CELEBRATING PICASSO’S LEGACY

IMPORTANT WORKS ON PAPER MARCH 17 – MAY 6 . 2023 IMPORTANT WORKS ON PAPER

LewAllenGalleries

LewAllenGalleries

IMPORTANT WORKS ON PAPER MARCH 17 – MAY 6 . 2023 IMPORTANT WORKS ON PAPER

LewAllenGalleries

LewAllenGalleries

“[Picasso had] a depth of understanding and insight into the inwardness of things.... doing very exceptional things of a most abstract psychic nature.”

– Marsden HartleyFifty years after his death, the shadow of Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) continues to tower over the world of art. Recognized as a seminal artist across media and time, Picasso produced an astonishing variety of work in painting, sculpture, and collage. His figural prints are particularly significant as they trace the intriguing intersection between Picasso’s life and art, offering a glimpse into the artist's inner thoughts. Picasso used the figure as a vessel to showcase his formal innovations, such as mark-making, line, form, space, and an experimental approach to process and media. Picasso’s distortion of form and figure reveals an artist in the process of enormously complex personal reflection, which left an indelible mark on Modernism.

This celebratory exhibition covers the span of Picasso’s printmaking oeuvre, featuring works from early in his career to later works such as Portrait de Jacqueline de Face I, a striking linocut portrait of his second wife. Exploring themes of identity and interpersonal relationships, Picasso’s prints frequently feature depictions of his friends, lovers, and wives. Providing insight into Picasso as both an artist and man, some prints explore the relationship between artist and model, while others contemplate his alter egos. Picasso’s prints provide a pictorial chronicle of his life, moods, loves, passions, and insecurities, and distill the relationship between his art and autobiography.

In the mid-1930s, Picasso made a handful of etchings that center around the bullfight, depicting a bull, a horse, and a beautiful young female toreador who distinctly resembles his mistress at the time, Marie-Thérèse Walter. The bullfight was a passion of the artist throughout his life, and these etchings were not his first foray into the theme—as noted by Museum of Modern Art curator Deborah Wye, a picador was the subject of Picasso’s first print of 1899 and he explored the bullfight throughout his career. The subject of such works range from straightforward gestural expressions of the drama and action of the conflict to highly metaphorical images that explore his private inner life, as in La Grande Corrida, avec Femme Torero.

In 1934, Picasso was in his mid-50s and was likely experiencing a sort of mid-life crisis. His relationship with his wife, Olga Khokhlova—a former ballet dancer from Ukraine—was extremely strained and had been so for years. Though a striking beauty in her youth, she was now somewhat ravaged by years of health problems, poor diet, anxiety attacks, and obsessive coffee-drinking. Meanwhile, his long-term liaison with his mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter, was beginning to disintegrate and she would soon reveal to him that she was pregnant (according to Picasso scholar Brigitte Baer, it was just before Christmas of 1934). Though Picasso biographer John Richardson suggests that Olga may have been aware of the affair as early as 1929 and had come to accept it, the truce was tenuous and Picasso feared that his wife’s wrath could descend at any moment. In addition to his romantic entanglements, Picasso had been struggling with self-doubt as a result of mixed critical responses to his mid-career retrospectives in Paris and Zurich in 1932. He was beginning to feel that his life was spinning out of control.

In La Grande Corrida, avec Femme Torero and a number of other similar etchings of the period, particularly Femme Torero. Dernier Baiser? (Bloch 1329) and Marie-Thérèse en Femme Torero

(Bloch 220), Picasso plays out the terrible pressure he was under in a grand allegory of the bullfight. As interpreted by a number of scholars, Picasso used the figure of the bull to represent himself; while the female toreador, who traditionally rides on horseback, represents his lover Marie-Thérèse. The horse stands for his wife Olga. Among Picasso’s prints in this vein, each of which are major prints in the history of art, La Grande Corrida, avec Femme Torero stands as the most ambitious and intense. Wye describes it as a “tour de force of etching [that] veers toward total abstraction in its rendering of the fury of the bullfight.” In this heavily worked and oversized etching, Picasso conveys anguish, chaos, fury, violence, and death. The jumbled limbs, overwhelming detail, overlapping elements, and energetic vectors that cut through the swirling composition add up to a level of intense visual stimulation that threatens to overload the viewer’s senses. Thus we struggle, like the figures in the image, to make sense of the scene.

