Transcendence from the Shadows

Fritz Scholder | Transcendence from the Shadows

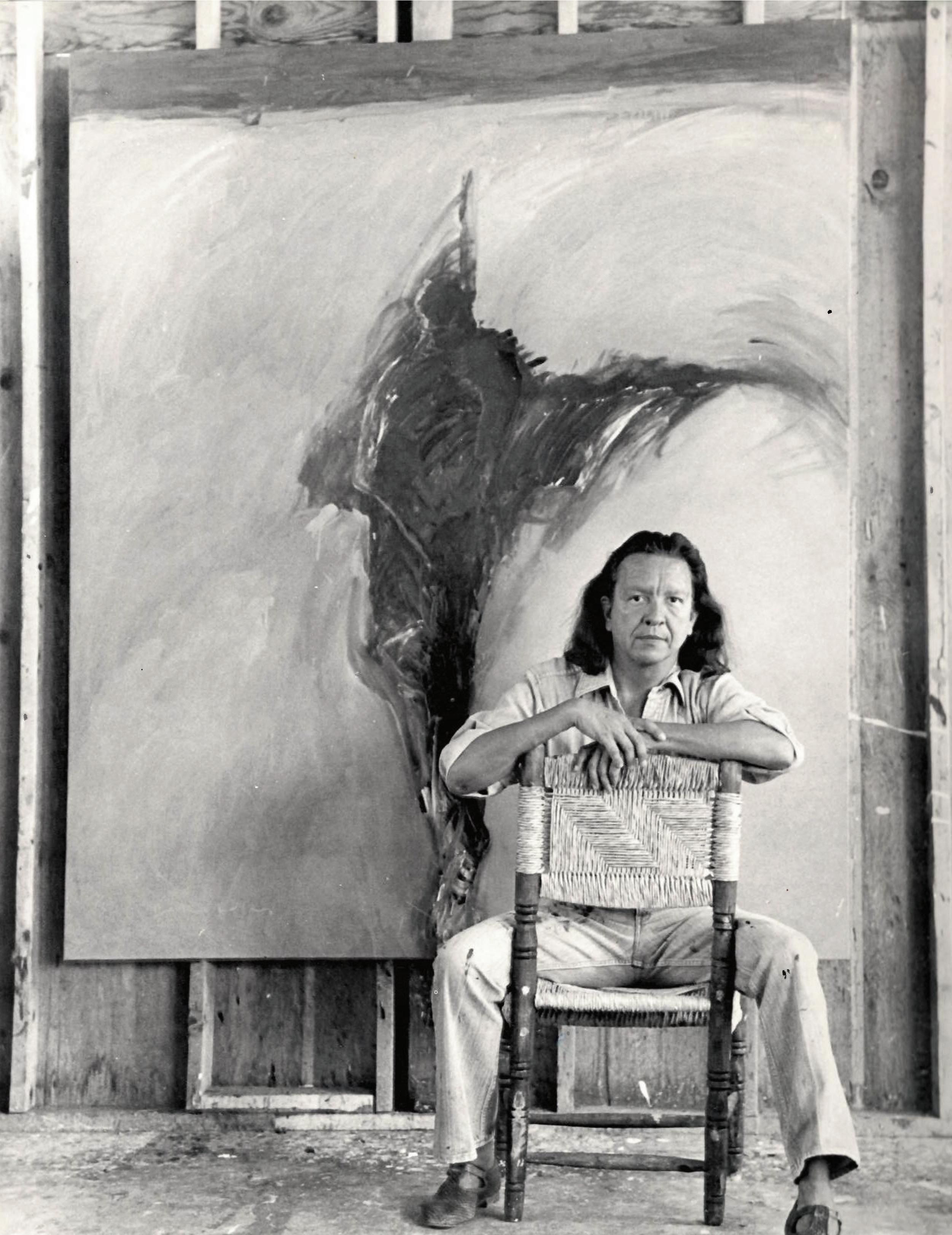

As a major figure in American art history, Fritz Scholder (1937-2005) is pivotal for his provocative and groundbreaking reinvention of the portrayal of Native Americans in contemporary art. Scholder became famous for his de-romanticized, expressive paintings, bronze sculpture, and works on paper rejecting the stereotyped clichés of traditional Indian art and, instead, depicting the contemporary reality of Native People in the United States. Scholder was determined to “paint the Indian real, not red”. This resolve to portray the “New Indian,” beginning in 1967, was hugely controversial, but made him an art celebrity and financially successful.

