13 minute read

BUDDY GUY DAMN RIGHT FAREWELL

WITH SPECIAL GUEST: TOM HAMBRIDGE

Friday, April 28, 7:30 pm

Advertisement

At age 86, Buddy Guy is a Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductee, a major influence on rock titans like Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, and Stevie Ray Vaughan, a pioneer of Chicago’s fabled West Side sound, and a living link to the city’s halcyon days of electric blues. Buddy Guy has received eight Grammy Awards, a 2015 Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award, 38 Blues Music Awards (the most any artist has received), the Billboard Magazine Century Award for distinguished artistic achievement, a Kennedy Center Honor, and the Presidential National Medal of Arts. Rolling Stone ranked him #23 in its “100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time.” In 2019, Buddy Guy won his eighth and most recent Grammy Award for his 18th solo LP, The Blues Is Alive And Well. His most recent album is The Blues Don’t Lie

TICKETS

Adults

$65 / $85

All Students

$25 limited availability

Order online hancher.uiowa.edu

Call

(319) 335-1160 or 800-HANCHER

Accessibility Services

(319) 335-1160

Individuals with disabilities are encouraged to attend all University of Iowa sponsored events. If you are a person with a disability who requires a reasonable accommodation in order to participate in this program, please contact Hancher in advance at (319) 335-1160.

GrEG WhEELEr aND

ThE POLY MaLL cOPS

Manic Fever

HIGHDIVERECORDS.BANDCAMP.COM

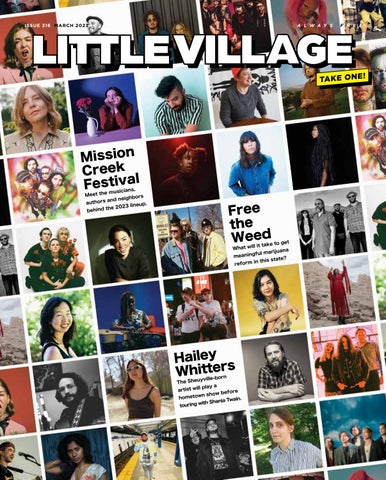

MCF: Greg Wheeler and the Poly Mall Cops, Gabe’s, Iowa City, Saturday, April 8, 7:30 p.m., included with pass ($55-110)

You didn’t realize you were waiting for this moment. But I promise you, you were.

Later this month, on March 24, just a couple weeks ahead of their appearance at Iowa City’s Mission Creek Festival, Des Moines punkers Greg Wheeler and the Poly Mall Cops will drop their debut fulllength, Manic Fever. If, like a good Iowan music nerd, you’ve been following Greg Wheeler’s career since his time with Cedar Rapids band The Wheelers, then you’ll be absolutely ready for the wild, frenetic beauty of this aptly named album.

The 12-track release includes all three songs from their 2017 7-inch split and nine additional tunes to give you a crick in your neck as you jump and thrash along. Track four, “DGASAY,” one of those carried forward from their earlier release, is a classic punk vibe, channeling the ’70s obsession with sped-up surfer rock tonality. It’s the most polished track on the album, the one begging to be released as a single.

The following track, “Nothing,” is one of the album’s standouts, delightfully subtle following the fiery vehemence of “DGASAY.” It’s a track to get lost in, balancing seemingly straightforward lyrics—“There’s nothing much left to do / Except completely obliterate you / And there’s nothing left to say /

I want your face to go away”—with a wistful melodic structure, espe cially on the chorus, that reveals the lyrics to be pure bravado.

The title track is another that grabs your ears, 1:42 of quick addictive vo cals and swirling instrumentation that make clear just how much fun they had composing these pieces. “Slowly Erasing You,” another 2017 re-up, is next, one more track that dances around and puts the lie to its lyrics. Then “Waste Away” takes control of the narrative, with lyrics that feel more poignant and true (“Don’t let go, I’ll float away”) couched in driv en, drum-forward desperation that demands attention. This trio of songs in the album’s third quarter encapsu lates the themes and philosophies of the whole; the three are worth loop ing on their own a few times through.

Closer “Fast Forward” is the per fect capper, all garage grunge grit and grime locked in conversation with the listener, begging for the emotional turmoil of the album to be over. I’m generally a fan of albums that bear repeating, that can be lis tened to over and over. But this is a deeply satisfying conclusion that hints at the possibility that the at tempts at closure teased throughout might finally be realized.

Manic Fever is simultaneously nostalgic and contemporary, peak 2007 but without feeling retro. If I said, “goth pop-punk,” you, dear reader, would likely respond, “Oh, you mean emo?” But no. I do not mean emo. The Poly Mall Cops are more Joy Division than My Chemical Romance. And there’s a ’90s fuzz overlay that gives the al bum a very Love Among Freaks, Clerks soundtrack kind of vibe, along with just the right amount of raucous drums, reminiscent of clas sic, Brett Reed-era Rancid.

