Hunting’s heritage SUPPLEMENT TO THE MOSCOW-PULLMAN DAILY NEWS ENTHUSIASTS ARE WORKING TO KEEP OUTDOOR TRADITION ALIVE A special publication of OUTDOORS SECTION | FRIDAY, OCT. 14, 2022

If there’s a theme to the 2022 Hunting Edition, it’s the richness of the heritage and traditions of hunting and the growing effort to welcome more people into the fold.

For example, inside you will find four features on the First Hunt Foundation, an organization founded by Rick Brazell, of Kamiah, who is a former supervisor of the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest. The aim of the group is to mentor new hunters in an effort to keep the activity thriving. I first learned of the group before

it took flight. Brazell told me during an interview back in 2014 that he wanted to start an organization with an emphasis on recruiting new hunters. The group now operates in 38 states with more than 800 volunteer mentors and may hit 1,000 in the coming months.

You will also find a feature on Justin Townsend and his wild game cooking website Harvesting Nature. Every year I try to include a food feature in the Hunting Edition. After all, the organic meat that is the reward of a successful hunt is the

reason most of us take to the field each fall. Townsend, a chef who learned to cook in New Orleans, shares two recipes I’m eager to try.

There’s also stories on the state of the region’s deer and elk herds and populations of upland and migratory birds.

So whether your fall season started with an archery hunt, or you’re a rifle hunter who’s just getting started, I hope you’ll find the edition of interest.

Good luck out there and may you end the season with a full freezer.

— Eric Barker

— Eric Barker

is clear:

OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 20222 Mission

creating hunters Reality TV star happy to bring new hunters into the fold Operation Save Hunting 7 Building a network of support for new hunters ........................................... 8 Wild game gourmet ........................................ 10 Harder to target .............................................. 12 In the Blues, a tale of two elk populations ...... 13 Small pests a big concern for Idaho moose 14 Corn and other rich food a death sentence for wintering moose 15 Role reversal: Elk pursues hunter ................... 16 Wet spring a mixed blessing for game birds .... 18 Duck surveys conducted for first time in 3 years 18 Inside outdoors 19 © 2022 TRIBUNE PUBLISHING

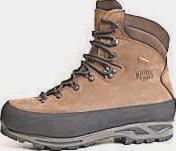

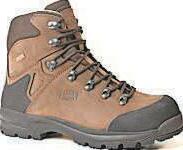

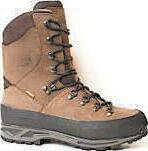

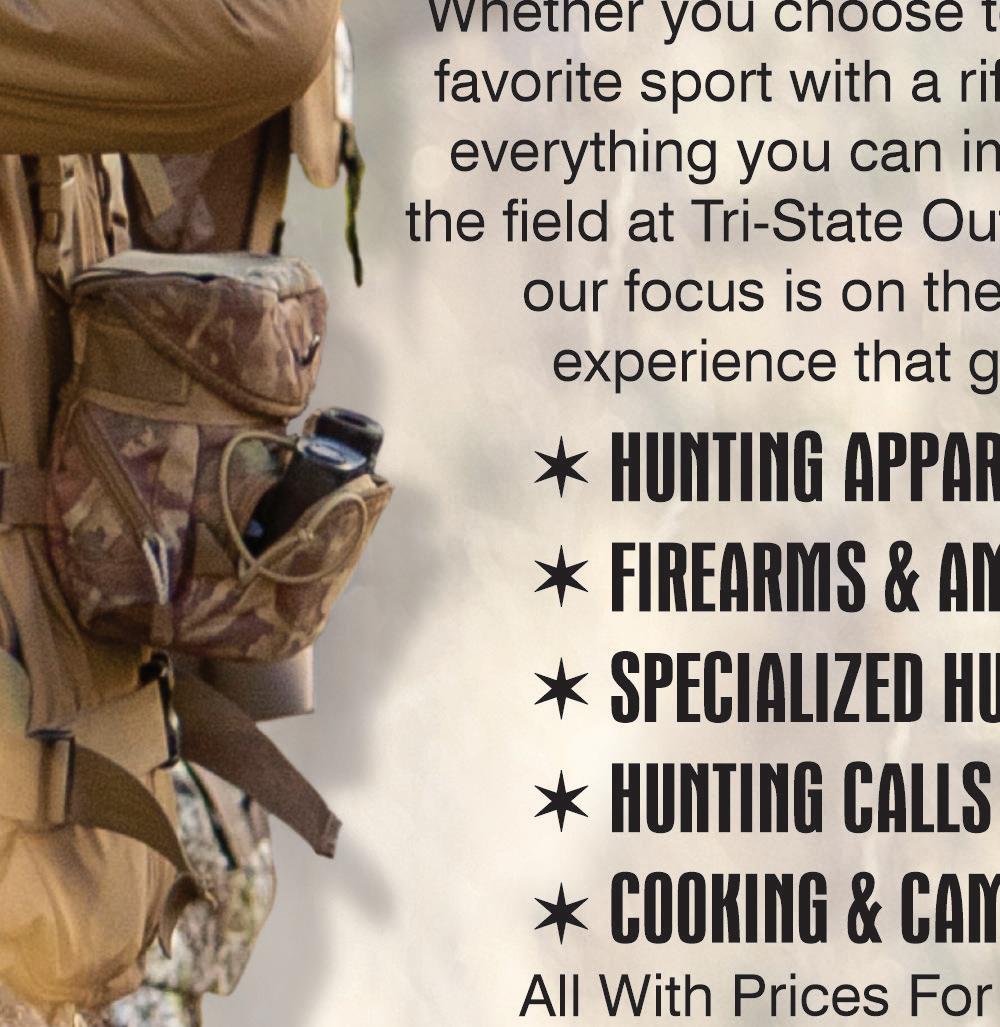

Hunting is a rich tradition, and there’s plenty of room for more people to partake LT -600455 GrandeRondeRiverSeries HH550 Lochsa HH501 Payette HH510 Owyhee ORCHARDSSHOESHOP 546ThainRd.,Lewiston|208-743-0981|MON.-FRI.9A.M.TO5P.M.,SAT. 9A.M.TO2P.M.

We are proud to supportto local outdoor enthusiasts.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2022OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022 3

600477J_21

Mission is clear: creating hunters

The First Hunt Foundation, started a decade ago by former national forest chief Rick Brazell, has expanded to 38 states

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

Even before Rick Brazell retired as supervisor of the Nez PerceClearwater National Forest in 2014, he knew what his next steps would be.

Although he started small, his ambitions were sky high — he wanted his idea to blossom into the largest boots-on-the-ground hunting mentoring organization in the nation. Eight years later, his First Hunt Foundation is well on its way.

“Our mission is just to create hunters,” he said.

Brazell sees that mission as critical to ensuring hunting survives as a cherished activity and important conservation tool. He points to data that shows the average age of hunters is about 60. In a decade or less, many of them will no longer participate. If they are not replaced, state wildlife agencies dependent on license revenue to manage and conserve wildlife populations will be in rough shape.

Brazell’s program continues to grow exponentially and now operates in 38 states.

“We’ve got over 800 volunteers that are out teaching people and we get four or five more every week,” he said. “We will have over 1,000 in probably six months.”

Brazell, a lifelong hunter, started the foundation out of his home near Kamiah. At first, he catered mostly to local kids who wanted to learn to hunt. But soon, often through the connections he’d amassed during his more than three decade career with the Forest Service, word started to spread.

