MY WORLD STORY BOOK

Asia / South Seas / Scandinavia

A Compilation of Historical Biographies for the Young Reader

Compiled by Marlene Peterson

Libraries of Hope

My World Story Book

Book One: Asia / South Seas / Scandinavia

Copyright © 2021 by Libraries of Hope, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. International rights and foreign translations available only through permission of the publisher.

Cover Image: The Norwegians Land in Iceland Year 872, by Oscar Wergeland (1877). In public domain, source Wikimedia Commons.

Libraries of Hope, Inc.

Appomattox, Virginia 24522

Website: www.librariesofhope.com

Email: librariesofhope@gmail.com

Printed in the United States of America

2950 B.C., Asia-China

He moulded an empire as a potter moulds a piece of clay. He was The Father of China, and her first emperor. Fo-hi achieved such wonders that old writers used to pause and ask themselves whether he was really a man or an epoch.

Was he Fo-hi, flesh and blood, son, brother, husband, father, or was he the name for an age? Was he a human being, like Alfred, or Caesar, or William the Conqueror or was he an era, like the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, the Iron Age, or the Renaissance? The answer now seems to point to the fact that Fo-hi was really a man, and that he did the marvellous things ascribed to him; the dates can be worked out with any approach to accuracy, he lived and reigned about 2950 years before Jesus, and established a civilisation from which the whole world must have borrowed.

We do not know how far ahead of us China was, but there is a record in Chinese history of the tenth century of the printing of nine classics from wooden blocks. If we find printed books being sold to the public in days when England was still a small, illiterate, Saxon kingdom, we may be sure China was already familiar with printed books long before those nine classics were ordered for the benefit of the public by the Chinese emperor.

When Rome was a wilderness the Chinese were a refined and learned people. Their science was old before the age of Greece; they were a civilised power before Egypt. It is not astonishing, therefore, to know that this wonderful country, long ago in ancient days, produced a phenomenal man centuries ahead of his time.

Fo-hi’s empire is the oldest on Earth; it was in existence nearly 5000 years ago. The great days of Egypt,

Babylonia, Assyria, Greece, and Rome came and departed; each empire rose and fell in turn, but China remained unchanging. No other nation is comparable with it; no other nation, in ancient days, was so safe by its position from being overrun and obliterated. When Fo-hi was born he found himself in the midst of a numerous people who seem to have been so many childish barbarians. Charles Lamb’s story of the Chinese man who burned down the house to roast the pig may have had a sort of historical precedent, for tradition asserts that the Chinese ate their food uncooked. They were free rovers, with no organised system of life. There was no marriage system; men knew their mothers but not their fathers; there was no settled agriculture, no skilled organised hunting for food. All was chaos and haphazard adventure.

Fo-hi had to make laws and establish institutions, to create a nation out of a jumble of multitudes. He established himself on the site of Kai-feng-fu, in the province of Ho-nan. He was as friendless as Mohammed, but he had a great power over his fellows. It is always one outstanding man who gets things done. The idea may not be all his own; he may share a general trend toward certain convictions; but it is the magic of a dominating mind that brings reforms to pass. Fo-hi must have been a master of ideas and methods, with patience and persuasiveness beyond comparison. He put himself, or was placed by discerning friends, at the head of those whom he could trust; he assumed authority over hosts; he became chief of many peoples composing his nation; and, proceeding from strength to strength, he became the first Emperor of China. He towered so far above the intellect of his contemporaries that they seem to have looked upon him as divine. Old Chinese history to this day makes it appear that he was of divine birth, a fact at which we need not wonder. If they believed Fo-hi as having something of divinity in him so much the better for Fo-hi, for rarely has there lived a man of grander mind. He instituted the law of marriage, a gigantic reform with illimitable consequences. It meant the setting up of permanent homes. It meant the defence and protection of the wife and children by the husband and father. But the

great nation was still a jumble of mingled peoples, too great in number to be easily controlled; so Fo-hi divided the people into groups, classes, and tribes, each responsible to its tribal head, and the tribal heads governing by general laws applying to all. He taught them cooking; he devised a system of hunting and fishing, so that the industrious and skilful should not starve.

He was, perhaps, the first metal-worker, and taught his people the use of iron, giving them weapons for the chase and for the defence of their land against invaders. He must have been something of a chemist, too, for he experimented with salt, and gave it to his people with their food and as a preserver of the food they stored. By that act alone he would ensure the development of his race, for population depends fundamentally upon the abundance and scarcity of food at all times of the year.

At the beginning of his reign the people must have lived like our rude forefathers, in caves and wattle huts. Fo-hi had ideas beyond that; he taught them to build permanent dwellings. Agriculture progressed under him, but Fo-hi had his limitations. He did not discover the plough; that was left for his successor, Chen-Noung. The mere fact that so great an invention escaped his mighty mind makes the list of his actual performances seem the more believable. He thought not only of the bodies but of the minds of his people. He loved music of the Chinese sort and gave his people musical instruments.

As if he had not done enough, Fo-hi turned his searching eyes to the stars, and worked out what was probably the first calendar. He gave his people a calendar by which they could mark the successive stages of the year. Naturally a mind capable of such a feat as that did not find it difficult to

divide the day and night into hours, and he gave the nation a sort of clock.

Now, all this was before the age of writing. Ideas could be conveyed only by word of mouth or by signs. Even Fo-hi’s colossal brain could not create a true system of writing in a single reign. But he made a good beginning. He invented a system of circular diagrams, still known as the Pa Koua. By means of this system he enabled the Chinese first to express words, if not abstract ideas not on paper, but on what served then in the place of paper.

Such was the work of Fo-hi, or some of it. How much of it was committed to writing by means of his diagrams it is impossible to say; possibly none. His deeds were recorded in men’s brains and hearts. They talked of his wonders. He became a sort of god in the memory of the Chinese people. From generation to generation his name and fame were in all men’s mouths. There was at first no literature, but his fame was preserved in the memories of men until writing came to enshrine it.

Fo-hi is said to have reigned 115 years. Length of days is always attributed to the ancients who lived before authentic history, and probably his reign was shorter. But, whatever its actual duration, it certainly comprised reforms such as no other reign ever produced. He had wonderfully fine material to work on, and the material is unchanged, like many Chinese customs, today. Remember the magnificent effort by which China has in our own time dashed aside the curse of opium. That was the spirit of the people Fo-hi guided and directed.

Even now his name is cherished with reverence in China, and his tomb is shown with pride at Chin-Choo. Well may China be proud of it, for, unless her history is false, it encloses the remains of the founder of the oldest civilisation still left in the world. Fo-hi brought China from barbarism to civilisation; he gave her a social and political system which outlived all the great empires that arose in its train. He was to China what Moses was to the children of Israel, what Alfred was to England.

Chapter 2 Eric the Red

950-1003 A.D., Scandinavia-Vikings

Eric of the ruddy hair was one of the greatest of the Vikings, a sort of colossal heroic Crusoe of the North who, exiled from humanity, steered his little ship out into the unknown ocean and possessed himself of what was virtually a continent, a cold Crusoe island, ten times as big as England. His father was a Norwegian earl and, like Eric, was a very pretty fellow with a battle-axe. His use of it in a heated argument with his neighbours left so many dead that he was banished to Iceland.

Eric had to leave his native land for a similar cause and, joining his father, was so embroiled with Icelandic Vikings as hot-blooded as himself that the parliament, after surveying the dead, bade him begone with his men for three years. He could not return to Norway, otherwise,

“The world was all before them where to choose Their place of rest, and Providence their rest.”

But there was no Providence for Eric, who, like all the Vikings, worshipped the old Norse gods. They believed that if a warrior died fighting he passed straight to Valhalla, the pagan heaven. So ardent were they for combat that when no enemy was handy they would take their fleets out and fight a private battle to the death among themselves in the fiords at home. There never had been such warriors, such sailors, such explorers as the Vikings.

