6 minute read

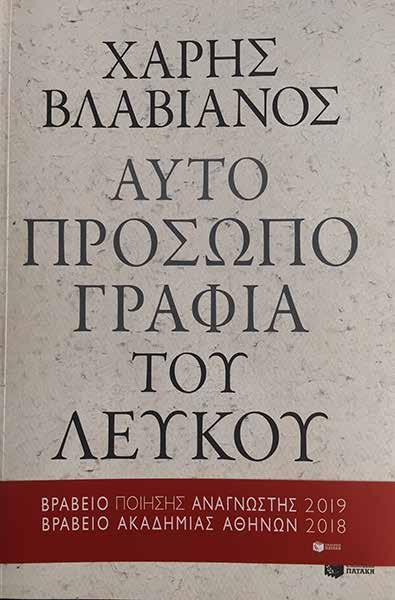

Hari Vlavianos, Self-Portrait of Whitness

Haris Vlavianos was born in Rome in 1957. He studied Economics and Philosophy at the University of Bristol (B.Sc) and Politics, History and International Relations (M.Phil, D.Phil) at the University of Oxford (Trinity College). His doctoral thesis entitled, Greece 1941-1949: From Resistance to Civil War, was published by Macmillan (1992) and was awarded the “Fafalios Foundation” Prize. He has published thirteen collections of poetry. He has translated the works of major poets such as, Whitman, Blake, Stevens, Pound, Eliot, Cummings, Ashbery and Carson. His translation of the Waste Land will be published at the end of May. He is the editor of the influential literary journal “Poetics” and Poetry Editor at “Patakis Publications”. He is Professor of History and Politics at the American College of Greece. He is at present teaching a post-graduate course in Creative Writing at the Greek Open University, as well as, at “Patakis”.

Advertisement

Red, Juicy Love

An apple next to a jug is yet another nature morte awaiting the brush of an experienced painter to come alive on his canvas. But an apple in the mouth of your beloved is “an entirely different story”, as Pater would have said. As you watch her sharp teeth sinking forcefully into its smooth body and then her tongue, slowly, with a circular motion, licking her lips still moist from the greedy contact, you do what the moment demands: With a lightning movement you snatch it from her mouth and you thrust it violently into your own only to return it to her a few seconds later – now reduced to half.

Isn’t that love? Aren’t those its signs?

Cycladic Idyll

Lower your eyes. When beauty invades your life with such force it can destroy you. The two ants hurrying along next to the soles of your feet are burying their summer dreams deep in the ground. The load they’re carrying isn’t going to crush them. They’ve measured their strength accurately.

Your shadow melts into the shade of the tree. Black on black. Guilt that must remain in the dark so as to go on defining you. But the glare of those fragments may still hold you. You have no need of adjectives. Of devious subterfuge. Every question is a desire. Every answer (you know by now) is a loss. Stay where you’re standing. In a while it will overtake you. The clouds don’t ask where. They just continue on their way.

Ode to Lost Meaning

To Anna Pataki

As you wander aimlessly through the exhibition spaces of the Tate, your gaze suddenly falls on a painting by an English artist. (His name and dates are beside the point.) On a wooden table he’s placed a bowl of fruit – apples and oranges – and next to them a water jug. (Nothing special. The subject has been familiar and trite since the time of the Flemish School, till Cézanne’s brush-strokes added an extra dimension to it.) To the left of the picture you read: “Still life with apples and oranges.” “Nature morte…” Where English sees life – an instant of it – (“don’t move please”) yours sees death, the slow decomposition of nature. (The word includes the painter who is now equally part of his composition.) A difference of temperament or of standpoint? Or is the standpoint perhaps defined by the temperament? Someone might argue that “nature morte” implies the possibility of rebirth, whereas “still life” presents life trapped in the motionlessness of a pose.

Someone. But you’re hungry now. You open your bag and pull out an apple. You hold it for a while in the palm of your hand. Under the smooth peel you feel its compact strength. As you prepare to take a secret bite (the guard’s not looking) you think: “How wonderful dead nature can sometimes be.”

Le Diable De Frivolité

Thank you for your message, but I didn’t feel like listening to it. As soon as you said “I’m drowning in regrets” I deleted it. Aren’t we a bit old for this unbearable melodrama? Besides, what kind of Bohème are you? Since you left (and you were right to) why did you come back with your tail between your legs? Only a romantic poet like Paraschos would seek out “a heart that has sinned”. Such naïve poets don’t exist any more. I have to admit though that the exchange of small-talk has its amusing side Yesterday I was reading a piece by Auden in which, among other things, he refers to a meeting he had with Stravinsky in California in November 1947. Do you know what the maestro called women like you? “Le diable de frivolité”! Isn’t that lovely? Neater than what other men would think in my situation. So, my little devil, I’ll leave you now (my battery’s running out) to devise your new plan. We’ll certainly meet at another of life’s operas (operettas more like). Love and kisses.

Bal Masqué

To Katerina

To write one line you first have to write another. To recite Shakespeare’s Sonnet VIII you first have to hear Catullus’ nightingale singing in your garden. To describe the shades of green on Cézanne’s apple you first have to snatch the palette out of Velasquez’ hands.

I know what it means to be in love: You dive head first into the sea from a rock, you touch the bottom, stroke the sand with your fingers and, watching the sun’s rays refracted in the water, you very slowly rise to the surface. When you pronounce her name you are already someone else.

Byron Shortly Before, Shortly After

“Who would write if he had something better to do?” said Byron to his Greek servant, as through the narrow window of his tumbledown house he watched the Ottoman hordes gathering round the city walls.

If thou regret’st thy Youth, why live? The land of honourable Death Is here:—up to the Field, and give Away thy breath!

Seek out—less often sought than found— A Soldier’s Grave, for thee the best; Then look around, and choose thy Ground, And take thy rest.

“On this day I complete my thirty- sixth year”, Missolonghi, 22 January 1824

He had just completed the first stanza of the poem that was destined to be his last. That day he had reached thirty-six. Three months later the bitterly divided foreign country that he had chosen for his homeland would grant him what he desired: a death worthy of his name, a heroic sortie from the unbearable boredom of Poesie.

Guillotine Maintenance

To Torsten Israel

And twenty years later, in the notorious Landsberg, the prison where in 1924 Hitler wrote his manifesto of hate, finding a convenient pretext in the antisemitic delirium of “the great philosophers of the nation”, – Kant, Fichte, Hegel –another philosopher, but not such a “patriotic” one, Kurt Huber, waited stoically in his cell for his turn to come. In the short time he had left he reread his beloved Leibnitz in an effort to understand the nature of evil – “that false note in the concert of life”. He had been found guilty of high treason because as a member of the secret “White Rose” organization he had helped Sophie Scholl and other students of his to write anti-Nazi proclamations that called on German youth to rise up against the “criminal regime”.

He was murdered on 13 July ’43. Two months later Klara Huber was visited by the Gestapo. They announced to her that as the wife of a traitor she was not entitled to receive his pension and that in addition she owed the German State two months’ wages – for “guillotine maintenance”.