Welcome to tonight’s tribute concert to Sir Harrison Birtwistle.

No doubt many of you here tonight will have your own stories of when you first were changed by Harry’s music. My first encounters with it came while studying music at university in London in the 1980s when I attended performances in the Queen Elizabeth Hall of Down by the Greenwood Side, Yan Tan Tethera and Bow Down. Up to that point I did not have much sense of my own cultural identity, compared to that projected by England’s Celtic neighbours, but his music gave me a strong feeling of earthy, raw and ancient traditions that I instantly connected with. Soon after I took part in an ENO Baylis Programme project exploring The Mask of Orpheus and was taken deeper into his world.

Much later, in this job, I have had the honour of meeting and working with musical icons, but none more so than Harry. My first visit to his home after starting at the London Sinfonietta began with a typically gentle provocation, as with a straight face he asked me ‘Well, you going to change the name then?’. Even though we haven’t (of course), I became instantly aware that, nearly 40 years into the history of the Ensemble, Harry rightly assumed his relationship with it – his importance to it, and its importance to him. So, this programme book rather unashamedly celebrates that special relationship, and the tributes at the back are from some of the players and those connected to the Ensemble involved in preparing and staging the projects we performed.

Anyone doing this job will always cherish the joy of commissioning new work, so I’ll always remain proud of several commissions with Harry. Early in my time in this role was a planning meeting in the offices of Boosey & Hawkes with Harry, Janis Susskind (his publisher) and the extraordinary Enzo Restagno, the artistic director of the MITO festival which was staging a significant eight-concert retrospective of Harry’s work in Milan and Turin. For the London Sinfonietta, this was a huge booking – from a concert staging of The Last Supper through the ensemble and chamber works. And I was able to join with Enzo in committing London Sinfonietta to co-commission In Broken Images. Around the same time, I was organising the 40th anniversary concert for the Ensemble in 2008, and Harry responded with a small but powerful duet The Message (formally a trio with the short side-drum contribution at the end) which he then spontaneously added to with four more duets over the coming years, culminating in our last commission Five Lessons in a Frame in 2016. Several of you in the audience tonight have contributed to realising his commissions or recordings of his music. You deserve our thanks and I have no doubt you will cherish your association with those pieces and his musical tradition.

The Message was inspired by an art work by Bob Law inscribed with the words ‘The purpose of life is to pass the message on’. I hope that in this side-by-side project with students from the Royal Academy of Music (and in the many times we have used his music in our own summer London Sinfonietta training Academy), that we are passing the message of Birtwistle’s music on to future generations of players and conductors as well as to audiences. So, I’m grateful to the Royal Academy of Music for their collaboration tonight, to Londinium for joining us and to Martyn Brabbins for leading us. And thanks to the Southbank Centre where we are Resident, who have been a partner and venue is so many of the works by Harry which we have had the honour to premiere and perform.

The London Sinfonietta’s history has evolved through the influence of different conductors, artistic directors, players, staff and Council members. The organisation has responded to the changing world of contemporary culture, becoming ever more eclectic and often leading the way in its collaborations with other music genres and art forms. But always there from the beginning has been Harry. With recent changes in public funding policy we now face the challenge to evolve again for the sake of our long-term future. I’m sure that, along with all the innovation and transformation required ahead, remembering Harry’s certainty and commitment to the music and ideas he was quietly passionate about will help us sustain a tradition that is so worth caring about.

ANDREW BURKE CHIEF EXECUTIVE & ARTISTIC DIRECTORWe’re the largest arts centre in the UK and one of the nation’s top visitor attractions, showcasing the world’s most exciting artists at our venues in the heart of London. We’re here to present great cultural experiences that bring people together, and open up the arts to everyone.

The Southbank Centre is made up of the Royal Festival Hall, Queen Elizabeth Hall, Purcell Room, Hayward Gallery, National Poetry Library and Arts Council Collection. We’re one of London’s favourite meeting spots, with lots of free events and places to relax, eat and shop next to the Thames.

We hope you enjoy your visit. If you need any information or help, please ask a member of staff. You can also write to us at Southbank Centre, Belvedere Road, London SE1 8XX, or email hello@ southbankcentre.co.uk

Subscribers to our email updates are the first to hear about new events, offers and competitions. Just head to our website to sign up.

We are delighted that you are here with us to share in our tribute to Sir Harrison Birtwistle.

As becomes so evident reading through the memories and reflections in the rest of this programme, the 50+ years’ history of the London Sinfonietta is inextricably and proudly linked to this giant of contemporary classical music. This evening’s programme can give only a hint of his creative output, but we hope that it will illustrate how his work became an inspiration for so many performers and continues to be a reference point for many of today’s aspiring composers.

I would like to thank very much all those who have come together to make this occasion, as well as the supporters of the London Sinfonietta who enabled us to commission and perform Harry’s work from those

early years onwards – it is easy to forget how such international figures start their careers experimenting and developing their techniques with little public recognition and a bit of risk-taking on all sides. My personal sadness is that my own closer association with the London Sinfonietta didn’t overlap more with his, but his pieces will continue to be a foundational part of our story.

“COMPOSING WAS NEVER A JOB FOR HIM. IT WAS HIS VERY BEING. MUSIC JUST KEPT FLOWING FROM HIS MIND AND OUT OF HIS FINGERS, WITH INCREASING PRODUCTIVITY AS THE YEARS WENT BY.”

Sunday 5 March 2023

Southbank Centre’s Queen Elizabeth Hall

Sir Harrison Birtwistle

Duet 1 (The Message) (2008, London Sinfonietta commission)

Virelai (Sus une fontayne) (2008)

Verses for Ensembles (1969, London Sinfonietta commission)

Interval

The Fields of Sorrow (1972)

In Broken Images (2011, London Sinfonietta co-commission)

Martyn Brabbins conductor

Abigail Sinclair soprano

Lisa Dafydd soprano

Londinium (Choir Director Andrew Griffiths)

Royal Academy of Music Manson Ensemble

London Sinfonietta

The London Sinfonietta is grateful to Arts Council England for its support of the ensemble, as well as the many other individuals, trusts and businesses who enable us to realise our ambitions. This event is produced by the London Sinfonietta, and is supported by The Marchus Trust with the friendly support of the Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation. The work of the London Sinfonietta is supported by Arts Council England and the John Ellerman Foundation. London Sinfonietta is grateful to the Birtwistle family for providing the photos used throughout this programme.

It took more than three decades for Sir Harrison Birtwistle’s landmark opera The Mask of Orpheus to receive its second full staging. Many, like me, who had been present at its premiere in 1986, were changed by it. It opened up extraordinary new worlds. While the 2019 production by Daniel Kramer for English National Opera divided audiences and critics, there was unanimity on the power and originality of the musical experience. When the octogenarian Birtwistle and his librettist Peter Zinovieff came to take their curtain call on the opening night, the entire house rose to its feet. This was fitting. It was as if Birtwistle’s work had come full circle, from its roots in 1960s experimentalism when the embryonic ideas for the piece began to take shape, now to appeal afresh to a new, young public not even born when the opera had first been seen in that very same London theatre. It was, quite simply, thrilling to observe a new generation finding its own way into Birtwistle’s music and being enthused by it.

The Mask of Orpheus could never be described as an ‘easy’ work. Its ambition is vast, rich, combining singing, text, theatre, mime, a huge orchestra, electronics, and an intricate musical vocabulary that presents not a linear narrative but rather a central idea from multiple perspectives. Modernist. Uncompromising. These might be considered more appropriate words. And yet somehow it still manages to speak directly, not abandoning operatic forms, but rather rethinking their lyrical conventions for the late 20th century. This is what struck me so powerfully when re-encountering the work in 2019: for all its structural complexity, I was left with the image of Orpheus as an ordinary individual, overcome by grief, lamenting the woman he had lost, who finds his life no longer supportable. And this seems to be the secret of so much of Birtwistle’s music: always challenging, yet always essentially clear and simple in the way it articulates the essence of human experience.