“I had friends who were hunters

OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 20224

First Hunt Foundation

ABOVE: Rick Brazell (center) founded the First Hunt Foundation after he retired from the U.S. Forest Service. The group’s mission is to help people learn to hunt. TOP PHOTO: The First Hunt Foundation now operates in 38 states. The group coaches and mentors kids and adults who are interested in taking up hunting.

> See MISSION, Page 5 HUNTER DEVELOPMENT

in other states (and) they said, ‘Can I do it here in this state?’

We said ‘sure’ and we became aware we could build this thing across the nation.”

Now the foundation teaches people of all ages and backgrounds. While kids still make up the bulk of the students, adults are common and some of the first time-hunters have been in their 70s. The foundation now has a woman’s program and one that focuses on military veterans and first responders.

“Women are the fastestgrowing component of new hunters in the nation,” he said. “A lot of times, women and young girls would rather go out with a lady than an older guy.”

In some ways, the growth of the organization has outpaced its internal infrastructure. Although it operates in 38 states, Brazell said there are only seven state directors. That has him putting in more than full-time hours. He recruits volunteer mentors, helps connect people who want to hunt to instructors, organizes events and, of course, he raises money.

“Our big issue is finding funding.

A mentor helps

new

We have to pay liability insurance and we give $15,000 worth of caps away each year and we don’t have any paid staff. Nobody, including me, gets a penny. We are all-volunteer.”

The money is coming in. The

foundation’s mission has resonated with other organizations and businesses. Brazell said First Hunt has gotten about $100,000 a year from the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation and support from the

National Wild Turkey Federation, Pheasants Forever, the Boone and Crockett Club and the Backcountry Hunters and Anglers. It has also partnered with state fish and wildlife agencies like the Idaho Department of Fish and Game and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, and private companies like Vortex Optics, CCI and Speer ammunition and Rocky Mountain Hunting Calls. Some of the companies offer discounts to mentors, a small perk for the volunteer service.

Brazell and other volunteers are now working to grow its recently established Hunting Heritage endowment that is housed at the MidwayUSA Foundation. The endowment was started with grants from the NRA Hunter’s Leadership Foundation, Vista Outdoors and the MidwayUSA Foundation. Brazell hopes to withdraw 5% of the endowment annually to help with expenses while continuing to grow the principal.

More information about the First Hunt Foundation is available at firsthuntfoundation.org

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@ lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273. Follow him on Twitter @ezebarker.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2022OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022 5

Courtesy photo

a

hunter as he prepares to make a shot. > MISSION FROM Page 3 Let us fix your vehicle right, the first time. Belts & Hoses Mufflers Exhaust Systems Transfer Cases Engine Cooling Transmissions Brake Services and more! Get your vehicle back on target. 1014 Bryden Ave., Lewiston 208-743-5887 • petersontransmission.com 616783J_22 Kimber Master Dealer 1026 Main St. Lewiston • 208-743-1031 www.LoloSportingGoods.com • Mon-Sat: 10-6 New & UsedNew & Used Firearms Gunsmithing Fish & Game Licenses WE BUY GUNS! Consignment Fee - 15% ï Gun Pawn Interest Rate - 10% LOLO SPORTING GOODS 616924i

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

For Ray Livingston, hunting is an escape that serves as a vehicle to focus the mind and sustain the body.

He relishes the solitude and focus it brings, as well as the clean and natural food that follows a successful outing. It’s an all-in lifestyle for him.

“It became my place of peace, where I would go when I needed to relax and unwind or figure out my path in life,” he said. “When you’re free of the distractions of this crazy modern world that we live in and you can relax, your thoughts become clearer, your direction becomes clearer and things make a bit more sense.”

The 47-year-old former track and field athlete turned survivalist, reality TV star and hunting advocate wants others to experience the same sense of clarity. He is one of the more than 800 mentors working with the First Hunt Foundation.

“I became a mentor because I enjoy passing on these skills,” he said during a telephone interview from his home north of Kettle Falls, Wash. “If I can somehow truncate somebody else’s timeline so that they can become more comfortable and more efficient and effective with harvesting game, I’m happy.”

He wasn’t always confident in the skills he now teaches. Livingston learned to hunt at 14 from the family of his best friend after he moved to Gresham, Ore.

“He was like the ‘oops child’ so he was way younger than everybody else. So they started bringing me to be company for him and I fell in love with it,” he said. “I harvested my first season and harvested an elk with a bow, and I’ve been hooked ever since.”

He went on his first solo hunt in college but turned back before it started when overwhelmed with a sense of unease.

Reality TV star is happy to bring new hunters into fold

“I realized I didn’t have the confidence and the skill yet to really go out and be comfortable in the woods, and if I wasn’t comfortable in the woods, then I’m not going to be an effective hunter,” he said. “So I just took baby steps and I kind of got more and more comfortable going deeper and deeper into the woods by myself.”

Now he’s known for those skills. He was on season six of the survival show “Alone,”

National Geographic’s “Called to the Wild,” “Mud, Sweat and Beards” on the USA Network and he is set to appear on the History Channel’s “Mountain Men.”

Although he is skilled as a survivalist and comfortable with primitive tools, Livingston enjoys hunting with modern sporting rifles, more commonly known as assault rifles. He takes what he calls a golf bag approach to firearms — meaning he

likes having different guns for different hunting situations, just as a golfer reaches for different clubs depending on the distance of his shot, the lie and the conditions. He said the AR-15 and AR-10 can be quickly adapted to changing conditions or uses by swapping out the upper portions of the guns. He can easily and quickly change things like barrel length and caliber.

“It’s a great modular system.”

One of the things he loves about introducing others to hunting is being adjacent to the thrill they get. He relishes hunting for the adventure, the outdoor experience and for the chance to fill his freezer. But helping others gives him a different feeling.

“The joy I get in helping somebody else take their first animal is definitely greater,” he said.

Teaching also means learning. Livingston said it forces him to really think about what he does while hunting and why he does it, so that he can effectively explain it to others.

“That is when we as hunters learn because we have to really think and break down the process and present it in

OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 20226

Ray Livingston enjoys the vicarious thrill of helping others take their first animal

Courtesy photo

Ray Livingston, of Kettle Falls, Wash., a mentor with the First Hunt Foundation, poses with a turkey he shot.

> See TV STAR, Page 7

Operation Save Hunting

Military

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

For the first time in his adult life, Rich Cotte found himself bogged down in a mental morass.

Hunting would help him escape.

Cotte had recently retired following two decades in the service — seven in the Air Force and 13 as an Army officer. If he’d seen a

psychologist, he’s certain he would have been diagnosed with depression. Instead, he confided in his wife and followed her orders.

“She said, ‘Go figure out what’s wrong.’ ”

He did. It turns out the feelings that dogged him are not uncommon in people who leave the service or other purpose-driven occupations like law enforcement and

various components in balance.

a manner that will be understood by the people we are mentoring,” he said.

“So definitely, I grow more as a hunter when I teach. That is true of anything. If you’re teaching something, you are learning more and more about it.”

Helping to expand the ranks of hunters is also a way for him to help the ecosystem. He views hunting as a critical activity that, when directed by professional wildlife agencies, preserves nature and helps keep its

“Legal, regulated, ethical hunting is something that is important — for our lives, our lifestyle, the ecosystem. I’m doing the best I can to help out by passing that on.”

He has a passion for hunting predators like wolves, black bears and mountain lions and says the populations of those animals are out of balance with populations of deer, elk and moose.