Even with careful study it is difficult to entirely sort out the figures in the central vortex of this image. There seem to be at least four: a matador at left, a bull at center, a twisted female toreador above the bull, and a horse upon which she rides at right. The bull, whose impassioned charge is indicated by clouds of dust below his hooves, snorts in a rage as he lunges for the horse, who responds by standing on her hind legs with an expression of rage and aggression. The female toreador at center, who resembles Marie-Thérèse, seems a victim of the situation—she has been thrown from her mount and her body twists throughout the composition as if caught up in a whirlwind. Her breasts are exposed and her neck is bent in an unnatural and perhaps fatal position. The matador, running and raising his arms, and the faceted angular lines at left, which resemble broken glass, add to the general drama and intensity of the scene. Behind the central figures are several spectators sitting in the arena, including one at the far right that is clearly a representation of Marie-Thérèse—she stands out as an aloof and calm presence amidst the chaos and violence. From her forehead begins a javelin that strongly divides the composition in a diagonal, ending between the shoulder blades of the bull. As the weapon would have been used by the mounted female toreador at center, a

by the mounted female toreador at center, a connection is implied to both representations of Marie-Thérèse. Likewise, its role in the demise of the bull underscores the lovely young woman’s role in the demise of her lover. Picasso’s two representations of her also suggest conflicting roles: indifferent observer, innocent victim of circumstance, and perpetrator of mortal wounds.

Technically, this etching represents a magnificent level of achievement in line etching as well as perspective. In prints like this we can see how Picasso brings his iconoclastic approach to depth of field—which he began with his invention of Cubism with Georges Braque in 1907—to a new level.

Abandoning traditional one- or two-point perspective, Picasso suggests depth in this composition through the sophisticated manipulation of line. By varying the tone and allowing selected elements to weave in and out of the composition, we have a sense of a foreground, middle ground, and background, though he freely plays with these zones by moving his figures in and out of them, changing the “proper” overlap of limbs and body parts, and distorting scale when it suits his purpose. As a result, the figures weave in and out of one another’s space in a dense and surreal world that more accurately conveys a sense of emotional intensity and chaos. Likewise, we feel almost suffocated by the intensity of the situation as we look. The entire plate is filled with a dense cover of figures in the backdrop of an arena —we have no sense of atmosphere or sky, and there is no escape. All of this is accomplished with masterful control over the etching process—each line is distinct and clear.

Picasso anticipated the implosion of his personal life by several months, even a year. In July of 1935, Olga learned that Marie-Thérèse was pregnant and promptly left Picasso, taking their teenage son, Paulo. Picasso’s reputation in the bourgeois social circle he shared with Olga suffered a severe

blow, and he was anguished over the loss of his son. After a difficult legal process, Picasso and Olga determined to remain married but separated. The stress of these events caused him to give up making art for a period; he instead devoted his energies to writing surrealist poetry. In addition, Picasso’s interest in Marie-Thérèse waned once she was a mother, though he took care of her and their daughter Maya throughout his life. Picasso would later refer to this phase as the darkest period in his life. In etchings like Marie-Thérèse en femme torero (Bloch 220), it is almost as if he could clearly see the outcome ahead but was unable to stop it.

Like a number of prints from this period, including the Vollard Suite, the printing and publication of this etching is complicated. After a small number of proof impressions were taken in 1934 (signed), an edition of fifty on laid Montval was printed in April of 1939 by Roger Lacourière, a few months before death of Vollard (who was Picasso’s publisher). The unsigned edition was then purchased by Fabiani, Vollard’s protégé and executor, along with a number of other paintings and editions. Georges Bloch acquired a few impressions eventually, and these were signed, but a majority of the impressions remained unsigned and were not released until Picasso’s death in 1973.

In the autumn of 1934, Pablo Picasso produced Minotaure aveugle guidé par Marie-Thérèse au Pigeon dans une Nuit étoilée, which is the 97th of the 100 etchings from the Vollard Suite. This masterful print depicts a starry night sky, the sea, and a blind Minotaur with his arm resting on the shoulder of Marie-Thérèse, who is represented as a small girl holding a dove. Additionally, there is a vessel and various sailors in the background. The image raises questions about the direction the Minotaur is headed in and the significance of the dove. Each element in the composition is rife with symbolism.

