The Good Life: CHRISTIANITY AND A MORAL VISION

ON CRATERS AND DEATHWORKS

Jack Carson

HUMAN RIGHTS AND CHRISTENDOM

Rebecca Munson

THE BIRTH OF MODERN WESTERN MORALS

Forrest Strickland AN INTERVIEW WITH ALISTER MCGRATH

Fall 2024 Joshua Rice, Creative Director Heidi Schieber, Marketing Director Seth Bingham, Marketing Manager Emma Linker, Project Coordinator Deanna Sattler, Designer Dave Parker, Senior Writer FACEBOOK/LibertyUACE | X-TWITTER@LibertyUACE | envelope ACE@liberty.edu | location-arrow Liberty.edu/ACE “The Good Life: Christianity and a Moral Vision” Faith and the Academy: Engaging Culture with Grace and Truth 8, no. 1 (2023-24): A publication of Liberty University Center for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement.

14

JESUS IS LORD: HOW THE TWO-WORD GOSPEL DEFEATED THE ETHOS OF ROME

Bryan Litfin

36 SHAME AND SEXUAL FREEDOM: LEARNING THE LESSONS OF HISTORY

David Pensgard

43 PILGRIMS, ACTIVISTS, AND ARTISTS

Chris Hulshof

60

BOOK REVIEWS

FAITH AND THE ACADEMY: ENGAGING THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH i

8 On Craters and Deathworks

Jack Carson, Director of the Center for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement, Liberty University

14 Jesus Is Lord: How the Two-Word Gospel Defeated the Ethos of Rome

Bryan Litfin, Professor of Bible & Theology, John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

20 Human Rights and Christendom

Rebecca Munson, Associate Professor and Department Chair, Helms School of Government, Liberty University

27 The Birth of Modern Western Morals

Forrest Strickland, Instructor of History, College of Arts & Sciences, Liberty University

32 An Interview with Alister McGrath

Alister McGrath, Emeritus Andreos Idreos, Professor of Science and Religion, Oxford University

Jack Carson, Director of the Center for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement, Liberty University

36 Shame and Sexual Freedom: Learning the Lessons of History

David Pensgard, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, College of Arts & Sciences, Liberty University

43 Pilgrims, Activists, and Artists

Chris Hulshof, Associate Professor of Religion, John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

4

ii

Contents

48 C.S. Lewis and the Moral Argument

Edward Martin, Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies, College of Arts & Sciences, Liberty University

53 Public Health and the Goodness of Christ

Benjamin K. Forrest, Professor and Administrative Chair, School of Health Sciences, Liberty University

BOOK REVIEWS

60 Disability and the Gospel: How God Uses Our Brokenness to Display His Grace

Elyse Pennington, Student Fellow, Center for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement, Liberty University

61 A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918

Joseph Dennis, Student Fellow, Center for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement, Liberty University

62 Herman Dooyeweerd: Christian Philosopher of State and Civil Society

Josh Hicks, Student Fellow, Center for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement, Liberty University

63 Suffering Wisely and Well: The Grief of Job and the Grace of God

Chase Matthews, Student Fellow, Center for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement, Liberty University

5

FAITH AND THE ACADEMY: ENGAGING THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH iii

Training Champions for Christ since 1971

Editorial

Jack Carson Executive Director

Center for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement

John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

On Craters and Deathworks

“America is a Christian country,” one student loudly proclaimed. Another student, clearly agitated by this declaration, raised his hand immediately. This student quickly countered, “How can you say America is a Christian nation when abortion is legal? It seems like our country’s laws are pretty opposed to Christian values.” Not to be outdone, the original student responded with equal vigor, “Our nation was founded on Christian principles. It isn’t perfect, but neither are Christians.”

Some variation of this conversation occurs in my cultural engagement courses each semester. Our students are caught between conflicting accounts of Western culture’s moral fabric, oscillating rapidly between strong declarations about its Christian heritage and even more stringent declarations about its moral degeneracy. The paradoxical tension that our students intuitively feel when attempting to understand the Western world’s moral conscience is not simply a result of limited information. They have, instead, stumbled upon a deep tension in the task of modern Christian cultural engagement. In this editorial, we will look at the nature of this tension, exploring both “the crater of the Gospel”1 in our society and the “deathworks” that have weaponized these craters against Christianity’s claims to authority.2

The First World

The sociologist Philip Reiff divides the Western world into three distinct epochs — or “worlds.” These epochs are distinguished from one another by radically divergent authority structures — fate, faith, and fiction. The “First World” was committed to the authority of fate. The transcendent rulers of this first world ranged from “the complex rational world of ancient Athens to the enchanted mysticisms of aboriginal Australia.”3 The authorities of this First World could be described as “metadivine and often rooted in a mythical understanding of Nature, its gods myriad and its power primordial, capricious, and overwhelming.”4 Each version of the First World established “god-words” which carried with them a trace of transcendent authority.5 These “god-words” established the virtues and taboos of ancient cultures. For Sparta, pride and strength became god-words. For ancient Athens, wisdom itself was a god-word.

The First World was dominated by the concept of fate, where the relationship of the transcendent world to the mortal realm was one of manipulation and control. Human rituals were centered on convincing the divine realm to shift fate — a sacrifice to bring the rain, a cleansing to avoid punishment. Morality was

8

less about conforming to a way of life and more about “the regulation of passions by nonnegotiable taboos.”6 Breaking these taboos could bend fate against you or even anger a god.

Second-World Revolution

This world of fate was replaced by the Second World, which Reiff largely associates with monotheistic religions in general and the Judeo-Christian heritage in particular.

The leitmotif of our second culture/world is nothing miasmic or primordial, nothing metadivine and impersonal. In a word, faith, not fate, sounds the motif of our Second World. Faith is in and of that creator-character that once and forever revealed Himself in the familiar words from Exodus 3:14: "I am that I am." Faith means trust and obedience to the highest most absolute authority: the one and only God who acts in history uniquely by commandment and grace.7

The Second World rejected the god-words of the first world, taking aim at its idols and rituals. A key feature of the Second World's revolution was the indictment of all vestiges of First-World allegiance. It was not sufficient to affirm the second world’s God; every god of the First World must be renounced. Witchcraft, divination, and occult practices are anathema in the second world, specifically because they signal allegiance to the old structures of the First World’s fate authority. Instead of disconnected, primordial powers, the Second World’s transcendent authority is a personal God who is interested in the lives of humans. The taboos of the First World, then, were replaced with the moral indictments of the Second World — the Ten Commandments replacing the oracles of Delphi.

As Christianity gained prominence in the ancient world, it ushered in a series of societal changes through the transformation of “god-words.” The idea of “wisdom,” which Athenians so valued, was disconnected from the form of Athena and brought into submission to the revelation of the God of Israel. Strength was reformed around the image of the cross. The values of antiquity were overturned and redeemed by Christianity. Class distinctions, once transcendentally supported by the authority of fate, were called into question by faith in Christian revelation. Infanticide of the disabled or unwanted, practiced in many portions of antiquity, was shown to be unthinkable. The Christian God was interested in the moral actions of individuals, and no amount of ritualistic sacrifice could convince God to overlook sin.

Interlude: The Development of Craters

Christianity’s victory over the various ancient mythologies strongly shaped the moral sensibilities of modern culture. The legacy built by the Church over the past two millennia provided the foundational building blocks of Western liberal democracy.

In some ways we live among the ruins of this legacy: the foundations of early modern liberalism are still there, under the rubble; on top of them, we have created the flimsy, flashy construction of the late modern self and identity politics. We can't let this deformative individualism obscure the good, healthy, biblical affirmation of the individual that emerged in Christendom.8

Every society answers basic moral questions and balances competing moral claims. These questions are inherently religious and invoke answers that rely on concepts of meaning, significance, and authority:

Who am I? Do I matter? Do others matter? Does it matter how I treat them? Why does it matter how I treat them? Who has the right to answer these questions? What if I disagree with that answer?

The intuitive manner in which our modern Western society answers these questions is distinctly shaped by its Christian heritage. As the philosopher Oliver O’Donovan explains, even the most secular societies invoke transcendent categories in basic, everyday interactions: “The false self-consciousness of the would-be secular society lies in its determination to conceal the religious judgments that it has made.”9 Our modern society, even in extreme secular manifestations, is operating on borrowed religious capital when answering moral questions.

