bono case. The client is an elderly developmentally disabled woman from Humble, Texas. The client’s personal representative is her brother. Upon death, the parents devised the client a ranch—understanding the gravity of the client’s current and future medical expenses, living expenses, and care. The 2,700-acre ranch has a producing well, an aquifer, and some farming equipment. The client wants to sell 25% of the wind estate to an Austin investment firm. The client’s brother says that this transaction would allow them access to immediate cash, funds to pay off expenses from the estate, money for future medical expenses and care, and future royalties. The client and her brother ask for your legal opinion on the severance of the wind estate and the implications of the client’s other property rights. Keep in mind that a wind lease could provide various payments and compensation for the client such as royalties, bonus payments, delay rentals (on development fees), rents, and options, along with fees for surface disturbance, installation, and facilities. Energy

produced from wind could also aid in another Texas blackout or freeze.

Lucky for you, the resources and available information to advise the client are vast. The State of Texas leads the nation in the production of oil, gas, and wind energy.4 Texas favors citizen profitability from the private ownership of mineral estates. Under Texas law, one can sever property devising title to the surface estate to one party and title to the mineral estates to other parties.5 Unfortunately, Texas has not recognized the outright severance of the wind estate. This article provides readers with legal and practical clarity on why the wind estate is a severable property interest just as the mineral and groundwater estates are severable.6

traditional estate severance in texas Estate severance in Texas is deeply rooted in private property rights.7 Texas common law provides clarity for property owners with interests in wind estates, surface estates, mineral estates, and groundwater estates.8 It is likely that the Texas Legislature and the Texas judiciary will follow the precedent applied to groundwater and mineral estates and affirm that the wind estate may be severed from the surface estate. The idea that surface owners hold the right to the wind that flows across their land is supported by Texas common law—cujus est solum, ejus est usque ad coelum et ad inferos—to whomsoever the soil belongs, it is theirs up to the sky and down to the depths.9 Precedent upholds the right to use land to establish the necessary equipment to build a wind farm and the right to use the airspace appurtenant to the land both reside with the surface owner. Even though there is not yet Texas case law or a statute directly addressing the severance of wind rights, a wind severance will likely be upheld if challenged.

Throughout the history of the Republic of Texas and State of Texas, property owners have been able to make decisions about their own property. For example, during the Great Depression, landowners sold their mineral estates to produce income to take care of their families.10 Oil, gas, groundwater, granite, caliche, and uranium are all individual mineral rights in Texas that can be individually severed.11 Therefore, a Texas landowner should have the option to retain, convey, or bequeath all property rights, including those in the wind estate.

Groundwater estate severance law serves as a Guide Texas treatment of groundwater provides sufficient guidance for the severability of the wind estate.12 Texans have had a longstanding relationship with their water supply. In 1917, Texas voters ratified a water-related amendment.13 The amendment created “conservation and reclamation districts” as units of local government and made the preservation of natural resources a public right and duty.14 Of all the water we use in Texas, about 60 percent is groundwater; the other 40 percent is surface water.15 In 1972, the Texas Supreme Court found that “[w]ater, unsevered

expressly by conveyance or reservation, has been held to be a part of the surface estate.”16 The Court pronounced that surface interests include “not only the soil, but also any underground water supplies at all depths under the land” but exclude “the oil, gas and other minerals therein.”17 Though the groundwater estate was held to be a part of the surface estate, the express conveyance or reservation of the groundwater estate creates a severed estate. This supports Texas’s historical posture that Texans have the right to contract regarding their “bundle of sticks” as they see fit.18 Wind should follow this pattern, policy, and practice.19

old theories Provide the Foundation for Wind estate severance Courts have provided an outline for the severance of the wind estate through their treatment of groundwater under the “absolute ownership theory,” the “ownershipin-place theory,” and the accommodation doctrine. And attorneys have severed groundwater estates prior to receiving judicial or legislative guidance, relying on the policy that Texans have the right to contract. In 2008, a Texas appellate court weighed in and upheld the cogency of deed provisions severing groundwater rights.20 Under the “absolute ownership theory,” a grantor can reserve all groundwater rights when she conveys the remainder of the fee, consequently creating a separate groundwater estate.21 The Texas Supreme Court held that percolating water is a “part of, and not different from, the “soil” and the landowner is the “absolute” owner of it.22 “Water, unsevered expressly by conveyance or reservation, is part of the surface estate.”23 Groundwater is the “exclusive property” of the owner of the surface and “subject to barter and sale as any other species of property.”24

In 2012 and again in 2016, the Texas Supreme Court aligned ownership of groundwater to the ownership of minerals, providing more guidance for landowners.25 In the 2012 case, Edwards Aquifer Authority v. Day, the Court held that land ownership includes a distinct, divisible, and constitutionally protectable interest in the groundwater beneath the surface estate, similar to that of oil and gas.26 The Court further determined the ownership of groundwater to be “in place” by adopting the ownership theory previously applied to mineral estates.27 The ownershipin-place theory establishes that a surface owner, owning a property in fee simple, owns all the minerals and groundwater, fugitive resources, and solid resources below his surface estate.