Picasso frequently used the Minotaur as a representation of his alter ego, symbolizing humanity's subjugation to primal desires. In this print, Picasso portrays the Minotaur as vulnerable, with the little girl as his guide. This portrayal is significant, given the ongoing affair between Picasso and Marie-Thérèse. When Picasso met Marie-Thérèse in 1927, she was only seventeen, and their seven-year-long relationship was a secret, taboo affair. At the time of this work’s creation, Marie-Thérèse had recently informed Picasso of her pregnancy, adding further complexity to the situation. Although Picasso did not want to end things with Marie-Thérèse entirely, he had begun spending time with Dora Maar, and Olga, Picasso's wife who, had left him upon learning of Marie-Thérèse's pregnancy.

During this tumultuous period, Picasso channeled and expressed his emotions in his artwork. The image's darkness mirrors Picasso's inner turmoil, reflecting his anguish, confusion, and his desire to maintain the status quo. Despite the complexity of their relationship, Picasso and MarieThérèse's affair continued, and the artwork marks the end of their most passionate chapter.

Minotaure aveugle guidé par Marie-Thérèse au Pigeon dans une Nuit étoilée (S.V. 97, B0225), 1934 Aquatint, drypoint, scraper, and burin on paper, image size: 9.75" x 13.75", sheet

Minotaure aveugle guidé dans la Nuit par une Petite Fille au Pigeon (S.V. 96, B0223), 1934

Etching on paper, image size: 9.5" x 11.75", sheet size: 13.38" x 17.75"

Though based in Greek mythology, this image is more surreal than narrative. Picasso created this etching in late 1934, along with a number of similarly complex and dark compositions from the Vollard Suite, including the “Blind Minotaur” images, plates 94 through 97 (Bloch 222, 223, 224, and 225). At right is a figure resembling a Sphinx or perhaps the Oracle of Delphi (a.k.a. the Pythia), perched on a column. To her left is a man with generalized Greek features, offering a glass of wine to the mythical creature. On the other side of the composition stand a masked man and woman. Noted Picasso scholar Brigitte Baer offers her own analysis of this image in Picasso the Printmaker: Graphics from the Marina Picasso Collection (Dallas Museum of Art, 1983, 92-3) in terms of Greek mythology interwoven with Picasso’s personal life and the issues that may have been preoccupying his thoughts at the time, but this is a mysterious and complex composition that offers multiple interpretations. Overall, it is dreamlike in manner that is similar to many images by Picasso’s Surrealist contemporaries; though he was not intimately connected with the movement, he was close with many of its leaders and incorporated some of their ideas into his work of the 1920s and ‘30s.

In terms of technique, this etching is a milestone in Picasso’s printmaking—one of handful of initial forays into the use of aquatint, which he would master with the assistance of master printer Roger Lacourière. To create the image he first painted the figures on the plate using varnish, which blocks the subsequent action of the acid on the plate, thus leaving these areas white. In order for a tone to print the plate must be evenly dusted with rosin powder that is baked onto the plate; this was done either before or after Picasso painted the varnish. The minute spots of adhered rosin also resist the acid, creating a cavernous and pocked surface that will later hold ink. Before etching, Picasso also went in with a needle and scratched out a few fine lines within the figures, thus exposing the

metal to the plate. As noted by Baer in Picasso the Engraver: Selections from the Musée Picasso, Paris (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1997, 73) Picasso painted the acid on the plate in order to etch it rather than dipping it in a bath of acid. The result is a subtly mottled background instead of an even tone.

As discussed by the scholar Lisa Florman in Myth and Metamorphosis: Picasso’s Classical Prints of the 1930s (Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 2000, 88-9), Picasso may have had Francisco Goya’s Los Caprichos of 1799 in mind when he began work on the Vollard Suite, which she argues is Picasso’s own contribution to the tradition of the capriccio. If so, this plate can be seen as a reference to plate 19 of Goya’s suite, Todos caerán (All will Fall), which has been interpreted as an admonition against lust for women and its potential pitfalls—a message that certainly would have rung true for Picasso at a time that he was grappling with the news that his young mistress was pregnant. The bird-woman at the upper right of Goya’s image closely resembles the mythical Sphinx figure that Picasso references here. Florman also notes that Picasso’s choice of aquatint indicates an homage to Goya as well, as the elder artist remained the undisputed master of the technique.