The deadly feuds in which Eric and his father engaged were merely common form, true to Viking practice, and although they had to be officially censured we are not to regard these men as exceptionally blood-thirsty. When Eric had settled down as a prosperous and relatively peaceful ruler the saintly King Olaf sent his Bishop Thangbrand to convert Iceland and Greenland, which he did; but, true to Viking tradition and contrary to the mission of mercy he was preaching, he drew his sword in a quarrel and killed so many men that he, like Eric, was expelled from Iceland.

It was in 982 that Eric’s battles led to his banishment. He was 32 and married to Tjodhild, whose mother bore a poetic name meaning Ship’s Breast. Eric was one of the fiercest of his warlike race, hard as iron, with a born leader’s command over men. He had killed so many in his last quarrels that his followers had to conceal him while his little ship was being made ready for sea. Then, with a small company of free men and thralls, he launched away to seek over the ocean he knew not what.

He did realise that far to the west there lay land of some sort, for a Norwegian, blown out of his course, had seen little islands and a mysterious coast whose snowy surface made him call it White Shirt. Half the world was to name in those days. Eric steered south and west; the duration of his voyage is not recorded. But he must have sailed over two thousand miles in a little vessel, open like a rowing boat, with sails and the sweeps plied by the arms of his men.

How he lived and found his way remains a mystery. There was no compass to steer by, no map; there could be little provision for water; there was no fresh food, no fruit or vegetables, no wheat, nothing that we regard as essential for the prevention of that scourge of long voyages, scurvy. Salted

meat, tempered by fish caught on the way, could have been the only fare. But the steering in unknown ocean ways?

Nansen, that noble Viking of our own day, himself the greatest modern master of unaided contrivance in the Arctic, tried to put himself in Eric’s place and work out his methods by close study of sagas and old legends and records. Eric never saw a clock or other time-recording instrument, unless by some chance he had robbed a monastery of its hourglass. Therefore he had to rely for safety on his own sense of time, which would be far keener than ours.

He watched the Sun and stars for guidance. He could get a day reckoning by a Viking device. When the Sun was in the south he could make a man lie down amidships and observe where the shadow of the gunwale fell on him. That would give an idea of the Sun’s altitude and afford some notion of latitude.

How keen was this time sense in the Vikings was shown in Eric’s son Leif who, when he reached American waters, was able to say that the Sun rose there at 7:30 and set at 4:30 on the shortest day of the year. From that the scientist can work out his latitude to a nicety. Eric carried birds to throw out so that he might watch their flight toward land; he would note the drift of ice and wood, and the character of free flying birds would hint to him their place of origin.

The end of his voyage brought him to his new home, the vast island continent of which the rest of the world knew nothing. He sailed from the east to the southwest, but he did not touch the eastern coast, either because he did not see it or because its rocky, barren face deterred him. He turned the southern point and sailed north, and he landed at what is now called Julianehaab, a

record voyage for the age.

Greenland has an internal ice-cap of 700,000 square miles, one incredibly vast glacier, in places 8000 feet thick; but there is a green verge along the coast, especially on the west, where the Viking had cast anchor. It seemed a goodly land to his stout heart and he determined to make it his kingdom. He explored and found traces of ancient habitations, the huts of a long-vanished people.

He determined to return to Iceland at the end of his banishment and get together a company of Vikings to share his newfound kingdom.

“But what will you call the land?” asked one of his comrades, as he ruefully surveyed the ice and barren wastes. “Call it Greenland,” instantly answered Eric. “But it is not everywhere or always green,” said his friend. “It matters not,” laughed the leader of Vikings; “Give it a good name and people will come to it.” And he was right, for when at the appointed time he ventured back to Iceland he had no difficulty in inducing such numbers to venture under his leadership that 25 shiploads of men and women, with livestock and stores, sailed with him in 986 to found Red Eric’s kingdom of Greenland.

He built his house at Brattelid, which means the steep side of a rock, near the inner end of the fiord of Tunugdliarfik, just north of Julianehaab. Seven and a half centuries later a Norwegian missionary named Hans Egede found and lived in the ruins of Eric’s house. It was built with the solid rock for one side, the remainder being made up of walls containing blocks of sandstone four to six feet thick, long and broad, immense slabs that reminded the visitor of Stonehenge, and made him wonder how the Vikings had got them into position.

Only 14 of the 25 ships that sailed with Eric arrived; some were driven back, some were lost at sea; one arrived after having been four years on the way, with long stops on barren islands as part of the famishing odyssey. Eric established two colonies, one about his own home, the other some hundreds of miles farther north, as if afraid to have too many Vikings to the hundred miles. He ruled with justice and wisdom, or the colony could not have survived.

In that most desolate of all the homes of Earth a literature grew up, noble literature that takes its place with the magnificent writings produced in Iceland, the first little land to have a literature of its own in modern Europe. But it is not so much from the literature that we know how Eric lived as from his rubbish-dump, his kitchen midden. There we find the remnants of what he fed his family and friends on.

There are bones and horns of very small cattle, of goats and sheep, bones of seals, of a polar bear, of some reindeer. There are no bones of fish, a fact that is eloquent to the expert. We know that Eric had no winter fodder for his horses and cattle, so he fed them on the heads, offal, and bones of fish, precisely as his descendants feed their fine ponies in Iceland today.

Grain was the precious rarity. That could come only by ship; the food staple was the flesh of animals, fish, and birds, eked out by milk. There is a picture of Eric, recorded in a saga, sorrowful almost to tears in his old age because he has no grain with which to make the yule-brew; for to give a feast at Christmas in which the Yule-brew was included sufficed in those tenth-century days to establish a man’s fame for years after.

In this case the warrior was not disappointed, for men who had come by ship and whom he desired to entertain answered, “We have malt and meal and corn in the ships, and thereof thou shalt have all thou desirest, and make such a feast as thy generosity demands.” And he made them

such a feast that its magnificence had never been equalled. But graver cares descended upon the great warrior.

He had two magnificent sons, Leif and Thorstein. Leif, hearing that a Viking making for Iceland had been blown to some unknown land in the West, set out to rediscover by design what had come to knowledge by accident. That was the famous voyage of 1000 that bought to the knowledge of Europe the existence of America nearly five centuries before Columbus set sail. Leif was afterwards called Leif the Lucky, not because he had discovered a continent; Vikings took discovery and possession of new lands as part of their natural vocation. Leif was Lucky because he had discovered and brought back a shipwrecked crew with him in safety.

That affords an unwonted aspect of character in these dreaded warriors, in respect of whom our ancestors used to pray in our churches, “From the fury of the Northmen, good Lord deliver us.” They deemed themselves fortunate in an opportunity for a chivalrous act to the unhappy and helpless.

Eric welcomed a weary, worn Leif in the autumn, and, as in the chapter from Homer, the son led his beneficiaries to his sire.

“It would be a worthy deed,” he said, “to take charge of the men who are homeless and to provide them with lodging.” Eric answered briefly. “Thy words shall be followed,” and he housed them and gave them land. But Leif put his formidable father to a sterner test when, returning from

Iceland, he brought Bishop Thangbrand with him to convert Eric’s wife immediately to Christianity. Tjodhild, the first Christian in Greenland, built her own church, and, as the impenitent Eric still worshipped Thor and Odin, she separated from him and dwelled apart.

Eric growled that Leif was lucky in having rescued the shipwrecked crew, but one thing balanced another, for he had also brought “the hypocrite” (Thangbrand) to Greenland. The great leader’s sailing days were over. He had colonized with superb valour a land the very sight of which caused John Davis later to name it Desolation on the map.

Eric explored far up in the Arctic, and was in Disko Bay five hundred years before Davis imagined that he had first discovered it. His second son having died, Eric married the widow to Karlsefni Thorfinn, who in 1002 sailed with three ships, with 160 men and women, with cattle, horses, and stores, to Leif’s newly-found America, and dwelled there for three years.

Eric’s daughter as well as his daughter-in-law was of the company, and Eric became the grandfather of the first white child, a girl, born in the New World.