In 2016, the Texas Supreme Court went a step further in protecting the individual property rights of groundwater owners when it applied the accommodation doctrine to groundwater estates in Coyote Lake Ranch v. City of Lubbock. 28 The accommodation doctrine requires the balancing of interests of the surface estate and the groundwater or mineral owner who carry the dominant easement over the surface estate. The Court again analogized the similarities between groundwater and mineral estates, focusing on the aspects that both estates consist of fugacious and fungible resources, both may be severed from the surface estate, both are subterranean reservoirs, and both are subject to the rule of capture. The Court stated that it had “applied the [accommodation] doctrine only when mineral interests are involved. But similarities between mineral and groundwater estates, as well as their conflicts with surface estates, persuade us to extend the accommodation doctrine to groundwater interests.”29

The Texas Supreme Court’s application of the accommodation doctrine to groundwater in Coyote Lake Ranch was a significant step in the ownership of groundwater estates because the groundwater estate gains a dominant easement over the surface estate.30 Having a dominant easement over the surface estate allows the owner of the dominant estate to drill for water and install pipelines to transport water on the surface estate without gaining permission from the landowner.31 This rationale can be easily applied to the wind estate. As with the other severable interests, wind is another “stick in the bundle” subject to the absolute ownership theory, the ownership-in-place theory, and the accommodation doctrine.

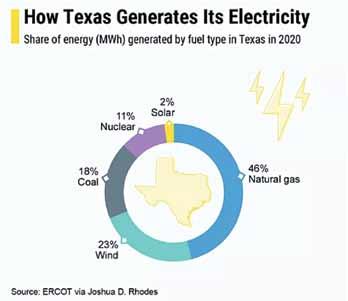

established Rules should apply to severing the Wind estate The first commercial wind turbine was built in Howard County in 1999, and thus wind energy has been harvested in Texas for over 20 years.32 By 2020, wind turbines supplied 23 percent of Texas’s electricity.33

Approximately 1,000 deeds have been filed in Texas severing the wind estate from the surface estate. Severing wind rights in Texas is now a common practice, and property owners need certainty regarding their property interests.35 We know that even severed from the surface, wind rights are valuable in the marketplace.

Texas law has a long tradition of protecting private property rights and encouraging the development of the state’s natural resources.36 Landowners want to continue the power to separately transfer, bequeath, or sell the minerals or groundwater below the land and the wind above the land, giving the landowner myriad options for property ownership and development. The client in the scenario above

could sell the surface estate and keep the mineral estate for the future monies. Or, the client could sell the mineral estate to pay estate taxes. The client could make additional funds from the mineral estate, groundwater estate, and wind estate.

The historical approach the Republic of Texas and the State of Texas took regarding private property rights, the historical analysis of the severability of groundwater estates, and the public policy of creating certainty and stability in the energy sector all support severability of the wind estate.37 The same reasoning that supports severing both the groundwater and mineral estates supports severing the wind estate. The accommodation doctrine has provided a sound basis for resolving conflicts between ownership interests. Similarities between mineral, groundwater, and wind estates, including their conflicts with surface estates, extends the accommodation doctrine to wind production.

All the mineral, groundwater, and wind estates consist of fugacious and fungible resources, and all are subject to the rule of capture. Property ownership theories support the severance of the wind estate. The wind estate has the same right to use the surface that a severed mineral estate and a groundwater estate does. As with groundwater and minerals, there is an element of the rule of capture that may be applied to wind.38 Because wind is a renewable resource, wasting it does not raise the same concerns as wasting oil and gas. Texas will liken wind ownership to groundwater ownership or mineral ownership, following public policy, common practice, Edwards Aquifer Authority, and Coyote Lake Ranch to allow the severance of undeveloped wind rights to protect private property interests of landowners in Texas. Wind development strengthens our economy and transmission system, and there is legal precedent to support its severance.