The citizens of the modern Western world all agree on certain moral positions — slavery is wrong, humans have rights, and the law should be applied equally to all people. These moral sensibilities have been ingrained in the fabric of society through the faithful and habitual lives of Christians over the past two millennia. As Christians create culture, they inevitably shape the form of that culture. The rationality of Christians begins to “rub off” on the culture, promoting a distinctly Christian view of the world. This form of influence is not predicated upon any sort of coercion; instead, it takes place through habitual and embodied actions. The explanations and justifications of Christians, moored as they are to the truths revealed in Scripture, offer a compelling and comprehensive way

9

FAITH AND THE ACADEMY: ENGAGING THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH

to understand humans and their role in life. By simply being salt and light, the Church changed the moral fabric of Western culture over a prolonged timeframe. These “craters” operate at a pre-cognitive level; they are deep, subterraneous commitments. Oftentimes, moral sensibilities are assumed in everyday conversation and moral disagreements; they operate as the terrain of disagreement and are rarely the subject of disagreements themselves. People reason from these moral sensibilities to decide between competing moral positions. In this sense, we might call moral sensibilities something like “moral tastebuds.” They operate powerfully under the surface to shape what we assume to be rational, reasonable, and good. To put a particular point to it: A commitment to human flourishing is a moral sensibility; a stance on the rightness of a particular entitlement program operates as a moral position.

There are countless ways that Christianity has shaped the moral sensibilities of our world, but here are three key “craters” of the Gospel. First, the modern concept of freedom is derived from Christian ideals. Predictably enough, the foundation of our Second-World politics is the discovery of freedom, which in its modern form is a distinctly Christian contribution.10 O’Donovan explains that “God has done something which makes it impossible for us anymore to treat the authority of human society as final and opaque.”11 God’s Kingdom relativizes all other kingdoms. If Christians are responsible before God, any other responsibility they have must be secondary. This claim introduces a new social reality, one where each person has responsibility for managing their own life well. There is no monarch who can intercede for you, save that Monarch who intercedes for all. This religious commitment to individual responsibility undergirds our modern commitment to freedom.

A second key contribution is seen in the modern conception of restrained justice. While the justice of antiquity was often akin to revenge, the entirety of our modern judicial system has been shaped to guard against unbridled retribution. Our modern concept of justice requires balancing judgment with mercy. The punishment has to “fit” the crime. This too reverberates from Christian theological commitments. The end goal of discipline is repentance and restoration, and Christian thinkers and jurors shaped their own writing to “point” at this deeper version of justice. As O’Donovan explains, “When asked to say what that pointing might consist of, Christian thinkers could only reply that it involved the restraint of force to the minimum necessary. An imprecise answer, but

one which has had some profound effects on Western Civilization.”12 The modern drive for mercy is one of those “eternal valuations” that Fredrich Nietzsche blamed on Christianity.13

A third key moral sensibility inculcated by Christianity has been the affirmation of human equality. The modern commitment to equality is predicated on the assumption that all people have inherent dignity, and this assumption is suspiciously absent throughout most of human history. Only a doctrine like Christianity’s Imago Dei could support such a belief. Most societies have tied the worth of individuals to their competence, connections, or class. The Imago Dei, however, requires the worth of humans to be based on their inalienable standing before God. The baker and the senator are equal in worth, no matter their class or capabilities. O’Donovan explains how this development led to the eventual downfall of institutionalized slavery: “The distinctive Christian contribution … lies in the conviction that the Church itself was a society without master or slave within it, and that this society of equals was so palpably real that the merely legal and economic relations of master and slave had only a shadowy reality beside it.”14 This ontological commitment to radical equality within the society of the Church put existential pressure on the entire system of rationality that supported the institution of slavery.

These three moral sensibilities are part of a large set of instincts that Christianity has instilled in the Western liberal world. The concept that the government is morally responsible for acting rightly toward its people,15 the instinct that the government rules under the law and not as its own law,16 the legal-constitutional conception that the right to govern is founded on the consent of the governed,17 and the right of the populace to speak directly into the formation of law18 are all identified by O’Donovan as legacies of Christian presuppositions.

Deathworks and the Third World

The prevalence of Christian rationality in our modern society’s moral sensibilities is generally a boon in Christian public witness. However, Philip Rieff has demonstrated how it has also led to an unprecedented problem. While the First World was governed by the transcendent idea of fate and the Second was governed by faith, the Third World has rejected the conception of a transcendent moral order in its entirety — it has labeled the idea of authority as a “fiction.”

When Nietzsche famously declared that God was dead, he ushered in an era of uncertainty. Humans had, in the entirety of recorded history, referenced a transcendent

10

order to make sense of the world. Without that reference point, Nietzsche insisted that humankind operated as the true source of meaning. The process of creating narratives and counternarratives is what generates significance, unmoored from any real reference point.19 This assault on the idea of transcendent authority leaves behind only one transcendent idea — that transcendence itself is a fiction. All gestures toward transcendence are de facto power plays; all claims to some real basis for morality are oppressive.

Fiction, however, is formed out of disassembled reality. Every fictitious story uses words and ideas that are real, and the Third World operates the same way. It disassembles the First and Second World and reassembles them, in a never-ending series of recreations. The Third World’s transcendence is negation — the rejection of transcendent authority in its entirety. This leads to a world in constant moral turmoil. As Reiff explains, “Culture becomes a warring series of fragments, that series unified by no common motif and dominated best by self-legitimating elites that try to set up their own fiction of primordiality against other fictions that they think have already had too long a run in an otherwise meaningless history.”20 The Third World weaponizes the stories of the First and Second worlds to promote the idea that “nothing is true.”21 Pitting transcendent ideas against one another, the Third World attempts to desacralize the sacred. In other words, as Nietzsche envisioned it, the Third World institutes a revolving door of “anticultures,” where a parade of competing anti-theses rotate through the public consciousness at a rapid rate.22

And here enters the most powerful weapon in the Third World's arsenal of negation: the deathwork. To banish the Second World’s influence on modern moral sensibilities is not as easy as it was for the Second to banish the First’s authority. The Second had a transcendent order with which to supplant the First, but the Third has no transcendent order. Instead, the Third recreates accounts of morality using the broken pieces of First- and Secondworld orders in Frankenstein-like configurations. This leads to a world formed by what Michael Foucault called “the principle of reversal” and what Nietzsche termed the “transvaluation of values,” a world that is self-legitimating and self-creating.23

These deathworks operate by narrating a new story surrounding meaning and significance, and they do so by retooling the “craters” of the Gospel that Christianity has formed. This, in turn, creates chimeric positions in the moral landscape that contain both Christian truths and negations of those very truths. In the rampant debates on abortion, for example, the value of bodily autonomy — a Christian concept stemming from the value of

individuals — is pitted against the value of life — another fundamental Christian concept. Disconnected from the Christian story that organizes these values into a coherent system, the resulting clashes often seem like little more than Nietzschean narrating and counter-narrating. In discussions surrounding LGBTQ rights, the supremacy of love is pitted against the Christian sexual ethic. In debates around gun control, the value of peace and gentleness is pitted against natural obligations to defend one’s family.

This means, in practical terms, that our students will feel the intrinsic draw of Christian truths contained in the variety of competing moral positions. This can lead to confusion, frustration, and, ultimately, despair. Moral truths begin to look inaccessible and illusory, and the third world’s transcendent fiction takes hold. Simply teaching them to reject one set of positions is untenable; those positions contain fragments of Christian truth. Instead, faithful modern cultural engagement requires careful, diligent, and patient evaluation of the complex moral landscape of our world.

Recapturing a Vision of the Good

Careful analysis is necessary, but it is not sufficient for the task at hand. The weaponization of disconnected moral truths plays a central role in the Third World’s game. When moral truths are weaponized without reference to a transcendent order, they begin to operate as tools for power plays. If our moral sensibilities are subsumed into the cultural battles of the day, they take on the role prescribed by the Third World. This, in turn, simply lends credibility to the authority of “fiction.”

Instead, the Church in our late-modern world must remember the transcendent order behind our moral sensibilities. Our prophetic witness cannot be formed out of disconnected “natural” moral truths; prophetic witness in our late-modern age needs to be of a distinctly Christian nature and in constant reference to the transcendent order revealed in Scripture. Christian moral positions are not free-floating pieces of disconnected argumentation. Instead, Christian morality is irrevocably tied to the person, work, and revelation of Jesus Christ. Our theology provides the rationality that orders our morality, and giving up on the distinctive nature of our theological commitments in favor of functional wins in culture will ultimately undermine the very foundation of those moral commitments.