We do not know the year of his death, but take leave of him in the prime of life and the pride of a great Viking who had done an unprecedented thing in founding a colony in a new land just beneath the Arctic Circle. His settlement lasted nearly three and a half centuries.

Then the Black Death appeared and prevented corn ships sailing from Norway.

Eskimos killed off the famished, enfeebled white Greenlanders, and the world forgot for a century and a half that there had been such a man as Eric the Red and that there was such a place as Greenland. The land had to be discovered again, and only a rereading of the imperishable literature of Iceland literature that is supposed to have given Columbus his idea of an Eastern world in the West redeemed the shining memory of this great warrior empire-builder from lasting oblivion.

Eric was indeed the Crusoe of the North, but he had to find and furnish his own island, and that island is the largest in the world with the sole exception of Australia.

Chapter 3 James Hall

Died 1612 A.D., Scandinavia

A crusader in one of the most romantic causes that ever drew a man North, he went, not for trade or for the golden furrow to Cathay, but in quest of a lost civilisation.

The King of Denmark decided that if possible he would find the descendants of Eric the Red, the Viking who had colonised Greenland six centuries before, and he bade Hall lead the searching ships to the lost haven in the ice. There had been no communication between the colony and its motherland for nearly two centuries when Hall first set sail in 1605.

For four hundred years Eric’s descendants had kept in touch with Norway. They had horses, cattle, sheep, and goats; they fished, and hunted seals and whales; but they relied entirely for corn

and salt, so indispensable to Europeans, on the ships that sailed to Greenland from Norway and took back in exchange hides, wool, and other Greenland products that helped to furnish the Crusades.

But supply ships were often wrecked; Norway was incorporated for a time in Denmark and Sweden, who did not care about Greenland, and once the port from which the ships for Greenland sailed was wrecked, and more and more the descendants of Eric were neglected and deserted.

Finally plague swept over Europe, slaying everywhere, and killing the crews who should have sailed in the supply ships. The last vessel that reached Norway from Greenland dropped anchor in Bergen in 1410, and it brought a story of tragedy that might have come from Shakespeare, of two unhappy Greenland lovers, one of whom was burned at the stake, while the other died of grief. That was the very last message to Europe from the colony of Eric the Viking.

Hall piloted his ships to the lost colony, knowing that although Davis had sailed up the coast and found the Strait that bears his name 19 years before, all was silent as to Eric’s home. Indeed the last word had been that of the Pope in 1492, who had written appointing a monk, who was never to sail, bishop of the land that “lies at the world’s end,” pointing out that for over eighty years before that date no ship had called there and that the Greenland Christians had had neither bread nor oil.

With skill and courage Hall picked his way through the ice to the lost haven; again the next year, and the year after that. All was melancholy solitude and death, as though the plague had visited Viking Greenland as well as Europe. A generation gave itself to the loss of the Franklin Expedition, but more than three hundred years were necessary to write the story of Christian Greenland that Hall was seeking.

One of the rare seamen who could write, Hall published an admirable volume of his first two voyages, giving the world its first coherent account of the Eskimos as they actually lived. He pictured them making their winter homes with frames of the bones of whales, roofed with turf and soil to keep out the frost and snow; he showed how they disguised themselves in sealskins in order that they might approach and kill seals for food, fuel, and clothing.

What happened on the third voyage is not clear. Either Eskimos were captured to be taken back to Denmark, or in a fight some of them were slain. There is nothing to suggest that Hall was in any way responsible, but he was to pay the penalty later.

In 1612 he organised an expedition of his own. Like Sir Martin Frobisher, he was convinced that he could find gold in the Arctic, and, in spite of the great admiral’s failure, ample support was forthcoming for the scheme. He now had the great Baffin as the pilot of his second ship, and it is from him that we know what happened.

Hall reached Greenland for the fourth time, and there he was encountered by angry Eskimos, who remembered what had befallen their fellows during the previous visit of the white men. As Frobisher and later voyagers found, Eskimos never forget: history is passed on by word of mouth from generation to generation. A native hurled his spear and wounded the English leader.

The doomed man was brave and clear-headed to the last. In all his four voyages he had had with him a Scarborough boy named William Huntriss, and, now that Hall was about to die, he ordered that while the master of the second ship should succeed himself as captain, Huntriss should in turn be promoted to the captaincy of the second ship. Hall died while his ship was at sea, but was buried by his own request on the great island whose pathetic mystery he had been seven years

seeking to penetrate.

The problem that baffled him was pieced together little by little, and not finally solved until 1926. Then Dr. Norlund of Copenhagen, revisiting the old settlement, found thousands of Viking farmsteads, the ruins of a cathedral, with a bishop’s palace and outbuildings covering four acres; stables for hundreds of horses, byres for cows, the old stone pens in which sheep were folded, smithies, pigsties, and the graves of those who had been left to slow starvation and death.

One of the graves contained the skeleton of a bishop, with his pastoral staff and crozier of walrus ivory, with his gold episcopal ring on his finger, but with a foot missing, as though he had lost it during life from frost-bite or other accident. Everything pointed to the former existence of a high civilisation and a numerous population, but all had perished a century or two before James Hall gave his life in the effort to make the sad story known.

Chapter 4

Thomas S tephens

1549-1619 A.D., Asia-India

The race was not to the swift nor the battle to the strong; Thomas Stephens, the quiet, brave scholar, won the race to India, the first Englishman there. We hardly know of him at home, but more than 300 years after his death his name shines bright in Portuguese India, where they still chant the poems written by the foreigner they called Thomaz Estevao.

Stephens was born about the middle of the sixteenth century, and was educated at Winchester and Oxford. Afterwards he went to Rome and became a Jesuit.

Columbus in seeking India had found the West Indies and South America; Cabot had found North America; Willoughby had perished with all his crew; Chancellor had found the White Sea and Archangel, and the way on foot to Moscow all of them seeking India, with its spices and gold. Stephens sought it only for the salvation of souls. England could not reach this promised land by

sea, although the King of Ternate in the Moluccas had contracted with Drake to supply England with all the cloves we needed.

There was nobody to follow up that most romantic of treaties, nobody to take the determined scholar to India under the flag of England, so he enlisted under the flag of Portugal. He sailed from Lisbon in 1579, and, by way of the Cape of Good Hope, reached India the same year, to become rector of the Jesuit college in Goa.

Stephen wrote home to his father a series of letters glowingly describing the fertility of the land, the wonders of the scene, and the openings for peaceful commerce. There were no newspapers then, but news travelled as it had always travelled before printing was known, and soon commercial England was on fire with ambition to share the trade described by this pioneer

The first trading mission from England went out in 1583, and Stephens had to intervene to save the lives and liberty of its four members from the jealous Portuguese.

Stephens had his hands full, however, in other directions. The frightful Inquisition was busy in Goa, burning not only men and women but their temples and their writings. The native literature perished in the fires lit by Christians. Stephens devoted himself to the creation of a new literature for the stricken people.

He was the first Christian to write a line for publication in India. He wrote a grammar for the natives, and then, when that had sunk in, he applied its principles in a translation of the New Testament. It left his hands as a great poem, and the people came to know and love the Christian faith through his poetry. It has been often reprinted, and is still beloved of native Christians in Portuguese India. That was the foundation of Christian literature in India.

Forty years he lived in India, and there he died. He was revered as a saint. He feared no danger, but braved peril, disease, and discomfort in a strange land, first of his nation to do so, to bring glad tidings to a people for whom his heart yearned.

Chapter 5

Gustavus Adolphus

1594-1632 A.D., Scandinavia-Sweden

He was born in Stockholm at a time when terrible events between Roman Catholics and Protestants were brewing in Europe. His father Charles the Ninth was able and conscientious, and in spite of the perils amid which he moved he educated his son with thoroughness and wisdom. Gustavus was a bright, handsome boy of splendid brain and spirit. He was a Viking cradled in a Christian home, and the latent energies of his wonderful race blazed volcanic within him.

