HUNTING AND FISHING EDITION

A special hunting and fishing publication of the Lewiston Tribune and the Moscow-Pullman Daily News

SECTION | THURSDAY, SEPT. 26, 2024

HATCHERY PROGRAMS HAVE DIVERSIFIED > PAGES 4-5

A fly angler casts for steelhead on the Clearwater River near Cherrylane in this Lewiston Tribune photo.

Idon’t think I’ve ever caught a sh on a Fall Favorite — one of the classic steelhead ies (seen above)

Still, I’ve always loved the pattern. With an orange wing, red hackle and tinsel body, it’s sparse but stunning at the same time — not unlike the season it’s named for.

It reminds me of the ery brightness of leaves that will soon change color and the way light shimmers as it bounces o of water on autumn a ernoons. It makes me think of fall days shing for steelhead on the Clearwater River, frosty mornings trailing my dog through a patch of birdy-looking habitat and the way Western larch needles spiral as they fall to the forest oor while I still hunt whitetail deer.

The name also invokes this Ernest Hemingway quote.

“Best of all he loved the fall … the fall with the tawny and grey, the leaves yellow on the cottonwoods, leaves oating on the trout streams and above the hills the high blue windless skies.

He loved to shoot, he loved to ride and he loved to sh.” Papa wrote that for a friend who had died but many people posit that he was thinking as much about his own life as his friend’s. This magazine is dedicated to the love of fall and its abundant sporting endeavors. New this year is the addition of shing to what in the past has been a collection of stories dedicated to hunting. In it you’ll nd some tips and tricks for catching fall chinook and coho; a feature on hunter education instructor Dave Owsley, who has been passing on the hunting tradition to youngsters for more than four decades; a discussion exploring the threat of technology to fair chase hunting; and an elk-hunting essay from my friend and former Tribune reporter Ralph Bartholdt. Give it a look and here’s hoping you nd favor in all your hunting and shing adventures this fall.

— Eric Barker

Containing diseases remains a priority for wildlife managers

By ERIC BARKER LEWISTON TRIBUNE

Idaho’s deer and elk populations, and especially those in the Clearwater Region, appear to be stable.

Wildlife managers continue to monitor chronic wasting disease in units 14 and 18 near White Bird and Slate Creek. The fatal disease represents a major challenge. It can’t be eradicated. Instead, game managers try their best to limit its spread. With that in mind, there are special regulations in place for units 14 and 18 where mandatory CWD testing of harvested and salvaged animals is required. Thus far, the disease has not spiraled outward from a hot spot near Slate Creek. However, CWD has been detected in two other areas of the state.

“Overall, elk populations are looking good. We saw 87% of collared elk calves and 96% of collared cows make it through the winter, which is a few percentages higher than most years.”

— DEER

Despite a long, hot and dry summer, there doesn’t appear to be any significant outbreaks of epizootic hemorrhagic disease in the Clearwater Region. Add to that relatively mild conditions during the 202324 winter and it ought to translate into good survival for deer and elk, according to the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. Many lower- and middle-elevations areas of the Clearwater Region were hit hard with an EHD outbreak in 2021. But populations appear to beginning to rebound. Idaho Fish and Game biologist Kenny Randall reports that the percentage of 5-point

bucks in last fall’s harvest remained strong and harvest was up slightly last year in units 8, 8A and 11A where the outbreak was centered.

The Clearwater Region has some good mule deer hunting, though the best places, like Hells Canyon and the Salmon River canyon, are regulated through controlled hunts. But the big-antlered deer can be found in parts of units 8, 8A, 10A and 15, as well as backcountry units 16A, 17, 19 and 20.

ELK

Randall noted that elk harvest is stable in the Palouse Zone and hunter

success hit a five-year peak in the Dworshak Zone. However, Fish and Game biologists are closely monitoring the zone where elk tag sales are capped and populations are in decline.

Unit 14, in the Elk City Zone, has seen an increase in elk numbers. The Lolo and Selway zones, where elk have been well below Fish and Game objectives for more than two decades, are also capped. Randall noted that elk calf survival is up in some backcountry units and there are places where elk numbers appear to be strong despite decades long downward — perhaps a reason for optimism. From a statewide perspective, Fish and Game

managers are pleased with the health of elk herds.

“Overall, elk populations are looking good,” said Deer and Elk Coordinator Toby Boudreau. “We saw 87% of collared elk calves and 96% of collared cows make it through the winter, which is a few percentages higher than most years.”