To Train Champions for Christ who are prepared for this complex world, we do not need to teach them how to argue against every iteration of the fictitious Third World. Instead, we need to teach them about the

revelation of Christianity and how it informs the moral commitments we proclaim; in other words, we need to clearly articulate a vision of “the good life,” centered on the person and work of Jesus Christ. This is easier said than done. There is a real temptation to respond in outrage to every iteration of the Third World zeitgeist. After all, if Reiff is right, the Third World is committed to the authority of fiction, and it can feel gratifying to attack the absurdity of its latest positions. However, as soon as one iteration of the Third World is defeated, another will inevitably arise. If Christian cultural engagement is framed in reaction to this hydra of fiction, our stance will be shaped by what we are against rather than what we are for, and our witness to “the good life” will be lost in the heat of never-ending outrage.

1James Smith, Awaiting the King.

2Philip Rieff, My Life among the Deathworks: Illustrations of the Aesthetics of Authority, Sacred Order/Social Order, (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006).

3Reiff, XXI.

4Reiff, XXI.

5Rieff, 5.

6Reiff, XXI.

7Rieff, 5.

8Smith, 110.

9Oliver O’Donovan, The Desire of the Nations: Rediscovering the Roots of Political Theology, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 247.

10O’Donovan, 252.

11O’Donovan, 253.

12O’Donovan, 260.

13Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil: The Philosophy Classic, Capstone Classics (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2020), 113.

14O’Donovan, The Desire of the Nations, 265.

15O’Donovan, 231.

16O’Donovan, 233.

17O’Donovan, 240.

18O’Donovan, 240-241.

19Ron Dart, “Myth, Memoricide, and Jordan Peterson,” in Myth and Meaning in Jordan Peterson: A Christian Perspective, ed. Ron Dart (Bellingham, WA: Lexham, 2020), 53.

20Rieff, My Life among the Deathworks, 26.

21Rieff, 27.

22Rieff, 42.

23Rieff, XXIV.

13

FAITH AND THE ACADEMY: ENGAGING THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH

Dr. Bryan M. Litfin Professor of Bible & Theology

John W. Rawlings School of Divinity

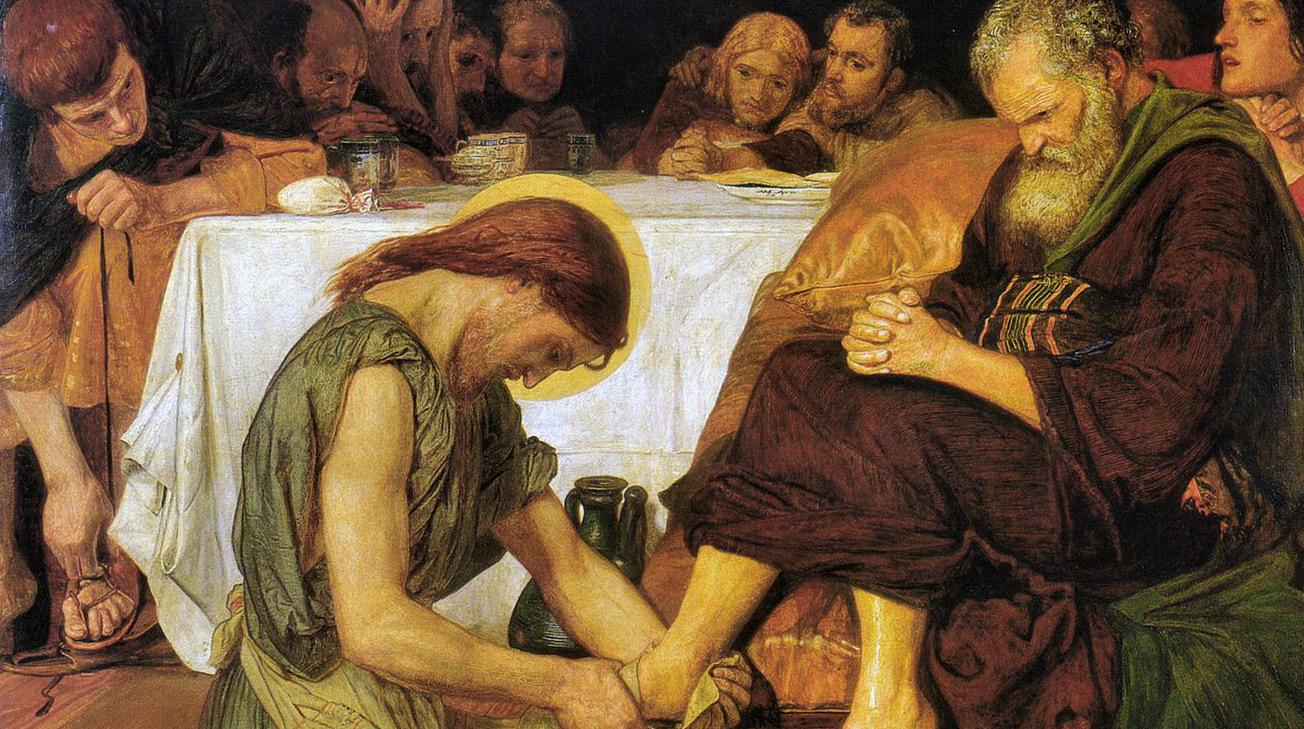

JESUS IS LORD: HOW THE TWO-WORD GOSPEL DEFEATED THE ETHOS OF ROME

The foundational myth of ancient Rome recounts how the city’s founders, the twins Romulus and Remus, were cast away as orphans yet survived because a shewolf suckled them. The image of the lupa (female wolf) became an enduring symbol of Rome. In particular, the wolf was sacred to Mars, the red-blooded god of war. The people of that ancient city, which grew into a republic and then an empire, were deeply lupine: intelligent, cooperative, and noble, yet also savage, ravenous, and dominant. The disciplined Roman legions, like innumerable, invincible wolfpacks, kept expanding their territory until the whole Mediterranean basin lay under their sway. The Roman worldview perceived everything outside itself as either prey or threat. Violence toward them both — impulsive, swift, and ruthless — was Rome’s inborn instinct.

And then along came the puppy of Christianity.

Yes, a puppy. An insignificant new religion, cute in a juvenile way but hardly a threat to the wolf’s dominance. The puppy stumbled and bumbled underfoot, sometimes giggled at, sometimes cursed, but most often ignored. It poked its nose here and there, trying to figure out its place in the wolf’s expansive domain. Nobody paid it much attention. It was too small to matter.

But then the puppy began to grow, its limbs lengthening, its frame filling out. Soon it could no longer be ignored by the wolf, which started to snap at its new competitor, at times biting hard. Blood was spilled, yet the adolescent dog didn’t run away. It kept confronting the wolf, protecting its own flock and even reclaiming some lupine territory as its own. Eventually, the sheepdog grew larger and stronger than the wolf: a noble Great Pyrenees, brave and steadfast, swathed in white wool like the lambs it guarded. Awed by this majestic beast, the wolf cowered, lost its will to fight, and shrank back into the darkness from which it had come.

How did this happen? How were the wolfish values of the empire — an insatiable hunger for conquest and ceaseless expansive violence — defeated by the Christian ethic of love and mercy? The answer: through the tireless work of the ancient church fathers — the pastors and teachers of Christianity’s first five centuries. If you haven’t met them yet, it’s time you did.

Getting to Know the Church Fathers

Church history, of course, didn’t end with chapter 28 of the Book of Acts. Nor did it duck its head and go underground until it resurfaced in 1517 when Martin Luther tacked the 95 Theses on the door of a German church.

Rather, church history continued marching ahead from the first century into the second, then the third, the fourth, the fifth ... and all the way to the twenty-first. The figures of those first five centuries are called the church fathers, defining what historians refer to as the “patristic” era (pater is Latin for father). Of course, there were many great Christian mothers as well, but we use the term “fathers” as a catchall term for the earliest phase of church history when foundational figures sired a long lineage of believers to come.

Who were these church fathers and mothers? Some of them are familiar names: Augustine of Hippo and Athanasius of Alexandria. Others are more obscure: Irenaeus, Tertullian, Macrina, John Chrysostom, Melania the Elder, and Basil of Caesarea. Several of the great ones died as martyrs, like Ignatius of Antioch, Justin Martyr, and Perpetua. Others were longlived churchmen, monks, and bishops. Many were outstanding scholars with brilliant minds: Origen, Jerome, Marcella of Rome. A few were even prominent Christian statesmen, such as Ambrose of Milan.