Whatever he did he did with all his might. He had a gift for languages and wrote and spoke five with fluency. He revelled in mathematics and made himself master of all the science that was then known to civilization. His body as well as his mind was developed and he grew into a magnificent specimen of manhood, tall, broad, and muscular, with gigantic strength. Withal he had the true spirit of a crusader.

His father died when Gustavus was only 17, and the boy sovereign inherited a perilous throne. He had three wars on his hands, but he was afraid of none of them. The youngest man of the Council was Count Axel Oxenstierna, who was eleven years his senior. Gustavus recognized in him a man of noble spirit and chose him as his Prime Minister. Never was a more perfect combination than Gustavus and Oxenstierna. They were like brothers.

Gustavus had the Viking valour, reinforced by brilliant mental gifts and scholarship; Oxenstierna was just as courageous, but he had the cool wisdom of a statesman. Delightful letters passed between the two while Gustavus was away fighting and his

brilliant minister was directing the helm of state at home.

“You are so cold in your proceedings that you act perpetually as a drag on my activity,” the king laughingly grumbled in one of his letters, to which his trusty minister replied, “If I did not perpetually throw cold water on you, you would catch fire and blaze up once for all.”

The early years of Gustavus as king were occupied with his inherited wars. He compelled the Danes to make peace; he was as successful with Russia, who had to cede him Riga and a great part of Latvia. He withstood all the efforts of the Poles and at last had peace within his borders. The importance of his triumphs to history is that he defeated the Roman Catholic plan to capture the Baltic, with the North Sea, and with it their trade, and so to reduce England and Protestant Holland to submission.

Sweden was a little country, but Gustavus made her the most formidable military force in Europe. He was about to be drawn into conflict with the whole forces of Spain, Austria, and Roman Catholic Germany, against the most ruthless and lawless armies ever engaged in the wars of religion,

with two merciless geniuses, Count Tilly and Albrecht von Wallenstein at their head. They had in their ranks butchers and brigands who burned, pillaged, and martyrized wherever they went.

Destitution and horror remained behind them. Such was the suffering of the famine-stricken victims that they were driven to cannibalism. Gustavus prepared for the mighty conflict he knew must come.

He raised funds, perfected his army, and revolutionized the art of warfare. Until his time men had gone into battle heavy with armour, with set, inflexible tactics, accustomed to fight during summer and, like Caesar’s armies, to retire to secluded quarters for the winter. Gustavus abolished armour and winter rests, and completely altered tactics. He trained his infantry to perform intricate evolutions under fire, he trained his cavalry to charge in masses and to manoeuvre with the easy precision of professional trick-riders.

Above all he inspired his men with zeal for their cause and taught them to realise that they were fighting not only for their hearths but for freedom to live unfettered, to trade unrestricted, and to worship as conscience dictated. It was in 1630 that the Swedish hero, acceding to the moving appeals of the dying Protestants, crossed into Germany.

His army was only 15,000 strong, and there may have been only 8000 Swedes in it, with the remainder English and Scots. The Duke of Hamilton alone took six regiments to fight for the sacred cause; and if we are to believe Scott, the immortal Major Dugald Dalgetty, who strides such a glorious figure of learned martial fun through The Legend of Montrose, was no inconsiderable fighter in that marvellous army.

Never did a leader embark on a more perilous enterprise than that of Gustavus. The ferocious

Tilly and Wallenstein, by wholesale massacre of Protestant men, women, and children had so terrorized the land that Protestant princes were cowed and afraid to raise their heads. They had summoned Gustavus and they left the fighting to him. The Roman Catholics jeered as the little army sailed into Pomerania. “The Snow King will soon melt in the South,” they said.

But the Snow King and his army in sheepskins did not melt. He roused the fallen cowards into action and made them march with him. Everywhere his genius made him victorious. His tactics bewildered the far greater forces of his enemies. Europe marvelled at his skill and bravery, and men from all nations flocked to his camp as to a military university to learn the arts of war as those arts were practiced under his skilled direction.

Eighty fortified towns fell before him in eight months. He fought continuously; there were no winter quarters for him. He won battle after battle; he never knew a reverse. In September 1931 he met the dreaded Tilly at Breitenfeld and inflicted on that fanatical zealot his first great defeat, and by so doing liberated all North Germany.

Following Tilly up to the Rhine, he took Mainz in December. Then, forcing the passage of the Lech in April, Gustavus pursued Tilly into Bavaris, and at Ingolstadt Tilly died of his wounds. Anyone of that age but Gustavus would have thrust on to Vienna to secure a spectacular triumph, but he was a statesman as well as a warrior, and knew that an enemy army in the field and not a gay capital was the true objective of a great general.

The Emperor had recalled the terrible Wallenstein, with unlimited power, to the head of the

Roman Catholic forces. He, Tilly, and Gustavus are the three great military figures of the age, and the Swedish Lion had now to face his mightiest antagonist. He scorned an easy conquest of Austria, which would have made him lord of Europe for a moment, but with Wallenstein preparing new horrors on a still greater scale.

The mere raising of his flag brought fresh hordes of bloodthirsty mercenaries to the side of Wallenstein. Gustavus turned in pursuit of him. His enemy cunningly entrenched at Nuremberg, and not all the valour and genius of Gustavus could overcome him; but he was driven north, and the day of days dawned on the field of Lutzen on November 16, 1632.

A heavy fog enveloped the scene, but as it lifted Gustavus drew up his army and said prayers before them. With bands playing they all sang a great hymn of Luther’s. Then, mounting his horse, the king cried, “God with us!” and the terrible battle began.

It was one of the fiercest struggles in history, and even now its details are imperfectly known, for fog descended during the climax. The tactics of the Lion were brilliantly successful at the outset

GUSTAVUS ADOLPHUS

and Wallenstein was in danger of rout. He rallied his troops and advanced successfully on the Swedish centre. When a break in the fog permitted him to see what was happening Gustavus led a superb charge of cavalry.

The old Viking crusader spirit blazed up in the king and he outdistanced his men in their victorious advance. He was surrounded by enemies and shot and stabbed to death. When his army heard of the tragedy they bitterly avenged him, and his last fight, although its cost shook the Protestant world with grief and dismay, was a culminating triumph worthy of his fame.

His body was found after the battle, terribly wounded and scarred. His buff jerkin of elkhide was sent to Vienna, and remained there for three hundred years, when, as an acknowledgment of Swedish help to starving Austria, it was forwarded as a gift to Stockholm, to join the collection of relics in the National Museum: the three shirts that he wore, riddled with bullets and swordthrusts, his hose, lace collar and cuffs, pistols, and the rough-haired Swedish charger that he rode, stuffed, and still wearing the embroidered saddle from which he fell on the field of Lutzen.

The Thirty Years War had 16 years to run after his death, but he left an example and an inspiration that heartened the Protestant world; and he lives in history as one of the noblest of Christian knights, insensible to fear, chivalrous, as merciful to the conquered as his enemies were merciless, disinterested and unselfish, a lofty soul armed with the sword of righteousness, one who proved himself to be an unswerving friend and a true lover of his fellowmen.

Carl Linnaeus

1707-1778 A.D., Scandinavia-Sweden

All the world would love a universal language. Linnaeus supplied it for Nature’s own kingdom, for animals and plants. He lives himself in one of the names he gave, that of the Linnaea borealis, a little wild evergreen common to Northern Europe, Asia, and America, and he gave his name to this “little northern plant, long overlooked, depressed, abject, and flowering early,” because it seemed to match the details of his own career. For he, too, was a little northern plant, depressed and abject, flowering early.

He was born at Rashult in Sweden, son of a poor village pastor. The parson’s real name was Ingmarsson Bengtsson, but on going to the university he took the Latinized name of a famous lime tree, and his son Carl was named Linnaeus after him, until ennobled for his work. He took the shorter form of Linné. As Carl Linnaeus, he became a botanist almost as soon as he could walk and talk, for his father had a garden and Carl had an uncle who was a naturalist, and many a wild flower did the boy bring in from the fields and heaths to upset the order of his father’s border.