Directness was a facet of the man as well as of the music. Born and raised in Accrington, Harry – as he was universally known – retained throughout his life not just a soft, lilting Lancastrian accent but also a

certain Northern straightforwardness. He knew what he wanted. And he just got on with it. (Beneath the gruff façade, however, there was a gentle, humorous man, who enjoyed sharing the simple pleasures of his garden and kitchen.) His earliest surviving piece, written when he was a teenager, is for piano and is called The Ookooing Bird. Its essential simplicity, its repeating structure, its interest both in the mythical and natural worlds, are all also defining facets of his mature work. It is almost as if he emerged fully formed as a composer, his later compositions being just a working out of these ideas on larger canvases and in new contexts. The beautiful The Moth Requiem (2012) for twelve female singers, three harps and alto flute, for example, is cut from the same cloth and speaks with the same melancholic voice. So many of his works were shaped and coloured by his early musical experiences in the North of England, playing as a clarinettist in a military band and in an amateur opera company’s pit orchestra. Sounds of wind and brass instruments dominate his earlier music (even The Mask of Orpheus has no string section); he relished writing for north-country brass bands in Grimethorpe Aria and Salford Toccata; and he drew on northern folk tales for his music theatre works Bow Down and Yan Tan Tethera. Elsewhere, the craggy landscapes of his childhood re-emerge, most notably in his magnificent orchestral work Earth Dances

He entered the Royal Manchester College of Music in the early 1950s as a clarinettist. And it was there he made the connections that were crucial for his later development as a composer. Composer Peter Maxwell

“…BIRTWISTLE’S MUSIC: ALWAYS CHALLENGING, YET ALWAYS ESSENTIALLY CLEAR AND SIMPLE IN THE WAY IT ARTICULATES THE ESSENCE OF HUMAN EXPERIENCE.”

Davies, pianist John Ogdon and trumpeter Elgar

Howarth were all fellow students. So too was composer Alexander Goehr, son of Schoenberg pupil Walter Goehr, who acted as a conduit not only for the work of the great continental figures of the early 20th century but also for the latest music coming out of Paris and Darmstadt. Together they founded the New Music Manchester group in order to explore these works, as well as to premiere their own. In fact, Birtwistle emerged from his compositional chrysalis relatively late, completing his ‘opus 1’, Refrains and Choruses, at the end of 1957, which was subsequently selected by the Society for the Promotion of New Music for performance at the 1959 Cheltenham Festival.

Birtwistle’s music first caught wide critical attention in the 1960s. The sounds he was making in works like Tragoedia and Verses for Ensembles were bold and exciting. He won a scholarship to study in the USA and it was there he completed his ‘tragical comedy or comical tragedy’, Punch and Judy, premiered at the Aldeburgh Festival in 1969, and which went on to be performed many hundreds of times all over the world. Stylised, ritualised, aggressive violence tempered by a reflective lyricism, it announced a composer not only with a distinctive musical voice but also one completely at ease in the theatre. After a formative period spent working as Music Director at the National Theatre – including making the outstanding music for Peter Hall’s production of Tony Harrison’s northern dialect translation of Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy – he went on to write a prodigious series of operas that continued to explore mythological subject-matter: Gawain and The Minotaur for the Royal Opera House, The Second Mrs Kong and The Last Supper for Glyndebourne, and the smaller-scale The Io Passion, The Corridor and The Cure for Aldeburgh. Layered narratives and repeating structures remain a feature of all these works, but also increasingly a focus on character, as well as a more direct kind of lyricism. The hard edges of Punch and Judy were smoothed away somewhat, to reveal a new concern for expression, often of a darkly melancholic kind. Even when Orpheus was not the actual subject of a work, his lamenting voice was still palpable.

This dark melancholy also found its way into his instrumental music. The dawn of the new millennium saw another landmark work for large orchestra, The Shadow of Night, taking its inspiration from various 16th-century melancholic sources, followed by its companion piece Night’s Black Bird, and the equally monumental Deep Time. This lattermost work reveals another longstanding preoccupation of the composer

– going back at least as far as The Triumph of Time (1971–72) – with time and its articulation, not just across the duration of the pieces themselves, but conjuring up a sense of the sublime when confronted with vast, slowly changing, geological processes.

In recent years, in between fulfilling these large-scale commissions, Birtwistle demonstrated the more intimate aspects of his compositional identity. Often working alongside particular players, he produced an important body of chamber works that have found a

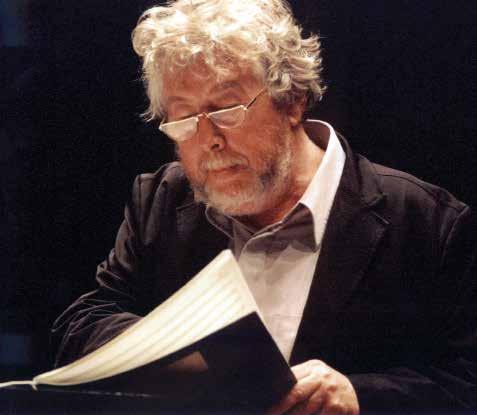

“IN RECENT YEARS, IN BETWEEN FULFILLING THESE LARGE-SCALE COMMISSIONS, BIRTWISTLE DEMONSTRATED THE MORE INTIMATE ASPECTS OF HIS COMPOSITIONAL IDENTITY.”Birtwistle in the Queen Elizabeth Hall

regular place in the concert hall. His 26 Orpheus Elegies, for example, settings of Rilke for a typical Birtwistle combination of oboe, harp and countertenor, are beautifully poignant; Songs for the same Earth for tenor and piano bring to his friend David Harsent’s poetry gentle and evocative resonances; the Bogenstrich pieces for cello and piano resulted from a close exploration of the string instrument’s musical and expressive possibilities with Adrian Brendel.

In later decades Harrison Birtwistle became a figure of international standing. Major festivals in Europe, Asia and America featured his work. Commissions came from far and wide, and noted conductors were keen to programme his work, including Barenboim, Boulez, Eötvös and Rattle. He won important prizes – most notably the Grawemeyer Award and Siemens Prize – and received countless honours, among them a Knighthood, the Companion of Honour, and Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. Yet, for him, such success was essentially incidental. What mattered most was the daily routine of disappearing off to his shed (a version of which followed him wherever he lived) to put notes on paper. He once expressed utter surprise when someone asked him when he was going to retire. ‘I just don’t think he understood what I do’, was his bewildered response when later relating the encounter. Composing was never a job for him. It was his very being. Music just kept flowing from his mind and out of his fingers, with increasing productivity as the years went by. Once he had produced enough material for one piece, he would draw a double bar, and then start immediately on the next. In a sense it was this focus, this singlemindedness, that gave his music its unmistakable identity. He composed for himself, not for others. What anyone else thought of his music (aside from those

performing it) was of little consequence to him. Even when his music caused uproar, as the premiere of Panic at the 1995 Proms notoriously did, he was never especially bothered. There was certainly something naughtily provocative about that particular piece, intruding into the polite silliness of the ‘Last Night’; but equally, having been commissioned to write for the occasion, he could hardly have produced anything different. He knew what he wanted, and he simply did what he did. Pan, embodied in Panic’s solo saxophone, was – like Orpheus, like the Green Knight, like the Minotaur – just another of those mythical creatures with which Birtwistle became obsessed, and through which he was able to articulate deep ideas about time and identity, longing and loss. This is the essence of the music of Harrison Birtwistle, and the source of its power. This will be its enduring legacy. And it is to this music we shall return time and again to continue to mine its immense riches.

Duet 1 is a conversation for two instruments. The original title, The Message, derives from a sculpture (see page 21) by Bob Law on which is inscribed ‘the purpose of life is to pass the message on’.

Sir Harrison Birtwistle created the first short piece The Message (Duet 1) for the London Sinfonietta in 2008, as a ‘birthday card’ for their 40th anniversary concert. He then decided to write four more duets for different occasions over the coming years, dedicated to colleagues and supporters of his music. The pieces in the sequence were finally united in one work commissioned by the London Sinfonietta entitled Five Lessons in a Frame, which had its world premiere in 2016.

© Andrew Burke Chief Executive & Artistic Director, London SinfoniettaVirelai (Sus une fontayne) was written for twelve instrumentalists of the London Sinfonietta, who gave its first performance under Elgar Howarth at the Turin Conservatoire on 6 September 2008.

The piece is a realisation of a virelai by Johannes Ciconia, who flourished in the second half of the 14th century, around the time Chaucer was writing his Canterbury Tales. He seems to have been born around 1335 in Liège, but spent much of his life in Avignon and Northern Italy, dying in 1411. A virelai is a type of song common during the 14th century consisting of alternating refrains and stanzas.

Reprinted by kind permission of Joanna MacGregor and Bath Festivals

In Verses for Ensembles, written to a commission from the London Sinfonietta in the winter of 1968-69, Birtwistle exploited the verse-and-refrain concept with greater brilliance and virtuosity than ever before. The ensembles of the title are families of instruments – a quintet of woodwind, a brass quintet and percussion. Throughout the work the groups either operate as units or soloistically; an instrument detaches itself from the ensemble and assumes an independent role, in the process articulating the verse-and-refrain structure of the entire work, a scheme in which the discrete blocks of material may be baldly juxtaposed or overlaid, but never homogenised into a continuous whole.