Despite their many differences — their social stations, ethnicities, countries of origin, outlooks, and final ends — they all had one thing in common: they stood

14 Faculty Contribution

united against pagan Rome and what it had to offer. Sure, the fathers of the patristic age could ransack Greco-Roman literature for its valuable tidbits, discovering usable truths that could be redeployed for God like the Israelites of the Exodus reforged Egyptian gold for tabernacle service. Not everything produced by a wicked culture is wicked itself. Even pagan soil is impregnated with seeds of the Logos. The fathers believed those should be nurtured into life.

Yet at the core of their beliefs, the ancient Christians held that the worldview of Rome stood in stark contrast to their own. The two systems were diametrically opposed. The Roman moral vision was to invade, conquer, subjugate, tax, and move on to the next ripe picking. But when the Spirit of Christ came to the empire, it lost its urge to dominate — so much so that Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire laid the blame for the fall upon the wimpy shoulders of the Christians and their pie-in-the-sky concerns.

But was this really a “fall”? Only if the domineering violence of Rome is valorized as worthy of perpetuation. Perhaps we can instead describe what happened as a moral and ethical transformation, an interior renovation of a culture’s heart that led to wholesale societal changes. An ethic of agape — selfless love for the human race — entered a society where it was absent before. And it did this, not by introducing a gospel message, but by switching which gospel was being preached.

What Is a “Gospel”?

We think of the Gospel as a religious thing. It’s a very “Christiany” word, isn’t it? Every pastor talks about it. Every church wants to embody it. Every blogger defines it. Every missionary proclaims it. The Gospel is at the heart of Christianity. Surely this is a biblical word, right?

Yes, it is. But before it was Christian, the word had a life of its own.

The Greek word euangelion — Latinized as evangelion, Anglicized as the evangel — has it roots in war and conquest. Long before Jesus Christ walked this earth, Greek and Roman people were proclaiming the gospel of victory. Literally, this word combines the prefix for “good” (eu-) with the word for a “message” or “announcement” (angelia). Thus it means “good news,” or specifically, the public proclamation of your king’s victory after a battle and the establishment of his new kingdom to replace the defeated one.

Did you know that one of the world’s first evangelists wasn’t a Christian but the great Roman emperor, Caesar Augustus? At the end of his life, he erected an inscription across the empire (basically, he commissioned billboard advertisements everywhere) which touted his many victories and achievements. This massive propaganda piece, totaling 4,000 words in English translation, was known as the Res Gestae, which means “Things Accomplished.” Such proclamation of mighty deeds was a gospel message. In fact, another famous inscription from 9 B.C. says, “the birthday of the god Augustus was the beginning of the good tidings (euangelion) for the world.”

All of this serves as the background to the Christian appropriation of the word “gospel.” The earliest believers also had a message of good news. It wasn’t simply a description of personal salvation, a means by which individual people could “get saved” by their decision of faith. The gospel doesn’t start with a personal problem and then provide a strategy for its rectification.

Rather, like any gospel announcement in the ancient world, it starts with a proclamation of royal victory over a defeated regime. And right along with this proclamation — inherent within it, in fact — is a demand for all hearers to offer willing subjection to the new king. Those who resist the victor will find his

message to be bad news. However, those who embrace him will hear good tidings and begin to flourish. Only then will their sins be forgiven by grace. Only then will they begin to be saved, enduring to the end to gain a share of the victor’s crown. But the present decision that the hearer must make isn’t the primary substance of the gospel. Nor are its future ramifications. What comes first in a true gospel proclamation is an announcement of a finished work in the past: the Things Accomplished by the Lord who has won the battle.

The Ancient Church’s Two-Word Gospel

Though we tend to complicate the Gospel, it’s actually very simple. The ancient Christians (including the apostles, but also the generations afterward) confessed it in only two words: Kurios Iesous, “Jesus is Lord.”

This was no light thing to say, no mere slogan of polite respect. To be a “lord” (kurios in Greek, dominus in Latin) was a big deal in the Roman Empire. Why? Because the basic affirmation of imperial homage — indeed, of emperor worship — was “Caesar is Lord.”

To be a loyal citizen of Rome and all it represented required hailing Caesar as the supreme ruler of all.

But early Christianity turned that lordship acclamation on its head, giving allegiance not to a man who became a god but to God who became a man. The apostle Paul

16

wrote, “If you declare with your mouth, ‘Jesus is Lord,’ and believe in your heart that God raised Him from the dead, you will be saved” (Romans 10:9). This twoword Gospel could be confessed only when the Spirit Himself gave utterance (1 Corinthians 12:3). Although one king seemed to rule, the new Christian truth revealed that another one — the true King — actually reigned supreme.

What was the meaning of this two-word Gospel?

It wasn’t simply a confession that Jesus had died on Calvary to save us from our sins. The church fathers knew that the death of Jesus didn’t save anyone. In itself, the cross is empty of power. The shed blood of Christ, at the moment when it dripped from His brow, His hands, His feet, and His side, accomplished absolutely nothing for our salvation.

Does that sound shocking? Perhaps it does. I understand that. Even so, it is true. Don’t take my word for it. Take the words of inspired Scripture: “[I]f Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile; you are still in your sins” (1 Corinthians 15:17). Do you see? The cross alone isn’t what saves us. The cross is the bad news that the Savior has been wickedly slaughtered by the Romans. It is a cause for the devil’s rejoicing. But when the deadly cross is overcome by the empty tomb — aha! Now the saving power of God has been revealed! Only then do we receive “His incomparably

great power for us who believe.” This is exactly the power that “He exerted when He raised Christ from the dead and seated Him at His right hand in the heavenly realms, far above all rule and authority, power and dominion, and every name that is invoked, not only in the present age but also in the one to come” (Ephesians 1:19-20). No longer is “Caesar” the lordly name to be invoked by humankind. Why not? Because of the two-word Gospel: Kurios Iesous Forever and always, Jesus is Lord.

Witnesses in Blood

Did the ancient Christians of the patristic age understand this? I think we could say they understood it better than anyone ever has. And I use the word “understand” in the deepest possible sense. The early Christians had internalized the two-word Gospel so much that they were willing to die for it. Their bold confession, of course, ran afoul of emperor worship. In those days, it was a capital crime to impugn the emperor’s majesty. That is why the age of the church fathers was often an age of martyrdom.

Consider, for example, the story of Polycarp, the second-century bishop of Smyrna, one of the Seven Churches of Revelation. Polycarp was arrested during an imperial pogrom against the Christians. “What’s the matter?” the judge asked him. “What harm is

17 FAITH AND THE ACADEMY: ENGAGING THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH

there in saying ‘Caesar is Lord’ as you make a little sacrifice and do what’s required? It’s the only way to save your life!”

But Polycarp knew what he believed and drew a firm line in the sand. Hauled before the judge in Smyrna’s amphitheater, he was ordered to swear loyalty to Caesar.

“If you think I’m going to do what you’re asking and swear to Caesar’s demon, you’re mistaken,” Polycarp replied. “But since you keep pretending not to know who I am, hear me declare boldly: I am a Christian!”

The elderly martyr also declared about Christ, “For eighty-six years, I have been His servant, and He has done me no wrong. How could I now blaspheme my King who saved me?”1

“My King who saved me” — the Risen Christ, not the emperor in Rome.

Upon that regal yet illegal confession, Polycarp was hauled to the stake for burning. The soldiers also stabbed him with a dagger, a vicious and fatal wound. The noble martyr’s blood gushed into the sand of the arena while his soul ascended to the skies for his heavenly reward — a reward bestowed from the hand of the true cosmic Lord.

Patristic Presence and the Defeat of Rome

In the end, the Roman wolf wasn’t defeated by a bloody dogfight. The stalwart sheepdog didn’t need to leap at his enemy with his ears laid back and his fangs bared. He didn’t growl and bark and engage in physical combat. That just wasn’t his way.

Instead, the ancient Christian sheepdogs — the forefathers and foremothers of our faith — defeated the ferocious, rapacious, voracious worldview of Rome through their steadfast presence and their unwillingness to be dislodged by adversity or even death. At first, they endured persecution, sometimes to the point of shedding blood. Even in the face of danger, they kept worshiping God, strengthening their churches, and doing apologetics against the pagan gods.

Then, when one of the emperors, Constantine by name, decided to convert to their faith, the Christians rose to the task of counseling him in statecraft and catechizing him in sound doctrine. Admittedly, the temptation accompanying that strategy was to become wolfish. As the ancient proverb says, “If you run with wolves, you will learn how to howl.” That’s not a good

thing. The Church doesn’t need to howl. Legitimate critiques can be made of how the Church erred during this era.