BY THE NUMBERS

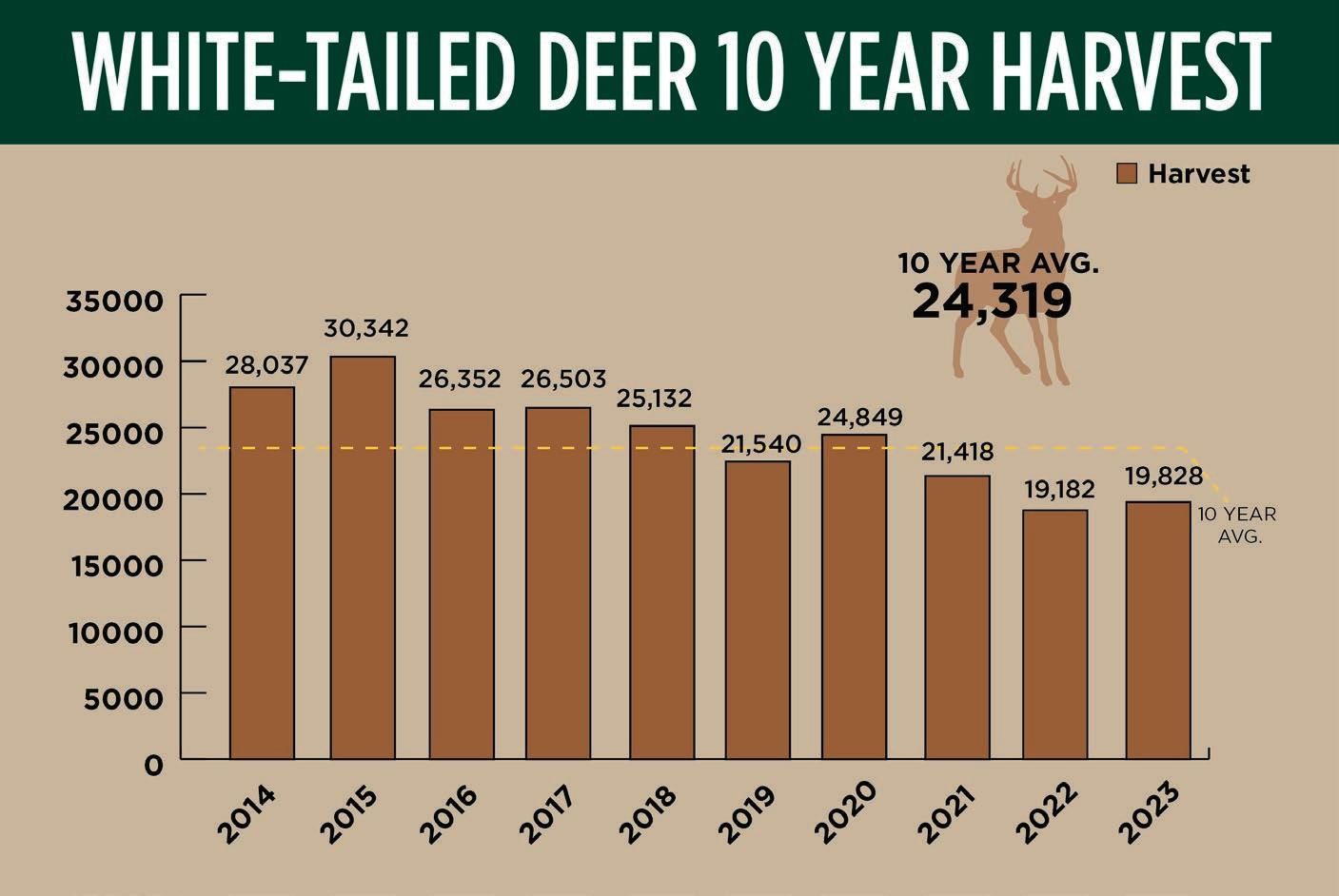

In 2023, hunters in Idaho harvested 18,568 elk, 18,329 mule deer and 19,828 whitetail deer. Elk harvest was down 11% from 2022. Mule deer harvest dropped 22% but the decline was expected because of the deep and lingering snow during the 202223 winter that hammered mule deer herds in the southeastern part of the state.

Whitetail harvest increased by 3% compared to 2022 but was still below the 10-year average.

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273.

hatchery programs have diversified the fishery with fall chinook and coho

By ERIC BARKER LEWISTON TRIBUNE

Not too many years ago, fall fishing in the Snake, Clearwater and Salmon rivers centered almost exclusively on steelhead.

But those days are gone. Successful hatchery programs led by the Nez Perce Tribe have diversified the fishery. Fall chinook and coho now divide the attention of anglers. While neither fishery is brand new, some anglers are still learning how to target kings and silvers.

The Tribune gathered some tips from expert anglers.

The most established fishery for Snake River fall chinook is centered in the confluence of the Snake and Clearwater rivers.

The fish keg up here, likely catching a breather on their way to spawning grounds and taking advantage of the cooler temperatures provided by the Clearwater River.

The season there opens Aug. 18 and has developed into an angling event.

“Opening day, it’s like a frenzy,” said Richard Scully, of Lewiston. “There is like 60 to 80 salmon caught there within a couple of hours, then it slows

LEFT: Mark Edelblute, of Lewiston, holds a salmon he caught on opening day of the fall chinook season last month.

Courtesy

BELOW: Fall chinook, steelhead and coho are returning to the Clearwater, Snake, Salmon and Grande Ronde rivers in decent numbers this fall, and anglers have been eager to catch some.

Frank/ Lewiston Tribune

down but people still catch fish.”

The confluence fishery is largely over now for fall chinook. Yes, fall kings continue to stream over Lower

Granite Dam, some 25 miles to the west. But many of the fish parked in the confluence have moved on.

If you want to give it a shot or file

away some advice for next year, this is how anglers fish the confluence. While a few anglers cast bobber

Continued on Page 5

Continued from Page 4

and jigs from the northwest bank, this is largely a boat fishery and most people troll for them, using plugs behind flashers. Scully noted it’s the predominant technique used from Buoy 10 at the mouth of the Columbia River all the way to the Lewiston-Clarkston Valley.

He recommends a heavy sinker — 10 to 16 ounces — on a slider above a barrel swivel. From there, run a 2-foot bumper — 50-pound test line — to an 11-inch chrome flasher and 3 feet of leader to a plug — usually a Brad’s Super Bait or Yakima SpinFish loaded with tuna and sea salt or other attractant.

“The further you get from the ocean, the more salt seems to be attractive to them,” he said. “Some other ingredients are krill powder and sodium sulfite — for some reason fish like that.”

Troll at slow speeds, just fast enough that the flasher makes a complete revolution, marked by a rod tip bob, every second or so. Scully trolls at about 1.3 miles per hour when headed upstream and 2.2 mph when going downstream.

Instead of a sinker, some anglers use downriggers. Scully recommends trolling in 20 to 30 feet of water near the confluence and deeper downstream in the section of river between Red Wolf Crossing Bridge and the confluence.

“If there is going to be a good bite it’s usually in the first two hours of daylight,” he said.