“We are part of the ecosystem. We are part of the equation and we are the only part of it that can make a

emergency services.

“I figured out I just didn’t have a mission. I lost purpose, and I lost connection with the community I had most of my adult life,” he said.

After moving to Kalispell, Mont., Cotte adopted a new mission — save hunting.

“I decided to start a nonprofit to help veterans and first responders going through the same loss of community, the same loss of purpose.”

The idea was to recruit people going through the same life transition that bogged him down and train them as hunting mentors. While researching the new mission, he stumbled upon the First Hunt Foundation. He called Rick Brazell, the retired supervisor of the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest who founded and runs the organization. After a two-hour phone conversation, Brazell recruited Cotte.

“He said, ‘Come work with me,’ ” Cotte said.

Together they started Connecting Heroes and Hunters as part of the First Hunt Foundation. There are a handful of good organizations that help struggling veterans by teaching them how to hunt, fish or engage in other outdoor activities. Cotte’s program does the same thing but that is not the mission. Instead, they want to train people who have a history of service and a commitment to teamwork, to become hunting mentors.

“I like to think we do it differently than other organizations that just want to take a vet hunting or an excop or ex-firefighter hunting. We look at it as a targeted recruitment program for the organization.”

cognitive effort to kind of keep things in balance. Now Mother Nature will, in her own cycle, balance things out, but there will be huge ebbs and flows. There’s nothing wrong with having a little bit of equilibrium and helping that equilibrium, and that is what hunting does.”

Livingston wants more people to take up hunting, including people of color — an underrepresented demographic in the hunting ranks. He points out that hunting helped the human race survive and evolve. Some of his ancestors — the San Bushmen of southern Africa

They are part of the nationwide R3 movement aimed at shoring up the ranks of hunters. It has been adopted by fish and wildlife management agencies and hunting organizations alike. The movement is centered around reversing the nationwide decline in hunting that threatens to erode hunting-based conservation and the funding for statebased wildlife management that is heavily dependent on the sale of licenses and tags. The goal, represented by the three R’s, is to recruit new hunters, retain existing hunters and reactivate those who have stepped away from the activity.

“It’s become my new passion in life,” Cotte said. “I absolutely enjoy hunting — grabbing my rifle or bow — but what I learned is if I can take somebody with me and share that passion, I get so much more out of it.”

The mentors coach their students through the hunter education process and teach them not only how to hunt but the ethics behind the pursuit and how hunting contributes to wildlife conservation. The process generally culminates with a hunting trip and often the harvest of an animal.

Cotte said Connecting Heroes and Hunters has recruited about 30 mentors in the last year and identified about another 80 veterans and first responders who were already participating in the First Hunt Foundation.

“It’s really exploding.”

More information is available at bit.ly/3RUYhuF.

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273. Follow him on Twitter @ezebarker.

— were and are skilled hunters. The same is true of all cultures.

“If you exist in the world today, hunting and primitive skills is why you exist. Because your ancestors from whatever culture you live in, knew how to do it.

“If it weren’t for that, none of these cultures would exist today. So I encourage people of color, women, everybody really, to get in tune with those skills.”

Livingstone maintains social media accounts on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube. n

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2022OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022 7

veteran Rich Cotte takes on a new mission: helping fellow former soldiers find a call of duty after their time in the service

Courtesy photo

Rich Cotte (left) and a veteran he coached pose for a photo following a succesful deer hunt. Cotte is the founder of Connecting Heroes and Hunters, a part of the First Hunt Foundation.

> TV STAR from Page 6

Building a network of support for new hunters

First Hunt Foundation seeks to pass on hunting heritage to newcomers, and Ann Beihoffer is seeking more female mentors for the program

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

For Ann Beihoffer, being a mentor to new hunters is about building relationships.

A lot of programs introduce people to hunting over a single excursion, like a pheasant hunting clinic. They might learn about the birds, their habitat, hunting techniques and culminate the experience with a hunt. After that, the new hunters are often on their own.

“We are not just one-anddone. We really try to foster relationships,” she said. “You might help somebody go on their first pheasant hunt, but say, ‘Let’s keep in touch, let’s build a network of support.’ ”

For example, if the new hunter enjoys the experience, Beihoffer wants to be in position to invite them into their next experience, perhaps a turkey hunt.

Beihoffer, of Aitkin, Minn., is a hunting mentor with the First Hunt Foundation and the founder of the Share the HERitage program within it. Her goal is to recruit female hunters into the foundation’s army of mentors where they will be available to teach and coach women and girls interested in hunting.

She notes women make up one of the fastest growing demographic groups in hunting. Having female mentors available can make it more comfortable for novices.

“In my experience, the way women learn, the way they approach hunting, can be different than their male counterparts. It helps to have women who know about the barriers and challenges

they can run into,” she said.

“My vision is to have female mentors available across the country in every state. I just want to provide that network

that women can tap into.”

It may be a single mother who wants to introduce her children to hunting, the wife of a hunter who wants to also

take it up, or like so many other people learning to hunt as adults, it could be someone interested in providing locally sourced meat to her family.

“It’s very empowering for women to know they can go out in the field and learn to hunt and harvest game,” she said. “Just that feeling of ‘I’m able to do it,’ is really important to women.”

Many women approach hunting a little differently than men, Beihoffer said.

“I oftentimes see with women, it’s like they are more involved in the hunt. They have more angst about making a good, clean shot and single-shot kill. They are just really conscientious and really (concerned with) doing what they can to make it a good experience for them and a very ethical experience for the animal too.”

The program is just taking wing. She estimates about 20% of the mentors within the First Hunt Foundation are women, which she said is pretty good. But she also noted there are some state chapters without any female mentors. Beihoffer hopes to draw from the ranks of experienced female hunters to help close the gap.

She said those who volunteer can help bolster the existing hunting heritage and help newcomers build their own traditions and experiences. But there’s also something in it for the mentors.

“The interesting thing about mentoring or coaching, every time you do that you learn something yourself,” she said. “It’s because you see that experience through somebody else’s eyes. When you can see it through somebody else’s eyes, it’s pretty neat.”

Beihoffer can be contacted at anneb@ firsthuntfoundation.org More information about the First Hunt Foundation is available on its website at firsthuntfoundation.org.

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273. Follow him on Twitter @ezebarker.

OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 20228

Courtesy photo Anne Beihoffer poses with a nice whitetail buck. Beihoffer founded Share the HERitage, part of the First Hunt Foundation.

HUNTER DEVELOPMENT

Every

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2022OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022 9 Lewiston 2981 Thain Grade north40.com

great HUNT starts here.

Wild game GOURMET

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

Justin Townsend grew up hunting and fishing in Oklahoma where his family used wild game to supplement food purchased from supermarkets.

After college and a stint cooking in some of the top restaurants in New Orleans and San Diego, Townsend launched Harvestingnature. com, a multiplatform website, in 2011 with the goal of sharing his passion for cooking and introducing people to the benefits of wild game, fish and foraged food.

“As long as we approach it in a sustainable manner, it’s the best food out there. It’s nutrient dense, it’s not processed and it’s great to get out and get your own food because you have to be active to do so.”

The website has about 20 contributing writers and support staff. In addition to recipes and articles, it includes podcasts and videos featuring luminaries in the wild food movement, cooking technique and hunting and fishing adventures. In 2017, his cookbook “Eat Wild Game: Recipes for the Adventurous” was published. Last year, Townsend added a series of spice blends to the mix and launched a quarterly electronic magazine.