Nevertheless, contrary to popular perception, the main story of the post-Constantinian church wasn’t one of capitulation but of transformation. The ancient church fathers didn’t abandon ship after the emperor converted. They had spent far too much of their blood, sweat, and tears to let that happen. The ship of faith continued to sail along its same trajectory, now running before the cultural winds instead of beating windward. It was a welcome change, one that allowed tremendous cultural transformation to occur.

And thus, in time, pagan Rome became Christendom. For all its flaws, that Christianized society raised a torch of love and mercy whose brightness the world had never seen. The Western moral vision produced by Christianity gave humanity its greatest gift: individual rights rooted in the dignity of every person. This couldn’t have happened without the first Christian generations summoning the courage to challenge the wolf, defang it, and send it slinking away so the lambs of God could flourish in the green pastures of the Lord.

1 Bryan M. Litfin, Early Christian Martyr Stories: An Evangelical Introduction with New Translations (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2014), 60.

19

FAITH AND THE ACADEMY: ENGAGING THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH

Faculty Publication

Rebecca Munson, Ph.D. Associate Professor & Department Chair School of Government, Liberty University

Human Rights and Christendom

Rooted in the premise that each individual human has unique dignity, equal worth, and divinely ordained purpose, Christendom’s picture of human rights enjoys widespread popularity and acclaim. Christianity’s “standard of beauty” for rights prevailed over that of its Greco-Roman rivals, rivals that ascribed rights to duty and social status. Routine exploitations of slaves and the poor were widely accepted in classical conceptions of morality, even as some Roman jurists noted how slavery was an issue where natural law collided with the laws of nations.

There are many reasons why Christendom’s picture of rights won out over its historical rivals. The first is its natural allure. Equality, perhaps the most unique component of the modern, Western human rights project, resonates with the conscience and divinely imprinted senses of right and wrong on the human heart.

Today, the equality and individualism responsible for the allure of modern human rights are under attack, from both within and outside the Western world.

Subjectivity & Human Rights

Internal challenges center around the subjectivity associated with human rights. Subjective rights often implicate a “me-first” individualism and moral relativism, and this has led to dramatic expansions in the definition of what constitutes a human right. Westerners are now under the illusion that individual preferences have no effect on the collective health of a society and human rights have become a stage for contemporary culture wars.

The very individualism and equality that Christians once cherished as exceptional and meaningful contributions to the concept of rights are now the same elements to blame for subjective rights. This is why some Christian thinkers lambast theologians as “naïve in their facile appropriation of ‘rights talk,’” appropriations which allowed human rights to become embedded into the Christian social conscience.1

Incredibly, some religious scholars go so far as to suggest that political rights as a whole are a doomed project, one which cannot be biblically substantiated. The underlying fear is that rubber-stamping modern human rights means capitulation to a set of liberal values incompatible with moral teachings and religious institutions. However, the existence of a multifaceted philosophical debate over moral justifications for rights does not negate the reality that the Bible speaks to individual rights. Think, for example, of the laborer receiving his due wage. And, of course, that famous commandment against stealing.

Christians can and should take much of the credit for human rights. Their doctrine elevates the lowly and gives dignity to the oppressed. Prior to Christendom, even the most sophisticated societies, such as the Romans, had no problem with practices like coerced prostitution so long as the prostitute was part of a low societal group. It was not until classical conceptions of justice and morality gave way to Christian conceptions that we see prostitution portrayed as a sin, a fundamentally wrong violation of human dignity.2 Theodosius II, a Christian emperor, endorsed a new law in A.D. 428 to ban coercion in the sex industry. This law, considered a turning point in Western sexual ethics, introduced the concept of sin to the masses.3 The morality of human behavior was no longer predicated on what society viewed as appropriate. It was reframed as a matter decided in light of what God viewed as appropriate.4 These and other radical Christian ideas about the value of individuals slowly transposed into European law, starting under imperial Rome and throughout the Middle Ages.

Political Power & Human Rights

This leads to another reason why Christendom’s ideas about rights triumphed access to political power. Ambiguous concepts of rights, attractive and true as they might ring, are hard to exercise until they become political.

20

Consider, for example, how the evangelical awakening of the 18th century was followed by numerous humanitarian acts of the British parliament, including the prohibition of slavery and laws that forbade children from working in factories. As Protestant Welsh minister Martyn Lloyd-Jones put it, “Once men are right with God, they get right with one another.”5 But notice that it took acts of Parliament to ensure good ideas translated into actual protections for the vulnerable.

Likewise, when it comes to international human rights, attractive ideas are by no means solely responsible for the sprawling legal architecture that buttresses the modern human rights project. Powerful countries have been willing to use their military and economic weight to back up human rights commitments.

Modern human rights are the product of a complex interplay between good ideas and the right applications of political, military, and economic power. This can be seen clearly by tracing the rise of the abolitionist movement.

The Protestant Reformations can be given disproportionate credit for the idea that slavery needed to end. Even though the Bible does not condemn slavery as an institution, there is repeated focus on the duty of the Christian to defend the oppressed. Still, it took quite some time for abolitionist calls to emerge. In his homily on the book of Ecclesiastes, the fourth-century Cappadocian Father Gregory of Nyssa was the first to say that the institution of slavery was sinful, basing his argument on the idea that Christ actively identified with slaves when He died by crucifixion the slave’s death. However, it was not until the 18th and 19th centuries that church leaders began to seriously question the institution of slavery itself.6 Acclaimed historian Tom Holland, whose contributions are highlighted elsewhere in this volume, suggests the emergence of the idea that the Christian God wanted slavery to be abolished was due to the confluence of two circumstances.7 The first was the Protestant Reformation, which supported Christians reading Scriptures for themselves without a Catholic intermediary. New interpretations of Scripture fostered the idea that slavery was morally wrong.

Holland argues the second reason the abolitionist idea took hold is that in the Caribbean and North America, slavery had become both industrialized and racialized. Britain had become highly adept at extracting raw materials and slaves, which they often treated with

astonishing cruelty.8 Mortality rates on plantations were skyrocketing, and the sheer horror of abuses was becoming difficult to explain away. The concurrent racialization of slavery made it even more difficult to claim that slavery was biblical.9

The Quakers, followed by evangelical Episcopalians and other Protestants, launched what we in the 21st century might call an advocacy campaign. The Quaker-inspired 1787 British Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade began petitioning Parliament. Under the leadership of William Wilberforce, abolitionists finally saw the fruits of their labor in 1806 when the Foreign Slave Trade Act flew through the British House of Commons.10 In the House of Lords, the bill faced more challenges, but eventually, the noisy and persistent abolitionists succeeded. Their righteous clamor even put slavery on the agenda for parliamentary elections in 1806.

Changes in Britain’s material circumstances had paved the way for abolitionist ideas to gain political traction. The French Revolution, which had recently ended in 1799, reduced British competition in the West Indies. The French had also recently lost control over sugar plantations in Haiti. These developments eased concerns over how abolition could impact Britain's commercial interests. In 1807, a new bill finally banned British participation in the slave trade. Another bill came in 1833 which abolished slavery in Britain altogether.

By the end of the Napoleonic wars, Holland contends the French foreign secretary negotiating in Vienna had no choice but to demand that the slave trade be abolished.11

At this juncture, Catholic countries were also compelled to become abolitionists. International laws started to emerge prohibiting the transatlantic slave trade, laws which gave the British navy the latitude to unilaterally seize the slave ships of other Atlantic powers. The British and French even forced the Ottoman Empire to start regulating their slave trade.12 Like any human rights campaign, abolitionist advocacy turned potent when it landed on the agenda of a powerful country, one with the military and economic might needed to compel other countries to accept new formulations of appropriate, civil, and just behavior.

For centuries, Christianity has shaped secular impulses toward justice. However, missionaries did not end the transatlantic slave trade. It was the Royal Navy. Today, it is not advocacy groups or Christian missionaries doing the most to eradicate modern slavery. It is the U.S. Department of State, which harnesses America’s economic strength to impose economic sanctions on countries that fail to meet their commitments to combat human trafficking.

22

Well-intended individuals and advocacy groups are not directly responsible for the Kuhn-esque, episodic progress that peppers the history of human rights. Progress is due to political revolutions, religious revivals, the agendas of imperial powers, the outcomes of major wars, and eras of great power competition (such as the Cold War).13 It was bloody political revolutions which rendered expansions in political rights in the 18th and 19th centuries. It was a victory in the Second World War which gave the Allies the authority required to design an international system that codified Christian ideas about human dignity into international laws enforced by strong powers. The failure of communism, as historian Samuel Moyn points out, opened up the space for a new utopia after previous utopias failed.14

Ideas have power, so it is critical that popular ideas are good ideas. But ideas have their limits. Economic and military power mattered greatly when it came to embedding the West’s moral vision into practice. While it is not through military and economic strength alone that the Western consensus on human rights has solidified, strength has certainly helped. This is the part many Christians are squeamish to acknowledge.

