11 minute read

USA New York’s Gastronomic Giants Rise Again

NEW YORK’S GASTRONOMIC GIANTS RISE AGAIN

After the lockdown forced New York’s restaurants to close, the city’s fine dining doyens had to contemplate their very survival. But this is a city that never stops evolving, and while some venues were forced to close their doors forever, others have emerged resplendent.

Text Nathan Thornburgh – Photos Clay Williams

Warm peach with almond and cherry cake, cherry sorbet and frozen vanilla custard, a dessert from Eleven Madison Park.

FROM A CERTAIN PERSPECTIVE, THE QUESTION OF FINE DINING IN NEW YORK IS A QUESTION OF APERTURE: how much of the ungovernable energy of the city do you allow to enter? JeanGeorges Vongerichten at Jean-Georges and Thomas Keller at Per Se went wide open, allowing the life of Columbus Circle to flood in through over-sized windows. Daniel Boulud of Daniel chose to tuck his dining room away and offer something of a refuge, with a jewel box of a dining room set far off the streets, while Daniel Humm at Eleven Madison Park occupies a grand, gallery-like space that is also one step removed from the frenzy outdoors, calmly overlooking the leafy park the restaurant takes its name from. Gabriel Kreuther has a bit of both in his eponymous Midtown restaurant, with a wide outdoor patio across from Bryant Park, combined with a serene interior laced with hints of his home in Alsace. Five chefs, five Relais & Châteaux restaurants: five distinct visions of fine dining in New York City. They were all changed by the lockdown. Some became more civic-minded, some streamlined their operations, some used the time for research and development. But one thing we can report after spending time with these chefs and eating at their restaurants: they are back. And so is the city they serve.

