12 minute read

Hidden Anatomy

IN THE WORKS OF MICHELANGELO

DISCOVER SECRET MESSAGING IN ARTIST MICHALANGELO’S ICONIC REPRESENTATION OF THE BOOK OF GENESIS ON THE CEILING OF THE SISTINE CHAPEL. // By Alexis Griffith //

Advertisement

A

B

C

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, known best simply as Michelangelo, was a painter, sculptor, poet and master anatomist of the Italian Renaissance during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. With the Renaissance brought the major intellectual movement called Humanism, in which experimentation and the scientific method began, as well as the effort of artists to perfect their portrayals of the human form1. Among these artistanatomists was Michelangelo, who developed a great understanding of human anatomy from performing countless cadaver dissections. It is speculated that he paid particular attention to understanding gross neuroanatomy by dissecting many brains and spinal cords, and also by trading anatomy studies with his contemporaries, including his rival Leonardo da Vinci. Although responsible for many great works, including the famous Statue of David, Michelangelo’s painted ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City is arguably his greatest and most analyzed work. Comprised of nine central panels depicting different scenes from the book of Genesis, including the well-known Creation of Adam, Michelangelo showcases his abilities as a master artist. It wasn’t until recently, however, that art historians began to analyze hidden shapes and messages within these depictions. One major hidden theme of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling appears to be the representation of different anatomic structures, particularly that of neuroanatomy. It is suggested that he incorporated these anatomic structures in order to portray allegorical concepts as well as to communicate personal struggles in his own life. There are a few discrepancies among the interpretations of these alleged hidden structures, as we will discuss, but each dissertation can be seen as correct in its own right, and it is ultimately up to the viewer to decide what Michelangelo was trying to communicate.

THE BIG PICTURE

Before we delve into the individual panels of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the cumulative panels tell a story, other than the book of Genesis; a story about the development of the human brain. The first four panels (FIG 1), starting from the west end of the chapel, illustrate the days of creation from the book of Genesis, but Michelangelo also snuck in images of brains during different evolutionary developments to show the relative growth of the telencephalon and cerebrum1 . In the first panel, The Separation of Light and Darkness (FIG 1D), Michelangelo appears to have inserted the shape of what looks like a primordial fish brain within the contours of God’s throat (FIG 1E)1, representing one of the earliest vertebrate brains. There are, however, other more accurate interpretations of this structure, which we will discuss later. In the next panel, The Creation of the Sun, Moon and Plants (FIG 1C), we see behind the main image of God surrounded by cherubs, an image of what appears to be an amphibious brain, or perhaps a non-primate mammalian brain1. In the subsequent panel, The Separation of Land and Water (FIG 1B), we see a slightly more evolved nonhuman primate brain. Another more likely interpretation of this panel is that Michelangelo is representing a kidney, which we will also discuss later. The last panel in this series is The Creation of Adam (FIG 1A), in which we see God giving life to the first man. In this image we see God extending out from what appears to be a fully developed human brain (FIG 7), complete with structures suggesting a pituitary stalk, vertebral artery and brainstem2. Ashford et al. believes this linear depiction of an evolving brain suggests the evolutionary growth of the cerebral cortex in humans, representing a progressive increase in brain complexity1. I personally believe this could also be a representation of the fetal brain development, as we know that embryologically our brains grow and develop through similar shapes as those depicted in Michelangelo’s paintings. Allow us now to delve into additional and/or opposing views on hidden structures and their intentions in the individual panels of the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

LIGHT & DARK

The first panel on the west end of the Sistine Chapel is titled The Separation of Light and Darkness, in which God is beginning his creation by first separating light from dark (FIG 1E). This particular panel is located directly above the altar and was undoubtedly intended to portray God in all his glory; so it is interesting that Michelangelo inserted anatomical abnormalities, especially as a master anatomist. One large anatomical error is in God’s throat, which we briefly touched on earlier. While some believe this odd structure to resemble a primordial brain, another more probable interpretation is that it is actually the ventral view of a brainstem (FIG 2), along with perisellar and chiasmic regions2 . From proximal to distal, we see the upper cervical portion of the spinal cord, medulla complete with anterior median sulcus, pons, and the sellar region of the brain. The central depression seen in the bottom of #LIFELINES | 7