Human Rights in a Pluralist World

Critics of human rights are correct that today’s expansive interpretations of human rights fail to align with the religious doctrines that helped found them. Consider, for example, how freedom of religion is now used as a banner to justify barbaric practices of widespread female genital mutilation in certain countries. Or how Christian concepts of free will and bodily autonomy are used to justify abortions.

Enlightenment-era thinking, with its focus on natural law and natural rights, is often blamed for subjective rights. But, subjective rights were not the exclusive invention of the Enlightenment. More broadly, it is difficult to scrupulously argue that the Enlightenment even signifies a true break from religion.

Ample space exists for another interpretation, one that acknowledges a great deal of continuity between Christian and Enlightenment thinking. Witte and Latterell, for example, suggest that attaching subjective rights to the Enlightenment cannot accommodate the realities of how the modern liberal formulation of rights was anticipated by the Romans, visible in medieval canon law, and acknowledged by 16th- and 17th-century Protestant reformers.15 Their point is that today’s expansive interpretations of rights were anticipated. Subjective interpretations of rights are not a departure from the

Christian roots of human rights. They are the product of the continuity across Christian and Enlightenment thinking.

Going one step further, an embrace of Tom Holland’s thesis in Dominion leaves space to argue that the Enlightenment itself was a product of Christianity.16 In other words, liberalism is Christian in its origins. It is a particular, pluralist manifestation of Christian ideas. Lumping in critiques of human rights as part of a failure of liberalism thus becomes a narrow-minded line of critique. A rejection of Holland’s thesis would leave us in a far messier world, both historically and philosophically.

One way to see both the philosophical tensions and historical continuity in modern human rights is by looking at the articles that comprise the 1948 United Nations Declaration of Human Rights (UNDHR). Because the UNDHR is widely regarded as the crown jewel of 150 years of striving after rights, historians have tended to focus on the 1940s when they try to describe the emergence of human rights. Encompassing a strange mixture of principles, some of the UNDHR’s articles bolster conservative political stances while others advance progressive causes. Article 1 hearkens to Christian doctrine, declaring how humans are not just “born free and equal in dignity” but also “endowed with reason and a conscience,” meaning they “should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”17 However, the language in the preamble mimics the Enlightenmentinspired, liberal language found in the opening lines of the French Declaration of the Rights of Man. Protestant influence in the UNDHR is perhaps most visible in Article 18, where “everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion.”18 Yet in Article 22, we see overt assertions of economic, social, and cultural rights, the kinds of rights conservatives today challenge as contradictory to biblical principles of limited government.19

Social rights, which Franklin D. Roosevelt cemented both internationally and domestically under the Atlantic Charter and UNDHR,20 were understood at the time to be important for preventing another Great Depression, the kind of domestic economic woes blamed for the rise of Hitler. Many people in the 1940s believed that avoiding another Great Depression would mean avoiding another Hitler. World peace was tied to individual economic and social rights.

New receptivity to social and economic rights birthed expansions in the kinds of rights people conceived of as fundamental, expansions that gained momentum during the 1960s civil rights movements. The glamour

associated with modern human rights came in the 1970s.21 In the 18th and 19th centuries, rights had been attached to revolutionary nationalism. Bold chartings of social and economic rights in the UNDHR show how the 20th century took rights much further. Even though conservatives tend to now view the UNDHR with suspicion, it is still widely considered the cornerstone of the Western consensus on human rights and is littered with language that hearkens to religious doctrines.

Christians can and should take credit for the ideas of individualism, equality, and human dignity that define modern human rights. The Protestant Reformation broke the unity of Western Christendom and carved a path for the liberal ideas that freed millions from serfdom and sparked steep declines in extreme poverty across the globe. Victims had no respect in the cruel worlds of antiquity. Their voice in politics today is due to the impact of Christianity on the Western world’s moral vision. All Christians can regard human rights as a net gain for civilization, and yet, they should not be surprised when rights are interpreted in ways that grind against religious doctrine.

People of all persuasions must now navigate the practical and political manifestations of competing religious and liberal interpretations of rights. When tensions manifest in concrete contexts, the way to resolve them is to address them on a case-by-case basis. Attempts to resolve tensions in more abstract ways entail expansions in governance, expansions which either endanger principles of limited government or encourage reversion to antiquated authority structures. The political left is pinning its hopes on new forms of authority with its reliance on “experts” and bureaucrats to create societal stability. Simultaneously, the right is panting for reversion to old, theocratic forms of authority, the very types of authority structures that Protestants purposefully broke away from to find the freedom to worship God as they saw fit.

Both of these undemocratic reactions promise stability. In reality, each devalues the individual by assuming people need the government to tell them how to make choices that complement the common good. Undemocratic responses to clashing interpretations of rights risk not just the entirety of the human rights project but also the entirety of the experiment of liberalism. Neither is something that should be risked at such a pluralist moment in politics, especially when serious external challenges to human rights loom, namely, China’s aggressive bids to implant its dangerous collectivist definition of human rights into high politics.

1Joan O’Donovan, “Rights, Law and Political Community: A Theological and Historical Perspective,” Transformation 20 (Jan. 2003), 31. O’Donovan argues theologians adopted human rights based on “a consensus about the unproblematic nature of the move from human dignity to human rights,” 31.

2Kyle Harper, From Shame to Sin: The Christian Transformation of Sexual Morality in Late Antiquity (Harvard University Press, 2013).

3The passage of this same law is also a key historical moment in the development of Christian concepts of free will. See Harper 80-133.

4Harper, 7-8.

5Martin Lloyd Jones, “The Message of the Bible Today.” Sermon on Exodus 20:1-26 delivered Nov. 27, 1955. https://www.mljtrust.org/ sermons/old-testament/the-message-of-the-bible-today/.

6Kimberly Flint-Hamilton, “Gregory of Nyssa and the Culture of Oppression,” Christian Reflection: A Series in Faith and Ethics, 2010: 2636. Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University.

7Tom Holland, interview with Michael Jones, “What if Christianity Never Existed? With Historian Tom Holland,” Inspiring Philosophy, podcast audio, April 21, 2023, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/ inspiring-philosophy/id1683977797?i=1000610161979.

8Ibid.

9Ibid.

10Interestingly, this bill was initially framed as a national security measure, which helped inoculate it from proslavery arguments. See Jenny Martinez, The Slave Trade and the Origins of International Human Rights Law (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 22.

11Holland, interview with Michael Jones.

12Holland goes so far as to argue that what follows from this is a Protestantization of Islam. He also discusses how Protestantism imposed abolitionist narratives on Catholicism.

13Samuel Moyn offers a thorough treatment of these developments in The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History (Cambridge and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010).

14Ibid.

15John Witte Jr. and Justin J. Latterell. “Christianity and Human Rights: Past Contributions and Future Challenges,” Journal of Law and Religion 30.3 (2015): 353-385.

16Tom Holland, Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World (New York: Basic Books, 2019).

17“Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” Documents, United Nations, Article 1, http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-humanrights/.

18Ibid, Article 18.

19Ibid, Article 22.

20See Elizabeth Borgwardt, A New Deal for the World: America’s Vision for Human Rights, (Cambridge and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005): 14-46.

21Few international agreements can boast genuine influence on the nature of international relations apart from the Treaty of Westphalia.

25

FAITH AND THE ACADEMY: ENGAGING THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH

SEND US YOUR STUDENTS

Let the Center

for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement

equip your students to address today’s most challenging social and cultural issues with humility and wisdom through its Student Fellows program.

Students from all academic disciplines can participate. Applications are available at Liberty.edu/ACE.

Forrest Strickland Instructor of History College of Arts & Sciences, Liberty University

The Birth of Modern Western Morals

What explains the astounding shift in morality — in the definition of goodness — that occurred between the culture of the Spartans, who considered the weak to be unworthy of life, to the modern Western world? Despite many secular arguments that Christianity has been (and perhaps even remains) only a hurdle that must be overcome for progress to be made, several historians and political thinkers over the past decade accomplished the laudable task of reminding us that without Christianity, the world we live in would be far bleaker. Larry Siedentop, for example, detailed how the rise of Christianity in the West reshaped institutions and legal codes, creating modern Western liberalism, in which each person is seen as having fundamental human rights, as opposed to the “might is right” of nonChristian kingdoms.1 A similar argument came from Brian Tierney in 1997, who made clear that the idea of individual rights emerged from church lawyers, not from secular Enlightenment thinkers.2 John Witte Jr. has ably demonstrated how the teachings of John Calvin were applied to political questions throughout early-modern Europe and led to the rise of Western constitutionalism.3 Similar studies have shown how to care for the least of these (orphans, widows, and the destitute), scientific studies, and many other values we cherish today, most of which are taken for granted, emerged due to the influence of Christianity.