Shanisha Y. Smith is an associate at Baker & Hostetler LLP where she practices energy and environmental litigation. While obtaining her LL.M in Energy, Environmental and Natural Resources Law, she worked at the Texas Railroad Commission and the Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos during the Mexico Energy Reform. Any opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and should not be construed to be those of Baker & Hostetler LLP, its client(s), or any of its or their respective affiliates.

endnotes

1. PUBLIC STATEMENT, SEC Emblem (2021), https:// www.sec.gov/news/public-statement/lee-statementreview-climate-related-disclosure (last visited Mar 1, 2021); CERAWEEK: ACTING SEC CHAIR SEEKS AN

INTERNATIONAL BASELINE FOR MEASURING CLI-

MATE RISK, IHS Markit (2021), https://ihsmarkit.com/ research-analysis/ceraweek-acting-sec-chair-seeksan-international-baseline-for-.html (last visited Mar 2, 2021). 2. See, e.g., Veronica Penney, How Texas’ Power Generation

Failed During the Storm, in Charts, N.Y. TIMES, Feb. 19, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/02/19/ climate/texas-storm-power-generation-charts.html. “It was across the board,” says Bill Magness, the president and CEO of ERCOT, or the Electric Reliability Council of

Texas. “We saw coal plants, gas plants, wind, solar, just all sorts of our resources trip off and not be able to perform.” Morning Edition, What Really Caused the Texas

Power Shortage, NPR HOUS. PUB. MEDIA (Feb. 18, 2021, 5:10 a.m.), https://www.npr.org/2021/02/18/968921895/ what-really-caused-the-texas-power-shortage. 3. Exec. Order No. 14008 § 201, 86 Fed. Reg. 7619, 7622 (Jan. 27, 2021), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/ 2021/02/01/2021-02177/tackling-the-climate-crisis-athome-and-abroad. 4. K.K. DuVivier & Roderick E. Wetsel, Jousting at Windmills: When Wind Power Development Collides with Oil,

Gas, and Mineral Development, 55 ROCKY MTN. MIN. L.

INST. § 9.01 (2009). 5. See Harris v. Currie, 176 S.W.2d 302, 304 (Tex. 1943) (“The owner has the right to sever his land into two estates, and he may dispose of the mineral estate and retain the surface, or he may dispose of the surface estate and retain the minerals.”); see also Bagby v. Bredthauer, 627

S.W.2d 190, 194 (Tex. App.—Austin 1981, no writ). 6. The Texas Supreme Court has aligned groundwater estates and mineral estates, holding the groundwater estate to be a freely severable estate. See Coyote Lake Ranch,

LLC v. City of Lubbock, 498 S.W.3d 53 (Tex. 2016); Edwards Aquifer Auth. v. Day, 369 S.W.3d 814 (Tex. 2012). 7. See generally Colleen Schreiber, Landowner Attorney Discusses Private Property Rights, TEX. AGRIC. L. BLOG (May 2, 2016), https://agrilife.org/texasaglaw/2016/05/02/ landowner-attorney-discusses-private-property-rights/. 8. See, e.g., Coyote Lake Ranch, LLC, 498 S.W.3d 53; Edwards

Aquifer Auth., 369 S.W.3d 814. 9. See 2 WILLIAM BLACKSTONE, COMMENTARIES ON

THE LAW OF ENGLAND 18 (William Draper Lewis ed., 1902) (discussing the cujus est solum doctrine). 10. See RICHARD KING, KING & CO., 2018 ANNUAL RE-

PORT (April 10, 2019), https://rkingco.com/category/ mineral-owners/. 11. See Moser v. U.S. Steel Corp., 676 S.W.2d 99, 102 (Tex. 1984). 12. Coyote Lake Ranch, 498 S.W.3d at 55 (holding that the accommodation doctrine applies to groundwater); Edwards

Aquifer Auth., 369 S.W.3d at 817 (holding that “land ownership includes an interest in groundwater in place”). 13. See TEX. CONST. art. XVI, § 59. 14. Id. § 59(a), (b); see also Dallas County Levee Dist. No. 2 v.

Looney, 109 Tex. 326, 207 S.W. 310 (1918). 15. College of Geosciences, Texas Water, TEX. A&M UNIV., https://texaswater.tamu.edu/faqs (last visited Feb. 21, 2021) (information for Texans about Texas water). 16. Sun Oil Co. v. Whitaker, 483 S.W.2d 808, 811 (Tex. 1972) (allowing a mineral estate owner to use underlying groundwater for oil production) (citing Fleming Found. v. Texaco, Inc., 337 S.W.2d 846 (Tex. Civ. App.—Amarillo 1960, writ ref’d n.r.e.)). 17. Fleming Found., 337 S.W.2d at 850. 18. Sun Oil Co., 483 S.W.2d at 814 (Daniel, J., dissenting). 19.See Alan J. Alexander, Texas Wind Estate: Wind as a Natural Resource and a Severable Property Interest, 44 U. MICH.