The current impression is one of fifty deluxe impressions with large margins printed on Montval laid paper watermarked “Papeterie Montgolfier à Montval,” outside of the edition of 260 (there was also a small edition of three on vellum). It was printed by Roger Lacourière in late 1938 or early 1939. The untimely death of Ambroise Vollard in the summer of 1939 delayed their commerce until 1948 when the prints were acquired by dealer Henri Petiet through the Vollard Estate.

When Picasso created this abstracted portrait of his mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter, he had been involved in an intense and covert affair with her for over seven years. While Picasso initially shied away from literal depictions of his mistress, at this point his inhibitions have faded, and she is to be found everywhere in his art, both in group scenes and in portraiture. Though a majority of Picasso’s etchings from the 1930s center around Classicizing scenes in which she is featured prominently, he also made several abstracted portraits of Marie-Thérèse during this period.

This particular engraving was included amongst the one hundred plates of the Vollard Suite, though many of Picasso’s heads and busts of Marie-Thérèse stand alone. It is the only true portrait of her in the Suite (she is more generalized, idealized, or symbolic in other plates) and it is also set apart in its style. While he used a loose and flowing line in a majority of the images, here he employed a more rigorous geometric approach that borrows elements from Cubism, the breakthrough movement Picasso founded with Georges Braque earlier in his career. By the mid-1930s, when this print was made, Surrealism was the dominant force in the Parisian art scene. Picasso was friends with many of its leaders, but he generally distanced himself from the movement and followed his own path during this period. Still, he was not averse to borrowing from their ideas when it suited his purpose.

Picasso mingles elements of both movements in this image. The fragmented and flattened space that defined Cubism is apparent in the armchair upon which she sits, which is shown from a number of angles. In addition, its outer edges establish an illusionistic frame that focuses our attention on the subject. The overlapping lines in Marie-Thérèse’s face suggest volume, movement and the passage of time—the influence of Surrealism resides in Picasso’s choice of subject: a dreaming woman who is both awake and asleep. As noted by Museum of Modern Art curator emerita Deborah Wye, this, “duality conjures up realms of the conscious and unconscious, central preoccupations of

the Surrealists at this time.” Though Picasso’s work is not intimately connected with the Surrealist movement, he was close with many of its leaders and incorporated some of their ideas into his work of the 1920s and ‘30s.

The current impression is one of fifty deluxe impressions with large margins printed on Montval laid paper, outside of the edition of 260 (there was also a small edition of three). It was printed by Roger Lacourière in late 1938 or early 1939. The untimely death of Ambroise Vollard in the summer of 1939 delayed their commerce until 1948 when the prints were acquired by dealer Henri Petiet through the Vollard Estate.

Femme au Fauteuil songeuse, la Joue sur la Main (B0218), 1934 Engraving on paper, image size: 10.88" x 7.75", sheet size: 17.5" x 13.25"

Picasso created over 150 color linoleum cuts during the 1950s and 1960s, and among these, his portraits of his second wife, Jacqueline Roque, are particularly noteworthy for their striking colors and artistic merit. Picasso's use of color in these linoleum cuts was new, as he had only tried monochromatic cuts in the 1930s. He and Jacqueline met at the Madoura pottery workshop in Vallauris, where he was working on limited edition pottery. They were married in 1955, after the death of Picasso's first wife.

In his portraits of Jacqueline, Picasso emphasized her distinctive features, such as her dark eyes, arched eyebrows, and high cheekbones. These became a staple in his later portraits. Some of Picasso's famous works, such as the series inspired by "The Women of Algiers" by Eugène Delacroix,

This linocut print is dedicated to Norman Granz, who enjoyed a close friendship with Pablo Picasso during the latter years of the artist’s life. Granz was an American jazz record producer and concert promoter. Dedicated to anti-racism and combating segregation in the United States, he was responsible for some of the century’s most iconic recordings, including the 1956 Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald rendition of Cheek to Cheek.

After discovering modernism, Granz began to collect French Modern art — Picasso, Braque, Klee, Léger, and Dubuffet. Granz applied the same simple candor to art as he did to music, saying, “I don’t think you have to understand a painting. I don’t think you have to understand a piece of music. I think you need to listen to it or look at it.” By the late 1960s, he had established a significant collection. Picasso appreciated Granz for his unique style of collecting and for keeping up with his changing art forms. Granz was also one of the few collectors allowed to drop by Picasso's studio without a prior appointment. During his lifetime, Granz founded five record labels, and the last one was named “Pablo Records,” after his friend Picasso. In late 1969, Granz’s love for Picasso led to him taking out a full-page open letter in the weekly L’Express, in which he urged the French government to establish a dedicated museum in Paris to the artist. Picasso, amused by this, told them not to waste the money. Their friendship continued until the artist’s death in 1973.