God’s beard can even be compared to the frontal aspect of the medial longitudinal fissure of the cerebrum2 . One indicator that this is not merely an accidental error in anatomy, but a purposeful representation, is that there appears to be an irregular light source only on this ventral aspect of God’s throat that is different from the rest of the composition2 . We know Michelangelo to be a master painter, especially that of light depiction, indicating that he was attempting to highlight this anomaly. Another indicator is that when comparing God’s throat in this depiction versus others on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, all from the same three-quarter perspective, Michelangelo specifically drew in this much more complicated structure in this portrayal only. It is speculated that he chose to hide the ventral brainstem within God’s throat area due to the similar conical structures as well as the proximity to the correct anatomical location2 . While the theory that Michelangelo was attempting to depict a brainstem within God’s irregular throat anatomy is generally accepted, some suggest that he actually intended to depict a goiter3. Suk et al. disregard this opinion, however, since it simply does not look like a hypertrophied thyroid gland, and Michelangelo was actually able to observe this condition closely in the people of the Po River valley in Lombardy, where goiter was an endemic2, so we would expect him to know how to accurately portray it.

A

C

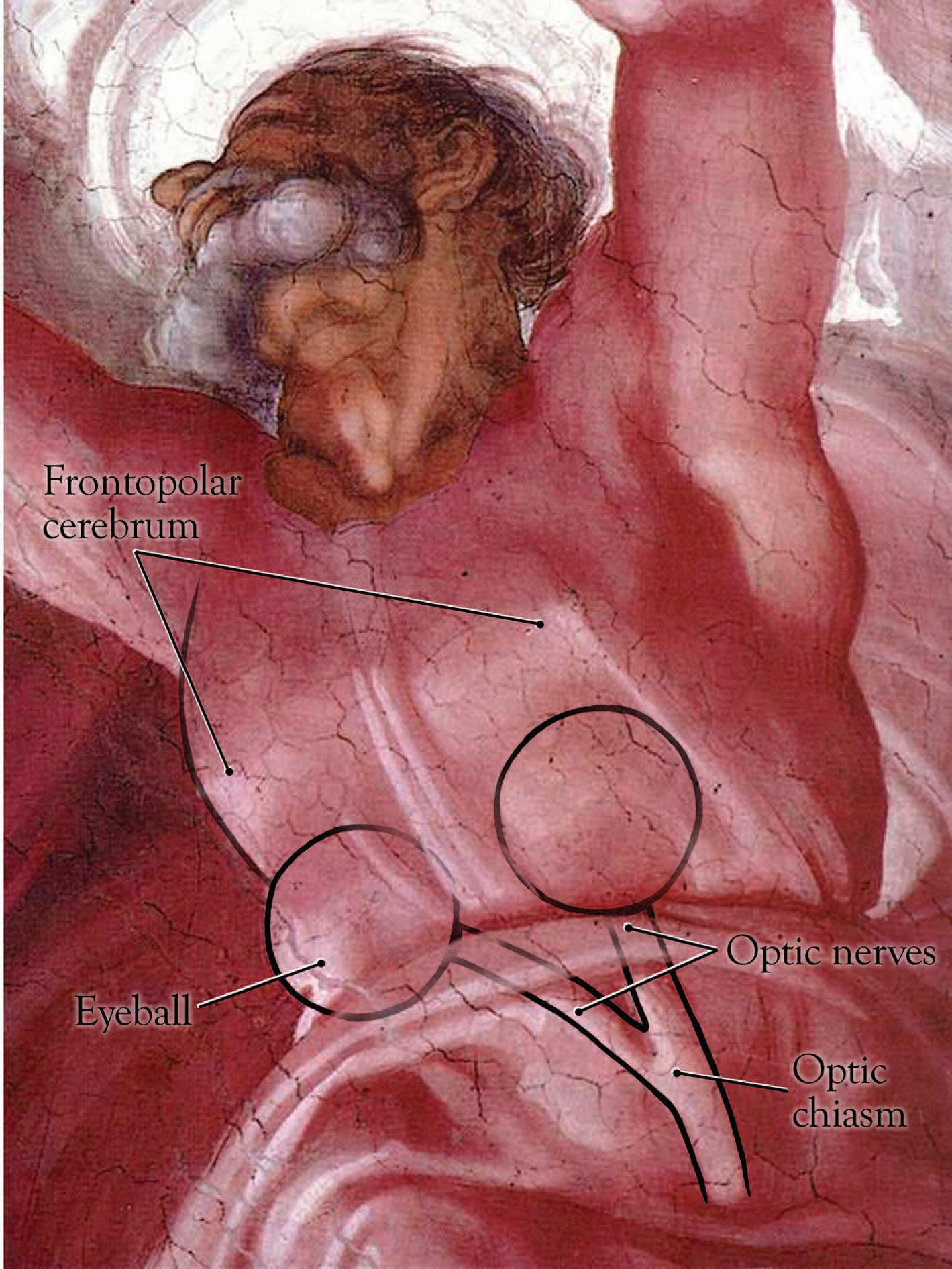

IRREGULAR ROBE

As we move down from God’s throat to his torso, there are some more abnormalities in the ways that his robe flows and folds. First of all, there is a very obvious tubular structure with a longitudinal cleft traveling down the middle of his chest, which is not seen in any other of his depictions (FIG 3A). We can easily assume that Michelangelo was alluding to a ventral view of the cervicothoracic spinal cord, which is even an offset continuation from the brain stem in God’s neck2 . Another odd shape seen in the torso area is a “Y” shape just below the waist (FIG 3B), which some believe alludes to the optic chiasm and optic nerves2. Although we now know that the optic chiasm is more of an “H” shape, anatomists during the Italian Renaissance were still figuring out the exact anatomy, so some depictions from that time show the optic chiasm as the “Y” shape, as is seen here2. We can even imagine the optic nerves traveling superiorly and ending at the two masses that appear in the subcostal region, which could very well be representing eyeballs (FIG 3B). This particular assertion is definitely more of a stretch, but as this