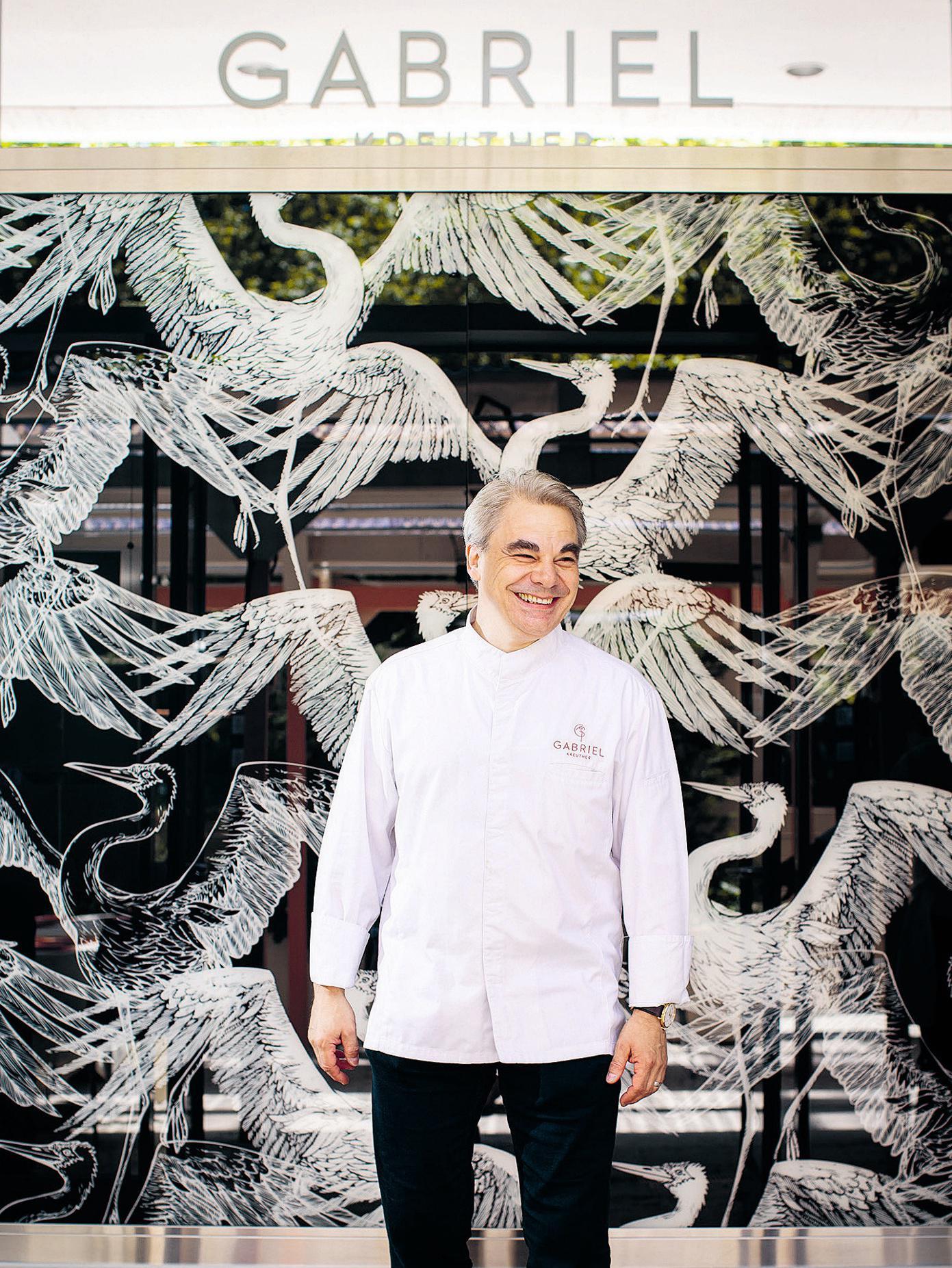

Gabriel Kreuther: an evolving taste of Alsace in Midtown

Lights inspired by the streetlights of his Alsace hometown, Niederschaeffolsheim in France, their ubiquitous stork designs a symbol of Gabriel Kreuther’s homeland. Tiles that nod to Alsatian hearthstones. The leitmotifs of a land far away are threaded throughout his eponymous restaurant. “I always wanted to create my own place,” he says with a laugh. “I just never thought it would be in New York.” But it is, despite the old-world grace notes, the quintessence of a New York restaurant. It starts with the small heresies on the menu. The sturgeon & Sauerkraut tart. The white asparagus cooked in clay with kombu for a gentle wave of umami. Alsace and Bryant Park, of tradition and reinvention: that would have neither sprung to life nor been well

Above: Chef Gabriel Kreuther in his Midtown restaurant, framed by a wall of storks, the symbol of his Alsatian homeland. Facing page, above: Fresh cherry soup, kataifi tuile, cherry marmalade, lime sherbet and Thai long peppercorn. Below: Nostalgia and New York technique mix on the plate as well, as with the white asparagus cooked in clay. CLAY WILLIAMS Photographer “New York is my home. I was born and raised here. There is always something new and interesting around every corner. I loved getting into the kitchens with these chefs and seeing how much love goes into creating the best experience for diners.”

GABRIEL KREUTHER, New York City, USA

accepted in, say, Niederschaeffolsheim. “We are always open to the new,” says Chef Kreuther, “but never going away from quality.” After the pandemic, the challenge of maintaining that quality, and bringing Midtown diners back, were manifold. Also the simple things, like not bumping into each other in the kitchen. “You think a team that worked together for five years could just come back together,” he says. “But things didn’t happen just like that.” As they relearned the ballet of the kitchen, they added delivery, à la carte options, anything for diners’ comfort. They opened one of Midtown’s great sidewalk patios to withstand changing indoor restrictions. And together, along with diners themselves, they relearned what fine dining should be in Midtown Manhattan. And it all leads to this, my favorite bite from my visit: a perfectly balanced summer dish of citrus-cured fluke with avocado, fermented farro and a mandarin vinaigrette. A masterclass in texture and brightness, and not very Alsatian after all.