The parson wished Carl to follow him in the Church, but Carl objected, so his father bound him apprentice to a shoemaker, and few flowers blossomed about a cobbler’s last. Fortunately, Carl’s schoolmaster knew there was something in the lad, and lent him a treatise on botany, took him into his own family, and then enabled him to go to the University of Lund. Carl’s father could allow him only eight pounds a year, and the young student suffered great privation, being so poor that he had

to mend his own shoes with paper and the bark of trees.

His genius attracted the attention of a physician who had a good library and shared Carl’s taste for natural history. Studying his patron’s books and Nature in the open Carl made rapid progress, and won a royal scholarship that took him to Upsala University, where the professor of divinity set him to work describing the plants named in the Bible. His new patron enabled him to take pupils, and so the specter of poverty vanished from the earnest student’s life.

All the men of learning with whom Linnaeus came in contact were impressed by his talents and courage, and when he was only 24 he was appointed to travel in Lapland to observe the natural history and customs of its people. During the summer and autumn Linnaeus made a magnificent expedition, covering more than 3800 miles, nearly all the way on foot, often alone, never richer in escort than a couple of Laplanders to guide and translate for him.

Observing with the instructed ardour of a specialist he underwent terrible privations and was often on the verge of starvation, often so footsore and weary that he could barely crawl at night to his hut or hovel to crave a lodging and a meal. The Lapps marveled at the sight of a man who came out of nowhere, carrying a sword and a gun to protect his life, and a notched staff to measure anything whose size he wished to know; with a little bag that carried too few clothes, but included inkpot and pen, microscope and telescope, a diary, and a mass of paper for drying the plants he collected.

“O wretched man!” cried a woman at whose house he asked for shelter, “what hard fate can have brought you here, to a place never visited by anyone before? Miserable creature, how did you

come, and whither will you go?” Well might she ask, for his clothes were muddy and sodden from miles of struggling through marshes, and he was almost dying from exhaustion. All she could give him was a piece of salted reindeer flesh. He ate it ravenously, but was so weak of digestion that it nearly killed him.

At another place all that his hostess could give him was fish over which maggots crawled. Later he was caught in a forest fire with boughs of burned trees suddenly crashing upon him as he made his way. Once a tree fell between him and his guide, a yard from each of them; both men were unhurt. Not until after his death did the world read the story of the great journey that the poor scholar had made, the trials he had endured, and the deadly perils he had succeeded in surmounting. Other travels led him to Holland, where he took his doctor’s degree, and, meeting the immortal Boerhaave, was helped by him to a post that fate seemed all along to have been reserved for him when he was qualified to fill it. He was appointed to the control of the botanical gardens and collections of a scholarly banker, and here Linnaeus began the first of a series of publications that made him lastingly famous and rendered us all his debtors. Not only did he describe and classify his patron’s botanical possessions, he began the great task of reducing the world of plants and animals to a system of rational names and orders.

Plants and animals had names already, of course, but there was no real order, no enlightened attempt at a system, no grouping of like with like, of collecting species into genera, and genera into the larger, fundamental groups. The system of names employed seems incredible today. Suppose Juliet’s rose had been the dog-rose; its scientific description, translated from Latin into English would have been “the common rose of the woods, with a flesh-colored flower.” All flowers and all animals had titles as clumsy, each isolated from its related kind.

Linnaeus was poor at modern languages, but a master of Latin, and wrote all his works in that tongue. The names that he gave were naturally Latin; he was at home in that language. Moreover, Latin, having been for two thousand years the international language of learning, a name in that language would be understood all over the world where Latin scholarship prevailed. We see that advantage of the system at once when we realize that our names for, let us say, the Lesser Celandine and the Wych Elm mean nothing to a foreigner whereas if we speak of them as Ranuculu sficaria and Ulmus montana all the world knows what we mean.

We still retain our lovely old names for use among ourselves, but different titles are bestowed on flowers and birds and animals in different parts of our own land, so even we need the scientific names as well if we are to identify the species actually meant. America speaks of her robin when she has not got a robin, but we know what she means when we read the scientific name of the bird she wrongly names.

But we needed a system in giving these universal names, and Linnaeus was the man who invented a system. He reduced the names of the genus and the species to two words each, and with masterly powers of summary he contrived to get the character of the animal or growth indicated in each. For example, the generic name of our great cat family is Felis, the Latin name for cat. All the

cats are grouped under this title with a subordinate word to indicate their character, as Felis leo for lion and Felis tigris for tiger. Under this system we know that America’s so-called mountain lion is not a lion; it is the puma, know to science as Felis concolor, while the American jaguar is Felis onca. Those are the names for these animals all the world can understand.

The making of the system for all known plants and all known forms of animal life was one of the greatest tasks ever undertaken by a laborious mind. And Linnaeus was its author. He reduced Babel to order. Dividing the animal world into six sub-kingdoms, he grouped them as mammals, birds, amphibia (with which he wrongly associated reptiles), fishes, insects, and worms. For every genus and every species he found a name and three fourths of the names he gave remain in use today. The vegetable kingdom he classified by resemblances between one plant and another, in the main by pistils and stamens. And again he named everything, and it remains for our use to this day.

At 31 he settled in Stockholm as a physician. There, in addition to a large practice, he carried on his shoulders, with single assistant, the whole burden of teaching medicine and surgery at the university, while he acted as tutor to students for all parts of Europe. He no longer had to mend boots for a living, for he grew famous and even rich.

Chapter 7 Captain Cook

1729-1779 A.D., South Seas

A half-starved Yorkshire labourer came home one day and found that another child had been born in his two-roomed cottage at Marton in Cleveland. He had nine children in all, and we may imagine that he thought very little of one more. But all the world thinks well of this one now, for his name was James Cook.

This little country, its future greatness all unknown, made little preparation for immortal men. This child who was to find a continent and win it for the British flag had hardly room to be born in. There was no education waiting for him; he must pick up such scraps of knowledge as he could. But there was a good lady who taught him to read, and his father’s master liked him and thought this bright, poor boy worth helping, so he gave James a little schooling, enough to make him a smart shopkeeper’s apprentice in the little fishing village of Staithes, near Whitby.

Then James Cook ran away to sea and became a sailor.

We think of Cook as the explorer of Australia and the founder of British influence in the Southern Dominion, but how often do we remember that he who gave the British Empire a mighty continent played no mean part in giving it also the greatest piece of the American continent that any single Government holds? Cook not only made Australia known, he also helped to conquer Canada. The ship he was in went to Canada on the war with France, and they found him a rare

sort of man. He was a very clever surveyor, he knew all about tides and currents, and he could find shoals and hidden rocks so well that the admiral came to depend on him. Cook would go out at night alone in a little boat, making notes of the unexplored banks of the St. Lawrence River and the shores of Newfoundland. Once the Red Indians caught him in the St. Lawrence and carried off his boat, but Cook leaped on to an island with his precious notes and charts; and he must have been delighted when he was given £50 for them. They proved to be very helpful in the conquest of Quebec. He went on and on; he mastered Euclid and taught himself astronomy, and he took notes of an eclipse which pleased the Royal Society so much that when Venus was to cross the face of the Sun, and the Government wanted to send an expedition, it was this scientific sailor Cook who was chosen to go out with Sir Joseph Banks, who equipped the vessel, the Endeavour, at his own expense. He sailed to Tahiti, saw the eclipse, and then for three years he explored the Pacific.