The tensions created by this method of construction are enormous, and it seems as if the instruments become embroiled in a ritual of mysterious power. It is an early example of the ‘secret theatre’ that was to become increasingly characteristic of Birtwistle’s later output. There is a visual element to the work also, which enhances the feeling of arcane ceremony: the instrumental groups are arrayed on the stage in symmetrical ranks, the higher woodwind to the left, their lower siblings to the right, the brass in a row above them, while the percussion – pitched and unpitched – rise in rows above that. Around the periphery of the ensembles are four solo positions: the two on raised platforms at the rear of the playing area are used exclusively by the trumpets; the two at the very front are shared at various moments in the work by the trumpets, horn or woodwind. It is the migrations of the players between these positions that provide their own map of the work, providing a visual image of linear movement which the music itself seems to do its best to deny.

© Andrew ClementsThe Fields of Sorrow was commissioned for the Dartington Summer School of Music in 1971. It is an expressive and evocative work scored for two solo sopranos, chorus, and a sixteen-piece chamber ensemble featuring two pianos. The text is a highly pictorial poem by the fourth-century poet Ausonius. The score is a beautifully printed quarto of 19 pages that are a visual delight. Sparse, atmospheric scoring, coupled with printing that blocks out the rests and silences, results in many pages that exhibit more open white space than area covered by staves and notes.

For the most part, precise, conventional notation predominates, although there are moments in which some choices, exist for the instruments and moments in which aleatory and prescribed activity occur simultaneously. The composer demonstrates a preference for half-step dissonances and octaves that quietly become ninths. The prevailing mood is both quiet and hypnotic: most of the dynamic markings are softer than pianissimo. The inevitable calm of the final moments emerges from a gradual movement from slightly jagged rhythms and asymmetrical meters toward a plodding, repetitive texture that soothes by insistence. Throughout, the feeling is one of awe and mystery, reflecting the images of the poem – silent lakes and streams, and ageing flowers.

Undoubtedly this is a work that could have great psychological impact when performed well, and a score worthy of its place in libraries.

© Jackson HillHarrison Birtwistle’s In Broken Images took as its starting point the music of Giovanni Gabrieli with its interplay between groups of instruments, but rather than emulating the Venetian composer’s use of echo effects and ritornelli, Birtwistle’s work tracks an independent path in which the music is in a permanent state of exposition. The wind, brass and strings are fiercely independent demonstrating distinct identities, while the percussion underpins each musical family providing the continuum. The fragmented multiplicity of events in Birtwistle’s work is only fully clarified for a single bar, near the end, when the groups play the same music. Otherwise, there is a calculated non-synchronisation of the blocks of material using a hocket technique. After completing the score, the composer recognised that the moment of unity offered an analogy to the Risorgimento: “It wasn’t a conscious thing when I was composing to mirror the political situation but there is a similar moment of coming together. Just as in Italy, though, the different identities continue with each retaining its own distinct ‘cuisine’.”

In Broken Images was co-commissioned by Enzo Restagno, Artistic Director of MITO SettembreMusica International Music Festival and the London Sinfonietta to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Unity of Italy.

© Boosey & HawkesThe Fields of Sorrow: texts and translations

Errantes silve in magna et sub luce maligna inter harundineasque comas gravidumque papaver et tacitus sine labe lacos, sine murmure rivos, quorum per ripas nebuloso lumina marcent fleti, olim regum et puerorum nomina, flores

Ausonius

They wander in deep woods, in mournful light, Amid long reeds and drowsy-headed poppies, And lakes where no wave laps, and voiceless streams, Upon whose banks in the dim light grow old Flowers that were once bewailed names of kings.

Translated by Helen Waddell

Martyn Brabbins is Music Director of the English National Opera. An inspirational force in British music, he has had a busy opera career since his early days at the Kirov and more recently at La Scala, the Bayerische Staatsoper, and regularly in Lyon, Amsterdam, Frankfurt and Antwerp. He guests with top international orchestras such as the Royal Concertgebouw, San Francisco Symphony, DSO Berlin and Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony, as well as the Philharmonia, BBC Symphony and most of the other leading UK orchestras. He is a popular figure at the BBC Proms, who in 2019 commissioned 14 living composers to write a birthday tribute to him. Known for his advocacy of British composers, he has conducted hundreds of world premieres across the globe. He has recorded nearly 150 CDs to date, including prize-winning discs of operas by Korngold, Birtwistle and Harvey.

He was Associate Principal Conductor of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra 1994-2005, Principal Guest Conductor of the Royal Flemish Philharmonic 2009-15, Chief Conductor of the Nagoya Philharmonic 2012-16, and Artistic Director of the Cheltenham International Festival of Music 2005-07. He is Prince Consort Professor of Conducting at the Royal College of Music, Visiting Professor at the Royal Scottish Conservatoire and Artistic Advisor to the Huddersfield Choral Society alongside his duties at ENO, and has for many years supported professional, student and amateur music-making at the highest level in the UK.

Londinium, directed by Andrew Griffiths, is one of London’s most versatile and accomplished nonprofessional chamber choirs, particularly noted for vibrant performances of a cappella repertoire. Founded in 2005, the choir has established a strong reputation for diverse, imaginative and eclectic programming across the centuries with an emphasis on unjustly neglected or rarely performed works, particularly of the 20th century. It is also committed to contemporary music, and has given a number of premiere performances. Londinium’s debut CD of 20th-century English choral music, The Gluepot Connection, released by SOMM Recordings in 2018, was a MusicWeb International Recording of the Year (‘probably my favourite disc of the year’) and praised in Gramophone (‘impressive accomplishment and no mean flair’). The choir recently recorded a disc of choral music by Kenneth Leighton, including the premiere recording of his superb but unpublished major work, Laudes Animantium, for release by SOMM in May 2023.

Londinium performers:

Sophia Anderton

Mike Bolton

Katie Boot

Aubrey Botsford

Fiona Clark

Steve Copeland

Eleanor Cranmer

Simon Funnell

Molly Goetzee

David Henderson

Trevor Heywood

Sophie Hopkins

Peter Johnson

Hilary Lawson

Chris Lemar

Yvonne Light

Chau-Yee Lo

Clare Loosley

Niels Lous

John McLeod

Hazel Mehta

Lucy Myers

António Sá-Dantas

Alison Shiers

Helen Statham

David Stocks

Rebecca Swaine

Chris Swithinbank

Julian Tolan

Michael Tomkins

Grace Vaughan

Maurice Wren

ANDREW GRIFFITHS combines his role as Head Coach & Music Consultant at the National Opera Studio with a busy freelance career in the worlds of opera and choral music.

A former Jette Parker Young Artist at The Royal Opera, he has conducted productions for The Royal Opera (Linbury Theatre), The Royal Ballet, Welsh National Opera, Opera North, Opera Theatre Company, Opera Collective Ireland, Early Opera Company, Mid Wales Opera, Bampton Classical Opera and Iford Opera, and worked as an assistant conductor at Royal Opera House, Glyndebourne, English National Opera, Scottish Opera, Chicago Opera Theatre, and with the BBC Symphony Orchestra. Concert work includes appearances with the Royal Northern Sinfonia, Orchestra of the Swan, Southbank Sinfonia and Orpheus Sinfonia. Andrew frequently broadcasts and records with the BBC Singers, he is Musical Director of Kingston Choral Society and Londinium, regularly conducts for Dartington, and has appeared with the BBC Symphony Chorus, New London Chamber Choir, and Hong Kong’s Tallis Vocalis. He also sings as a member of vocal consort Stile Antico.

Elissavet Archontidi-Tsaldaraki violin

Laura Cooper viola

Niccolò Citrani cello

Ieva Kupreviciute flute/piccolo

Da Som Jeong flute

Fergus McCready oboe/cor anglais

Rebecca Whitehouse oboe/cor anglais

Ivan Rogachev clarinet/bass clarinet

Leo Kerr clarinet/bass clarinet

Bethany Crouch clarinet/contrabass clarinet

Heidi Walliman bassoon/contrabassoon

Sophia Smaditch bassoon

John Vernon trumpet/piccolo trumpet

Jasmin Ghera trumpet

Samuel Dawes trombone

James Owen trombone

Matthew Brett percussion

Timothy Rumsey piano

The Manson Ensemble is the Royal Academy of Music’s specialist contemporary music ensemble. Its first concert was at the Aldeburgh Festival in 1968, and it plays regularly at the Academy and in festivals around the UK. Since its foundation, the ensemble has collaborated with composers including Berio, Boulez and Messiaen in the early days and, more recently, Hans Abrahamsen, Eleanor Alberga, Tansy Davies, Andrew Norman and Anna Thorvaldsdottir.

Other highlights include performing and recording the music of Frank Zappa as part of a Roundhouse/ Zappa Family Trust festival and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s Beyond the Score – A Pierre Dream with Susanna Mälkki at the Aldeburgh Festival. CD recordings include Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale, conducted by Oliver Knussen and with George Benjamin, Harrison Birtwistle and Harriet Walter narrating.