The company recently

stepped out of the virtual realm and began offering wild food field camps where people sign up, travel to a location and are immersed in handson hunting and cooking. The next one, in December, will be held in northern Texas and participants will spend three days learning to hunt, process and cook wild hogs and become familiar with techniques easily transferred to other big game species.

“It’s been great to see it all come together and continue to evolve and just be a really awesome space to engage with people,” he said of the website. The goal from the beginning has been to help people enjoy wild food whether they are long-time hunters or just getting into it. “We want to inspire people to get outdoors to hunt and fish and forage for their food. We don’t want it to be intimidating,” he said.

“We say here are some great ways to prepare food, methods, tips and tricks. Here are some adventures we are going on.”

Townsend shares two recipes here. The first, “The Best Venison Mississippi Pot Roast,” is an adaptation of a popular slow cooker recipe.

“I like that one because you can use a variety of cuts of meat, just mix it all together and put it in a crock pot and let it go. You can serve it over potatoes, rice,

or pasta,” he said. “It’s a take on a popular dish. The dish that became (internet) popular used ranch season packets. This one uses fresh herbs and takes that same flavor but recreates it so you are not eating a bunch of processed food.”

THE BEST VENISON MISSISSIPPI POT ROAST

Recipe with video at bit.ly/3TiKdeR

INGREDIENTS:

3 pounds venison roast

1 tablespoon mayonnaise

1 teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon black pepper

1 tablespoon oil

6 tablespoon butter

1 cup chopped yellow onion

3 tablespoon flour

8 pepperoncini

4 tablespoons vinegar from pepperoncini

2 teaspoons minced fresh dill

2 teaspoons garlic powder

2 teaspoons minced fresh chives

2 teaspoons minced fresh parsley

Your favorite starch

PREPARATION:

Remove roast from the fridge and allow to temper for 30 minutes to 1 hour. Preheat the slow cooker to low heat.

Bring a cast-iron skillet to medium-high heat. Coat the roast with the mayonnaise and season with salt and black pepper. Add the oil to the pan and sear each side of the roast in the pan. Add the seared roast to the slow cooker. Reduce the pan to medium-low heat. Melt the butter in the cast iron pan and add the onions. Saute the onions until slightly translucent. Stir in the flour and mix until all the ingredients are well

Harvesting Nature

Townsend started out as a cook and has turned his skills into an online enterprise to help people make the most out of their game.

incorporated. Scrape the onions and flour into the slow cooker.

Add the pepperoncini, vinegar, dill, garlic powder, chives, and parsley.

Cover the slow cooker and allow to cook for 6-8 hours or until the meat easily pulls apart with a fork.

Once finished, set aside the pepperoncini. Place meat and juice in a large bowl and shred to incorporate the meat and juices.

Serve over your preferred starch garnished with the pepperoncini.

The second recipe, sous vide peking dove, is a take off on Peking duck. Townsend substitutes plucked whole dove for duck but said any small game bird can be used. He also forgoes the traditional roasting and drying steps and instead prepares the dove sous vide —

which means vacuum sealing the meat and then cooking it slowly, at precise temperatures, in a water bath. He then finishes it on a hot grill to give the dish a crispy skin.

The sous vide technique has become popular in the last decade or so and equipment is widely available.

“I like to keep a lot of game birds whole so you can get the full flavor. You are going to slow simmer it in sauce, pull it off and give it a little char on the grill.

SOUS VIDE PEKING DOVE

WITH PICKLED VEGGIES

Recipe at bit.ly/3SWHpnG

INGREDIENTS:

6 whole doves, cleaned

2 tablespoons honey

2 tablespoons Chinese 5 spice

2 tablespoons soy sauce

2 tablespoons brown sugar

3 tablespoons hoisin sauce

1 teaspoon sesame oil

Pickled vegetables

1 cucumber, thinly sliced (¼ inch)

1 carrot, finely shredded 4 shallots, minced

Sprinkle of salt and pepper

3 tablespoons red wine vinegar

2 cups prepared jasmine rice

Sesame seeds

PREPARATION:

Bring your sous vide to 140 degrees

Place doves in a sous vide bag and set aside

In a mixing bowl, combine honey, Chinese 5 spice, soy sauce, brown sugar, hoisin sauce, and sesame oil. Mix well.

Spilt the sauce in half and reserve half. Pour the remaining half in the bag with the dove. Move the dove around to coat all edges. Vacuum seal the bag or remove all the air.

Place the sealed bag in the sous vide and cook for 1 hour at 140 degrees.

While waiting, prepare vegetables and rice.

In a mixing bowl, combine cucumbers, salt, pepper, vinegar, carrots, and shallots.

Place in refrigerator and allow to cool.

Within the last 15 minutes of the dove cooking, bring your grill to high heat.

Remove the dove as the hour finishes and place the dove on the grill.

Cook until the internal temperature reaches 160 degrees.

Plate rice, then veggies, then dove, and then top with sesame seeds and the remaining sauce. n

OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 202210 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2022OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022 11 Fine dining is possible using ingredients hunted, caught or foraged outdoors; this website offers tips and recipes

HUNT CUISINE

Justin

Townsend, founder of Harvestingnature.com poses holding a pair of backstraps. Harvesting Nature

Harvesting

Nature

LEFT: Best venison mississippi pot roast served on mashed potatoes. RIGHT: Sous vide peking dove with pickled veggies.

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

There is plenty of opportu nity for deer and elk hunt ers in both Washington and Idaho, but some of the herds in both states are struggling and hunters pursuing game in those areas may find it chal lenging to fill their freezers.

For example, elk herds are in decline on what was once some of the best hunting units in the West — portions of the Blue Mountains in Washing ton and in the Lolo, Selway and other backcountry zones. In Idaho, elk in the Clear water Region’s backcountry zones have been struggling for more than 20 years because of habitat decline exacerbated by predation.

The slide has been short er lived in the Blue Moun tains. Thus far, biologists have placed the blame on predators — namely moun tain lions that have shown to be taking a high number of elk calves. Parts of the Blues were also hit hard by harsh winters in the recent past, which led to above-av erage winter mortality.

Deer herds in lower eleva tions in both states took a gut punch from epizootic hemor rhagic disease last summer.

The Clearwater Region was hit extra hard, particularly in parts of units 8, 8A, 10A and especially in 11A along the Clearwater River near Kami ah. By Idaho Fish and Game estimates, the illness, which is spread by gnats around stag nant water sources like ranch ponds, killed 6,000 to 10,000 deer, mostly whitetails.

In response, the Idaho Fish and Game Commission eliminated its normal of fering of about 1,500 extra doe tags, awarded through controlled hunt drawings. Those tags are designed to reduce crop damage.

“Doing that is going to help those populations bounce back quickly,” said Jana Ash ling, regional wildlife manag er for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. “Whitetail deer are extremely prolific.”

She said populations could be back to pre-EHD levels in three to five years or less, but it may take longer for

DEER AND ELK HUNTING

Hardertotarget

Hunters will be challenged this year, with deer and elk numbers down in key areas of Idaho and Washington

the number of mature bucks to reach previous levels.

Those pursuing deer in areas hit hard by EHD are likely to find hunting tougher than they may be accustomed to. But Ashling said many areas, especially at elevations, were spared die-offs and populations should not be affected.