In other words, it’s like a decadent meal from the punk rock buffet. You think you have a grasp on their style, then they throw a wild card at you— and make it work every time. They deliver pop punk filtered through the miasma of pandemic times.

—Genevieve Trainor

Emily Kingery’s Invasives opens in a garden and closes in a garden, repeatedly returning to Eden and tearing it down with one consistent throughline: that which is invasive.

The opening poem, “Musk Thistle,” weaves together two concepts such that they are inextricable. It talks about pulling weeds and ponders the difference between a weed and any other plant, relating that imagery to the way we accidentally sow figurative and digital seeds in our own lives.

Our speaker lingers in her childhood, hands us Barbies and woodchips, and pulls us through basements and playgrounds, laying groundwork for ways our desires hold us captive. Kingery repeatedly gives visceral illustrations of how lovers leave deep-rooted, impossible traumas in their wake. She makes us fall in love with bad men, asking, “Who argues / with men who undress you / the way summer does / to spring,” in the poem “April.”

She reminds us of young love, unrequited love, the pain of trying to exist in spaces not made for you. This collection hit closer to home than I could have anticipated and in darker corners than I’d like to admit. I think that’s an accurate picture of Invasives: a pretty package with ornate scaffolding built around our hauntings.

It’s probably true that not everyone has had experiences like those outlined in Invasives: abusive lovers, the allure of toxins, the belief that belief alone can save us. But

Kingery’s felicity is unparalleled— she pries universals out of snapshots from slumber parties and crushing on Indiana Jones and the specific boredom that means the end of coming of age. We are not all from the small town in which our narrator learns how to want and how not to love, but we do all learn these things.

Reading the poem “Toxicity” (the title and refrain derived from the System of a Down song), I understand how the unrequited can be romantic. Kingery’s language is potent, her scenes developed and raw. The book itself is invasive. Where you might expect to feel voyeuristic, instead you wear the narrator’s skin, her story coiling inside you.

What really gives these poems power is their bald-faced realism. The language is often flowery, but the images depicted here are disaster photography. They are high-contrast black-and-whites of crime scenes and personal tragedy, the best of which combine soft, natural

TaYLOr BraDLEY

There’s No Place Like House BARNES & NOBLE PRESS

Much is absent in Taylor Bradley’s latest book.

That observation is not an assessment of the component parts of the book—which catalogs segments of Bradley’s life from 2018 to 2020— rather, “absence” is the aching touchstone of this well-built text.

Published in late 2022 by Bradley, a 2013 University of Iowa graduate, There’s No Place Like House is a memoir, presented be looking for narrative grounding. Thankfully, Bradley writes with a deft hand and is quick to define these vacuums after the first essay. elements with the grit of drugs or basement parties. As in “Tricks,” “I have read enough / to know I am half-gone already. I have cut enough flesh / that when the crosscut saw is flourished in the garden for the final trick, my body will disappear on its own.”

The most important absences are noted in the beginning and often take the spotlight in multiple essays. In particular “One-Inch Planet,” “Mary Poppins for Damaged Men” and “The Breakup” etch wretched failings with a surprisingly sympathetic hand.

Bradley’s time in the book is mostly focused in Los Angeles, while dipping in and out of London, New Orleans and Grand Junction, Colorado, among other places. As the essays continue, a somewhat recurrent cast of characters begin to take shape. An 80-yearold neighbor, an aging mother, a semi-estranged father and a handful of friends reappear throughout, but—keeping with the conceit of the book—none feel like permanent players, even when their presence (or lack thereof) is powerfully felt.

Dozens of photos illustrate settings, objects and people throughout the book. Many of these images lack distinguishable human faces, and when distinct faces do appear, it’s often in old, smiling family photos that add texture to Bradley’s already nuanced prose. Regardless of subject, these images tend to extrapolate on the text, rather than merely represent it.

There are poems in here about happy things, beautiful moments of confidence and change, and the collection even gives opportunity to the reader to choose their own adventure with the way the book ends. Invasives is a fever-dream journey through trauma, but you get through it.

—Sarah Elgatian

as a series of photographs and essays. These narratives extend from 2018, in the immediate aftermath of a failed, decade-old, romantic relationship, to mid-2020 when COVID swallowed the globe.

Prior to this, Bradley has published poetry collections and written plays, at least one of which was part of the UI’s 10-Minute Play Festival in 2012.