It was an unknown ocean. Spain and Portugal and Holland had known it; their imperial fleets had scoured it and exploited it; but they kept the precious knowledge of it to themselves, and since the days of Drake it had been a mysterious sea. Nobody knew of the land that lay beyond it; nobody knew anything about the Australian continent except a few travellers with doubtful tales, and perhaps a few astronomers who are said to have seen the shadow of the continent on the Moon. Cook sailed on and on, with a friend on board in Sir Joseph Banks, one of the best botanists who

ever strolled through a country lane, and one of the best English patriots who ever gave his services to our race. Many strange sights they saw. They found the sea lit up at nights as if on fire, and Cook thought the light must come from luminous fishes, as, of course, it did. They sailed along the coast of Brazil, where some of their party were nearly frozen to death while seeking plants on a mountain on a summer’s day.

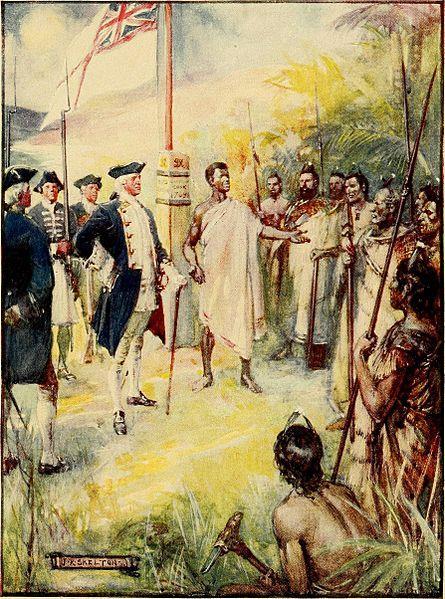

They found and named New Zealand; they sailed right round both islands, astonishing the Maoris, who had been there five hundred years or more, but were cannibals still, and would have eaten Captain Cook and all his crew could they have caught them. In spite of them Captain Cook surveyed New Zealand and took possession of it. In the name of England he set up on a hill two poles carved with the name of the ship and date, and he called together an old chief and his tribe, gave them presents and treated them well, and made them swear never to pull down the flag that he left flying there.

It is a dramatic little scene, this picture of our great sailor appointing a Maori chief as trustee for the British flag, and all the more strange when we think that England did not bother much about the flag for two generations or more. One wonders if they found it flying then!

On to Australia went Captain Cook, to that glorious harbour of Sydney. For ages the long, rolling waves of the Pacific Ocean had swept the lonely continent, the greatest island in the world, but no visitor from the outer world had come to this far place. No white man that we know had been near these ancient haunts of the wild, strange life; not one page of the history of Australia was ready to be written, for the great civilized world knew nothing of it. It was as if the southern world had been asleep.

And yet there was to take place, following on this visit of Captain Cook, a race for Australia, in which England reached the winning-post only just in

time. Australia, it is true, had been touched at various points by mariners, but they brought back tales of hopeless barrenness, and it was not till Captain Cook sailed to its eastern coast that a white man realized that here was a mighty continent. He was the first man to see the potential wealth of Australia; he was the first to sail the coast, and land, talk with its people, and understand something about them.

He did it all at the peril of his life, and he nearly brought disaster to his crew, for one day in these uncharted waters his ship ran on a hidden rock about 25 miles from land. It stuck fast on the rock, poised on it for two days and nights, and it seemed as if nothing but a miracle could save them in that wild place, on that mysterious coast, with civilization ten thousand miles away and no human help at hand. And a miracle did save them, for at last the ship was lifted off the rock, and what everybody on board expected to happen did not happen. As the water had been coming in it was thought that the ship would sink, but it was saved by the very thing that had seemed to threaten it. A piece of the rock that had pierced its hull snapped off its base and remained in the hole it had made, plugging it tight and saving the ship till it reached home.

But it was not a rare event like that which made this voyage memorable; the great achievement of Captain Cook was that he secured Australia for our race. Yet years were to pass before we took the slightest interest in this vast continent he made known, and Cook had been years in his unknown grave when another British captain followed him and set up the British flag in Australia in the very nick of time to save it from France and Napoleon. A few days after this captain had arrived at Sydney, and as his ships were ready to sail out of the harbour, there sailed in another ship, with La Perouse on board, to take possession of Australia for France. England had found a continent, and France had lost it, by a few brief but precious hours.

A great, brave soul was La Perouse. What emotions must have stirred within him in that fateful hour! He had come to win an empire for his country; he was sailing to his immortality; he was at the gate of his promised land; and it was not for him to win. But he could enter. Captain Phillips and his men gave the great Frenchman a fine reception, and the disappointed explorer was happy among friends. He stayed with them a few weeks and then set out again, but before he left he wrote to the French Government explaining what had happened. Then he left his papers with the English captain, said good-bye, and sailed away with his two ships.

It is one of the tragedies of the world that La Perouse was never seen again. In that dramatic hour he disappeared from history; he must have gone down at sea with all his men.

Captain Cook came home, and not a man in England knew what a glory he had added to the British Empire. There were no triumphal days for this great seaman; his was the pioneering, ours the great reward. He was out again very soon on a voyage to Antarctica, in command of a Government expedition, to discover how far the lands of the Antarctic stretched northward. He did his work, sailing round the great icecap, but he made that voyage memorable by a conquest greater still, for he taught his men how to preserve life and health while they were at sea.

Looking back on all his great achievements Captain Cook believed this hygienic work of his to be the greatest feat of his life. It seemed to him a more stupendous thing than the discovery of Australia. Those were terrible days at sea, when men would die on ships as fast as flies in summer heat. Ships’ crews were broken up and doomed by scurvy and fever, and Cook, who knew more of science than perhaps any English seaman before him, faced this problem like the wise man that he was. He persuaded his men to follow his advice, and trained them by a wise and careful diet to avoid

disease, or, if disease should come, to avert its terror.

There never was a voyage at sea so healthy as Cook’s voyage to Antarctica; only one man died in a crew of over a hundred men; and when the ships came back, and the facts were made known, and Cook’s hygienic science was explained before the Royal Society, the Royal Society gave him its gold medal and honoured him as a benefactor of the race.

So he was. Infinitely more than an explorer was Captain Cook. He set up our flag and established our influence in the greatest territories of our empire, and his name and fame are part of the history of British dominion in America and Australasia. But what can compare with those other two distinctions of this great captain? He taught us how to be healthy at sea; he spread the fame of Englishmen everywhere for chivalry and fair dealing.

They are at the basis of our civilization, these two things. What would the great sea-race have been, where would our far-flung commonwealth have been, if the health of men had not been safe at sea, and if Captain Cook had not made it safe in time to secure the mastery of the sea for the race that most has loved liberty? And as for chivalry, running hand in hand with British freedom everywhere, is it not the very warp and woof which bind our British realms? Captain Cook did nothing ignoble and nothing mean. Never was an explorer more devoted to his men or to humanity, and his treatment of natives opened up golden ways for him.

It was his unbreakable rule to seek entry into new lands with the cooperation of the people he

found there, to practice every fair means of cultivating their friendship, and to treat natives, wherever he found them, with all possible humanity. He would allow no man to be cruel to a native; he would allow no man to lower the name of England or bring dishonour on the flag; and so firm was he, so relentless was he, in this that once, when some of his crew had been unjust to natives, this English captain called together the natives, and brought out one of his own men and whipped him in the presence of those he had wronged.

His Antarctic voyage safely over, and its work well done, Captain Cook went out again, this time in quest of the North-West Passage to the Pacific; and it was on this third voyage of his that the stern justice of this man led to a tragedy as mournful and pathetic as can be imagined.

Storms drove his ships to Hawaii, where the people thought him a god and would have worshipped him. But there were thieves among them, and this man who whipped an Englishman for wronging natives was not afraid to retaliate when a native wronged an Englishman.

When their best boat was cut from its moorings and taken away he decided that the natives needed a lesson. Four boats he manned with armed men and sent them to form a barricade across the harbour to stop any native boats passing. With two other boats he went ashore, landing with about a dozen men, and leaving the rest in the boats in charge of a lieutenant.