Beyond subject matter, however – and as this current LewAllen exhibition entitled “Transcendence from the Shadows” profoundly illustrates – Scholder is an artist whose aesthetic tendency has always been rooted in his own kind of abstracted expressionism. This aspect of his career is highlighted in the current exhibition by the inclusion of American Portrait No. 1 and a companion work American Portrait No. 3, both quintessential examples of a series of paintings begun by Scholder in 1980, as well as The Meeting, an extremely important early painting by the artist from 1960 that became an iconic prototype for his famous Dream Series and Monster Love paintings and related works in his later Vampire Series and Fallen Angel Series.

All three of these paintings have been retained in Scholder’s personal collection and his estate following the artist’s death in 2005. As the New York Times noted in his obituary, Scholder was famous for keeping his personal favorites from his series. (All three works appeared in the major Rizzoli book entitled Fritz Scholder (1982). American Portrait No. 1 and The Meeting were both exhibited in the 2008 Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of the American Indian two-city retrospective and published in the accompanying catalog entitled “Fritz Scholder: Indian/Not Indian.” These works are now being made available for acquisition for the first time since the artist’s death as part of this LewAllen exhibition.

Scholder expressly declared that the American Portrait series would represent an expansion beyond his preceding primary interest in the American Indian series into such subject themes as women figures, shamans, dreams, animals, the mystical and others. His pursuit of these new directions seemed to spring from a desire to tell deeper, richer visual stories and, in the artist’s own words, “I had made my statement on the Indian as a subject, and was ready to move in a more universal and mystical arena.” (Scholder would return to the subject of Indian painting in the 1990s.)

The figures in the American Portrait series are characterized by their bold colors, expressive brushstrokes, and distorted features, which give them a feeling of raw energy and ethereal and emotional intensity. Scholder often used unusual color combinations, such as bright pinks and greens, to create a sense of dissonance and tension in the paintings. His prowess as a colorist is superb and, like Matisse, he “dangerously harmonized colors that shouldn’t be capable of coexistingβ on the same canvas.”

Much of Sholder’s work features the non-naturalistic, warped portrayal of the figure—inspired by the art of his heroes, Bacon, Munch, and Oliveira—that had always been the central touchstone of his art, as he explored themes of identity and psychology that are seen equally in his Indian series, examples of which are also included in this exhibition. But with this new direction that began in the American Portrait series, figural distortion became a means of aesthetic and spiritual disruption—rather than sociological, as in his Indian series—delving beyond merely appearances towards deeper mysteries of the psyche.

Perhaps the greatest animating force of Scholder’s powerful work – its extraordinary capacity to enlist the nonconscious mind of its viewer and attain a remarkable sense of historical gravitas – is its constant sense of paradox and inscrutability. Scholder is clearly one of the art world’s greatest masters of the use of mystery in his work. By means of pictorial distortion, exaggeration, darkness and shadow, he creates forms and atmospheres that synthesize in his paintings and works on paper beguiling and perplexing interpretive riddles.

It is here, in the mystery, in the shadows, that the magic of Sholder’s work most resides and does its transcendent work. Indeed, as the great art critic, Edward Lucie-Smith, has noted: “Scholder regards painting as a magical act—specifically as a shamanistic activity…” and has compared Scholder’s with the work of Edvard Munch about whom he has said the two are “soul mates.” Lucie-Smith says that this aspect of Scholder’s work, like that of Munch’s, “represents the exact moment from outer to inner, from art as would-be objective representation to art as the unashamed bodying forth of subjective states.”