The lower elevations areas of southeastern Washington were also hit with EHD dieoffs during the late summer and early fall of 2021. Accord

ing to the Washington De partment of Fish and Wildlife, 15% of 40 radio-collared mule deer does died of hemorrhag ic disease that summer.

The agency said the out break has slowed the ex pected rebound from heavy mortality during the winters of 2016-17 and 2018-19. But last winter was not severe and EHD was not a significant presence this year. Because of that, along with a lack of wild fire closures and good forage conditions resulting from a

wet spring, wildlife managers expect harvest to be improved compared to the fall of 2021.

Clearwater Elk Idaho Fish and Game noted elk densities in the Lolo, Selway and Hells Canyon zones continue to struggle. Elk are stable in the Palouse Zone. Abundance dropped in the Dworshak Zone, but Ashling noted the decline is relative to what were high elk numbers recorded in the last survey. The agency conducts

Cow elk and a young bull traverse a hillside.

Roger Phillips/Idaho Fish and Game

aerial surveys every five or so years in its various elk zones. Abundance increased in the Elk City Zone, she said.

Blue Mountain Elk

Biologists from the Wash ington Department of Fish and Wildlife recorded a calf-to-cow ratio of 17 to 100 during aerial surveys last spring. That is below the 22 to 100 level consid ered necessary for herds to remain stable. A calf elk monitoring project showed low survival, with predation by mountain lions being the chief cause of mortality.

“The low number of calves being recruited into the population in 2022 will result in a low number of yearling bulls (spikes) available for harvest this fall. This fall will be another below-av erage year for yearling bull harvest,” according the agency’s District 3 Hunting Prospects document. n

OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 202212

DEER AND ELK HUNTING

In the Blues, a tale of two elk populations

Oregon herds doing better than ones in Washington, but both face same challenges

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

Elk in the Blue Moun tains straddle both sides of the Washington-Oregon stateline.

North of the border, the herds are in decline and too few calves are surviving for the popula tion to stabilize or grow.

South of the line, in Oregon, the herd is doing better.

“We have a few areas where distributions are shifting a little bit for a variety of reasons, things like drought and water and habitat condition, and in some cases, the wolves are moving animals around to new areas, but the pop ulations themselves are doing pretty good,” said Don Whittaker, ungulate species coordinator for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife at La Grande. “We don’t have a lot of huge concerns about the population.”

Why?

Whittaker said the Oregon herds have calf-to-cow ratios in the low 30s to high 20s compared to 17 calves per 100 cows for the Wash ington portion of the Blues.

The habitat is largely the same.

But Whittaker said conditions may be a bit wetter in the Oregon portion of the Blues. Predator densities are likely in the same neighborhood.

“We aren’t dramatically differ ent in our efforts and capabilities on predator harvest. We are very similar,” he said. “We are very similar on our predator cohorts — we have cougars, black bears and

wolves, and (Washington) has cou gars, black bears and wolves.”

Whittaker said his agency has been tracking climate changes that could affect habitat and trickle down to cow and calf health. In short, plants are drying as many as four to six weeks sooner than they once did and the change is happening at a time when elk calves need access

to high-quality forage.

“We are talking in late May or June, where it used to be late June and July. So that is a pretty dramatic difference,” he said. “When you have a few days on either side of that grass-isgreen period, it adds up on both ends. For cows, that is a pretty important time period; they need lots of en ergy in to provide adequate nutrition for their calves.”

Poor forage quality at that time may lead to “weak calf syndrome.”

“When they are weak, they are much more suscep tible to predation,” he said.

Whittaker stressed that he cannot say the same thing is happening in Wash ington and that in Oregon, it is just one factor in a com plicated tangle of conditions and players on the land scape, including climate, weather and predators.

“Predator numbers are changing, nutrition is changing, temperatures are changing, energy requirements are chang ing, energy sources are changing,” he said. “It’s a big ugly, messy picture, a cascading stack of dominos.”

He said researchers from his agency and the U.S. Forest Ser vice will soon publish the work on the changes in plant phenology.

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@ lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273. Follow him on Twitter @ezebarker.

OLYMPIA — In an effort to protect bighorn sheep, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is inviting public comment on a proposed rule that would prohibit visitors from bringing domestic sheep or goats onto some units of the state’s wildlife areas.

The proposed rule is intended to reduce the risk of transmission of Myco-

plasma ovipneumoniae (Movi), a type of bacteria that causes pneumonia and can be deadly to bighorn sheep, according to an agency news release.

Past pneumonia outbreaks among bighorn sheep in Washington and other parts of the West have been linked to contact between wild sheep and domestic sheep or goats,

which carry the bacteria.

The proposed rule would apply to select wildlife area units of Asotin Creek, Chelan, Chief Joseph, Colockum, Columbia Basin, L.T. Murray, Oak Creek, Scotch Creek, Sinlahekin, Wells, Wenas and W.T. Wooten wildlife areas.

The proposed rule is available for review

bit.ly/3ETYwTh

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2022OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022 13

Rick Swat/Oregon Dept. of Fish and Wildlife

A herd of Rocky Mountain elk grazes on the breaks of the canyon above Camp Creek in the Blue Mountain range of northeast Oregon.

at

. Officials mull ban of domestic sheep, goats in some wildlife areas 2275Nursery St., Moscow (208)883-3007 620Thain Road, Lewiston (208)746-6447 www.bluemountainag.com Locally Owned& Operated since 1987! • 59.8 cc professional-grade • 2-strokeengine • Decompression valve foreasy starting • G-Force EngineAirPre-Cleaner • Availablein18"or20" bar Echo Timber Wolf CS-590-20 $39999 LT -600264 BlueMountainAG

WILDLIFE MALADIES

Small pests a big concern for Idaho moose

Recent research shows that parasites, not large predators, likely the biggest drag on moose population

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

Just like populations across the country, moose in Idaho are in decline.

Researchers at the University of Idaho and Idaho Department of Fish and Game are working to unravel the cause. There is more research to be done but early results indicate survival of calves into adulthood may be a problem, and ticks and other parasites may be driving population declines. Thus far, wolves and other large predators like mountain lions and bears have not shown to be a significant cause of mortality.

“When you think about what is preying on moose here, it’s really the parasites,” said Janet Rachlow, professor of wildlife ecology at the University of Idaho. “That is what comes up as being involved — if not the exact proximate cause of mortality — certainly being involved and compromising the health of adults and calves.”

For hunters, the falling numbers have led to an erosion of opportunity. Idaho allows hunters to take just one moose in their lifetimes. But to do so, they must draw a tag, and the odds, which have always been long, are getting longer. There were 90 moose tags available in the Clearwater Region this year. But two decades ago, populations were robust enough to support nearly 300 tags.

The decline is also reducing the opportunity of wildlife watchers to observe moose — the largest big game animal in Idaho and

among the most charismatic.

Rachlow, working with Fish and Game as well as graduate students, has led a multiyear effort to examine the causes of moose decline. In 2020, 112 adult cow moose were fitted with tracking collars. They registered an 89% survival rate into the fall of 2021.

The collaring study was

LEFT: Winter ticks are a likely suspect in the cause of moose declines in Idaho and elsewhere in the Lower 48 United States.

BELOW: A cow moose and her young calf wade through late spring snow. Researchers from the University of Idaho have determined too few calves are surviving their first year to reverse a downward trend of the iconic animals.

Eric Van Beek

Eric Van Beek

repeated across 2021 and into 2022. Again, adult cow survival was high — 85% to 90%.