Trolling is the dominant technique but a minority of anglers are drifting salmon eggs, also called hover fishing, or bobber fishing with eggs.

“The salmon in our rivers just love eggs,” said Toby Wyatt, owner of Clarkston-based Reel Time Fishing. “Once they get up river, they just love roe.”

Chinook are increasingly moving into free-flowing sections of the Snake and Clearwater rivers and bound for the Salmon River. On the Clearwater, Wyatt targets them in deeper holes.

“Anywhere you can find 20 feet of water or more.”

Bank anglers often use bobbers with eggs and those fishing from boats can use divers to get their bait as deep as possible.

“Get as close as you can to the bottom,” Wyatt said.

The fall chinook fishery is gaining a fan base on the Salmon River. In 2018, the Nez Perce Tribe, which has led the reintroduction of fall chinook to the Snake River and its tributaries upstream of Lower Granite Dam, shifted where it releases juvenile fish. The tribe, working with federal fisheries officials, ceased fall chinook releases below Hells Canyon Dam and moved that program to the lower Salmon River. The idea is to monitor how successful fall chinook are downstream of Hells Canyon Dam without the annual influence of hatchery fish.

The Riggins area has benefitted with a fishery that falls into a slot that was otherwise slow.

“It is slowly growing. It has helped our bookings tremendously,” said Roy Akins, owner and operator of Rapid River Outfitters. “The last week of September, I’m booked with day trips.”

Akins said people fishing for fall salmon in the Salmon River often pull Kwik Fish or use plugs popular on the Columbia River. But he sticks with techniques that are more associated with steelhead.

“To be honest, I feel like we have every bit of success,” he said. “It’s

hard to beat little mini Hotshots.”

He targets the sort of water he would expect to find steelhead during the winter — deep pools with a slow current. If you see fall chinook porpoising and rolling, “put your plugs in the water and I would say 70% of the time you are going to get a hit.”

By the time the fish reach the lower Salmon, they are starting to think about spawning. Akins said they will segregate themselves into a handful of pools.

“When you sit in a boat at sunrise, those fish will be rolling. It gives you an idea of what Lewis and Clark witnessed. You will have thousands of fish. You can’t help but just boil with excitement when you see that kind of activity with big fish. It’s like ‘Oh my gosh, this is what it’s supposed to be like, this is why they call it the Salmon River.’ ”

Fall chinook are big bruisers. They can weigh 20 pounds or more. But they migrate upstream during pretty adverse conditions when water temperatures are in the high 60s to mid 70s. They are also in a hurry and, unlike spring chinook and steelhead, they spawn relative-

ly soon after hitting freshwater. All of that can cause their table fare to suffer.

“No matter how pretty they are, they are nothing like a spring chinook,” Scully said. But don’t sleep on them. There are plenty that retain meat quality into October.

“Up until about the 9th (of October), everything you catch is pretty bright,” Akins said.

It’s prime time for coho fishing in the Clearwater River and, to a lesser extent, the Snake. The fish are passing Lower Granite Dam in big numbers and progressing upstream.

Popular techniques include casting spinners and spoons in places they congregate. On the Clearwater, people often fish for them at Spalding near the mouth of Lapwai Creek or near the Kooskia Hatchery at Clear Creek — the two primary places the fish are bound for. Another popular spot is near the Clearwater Paper Mill.

“I think casting Brad’s Wigglers, Fire Tiger color, I think that is the best,” Wyatt said.

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@ lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273.

Numbers are slightly improved but remain below objectives

By ERIC BARKER LEWISTON TRIBUNE

The number of elk available for hunters in the Blue Mountains and river canyons of southeastern Washington is expected to be similar to what they have experienced in the past five years.

That’s bad news. The elk herd there was hit with severe weather in the winters of 2016-17 and 201819. Drought conditions in 2015 and 2021 added to the problem. And elk calf survival has been at record low numbers over the past few years.

Surveys conducted last year showed the herd to be stable, but at a population well below the objective of 5,500 set by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Biologists from the agency conducted survey flights during the first two weeks of March and estimated a population of 3,999. Two years ago, biologists estimated 3,901 elk roamed the Blues. A project monitoring elk calf sur-

vival has shown predators like mountain lions account for about 77% of the mortality experienced by calves during their first few months of life. In the first year of the study, only about 13% of 100 calves survived. In the second year, survival increased to 47%. The agency hasn’t released an update to the monitoring project.

The poor calf survival rates mean there will be fewer spike bull elk available for hunters in the Blue Mountains.

The same combination of harsh winters intermixed with summer drought has also taken its toll on whitetail and mule deer. In addition, periodic outbreaks of blue tongue and epizootic hemorrhagic disease, especially in 2021, have led to population declines and drops in hunter participation and harvest. Biologists are optimistic that conditions may be aligning for the better.

“With good growing conditions last spring and an average winter, we expect overwinter survival was good, and are expecting deer

harvest to marginally improve again through the 2024 hunting season,” they wrote in an annual hunter prospects report.

Pheasant hunters and fans of other upland game birds may be primed for a decent fall. Both the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and Idaho Department of Fish and Game report that weather conditions set up favorably for species like pheasants, chukars, forest grouse and gray partridge.

Biologists with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife predict that mild weather last winter and spring should have led to high survival of upland game birds like pheasants and quail. The wet (but not too wet) spring should have produced good cover, seed crops and insects

that the birds rely on.

“Overall, wild pheasant numbers are likely to be average this coming hunting season,” agency biologists wrote in a hunting prospects report.

They predict hunters should average about 0.7 birds per day during hunting trips this fall.

Pheasant season opens Oct. 19 in eastern Washington. Seasons

for quail, chukar and partridge open Oct. 5.

Biologists with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game said an early and mild spring set upland game birds up for successful brooding and rearing of young.