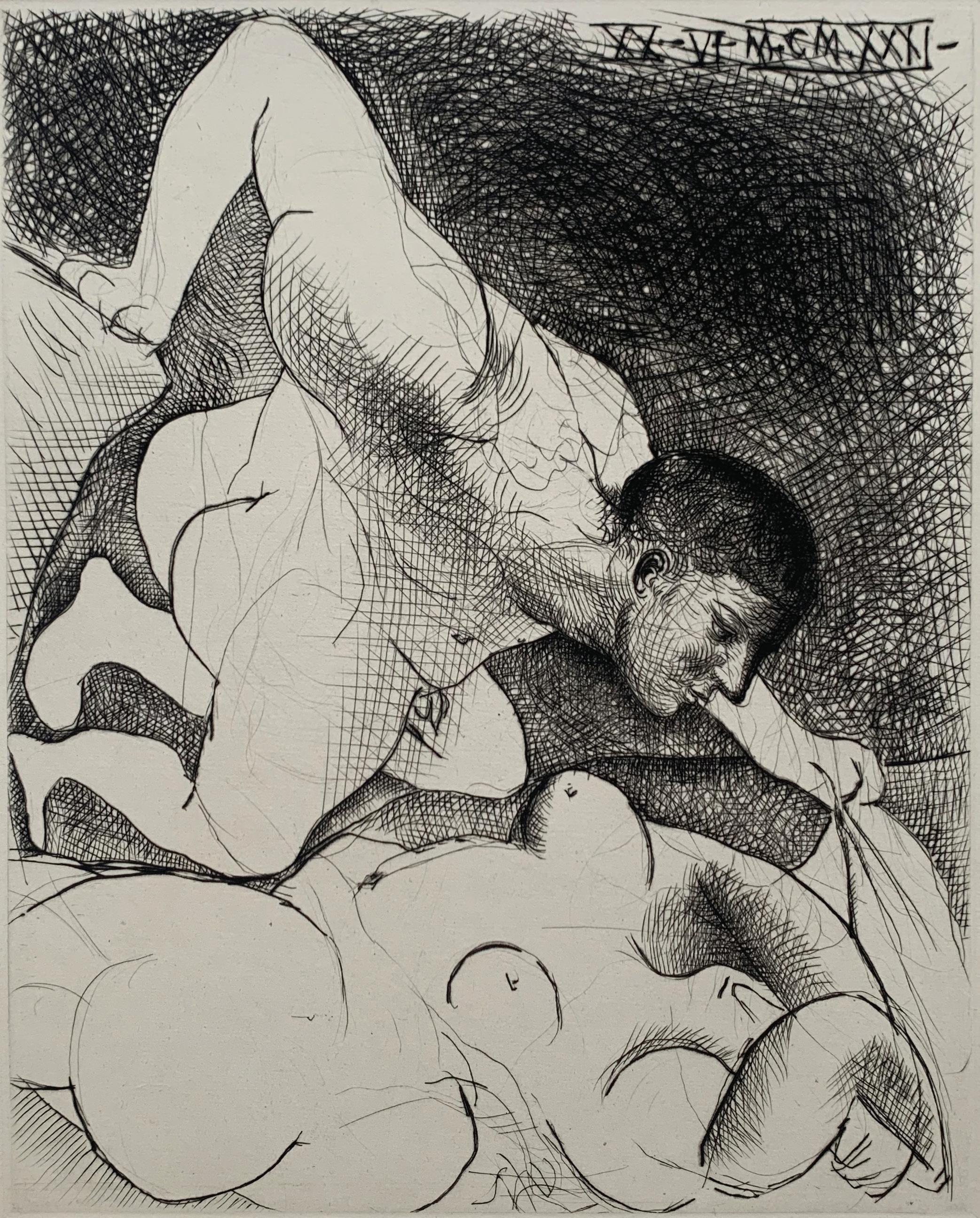

In the Vollard Suite, a recurring theme is sleepwatching. Homme dévoilant une Femme depicts a youthful male who gazes upon a sleeping woman while lifting fabric from her body. The artwork, executed in drypoint on paper, portrays the illuminated figures emerging from a dark and richly textured background. Although the young man does not physically embrace the woman, their contorted bodies and the palpable tension between them evoke a sense of sexual desire. The female figure, identifiable as Marie-Thérèse Walter through her pose and the voluptuousness of her body, appears as a reflection of the youth's desires. If Picasso is identifying with the male character, he could be seen as projecting an idealized image of himself as a younger man whose age is more aligned with that of the female subject he admires, rather than his actual age at the time of creating the piece. This intimate scene is set in an indefinite location, contributing to the artwork's dreamlike quality.