But calf survival has been lower. During the study, researchers noted the pregnancy rates of the cows and checked in with the animals from time to time to observe if they had calves, how many, and whether they

survived their first few months of life.

Most of the cows, 85% to 90%, were pregnant and most of them delivered calves. Calf mortality through their first summer ranged between 60% and 80%.

Eric Van Beek, the lead graduate student working on the project,

OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 202214 > See MOOSE, Page 15

said a consistent survival of 80% would be good but 60% is getting on the low side – especially when survival is tracked through the calves’ first winter.

“Adult survival was pretty good, pregnancy rates were good — 85% to 90%. For the most part they are carrying their pregnancies to term. We had some variability in birth rates but last year it was 82%. So for the most part, calves are being born,” Van Beek said. “If they do survive through the summer, it seems like they are making it to the fall, but the big thing is, those calves aren’t making it through their first winter.”

The researchers collared 17 calves who were 9 months old in February. That group has a survival rate of just 52% through late winter and early spring, the toughest time of the year for ungulates.

Rachlow said it’s a time calves can be expected to be nutritionally stressed and vulnerable from winter ticks. She pointed to a study from Maine in which wildlife biologists collared 70 moose calves and tracked them through the winter. Just 14% survived. Researchers blamed the high mortality on winter ticks.

Thousands and sometimes tens of thousands of the ticks can infest a single moose, which often rub themselves raw and hairless in an effort to rid themselves of the parasitic arachnids. Ticks also cause moose to lose blood and devote critical resources to replacing it.

Rachlow said some moose perish from

Corn and other rich food a death sentence for wintering moose

Janet Rachlow, a professor of wildlife ecology at the University of Idaho, had one message for me when I asked if there was anything important we hadn’t covered during an interview about Idaho’s moose population and what is driving a decline in numbers.

“Don’t feed them,” she said. “There are moose that die every year with bellies full of corn. It kills them.”

rural subdivision and were fed corn.

They have collared 163 moose, most of which were adult cows. Of those, 30 died. The collars send an email to researchers when the animal hasn’t moved in several hours, indicating it is likely dead.

COMMENTARY

Winter is a harsh time for moose. There is not much to eat and their bodies adjust to the scarcity. By February, March and into early spring, moose can look pretty haggard. They are skinny and sometimes have large patches of missing fur — the result of rubbing against trees in an attempt to scrape away blood-sucking ticks.

Eric Barker

“They were in great health. Coats were in perfect winter health. No tick loads. Had a healthy amount of fat this late in the winter,” Matt Haag, an Idaho Fish and Game enforcement officer, told the newspaper. “The one thing that gets them this time of the year is feeding them really dense nutrient-rich food.”

Rachlow said as bad as they sometimes look, moose can quickly return to health when new growth emerges in the spring.

“Most of these mortalities, we are out on within 24 to 48 hours,” he said. “Almost every moose is usually fully intact. It doesn’t have any bite marks and hardly any scavenging. There are no signs of predation on almost all of these.”

People are tempted to help. Too often, Rachlow says, they feed them carbohydrate-rich foods like corn that their bodies are unable to process during the lean months. A story in the Spokesman-Review last winter (bit.ly/3SntPsU) detailed the deaths of an otherwise healthy cow and calf near Clark Fork in the Idaho Panhandle. The animals were hanging out in a

exsanguination but they can also die of secondary causes related to ticks.

“There are a number of different routes where ticks can feed into poor body condition and malnutrition. There is sort of a spiral they get into,” she said.

Another study out of Isle Royale on Lake Superior backs the idea that climate

“You see these moose and they look terrible in the spring. They have hair loss and they are skinny. But by and large, the ticks drop off and the animals get new vegetation and actually going into fall those animals are in pretty good shape,” she said. “People are tempted to feed them, but if you leave them alone and they get back on natural forage, they do a pretty good job of rebounding.”

Barker is the outdoors editor of the Lewiston Tribune. He may be contacted at ebarker@lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273. Follow him on Twitter @ezebarker.

change is leading to higher tick burdens for moose.

Rachlow and Van Beek can’t say for sure if the same thing — high tick burdens driven by climate change and leading to poor calf survival — is happening in Idaho. But their initial data tells them it’s an area worth pursuing.

The moose they are observing show signs of

being nutritionally stressed, in poor body conditions and with scabs indicating they have tried to rub ticks off their bodies. And predators do kill moose. Van Beek said one of the older calves and one of the younger calves in the study group were killed by wolves, but it isn’t a significant cause of mortality in their data.

Rachlow said the moose in the study also had a higher prevalence of carotid artery worm, a native parasite, and a blood parasite than they expected, and it’s possible other diseases are playing a role in the poor nutrition and body conditions observed in collared animals.

They’d like to expand the number of older calves collared. For now, Van Beek is working to put together enough demographic information gleaned from moose across the state and in different habitat types that researchers can begin to build models that will aid the hunt for what is driving declines.

Shane Roberts, wildlife research manager for Fish and Game, said the agency is in the process of mapping out future research needs and which ones will receive funding. He thinks moose are likely to remain a priority.

“There is a pretty high likelihood we will continue the moose research with a specific look at cause specific mortality and over-winter survival rates of 6-monthsold calves,” he said.

Check the regulations when you head out in the field and call our office with questions [208] 799-5010 or check idfg.idaho.gov/. Call the CAP hotline 24 hours a day to report violations 1-800-632-5999 and a reminder to ask for permission before crossing or hunting private land.

OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2022 15 > MOOSE FROM Page 14

617099J 1037 21st Street, Lewiston (Across from Alberstons)from 208.743.5822 ï Veteran Owned Hours: Wed.-Sat. 10am-6pm www.vulcanforgeandknife.com World Class Knife Sharpening Services We Sharpen, Repair & Restore Axes, Hatchets, Machetes, And Much More! IT’S HUNTING SEASON! Bring in four knives, we’ll sharpen one for FREE

Role reversal: Elk pursues hunter

STREET CREEK, Idaho — The bull elk stuck tight to the tangled growth and downed trees of a ravine, snapping limbs, whining and chuckling out of sight and far enough below us that our approach would likely end in a bust.

Down there in the murky hollow where the bull hid, our pupils would dilate big as nickels as they adjusted to the lack of light. The vine maple and bramble cane laced with snaky rope grass would wrap around a hunter’s legs, tangle the limbs of bows and shafts of arrows, whisper, “not so fast,” and provide cover for the bull to spy anything sneaking in.

We sat in the duff on higher ground waiting for the nervous bull to come looking for us.

Up here, ponderosa pine mixed with clumps of sunny-slope ocean spray, elder and sumac, providing hiding spots for a hunter in otherwise open glades.

If the hesitant bull decided that our bugles and cow calls overstepped the line of civil discourse, and if the insults overcame his timidity, he would likely sneak up the draw of an old stream bed as he climbed the hill to check us out.

That was our hope, but we weren’t absolutely banking on it.

Ralph Bartholdt

“If he decides to visit us, I’ll betcha money he’ll sneak up the draw,” one of us said somewhat half-heartedly, as if testing the prognosis, having learned that elk aren’t immune to surprises.

“How much?” was the reply.

Grass and duff-covered, the overgrown stream bed we thought the elk might traverse was quiet under foot, thick with fallen needles and rotting leaves. It seemed the perfect route for an apprehensive bull to skulk in for a closer look at whatever intruder had invaded his stomping grounds.

I snuggled into a pocket of fir above the stream bed waiting for the bull to pass close enough to offer a target for my broadhead.