© DAVID ESCALANTE

Top: Hiramasa rillettes on an ‘everything’ bagel, with pickled pearl onions and Regiis Ova caviar. Below: Chef Thomas Keller’s Californian roots are in constant interplay with New York’s fine dining sensibilities.

Per Se: the view from the top

Table 35 is the best seat in the house at Per Se, or at least in the salon: it’s essentially a loveseat directly facing the floor-to-ceiling windows, fully enveloped in those signature views across Central Park and beyond. It’s Manhattan as aquarium. “I’ve always wanted to [run] an iconic restaurant in New York City,” says chef and proprietor Thomas Keller. “You can feel the sheer spectacular energy of the city. It’s raining, and you feel the thunder. It’s snowing, and you feel a sense of calm as it falls onto Central Park.” The ties to his French Laundry, 3,000 miles/4,800 kilometers away in California, remain strong. It’s in the

PER SE, New York City, USA

Oysters and Pearls, which will forever be on both menus and which remains a triumph of Chef Keller’s mix of double entendre and flawless execution (the ‘pearls’ are tapioca, of course, and the dish is still every bit the delight of savory silk sabayon it has always been). In the kitchen there’s also a two-way live video feed between the two restaurants, and the daily menus of both are taped to the pass. But being in New York City doesn’t just mean that you can legally serve foie gras (Per Se’s foie ‘pastrami’ would be quite illegal in California). It also means having navigated the pandemic in an urban environment, and now taking part in the surge of renewed energy in a liberated city. Throughout, Keller’s convictions about Per Se never wavered: “[Fine dining] has a place in New York. It just does.” As proof, take the success of its newest tasting menu, an upmarket version of the regular prix fixe, featuring classics from Keller’s past and more luxury ingredients. At $850 per person, it is one of the most expensive tasting menus in New York. The view, as always, is included in the cost.

© DEBORAH JONES

Discover our New York City properties

DANIEL, New York City, USA

Daniel: the details that matter

We have an issue with the lights. We need them dimmed a bit for the photos. From his seat on a banquette in the lounge, Daniel Boulud calls out gently to a staffer who can’t figure out how to adjust them. Boulud directs them remotely, to a panel in another room. “Right after the entrance of the door. On your right, open the door. Second button from the top. Good. Press that.” I had come to talk about duck or lamb or maybe that gorgeous art deco bar. But first, he was giving me a lesson in the details. For a chef whose empire has not only survived the pandemic, but has even grown in its wake–one of the newest in the portfolio is the ambitious Midtown seafood restaurant Le Pavillon Boulud has an absurdly intimate knowledge of his flagship restaurant, from every slight inflection in the changing menu to every light switch. This command of the small things has helped him through the plunge of the pandemic. He went from 825 employees to 15, almost overnight. But then he hired the teams back to cook in ghost kitchens. He partnered with Food1st Foundation which has helped produce thousands of meals for healthcare workers and New Yorkers in need. The return of the restaurant was more difficult: “Fine dining was really challenged,” he says. “because [it] requires a lot of staff. And everyone’s staff had been dispersed.”

© BILL MILNE

Now, they are regaining their full swagger, in a Manhattan that is fast filling up again. I ask what dish is most typical of his style of New York fine dining (discreet, luxurious, hidden away from the stress of the sidewalks). He suggests squab–but not for a play on the city’s ubiquitous native pigeon. Rather, he sources it from a small farm in Pennsylvania, and then the rest is, well, pure Boulud: crusted with black pea and Madagascar pepper, and served alongside small, seasonal Easter Egg radishes, the squab legs stuffed with the liver and cooked in a pastilla with Ataúlfo mango and peewee potatoes. It is decadent but earthy, locally sourced but with an eye to the globe. It is Daniel, and it is good to be back.

Top: Chef Daniel Boulud at his flagship restaurant Daniel on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, relies on creativity and attention to detail to convey his vision of French cuisine to his New York City clientele.