Since 2002, the Manson Ensemble has undertaken a major series of Side by Side projects with the London Sinfonietta, including the UK premiere of Nono’s Prometeo, and performances of Stockhausen’s Gruppen, Hymnen and Donnerstag aus Licht, and Thomas Adès’s In Seven Days at the Royal Festival Hall.

Canadian soprano Abigail Sinclair recently graduated with a Bachelors in Vocal Performance from the University of Toronto where she was a member of their Undergraduate Opera Program. This past Autumn, she began her Masters in Vocal Performance at the Royal Academy of Music under the instruction of Vocal Studies Head, Kate Paterson.

Since joining the Academy, she has been accepted into their prestigious Bach Consort, and will perform the role of Mademoiselle Silberklang from Der Schauspieldirektor in the Academy’s Summer Opera scenes this May.

Part of her practice involves collaboration with emerging composers to create and promote new works. This past Summer, Abigail participated in SongFest in San Francisco where she was selected to premiere the 2022 Sorel Commission – a chamber piece titled Love, Loss and Exile by American composer Juhi Bansal.

Highlights of the 2021/22 season included an Encouragement Award in the Metropolitan Opera Laffont Competition’s Buffalo/Toronto District, and a recital focussing on the depiction of female characters throughout music history with pianist Ria Kim for the Banff Centre’s inaugural EvoFest: Evolution Concert Series.

Abigail is grateful for the support of the Sylva Gelber Music Foundation, the Royal Academy of Music and the Nova Scotia Talent Trust.

Welsh soprano Lisa Dafydd is currently a Masters student at the Royal Academy of Music under the guidance of her tutors, Mary Nelson and Iain Ledingham.

Most recently, Lisa had the opportunity to work alongside the soprano and conductor Barbara Hannigan as a soloist in a concert alongside students from The Juilliard School, performing Delage’s Quatre poèmes hindous.

In September 2022, Lisa performed in the world premiere of Gelert, an opera by Paul Mealor, in which she played one of the lead roles, Siwan. She also participated in an evening of opera scenes with the Royal Academy Opera, playing the roles of Norina in Donizetti’s Don Pasquale, Dalinda in Ariodante by Handel, and Second Niece in Britten’s Peter Grimes

In the most recent National Eisteddfod of Wales, Lisa was awarded the highly prestigious Osborne Roberts Blue Riband Memorial Award and the Violet Mary Lewis Scholarship for the most promising soprano. As part of her prize, she will be travelling to the USA this summer to sing in the North American Festival of Wales.

The London Sinfonietta is one of the world’s leading contemporary music ensembles. Formed in 1968, our commitment to making new music has seen us commission over 450 works and premiere many hundreds more. Resident at the Southbank Centre and Artistic Associate at Kings Place, with a busy touring schedule across the UK and abroad, the London Sinfonietta’s Principal Players are some of the finest musicians in the world.

Our ethos is to experiment constantly with the art form, working with the world’s best composers, performers and artists, collaborating with young people, communities and the public to produce music projects often involving film, theatre, dance and art. We are committed to challenging audience perceptions by commissioning work which addresses issues in today’s society, including work that has tackled climate change, violence towards women and racial inequality. We also work closely with the audience as creators, performers and curators of the events we stage. We

Michael Cox flute/piccolo/alto flute

Gareth Hulse* oboe/cor anglais

Mark van de Wiel* E flat & B flat clarinet/bass clarinet

Timothy Lines clarinet/bass clarinet

Graham Hobbs bassoon/ contrabassoon

Timothy Ellis horn

work with schools and communities across the UK supporting and encouraging their musical creativity, while our annual London Sinfonietta Academy is an unparalleled opportunity for young performers and conductors to train for their future in the profession with our Principal Players.

The London Sinfonietta has also broken new ground by launching its own new digital Channel, featuring video programmes and podcasts about new music. We created Steve Reich’s Clapping Music App for iPhone, iPad and iPod Touch, a participatory rhythm game that has been downloaded over 600,000 times worldwide. The back catalogue of recordings of the Ensemble over 50 years has help cement its worldwide reputation. More recent recordings include George Benjamin’s opera Into the Little Hill (Nimbus), Benet Casablancas’ The Art of Ensemble (Sony Classical), David Lang’s Writing on Water (Cantaloupe Music) Philip Venables’ debut album Below the Belt (NMC) and Marius Neset’s Viaduct (ACT). londonsinfonietta.org.uk

Christian Barraclough trumpet

Ruby Orlowska trumpet

Byron Fulcher* trombone

Ruth Molins trombone

Alexandra Wood violin

Elizabeth Wexler violin

Paul Silverthorne* viola

Zoe Matthews viola

Sally Pendlebury cello

Cecilia Bignall cello

Enno Senft* double bass

Andrew Zolinsky piano

David Hockings* percussion

Joe Richards percussion

Heledd Gwynant percussion

The second half of tonight’s programme includes a Side by Side performance with students from the Royal Academy of Music. The Academy and London Sinfonietta have been working together since 2002, providing young artists with performance experience in a professional setting. This evening’s performance is especially poignant, as Harrison Birtwistle was an alum who had a life-long relationship with the Academy. (See Academy Principal Jonathan Freeman-Attwood’s remembrance of Birtwistle on p30.)

The Royal Academy of Music moves music forward by inspiring successive generations of musicians to connect, collaborate and create. It is the meeting point between the traditions of the past and the talent of the future, seeking out and supporting the musicians today whose music will move the world tomorrow.

From pre-school to post-doc, students come from more than 60 countries to hone their craft. They are challenged to find their own voice, take risks and push boundaries. Simon Rattle, Felicity Lott, Elton John, Edward Gardner, Evelyn Glennie and Jacob Collier all learnt their craft at the Academy.

Students benefit from a stimulating curriculum and an ambitious range of concerts, events and record producing. Legendary artists come to the Academy not just to perform, but to become mentors, friends and musical partners. As it enters its third century, the Academy’s aim is to shape the future of music by discovering and supporting talent wherever it exists.

Founded in 1822, the Royal Academy of Music is the oldest conservatoire in the UK and the second oldest in the world.

Professional Side by Side projects play a unique and indispensable role in high-level musical training at the Academy. They function effectively as artistic work-placements, giving students the experience of rehearsing and performing in a completely professional context. The projects bring multiple benefits, allowing students to exercise their musical skills in an environment that mirrors the industry, to gain a greater understanding of world-class collaborative music making, and learn about professional expectations across many different creative arenas.

At the heart of the Side by Side experience is the mentorship provided by professional partners, which is a key stepping stone from the educational dynamics of one-to-one lessons to the autonomous responsibilities that go with membership of a prestigious ensemble. The projects enable students to develop professional networks and to significantly enhance their long-term employability.

London Sinfonietta was the first organisation to work with the Academy on a Side by Side project in 2002. Partners now also include London Philharmonic Orchestra, Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Knussen Chamber Orchestra, Academy of Ancient Music and CHROMA.

Find out more at www.ram.ac.uk

Kate Molleson: What was the first piece of Birtwistle you heard, Jonathan?

Jonathan Cross: I can remember it vividly. It was a recording. It was in fact the first piece Birtwistle wrote for the Sinfonietta, Verses for Ensembles, on the wonderful Decca ‘Headline’ label – it had that cover with Birtwistle’s head and his big hair echoing outwards like you were looking at him in a kaleidoscope! It was a friend who said, ‘Do you know any Birtwistle?’ And I replied, ‘Who?’ ‘Listen to this!’, he said.

KM: Who was this excellent friend?

JC: David Allenby, who later became Birtwistle’s publisher at Boosey & Hawkes! We both explored this music together. I’d

have been 18 or 19. It blew me away. In a sense I was looking for music like this that was different: bold, brash. It was its sound world, its energy, the way it moved in and out of the violent and the lyrical that appealed. It suggested a new way of organising music. I also loved the idea of its theatre. And I said to myself, I need to find out more about this.

And how about you Kate? What was the first piece you heard?

KM: This is a happy coincidence as it was also a London Sinfonietta recording. It was Carmen Arcadiae Mechanicae Perpetuum, that disc that also has Secret Theatre and Silbury Air on it. I was at McGill University in Montreal studying music. I was part of their contemporary music ensemble as

a clarinettist, which was brilliant but didn’t have anything to do with British contemporary music. We explored French musical connections, the American new music scene, as well as improvisation, which is really alive in Quebec.

JC: So how did Birtwistle fit with that?