How did Christianity, a religion grounded upon the unjust execution of a Jewish carpenter, come to shape entire civilizations’ understandings of morality and virtue? Humanly speaking, few would have expected a religion based on Jesus’ crucifixion to have a revolutionary effect, let alone inform ethical frameworks to such an extent that the impact of Christianity would grow to shape Western moral assumptions to such a degree that it becomes intuitive.

The Christian Revolution

Tom Holland sought to answer the question, “How do we explain the moral shift that takes place from antiquity to today?” in his 2019 book Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World. Holland’s answer is simple,

and he demonstrates it through a series of twenty-one episodes in Western history, starting with an analysis of Athens in 479 B.C. and Jerusalem in 63 B.C. to set the stage for how Christianity would dramatically reshape the moral assumptions of the world.

Holland is a fascinating author. After completing his undergraduate education at Cambridge University, he began his doctoral studies at Oxford. He quickly grew frustrated with higher education, especially the monastic poverty that often accompanies it. He pursued a career as a writer and in broadcast, both radio and then television. He is a successful writer of influential historical documentaries, and he co-hosts The Rest Is History, a highly popular history podcast. He is the author of many award-winning historical books on antiquity, not to mention a 2015 translation of Herodotus’ The Histories

And yet, neither his academic acumen nor his cultural significance as a popular educator of history are the ultimate reason, for me at least, why Holland’s work as the author of Dominion is fascinating. For Holland, Dominion is not a mere academic exercise that seeks to understand the past disconnected from the author’s own interests. Holland acknowledges this is a deeply personal study. He was raised around Christian teaching, but as a child, he had serious doubts about Christianity.

In a 2016 article in The New Statesmen, Holland recounted how as a child in Sunday School he could not reconcile Christian teaching with scientific evidence.4 He was naturally curious about ancient civilizations. Even reading the Bible became an exercise in understanding the ancient civilizations who often feature as enemies of God’s people: Egyptians, Assyrians, Babylonians, and Romans. He became enamored by the gods of Greece and Rome, who seemed far more compelling than the God of Israel.

Nevertheless, Holland eventually became haunted by the morality of the ancient world and was struck by

27 Faculty Contribution

how different it was from our modern understanding of goodness.

The longer I spent immersed in the study of classical antiquity, the more alien and unsettling I came to find it. The values of Leonidas, whose people had practiced a peculiarly murderous form of eugenics, and trained their young to kill uppity Untermenschen by night, were nothing that I recognized as my own; nor were those of Caesar, who was reported to have killed a million Gauls and enslaved a million more. It was not just the extremes of callousness that I came to find shocking, but the lack of a sense that the poor or the weak might have any intrinsic value. As such, the founding conviction of the Enlightenment — that it owed nothing to the faith into which most of its greatest figures had been born — increasingly came to seem to me unsustainable.

In the three centuries after Christ’s death, countless Christians were faithful in the ordinary task of sharing the good news of the crucified King with family, friends, and neighbors, so much so that Christianity eventually overwhelmed much of the Roman Empire, with a Roman emperor, Constantine, taking up the mantle of being the first Christian emperor. Monarchies, in the wake of the fall of Rome, took up Christian imagery to legitimize their reigns.

A Winding Path

Few things demonstrate Holland’s main thesis more than how modern observers have come to understand the conquests of the Americas by European powers. It ought not be surprising when fallen, sinful people act in a way that is exploitative, including those who do so under the banner of the Cross. But, Holland notes, what ought to be astounding is the way we take for granted our modern moral compass. By what standard is it wrong to subjugate those who are weaker than you? Many societies viewed it as a moral necessity to conquer their weaker neighbors. But Holland argues that Christianity has, over time, brought about a marked shift in the moral framework of the world. In an interview with Dan Carlin, Holland explains “... when the Spaniards conquered Mexico, of course there is a sense of triumph — the idea that God has given them this world, and it redounds to the glory of Spain, and it is something to celebrate. But there is a nagging sense that what they’re doing is offensive to God.”5 For many modern people, including Christians who are sobered by the inconsistencies and hypocrisies in Christianity’s history, it can be tempting to distance ourselves from the Christians of the past.

28

While the treatment of the native peoples in the Americas is a glaring example of Christian hypocrisy, it is crucial to remember that our moral condemnation of the European monarchies is itself predicated on Christian moral claims. Christians may have a checkered history, but Christian theology has operated strongly to shape Christians and non-Christians alike. For example, Bartolomé de las Casas (1474–1566), a Spanish conqueror who helped develop mining and agriculture in Hispaniola, became a priest in 1514 and eventually came to the conclusion that Spain’s actions in the New World denied the image of God in native peoples.6 He was, through Christian reasoning, formative in arguing against the mistreatment of native peoples.6

Similarly, it was Christians like William Wilberforce and John Newton who passionately and forcefully argued that it is an affront to the image of God in another person to take them as a slave. Christians have been at the forefront of the fight against abortion, seeking to protect the least of these, for the last fifty years.

The Christian understanding of “doing unto others as you would have them do to you” and caring for the least of these has been so imbibed by the Western moral mind, argues Holland, that we now use Christian moral categories to consider the goodness of acts done by those in the past who often professed to be Christians.

Looking Forward

Can the understanding of goodness that emerged from centuries of Christian influence, an understanding which even now marks much of the 21st century West, remain, despite the erosion of that Christian influence? Holland ends Dominion with a similar question.

If secular humanism derives not from reason or from science but from the distinctive course of Christianity’s evolution — a course that, in the opinion of growing numbers in Europe and America, has left God dead — then how are its values anything more than the shadow of a corpse? What are the foundations of its morality, if not a myth?7

A host of philosophers and political thinkers have asked the very same question, from Nietschze to Charles Taylor. Many have concluded that Christian values will inevitably die off if Christianity wanes. Some in the secular West are actively seeking to divorce themselves from the authority of a Creator

29

God who has particular demands on each individual’s life, and this divorce will inevitably erode the moral sources that undergird our modern sensibilities. Moral commitments like loving one’s neighbor and caring for the helpless are not self-sustaining. They rely on the ontological commitments that Christianity provides. Taylor, in his landmark work, A Secular Age, argued pointedly that the values the West cherishes will not survive after the erosion of Christianity.8