The weather promoted early growth that was sustained by periodic rain on the Palouse and Camas prairies. Wildlife managers reported seeing large, first and second, broods of birds. Birds like pheasants and quail will sometimes produce a second brood during the spring if weather conditions lead to poor survival of their first attempt.

“Secondary nest production has resulted in large broods of quail throughout many reaches

of the Clearwater, Salmon and Snake Rivers,” Idaho officials wrote in a news release. “Pheasant numbers and brood success appear comparable to previous years. Forest grouse numbers also appear promising and seem to have benefited from mild over-winter and spring conditions. Chukar numbers continue to remain strong this season with large broods observed throughout the breaks of the Snake and Salmon Rivers. Overall, upland hunters should expect another year of good-to-excellent upland bird hunting across the Clearwater Region.”

Idaho’s pheasant season opens Oct. 12 in northern Idaho. Seasons for quail, chukars and partridge opened Saturday.

Longtime hunter education instructor Dave Owsley, whose curriculum is both oldschool and unique, relishes teaching new hunters

By ERIC BARKER LEWISTON TRIBUNE

Muzzles up.

How many times has Dave Owsley uttered that foundational command of firearm safety over the past four and a half decades?

Too many to know. But the 79-year-old hunter education instructor has taught multiple generations of Orofino youth how to safely conduct themselves while handling guns and pursuing game. As the saying goes, he’d be a wealthy man if he had a dollar for each time those two words have crossed his lips. But Owsley isn’t in it to get rich.

“You know, when I go to Lumberjack Days, or I’m in town in the grocery store or something, I’ll have one of these little kids come up and say, ‘Mr. Owsley, I shot my turkey,’ or ‘I got my deer this year.’ So there’s my reward,” he said. “I love the kids.”

Earlier this month, Owsley and another volunteer instructor ushered a small group of mostly 10-year-olds through a weeklong hunter education course. In this part of Idaho and across the rural West, successfully completing the program that involves classroom sessions, tests and a field day is a rite of passage. It’s where kids and sometimes young adults learn the serious business of gun safety, hunting ethics, conservation and some basic outdoor skills. For many of them, it unlocks a lifetime of adventures with family and friends.

But like so many things, it’s a tradition that is evolving. In-person classes are no longer a must. For years, students have been able to take the class online. Gone too is the requirement that students fire live rounds at a gun range.

Owsley has stuck with the traditional format — classroom instruction followed by written tests and a field day with live, super-

vised shooting. But he has added a twist — his signature trail walk.

On a piece of private ground above Orofino, Owsley carved a trail that snakes through timber and presents students with several shoot/don’tshoot scenarios and gun handling challenges. On the trail they see deer scrapes and rubs, shed antlers, game like deer and nongame species like owls, turkey feathers and even some examples of poor behavior such as road signs that have been used for target practice and empty shotgun shells that hunters failed to pick up.

In groups of four, the students in his recent class moved from station to station — .22 rifles in hand.

“Muzzles up,” Owsley reminds them as they embark on the path. Nursing an Achilles injury, Owsley

carefully pointed away and out of the dirt, slip under or step over the barbed wire and pick up their guns while minding the muzzles.

On the trail, the young students are presented with the other safety, legal and ethical situations they are likely to encounter when they hunt for real. A turkey in a clearing with a vertical bank for a backdrop — shoot. A quail in a bush where the backdrop is unclear — don’t shoot. A deer at a salt lick — don’t shoot. Ducks sitting on a pond — here the answer is tricky. It’s not illegal to shoot sitting ducks and the background is clear. But most hunters prefer a more sporting and fair chase challenge, so they flush the birds and shoot them in the air.

Hunter education students (at left) practice fence crossing at a trail established by longtime instructor Dave Owsley (seen above). The trail presents students with various safety and ethical scenarios they must negotiate.

Eric Barker/ Lewiston Tribune

hangs back while the kids are chaperoned by other adults.

The walk starts with a stream crossing so small they could easily step or hop across. But the students use the lessons they’ve learned.

“Unload, unload, unload,” they say repeating another Owsley mantra and then pantomime doing just that. (The guns are already unloaded.) One student hands her rifle to another, crosses the stream and then reaches back across to take her rifle and his so he can cross safely.

They practice the same routine of teamwork at a fence crossing. At a solo fence crossing where they can’t hand off their rifles, they again unload, slide their firearms under the fence with muzzles

The students get to discuss each scenario and determine how they would respond. Owsley designed it so there is not always a right or wrong answer.

“The trail walk is my thing, because I don’t think anybody else in Idaho is doing this,” he said. “I want to make this special for the kids.”

In 1996, Owsley was named the Clearwater Region’s instructor of the year and later earned the same honor for the entire state. That comes with a lifetime hunting license.

This fall, Owsley, with a donation from North Idaho Whitetails Forever, was able to replace the old rifles he has used in the class for decades with new, single-shot .22 Savage Rifles.

“As far as I know, I’m the only person in Idaho who still requires the kids to shoot because it’s not a requirement anymore for hunter ed.”

Owsley doesn’t hunt much these days but he still relishes the fall with its cool, crisp mornings and the changing colors. While finishing the class, he was also readying to head to elk camp in the Sawtooth Zone with his three boys where he will spend a few weeks.

“I’ll be camp cook and camp host,” he said. “I love it.”

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@ lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273.

By ERIC BARKER LEWISTON TRIBUNE

Asouthern Idaho man accused of dozens of hunting violations, including a scheme to purchase and market hunting tags, illustrates the many ways that wealth can be used to manipulate a system designed to be egalitarian.

