18 minute read

Introduction

The idea for this book had been rummaging around in my head for some time before I eventually put thoughts into print. It often seemed to me that the task of connecting together all the relevant material was just too daunting and the natural progression of the narrative too depressing, so I almost shelved the whole idea several times. Then, I came to realise that I was misguidedly concentrating on outcomes (the death of three people whom I loved), when I should have been focusing on lives well-lived, before the vagaries of old age arrived with all its many challenges.

This is essentially a book about relationships. The content of these pages reflects moments of sadness, culpability, trust, acceptance and love within my own family, where old age took hold like ice crystals penetrating a pane of glass –each contrary pattern evolving at its own speed, direction and time. My father, mother and maternal aunt each succumbed to the frailties of old age in its different forms and this is my attempt to give an honest account of their stories in a way that will offer some insight into how families endeavour to cope. Sadly, dementia played a big part, which is something that can’t be ignored or swept under the carpet, and because there can be much sadness and emotional distress involved in any dementia journey, it is often difficult to unearth some of the more uplifting moments. However, those moments can and do exist, albeit fleetingly at times, and the transcripts of my mother’s and aunt’s childhood reminiscences are a reminder that such recollections are important and necessary when short-term memory has almost completely gone.

Some things are not easy to return to. Although in the past, I have used poetry and prose as a means of expressing my feelings about ageing, it was only when I re-visited the scrapbook, jotter and diary entries that make up a substantial part of this book, that I appreciated how difficult the writing of it would actually be. Yesterday’s truths laid bare in black and white evoked in me a huge sense of emotional guilt about what I could have done better. Yet, much of what happened within these family relationships I would not change, and if there is any meaning attached to what this book contains, it is to know that in times of great trials we can only do the best we can, and to hang on, as much as we are able, to what is good.

Lynda

Tavakoli May, 2024

Once

(a fictional short story *)

It’s quiet in this place. All I can hear are the bones of the dead whispering to me from the ruins of the poorhouse, whose fallen gable wall I can see easily from where I sit. The elements have done their work across the years, gorging out the integrity between bricks, eroding any history that has lain dormant in that now empty space of rooms; but that does not prevent me from remembering. No. Remembering has become my saviour and the lynchpin that protects my sanity, for the old (and I am indeed old now) are the lost of us and we, the lost, must cling to what we can in order to survive.

My mother brought me here when I was not much higher than her knee. The place was in the townland where she had been born and we were visiting, on foot, a poorly relative not long, I recall, for this world. We passed the old workhouse on the way, standing then as it is now, beside the banks of the Blackwater, whose eddies sucked the brown darkness into itself as though needing to justify the name. The building had, even then, been derelict for some time, although every wall was still intact and the roof saddled itself comfortably over any existing trusses. When we stopped, I could feel my mother’s softness squeezing my palm, her heartbeat pulsing at the tips of her fingers, her love for me like blood, coursing its way from one of us to the other. I raised my chin to look up at her, waiting for her words patiently, for she was apt to think long before offering them up, and shortly the reward came in a way that I could not have then expected.

“Listen,” she said, her lovely hazel eyes fixed upon my own. “Listen to them talking to us, Dora. Can you hear?”

I listened, pressing my ears out towards the surrounding space, as much to convince myself that I could share with her something I did not understand, but all I could hear was the river’s rush over rocks and a soft low of the cattle coming from a neighbouring field.

“No Mama,” I answered truthfully, knowing what she meant. “I don’t hear anything”.

She was standing now looking upwards toward the high row of windows that had long been blinded of glass, and to the chimney that shocked its way through the beleaguered roof.

Releasing the grip on my hand she pointed out towards them. “I always wondered about the children,” she told me, “and how they would have slept top and tail with one another, squeezed in rows. We’d see them on our way to school looking down at us with their bare eyes.” I could not envisage my own mother of an age so young as to be going to school but I nodded anyway. It seemed important that I allow her simply to utter the words.

“Afterwards, when it closed, a lot of them were buried over there,” she continued, nodding towards a thin copse of trees on the far bank of the river, “in Bully’s Acre.” And with that, from her mouth came such a sigh as could have saddened even a stone’s heart. “Our family was never so poor as to not be able to look after each other,” she added.