The decision was made after much deliberation that happened in a whir of a few seconds.

A bull elk bugles during the rut.

At first I was in the sloping meadow concealed behind the heft of a big ponderosa thinking that this bull, however demure, might just kick it up a notch and storm in to confront any comers.

But my mind started smoking because the bull had hidden apprehensively down there in the black hole for an hour or more while my efforts to slide down on my belly for a look left me dripping with sweat.

My noise and movements had quieted the animal as I busted twigs and debris under the soles of my ratty, Danner good-luck boots before climbing quietly back up the hill to where Jonas, my longtime hunting pal, had already become intimately acquainted with a camo-covered, big-bull yodeling tube.

Jonas is a man whose patience and calm in the face of inevitable defeat is countered by a sack of juju

he carries on a string around his neck when he hunts with me. The bag of seasoning, small bones and Chiclets, I think, is supplemented by occasional chants, dances and eye rolls depending on the decisions I make in the heat of the moment.

These are the decisions that determine whether tags are cut or the ride home is filled with an awkward, hundred-yard silence:

“That was a nice bull.”

“Yep.”

“You prolly shoulda shot it.”

“Yep.”

I scrambled out of the holler and crawled back to where Jonas sat on a pile of pine cones stroking the bugle tube with a vacant look that said he had resigned himself to not being home in time for his kid’s piano recital. Camouflaged and grease-painted, he sat in a patch of shade from a

Robert Millage Photography

yellow pine as the estranged bull elk we assumed was a raghorn squealed and appealed for us to just go away.

When the bull stopped squealing we heard hooves stomping up the hill.

“Here he comes,” Jonas said blankly, already aware that nothing good could happen from here forward.

I stumbled downhill toward the fat ponderosa pine in the overgrown meadow and waited as thoughts ricocheted off the walls of my skull.

Over there is better!

No, over here!

Wait!

Maybe?

What?

Then I dove into the shady draw above the dry stream and hid behind a clump of fir, certain the bull elk would choose the flume as a safe shortcut to reach Jonas’ now-furious bugles and squeals.

OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 202216

BACKWOODS ADVENTURE

COMMENTARY

The six-pointer — bigger than we had anticipated — clomped uphill like a climber knocking his toes into the dirt to get a better grip. He whistled with each breath and, fueled by adrenaline, focused on the place where he thought an adversary was messing with him, trying to run off with one of his cows.

There was a problem. After being teased and prodded, ridiculed maybe by what seemed to be an out-of-town boy frolicking with the neighborhood girls, our bull decided enough is enough. He had spent an hour at the bottom of the draw massaging his confidence into a honed fury. He shunned cover now and walked deliberately uphill through the open scab brush of the overgrown meadow and directly past the fat trunk of the pine that I had left a few minutes earlier.

As I watched from the shady draw above the dry stream, the bull cut a wake through the September sunlight too far away for my arrow, but precisely on the margin of my sanity.

Jonas is a journalist and former roofer. There are times when he considers trading in his white-collar job for the one he knew as a younger man. He longingly recalls dirty T-shirts, blistering suntans, tepid water bottles, fat paychecks and aching knees on a broiling incline three stories above residential subdivisions.

He has at times comforted himself with indecision instead of the rigidity required for resolution. During these moments of indulgence, his future appears overly burdensome and worthy of deep reflection, which is where I come in. I help him recognize that life is a gamble and serendipity is just a sophisticated word for royal flush. Happenstance lets you soak up the scenery on your way to the ticket window.

It’s not always like that, but the possibility allows for anticipation, the mother of hope, and faith, her freckled kid sister.

On this afternoon on a mountain in the Idaho elk woods, hunkered in the shade with a pile of elk calls, Jonas’ seemingly sedate past met the carnal red-eyed rage of an animal determined.

The six-point elk found Jonas a hollow image of the bull he came to fight but better than nothing at all.

Jonas was reacquainted with a determination of his own. He believed he would be gouged and trampled, and hoped it wasn’t so. Dropping the elk calls and his sense of aplomb, he rose to his feet and ran.

I lost track of the bull as it stomped uphill, but when the cow calling, grunts and squeals with which Jonas had entertained himself stopped rather suddenly, I stood up.

There came a yell.

“He’s right behind me!”

Galloping out from a knoll of trees on the ridge overhead was Jonas. The chestnut-antlered bull was close behind.

The scene was a dismal vaudeville, an old-time movie on frames of cracked and spliced film that caused the images to click haltingly — a man chased by an elk.

“What do I do?” Jonas yelled with an urgency I had not heard from him in a while.

He made brief stands behind trees and brush clumps, waving his arms, but the elk kept coming.

“Run this way!” I encouraged him.

It happened too fast to enjoy, but slow enough to reenact later as a simple pleasure.

What took place on that ridge, out of my sight, I cannot say, but Jonas finally emerged, sweating and shaking. He displayed the kind of emotional frailty usually reserved for the finish line of ultra marathons.

“Did you see that?” he asked as if wanting reassurance that he hadn’t suffered an out-of-body experience.

“He was in our pocket,” I said.

“I had to throw sticks to make him go away,” Jonas said. “I thought I was going to die.”

A man told me of shooting a raghorn bull at 5 yards that was being chased by a wolf. When he saw the hunter, the wolf made a somersault in its efforts to stop and reverse course, and the hunter let fly an arrow almost point blank that struck the bull behind a front leg, killing it.

“That was a memorable hunt,” the man said.

Elk hunting in drizzly fog one morning, another hunter’s frustration won out after an hour of calling. The hunter stood and turned to see what he described as “the Hartford bull,” standing calmly 30 feet behind him in the mist, and the man almost exited his boots. When he pulled himself off the ground, the elk was gone as soundlessly as he had sneaked in.

During each archery elk hunting season, scads of hunters will meet their own opportunities and make do with their private successes or failures, naming them whatever they choose.

If they do not result in steaks in the freezer and another set of antlers hanging from the wood shed, the memory of a good elk hunt provides a different kind of nutrition.

It’s reusable and often gets better with age.

Bartholdt, a former Tribune reporter, is the author of three books about the northern Idaho outdoors. He lives in Hayden. His latest book, "Tank Creek," will be available in local bookstores this fall.

Calling all off-roaders and trailblazers.

Lending for every thrill seeker.

Apply online at p1fcu.org and start planning your next outdoor adventure.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2022OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022 17

Insured by NCUA

BIRD HUNTING

Wet spring a mixed blessing for game birds

Rain created great nesting and rearing habitat but the cold, wet conditions likely doomed many hatchlings

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

Ample spring rain can lead to vigorous growth of shrubs and grasses and produce strong insect populations that set up great conditions for upland game birds.

Too much rain at the wrong time, combined with cool temperatures, can doom newly hatched chicks. However, in such instances, the birds have the ability to have second clutches and those late hatchlings can take advantage of good habitat to help stabilize populations.

Which scenario plays out this year remains to be seen. The spring of 2022 was cold and wet and likely tough on pheasants, partridge and quail chicks. But in contrast to 2021, bird cover is thick, giving them ample food sources and hiding spots from predators.

“When we look at the wet spring, of course it’s good and it creates good brood rearing habitat, but some times if it’s too cold during certain time periods, it can

result in some chick mor tality,” said Jana Ashling, regional wildlife manager for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game at Lewiston.