Karl W. Studer, of Rupert, was charged in Twin Falls County District Court in July with more than 20 violations of Idaho hunting regulations, including six felonies for allegedly poaching trophy elk, moose and pronghorn. Studer and Kevin Siela were also charged with harassing (Idaho code refers to it as molesting) wildlife. The two allegedly made numerous ights in Siela ’s helicopter to scout deer and elk in southern Idaho hunting units. During those ights, the men allegedly caused the animals to ee and sometimes interrupted the lawful hunts of other people. It’s serious business and the allegations are ugly. The men are also accused of using air-to-ground communication to convey the

location of animals to hunters.

But it’s some of the other misdemeanor charges that have raised both the eyebrows and hackles of hunters.

Wildlife is considered a public trust in Idaho and other states. Game animals belong to the state and thus the people, even when those animals live on or are temporarily present on private property.

Idaho makes hunting tags available to its citizens through a complex system. People can purchase over-the-counter tags or apply for highly coveted tags. They can also enter lotteries to win a handful of special tags known as super hunts.

While wildlife is a public resource, the state does reward some large property owners for providing habitat for species like deer and elk. The Landowner Appreciation Program allows people who own at least 640 acres that contain habitat for big game animals to apply for special hunting tags. Landowners who receive the tags, can use them or designate them to somebody else. But they can’t sell the tags. They can however, give the

tags to somebody and then charge that person an access or “trespass” fee.

Idaho Fish and Game conservation o cers, responding to complaints about a red and white helicopter harassing game, eventually sought and received several search warrants giving them access to the cellphones of Studer, Siela and a handful of associates, and all the relevant text, location and mapping data the devices held.

They said Studer spent wildly — nearly $115,000 on Idaho’s lottery for 2023 super hunt tags. He won super hunt tags for deer, pronghorn, moose and elk that allow the holder to hunt in any open unit of the state. No crime there but the state alleges he later used tags belonging to other people instead of his own when he shot deer, elk and moose. The amount of money he spent on super hunt tags illustrates his desire to pursue the state’s monster bucks and bulls in places like hunting units 45, 48 and 52 in southern Idaho’s high desert.

But investigators allege he went further to secure hunting tags to those places. According to charging

documents, Studer paid multiple people, some of whom were also charged, a total $153,000 for various elk, deer and pronghorn Landowner Appreciation Program tags in units 54, 52A, 45, 48 and 52.

In one exchange Studer allegedly discusses the possibility of “ ipping” one of his tags.

While landowners can charge hunters a fee to hunt on their property, investigators said none of the data they obtained indicated the money alleged to have changed hands was for anything but tags.

“Of note, at no time during any tag purchase discussions where they discussing trespass fees. The discussion centered around tags and not trespass rights or fees,” investigators wrote in court documents.

The Idaho Legislature has at times attempted to allow landowners to sell the tags they received. But those e orts have not been successful.

Studer is scheduled to appear at a preliminary hearing Friday.

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@ lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273.

An angler waits for a bite recently on the Clearwater River.

August Frank/ Lewiston Tribune

Expected return to Clearwater River looks especially strong; numbers in other regional rivers should be slightly improved

This story was originally published Sept. 1.

By ERIC BARKER LEWISTON TRIBUNE

The Clearwater River is primed for a fun season of steelhead shing, according to the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.

The river that is known for its strain of big, rod-bending steelhead is poised to see one of its better returns of hatchery steelhead in the last 15 years. But it’s a di erent story for the A-run sh bound for the upper Salmon, Little Salmon

and Snake rivers. That run, which is typically dominated by smaller steelhead, is on pace to match or beat last year’s return — an improvement over the terrible runs during a ve-year span that started in 2018 — but still well below returns in better times. There is a bright side to the A-run, however. It is normally dominated by steelhead that return from the ocean a er just one year in saltwater. This year the run is dominated by steelhead that spent two years in the ocean and the sh, on average, will

be larger than normal.

Joe DuPont, regional sheries manager for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game at Lewiston, said it’s possible more than 40,000 hatchery B-run steelhead will nd their way to the Clearwater and its tributaries. But 30,000 might be more realistic.

Detections of Idaho-bound sh at Bonneville Dam on the Columbia River support the larger estimate but that is only if the sh return according to their longstanding

schedule. In recent years, the sh have been showing up early, which means they peak earlier as well.

“Things are looking mighty ne for the Clearwater,” he said.

Steelhead runs have been establishing an interesting pattern in recent years. The runs have tended to uctuate, with one year favoring sh that spend two years in the ocean and the next year being better for those that spend one year there. For the B-run, that tends to mean better returns in the years that favor two-ocean sh.

For the A-run, which

is typically dominated by sh that spend one year in the ocean, it can lead to ugly returns during the years that favor two-ocean sh.

Unless, of course, the minority of A-run sh that spend two years in saltwater make up the di erence.

DuPont said in a normal year, two-thirds of early run steelhead spend just one year at sea. This year is not normal. Based on detections of hatchery sh at Bonneville Dam, only about 7% of the A-run will be one-salt sh and the rest, 93%, are two-salts. If that ratio holds, it will be the highest since 2016 when 87% of the A-run spent two years in the ocean.

Fisheries managers said in a preseason forecast that about 32,400 wild A-run steelhead would make it to Bonneville Dam this fall and about half of those would return to the Snake River above Lower Granite Dam. The same forecast called for a return of about 4,000 wild B-run steelhead to Bonneville Dam and just 2,900 to Lower Granite Dam on the Snake River. Wild Snake River steelhead are protected as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@lmtribune. com or at (208) 848-2273.

It doesn’t get any more natural than this. Everything out here is organic.

You’re walking a trail that your pupils, wide as dimes, can barely make out using shards of light scraped from the night.

Your learning started 15 minutes ago, the time it took to get the gear together from the back seat and carry it through the chill across the dirt patch of road to the trailhead.

From there you trudged up the path a hundred feet, two hundred feet and then you stopped and listened. You adjusted your bow and your backpack. Checked manually for things like binoculars, knives, bull elk and cow calls, and camo gloves, the gear you’ve learned to pack while keeping the junk to a minimum.