J. L. REFORM 429, 457 (2011). 20. See generally City of Del Rio v. Clayton Sam Colt Hamilton Tr., 269 S.W.3d 613, 617–18 (Tex. App.—San Antonio 2008, pet. denied) (holding that the landowner was entitled to sever the groundwater from the surface estate when it conveyed surface estate via warranty deed). 21. Id. at 617–18 (citing Friendswood Dev. Co. v. Smith-Sw.

Indus., Inc., 576 S.W.2d 21, 25–27 (Tex. 1978); Sun Oil Co., 483 S.W.2d at 811; Texas Co. v. Burkett, 296 S.W. 273, 278 (1927)). 22. Hous. & T.C. Ry. Co. v. East, 98 Tex. 146, 81 S.W. 279, 281 (1904); see, e.g., City of Sherman v. Pub. Util. Comm’n, 643 S.W.2d 681, 686 (Tex. 1983) (“The absolute ownership theory regarding groundwater was adopted by this

Court in Houston & T.C. Ry. Co. v. East, 98 Tex. 146, 81

S.W. 279 (1904).”); Friendswood Dev. Co. , 576 S.W.2d at 25–27. 23. Sun Oil Co., 483 S.W.2d at 811. 24. Texas Co., 296 S.W. at 278. 25. Coyote Lake Ranch, LLC v. City of Lubbock, 498 S.W.3d 53, 55 (Tex. 2016) (holding that the accommodation doctrine applies to groundwater); Edwards Aquifer Auth. v.

Day, 369 S.W.3d 814, 817 (Tex. 2012) (holding that “land ownership includes an interest in groundwater in place”). 26. Edwards Aquifer Auth., 369 S.W.3d at 823. 27. See id. at 831–32. The Texas Supreme Court outlined ownership “in place” for oil and gas in Elliff v. Texon Drilling

Co., 210 S.W.2d 558 (Tex. 1948). 28. See Coyote Lake Ranch, 498 S.W.3d at 64. 29. Id. at 62–64. 30. See id.at 64. 31. See Brent Dore, Teaching an Old Dog a New Trick: Examining the Intersection of the Accommodation Doctrine and

Groundwater Rights Through the Lens of City of Lubbock v. Coyote Lake Ranch, LLC, 3 TEX. A&M L. REV. 853, 882–83 (2016). 32. See John O. King, The Early Texas Oil Industry: Beginnings at Corsicana, 1894-1901, 32 J.S. HIST. 505, 505–06 (1966). 33. Nate Chute, What Percentage of Texas Energy Is Renewable?

Breaking Down the State’s Power Sources from Gas to Wind.,

AUSTIN AM.-STATEMAN, Feb. 17, 2021, https://www. statesman.com/story/news/2021/02/17/texas-energywind-power-outage-natural-gas-renewable-green-newdeal/6780546002/. 34. Ed Browne, GRAPHIC SHOWS WHAT PERCENTAGE

OF TEXAS’ ENERGY IS RENEWABLE Newsweek (2021), https://www.newsweek.com/how-much-power-texasrenewable-coal-gas-wind-turbines-1570238 (last visited

Mar 2, 2021). 35. Mose Buchele, Texas Landowners Take the Wind Out of

Their Sales, KUT (Dec. 11, 2017, 5:01 a.m.), http://kut.org / post/texas-landowners-take-wind-out-their-sales/. 36. Humble Oil & Refining Co. v. West, 508 S.W.2d 812 (Tex. 1974). 37. See Robert Montgomery, Water to Wind: The Path Texas

Groundwater Law Provides to Sever the Wind Estate and

Prioritize Mutually Dominant Estates, 50 TEX. ENVTL.

L.J. 107, 114 (2020) (citing Steven K. DeWolf & Rod E.

Wetsel, Wind Energy Seminar, WIND LAW (Feb. 22, 2012). 38. Terry E. Hogwood, Against the Wind, STATE BAR TEX.

OIL, GAS & ENERGY RES. L. SECTION REP., Vol. 26,

No. 2 at 6 (Dec. 2001); cf. TEX. HOUSE OF REPRESEN-

TATIVES HOUSE RES. ORG., NO. 80-9, CAPTURING

THE WIND: THE CHALLENGES OF A NEW ENERGY

SOURCE IN TEXAS 17 (2008), http://www.hro.house. state.tx.us/focus/Wind80-9.pdf (“‘Capture’ of the wind would be the right to convert or the actual conversion of the wind to [wind] energy.”).