He meant to persuade the king to come on board as hostage till the stolen boat had been returned. His plan was just; but his temper was up and he did not show his usual wisdom in dealing with the natives. The men forming the barricade in the harbour were already firing on native boats as they attempted to pass, and the appearance of the armed men who were with him increased the alarm of the natives. As Captain Cook led their king toward the boats an old woman spread a cloth between them and the sea, crying that the king should not cross it. Cook tried to force him on, whereupon the natives took up pebbles to throw at the man who dared to lay hands on their king. Cook’s temper flared. That these people, whose trust he thought he had, should stone him was enough to make him go against his own policy and open fire on them. A few shots from his gun, and then he seized the king’s arm once more, and would have forced him over the old woman’s cloth and to the boat; but a native standing behind him drew a dagger and plunged it first into his shoulder and then into his heart.

Cook fell, mortally wounded by one of the very iron daggers he had had made after the design of the islanders’ wooden ones and had presented to them. As he fell a mad and seething crowd held him down; and this man who never in his life had wronged a native was beaten and hacked to death, natives snatching daggers from each other’s hands for the satisfaction of striking at him. It was, perhaps, the most horrible death an explorer has ever died, and he was, perhaps, the gentlest explorer who ever put to sea.

Those of the crew who had landed with him now opened fire, and the natives turned on them, killing four and wounding three others. One of the boats pulled in and the men swam out to it; but all this time the lieutenant in charge in the other boat looked on and raised not a finger to rescue his captain’s body or save the men pursued by the natives.

Had not the boats forming the barricade seen from the distance what was happening and themselves opened fire, not one of the men would have got back from that shore alive. The lieutenant was received at home with universal execration, but justice overtook him in the end, for 19 years after he had stood by and watched the murder of Captain Cook he was dismissed from the Navy for cowardice at the Battle of Camperdown. Nelson even thought he ought to have been shot.

Captain Cook’s body was never recovered, though when Captain Clerk, whose ship, the Discovery, accompanied him on this expedition, heard what had happened, he hoped that by making friendly advances to the natives their confidence might be regained and the body of their victim given up. At first the islanders mocked at the suggestion, dancing round in the dead captain’s clothes, but eventually they brought to the ship one or two bones and his right hand. These pitiful remains were buried at sea.

So ended the life of one of England’s noblest men. He was the first of all our seamen to sweep the whole Pacific. He helped to fix the British hold on North America; he founded British Australasia; he put a fifth continent on the map of the world. He surveyed more coastline than any other man. He made unknown waters safe for ships. He explored and settled the mystery of the fabled continent of Antarctica. He taught the race that was to rule the seas how to keep health and strength at sea, and he gave it three million square miles to take care of.

Has any man done more?

1731-1841 A.D., South Seas-Hawaii

Kapiolani was a Hawaiian, as fair as the flowers which strewed her island home. She was of high estate, a friend of the royal house, for her husband was the public orator of Hawaii and the king’s counsellor. She was delicate, too, unused to toil and hardship; but she proved to have that strength and endurance, that utter selflessness, which all women seem capable of when such qualities are needed.

The story of her faith and love is as spectacular as its setting. It is a story of Christianity against a dying paganism; this frail woman against the lurid background of a flaming volcano; the delicate white flower of her faith against the elemental forces of Nature.

Hawaii, one of the loveliest islands in the world, is set like a lily in the blue waters of the Pacific Ocean. The salt sea moans around its flower-girt shores, now whispering soft music, at other times terrible with sudden storm.

The Hawaiians were gentle, friendly, as happy as children and as thoughtless. They lived and loved and played, they were beautiful; and all bowed in terror before Pele, the vindictive goddess of the island.

In this lovely group of islands rises Kilauea, one of the biggest and most terrible volcanoes in the world. Its crater is a lake of restless, moving fire, over six miles in circumference. Great black and red rocks are tossed hither and thither, like pebbles in a witch’s cauldron. Over the summit hovers a perpetual vapour lake a gossamer mist, deepening at night to a lurid glow.

Rising up from the crater is a monstrous cliff of cinders and broken lava, now precipitously steep and smooth as a sheet of glass, now rugged and chasmic, where one can climb by perilous paths down to the hard ledge of rock-like lava which bounds the seething lake of liquid fire. Queer stunted little bushes and coarse grasses grow on the mountain-top, and these are spangled with a delicate frost-like tracery formed by the chemical action of the cold air on the mineral vapours rising from the volcano.

It is a fearful and wonderful sight at all times, but in eruption its wild majesty would strike even the most learned men of our civilization with a sense of impotence and awe. It is natural that the wild and primitive people of these islands should have been terror-stricken at this strange

phenomenon, Nature in savage mood, and, fearful of the unknown, should bow down and worship dumbly. As Carlyle says, in a quite other connection: “What we now lecture of as Science, they wondered at, and fell down in awe before, as Religion.”

And so there evolved in the Hawaiian Islands a terrible goddess Pele, who dwelled in the fiery depths of Kilauea. She bathed in the fiery crater, and that was her hair gleaming glass-like in the bushes. The mountain was tabu; only the priests of Pele could live there.

It was especially wrong for a woman to be found there, for Pele, jealous and vindictive, would in revenge shake the island in her fury and destroy the smiling valleys with her fiery streams.

With the progress of civilization the islands around Hawaii became Christianised. Slowly the people gave up their evil practices and forsook their dark superstitions. But still through the years the fear and worship of Pele of Kilauea persisted. Could they not hear her grumbling, and shouting, and holding fierce revelry, shaking the island with her fiendish laughter, belching out her desolating streams in token of her wrath?

Even when the young king forsook paganism and adopted Christianity the priests of Pele still made sacrifice on the sacred mountain, and held the whole nation in fear. Then it was that Kapiolani was inspired to the performance of her wonderful deed of heroism and sacrifice.

She reasoned that if she essayed the difficult ascent up the mountain, and mocked the goddess in her very stronghold, then surely the people would accept Christ without reservation, and the spell of fear which for centuries had been cast over the trembling islanders would at last be broken.

Any man, with a wealth of national culture and civilization behind him would have needed courage to make that ascent; but not only had Kapiolani been born and bred to the worship of Pele, she had to fight in herself the superstitious terror of the former generations of her race who had

bowed down to the goddess.

She knew that she was outraging the oldest belief of her old religion, that Pele would evoke terrible vengeance when she found a woman had encroached upon her sacred territory.

She was quite alone. No man dare encourage her, or wish her godspeed: the fear of Pele was too near and recent a thing for that. But Kapiolani loved her people and she loved Christ, so she put aside her trembling fears, and, strong in love and faith, became God’s champion against the superstitious powers of darkness.

She started on her journey. She was a delicate, coast-bred woman unused to hardship and toilsome journeyings. The path was long and torturous, and it led her upward into cold heights which tried her sorely, gently nurtured as she was in a warm climate.

Jutting crags and rocks, slippery glasslike surfaces, and unstable slopes of lava and cinders wounded her delicate feet. Most terrible of all, there were nerveracking rumblings and tremblings. Steam and vapours continually oozed through the burning soil and lava-crevices; and as she neared the summit the lurid light clung round Pele’s Bath, menacing and terrible, like a forest aflame. Only a little while before several men had been overpowered by noxious fumes from the volcano who could gainsay they had been slain by the outrageous goddess!

But Kapiolani climbed on resolutely, trusting in Christ, and clutching in her hand the sacred berries no woman had been allowed to touch.

The furious priests of the goddess Pele came from out their craggy fastnesses and tried to bar her way. But Kapiolani was possessed of a subtle power. Calm and unafraid she pursued her solitary path, and the priests fell back, amazed and powerless before her.

She made her way down the perilous slope of cinders and loose rock to the very edge of the crater, and flung the sacred berries into its fearful, fiery depths.

Then she spoke:

“If I perish by the anger of Pele, then dread her power; but, behold! I defy her wrath. I have

broken her tabus; I live and am safe, for Jehovah the Almighty is my God.

“His was the breath that kindled these flames; His is the Hand which restrains their fury! Oh! all ye people, behold how vain are the gods of Hawaii, and turn and serve the Lord.”