You checked for these by feel because it’s as dark as the inside of a cedar box and your hands are cold as you wait for your eyes to adjust to the night like a cat, and for your pupils to crank open like a can of soup.

In the meantime, you listened for the distant engines of other hunters heading your way so early this morning, and also for the thin, taut bugles of bull elk waing from timber canyons like wind-borne spiderwebs. So faint, curling, li ing, falling, but you didn’t hear any of it.

No rattle-bang of a pickup truck echoed from a mountainside a er being mu ed in a creek bottom before clambering from a washboard road like the pounding of a belt gun. Not yet. You wear three shirts but will shed one soon a er you cut a sweat. On the trail a squeaking, squealing sound stops you. It means the morning breeze has started squirreling in the poke-pole tops of snags,

the ones that rub against standing green trees and the rubbing of the wood is eerie as a slate call.

But it’s natural and not unusual. There is the sound of the wind now, too, in the brushy tops of pine and r, a wooing sound, ghoulish that ends in a hush.

It’s been a while since you heard and recognized the sounds that now come back like old pals who want to scare the bejesus out of you and later laugh about it.

You remove a shirt, roll it tight, and push it into a side pocket of your cargo pants before shu ing up the trail, gaining elevation.

A loud bump and the clatter of stones and then a wheezing hu make you freeze for a moment. A louder hu and then more stomping follows. Deer. They bound downslope away from you, breaking limbs and brush. You give it a rest. You’re breathing hard and so are

the doe and her fawns, as they wonder about you. You wait until the deer trail o . You’re gaining elevation and check your watch.

Another half-hour to the ridge and then another 30 minutes, you surmise, to the big draw that angles downhill to the park. The vague, metallic light that falls around you is accompanied by the mewing sound of a raven somewhere in the trees. Then the wing

Continued on Page 11

Continued from Page 10

pumping swoosh, swoosh, swoosh as the big bird trails you from overhead to get a better look. It lights on a high limb, making a bell sound. All’s OK. Just a hunter heading to the place the elk herd slid over the saddle last night, it seems to say, and another raven perched at a higher elevation mews in return. The call mimics a cow elk. The two birds do this for a minute and then you hear them push off. Their wingbeats fade down the reach to the valley where, through the trees, you see the silhouette of the neighboring mountain that you’ll use as a bearing in the daylight.

Trees squeak in the breeze like yawning hinges. A squirrel skitters up a trunk, its claws scratch the bark, and it chirps.

You’re 2 miles above the trailhead and now, intermittently stopping, you hear an engine accelerate and coast around a turn far below you. The diesel rattles and its cylinders clunk up into the sky through a mist you just now notice. The sky is lighting and you smell the barnyard whiff of livestock, but out here it’s elk. They mucked along in the elderberries hours earlier and left behind their hoof prints in the dust where they crossed the path, noticeable by starlight. In the stiff air, their scent lingers.

Browsed stems glow in the darkness like candle wax, branches and pedicles peeled, chewed and spit out.

After hiking more than an hour, you clamber up and out of the saddle, carrying in one hand your bow by the strings because it’s almost shooting light and you have folded the carrying strap into another side pocket of your pants.

As you hike higher, one step at a time, the organic noises of the night mix with crepuscular sounds, normal renderings of the morning, and the lingering whiff of elk, breeze blown, again criss-crosses your path. It swirls around.

Through the trees, miles away, you see a rural valley and the last flickering of yard lights. You stop for a break and to breathe.

A put-put-put sound seems almost at your feet.

Then an explosion stops your heart for a brief moment. Ruffed grouse. Its blurring wings hop over a ridge and through the trees, carrying

Your sweat cools and dries. A shiver of cold climbs your neck. Then. There

it is. A bull elk squeals through the dawn from what may be a finger ridge to the west.

with it the bird you failed to notice before your nearness frightened it to flight, and it frightened you.

Now you are past the side hill to the benches and the open trees under a dark canopy where you stop. Wipe away the sweat. Listen.

Three miles from the trailhead, maybe more, the nearest road is the one you left.

You’ll wait here for the wind to change or for the high notes of a bugle to whinny through the trees followed by a chuckle.

Your sweat cools and dries. A shiver of cold climbs your neck.

Then.

There it is.

A bull elk squeals through the dawn from what may be a finger ridge to the west.

Then a separate call from a different approach, that one closer.

How many yards away? You measure what you think you know about sound and distance.

From a shirt pocket you lift a diaphragm call as big as a half dollar, place it on your tongue and adjust it.

You decide to move through the shadowy morning when the bulls bugle again, to mask your footfalls and to get a bearing.

Dead reckoning.

You’ll jog in their direction through the half-light as they call, and stop, kneeling in shadows when they pause their calling.

You’ll do it again, returning a mew sound with the diaphragm call you roll on your tongue like a lozenge.

When you stop, you listen.

You’re looking for ambush sites.

Your senses are jazzed.

Bartholdt is a communications manager at the University of Idaho and former Tribune reporter. He also is the author of "Sometime, Idaho," a collection of short essays, and three other books.

Survey shows Minnesota, Wisconsin and North Dakota are down in numbers

By JOHN MYERS DULUTH NEWS TRIBUNE

DULUTH, Minn. — The number of breeding ducks estimated across the continent hit 33.99 million this spring, up 5% over 2023, but nearly all of the increase happened in the far north and west.

That’s the report from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which released its annual spring waterfowl survey results recently.

Among key species, mallards increased 8% from 2023 to 6.61 million, although that number remains 16% below the longterm average. The far northern and western regions accounted for all of the increase. Mallards decreased in every region of the “prairie pothole” region, including an 8% drop in southern Saskatchewan, which historically has more breeding mallards than any other region in the survey.