It is strange the things we choose to remember. And those things, too, that we decide to forget. As I sit here now in this quiet, lonely place recalling my mother’s words and looking out upon the ruined workhouse, I feel the presence of those children so intensely it sends a shiver through my heart. Perhaps it is the curse of old age to carry with you the burdens that you could not suffer as a child but there is no guilt to it, nor should there be. What was before has now become the present and foolishness lies only in failing to learn a lesson from the past. I hope I have the wit left in me still to believe it.

Today I wait in this new building that they like to call a ‘home’. Although they built it near the original site, it is as far from a workhouse as any place could ever be, with its white-walled sterility and state of the art facilities for the elderly infirm. No one but me can know the irony of the circle I have travelled to arrive back here, but I take comfort in the memory of the in-between, regardless of the regrets and sorrows on the way. A car scrunches up on the gravel outside and I see that my own daughter has come to visit, something I treasure, although it is she who put me here. It was a deed done not with belligerence but with a genuine desire to do what was right, yet knowing this does not give either of us the comfort that it should. I ought to be at home where I can heal myself with the familiar, but I will not ask for it as a rebuttal will only pain us both.

She comes in smiling, but behind those green eyes is a look of abandonment impossible to conceal. It is not for herself but for me and I do not know how to respond to it except to welcome the warmth of her embrace as easily as I succoured her when she was a child. The others here stare over and a woman nearby weeps suddenly without restraint, the white spit from her open mouth fizzing as it settles on the carpet near her feet.

My daughter moves quickly with a tissue to mop up the mess stroking the woman’s hand as she moves away and I am touched by this small act of kindliness towards a stranger which was neither asked for nor expected. Then she returns to sit on the arm of my chair saying, “I hear they have a cat like yours here mummy. They’ll let you stroke it sometime, if that’s what you’d like.” But I don’t like. It will only serve to make me miss my own PussPuss more than I already do.

“It’s okay,” I lie. “I’m not that fond of cats really.”

Through the window a sky of washed-out blue is troubled only by the smoky contrail of a passing jet. It triggers a memory of the Spitfire pilot who wooed me during the war; dashing and arrogant in equal measure and quite a catch for a farm girl such as me. Yet it was a sweeter, gentler and much poorer beau I eventually chose and the half century that we were wed somehow proved my judgement true.

“Let’s take a walk outside, mummy.” It’s my daughter again, gathering up my belongings and taking my elbow to prise me from the chair. How tired these old bones have become from just the sitting and looking; but I do not resist. It will actually be a relief to feel air that has not been tainted by age like an overly- matured and vile smelling cheese, so I allow myself to be led to my room and collect my coat. At the main door we wait to be allowed out, another irony when I think of all the post-it notes the family stuck up around my own home. Bright orange and yellow stickers issuing little warnings such as: Don’t forget to lock the door! Don’t let anyone in mum unless you know them! Now they’d prefer that I just didn’t escape.

The fresh air helps me to feel a bit more like myself. I enjoy the slow walk down past the workhouse (although I do not allow myself to look this time) and over the bridge to where there is a plaque hung rustily on an old gate. It reads: ‘Bully’s Acre. The burial place of the poor of the district - in memory of those within.’ We have read those words many times, my daughter and I, but in truth every time is like the first for me and it is now almost too much for me to bear.

“I’m done,” I say simply, squeezing my daughter’s hand and feeling the warm pressure that returns it. I try not to show that I know she is crying. We walk on further until the silver birches shade out completely any rays of the diminishing sun, and stop where the moss under our feet ensures that any footfall will remain undetected. I like the idea of it; this spongy bed where once they have softly fallen, those folk whose kin could not look after them.

“Can you hear them?” I ask, knowing by the look in my daughter’s face that she does not. No, she cannot hear the voices yet. But she will. She will.