KM: It was a fellow clarinettist who was curious about British new music. I was embarrassed as I didn’t know very much. ‘But what about Birtwistle?’ he said, and he played me Carmen. I suppose it was rather nostalgic for me because I was away from home and figuring out how I felt about being British. That moment framed my subsequent experiences of Birtwistle. I really

‘I THINK PERHAPS YOU’RE RIGHT: IN PUBLIC HE GAVE PEOPLE WHAT THEY EXPECTED OF A COMPOSER.’

liked what I heard: its earthiness, the soil, a sort of fibrousness, jaggedness. It reminded me of Bartók whom I’ve always loved deeply, not smoothing out the rough edges. And – as you said about Verses – hearing the theatre in it. It struck me as an ancient ritual. I’ve always loved myths and the rugged, rustic sense of theatre that ended up being essential to Birtwistle.

JC: It’s interesting, isn’t it, because Verses and Carmen are quite similar in many respects.

KM: Yes. And it’s fascinating what sticks. A very wise grandmother figure told me that when you meet the person who’s going to become really important to you, you know instantly what you’re going to love and what you’re going to hate about them. And it seemed to work the same for me with Birtwistle.

JC: Do you think you responded to this music as a clarinettist too?

KM: Yes, there’s something about the way he writes for instruments that’s very tactile: the

percussiveness, the physicality. I like the graininess of the clarinet and Birtwistle understands that.

JC: That’s what I like about his music too, its roughness. I remember once talking to him about Francis Bacon. He said he loved those flashes of colour on a Bacon canvas, occasional seemingly random brush strokes, which don’t belong yet at the same time do! There’s a kind of roughness there that spoke to Birtwistle. And I can hear that in the music too: sudden flashes of sound that burst out from somewhere unexpected.

KM: It adds a flamboyance, a grandness. I like it that the grubbiness and the grandeur can coexist.

JC: Yes, that grandness, those works on the large scale. You know just from the opening bars of a piece like Earth Dances that you’re in for a long ride. There’s not an obvious logic to the way the ideas unfold, and yet there’s a rightness about it when listening. You recognise you’re dealing with

very slow time – a music working in eons rather than minutes!

KM: How do you think his music will be viewed in a hundred years’ time?

JC: He was often asked that. And he would retort, ‘What’s the weather going to be like next week? I don’t know.’ Which is really the only right answer. He was composing for today not tomorrow. But it’s also true that many composers do drop off the radar when they die. That certainly happened with Tippett, didn’t it, though there’s renewed interest in him now.

KM: It raises the question of how much a composer’s status has to do with the establishment around them, the publishing networks and so on that are crucial in terms of sustaining them while they’re alive. Does that vanish with them?

JC: And in Birtwistle’s case having advocates like the London Sinfonietta programming his music was a great advantage. I’ve chatted to some of the long-standing

Sinfonietta players, people like violinist Joan Atherton and pianist John Constable, who were around for so much of the history of the Sinfonietta, and who speak very fondly about certain composers, Birtwistle among them. They loved playing his music. Responding to the challenges and the physicality of what they’re asked to do. John also speaks about Birtwistle as a composer who was on their side. He was very much a player’s composer, and that may be one of the reasons why the Sinfonietta worked with him so often – mutual respect.

KM: They both arrived on the scene together. The Sinfonietta was founded in 1968. I see parallels with young composers now who are working closely with certain ensembles and whose fortunes are growing together: Edmund Finnis and the Manchester Collective, Oliver Leith and Explore Ensemble, Cassandra Miller and the Bozzini Quartet. It’s a kind of symbiosis that was true for the Sinfonietta and Birtwistle too.

JC: Despite this, it’s surprising that his music hasn’t travelled so well, especially the operas. Take The Mask of Orpheus, his landmark work. It’s only ever had two productions in the same London theatre more than 30 years apart. Is there something peculiarly ‘British’ about Birtwistle’s music that makes it difficult to cross frontiers?

KM: Well, how many British composers have crossed those frontiers? Bachtrack recently published a survey of the top 10 living composers performed across the world in classical music concerts in 2022, and it’s fascinating to see three Brits among them: Thomas Adès, Anna Clyne and James MacMillan. What is it about these composers that makes them so playable? And how do their fortunes change? How is that, say, Vaughan Williams has become so beloved and untouchable in his status as a sort of icon of Englishness, and is it even fair? Wistfulness and stoicism and wholeness, the closeness to the land …

JC: … which clearly wasn’t true of the man! It’s the myth that’s grown up around him.

KM: Exactly. A pre-industrial Arcadia. Maybe it would be fairer to pin some of those things on Birtwistle?

JC: In many ways, of course, Harrison Birtwistle and Ralph Vaughan Williams are parallels: in touch with the landscape, English rituals and folk tales. Even when Birtwistle takes a more ‘universal’ tale like the Orpheus story he turns it into something very English.

KM: But it would require people to accept a very brutal kind of Englishness?

JC: Yes. The pastoral is not necessarily all fluffy sheep and fa-la-las.

KM: The violence of Punch and Judy and the mud under the fingernails. But what did ‘Englishness’ mean to him?

JC: I don’t know. I never spoke to him directly about that. Clearly a sense of place was important to him but that didn’t mean the big urban centres. He lived on the Isle of Raasay, in the heart of rural France, and then in Wiltshire.

KM: He had a persona that seems to chime with a self-image or caricature of Englishness, of Northernness, that is quite endearing: the doleful Lancastrian. I wonder how much that is wrapped up in people’s understanding of his place?

JC: I really admired that in him, someone who was from the ‘periphery’ rather than the ‘centre’. This wasn’t a London-based figure who’d been to an exclusive private school. He retained a regional accent throughout his life and didn’t really seem to care what people thought of what he did. Did he cultivate this gruff, Northern exterior? He’s never smiling in publicity photos. But in real life he grinned a lot, he told silly stories, and he loved good food and wine. I think perhaps you’re right: in public he gave people what they expected of a composer.

KM: He would always claim that what he did was simple, and that his methods were basic: always writing the same piece, just plotting a different route through the material. I found it hard to get through that claim of simplicity because when you listen to his

‘HE HAD A PERSONA THAT SEEMS TO CHIME WITH A SELF-IMAGE OR CARICATURE OF ENGLISHNESS, OF NORTHERNNESS, THAT IS QUITE ENDEARING…’

music it’s not true. I wonder if what will endure are the elements that first connected us both to his music – the rituals, the theatre, the earthy, the arcane, the things that feel much more ancient than they are?

JC: What we look for – and I hesitate to use this word – in ‘great’ art is surely something that takes us out of the mundane, out of our quotidian habits, and puts us somewhere else. And in the case of Birtwistle it’s that being in touch with what went before you and what comes afterwards. For me it’s like being in a vast mountain landscape where you sense your insignificance, physically and temporally, amidst something that’s been around for millennia. And there’s also the melancholic aspect to his music. He recognised this in himself, and it explains one of his obsessions: ‘Orpheus was a melancholic, and so am I’, he once said. That’s why he kept returning to him. With Birtwistle it’s like looking at the world in the half-light. I hear that in some of the more recent chamber music or the Moth Requiem. These are powerful melancholic works in the same way Dowland and late Schubert are. It puts you in touch with something beyond yourself that’s hard to articulate.

KM: Like Night’s Black Bird

JC: The Shadow of Night too.

KM: His returning continually to the figure of Orpheus is fascinating because Orpheus is no hero, is he? This is not a kind of hero complex. There’s a failure built into the way he treats his character, his foolishness, and the repeated obsession with screwing up every time.

‘I WONDER IF WHAT WILL ENDURE ARE THE ELEMENTS THAT FIRST CONNECTED US BOTH TO HIS MUSIC – THE RITUALS, THE THEATRE, THE EARTHY, THE ARCANE…?’Birtwistle in his studio in Wiltshire in 1997

JC: That’s true. Orpheus, Punch, the Minotaur, they’re all the same.

KM: His representation of maleness is a flawed one, then: damaged figures.

JC: Is he just looking in the mirror?

KM: Maybe! Didn’t he say that about keeping coming back to Orpheus? Because he shows us our own failings. It reminds me of a brilliant version of the Odyssey by Emily Wilson, the first woman to translate the Ancient Greek text into English. She speaks about why the translations that went before her would take for granted certain accepted versions of words that really change the way we understand the story. She translates the very first line not as ‘Goddess of song, teach me the story of a hero’ (as in the Oxford World Classics version) but rather ‘Tell me about a complicated man’. And so immediately she sets up both Odysseus and his journey as problematic. I understand Birtwistle’s Orpheus obsession in a similar way.

JC: Yes, Birtwistle doesn’t seem to see outside himself. Gawain sings in the eponymous opera, ‘I’m not that hero’, and in a sense, Birtwistle too is saying ‘I’m not that hero’, I’m not the heroic composer-figure you want me to be. I’m actually just working through issues for myself, time and again. That was what was so striking about Fiona Maddocks’s book about him, which gave a very different view of the composer: composing was difficult, a struggle.