Wigeon posted the most dramatic change in this year’s survey, up 55% overall to 2.92 million. As with mallards, most of the increase occurred in far northern and western areas of the continent.

Green-winged teal, an important species for hunters in all four flyways, increased by 20% to 3.01 million. Greenwings nest primarily in the boreal forest regions in Canada.

Scaup, commonly called bluebills and which mostly nest in the far north, increased 16% to 4.07 million. Scaup remain 17% below their long-term average.

The survey, completed in May, also estimated 5.16 million total ponds or wetlands, a 4% increase overall. However, the location of those ponds differed greatly from 2023. The pond estimate on the Canadian prairie and parklands, which includes southern regions of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, decreased by

19%. Meanwhile, ponds in the U.S., including Montana and the Dakotas, increased by 49%.

“An increased breeding population of ducks and pair counts, along with wetland habitat conditions that improved throughout May and June with good spring rains across most of the prairies, should help boost duck production,” said Frank Rohwer, president and chief scientist for North Dakota-based Delta Waterfowl. “We definitely have potential bright spots for duck production in the eastern Dakotas and possibly in Manitoba. The spring rains really helped in those areas, as well as parts of Alberta that started the spring quite dry.”

Officials remind hunters that the spring count captured only adult birds and not new ducks hatched and raised this summer. The success of those young birds, coupled with fall weather patents, will largely determine this fall’s hunting season outcomes.

The report details the results from the Waterfowl Breeding Population and Habitat Survey, which has been conducted annually by the USFWS and Canadian Wildlife Service since 1955.

Many ducks winging their way north to Minnesota last spring arrived here early, found little water and kept flying north.

That’s the assessment from wildlife biologists after finding duck numbers way down in 2024 compared to 2023, at least in Minnesota’s prime waterfowl breeding areas.

The 2024 breeding population estimate for mallards was just 141,000 this spring, down 37% from last year and down 41% from the 10-year average.

The estimated blue-winged teal population was 160,000, up 26% from 2023 but 9% below the 10-year average and 23% below their long-term average.

The population estimate for all ducks was 445,000 ducks, 10%

Continued on Page 12

Continued from Page 11

below the 2023 estimate, 30% below the 10-year average and 34% below the long-term average.

The population estimate of Canada geese was 106,000, 7% below last year’s estimate and 31% below the long-term average

“When ducks got here early, with an early spring and early ice-out, there wasn’t that much water on the landscape,” said Bruce Davis, Bemidji-based biologist for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources wetlands wildlife research group. “We were still in drought or abnormally dry conditions across much of Minnesota. We got a lot of rain later in April and May, a lot of flooding even.

... But by then, the ducks had already gone elsewhere. We think a lot of ducks just overflew Minnesota this year to nest somewhere else.”

That means they likely went farther north, into Canada, where production can be lower.

For the ducks that did nest in Minnesota, plenty of water by late May and June should have helped spread them out and increase survival. But ducks that nest close to the water may have had their nests flooded out by rapidly rising waters through June.

“It’s a mixed bag for nesting, probably not great,” Davis said.

Davis said hunters this fall can expect to see a similar hunting season to 2023, but that weather during the season will be, as always, the key factor.

“We may see fewer ducks early with these spring survey numbers, fewer local ducks, but the migration could be great,” Davis said. “It all depends on the weather as the season progresses.”

Minnesota has been producing far fewer ducks, and far fewer duck hunters, over the past 50 years. More frequent and severe droughts combined with a loss of wet-

lands and grasslands where ducks breed and nest are the key factors, Davis and others note. Wetlands and grasslands are lost to agriculture and development, while invasive cattails also choke out wetlands that remain.

Efforts are underway to save and improve habitat in Minnesota, Davis said, but it’s not enough to make big changes in overall duck numbers.

“We would need some major (government) policy changes to get back the wetlands and grasslands that we need to see any serious increase in duck numbers. ... I don’t know how to make that happen,” Davis said.

Hunters in Minnesota, Wisconsin and the Dakotas will see nearly the same waterfowl hunting season parameters as 2023, includ-

ing season length and bag limits. If duck numbers continue to drop, however, season lengths and daily bag limits will likely be reduced in the coming years.

Minnesota’s early teal-only hunting season ran Sept. 1-5, and the early goose season began Sept. 1. A youth waterfowl season ran Sept. 6-7. The regular waterfowl season began Sept. 21.

The North Dakota Game & Fish Department reported spring breeding duck numbers at 2.9 million, down from 3.4 million last year but still 17% above the agency’s long-term average. Mallards, for instance, were down about 19%, pintails were down about 20% and blue-winged teal were down roughly 13%.

North Dakota biologists note that duck numbers

are down as much as 50% from the peak period between 1994 and 2016.

The 2024 early resident-only waterfowl hunting season in North Dakota will begin Sept. 21, and the regular waterfowl season for non-residents begins Sept. 28.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources said their annual spring survey of breeding waterfowl indicated both stable population numbers and habitat conditions for migratory birds.

Surveyors estimated the state’s breeding duck population to be 502,058 birds, a 3.7% decrease from the 2023 estimate but above the long-term average.

The mallard breeding population estimate is 146,561 birds, 7.9% lower compared to 2023 and lower

than the long-term average.

The wood duck population estimate was 96,711 birds, similar to last year and above the long-term average.

The Canada goose population estimate was 153,402 birds, similar to 2023 and significantly higher than the long-term average.

“In addition to positive survey results, the wet conditions across the state should provide excellent brood-rearing opportunities for waterfowl throughout the remainder of the summer,” said Taylor Finger, DNR game bird ecologist.

Wisconsin’s early teal season ran Sept. 1-9, and the early Canada goose season ran Sept. 1-15. Youth waterfowl weekend was Sept. 14-15, and the regular waterfowl season in the northern zone began Sept. 21.

