3 minute read

A BEEF FARM IN AVILA PROVIDED A MYTHIC SPACE FOR THIS WESTERN

BLICK

going to be a challenge to make it look and feel authentic. “I had heard, I think it was Jimmy Stewart, say 'The frst clue to a good Western is a slim script' — I took him to heart. These were slim scripts, made even slimmer in the edit. Whenever I could, I honed them down. They started at an hour each, we got them down to 50 minutes. Emily had a lot to do with this, as did the Amazon team. The last episode is just over an hour but I feel it earns it. The key to the story’s rhythm is in the character of Eli. He speaks to it; the less said, the more an audience can hear what is.”

Advertisement

And, of course, most important is the look: if it doesn’t look like a Western, it’s not a Western. “It’s all about the light, how it falls on landscape and character. Cinematographer Arnau Valls Colomer and I studied the genre carefully, particularly its mid-20th century period,” Blick says. “On location we scheduled for the late afternoon when the dust was up and the sun low. Back-lit by sun and front-lit by arc light, I found the results impressive, although it could be blinding to the actors. We shot 2.39:1 CinemaScope using a limited selection of Panavision Anamorphic lenses. I didn’t want to move the camera, so spent a good deal of the time fguring out where best to place it so we wouldn’t have to.” And he drew inspiration from past greats: “It’s pretentious to say I picked this up studying Kurosawa — but so what? I did. And George Stevens. And Eastwood. And Anthony Mann. I want to say John Ford but every time I hit up against The Searchers ([956] and see Chief Scar played by a blue-eyed German, I just know we’re in trouble… It’s the same for Audrey Hepburn in John Huston’s The Unforgiven [1960]. There’s actually quite a bit to admire in the picture — issues of prejudice and intolerance — but then the casting kind of turns that on its head.”

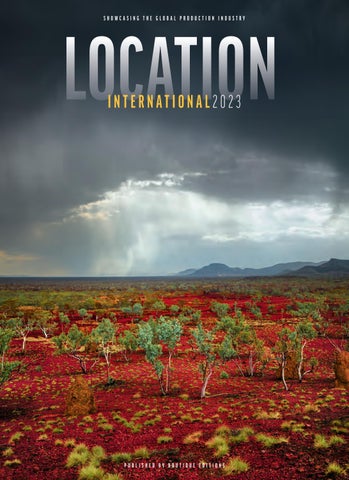

As Blick says, Westerns are all about the light — and also the locations. And The English gets that right from the outset. "In the striking opening few minutes, the locations load the viewer with both context and emotion: and at no point does the viewer think, ‘Hey that’s not America, that’s Spain!’

“The actual period of the classic cowboy was approximately 30 years; the following 130 years has been almost entirely myth, built as much by our televisions and cinema as by the Chisholm trail itself [the post-Civil War route to drive cattle overland from ranches in Texas to Kansas]. The Western lives in our imagination — and it can travel,” Blick says. “So when COVID chased us frst out of Kansas then Alberta, I was intrigued to look to Spain. As it turned out, we got lucky. I can see, and hear, in every frame just how lucky we were to make this with such an experienced and committed crew whose involvement in the genre often stretched back through generations.”

Blick says he was aware from the outset that Sergio Leone’s and Clint Eastwood’s preferred region, Almería, wouldn’t work for a story set in Kansas and Wyoming. “Luckily our location scout took us to a huge beef farm in Ávila outside of Madrid. With the grasses, rock formations and horizontal light, it provided a perfect mythic space for this Western.”

Back to the opening scene and the only building in the vast wide landscape is a tiny, run-down wooden hotel, in the middle of nowhere. The questions that are raised in the viewer’s mind are many: 'Who works there? How do they get there?, And where from?' “The designer, Chris Roope, understands by research and intuition that one structure within the landscape can read so much more powerfully than many. This outlook also renders him very popular with producers — it’s our third, and hopefully not last, time of working together. The hotel was our build — as were almost all of the location sets seen in the production.”

The vast majority of the series was flmed on location. “You just wouldn’t get that light or landscape any other way,” Blick says. “Taking this level of circus to that environment presented great logistical challenges to our producers. But under the management of the simply genius horse-master, Hernan Ortiz, the whole pace of the production was dictated by the rhythm of the horses. This was an entirely benefcial experience.”