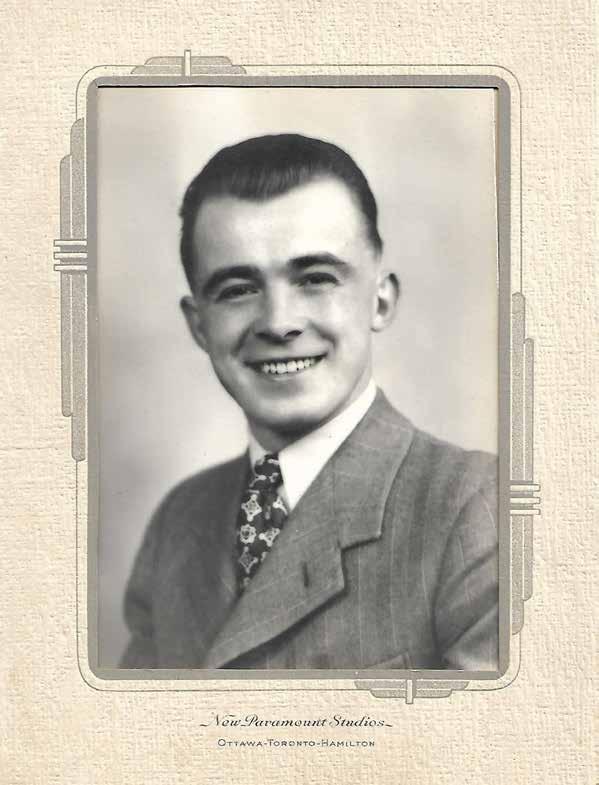

Daddy (Harry), 1948.

‘Father, you are the bendy beech, drawn from a Fermanagh bog, a sapling twisting your resistance into a foreign home where I transported you, just to have your presence close. At your feet a boot of snowdrops kicks the winter into spring, and from your branches, fingertips of bud await a summer’s touch before they flare. And when I listen, cheek pressed close against the roughness of your bark, I hear the rising sap of who you are speaking to me through the quiet earth.’

From the poem ‘Garden’ in ‘The Boiling Point for Jam’, a poetry collection by Arlen House.

Daddy (Harry)

My father was a man of immense kindness and integrity but I did not appreciate the importance of these qualities until well into adulthood myself. I was a difficult teenager, angst-ridden and self-pitying for most of the time, and I didn’t try very hard at anything in school, except for playing sport. Looking back on it, both my parents showed a level of tolerance and lenience towards me that I never should have expected.

Dad rarely spoke about his own childhood, growing up as the youngest of ten children on the island of Inishmore, between Upper and Lower Lough Erne. By all accounts, life was very tough and there was little opportunity to further his education beyond the age of 14, which is when I believe dad left school. Later, during the war years while working as a policeman, he inadvertently met my mother, whom he stopped for not having a light on her bicycle. Their ‘going together’ continued until dad decided to follow some of his elder siblings out to Canada, but he returned eventually to marry mum, and they remained in Northern Ireland from that time onwards. All in all, they were married for almost half a century.

Although, as a family, we lived in the sizeable town of Portadown from Monday to Friday, weekends were spent back at the home farm on Inishmore, the place I came to realise, that shaped much of my subsequent writing. After dad’s retirement, he and mum continued to spend a lot of time there; the nurturing comfort of nature’s endurance giving them a continued purpose for their journey into old age. Sadly, it was short-lived, as dad succumbed to multi-infarct dementia, and his life as he put it to me once, was ‘torn asunder’.

My Father’s Hands

My father would take an axe and cut in just the right spot, until, with one touch of his finger, he could fell the whole tree. He would spend hours polishing horse-brasses and all our shoes, before arranging them in regiments beside the back door. The day he went for tests I watched him stop to smooth the dog; his hands were butterflies.

Jean James (my sister)

Dementia and my family

It’s impossible to pinpoint the moment my father began to suffer from dementia. Nobody in the family questioned any momentary lapses of memory from time to time and even when these became more frequent, I don’t think any of us really understood the significance of what was happening. Certainly, that word dementia was far from our thoughts at that stage.

When dad retired, he and mum had gone to live in a small Fermanagh village close to where dad had been brought up, the youngest in a family of ten children. He had a great love of the countryside and took delight in taking walks with Daisy his collie dog, happily passing the time of day with anyone who had a mind to. Fermanagh was often wet and cold but he was content to have gone back to his roots. It was his idea of what a retirement should be - living in a place he loved, with someone he loved, and having the time to enjoy it. Sadly, his contentment was short lived.