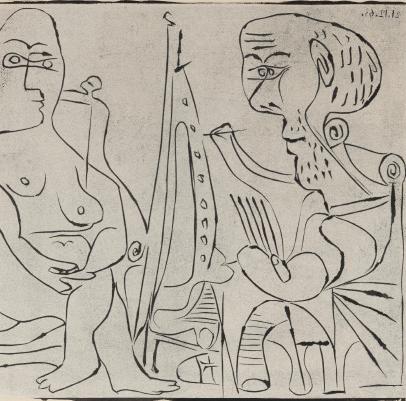

Exactly 90 years before this exhibtion, between March 14–April 11, 1933, Picasso etched 35 prints on the theme of the sculptor’s studio. This etching is a part of a number of images within the Vollard Suite which are set in a sculptor’s studio. In 1933 and 1934, Picasso created plaster sculptures and etchings of his model and mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter. In these works, and through a variety of means, Picasso reflects on the shifting boundaries between art and life, fantasy and reality.

Modèle, Tableau et Sculpture (S.V. 43, B0151), 1933

Etching on paper, image size: 10.38" x 7.5", sheet size: 17.4" x 13.38"

In 1909, Joan Gaspar Xalabarder founded Sala Gaspar in Barcelona, primarily as a frame shop. However, over time, the establishment began showcasing art pieces from Xalabarder’s artist friends. After the Spanish Civil War, in 1955, the Gaspars developed a friendship with Pablo Picasso and hosted the very first Picasso exhibition in Spain. From then on, Picasso exhibited regularly at the Sala Gaspar, always in October. This original lithograph is a poster advertising Picasso’s drawings in April of 1961.

The connection between Picasso and the Gaspars paved the way for exhibitions featuring other noteworthy artists, including Joan Miró and Alexander Calder, and established Sala Gaspar as a vital cultural and social center in Barcelona. Patronage from the Gaspar family enabled the creation of Barcelona’s Picasso Museum in 1963 – the only Picasso museum founded during the artist’s lifetime. Today, Sala Galpar continues to be recognized as an art gallery of important historical significance.

Throughout his life, Picasso had a deep affinity for the dramatic arts. He avidly explored theatre –both in his artwork and real life as a spectator and collaborator. Picasso’s compositions often feature harlequins and actors or invoke the mask, a traditional device for delving into the complex interplay between art, illusion, and reality. After befriending writer Jean Cocteau, Picasso became involved behind the scenes creating costumes and set design for Jean Cocteau and Erik Satie's ballet, Parade.

Set on a light-filled theatre stage, La Répétition depicts a group of nude actors rehearsing a scene with two onlookers obscured in the dark background. The lead actress has a stoic look, while she holds up a grinning mask in front of her face. The primary actor also has a stern expression. The implication is that the actors are literally wearing different personas before the audience, concealing their identities and true nature. In the back of the scene are three women, but only the central figure holding a tambourine appears to be truly alive and dimensional. The other two woman and the musician playing bugle behind them are rendered quite flat, and they blend into the background. Conspicuously referencing Greek antiquity, this print highlights the ongoing relationship between illusion and reality in Picasso’s oeuvre.

The close relationship between the world of bullfighting and Picasso’s oeuvre is without question. From his childhood days in Málaga, where his father often took him to the bullring, he was greatly fascinated by the national sport. The artist used the bullfight as a metaphor, depending on its context: as a comment on fascism and brutality, to convey the strength of the Spanish people, as a symbol of virility, or as a reflection of Picasso’s self-image. Depicted here in the context of a bullfight, the bull appears as a powerful presence with the eyes of the crowd watching as the animal faces off with the picador. A masterfully executed sugarlift aquatint, Le Picador blessé showcases Picasso’s skill in an uncommonly used medium.

Le picador blessé (Ed. of 50), 1952 Aguatint on paper, 20.38" x 26.18"