Throughout There’s No Place Like House, Bradley establishes a slew of lackings, observing things as “not-my TV” and “not-my Grandpa” and the house of an “almost mother-in-law.”

Defining things in the negative risks losing a reader when they may

The book’s title alludes to a line repeated in The Wizard of Oz by Dorothy Gale, played by Judy Garland. When Dorothy is spirited away to the land of Oz, she’s followed by her house but not its content. She has to get back to Kansas, back to her home.

At the start of this book, the narrator prepares to leave a house that is not her own. But unlike Dorothy, she is not beckoned “back to Kansas.” That is a place she intentionally fled. Without that clear and guiding star, our protagonist’s path is more tumultuous than any yellow brick road.

—Isaac Hamlet

SEaN aDaMS

The Thing In The Snow

WILLIAM MORROW

The Thing In The Snow is set in a remote location “where the snow never melts.” Given my fiery hatred of Iowa winters, this was already enough to catapult me into a headspace of inexplicable tension that kept me turning the pages of Sean Adams’ latest novel.

Our narrator, Hart, is a supervisor tasked with making sure the Northern Institute, formerly a research facility, remains a place where “research cannot possibly occur.” The abandoned state of the Institute makes the presence of Gilroy, the last remaining researcher at the facility, even more curious. Hart is in charge of two subordinates: Gibbs, who Hart suspects is secretly plotting to take his job, and Cline, who he describes as “easily distracted and unintelligent.”

The staff doesn’t know their coordinates, they don’t know what research used to be conducted there, they don’t know the exact temperature in the facility. And they don’t know what the ominous black shape near the eastern wing of the building is, the titular “thing in the snow.”

In accordance to the wishes of Hart’s superior, Kay, the team strives for “efficiency,” spending their days carrying out their assignments: opening and closing doors to make sure they are functioning properly, using golf balls to check if table surfaces are level, sitting and shifting around on chairs to make sure they are sturdy enough, etcetera.

Hart regards this busywork with the utmost seriousness, obeying orders and filling out endless forms.

Despite managerial aspirations, Hart is seemingly at a professional dead end. It’s bad enough that our narrator is insecure about his leadership status, but like his team, he is left in the dark about practically everything.

Seeing the title, my mind flashed with images from John Carpenter’s 1982 film The Thing, a story centering on a team of researchers in Antarctica pitted against an unfathomable threat. A notable influence on that film is the work of horror scribe H.P. Lovecraft, who penned his own tale of an Arctic expedition team in his 1936 novella At The Mountains of Madness.

Thinking I had ventured across this frozen terrain before, I discover Adams once again subverts all expectations save one: delivering a superb novel in another year seemingly destined for the dumpster fire (a lesson I should have learned from reviewing the author’s debut novel The Heap in 2020.)

Here, Adams lures readers into a

Tara a. BYNUM

Reading Pleasures: Everyday Black Living in Early America

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS

Book Matters: Tara Bynum, Prairie Lights, Iowa City, Wednesday, March 22 at 7 p.m., Free and fears stalk our thoughts; the uncertainty of the future is often a hovering cloud. It’s a remarkable phenomenon that these early Black Americans found and expressed those pleasures. It “bears proof,” Bynum writes, “of the taking care of or the tending to an inward self.” world as claustrophobic as a snow globe, then shakes things up with a flurry of satirical commentary on the surreal and absurd nature of workplace culture. I am reminded of the space truckers in another Carpenter film, Dark Star (1974), and the cubicle dwellers in Mike Judge’s Office Space (1999). However, such comparisons last only briefly, as Adams gifts readers a uniquely hilarious yet frightening vision with The Thing In The Snow

Scholar Tara A. Bynum, an assistant professor in the University of Iowa Departments of English and African American Studies, is exploring interiority—and exemplifying it.

The existence of these examples, and Bynum’s choice to present them in this way, is reminiscent of current trends toward defiant joy: from the ideas of Black boy joy and Black girl magic to the insistent refrain that “trans joy is resistance,” historically marginalized communities in the U.S. and across the world have been advocating for the power of expressive pleasure instead of taking pleasure in expressions of power.

(Reviewer’s Note: Special thanks to Beaverdale Books in Des Moines for lending an emergency copy of the book to Little Village for review.)

—Mike Kuhlenbeck

In her recently published monograph Reading Pleasures: Everyday Black Living in Early America, Bynum leverages her research in pre-1800 Black literary history for a deep dive into the lives and writings of a selection of early Black intellectuals. Beginning with Phillis Wheatley and moving on to names perhaps not well-known outside of academia, she examines the ways in which each pours their interiority onto the page, how they hope, how they dream and how they love. And as she does so, she sinks into the subject matter, revealing her own pleasures at every turn.