Ashling noted game birds can produce second clutches when frigid weather wipes out their first effort. It’s a bit of evolutionary insurance that helps ensure their surviv al. Those second groups of chicks should find plenty

of good habitat this year.

The number of pheasants, gray partridge and quail tallied during brood surveys conducted in the Clearwater Region in August were all down from the previous year.

Pheasants were off 80% com pared to last year and 78% against the 10-year average; gray partridges were down 34% compared to last year and 70% below the 10-year

average; and quails were down 28% from 2021 and 20% from the 10-year average.

Ashling said the results from the surveys can be used to track broad year-toyear trends but the agency believes the numbers aren’t precise. The technique, where surveyors drive predeter mined routes at dawn and count birds they see, was developed in the Midwest. It

counts on thick dew driving the birds to open areas like the sides of roads where they can easily be counted.

Those dewey conditions don’t really exist in Idaho. She said the agency is looking for new ways to survey upland birds and may move to using drones to track chukar popu lations. The agency once used helicopter flights along the breaks of the Snake and lower Salmon rivers to monitor chukar numbers, but discon tinued the practice because of safety concerns and the high cost of helicopter flight time.

Idaho will continue its pheasant release program in the Clearwater Region this fall. Wildlife managers plan to release about 1,100 roost ers throughout the pheasant hunting season at four dif ferent Access Yes! Hunting access areas. More infor mation about the program is available at bit.ly/3LG4lVz.

The Washington Depart ment of Fish and Wildlife re leases pheasants in Whitman, Garfield and Asotin counties. More information on the pro gram, including release sites, is available at bit.ly/3flOWxp Garfield County is not releasing pen-raised pheas ants this year. The county built a pheasant farm at an old landfill near Pomeroy but didn’t raise birds this year because of other demands on staff time combined with a labor shortage. n

Duck surveys conducted for first time in 3 years

Most numbers collected are below those recorded in 2019 and the long-term average

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

The number of ducks breed ing across the northern tier of the United States and into Canada is down this year compared to both 2019 num bers and long-term average, largely because of drought.

Biologists from the U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service and its sister agency in Canada were able to conduct annual waterfowl breeding surveys last spring. The COVID-19 pandemic grounded the flights in 2020 and 2021.

They estimated a total of 34.2 million breeding ducks in the 1.3 million acre survey area. That represents a 12% drop compared

to three years ago, when 38.9 million breeding ducks were counted, and it’s 4% shy of the average since 1955. The 7.2 mil lion mallards is down 23% com pared to the 9.4 million tallied in 2019 and down 9% from the longterm average. Green winged teal were off 32% with an estimate of 2.17 million last spring com pared to 3.17 million three years

ago. Blue winged teal increased, one of the few bright spots in the survey. Biologists estimated nearly 6.5 million blue winged teal, up 19% from 2019 and 27% from long-term averages.

But duck numbers were up in other areas, particularly at ponds across the prairies of Canada

OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 202218

Idaho Fish and Game

An Idaho Fish and Game employee prepares to release a rooster on one of the state’s wild life management areas.

> See DUCKS, Page 19

Hunters advised of precautions against bird flu

Officials from the Idaho De partment of Fish and Game, along with federal health and agricul ture officials, are advising water fowl hunters to take precautions against avian influenza this fall.

The highly contagious respiratory illness, more commonly known as bird flu, has caused wild bird die-offs in Idaho and other states this year. It can be spread to people or dogs, al though such instances are uncommon.

The U.S. Department of Agri culture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services advises hunt ers to avoid harvesting or handling birds that are obviously sick or birds that are found dead; to wash their hands after handling birds; and to wear disposable gloves when dressing harvested birds.

When possible, the agency advises dressing birds in the field and far from domestic poultry; wearing a dedicated pair of shoes or boots in field dressing areas; or wearing and then cleaning rubber footwear. It also recommends using dedicated tools

and the north central United States. There, counts were 9% above the 2019 estimate and close to average.

“Although the beneficial effects of timely precipitation during late winter and spring were evident by high pond counts across the eastern prairies, the total duck estimate in the Traditional Survey Area was the lowest in nearly 20 years,” said Ducks Unlimited Chief Scientist Dr. Steve Adair in a news release. “The drop in duck numbers reflects the conse quences of low production caused by multiple years of prairie drought, including 2021, which was one of the most severe and widespread in nearly four decades. But the survey revealed some bright spots for duck populations and provided optimism for good production this summer and carryover of favorable pond conditions into fall and winter.”

According to the survey, conditions on breeding grounds in western Can ada and Alaska, where most ducks that use the Pacific Flyway originate, were a mix of good, fair and poor closer to the U.S./Canada border.

Barker is the Outdoors Editor of the Lewiston Tribune. He may be contacted at ebarker@lmtribune.com or at (208) 8482273. Follow him on Twitter @ezebarker.

INSIDE OUTDOORS

while cleaning birds and double-bag ging bird carcasses and rubber gloves used during field dressing. The bagged carcasses should be disposed of in a trash receptacle that domes tic poultry and pets cannot access.

Those who encounter sick birds are advised to contact their state or local health department and closely monitor themselves for cold or flu-like symptoms.

Dogs are not usually at risk of illness from bird flu but there have been some isolated and laboratory instances of transmission to dogs.

Officials set to release pheasants in Clearwater Region

The Clearwater Region of the Idaho Department of Fish and Game is releasing pen-raised pheas ants at four locations this fall.

Hunters are required to register for an access permit prior to hunt ing at the release locations, must have a Game Bird Permit and are required to wear hunter orange.

The department plans to release more than 1,100 birds through December at the Palouse Youth-

Only Area, Peterson Loop Area, Red Bird Parcel of the Craig Mountain Wildlife Management Area and the Genesee Release Area. More information is available at idfg. idaho.gov/hunt/pheasant/stocking.

Washington officials asking public to weigh in on salmon, orca recovery

OLYMPIA — The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is asking the public for feedback to help shape the development of proposed fish passage and screening rules intended to sup port salmon and orca recovery.

The agency will host a virtual public meeting on the topic from 2-3:30 p.m. Oct. 25. According to a news release, the rule-making effort is rooted in recommendations that emerged from Gov. Jay Inslee’s Southern Resident Orca Task Force. In 2018, the task force published its report identifying lack of prey as a key threat to endangered southern resident killer whales survival. The task force specifically noted that the department should develop rules to

fully implement the fishways, flow and screening statutes of the state.

“This rulemaking process will help us further ensure that fish have access to the habitats they need, which is good news for both salmon and endangered orcas,” said Margen Carlson, habitat pro gram director. “Now that we have an updated draft of the rules, it’s a great time to pause and check in with the broader public to make sure we haven’t missed anything.”

More information is avail able at bit.ly/3yx5WYA

UI emeritus professor to speak about species saved by conservation

MOSCOW — University of Idaho emeritus professor Mike Scott will speak about conserva tion-reliant species, using Cali fornia condors as an example, at a meeting of The Palouse Audubon Society on Wednesday evening.

The 7 p.m. meeting will be held at the 1912 Center, 412 E. Third St., Moscow. There is no cost to attend.

FROM STAFF REPORTS

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2022OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022 19

Idaho Fish and Game

Pintails spread their wings as they prepare to land. Duck numbers are down this year, the likely result of drought on some breeding areas in Canada and the U.S.

> DUCKS FROM Page 18

OUTDOORS / HUNTING 2022FRIDAY, OCTOBER 14, 202220

— Eric Barker

— Eric Barker

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

Eric Van Beek

Eric Van Beek