KM: The fact that he allowed that book to be written was brave, because it also showed his vulnerabilities and uncertainties. Where’s our hero now?

JC: Heroic, no, but do you think Birtwistle was a radical? He was pushing at boundaries, but in many other ways he worked with familiar structures such as recitatives and arias, certain conventional kinds of theatrical representation, the relationship between music and text, and so on. Whereas many younger composers today are doing completely different things. They’ve moved beyond what we might call ‘high modernism’.

KM: It’s like Picasso: everything he touched was radical, but what he was touching was traditional stuff like paint and paper. He made it radical in the same way Birtwistle does with rhythm and repetition, and the tactile nature of an instrument, and a player just walking across the stage.

I’ve been thinking about Annea Lockwood, who was in England at the same time in the 1960s. She talked about making music in radical ways in part because she felt an outsider: as a New

Zealander, as a woman, she didn’t belong in the corridors of power. The infrastructure was so difficult to navigate, there was no point writing big orchestral pieces. She just went and did her own thing – burying pianos in the garden, and things like that. She adopted radicalism of necessity. Whereas Birtwistle didn’t ever seem to have to make those kinds of choices.

JC: And where does Birtwistle sit among the composers who remain with us? I’ve been immersing myself recently in Saariaho’s music, who has also become an established voice but in a different kind of tradition. Her music doesn’t sound at all like Birtwistle’s, yet they share that balancing of the radical – their sound worlds – and the conventional – their attitudes to nature.

KM: Yes, as we said earlier, using familiar materials to make us listen differently. The way that Saariaho uses technology is not about being radical; it’s about extending what’s possible.

JC: And in Birtwistle’s case he did what he did simply by means of the conventional 12-note scale, hidden away in his shed at the bottom of the garden, with the aid of the oldfashioned technology of a 2B pencil and a stack of manuscript paper. The alchemy of turning the ordinary into the extraordinary.

Jonathan Cross is Professor of Musicology at the University of Oxford, and author of Harrison Birtwistle: Man, Mind, Music (Faber, 2000)

Kate Molleson is a journalist and broadcaster, and author of Sound Within Sound (Faber, 2022)

‘IT’S LIKE PICASSO: EVERYTHING HE TOUCHED WAS RADICAL, BUT WHAT HE WAS TOUCHING WAS TRADITIONAL STUFF LIKE PAINT AND PAPER.’

12 Feb 1969

Queen Elizabeth Hall (QEH), London Verses for Ensembles

• World premiere & LS commission

• Conductor –David Atherton

26 Feb 1971

QEH, London Meridian

• World premiere & LS commission

• Conductor –David Atherton

18 Apr 1971

Oxford Prologue

• World premiere

9 Mar 1977

QEH, London Silbury Air

• World Premiere & LS commission

• Conductor –Elgar Howarth

24 Jan 1978

QEH, London Carmen Arcadiae Mechanicum Perpetuum

• World premiere

• Conductor –Harrison Birtwistle

4 Apr 1980

QEH, London Mercures (poses Plastiques)

• World premiere & LS co-commission

18 Oct 1984

QEH, London Secret Theatre and Songs by Myself

• World premiere & LS commission

• Conductor –David Atherton

1 Aug 1986

QEH, London Yan Tan Tethera

• World premiere

• Conductor –Elgar Howarth

24 Jan 1988

Royal Festival Hall (RFH), London

Four Songs of Autumn

• World premiere & LS commission

4 May 1988

QEH, London An die Musik

• World premiere

• Conductor –Harrison Birtwistle

6 May 1990

Royal Opera House, London Ritual Fragment

• World premiere & LS commission

19 Jun 1991

Snape Maltings, UK

Four Poems by Jaan Kaplinski

• World premiere

• Conductor –Harrison Birtwistle

26 Apr 1996

QEH, London Slow Frieze, for piano and ensemble

• World Premiere & LS commission

• Conductor –Markus Stenz

5 May 1996

QEH, London Bach Measures

• World Premiere

• Conductor –Diego Masson

22 May 1999

QEH, London The Silk House Antiphonies

• World premiere

• Conductor –Oliver Knussen

11 May 2000

Tate Modern, London

17 Tate Riffs

• World premiere

• Conductor –Martyn Brabbins

• The Queen was present 14 Oct 2000

QEH, London Slow Frieze

• World Premiere of new version

• Conductor –Martyn Brabbins

2 Dec 2003

QEH, London Theseus Game

• UK Premiere & LS commission

6 Sep 2008

Turin Conservatoire, Italy

Virelai

• World Premiere

12 Jun 2009

QEH, London Semper Downland and The Corridor

05 Sep 2011

Teatro Dal Verme, Turin, Italy

In Broken Images

• World premiere & LS commission

12 Jun 2015

Snape Maltings The Cure

• World premiere & LS co-commission

18 Jun 2005

Snape Maltings Neruda Madigales

• World Premiere & LS co-commission

• Conductor –Nicholas Kok

• Conductor –Pierre-Andre Valade 11 Jun 2007

RFH, London Cortège

• World premiere

• Conductor –Elgar Howarth

2 Dec 2008

QEH, London The Message (Duet 1)

• World Premiere & LS Commission

• World premiere

• Conductor – Ryan Wigglesworth

25 Nov 2009

The Warehouse, London Bourdon (Duet 2)

• World premiere & LS commission

20 Aug 2011

Cadogan Hall, London Angel Fighter

• UK premiere

• Conductor –David Atherton

• Conductor –David Atherton

5 Dec 2014

QEH, London Violute (Duet 4) & Echo (Duet 5)

• World premiere & LS co-commission

• Conductor –Geoffrey Paterson

2016

St John’s Smith Square, London

Five Lessons in a Frame

• World premiere & LS co-commission

• Conductor –Martyn Brabbins

THERE HAVE ONLY BEEN TWO YEARS IN OUR HISTORY WHERE WE HAVE NOT PLAYED BIRTWISTLE: – 1968

(THE YEAR WE WERE FOUNDED)

– 1993

Spain (4 performances)

Portugal (4 performances)

Canada (4 performances)

Mexico (3 performances)

Finland (3 performances)

Australia (3 performances)

Argentina (3 performances)

Russia (2 performances)

Slovakia (1 performance)

Norway (1 performance)

Hungary (1 performance)

Greece (1 performance)

Denmark (1 performance)

Czech Republic (1 performance)

Croatia (1 performance)

China (1 performance)

Belgium (1 performance)

Armenia (1 performance)

6 USA

8 NETHERLANDS

14 FRANCE

Silbury Air 9 Mar 1977

Carmen Arcadiae Mechanicae Perpetuum 24 Jan 1978

Mercure – Poses plastiques 4 Apr 1980

Secret Theatre 18 Oct 1984

Songs by Myself 18 Oct 1984

Four Songs of Autumn 24 Jan 1988

Ritual Fragment 6 May 1990

Slow Frieze 26 Apr 1996

Bach Measures 4 May 1996

Theseus Game 19 Sep 2003

244 UK 20 GERMANY

55 ITALY

5 SWEDEN

8 POLAND

8 AUSTRIA 6 JAPAN

WE HAVE PERFORMED BIRTWISTLE IN 28 COUNTRIES

Neruda Madrigales 18 Jun 2005

The Message (Duet 1) 2 Dec 2008

Bourdon (Duet 2) 25 Nov 2009

Duet 3 9 Sep 2010

In Broken Images 5 Sep 2011

Duet 4 (Violute) 5 Dec 2014

Duet 5 (Echo) 5 Dec 2014

The Cure (partner piece to The Corridor) 1 Jun 2015

5 Lessons in a Frame 1 Jun 2016

This list includes co-commissions with other ensembles and organisations

Dylan Thomas

Dylan Thomas

HB’s ancestors can be clearly traced back for centuries, having all been firmly rooted in the vicinity of Huncoat, a small town just outside Accrington. At the age of seventeen, Harry’s father, Fred, joined the East Lancashire Regiment, enduring the Gallipoli campaign and the horrors of trench warfare in Northern France. At some point in the 1920s, his mother, Madge (née Harrison), was sent at an early age to live with her uncle who ran the post office in Hampton Hill. Coincidentally, this was just a stone’s throw from where the three of us were eventually to grow up in Twickenham.