panel is depicting the beginning of light and dark, Michelangelo may have been inspired to allude to the organs of vision and their neural structures2. Another interpretation of the four masses that appear on God’s chest, which is my own personal observation, is that they are representing the corpora quadrigemina from the tectum of the dorsal aspect of the midbrain. God’s laterally ascending arms could be seen as the two symmetrical structures

B

that make up the thalamus, which is anatomically located superior to the corpora quadrigemina.

LAND AND WATER

Moving a couple panels east on the Sistine Chapel ceiling is the third painting titled The Separation of Land and Water, which some believe has a more intimate connection with Michelangelo’s life. It is documented that Michelangelo suffered from nephrolithiasis, with recurring bouts his entire life, as well as subsequent obstructive uropathy and urinary tract infections4. This caused him immense suffering that he has documented himself in correspondences, poetry and, of course, his paintings. Based on Michelangelo’s personal interest in kidneys and urinary function, the structure behind God in this panel, that we previously discussed as appearing as a non-human primate brain, is alternatively thought to be a bisected right kidney (FIG 4)4 . We can even imagine that where God is emerging is the renal pelvis, while the bunched robes and fabric hanging down represent the ureter and renal vasculature. In addition to this theory, we can analyze one of the four male figures that border the main image of God. This figure in the bottom left corner with his back turned to the viewer appears to be surrounded by two kidney shapes created by bunches in the fabric directly in front of and behind him (FIG 5), which coincidently correspond to a right and a left kidney. This figure also appears to be grimacing and arching their back in such a distinct way as to allude to suffering, specifically from kidney pain4. The costovertebral angle on his back is also quite pronounced, which we know is generally where the kidneys are located from a dorsal orientation. What makes the connection of this depiction with Michelangelo’s experience with kidney stones truly interesting is that this painting is literally showing the separation of land and water during God’s creation. During Renaissance Italy, much of what was known about kidney function was from the ancient Roman physician Galen, who taught that the kidneys are the organs that separate solid from liquid in our bodies5. This idea makes an astounding parallel with the theme of this particular panel on the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