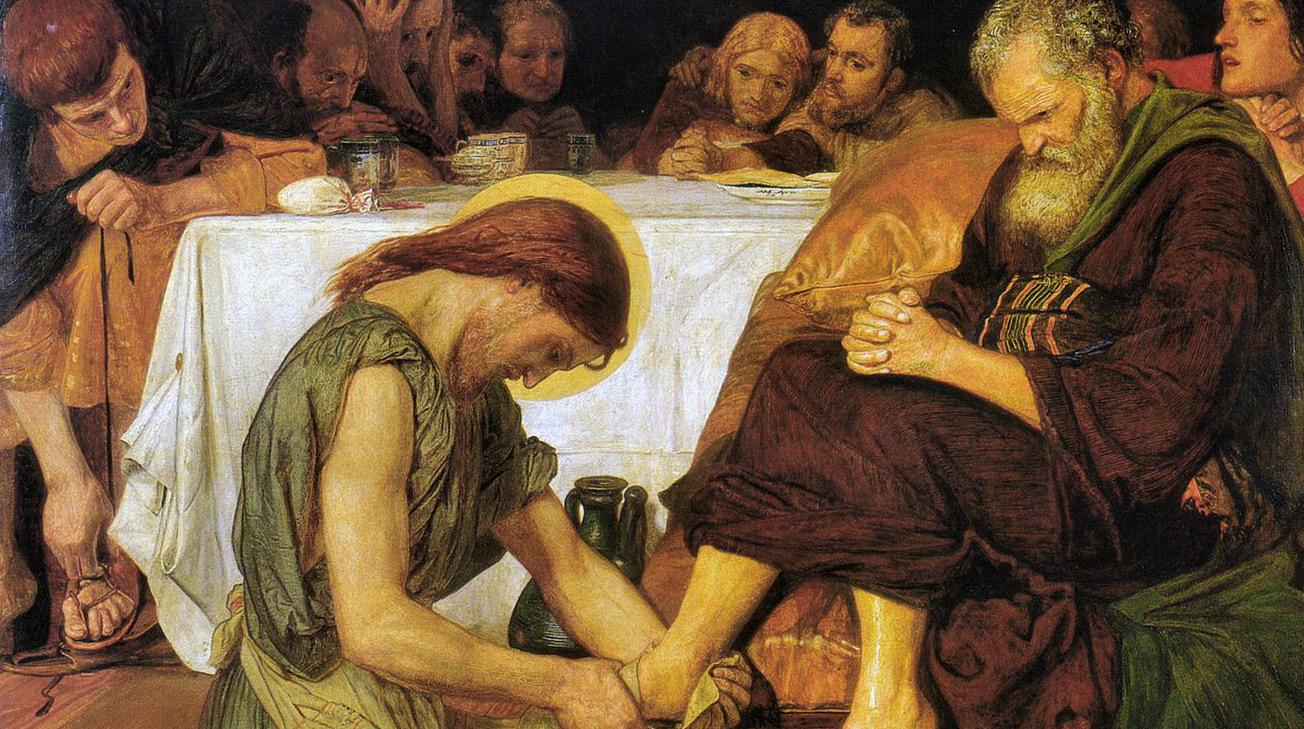

For modern Christian readers, therefore, Dominion is a charge to remember what has distinguished Christianity from the non-Christian religions of the Ancient World. There are great doctrines that must be defended — the Trinity, penal substitutionary atonement, and so on. But we must not forget that those doctrinal claims must be joined together with brotherly love. Christ himself said that the clearest demonstration to the watching world is abundant and self-sacrificial love toward fellow Christians (John 13:35). A striking reality demonstrated throughout Dominion is just how unexpected so much of the history of Christianity is. It is full of seemingly unexpected twists and turns over its two-thousandyear history. Consider just a few episodes. Few would

have expected a pious medieval monk (Martin Luther) to launch, inadvertently I might add, a revolution within the Western Church, sparking additional cataclysms of warfare and political unrest — or, a teacher of rhetoric to have a life-altering encounter with Romans 13:13-14, “Let us walk properly as in the daytime, not in orgies and drunkenness, not in sexual immorality and sensuality, not in quarreling and jealousy. But put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh, to gratify its desires” — let alone that he (Augustine) would go on to be a bishop and eventually become one of the most influential post-apostolic theologians. Or consider how a sixteen-year-old Briton (Patrick of Ireland) was captured and sold into slavery in Ireland, escaped back home to Britain, and then only six years later returned to Ireland as a missionary, leading to the conversion of countless Celts from the darkness of paganism and helping to shape Irish culture for a millennia-and-a-half.

Consider even Christ’s closest followers. They remained convinced throughout Christ’s earthly ministry that He was going to usher in a political kingdom, and they despised His own prophecies of His coming death. When He was arrested, they scattered. No one would have expected any kind of religious movement to last long

30

if it was substantially built on these twelve, let alone to have any measurable influence throughout the decades to come. Perhaps the most unexpected twist in the history of the Church is that the religion of the Crucified King, which esteems suffering and self-sacrifice eventually, reshaped the world. As heirs of this legacy, we have a duty to continue shaping the moral consciousness of our world through a faithful, prophetic witness.

Holland’s Dominion is a compelling narrative and a page-turner in the truest sense. But it is also the best kind of history: it not only tells the story of the past in a thought-provoking and careful way, but it also demonstrates how that past has led to the modern day. While Holland is no apologist for the church and, as of this essay, remains agnostic, he is clearly sympathetic to the claims of virtue and goodness that have marked out the Church. For us today, it ought to spur us on to love and good works.

1Larry Siedentop, Inventing the Individual: The Origins of Western Liberalism (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2014).

2Brian Tierney, The Idea of Natural Rights: Studies on Natural Rights, Natural Law, and Church Law, 1150–1625 (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 1997).

3John Witte Jr. The Reformation of Rights: Law, Religion and Human Rights in Early Modern Calvinism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

4Tom Holland, “Why I was Wrong about Christianity,” The New Statesmen, Sept. 14, 2016, https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/ religion/2016/09/tom-holland-why-i-was-wrong-about-christianity.

5Dan Carlin, Tom Holland, and Dominic Sandbrook, “Hollandansandbrook” Hardcore History: Addendum (July 27, 2022).

6Holland, Dominion, 308–309.

7Holland, Dominion, 540.

8Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007).

31

FAITH AND THE ACADEMY: ENGAGING THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH

AN INTERVIEW WITH ALISTER MCGRATH ABOUT PASTORAL APOLOGETICS

Jack Carson, the director of the Center for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement, recently sat down with Alister McGrath for an interview about ecclesial apologetics. What is the role of apologetics in the Church? How should pastors think about their role in the apologetic enterprise? These topics and more are explored in the interview below.

Alister McGrath initially studied natural science at Oxford, taking a doctorate in molecular biophysics under the supervision of Professor Sir George Radda. He later switched to studying theology. He was Oxford’s Professor of Historical Theology from 1999 to 2008. He then moved to King’s College London as Professor of Theology, Ministry, and Education before returning to Oxford as Idreos Professor in 2014. He also served as Gresham Professor of Divinity, a position established in 1597, from 2015-18. He retired in Sept. 2022.

Christian Apologetics: An Introduction

Christian Apologetics is a compact yet comprehensive introduction to the theological discipline devoted to the intellectual defense of the truth of the Christian religion. Assuming no previous knowledge of Christian apologetics, this student-friendly textbook clearly explains the major theoretical and practical aspects of the tradition while exploring its core themes, historical development, and current debates.

personally. And that’s a really important point because the great thing about a local church is that the pastor knows the congregation.

Carson: Hello, Dr. McGrath, thanks for joining us today. I am excited to talk a bit about apologetics and the local church. To kick us off, why does apologetics matter for churches? Why should pastors who are stressed and overwhelmed with their weekly routine care about apologetics?

McGrath: The local church is the primary site for good apologetics. What I mean by that is people come to church to worship, but they also come with questions. They come with their own questions — things they’re not quite sure about. Maybe they’ve come to faith with unresolved questions, or maybe they are bringing questions from their friends. They’re looking for answers from someone who knows them

Pastors know the levels of engagement and the ways of speaking that are going to connect with their audience. They can tailor a message that works for that local church. Sure, big national apologetics conferences are great, but they are no replacement for regular Sunday-bySunday engagement with questions that people are really asking. Pastors can regularly work apologetic themes into their sermons, and they can resource people without having to lecture them. Of course, you can also have local study days in your church if you want to. What I want to emphasize is that apologetics is both a science and an art, and the local church allows you to develop the art of apologetics. The pastor certainly provides information, but he also models the disposition of an apologist.

32

Guest

Interview

Alister McGrath

Carson: At least part of what I heard you saying is that the local church pastor is able to connect with the heart in a way that is incarnational. There seems to be something important about the pastor's role as a shepherd through seasons of doubt, not just as a lecturer.

McGrath: I think that's a very important point, and I think it’s well worth developing this because the kind of apologetics we’re really talking about in a local church is relational:

“I know these people and I want to help them and I can figure out how to do it because I’ve worked with them. I know the language they speak. I know the concerns they have. I want to be able to walk with them as they journey through these difficulties, and I want to try and give them ways of thinking which will really help them cope with their doubts.”

And it’s not as if I’m just saying:

“Hey, read this book and go away. Don’t bother me anymore.”

It’s rather about the incarnational move:

“Here’s what I found helpful. Here’s what I think can help you get through this season of doubt or difficulty. It has helped me.”

I really must emphasize this point. The individual church, the local church, your church, are critically important. It supplements what is going on elsewhere. Pastors have a vital role to play in the task of apologetics.

Carson: What are some of the pressing apologetic issues that pastors should pay attention to as they begin to reflect on what their congregation may ask them or may begin to experience as they go through life?

McGrath: Well, I think that’s a very good question, and let me just begin to tease out some of the things that we might think about here. I would suggest to pastors that they should reflect on the difficulties they’ve experienced and what they have found helpful in dealing with those personally. This is partly because those same tools may help a congregation, but this also allows the pastor to, in effect, say, “Look, I’ve been through these seasons of doubt as well. I was able to find hope and answers, and you can as well.”

I think it’s important for pastors to feel that they can own up to any difficulties they’ve had and explain how they’ve been able to deal with these. It makes them much

more human and much more approachable. But what are these questions people will be asking? Let me just mention two.