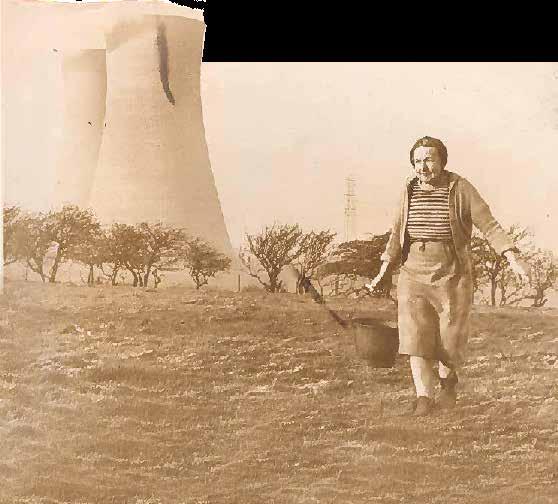

Some years after Fred and Madge married, they decided to leave the industrial landscape and confined terraces of Oswaldtwistle, where they ran a bakery, to become farmers. Their only child, Harry, was about seven years old when they moved, and for him it was a hugely significant moment. His new surroundings were a pastoral idyll. Remembering that time, he had fond memories of his dog, “Urk” (Hercules), and a pony named Bobby, and he spoke of hummingbirds, butterflies, corncrakes and woodpeckers. There was a small reservoir full of fish that fed a brook through a wooded valley, leading to the remains of ‘Hapton castle’, (originally bequeathed to an old ancestor, Reyner de Birtwistle, by King John in 1209). Once there was a small hamlet called Birtwistle, which had long disappeared, but amazingly has recently been found. HB got to know his new playground intimately, and often mentioned the hiding places he found when playing truant from school.

At some point in the early 1950s, industrialisation started creeping closer to this Arcadia, most dramatically when two enormous cooling towers were built almost in the next field. It would be easy to over-romanticise all of this and to speculate what effect, if any, it had on the art of HB. Nonetheless, he often described his music as landscapes that were punctuated with unexpected objects, or intruders, just like the cooling towers, and just to sprinkle the tale with some fairydust, he also mentioned to us that the small valley he could disappear in as a sort private playground, was in fact the reason why he wrote music.

Adam, Silas, Toby Birtwistle

Sir Harrison Birtwistle’s sons

Adam, Silas, Toby Birtwistle

Sir Harrison Birtwistle’s sons

It was an immense honour to be able to call Harry a close friend and professional colleague; it’s therefore with the deepest regret that I’m unable to be with you all this evening to celebrate the remarkable relationship between Harry and the Sinfonietta, a symbiotic association that endured and prospered for more than half a century.

Both fairly blunt-speaking Lancastrians, some of our formative years were spent playing clarinet together in the Lancashire County Youth Orchestra, he a budding professional, I…well, as Tony Pay once remarked, “although a good technician, (he) never really learnt how to blow it properly”!

Our paths would cross again when, at Cambridge University, I directed Harry’s Tragoedia, a fabulous early trial balloon for his opera Punch and Judy, the first performance of which I conducted with the phenomenal English Opera Group at the Aldeburgh Festival in 1968. During eight weeks of incredibly intense rehearsals for Punch, Harry and I “clicked”, his precocious genius infecting everyone around him. His sardonic humour, laced with affection and a deadpan smile, masked a deeply serious composer who knew exactly what he wanted and was often justifiably irritable when we fell short. Back in the 60s stories abounded of his discontented experiences working with large symphony orchestras who found the complexities of his music too much to comprehend, and the technical demands too outrageous. At Aldeburgh, with a long rehearsal period in an idyllic setting and with a small-knit group of singers, players and a production team headed by my great friend, the late Paul Findlay, a founding director of the Sinfonietta, we were able to forge a focused, intense ‘family’ spirit.

Five months earlier Nicholas Snowman’s and my baby, the Sinfonietta, was born, its inaugural concert containing the premiere of John Tavener’s The Whale. John’s work and the Sinfonietta’s formation created quite a stir amongst the national press; this intrigued Harry. I asked him if he’d consider writing a new work, promising a similar ‘family’ spirit to the one we were experiencing at Aldeburgh. My suggestions: no restrictions on orchestration, a substantial work that would be the programme’s main focus and a showcase for instrumental virtuosity. The result, a masterpiece: Verses for Ensembles, an exceptionally influential work that was undoubtedly the major highlight of the Sinfonietta’s second season and the centrepiece of this evening’s concert.

Much, much more was to follow Verses; it became the first in a long line of commissions from the Sinfonietta, and the beginning of an astonishing partnership that would last a lifetime.

My friend Harry was inspiring, yet unforgiving; plentiful with praise whilst being enormously critical; and, above all, showed his genuine gratitude to everyone involved despite never appearing completely satisfied. What a privilege it has been to be trusted and involved with so many wonderful creations. Harry, we miss you.

David Atherton obe Conductor & co-founder of the London SinfoniettaIn recent weeks much has been written by many of us concerning Harry, the extraordinary, amazingly original and vital composer. In addition to these thoughts and tributes I have personally been recalling the sheer pleasure and rich experiences of being with Harry on visits abroad.

I was privileged to be invited by Harry in recent years to accompany him to Porto and Berlin on the occasion of performances of his works. In the wonderful Casa da Música designed by Rem Koolhaas, Ryan Wigglesworth and the Orquestra Nacional do Porto gave wonderful performances of Night’s Black Bird and our evenings in that lovely city would end up with Harry, Ryan and myself relishing malt whisky and memorable conversations and friendship.

An equally relaxed and delightful Harry was present in Berlin where Robin Ticciati also memorably conducted Night’s Black Bird.

In the 1980s Margo and I had accompanied Harry and Sheila to a remarkable Ring cycle in Bayreuth led by Daniel Barenboim and Harry Kupfer. Relatively recently, a propos of nothing, Harry suggested we return to Bayreuth, on this occasion for a distinctly bizarre production of the Ring but which was wonderfully conducted by Kirill Petrenko to whom Harry was introduced by Eva Wagner. I remember Harry’s surprise at meeting a jean clad, youthful quite diminutive figure emerging from the celebrated pit.

I hope the photos give some idea of the happy, relaxed atmosphere Harry on tour always created.

Ifirst met Harry in 1968 when the London Sinfonietta invited him to write a substantial piece for whatever instruments he wanted to employ. The work that emerged was Verses for Ensembles, the first of many memorable pieces that Harry wrote for the Sinfonietta over subsequent decades. Verses turned out to be a masterwork and very challenging technically. David Atherton, a stickler for quality, quite rightly specified that only top players should be engaged, and he understandably required numerous sectional and tutti rehearsals to do the piece justice. In those days it took much longer for musicians to master the difficulties such complex contemporary scores presented.

At the time, David, Nicholas Snowman, Tony Pay and I shared a small house in north London, the hub from where things were organised. It was a kind of cottage industry. I remember there was no heating in the house, so as much time as possible was spent planning the concerts at Luigi’s, a local Italian restaurant where a decent three-course set menu cost ten and six. Most of the musicians on David’s list played for different London orchestras, so it was quite a problem to organise the rehearsals around the players’ limited availability. For this purpose, we made use of an early form of manual spreadsheet which indicated the times and dates when each player was free. The schedule was finally agreed upon and the concert took place on 12 February 1969 to much acclaim. As I recall, the players on that occasion included Judith Pearce (flute), Derek Wickens (oboe), Antony Pay (clarinet), Martin Gatt (bassoon), Barry Tuckwell (horn), Elgar Howarth (trumpet), John Iveson (trombone), and the cream of London’s percussion fraternity. Fortunately for us, these accomplished musicians were keen to work with David and to master the problems involved. The result was a magnificent performance of this exciting and exacting composition.

We had a lot of fun in those early days, even though we were never quite sure how things would turn out. After more than 50 years of concert giving by the Sinfonietta, I guess they turned out all right, not least thanks to the many outstanding works written for the group by Harry and other major figures.

Andrew Rosner

Harrison Birtwistle’s long-serving manager

Harry’s music and creative life are inextricably and joyously connected to the London Sinfonietta. To perform an evening of the great man’s music together is both inspiring and humbling.

When I reflect on the many Birtwistle Conducting journeys I have experienced, I realise that they have actually been veritable expeditions of discovery, not mere journeys. Often with no road map, and certainly nothing akin to a pocket guide!

Such expeditions are serious undertakings. Each piece I have worked on has certainly shared characteristic Birtwistle fingerprints, but at the same time, these shared traits are far outweighed by the sense of creative renewal and exploration that this most original of composers presents. Embarking on a Birtwistle expedition perhaps compares to a mountaineer preparing to tackle an unconquered peak. And if the preparation is inadequate or doesn’t embrace a sense of discovery, then, given the challenges of unmarked routes and awkward terrain, the summit will prove elusive.