Above: Chef Daniel Humm, in the atrium of Eleven Madison Park, took inspiration from New York’s creative community. For constant reinvention, he decided to transform EMP into a completely plant-based experience. Right: Sunflower salad with summer beans, epazote and savory.

ELEVEN MADISON PARK, New York City, USA

Eleven Madison Park: cooking for impact

The New York I fell in love with decades ago was an unhealthy place, a city of chain-smokers, of porterhouse and peated scotch and other scheduled drugs. No wonder people were suspicious of Eleven Madison Park’s new plant-based menu. Being healthy is just not in our culture. But you only need talk to Daniel Humm for a minute to realize that his decision–an earthquake of a resolution that rattled the windows of his business, his reputation, and the entire fine dining world–is driven by many things, but it’s not really about health (“a side benefit,” he calls it). It’s about the planet, about the pandemic. It’s about having barely survived bankruptcy during lockdown, how they used their kitchen as a commissary to feed hungry New Yorkers until they could reopen. And as ‘EMP’, as it’s known, tilted toward reopening, chef Humm channeled the artists he counts as friends and mentors in New York. “It’s beyond an inspiring city,” he says. They used the pandemic as a chance to ‘edit’, to strip out the unnecessary elements in life and work. At ‘EMP’, he thought, people come for the experience, not a specific ingredient. So why did he need meat and animal products? “We were stuck in this sort of expectation of what a Michelin-star meal is supposed to be,” he says. “I just was really excited to propose another way.” That other way is off to a strong start. In three bites of the Sunflower with summer beans, I felt I was already in some other country, some imagined place where this was the traditional cuisine. It’s an earthy bar of summer bean, tomato and candied sunflower seeds, topped with sunflower heart that has been sliced thin like an artichoke, then studded with sunflower petals three ways: fresh, crisp and made into a kimchi. That’s this season. What will ‘EMP’ be doing five years from now? “I know that it will continue to be a work that has a meaning beyond the walls of this restaurant,” says Chef Humm. “With plant-based cooking, we’re now in the second summer season… we have just scratched the surface.”

Jean-Georges: a menu that travels

There is something appropriate about the fact that Jean-Georges Vongerichten’s signature restaurant lies in the shadow of the iconic, stainless steel Columbus Circle globe sculpture. Forget the deep Alsatian roots, the classical French training: the food of Jean-Georges is, in a word, global. You could spin that 30-foot/9 meters globe, smush a finger down on it at random, and you’d likely be pointing to a place he’s been, or where he’s planning to go, or perhaps even where he already has one of his 50 or so restaurants. In the shadow of that globe, I’m tasting tonburi, the ‘land caviar’ of Japan’s Akita Prefecture; then a delicate sashimi of sugar snap peas, mint and buttermilk; then caviar heaped on uni heaped on crisp potatoes like a ziggurat of high-end ingredients. If every good menu is an autobiography, this summer, Jean-Georges is definitely telling the story of his years spent in Asia. “The travel really opened my palate and my horizon. Using chilies, lemongrass, ginger, all those ingredients,” Chef Vongerichten

JEAN-GEORGES, New York City, USA

says. “New York was a perfect canvas for that.”If anything, he says, the pandemic has accentuated demand for that kind of European-Asian-American crossover menu. The previous clients left town. “We have a much younger demographic now,” he says. “People are looking for an experience, to really travel with us.” As the interview wraps, Chef Vongerichten tells me about his next culinary adventure: he was about to head out into Manhattan in search of a different cross-cultural, migratory dish that has become a part of the fabric of the city: a slice of pizza, enjoyed best on the streets.

Above left: Chef JeanGeorges Vongerichten’s flagship restaurant, Jean-Georges, adjacent to Central Park, draws on his Alsatian roots and his years in Asia for its palate. Above right: Madai sashimi with market peas, lemon balm and buttermilk emulsion.