A

CREATION OF ADAM

Lastly, we will discuss the arguably most famous work of Michelangelo’s, The Creation of Adam, which is the fourth panel from the west side of the ceiling. Now, there are two main theories on what Michelangelo was attempting to portray in the hidden imagery of this painting. Firstly, some argue that the large structure that God is emerging from is a brain (FIG 6), which corresponds with the previous theme of evolving brains6. This midsagittal view of the cerebrum is even complete with shapes that allude to a pituitary stalk, vertebral artery and brainstem, and the flowing appendage coming off from the upper right aspect of the brain is said to represent the meninges1 . While we know that this painting is depicting God giving life to the first man, Michelangelo’s choice to show God emerging from a brain also suggests that he is endowing him with intelligence as well6. An opposing, yet equally perceivable theory is that this structure is actually representing a postpartum uterus7 . Just as with the brain theory, there are quite a few parallels between this image and an anatomically accurate postpartum uterus. First off, the way in which the structure is

FIG 4 B FIG 3

painted appears as if Michelangelo was trying to depict a hollow organ. What appear to be folds inside this structure can represent the folds of the mucosa in a postpartum uterus. We know that under normal conditions these aren’t present, but are only apparent after delivery due to the subsequent retraction of the uterine muscle. The fissure that we see in the lower left aspect of the structure has been identified as the uterine cervix as it bends towards the inner part of the structure7. The flowing appendage in the upper right corner, which was previously identified as part of the meninges of a brain, is seemingly more accurately compared to a uterine tube in this theory. A great compliment to the suggestion that God is emerging from a postpartum uterus is the imagery in the lower left aspect of the panel where Adam is laying. He appears to be resting on a rock, and the concept of rock is historically symbolic of the “generating mother”, as many mythological divinities across many cultures arose from rock7. Behind Adam and the rock is a blue outline that appears as a silhouette of a woman’s body, with the breast and nipple located just above Adam’s head. Some believe this idea of God emerging from a postpartum uterus, together with the allusion of the generating rock and female body, correspond better with the title and concept of life-bearing in this particular painting. As we discuss the possible symbolism of allegorical imagery, we must take caution in our interpretations. Michelangelo, along with most historic artists, did not write a guide to his paintings, and accurately interpreting historical works is challenging with our contemporary viewpoints and biases. The art historian and neuroanatomist Michael Salcman cautions us that these modern parallels that we draw from historic works could simply be the result of “cultural ideation superimposed on otherwise non-descriptive images”8. There is a well-known phenomenon is psychology in which one suddenly perceives an item in a complex field which they were unable to see before. This psychological effect combined with experiences from our own lives can be an attribute of these double entendres that are characteristic of historic art. While there is controversy as to whether or not the images that are perceived as anatomical structures were used intentionally by Michelangelo, the similarities between his paintings and anatomical structures are too similar to be left to chance, and we know that as a master painter and anatomist he is very unlikely to make such incompetent mistakes. This aside, the beauty of art is that it can be highly subjective, allowing individual viewers to see and take from it what they want, without being right or wrong. One could say that this is why Michelangelo blurred the lines between biblical themes, anatomical themes and maybe even other themes that have yet to be realized, in order to cater to the perspectives of all that would view his masterpieces. §

FIG 6 FIG 5