Harry’s connection with the Academy began with his short period of postgraduate study as a clarinet student in the late 1950s. The association wasn’t seamless: after decades when his involvement was minimal – in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s – we then witnessed a sudden and remarkable surge of teaching, workshops, mentoring, concerts, recordings and collaborations from 1995 until his death. Harry also offered peerless advice to the institution, particularly when the Academy was moving from a place where contemporary music was neatly packaged in a series of annual festivals (admittedly with some stunning results with the likes of Ligeti, Berio, Henze and Messiaen in situ) to being part of the mainstream and our ‘daily bread’.

As ever with his visiting teaching role, Harry always visibly entered the building ‘glass half empty’: ‘I haven’t a clue what I’m going to say to this lot. How you compose is one of the things you can’t really talk about.’ You could tell he didn’t completely believe that. It was a conceit of grim granite we learned to adore, a default against the danger of over buttering the parsnips. Two hours later Harry had opened the eyes, ears and minds of a group of composers, not so much in practical guidance to their own creative muse, but more what it meant to be an artist and how the observation of life and living has to be at the heart of every note penned. He raised the stakes to the point at which students realised that for all the professional challenges of being a composer, the vocation was a deeply serious matter for the human spirit.

It just happened that Harry’s emergence coincided with the founding of the Academy’s record label and the first task was for Sebastian Bell, Head of Woodwind and long of this London Sinfonietta parish, and me, to produce a disc including Harry’s first piece (composed at the Academy) Refrains and Choruses, as well as Grimethorpe Aria and, soon after, with our Head of Brass John Wallace, a recording of the world-premiere Tate Riffs, composed for the opening of Tate Modern.

‘I HAVEN’T A CLUE WHAT I’M GOING TO SAY TO THIS LOT. HOW YOU COMPOSE IS ONE OF THE THINGS YOU CAN’T REALLY TALK ABOUT.’

I have been fortunate to conduct several of Harry’s operas, most recently The Last Supper in 2018, and The Mask of Orpheus in 2019. The Last Supper was in Glasgow with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra and a wonderful cast headed up by Roddy Williams. Unforgettable was the day I spent filming an interview with Harry at the Silk House. His thoughts and ideas were eloquently and inimitably expressed, and he was a generous and welcoming host. Harry’s magnificent quince tree took a starring role in the film, and the jelly I made from the fruit Harry gave me was divine!

I was so proud to be able to bring The Mask of Orpheus back to the ENO stage in 2019, and it was such a privilege to spend time with Harry in the Coliseum, and to witness the heartfelt thanks he expressed to the company before the dress rehearsal.

Harry was a giant of a composer, and long may the Birtwistle summits continue to be conquered.

Martyn BrabbinsThis was the spark that led to a series of Birtwistle performances which peppered the Manson Ensemble and the Symphony Orchestra’s programmes for the next two decades. It feels invidious to pick any out, but there are several that continue to have a special resonance. I won’t forget a concert of Secret Theatre, Silbury Air and Cortège – a monster programme, and that was in the same year one of our finest wind quintets performed Five Distances in a pre-Prom concert from memory. Harry simply could not believe his eyes and ears; he always made a point of expressing pride that young players could now ‘eat his music for breakfast’, like seasoned professionals. Indeed, in the memorable celebration day at Plush this summer, several who had performed in the premiere of Secret Theatre said just the same as Ryan Wigglesworth was leading an assembled group through the same piece.

We felt proud that the Academy performed the third outing of Exody after the Chicago and BBC Symphony performances. Harry rather indiscreetly said that the Academy orchestra had learnt it faster than the CSO! We also regularly took Harry’s music to Aldeburgh and when Oliver Knussen was appointed Richard Rodney Bennett Professor at the Academy for those magical five years before his death, Harry’s music acted as its own refrain throughout Olly’s programmes with Manson. Finally, I must mention the generosity with which Harry composed the music for the opening of the Susie Sainsbury Theatre in 2018. Unsurprisingly the score made demands on our brass players and no less on our percussion department as a large number of bells were required! Harry refused payment and instead willingly accepted a case of Pomerol, of course from a year he recognised. The last time I saw Harry he was at the Garrick bar with my close Academy colleague Timothy Jones. Greeting him, I asked what he was doing there. ‘I’m going off to the Barbican to hear a piece of mine Simon’s doing’. I asked him to remind me what piece it was. ‘I can’t remember’, he answered, before taking a final slug of whisky and shuffling on his way, wrapped in one of his memorable shawls, to the closest taxi.

Professor Jonathan Freeman-Attwood cbe Principal of the Royal Academy of Music

A glance through the Harrison Birtwistle catalogue informs us that one of the soloists in the first performance of Nenia: The Death of Orpheus (1970) was a young pianist called Paul Crossley, then only in his second professional season. I can’t remember a time in my career when I didn’t know Harry or his music, nor when we were not a part of the same shared project. So – how to choose from 50 years of memories? I was helped by a friend, someone absolutely unconnected with the musical word, who suggested ‘make it very personal, tell me about your favourite piece (or pieces) and why you like them so much’, and, she added, ‘tell me something affectionate about him’.

My favourites, perhaps because I know them best, but also because I think they are him at his best, are his London Sinfonietta pieces, in particular Silbury Air and Ritual Fragment. The first thing to say is that he is one of the great originals. Though I can spot an occasional influence, his music simply does not ever sound like any other, but it does always sound like him. Pieces often start with a note, a rhythm, a texture, a ‘splurge’ one might almost say, which is then ‘let go’, and left to find its way. Silbury Air starts with the note E. No matter how many times I have listened to it – the sounds familiar, the landmarks well-known – the journey is never the same. Everything seems in a permanent state of exposition, unconnected, not dissolving or solidifying. I am still never precisely sure where I am going next. This is probably not easy for some, but for me it is exciting. The word is, possibly, beguiling, but not in the sense of ‘being taken for a ride’. There’s no faking with Harry. So, the journey is always fresh, and the going itself is what it is, always, at each hearing, unique in its trajectory.

Ritual Fragment leads me to describe the first of two occasions on which I saw Harry radiantly happy. The piece was his spontaneous, unsolicited, tribute to Michael Vyner, his friend and the long-time Artistic Director of the London Sinfonietta. It is an extraordinary work of communion – of thanks, memory, and sharing. After its dress rehearsal on a wonderful spring morning everybody involved – he, all the players, me – came back to my house for lunch. Old experienced hands we might have been, but we all knew we’d just heard a blazing masterpiece. And, most importantly, Harry knew it too – he was almost bursting. It was such a joyous occasion and as wonderful a tribute, in its own way, as Michael could have wished for.

Some years later Harry and his beloved wife Sheila came to stay with me and my partner John in our holiday home on Lanzarote. Sheila was already very ill, but the moment they arrived our island exerted its magic and, miraculously Sheila went into total remission. We have one extraordinary beach where it seems you can almost walk out into the sea itself. To remember Harry and Sheila doing just that, hand in hand, as happy as young newlyweds, brings tears to my eyes even as I write it.

‘…HIS MUSIC SIMPLY DOES NOT EVER SOUND LIKE ANY OTHER, BUT IT DOES ALWAYS SOUND LIKE HIM.’

We all had a lot of fun during that time and I would like to end with a reminiscence of Harry and I, just the two of us, taking a walk one day. I’m sure we had lots of serious talk, but suddenly we started remembering our early upbringing – his in Accrington, Lancashire, mine in Dewsbury, Yorkshire. We started exchanging ‘northernisms’ from our grandparents’ generation – we could both still do the accents very well! One of his was ‘you know, us northerners – we like to keep ourselves to ourselves’. As Harry said, ‘I don’t think we’d have been their greatest shining examples, would we’? One of mine was –when we were naughty – ‘if you’re not right good very soon you’ll be shown a thing or two’.

Well, Harry, I have to say, I think you were ‘right good very soon’ and I know we’ve been ‘shown a thing or two’.

Thank you, my friend.

Paul Crossley Pianist and London Sinfonietta Artistic Director from 1988 to 1994Over the last five decades the London Sinfonietta has collaborated with an illustrious list of composers from across the world though, perhaps more than anybody, Birtwistle was the Sinfonietta composer. He penned score after score for the ensemble, and his relationship with the players was close and hugely productive.

Something of a paradox resides at the heart of Birtwistle’s output. While post-war modernism provided its technical foundation, the sound of his music evokes much older imagery – medieval English ceremony, archaic Attic ritual, even the passage of geological time. His extraordinary gift was to forge a sonic vision from material which was resolutely contemporary but, through the alchemy of his imagination, appears simultaneously ancient and timeless.

And the sound is highly distinctive, with its dark and crunchy textures and bracing rhythmic vigour. The dynamism of his structures, where terraced strata interact and mutate along perpetually unpredictable paths, also gives the music huge dramatic momentum.

On a personal level – once the ice broke – Harry was the sweetest of men, full of humour and the source of endlessly fascinating, original and memorable conversation. It was a privilege to know him and I will miss him very deeply.