The first time I ever heard the word dementia mentioned in relation to my father was when he was hospitalised after a TIA (Transient Ischaemic Attack). As a lay person I was unfamiliar with the medical jargon but quickly realised that dad had suffered a mini stroke. He was to suffer more in the course of his illness. It seemed that the problem stemmed from the carotid artery being ‘furred up’ and restricting the blood supply to the brain. The neurologist told me that aside from this, my dad’s brain was shrinking and there was little they could do about it. Then that word – dementia.

People joke about it. Remarks about dotty old aunts going cuckoo and being and being demented are all commonplace. It’s always easy to mock when something doesn’t affect you personally. I don’t find it that funny anymore.

When dad returned home from the hospital, he understood the explanations that had been given to him by the medical profession. At the time neither he, nor us, had any idea about how the disease would progress. Mum and dad had been married for nearly fifty years and had always had a loving relationship built on mutual trust and respect. I can’t recall ever witnessing them having an argument. But gradually you could see that mum was doing that little bit more for dad and he was becoming that bit more reliant on her. You could tell that the balance of their relationship was changing.

I had always found in my own life, that during a crisis I coped better if I educated myself about the matter in hand. When I was diagnosed with cancer I selectively read many books on the subject and it helped me enormously during and after my treatment. It was no different with my father’s illness.

I learned, surprisingly, that dementia comes in different forms. Alzheimer’s is the most well-known but there are others, like multi-infarct dementia, which is what dad had. Instead of a gradual decline in his health, the illness progressed in a stepwise fashion which, to me anyway, was the cruellest blow of all. With each downward step dad seemed to have an awareness of what was happening, which was tragically the loss of that bright and alert mind of his.

My mum coped so well for so long. Like many carers she just got on with the job of looking after someone she loved. She never complained, although I’m sure there were times when she could easily have given up. But as the months went by and dad’s condition accelerated, the emotional and physical toll on my mother became increasingly obvious. Ultimately it became impossible for her to cope and decisions had to be made about the future. With the help of Social Services dad was accepted into a special unit for Elderly Mentally Infirm patients (EMI) in Lisnaskea. It was the most wonderful caring place where dad would receive both kindness and compassion in equal measure. The staff in any old people’s home has its work cut out for them and not everyone could do their job. I don’t think I could.

Dad was a genuinely good person all his life and even though he had a disease that affected his mind, he always remained considerate and polite. When I visited him, he would inevitably greet me with a smile and the staff would always remark on how kind and co-operative he was. The EMI unit itself was a clean, no-frills sort of place which, above all, was a completely safe environment for its residents. In my dad’s simple room with a bed, chair and a few personal items strewn about, I realised more and more how little material things really matter. It would have made not one button of difference had the surroundings been plush, extravagant and expensive. What mattered most was the compassion that painted the walls, not the decor.

Gradually dad began to go further and further away from us. They say that you can tell a lot from someone’s eyes and it’s true because when I looked into my father’s eyes he wasn’t always there anymore. I did not realise it then, but now I believe that this was the point I began to grieve for my father, and that feeling of having already lost someone when they are still alive is hard to come to terms with.

For me visits were becoming more and more distressing. I did not enjoy seeing so many other poor souls in the unit living in that same mental prison that had also incarcerated my father.

It was a stressful and difficult time and I was torn between wanting my father to stay alive and wanting him to pass away so that his suffering would be over. It is something that perhaps many people think but do not freely admit to. Realistically though, I knew that dad had actually been lost to us several years before when senile dementia had first taken its hold upon his mind.

Daddy died several years ago now and I miss him still. But having witnessed the debacle that occurred in care homes across the country during the corona virus pandemic, I’m relieved that he did not survive to experience such injustices and indignities himself. Where has our humanity disappeared to when the elderly (with or without dementia) are treated like they are an afterthought? So many families are suffering with the aftermath and all I can hope for is that they find some kind of comfort in knowing that their departed loved ones are themselves now, at least, at peace.