Technology advancements such as Wi-Fi-connected game cameras and high-powered scopes are changing the way people pursue game

fair chase standards. The Idaho Fish and Game Department is asking hunters where the line should be drawn.

At what point does technology eliminate the sporting element from hunting? A committee of Idahoans will soon grapple with that question

By ERIC BARKER LEWISTON TRIBUNE

Consider the hunting equipment a hypothetical grandfather or great-grandfather used in his youth. He likely hunted in allwool clothing. If he used a scope, it was low-powered. The same goes for his binoculars. His rangefinder wasn’t a handheld device that bounced a laser off of a distant object. It was internal — a best guess honed by experience. He may have shot a mass-produced military rifle “sporterized” for civilian use.

Now ponder the technology his descendants have available. His granddaughter may use a precision, custom-built

rifle with a high-powered scope that, with a lot of practice and dedication, is accurate at 1,000 yards. His grandson may mask his scent with the latest hunting clothes made from synthetic fabrics and use live feed, Wi-Fi-equipped trail cameras that ping his phone when the monster buck he is stalking trips a motion sensor. Have the hypothetical grandchildren crossed some technological Rubicon that threatens to put game populations in jeopardy and turn hunting into a lifelike video game? Or are they taking advantage of the same sorts of technological advancements their grandparents did in

their youth — upgrades that would have blown the minds of ancestors who hunted with muskets and longbows?

A select group of Idahoans will soon ponder those sorts of questions and author a set of recommendations for the Idaho Fish and Game Commission to consider. The commission directed the Idaho Department of Fish and Game to assemble a Hunting and Advanced Technology Working Group.

Commissioner Don Ebert looks forward to the group’s report but knows it will be a challenge. The members will have to grapple with ideas like fair chase that are nebulous and subjective.

“It’s based on values and where do we draw the line collectively of what is moral and right and what will perpetuate the species?” he said.

“When I was a kid, there weren’t very many people with guns that could shoot 800 yards and now there are people who shoot farther with their bows than I would shoot with my rifle — freehand with a rifle, I’m only good for like 125 yards. It’s a pretty hard line to draw.”

Ethics can be tricky even when technology is not involved. For example, Idaho allows black bear hunters to use bait. Washington does not. But Washington does allow hunters to bait deer and elk. In Idaho, that is illegal and considered unethical.

Questions about technology don’t just apply to modern rifles. Many states allow muzzleloader hunters to use sabots. Idaho considers them a technological advance that expands the range of the old-school guns to the

point they don’t meet the primitive weapon definition that muzzleloader-only hunts are designed for. Modern compound bows with cams, high-tech sights and stabilizers are a far cry from traditional stick bows.

For Kyle Maki, the pivotal metric is the point at which a particular piece of technology begins to affect hunting success rates enough that game managers have to change season structures and limit hunting opportunity.

In general, Idahoans can participate in most biggame hunting seasons on an annual basis with hunting tags that are available over the counter. Yes, there are controlled hunts for which participants must first win a permit via drawing. Some

Continued on Page 15

“... It’s one of those things: Where do you draw the line? Who is right? Who is wrong? So much of it comes down to ethics.”

—

Continued from Page 14

elk zones have a capped number of tags sold on a first-come, first-served basis. But resident hunters who don’t draw a controlled hunt permit or are not able to obtain the exact elk tag in the exact zone they desire can largely fall back on other open hunts. Maki wants to keep it that way.

“Something is going to happen. Either we are going to keep doing what we are doing and animal populations start to change, or we can get out ahead of it,” he said. “I would much rather see more weapon restrictions rather than losing opportunity to hunt. I think that is where a lot of sportsmen fall. Sportsmen want the opportunity to hunt every year.”

Maki represents northern Idaho for the Idaho Wildlife Federation and has applied for a seat on the technology working group.

He is not alone. More than 760 people submitted applications to participate in the group tasked by the Idaho Fish and Game Commission to “assess public perspectives on what is and is not considered ‘fair’ technology to use in the pursuit of game and develop recommendations to the Commission that strike an appropriate balance between the use of hunting technology and fair chase ethic.”

“I think it just speaks to the timeliness of the issue. It’s an issue not just being discussed in Idaho, it’s being discussed nationwide,” said Ellary TuckerWilliams, legislative and community engagement coordinator for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game at Boise. “People are discussing it around campfires and around kitchen tables with friends and family.”

Maki said his organization doesn’t have a particular stance on any of the myriad ways technology can aid hunting but it wants to be part of the discussion.

“We are just very encouraged the department is looking into this and is trying to address it before it becomes a bigger issue down the road.”

Technology itself doesn’t always inherently represent an advantage. For example, improved scopes and precision rifles can make hunters remarkably accurate from astonishingly long distances. But it’s not automatic. In most cases, it requires a significant degree of dedication and practice from the hunter. Maki notes that some technology — rangefinders and precision scopes or advanced bow sights, for example — can allow people who embrace them to take longer but more accurate shots.

“They might have a better chance at making a clean, ethical kill at that extended range versus someone who picks up a rifle and only takes a couple of practice shots (before heading out),” he said. “It’s one of those things: Where do you draw the line? Who is right? Who is wrong? So much of it comes down to ethics.”

That question is likely to fall on the commission. TuckerWilliams notes the group will come up with a set of recommendations and one possible outcome is that it doesn’t advocate any changes to current rules. The group, once it is pared down by the department, will begin meetings and is expected to forward recommendations to the commission by March.

Ebert knows technology seemingly happens at the speed of light. He hopes the group is able to start a process that will lead to an enduring set of principles.

“I hope the group comes up with a set of guidelines that will cover all technology and put some side rails on things we may not have even thought about yet.”

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@lmtribune.com.