The salience of this interiority is illustrated, for example, in the original lithographic work on paper featured in this exhibition, Dream # 4, that depicts the apparitional forms of a couple’s embrace in the darkness. Emanating from the shadows is a transcendent feeling of emotion that goes beyond the realm of sense experience. The work is a classic example of how Scholder uses mystery to supplant reality in order to express the spirit of form rather than the form itself, to elicit in his viewer an experience in the spiritual realm of love rather than merely the act of love making.

In the major painting from 1960 entitled The Meeting, a form of a couple’s embrace is silhouetted floating against a blue and white faceted background. The ambiguous figures appear to be melding together and calls to mind Munch’s famous painting The Kiss which similarly elevates the mystery of abstract forms into an art of spiritual transcendence. This painting became an important precursor for Scholder’s enduring artistic concerns with examining romantic relationships in various ways. These range from warm and passionate to aggressive and threatening, but always engaged by Scholder with deep aesthetic intensity, the genesis of which is evident in The Meeting.

Although the forces that drove Scholder's enormously diverse body of works – from Native imagery to the darker more archetypal figures and abstracted narratives in series such as the American Portraits, Fallen Angels, Dreams, Vampires, Monster Love, and others – are as complex and inscrutable as the artist himself, it is safe to say that a constant throughout it was the drive to confront pain and search for meaning.

In his early groundbreaking Native American works, Scholder “broke the mold” by revealing the reality of Indian suffering and real-world experience struggle trying to live between two cultures, not able to remain fully in the one or thrive in the other. He used the distortion of human features to great effect in these works in order to convey the idea of “otherness”, alienation, and the ugly reality of torment that had befallen indigenous people.

As one commentator described it “Indians became Scholder's symbol of human existence under compromised conditions and allowed him to examine the human capacity to either cope with the pressures of a psychic split or crash out.” (William Peterson, critic and art historian.) One curator at the National Museum of the American Indian said of the artist: “I believe we have to look at Scholder as a vehicle to look at the complexities of condition of indigeneity today.” Perhaps Scholder’s particular ability to be such an adept vehicle and to evoke an acutely transcendent power from the distorted depictions of Indian figures with blurred features might be related to his own confusions and struggles with personal identity.

Scholder was one-quarter Luiseño, a tribe inhabiting Southern California. However, he had not been raised in a tribal community and he “grew up in a house without a single Indian object in it.” He recognized the incongruous nature of the two cultures he shared and credited the agitation he felt throughout his life about being “Indian, Not Indian” with instilling a creative tension that allowed him to use the unsettling effects of paradox, mystery, and darkness in his own journey of discovery and to communicate his passion about ideas, new ways of looking, and thinking.

Scholder truly was a shaman of paradox and contradiction. He knew how to inflame curiosity in others and set the imagination on fire by the use of perplexity – conjuring in his images traces of the recognizable that is never fully present. He is a master of the liminal, alternating between light and dark, exulting in the glorious mystery of the shadow. His figures with their distortions and blurred features become allegories of the ineffable mysteries of life, identity, love, death, and every sort of meaning human kind burns to know. And in that shadow, in that mystery, Scholder gave his work the power of revelation – indeed, of magic. It is here his shamanistic genius allows for a mode of experience in the realm of ambiguity that approaches a kind of transcendence.

KENNETH R. MARVEL

Indian Encampment after Blakelock (Second State) (AP), 1977 Original lithograph on paper, 10.25"

American Family, (Ed. 79/115), 1974

Entrance A (Entrance to the Kiva), 1995 Monotype, 36" x 27.25"

Indian with Rattle, n.d. Monotype, 35.63" x 27.5"

American Warrior N° 3 (Ed. 12/75), 1981

Mystery Woman on the Porch, 1968 Oil and acrylic on canvas, 30" x 40"