Kapiolani returned safely to her people, having broken for all time the bonds of superstitious terror which hitherto had bound her trembling nation.

1787-1856 A.D., Asia-Japan

He was one of the sowers of the seed which has ripened into the astonishing transformation of Japan.

Sontoku was born in 1787 and died ten years before the beginning of Japan’s quiet revolution. The name given him by his parents was Kinjiro; his family name was Ninomiya. It was not until after his death that he received the honourable name of Sontoku, which means The Virtuous.

Sontoku, the peasant sage of Japan, comes close to the life of the ordinary people of his country, and his life has been told, his character revealed, his aims and motives laid bare. Through him we may perhaps see some of the elements of character which underlie and explain Japan’s remarkable progress in the last two generations.

Sontoku’s grandfather had collected wealth by hard work and thrift, but the boy’s father gave away or lent his money so freely that his children were brought up in poverty, especially after an overflowing river had covered the ancestral farm with stones and rubbish. The father, too, had such ill-health that he had no means of paying the doctor’s bill except by selling the last of the farms he had inherited. The basis of the Japanese faith is loyalty: to their emperor, to their clan, to their father. To sell the farm would be an act of filial impiety; yet not to pay the doctor was an even greater dishonour to the paternal memory. So he sold the farm. The doctor, however, would not countenance such a sacrifice and refused the money when it was offered to him.

When Sontoku was 14 his father died and the poverty of the family was deepened,

though the boy worked for his mother and two younger brothers by gathering firewood on the distant mountains early in the day and plaiting straw rope and making sandals till late in the night. His industry in these ways, and in helping to repair the dykes that guard against floods, was unceasing. Then, when he was 16, his mother died and he had to live with an exacting relative who would not let him have oil for his studies at night. But by cultivating rape-seed on unused ground he made enough money to buy oil for secret reading after the family had gone to bed. By cultivating waste land he eventually grew enough rice to enable him to begin life on his own account, and after much work and hardship he was able to save enough to buy back the family farm.

Sontoku now married and settled down. The head retainer of the chief of his clan, hearing how he had restored his fortunes, sent to ask his assistance as he had ruined himself by falling hopelessly into debt. So Sontoku left his home for five years, took charge of the affairs of the chief retainer, exhorted him to repent and practise self-denial, gained the goodwill of his servants, entirely restored his good fortune, and divided the money he received among the servants.

The chief of the clan, who was also chief adviser to the Military Governor of Japan, had now formed such a high opinion of Sontoku’s ability and unselfishness that he wished to employ him in a high position; but the higher officials looked down on him as a farmer, however clever he might be. So further practical tasks were assigned to him. The first was to reform a district of three villages where the people were poor, idle, lawless, and corrupt. Much money had been spent and wasted on these villages. Sontoku fixed the time for this reform at ten years.

At one time it seemed that failure was threatened, and Sontoku, fearing the fault might be in himself, retired quietly to a temple for three weeks of prayer and fasting. Then the people who had been opposing him were filled with fear lest they should lose his services and petitioned him to return. In the end, as a result of the methods he adopted, the villages became models of industry, happiness, and prosperity, and people from other districts came in throngs to ask for Sontoku’s advice.

By his observation Sontoku also foresaw the coming of a famine and prepared for it, storing grain in readiness, so that when it came he was the means of saving thousands of lives by sending supplies to districts which had been less provident. He also trained in his own methods many of the headmen of villages and retainers of the great lords who managed estates.

Finally, when he was 66 and worn by his labours, having all his life dressed and fed in the simplest peasant fashion and spent all his earnings in helping the poor, he was instructed by the Government to reform the poverty-stricken mountain district of Nikko.

Sontoku knew very well that his strength was insufficient for so great an enterprise, but he undertook it, and for three years taught the people in every village to love one another, to believe in the nobility of work, to improve the irrigation of their fields, and to recover waste lands. Ill, worn out by these labours by day and his constant teachings by night (for many disciples gathered round him), he died, honoured by all, at seventy.

So much for the life of this wise and good man. What were the teachings on which this noble life was based; the teachings that have perpetuated his influence among his people?

Sontoku based his teaching on four principles. First came sincerity: truthful, straightforward dealing, untainted by guile or selfishness. Secondly came industry, the foundation of all honest living. As he expressed it, Heaven and Earth and all Creation are ever at work without repose, and

there is no true place for anyone in the Universe who will not take his share of work. Every man must give something to the world which has given him all he has. We must win on our way and keep it by our labour.

But his third principle was also of vital value to live simply and always below the amount one has earned. This, he pointed out, was the one way to freedom from anxiety about poverty and to provide the means for fresh enterprises, or what we call capital. The true use of dress is for warmth, not for ostentation, and the simplest foods are the most nourishing and conducive to good health. But this, it may be said, is not more than commonplace prudence, and may easily lead to avarice. No; that is securely repelled by the fourth rule of benevolence and human helpfulness: to give away unnecessary possessions in order that they may be utilised in the service of mankind.

Toward this end all the energies of Sontoku’s life were exerted. First came right feeling, sincerity; then training in self-restraint, against sloth and waste; then recognition of the idea that we all live to carry out the Will of Heaven, and can best cooperate with that Will by repaying to mankind all the good with which we have been blessed. This was living according to the Law of Love.

Some people may still say this barely goes beyond a doctrine of economics. But Sontoku’s thoughts rose beyond mere economics. He had a wider view of the government of the Universe, as may be seen in a translation of some of the verses which he composed. For example:

This brief abode of clay

To Him Who framed it and Who rules it still I dedicate, and pray Bless all Thy creatures frail, and guard from ill. The love for one’s own child Which Nature gives to each.

That wider Law of Love

The Path of Right doth teach. In simple faith the fearless mind Yearns for the future still unknown; Doth not the Father of Mankind Reign on His everlasting Throne?

Sontoku expressed his own aims in life in these words: “My wish is to open up the wilderness of men’s hearts, to sow therein the Heaven-given seeds of goodness, to cultivate charity, righteousness, wisdom, and gentleness, and to reap therefrom a harvest of good fruits.”

It was the philosophy of the Peasant Sage of Japan and it will suit us all whether we belong to East or West.

Chapter

10

Adoniram Judson

1788-1850 A.D., Asia-Burma

It was a New Englander who first gave to the Burmese the Bible in their own tongue. In the history of the Christian Church in Burma Adoniram Judson holds the place that Carey has in India. When he sailed from America in 1810, the first of a vast army of missionaries to leave that land, he had no intention of settling in Burma. On his way to London he was captured by a French privateer and imprisoned on board ship and in France. An Englishman discovered him and secured his escape to England by bribing the gaoler. Returning to America he married Ann Haseltine, a brave and gifted woman who was to share in his romantic life in the East; and in 1812 the two set out for India. The East India Company would not let them settle in Calcutta, but they were there long enough to see Carey and his colleagues at Serampore. After some time spent in Mauritius they went to Rangoon in Burma. At that time this city of ten thousand inhabitants consisted of wooden huts and pagodas, dirty and muddy. For a long time Adoniram and Ann toiled at the language. Not till they had spent six years there did they baptise the first Burmese into the Christian religion. When they were able to preach in the open and converts were won they met with much opposition; but things were looking brighter in 1824, when by a royal command they had established themselves at Ava. The interest of the Court was won in part by the medical skill of Dr. Price, who had joined the Judsons and who possessed a galvanic battery which greatly delighted the king. A small house was built for them on the bank of the river. There Ann formed a school, and they settled down, prepared for a peaceful time, with the favour of the Court to secure them a hearing.

But it was not to be for long. War broke out between England and Burma. The Burmese were astonished at the audacity of the white people who dared to challenge their mighty race. At once they began to suspect that these Americans were spies. As the Judsons were preparing for dinner, one day, in rushed an officer with a black book, and with him one who was known to be an executioner. They seized Adoniram and dragged him away to prison. The imprisonment lasted for eleven months.