The pleasures in question, she advises in the introduction, are not sexual or even necessarily physical. “I’m describing what looks like those quotidian and simple pleasures that make life easier,” she writes. And, quoting James Baldwin, invokes a definition of “sensual” that embodies the ability to “respect and rejoice in the force of life, of life itself, and to be present in all that one does, from the effort of loving to the breaking of bread.”

This is no easy task, of course, even in the modern day. Anxieties

Writing about pamphleteer David Walker, Bynum is direct in discussing his obvious anger, but argues that it’s “well-intentioned and purposefully excessive.” And it is utilized in pursuit of happiness: “namely,” she writes, “a world where his brethren are no longer enslaved.”

What is most beautiful about these chapters is the way that Bynum maintains a delightful voice, a first-person perspective that centers her own pleasure in the researching and writing of this book. Her curiosity permeates each page. “I still wonder sometimes,” she writes, “what Phillis Wheatley thought about as she brushed her teeth.” It’s a tongue-in-cheek moment—Bynum acknowledges self-effacingly that she’s aware toothbrushes weren’t around in Wheatley’s time—but it gets at the heart of her questioning. There’s a lot that these explorations of interiority can reveal, but we can never know how the authors truly see themselves.

Through these intertwined readings, Bynum searches for throughlines and truths, finding relevance in the writers’ shared Christian faith and tracing that influence. But mostly, she models for the reader what it is to read with curiosity and how to allow the interiority of others to inform our own, resulting in a communal experience.

—Genevieve Trainor

Syphilis in Iowa increased by more than 167% from 2019 to 2022.

Syphilis is a sexually transmissible infection (STI) that can cause long-term health problems. It’s serious, and cases are on the rise in Iowa. Not everyone who has syphilis has symptoms, so people often don’t realize they have it. That’s why it’s important for you to get tested regularly for STIs, including syphilis, if you’re sexually active.

Across

1. Top often paired with a cardigan, casually

5. “When was your last ___ smear?”

8. Opposite of fiction

12. Somewhat

13. One of many around the house for vinegar

14. Note for an oud?

15. Some memoirs

17. Corolla competitor

18. Character set?

21. Virtual date annoyance

22. Wicked relative?

24. Briefly offline?

25. TV shopping station whose letters stand for three attributes

26. Moses’s Obi-Wan Kenobi co-star

28. Done for

30. Monarchy with no permanent rivers: Abbr.

31. Judges

33. Character in a Strange

Planet comic

36. Montero rapper Lil ___ X

37. 2021 WNBA champs

39. Sponcon, e.g.

40. Rattles off

42. What a vest covers

44. Muscle that can be bounced, for short

45. Unsupervised

47. Rate zero stars, e.g.

51. Wheelchair basketball player and TV host Adepitan

64. Guinness offering

65. Card game with reverses

66. Just that time

67. Schlep

68. Ku or Kane, e.g.

69. Celebratory cheers

Down

1. Cows and bulls

2. Didn’t have time to cook, perhaps

3. Spanish port with ferries to Tangier

4. Fluffy rice cake

5. Throb

6. Query in many a ’90s chat room: Abbr.

7. 100 centavos

8. Stormtrooper shipped with Poe

9. Browses an estate sale, say

10. Travel company?

11. EDM subgenre

14. “Live with it”

16. The first one ever began handing out cash in a New York bank in 1969

17. Company that aptly anagrams to “a rest” announcements?

36. Compliment to a photographer or a tennis ace

38. Poet Harvey who contributed to Marvel’s World of Wakanda

40. Paved the way for

41. Didn’t release immediately

43. Tree that drops its cones during forest fires

44. Most scared at the haunted house, perhaps

46. Shaq’s alma mater

48. Like many a telenovela star

49. Free will

50. Doesn’t stay in one’s lane, say

52. Stonewall Inn demonstration

54. Ref. that added “burner phone” in 2022

57. Mötley ___ (band with a rare double gratuitous umlaut)

58. Self-satisfied

60. Gabriella’s boyfriend in High School Musical 63. Wahoo, at a sushi bar

52. Shares, as someone else’s post: Abbr.

53. “Without further ___ ...”

55. It’s shared by John Oliver and John Cena

56. Thick and delicious, as frosting

59. More soaked

61. Silkwood writer Nora

62. Item of color-changing jewelry found four times in this grid

20. Prefix with normative

23. Control tops?

27. Subjects of California’s Silenced No More act: Abbr.

29. Invite along for 32. Second part of “i.e.”

34. “The Ketchup

Song” group ___ Ketchup

35. Wedding

CUSTOMIZED LEGAL SERVICES POWERED BY